Abstract

Obesity impairs endothelial-mediated vasodilation, the earliest step in vascular disease and a contributor to hypertension. We previously demonstrated that endothelial cell mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) deletion prevents obesity-induced microvascular dysfunction in females by increasing nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation. Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) can oppose MR function, therefore we hypothesized that ERα mediates the benefits of endothelial MR deficiency.

Females lacking endothelial MR or wildtype littermates were fed control or high fat diet for 20 weeks to cause obesity. MR deletion improved mesenteric artery endothelial-dependent vasodilation in obese females and ERα inhibition ex vivo negated this protective effect. Endothelial MR deletion results in significantly more ERα mRNA and protein. In vitro, estrogen increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation, which is inhibited by aldosterone and dependent on MR. Both proteins co-immunoprecipitate with striatin and a mimetic peptide that disrupts ERα-striatin binding also decreased MR-striatin interaction. Finally, removing endothelial MR in obese females restored endothelial function by increasing the nitric oxide component of vasodilation. Combined deletion of endothelial ERα negated the benefit of endothelial MR deletion.

These results indicate that endothelial ERα prevents the detrimental effects of MR in obesity by increasing nitric oxide to rescue vasodilation in females. MR and ERα may compete for striatin binding within endothelial cells to regulate nitric oxide. These data identify a novel mechanism that promotes MR antagonism to prevent obesity-induced microvascular dysfunction in females.

Keywords: mineralocorticoid receptor, estrogen receptor alpha, obesity, endothelial cell, vasodilation, striatin

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a potent cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor with rapidly increasing prevalence, particularly in females.1 Obesity and associated metabolic abnormalities negate pre-menopausal protection of women from CVD, thereby substantially impacting women’s health.2-4 Obesity is associated with impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation in small resistance arteries, an important contributor to the development of hypertension and an early manifestation of CVD.5-7 This is important because endothelial dysfunction in small arterioles, rather than large conduit arteries, predicts the 5 year risk of a cardiovascular event and both female sex and increased body mass index are associated with worse endothelial function.8

Obesity is associated with increased circulating levels of aldosterone likely due to factors released from adipose tissue that promote aldosterone release.9-13 Aldosterone activates the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in the kidney, which contributes to sodium retention and regulates blood pressure. This may contribute to the association between obesity and hypertension. Circulating aldosterone levels are particularly high in obese females14, resulting in excess MR activation. The MR is also expressed in endothelial cells (EC) where it contributes to vascular dysfunction in response to cardiovascular risk factors.15,16

EC-MR activation increases reactive oxygen species production17,18 and decreases available nitric oxide (NO)19 thereby promoting vascular constriction20, inflammation21,22 and stiffness23. Females are more affected as they exhibit more EC-MR expression and this sex difference in MR activation is further exacerbated in obesity due to the higher aldosterone levels in females.24,25,26 We recently demonstrated that EC-specific MR deletion (EC-MR-KO) rescues female mice from obesity-induced endothelial dysfunction, however the mechanism has not been determined.

Like aldosterone, the female sex hormone estrogen is a steroid hormone which binds to intracellular estrogen receptors (ER). Endothelial ER alpha (ERα) isoform activation accelerates reendothelialization after vascular injury and promotes vasodilation by increasing NO production via endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). ERα binds to the scaffolding protein striatin via amino acids 176-253 and this interaction is necessary for estrogen to activate eNOS by phosphorylation to induce NO production.27,28 MR also binds to striatin when activated by aldosterone, inducing EC production of reactive oxygen species.17

Obese female mice have impaired microvascular endothelial function and we previously demonstrated that EC-MR deletion preserves vasodilation by preserving nitric oxide synthase (NOS) component of vasodilation specifically in females.26 Here we explore the mechanism by which EC-MR-KO protects female mice from obesity-induced endothelial dysfunction and hypothesize that EC-ERα may mediate these benefits.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. See supplemental material for detailed methods.

Animal Studies

Experiments were approved by Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female mice were euthanized under isoflurane. Small mesenteric arteries were mounted in a wire myograph, preconstricted with phenylephrine (PE) and endothelial-dependent-dilation to acetylcholine was measured.

Molecular Biology

EA.hy926 cells (human endothelial cell hybrid line) stably expressing ERα or HEK293 cells were cultured and treated as previously described27,29

Statistics

Data were collected and analyzed by genotype and/or treatment blinded investigators. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPadPrism version 8. Four groups and concentration response curves were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc. Three groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Sidak post hoc. Data is presented as mean +/− standard error. Significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Female Mice Lacking the Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Endothelial Cells are Protected from Obesity-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction

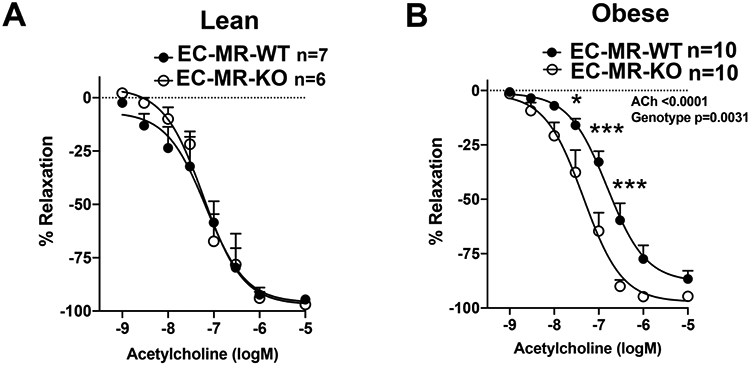

Female EC-MR-WT and EC-MR-KO littermates were randomized to normal chow or high fat diet for 20 weeks. High fat feeding resulted in a significant increase in body weight, fasting glucose, and serum aldosterone when compared to lean littermates consistent with the development of obesity with metabolic abnormalities (Table S1). There was no significant difference in these parameters between EC-MR-WT and EC-MR-KO mice. Endothelial-dependent vasodilation to ACh was quantified ex vivo in 2nd-3rd order mesenteric arteries. Consistent with our prior findings26, EC-MR deletion did not impact endothelial-dependent vasodilation in lean female mice as evidenced by near complete peak vasodilation (Figure 1A). In obese female mice (Figure 1B), 86% peak dilation occurs in EC-MR-WT mice while obese EC-MR-KO females have significant improved endothelial function with preserved vasodilation capacity.

Figure 1. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptor Knockout (EC-MR-KO) Improves Obesity-Induced Microvascular Vasodilation Impairment.

Female EC-MR intact (EC-MR-WT) and EC-MR-KO mice were fed normal (lean) or high fat diet (obese) for 20 weeks and endothelial-dependent vasodilation was measured ex vivo using acetylcholine (ACh). (A) In lean females, there is no difference in vasodilation comparing EC-MR-WT (closed circles) versus EC-MR-KO (open circles). (B) In obese females, vasodilation is improved in EC-MR-KO versus EC-MR-intact. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, 2-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc.

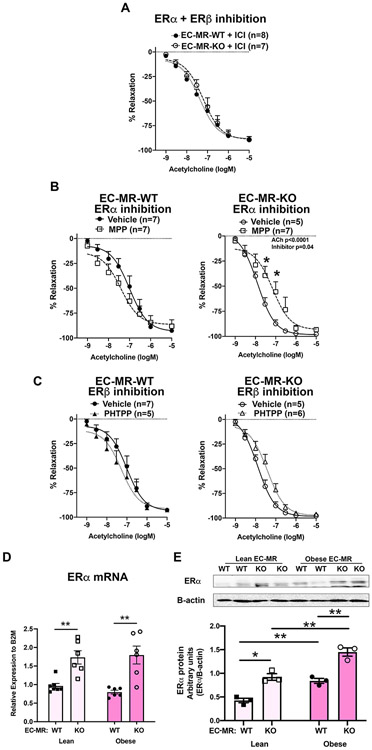

Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) Contributes to the Vascular Benefits of EC-MR Deletion in Obese Females

Since the benefit of EC-MR deletion is specific to females26, we next tested whether ER might contribute to the improved vasodilation in obese EC-MR-KO females. Mesenteric arteries from obese female mice were incubated ex vivo for 30 minutes with ICI181780 (ICI), an estrogen receptor antagonist (inhibits ERα and ERβ). ICI inhibition in obese females abrogated improved dilation seen in EC-MR-KO (Figure 1B). Hence, there was no longer any genotype difference in endothelial function with ICI treatment (Figure 2A). To determine which ER isoform mediates this effect, arteries were incubated with MPP, a specific ERα inhibitor (Figure 2B), or PHTPP, a specific ERβ inhibitor (Figure 2C). ERα inhibition did not impact vasodilation in EC-MR-WT obese females but significantly attenuated ACh dilation in EC-MR-KO obese female arteries (Figure 2B) supporting that ERα contributes to the improved endothelial function in obese mice lacking EC-MR. There was no significant effect of acute ERβ inhibition on vasodilation in obese females with or without EC-MR (Figure 2C). In lean females, neither ERα nor ERβ inhibition impacted ACh dilation (Figure S1). We next examined ERα expression in mesenteric arteries from EC-MR-WT and EC-MR-KO mice. ERα mRNA and protein was significantly increased in both lean and obese female mice lacking EC-MR (Figure 2D). ERα protein was also significantly increased in obese versus lean mice of the same genotype (Figure 2E). In human EC, MR inhibition with spironolactone also increased endogenous levels of ERα protein (Figure S2). Together, these data support that ERα expression is increased in vessels from mice lacking EC-MR and that ERα is contributing to the benefits of EC-MR deletion.

Figure 2. Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) Contributes to the Vascular Benefits of Endothelial MR Deletion in Obesity.

Mesenteric arteries from obese females were incubated with ER inhibitors for 30 minutes and ACh vasodilation measured. (A) Incubation with the combined ERα and ERβ inhibitor ICI182,780 eliminated the improved dilation previously seen in arteries from obese EC-MR-KO mice. (B) Incubation with vehicle versus the ERα-specific inhibitor MPP in EC-MR-WT arteries and EC-MR-KO arteries. ERα inhibition significantly decreased endothelial-dependent vasodilation in obese EC-MR-KO mice. *p<0.05, 2-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test. (C) Incubation with vehicle or the ERβ-specific inhibitor PHTPP in obese female EC-MR-WT arteries and obese female EC-MR-KO arteries. ERβ inhibition did not significantly impact vasodilation. 2-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test. (D) ERα mRNA and (E) protein expression quantified in mesenteric artery tissue from lean and obese EC-MR-WT and EC-MR-KO females. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test.

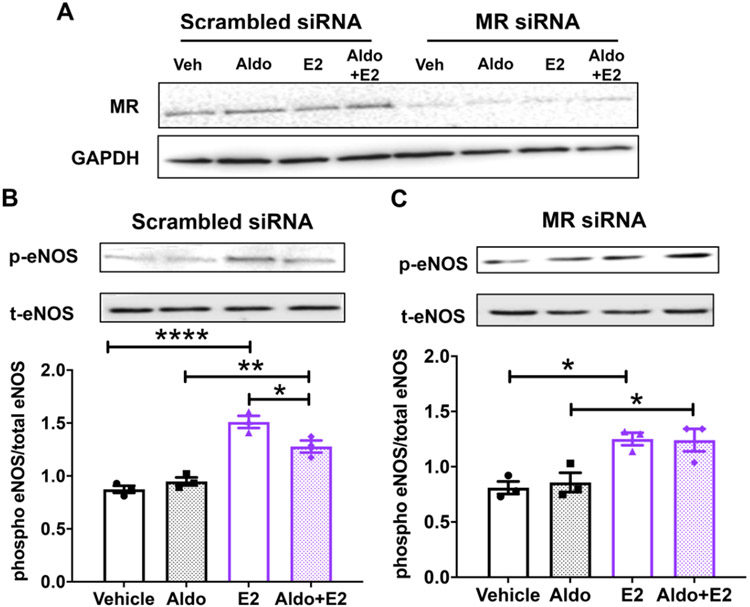

Aldosterone Inhibits Estrogen-Induced eNOS Phosphorylation via MR in Human Endothelial Cells

EC ERα activation by estrogen increases eNOS activity by phosphorylation of serine 1177.27 As females are exposed to elevated aldosterone when they become obese, we examined the impact of aldosterone on estrogen-induced eNOS phosphorylation. ERα-expressing human EAhy926 ECs were treated with MR siRNA or scrambled siRNA control and MR knock down was confirmed (Figure 3A). Next, these cells were treated with physiologically relevant concentrations of aldosterone, estrogen or both hormones with appropriate vehicle controls for 20 minutes. In control siRNA-treated ECs, aldosterone alone had no effect on eNOS phosphorylation and, as expected, estrogen significantly increased eNOS phosphorylation at S1177. When MR is present, addition of aldosterone significantly attenuated the estrogen-induced increase in eNOS phosphorylation (Figure 3B), showing that aldosterone inhibits estrogen rapid signaling in EC in vitro. In MR siRNA-treated cells, estrogen still increased eNOS phosphorylation. However, when MR was knocked down, aldosterone had no impact on estrogen-induced on eNOS phosphorylation (Figure 3C). These data show that aldosterone prevents estrogen induction of eNOS activity in ECs in a MR-dependent manner.

Figure 3. Aldosterone Inhibits Estrogen-Induced eNOS Phosphorylation via MR in Endothelial Cells.

(A) EAhY endothelial cells stably expressing ERα were treated with scrambled control siRNA or MR siRNA for 48 hours and MR knock down was demonstrated by immunoblotting. (B-C) Cells were treated for 20 minutes with vehicle, 10 nM aldosterone (Aldo), 10 nM estradiol (E2) or E2+Aldo. Ratio of phospho-eNOS to total eNOS was quantified by immunoblotting: (B) in control cells with MR or (C) with MR knock down. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, N=3, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc.

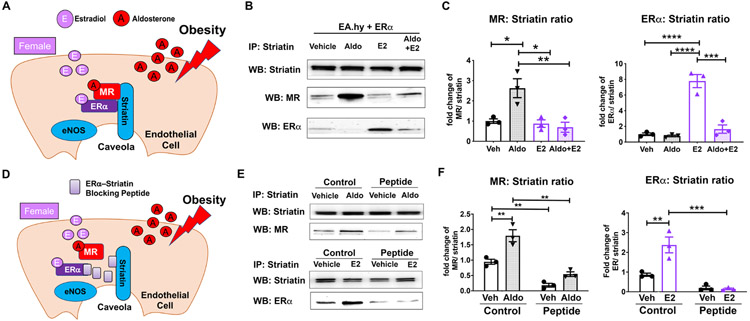

MR and ER Interact with Striatin in Endothelial Cells and Aldosterone Decreases the ERα–Striatin Interaction

ERα must interact with the scaffolding protein striatin in EC caveolae to regulate eNOS phosphorylation.27 MR is also known to regulate signaling via interactions with striatin.17 (see Figure 4A for model). Thus, we tested the impact of each hormone on the relative amount of MR or ERα bound to striatin by co-immunoprecipitation. ECs were treated with aldosterone +/− estrogen as in Figure 3 and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-striatin antibody and immunoblotted for striatin, MR and ERα (Figure 4B). The amount of MR or ERα pulled down with striatin was quantified and normalized to the total amount of striatin pulled down and expressed as a fold change relative to vehicle treatment (Figure 4C). Aldosterone significantly increased the amount of MR bound to striatin and this was prevented by estrogen. Estrogen significantly increased the amount of ERα bound to striatin and, as with eNOS phosphorylation in Figure 3B, estrogen induction of ERα-striatin complex formation was prevented by aldosterone.

Figure 4. MR and ER Complex with Striatin in Endothelial Cells and Aldosterone Decreases the ERα–Striatin Interaction.

(A) Schematic showing an endothelial cell (EC) exposed to increased aldosterone during obesity, which binds to MR. In females, estradiol is bound to ERα. Both receptors can bind to striatin in EC membrane caveolae to potentiate rapid signaling. (B) Representative immunoblot of EaHY human EC line with stable ERα expression treated with vehicle, 10 nM aldosterone (Aldo), 10 nM estradiol (E2) or E2+Aldo. Cells lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-striatin antibody and then immunoblotted for striatin, MR, or ERα. (C) The amount of MR or ER bound to striatin was quantified. N=3-4. (D) Schematic showing a cell expressing an ERα mimetic blocking peptide (amino acids 176-253) which prevents ERα-striatin interaction. (D) Representative blots of HEK293 cells overexpressing MR and ERα +/− co-expression of ERα-striatin blocking peptide. Cells were treated with vehicle, Aldo or E2 for 20 minutes and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with striatin antibody and immunoblotted for striatin, MR, and ERα. (F) The amount of MR or ERα normalized to striatin was significantly decreased with co-expression of the ERα -striatin disrupting peptide when compared to vector plasmid (Control). N=3. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 via one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc

Previous work characterized the ERα binding domain that interacts with striatin and found that overexpression of the ERα peptide containing this region (amino acids 176-253, Figure 4D) prevents ERα binding to striatin and inhibits ERα signaling to induce eNOS phosphorylation.27 Thus, we examined whether overexpression of the ERα amino acid 176-253 would modulate ER or MR binding to striatin when the receptors are co-expressed. HEK cells were transfected with plasmids to express both MR and ERα with or without the flag tagged ER176-253 peptide. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with striatin and blotted for MR or ERα (Figure 4E). As expected, expression of the peptide prevented estrogen induced recruitment of ERα to striatin. The same ERα176-253 peptide also significantly decreased basal MR binding to striatin and prevented further aldosterone-induced MR recruitment to striatin (Figure 4F).

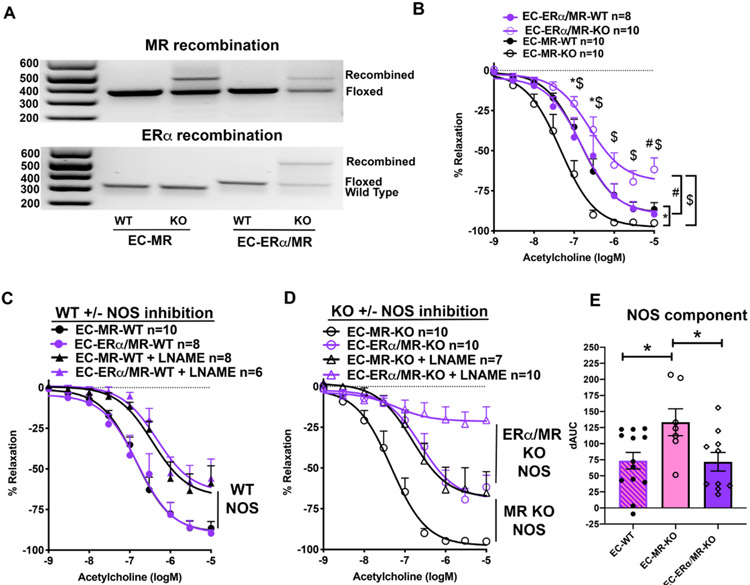

EC-ERα Deletion Eliminates the Protective Impact of EC-MR-KO on Microvascular NO Contribution to Vasodilation in Obese Females

The data presented thus far are consistent with a model in which when MR is deleted from ECs in obese females, the combination of increased ERα expression and enhanced recruitment of ERα to striatin results in the increased eNOS activity to enhance vasodilation in obese EC-MR-KO mice. To test this model, a double knockout mouse was created lacking MR and ERα (EC-ERα/MR-KO) specifically in EC. Lung tissue rich in ECs was used to confirm recombination of MR and ERα via PCR (Figure 5A). EC-MR-KO and EC-ERα/MR-KO female mice and their respective WT littermates were fed a high fat diet for 20 weeks resulting in obesity with metabolic dysfunction with no difference in weight, glucose or aldosterone in obese EC-ERα/MR-KO compared to EC-ERα/MR-WT littermates (Table S1). There was also no difference in basal lumen diameter or phenylephrine constriction in any of the groups (Table S2). Again, EC-MR-KO improved vasodilation relative to WT but added deletion of ERα mitigated the benefits of EC-MR deletion and further impaired endothelial function in lean (Figure S3) as well as obese EC-ERα/MR-KO mice relative to WT or EC-MR-KO littermates (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Combined ERα and MR Deletion in EC Negates Improved EC-MR-KO Endothelial Dependent Vasodilation by decreasing NO Contribution.

(A) Representative images of PCR confirming gene recombination using DNA from EC-rich lung tissue from EC-MR-WT/KO and EC-ERα/MR-WT/KO mice. PCR indicates the wild type MR allele, floxed MR allele and recombined MR (top image) and wild type ERα, floxed ERα, and recombined ERα (bottom image). (B) ACh vasodilation is impaired in EC-ERα/MR-KO females. EC-MR-WT and KO curves from Figure 1A are replotted here in black and compared directly. 2-Way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc. *p<0.05 EC-MR-WT vs EC-MR-KO; #p<0.05 EC-ERα/MR-WT vs EC-ERα/MR-KO; $p<0.05 EC-ERα/MR-KO vs EC-MR-KO. (C) Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) contribution to vasodilation in obese WT females. (D) NOS contribution in obese EC-MR-KO females and EC-ERα/MR-KO females. (E) NOS contribution to vasodilation was calculated as difference in the area under the curve (dAUC) between ACh dilation and ACh+NOS inhibition in each geneotype. WT females were combined from both WT groups (EC-MR-WT and EC-ERα/MR-WT). *p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc.

To determine the contribution of NOS to vasodilation in these mice, ACh concentration-response curves were compared between arteries with or without the NOS inhibitor LNAME. Figure 5C shows the vasodilation curves for all of the WT control animals revealing that the obese WT females regardless of the presence of floxed allelles (EC-MR-WT and EC-ERα/MR-WT) have overlapping vasodilation curves with a similar decline in vasodilator response to NOS inhibition (Figure 5C). Next, NOS inhibition in obese EC-MR-KO and the EC-ERα/MR double KO animals was compared (Figure 5D). As we previously demonstrated, obese female EC-MR-KO mice have preserved vasodilation and this is due to an increase in the NOS component of vasodilation (Figure 5D, black curves). EC-ERα/MR-KO arteries had impaired vasodilation that was further decreased by NOS inhibition. The difference in area between the curves +/− LNAME was calculated to determine the NOS component of vasodilation (Figure 5E). WT mice (EC-MR-WT and EC-ERα/MR-WT) were combined as their curves were nearly identical in Figure 5C. The significant increase in NOS-mediated vasodilation in EC-MR-KO vs EC-MR-WT obese female mice is lost in EC-ERα/MR-KO making the NOS component significantly lower in double KO compared to EC-MR-KO obese female mice (Figure 5E). These data support that EC-ERα is necessary for the benefits of MR deletion on female microvascular function and this benefit is mediated by an increase in the NOS component of vasodilation.

DISCUSSION

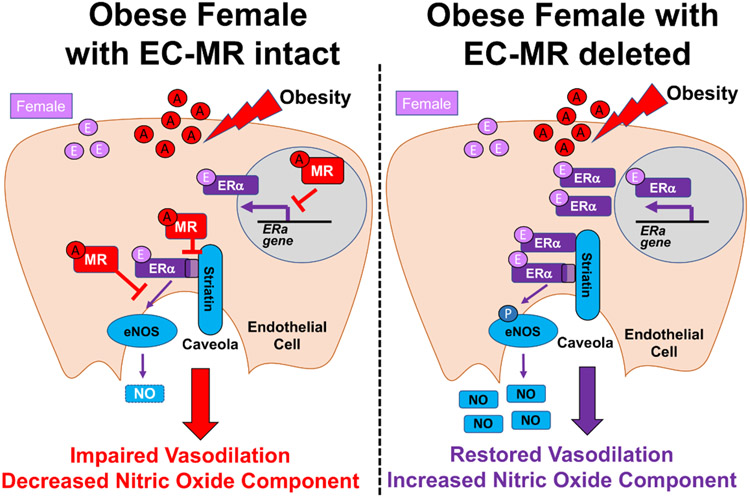

This is the first study to examine the interconnected signaling of EC-MR and EC-ERα in the microvasculature of obese female mice. EC-specific deletion of MR protects from obesity-induced vascular disfunction and this study identified the mechanisms by showing that; 1) The improvement in ex vivo microvascular dilation upon EC-MR deletion is mediated functionally by ERα, 2) Microvascular ERα mRNA and protein expression is upregulated when EC-MR is deleted or inhibited, 3) In human ECs, MR activation prevents estrogen-induced eNOS phosphorylation, 4) ERα and MR both bind to striatin, inhibit each other’s binding when activated by hormone, and can be displaced by the ERα striatin-binding peptide, and 5) In vivo, using our novel EC-ERα/MR double KO mouse, EC-ERα is necessary for the improvement in the NOS component of vasodilation in obese females lacking EC-MR. The results are consistent with the model in Figure 6 in which enhanced EC-MR activation in obese females; 1) suppresses ERα expression, 2) decreases ERα recruitment to the caveolae by striatin, and 3) impairs NOS contribution to vasodilation. This results in obesity-induced endothelial dysfunction (Figure 6, left), an important contributor to adverse cardiovascular outcomes in obese women. Conversely, when we remove/inhibit EC-MR in vitro or in vivo (Figure 6, right), microvascular ERα expression is increased and aldosterone no longer prevents estrogen-induced eNOS phosphorylation (Figure 3) resulting in increased microvascular NOS vasodilatory contribution and improved endothelial function (Figure 5E). We conclude that the balance between ERα and MR signaling maintains vascular homeostasis in female ECs, but when MR activation predominates in obesity, the benefit of estrogen on female vasodilation is lost. This is clinically important as obesity is associated with elevated aldosterone and impaired endothelial function in animals and humans, exacerbated in females, and results in detrimental cardiovascular outcomes in obese woman. The new data support future clinical testing of MR inhibition to restore endothelial function specifically in obese women.

Figure 6. Model for the Interaction of MR and ERα in Endothelial Cells to Regulate Microvascular Function in Obese Females.

Obesity is associated with increased aldosterone (A) in females which activates the MR in endothelial cells (left). MR in ECs decreases ERα mRNA and protein expression in resistance arteries. MR also decreases ERα binding to striatin and impairs estrogen-induced eNOS phosphorylation and the contribution of NOS to microvascular dilation. In EC-MR-KO females (right), aldosterone is increased but cannot bind to MR. Therefore, the microvasculature contains more ERα protein and ERα can interact more readily with striatin. This results in ERα-dependent increase in NOS contribution to vasodilation and prevents EC dysfunction in obese females.

This study sheds light on a controversy regarding the impact of aldosterone on EC function. Animal and human studies suggest that aldosterone impacts endothelial function although there are conflicting studies showing improved or worsening of vasodilation depending on the model or the patient population tested (reviewed in 30). Similarly, in vitro studies vary. Some show aldosterone increases, decreases, or has no effect on eNOS phosphorylation or NO production.17,19,31,32 The current study suggests that the impact of rapid aldosterone signaling via EC-MR on eNOS may depend on the presence of ERα or estrogen. For example, in Figure 3B, aldosterone alone has no impact on eNOS phosphorylation in cells grown in estrogen-free media. However, when estrogen is present, comparison of vehicle to aldosterone shows a decrease in eNOS phosphorylation, suggesting that MR is blocking eNOS activation in ECs. Since ER activators are present in phenol red-containing culture medium and in serum, different studies in the literature are effectively testing the impact of aldosterone under different conditions. In addition, ER expression in ECs changes with culture conditions and generally declines with cell passage. Some of the discrepancies in the literature regarding aldosterone and eNOS phosphorylation may be due to differences in ERα or estrogen that are not intentional.31,32

There are several potential mechanisms by which ER and MR signaling interact in ECs. ERα mRNA and protein expression in mesenteric arteries increased when EC-MR was deleted and ERα protein increased when EC-MR was inhibited in vitro. This supports a mechanism in which MR suppresses ERα mRNA transcription or stability in ECs resulting in increased ERα expression when MR is deleted or inhibited. A prior study in Kupffer cells similarly showed that MR suppresses ERα expression as myeloid-MR-KO increased ERα and MR overexpression repressed ERα expression.33 MR and ER are also both hormone-activated transcription factors and prior studies reveal that ERα blocks MR regulation of inflammatory gene transcription in EC which may contribute to sex differences in atherosclerosis.21,34 MR and ER both bind to striatin where they initiate rapid signaling cascades that regulate EC function. This study shows that MR activation decreases ERα recruitment to striatin and estrogen activation of eNOS. The finding that the peptide of ERα that dissociates ERα from striatin also dissociates MR from striatin suggests that the two receptors may compete for binding to the same site on striatin or form a tri-protein complex that requires a similar domain. Further studies are needed to clarify the details of these molecular interactions but overall, ERα and MR interact in at least three ways in ECs to integrate hormonal signals into changes in EC function.

The interaction between ERα and MR signaling in ECs has important clinical implications for our understanding of the impact of obesity on women’s cardiovascular health. Although premenopausal women are protected from cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke compared to age-matched men, this protection is lost in women with obesity and metabolic syndrome resulting in rising CVD risk in middle aged women.2-4 High body mass index is directly correlated with plasma aldosterone concentration in hypertensive humans35, even those treated with antihypertensives.36 Obese women exhibit higher circulating aldosterone, more hypertension, and a greater increase in cardiovascular related morbidity and mortality than obese men.1-3,14,37 The first cardiovascular consequence of excess adiposity is microvascular endothelial dysfunction.38 Our data suggests that in younger obese females, excess aldosterone activating EC-MR may negate the protection typically afforded by the presence of circulating estradiol and activation of endothelial ERα. Translating this into human therapeutic intervention are important next steps to combat the increase in cardiovascular-related mortality of pre-menopausal females. Small clinical trials (25 women in two studies) have specifically shown a greater benefit of MR antagonism in obese women.39,40 Obese women have a more beneficial blood pressure drop to MR antagonism than men.40 Animal studies also support the notion that MR antagonism could be particularly efficacious in obese females21,23,24,26,41-43 to prevent vascular dysfunction, but there is still a need for larger clinical studies in humans. MR antagonist are typically a fourth line anti-hypertensive, but this study and others provide a rationale for earlier use of MR antagonism to maintain endothelial function in obese women.

Some limitations to this study should be acknowledged. Testing acute ER inhibition on vasodilation using MPP or ICI182170 used whole arteries treated with inhibitors, thereby blocking ERα in smooth muscle as well as the EC. Thus, we cannot conclude that the result is mediated only by blocking EC-ER. However, in our EC specific KO mouse model, ERα combined with MR deletion recapitulated the inhibitor studies and further impaired EC-dependent vasodilation. The more profound response in the tissue-specific model could be due to differences between ER function in EC versus smooth muscle as well as the combined loss of acute signaling and longer term gene expression regulation by ERα in vivo that are important in maintenance of vascular physiology.44 This is consistent with the finding that lean EC-MR/ERα-KO mice have impaired endothelial function while acute ERα inhibition has no effect. We specifically focused on female (not male) microvascular function since our prior study showed that EC-MR deletion had microvascular benefits only in obese female mice. Future studies will be needed to assess whether these MR/ER interactions are relevant in males. Whether these mechanisms contribute to other important resistance artery functions including blood pressure regulation or vascular remodeling remains to be explored. Despite these limitations, this study describes a novel mechanism for vascular dysfunction in premenopausal obese females, provides insight into sex differences in the impact of metabolic risk factors on CVD, and supports testing of MR inhibition as a sex-specific therapeutic strategy to mitigate the adverse cardiovascular complications of obesity in the rapidly growing population of obese women with metabolic syndrome.

Perspectives

The incidence of obesity is rapidly rising, particularly in women, and the associated metabolic abnormalities mitigate the protection afforded to premenopausal woman from cardiovascular disease. This study provides preclinical data supporting a novel molecular mechanism for this observation. Obesity is associated with elevated serum aldosterone and increased expression of the aldosterone-binding mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in endothelial cells (EC). This study demonstrates that obesity-induced microvascular endothelial dysfunction in females depends on EC-MR. When EC-MR is deleted, endothelial function is improved due to an increase in the nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) component of vasodilation. Enhanced microvascular endothelial function in females is mediated by estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in ECs and this is impaired by EC-MR activation in obesity through two potential mechanisms: 1) the presence of EC-MR suppresses ERα expression in arteries; and 2) EC-MR activation decreases estrogen-induced activation of eNOS by preventing ERα-striatin interaction. These mechanisms may explain the disproportional impact of obesity on vascular function in premenopausal obese females and supports testing of MR inhibition as a sex-specific therapeutic strategy to mitigate the adverse cardiovascular complications of obesity in women.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is New:

Microvascular dysfunction in obese females is mediated by the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in endothelial cells (EC) by suppressing the ability of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) to enhance nitric oxide production.

Mechanistically, EC-MR suppresses expression of microvascular ERα and prevents ERα recruitment to caveoli by striatin where it activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

What is Relevant:

The prevalence of obesity is increasing, especially in women, resulting in increased activation of the MR which promotes hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

This study provides an explanation for the loss of cardiovascular protection in premenopausal women with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Summary:

MR in endothelial cells prevents vascular protection mediated by ERα in obese females supporting the potential for MR inhibition to protect obese women from cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NIH grants T32HL007609 (L.A.B.), R25GM066567 (B.V.C.), F30HL152505 (J.J.M.), R01HL095590 (I.Z.J.).

Abbreviations:

- ACh

acetylcholine

- Aldo

aldosterone

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- E2

estradiol

- EC

endothelial cell

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ERα

estrogen receptor alpha

- ERβ

estrogen receptor beta

- KO

knockout

- MPP

1,3-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride

- MR

mineralocorticoid receptor

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PE

phenylephrine

- PHTPP

4-[2-Phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol

- VE-Cad

Vascular endothelial cadherin

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towfighi A, Zheng L,Ovbiagele B. Sex-specific trends in midlife coronary heart disease risk and prevalence. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1762–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towfighi A, Zheng L,Ovbiagele B. Weight of the obesity epidemic: rising stroke rates among middle-aged women in the United States. Stroke. 2010;41:1371–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilmot KA, O'Flaherty M, Capewell S, Ford ES,Vaccarino V. Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Declines in the United States From 1979 Through 2011: Evidence for Stagnation in Young Adults, Especially Women. Circulation. 2015;132:997–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landmesser U,Drexler H. Endothelial function and hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jongh RT, Serne EH, RG IJ, de Vries G,Stehouwer CD. Impaired microvascular function in obesity: implications for obesity-associated microangiopathy, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Circulation. 2004;109:2529–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grizelj I, Cavka A, Bian JT, Szczurek M, Robinson A, Shinde S, Nguyen V, Braunschweig C, Wang E, Drenjancevic I,Phillips SA. Reduced flow-and acetylcholine-induced dilations in visceral compared to subcutaneous adipose arterioles in human morbid obesity. Microcirculation. 2015;22:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lind L, Berglund L, Larsson A,Sundstrom J. Endothelial function in resistance and conduit arteries and 5-year risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123:1545–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briones AM, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Callera GE, Yogi A, Burger D, He Y, Correa JW, Gagnon AM, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Gomez-Sanchez EP, et al. Adipocytes produce aldosterone through calcineurin-dependent signaling pathways: implications in diabetes mellitus-associated obesity and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2012;59:1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawarazaki W,Fujita T. The Role of Aldosterone in Obesity-Related Hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vecchiola A, Lagos CF, Carvajal CA, Baudrand R,Fardella CE. Aldosterone Production and Signaling Dysregulation in Obesity. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie D,Bollag WB. Obesity, hypertension and aldosterone: is leptin the link? J Endocrinol. 2016;230:F7–F11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley-Lewis R, Adler GK, Perlstein T, Seely EW, Hopkins PN, Williams GH,Garg R. Body mass index predicts aldosterone production in normotensive adults on a high-salt diet. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4472–4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodfriend TL, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH,Winters SJ. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance are associated with plasma aldosterone levels in women. Obes Res. 1999;7:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biwer LA, Wallingford MC,Jaffe IZ. Vascular Mineralocorticoid Receptor: Evolutionary Mediator of Wound Healing Turned Harmful by Our Modern Lifestyle. Am J Hypertens. 2019;32:123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davel AP, Anwar IJ,Jaffe IZ. The endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor: mediator of the switch from vascular health to disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26:97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coutinho P, Vega C, Pojoga LH, Rivera A, Prado GN, Yao TM, Adler G, Torres-Grajales M, Maldonado ER, Ramos-Rivera A, Williams JS, Williams G,Romero JR. Aldosterone's rapid, nongenomic effects are mediated by striatin: a modulator of aldosterone's effect on estrogen action. Endocrinology. 2014;155:2233–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwashima F, Yoshimoto T, Minami I, Sakurada M, Hirono Y,Hirata Y. Aldosterone induces superoxide generation via Rac1 activation in endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata D, Takahashi M, Sawai K, Tagami T, Usui T, Shimatsu A, Hirata Y,Naruse M. Molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect of aldosterone on endothelial NO synthase activity. Hypertension. 2006;48:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller KB, Bender SB, Hong K, Yang Y, Aronovitz M, Jaisser F, Hill MA,Jaffe IZ. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptors Differentially Contribute to Coronary and Mesenteric Vascular Function Without Modulating Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2015;66:988–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss ME, Lu Q, Iyer SL, Engelbertsen D, Marzolla V, Caprio M, Lichtman AH,Jaffe IZ. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptors Contribute to Vascular Inflammation in Atherosclerosis in a Sex-Specific Manner. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:1588–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caprio M, Newfell BG, la Sala A, Baur W, Fabbri A, Rosano G, Mendelsohn ME,Jaffe IZ. Functional mineralocorticoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and promote leukocyte adhesion. Circ Res. 2008;102:1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia G, Habibi J, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, DeMarco VG, Ramirez-Perez FI, Sun Z, Hayden MR, Meininger GA, Mueller KB, Jaffe IZ,Sowers JR. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptor Mediates Diet-Induced Aortic Stiffness in Females. Circ Res. 2016;118:935–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faulkner JL, Kennard S, Huby AC, Antonova G, Lu Q, Jaffe IZ, Patel VS, Fulton DJR,Belin de Chantemele EJ. Progesterone Predisposes Females to Obesity-Associated Leptin-Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction via Upregulating Endothelial MR (Mineralocorticoid Receptor) Expression. Hypertension. 2019;74:678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faulkner JL, Harwood DA, Kennard S, Antonova GN, Clere N,Belin de Chantemele EJ. Dietary sodium restriction sex-specifically impairs endothelial function via mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent reduction in NO bioavailability in Balb/C mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021. January 1;320(1):H211–H220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davel AP, Lu Q, Moss ME, Rao S, Anwar IJ, DuPont JJ,Jaffe IZ. Sex-Specific Mechanisms of Resistance Vessel Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Q, Pallas DC, Surks HK, Baur WE, Mendelsohn ME,Karas RH. Striatin assembles a membrane signaling complex necessary for rapid, nongenomic activation of endothelial NO synthase by estrogen receptor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17126–17131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambliss KL, Yuhanna IS, Mineo C, Liu P, German Z, Sherman TS, Mendelsohn ME, Anderson RG,Shaul PW. Estrogen receptor alpha and endothelial nitric oxide synthase are organized into a functional signaling module in caveolae. Circ Res. 2000;87:E44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karas RH, Gauer EA, Bieber HE, Baur WE,Mendelsohn ME. Growth factor activation of the estrogen receptor in vascular cells occurs via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2851–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCurley A,Jaffe IZ. Mineralocorticoid receptors in vascular function and disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;350:256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu SL, Schmuck S, Chorazcyzewski JZ, Gros R,Feldman RD. Aldosterone regulates vascular reactivity: short-term effects mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent nitric oxide synthase activation. Circulation. 2003;108:2400–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutoh A, Isshiki M,Fujita T. Aldosterone enhances ligand-stimulated nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1811–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang YY, Li C, Yao GF, Du LJ, Liu Y, Zheng XJ, Yan S, Sun JY, Liu Y, Liu MZ, et al. Deletion of Macrophage Mineralocorticoid Receptor Protects Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance Through ERalpha/HGF/Met Pathway. Diabetes. 2017;66:1535–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett Mueller K, Lu Q, Mohammad NN, Luu V, McCurley A, Williams GH, Adler GK, Karas RH,Jaffe IZ. Estrogen receptor inhibits mineralocorticoid receptor transcriptional regulatory function. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4461–4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossi GP, Belfiore A, Bernini G, Fabris B, Caridi G, Ferri C, Giacchetti G, Letizia C, Maccario M, Mannelli M, et al. Primary Aldosteronism Prevalence in hYpertension Study I. Body mass index predicts plasma aldosterone concentrations in overweight-obese primary hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2566–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarzani R, Guerra F, Mancinelli L, Buglioni A, Franchi E,Dessi-Fulgheri P. Plasma aldosterone is increased in class 2 and 3 obese essential hypertensive patients despite drug treatment. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:818–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD,Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Scopelliti F, Dell'Oro R, Fattori L, Quarti-Trevano F, Brambilla G, Schiffrin EL,Mancia G. Structural and functional alterations of subcutaneous small resistance arteries in severe human obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clemmer JS, Faulkner JL, Mullen AJ, Butler KR,Hester RL. Sex-specific responses to mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism in hypertensive African American males and females. Biol Sex Differ. 2019;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khosla N, Kalaitzidis R,Bakris GL. Predictors of hyperkalemia risk following hypertension control with aldosterone blockade. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huby AC, Antonova G, Groenendyk J, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Bollag WB, Filosa JA,Belin de Chantemele EJ. Adipocyte-Derived Hormone Leptin Is a Direct Regulator of Aldosterone Secretion, Which Promotes Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiac Fibrosis. Circulation. 2015;132:2134–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huby AC, Otvos L Jr.,Belin de Chantemele EJ. Leptin Induces Hypertension and Endothelial Dysfunction via Aldosterone-Dependent Mechanisms in Obese Female Mice. Hypertension. 2016;67:1020–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeMarco VG, Habibi J, Jia G, Aroor AR, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Sun Z, Meininger GA, Manrique C, Whaley-Connell A,Sowers JR. Low-Dose Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade Prevents Western Diet-Induced Arterial Stiffening in Female Mice. Hypertension. 2015;66:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendelsohn ME. Protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:12E–17E; discussion 17E-18E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.