Abstract

Background

Eczema and food allergy are common health conditions that usually begin in early childhood and often occur together in the same people. They can be associated with an impaired skin barrier in early infancy. It is unclear whether trying to prevent or reverse an impaired skin barrier soon after birth is effective in preventing eczema or food allergy.

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess effects of skin care interventions, such as emollients, for primary prevention of eczema and food allergy in infants

Secondary objective

To identify features of study populations such as age, hereditary risk, and adherence to interventions that are associated with the greatest treatment benefit or harm for both eczema and food allergy.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to July 2020: Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase. We searched two trials registers and checked reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews for further references to relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We contacted field experts to identify planned trials and to seek information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

Selection criteria

RCTs of skin care interventions that could potentially enhance skin barrier function, reduce dryness, or reduce subclinical inflammation in healthy term (> 37 weeks) infants (0 to 12 months) without pre‐existing diagnosis of eczema, food allergy, or other skin condition were included. Comparison was standard care in the locality or no treatment. Types of skin care interventions included moisturisers/emollients; bathing products; advice regarding reducing soap exposure and bathing frequency; and use of water softeners. No minimum follow‐up was required.

Data collection and analysis

This is a prospective individual participant data (IPD) meta‐analysis. We used standard Cochrane methodological procedures, and primary analyses used the IPD dataset. Primary outcomes were cumulative incidence of eczema and cumulative incidence of immunoglobulin (Ig)E‐mediated food allergy by one to three years, both measured by the closest available time point to two years. Secondary outcomes included adverse events during the intervention period; eczema severity (clinician‐assessed); parent report of eczema severity; time to onset of eczema; parent report of immediate food allergy; and allergic sensitisation to food or inhalant allergen.

Main results

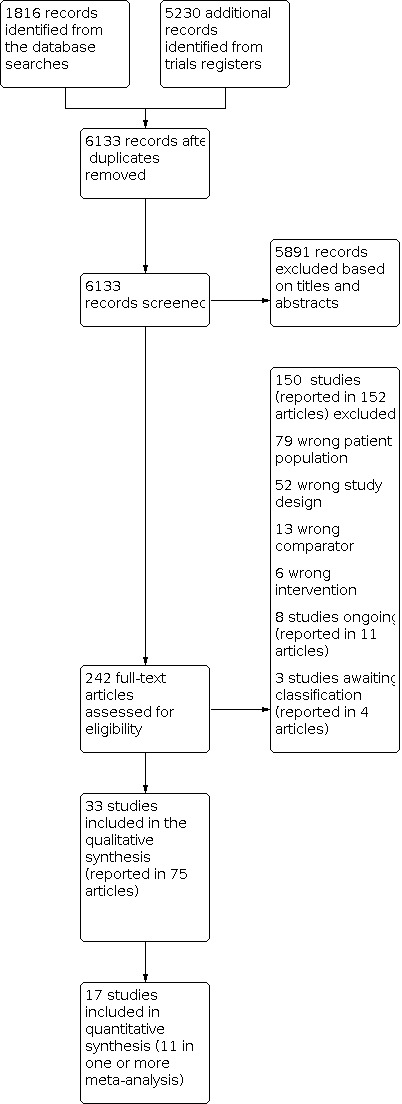

This review identified 33 RCTs, comprising 25,827 participants. A total of 17 studies, randomising 5823 participants, reported information on one or more outcomes specified in this review. Eleven studies randomising 5217 participants, with 10 of these studies providing IPD, were included in one or more meta‐analysis (range 2 to 9 studies per individual meta‐analysis).

Most studies were conducted at children's hospitals. All interventions were compared against no skin care intervention or local standard care. Of the 17 studies that reported our outcomes, 13 assessed emollients. Twenty‐five studies, including all those contributing data to meta‐analyses, randomised newborns up to age three weeks to receive a skin care intervention or standard infant skin care. Eight of the 11 studies contributing to meta‐analyses recruited infants at high risk of developing eczema or food allergy, although definition of high risk varied between studies. Durations of intervention and follow‐up ranged from 24 hours to two years.

We assessed most of this review's evidence as low certainty or had some concerns of risk of bias. A rating of some concerns was most often due to lack of blinding of outcome assessors or significant missing data, which could have impacted outcome measurement but was judged unlikely to have done so. Evidence for the primary food allergy outcome was rated as high risk of bias due to inclusion of only one trial where findings varied when different assumptions were made about missing data.

Skin care interventions during infancy probably do not change risk of eczema by one to two years of age (risk ratio (RR) 1.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.31; moderate‐certainty evidence; 3075 participants, 7 trials) nor time to onset of eczema (hazard ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.14; moderate‐certainty evidence; 3349 participants, 9 trials). It is unclear whether skin care interventions during infancy change risk of IgE‐mediated food allergy by one to two years of age (RR 2.53, 95% CI 0.99 to 6.47; 996 participants, 1 trial) or allergic sensitisation to a food allergen at age one to two years (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.69; 1055 participants, 2 trials) due to very low‐certainty evidence for these outcomes. Skin care interventions during infancy may slightly increase risk of parent report of immediate reaction to a common food allergen at two years (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.61; low‐certainty evidence; 1171 participants, 1 trial). However, this was only seen for cow’s milk, and may be unreliable due to significant over‐reporting of cow’s milk allergy in infants. Skin care interventions during infancy probably increase risk of skin infection over the intervention period (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.77; moderate‐certainty evidence; 2728 participants, 6 trials) and may increase risk of infant slippage over the intervention period (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.99; low‐certainty evidence; 2538 participants, 4 trials) or stinging/allergic reactions to moisturisers (RR 2.24, 95% 0.67 to 7.43; low‐certainty evidence; 343 participants, 4 trials), although confidence intervals for slippages and stinging/allergic reactions are wide and include the possibility of no effect or reduced risk.

Preplanned subgroup analyses show that effects of interventions were not influenced by age, duration of intervention, hereditary risk, FLG mutation, or classification of intervention type for risk of developing eczema. We could not evaluate these effects on risk of food allergy. Evidence was insufficient to show whether adherence to interventions influenced the relationship between skin care interventions and risk of developing eczema or food allergy.

Authors' conclusions

Skin care interventions such as emollients during the first year of life in healthy infants are probably not effective for preventing eczema, and probably increase risk of skin infection. Effects of skin care interventions on risk of food allergy are uncertain.

Further work is needed to understand whether different approaches to infant skin care might promote or prevent eczema and to evaluate effects on food allergy based on robust outcome assessments.

Plain language summary

Skin care interventions for preventing eczema and food allergy

Does moisturising baby skin prevent eczema or food allergies?

Key messages

Skin care treatments in babies, such as using moisturisers on the skin during the first year of life, probably do not stop them from developing eczema, and probably increase the chance of skin infection.

We are uncertain how skin care treatments might affect the chances of developing a food allergy. We need evidence from well‐conducted studies to determine effects of skin care on food allergies in babies.

What are allergies?

An immune response is how the body recognises and defends itself against substances that appear harmful. An allergy is a reaction of the body's immune system to a particular food or substance (an allergen) that is usually harmless. Different allergies affect different parts of the body, and their effects can be mild or serious.

Food allergies and eczema

Eczema is a common skin allergy that causes dry, itchy, cracked skin. Eczema is common in children, often developing before their first birthday. It is sometimes a long‐lasting condition, but it may improve or clear as a child gets older.

Allergies to food can cause itching in the mouth, a raised itchy red rash, swelling of the face, stomach symptoms or difficulty breathing. They usually happen within 2 hours after a food is eaten.

People with food allergies often have other allergic conditions, such as asthma, hay fever, and eczema.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to learn how skin care affects the risk of a baby developing eczema or food allergies. Skin care treatments included:

• putting moisturisers on a baby's skin;

• bathing babies with water containing moisturisers or moisturising oils;

• advising parents to use less soap, or to bathe their child less often; and

• using water softeners.

We also wanted to know if these skin care treatments cause any unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies of different types of skin care for healthy babies (aged up to one year) with no previous food allergy, eczema, or other skin condition.

Search date: we included evidence published up to July 2020.

We were interested in studies that reported:

• how many children developed eczema, or food allergy, by age one to three years;

• how severe the eczema was (assessed by a researcher and by parents);

• how long it took for eczema to develop;

• parents' reports of immediate (under two hours) reactions to a food allergen;

• how many children developed sensitivity to a particular food allergen; and

• any unwanted effects.

We assessed the strengths and weaknesses of each study to determine how reliable the results might be. We then combined the results of all relevant studies and looked at overall effects.

What we found

We found 33 studies involving 25,827 babies. These studies took place in Europe, Australia, Japan, and the USA, most often at children's hospitals. Skin care was compared against no skin care or care as usual (standard care). Treatment and follow‐up times ranged from 24 hours to two years. Many studies (13) tested the use of moisturisers; others mainly tested the use of bathing and cleansing products and how often they were used.

We combined the results of 11 studies; eight included babies thought to have high risk of developing eczema or a food allergy.

What are the main results of our review?

Compared to no skin care or standard care, moisturisers:

• probably do not change the risk of developing eczema by the age of one to two years (evidence from 7 studies in 3075 babies) nor the time needed for eczema to develop (9 studies; 3349 babies);

• may slightly increase the number of immediate reactions to a common food allergen at two years, as reported by parents (1 study; 1171 babies);

• probably cause more skin infections (6 studies; 2728 babies);

• may increase unwanted effects, such as a stinging feeling or an allergic reaction to moisturisers (4 studies; 343 babies); and

• may increase the chance of babies slipping (4 studies; 2538 babies).

We are uncertain whether skin care treatments affect the chance of developing a food allergy as assessed by a researcher (1 study; 996 babies) or sensitivity to food allergens (2 studies; 1055 babies) at age one to two years.

Confidence in our results

We are moderately confident in our results for developing eczema and the time needed to develop eczema. These results might change if more evidence becomes available. We are less confident about our results for food allergy or sensitivity, which are based on small numbers of studies with widely varied results. These results are likely to change when more evidence is available. Our confidence in our findings for skin infections is moderate but is low for stinging or allergic reactions and slipping.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Skin care intervention compared to standard skin care or no skin care intervention for the prevention of eczema and food allergy.

|

Patient or population: infants age 12 months or younger Setting: prevention Intervention: skin care intervention Comparison: standard skin care or no skin care intervention |

|||||||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||||

| Outcome | Standard care | Skin care intervention | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Eczema diagnosis by 1 to 2 years | 150 per 1000 | 155 per 1000 (122 to 197) | RR 1.03 (0.81 to 1.31) | 3075 (7) | MODERATEa | In sensitivity analysis that included studies that measured eczema using Hanifin and Rajka, or UK Working Party methods only, total N = 2919(6), the pooled treatment effect for eczema by 1 to 2 years was RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.34. In a separate sensitivity analysis including studies rated as low risk of bias only, total N = 1739(3), the pooled treatment effect for eczema by 1 to 2 years was RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.17 | |

| IgE‐mediated food allergy (oral food challenge) by 1 to 2 years | 50 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (50 to 335) | RR 2.53 (0.99 to 6.47) | 996 (1) | VERY LOWb | In a sensitivity analysis that examined IgE‐mediated food allergy as measured by oral food challenge or based upon a panel assessment of clinical history and/or allergic sensitisation by 1 to 2 years, total N = 1115 (1), was RR = 1.46, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.34. For parent report of a doctor diagnosis of food allergy at 1 to 2 years, total N = 1614 (3), and the pooled treatment effect was RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.31. No low risk of bias sensitivity analysis was possible | |

| Slippages (over the intervention period) | 20 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (14 to 87) | RR 1.42 (0.67 to 2.99) | 2538 (4) | LOWc | ‐ | |

| Skin infection (over the intervention period) | 50 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (51 to 89) | RR 1.34 (1.02 to 1.77) | 2728 (6) | MODERATEd | ‐ | |

| Stinging/allergic reactions to moisturisers (over the intervention period) | 40 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 (27 to 298) | RR 2.24 (0.67 to 7.43) | 343 (4) | LOWc | ‐ | |

| Time to onset of eczema | 24 months | 27.9 months (21.1 to 36.9 months) | HR 0.86 (0.65 to 1.14) | 3349 (9) | MODERATEe | ‐ | |

| Parent report of immediate reaction to common food allergen (at 2 years) | 160 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (160 to 258) | RR 1.27 (1.00 to 1.61) | 1171 (1) | LOWf | ‐ | |

| Allergic sensitisation to a food allergen (at 1 to 2 years) | 90 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (26 to 242) | RR 0.86 (0.28 to 2.69) | 1055 (2) | VERY LOWg | ‐ | |

aDowngraded one level for heterogeneity driven by one trial contributing 21.8% of the weight of the analysis, for which the review authors were unable to identify a plausible explanation.

bDowngraded one level for overall high risk of bias due to missing data (29%), and two levels for imprecision due to small numbers of events from a single study, with wide confidence intervals, which include both a harmful effect and no effect.

cDowngraded by two levels for imprecision due to small numbers of events, with wide confidence intervals, which include both a harmful effect and a beneficial effect.

dDowngraded by one level for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, which include both a harmful effect and no effect.

eDowngraded one level for heterogeneity driven by more than one trial, for which review authors were unable to identify a plausible explanation.

fDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to small numbers of events from a single study, with wide confidence intervals, which include both a harmful effect and no effect.

gDowngraded one level for heterogeneity, for which the review authors were unable to identify a plausible explanation, and two levels for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, which include both a harmful and a beneficial effect.

Background

Please see Table 2 for explanations of specific terms used in this review.

1. Glossary of terms.

| Term | Definition |

| Adolescence | A period in development, roughly between ages 10 and 19 years, between onset of puberty and acceptance of adult identity and behaviour |

| Allergic (atopic) march | Typical pattern of onset of allergic disease from eczema, to food allergy, to asthma and allergic rhinitis |

| Allergic rhinitis | Rhinitis is a group of symptoms affecting the nose, typically by sneezing, itching, or congestion. Allergic rhinitis occurs when these symptoms are due to environmental allergies |

| Allergic sensitisation | Demonstrated by a positive skin prick test of specific IgE to a known allergen |

| Anaphylaxis | Acute, potentially life‐threatening immediate reaction to an allergen |

| Angioedema | Pronounced swelling of the deep dermis, subcutaneous or submucosal tissue |

| Atopic dermatitis (atopic eczema) |

Eczema with IgE sensitisation, either by IgE antibody or by skin prick test, is classified as atopic eczema |

| Atopy | Genetic predisposition to develop allergic diseases such as eczema, food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, often associated with production of IgE antibodies |

| Ceramides | Lipid (fatty) molecules found in the lipid bilayer of the intercellular matrix |

| Eczema | Complex chronic skin condition characterised by itch, a form of dermatitis |

| Filaggrin gene (FLG) | Gene encoding for filaggrin, which is a filament‐binding protein in the skin |

| Flare | In eczema, a period of worsening of signs and symptoms of eczema |

| Food allergy | Adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food. Can be IgE‐mediated or non‐IgE‐mediated |

| Food sensitisation | Production of IgE to a food, in the form of a positive skin prick test or immunoglobulin E; may not equate to food allergy |

| Humectant | Substance or product that draws water towards it |

| Immunoglobulin E (IgE) | Class of antibody that plays a key role in allergic disease. Signs and symptoms of IgE‐mediated disease include urticaria, angioedema, wheeze, anaphylaxis |

| Infant | A baby in the first year of life |

| Inhalant allergen | Allergen that typically enters the immune system via the respiratory tract and is airborne, such as house dust mite or pollen |

| Mast cell | Granular basophil cell present in connective tissue that releases histamine and other mediators in allergic reactions |

| Neonate | A baby in the first 28 days of life |

| Phenotype | Observable characteristics from an interaction between genes and the environment |

| Prevalence | In statistics, refers to the number of cases of a disease, present in a particular population at a given time |

| Quality of life | Defined by WHO as individuals' perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns |

| Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) | Non‐invasive measurement of water loss across the epidermis used as a measure of skin barrier function |

| Urticaria | Rash that is a transient erythematous itchy swelling of skin |

Description of the condition

Allergic diseases such as eczema and food allergy are some of the most common long‐term health conditions in children and young people (Bai 2017; Van Cleave 2010). There is no definitive cure for allergic disease, although treatments can be used to alleviate symptoms. The burden of allergic disease on the individual, the family, and society is significant (Gupta 2004; Pawankar 2014). The prevalence of allergic disease appears to have increased; traditionally, higher prevalence was seen in high‐income countries, but prevalence of allergic disease is now increasing in urban cities of low‐ and middle‐income countries (Deckers 2012; Prescott 2013).

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder, diagnosed clinically based on a collection of symptoms, primarily including itch. Its aetiology is complex and involves interaction between genes, environment, the immune system, and impairment of the skin barrier (Leung 2004). Eczema with immunoglobulin (Ig)E sensitisation, either by IgE antibody or by skin prick test, is classified as atopic eczema (Johansson 2003). This review is focused on prevention of eczema and food allergy in infants and children and does not address adult‐onset eczema, which has different associations from childhood atopic eczema (Abuabara 2019). Likewise this review does not address adult‐onset food allergy, which accounts for a small proportion of food allergy among adults, resulting in loss of tolerance to a food that the adult previously tolerated (Ramesh 2017).

Atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) is most often associated with other atopic diseases and typically presents in younger children; it may be the first step along the so called 'allergic march' (Leung 2004). Eczema often occurs in families with atopic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis/hay fever (and food allergy), and atopic eczema. These diseases share a common pathogenesis and are frequently present together in the same individual and family. The word 'atopy' refers to the genetic tendency to produce IgE antibodies in response to small quantities of common environmental proteins such as pollen, house dust mites, and food allergens (Stone 2002; Thomsen 2015). Around 30% of people with eczema develop asthma, and 35% develop allergic rhinitis (Luoma 1983). However, it is known that atopy does not concurrently occur in all people with atopic eczema. In view of this, it has been proposed that the term 'eczema' should be used to define people both with and without atopy. In agreement with the 'Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use' (Johansson 2003), and similar to other Cochrane Reviews evaluating eczema therapies (Van Zuuren 2017), we will therefore use the term 'eczema' throughout the review.

The main mechanism of this disease is the combination of an epidermal barrier function defect and cutaneous inflammation. Barrier dysfunction can be attributed in part to a genetic susceptibility, such as a mutation in the filaggrin gene (FLG). Cutaneous inflammation is demonstrated by inflammatory cell infiltration of the dermis, predominantly by Th2 cells (Weidinger 2016).

Eczema is diagnosed clinically by its appearance and its predilection for certain skin sites, which is age‐dependent (Spergel 2003). In a research setting, the most commonly used diagnostic criteria are the UK Working Party Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (Williams 1994). Prevalence of eczema is reported at up to 20% in children and may be increasing (Flohr 2014). Eczema has a significant impact on the patient and the family. In childhood, eczema is often associated with sleep disturbance and behavioural difficulties. Eczema also significantly impacts the quality of life of parents of affected children. Partaking in their children's treatment can take up to two hours per day, their own sleep is often disturbed along with their child's, and this exacerbates the distress experienced (Carroll 2005). The impact of moderate to severe eczema on family dynamics is comparable to that of other chronic health conditions such as type 1 diabetes (Su 1997). The financial cost of childhood eczema incorporates both the direct cost of the child's care and the indirect costs of parental time off work and decreased productivity due to decreased sleep and increased stress. The total cost of eczema care in the USA has been estimated at over USD 5 billion per annum (Drucker 2017).

Eczema often improves during childhood, with more than 50% of childhood eczema resolving by adolescence (Williams 1998). Recent studies suggest that some aspects of skin barrier and immune dysfunction may persist into adulthood (Abuabara 2018). Adult eczema is estimated at approximately 5% in the USA and 2% in Japan (Barbarot 2018). Adults with eczema have significantly decreased social functioning and greater psychological distress than both the general population and adults with some other long‐term conditions (Carroll 2005). In a recent systematic review, a positive association was seen between eczema and suicidal ideation in adults and adolescents. It was proposed that chronic itch, sleep disturbance, and the social stigma of a visible disease contribute to mental health effects (Ronnstad 2018).

As is seen in most disease prevalence studies, reported prevalence of eczema may vary depending on the location of the trial and variation in measurements used for classification and diagnosis. Using consistent measurements, the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) has shown an increase in reporting of eczema across different settings and in different populations apart from those with already high prevalence (Asher 2006). Admittedly, the youngest children in this cohort were six to seven years old ‐ not preschool age, at which eczema prevalence can be higher. This variation in reported prevalence between different regions and over time suggests that environmental influences may contribute significantly to disease prevalence. Eczema has been associated with smaller families, higher social class, and urban living. Children of immigrants moving from a country with low eczema prevalence to a country with higher eczema prevalence have a relatively higher prevalence of eczema, supporting a role for environmental factors acting during early life (Martin 2013). Family history of eczema, that is, genetics, is the strongest determinant of eczema, and it cannot be modified (Apfelbacher 2011). However interaction of genes with environmental factors may be influenced by skin barrier interventions.

Food allergy has been defined as an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food (Boyce 2010). Food allergy can be further classified into IgE‐mediated, non‐IgE‐mediated, and mixed types. IgE‐mediated food allergy typically occurs within two hours of exposure to the offending food, and symptoms are well characterised, ranging from minor oral or gastrointestinal symptoms, urticaria, or angioedema to more severe symptoms such as anaphylaxis, which can occasionally result in death (Boyce 2010). IgE‐mediated reactions involve degranulation of mast cells, and the condition is diagnosed by a clinical history supported by skin prick or serum‐specific IgE testing. A positive test alone indicates sensitisation to the food but does not always predict clinical reactivity. The titre of IgE or the size of the skin prick test wheal is a predictor of clinical reactivity, although not an indication of the severity of a reaction. Oral food challenges ‐ either open or blinded placebo‐controlled challenges ‐ are used to confirm the diagnosis in cases where the clinical history and test results are inconclusive (Bock 1988). Non‐IgE‐mediated food allergy and mixed food allergies have a slower onset and less specific symptoms. Diagnosis is more difficult and relies on clinical history supported by exclusion or reintroduction of suspected foods, or both (Johansson 2003). It is unclear whether non‐IgE‐mediated allergies have the same association with skin barrier function and eczema; therefore we will not consider non‐IgE‐mediated food allergies in this review.

Exact prevalence rates for food allergy are difficult to ascertain and are largely dependent on the method used to diagnose food allergy and the population studied. Self‐reported food allergy rates are generally higher than those confirmed by specific allergy testing (Woods 2002). Previous population‐based studies have suggested that IgE‐mediated food allergy affects around 3% to 10% of children (Kelleher 2016; Osbourne 2011; Venter 2008). For some people, food allergy can resolve spontaneously during childhood, particularly for foods such as milk and egg. However a recent US survey study identified a history suggestive of IgE‐mediated food allergy in over 10% of adults, demonstrating that it is not just a disease of childhood (Gupta 2019). Like eczema, food allergy is thought to have increased in prevalence in recent decades, although epidemiological data from the 1990s onwards in England and Australia suggest that food allergy prevalence in young children may be stable (Peters 2018 ; Prescott 2013; Sicherer 2003; Venter 2008). Food allergy also varies in prevalence across different regions, with lower prevalence in areas with lower overall rates of allergic disease, such as rural settings in Asia and Africa (Botha 2019; Prescott 2013).

Food allergy is a considerable burden on the individual, the family, and wider society. Acute reactions can cause significant anxiety and when severe may rarely result in a fatal outcome within minutes of food ingestion (Umasunthar 2013). The continuous vigilance required to avoid potential triggers has an adverse impact on quality of life of allergic children and adults and their families (Knibb 2010). People with food allergy and their carers report a negative impact of dietary restrictions, limitations to social activities, and an emotional and financial burden of living with food allergy. For example, in the USA, the financial cost of food allergy for affected families and healthcare providers has been estimated as at least USD 25 billion per annum (Gupta 2013). In recent decades, numbers of hospital admissions for food‐related anaphylaxis have increased. It is unclear however whether this represents a true increase in incidence or greater recognition of the potential for acute food allergy as a cause of symptoms, as there has not been a concomitant increase in fatal anaphylaxis (Jerschow 2014; Poulos 2007; Turner 2015).

Eczema and food allergy are closely associated. Both conditions typically begin during the first year of life. Genetic variations that damage skin barrier function are associated with both eczema and food allergy (Palmer 2006; Van den Oord 2009). In particular, FLG mutation ‐ a mutation in the gene encoding for filaggrin binding protein in the epidermis ‐ has been the most widely studied of the genes associated with atopy. Those with a mutation have significantly increased prevalence of eczema and food allergy (Irvine 2011). Animal studies demonstrate that exposure to food allergen across a damaged skin barrier predisposes to food sensitisation (Strid 2004; Strid 2005). Human observational studies support an onset timing and severity‐dependent relationship between childhood eczema and risk of food allergy. In Martin 2015, over 50% of infants who needed prescription topical steroids before three months of age for treatment of eczema were IgE‐sensitised to one or more of egg white, peanut, or sesame. This study was included in a systematic review, which demonstrated a strong dose‐dependent relationship between eczema food sensitisation and food allergy, and suggested that eczema may be an important cause of food allergy (Tsakok 2016).

With regards to primary prevention of eczema, some studies have suggested that maternal supplementation with a probiotic supplement during pregnancy and breastfeeding may reduce risk of eczema (Garcia‐Larsen 2018). However the mechanism of action of such an intervention is unclear, findings are inconsistent between trials, and few of the relevant studies have published protocols that confirm the absence of selective reporting.

With regards to primary prevention of food allergy, it has been shown that early introduction of allergenic foods such as egg and peanut can decrease the risk of allergy to those foods (Du Toit 2015; Ierodiakonou 2016; Natsume 2017; Perkin 2016). However, it is unclear whether this approach will reduce the prevalence of food allergy at a population level because applying the intervention to multiple foods is likely to be too onerous for some parents (Voorheis 2019), and some children already have allergy to the food before the age when complementary foods are usually introduced (Du Toit 2015).

New approaches are therefore required for prevention of eczema and food allergy; simple interventions designed to promote skin barrier function represent one potential approach.

Description of the intervention

In this review we included all interventions designed to improve the skin barrier in infants, either by enhancement or by promotion of the barrier through hydration via directly applied topical products such as emollients or moisturisers or through reduction of potential damage to the skin barrier and consequent dryness through various means such as avoiding soaps or reducing water hardness. We expected promotion of the skin barrier and skin hydration through topical emollients would be the most widely used intervention. Emollients are described as mainly lipid‐based products that smooth the skin, whereas moisturisers give water and moisture to the skin (Penzer 2012). However, sometimes 'emollient' is referred to as an ingredient of 'moisturisers' (Lodén 2012). There is not yet a clear nomenclature for topical preparations for the skin. The terms 'moisturiser' and 'emollient' are used interchangeably in different settings to describe directly applied topical products. Several different 'classes' or 'formulations' of emollients and moisturisers are available, including oil‐in‐water creams, water‐in‐oil creams, ointments, lotions, oils, gels, sprays, and emulsions (Van Zuuren 2017). However these may not reflect accurately the format, ingredient, and effects of the product. Further complicating this is the fact that many skin care products are classed as cosmetics and therefore are not subjected to the same regulations as medicines. A recently proposed classification includes considering the vehicle, the formulation, and the active ingredients (Surber 2017).

Emollients themselves may be categorised by their mode of use, as leave‐on emollients that are directly applied to the skin and allowed to dry in; as soap substitutes whereby an emollient may be used instead of a soap to clean; and as bath oils or emollients by which a product is added to the bath water (Van Zuuren 2017). In this review we expect most intervention trials to use leave‐on emollients, although the characteristics of emollients may vary.

As part of treatment for established eczema, emollients are recommended to be applied two to three times a day, at up to 150 g to 200 g per week in young children and up to 500 g in adults (Eichenfield 2014; Ring 2012). Overall, emollients are regarded as safe, with few adverse effects. However, daily application of sufficient emollient can be time‐consuming and unpleasant, having a negative impact on the child and the family (Carroll 2005). Certain emollients can cause stinging, especially to skin with established eczema (Oakley 2016). There is concern that emollients can actively sensitise to their individual components, leading to cutaneous reactions (Danby 2011), and even systemic allergic reactions (Voskamp 2014). Slippage of infants covered in emollient from the hands of carers is a stated potential adverse reaction in emollient prevention studies such as the BEEP study (Chalmers 2017).

Protection of the skin barrier could also be achieved by limiting water loss across the skin, or by limiting skin contact with potentially harmful substances or irritants. Activities and substances that may harm the skin barrier, at least in people with established eczema, include excessive bathing, wash products, and hard water (Cork 2002). Thus, ameliorating any of these factors in the first months of life may potentially improve hydration and skin barrier function, thereby reducing subsequent eczema prevalence.

Neonatal skin is different from the skin of children and adults, as it takes time to adjust to the dry extrauterine environment during the postnatal period (Cooke 2018). Postnatal maturation of skin structure and physiology can take up to a year, with regional differences in maturation, with cheek skin maturing more slowly than skin at other sites (McAleer 2018). However, very early neonatal skin has decreased water permeability compared to the skin of older children and adults, along with decreased surface pH and stratum corneum formation, demonstrating an effective skin barrier in the first two days of life, which changes rapidly (Yosipovitch 2000). It was previously thought that infant skin beyond the first few weeks following birth was structurally and functionally equivalent to the skin of adults; however skin undergoes a maturation process that can last for several years after birth (Chiou 2004; Stamatas 2011; Visscher 2017). This process involves higher keratinocyte proliferation and desquamation rates with impaired keratinocyte differentiation compared to adults (Liu 2018; Stamatas 2010). The increased keratinocyte cell turnover results in smaller corneocytes and a thinner stratum corneum (Stamatas 2010). These changes in the stratum corneum create a shorter path for penetration of irritants and allergens through the skin of normal babies. The increased permeability of a baby's stratum corneum compared to that of an adult is reflected in higher transepidermal water loss (TEWL) rates (Nikolovski 2008). This higher stratum corneum permeability is likely to be an important factor in the development of eczema early in life. Infants, with their thinner skin and an increased body surface area‐to‐volume ratio compared with adults, may be more susceptible to percutaneous uptake of any potentially harmful substances (Mancini 2008).

Standard care for neonatal and infant skin differs internationally and is affected by cultural factors. The World Health Organization recommends not bathing newborn infants in the first 24 hours after birth but does not recommend any specific method of infant skin care beyond this time (WHO 2015). In the UK, standard skin care advice given to parents of newborns is to wash in plain water for the first month and to use a mild non‐perfumed soap if one is required. What constitutes a 'mild soap' is not described, and there is no set recommendation for bathing frequency or use of moisturisers (NICE 2006). Few emollient studies have included term infants; most have incorporated premature infants, whose skin is different from the skin of term infants (Irvin 2015). Application of an emollient or oil to the skin of newborn infants is practised in some regions and cultures for a variety of reasons often unrelated to allergy prevention (Amare 2015).

Timing of the first bath in neonates may be important. In some areas of the world, infants are washed immediately after birth, but the World Health Organization recommends leaving the vernix caseosa intact and allowing it to wear off with normal handling (WHO 2015). When modes of washing were compared, a comparison of infant bathing with water versus washing with a cotton wash cloth did not demonstrate a significant difference in skin barrier properties after four weeks but did show regional differences in skin barrier properties and demonstrated dynamic adaption of the skin barrier over the first four weeks of life (Garcia Bartels 2009). Among neonates bathed twice weekly, those washed in age‐appropriate liquid cleanser with added cream had lower transepidermal water loss (TEWL) than those washed with water only, whereas stratum corneum hydration was similar. Whether this shows improvement in the skin barrier is unclear (Garcia Bartels 2010). Although specific wash products or moisturiser ingredients such as sodium laureth sulfate are thought to be harmful, plain water or wash products without known skin irritants are thought to be safe, other than the risk of slippages with oil‐based products (Blume‐Peytavi 2016). Some groups recommend pharmaceutical‐grade oils or specially formulated baby skin products over locally produced oils that are traditionally used in many parts of the world (Blume‐Peytavi 2016). However, such recommendations sometimes come from industry‐funded groups, and there is little direct evidence to suggest that traditional local oils are inferior to commercial products. Frequency and timing of infant bathing may vary by culture and region, and although excessively frequent infant bathing is thought to harm skin barrier function and physiology, the optimal frequency of infant washing or bathing is not known.

Hard water is relatively rich in calcium and magnesium, and water hardness varies depending on geographical location. Water of a certain hardness will cause limescale and may corrode pipes (Ewence 2011). Hard water is associated with increased eczema prevalence (Engebretsen 2017). It is thought that the skin barrier disruption associated with hard water is due to the interaction between surfactants in wash products and hard water itself (Danby 2018).

This review covers all potential skin care interventions designed to promote, or reduce damage to, the skin barrier and to enhance skin hydration for the primary prevention of eczema and food allergy.

How the intervention might work

Emollients, as one intervention, are the mainstay of treatment for those with already established eczema, as detailed in a Cochrane Review (Van Zuuren 2017), because dry skin (xerosis) is a key feature of eczema, and topical moisturisers have an integral role in the standard treatment of eczema of all severities (Eichenfield 2014). Emollients can decrease water loss across the skin (TEWL), increase stratum corneum hydration, improve comfort, and reduce itch when used on skin that already has active eczema (Lodén 2012; Rawlings 2004), and therefore are a key component in treatment of eczema (Ring 2012). They may be more effective than interventions such as less frequent bathing or use of water softeners for eczema prevention.

All moisturisers contain varying amounts of active ingredients such as humectant or ceramide, as well as excipient ingredients such as emulsifiers (Lodén 2012). Humectants, such as glycerol or urea, aid retention and attraction of water by the stratum corneum. Ceramides are intracellular lipids found in the stratum corneum that are reduced in lesional eczematous skin (Meckfessel 2014). Occlusives such as petrolatum form a layer on the skin surface that may prevent TEWL across the stratum corneum and can soften the skin (Eichenfield 2014; Rawlings 2004). Moisturisers can be hydrophilic or lipophilic. Hydrophilic moisturisers attract water and are important for skin hydration, whereas lipophilic moisturisers tend to stay on the surface to aid the skin barrier (Caussin 2009).

Van Zuuren 2017 showed that regular use of emollients for those with eczema can prolong time to eczema flare, can reduce the number of flares, and can reduce the need for topical corticosteroids. In infants, skin barrier dysfunction is seen before the development of clinical eczema (Danby 2011; Flohr 2010). Therefore, applying moisturisers before eczema is noted may offer a route for primary prevention of eczema. Three published pilot studies suggest that applying moisturisers to infant skin might reduce the prevalence of eczema during the application period (Horimukai 2014; Lowe 2018a; Simpson 2014). These pilot studies were small‐scale studies testing the feasibility of the intervention or looking for signals of a preventative effect, or both. They were insufficiently powered for confirming a preventative effect. It is not known whether applying moisturisers could lead to a programming effect on the skin, causing longer‐term effects on skin physiology, immunology, or clinical manifestations of eczema.

The strong association between eczema and food allergy would suggest that reduced clinical manifestations of eczema could potentially reduce the risk of food allergy, even if it were just to delay the onset of eczema from early infancy, where the association with development of food allergy is strongest (Martin 2015). In a small pilot study of a ceramide‐dominant emollient with an action described as a lipid replacement, evidence suggests reduced allergic sensitisation to foods in the per‐protocol analysis of the intervention group (Lowe 2018a).

Mechanistic studies within the clinical trials suggest that emollients can increase stratum corneum hydration when used in healthy infants, but trials have not consistently identified changes in skin pH or TEWL (Yonezawa 2018). It is unclear whether this increase in stratum corneum hydration will lead to reduced skin inflammation and associated allergic sensitisation.

Why it is important to do this review

Preliminary data suggest that variations in infant skin care protection interventions, such as application of emollients, might influence the risk of eczema or food sensitisation, at least during the intervention period (Horimukai 2014; Lowe 2018a; Simpson 2014). This raises the possibility of a relatively simple, cheap, and safe intervention for primary prevention of two common and burdensome conditions. This review is important and timely because larger clinical trials are now formally testing the hypothesis that variations in infant skin care can influence the risk of eczema or food allergy (Chalmers 2020; Skjerven 2020).

At the time this systematic review was initiated, two major ongoing interventional trials were assessing whether skin care interventions in the first year of life will reduce the prevalence of eczema or food allergy; these have both been published. The National Institute for Health Research‐Health Technology Assessment (NIHR‐HTA)‐funded Barrier Enhancement for Eczema Prevention (BEEP) study was designed to assess whether daily application of emollients for the first year of life would reduce the prevalence of eczema or allergic disease in the first five years of life (Chalmers 2017; Chalmers 2020; ISRCTN 21528841). Preventing Atopic Dermatitis and Allergies in Children ‐ the PreventADALL study ‐ is a large, prospective, mother‐child birth cohort study incorporating a randomised controlled 2 x 2 factorial‐designed intervention strategy (skin care and early complementary food introduction) to prevent eczema and food allergy (Lødrup 2018; NCT02449850; Skjerven 2020). This study will report food allergy outcomes after all assessments at age three years have been completed.

The BEEP study was powered to detect a difference in eczema during the second year. However, statistical power within this sample size was limited for other outcomes such as food allergy, and for subgroup analyses. For example, BEEP had 80% power at two‐sided alpha of 0.05 for detecting a 50% reduction in food allergy. BEEP was a pragmatic study, which could further limit statistical power if compliance with recommended skin care advice in that setting was low.

PreventADALL was powered to detect a difference in eczema during the second year. PreventADALL also had limited statistical power for other outcomes such as food allergy, and for subgroup analyses. Several other smaller studies of primary prevention of eczema or food allergy were ongoing at the time this systematic review was initiated ‐ in Australia (ACTRN12613000472774), Germany (NCT03376243), Japan,(JPRN‐UMIN000004544; JPRN‐UMIN000010838; JPRN‐UMIN000013260), and the USA (NCT01375205). Many have now published and are included in this review (Dissanayake 2019; Lowe 2018a; McClanahan 2019; Yonezawa 2018).

This systematic review aimed to determine whether infant skin care interventions influence eczema or food allergy prevalence. We undertook an individual participant data (IPD) meta‐analysis. This type of meta‐analysis is considered the gold standard for systematic reviews. Database and analysis errors in individual trials can be identified and potentially corrected. IPD meta‐analysis also allows (i) fitting of a consistent analysis model to all trial data sets for each outcome to ensure that we are comparing treatment effects that are adjusted for the same covariates across trials; (ii) obtaining more reliable and powerful subgroup analyses; and (iii) better evaluating the relationship between compliance with the intervention and outcomes of interest (Stewart 2002). This systematic review also incorporated a prospectively planned component whereby two of the main studies aligned outcomes and details of the meta‐analysis were planned before the results of each trial were known. Prospectively Planned Meta‐Analysis (PPMA) aims to reduce bias related to knowledge of existing trial outcomes. Sharing clinical trial data is encouraged as best practice in clinical trials, and sharing of individual participant data maximises knowledge gained through the efforts of trial participants (Taichman 2017).

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess effects of skin care interventions, such as emollients, for primary prevention of eczema and food allergy in infants.

Secondary objective

To identify features of study populations such as age, hereditary risk and adherence to interventions that are associated with the greatest treatment benefit or harm for both eczema and food allergy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Parallel‐group or factorial randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including both individual and cluster‐randomised trials. Quasi‐RCTs and controlled clinical trials were excluded. Cross‐over trials were also excluded, as the design is inappropriate to the clinical context.

Types of participants

Infants (age 12 months or younger). As this is a primary prevention review, we did not include studies on infants who already had diagnosed eczema or food allergy at the time of randomisation. We excluded study populations defined by a pre‐existing health state in the infant, such as preterm birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation) or congenital skin conditions, because findings in these populations may not be generalisable.

We attempted to obtain individual participant data for all included studies. If individual participant data were not available, we obtained aggregate data instead. For studies with only aggregate data available, we excluded the whole study if some participants were not eligible, unless ineligible participants made up an insignificant proportion of the total group, that is, less than 5%. In trials with individual participant data, we planned to include only the data on participants who meet our eligibility criteria; however no exclusions were necessary, as all obtained individual participant data were eligible.

Types of interventions

All skin care interventions that could potentially enhance skin barrier function, reduce dryness, or reduce subclinical inflammation. These include:

moisturisers/emollients;

bathing products (these may include oils or emollients);

advice regarding reducing soap exposure and bathing frequency; and

use of water softeners.

Interventions could be simple single interventions; others could be complex interventions that utilise a combination of measures to protect or promote skin barrier function and hydration or to reduce subclinical inflammation. The comparators were no treatment intervention or advice, or standard care, in the study setting. We excluded multi‐faceted interventions, whereby the skin care component was only a small part of the study if the skin care component was likely trivial or irrelevant to the outcome. We also planned to assess separately those interventions that primarily aim to enhance the skin barrier through direct application of emollient or moisturiser (skin care intervention A) and those that aim to protect the skin barrier from irritation, that is, through use of water softeners (skin care intervention B). However, we did not find any eligible studies for type B.

Types of outcome measures

No minimum follow‐up was required. However, we separately analysed outcomes that related to symptoms during the intervention period and outcomes that occurred and were reported after the intervention period, when appropriate and feasible.

Primary outcomes

Eczema. When multiple measures were reported, the hierarchy of diagnosis was investigator assessment as described by the Hanifin and Rajka criteria in their original form (Hanifin 1980), or by the UK Working Party refinement of them (Williams 1994), other modifications of the Hanifin and Rajka criteria, doctor diagnosis of eczema, then patient or parent report of eczema

Food allergy. When multiple measures of food allergy were reported, the hierarchy of diagnosis was confirmed IgE‐mediated food allergy diagnosed via oral food challenge, with eligibility for oral food challenge decided as per study protocol, although ideally based on current recommendations (Grabenhenrich 2017). If oral food challenge was not available, then food allergy was as diagnosed by investigator assessment using a combination of clinical history and allergy testing: skin prick testing and serum‐specific IgE. We defined IgE sensitisation as skin test to a food of 3 mm or more, or specific IgE of 0.35 kUa/L or higher. The primary foods of interest were milk, egg, and peanut; however we collected data on any foods that were available from each study

The time point for all food allergy and eczema outcome analyses was by age one to three years using the closest available time point to two years, from each included trial. Adverse event outcomes were measured during the intervention period only. When pooling data from different trials, we considered the relationship between timing of the intervention and timing of the outcome measure, for example, we pooled separately measures of eczema taken during the intervention period and measures of eczema taken after the intervention period has ceased.

As we identified multiple measures of eczema across trials, we conducted sensitivity analysis to look separately at eczema measured using the Hanifin and Rajka criteria in their original form (Hanifin 1980), or the UK Working Party refinement of them (Williams 1994), and other modifications of the Hanifin and Rajka criteria only. We had planned to separately look at food allergy measured using secure diagnosis of food allergy by oral food challenge in a sensitivity analysis, if necessary.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events, including skin infection during the intervention period; stinging or allergic reactions to moisturisers; or slippage accidents around the time of bathing or application of emollient. We will report all serious adverse events

Eczema severity: clinician‐assessed using EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) or a similarly validated method (Hanifin 2001)

Parent‐reported eczema severity using POEM (Patient Orientated Eczema Measure) or a similarly validated patient‐reported measure (Charman 2004)

Time to onset of eczema

Parent report of immediate (less than two hours) reaction to a known food allergen: milk, soya, wheat, fish, seafood, peanut, tree nut, egg, or local common food allergen

Allergic sensitisation to foods and inhalants via skin prick test (or, if not available, via serum‐specific IgE)

When available, from each trial, we analysed any relevant core outcomes identified as part of the Cochrane Skin COUSIN and HOME initiatives (www.homeforeczema.org). Relevant HOME domains include clinician signs measured using the EASI instrument, patient‐reported symptoms using the POEM instrument, long‐term disease control, and quality of life. These outcomes were designed for trials involving those with established eczema. There is not yet a set of core outcomes for defining eczema or food allergy in prevention studies; however, for eczema, a modified version of the UK Hanifin and Rajka criteria has been proposed to differentiate between an incident diagnosis of eczema and transient eczematous rashes of infancy (Simpson 2012). When feasible, we contacted trial authors early in the design or set‐up of their trial to encourage sharing of outcome assessment methods, instruments used, and timing. We did not include long‐term disease control or quality of life outcomes in this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist searched the following databases up to 14 July 2020, using strategies based on the draft strategy for MEDLINE in our published protocol (Kelleher 2020).

Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, using the search strategy in Appendix 1.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 7), in the Cochrane Library, using the strategy in Appendix 2.

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946 onwards), using the strategy in Appendix 3.

Embase via Ovid (from 1974 onwards), using the strategy in Appendix 4.

Trials registers

We (MK, SC, and LT) searched the following trials registers on 25 October 2019, and to update, again on 23 July 2020.

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), using the draft search strategy in Appendix 5.

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/), using the draft strategy in Appendix 6.

Searching other resources

Conference proceedings: we reviewed the proceedings of Asia Pacific Association of Pediatric Allergy, Respirology & Immunology Conferences (APAPARI) for 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Searching reference lists: we checked the bibliographies of included trials and identified relevant systematic reviews for further references to relevant RCTs.

Adverse effects: we did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used for prevention of eczema and food allergy. We considered only adverse effects described in included trials.

Data collection and analysis

This systematic review was undertaken according to the methods recommended by Cochrane, including the updated Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (Stewart 2019), with special attention to Chapter 26, 'Individual Patient Data'. A summary record of prospectively planned components of the meta‐analysis was registered on PROSPERO (reference 42017056965; registered 10 February 2017) (Boyle 2017).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (from MK, SC, and LT) independently carried out title, abstract, and full‐text screening, with arbitration by a third review author (RJB) when necessary. In this systematic review, we combined both retrospective and prospectively acquired data in the meta‐analysis. Retrospective data are outcome data acquired, analysed, unblinded, and known to the trial Chief Investigator before registration of the systematic review protocol (PROSPERO reference 42017056965; registered 10 February 2017; Boyle 2017). Prospectively acquired data are those data known to the trial Chief Investigator, in analysed and unblinded form, before 10 February 2017. This systematic review used participant‐level data from all trials when possible. We invited the authors of each included trial to collaborate in accordance with Section 26.2 of the updated Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Stewart 2019). We asked all trial authors to provide individual participant data. One review author (from LT and MK) sent a data request email to the first and corresponding authors of the associated trial listing the variables required for the analysis (Appendix 7). Following completion of a data sharing agreement, selected variables, or full data sets when appropriate permissions were obtained, were exchanged between researchers along with a data dictionary. If study authors were unable to provide participant‐level data, we accepted appropriate summary data.

Data extraction and management

We conducted data collection and handling in accordance with guidance provided in Chapter 26.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Stewart 2019). For each of the included trials, descriptive data on trial setting, methods, participants, interventions, comparator, length of follow‐up, instruments used for measuring outcomes, funding source, and conflicts of interest were extracted. Two review authors (MK, SC, or LT) independently extracted data using a standardised data collection form, discussing disagreements to reach resolution. When unsuccessful, a third review author (RJB) was consulted. We requested that trial authors who agreed to provide information or data beyond those available in the public sphere share protocol and statistical analysis plan details, along with details of available data fields.

All IPD data used in the systematic review were de‐identified. The list of variables that we requested from each trial is provided in Appendix 7. We transferred specific data fields and then cleaned and coded data for analysis for those trials willing to provide individual participant data. Data sources from previously published trials were provided as anonymised whole databases when trial authors preferred. We carried out range and consistency checks for all data. Any missing data, obvious errors, inconsistencies between variables, or extreme values were queried and rectified with individual trial authors as necessary. We also cross‐checked summaries of provided data with those in published reports of the trial and contacted original trial authors to resolve identified inconsistencies. A secure record was kept of all correspondence, agreements and data transfers with trial authors, and the systematic review database.

For included trials that were unable to provide individual participant data, we recorded the reason for data unavailability and requested aggregate data on our outcomes. If aggregate data could not be obtained directly from the trial authors, two review authors assessed whether any relevant appropriate aggregate‐level data were available in the trial publication or other sources (e.g. clinical trials registry). We recorded aggregate data on a standardised data extraction form. Two review authors (MK, SC) independently extracted data. Any disagreements on extracted aggregate data were discussed and resolved by consensus, and it did not prove necessary for a third review author to arbitrate over data extraction.

The detailed statistical analysis plan for this review was written when data to be collected for the trials providing IPD were known, but before any grouped outcome data from prospective trials had been evaluated (Cro 2020a). The statistical analysis plan was therefore written with consideration of the nature and limitations of the data recorded in trials known to be eligible for inclusion, and the statistician remained blind to intervention and control group outcomes for each data field, so that bias was not introduced by exploring the possible impact of different data analyses and coding decisions on findings.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' 2 tool (Higgins 2018; Higgins 2020b). This tool is designed specifically for RCTs and assesses bias from five domains.

Bias arising from the randomisation process.

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions.

Bias due to missing outcome data.

Bias in measurement of the outcome.

Bias in selection of the reported result.

We assessed the risk of bias separately for eczema (by age one to three years using the closest time point to two years), food allergy (by age one to three years using the closest time point to two years), slippage accidents (during the intervention period), skin infection (during the intervention period), allergic reactions (during the intervention period), time to onset of eczema, parent report of food allergy reaction (at age one to three years using the closest time point to two years), and allergic sensitisation (at age one to three years using the closest time point to two years). The RoB 2 tool is outcome‐specific, and we rated each domain as 'low risk of bias', 'some concerns' or 'high risk of bias'. For bias due to deviations from intended interventions, we were interested in effects of assignment to the interventions at baseline, regardless of whether interventions were received as intended, by an intention‐to‐treat analysis that included all randomised participants. Bias in selection of the reported result was low risk for all prospectively identified studies, as we obtained the full data set for these trials. Risk of bias assessments were not performed for qualitative narrative information.

At the time of writing of this review, the RoB 2 tool for cluster RCTs was under development. For cluster‐RCTs, we therefore similarly assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool 2 (Higgins 2018) as outlined above but including an additional domain specific for cluster‐RCTs from the archived version of the RoB 2 tool for cluster‐RCTs (Eldridge 2016) ‐ 'Domain 1b ‐ Bias arising from the timing and identification and recruitment of participants'.

To reach an overall 'risk of bias' judgement for a specific outcome, we used the following criteria.

Overall low risk of bias: all domains considered at low risk for the specific result.

Some concerns: some concerns have been raised in at least one domain for the specific result, but no domains are considered at high risk of bias.

High risk of bias: at least one domain is considered at high risk for the specific result, or there are some concerns for multiple domains, which substantially lowers confidence in the result.

Two review authors (MK and SC) independently conducted 'Risk of bias' assessments with any disagreements resolved via discussion or through arbitration with a third review author (RJB). For a trial for which MK and RJB were investigators (Chalmers 2020), SC and VC independently conducted risk of bias assessments.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes when meta‐analysis was considered appropriate, we calculated risk ratios (RRs). For continuous outcomes when trials used the same measurement scale, we calculated mean differences (MDs); when trials used different measurement scales, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs). For time‐to‐event outcomes, we expressed the intervention effect as a hazard ratio (HR). We computed a 95% confidence interval (CI) for each outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

This review included RCTs only. As elaborated on further below (see Data synthesis), we adopted a two‐stage approach for this IPD meta‐analysis. In stage 1, we separately estimated the treatment effect of interest for each included trial. In stage 2, we pooled treatment effects using methods for meta‐analyses of aggregate data.

Factorial RCTs and cluster‐RCTs were included. For factorial randomised trials, if we noted a significant interaction between the two active interventions with respect to our primary outcome, we included only the arms ‘skin care intervention/control’ versus ‘control/control’. Sensitivity analysis explored the impact of including data from all arms of factorial trials when an interaction was present, with adjustment for non‐skin care interventions.

For other trials with more than two treatment arms (excluding factorial trials, which were handled as described above), which could have multiple intervention groups in a particular meta‐analysis, we combined all relevant intervention groups into a single intervention group and all relevant control groups into a single control group.

For all stage 1 analyses for cluster‐RCTs providing individual participant data, we used mixed models that allow analysis at the level of the individual while accounting for clustering in the data. Treatment effects from cluster‐RCTs were therefore appropriately adjusted for correlation within clusters, before inclusion in the stage 2 (pooled) analysis, following recommendations for analysis of cluster‐RCTs (Higgins 2020a).

For cluster‐RCTs providing non‐individual participant data, we planned to extract data from trial reports that had taken into account the clustering in these data, and to then analyse the data using the generic‐inverse variance method in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5; Review Manager 2014). If data were not adjusted for clustering, we planned to attempt to estimate the intervention effect by calculating an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) while following the recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a).

Dealing with missing data

We dealt with missing data according to recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019). To resolve missing information about methodological properties of identified trials, we contacted authors of the included trials. When trial authors were unable to provide the required information, we rated the relevant 'Risk of bias' criterion using Cochrane 'Risk of bias 2' (Higgins 2018). We did not anticipate substantial quantities of missing data for the primary outcomes. For trials providing individual participant data, we naturally handled missing participant data under the assumption of missing‐at‐random within each trial analysis.

For trials that did not provide individual participant data and reported an MD but no standard deviation (SD) or other statistic that could be used to derive the SD, we planned to use imputation (Furlan 2009). Specifically, we planned to impute SDs for each outcome by using the pooled SD across all other trials within the same meta‐analysis by treatment group. This is an appropriate method of analysis if a majority of the trials do not have missing SDs in the meta‐analysis. If a large proportion of trials (e.g. ≥ 20%) were missing data on parameter variability for a particular outcome, imputation would not be appropriate, and we planned to conduct analysis using only trials providing complete data and to discuss the implications of this alongside results. However such imputation did not prove necessary.

In risk of bias assessments, to address the impact of non‐negligible missing data (≥ 5%) on individual trial outcomes, we conducted sensitivity analyses using individual participant data and best case/worst case scenarios, that is, we conducted analysis by imputing a best case scenario of response in both treatment groups, followed by analysis under a worst case scenario of no response in both treatment groups. Results of sensitivity analyses under these scenarios were compared to primary complete case analyses (conducted under the missing‐at‐random assumption) to assess the risk of bias due to missing data.

In meta‐analysis, we included trials with substantial quantities of missing data (e.g. rated as high risk of bias or some concerns due to missing data), but to investigate the robustness of pooled results, we performed sensitivity analysis while excluding trials rated overall at high risk of bias or with some concerns, which included excluding trials rated at high risk of bias or some concerns due to missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined both clinical and statistical heterogeneity and combined data in meta‐analysis only when we judged that evaluation would yield a meaningful summary. We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining characteristics of included participants, types of interventions, primary and secondary outcomes, and the follow‐up period. We used the I² statistic and the Chi2 test to quantify the degree of statistical heterogeneity of trials judged as clinically homogeneous (Higgins 2003). For interpretation, we considered an I² of 0% to 40% might not be important heterogeneity; 30 to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and I² greater than 75% indicative of considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2019). The observed I2 value was judged against this guide in combination with its 95% confidence interval, the P value from the Chi2 test, and the magnitude and direction of effect. When the magnitude and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity based on the P value from the Chi2 confidence intervals for I² revealed heterogeneity, or if we observed considerable heterogeneity, we explored reasons for heterogeneity and when appropriate conducted sensitivity analysis while excluding any trials identified as outlying.

Assessment of reporting biases

By including as many prospective trials as possible in this review, as well as individual participant data, risks of reporting bias and publication bias should be reduced. However, if at least 10 trials were included in the meta‐analysis, we planned to formally assess reporting bias using funnel plots to explore the likelihood of any reporting bias or small‐study effects. We planned to assess funnel plot asymmetry visually and to use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes, we planned to use the test proposed by Egger 1997. For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to use the test proposed by Rucker when estimated between‐study heterogeneity variance of log odds ratios, tau², is greater than 0.1 (Rucker 2008). Otherwise, when the heterogeneity variance tau² was less than 0.1, we planned to use one of the tests proposed in Harbord 2006. If asymmetry was detected in any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to explore and discuss possible explanations. However, we did not conduct a meta‐analysis with 10 or more trials included; therefore we did not undertake any formal assessment of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We conducted an IPD meta‐analysis of both prospective and retrospectively acquired data. Primary meta‐analysis used individual participant data only. Aggregate data were not used in the primary meta‐analysis when individual participant data could not be provided, as the total proportion of participants that made up aggregate data was less than 10% of the overall number of participants across all trials (i.e. total aggregate data represented a negligible proportion of the data set). We performed a sensitivity analysis by adding in the aggregate data, as described further below, to explore the impact of data availability bias. We undertook a prospectively planned meta‐analysis (PPMA) of a more limited number of trials, as a sensitivity analysis. PPMA was limited to those trials in which trial authors were not aware of trial outcomes at the time of PPMA protocol registration on PROSPERO (Boyle 2017).

The main analyses estimated the effect of being assigned to receive the intervention, according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. We retained all eligible participants in the treatment group to which they were originally assigned who had an outcome, irrespective of the treatment they actually received. To understand the effect of compliance, we included pre‐planned secondary supplementary analysis to estimate the complier average causal effect.

We planned to perform all analyses stratified by type of intervention group. Planned comparisons were therefore:

skincare intervention versus no treatment or standard care;

skincare intervention 'A' versus no treatment or standard care; and

skincare intervention 'B' versus no treatment or standard care.

We planned to consider interventions in two broad categories: A interventions promoting hydration and skin barrier mainly through emollients, and B interventions that would protect from harm, such as water softeners or avoidance of irritants. Because our search did not reveal any eligible trials of B‐type skin care interventions, it did not prove necessary to stratify comparisons by type of skin care intervention; therefore, we undertook only comparisons of type A. For each outcome, when we judged a sufficient number of trials (two or more) to be clinically similar, we pooled results in a meta‐analysis. When we did not undertake meta‐analyses owing to clinical heterogeneity or to insufficient data, we narratively discuss the results from individual trials.

We adopted a two‐stage approach to analysis for all primary and secondary analyses. In the first stage, we derived individual trial treatment effect estimates from individual participant data. For analyses of binary outcomes, including both primary outcomes (eczema and food allergy), the stage 1 model, fitted to each trial providing individual participant data separately, was a binomial regression model. For analyses of continuous outcomes, the stage 1 model fitted to each trial providing individual participant data was a linear regression model. For time‐to‐event outcomes, the stage 1 model fitted to each trial providing individual participant data was a binomial regression model with a complementary log‐log link, where follow‐up time was split into appropriate intervals for the obtained data (3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months). This model was appropriate for time‐to‐event data of a discrete nature. In addition to the treatment group variable indicating use of a skin care intervention, we included the important prognostic factors of sex and family history of atopic disease within the stage 1 models.

In the second stage, we combined derived treatment effects using methods for meta‐analyses of aggregate data. We used random‐effects models in stage 2 to derive the pooled treatment effect (DerSimonian 1986). We planned to use random‐effects models because we anticipated some level of variability across trials, for example, by types of interventions, length of follow‐up, and methods of measurement. A random‐effects model incorporates heterogeneity among trials and allows the true treatment effect to be different in each trial. In sensitivity analysis, the second stage also included aggregate data from trials whose authors did not provide individual patient data.

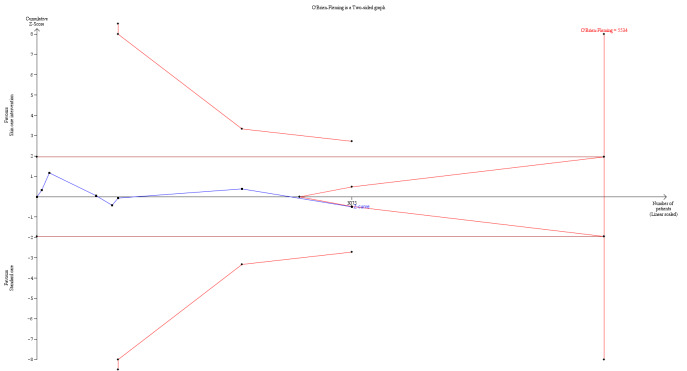

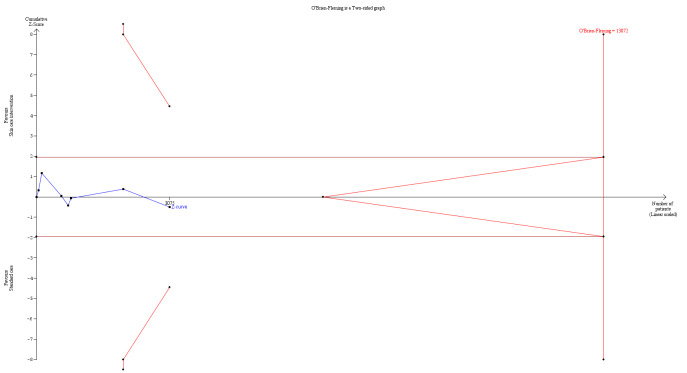

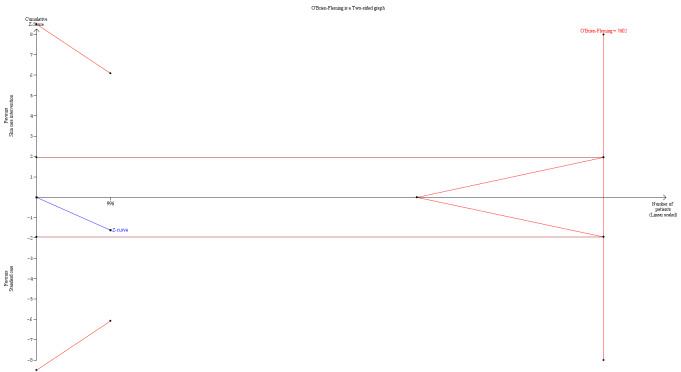

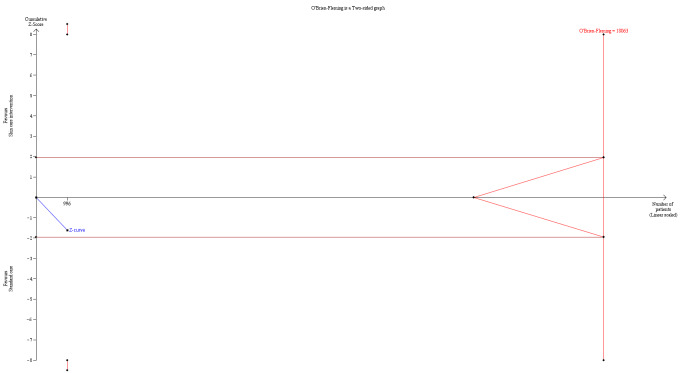

We performed residual analysis for all IPD meta‐analyses and PPMAs to assess model assumptions and fit. Meta‐analyses also included trial sequential analysis, using two‐sided 5% significance and 80% power to estimate optimum heterogeneity‐adjusted information sizes needed to identify relative risk reductions of 20% and 30% (Wetterslev 2008). We estimated control event rates using random‐effects meta‐analyses of pooled proportions from the largest trials included in the meta‐analyses and compared them with event rates from large population‐based studies. Trial sequential analysis was used to identify when the optimum information size or futility boundaries for pre‐defined effect sizes in relation to primary outcomes will be reached. We performed stage 1 of the IPD meta‐analysis in Stata 15 or above (Stata), with summary results of these analyses added into RevMan Web (revman.cochrane.org).