Abstract

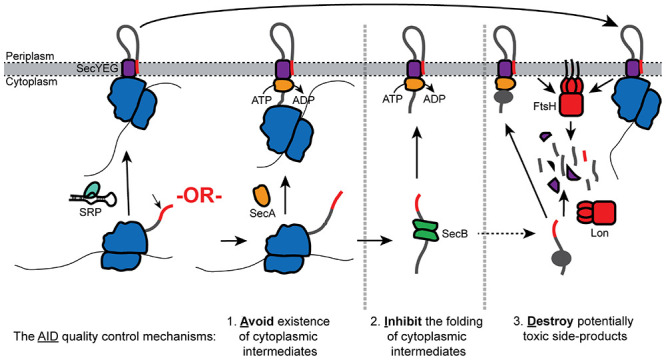

The evolutionarily conserved Sec machinery is responsible for transporting proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane. Protein substrates of the Sec machinery must be in an unfolded conformation in order to be translocated across (or inserted into) the cytoplasmic membrane. In bacteria, the requirement for unfolded proteins is strict: substrate proteins that fold (or misfold) prematurely in the cytoplasm prior to translocation become irreversibly trapped in the cytoplasm. Partially folded Sec substrate proteins and stalled ribosomes containing nascent Sec substrates can also inhibit translocation by blocking (i.e., “jamming”) the membrane-embedded Sec machinery. To avoid these issues, bacteria have evolved a complex network of quality control systems to ensure that Sec substrate proteins do not fold in the cytoplasm. This quality control network can be broken into three branches, for which we have defined the acronym “AID”: (i) avoidance of cytoplasmic intermediates through cotranslationally channeling newly synthesized Sec substrates to the Sec machinery; (ii) inhibition of folding Sec substrate proteins that transiently reside in the cytoplasm by molecular chaperones and the requirement for posttranslational modifications; (iii) destruction of products that could potentially inhibit translocation. In addition, several stress response pathways help to restore protein-folding homeostasis when environmental conditions that inhibit translocation overcome the AID quality control systems.

Keywords: Sec, protein translocation, quality control, protein targeting, molecular chaperones, proteases

Graphical Abstract

Overview of the AID quality control pathways.

Introduction

In bacteria, a significant subset of proteins is localized to the cell envelope, which in the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli consists of the cytoplasmic membrane, the outer membrane, and the soluble compartment sandwiched in-between known as the periplasm (Tsirigotaki et al., 2017; Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). For most of these proteins, the Sec machinery is responsible for the first step in their correct localization, which is translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane (Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). Protein substrates of this machinery must be in an unfolded conformation in order to pass through the membrane-embedded Sec machinery and across the cytoplasmic membrane (Randall and Hardy, 1986; Tani et al., 1989; Hardy and Randall, 1991; Uchida et al., 1995). However, many Sec substrate proteins are capable of folding, misfolding, or aggregating in the cytoplasm, and the proteins that do fold (or misfold) prior to translocation become irreversibly trapped in the cytoplasm (Randall and Hardy, 1986;

Kumamoto and Gannon, 1988). Consequently, protein folding presents a predicament for Sec-dependent protein translocation: Sec substrate proteins must fold at their final destination to carry out their function, but premature folding prevents their correct localization.

The two core components of the bacterial Sec machinery are SecYEG and SecA (Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). During translocation, substrate proteins pass through a protein-conducting channel in the cytoplasmic membrane formed by the integral cytoplasmic membrane protein (IMP) SecY, which is stabilized by the IMPs SecE and SecG (SecYEG) (Van den Berg et al., 2004; Cannon et al., 2005). The requirement for unfolded proteins is a consequence of the dimensions of the SecYEG channel: proteins must be almost completely unfolded in order to pass through the central constriction in the channel (Randall and Hardy, 1986; Tani et al., 1989; Uchida et al., 1995; Gumbart and Schulten, 2006; Tian and Andricioaei, 2006; Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). SecA is an ATPase that drives the translocation of substrate proteins through SecYEG through repeated rounds of ATP binding and hydrolysis (Lill et al., 1989; Brundage et al., 1990). Several mechanisms have been proposed for SecA-mediated translocation and reviewed elsewhere (Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018; Allen et al., 2020; Catipovic and Rapoport, 2020). In addition to SecYEG and SecA, a number of evolutionarily conserved IMPs, including SecD, SecF, YidC, and YajC, form a supercomplex with SecYEG in vivo known as the holotranslocon and assist the core Sec machinery (Schulze et al., 2014; Botte et al., 2016; Komar et al., 2016).

Folding (or misfolding) of a Sec substrate protein in the cytoplasm prior to translocation inhibits Sec-dependent translocation both directly and indirectly. Most obviously, folding inhibits translocation of the protein itself (Randall and Hardy, 1986; Teschke et al., 1991; Huber et al., 2005b). However, folded proteins that are partially translocated across the membrane can become stuck and block (or “jam”) the SecYEG channel (Bieker et al., 1990). The jammed SecYEG is rapidly degraded, which can inhibit translocation indirectly when the jamming occurs on a large scale (van Stelten et al., 2009). Finally, substrate proteins that accumulate in the cytoplasm competitively inhibit translocation by making non-productive interactions with the cytoplasmic Sec machinery (Valent et al., 1997; Drew et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2007; Klepsch et al., 2011). Inhibition of translocation also results in the accumulation of misfolded Sec substrates in the cytoplasm, which disturbs the protein-folding homeostasis of the cell (Wild et al., 1992, 1993). Cells have evolved a complex network of quality control systems to prevent or address these issues. The mechanisms of this quality control network can be divided into three branches, which we refer to by the acronym “AID.”

-

1.

Mechanisms that avoid the existence of unfolded cytoplasmic intermediates through efficient delivery of newly synthesized substrate proteins to the Sec machinery,

-

2.

Mechanisms that inhibit the folding of Sec substrate proteins that transiently reside in the cytoplasm,

-

3.

Mechanisms that result in the destruction of products that could inhibit translocation.

In this review, we focus on the quality control network of E. coli because it is the most extensively investigated bacterial system. However, because the basic mechanism of bacterial protein translocation is evolutionarily conserved, the quality control networks of other bacterial species will fit the AID rubric even when there are some additional or absent mechanisms.

Avoidance of Cytoplasmic Intermediates Through Cotranslational Targeting

In bacteria, proteins can be transported through SecYEG by one of the two mechanisms: (i) translationally coupled translocation (CT) (Figure 1A) or (ii) translationally uncoupled translocation (UT) (Figure 1B; Rapoport, 2007; Steinberg et al., 2018). During CT, protein translocation is obligately cotranslational: ribosomes are directly bound to SecYEG from an early stage in protein synthesis, which allows the Sec substrates to be synthesized directly into the protein-conducting channel and across the cytoplasmic membrane (Schierle et al., 2003; Jomaa et al., 2016, 2017). Consequently, CT avoids the presence of a cytoplasmic intermediate entirely. During UT, protein translocation can be either co- or post-translational, but it is not directly coupled to protein synthesis (Josefsson and Randall, 1981a, b; Randall, 1983). In addition, many proteins exported by the UT mechanism are fully synthesized before translocation begins (Josefsson and Randall, 1981a, b). In most publications, CT is commonly referred to as the “cotranslational” pathway, while UT is commonly known as the “posttranslational” pathway. However, because UT substrates can engage SecYEG cotranslationally (Josefsson and Randall, 1981a), this terminology is potentially confusing and we have avoided it.

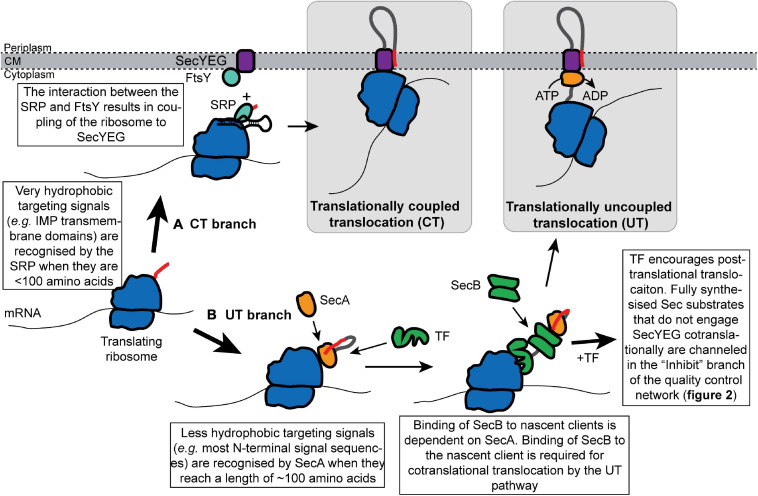

FIGURE 1.

Cotranslational recognition of nascent Sec substrate proteins by the SRP or SecA allows cells to avoid the existence of cytoplasmic intermediates. Nascent Sec substrates are recognized by ribosome-bound SRP or SecA. (A) In translationally coupled translocation (CT), the SRP recognizes the targeting signal of a subset of Sec substrates (primarily IMPs) from an early stage in protein synthesis. The SRP targets the translating ribosome to SecYEG by interacting with its receptor protein FtsY at the membrane, which results in the binding of the translating ribosome to SecYEG and direct coupling of translocation to protein synthesis. (B) Sec substrates that fail to be recognized by the SRP are targeted for translationally uncoupled translocation (UT) by SecA. SecA recognizes the targeting signal of a nascent Sec substrate when it is about 120 amino acids from the peptidyl transferase site in the ribosome. SecA then recruits SecB to the nascent chain. Upon recruitment of SecB, nascent substrates of the UT pathway can either engage SecYEG cotranslationally or can be held in a translocation-competent conformation by the “Inhibit” branch of the quality control network.

Cotranslational Targeting to the CT Pathway

Protein substrates of the CT pathway are initially recognized by the signal recognition particle (SRP), a ribonucleoprotein complex that consists of the Ffh protein and the 4.5S SRP-RNA (Figure 1A; Saraogi and Shan, 2014; Steinberg et al., 2018) (An SRP-independent recognition mechanism has also been proposed but is not discussed here; Bibi, 2012). The SRP binds to the 23S ribosomal RNA on the large subunit of the ribosome near the opening of the polypeptide exit channel at a site that also includes the ribosomal proteins uL23, uL24, and uL29 (Gu et al., 2003; Halic et al., 2006; Schaffitzel et al., 2006; Jomaa et al., 2016, 2017). Binding at this site allows Ffh to sample nascent chains and bind to the exposed targeting signal of its substrate proteins just as they emerge from the ribosome (Jomaa et al., 2016; Denks et al., 2017). In eukaryotes, binding of the SRP to a targeting signal induces a transient translational pause, which is relieved upon transfer to the membrane-bound machinery (Walter and Johnson, 1994). The Bacillus subtilis SRP may also induce translational pausing (Beckert et al., 2015). However, SRP-induced translational pausing has not been observed in E. coli, and the E. coli SRP-RNA lacks the domain that induces pausing in other species (Powers and Walter, 1997). Ffh targets the translating ribosome to the cytoplasmic membrane by interacting with its receptor protein FtsY, and coordinated guanosine diphosphate (GTP) hydrolysis by Ffh and FtsY results in coupling of the translating ribosome to SecYEG (Zhang et al., 2010; Saraogi and Shan, 2014).

Cotranslational Targeting to the UT Pathway

Nascent protein substrates of the UT pathway are recognized cotranslationally by SecA (Figure 1B; Huber et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). SecA binds to the ribosome near the opening to the polypeptide exit channel at a site near the SRP binding site, which includes the ribosomal proteins uL23 and uL29 (Huber et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2014; Jamshad et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). A portion of SecA may also protrude into the polypeptide exit channel when it is bound to the ribosome (Knupffer et al., 2019). Mutations that disrupt the interaction between SecA and the ribosome cause a defect in UT in vivo (Huber et al., 2011).

SecA binds a wide range of nascent Sec substrate proteins in vivo (Chun and Randall, 1994; Huber et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). SecA can bind to nascent polypeptides when they reach a length of approximately 120 amino acids (Huber et al., 2017), which is consistent with the positioning of SecA in cryo-electron microscopic (EM) structures of the SecA-ribosome complex (Singh et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019). Binding to nascent polypeptides requires a conformation change in SecA: the C-terminal tail of SecA autoinhibits the protein when it is not bound to a substrate protein (Gelis et al., 2007; Jamshad et al., 2019). Interaction of SecA with the ribosome destabilizes this autoinhibited conformation and activates SecA to binding to nascent substrates (Jamshad et al., 2019). SecA then recruits the molecular chaperone SecB to the nascent polypeptide chain (see the section on SecB below for more details) (Huber et al., 2017). Recruitment of SecB is required for the cotranslational targeting to SecYEG (Kumamoto and Gannon, 1988; Huber et al., 2017). Some early studies suggested that SecB can directly recognize nascent polypeptides (Kumamoto and Gannon, 1988; Kumamoto and Francetic, 1993; Fekkes et al., 1998), and binding to SecB can activate SecA to bind to substrate proteins (Gelis et al., 2007). However, binding of SecB to nascent clients is dependent on SecA in vivo, suggesting that it is SecA that normally recognizes nascent substrates of the UT pathway (Huber et al., 2017).

Sorting to the CT and UT Pathways

Sec substrate proteins are recognized by virtue of an internally encoded targeting signal (Bassford and Beckwith, 1979; Ulbrandt et al., 1997; Schierle et al., 2003; Hegde and Bernstein, 2006). In the case of IMPs, this targeting signal is a transmembrane helix (or, occasionally, multiple transmembrane helices) (Ulbrandt et al., 1997; Schibich et al., 2016). For outer membrane proteins (OMPs), soluble periplasmic proteins (PPs), and lipoproteins (LPs), the targeting signal is an N-terminal signal sequence, which is proteolytically removed from the protein during translocation (von Heijne, 1990; Hegde and Bernstein, 2006). Most IMPs are targeted to the CT pathway (Ulbrandt et al., 1997; Schibich et al., 2016), and although the CT pathway does recognize a small subset of cleavable signal sequences, most OMPs, PPs, and LPs are targeted to the UT pathway (Huber et al., 2005a). The distinguishing feature of the targeting signals recognized by the CT pathway is that they are more hydrophobic than those that target proteins to the UT pathway (Lee and Bernstein, 2001; Schierle et al., 2003; Huber et al., 2005a; Schibich et al., 2016; Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). Mutations that increase the hydrophobicity of a UT signal sequence can re-route translocation to the CT pathway (Lee and Bernstein, 2001; Bowers et al., 2003).

Sorting to the CT or UT pathway appears to be determined by a triaging mechanism: if a targeting signal is sufficiently hydrophobic, the substrate protein will be channeled into the CT pathway, while proteins containing less hydrophobic targeting signals are channeled into the UT pathway by default (Lee and Bernstein, 2001; Schierle et al., 2003). The physiological basis for the evolution of a bifurcated targeting pathway is likely complex. For example, some proteins may be targeted to the CT pathway because they are prone to aggregation in the cytoplasm (such as IMPs) (Ulbrandt et al., 1997). Others may fold too rapidly to be exported by the UT pathway (Huber et al., 2005a) or are toxic in the cytoplasm. The choice of pathway can also affect the folding pathway of a protein in the periplasm (Kadokura and Beckwith, 2009). However, high levels of CT could potentially be toxic under conditions that inhibit translocation elongation (van Stelten et al., 2009), and the rate of CT is probably inherently slower than that of UT because it is limited by the rate of translocation elongation (Pugsley, 1993; Cranford-Smith and Huber, 2018). Finally, the existence of two pathways may allow the UT pathway to serve as a backup pathway for CT when the CT pathway is defective (Lee and Bernstein, 2001; Schierle et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2021).

Trigger Factor Delays Delivery of UT Substrate Proteins to SecYEG

The ribosome-associated molecular chaperone Trigger Factor (TF) delays the delivery of many nascent Sec substrates to SecYEG (Lee and Bernstein, 2002; Ullers et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2011). TF binds to the ribosome near the polypeptide exit channel at a site that includes uL23 and hunches over the opening to the channel (Kramer et al., 2002; Ferbitz et al., 2004). This ribosome-binding activity facilitates the interaction of TF with nascent polypeptides (Kramer et al., 2002, 2004, 2019). Although SecA and TF bind to similar sites on the ribosome (Kramer et al., 2002; Huber et al., 2011), binding is not mutually exclusive and both proteins can bind to the same nascent chain simultaneously (Huber et al., 2017). TF binds to hydrophobic patches in non-native nascent polypeptides with relatively low specificity and can begin to interact with nascent polypeptides when they reach a length of approximately 110 amino acids in vivo (Patzelt et al., 2001; Kramer et al., 2002; Oh et al., 2011; Bornemann et al., 2014). The binding of TF to nascent chains is thought to delay the folding of most nascent polypeptides, which facilitates the correct folding of cytoplasmic proteins by preventing off-pathway folding intermediates (Deuerling et al., 1999; Kramer et al., 2004, 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2006; Kaiser et al., 2006; Merz et al., 2008; Martinez-Hackert and Hendrickson, 2009; Nilsson et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019).

TF was initially identified in biochemical screens for proteins that promote Sec-dependent protein translocation (Crooke and Wickner, 1987; Crooke et al., 1988; Lill et al., 1988; Lecker et al., 1989), and ribosome profiling experiments indicate that TF binds to many nascent Sec substrates, particularly OMPs (Oh et al., 2011). Strains deficient in TF have a mild outer membrane biogenesis defect (Oh et al., 2011), and TF can enhance translocation in vitro (Crooke et al., 1988; De Geyter et al., 2020), which has led to the suggestion that TF can inhibit the folding of Sec substrates (see below). However, strains lacking TF do not have an obvious defect in Sec-dependent protein translocation (Lee and Bernstein, 2002). Indeed, mutations that disrupt the gene encoding TF (tig) suppress many translocation defects by allowing nascent UT substrates to engage SecYEG cotranslationally (Lee and Bernstein, 2002; Ullers et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2011), suggesting that TF prevents nascent Sec substrates from engaging SecYEG cotranslationally. It has been suggested that TF could compete with the SRP for binding to substrate proteins (Eisner et al., 2003, 2006; Ariosa et al., 2015). However, a growing body of evidence suggests that TF does not play a role in the choice of pathway (i.e., CT vs. UT); rather, the binding of TF to nascent UT substrates prevents them from engaging SecYEG cotranslationally (Lee and Bernstein, 2002; Ullers et al., 2007; Huber et al., 2017). Thus, the role of TF in Sec-dependent translocation is to enhance the bifurcation of the two translocation pathways, potentially for the reasons discussed above.

Inhibition of Protein Folding of Sec Substrates in the Cytoplasm

Because many substrates of the UT pathway are fully synthesized (or nearly fully synthesized) before they engage SecYEG, these proteins have the potential to fold (or misfold) in the cytoplasm prior to translocation. Cells prevent the premature folding of Sec substrate proteins via two mechanisms: (i) molecular chaperones, which bind to unfolded Sec substrate proteins and hold them in a translocation-competent conformation in the cytoplasm (Figures 2A–C); and (ii) requirements of posttranslational modifications that can only be made upon translocation for stable folding (Figures 2D,E). By convention, we refer to proteins as “clients” of molecular chaperones and “substrates” of the Sec machinery.

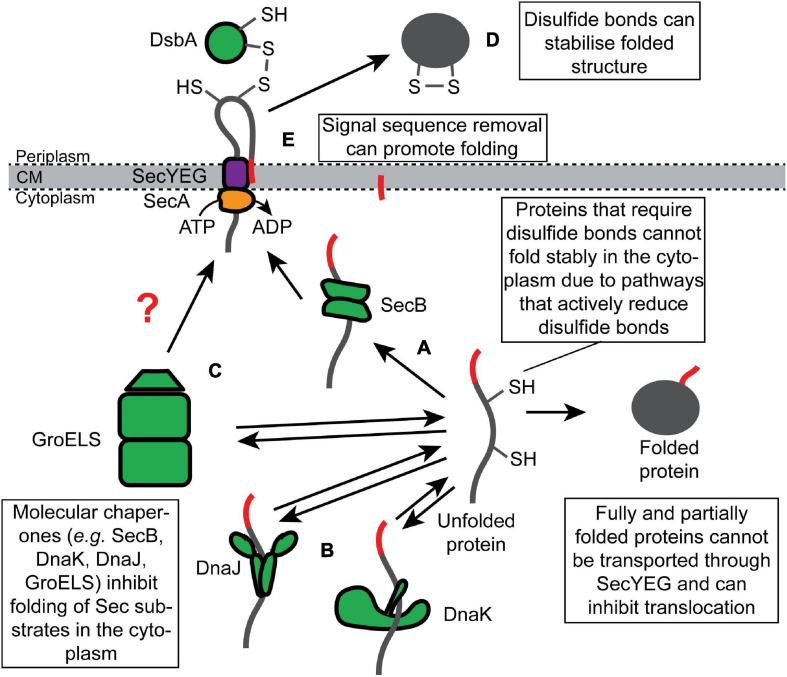

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of the folding of synthesized Sec substrate proteins by molecular chaperones and posttranslational modifications. Fully synthesized Sec substrate proteins (or domains of Sec substrate proteins) are prevented from folding stably in the cytoplasm by molecular chaperones, such as (A) SecB, (B) DnaK or DnaJ, and (C) GroELS. Alternatively, many Sec substrate proteins require posttranslational modification that can only be made in the periplasm to fold stably, such as (D) disulfide bonds and (E) proteolytic removal of the N-terminal signal sequence.

Inhibition of Folding by SecB

SecB is a tetrameric molecular chaperone that binds to a subset of unfolded substrates of the UT pathway and prevents them from folding in the cytoplasm (Figure 2A; Collier et al., 1988; Hartl et al., 1990; Zhou and Xu, 2003). Mutations disrupting the secB gene cause defective translocation of this subset in vivo (Kumamoto and Beckwith, 1983, 1985; Baars et al., 2006). SecB binds to hydrophobic patches in its non-native client proteins in an ATP-independent fashion (Randall and Hardy, 2002; Huang et al., 2016). SecB binds to clients with relatively low specificity in vitro (Randall et al., 1998a, b; Knoblauch et al., 1999) but with high selectivity in vivo (Kumamoto and Beckwith, 1985; Kumamoto and Francetic, 1993). This difference could be explained by the dependence of SecB on SecA for binding to nascent substrates in vivo since SecA does display an increased affinity for proteins containing N-terminal signal sequences (Kebir and Kendall, 2002; Gouridis et al., 2009; Huber et al., 2017). SecB can bind to full-length proteins and target them for translocation in a reconstituted system in vitro (Fekkes et al., 1998). However, it is not clear whether this is also the case in vivo. If so, recognition likely requires clients to fold slowly enough for SecB to bind cooperatively to multiple low-affinity binding sites (Hardy and Randall, 1991; Randall et al., 1998b).

SecB ultimately delivers its client proteins to the translocation machinery by binding to SecA (Gannon and Kumamoto, 1993; Fekkes et al., 1998). The interaction between SecA and SecB is driven by at least two sites of interaction (Woodbury et al., 2000; Randall et al., 2004; Crane et al., 2005; Randall and Henzl, 2010): first, the small metal-binding domain (MBD) at the extreme C-terminus of SecA binds to an evolutionarily conserved binding surface on SecB (Fekkes et al., 1997, 1999; Zhou and Xu, 2003); second, the C-terminal α-helix of SecB interacts with the catalytic core of SecA (Woodbury et al., 2000; Randall et al., 2004; Randall and Henzl, 2010). SecB transfers its client proteins to SecA by destabilizing the autoinhibited conformation of SecA (Gelis et al., 2007). Because the steady state affinity of SecA for non-native translocation-competent Sec substrates is at least an order of magnitude lower than that of SecB, the transfer of client proteins from SecB to SecA also likely requires a conformation change in SecB that reduces the affinity of SecB for its client (Randall et al., 1998b; Woodbury et al., 2000; Gouridis et al., 2009). Nearly all α-,β-, and γ-Proteobacteria species contain a SecB homolog, but SecB is conspicuously absent from many bacterial phylogenetic groups (even those containing a SecA protein with an MBD) (van der Sluis and Driessen, 2006; Jamshad et al., 2019). However, some phylogenies contain proteins that are structurally related to SecB and that could have a similar function, suggesting that the presence of SecB-like proteins could be a universal feature of Sec-dependent protein translocation in bacteria (Sala et al., 2014).

Although SecB is not essential for viability in E. coli (Kumamoto and Gannon, 1988; Shimizu et al., 1997), deficiencies in SecB-dependent quality control cause collateral defects in protein translocation and protein-folding homeostasis. For example, mutations that inactivate the secB gene cause defects in the translocation of proteins that do not normally bind to SecB in vivo (Francetic and Kumamoto, 1996), suggesting that a lack of quality control causes a translocation defect that has knock-on consequences for non-client proteins. Mutations in secB also result in induction of the heat shock response (Wild et al., 1993), indicating a perturbation in the protein-folding homeostasis. Deletion of the secB gene causes a cold-sensitive growth defect (Shimizu et al., 1997), which is likely caused by the combined effect on protein translocation and the protein-folding homeostasis (Altman et al., 1991; Ullers et al., 2007; Sakr et al., 2010).

Inhibition of Folding by General Chaperone Systems

Two general chaperone systems, the DnaK/DnaJ (Figure 2B) and the GroEL/GroES (Figure 2C) systems, have been implicated in Sec-dependent protein translocation. Unlike SecB, whose role is normally restricted to Sec-dependent translocation (Kumamoto and Beckwith, 1985; Kumamoto and Francetic, 1993), the DnaK/DnaJ and GroEL/GroES systems assist the folding of a wide range of soluble cytoplasmic proteins (Kim et al., 2013; Dahiya and Buchner, 2019). In the DnaK/DnaJ system, DnaJ (Hsp40) binds to non-native or misfolded client proteins and delivers them to the ATPase DnaK (Hsp70), and this interaction stimulates a conformational change in DnaK, driven by ATP hydrolysis, that promotes folding of the client protein (Rosenzweig et al., 2019). GrpE-stimulated nucleotide exchange releases the client protein and promotes refolding (Rosenzweig et al., 2019). Mutations disrupting the DnaK chaperone system cause a defect in the translocation of a subset of Sec substrate proteins and cause growth defects when combined with mutations that inactivate secB (Altman et al., 1991; Wild et al., 1992, 1996; Lee and Bernstein, 2002; Ullers et al., 2007), suggesting that DnaK can compensate for the loss of SecB. Overexpression of DnaK or DnaJ individually can suppress these defects and even enhance the efficiency with which some proteins are exported (Phillips and Silhavy, 1990; Sakr et al., 2010). However, overexpression of both proteins simultaneously cannot suppress the phenotype of a secB mutant (Sakr et al., 2010), suggesting that DnaK and DnaJ promote protein translocation by holding Sec substrates in a translocation-competent conformation (Figure 2B).

Several early studies suggested that the GroEL/GroES chaperone system could also assist the Sec machinery (Crooke et al., 1988; Kusukawa et al., 1989; Lecker et al., 1989). In this system, GroEL binds to misfolded client proteins, and the binding of GroES to GroEL stimulates an ATP-dependent conformational change in GroEL that promotes protein folding (Horwich et al., 2006). GroEL binds to non-native Sec substrates in vitro (Lecker et al., 1989), and mutants that are deficient in GroEL or GroES are defective in the translocation of UT substrates (Kusukawa et al., 1989), suggesting that GroEL/GroES can assist Sec-dependent translocation. In support of this notion, the overproduction of GroEL enhances the translocation efficiency of LamB-LacZ (Phillips and Silhavy, 1990). In addition, GroEL localizes to the cytoplasmic membrane, and localization is dependent on SecA (Bochkareva et al., 1998), suggesting that GroEL could bind to non-native translocation-competent Sec substrates and target them to SecA (Figure 2C). However, the involvement of GroEL/GroES in protein translocation is debated (Altman et al., 1991).

Posttranslational Modifications That Facilitate Protein Folding

The Sec quality control network has also exploited some posttranslational modifications that facilitate protein folding or stabilize the final folded structure, which can only be made upon protein translocation. For example, disulfide bonds create covalent links between cysteine amino acid side chains that stabilize the tertiary structure of the protein (Manta et al., 2019). In E. coli, disulfide bonds are formed by the periplasmic Dsb machinery, which passes the electrons from the oxidized cysteines in the client protein to a reduced quinone in the cytoplasmic membrane via a series of disulfide exchange reactions (Landeta et al., 2018; Manta et al., 2019). Many proteins, such as alkaline phosphatase (PhoA), require structural stabilization from disulfide bonds in order to fold into an active conformation (Figure 2D; Sone et al., 1997). A highly redundant network of thiol redox pathways actively reduces disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm (Ezraty et al., 2017), which prevents proteins like PhoA from folding stably while they transiently reside in the cytoplasm. In some bacteria, the folding of exported proteins can also be stabilized by other types of covalent linkages between amino acid side chains, such as isopeptide bonds (Kang et al., 2007; Kang and Baker, 2011).

A second posttranslational modification that can facilitate folding is proteolytic removal of the N-terminal signal sequence. The signal sequences of some proteins, such as maltose-binding protein (MBP) and ribose binding protein (RBP), slow the folding of their cognate proteins (Park et al., 1988), and the reduction in the rate of folding is required for efficient interaction with SecB (Liu et al., 1989). However, signal sequences are removed during translocation by signal peptidase (Josefsson and Randall, 1981a, b; von Heijne, 1990; Hegde and Bernstein, 2006; Figure 2E). Biophysical experiments suggest that the signal sequence of MBP slows MBP folding by binding to the hydrophobic core of the non-native protein (Beena et al., 2004), and the conserved architecture of signal sequences suggest that this anti-folding activity may be a general property (von Heijne, 1990). If so, the effect of the signal sequence on folding is moderate since the MBP signal sequence cannot sufficiently retard the folding of at least two normally cytoplasmic proteins (thioredoxin-1 and DARPin) to allow efficient translocation by the UT pathway (Schierle et al., 2003; Steiner et al., 2006).

Destruction of Products That Inhibit Protein Translocation

Proteins that escape the “Avoid” and “Inhibit” branches of the Sec quality control network are “Destroyed” by proteases. Two cytoplasmic proteases, Lon and FtsH, appear to be responsible for most of the turnover of potentially toxic Sec substrates in the cytoplasm (van Stelten et al., 2009; Sakr et al., 2010). Both Lon and FtsH are general proteases that belong to the AAA+ (ATPase associated with cellular activities) family of proteases, which also includes ClpXP, ClpAP, and HslUV proteases (Sauer and Baker, 2011). AAA+ proteases contain ATPase motor domains that unfold substrate proteins and feed them into the proteolytic active site of a protease module (Sauer and Baker, 2011). In addition, a cytoplasmic peptidase, PrlC, with specificity for N-terminal signal sequences assists Sec-dependent protein translocation in vivo (Conlin et al., 1992).

Destruction of Cytoplasmic Sec Substrates by Lon Protease

Lon protease degrades missorted Sec substrate proteins that accumulate in the cytoplasm (Figure 3A). For example, Lon degrades mutant M13 procoat protein when it is mislocalized to the cytoplasm (Kuhn et al., 1986). In addition, mutations in the prlF gene can enhance the translocation of Sec substrate proteins in vivo by influencing the activity of Lon (Kiino et al., 1990; Snyder and Silhavy, 1992; Minas and Bailey, 1995). PrlF is the antitoxin component of a toxin–antitoxin system in E. coli and is normally degraded by Lon protease (Schmidt et al., 2007). Mutations that inactivate Lon suppress the cold-sensitive viability defect caused by a ΔsecB deletion mutation but also cause the accumulation of aggregated Sec substrates in the cytoplasm (Sakr et al., 2010), suggesting that Lon normally degrades Sec substrate proteins that escape the other quality control pathways.

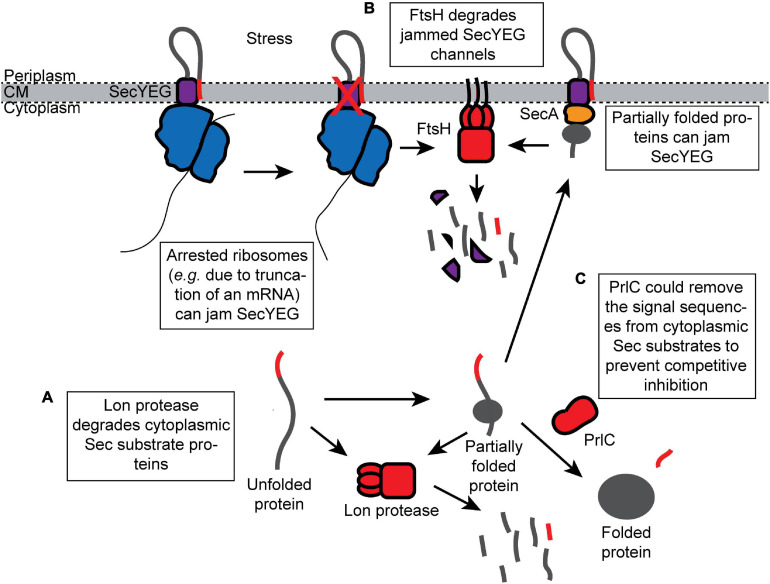

FIGURE 3.

Proteolytic destruction of products that are detrimental to protein translocation. (A) Lon protease prevents mislocalized Sec substrates from inhibiting the Sec machinery by turning over Sec substrates that accumulate in the cytoplasm. (B) FtsH degrades SecYEG channels that have been jammed (e.g., by arrested ribosomes synthesizing Sec substrate proteins). (C) The peptidase PrlC could potentially remove the signal sequences from the Sec substrate proteins that have accumulated in the cytoplasm and prevent them from competitively inhibiting translocation.

Destruction of Jammed SecYEG Complexes by FtsH

FtsH is a membrane-anchored protease that turns over uncomplexed, misfolded, or jammed SecY channels (Figure 3B; Kihara et al., 1995, 1996; van Stelten et al., 2009). FtsH-mediated degradation of SecY can be inhibited by the expression of YccA (van Stelten et al., 2009). It has been suggested that FtsH-mediated degradation clears SecY channels blocked by the arrested ribosomes translating Sec substrate proteins (e.g., due to truncated mRNAs), which may be required to recycle the arrested ribosome (van Stelten et al., 2009). The prevalence and redundancy of ribosome rescue systems suggest that translational arrest is relatively common (Keiler, 2015). In addition, cells deficient in FtsH are defective for Sec-dependent protein translocation (Akiyama et al., 1994), suggesting that rapid clearance of “dead” SecYEG complexes is required to maintain the efficiency of translocation under normal growth conditions.

Other Peptidases

A cytoplasmic peptidase, PrlC (oligopeptidase A), also assists Sec-dependent protein translocation in vivo (Conlin et al., 1992; Kato et al., 1992). Certain mutations in prlC enhance the translocation of Sec substrate proteins containing defective signal sequences in vivo (Emr and Bassford, 1982; Trun and Silhavy, 1987). Biochemical studies suggest that PrlC has specificity for Sec signal sequences (Novak and Dev, 1988; Conlin et al., 1992). However, the molecular mechanism is not known. One possibility is that PrlC degrades free, proteolytically processed signal sequences, which competitively inhibit protein translocation. Alternatively, PrlC could remove signal sequences from Sec substrates that are mislocalized to the cytoplasm, which is an idea that is supported by the accumulation of N-terminally processed Sec substrate in the cytoplasm of some prlC mutants (Figure 3C; Trun and Silhavy, 1989).

Cell Stress Responses That Restore Protein-Folding Homeostasis

Environmental stresses that inhibit translocation can cause a detrimental feedback loop that can overcome the AID quality control systems and disturb protein-folding homeostasis. In an example scenario, Sec substrate proteins that accumulate in the cytoplasm could partially fold and cause wide-scale jamming of SecYEG, which would result in the quantitative destruction of SecY by FtsH, enhancing the accumulation of Sec substrate proteins in the cytoplasm (Oliver et al., 1990; Wagner et al., 2007; van Stelten et al., 2009; Klepsch et al., 2011). In E. coli, there are at least two stress response pathways that can break this cycle: the σ32 pathway and the Cpx pathway (Wild et al., 1993; Cosma et al., 1995). σ32 is an alternative sigma factor that recognizes the transcriptional promoters of genes involved in adapting to conditions that perturb protein-folding homeostasis, and the σ32 pathway is induced by the accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins in the cytoplasm (Roncarati and Scarlato, 2017). Defects in Sec-dependent protein translocation (e.g., caused by mutations in secB) result in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded Sec substrate proteins in the cytoplasm and induction of the σ32 pathway (Wild et al., 1992, 1993). σ32 controls expression of many proteins that are involved in the AID quality control network (e.g., DnaK/DnaJ, GroELS, PrlC, Lon, and FtsH among others), and its induction can suppress defects caused by inhibition of Sec-dependent protein translocation (Grossman et al., 1987; Altman et al., 1991). In addition, the regulatory circuit that governs the induction of the σ32 pathway incorporates signals from FtsH (Tomoyasu et al., 1995) and the SRP (Lim et al., 2013), suggesting that translocation defects are a physiological source of disruptions in protein-folding homeostasis.

Induction of the Cpx pathway suppresses the toxicity caused by jamming of SecYEG (Cosma et al., 1995; Pogliano et al., 1997). The Cpx pathway is induced by conditions that disturb protein-folding homeostasis in the periplasm (Cosma et al., 1995). The suppression of jamming toxicity is due, at least in part, to the inhibition of FtsH by induction of the yccA gene (van Stelten et al., 2009).

Outlook

The number of quality control mechanisms that assist Sec-dependent protein translocation suggests that there is strong evolutionarily pressure to prevent the folding (or misfolding) of Sec substrate proteins in the cytoplasm. However, there are significant gaps in the understanding of this quality control network. For example, the mechanism of CT is not fully understood. SecA is required for efficient CT (Schierle et al., 2003), but it is not clear whether it is involved in the recognition of substrate proteins or the mechanism of translocation across the membrane. In addition, recent work indicating that the SRP is not strictly essential raises fundamental questions about the mechanism of targeting to the CT pathway (Zhao et al., 2021).

It seems likely that there are additional quality control pathways that have not yet been identified. For example, recent work suggests that TF cooperates with the ClpXP protease, raising the possibility that TF could channel misfolded OMPs to ClpXP for destruction (Rizzolo et al., 2021). In addition, there could be previously unidentified components that facilitate these pathways. For example, there are two E. coli proteins of unknown function, YecA and YchJ, that contain MBDs that are nearly identical to that of SecA (Cranford-Smith et al., 2020a), and un-peer-reviewed work by Cranford-Smith et al. (2020b) suggests that one of these proteins, YecA, is a molecular chaperone that can interact with SecB. The Pfam database contains at least a dozen other proteins of unknown function that contain SecA-like MBDs in other bacterial species (Finn et al., 2014), raising the possibility that there are many additional accessory Sec components. If so, many of these components could assist with one of the AID mechanisms.

Furthermore, it is possible that there are additional quality control mechanisms that do not fit neatly within the AID rubric. For example, DnaK/DnaJ can work in concert with the AAA+ protein ClpB to resolubilize aggregated proteins in the cytoplasm (Schlieker et al., 2004; Rosenzweig et al., 2013; Mogk et al., 2018), raising the possibility that DnaK or another chaperone could cooperate with ClpB to resuscitate folded or aggregated Sec substrates for protein translocation.

Finally, there are still a number of questions about how quality control components distinguish between the substrate and non-substrate proteins. Genetic studies suggest that SecB could directly recognize full-length substrate proteins in vivo (Liu et al., 1988), but if so, by what mechanism? Are Sec substrates targeted to Lon protease, or does Lon degrade misfolded or aggregated Sec substrates as part of its normal house-keeping activity (Sauer and Baker, 2011)? How does FtsH distinguish between jammed SecYEG complexes and those that are actively translocating substrate proteins (van Stelten et al., 2009)? Clearly, additional research is required to fully elucidate the quality control network of the Sec machinery.

Author Contributions

MW wrote drafts of the subsection of molecular chaperones. CJ wrote drafts of the sections on proteases and stress responses. DH conceived the manuscript, wrote drafts of the abstract, introduction and subsection on protein targeting, and was responsible for assembly of the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript, contributed to fundamental background research, filling in references and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Williams and the members of the Huber lab for thoughtful discussions and feedback.

Footnotes

Funding. MW was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)-funded Midlands Integrative Biosciences Training Partnership (MIBTP).

References

- Akiyama Y., Shirai Y., Ito K. (1994). Involvement of FtsH in protein assembly into and through the membrane. II. Dominant mutations affecting FtsH functions. J. Biol. Chem. 269 5225–5229. 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)37678-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen W. J., Watkins D. W., Dillingham M. S., Collinson I. (2020). Refined measurement of SecA-driven protein secretion reveals that translocation is indirectly coupled to ATP turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 31808–31816. 10.1073/pnas.2010906117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman E., Kumamoto C. A., Emr S. D. (1991). Heat-shock proteins can substitute for SecB function during protein export in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 10 239–245. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07943.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariosa A., Lee J. H., Wang S., Saraogi I., Shan S. O. (2015). Regulation by a chaperone improves substrate selectivity during cotranslational protein targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 E3169–E3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars L., Ytterberg A. J., Drew D., Wagner S., Thilo C., Van Wijk K. J., et al. (2006). Defining the role of the Escherichia coli chaperone SecB using comparative proteomics. J. Biol. Chem. 281 10024–10034. 10.1074/jbc.m509929200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassford P., Beckwith J. (1979). Escherichia coli mutants accumulating the precursor of a secreted protein in the cytoplasm. Nature 277 538–541. 10.1038/277538a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckert B., Kedrov A., Sohmen D., Kempf G., Wild K., Sinning I., et al. (2015). Translational arrest by a prokaryotic signal recognition particle is mediated by RNA interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22 767–773. 10.1038/nsmb.3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beena K., Udgaonkar J. B., Varadarajan R. (2004). Effect of signal peptide on the stability and folding kinetics of maltose binding protein. Biochemistry 43 3608–3619. 10.1021/bi0360509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi E. (2012). Is there a twist in the Escherichia coli signal recognition particle pathway? Trends Biochem. Sci. 37 1–6. 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieker K. L., Phillips G. J., Silhavy T. J. (1990). The sec and prl genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 22 291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkareva E. S., Solovieva M. E., Girshovich A. S. (1998). Targeting of GroEL to SecA on the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 478–483. 10.1073/pnas.95.2.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornemann T., Holtkamp W., Wintermeyer W. (2014). Interplay between trigger factor and other protein biogenesis factors on the ribosome. Nat. Commun. 5:4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botte M., Zaccai N. R., Nijeholt J. L., Martin R., Knoops K., Papai G., et al. (2016). A central cavity within the holo-translocon suggests a mechanism for membrane protein insertion. Sci. Rep. 6:38399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. W., Lau F., Silhavy T. J. (2003). Secretion of LamB-LacZ by the signal recognition particle pathway of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185 5697–5705. 10.1128/jb.185.19.5697-5705.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage L., Hendrick J. P., Schiebel E., Driessen A. J., Wickner W. (1990). The purified E. coli integral membrane protein SecY/E is sufficient for reconstitution of SecA-dependent precursor protein translocation. Cell 62 649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon K. S., Or E., Clemons W. M., Jr., Shibata Y., Rapoport T. A. (2005). Disulfide bridge formation between SecY and a translocating polypeptide localizes the translocation pore to the center of SecY. J. Cell Biol. 169 219–225. 10.1083/jcb.200412019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catipovic M. A., Rapoport T. A. (2020). Protease protection assays show polypeptide movement into the SecY channel by power strokes of the SecA ATPase. EMBO Rep. 21:e50905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun S. Y., Randall L. L. (1994). In vivo studies of the role of SecA during protein export in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176 4197–4203. 10.1128/jb.176.14.4197-4203.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier D. N., Bankaitis V. A., Weiss J. B., Bassford P. J., Jr. (1988). The antifolding activity of SecB promotes the export of the E. coli maltose-binding protein. Cell 53 273–283. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90389-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlin C. A., Trun N. J., Silhavy T. J., Miller C. G. (1992). Escherichia coli prlC encodes an endopeptidase and is homologous to the Salmonella typhimurium opdA gene. J. Bacteriol. 174 5881–5887. 10.1128/jb.174.18.5881-5887.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma C. L., Danese P. N., Carlson J. H., Silhavy T. J., Snyder W. B. (1995). Mutational activation of the Cpx signal transduction pathway of Escherichia coli suppresses the toxicity conferred by certain envelope-associated stresses. Mol. Microbiol. 18 491–505. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J. M., Mao C., Lilly A. A., Smith V. F., Suo Y., Hubbell W. L., et al. (2005). Mapping of the docking of SecA onto the chaperone SecB by site-directed spin labeling: insight into the mechanism of ligand transfer during protein export. J. Mol. Biol. 353 295–307. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford-Smith T., Huber D. (2018). The way is the goal: how SecA transports proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 365:fny093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford-Smith T., Jamshad M., Jeeves M., Chandler R. A., Yule J., Robinson A., et al. (2020a). Iron is a ligand of SecA-like metal-binding domains in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 295 7516–7528. 10.1074/jbc.ra120.012611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford-Smith T., Wynne M., Carter C., Jiang C., Jamshad M., Milner M. T., et al. (2020b). AscA (YecA) is a molecular chaperone involved in Sec-dependent protein translocation in Escherichia coli. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.07.21.215244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke E., Guthrie B., Lecker S., Lill R., Wickner W. (1988). ProOmpA is stabilized for membrane translocation by either purified E. coli trigger factor or canine signal recognition particle. Cell 54 1003–1011. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke E., Wickner W. (1987). Trigger factor: a soluble protein that folds pro-OmpA into a membrane-assembly-competent form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 5216–5220. 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya V., Buchner J. (2019). Functional principles and regulation of molecular chaperones. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 114 1–60. 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Geyter J., Portaliou A. G., Srinivasu B., Krishnamurthy S., Economou A., Karamanou S. (2020). Trigger factor is a bona fide secretory pathway chaperone that interacts with SecB and the translocase. EMBO Rep. 21:e49054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denks K., Sliwinski N., Erichsen V., Borodkina B., Origi A., Koch H. G. (2017). The signal recognition particle contacts uL23 and scans substrate translation inside the ribosomal tunnel. Nat. Microbiol. 2:16265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuerling E., Schulze-Specking A., Tomoyasu T., Mogk A., Bukau B. (1999). Trigger factor and DnaK cooperate in folding of newly synthesized proteins. Nature 400 693–696. 10.1038/23301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew D., Froderberg L., Baars L., De Gier J. W. (2003). Assembly and overexpression of membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1610 3–10. 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00707-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner G., Koch H. G., Beck K., Brunner J., Muller M. (2003). Ligand crowding at a nascent signal sequence. J. Cell Biol. 163 35–44. 10.1083/jcb.200306069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner G., Moser M., Schafer U., Beck K., Muller M. (2006). Alternate recruitment of signal recognition particle and trigger factor to the signal sequence of a growing nascent polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 281 7172–7179. 10.1074/jbc.m511388200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emr S. D., Bassford P. J., Jr. (1982). Localization and processing of outer membrane and periplasmic proteins in Escherichia coli strains harboring export-specific suppressor mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 257 5852–5860. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)83857-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezraty B., Gennaris A., Barras F., Collet J. F. (2017). Oxidative stress, protein damage and repair in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15 385–396. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes P., De Wit J. G., Boorsma A., Friesen R. H., Driessen A. J. (1999). Zinc stabilizes the SecB binding site of SecA. Biochemistry 38 5111–5116. 10.1021/bi982818r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes P., De Wit J. G., Van Der Wolk J. P., Kimsey H. H., Kumamoto C. A., Driessen A. J. (1998). Preprotein transfer to the Escherichia coli translocase requires the co-operative binding of SecB and the signal sequence to SecA. Mol. Microbiol. 29 1179–1190. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes P., Van Der Does C., Driessen A. J. (1997). The molecular chaperone SecB is released from the carboxy-terminus of SecA during initiation of precursor protein translocation. Embo J. 16 6105–6113. 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbitz L., Maier T., Patzelt H., Bukau B., Deuerling E., Ban N. (2004). Trigger factor in complex with the ribosome forms a molecular cradle for nascent proteins. Nature 431 590–596. 10.1038/nature02899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Bateman A., Clements J., Coggill P., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., et al. (2014). Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D222–D230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francetic O., Kumamoto C. A. (1996). Escherichia coli SecB stimulates export without maintaining export competence of ribose-binding protein signal sequence mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178 5954–5959. 10.1128/jb.178.20.5954-5959.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P. M., Kumamoto C. A. (1993). Mutations of the molecular chaperone protein SecB which alter the interaction between SecB and maltose-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268 1590–1595. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)53894-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis I., Bonvin A. M., Keramisanou D., Koukaki M., Gouridis G., Karamanou S., et al. (2007). Structural basis for signal-sequence recognition by the translocase motor SecA as determined by NMR. Cell 131 756–769. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouridis G., Karamanou S., Gelis I., Kalodimos C. G., Economou A. (2009). Signal peptides are allosteric activators of the protein translocase. Nature 462 363–367. 10.1038/nature08559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A. D., Straus D. B., Walter W. A., Gross C. A. (1987). Sigma 32 synthesis can regulate the synthesis of heat shock proteins in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1 179–184. 10.1101/gad.1.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S. Q., Peske F., Wieden H. J., Rodnina M. V., Wintermeyer W. (2003). The signal recognition particle binds to protein L23 at the peptide exit of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Rna 9 566–573. 10.1261/rna.2196403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbart J., Schulten K. (2006). Molecular dynamics studies of the archaeal translocon. Biophys. J. 90 2356–2367. 10.1529/biophysj.105.075291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halic M., Blau M., Becker T., Mielke T., Pool M. R., Wild K., et al. (2006). Following the signal sequence from ribosomal tunnel exit to signal recognition particle. Nature 444 507–511. 10.1038/nature05326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S. J., Randall L. L. (1991). A kinetic partitioning model of selective binding of nonnative proteins by the bacterial chaperone SecB. Science 251 439–443. 10.1126/science.1989077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U., Lecker S., Schiebel E., Hendrick J. P., Wickner W. (1990). The binding cascade of SecB to SecA to SecY/E mediates preprotein targeting to the E. coli plasma membrane. Cell 63 269–279. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90160-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde R. S., Bernstein H. D. (2006). The surprising complexity of signal sequences. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31 563–571. 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A., Merz F., Rutkowska A., Zachmann-Brand B., Deuerling E., Bukau B. (2006). Trigger factor forms a protective shield for nascent polypeptides at the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 281 6539–6545. 10.1074/jbc.m512345200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwich A. L., Farr G. W., Fenton W. A. (2006). GroEL-GroES-mediated protein folding. Chem. Rev. 106 1917–1930. 10.1021/cr040435v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Rossi P., Saio T., Kalodimos C. G. (2016). Structural basis for the antifolding activity of a molecular chaperone. Nature 537 202–206. 10.1038/nature18965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D., Boyd D., Xia Y., Olma M. H., Gerstein M., Beckwith J. (2005a). Use of thioredoxin as a reporter to identify a subset of Escherichia coli signal sequences that promote signal recognition particle-dependent translocation. J. Bacteriol. 187 2983–2991. 10.1128/jb.187.9.2983-2991.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D., Cha M. I., Debarbieux L., Planson A. G., Cruz N., Lopez G., et al. (2005b). A selection for mutants that interfere with folding of Escherichia coli thioredoxin-1 in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 18872–18877. 10.1073/pnas.0509583102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D., Jamshad M., Hanmer R., Schibich D., Doring K., Marcomini I., et al. (2017). SecA cotranslationally interacts with nascent substrate proteins in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 199:JB.00622-16. 10.1128/JB.00622-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D., Rajagopalan N., Preissler S., Rocco M. A., Merz F., Kramer G., et al. (2011). SecA interacts with ribosomes in order to facilitate posttranslational translocation in bacteria. Mol. Cell 41 343–353. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshad M., Knowles T. J., White S. A., Ward D. G., Mohammed F., Rahman K. F., et al. (2019). The C-terminal tail of the bacterial translocation ATPase SecA modulates its activity. eLife 8:e48385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa A., Boehringer D., Leibundgut M., Ban N. (2016). Structures of the E. coli translating ribosome with SRP and its receptor and with the translocon. Nat. Commun. 7:10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa A., Fu Y. H., Boehringer D., Leibundgut M., Shan S. O., Ban N. (2017). Structure of the quaternary complex between SRP. SR, and translocon bound to the translating ribosome. Nat. Commun. 8:15470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson L. G., Randall L. L. (1981a). Different exported proteins in E. coli show differences in the temporal mode of processing in vivo. Cell 25 151–157. 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90239-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson L. G., Randall L. L. (1981b). Processing in vivo of precursor maltose-binding protein in Escherichia coli occurs post-translationally as well as co-translationally. J. Biol. Chem. 256 2504–2507. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)69811-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadokura H., Beckwith J. (2009). Detecting folding intermediates of a protein as it passes through the bacterial translocation channel. Cell 138 1164–1173. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C. M., Chang H. C., Agashe V. R., Lakshmipathy S. K., Etchells S. A., Hayer-Hartl M., et al. (2006). Real-time observation of trigger factor function on translating ribosomes. Nature 444 455–460. 10.1038/nature05225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. J., Baker E. N. (2011). Intramolecular isopeptide bonds: protein crosslinks built for stress? Trends Biochem. Sci. 36 229–237. 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. J., Coulibaly F., Clow F., Proft T., Baker E. N. (2007). Stabilizing isopeptide bonds revealed in gram-positive bacterial pilus structure. Science 318 1625–1628. 10.1126/science.1145806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Irisawa T., Ohtani M., Muramatu M. (1992). Purification and characterization of proteinase In, a trypsin-like proteinase, in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 210 1007–1014. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17506.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebir M. O., Kendall D. A. (2002). SecA specificity for different signal peptides. Biochemistry 41 5573–5580. 10.1021/bi015798t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiler K. C. (2015). Mechanisms of ribosome rescue in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 285–297. 10.1038/nrmicro3438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama Y., Ito K. (1995). FtsH is required for proteolytic elimination of uncomplexed forms of SecY, an essential protein translocase subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 4532–4536. 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama Y., Ito K. (1996). A protease complex in the Escherichia coli plasma membrane: HflKC (HflA) forms a complex with FtsH (HflB), regulating its proteolytic activity against SecY. EMBO J. 15 6122–6131. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01000.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiino D. R., Phillips G. J., Silhavy T. J. (1990). Increased expression of the bifunctional protein PrlF suppresses overproduction lethality associated with exported beta-galactosidase hybrid proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172 185–192. 10.1128/jb.172.1.185-192.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. E., Hipp M. S., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U. (2013). Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82 323–355. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-092442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepsch M. M., Persson J. O., De Gier J. W. (2011). Consequences of the overexpression of a eukaryotic membrane protein, the human KDEL receptor, in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 407 532–542. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch N. T., Rudiger S., Schonfeld H. J., Driessen A. J., Schneider-Mergener J., Bukau B. (1999). Substrate specificity of the SecB chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 274 34219–34225. 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knupffer L., Fehrenbach C., Denks K., Erichsen V., Petriman N. A., Koch H. G. (2019). Molecular mimicry of SecA and signal recognition particle binding to the bacterial ribosome. mBio 10:e01317-19. 10.1128/mBio.01317-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar J., Alvira S., Schulze R. J., Martin R., Lycklama A. N. J. A., Lee S. C., et al. (2016). Membrane protein insertion and assembly by the bacterial holo-translocon SecYEG-SecDF-YajC-YidC. Biochem. J. 473 3341–3354. 10.1042/bcj20160545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer G., Rauch T., Rist W., Vorderwulbecke S., Patzelt H., Schulze-Specking A., et al. (2002). L23 protein functions as a chaperone docking site on the ribosome. Nature 419 171–174. 10.1038/nature01047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer G., Rutkowska A., Wegrzyn R. D., Patzelt H., Kurz T. A., Merz F., et al. (2004). Functional dissection of Escherichia coli trigger factor: unraveling the function of individual domains. J. Bacteriol. 186 3777–3784. 10.1128/jb.186.12.3777-3784.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer G., Shiber A., Bukau B. (2019). Mechanisms of cotranslational maturation of newly synthesized proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88 337–364. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A., Kreil G., Wickner W. (1986). Both hydrophobic domains of M13 procoat are required to initiate membrane insertion. EMBO J. 5 3681–3685. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04699.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto C. A., Beckwith J. (1983). Mutations in a new gene, secB, cause defective protein localization in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 154 253–260. 10.1128/jb.154.1.253-260.1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto C. A., Beckwith J. (1985). Evidence for specificity at an early step in protein export in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 163 267–274. 10.1128/jb.163.1.267-274.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto C. A., Francetic O. (1993). Highly selective binding of nascent polypeptides by an Escherichia coli chaperone protein in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 175 2184–2188. 10.1128/jb.175.8.2184-2188.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto C. A., Gannon P. M. (1988). Effects of Escherichia coli secB mutations on pre-maltose binding protein conformation and export kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 263 11554–11558. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)37994-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusukawa N., Yura T., Ueguchi C., Akiyama Y., Ito K. (1989). Effects of mutations in heat-shock genes groES and groEL on protein export in Escherichia coli. Embo J. 8 3517–3521. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08517.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeta C., Boyd D., Beckwith J. (2018). Disulfide bond formation in prokaryotes. Nat. Microbiol. 3 270–280. 10.1038/s41564-017-0106-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker S., Lill R., Ziegelhoffer T., Georgopoulos C., Bassford P. J., Jr., Kumamoto C. A., et al. (1989). Three pure chaperone proteins of Escherichia coli–SecB, trigger factor and GroEL–form soluble complexes with precursor proteins in vitro. EMBO J. 8 2703–2709. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08411.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Bernstein H. D. (2001). The targeting pathway of Escherichia coli presecretory and integral membrane proteins is specified by the hydrophobicity of the targeting signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 3471–3476. 10.1073/pnas.051484198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Bernstein H. D. (2002). Trigger factor retards protein export in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277 43527–43535. 10.1074/jbc.m205950200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R., Crooke E., Guthrie B., Wickner W. (1988). The “trigger factor cycle” includes ribosomes, presecretory proteins, and the plasma membrane. Cell 54 1013–1018. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90116-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R., Cunningham K., Brundage L. A., Ito K., Oliver D., Wickner W. (1989). SecA protein hydrolyzes ATP and is an essential component of the protein translocation ATPase of Escherichia coli. Embo J. 8 961–966. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03458.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B., Miyazaki R., Neher S., Siegele D. A., Ito K., Walter P., et al. (2013). Heat shock transcription factor sigma32 co-opts the signal recognition particle to regulate protein homeostasis in E. coli. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001735. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Topping T. B., Randall L. L. (1989). Physiological role during export for the retardation of folding by the leader peptide of maltose-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 9213–9217. 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. P., Topping T. B., Cover W. H., Randall L. L. (1988). Retardation of folding as a possible means of suppression of a mutation in the leader sequence of an exported protein. J. Biol. Chem, 263 14790–14793. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)68107-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Maciuba K., Kaiser C. M. (2019). The ribosome cooperates with a chaperone to guide multi-domain protein folding. Mol. Cell 74 310.e7–319.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manta B., Boyd D., Berkmen M. (2019). Disulfide bond formation in the periplasm of Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus 8. 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0012-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hackert E., Hendrickson W. A. (2009). Promiscuous substrate recognition in folding and assembly activities of the trigger factor chaperone. Cell 138 923–934. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz F., Boehringer D., Schaffitzel C., Preissler S., Hoffmann A., Maier T., et al. (2008). Molecular mechanism and structure of trigger factor bound to the translating ribosome. EMBO J. 27 1622–1632. 10.1038/emboj.2008.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minas W., Bailey J. E. (1995). Co-overexpression of prlF increases cell viability and enzyme yields in recombinant Escherichia coli expressing Bacillus stearothermophilus alpha-amylase. Biotechnol. Prog. 11 403–411. 10.1021/bp00034a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk A., Bukau B., Kampinga H. H. (2018). Cellular handling of protein aggregates by disaggregation machines. Mol. Cell 69 214–226. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson O. B., Muller-Lucks A., Kramer G., Bukau B., Von Heijne G. (2016). Trigger factor reduces the force exerted on the nascent chain by a cotranslationally folding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 428 1356–1364. 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak P., Dev I. K. (1988). Degradation of a signal peptide by protease IV and oligopeptidase A. J. Bacteriol. 170 5067–5075. 10.1128/jb.170.11.5067-5075.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Becker A. H., Sandikci A., Huber D., Chaba R., Gloge F., et al. (2011). Selective ribosome profiling reveals the cotranslational chaperone action of trigger factor in vivo. Cell 147 1295–1308. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D. B., Cabelli R. J., Dolan K. M., Jarosik G. P. (1990). Azide-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli alter the SecA protein, an azide-sensitive component of the protein export machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87 8227–8231. 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Liu G., Topping T. B., Cover W. H., Randall L. L. (1988). Modulation of folding pathways of exported proteins by the leader sequence. Science 239 1033–1035. 10.1126/science.3278378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzelt H., Rudiger S., Brehmer D., Kramer G., Vorderwulbecke S., Schaffitzel E., et al. (2001). Binding specificity of Escherichia coli trigger factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 14244–14249. 10.1073/pnas.261432298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G. J., Silhavy T. J. (1990). Heat-shock proteins DnaK and GroEL facilitate export of LacZ hybrid proteins in E. coli. Nature 344 882–884. 10.1038/344882a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogliano J., Lynch A. S., Belin D., Lin E. C., Beckwith J. (1997). Regulation of Escherichia coli cell envelope proteins involved in protein folding and degradation by the Cpx two-component system. Genes Dev. 11 1169–1182. 10.1101/gad.11.9.1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers T., Walter P. (1997). Co-translational protein targeting catalyzed by the Escherichia coli signal recognition particle and its receptor. Embo J. 16 4880–4886. 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugsley A. P. (1993). The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57 50–108. 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L. (1983). Translocation of domains of nascent periplasmic proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane is independent of elongation. Cell 33 231–240. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90352-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Crane J. M., Liu G., Hardy S. J. (2004). Sites of interaction between SecA and the chaperone SecB, two proteins involved in export. Protein Sci. 13 1124–1133. 10.1110/ps.03410104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Hardy S. J. (1986). Correlation of competence for export with lack of tertiary structure of the mature species: a study in vivo of maltose-binding protein in E. coli. Cell 46 921–928. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90074-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Hardy S. J. (2002). SecB, one small chaperone in the complex milieu of the cell. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 59 1617–1623. 10.1007/pl00012488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Henzl M. T. (2010). Direct identification of the site of binding on the chaperone SecB for the amino terminus of the translocon motor SecA. Protein Sci. 19 1173–1179. 10.1002/pro.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Topping T. B., Smith V. F., Diamond D. L., Hardy S. J. (1998a). SecB: a chaperone from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 290 444–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. L., Topping T. B., Suciu D., Hardy S. J. (1998b). Calorimetric analyses of the interaction between SecB and its ligands. Protein Sci. 7 1195–1200. 10.1002/pro.5560070514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport T. A. (2007). Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature 450 663–669. 10.1038/nature06384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolo K., Yu A. Y. H., Ologbenla A., Kim S. R., Zhu H., Ishimori K., et al. (2021). Functional cooperativity between the trigger factor chaperone and the ClpXP proteolytic complex. Nat. Commun. 12:281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati D., Scarlato V. (2017). Regulation of heat-shock genes in bacteria: from signal sensing to gene expression output. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41 549–574. 10.1093/femsre/fux015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R., Moradi S., Zarrine-Afsar A., Glover J. R., Kay L. E. (2013). Unraveling the mechanism of protein disaggregation through a ClpB-DnaK interaction. Science 339 1080–1083. 10.1126/science.1233066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R., Nillegoda N. B., Mayer M. P., Bukau B. (2019). The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20 665–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakr S., Cirinesi A. M., Ullers R. S., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2010). Lon protease quality control of presecretory proteins in Escherichia coli and its dependence on the SecB and DnaJ (Hsp40) chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 285 23506–23514. 10.1074/jbc.m110.133058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala A., Bordes P., Genevaux P. (2014). Multitasking SecB chaperones in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 5:666. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraogi I., Shan S. O. (2014). Co-translational protein targeting to the bacterial membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843 1433–1441. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer R. T., Baker T. A. (2011). AAA+ proteases: ATP-fueled machines of protein destruction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80 587–612. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-172623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffitzel C., Oswald M., Berger I., Ishikawa T., Abrahams J. P., Koerten H. K., et al. (2006). Structure of the E. coli signal recognition particle bound to a translating ribosome. Nature 444 503–506. 10.1038/nature05182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibich D., Gloge F., Pohner I., Bjorkholm P., Wade R. C., Von Heijne G., et al. (2016). Global profiling of SRP interaction with nascent polypeptides. Nature 536 219–223. 10.1038/nature19070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierle C. F., Berkmen M., Huber D., Kumamoto C., Boyd D., Beckwith J. (2003). The DsbA signal sequence directs efficient, cotranslational export of passenger proteins to the Escherichia coli periplasm via the signal recognition particle pathway. J. Bacteriol. 185 5706–5713. 10.1128/jb.185.19.5706-5713.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlieker C., Weibezahn J., Patzelt H., Tessarz P., Strub C., Zeth K., et al. (2004). Substrate recognition by the AAA+ chaperone ClpB. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 607–615. 10.1038/nsmb787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O., Schuenemann V. J., Hand N. J., Silhavy T. J., Martin J., Lupas A. N., et al. (2007). prlF and yhaV encode a new toxin-antitoxin system in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 372 894–905. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze R. J., Komar J., Botte M., Allen W. J., Whitehouse S., Gold V. A., et al. (2014). Membrane protein insertion and proton-motive-force-dependent secretion through the bacterial holo-translocon SecYEG-SecDF-YajC-YidC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 4844–4849. 10.1073/pnas.1315901111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H., Nishiyama K., Tokuda H. (1997). Expression of gpsA encoding biosynthetic sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase suppresses both the LB- phenotype of a secB null mutant and the cold-sensitive phenotype of a secG null mutant. Mol. Microbiol. 26 1013–1021. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6392003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Kraft C., Jaiswal R., Sejwal K., Kasaragod V. B., Kuper J., et al. (2014). Cryo-electron microscopic structure of SecA Bound to the 70S Ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 289 7190–7199. 10.1074/jbc.m113.506634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder W. B., Silhavy T. J. (1992). Enhanced export of beta-galactosidase fusion proteins in prlF mutants is Lon dependent. J. Bacteriol. 174 5661–5668. 10.1128/jb.174.17.5661-5668.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone M., Kishigami S., Yoshihisa T., Ito K. (1997). Roles of disulfide bonds in bacterial alkaline phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 272 6174–6178. 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg R., Knupffer L., Origi A., Asti R., Koch H. G. (2018). Co-translational protein targeting in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 365:fny095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner D., Forrer P., Stumpp M. T., Pluckthun A. (2006). Signal sequences directing cotranslational translocation expand the range of proteins amenable to phage display. Nat. Biotechnol. 24 823–831. 10.1038/nbt1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani K., Shiozuka K., Tokuda H., Mizushima S. (1989). In vitro analysis of the process of translocation of OmpA across the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic membrane. A translocation intermediate accumulates transiently in the absence of the proton motive force. J. Biol. Chem. 264 18582–18588. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)51507-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschke C. M., Kim J., Song T., Park S., Park C., Randall L. L. (1991). Mutations that affect the folding of ribose-binding protein selected as suppressors of a defect in export in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266 11789–11796. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)99026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian P., Andricioaei I. (2006). Size, motion, and function of the SecY translocon revealed by molecular dynamics simulations with virtual probes. Biophys. J. 90 2718–2730. 10.1529/biophysj.105.073304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu T., Gamer J., Bukau B., Kanemori M., Mori H., Rutman A. J., et al. (1995). Escherichia coli FtsH is a membrane-bound, ATP-dependent protease which degrades the heat-shock transcription factor sigma 32. EMBO J. 14 2551–2560. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07253.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trun N. J., Silhavy T. J. (1987). Characterization and in vivo cloning of prlC, a suppressor of signal sequence mutations in Escherichia coli K12. Genetics 116 513–521. 10.1093/genetics/116.4.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trun N. J., Silhavy T. J. (1989). PrlC, a suppressor of signal sequence mutations in Escherichia coli, can direct the insertion of the signal sequence into the membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 205 665–676. 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90312-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsirigotaki A., De Geyter J., Sostaric N., Economou A., Karamanou S. (2017). Protein export through the bacterial Sec pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15 21–36. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K., Mori H., Mizushima S. (1995). Stepwise movement of preproteins in the process of translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270 30862–30868. 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrandt N. D., Newitt J. A., Bernstein H. D. (1997). The E. coli signal recognition particle is required for the insertion of a subset of inner membrane proteins. Cell 88 187–196. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81839-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullers R. S., Ang D., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2007). Trigger Factor can antagonize both SecB and DnaK/DnaJ chaperone functions in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 3101–3106. 10.1073/pnas.0608232104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent Q. A., De Gier J. W., Von Heijne G., Kendall D. A., Ten Hagen-Jongman C. M., Oudega B., et al. (1997). Nascent membrane and presecretory proteins synthesized in Escherichia coli associate with signal recognition particle and trigger factor. Mol. Microbiol. 25 53–64. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4431808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg B., Clemons W. M., Jr., Collinson I., Modis Y., Hartmann E., Harrison S. C., et al. (2004). X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 427 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis E. O., Driessen A. J. (2006). Stepwise evolution of the Sec machinery in Proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 14 105–108. 10.1016/j.tim.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stelten J., Silva F., Belin D., Silhavy T. J. (2009). Effects of antibiotics and a proto-oncogene homolog on destruction of protein translocator SecY. Science 325 753–756. 10.1126/science.1172221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. (1990). The signal peptide. J. Membr. Biol. 115 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]