Abstract

Background Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) are at increased risk of developing gastric adenomas. There is limited understanding of their clinical course and no consensus on management. We reviewed the management of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP from two centers.

Methods Patients with FAP and histologically confirmed gastric adenomas were identified between 1997 and 2018. Patient demographics, adenoma characteristics, and management/surveillance outcomes were collected.

Results Of 726 patients with FAP, 104 (14 %; 49 female) were diagnosed with gastric adenomas at a median age of 47 years (range 19 – 80). The median size of gastric adenomas was 6 mm (range 1.5 – 50); 64 (62 %) patients had adenomas located distally to the incisura. Five patients (5 %) had gastric adenomas demonstrating high-grade dysplasia (HGD) on initial diagnosis, distributed equally within the stomach. The risk of HGD was associated with adenoma size ( P = 0.04). Of adenomas > 20 mm, 33 % contained HGD. Two patients had gastric cancer at initial gastric adenoma diagnosis. A total of 63 patients (61 %) underwent endoscopic therapy for gastric adenomas. Complications occurred in three patients (5 %) and two (3 %) had recurrence, all following piecemeal resection of large (30 – 50 mm) lesions. Three patients were diagnosed with gastric cancer at median follow-up of 66 months (range 66 – 115) after initial diagnosis.

Conclusions We observed gastric adenomas in 14 % of patients with FAP. Of these, 5 % contained HGD; risk of HGD correlated with adenoma size. Endoscopic resection was feasible, with few complications and low recurrence rates, but did not completely eliminate the cancer risk.

Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a rare autosomal dominant inherited cancer-susceptibility syndrome caused by constitutional pathogenic variant in the APC gene 1 . Patients have an almost 100 % risk of colorectal cancer by the age of 40 in the absence of prophylactic colectomy 2 . With screening and surveillance, mortality from colorectal cancer has improved, and long-term survival is increasingly determined by extracolonic manifestations including duodenal cancer and desmoid disease 3 4 5 .

Gastric adenomas and cancer are increasingly recognized as a clinical problem in FAP 6 7 8 . Historical data are difficult to interpret, but it has been suggested that in Western countries there is no increased risk of gastric cancer in patients with FAP 9 . This conflicts with data from Korea and Japan, where an increased risk of gastric cancer has been demonstrated in patients with FAP, over and above the higher background gastric cancer rates in those countries 10 11 12 . Furthermore, data from those countries have also suggested a much higher incidence of gastric adenomas in FAP than has been observed in the West.

Identifying lesions with neoplastic potential is challenging 13 14 15 16 . A recent series describing gastric cancer in FAP in Western countries has highlighted that gastric cancer is more likely to be proximal and associated with carpeting fundic gland polyposis, which makes identification of premalignant gastric adenomas difficult 6 7 8 . In addition, the prognosis was poor, with many having advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, again perhaps highlighting the difficulty in identifying and managing the benign precursor adenoma.

Gastric adenomas in patients with FAP are considered to be premalignant lesions, with studies showing that up to 14 % contain high-grade dysplasia (HGD) 6 17 . However, although the removal of suspicious gastric lesions might prevent progression to adenocarcinoma, specific guidance on the management and surveillance of gastric lesions in patients with FAP is lacking 13 . We aimed to describe the prevalence, characteristics, and our experience on the management of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP, combining data from two European polyposis registries.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of all patients with FAP and histologically confirmed gastric adenomas diagnosed between March 1997 and May 2018, which were identified from prospectively maintained polyposis registries at St. Mark’s Hospital, London, and the Amsterdam UMC, Academic Medical Center. The work was approved by the research department from each institution.

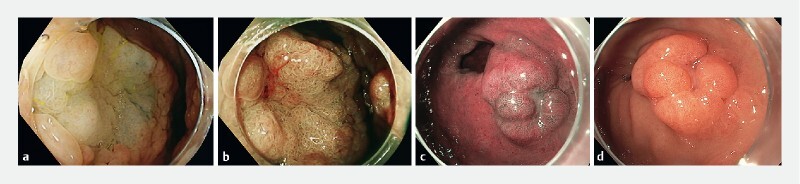

All patients with a histological diagnosis of gastric adenoma were included. All patients with FAP aged over 25 years underwent upper gastrointestinal screening endoscopy with surveillance intervals determined by Spigelman Classification Score, which assesses the severity of duodenal disease based on clinical and pathological features. These endoscopies were performed using white-light endoscopy and, if available and needed, virtual chromoendoscopy was used for lesion characterization ( Fig. 1 ). There was no standardized surveillance protocol in place for the treatment or follow-up of gastric adenomas.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic appearances of gastric adenomas. a Proximal adenoma (high definition image with white light). b Proximal adenoma (high definition image with flexible spectral imaging color enhancement). c Distal antral adenoma (white-light imaging). d Distal antral adenoma (high definition images with narrow-band imaging).

Patients’ medical notes, and endoscopy and pathology reports were obtained and reviewed. Patient demographics, APC mutation (including clinical diagnoses of FAP without an identified mutation), adenoma location, histology, intervention, and follow-up outcomes up to June 2020 were collected. Gastric adenomas were classified as proximal (incisura, body fundus, and cardia) or distal (antrum and pylorus). Recurrence was defined as adenomas reoccurring at the same site or scar.

Fisher’s exact test was applied to assess the statistical significance of adenoma size and categorical variables and HGD.

Results

In total, 726 patients with FAP were identified from hospital databases, of whom 104 (14 %) were diagnosed with a gastric adenoma (see Fig. 1 s in the online-only supplementary material). A total of 49 patients (47 %) were female and the median age at diagnosis of gastric adenoma was 47 years (range 19 – 80 years), with a median follow-up of 37 months (range 0 – 242 months) ( Table 1 s ). The median size of gastric adenoma was 6 mm (range 1.5 – 50 mm), and the majority (n = 64; 62 %) were located distal to the incisura. Fundic gland polyps were present at initial diagnosis of gastric adenoma in 83 % of patients. Helicobacter pylori status was available for 41 patients (39 %) at diagnosis of gastric adenoma (3 [7 %] positive and 38 [93 %] negative).

Five (three female) out of 104 patients (5 %) demonstrated HGD at primary diagnosis of the gastric adenoma ( Table 1 ), with a median polyp size of 25 mm (range 7 – 50 mm). All lesions containing HGD were resected endoscopically. Two patients had a recurrence following endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR); one underwent a repeat EMR and histology demonstrated LGD. The other underwent a subtotal gastrectomy, and postoperative histology revealed an unexpected adenocarcinoma (T4 N1); the patient died from recurrent gastric cancer 2 years later.

Table 1. Main features of gastric adenomas demonstrating high and low grade dysplasia.

| < 5 mm | 5 – 20 mm | > 20 mm | Not classified | Total 1 | |

| HGD (resected) | |||||

| Total | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 0 | 43 | 51 | 73 | – |

| Sex | |||||

|

0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

|

0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Location relative to incisura | |||||

|

0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

|

0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Multiplicity | |||||

|

0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

|

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Intervention | |||||

|

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

|

0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Recurrence 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Complications 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deceased 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| LGD (resected) | |||||

| Total | 16 | 24 | 3 | 15 | 58 |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 44 | 46 | 52 | 50 | – |

| Sex | |||||

|

7 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 24 |

|

9 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 34 |

| Location relative to incisura | |||||

|

4 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 24 |

|

11 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 31 |

|

1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

|

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Multiplicity | |||||

|

8 | 17 | 0 | 5 | 30 |

|

8 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 26 |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Intervention | |||||

|

1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

|

12 | 15 | 1 | 12 | 40 |

|

1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

|

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

|

0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

|

0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Recurrence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Complications 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Deceased 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| LGD (biopsy only) | |||||

| Total | 6 | 8 | 1 | 25 | 40 |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 38 | 38 | 45 | 52 | – |

| Sex | |||||

|

4 | 3 | 0 | 14 | 21 |

|

2 | 5 | 1 | 11 | 19 |

| Location | |||||

|

1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

|

5 | 6 | 0 | 20 | 31 |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Multiplicity | |||||

|

3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 18 |

|

3 | 6 | 0 | 13 | 22 |

| Recurrence 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reasons for no further intervention | |||||

|

Follow-up endoscopy – no evidence of adenoma | 6 | 20 | ||

| Follow-up endoscopy – repeat biopsy | 7 | ||||

| Follow-up endoscopy – repeat biopsy and new gastric adenoma biopsied or resected | 7 | ||||

|

For pancreas-preserving duodenectomy for advanced duodenal disease | 2 | |||

| For small-bowel transplant for advanced pouch disease having had a previous pancreas-preserving duodenectomy | 1 | ||||

| Deceased 8 | 3 | ||||

| Lost to follow-up | 14 | ||||

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection.

All data are number of patients, except where indicated.

One patient diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma did not undergo intervention and died during follow-up; this patient is not included in the table.

One patient proceeded to subtotal gastrectomy and died of metastatic gastric cancer 2 years after surgery (recurrence at scar); one patient underwent a repeat EMR/ESD and histology demonstrated LGD only

Pain requiring overnight admission and observation following EMR of 30-mm proximal lesion.

Metastatic gastric cancer following recurrence after subtotal gastrectomy.

Bleeding requiring transfusion and endoscopic intervention following ESD of 18-mm distal lesion; pain requiring overnight admission and observation following removal of 20-mm distal lesion.

Gastric small cell cancer 1 year following EMR of 20-mm lesion; biliary sepsis; gastrointestinal bleed of unknown origin.

Unreliable data due to loss to follow-up.

Desmoid disease; metastatic liver disease associated with tumor of unknown origin; old age, acute on chronic kidney failure and metabolic acidosis, associated with diabetes and vascular dementia.

The risk of HGD on initial diagnosis was associated with adenoma size ( P = 0.04): median adenoma size was 25 mm in patients with HGD and 6 mm in patients with LGD. Gastric adenomas > 20 mm had a 33 % risk of harboring HGD compared with 4 % in adenomas ≤ 20 mm ( P = 0.04). HGD was not associated with sex (6 % female vs. 4 % male; P = 0.30) or location (8 % proximal stomach vs. 3 % distal; P = 0.17) ( Table 2 s ).

A total of 98 patients (45 female) developed gastric adenomas demonstrating LGD at the index diagnosis of adenoma ( Table 1 ). Of these, 62 patients had adenomas located distal to the incisura, of which 37 demonstrated multiplicity; 32 patients had adenomas located in the proximal stomach of which 10 had multiple adenomas. Four lesions > 20 mm were all located in the proximal stomach and all demonstrated multiplicity. A total of 58 patients (59 %) with lesions containing LGD underwent endoscopic therapy, as follows: 40 EMR, 4 endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), 2 argon plasma coagulation (APC), 1 ESD and knife-assisted EMR, 1 knife-assisted EMR, 9 snare polypectomy, and 1 cold biopsy (until removed).

Five patients were diagnosed with gastric carcinoma (median age 60 years, range 50 – 73 years). Two were diagnosed with gastric carcinoma at the same time as index gastric adenoma diagnosis. During surveillance after intervention for gastric adenomas, gastric carcinoma was diagnosed in three patients (median time from initial diagnosis of gastric adenoma to cancer 66 months, range 66 – 115 years) ( Table 3 s ).

A total of 63 patients (61 %) underwent interventions for gastric adenomas ( Table 1 ) for lesions ranging from 1.5 mm to 50 mm (size of adenoma was not available for 42 patients [67 %]). Of these patients, 43 underwent EMR, 5 underwent ESD, and 15 had other interventions ( Table 1 ).

Complications occurred in three patients (5 %) who underwent endoscopic therapy, with one requiring reintervention for bleeding at the polypectomy site and two requiring unplanned overnight admission for analgesia and observation post-intervention. There were no cases of perforation following endoscopic therapy, no patient required surgical intervention, and there was no procedure-related mortality.

Two patients (3 %) developed an adenoma recurrence following endoscopic therapy. Both recurrences were in patients who had previously undergone EMR for proximal gastric adenomas measuring 30 mm and 50 mm, respectively, where the index histology demonstrated focal HGD. One patient, aged 60 years, proceeded to surgery (subtotal gastrectomy) where histology confirmed the presence of adenocarcinoma (T4 N1); the patient died 2 years later from recurrence of gastric cancer. The other patient underwent further endoscopic therapy by EMR and is currently alive and free from cancer.

Of the 104 patients with known gastric adenomas, 8 died during follow-up, of whom 3 were diagnosed with metastatic gastric carcinoma: one had undergone previous EMR for gastric adenomas demonstrating LGD, another was diagnosed with HGD in their primary gastric adenoma, and one had a recurrence following a subtotal gastrectomy for an adenoma with HGD that was suspicious for malignancy. Five died from causes unrelated to gastric disease including desmoid disease, metastatic liver disease associated with a tumor of unknown origin, biliary sepsis, gastrointestinal bleed of unknown origin, and old age with multiple comorbidities. A total of 14 patients were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

By combining data from St. Mark’s and Amsterdam UMC, we were able to evaluate the largest series of gastric adenomas in a FAP cohort to date. Gastric adenomas were present in 14 % of patients with FAP, compared with 9 % – 50 % in similar studies 17 18 19 . The studies showing higher incidence were from Asia and may reflect the higher background incidence of gastric disease in Asian populations. However, it is important to note that detection of proximal gastric adenomas can be challenging, particularly in the presence of gastric fundic gland polyposis. Given the historical nature of the data, along with advances in our understanding of gastric pathology and improvement in endoscopic systems, it is likely that the true incidence is higher than that observed in our study.

In the absence of standardized guidance, 63 patients (61 %) underwent excision or ablation for gastric adenomas. Of patients who did not undergo intervention based on histology from endoscopic biopsies, none developed gastric carcinoma. However endoscopic intervention did not eradicate cancer risk and three patients developed gastric carcinoma after gastric adenoma resection. Endoscopic resection is considered safe with a low rate of recurrence (3 %) and complications (5 %).

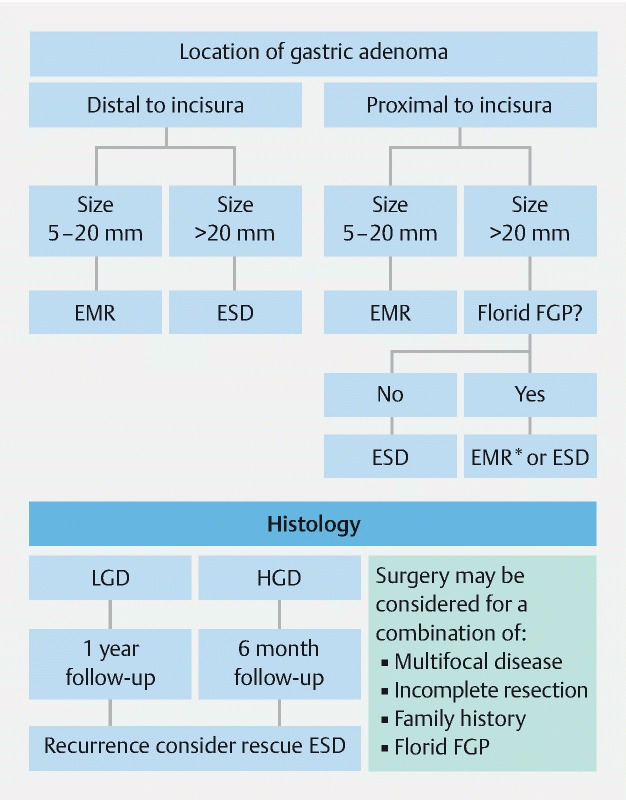

In current practice, an optical diagnosis of gastric adenoma is preferred and routine biopsy is avoided due to the risk of fibrosis, which may render definitive endoscopic therapy impossible. If feasible, direct resection is advised but in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, or if there is a suspicion of malignancy, biopsies can be taken. For large adenomas, a separate endoscopy session can be scheduled at a later date following appropriate informed consent. There are no optical diagnostic features validated for HGD but given that HGD was not observed in adenomas of ≤ 5 mm, it would seem reasonable to use size of adenoma as an indication for endoscopic therapy. Our current approach for the management of gastric adenomas is shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Current local protocol for management of gastric adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR*, knife-assisted EMR; FGP, fundic gland polyposis.

Overall, 5 % of gastric adenomas had HGD, which is consistent with previous studies 6 17 and supports the concept that these adenomas are premalignant polyps that require intervention. Our analysis demonstrated a statistically significant association between size of adenoma and HGD ( P = 0.04), where median adenoma size was 25 mm in patients with HGD compared with 6 mm in patients without HGD. This builds on the previous work by Walton et al. to demonstrate that adenomas with HGD tend to be larger in size (7 – 50 mm) 6 .

Furthermore, a recent paper by Leone et al. reported that gastric cancers in patients with FAP was associated with solitary or “polypoid mound” polyps > 20 mm located in the proximal stomach 7 . Polyp size was available for 62 patients in our study, including four patients with HGD (three proximal and one distal). Our results show that the risk of HGD was 4 % in any polyp ≤ 20 mm and 33 % for gastric adenomas > 20 mm (no distal lesions > 20 mm were recorded). HGD was not associated with adenoma location ( P = 0.17) or sex, despite a higher occurrence of HGD in females (6 %) than in males (4 %; P = 0.30). We acknowledge that these findings may be due to the relatively small numbers of HGD cases.

Our data show that gastric adenomas in patients with FAP may be more common in the distal stomach and may be more likely to be multiple. However, proximal gastric lesions may be more subtle and difficult to detect, especially in the presence of significant fundic gland polyposis, which are not located distally to the incisura. In our cohort, fundic gland polyposis was present at initial diagnosis of gastric adenoma in 83 % of patients. This is not different from FAP patients in general 19 but may be the reason for the observed variation in distribution of gastric adenomas rather than a true predilection of gastric adenomas to occur in the distal stomach.

We recognize that our results may be limited by retrospective data collection. Furthermore, over the 30-year study period, advances in the quality of imaging and endoscopic technology, better understanding of the appearances of gastric pathology, and referral bias mean that we cannot accurately describe true incidence rates of gastric adenoma in this patient group.

Although the etiology of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP remains unclear, associations with desmoid disease 6 , duodenogastric bile reflux 20 , atrophic gastritis 18 21 , and H. pylori 21 have been described in the literature. Studies have shown that the risk of gastric adenoma is higher in Korea and Japan (15 % – 50 %) 12 17 21 22 compared with Western populations (2 % – 10 %) 15 19 22 and there is no clear genotype – phenotype correlation so it is unclear why certain patients with FAP develop gastric adenomas. While we recognize the limitations of the study, it remains the largest cohort of FAP gastric adenomas to date and we suggest a new framework for the management of FAP gastric adenomas > 5 mm ( Fig. 2 ). The guidance is based on expert opinion with a view to conducting future studies to determine whether our proposed guidance reduces the incidence of gastric cancer in patients with FAP.

Conclusion

This is the largest series to date of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP. Overall, 14 % of patients with FAP had gastric adenomas, of which 5 % contained HGD. Endoscopic resection of gastric adenomas is safe with a low rate of recurrence; however, it does not completely eliminate the gastric cancer risk.

Footnotes

Competing interests Prof. Dekker has received a research grant and equipment loans from FujiFilm. She has also received honoraria for consultancy work for FujiFilm, Olympus, Tillots, GI Supply, and CPP-FAP, and speaker fees from Olympus, Roche, and GI supply. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material :

References

- 1.Kinzler K, Nilbert M, Su L et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgaard M, Fenger K, Bulow S et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): frequency, penetrance and mutation rate. Hum Mutat. 1994;3:121–125. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitis M, Jagelman D. Mortality in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:639–642. doi: 10.1007/BF02150736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nugent K P, Spigelman A D, Phillips R KS. Life expectancy after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1059–1062. doi: 10.1007/BF02047300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghorbanoghli Z, Bastiaansen B AJ, Langers A MJ et al. Extracolonic cancer risk in Dutch patients with APC (adenomatous polyposis coli)-associated polyposis. J Med Genet. 2018;55:11–14. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walton S-J, Frayling I M, Clark S K et al. Gastric tumours in FAP. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-9966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leone P, Mankaney G, Sarvapelli S et al. Endoscopic and histologic features associated with gastric cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mankaney G, Leone P, Cruise M et al. Gastric cancer in FAP: a concerning rise in incidence. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-9971-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagelman D G, DeCosse J J, Bussey H J. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1988;1:1149–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwama T, Mishima Y, Utsunomiya J. The impact of familial adenomatous polyposis on the tumorigenesis and mortality at the several organs. Its rational treatment. Ann Surg. 1993;217:101–108. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199302000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata C, Ogawa H, Miura K et al. Clinical characteristics of gastric cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:143–146. doi: 10.1620/tjem.229.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S Y, Ryu J K, Park J H et al. Prevalence of gastric and duodenal polyps and risk factors for duodenal neoplasm in Korean patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut Liver. 2011;5:46–51. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood L D, Salaria S N, Cruise M W et al. Upper GI tract lesions in familial adnomatous polyposis (FAP) Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:389–392. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Church J M, McGannon E, Hull-Boiner S et al. Gastroduodenal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1170–1173. doi: 10.1007/BF02251971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarre R G, Frost A G, Jagelman D G et al. Gastric and duodenal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective study of the nature and prevalence of upper gastrointestinal polyps. Gut. 1987;28:306–314. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagelman D G, Decosse J J, Bussey H JR. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1988;331:1149–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lida M, Yao T, Itoh H et al. Natural history of gastric adenomas in patients with familial adenomatosis coli (Gardner’s syndrome) Cancer. 1988;61:605–611. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880201)61:3<605::aid-cncr2820610331>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngamruengphong S, Boardman L, Heigh H et al. Gastric adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis are common, but subtle, and have a benign course. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2014;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bianchi L K, Burke C A, Bennett A E et al. Fundic gland polyp dysplasia is common in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spigelman A, Granowska M, Phillips R. Duodeno-gastric reflux and gastric adenomas: a scintigraphic study in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:476–478. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Kobori Y et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection and mucosal atrophy on gastric lesions in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2002;51:485–489. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi T, Ishida H, Ueno H et al. Upper gastrointestinal tumours in Japanese familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:310–315. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.