Abstract

Nanoformulations of therapeutic drugs are transforming our ability to effectively deliver and treat a myriad of conditions. Often, however, they are complex to produce and exhibit low drug loading, except for nanoparticles formed via co-assembly of drugs and small molecular dyes, which display drug loading capacities of up to 95%. There is currently no understanding of which of the millions of small molecule combinations can result in the formation of these nanoparticles. Here, we report the integration of machine learning with high-throughput experimentation to enable the rapid and large-scale identification of such nanoformulations. We identified 100 self-assembling drug nanoparticles from 2.1 million pairings, each including one of 788 candidate drugs and one of 2686 approved excipients. We further characterized two nanoparticles, sorafenib-glycyrrhizin and terbinafine-taurocholic acid, both ex vivo and in vivo. We anticipate that our platform can accelerate the development of safer and more efficacious nanoformulations with high drug loading capacities for a wide range of therapeutics.

Small molecular therapeutics are often poorly soluble in water1. This can cause formation of micron-sized colloidal aggregates2,3, decreasing bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy3,4. Solid drug nanoparticles stabilized by lipids and/or polymers can alleviate these problems5,6, but their low drug loading is an important limitation7–9. Recently, it has been shown that co-formulating certain cancer drugs with specific small molecular dyes such as Congo Red10 or IR78311 can form stable nanoparticles with ultrahigh drug loading. We propose that formulating drug nanoparticles by excipient-aided co-assembly is not limited to chemotherapeutics and chemical dyes but transferable to a wider range of drugs and excipients. It is currently not understood which of the millions of possible drug-excipient combinations lead to nanoparticle formation with the desired properties.

Here, we integrated molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and machine learning with a high-throughput experimental co-aggregation platform to identify drug-excipient combinations that form stable, self-assembled solid drug nanoparticles based on solvent exchange without the need for chemical synthesis (Figure 1a). We identified a total of 100 novel co-aggregated solid drug nanoparticles from 2.1 million possible pairings of 788 candidate drugs with one of 2686 excipients. We used FDA-approved drugs and excipients to potentially accelerate the translation of these nanoformulations9,12; with potential applications including cancer therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, asthma therapy, and anti-viral, anti-malarial, and anti-fungal drug delivery. We performed ex vivo and in vivo proof-of-concept studies on two novel co-aggregated nanoparticles. Both validations highlight the ability of our platform to facilitate the generation of nanoparticles with high drug loading and improved bioavailability.

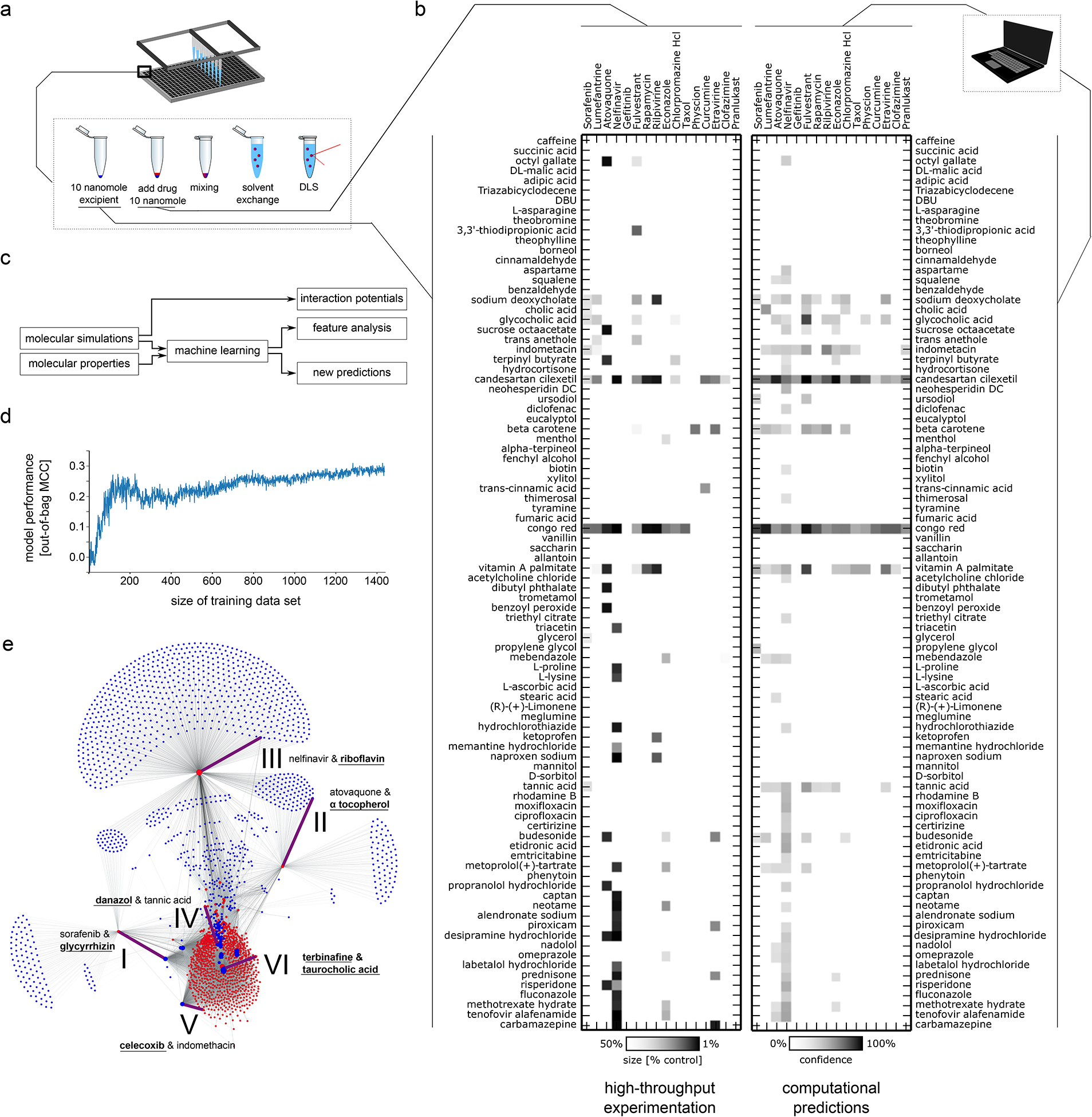

Figure 1: High-throughput screening of solid drug nanoparticles and machine learning model development.

a Schematic of high-throughput experimental workflow to create nanoparticles using nanoprecipitation technique and rapid assessment using dynamic light scattering (DLS). b Left: High-throughput testing of all 1440 combinations of 16 drugs and 90 excipients (inactive ingredients, generally-recognized-as-safe food and drug additives, and other FDA-approved approved compounds). Colour gradient indicates size reduction of nanoparticle compared to the unformulated drug, where white corresponds to less than a 50% reduction in size and black correspond to a 90% reduction in size with linear interpolation (cf colour bar at bottom). Right: Machine learning-based assessment of nanoparticle-forming potential of drug-excipient pairs according to their chemical structures, physicochemical properties, and pairwise interaction potential determined from short molecular dynamic simulations. Gradient indicates predictive confidence from ten-fold cross validation (white 0% confidence, black 100% confidence, linear interpolation, cf colour bar at bottom). We found good agreement between the computational assessments (right) and the real-world experimentation (left), with 91% of the experiments correctly predicted. c Schematic explaining relationship of molecular dynamic simulations and machine learning. The molecular dynamic simulations of drug-excipient systems are computationally analysed to quantify non-covalent interaction potentials. These potentials serve as input for our machine learning model. The machine learning model uses both these interaction potentials and the molecular properties of drugs and excipients to predict which drug-excipient pairs will most likely lead to nanoparticle formation. Furthermore, the analysis of the predictive architecture of the machine learning model enables us to determine the most important variables that govern co-aggregation prediction (Supplementary Table 4). In a separate analysis, molecular dynamics trajectories were analysed to identify the most relevant non-covalent interactions for different drug-excipient pairs (Supplementary Table 8). d Performance analysis of machine learning model trained on different training dataset sizes. Shown is the mean performance of 20 independent models trained on random data subsets. e Using the developed computational prediction model, we predicted 2.1 million pairs constituting all exhaustive combinations of 788 drugs each paired with one of 2686 excipients. The machine learning model predicted that a majority of the drugs and excipients would not co-aggregate, resulting in colloidal self-aggregation of the drug and precipitation. For 38,464 combinations (1.8%), the machine learning model predicted a potential interaction between the drug and the excipient, leading to a stabilized, co-assembled nanoparticle formation. Some excipients (blue dots) are predicted to enable creation of nanoparticles with many different drugs (red dots) while other excipients were predicted to be able to create nanoparticles with only a single drug. Node size corresponds to the number of predicted excipients/drugs enabling formation of nanoparticles with this compound. Combinations further characterized in this paper are highlighted with purple edges, are numbered (cf. Figure 2) and labelled with the corresponding drug and excipient constituting this pair. The novel component that was not previously used in the screen is highlighted in bold and underlined.

High-throughput platform for co-aggregate identification

We selected drugs that self-aggregate into colloidal macrostructures as candidates for our platform, since self-aggregating molecules are more prone to co-aggregation10,11. A random forest model can identify self-aggregators with precision of 77±2% in retrospective cross-validation experiments (Supplementary Table 1)3,13. This model identified 788 approved drugs as likely to self-aggregate and therefore as candidate material for our nanoparticle formulation platform (Supplementary Note 1). We selected 20 compounds for screening to span a variety of indications while ensuring chemical diversity (Supplementary Figure 1). We used dynamic light scattering (DLS) to confirm the self-aggregation propensity of these candidates and found that four of the selected drugs did not show detectable self-aggregates and were discarded (Supplementary Table 2). The other 16 drugs formed micron-sized self-aggregates and represent a diverse set of candidate drugs for co-aggregation.

A set of 90 excipients were selected from the FDA list of inactive ingredients12, the FDA list of “generally recognized as safe” ingredients14 and other FDA-approved small molecules15. Selection criteria included chemical diversity (Supplementary Figure 1) and commercial availability. With the exception of Congo red, which served as a positive control10, none of these materials had been used in co-aggregating nanoparticles. However, our material selection did specifically select excipients with precedence for biomedical applications to facilitate in vivo and human testing and provide a pathway towards human translation.

We followed established protocols for nanoprecipitation to generate nanoparticles from our pairs of drugs and excipients (Supplementary Note 2)6,7,10. To automate this process and improve reproducibility, we coupled a liquid handling deck (Tecan Freedom Evo 150) to a high-throughput DLS (Wyatt Dyna Pro Plate Reader). This enabled us to rapidly screen 384-well plates of nanoformulations using as little as 1 nanomole of drug or excipient for each experimental replicate. In total, we generated and experimentally tested 1440 formulations for their ability to form co-aggregating nanoparticles.

To determine whether excipients would prevent colloidal self-aggregation of the drug they were paired with, we compared the size of the drug-excipient co-aggregates to the size of the colloidal self-aggregates formed by the drug alone. We considered a size reduction to be meaningful only if the co-aggregates were less than half as large as the self-aggregates formed by the drug alone (Supplementary Figure 2). Out of 1440 measured combinations, 94 (6.5%) showed the targeted size reduction (Figure 1b). While some excipients appeared to facilitate co-aggregation more than others, the data overall suggests a complex molecular recognition mechanism with distinct behaviours emerging across the different pairings.

Machine learning for nanoparticle design

We hypothesized that a machine learning model trained on these co-aggregation patterns would enable us to extrapolate from this data and rapidly identify additional drug-excipient pairs without the need for laborious high-throughput screening. We described every drug-excipient pair using the chemical substructures and physicochemical properties of both the drug and excipient; following standard protocols in molecular machine learning16,17. Additionally, we performed short MD simulations to quantify non-covalent interaction potentials between drugs and excipients based on summary statistics on inter-molecular distances, potential energies and kinetic energies. Together, these computations generate a 4515-dimensional descriptor per drug-excipient pair. 1440 data points collected from the high-throughput co-aggregation experimentation, as described above, were used as the training set (Figure 1c).

We employed a random forest machine learning model given its robust performance in molecular machine learning and its inherent ability to select relevant features. Our model exhibited promising performance in retrospective evaluations based on ten-fold cross and “leave one drug out” validations (Supplementary Table 3)18, indicating that our model accurately captures the co-aggregation relationships and is able to prioritize suitable excipients for a novel drug. A model which included all parameter types was most accurate in predicting co-aggregation outcomes (Supplementary Table 3), although feature importance analysis (Supplementary Figure 3) indicated that simulation-derived quantifications of molecular interactions and the excipients refractivity19 are most informative to predict co-aggregation (Supplementary Table 4; Supplementary Note 3). Parameter ablation experiments confirmed the relevance of the most important features for our machine learning model (Supplementary Figure 4). The random forest model outperformed other established machine learning approaches on our data (Supplementary Table 5) and adversarial controls indicated that our model identified meaningful patterns (Supplementary Table 6)20. Finally, out-of-bag performance of models trained on random subsets of the training data revealed that the model performance was converging (Figure 1d), indicating that additional screening rounds would most likely not lead to strong improvements in model quality; advocating for more directed acquisition of additional data through predictive modelling.

To this end, we modelled the complete co-aggregation landscape of all 788 aggregating drugs combined with any of the 2686 available excipients using our machine learning model. In total, 2.1 million formulations were computationally assessed for their ability to form self-assembling co-aggregated nanoparticles. Given the infeasibility of running MD simulations for all 2.1 million combinations, we applied a machine learning model trained exclusively on chemical and physicochemical properties. This modified model exhibited slightly lower retrospective performance (Supplementary Table 3) but higher computational tractability. The machine learning model predicted a total of 38,464 combinations (1.8% of all possible pairs) to co-aggregate into nanoparticles (Figure 1e).

In silico designed nanoparticles improve drug dispersion

We selected six of the co-aggregation predictions for experimental testing, specifically selecting novel excipients (Figure2, I–III), new drugs (Figure2, IV & V) or combinations of a novel drug and excipient (Figure2, VI). We used DLS to measure the size of the colloidal self-aggregates of the selected drugs. All six drugs self-aggregated into micron-sized, polydisperse structures (Supplementary Table 7). A large number of automatically flagged acquisitions for these drug aggregates suggested interference with the measurement through precipitation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed a range of complex microstructures (Figure 2a). When mixing the drugs with the excipients, DLS indicated the formation of monodisperse, nano-sized co-aggregates (Supplementary Table 7). Using TEM, we imaged the drug-excipient samples and confirmed that co-aggregation of the selected drugs and excipients formed homogeneous populations of nanoparticles (Figure 2b). None of the co-aggregation acquisitions were flagged, suggesting stable nanoparticle dispersions (Supplementary Table 7).

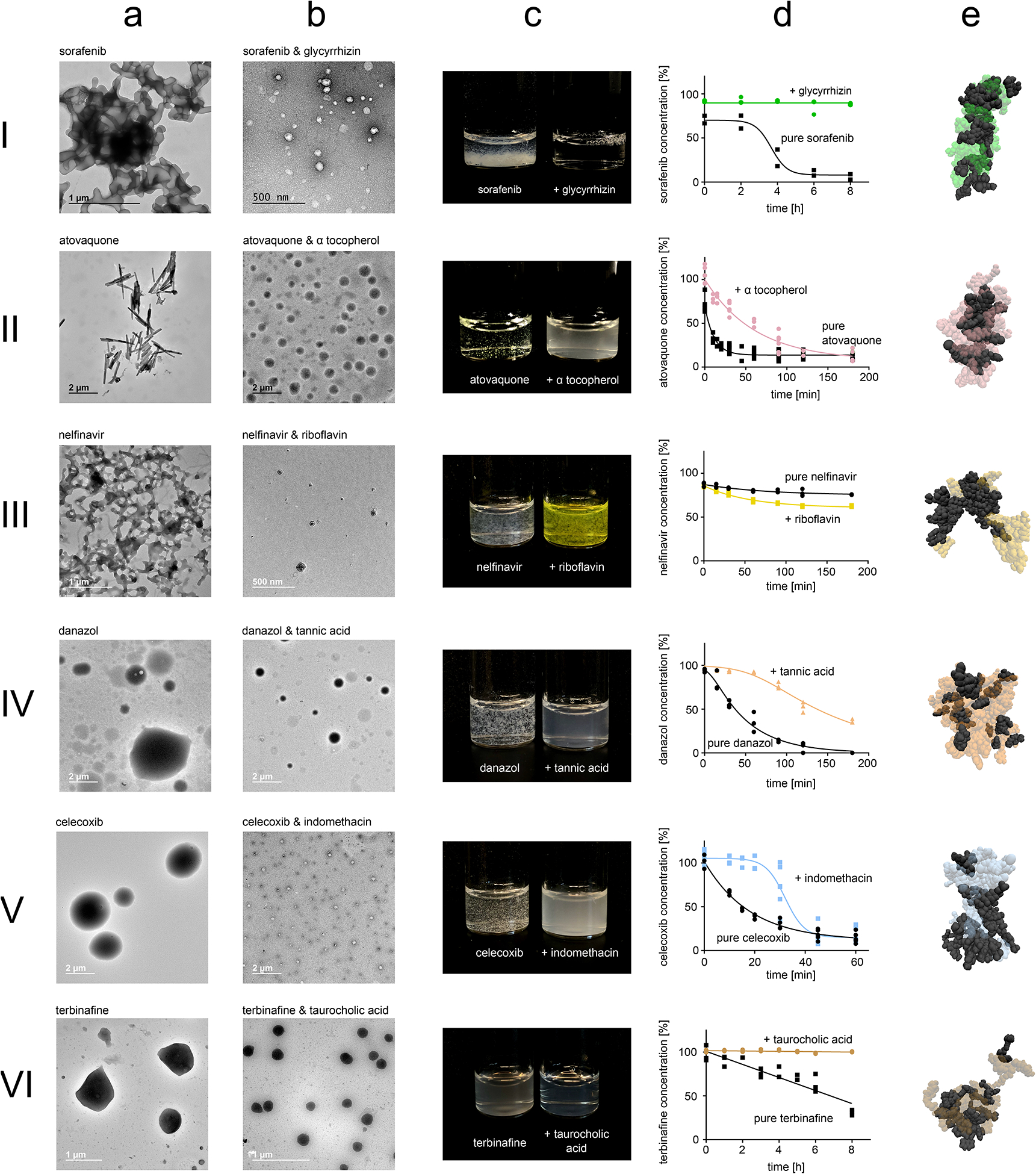

Figure 2: Computationally prioritized combinations of drugs and excipients form nanoparticles.

Numbering corresponds to edges highlighted in Figure 1e. Nanoparticle formation was primarily evaluated using dynamic light scattering (Supplementary Table 5). This data was further validated using TEM images of micron-sized aggregates formed by the pure drug (a) and TEM images of the nanoparticles formed by co-aggregating the drugs and excipients (b). Photos show dispersion of the nanoparticles compared to unformulated drug during concentration escalation experiments (c). Dispersion stability was quantified by analysing time-concentration curves according to OECD guidelines (d). Short molecular dynamic simulations map non-covalent interaction potential between drugs and excipients (e). In the MD visualizations, drugs are visualized through black Van der Waals-spheres, while excipients are visualized through transparent and coloured Van der Waals-spheres. For a, b, and c representative images are shown from ten acquisitions generated through two independent experiments, all images reproduced the here depicted behaviour.

To further assess the stability of nanoparticle dispersions, we escalated nanoparticle concentrations by increasing drug and excipient concentration while maintaining drug:excipient ratios during production. With the exception of nelfinavir-riboflavin, all of the nanoparticular co-aggregates exhibited clear or milky dispersions at high drug concentrations up to 1 mM; drugs without excipients precipitated rapidly (Figure 2c). Since visibility of precipitation is a subjective measure, we followed established protocols from the OECD to quantitatively assess nanoparticle dispersion stability (Supplementary Figure 5)21. The nanoparticles formed stable dispersion as indicated by maintaining high drug concentrations for longer time periods compared to the drugs without the excipients, with the exception of nelfinavir (Figure 2d). The excipients remained highly soluble throughout the duration of the experiment (Supplementary Figure 6).

To investigate the non-covalent forces that govern co-aggregation, we conducted additional MD simulations using our established parameters for larger systems of 20 drug and 20 excipient molecules (Figure 2E). Every drug-excipient system interacted with distinct patterns of specific non-covalent forces, suggesting that co-aggregation of our nanoparticles is governed by complex molecular recognition mechanisms and through various non-covalent interactions (Supplementary Table 8).

Terbinafine particles for antifungal applications

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disorder observed in clinical practice22. Terbinafine is an anti-fungal drug used to treat cutaneous mycoses, including onychomycosis. It can be given orally or topically; however, its effectiveness is limited in oral applications due to systemic toxicity and in topical applications due to low tissue penetration23. We hypothesized that our terbinafine-taurocholic acid nanoparticles could increase skin penetration of terbinafine, thereby increasing topical efficiency.

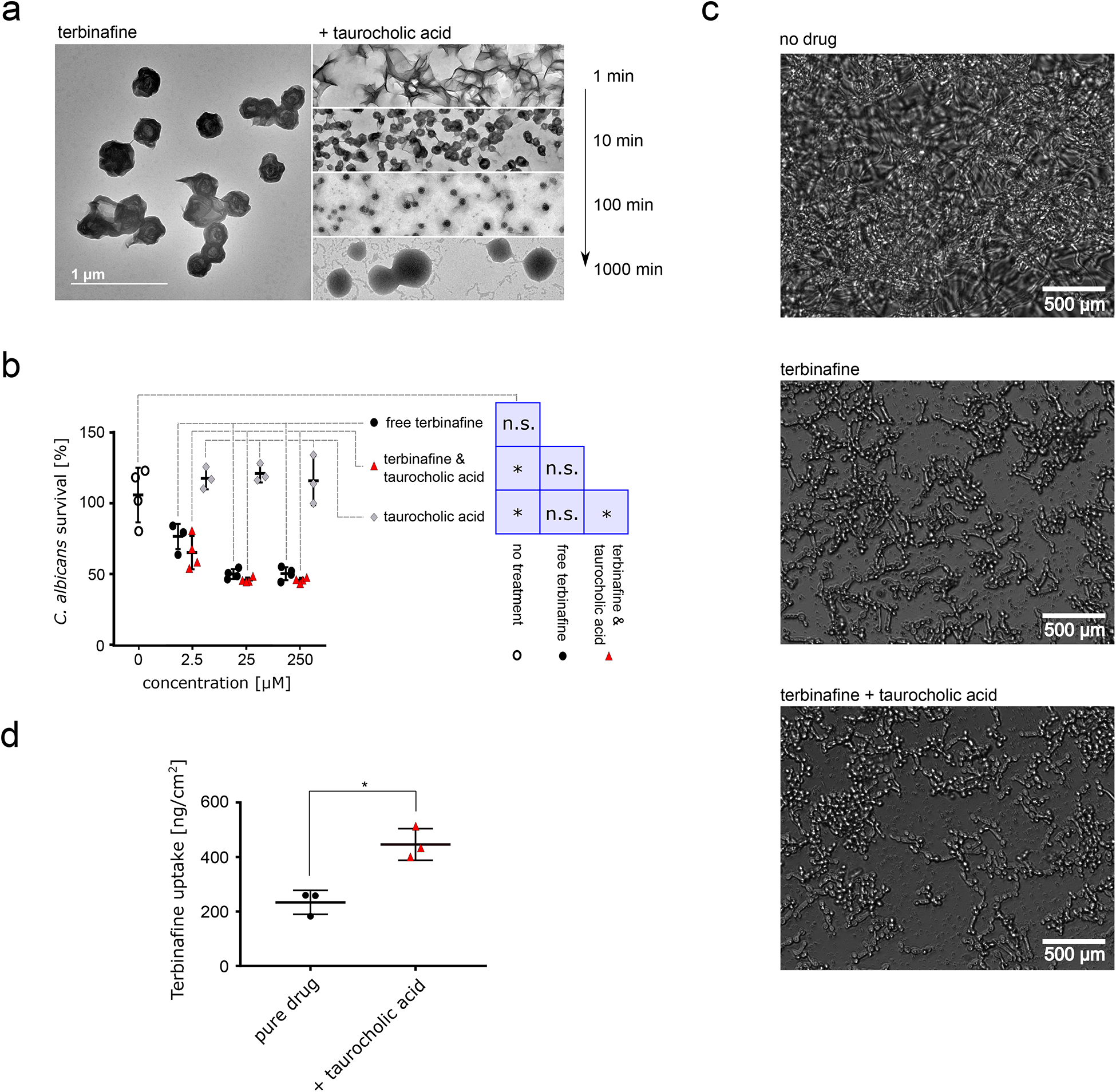

Using TEM, we observed distinct aggregation dynamics with populations of different types of low-density nanoparticles forming. Through timed TEM imaging, we identified three different types of nanostructures, corresponding to different phases of the nanoparticle formation process (Figure 3a). The particles grew over the course of several hours, most likely through condensation or coagulation24. We hypothesized that the particles could nevertheless provide useful materials since these growth dynamics were sufficiently slow to warrant the biochemical application of fresh particles11,25.

Figure 3: Characterization and ex vivo application of terbinafine & taurocholic acid particles.

a TEM images of terbinafine alone (left) and nanoparticles formulated together with taurocholic acid. TEM images taken at different timepoints after co-assembly initiation are depicted on the right. Scale bar corresponds to 1 μm, scale consistent across images. b C. albicans survival after treatment with terbinafine alone (black), terbinafine & taurocholic acid nanoparticles (red), or pure taurocholic acid (formulation control, light grey). Concentrations indicate terbinafine and/or taurocholic acid concentration. XTT readouts were normalized according to untreated control (100% survival, 1% DMSO in PBS, hollow circles), n = 4 independent samples, lines correspond to mean values, error bars represent one standard deviation. We performed a one-way ANOVA (p = 0.017) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test and found that terbinafine alone shows no significant difference to any other condition while terbinafine-taurocholic acid significantly reduced C. albicans viability compared to the control treatments. c Microscopy images of C. albicans after 17h of nanoparticle treatment or terbinafine treatment compared to untreated control. d Skin uptake of terbinafine into porcine flank skin in Franz Diffusion cell measurements, n = 3 independent samples, p = 0.028 two-sided T-test. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation. For a and c, representative images are shown from ten acquisitions generated through two independent experiments, all images reproduced the here depicted behaviour.

We purified the nanoparticles using centrifugation. The particles exhibited low density and precipitated in the supernatant. Analytics of purified nanoparticles revealed high encapsulation efficiency (75.6 ± 0.4%) and drug loading (93.0 ± 0.5 % w/w) (Supplementary Table 9). We performed a chemical analysis using Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy-Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy and found that the nanoparticles contained sulphur from the excipient taurocholic acid – providing further evidence that the nanoparticles are indeed co-aggregates of drugs and excipients (Supplementary Figure 7).

Next, we tested whether the nanoparticles would retain the fungistatic effect of terbinafine against Candida albicans, a major source of onychomycosis in immunocompromised individuals26. Measuring in vitro viability for Candida albicans revealed a significant effect of our nanoparticles compared to the vehicle and non-treatment control while terbinafine alone showed no significant difference to any treatment (one-way ANOVA p = 0.017, Tukey’s post-hoc p < 0.05). Our particles halted biofilm formation with slightly higher but comparable efficiency compared to free terbinafine; the excipient alone was not fungistatic (Figure 3b and 3c).

Skin uptake of our nanoparticles was twice that of free terbinafine (Figure 3d) – possibly due to higher diffusivity of the smaller particles as expected according to the Stokes-Einstein equation27,28 or through permeation enhancement caused by the excipient taurocholic acid29. Taken together, our data suggested that our nanoparticles can retain the fungistatic activity of free terbinafine while locally increasing bioavailability.

Sorafenib nanoparticles improve anti-cancer efficacy in vivo

For our second proof-of-concept study, we selected sorafenib nanoformulations. Sorafenib is a multi-kinase inhibitor used as a therapeutic to treat several types of cancer and the standard of care for frontline therapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)30. However, given modest clinical efficacy of sorafenib and due to increasing incidence rate31 and poor prognosis of HCC30, there is a pressing clinical need for new therapeutic options. Nanoparticles have been shown to improve sorafenib efficacy11, which motivated us to use our platform to identify sorafenib nanoparticles.

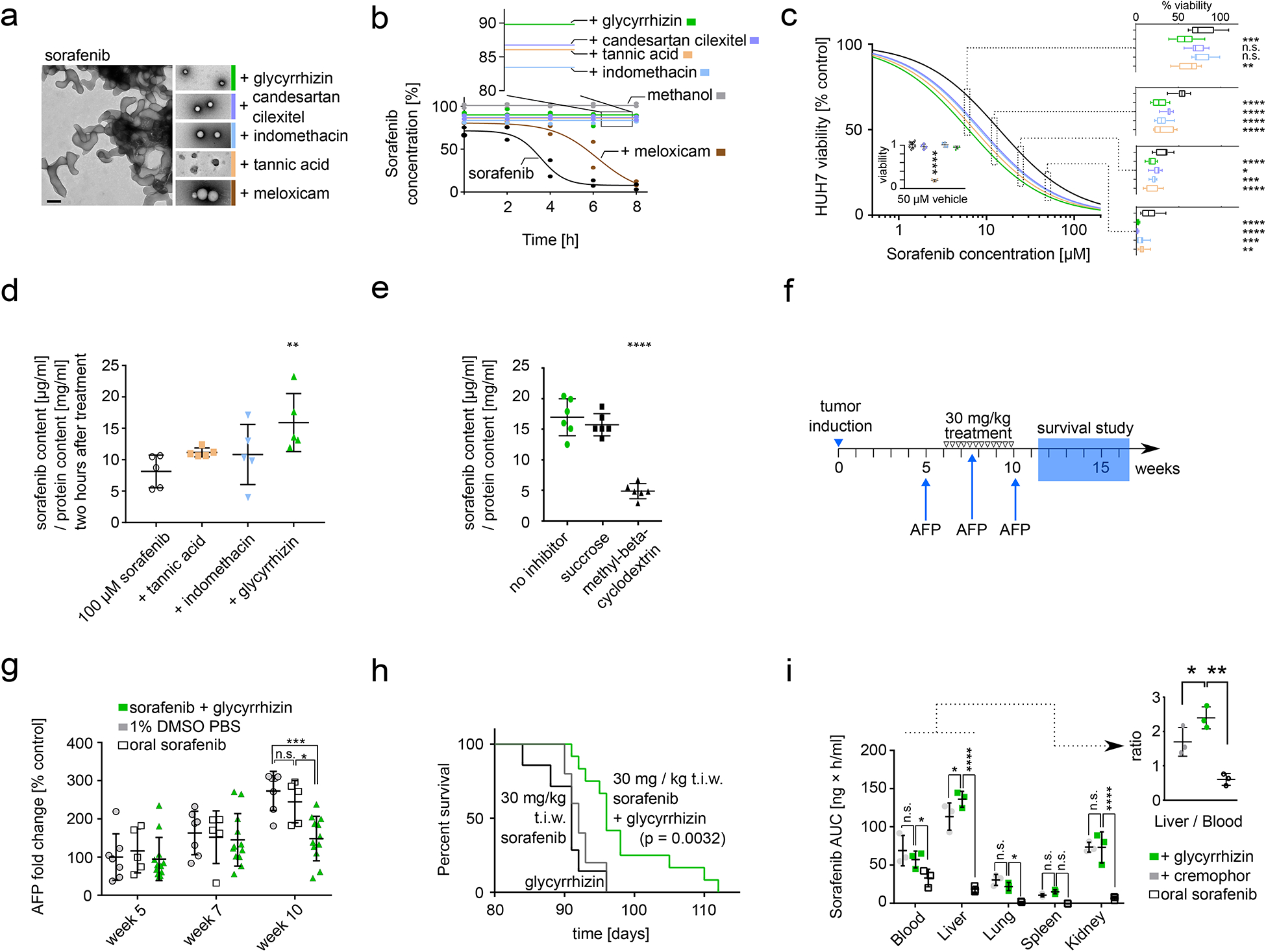

We decided to contextualize our predicted stabilizer glycyrrhizin against the screening hits candesartan cilexitel, indomethacin, and tannic acid. Meloxicam, a low confidence prediction, was included since it represents a cyclooxygenase inhibitor like indomethacin. Although none of these molecules had been used as excipients in self-assembling nanoparticles before, they are well understood to be safe or have been proposed to be used clinically together with sorafenib. Although glycyrrhizin is a known 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor associated with reversible hypermineralocorticoid-like effects after intensive consumption, it is still considered a safe food and drug ingredient with daily consumption of up to 3.6 mg/kg32. Tannic acid is “generally regarded as safe”14. Candesartan has been co-administered clinically with sorafenib to counter sorafenib-associated hypertension33. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors such as meloxicam and indomethacin have been studied as synergistic enhancers of the anticancer effects of sorafenib34,35. Formulating sorafenib with such drugs might constitute an important step towards excipient-free formulations where all included materials serve a therapeutic purpose5.

Using DLS and TEM, we measured the size of the co-assembled nanoparticles created with the five excipients; all nanoparticles had radii below 100 nm (Figure 4a, Supplementary Table 10), complying to stringent nanoformulation thresholds36. All particles enabled full drug dispersion over eight hours (Figure 4b), except for meloxicam that provided only marginal stability. DLS indicated a potentially longer stability (Supplementary Table 11).

Figure 4: Characterization and in vivo application of sorafenib nanoparticles.

a TEM images of colloidal aggregates formed by unformulated sorafenib (left) compared to TEM images of nanoparticles formulated with glycyrrhizin, candesartan cilexitel, indomethacin, tannic acid, and meloxicam. Black scale bar corresponds to 200 nm, scale consistent over all images. Coloured border added to visually aid identification of nanoparticles across all panels. Representative images are shown from ten acquisitions generated through two independent experiments, all images reproduced the here depicted behaviour. b Dispersion of sorafenib alone and in nanoformulation with excipients, measured as concentration-time curve by HPLC. Percentages for nanoparticles reflect encapsulation efficiency. n=2 independent samples. c HUH7 human hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival after 48 h of treatment with different nanoparticles or free sorafenib. Dose-response curves were fitted in Prism using the inhibitor vs. response (three parameters) model, Sorafenib IC50 = 14 ± 1.1 μM, Sorafenib & glycyrrhizin IC50 = 6.2 ± 0.6 μM, Sorafenib & candesartan cilexetil IC50 = 8.7 ± 0.7 μM, Sorafenib & Indomethacin IC50 = 8.4 ± 0.8 μM, Sorafenib & tannic acid IC50 = 7.3 ± 0.7 μM. n = 10 independent samples. Graphs on the right show box plots of individual measurements (p = 0.0013 two-way ANOVA). The nanoparticle formations were significantly more potent compared to unformulated sorafenib at all tested concentrations above 6 μM (p < 0.05, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles, line is the median, whiskers extend from maximal to minimal measurement. Insert shows HUH7 viability after 48 h of incubation with 50 μM excipients only (coloured dots) or buffer control (hollow circles). Difference to buffer control was evaluated using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation. n = 4 independent samples. d Cytosolic sorafenib in HUH7 cells after 2h incubation with unformulated sorafenib (black), sorafenib-tannic acid particles (orange), sorafenib-indomethacin particles (blue), or sorafenib-glycyrrhizin particles (green). All treatments were added at 100 μM. n = 5 independent samples, p = 0.016 one-way ANOVA. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation. e Independent uptake mechanism study with same experimental conditions as (d) but including endocytosis inhibitors sucrose or methyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Sucrose inhibits clathrin-dependent endocytosis, which did not affect cytosolic sorafenib levels (p = 0.52, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Methyl-beta-cyclodextrin inhibits caveolin-mediated endocytosis and significantly reduced cytosolic sorafenib levels (p < 0.0001, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). p < 0.0001 one-way ANOVA. n = 6 independent samples. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation. f Schematic of in vivo experiment. Tumour was induced by injection of oncogene-coding plasmids. 5 weeks after induction, AFP levels were determined to assess tumour progression and enable group randomization. Mice were randomized according to AFP-levels and then treated three times a week (t.i.w.) for four weeks. Treatments were 30 mg / kg sorafenib--glycyrrhizin nanoparticles, 30 mg / kg sorafenib oral, 30 mg / kg sorafenib in cremophor-ethanol, glycyrrhizin vehicle control, cremophor–ethanol vehicle control, 1% DMSO in PBS buffer control. AFP levels were measured at week 7 and week 10 to assess tumour progression during treatment period (cf. Figure 4g). After this final intervention, mice were monitored for morbidity-free survival (cf. Figure 4h). g AFP levels of mice after receiving sorafenib–glycyrrhizin nanoparticles, oral sorafenib, or 1% DMSO in PBS buffer control. AFP levels were compared at beginning of treatment (week 5), during treatment (week 7), and at end of treatment (week 10). p = 0.027 two-way ANOVA, significance levels shown for Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for all possible treatment comparisons, n = 12, 7, and 5 independent animals for sorafenib-glycyrrhizin, vehicle control, oral sorafenib. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation. h Kaplan-Meyer analysis shows that mice treated with sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles show longer morbidity-free survival (p = 0.0032, log-rank Mantel-Cox test) compared to oral sorafenib and glycyrrhizin-only vehicle control, n = 12 independent animals for sorafenib-glycyrrhizin and vehicle control, n = 5 for oral sorafenib. i Biodistribution analysis of sorafenib tissue accumulation for sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles (green) compared to oral sorafenib administration (white) and sorafenib dissolved in cremophor-ethanol (grey). AUC for sorafenib-glycyrrhizin is compared to the two other treatments per tissue using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. p < 0.0001 two-way ANOVA. Insert shows relative sorafenib content of liver compared to blood. Sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles show significantly better targeting to the liver compared to sorafenib in cremophor-ethanol (p = 0.014, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and oral sorafenib (p = 0.0012, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). p = 0.0014 one-way ANOVA, n = 3 independent animals per condition and timepoint. Lines corresponds to mean values; error bars represent one standard deviation.

We applied our particles in vitro in a cellular phenotypic screen. The nanoparticles exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity in human liver carcinoma HUH7 with two-fold more potent IC50 values compared to the unformulated drug (Figure 4c). We confirmed that nanoparticle formation did not prevent sorafenib from engaging with one of its main targets Raf1 by observing an equivalent inhibition of MEK phosphorylation compared to free sorafenib (Supplementary Figure 8).

With the exception of tannic acid, none of the utilized excipients showed significant cytotoxicity in HUH7 alone (Figure 4c insert and Supplementary Figure 9) - ruling out additive effects leading to the increased cytotoxicity. Instead, we proposed that the nanoparticles enable higher drug uptake compared to the larger micro-scale structures formed by unformulated sorafenib (Supplementary Figure 10). The glycyrrhizin particles most significantly improved drug availability and almost doubled cytosolic sorafenib content (Figure 4d), potentially enhanced by glycyrrhizin’s ability to target hepatocytes37. Inhibiting caveolin-mediated endocytosis strongly reduced particle uptake while modulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis did not affect uptake (Figure 4e).

We purified our particles using centrifugation, which revealed that the nanoparticles had high drug loading (94.9 ± 1.2%) and encapsulation efficiency (92.6 ± 0.6%) (Supplementary Table 12). Using Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy-Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy, we observed that the particles contained fluorine from sorafenib (Supplementary Figure 11) – confirming that the particles are enriched with drug as expected from the analytics (Supplementary Table 12). Using DLS, we observed that the particles were stable in serum and cell media and were not disrupted by shearing forces when administered through a 29 Gauge needle, or by centrifugation followed with ultrasound-mediated re-dispersion (Supplementary Figure 12).

We refined our formulation protocol to consistently generate nanoparticles containing 3 mg / mL sorafenib (Supplementary Figure 13) that enabled us to dose 30 mg / kg for intravenous injection. In a toxicity analysis, our formulation did not induce abnormal liver function after three injections of elevated dosages of 60 mg / kg (Supplementary Table 13). Next, we compared the in vivo antitumour efficacy of our sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles to sorafenib alone in an established genetic mouse model of spontaneous HCC38,39, the most common type of liver cancer. Tumourigenesis is induced by an overexpression of human ΔN90-β-catenin and human MET genes in the mouse liver and represents an aggressive model of HCC characterized by rapid formation of a large number of tumour nodules38. We chose this model because it correlates more strongly with clinical outcomes compared to simpler xenograft-based models39–41.

HCC bearing mice were treated three times a week (t.i.w.) for four weeks with our nanoparticle formulations or control treatments (Figure 4f). We tracked alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, a marker of HCC progression and transformed hepatocytes42. While no differences were visible during the early stages of treatment, at week 10 the sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles showed a successful reduction in serum AFP levels (Figure 4g). We observed a similar reduction of AFP in mice receiving only glycyrrhizin (Supplementary Figure 14), which is potentially caused by known hepatoprotective effects of glycyrrhizin43. This is encouraging since, although we know glycyrrhizin does not target HCC directly (Figure 4c, Supplementary Figure 8), it indicates a potential for glycyrrhizin to act as a functional adjuvant. The control treatment of sorafenib dissolved in cremophor-ethanol had no effect on AFP levels (Supplementary Figure 15). Body weight data suggested that mice treated with sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles had a significantly reduced tumour burden (Supplementary Figure 16) compared to control treatments (Supplementary Figure 17), but we cannot exclude that the body weight difference is at least in part impacted by confounding variables such as loss of appetite.

We evaluated treatment efficacy based on the calculation of morbidity-free survival fractions using the Kaplan-Meier method. Mice treated with sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles had significantly longer morbidity-free survival (p = 0.0032, logrank test) compared to mice treated with vehicle control (intravenous injections of glycyrrhizin in 1% DMSO PBS) or mice receiving oral sorafenib (Figure 4h). The only other control treatment that showed any therapeutic benefit was sorafenib solubilized in cremophor-ethanol (Supplementary Figure 18); however, the adverse toxicity of cremophor is an important limitation of this formulation44.

For pharmacokinetic characterization, we measured the concentration-time course of sorafenib in blood, liver, lung, spleen, and kidney after administering our sorafenib-glycyrrhizin particles to healthy mice (Supplementary Note 4). We compared our formulation to oral administration of sorafenib and to an intravenous injection of sorafenib dissolved in cremophor-ethanol (Figure 4i, Supplementary Figure 19). Our sorafenib-glycyrrhizin particles significantly improved liver targeting (Figure 4i insert; Supplementary Note 5). Other researchers have shown a preferred accumulation of similar nanoparticles in the lung11,25, suggesting that liver accumulation of these particles is driven by physicochemical differences between our formulation and those previously reported. Overall, our data suggests that this hepatic targeting, combined with endocytosis-driven active drug uptake of the nanoparticles into hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Figure 4e) and the ability of the particles to release sorafenib to act on its established pathways (Supplementary Figure 8) can explain the improved treatment efficacy of our nanoparticles (Figure 4h).

Conclusion

Small molecule-based nanoparticle systems are an important addition to nanomedicine, enabling rapid generation of highly loaded nanocarriers for life-saving therapeutics10,11. High drug loading will ultimately reduce the risk of excipient-triggered adverse reactions9 and reduce administered volumes, improving adherence and quality of life45. With machine learning and high-throughput experimentation (Supplementary Note 6), we broaden the scope of this technology and include a wide array of different types of drugs treating various diseases. Using FDA-approved excipients such as vitamins, nutrients, and food compounds generates nanoformulations with potential for accelerated translation.

Under fixed conditions, co-aggregation can be conducted in a highly reproducible manner (Supplementary Figure 13) with low PDI (Supplementary Table 7 and 10). An important challenge and opportunity lies in the context-sensitive nature of the self-assembly process. Buffer conditions such as pH, temperature, and salt concentrations can significantly alter the co-aggregation propensity of the materials2,3,46. Variations of these conditions during manufacturing could further broaden the scope of such platforms and include materials currently unsuitable for simple co-precipitation.

Additionally, aggregation context can provide further opportunities for the development of adaptive systems that co-aggregate specifically in situ, for example in gastric conditions47. This might ultimately enable responsive systems. For example, we had observed that some of our aggregates grow when heated (Supplementary Figure 20), potentially due to Ostwald ripening and elevated collision rates24. If such conditions can be controlled, dynamic changes to the nanoparticles might be harnessed for adaptive delivery solutions48.

In order to improve the selection of specific nanoparticles for various applications, it would be useful to have methods that predict physical properties of these nanoparticles. Investigating focused sets of nanoparticles can enable size prediction11. We have provided further evidence that nanoparticle size can correlate with particle stability (Figures 2 and 4). Furthermore, our data suggests that predictive uncertainty measures (cf. meloxicam in Figure 4) as well as MD analysis (cf. riboflavin in Figure 2) can be used to anticipate nanoparticle stability. Models that could anticipate more complex properties such as biodistribution and release kinetics would further facilitate nanoparticle selection. Finally, further maturing the described materials, for example to enable functionalization and encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs (Supplementary Note 7), will expand the number of possible applications of these co-aggregates. By accelerating the development of nanomedicines, we anticipate that the approach reported herein and extensions thereof will be an important step towards personalized drug delivery9.

Online Methods

High-throughput formulation assessment

Stock solutions (10mM) of aggregating drugs and excipients were created in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20 °C. For every experiment, 1 μl of the drug stock solution was mixed with 1 μl of the stock solution of any of the excipients (1:1) in a 96 well plate using a Tecan Freedom Evo 150 liquid handling deck. Mixing of the two droplets was ensured through centrifugation. Subsequently, we rapidly added 198 μl of sterile-filtered and degassed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for solvent exchange and mixed the formulation through repeated pipetting. 75 μl of replicate samples were subsequently transferred into a 384 well plate for high-throughput dynamic light scattering assessment on a Wyatt Dyna Pro Plate Reader at 25 °C using 5 independent acquisitions of 5 s duration. DLS enables us to quantitatively assess nanoparticle formation by measuring the size of resulting co-aggregates with help of the “globular protein” model. Data was processed by calculating the median size observed for a specific drug. We required at least a 50% size reduction of the co-aggregate compared to drug alone to indicate nanoparticle formation. Our analysis suggested that this threshold could potentially enable an inclusive separation of what appeared to be a bimodal distribution of aggregate sizes across our screen (Supplementary Figure 2). Measures of polydispersity and replicate variance were considered but did not lead to improved predictive performance. We noted that drug self-aggregates would result in a large number of flagged DLS acquisitions, indicating unreliable readouts through macro-aggregates and precipitation, while no such artefacts were observed for our nanoparticles.

Machine learning

Chemical structures for all drugs in SMILES representation were extracted from DrugBank 5.0.15 Data for excipients was extracted from the FDA according to previously published protocols.9 Compounds were described according to radial chemical substructures (Morgan Fingerprint, radius 4, 2048 bits, rdkit.org) and calculated physicochemical properties (rdkit.Chem.Descriptors._descList, rdkit.org) based on previously published evaluations.16,17 Concatenating the substructure description and the physicochemical properties for every drug and every excipient generated a 4496-dimensional description of a drug-excipient formulation. Additionally, short MD simulations were run and automatically analysed to assess the enthalpic, non-covalent interaction potential between drugs and excipients. In brief, atomic partial charges for drugs and excipients were derived from antechamber and parmchk2 and the net charge was calculated using the OpenEye Quacpac AM1-BCC method. Two excipient and two drug molecules were randomly positioned using packmol (m3g.iqm.unicamp.br/packmol/) and amber’s tleap module. After energy minimization of the system, short 20 ns simulations were run in OpenMM 7.2.1 (openmm.org) in OBC2 implicit solvent with non-periodic boundary conditions and no cut-off distance. A Langevin Integrator was used at 300K with friction coefficient of 1/ps. The timestep of the simulation was 2 fs and the trajectory was saved every 10 ps, creating 2,000 frames. These trajectories were processed with MDTraj (mdtraj.org) to calculate heavy atom distances between drugs and excipients and derive summary statistics (maximum, minimum, and average distance, as well as maximum first derivative) for each pair. Furthermore, the potential and kinetic energies of the conformation in the last frame were calculated. Overall, this gave us an additional 19 parameters to characterize drug and excipient pairs as input to the machine learning platform. These 4515-dimensional numerical characterizations of a formulation served as input for the random forest classification machine learning model (scikit-learn) with 500 trees and using ⌊√4515⌋ = 67 features per classification tree. This model was compared to Naïve Bayes (GaussianNB), Nearest Neighbor (KNeighborsClassifier; k=3), Decision Trees (DecisionTreeClassifier), Neural Networks (MLPClassifier), and a Support-Vector machine (LinearSVC) implemented with default parameters in scikit-learn. To analyse the correlation between training data set size and model performance, we trained our Random Forest model on randomly selected subsets of the data and evaluated out-of-bag predictive performance as a measure of model convergence. This analysis was run twenty times and mean performance was reported. Code and data for all these calculations can be found at https://github.com/DanReker/CoAggregators.

Additional molecular dynamics simulations

For the six novel combinations of drugs and excipients, we converted SMILES compound representations to Tripos mol2 files using Openbabel with B3LYP/6–31G* partial charge calculation with GAFF force field and systematic rotor search for generating 3D conformations. If systematic confirmation search was rate limiting, the process automatically switched to a weighted search. Missing parameters were checked with the parmchk2 module in Ambertools. Using packmol, five random system configurations were generated for 20 molecules of each pair (20+20=40 molecules total), or 20 molecules of drug only. A topology and coordinate file were generated with the tleap module in Ambertools. OpenMM 7.3.1 was used to create a 20ns simulation under OBC2 implicit solvent at 1 bar, 300K, with periodic cut-off distance of 1nm after initial minimization. The last frame of this simulation was visualized in PyMol using coloured Van-der-Waals spheres. Molecular interactions for the last frame were determined using the MolBridge webserver (nucleix.mbu.iisc.ernet.in/molbridge) as well as extracting Baker-Hubbard Hydrogen Bonds between drugs and excipients through MDTraj (http://mdtraj.org/).

Dispersion kinetics

Dispersion stability of nanoparticles was performed according to established protocols by the OECD “Dispersion Stability of Nanomaterials in Simulated Environmental Media” (Supplementary Figure 5).21 Specifically, dispersion was studied at 250 μM drug concentration, except for altered concentrations for celecoxib (500 μM) or nelfinavir (50 μM) to enable studying dynamics at the same time scales compared to other drugs in spite of slower/faster aggregation dynamics and therefore sedimentation rate. Formulations were generated by mixing 5 μl of drug stock solution with 5 μl equimolar excipient stock in DMSO or 5 μl DMSO, followed by solvent exchange by adding 990 μl sterile filtered and degassed PBS. All samples were generated in 4 ml glass vials, briefly vortexed to ensure dispersion, and subsequently stored sealed at room temperature. Formulations were then sampled at pre-determined timepoints by extracting 5 μl of formulation with a standard Eppendorf pipette from the centre of the vial. The extracted 5 μl samples were transferred into individual high-performance liquid chromatography sample vials (Sigma Aldrich) and diluted in acetonitrile (for atovaquone, danazol) or methanol (for celecoxib, sorafenib, terbinafine, nelfinavir) to ensure full solubility of the drug before injection onto the column. Diluted samples were stored at 4°C and drug concentrations were determined via liquid chromatography within 24h as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Candida albicans XTT assay and microscopy

Candida albicans were incubated in sterile 50 g/L Difco YPD broth overnight at 30 °C on an orbital shaker at 300 rpm. Centrifuging at 3220 g for 5 mins was used to extract the fungus. Washing was performed twice with PBS. The final pellets were re-suspended in 20mL RPMI1640 (Sigma Aldrich). The fungi concentration was determined using a haemocytometer with bright-field microscopy at 40x magnification. Fungi were seeded at a concentration of 1 million per well in 96-well plates. Terbinafine-taurocholic acid particles, free terbinafine, or Taurocholic acid excipient control were added at concentrations of 250 μM, 25 μM and 2.5 μM. PBS containing 1% DMSO was used as buffer control and 70% isopropanol was used as positive treatment control. Plates were wrapped with parafilm and incubated at 37 °C. Fungi viability was evaluated using an XTT assay after 24h of incubation. To this end, XTT was prepared as a saturated solution at 0.5 g/L in sterile PBS under light protection and subsequently sterile filtered with a 0.22-μm pore size filter. XTT solution was aliquoted in 10 ml Falcon tubes and stored at −80 °C. Before a measurement, 1 μL of a 10 mM menadione solution in acetone was added to the XTT solution and used to substitute the media. Absorbance was measured at 490nm to determine background signal per well. Plates were subsequently incubated for another 2h at 37 °C under light protection and absorbance was measured at 490nm to determine fungus viability. Treatment data was normalized to untreated control (100% survival, 1% DMSO in PBS) and positive treatment (70% ethanol) was used to ensure experimental consistency. For microscopy, 40x bright-field images were taken after 17h incubation using 25 μM free terbinafine, 25 μM terbinafine-taurocholic acid nanoparticles or 1% DMSO PBS buffer control at 37 °C.

Skin uptake of terbinafine particles

All ex vivo studies were approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care. Fresh porcine ear samples were provided by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology facilities and were washed three times with PBS and mounted on a Franz diffusion cell (FDC-400 flat flange, 15 mm orifice diameter, mounted on an FDC diffusion drive console providing synchronous stirring at 350rpm, Crown Glass Co. Inc., Sommerville, N.J., USA) by gluing the epidermis side of the skin to the donor chamber and subsequent mounting onto the receiver chamber that was preloaded with PBS. Terbinafine-taurocholic acid nanoparticle or free terbinafine were added at 250 μM in 1% DMSO PBS and loaded to the donor chambers in triplicates. PBS containing 1% DMSO served as buffer control. Parafilm was used to prevent evaporation from both the receiver and the donor chamber. After 4h of incubation, donor solutions were removed and the skin was washed with PBS to remove excess drug. The perfusion area was cut into squares and weighed and measured for further analysis. Skin samples were loaded into 2 mL homogenizing tubes (Fisher Scientific, Fisherbrand™ Pre-Filled Bead Mill Tubes) with methanol at a 1:2 ratio and homogenized at 6000 rpm for 40s × 3. Homogenate was analysed for drug content using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) as described in the Supplementary Methods.

HUH7 cell survival assessment

HUH7 cells were gifted by Dr. Jay Horton (UT Southwestern Medical Center). Cells were not authenticated. Cells were tested negative for Mycoplasma contamination by the Diagnostic Laboratory of the Division of Comparative Medicine at MIT. Cells were plated at 10,000 cells in 96 well plates and incubated overnight to allow adhesion. Cell medium was changed and cells were treated with various concentrations of nanoparticles for 48h. These concentration series were generated by creating a dilution series of the drug stock solutions and then performing nanoparticle generation at altered stock concentrations. Cell viability was measured through quantitation of ATP using CellTiter-Glo (Promega).

Sorafenib uptake experiments

HUH7 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 200,000 cells (1ml DMEM) and incubated for 24h to allow for adhesion. Cell medium was changed (900 μl) and cells were treated with (100 μl, 10x) 100μM sorafenib, 100μM of nanoparticle formulations, or buffer control (0.1% DMSO PBS) and incubated for 2h. Afterwards the supernatant was removed and cells were carefully washed 3 times using 2.5% Tween-80 in PBS, which we had tested to ensure it dislodged sorafenib aggregates while not changing cell adhesion or morphology according to brightfield microscopy images. Cells were lysed with Pierce RIPA Buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and transferred. Subsequently, lysate was lyophilized and re-dissolved in methanol (200 μl). The solution was centrifuged (10min at 3200RPM) and supernatant was subsequently analysed using HPLC for sorafenib content as described in the Supplementary Methods. Area under the curve (AUC) values were converted into sorafenib content (μg / ml) according to a standard curve and normalized according to protein content per replicate (mg / ml) from an orthogonal BCA assay. To study the mechanism of increased uptake of sorafenib-glycyrrhizin particles, we performed another uptake experiment according to the protocol above, but pre-incubated the cells for 30 minutes with sucrose (0.15 g/ml) or methyl-beta-cyclodextrin (5mM) to inhibit endocytosis.

Drug loading and encapsulation efficiency

Particles were generated using stock concentrations of 10 mM for both drugs and excipients. Particles were subsequently washed using two rounds of centrifugation, removal of supernatant, and re-dispersion in PBS. Particles were then dissolved in fixed volumes of methanol to ensure full solubility. These solutions were subsequently submitted to liquid chromatography analysis to determine the concentration of drug and excipient in these solutions. Amount of drug or excipient in the particles was calculated by subtracting the expected amount (ug) of drug/excipient assuming full solubility in PBS from the actually measured concentrations. Encapsulation efficiency was determined as the amount of drug found in the particles (ug) divided by the amount of drug added via the stock solution in particle production (equation 1).

| (eq 1) |

Drug loading was calculated as the amount of drug in the particles (ug) divided by the mass of the particles given by the cumulative amount of the drug (ug) and the amount of excipient (ug) in the particles (equation 2)

| (eq 2) |

In vivo cancer study

All in vivo studies were approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care. Female FVB/N mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Animals were maintained in a conventional barrier facility with a climate-controlled environment on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, fed ad libitum with regular rodent chow. Hepatocellular carcinoma was induced as previously described.38,39 Briefly, plasmids encoding human ΔN90-β-catenin, human MET, and SB transposase were hydrodynamically injected intravenously into 6–7-week-old mice. Plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Xin Chen (UCSF, San Francisco, CA). Plasmids were amplified and isolated in endotoxin free conditions (< 5 EU/mg) by Aldevron (Fargo, ND). Five weeks after injections serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) were analysed as HCC marker and animals were randomized according to AFP-levels into the different treatment groups. Treatment was started six weeks after HCC induction, and each group of mice was treated three times a week for four weeks with one of the following treatments: intravenous injections of 30 mg/kg sorafenib in sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles, sorafenib suspensions at 30mg/kg in PBS with 1% DMSO delivered by oral gavage, intravenous injections of buffer control (1% DMSO in PBS), intravenous injections of 30 mg/kg sorafenib solubilized in a 50:50 ethanol-cremophor mixture, or intravenous injections of glycyrrhizin in 1% DMSO in PBS (vehicle control). Mice were evaluated twice daily for tumour burden (>15% increase in bodyweight) and other clinical signs of discomfort such as laboured breathing, lethargy, lack of appetite, cachexia, diarrhoea, poor grooming, hunched appearance, and lack of nest building. After the four-week treatment period, AFP levels and bodyweight changes were recorded to evaluate treatment success. Treatment was stopped and mice were evaluated twice daily for progression-free survival according to the same signs of adverse effects.

Biodistribution of sorafenib formulations

Healthy, 10-week-old, female FVB/N mice were injected with a single dose of 30 mg/kg sorafenib-glycyrrhizin nanoparticles, 30 mg/kg sorafenib dissolved in cremophor-ethanol, or received a suspension of 30 mg / kg sorafenib in PBS orally. Three mice per group were humanely euthanized at 30 min, 2h, 4h, 6h, and 24h after administration to process organs and blood. For sample preparation, 5% BSA in PBS buffer was added at a 2:1 volume to mass ratio. Samples were homogenized at 6500 rpm 2x for 2.00 minutes at room temperature. 100 μl of each homogenate was spiked with 50 μl of 5 μg/mL internal standard in acetonitrile. Ethyl acetate (1ml) was added to homogenized samples as well for extraction. Samples were vortexed, sonicated for 10 minutes, and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 6,000 rpm. Following centrifugation, the collected supernatant was allowed to evaporate. The evaporated samples were reconstituted with 300 μl acetonitrile and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 6,000 rpm. 200 μl of the supernatant was pipetted into a 96-well plate containing 200 μl of water. Finally, 0.50 μl was injected onto the UPLC-ESI-MS system for the analysis of sorafenib content. AUC for each organ were calculated using numerical integration following the trapezoidal rule.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

D.R. is a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellow (Grants P2EZP3_168827 and P300P2_177833). Y.R. is grateful to the MIT Skoltech Initiative for financial support. A.R.K. is grateful to the PhRMA foundation postdoctoral fellowship for financial support. We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support, specifically the High Throughput Sciences Facility, Nanotechnology Materials Facility, the Animal Imaging and Preclinical Testing core, and the Histology core. This work was supported in part by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute and by the NIH Grant EB000244. We are grateful to OpenEye for providing us with an OpenEye Academic License. We are grateful to Hormoz Mazdiyasni for technical support and to Miguel Jimenez for providing access to C. albicans and helpful discussions throughout the study.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS D.R., Y.R., A.R.K., R. C., J.W.Y., N.N., A.G., R.M.Z., R.L. and G.T. are co-inventors on multiple patent applications describing novel nanoformulation systems and interactions between excipients and drugs. D.R. acts as a mentor for the German Accelerator Life Sciences and acts as a scientific consultant for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Complete details of all relationships for profit and not for profit for G.T. can found at the following link: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/szi7vnr4a2ajb56/AABs5N5i0q9AfT1IqIJAE-T5a?dl=0. For a list of entities to which R.L. is involved, compensated or uncompensated, see https://www.dropbox.com/s/yc3xqb5s8s94v7x/Rev%20Langer%20COI.pdf?dl=0.

DATA AVAILABILITY All data used in this study was extracted from publicly available sources from the DrugBank website (version 5.0, drugbank.ca), the FDA (GRAS version June 2016 and IIG version 0716 UNII 362O9ITL9D datasets, www.fda.gov), and the Shoichet laboratory (bkslab.org/takeaways/aggregator_hts). The processed and curated data is made available through the GitHub repository https://github.com/DanReker/CoAggregators.

CODE AVAILABILITY All code for this study to perform simulations and machine learning is available on a public GitHub repository at https://github.com/DanReker/CoAggregators.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permission information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to G.T.

References

- 1.Hopkins AL, Keserü GM, Leeson PD, Rees DC & Reynolds CH The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 13, 105–121 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin JJ et al. An Aggregation Advisor for Ligand Discovery. J. Med. Chem 58, 7076–7087 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reker D, Bernardes GJL & Rodrigues T Computational advances in combating colloidal aggregation in drug discovery. Nat. Chem 11, 402–418 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen SC, Doak AK, Wassam P, Shoichet MS & Shoichet BK Colloidal aggregation affects the efficacy of anticancer drugs in cell culture. ACS Chem. Biol 7, 1429–1435 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kipp JE The role of solid nanoparticle technology in the parenteral delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 284, 109–122 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mcdonald TO et al. Antiretroviral Solid Drug Nanoparticles with Enhanced Oral Bioavailability: Production, Characterization, and In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation. Adv. Healthc. Mater 3, 400–411 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govender T, Stolnik S, Garnett MC, Illum L & Davis SS PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. J. Control. Release 57, 171–185 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westesen K, Bunjes H & Koch MH. Physicochemical characterization of lipid nanoparticles and evaluation of their drug loading capacity and sustained release potential. J. Control. Release 48, 223–236 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reker D et al. ‘Inactive’ ingredients in oral medications. Sci. Transl. Med 11, eaau6753 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin CK et al. Stable Colloidal Drug Aggregates Catch and Release Active Enzymes. ACS Chem. Biol 11, 992–1000 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamay Y et al. Quantitative self-assembly prediction yields targeted nanomedicines. Nat. Mater 17, 361 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FDA. Inactive Ingredient Search for Approved Drug Products. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/iig/.

- 13.Feng Brian Y, Shelat Anang, Dorman Thompson N, Guy R Kip & Shoichet Brian K. High-throughput assays for promiscuous inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol 1, 146–148 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.FDA. SCOGS (Select Committee on GRAS Substances). Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set=SCOGS.

- 15.Wishart DS et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reker D et al. Machine learning uncovers food- and excipient-drug interactions. Cell Rep. 30, 3710–3716.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reker D, Schneider P & Schneider G Multi-objective active machine learning rapidly improves structure-activity models and reveals new protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Chem. Sci 7, 3919–3927 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregori-Puigjane E & Mestres J A Ligand-Based Approach to Mining the Chemogenomic Space of Drugs. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen 11, 669–676 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildman SA & Crippen GM Prediction of physicochemical parameters by atomic contributions. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci 39, 868–873 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang KV & Keiser MJ Adversarial Controls for Scientific Machine Learning. ACS Chem. Biol 13, 2819–2821 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Test No. 318: Dispersion Stability of Nanomaterials in Simulated Environmental Media. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 3 (2017). doi: 10.1787/9789264284142-en [DOI]

- 22.Lipner SR & Scher RK Onychomycosis: Treatment and prevention of recurrence. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 80, 853–867 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClellan KJ, Wiseman LR & Markham A Terbinafine. Drugs 58, 179–202 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matteucci ME, Hotze MA, Johnston KP & Williams RO Drug nanoparticles by antisolvent precipitation: Mixing energy versus surfactant stabilization. Langmuir 22, 8951–8959 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganesh AN et al. Colloidal Drug Aggregate Stability in High Serum Conditions and Pharmacokinetic Consequence. ACS Chem. Biol 14, 751–757 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayatilake JAMS, Tilakaratne WM & Panagoda GJ Candidal onychomycosis: A Mini-Review. Mycopathologia 168, 165–173 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabral H et al. Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nat. Nanotechnol 6, 815–823 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong C et al. Multistage nanoparticle delivery system for deep penetration into tumor tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 2426–2431 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlović N et al. Bile acids and their derivatives as potential modifiers of drug release and pharmacokinetic profiles. Front. Pharmacol 9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villanueva A Hepatocellular carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 380, 1450–1462 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Serag HB & Mason AC Rising Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med 340, 745–750 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isbrucker RAA & Burdock GAA Risk and safety assessment on the consumption of Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza sp.), its extract and powder as a food ingredient, with emphasis on the pharmacology and toxicology of glycyrrhizin. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 46, 167–192 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basso U, Brunello A, Bertuzzi A & Santoro A Sorafenib is active on lung metastases from synovial sarcoma. Annals of Oncology 20, 386–387 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaparro M, González Moreno L, Trapero-Marugán M, Medina J & Moreno-Otero R Review article: Pharmacological therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with sorafenib and other oral agents. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 28, 1269–1277 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong J et al. Meloxicam combined with sorafenib synergistically inhibits tumor growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via ER stress-related apoptosis. Oncol. Rep 34, 2142–2150 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auffan M et al. Towards a definition of inorganic nanoparticles from an environmental, health and safety perspective. Nature Nanotechnology (2009). doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin A et al. Glycyrrhizin surface-modified chitosan nanoparticles for hepatocyte-targeted delivery. Int. J. Pharm 359, 247–253 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tward AD et al. Distinct pathways of genomic progression to benign and malignant tumors of the liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 104, 14771–14776 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogorad RL et al. Nanoparticle-formulated siRNA targeting integrins inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression in mice. Nat. Commun 5, 3869 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell 9, 391–403 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharpless NE & DePinho RA The mighty mouse: Genetically engineered mouse models in cancer drug development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 5, 741–754 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waidely E, Al-Yuobi ARO, Bashammakh AS, El-Shahawi MS & Leblanc RM Serum protein biomarkers relevant to hepatocellular carcinoma and their detection. Analyst 141, 36–44 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CH et al. Protective mechanism of glycyrrhizin on acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull 30, 1898–1904 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K & Sparreboom A Cremophor EL: The drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur. J. Cancer 37, 1590–1598 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh A, Iyer AK & Amiji MM Polymeric Nanosystems for Integrated Image-Guided Cancer Therapy. in Handbook of Nanobiomedical Research (ed. Torchilin V) 199–233 (2014). doi: 10.1142/9789814520652_0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pohjala L, Tammela P, Pohjala L & Tammela P Aggregating Behavior of Phenolic Compounds — A Source of False Bioassay Results? Molecules 17, 10774–10790 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Traverso G & Langer R Perspective: Special delivery for the gut. Nature 519, S19–S19 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng CJ & Saltzman WM Nanomedicine: Downsizing tumour therapeutics. Nature Nanotechnology 7, 346–347 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.