Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep related breathing disorder characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airways leading to intermittent hypoxia and sleep disruption. Clinically relevant neurocognitive, metabolic and cardiovascular disease often occurs in OSA. Systemic hypertension, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cerebral vascular infarctions and atrial fibrillation are among the most often cited conditions with causal connections to OSA. Emerging science suggest that untreated and undertreated OSA increases the risk of developing cognitive impairment, including vascular dementia and neurodegenerative disorders, like Alzheimer’s disease. As with OSA, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the incidence of dementia increases with age. Given our rapidly aging population, dementia prevalence will significantly increase. The aim of this treatise is to review current literature linking OSA to dementia and explore putative mechanisms by which OSA might facilitate the development and progression of dementia.

Keywords: Cognitive, Comorbidities, Dementia, Obstructive sleep apnea

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common, chronic disorder of sleep and breathing characterized by partial or complete occlusion of the upper airway during sleep leading to insufficient airflow, hypoxemia and sleep fragmentation.1 Consequently, daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, irritability, diminished concentration and fatigue are common in OSA.2 The prevalence of OSA is increasing, now affecting 20%-30% of males and 10%–15% of females in the USA.3 Curiously, OSA is more common in selected populations (i.e. Hispanic, African American, Asian), in cases evaluated for bariatric surgery (70%-80%),4 and in cerebrovascular disease (60%-70%).5,6 Mokhlesi et al.7 queried the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database between 2003–2012 and identified 1,704,905 OSA patient insurance claims and compared these to 1,704,417 matched controls to determine the burden of OSA associated comorbidities. The investigators found all comorbid conditions were of significantly greater prevalence in the OSA group. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and ischemic heart disease were more prevalent in men, as opposed to hypertension and depression in women with OSA. Others describe increase risk of neurocognitive impairment and death in OSA.8 In spite of increasing prevalence and increasing well-defined health risks, estimates are that less than 5% of US adults with OSA are treated.9,10

There is evidence to support the notion that OSA plays a causal or facilitating role in conditions often associated with impaired cognition, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) (Table 1).11,12 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), neuropsychiatric disorders and stroke have also been associated with OSA.13 The mechanism by which OSA alters cognition are poorly defined and may be dependent on individual phenotype and disease specific factors. As an example, evidence supports OSA activation of the sympathetic, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system as a putative mediator of OSA induced brain hypoperfusion and subsequent VaD.14 Additionally, OSA was demonstrated responsible for AD cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) biomarker changes in β-amyliod42 in the elderly, an indication that OSA may alter β-amyliod42 metabolism promoting amyloid plaques.15 Elucidating mechanisms by which OSA creates cognitive impairment might allow disease specific therapeutic targets with promise of improved neural endpoints.

Table 1:

Conditions Associated with Cognitive Impairment and OSA

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (intracranial bleeding, cerebrovascular ischemia) (28) |

| Arrhythmia (hypoperfusion, thromboembolic cerebral ischemia) (31) |

| Endocrine disorders (Hypothyroidism, T2DM, Dyslipidemia) (38) |

| Psychiatric disorders (MDD, anxiety)(42) |

| Neurodegenerative disorders: AD, LBD, Parkinson’s disease, and frontotemporal degeneration (73) |

T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; MDD, Major depressive disorder; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LBD, Lewy- body dementia

OSA Comorbidities and Altered Cognition: Potential Mechanisms

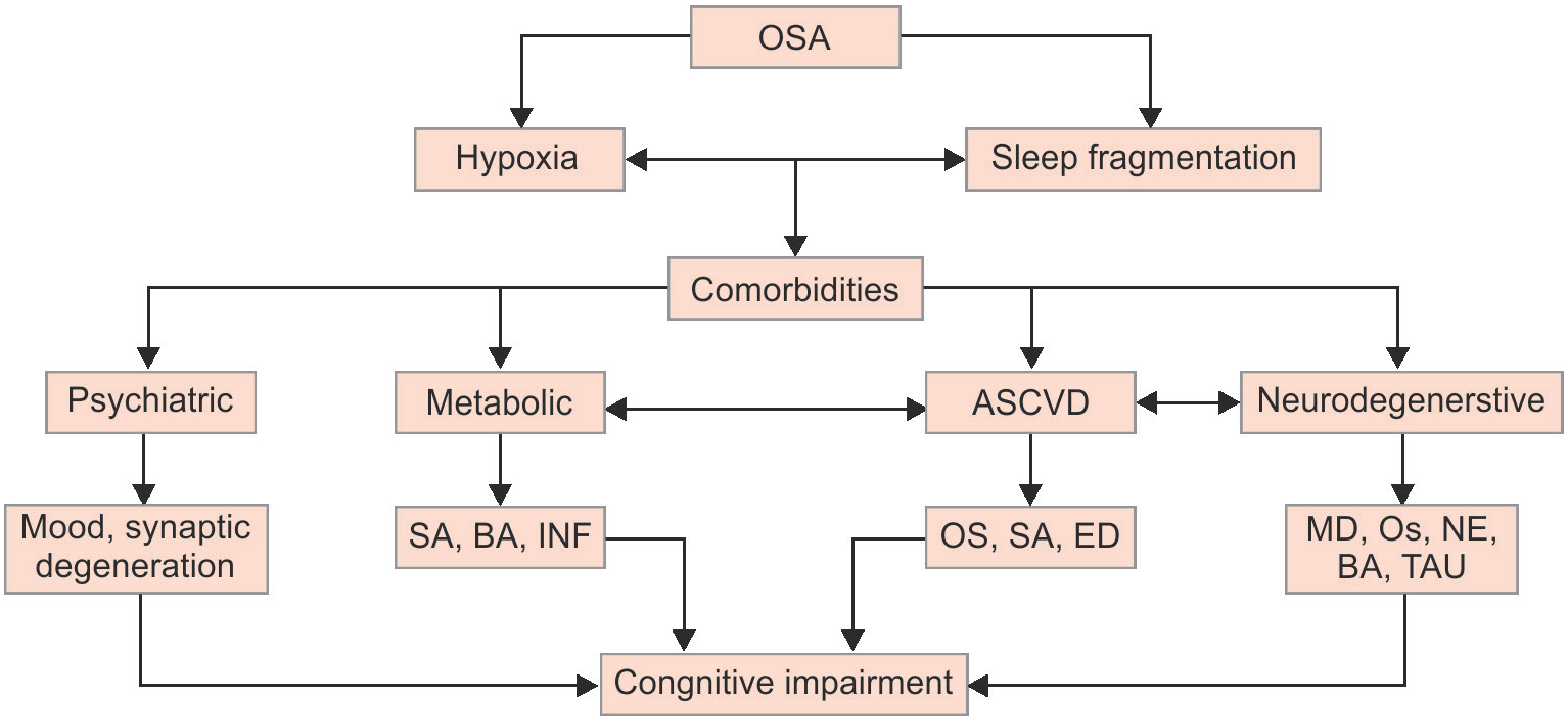

Hypoxemia, sleep fragmentation and daytime sleepiness are major contributors to cognitive impairment in OSA, affecting executive functions, attention, memory and vigilance.16 In general, hypoxemia and sleep fragmentation, affect memory, attention and executive functions, mainly by causing neuronal injury in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.17 However, OSA comorbidities likely affect cognitive throughput by alternative diverse mechanisms. Some comorbidities, such as atrial fibrillation related cerebral infarction, impair cognition through reasonably well elucidated pathways, namely embolic stroke. Conversely, the mechanism by which other OSA comorbidities (endocrinopathies, hypertension, psychiatric disorders, lipid disarrangement, etc.) impair cognitive function is speculative and a subject of robust scientific interest. Flowchart 1 illustrates the proposed mechanisms by which selected OSA comorbidities adversely affect neuronal health and impair cognition. In the lines that follow, we succinctly review conditions comorbid with OSA known to impair cognition and describe the proposed mechanisms of action.

Flowchart 1: Proposed mechanisms by which OSA impairs cognition.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; SA, sympathomimetic activation; INF, inflammation; BA, beta amyloid accumulation; OS, oxidative stress; ED, endothelial dysfunction; MD, myelin decrease; NE, neural excitability, reduced; TAU, Tau hyperphosphorylation

Cardiovascular disease and Stroke:

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and worldwide. Subjects afflicted with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease have a higher incidence of OSA1 and cognitive dysfunction.18 Furthermore, cardiovascular disease and OSA, share other common comorbid conditions, such as obesity and endocrinopathies, conditions that are independently associated with decreased cognition.11

Prospective studies have established that sleep apnea increases mortality, incident stroke and cardiovascular disease.19–23 Long term follow up of both the Sleep Heart Health Study and the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort show nearly 3–4 fold higher associations between baseline OSA and incident stroke.24,25 Multiple studies describe a stroke risk in OSA of similar magnitude to vascular risk factors, such as hypertension and obesity.24–26

OSA may mediate vascular cerebral injury via intermittent deoxygenation-reoxygenation induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction and metabolic deregulation.27 Similarly, arousals may induce vascular disease risk through cerebral hypoperfusion, altered cerebral autoregulation, impaired endothelial function and increased inflammation.28–30

Atrial fibrillation, a cardiac rhythm disturbance that predisposes to thromboembolic cerebral ischemia, occurs in 32–49% of subjects afflicted with OSA.31 Indeed, patients with atrial fibrillation have a 4–5 fold increase in incident stroke without systemic anticoagulation.32 Experimentally induced obstructive apnea can cause acute atrial fibrillation in a healthy canine heart.33 Additionally, there is evidence that positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment of OSA protect against recurrence of atrial fibrillation following successful cardioversion in subjects afflicted with both conditions.34

Endocrine disorders, Diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM):

OSA and T2DM share several risk factors such as obesity and age. However, there is experimental evidence that the relationship between OSA and T2DM is bidirectional and independent of obesity.35 Experimentally induced short-term sleep loss and intermittent hypoxemia in normal subjects promote insulin resistance with associated elevated systemic insulin levels and higher blood glucose.36 Withdrawal of experimental sleep loss or treatment of non-obese OSA insulin resistant subjects with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) results in resolution of insulin resistance.37

Excess insulin is a major contributor to neurocognitive decline in T2DM. Insulin degrading enzyme functions to reduce excess extracellular insulin and clear β-amyloid. Excessive insulin levels compete with the binding site of the insulin degrading enzyme, increasing the amount of β-amyloid, thereby, theoretically, facilitating Alzheimer’s disease.38

Independent of compounding variables, insulin resistant subjects have endothelial dysfunction as evidenced by resistance to insulin’s effect on endothelium-mediated vasodilatation.39 Endothelial dysfunction may promote neuronal injury by vascular dysregulation and ischemia.

Psychiatric disorders, Major depressive disorder (MDD):

Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between OSA and depression.40 Sleep complaints, weight gain, poor concentration, fatigue and anhedonia are features common to major depressive disorders (MDD) and OSA. It has been established that OSA patients are more prone to MDD than the general population.41 Effective CPAP treatment of OSA in MDD reduced anxiety and depression and improved neurocognitive function.42 The exact mechanism by which treating OSA improves cognitive function in patients with MDD remains speculative. Improving sleep architecture and oxygenation with subsequent improvement in alertness and quality of life after CPAP treatment of OSA might play a mechanistic role in cognitive benefits achieved after CPAP treatment.34

Neurodegenerative disorders:

Dementia is a growing problem as populations’ age worldwide. The cost of treating dementia in the US alone was estimated to be between $157 and $215 billion dollars in 2010.43 The rise in dementia with its associated morbidities creates hardship on caregivers,44 threatens the economic health of families and adds significantly to the cost of the healthcare system.45 Unfortunately, treatment studies targeting β-amyloid have not consistently ameliorated dementia risk.46 Emerging animal and human data indicate that frequent sleep disruptions and curtailed sleep increase synaptic activity and decrease glymphatic clearance leading to β-amyloid and tau deposition. Hence proper sleep may protect against neurodegeneration and AD,45,47,48 especially in individuals with genetic risks for dementia.49–52

Several studies have found cross-sectional associations between sleep disturbances and worse neurocognitive function,53,54 while others have not.55–57 Evidence from few prospective studies in older non-Hispanic white adults supports longitudinal associations between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease related disorders (ADRD)21,58,59 Notably, hypoxemia, but not sleep fragmentation, mediated these associations.15,59 The underlying mechanisms linking OSA to cognitive decline in ADRD are unclear and may be multifactorial. One established framework suggests that hypoxemia accelerates cognitive aging; or OSA exerts damage through cerebrovascular disease.

Of interest, brain hypoperfusion, as seen in OSA, has been associated to pathological processes involved in AD.60–66 Moreover, chronic hypoxemia promotes the progression of cerebral small vessel disease, resulting in lacunar infarcts, white matter lesions, white matter fiber tract abnormalities, and gray-matter loss. Most notably, oxygen desaturation has been associated with an increased risk in developing MCI, perhaps as a prodromal phase to AD. Therefore, OSA patients may experience earlier onset of MCI and AD.54,67–70

Anatomically, certain regions of the brain, such as the prefrontal and frontal lobes and hippocampus,17 are notably vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic injury, Given the many deleterious effects associated with hypoperfusion in OSA, further studies looking at the relationships between hypoperfusion, early brain matter loss, and cognitive decline are needed to help clarify any contributions OSA may have to the onset and progression of AD.71

In a recent study, Baril et al.72 demonstrated alterations in selected cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers common to both OSA and AD (Table 2). Biomarkers linked to β-amyloid, tau proteins, cytokines, acute-phase proteins, homocysteine, oxidative stress markers, and clusterin, seem to be able to identify adults with OSA at risk for dementias.72 Although a single biomarker of dementia risk in OSA has not been identified, biomarker combinations offer promise in selecting OSA cases at greatest risk for neurodegeneration. Further, serum or CSF biomarker responses to CPAP treatment of OSA might serve as surrogates of disease progression. Undeniably, methods that reliably predict neurodegeneration or progression of cognitive dysfunction will facilitate earlier clinical intervention and personalized treatment approaches, thereby, potentially reducing dementia burden.

Table 2:

Shared blood fluid biomarkers of dementia and obstructive sleep apnea

| Tau proteins | Increased74,75 |

| Cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) | Increased76,77 |

| Acute-phase proteins (hsCRP, ACT) | Increased76,78 |

| Homocysteine | Increased76,79 |

| Superoxide dismutase | Decreased80,81 |

| MDA/8-OHdg | Increased80,81 |

| Clusterin | Increased82,83 |

IL-6, Interleukin-6; IL-1b, Interleukin −1β; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor a; hsCRP, high sensitivity c-reactive protein; ACT, α1-antichymotripsin, MDA/8-OHdg, malondialdehyde; 8-OHdg, 8-hydroxy-2- desoxyguanosine

Conclusion

OSA is a treatable chronic sleep disorder wherein recurrent episodes of complete or partial upper airway obstruction during sleep promote hypoxemia, hypercapnia, sleep fragmentation, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Adverse effects of untreated OSA include psychiatric, metabolic, cardiovascular and neurocognitive risk. Recently, science has established OSA as an independent risk factor for dementia. Given that the sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia of OSA is readily reversed with CPAP therapy, identification and treatment of OSA in some cognitively impaired subjects should improve neural health outcomes. This manuscript highlights proposed mechanisms by which OSA negatively affects cognition and propagates neuronal injury culminating in dementia. Understanding the potential mechanisms that increase risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in OSA should facilitate the identification of clinical and/or biochemical phenotypes with highest propensity for dementia and, thereby, target these cases for early preventative strategies to reduce risk of dementia.

Acknowledgments

Source of support: Nil

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Contributor Information

Pamela Barletta, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Alexandre R Abreu, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Alberto R Ramos, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Neurology, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Salim I Dib, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Neurology, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Carlos Torre, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Alejandro D Chediak, Sleep Disorders Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

References

- 1.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antic NA, Catcheside P, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34(1):111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malhotra A, White DP. Obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravesloot MJ, van Maanen JP, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is underrecognized and underdiagnosed in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;269(7):1865–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slowik JM, Collen JF. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson KG, Johnson DC. Frequency of Sleep Apnea in Stroke and TIA Patients: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2010;6(2):131–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokhlesi B, Ham SA, et al. The effect of sex and age on the comorbidity burden of OSA: an observational analysis from a large nationwide US health claims database. The European respiratory journal. 2016;47(4):1162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies CR, Harrington JJ. Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Neurocognitive Function and Impact of Continuous Positive Air Pressure. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(3):287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redline S. Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Implications for the Sleep Health of the Population. JAMA. 2017;317(4):368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;189(3):335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: role of the metabolic syndrome and its components. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2008;4(3):261–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutsey PL, Misialek JR, et al. Sleep characteristics and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(2):157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenzweig I, Williams SC, et al. The impact of sleep and hypoxia on the brain: potential mechanisms for the effects of obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20(6):565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Torre JC. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;2012:367516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osorio RS, Gumb T, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology. 2015;84(19):1964–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson ML, Howard ME, et al. Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. Progress in brain research. 2011;190:53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair D, Zhang SX, et al. Sleep fragmentation induces cognitive deficits via nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-dependent pathways in mouse. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184(11):1305–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deckers K, Schievink SHJ, et al. Coronary heart disease and risk for cognitive impairment or dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackwell T, Yaffe K, et al. Associations between sleep-disordered breathing, nocturnal hypoxemia, and subsequent cognitive decline in older community-dwelling men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin MS, Sforza E, et al. , group Ps. Sleep breathing disorders and cognitive function in the elderly: an 8-year follow-up study. the proof-synapse cohort. Sleep. 2015;38(2):179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA. 2011;306(6):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaggi HK, Concato J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munoz R, Duran-Cantolla J, et al. Severe sleep apnea and risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37(9):2317–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arzt M, Young T, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing and the occurrence of stroke. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172(11):1447–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redline S, Yenokyan G, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182(2):269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polsek D, Gildeh N, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea and Alzheimer’s disease: In search of shared pathomechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;86:142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sforza E, Roche F. Sleep apnea syndrome and cognition. Front Neurol. 2012;3:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeboah J, Redline S, et al. Association between sleep apnea, snoring, incident cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in an adult population: MESA. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):963–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinchuk AV, Gentry MJ, et al. Phenotypes in obstructive sleep apnea: A definition, examples and evolution of approaches. Sleep Med Rev. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szymanski FM, Platek AE, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with atrial fibrillation: prevalence, determinants and clinical characteristics of patients in Polish population. Kardiol Pol. 2014;72(8):716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIntyre WF, Healey J. Stroke Prevention for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Beyond the Guidelines. J Atr Fibrillation. 2017;9(6):1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu L, Li X, et al. Atrial Fibrillation in Acute Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Autonomic Nervous Mechanism and Modulation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tung P, Anter E. Atrial Fibrillation And Sleep Apnea: Considerations For A Dual Epidemic. J Atr Fibrillation. 2016;8(6):1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tassone F, Lanfranco F, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome impairs insulin sensitivity independently of anthropometric variables. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59(3):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamatakis KA, Punjabi NM. Effects of sleep fragmentation on glucose metabolism in normal subjects. Chest. 2010;137(1):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harsch IA, Schahin SP, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment rapidly improves insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(2):156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craft S, Cholerton B, et al. Insulin and Alzheimer’s disease: untangling the web. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33 Suppl 1:S263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinberg HO, Chaker H, et al. Obesity/insulin resistance is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Implications for the syndrome of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(11):2601–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wheaton AG, Perry GS, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and depression among U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2008. Sleep. 2012;35(4):461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ejaz SM, Khawaja IS, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(8):17–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ponce S, Pastor E, et al. The role of CPAP treatment in elderly patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea. A Multicenter Randomised Controlled Trial. The European respiratory journal. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hurd MD, Martorell P, et al. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.As Assoc. 2018 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures (vol 14, pg 367, 2018). Alzheimers & Dementia. 2018;14(5):701-. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yaffe K, Falvey CM, et al. Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(10):1017–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corriveau RA, Koroshetz WJ, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease—Related Dementias Summit 2016: National research priorities. Neurology. 2017;89(23):2381–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi L, Chen SJ, et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Auerbach S, Yaffe K. The link between sleep-disordered breathing and cognition in the elderly: New opportunities? Neurology. 2017;88(5):424–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Meco A, Joshi YB, et al. Sleep deprivation impairs memory, tau metabolism, and synaptic integrity of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles. Neurobiology of aging. 2014;35(8):1813–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim AS, Kowgier M, et al. Sleep Fragmentation and the Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline in Older Persons. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1027–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montplaisir J, Petit D, et al. Sleep in alzheimer’s disease: further considerations on the role of brainstem and forebrain cholinergic populations in sleep-wake mechanisms. Sleep. 1995;18(3):145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prinz PN, Vitaliano PP, et al. Sleep, EEG and mental function changes in senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Neurobiology of aging. 1982;3(4):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Djonlagic I, Guo M, Matteis P, et al. Untreated sleep-disordered breathing: links to aging-related decline in sleep-dependent memory consolidation. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramos AR, Tarraf W, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and neurocognitive function in a Hispanic/Latino population. Neurology. 2015;84(4):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blackwell T, Yaffe K, et al. Associations between sleep architecture and sleep-disordered breathing and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2217–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foley DJ, Masaki K, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cognitive impairment in elderly Japanese-American men. Sleep. 2003;26(5):596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sforza E, Roche F, et al. Cognitive function and sleep related breathing disorders in a healthy elderly population: the SYNAPSE study. Sleep. 2010;33(4):515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen-Zion M, Stepnowsky C, et al. Cognitive changes and sleep disordered breathing in elderly: differences in race. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. Jama. 2011;306(6):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bokura H, Kobayashi S, et al. Silent brain infarction and subcortical white matter lesions increase the risk of stroke and mortality: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;15(2):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Culebras A. Sleep and stroke. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(4):438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dib S, Ramos AR, et al. Sleep and stroke. Periodicum biologorum. 2012;114(3):369–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haan MN, Mungas DM, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harbison J, Gibson GJ, et al. White matter disease and sleep-disordered breathing after acute stroke. Neurology. 2003;61(7):959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramos AR, Gangwisch JE. Is sleep duration a risk factor for stroke? Neurology. 2015;84(11):1066–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramos AR, Seixas A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and stroke: links to health disparities. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):244–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daulatzai MA. Evidence of neurodegeneration in obstructive sleep apnea: Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93(12):1778–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daulatzai MA. Cerebral hypoperfusion and glucose hypometabolism: Key pathophysiological modulators promote neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, et al. Neurocognitive function among middle-aged and older Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30(1):68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wennberg AMV, Wu MN, et al. Sleep Disturbance, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Review. Semin Neurol. 2017;37(4):395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farias ST, Mungas D, et al. Everyday functioning in relation to cognitive functioning and neuroimaging in community-dwelling Hispanic and non-Hispanic older adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(3):342–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baril AA, Carrier J, et al. Biomarkers of dementia in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;42:139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi L, Chen SJ, et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baird AL, Westwood S, et al. Blood-Based Proteomic Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Front Neurol. 2015;6:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Motamedi V, Kanefsky R, et al. Elevated tau and interleukin-6 concentrations in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2018;43:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lai KSP, Liu CS, et al. Peripheral inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 175 studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(10):876–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Q, Zheng X. Tumor necrosis factor alpha is a promising circulating biomarker for the development of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(16):27616–27626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nadeem R, Molnar J, et al. Serum inflammatory markers in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(10):1003–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Niu X, Chen X, et al. The differences in homocysteine level between obstructive sleep apnea patients and controls: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia-Blanco A, Baquero M, et al. Potential oxidative stress biomarkers of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Sci. 2017;373:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou L, Chen P, et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Neurocognitive Dysfunction of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:9626831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peng Y, Zhou L, et al. Relation between serum leptin levels, lipid profiles and neurocognitive deficits in Chinese OSAHS patients. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(11):981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koch M, Jensen MK. HDL-cholesterol and apolipoproteins in relation to dementia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27(1):76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]