Abstract

Despite the clinically significant impact of executive dysfunction on the outcomes of adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), we lack a clear understanding of its prevalence, profile, and development. To address this gap, we administered the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery to a cross-sectional Intelligence Quotient (IQ) case-matched cohort with ASD (n = 66) and typical development (TD; n = 66) ages 12–22. We used a general linear model framework to examine group differences in task performance and their associations with age. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to identify subgroups of individuals with similar cognitive profiles. Compared to IQ case-matched controls, ASD demonstrated poorer performance on inhibitory control (P < 0.001), cognitive flexibility (P < 0.001), episodic memory (P < 0.02), and processing speed (P < 0.001) (components of Fluid Cognition), but not on vocabulary or word reading (components of Crystallized Cognition). There was a significant positive association between age and Crystallized and Fluid Cognition in both groups. For Fluid (but not Crystallized) Cognition, ASD performed more poorly than TD at all ages. A four-group LPA model based on subtest scores best fit the data. Eighty percent of ASD belonged to two groups that exhibited relatively stronger Crystallized versus Fluid Cognition. Attention deficits were not associated with Toolbox subtest scores, but were lowest in the group with the lowest proportion of autistic participants. Adaptive functioning was poorer in the groups with the greatest proportion of autistic participants. Autistic persons are especially impaired on Fluid Cognition, and this more flexible form of thinking remains poorer in the ASD group through adolescence.

Keywords: executive control, cognitive control, executive functions, adolescents, young adults, NIH Toolbox, latent profile analysis, adults, phenotypes, subtypes of ASD

Lay Summary:

A set of brief tests of cognitive functioning called the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery was administered to adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD; n = 66) and typical development (TD; n = 66) ages 12–22 years. Compared to TD, ASD showed poorer performance in inhibiting responses, acting flexibly, memorizing events, and processing information quickly (Fluid Cognition). Groups did not differ on vocabulary or word reading (Crystallized Cognition). Crystallized and Fluid Cognition increased with age in both groups, but the ASD group showed lower Fluid, but not Crystallized, Cognition than TD at all ages. A categorization analysis including all participants showed that most participants with ASD fell into one of two categories: a group characterized by poor performance across all tasks, or a group characterized by relatively stronger Crystallized compared to Fluid Cognition. Adaptive functioning was poorer for participants in these groups, which consisted of mostly individuals with ASD, while ADHD symptoms were lowest in the group with the greatest proportion of TD participants.

Introduction

Deficits in the ability to hold task rules in mind while simultaneously inhibiting prepotent response tendencies in the service of flexible goal-directed behavior often are found in autistic individuals [Hill, 2004; Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996; Solomon, Hogeveen, Libero, & Nordahl, 2017]. These abilities, which have been called cognitive control processes [Miller & Cohen, 2001] or executive functions (henceforth referred to as executive control), serve as a scaffold for higher level information processing [Maister, Simons, & Plaisted-Grant, 2013; Solomon et al., 2017]. When disrupted, they may result in core symptoms of ASD [Pellicano, 2012] and everyday behaviors that are poorly coordinated and rigid. Thus, a better understanding of executive control (EC)-related aspects of the ASD phenotype may help illuminate the mechanisms underpinning ASD symptoms; enhance understanding of the strengths and challenges of autistic persons; and inform the development of targeted interventions [Charman et al., 2011].

Executive Control in ASD

Studies employing neuropsychological, experimental cognitive neuroscientific, and parent-report measurements find impairments in the three most commonly identified core domains of EC: working memory (cue or context maintenance), response inhibition, and set shifting (task switching or cognitive flexibility) [Miyake et al., 2000].

Working memory/cue or context maintenance.

This construct refers to the ability to maintain task rules or context online to influence responding. Two meta-analyses [Habib, Harris, Pollick, & Melville, 2019; Wang et al., 2017] including children, adolescents, and adults found that both verbal and visuo-spatial working memory/context maintenance are impaired in ASD. However, some studies suggest there are no deficits in younger children [Faja & Dawson, 2014; Griffith, Pennington, Wehner, & Rogers, 1999] and adolescents [Ozonoff & Strayer, 2001; Russell, Jarrold, & Henry, 1996] with average or better levels of intellectual functioning. There also are studies showing spared visual (vs. visuo-spatial) working memory [Hamilton, Mammarella, & Giofre, 2018], which may be scaffolded by autistic persons’ relative strength in visual information processing [Mottron, Dawson, Soulieres, Hubert, & Burack, 2006; Samson, Mottron, Soulieres, & Zeffiro, 2012; Soulieres et al., 2009]. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that deficits may be most evident when context maintenance is required in anticipation of response inhibition [Solomon et al., 2009; Solomon, Ozonoff, Cummings, & Carter, 2008] while the pure preparatory (proactive) component of EC is spared [Hogeveen, Krug, Elliott, Carter, & Solomon, 2018; Krug et al., 2020].

Response inhibition.

This construct refers to the ability to inhibit prepotent, but inappropriate, maladaptive behavioral responses. One early paper suggested that a lack of deficits in response inhibition differentiated persons with ASD from those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996]. However, later findings have been mixed with more recent studies [Corbett, Constantine, Hendren, Rocke, & Ozonoff, 2009] and meta-analyses [Craig et al., 2016] suggesting that ASD also involves deficits in response inhibition, given that both ADHD and ASD may reflect aspects of the same disorder [Rommelse, Geurts, Franke, Buitelaar, & Hartman, 2011; Ronald, Simonoff, Kuntsi, Asherson, & Plomin, 2008]. Arguing against this assertion, however, attention problems may decline during adolescence in those with ASD but not in those with ADHD [Geurts, van den Bergh, & Ruzzano, 2014; Happe, Booth, Charlton, & Hughes, 2006].

Set shifting/cognitive flexibility.

This construct refers to the ability to efficiently switch between different sets of task rules or goals. This is the most often cited EC deficit found in ASD [Ozonoff et al., 2004; Yerys et al., 2009]. The universality of set shifting deficits has been questioned, however [Geurts, Corbett, & Solomon, 2009], and may only be present if certain less effortful experimental tasks or parent-report measures are used [Bertollo et al., 2020; Strang et al., 2017], or if participants must initiate actions [Poljac, Hoofs, Princen, & Poljac, 2017].

Other Cognitive Processes Influencing Executive Control

Other cognitive processes can moderate EC. Processing speed, which is slower in children [Mayes & Calhoun, 2007] and adults [Haigh, Walsh, Mazefsky, Minshew, & Eack, 2018] with ASD, can impair EC. Aspects of language processing including vocabulary and word reading also may improve autistic person’s ability to conceptualize tasks and to follow directions [Norbury, Griffiths, & Nation, 2010]. Episodic memory helps individuals to maintain goals and task rules and is thought to be impaired in ASD [Ben Shalom, 2003; Bowler, Gaigg, & Lind, 2011]. Finally, ADHD symptoms can exacerbate EC problems in autistic persons [Berenguer, Rosello, Colomer, Baixauli, & Miranda, 2018].

Development of Executive Control and Related Cognitive Processes

Despite the considerable maturation of EC during adolescence [Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Luna, 2009], studies of persons with ASD through this period are equivocal. One study of a parent report questionnaire showed a persisting lag [Rosenthal et al., 2013]. Other studies demonstrate isolated development of a subset of component processes [Christ, Kester, Bodner, & Miles, 2011; Geurts et al., 2014; Kouklari, Tsermentseli, & Monks, 2018] or limited improvement within the context of persistent delay [Luna, Doll, Hegedus, Minshew, & Sweeney, 2007]. The magnitude of the improvement between childhood and young adulthood also may be less pronounced for individuals with ASD, which produces growing group discrepancies by later adolescence [Kouklari et al., 2018; Schmitt, White, Cook, Sweeney, & Mosconi, 2018; Solomon et al., 2015; Solomon, McCauley, Iosif, Carter, & Ragland, 2016].

Are There Subgroups with Different Patterns of Executive Control Deficits?

Cognitive functioning in ASD has been described as “fractionated,” meaning that the domains of social communication and repetitive behaviors cannot be described by a single genetic, neural, or cognitive cause [Brunsdon & Happe, 2014]. Indeed, not all individuals with ASD exhibit EC deficits. Those who do may show distinct profiles. For example, 8% of children with ASD exhibit no EC impairments and their deficit profiles may differ [Brunsdon et al., 2015].

To help clarify the profile and development of EC and related cognitive processes in adolescents and young adults with ASD, we administered the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB or “Toolbox”) in a relatively large Intelligence Quotient (IQ) case-matched sample of adolescents and young adults with ASD and typical development (TD) ages 12–22 years. The NIH Toolbox for Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function provides brief, efficient, and accessible tests to measure cognitive and other domains of health across the lifespan [Akshoomoff et al., 2014]. We compared ASD and TD groups on scores across the seven subtests assessing core elements of EC and its implementation, age differences in performance, and profiles of subtest performance. We hypothesized that, compared to TD controls, individuals with ASD would show greater deficits in response inhibition [Geurts et al., 2014], cognitive flexibility [Ozonoff et al., 2004; Yerys et al., 2009], working memory [Kouklari et al., 2018], episodic memory [Ben Shalom, 2003], and processing speed than in vocabulary or word reading [Mayes & Calhoun, 2007]; that ADHD symptoms would be associated with EC deficits [Berenguer et al., 2018]; and that the ASD group would show continued poorer EC performance than TD through adolescence [Luna et al., 2007]. We predicted there would be several EC profiles, but made no firm hypotheses about their composition or characteristics given the paucity of literature on this topic.

Method

Participants

Eighty-eight participants with ASD (mean age = 17.0 SD = 3.1) and 88 participants with TD (mean age = 16.9 SD = 3.2) ages 12–22 were enrolled in the cohort-sequential Cognitive Control in Autism study (CoCoA; R01 MH106518) at the University of California (UC), Davis MIND Institute, which investigates cognitive development and outcomes during the transition to young adulthood. 18.2% of the ASD and 20.5% of the TD groups were female. Participants were recruited from the greater Sacramento area using advertisements, physician referrals, and the MIND Institute’s research volunteer registry and subject tracking system. Data presented here are from the first wave of this study.

To qualify for the CoCoA study, autistic participants needed to have an existing community diagnosis of ASD, to meet diagnostic criteria for ASD on a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) Checklist, to be at or above the cutoff for an ASD on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS-2) [Lord et al., 2000], and to have a Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) total score greater than or equal to 15 [Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003]. Participants in the TD group had total scores less than or equal to 11 on the SCQ, exhibited no social communication disorders as assessed by a DSM-5 symptom checklist, and had no first-degree relatives with a history of ASD. Finally, both groups were required to have a Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition (WASI-II) [Wechsler, 1999, 2011] Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) ≥ 70, no reported neurodevelopmental disorders (although they were not systematically screened for any) other than ASD or ADHD, no history of seizures, and no current psychotropic medication use of agents other than psychostimulants, given that the larger study included task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging. Parents reported that 24% of participants with ASD and 0% with TD had clinically significant ADHD symptoms as assessed by the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) DSM-oriented scales for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems [Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001, 2003]. The CoCoA study protocol was approved by the UC Davis Institutional Review Board.

IQ is a moderator of the association between EC and other variables [Liss et al., 2001]. However, statistical covariation has been found to induce distortions and confounds in analyses [Miller & Chapman, 2001] and to be suboptimal for comparing groups with different distributions of the covariate [Thomas et al., 2009]. Given that individuals with ASD and above average cognitive ability levels exhibit a wide variety of IQ profiles including those with discrepancies favoring verbal abilities or nonverbal abilities, and those with no such discrepancies [Ehlers et al., 1997], we matched participants on FSIQ. Three participants (two ASD, one TD) were excluded due to a technical problem with scale computation. The remaining 173 participants were used in an automated greedy matching algorithm (http://bioinformaticstools.mayo.edu/research/gmatch/) to identify a 1:1 matched sample. The algorithm allowed us to set a maximum deviation on IQ (seven points) when selecting a match. The final sample used in this manuscript included 66 ASD-TD matched pairs. They were similar in age [ASD =17.5 years (SD = 36.2); TD = 17.5 years (SD = 39.3)] and FSIQ [ASD = 106.2 (11.4); TD = 106.9 (10.9)]. The ASD group had 11 female (16.7%) participants and the TD group had 15 female (22.7%) participants. The mean ADHD score for ASD was 59.2 (SD = 7.7) and 51.8 (SD = 3.1) for TD. See Table 1 for more complete participant characteristics for the case matched sample.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| ASD (n = 66) | TD (n = 66) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSIQ, mean (SD) | 106.2 (11.4) | 106.9 (10.9) | 0.74 |

| VCI, mean (SD) | 100.4 (13.4) | 103.7 (11.9) | 0.13 |

| PRI, mean (SD) | 111.3 (13.6) | 108.4 (12.9) | 0.21 |

| ADOS (SA), mean (SD) | 7.8 (1.4) | - | - |

| ADOS (RRB), mean (SD) | 6.9 (2.1) | - | - |

| ADOS (CSS), mean (SD) | 7.7 (1.6) | - | - |

| ASEBA DSM-ADHD | 59.2 (7.7) | 51.8 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 17.5 (36.2) | 17.5 (39.3) | 0.91 |

| Female, n (%) | 11 (16.7) | 15 (22.7) | 0.38 |

ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADOS: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ASEBA: Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment; CSS: calibrated severity score; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; FSIQ: Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; PRI: Perceptual Reasoning Index; RRB: Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors scale score; SA: Social Affect scale score; TD: typical development; VCI: Verbal Comprehension Index.

From two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square test for gender.

Measures

In addition to testing with the Toolbox, participants completed common ASD diagnostic measures including the ADOS-2 [Lord et al., 2012], where the calibrated severity score (CSS) was used, and the SCQ [Rutter et al., 2003], as well as the WASI-II [Wechsler, 1999, 2011]. Their parents completed the Adult Behavior Checklist or the ASEBA Child Behavior Checklist, components of ASEBA [Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001, 2003]. The DSM-oriented scale for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems was used. Parents also completed the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System 3 (ABAS-3) [Harrison & Oakland, 2003], and the composite score (GAC) was used. These measures are described in Appendix S1.

NIHTB-CB [Akshoomoff et al., 2014] is a computerized set of seven short tests administered on an iPad. NIHTB-CB also produces indices of Fluid (quick flexible) and Crystallized (accumulated knowledge and skills) Cognition. Fluid Cognition is assessed using Dimensional Change Card Sort, Flanker, Picture Sequence Memory, Pattern Comparison Processing Speed, and List Sorting Working Memory tasks. Crystallized Cognition is assessed with Picture Vocabulary and Oral Reading tests. For all but the developmental analyses, age-adjusted standard scores were used. Brief descriptions of subtests follow with more extensive ones at https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/nih-toolbox/intro-to-nih-toolbox/cognition. A schematic diagram illustrating the core elements of EC and their moderators as assessed in the Toolbox, and their potential association with everyday behavior can be found in Figure S1.

Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) Test.

DCCS measures cognitive flexibility or set shifting and was adapted from Zelazo [2006]. Participants are shown pictorial stimuli on the iPad and instructed to match the central stimuli with one of two target stimuli on the basis of shape or color.

Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test.

This task is derived from the Eriksen flanker task [Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974] and tests the ability to inhibit visual attention to irrelevant task features.

Picture Sequence Memory Test (PSMT).

Thematically related images from a series of scenes are presented one at a time and then moved into a fixed spatial order. Once all the images have been presented in their correct positions, the images return to the center of the screen with their order randomized and the participant must remember the original order.

Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test (PCPS).

This task requires participants to identify whether two images are the same or different with scoring based on the number of correct trials completed in 90 seconds.

List Sorting Working Memory Test (LSWM).

Participants size order a series of images presented visually and orally. After each, participants must repeat the stimuli to the examiner in size order, from smallest to largest. There are one- and two-list conditions.

Picture Vocabulary (PV) Test.

This is a test of receptive vocabulary. Single words are presented and consist of multiple trials in which a single word is presented via audio file paired simultaneously with four images on the screen. The test uses computer adaptive testing to determine the optimal difficulty level for 25 test items.

Oral Reading Recognition Test (ORT).

In this task, words or letters are presented one at a time and participants must pronounce them. The ORT uses adaptive difficulty scaling.

Statistical Analysis

Since hypotheses focused on comparing ASD and TD across subtests, two-sample t-tests for age-adjusted standard scores on the seven NIHTB-CB subtests were used to determine whether autistic individuals differed from TD. A follow-up 2 (Diagnosis: ASD vs. TD) × 2 (Cognition: Crystalized vs. Fluid) factorial analyses of variance (ANOVA) examined relative differences in the two composite indices between the groups. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Bonferroni procedure [Holm, 1979]. To examine whether ADHD symptoms (T-scores from the DSM-oriented scales for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems of the ASEBA) and adaptive functioning (Composite of the ABAS-3) were associated with subtest and index scores. Spearman correlations were used, given the non-normality of the data.

A linear regression with age-unadjusted scores was used to investigate the association between age and Fluid and Crystalized Cognition and whether these associations differed by group. Separate models were fit for Fluid and Crystalized cognition. Age was centered at the minimum in the sample, so the intercept can be interpreted as the average level in the reference group (TD) at baseline. Each model included a term for group (to test for differences between ASD and TD at age 12), age, and the interaction between age and group (to test for differences in slopes between ASD and TD).

Given the power constraints of our sample and our goal of investigating how ASD were similar to and different from TD, latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to identify groups of individuals who had similar profiles across the seven NIHTB-CB subtests for the entire sample. Two-, three-, four-, and five-class LPA models were run and compared using both statistical goodness-of-fit criteria and interpretability of the classes. We selected the optimal number of groups using the most parsimonious model that still provided good relative fit using a combination of statistical goodness-of-fit criteria, which included an adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), entropy, and Lo—Mendell—Rubin (LMR) [Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001] and Parametric Bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (PBLRT) [Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthen, 2008]. Smaller values of AIC and BIC indicate better fit and entropy values closer to one and indicate better classification quality of individuals by each model. The likelihood ratio tests compare the fit of the specified class solution to models with one less class and a significant P-value indicates the specified model should be preferred. The local maximum problem was addressed by using multiple starting points (up to 500) to replicate each model. The highest posterior probability from the best fitting models was used to assign each participant to the most likely subgroup. We subsequently compared these groups on verbal IQ (VIQ), nonverbal IQ (PRI), FSIQ, and age using one-way ANOVA. Given their non-normality, ADHD and ASD symptoms and adaptive functioning were examined using Kruskal-Wallis H tests. All tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Bonferroni method [Holm, 1979]. LPA was performed in Mplus version 8 [Muthen & Muthen, 2017]. All other analyses were implemented using R (version 3.6.1, R Core Team, 2017 – https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

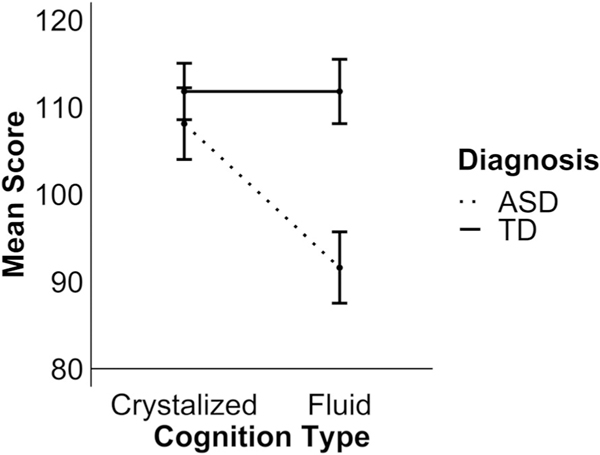

Summary statistics for both groups are provided in Table 2. Independent samples t-tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction highlighted that TD participants scored significantly higher than ASD participants on DCCS [t(130) = 5.95, P < 0.001], PCPS [t(130) = 5.87, P < 0.001], Flanker [t(130) = 5.66, P < 0.001], and PSM [t(130) = 2.97, P = 0.02] subtests of the NIHTB-CB. Scores were similar for the two groups on LSWM [t(130) = 0.09, P = 1.00], ORT [t(130) = 2.01, P = 0.19], and PV [tz (130) = 0.49, P = 1.00]. In order to clarify whether this pattern of differences represented a specific impairment in more flexible Fluid Cognition in ASD, a further 2 (Group: ASD vs. TD) × 2 (Cognition: Crystalized vs. Fluid) factorial ANOVA was conducted on the Fluid and Crystalized cognition indices. This analysis revealed a significant interaction between the two factors [F(1,130) = 26.29, P < 0.001] (see Fig. 1). Follow-up pairwise comparisons revealed that scores on the Fluid and Crystalized indices were similar in the TD group [t (65) < 0.001, P = 1.00], but scores on the Crystalized index were significantly higher than on the Fluid index for the ASD group [t(65) = 6.98, P < 0.001]. Moreover, while scores on the Crystalized index were similar for the groups [t(130) = 1.38, P = 0.17], TD participants performed significantly better than ASD on the Fluid index [t(130) = 7.20, P < 0.001]. Spearman’s correlations revealed no significant associations between T-scores on the DSM-oriented scales for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems ADHD scores on any of the subtests or indices (all P’s > 0.20) for either group.

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations) of Scores on the Seven Subtests, and Two Composite Indices of the Cognitive Function Battery Tests of the NIH Toolbox

| Cognition domain | Measure | ASD (n = 66) | TD (n = 66) | Δa | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flanker | 92.9 (16.6) | 108.3 (14.4) | 0.99 | <0.001 | |

| DCCS | 90.1 (20.2) | 109.0 (16.2) | 1.04 | <0.001 | |

| PCPS | 89.9 (23.3) | 112.65 (21.1) | 1.02 | <0.001 | |

| PSM | 98.7 (16.5) | 106.9 (15.5) | 0.52 | 0.02 | |

| Fluid | LSWM | 101.7 (14.9) | 101.9 (12.1) | 0.02 | 1.00 |

| PV | 109.00 (17.7) | 110.4 (13.9) | 0.09 | 1.00 | |

| Crystalized | ORT | 105.3 (16.4) | 110.6 (13.9) | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| Fluid Composite Index | 91.6 (16.9) | 111.8 (15.3) | |||

| Crystalized Composite Index | 108.1 (17.1) | 111.8 (13.4) | <0.001 (interaction) |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; DCCS: Dimensional Card Change Sort; LSWM: List-Sorting Working Memory; ORT: Oral Reading Test; PCPS: Pattern Comparison Processing Speed; PSM: Picture Sequence Memory; PV: Picture Vocabulary; TD = typical development.

Δ calculated as the difference in means divided by the common SD.

From two-sample t-tests. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Holm-Bonferroni correction.

Figure 1.

Scores on fluid and crystalized composite indices split by diagnosis group. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. ASD: autism spectrum disorder; TD: typical development.

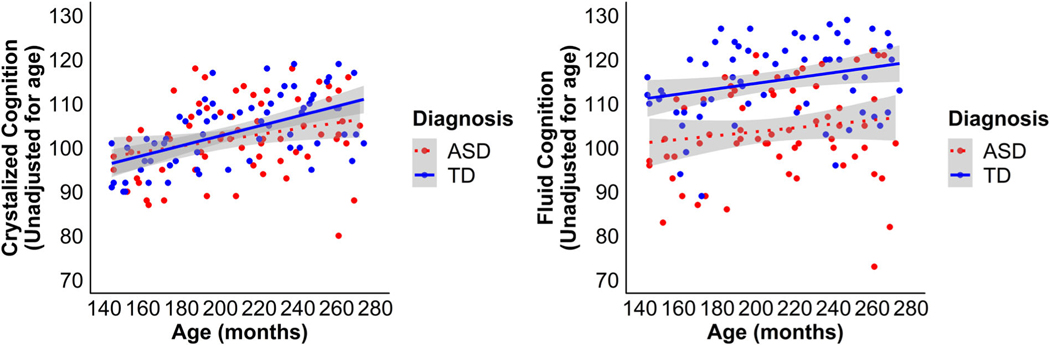

When examining age-unadjusted scores, the associations between Crystalized Cognition and age were not significantly different between the groups [t(1) = 1.31, P = 0.19], (see Fig. 2A). The relationship between age and Crystalized Cognition score was significant [t(1) = 4.67, P < 0.0001] and demonstrated that as age increased there was a concurrent increase in capacity for Crystalized Cognition across both groups. However, the intercepts for the Crystalized Cognition index were not significantly different between the groups [t(1) = 0.59, P = 0.56], suggesting that the groups performed equivalently at the lowest age. Similarly, the association between Fluid Cognition with age was not significantly different between the groups [t(1) = 0.47, P = 0.64], suggesting that, as with Crystalized Cognition, the relationship between age and capacity for Fluid Cognition did not differ between ASD and TD (see Fig. 2B). The association between age and Fluid Cognition score was also significant [t(1) = 2.11, P = 0.04], demonstrating that as age increased there was a concurrent increase in capacity for Fluid Cognition. In contrast to Crystalized cognition, the intercepts for the Fluid cognition were significantly different between the groups [t(1) = 2.90, P = 0.004], suggesting that the ASD group exhibited lower Fluid Cognition at the lowest age and also suggesting that while the rate of change over time was similar in both groups, the ASD group’s lower performance was present at all ages.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between Crystallized (A) and Fluid (B) Cognition and age in months for both diagnostic groups. ASD: autism spectrum disorder; TD: typical development.

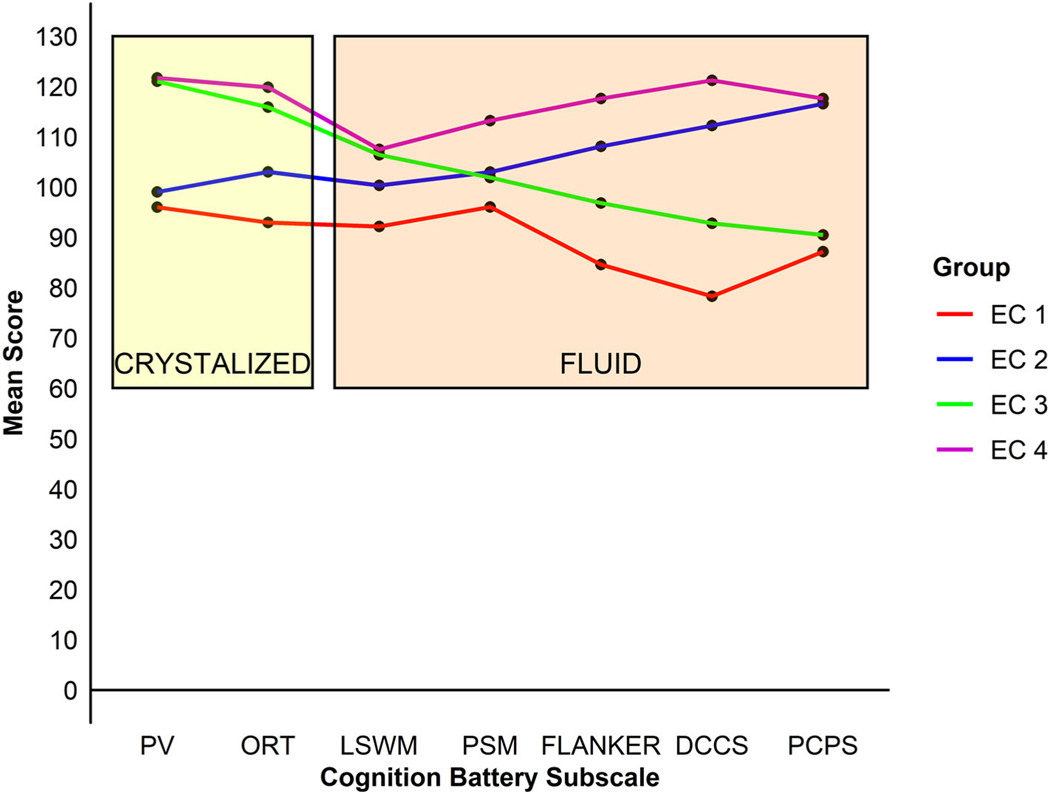

Fit indices for two-class to five-class LPA models are summarized in Table S1. AIC and aBIC indices never increased with added classes, while BIC indices were similar for the two-, three-, and four-class models. PBLRT continued to decrease in models up to four classes, while LMR likelihood ratio test suggested that a two-class solution was optimal. Four-class and five-class models provided similar classification quality (entropy 0.79 and 0.80, respectively). In five-class models, one of the classes comprised only 5% of the sample. Thus, the four-class solution was chosen as optimal because it was the most parsimonious model that still provided adequate fit. Figure 3 depicts these four EC profiles. We used the highest posterior probability from the best fitting models to assign participants to the four EC profiles. Table 3 provides descriptive measures for these four EC groups, including scores broken down by diagnostic group (included for illustrative purposes given their small sizes).

Figure 3.

Profiles of the four executive control groups across subtests of the Cognitive Function Battery tests of the NIH Toolbox.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Four Executive Control (EC) Groups

| ASD, n (%) | EC1 (n = 30) 24 (80) Mean (SD) | EC2 (n = 35) 10 (29) Mean (SD) | EC3 (n = 44) 29 (66) Mean (SD) | EC4 (n = 23) 3 (13) Mean (SD) | P-valuea <0.001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSIQ | 98.9 (11.1)A | 101.8 (8.6)A | 111.2 (8.5)B | 114.9 (9.3)B | 0.001 |

| VCI | 93.5 (12.3)A,B | 100.1 (11.3)B,C | 105.7 (11.5)C,D | 109.1 (11.1)D | 0.001 |

| PRI | 105.0 (14.7)A | 103.2 (11.2)A | 114.4 (11.2)B | 117.6 (11.1)B | 0.001 |

| AGE (months) | 220.4 (39.4) | 200.9 (40.9) | 209.4 (33.8) | 211.2 (35.8) | 0.22 |

| FLUID Cognition | 80.6 (12.4)A | 112.2 (10.6)B | 95.5 (11.7)C | 125.1 (8.4)D | 0.001 |

| ASD: 78.8 (12.6) | ASD: 109.2 (11.4) | ASD: 93.1 (11.9) | ASD: 121.0 (6.1) | ||

| TD: 87.7 (9.6) | TD: 113.4 (10.2) | TD: 100.2 (9.8) | TD: 125.7 (8.7) | ||

| CRYSTALIZED Cognition | 93.2 (9.6)A | 100.4 (7.2)B | 121.7 (9.3)C | 123.9 (6.4)C | 0.001 |

| ASD: 92.1 (9.9) | ASD: 101.0 (7.3) | ASD: 122.0 (10.4) | ASD: 125.3 (4.0) | ||

| TD: 97.7 (6.9) | TD: 100.2 (7.3) | TD: 121.0 (7.2) | TD: 123.7 (6.7) | ||

| ASEBA DSM-ADHD | 57.0 (7.4) | 54.2 (5.6) | 57.1 (7.3) | 52.7 (6.5) | 0.03 |

| ASD: 58.4 (7.6) | ASD 57.2 (7.8) | ASD: 59.7 (7.4) | ASD: 66.3 (11.0) | ||

| TD: 51.7 (2.7) | TD: 52.9 (4.0) | TD: 51.8 (2.8) | TD: 50.7 (1.3) | ||

| ABAS GAC | 86.1 (17.6)A | 93.9 (16.9) | 88.5 (15.3)A | 101.4 (14.8)B | 0.007 |

| ASD: 79.2 (12.7) | ASD: 78.6 (7.7) | ASD: 80.8 (10.9) | ASD: 82.3 (5.7) | ||

| TD: 110.2 (9.2) | TD: 100.8 (15.5) | TD: 103.9 (10.4) | TD: 104.6 (13.4) | ||

| ADOS CSSb | 8.1 (1.3) | 7 (1.7) | 7.7 (1.7) | 6.7 (2.5) | 0.22 |

| % of Total ASD participants | 36% | 15% | 44% | 5% |

Groups with different capital letters A, B, C, and D (in superscripts) differ significantly following post-hoc multiple comparison correction (Holm Bonferroni).

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ABAS: Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADOS: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASEBA: Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment; CSS: calibrated severity score; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; FSIQ: Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; GAC: General Adaptive Composite; PRI: Perceptual Reasoning Index; VCI: Verbal Comprehension Index.

From a one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test.

ASD only.

EC1: EC1 was primarily comprised of participants with IQs in the average range, but lower than those found in EC3 and EC4. They exhibited relatively low scores on all subtests. Eighty percent of this group were autistic. Thirty-six percent of participants with ASD were assigned to this group.

EC2: Members of EC2 also had IQs in the average range that were lower than those in EC3 and EC4. They showed relatively worse performance on subtests indexing Crystallized versus Fluid Cognition. Approximately one-third of the members of this group were autistic. Fifteen percent of participants with ASD were members of this group.

EC3: Members of EC3 had FSIQs in the high average range. EC3 exhibited stronger Crystallized versus Fluid Cognition. Approximately two-third of the members of this group were autistic. Forty-four percent of participants with ASD were members of EC3.

EC4: Members of EC4 had mean total IQs in the high average range. They exhibited the highest performance across all NIHTB-CB subtests. This group was predominantly comprised of TD (87%). Only 5% of participants with ASD were classified as EC4.

There were significant EC group differences in FSIQ. Thus, we conducted additional analyses examining group differences in the verbal and nonverbal components of IQ and the association between IQ and Fluid Cognition and IQ and Crystallized Cognition across the EC groups. For the Fluid Cognition model, the interaction between IQ and EC group did not approach significance. For the Crystallized Cognition model, there was an association between IQ and EC group that approached a trend level (P = 0.103). Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used for analyses of ADHD, ABAS-3 composite (GAC), and ADOS-2 scores. These showed that there was a significant effect of EC group for mean ADHD scores [χ2(3) = 12.89, P = 0.005]. Due to the need to conduct multiple follow-up pairwise contrasts, the target alpha was adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni method [Holm, 1979]. EC4 (M = 52.7, SD = 6.4) had significantly lower ADHD symptoms than EC1 (M = 57.0, SD = 7.4; U = 198.50, P = 0.045) and EC3 (M = 57.0, SD = 7.3; U = 253.50, P = 0.006). ABAS-3 GAC scores also differed between EC groups [χ2(3) = 10.20, P = 0.017]. Post-hoc contrasts revealed that EC4 (M = 101.4, SD = 14.8) had significantly higher GAC scores than EC1 (M = 86.1, SD = 17.6; U = 154.5, P = 0.035) and EC3 (M = 88.5, SD = 15.3; U = 228.5, P = 0.030). There was no significant effect of EC group for mean ADOS CSS scores [χ2(3) = 3.26, P = 0.353].

Discussion

We report results of the first study to compare performance on the NIHTB-CB in a relatively large, cross-sectional, age, and IQ case-matched group of adolescents and young adults with ASD versus TD. The ASD group demonstrated poorer performance on all subtests of Fluid Cognition, except working memory. There were no associations between parent-reported ADHD symptoms and cognition subtest scores in either group. There were significant positive associations between age and Crystallized and Fluid Cognition in both groups. ASD showed significantly lower early scores on Fluid Cognition than TD and this pattern persisted throughout adolescence. An LPA with both groups showed that a four-group latent class model best fit data, with members of both groups in each of the four classes. Most individuals with ASD were classified in either EC1 (36%) or EC3 (44%) and exhibited relatively stronger performance on Crystallized versus Fluid Cognition. The EC groups did not differ in ASD symptoms. When compared to the most able group (EC4), who also displayed the lowest ADHD symptoms, adaptive functioning was lower in groups that consisted predominantly of autistic persons (EC1 and EC3). However, these last findings must be interpreted with caution as described more fully below as part of the study limitations.

While the overall pattern of generally weaker Fluid Cognition performance in ASD versus TD was expected, the lack of relative impairments in working memory and the lack of an association between ADHD symptoms and subtest performance were not. With respect to working memory, while the Toolbox LSWM task has been well-validated, it only correlates moderately with other measures of working memory [Tulsky et al., 2014]. Perhaps the LSWM task was relatively easier for those with ASD because it involved visual information processing [Hamilton et al., 2018]. Stimuli also were accompanied by the corresponding word, further supporting encoding and task performance. Furthermore, many of the trials on the task did not involve the need to inhibit prepotent response tendencies or to switch stimulus sets, meaning that EC demands were minimized [Hogeveen et al., 2018; Krug et al., 2020]. Finally, several studies have shown that individuals with average or better intellectual functioning, like those in the current study, do not exhibit working memory impairments [Ozonoff & Strayer, 2001; Russell et al., 1996].

The lack of significant correlations between NIHTB-CB subtest scores and parent-reported ADHD symptoms may be due to the low base rate of ADHD in our sample and measurement issues. While the NIHTB-CB is well-validated, it is brief and does not assess all domains of EC in a fine-grained way. Furthermore, use of a more comprehensive battery of ADHD measurements that included clinical interviews could have resulted in more nuanced findings. Still, results in this field have been mixed, with one of the largest studies to date concluding that the EC impairments of those with ASD could not be attributed to ADHD symptoms [Karalunas et al., 2018].

Replicating the findings of Brunsdon and colleagues [Brunsdon & Happe, 2014], we found that a small group of autistic participants did perform comparably to TD. This suggests that not all autistic persons have the same weaknesses or treatment needs, and that EC profiles are some-what transdiagnostic. These findings have clinical and intervention implications. Given their relatively weaker Fluid Cognition abilities, many with ASD will require treatments and services that help scaffold the development of this more flexible form of cognition. It is interesting that, despite their lower IQs, ASD in EC groups 1 and 3 exhibited relatively stronger Crystallized versus Fluid Cognition, speaking to the fact that they may use the verbal abilities to compensate for their flexibility deficits. Thus, these individuals may benefit from cognitive training programs designed to improve their language abilities or to ameliorate general intellectual disability that may impede flexibility [Eack et al., 2018; Kirk, Gray, Ellis, Taffe, & Cornish, 2016]. Given the importance of attention to the development of cognitive skills, and our findings of deficits in groups with a higher proportion of autistic persons [Diamond, 2013], they also might benefit from neural retraining interventions designed to ameliorate attention problems [Steiner, Sheldrick, Gotthelf, & Perrin, 2011; Tamm, Epstein, Peugh, Nakonezny, & Hughes, 2013]. Cognitive flexibility training to enhance fluid cognition also may be helpful. Finally, the current study makes clear the importance of services and supports that remediate adaptive functioning deficits [de Vries, Prins, Schmand, & Geurts, 2014].

The current study had several limitations. First, due to the desire to compare the ASD and TD group profiles, we combined the samples to include all participants for this part of the analysis. This resulted in some small groups with uneven numbers of ASD and TD participant. For example, EC2 and EC4 had only ten and three ASD participants, respectively, whereas EC1 had only six TYP – meaning that we lacked sufficient statistical power to clearly investigate within group or diagnostic group by symptom interactions for different clinical variables across EC groups, although we do include raw scores by diagnostic group for illustrative purposes. Another issue associated with having mixed diagnostic groups was that certain outcomes like ASD symptoms and functioning were highly confounded with EC group composition (e.g. adaptive functioning was poorest in EC1 and EC3, which also had the highest proportion of participants with ASD). Also problematic was that all the subscales assessing Fluid and Crystallized Cognition were used in deriving the groups so it would not be valid to examine them. We suggest that these limitations all illustrate that there is a need for a larger overall sample with larger numbers of ASD and TD across them as a means of moving forward. Second, it is important to remember that the study was cross-sectional, and findings of associations between age and the development of cognitive functioning await replication in a longitudinal study. Finally, the proportion of participants with ADHD and ASD in this sample was low, and assessment was based on one parent-report questionnaire. A future study with more rigorous assessment of ADHD across multiple informants is required, and a larger sample of participants with ASD and ADHD clearly is warranted.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that although a small percentage of autistic persons possess EC profiles that are similar to those found in TD, they most commonly show relatively poorer fluid cognition. This was true despite the fact that participants possessed intellectual ability levels in the average or better range. In this relatively small sample, ADHD symptoms were lowest in group with the highest Toolbox scores and greatest proportion of TD participants, while adaptive functioning was poorest in the groups with the highest proportion of autistic persons.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Common autism and other measures.

Table S1. Model fit statistics and class probabilities for LPA models with two to five classes.

Figure S1. Components of executive control: measurement, moderators, and everyday behavior.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the participants and their families for participating in the study. We would also like to thank Jennifer Farren, B.A., Andria Farrens, B.S., Sarah Mahdavi, B.S., Matthew Elliott, B.S., Garrett Gower, B.S., and Ashley Tay, B.S., who worked as research assistants during the study, and assisted in data collection, and Vanessa Reinhardt, PhD, who was a Post-Doc in our Lab for helpful comments during data collection.

We would also like to thank our funders. During this work, Dr. M.S. and her Lab were supported by R01MH106518 and R01MH103284. Dr. D.H. was supported by R01HD076189. Dr. A.M.I. was supported in part by P50HD103526.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Solomon, Gordon, Iosif, Krug, Mundy, & Hessl and Raphael Geddert report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Akshoomoff N, Newman E, Thompson WK, McCabe C, Bloss CS, Chang L, … Jernigan TL (2014). The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery: Results from a large normative developmental sample (PING). Neuropsychology, 28(1), 1–10. 10.1037/neu0000001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Shalom D (2003). Memory in autism: Review and synthesis. Cortex, 39(4–5), 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer C, Rosello B, Colomer C, Baixauli I, & Miranda A (2018). Children with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Relationships between symptoms and executive function, theory of mind, and behavioral problems. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 83, 260–269. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertollo JR, Strang JF, Anthony LG, Kenworthy L, Wallace GL, & Yerys BE (2020). Adaptive behavior in youth with autism spectrum disorder: The role of flexibility. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(1), 42–50. 10.1007/s10803-019-04220-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, & Choudhury S (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 296–312. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler D, Gaigg S, & Lind S (2011). Memory in autism: binding, self, and brain. In Roth I & Rezaie P (Eds.), Researching the autistic spectrum: Contemporary perspectives (pp. 316–347). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon VE, Colvert E, Ames C, Garnett T, Gillan N, Hallett V, … Happe F (2015). Exploring the cognitive features in children with autism spectrum disorder, their cotwins, and typically developing children within a population-based sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56 (8), 893–902. 10.1111/jcpp.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon VE, & Happe F (2014). Exploring the ‘fractionation’ of autism at the cognitive level. Autism, 18(1), 17–30. 10.1177/1362361313499456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Jones CR, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Baird G, & Happé F (2011). Defining the cognitive phenotype of autism. Brain Research, 1380, 10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ SE, Kester LE, Bodner KE, & Miles JH (2011). Evidence for selective inhibitory impairment in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychology, 25(6), 690–701. 10.1037/a0024256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Constantine LJ, Hendren R, Rocke D, & Ozonoff S (2009). Examining executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and typical development. Psychiatry Research, 166(2–3), 210–222. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig F, Margari F, Legrottaglie AR, Palumbi R, De Giambattista C, & Margari L (2016). A review of executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2016, 1191–1202. 10.2147/ndt.s104620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries M, Prins P, Schmand B, & Geurts H (2014). Working memory and cognitive flexibility-training for children with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(5), 566–576. 10.1111/jcpp.12324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty SS, Greenwald DP, Litschge MY, Porton SA, Mazefsky CA, & Minshew NJ (2018). Cognitive enhancement therapy for adult autism spectrum disorder: Results of an 18-month randomized clinical trial. Autism Research, 11(3), 519–530. 10.1002/aur.1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers S, Nyden A, Gillberg C, Sandberg AD, Dahlgren SO, Hjelmquist E, & Oden A (1997). Asperger syndrome, autism and attention disorders: A comparative study of the cognitive profiles of 120 children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(2), 207–217. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, & Eriksen CW (1974). Effects of noise letters upon identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception and Psychophysics, 16(1), 143–149. 10.3758/Bf03203267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faja S, & Dawson G (2014). Performance on the dimensional change card sort and backward digit span by young children with autism without intellectual disability. Child Neuropsychology, 20(6), 692–699. 10.1080/09297049.2013.856395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, Corbett B, & Solomon M (2009). The paradox of cognitive flexibility in autism. Trends Cognitive Sciences, 13(2), 74–82. 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, van den Bergh SF, & Ruzzano L (2014). Prepotent response inhibition and interference control in autism spectrum disorders: Two meta-analyses. Autism Research, 7, 407–420. 10.1002/aur.1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith EM, Pennington BF, Wehner EA, & Rogers SJ (1999). Executive functions in young children with autism. Child Development, 70(4), 817–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib A, Harris L, Pollick F, & Melville C (2019). A meta-analysis of working memory in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One, 14(4), e0216198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh SM, Walsh JA, Mazefsky CA, Minshew NJ, & Eack SM (2018). Processing speed is impaired in adults with autism spectrum disorder, and relates to social communication abilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2653–2662. 10.1007/s10803-018-3515-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CJ, Mammarella IC, & Giofre D (2018). Autisticlike traits in children are associated with enhanced performance in a qualitative visual working memory task. Autism Research, 11(11), 1494–1499. 10.1002/aur.2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, & Oakland T (2003). Adaptive behavior assessment system, second edition, (Vol 22, pp. 367–373). Torrance, CA: WPS. [Google Scholar]

- Happe F, Booth R, Charlton R, & Hughes C (2006). Executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Examining profiles across domains and ages. Brain and Cognition, 61(1), 25–39. 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EL (2004). Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogeveen J, Krug MK, Elliott MV, Carter CS, & Solomon M (2018). Proactive control as a double-edged sword in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(4), 429–435. 10.1037/abn0000345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Hawkey E, Gustafsson H, Miller M, Langhorst M, Cordova M, … Nigg JT (2018). Overlapping and distinct cognitive impairments in attention-deficit/hyperactivity and autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(8), 1705–1716. 10.1007/s10802-017-0394-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk HE, Gray KM, Ellis K, Taffe J, & Cornish KM (2016). Computerised attention training for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(12), 1380–1389. 10.1111/jcpp.12615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouklari EC, Tsermentseli S, & Monks CP (2018). Hot and cool executive function in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Cross-sectional developmental trajectories. Child Neuropsychology, 24(8), 1088–1114. 10.1080/09297049.2017.1391190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug MK, Elliott MV, Gordon AJ, Hogeveen J, Solomon M, Elliott MV, … Solomon M (2020). Proactive control in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: Unimpaired but associated with symptoms of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129, 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Fein D, Allen D, Dunn M, Feinstein C, Morris R, … Rapin I (2001). Executive functioning in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YT, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr., Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, … Rutter M (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30 (3), 205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, & Bishop S (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule: ADOS-2. Torrence, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Luna B (2009). Developmental changes in cognitive control through adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 37, 233–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Doll SK, Hegedus SJ, Minshew NJ, & Sweeney JA (2007). Maturation of executive function in autism. Biological Psychiatry, 61(4), 474–481. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maister L, Simons JS, & Plaisted-Grant K (2013). Executive functions are employed to process episodic and relational memories in children with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology, 27(6), 615–627. 10.1037/a0034492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes SD, & Calhoun SL (2007). Learning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Child Neuropsychology, 13(6), 469–493. 10.1080/09297040601112773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, & Cohen JD (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, & Chapman JP (2001). Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(1), 40–48. 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, & Wager TD (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulieres I, Hubert B, & Burack J (2006). Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 27–43. 10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (2017). Version 8, Mplus users guide. https://statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Norbury CF, Griffiths H, & Nation K (2010). Sound before meaning: Word learning in autistic disorders. Neuropsychologia, 48 (14), 4012–4019. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthen BO (2008). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(1), 182–182. 10.1080/10705510701793320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Cook I, Coon H, Dawson G, Joseph RM, Klin A, … Wrathall D (2004). Performance on Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery subtests sensitive to frontal lobe function in people with autistic disorder: Evidence from the Collaborative Programs of Excellence in Autism network. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, & Strayer DL (2001). Further evidence of intact working memory in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(3), 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano E (2012). The development of executive function in autism. Autism Research and Treatment, 2012, 146132. 10.1155/2012/146132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington BF, & Ozonoff S (1996). Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(1), 51–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poljac E, Hoofs V, Princen MM, & Poljac E (2017). Understanding behavioural rigidity in autism spectrum conditions: The role of intentional control. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(3), 714–727. 10.1007/s10803-016-3010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelse NN, Geurts HM, Franke B, Buitelaar JK, & Hartman CA (2011). A review on cognitive and brain endo-phenotypes that may be common in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and facilitate the search for pleiotropic genes. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(6), 1363–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Simonoff E, Kuntsi J, Asherson P, & Plomin R (2008). Evidence for overlapping genetic influences on autistic and ADHD behaviours in a community twin sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(5), 535–542. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Wallace GL, Lawson R, Wills MC, Dixon E, Yerys BE, & Kenworthy L (2013). Impairments in real-world executive function increase from childhood to adolescence in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology, 27(1), 13–18. 10.1037/a0031299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J, Jarrold C, & Henry L (1996). Working memory in children with autism and with moderate learning difficulties. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(6), 673–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, & Lord C (2003). SCQ: Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Samson F, Mottron L, Soulieres I, & Zeffiro TA (2012). Enhanced visual functioning in autism: An ALE meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 33(7), 1553–1581. 10.1002/hbm.21307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt LM, White SP, Cook EH, Sweeney JA, & Mosconi MW (2018). Cognitive mechanisms of inhibitory control deficits in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(5), 586–595. 10.1111/jcpp.12837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Hogeveen J, Libero L, & Nordahl C (2017). An altered scaffold for information processing: Cognitive control development in adolescents with autism. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2(6), 464–475. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, McCauley JB, Iosif AM, Carter CS, & Ragland JD (2016). Cognitive control and episodic memory in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia, 89, 31–41. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ozonoff SJ, Cummings N, & Carter CS (2008). Cognitive control in autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 26(2), 239–247. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ozonoff SJ, Ursu S, Ravizza S, Cummings N, Ly S, & Carter CS (2009). The neural substrates of cognitive control deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia, 47(12), 2515–2526. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ragland JD, Niendam TA, Lesh TA, Beck JS, Matter JC, … Carter CS (2015). Atypical learning in autism spectrum disorders: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of transitive inference. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulieres I, Dawson M, Samson F, Barbeau EB, Sahyoun CP, Strangman GE, … Mottron L (2009). Enhanced visual processing contributes to matrix reasoning in autism. Human Brain Mapping, 30(12), 4082–4107. 10.1002/hbm.20831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner NJ, Sheldrick RC, Gotthelf D, & Perrin EC (2011). Computer-based attention training in the schools for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A preliminary trial. Clinical Pediatrics (Phila), 50(7), 615–622. 10.1177/0009922810397887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang JF, Anthony LG, Yerys BE, Hardy KK, Wallace GL, Armour AC, … Kenworthy L (2017). The flexibility scale: Development and preliminary validation of a cognitive flexibility measure in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2502–2518. 10.1007/s10803-017-3152-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm L, Epstein JN, Peugh JL, Nakonezny PA, & Hughes CW (2013). Preliminary data suggesting the efficacy of attention training for school-aged children with ADHD. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 4, 16–28. 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MS, Annaz D, Ansari D, Scerif G, Jarrold C, & Karmiloff-Smith A (2009). Using developmental trajectories to understand developmental disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(2), 336–358. 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0144) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulsky DS, Carlozzi N, Chiaravalloti ND, Beaumont JL, Kisala PA, Mungas D, … Gershon R (2014). NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB): List sorting test to measure working memory. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 20(6), 599–610. 10.1017/S135561771400040X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang YB, Liu LL, Cui JF, Wang J, Shum DH, … Chan RC (2017). A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology Review, 27(1), 46–61. 10.1007/s11065-016-9336-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1999). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2011). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence - Second Edition: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Yerys BE, Wallace GL, Harrison B, Celano MJ, Giedd JN, & Kenworthy LE (2009). Set-shifting in children with autism spectrum disorders: Reversal shifting deficits on the Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift Test correlate with repetitive behaviors. Autism, 13(5), 523–538. 10.1177/1362361309335716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD (2006). The Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS): A method of assessing executive function in children. Nature Protocols, 1(1), 297–301. 10.1038/nprot.2006.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Common autism and other measures.

Table S1. Model fit statistics and class probabilities for LPA models with two to five classes.

Figure S1. Components of executive control: measurement, moderators, and everyday behavior.