Abstract

Background and Objectives

7-Hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG) is an oxidative metabolite of mitragynine, the most abundant alkaloid in the leaves of Mitragyna speciosa (otherwise known as kratom). While mitragynine is a weak partial μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist, 7-HMG is a potent and full MOR agonist. It is produced from mitragynine by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A, a drug-metabolizing CYP isoform predominate in the liver that is also highly expressed in the intestine. Given the opioidergic potency of 7-HMG, a single oral dose pharmacokinetic and safety study of 7-HMG was performed in beagle dogs.

Methods

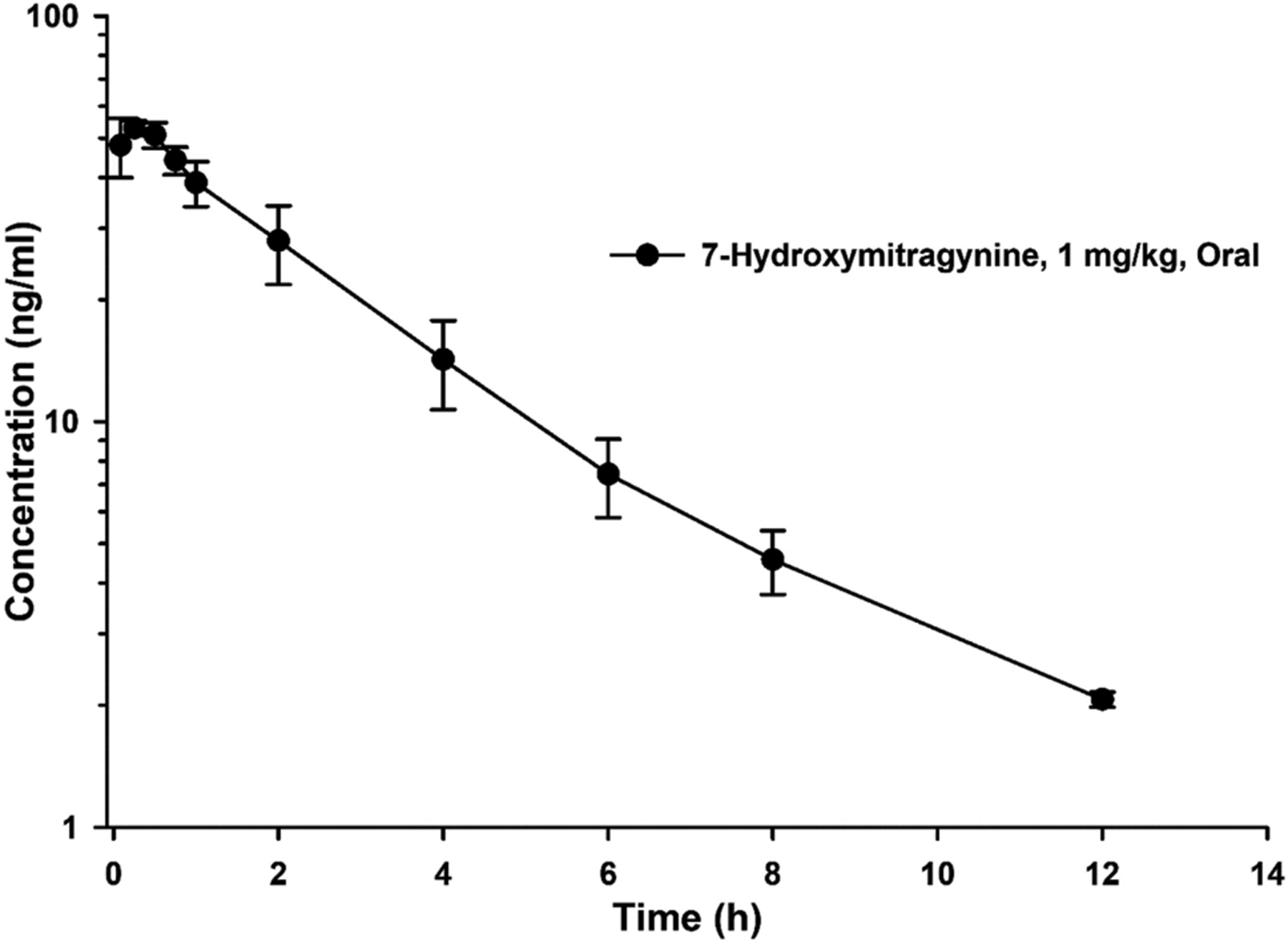

Following a single oral dose (1 mg/kg) of 7-HMG, plasma samples were obtained from healthy female beagle dogs. Concentrations of 7-HMG were determined using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with a tandem mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS/MS). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a model-independent non-compartmental analysis of plasma concentration-time data.

Results

Absorption of 7-HMG was rapid, with a peak plasma concentration (Cmax, 56.4 ± 1.6 ng/mL) observed within 15 min post-dose. In contrast, 7-HMG elimination was slow, exhibiting a mono-exponential distribution and mean elimination half-life of 3.6 ± 0.5 h. Oral dosing of 1 mg/kg 7-HMG was well-tolerated with no observed adverse events or significant changes to clinical laboratory tests.

Conclusions

These results provide the first pharmacokinetic and safety data for 7-HMG in the dog, and therefore contribute to the understanding of the putative pharmacological role of 7-HMG resulting from an oral delivery of mitragynine from kratom.

1. Introduction

Opioids are the most widely prescribed analgesics [1, 2]. The increased use and misuse of opioids over the last few decades has become a major public health concern [3]. There has been increased scrutiny of medicinal plants as alternatives to opium and its constituents (such as morphine) for the relief of chronic pain and self-treatment of opioid use disorder. Mitragyna speciosa (Korth.), also known as kratom, is a tree native to Southeast Asia that is used to alleviate pain, stimulate mood, and lessen symptoms of opioid withdrawal [4–6].

The most abundant alkaloid present in dried kratom leaves is mitragynine, which typically represents ~1% of the overall weight of dry leaves and is typically found in ranges of 0.7–38.7% w/w of commercial kratom products in the United States formulated as dried leaves, alcoholic extracts, and alkaloid fractions [7]. Because of its relatively high abundance, mitragynine plays an important role in the psychopharmacological activity of kratom [8]. In contrast, the amount of 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG) is much lower and represents <0.01% w/w of fresh Malaysian kratom samples, although some reports have demonstrated ~2% w/w in the kratom products available in the United States [9]. Although 7-HMG is present in much smaller amounts than mitragynine in kratom products, it has a much greater affinity for the MOR than mitragynine (Ki= 7.2 ± 0.9 nM vs 161 ± 10 nM, respectively), and is considerably more potent at activating μ-opioid receptor (MOR) G-protein signaling [10–13]. It is also an oxidative metabolite of mitragynine that is formed following the consumption of kratom [13–15]. Cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 3A enzymes play an important role in the metabolic conversion of mitragynine to 7-HMG [16]. CYP 3A enzymes are highly expressed in the liver and intestine, and CYP 3A mediated metabolic conversion of mitragynine to 7-HMG in enterocytes leads to a higher exposure of 7-HMG when mitragynine is administered orally versus intravenously [14]. Following an oral mitragynine dose in dogs, the area under the curve of 7-HMG represented 12.6% of that of mitragynine [14], suggesting it may considerably contribute to the MOR agonism associated with mitragynine administration. This study therefore seeks to examine the pharmacokinetics, and in particular the elimination rate of 7-HMG by administering it as a single oral dose to healthy female dogs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

Mitragynine (purity ≥ 98%) was isolated and purified from a commercially available organic alkaloid rich extract of kratom, and 7-HMG (purity ≥ 98%) was semi-synthesized from mitragynine. Both mitragynine and 7-HMG were characterized for chemical structure, and purity was determined as reported in our earlier published papers [14]. Heparin, protease inhibitor cocktail, LC-MS grade acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid, and water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Verapamil (purity ≥ 98%) was obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Heparinized pooled dog plasma was procured from Innovative Research, Inc (Novi, MI, USA).

2.2. Quantitative analysis of 7-HMG in dog plasma

Our earlier reported, validated bioanalytical method for the simultaneous quantification of mitragynine and 7-HMG was utilized for the analysis of dog plasma samples with the only modification being the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail along with heparin to the sample collection tubes to reduce the possible metabolism of 7-HMG in dog plasma [14, 17]. During bench-top stability studies, 7-HMG showed a trend of instability but within the FDA limits (±15%, Supporting Table 1). Addition of protease inhibitor cocktail was used to slow down the metabolism process in plasma after blood sampling. In brief, a Waters Acquity UPLC I-Class Plus and Xevo TQ-S Micro triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) were used for the quantitative analysis of 7-HMG in dog plasma. Mass spectrometric detection was achieved using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode to monitor precursor to product ion (m/z) transitions m/z 415.19 > 175.14 and 455.27 > 150.10 for 7-HMG and internal standard (verapamil, IS), respectively. Source parameters; namely, cone gas flow, desolvation gas flow, desolvation temperature, source temperature, and capillary voltage were set at 50 L/h, 900 L/h, 450°C, 150°C, and 0.5 V, respectively. Chromatographic separations were achieved on a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) preceded by a Van Guard pre-column (2.1 × 5.0 mm, 1.7 μm) using a gradient elution (0.35 mL/min) of 0.1% v/v formic acid in water (pump A) and acetonitrile (pump B). Gradient elution began with pump A supplying 80% until 0.5 min, and composition of A in mobile phase linearly decreased to 68 and 62% at 2.2 and 3.5 min, respectively. At 3.6 min composition of A was returned to 80% and maintained at 80% until 5.5 min to re-equilibrate the column. Methanol containing 0.05% v/v formic acid and the IS (10 ng/mL) was used as a quenching solution for plasma sample cleanup. The linearity of the method was 1–200 ng/mL, and test samples were analyzed along with freshly prepared calibration and quality control standards.

2.3. Pharmacokinetics and safety of 7-HMG in dogs

A single oral dose (1 mg/kg, N=3) pharmacokinetic study of 7-HMG was performed in purpose-bred research female beagles, with a mean age of 2.5 years, weighing 8.8–10.3 kg. Dogs were housed in a temperature and light-controlled environment. All dogs were fasted overnight and were fed 2 h post-dose. Prior to the start of the study, a central intravenous line was placed in the right or left jugular vein of each dog. Heparinized saline was used to maintain the patency of the canula. Complete blood count (CBC) and serum biochemical panels were performed prior to and at the end of the study. Hematologic abnormalities were graded in accordance with the VCOG Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (VCOG-CTCAE) v 1.0.14 [18]. Clinical monitoring of vital signs (mentation, temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate) began 5 min after the administration of 7-HMG. General health was assessed throughout the course of the study period, including food and water consumption, elimination, activity level, and subjective clinical observations of attitude, level of consciousness, and hydration. Formulation was prepared fresh by dissolving 7-HMG in water and this solution was analyzed for 7-HMG content. For the oral pharmacokinetic study, blood samples (1 mL) were collected from the central line at pre-dose, and 0.083, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 hr post-dose. Blood samples were collected in labeled protease inhibitor cocktail and heparin-coated tubes, and plasma was harvested after centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The collected plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis using UPLC-MS/MS method. Plasma concentration-time data were subjected to non-compartmental analysis to calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters for 7-HMG using Phoenix 6.4® (Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA).

3. Results

Following the oral dose of 7-HMG (1 mg/kg), female dogs were observed for behavioral changes and adverse events. There were no major behavioral changes or adverse events noted. No clinically significant changes in vital signs, physical examinations, or clinical laboratory tests were observed. Mean CBCs obtained following the study remained within normal reference ranges and were similar to baseline values (Table 1). Mean biochemical parameters obtained after the completion of the study were also largely within reference ranges and similar to baseline values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean complete blood count parameters before and after oral (1 mg/kg) administration of 7-hydroxymitragynine.

| Parameter (Reference Range) | Orala | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-dose | Post-dose | |

| Complete Blood Count | ||

| WBC (5.0–13.0 K/μL) | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 8.6 ± 0.9 |

| RBC (5.7–8.3 M/μL) | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.2 |

| Hct (40–56 %) | 47.6 ± 0.8 | 52.5 ± 1.1 |

| MCV (64–74 fL) | 67.3 ± 0.5 | 69.2 ± 0.6 |

| Platelets 134–396 K/μL) | 365.0 ± 66.5 | 258.7 ± 37.4 |

| Neutrophils (2.7–8.9 K/μL) | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 1.0 |

| Lymphocytes (0.9–3.4 K/μL) | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| Monocytes (0.1–0.8 K/μL) | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Eosinophils (0.1–1.3 K/μL) | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Basophils (0–0.1 K/mL) | 40.0 ± 20.0 | 50.0 ± 10.0 |

| Biochemistry | ||

| ALP (7–117 U/L) | 30.3 ± 6.0 | 31.3 ± 4.0 |

| ALB (2.62–3.91 g/dL) | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| ALT (23–93 U/L) | 28.7 ± 7.2 | 29.0 ± 3.0 |

| AST (16–53 U/L) | 28.7 ± 5.5 | 26.0 ± 3.0 |

| Chol (102–340 mg/dL) | 218.0 ± 52.2 | 228.0 ± 47.8 |

| Glob (1.8–4.0 g/dL) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| Glucose (78–124 mg/dL) | 52.7 ± 10.7 | 94.3 ± 6.7 |

| Magnesium (1.7–2.4 mg/dL) | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| Phosphorus (2.2–4.8 mg/dL) | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.8 |

| Total Protein (5.0–7.4 g/dL) | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0 |

| Calcium (8.7–10.4 mg/dL) | 9.9 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.1 |

| Sodium (141.9–150.6 mEq/L) | 148.9 ± 2.5 | 148.7 ± 1.1 |

| Potassium (3.8–5.0 mEq/L) | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.1 |

| T Bilirubin (0.1–0.4 mg/dL) | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0 |

| Chloride (107.8–117.1 mEq/L) | 111.5 ± 2.6 | 110.4 ± 0.3 |

| Creatinine (0.6–1.5 mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| BUN (7–27 mg/dL) | 31.0 ± 3.6 | 24.0 ± 1.0 |

N = 3, values are mean ± SEM

After oral dosing of 7-HMG, absorption occurred rapidly and the plasma concentrations remained quantifiable (> 1 ng/mL) up to 12 h post-dose (Figure 1). The peak plasma concentration (Cmax, 56.4 ± 1.6 ng/mL) was observed at 0.14 ± 0.1 h (Tmax) post-dose (Table 2). Due to the insufficient data points available in absorption phase, we were unable to fit a pharmacokinetic model using compartmental approach. To overcome the errors associated with compartmental modeling, concentration-time data was subjected to non-compartmental analysis. Following the oral dose, elimination half-life (T1/2) of 7-HMG (3.6 ± 0.5 h) was 2.4-fold lower than that of mitragynine (8.7 ± 0.2 h, [14]). The clearance (Cl/F) and volume of distribution (Vd/F) for 7-HMG were 4.4 ± 0.6 L/h/Kg and 23.8 ± 6.7 L/Kg, respectively. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) of 7-HMG following a single oral dose of 7-HMG was compared to the AUC of 7-HMG formed after a single oral dose of mitragynine. A 2.5-fold lower dose-normalized systemic exposure of 7-HMG (AUC/Dose) was observed compared to mitragynine (178.6 ± 25.9 vs 443.3 ± 33.4 h·kg·ng/mL/mg, respectively [14]). The exposure of 7-HMG after mitragynine dosing due to metabolism corresponds to a 0.24 mg/kg dose of 7-HMG indicating a 23.1% conversion of mitragynine to 7-HMG in beagle dogs [14].

Fig. 1.

Mean plasma concentration-time profile of 7-hydroxymitragynine after single oral dose in female beagle dogs (N = 3). Error represent SEM

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of 7-hydroxymitragynine after oral (1 mg/kg) dose in female beagle dogsa

| Parameter | Oral |

|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 56.4 ± 1.6 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.14 ± 0.1 |

| AUC0-inf (h·ng/mL) | 178.6 ± 25.9 |

| Cl/F (L/h/Kg) | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| Vd/F (L/Kg) | 23.8 ± 6.7 |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

N = 3, values are mean ± SEM

Abbreviations: AUC0-inf = area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to infinity, Cl= clearance, Cmax = plasma peak concentration, T1/2 = elimination half-life, Vd = volume of distribution, Tmax = time to reach Cmax, F = bioavailability fraction

4. Discussion

The dose of 7-HMG used in this study was well tolerated with no adverse events or major abnormalities in clinical parameters. Mild hypoglycemia that was noted in the pre-dose samples is most likely due to an artifact resulting from a delay in sample processing, and less likely due to fasting. Taking into consideration the pharmacokinetic data of mitragynine in dogs reported previously by our group using similar experimental conditions [14], we adjusted our protocol and included earlier time points (5, 15, and 30 min) after dosing; however, the Cmax occurred very rapidly (i.e., within two blood withdrawals) and we were unable to capture the absorption phase. The dose-normalized peak plasma concentration for 7-HMG (Cmax/Dose, 56.4 ± 1.6 ng/mL) is equivalent to mitragynine (Cmax/Dose, 55.6 ± 9.5 ng/mL) in dogs but that study showed multiple peak maxima in mitragynine concentrations, while, 7-HMG showed a clean mono-exponential concentration-time profile with a single Cmax [14]. 7-HMG showed longer elimination half-life after oral dose of mitragynine than that of after 7-HMG oral dosing, possibly due to the formation limited pharmacokinetics of 7-HMG after mitragynine dosing. Formation of 7-HMG from mitragynine in kratom could result in significant systemic exposure of this potent opioid due to conditions such as prolonged intestinal exposure.

A comparatively higher polar surface area and lower log P of 7-HMG compared to mitragynine may have limited its distribution to the peripheral compartments which, in turn, may have led to the mono-exponential distribution. In contrast, mitragynine exhibited a multiexponential profile after Cmax. Manda et al. (2014) reported that 7-hydroxymitragynine metabolized about 45% to mitragynine in human liver microsomes but we did not observe any conversion of 7-hydroxymitragynine to mitragynine in dogs [22]. Dogs were chosen as a preclinical species for pharmacokinetic testing due to their well-understood physiology and similarities to humans [19]. Pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in female dogs, but gender-related variations in 7-HMG pharmacokinetics are not anticipated due to identical CYP3A/CYP3A12 expression in male and female dogs [20, 21]. Derived pharmacokinetic parameters of 7-HMG from this study can be scaled allometrically along with the pharmacokinetic parameters of mitragynine to predict the dose of mitragynine while designing the first in human study.

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed that 7-HMG has rapid absorption and a moderate elimination half-life following an oral dose in healthy beagle dogs. Our data also suggest that the amount of 7-HMG formed by the metabolism of 1 mg mitragynine (oral dose) is equivalent to 0.24 mg of orally dosed 7-HMG. Considering the comparatively limited capability of 7-HMG to cross the blood-brain barrier compared to mitragynine, the metabolism of mitragynine within the brain is potentially required for the 7-HMG mediated central activation of MORs. As 7-HMG is 10–20 fold more potent at the MOR than mitragynine, the 1 part per 4 parts formation from the dosed mitragynine (or kratom) suggests that some of the peripheral MOR activation following the oral ingestion of kratom may be attributable to 7-HMG. The pharmacokinetics of 7-HMG detailed in this study will contribute to our understanding of the overall pharmacologic activity of mitragynine and by extension, kratom.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Oral dose of 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG), an active metabolite of mitragynine, was well tolerated in beagle dogs

7-HMG showed fast absorption, and peak plasma concentration was observed within 15 min post-dose

Exposure of 7-HMG after mitragynine oral dosing is equivalent to a 0.24 mg/kg dose of 7-HMG

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to thank Ms. Paige Maxwell for providing technical support.

Funding

This study was financially supported by UG3 DA048353 and R01 DA047855 grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award number UL1TR001427. Dr. Hampson was substantially involved in UG3 DA048353, consistent with his role as Scientific Officer. He had no substantial involvement in the other cited grants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number: 201910731, dated July 11, 2019) at the University of Florida.

References

- 1.Makary MA, Overton HN, Wang P. Overprescribing is major contributor to opioid crisis. BMJ. 2017:359:j4792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rummans TA, Burton MC, Dawson NL. How good intentions contributed to bad outcomes: the opioid crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(3):344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vadivelu N, Kai AM, Kodumudi V, Sramcik J, Kaye AD. The opioid crisis: a comprehensive overview. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22(3):16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh D, Narayanan S, Vicknasingam B. Traditional and non-traditional uses of Mitragynine (Kratom): A survey of the literature. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126:41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward J, Rosenbaum C, Hernon C, McCurdy CR, Boyer EW. Herbal medicines for the management of opioid addiction. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(12):999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer EW, Babu KM, Adkins JE, McCurdy CR, Halpern JH. Self-treatment of opioid withdrawal using kratom (Mitragynia speciosa korth). Addiction. 2008;103(6):1048–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma A, Kamble SH, León F, Chear NJY, King TI, Berthold EC, et al. Simultaneous quantification of ten key Kratom alkaloids in Mitragyna speciosa leaf extracts and commercial products by ultra-performance liquid chromatography− tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Test Anal. 2019;11(8):1162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harun N, Hassan Z, Navaratnam V, Mansor SM, Shoaib M. Discriminative stimulus properties of mitragynine (kratom) in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2015;232(13):2227–38. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3866-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lydecker AG, Sharma A, McCurdy CR, Avery BA, Babu KM, Boyer EW. Suspected Adulteration of Commercial Kratom Products with 7-Hydroxymitragynine. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(4):341–9. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto K, Horie S, Ishikawa H, Takayama H, Aimi N, Ponglux D, et al. Antinociceptive effect of 7-hydroxymitragynine in mice: Discovery of an orally active opioid analgesic from the Thai medicinal herb Mitragyna speciosa. Life Sci. 2004;74(17):2143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruegel AC, Gassaway MM, Kapoor A, Váradi A, Majumdar S, Filizola M, et al. Synthetic and receptor signaling explorations of the Mitragyna alkaloids: mitragynine as an atypical molecular framework for opioid receptor modulators. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(21):6754–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeng S, Kamble SH, Reeves ME, Restrepo LF, Patel A, Behnke M, et al. Investigation of the adrenergic and opioid binding affinities, metabolic stability, plasma protein binding properties, and functional effects of selected indole-based kratom alkaloids. J Med Chem. 2019;63(1):433–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiranita T, Sharma A, Oyola FL, Obeng S, Reeves ME, Restrepo LF, et al. Potential Contribution of 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a Metabolite of the Primary Kratom (Mitragyna Speciosa) Alkaloid Mitragynine, to the μ-Opioid Activity of Mitragynine in Rats. The FASEB Journal. 2020;34(S1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maxwell EA, King TI, Kamble SH, Raju KSR, Berthold EC, León F, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of mitragynine in beagle dogs. Planta Med. 2020;86(17):1278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruegel AC, Uprety R, Grinnell SG, Langreck C, Pekarskaya EA, Le Rouzic V, et al. 7-Hydroxymitragynine is an active metabolite of mitragynine and a key mediator of its analgesic effects. ACS Central Sci. 2019;5(6):992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamble SH, Sharma A, King TI, León F, McCurdy CR, Avery BA. Metabolite profiling and identification of enzymes responsible for the metabolism of mitragynine, the major alkaloid of Mitragyna speciosa (kratom). Xenobiotica. 2019;49(11):1279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamble S, León F, King TI, Berthold EC, Lopera-Londoño C, Siva Rama Raju K, et al. Metabolism of a kratom alkaloid metabolite in human plasma increases its opioid potency and efficacy. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;3(6):1063–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veterinary cooperative oncology group - common terminology criteria for adverse events (VCOG-CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.1. Vet Comp Oncol. 2016;14(4):417–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibbitts J Issues related to the use of canines in toxicologic pathology—issues with pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Toxicol Pathol. 2003;31(suppl):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez SE, Shi J, Zhu H-J, Jimenez TEP, Zhu Z. Absolute Quantitation of Drug-Metabolizing Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Accessory Proteins in Dog Liver Microsomes Using Label-Free Standard-Free Analysis Reveals Interbreed Variability. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47(11):1314–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishibe Y, Wakabayashi M, Harauchi T, Ohno K. Characterization of cytochrome P450 (CYP3A12) induction by rifampicin in dog liver. Xenobiotica. 1998;28(6):549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manda VK, Avula B, Ali Z, Khan IA, Walker LA, Khan SI. Evaluation of in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of mitragynine, 7-hydroxymitragynine, and mitraphylline. Planta Med. 2014;80(7):568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.