Abstract

Background

Topical azelaic acid (AzA) is a common treatment for mild/moderate inflammatory rosacea.

Aims

To assess the efficacy and tolerability of a novel formulation cream containing 15% AzA (anti‐inflammatory/anti‐oxidant/anti‐microbial agent) combined with 1% dihydroavenanthramide D (anti‐inflammatory/anti‐itch) in inflammatory rosacea using clinical/instrumental evaluation.

Methods

In this multicentre, prospective, open‐label trial, 45 patients with mild/moderate inflammatory rosacea enrolled at the Dermatology Clinic of the University of Catania, Naples, and Rome (Italy) were instructed to apply the cream twice daily for 8 weeks. Clinical evaluation was performed at baseline (T0) and at 8 weeks (T1) by (1) Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score based on a 5‐point scale (from 0 = clear/no erythema/papules/pustules to 4 = severe erythema/several papules/pustules) and (2) inflammatory lesions count. Instrumental evaluation of erythema degree was performed by erythema‐directed digital photography (EDDP) by a 5‐point scale (from 0 = no redness to 4 = severe redness) at all time points. Tolerability was assessed by a self‐administered questionnaire at 8 weeks. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.

Results

Forty‐four patients completed the study. At week 8, a significant decrease in baseline of IGA scores [median from 3 (T0) to 1 (T1)] and inflammatory lesions count [median from 8 (T0) to 1 (T1)] was recorded along with a significant reduction of erythema scores [median from 2 (T0) to 1 (T1)]. No relevant side effects were recorded.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that this new non‐irritating product represents a valid therapeutic option for mild/moderate inflammatory rosacea, and EDDP is able to provide a more defined evaluation of erythema changes.

Keywords: azelaic acid, rosacea, topical treatments

1. INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory rosacea is a common, chronic facial inflammatory disease characterized by persistent erythema, inflammatory lesions (small, dome‐shaped inflammatory papules, sometimes with superimposed pinpoint pustules or crusts, mostly symmetrically arranged) and telangiectasias (due to dilated deep/superficial vessels). 1 Its pathogenesis is multifactorial and still poorly delineated. Although environmental factors are likely to promote its development, several individual factors, such as genetic susceptibility and positive family history, innate and adaptive immune response alterations, vascular dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, neurogenic inflammation, oxidative stress and local proliferation of skin flora, have been considered. 2

Azelaic acid (AzA) is a known effective rosacea topical agent with anti‐oxidant and anti‐inflammatory properties by inhibiting reactive oxygen stress (ROS) species and downregulating cathelicidin activation via inhibition of kallikrein‐5, respectively. 3 However, skin irritation (eg pruritus, burning, or stinging) may often occur during its use. 4 Erythema‐directed digital photography is non‐invasive technique that is able to provide more precise evaluation of patient's erythema grade compared to simple clinical inspection or standard clinical photography. In particular, advanced digital photography equipped with RBX™ processing system is able to highlight the red areas corresponding to skin vascularization representing a useful tool for a more accurate evaluation of erythema/inflammation grading in some inflammatory facial disorders including rosacea. 5 This technique may also be used to enhance treatment assessment in clinical trials. 6 , 7 , 8

The aim of this multicentre, open‐label, prospective clinical trial was to assess by clinical and instrumental evaluation the efficacy and tolerability of a novel formulation cream containing 15% AzA combined with 1% dihydroavenanthramide D (an anti‐inflammatory/anti‐itch synthetic active component of oats), 9 in the treatment of inflammatory rosacea.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

From September 2018 to April 2019, 45 adult patients with mild‐to‐moderate inflammatory rosacea were enrolled at the University Hospitals of Catania, Naples, and Rome (Italy). Study duration was up to 8 weeks with a follow‐up period of at least 4 weeks. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles from the Declaration of Helsinki 1996 and Good Clinical Practices. A written informed consent was obtained from each patient before study procedures were started. Enrolled subjects were adult patients, of either sex, with mild‐to‐moderate inflammatory rosacea, who underwent a washout period of 2 or 4 weeks for topical or oral agents for rosacea, respectively. Exclusion criteria were: concurrent exposure to sunlight and/or artificial ultraviolet sources, pregnancy/breastfeeding, and/or severe underlying diseases. During the study, topical cosmetic agents, such as mild cleansers, SPF 50+ sunscreens and decorative make‐up, were provided. The patients were instructed to apply the cream twice daily for 8 weeks. Patients who withdrew the protocol for personal reasons or for onset of side effects were considered as dropout. In order to reduce potential evaluator bias, all subjects were evaluated by an investigator not directly involved in the study at baseline (T0) and at week 8 (T1). Primary endpoints for efficacy were the evaluation of all clinic parameter scores (erythema, inflammatory lesions) at week 8; secondary endpoint was the evaluation of tolerability at the end of the study.

Clinical evaluation was performed at baseline and at week 8 by: (1) Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) based on a 5‐point scale (0 = no erythema, papules and/or pustules; 1 = very mild erythema: very few small papules/pustules; 2 = mild erythema: few small papules/pustules; 3 = moderate erythema: several small or large papules/pustules; 4 = severe erythema: numerous small and/or large papules/pustules) 10 and (2) inflammatory lesions count (ILC), method based on count of the total number of papules and/or pustules lesions.

Instrumental evaluation of erythema degree was performed by erythema‐directed digital photography (EDDP) by VISIA‐CR™ – RBX™ using a 5‐point scale (0 = no erythema; 1 = very mild erythema; 2 = mild erythema; 3 = moderate erythema; 4 = severe erythema).

Tolerability was assessed by a self‐administered questionnaire at week 8 evaluating 5 parameters (erythema, dryness, stinging, burning and itch).

Data were evaluated using Kruskal‐Wallis, non‐parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS version 9.

3. RESULTS

Forty‐four patients (34F/10 M; mean age 46.1 ± 12 years; range age: 18–70 years; IGA median value: 3; EDDP median score: 2; ILC median index: 8) out of 45 enrolled cases completed the study. One patient dropped out for local skin reactions.

At week 8, a significant decrease from baseline of IGA scores (median from 3 at T0 to 1 at T1; p < 0.001) and ILC (median from 8 at T0 to 1 at T1; p < 0.001) was recorded along with a significant reduction of EDDP scores (median from 8 at T0 to 1 at T1; p < 0.001) (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). Local side effects were documented in 1 case only (severe erythema), and product tolerability was rated as excellent in 90% of patients.

Table 1.

Study results

| Assessement | T0 | T1 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | ||

| IGA scores | 3.0 | 2–3 | 1.0 | 1–2 | <0.001 |

| IFL counts | 8.0 | 2–11 | 1.0 | 0–3 | <0.001 |

| EDDP scores | 2.0 | 2–3 | 1.0 | 1–2 | <0.001 |

IGA score: 0 = no erythema, papules and/or pustules, 1 = very mild erythema/very few small papules/pustules; 2 = mild erythema, few small papules/pustule; 3 = mild to moderate erythema, several small or large papules/pustules; 4 = moderate erythema and several papules/pustules (data are expressed as median values).

EDDP score: 0 = no redness; 1 = mild redness; 2 = moderate redness; 3 = severe redness (data are expressed as median values).

Abbreviations: EDDP, Erythema‐Directed Digital Photography; IFL, Inflammatory Lesion; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment.

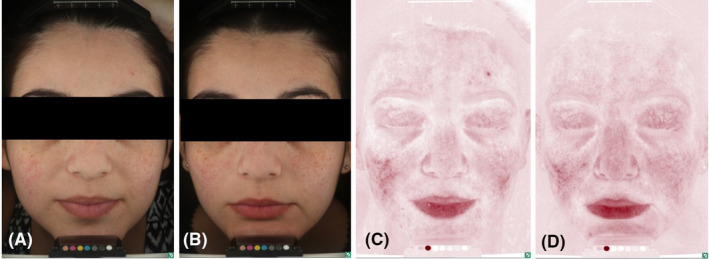

FIGURE 1.

A 19‐year‐old female with a 1‐year history of mild inflammatory rosacea treated with dermocosmetic products. The main reason of consultation was lack of efficacy. Standard (A, B) and erythema‐directed digital photography (C, D) showed after 8 weeks of treatment (B–D) a significant reduction of IGA score (from 2 to 0), papules count (from 4 to 0) and EDDP score (from 2 to 0) from baseline (A–C) (p < 0.001). Treatment response was excellent with minimal residual background erythema. No side effects were recorded

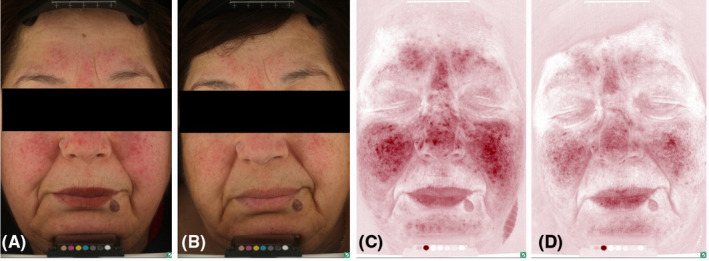

FIGURE 2.

A 66‐year‐old female with a 5‐year history of moderate inflammatory rosacea resistant to previous treatment with a topical metronidazole 1% gel (MTZ) applied twice daily. The main reason of consultation was the poor response and persistent irritation by MTZ. Standard (A, B) and erythema‐directed digital photography (C, D) showed after 8 weeks of treatment (B–D) with the novel azelaic acid formulation a significant reduction of IGA score (from 3 to 1), papules count (from 15 to 3) and EDDP score (from 3 to 1) from baseline (A–C) (p < 0.001). Treatment response was excellent with minimal residual background erythema and telangiectasias. No side effects were recorded

4. DISCUSSION

This multicentre, open‐label prospective trial using clinical and advanced digital photography evaluation indicates that the novel 15% AzA formulation is an efficacious treatment approach for patients with mild‐to‐moderate inflammatory rosacea. The effect of the tested cream may be related to multiple mechanisms of action of its ingredients. In detail, AzA is a saturated, straight‐chain, medium‐length dicarboxylic with anti‐oxidant and anti‐inflammatory properties through the inhibition of neutrophil release of ROS species and downregulation of cathelicidin (LL‐37) via inhibition of kallikrein‐5 (the predominant serine protease able to cleave cathelicidin into LL‐37, its active peptide form responsible of leukocyte chemotaxis, angiogenesis and inflammation), respectively. 11 , 12 Dihydroavenanthramide D is a synthetic analogue of avenanthramides, the active components of oat, with anti‐inflammatory/anti‐itch properties, as demonstrated through the activation of neurokinin‐1 receptor and by the inhibition of mast cell degranulation by in vitro and in vivo studies, respectively. 9

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study suggests that this new topical 15% AzA formulation may represent a valid therapeutic option for mild‐to‐moderate inflammatory rosacea that undoubtedly deserves attention. It may represent a significant adjunct to the therapeutic armamentarium for the management of inflammatory rosacea patients without significant side effects. Finally, it emphasizes the advantages of EDDP system in assisting for a more accurate erythema severity grading evaluation during treatment. Further studies on larger series of rosacea patients are necessary to confirm our finding and results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This study received approval by the local ethical committees.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1269‐1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woo YR, Lim JH, Cho DH, Park HJ. Rosacea: molecular mechanisms and management of a chronic cutaneous inflammatory condition. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(9):1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, van der Linden MM, Charland L. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(4):CD003262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Del Rosso JQ. Azelaic acid topical formulations: differentiation of 15% gel and 15% foam. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(3):37‐40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dall'Oglio F, Verzi AE, Lacarrubba F, Giuffrida G, Milani M, Micali G. Inter‐observer evaluation of erythema‐directed photography for the assessment of erythema and telangiectasias in rosacea. Skin Res Technol. 2020. 10.1111/srt.12979. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dall'Oglio F, Lacarrubba F, Luca M, Boscaglia S, Micali G. Clinical and erythema‐directed imaging evaluation of papulo‐pustular rosacea with topical ivermectin: a 32 weeks duration study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(7):703‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Verzì AE, Luppino I, Bhatt K, Lacarrubba F. Treatment of erythemato‐telangiectatic rosacea with brimonidine alone or combined with vascular laser based on preliminary instrumental evaluation of the vascular component. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(6):1397‐1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Micali G, Gerber PA, Lacarrubba F, Schäfer G. Improving treatment of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea with laser and/or topical therapy through enhanced discrimination of its clinical features. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(7):30‐39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lotts T, Agelopoulos K, Phan NQ, et al. Dihydroavenanthramide D inhibits mast cell degranulation and exhibits anti‐inflammatory effects through the activation of neurokinin‐1 receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(8):739‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stein L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin 1% cream in treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of two randomized, double‐blind, vehicle‐controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(3):316‐323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulte BC, Wu W, Rosen T. Azelaic acid: evidence‐based update on mechanism of action and clinical application. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(9):964‐968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dall’Oglio F, Nasca MR, Micali G. Emerging topical drugs for the treatment of rosacea. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2021;18:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]