Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) refractive index (RI) tomography has recently become an exciting new tool for biological studies. However, its limitation to (1) thin samples resulting from a need of transmissive illumination and (2) small fields of view (typically ~50 μm × 50 μm) has hindered its utility in broader biomedical applications. In this work, we demonstrate 3D RI tomography with a large field of view in opaque, arbitrarily thick scattering samples (unsuitable for imaging with conventional transmissive tomographic techniques) with a penetration depth of ca. one mean free scattering path length (~100 μm in tissue) using a simple, low-cost microscope system with epi-illumination. This approach leverages a solution to the inverse scattering problem via the general non-paraxial 3D optical transfer function of our quantitative oblique back-illumination microscopy (qOBM) optical system. A theoretical analysis is presented along with simulations and experimental validations using polystyrene beads, and rat and human thick brain tissues. This work has significant implications for the investigation of optically thick, semi-infinite samples in a non-invasive and label-free manner. This unique 3D qOBM approach can extend the utility of 3D RI tomography for translational and clinical medicine.

1. INTRODUCTION

Quantitative phase imaging (QPI), the fundamental tool behind three-dimensional (3D) refractive index (RI) tomography, is a powerful tool in biomedicine due to its ability to produce high-contrast, non-invasive, label-free two-dimensional (2D) images of biological samples with subcellular detail based on endogenous, spatially dependent variations in RI [1]. Once quantified, RI gives rise to valuable biophysical information related to cell dry mass [2], sample thickness [3], and real-time cell activity [4,5]. Until recently [6], however, the need for a transmissive illumination in QPI has limited investigations to relatively thin, transparent samples, thereby limiting the biological utility of this technology to mostly ex vivo histology slides or cell preparations [3,7,8].

The shortcomings of QPI have naturally extended to 3D RI tomography [including optical diffraction tomography (ODT), or more generally, tomographic phase microscopy (TPM)]. ODT relies on acquiring multiple interferograms using QPI with diverse illumination and reconstructing a volume, typically in a similar fashion to x ray computed tomography [9,10]. Thus, while 3D RI tomography has recently become an interesting and powerful tool for biological studies—given its unique high-resolution, label-free 3D insight [9,11–13]—its limitation to samples of thickness no more than a few cells has also significantly hindered its overall utility. Again, this limitation to thin samples is mostly rooted in a need for transmissive illumination, which has made bulk or in vivo tissue imaging fundamentally out of reach for these technologies. Other limitations of ODT also include small fields of view and the need for coherent laser sources and specialized equipment [9,14].

Indeed, label-free 3D tomographic imaging with epi-illumination is widely available using optical coherence tomography (OCT) [15] or confocal reflectance microscopy (CRM) [16]. However, these methods derive contrast from backscattered light, which primarily arises from large variations in RI. Thus, while both OCT and CRM enable 3D imaging in arbitrarily thick samples, they lack critical structural detail encoded in the forward-scattered field [17]. On the other hand, QPI and ODT collect the forward-scattered information and recover structural detail that much more faithfully depicts subtle internal cell structure, at the cost of being restricted to thin, transmissive samples.

To resolve this trade-off, we recently introduced quantitative oblique back-illumination microscopy (qOBM), which recovers quantitative phase information in thick scattering samples using epi-illumination [6]. The approach is based on principles of oblique back-illumination microscopy (OBM) [18], which uses a conventional bright-field microscope with epi-illumination to produce a transmissive virtual light source within a thick sample by way of multiply scattered light [see Figs. 1(a) and 1(b)]. This illumination scheme permits the imaging of samples that are optically thick, including effectively opaque semi-infinite scattering media such as tissue samples in vivo or excised in bulk, which would pass little to no light in a typical transmissive illumination configuration. In qOBM, this general framework was advanced to produce 2D quantitative phase images of thick tissues with subcellular resolution by leveraging the method’s inherent cross-sectional capabilities [6]. However, in analogy to the transition from QPI to ODT, the finite extent of the 3D point spread function (PSF) of the system must be explicitly addressed to properly transition from a system that produces 2D phase images to one that maps RI in 3D.

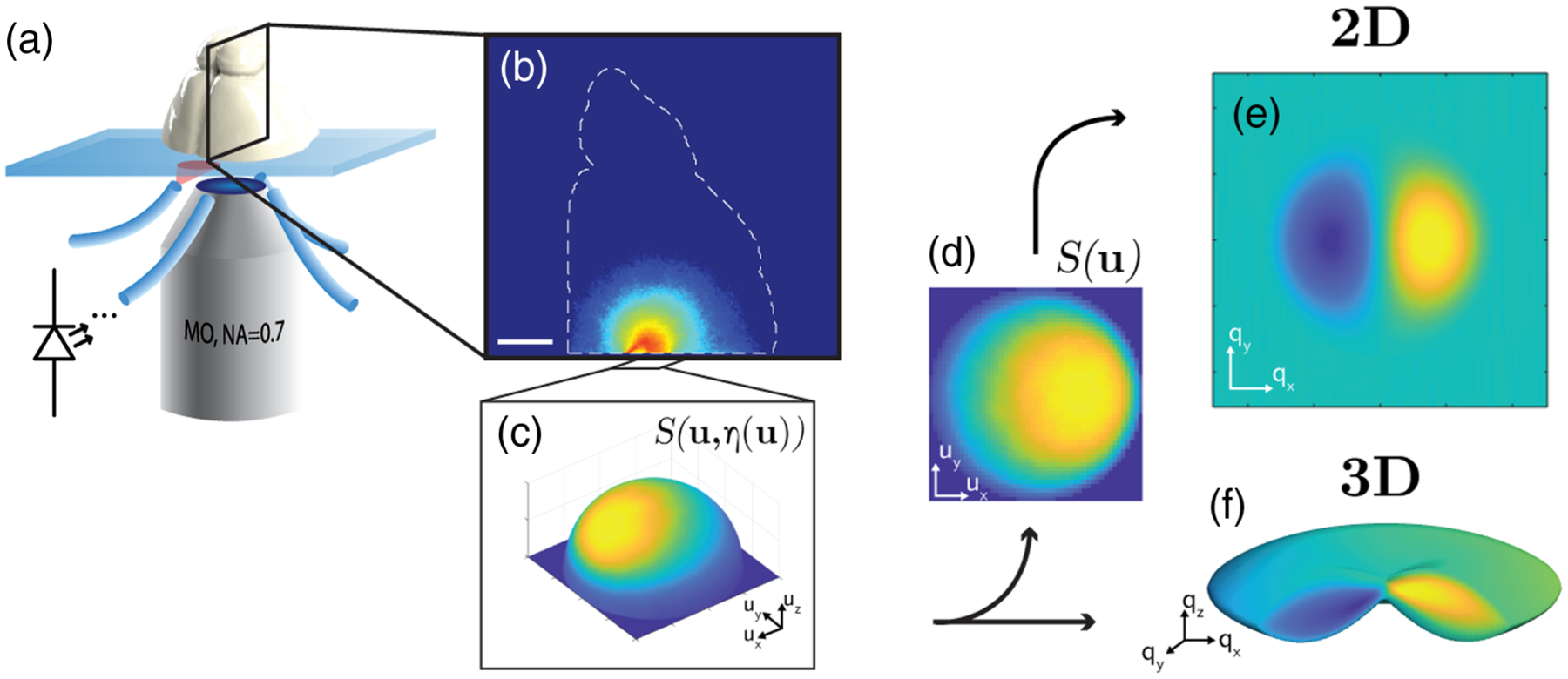

Fig. 1.

System diagram and processing overview. (a) LED-illuminated inverted microscope configuration with coronally sectioned rat brain on a slide. (b) Log visitation likelihood projection through transverse shear axis, demonstrating a high-fidelity Monte Carlo simulation geometry. Scale bar is 2.5 mm. (c) Photon angular distribution collected at the sample plane. This distribution is shown on the unit sphere surface to indicate that the non-paraxial angular coordinates represent a 3D unit vector in the direction [ux, uy, η], where . (d) Source distribution projected onto a planar coordinate grid u = [ux, uy], scaled with obliquity factor η. (e) Example 2D phase transfer function in pupil plane coordinates q = [qx, qy] corresponding to wavelength-scaled spatial frequency grid. (f) Example 3D phase transfer function distribution in the 3D pupil plane coordinates [qx, qy, qz].

In this work, we expand the capabilities of qOBM to recover wide field-of-view 3D RI tomographic maps of arbitrarily thick scattering (i.e., opaque) samples using epi-illumination. These capabilities are achieved by first adopting a solution to the inhomogeneous Helmholtz equation, which leads to the general non-paraxial 3D optical transfer function (OTF) of our optical system. Then, together with a through-focus stack of intensity images from two pairs of diametrically opposed light sources, we are able to recover 3D RI maps with subcellular resolution, via direct deconvolution. Compared to previous ODT methods [9–13], qOBM provides clear benefits, including (1) use of a conventional bright-field microscope without additional complex/expensive components, (2) wide fields of view, and (3) most importantly, the ability to recover the same quantitative biophysical information in previously inaccessible environments, namely optically thick scattering samples that cannot be imaged with transmission-based systems. A theoretical analysis is presented, along with simulations and experimental validations using polystyrene beads, and thick rat and human brain specimens. The results of this work show that qOBM can greatly expand the utility of 3D RI tomography to many areas of biomedicine, including translational and clinical medicine.

2. qOBM OVERVIEW AND MICROSCOPE SYSTEM

qOBM integrates principles of OBM [18] with a novel photon transport approach to model the optical system and enable reliable quantitative image reconstructions [6]. In OBM, two images are obtained with illumination from diametrically opposed LED light sources. Then, the two images are subtracted from one another to produce a differential phase contrast (DPC) image, similar to that of differential interference contrast (DIC) but in thick samples with epi-illumination [18,19]. In order to produce quantitative images of phase with qOBM, the original OBM setup was modified and additionally equipped with a novel intensity-based phase recovery algorithm [6]. First, qOBM introduces a second pair of LED light sources, orthogonal to the first pair to recover phase information in that direction. Second, the phase recovery algorithm initially applied for qOBM was based on numerically modeling the angular distribution of light at the focal plane of the system within the thick sample, thus leading to the (transmission-like) effective source distribution in that plane. This distribution is insensitive to microscopic variations within the sample and largely invariant for biological tissues given the relatively long scattering path length and near unity anisotropy of most biological materials [20]. Ultimately, the source distribution enables us to produce a 2D OTF of the system (see Fig. 1), which is applied to recover en face quantitative phase images of a thin slice within a thick object (i.e., produce a virtual cross section).

In the section below, we provide a formal mathematical picture of this 2D reconstruction strategy and compare it to the proposed 3D model, which provides a more complete depiction of the system. The 3D model incorporates a robust solution to the inverse scattering problem for our qOBM system. Results of the 3D reconstruction not only show improved image quality, but also enable 3D RI tomography.

The qOBM system [Fig. 1(a)] has been previously described in Refs. [6,21,22]. In brief, the overall system comprises a standard inverted bright-field microscope configuration with epi-illumination from four LEDs (far-red Luxeon Rebel ES, 720 nm), each coupled into a multimode fiber (1 mm diameter) affixed around a long working distance microscope objective (Nikon S PLAN, 60×, NA 0.7) using a custom-made 3D printed adapter. The light delivery fibers are held at a canted angle (45°), 7 mm away from the center of the objective (see Fig. 1). When compared to coherent sources, incoherent LEDs reduce the cost of the system and preclude the possibility of photodamage due to their relatively low power on the sample (30 mW of diverging incoherent light). Images are captured with a sCMOS camera (pco.eddge 42LT) at 20 Hz. The objective is mounted on a motorized z-stage (Thorlabs, ZFM2020), and the sample is mounted on a motorized xy-stage (Optics Focus Instruments Co,. Ltd.). The stages, LEDs, and camera are coordinated with in-house software (National Instruments LabView 2019).

3. THEORY AND RECONSTRUCTION METHODS

In general, to translate phase (a quantity of the light field) to RI (a quantity of the object), volumetric spatial information is needed. Thus, in principle, the original framework for qOBM, which applies a 2D deconvolution to recover phase from a thin slice within a thick object, can produce volumetric images of RI by stacking individual images of phase at different planes and accounting for the effective thickness of each slice. However, as we show below, rendering 3D RI maps in this fashion has the unintended consequence of incorrectly mapping certain frequency components and amplifying components outside the axial frequency-support of the first-order system, which primarily contributes to noise. Together, these errors lower the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and suppress low-frequency information. Therefore, an analysis of the microscope as a 3D system is needed for a more complete reconstruction of the RI distribution of thick objects.

A. 2D Quantitative Phase Images with qOBM

We start our discussion with the framework of our 2D approach and then build up to the 3D model. The 2D analysis may proceed from the propagation of the angular spectrum of incident light across a thin object or thin slice within a thick object with complex transmittance [23],

| (1) |

| (2) |

where μ(x) and ϕ(x) are the object’s absorption and phase properties, respectively, along a thin slice, and x is a 2D transverse coordinate vector in the object space. Here an approximation is made for a weak scattering object (see Supplement 1, Section 4) with negligible absorption. Note that in the biological samples under investigation, absorption certainly occurs on the scale of the bulk tissue as a whole. However, the approximation takes absorption to be negligible only on the scale of the effective cross-sectioning thickness afforded by the partial coherence of the illumination, which is just a few micrometers.

The phase term here can be related to the RI of the object by taking the 2D screen of infinitesimally small thickness δz to instead represent an average transmittance over a finite thickness Δz, which yields the familiar form

| (3) |

where n0 is the background index of refraction, λ is the wavelength, and n(x) is the locally varying index of refraction of the object. Without loss of generality and for the rest of this work, we scale the object’s varying index of refraction according to n′(x) = n(x)/n0, and let the quasi-monochromatic wavenumber be given by , allowing us to represent Eq. (3) according to ϕ = kΔzΔn, where Δn(x) = (n′(x) − 1).

The light incident on a detector can be evaluated by decomposing an incident incoherent light field into constituent illumination angles, along the wavelength-normalized 2D direction cosine vector u, then propagating the field, E(u), from the object, o(x), to the pupil, P(f), and once again into the plane of the camera. Finally, all angles illuminating the sample are summed incoherently. This procedure may be summarized as

| (4) |

where u, x, f, are wavelength-normalized coordinates in the source, object, pupil, and camera planes, respectively, and represents a 2D Fourier transform operation. This function can be evaluated into a convolution of the object and its own complex conjugate with a four-dimensional transfer function scaling factor [24]. After substituting the pupil plane coordinates of integration m and n for f, and introducing a Fourier space coordinate vector q = m − n at the detector plane, the Fourier transform of Eq. (4) can be expressed as (see Ref. [6] for details)

| (5) |

where O(m) is the object transmission function in Fourier space and C(m, m − q) is the four dimensional partially coherent transfer function of the form

| (6) |

where S(u) = |E(u)|2 is the light angular intensity distribution illuminating the object. Next, for a weak phase object, O(m) ≈ δ(m) + iΦ(m), where Φ(m) is the Fourier pair of the object’s phase term, Eq. (5) can be simplified to

| (7) |

Equation (7) again assumes a weak phase object, and for simplicity, negligible absorption (the subtraction process in OBM and qOBM eliminates this term regardless [6]). Because ϕ(x) is real, its Fourier counterpart exhibits Hermitian symmetry, Φ(q) = Φ*(−q). Without the DC term in the right-hand side (RHS) of Eq. (7),

| (8) |

Finally, we may recast the subtraction term in brackets on the RHS of Eq. (8) as a linear 2D weak phase object transfer function by evaluating Eq. (6) in Eq. (8), and making a change of variables in C(q, 0) and in C(0, −q), so that

| (9) |

where S(u) is the effective, and arbitrary, source intensity distribution in incident angle.

Therefore, the linear image formation for this weak phase object is modeled as , where t(x) is the net PSF of the system and Fourier pair of the phase transfer function given by Eq. (9), and ** represents a 2D convolution operation. This transfer function can be seen to depend on two system-dependent factors: (1) the exit pupil function of the system P(u), which for qOBM is taken as a discrete mask for angles that fall within the acceptance angle of the objective (i.e., the objective’s NA); and (2) the effective source angular distribution S(u). Note that the quantity in brackets in Eq. (9) selects the odd portion of the illumination, indicating that for an effective odd illumination (such as that synthesized by a difference image between two symmetrically opposed illuminations in qOBM), the phase information is selected. Absorption information, even if present and non-negligible to a first order, is also rejected when the net illumination is odd [6].

This approach can produce volumetric phase images (and hence RI volumes assuming some known Δz) given the cross-sectioning capabilities provided by the highly incoherent nature of the effective illumination in qOBM [25]. However, the cross section is not an ideal 2D thin screen, and thus a more complete model is needed to account for the finite axial extent of the 3D PSF of the system. This ultimately leads to a drastically more faithful, high-resolution volumetric recovery of the RI properties of complex, thick, 3D biological structures.

B. 3D Refractive Index with qOBM

Now consider a 3D image intensity distribution consisting of a stack of 2D images with different parts of a 3D object in focus (i.e., through-focus stack of intensity images). We assume again that the object is non-absorbing and has a spatially varying RI distribution of , where is the 3D spatial vector (the vector arrow is used here in addition to the bold typeface to more clearly distinguish a 3D vector from a 2D vector). We begin this analysis with the the inhomogeneous Helmholtz equation,

| (10) |

where is the scattering potential given by

| (11) |

where has been scaled according to the discussion following Eq. (3). The 3D linear transfer function of a microscope, which relates the 3D image intensity distribution to the scattering potential, was first treated in this way in the seminal work by N. Streibl [26], where it was developed in the paraxial regime according to the propagation of mutual intensity. Alternatively, it may be reproduced by an analysis of the angular spectrum of the field incident on the target, and then integrating the incoherent contributions from the source in a manner analogous to the 2D treatment summarized above. This analysis may proceed from the angular spectrum representation of the first-Born scattering potential [27], or as an extension of the 2D theory [28] by noting that for a weak phase object (),

| (12) |

While the scattering potential and RI may in general be complex, as before, here we only treat the real part without loss of generality. Any contributions from the imaginary part (i.e., absorption) are eliminated in the subtraction process in qOBM.

To produce a 3D OTF for an arbitrary source distribution, which links the measured intensity image stack, , to the scattering potential, , we evaluate the general non-paraxial OTF [29],

| (13) |

where q =[qx, qy], and qz is shown as separate variables to maintain clarity in the formalism between 2D and 3D formulations. Note that this treatment applies to both low and high NA imaging conditions. Further, this 3D OTF is of a similar form to the 2D OTF in Eq. (9) with the added delta function, which is effectively a consequence of conservation of energy, and forms two spherical (Ewald) shells [30]. The first Ewald shell has radius λ−1 centered around −λ−1u0, where u0 is the wavelength-normalized direction vector of illumination for a particular component of the source S(u). The second shell has a Hermitian symmetry with the first and probes the corresponding complex conjugate portion of the scattering potential.

To more clearly connect the 2D and 3D theory, we can adopt a modified pupil function [30–32] given by

| (14) |

where uz represents the z-frequency component in the pupil space. A thorough discussion on the transition from 2D to 3D diffraction theory can be found in Ref. [28], but for the purposes of this work, we note that, according to Eqs. (3) and (12), for a thin diffracting screenwhere Δz ≈ δz,

| (15) |

By scaling the coefficient on the RHS of Eq. (13) according to the results of Eq. (15), we obtain an effective transfer function for the phase,

| (16) |

Equation (16) can be seen to evaluate to Eq. (13) by using the relations δ*(x − β) = δ(β − x) and ∫ δ(α − x)δ(x − β)dx = δ(α − β) in the product of the two forms of Eq. (14) in Eq. (16), and by integrating Eq.(16) along the uz dimension.

The resulting 3D transfer function of ϕ(x) [Eq. (16)] has exactly the same form as Eq. (9), but with the modified pupil function from Eq. (14), and a 3D integration (instead of 2D) in frequency space. While this makes it clear that the 2D and 3D theories are fundamentally linked, the absence of the explicit z axis dependence in the delta functions of Eq. (9) (2D form) compared to Eq. (16) (3D form), demonstrates the well-known inability of the 2D theory to accurately represent diffracted phase contributions from outside the focal plane. Given the curvature of the modified pupil function in Eq. (16), both a 3D data volume and 3D reconstruction are necessary to more faithfully recover the properties of the scattering object. Otherwise, in the 2D model, improperly assigned and/or unaccounted frequency components can pollute the reconstructed en face 2D image.

Finally, the 3D image intensity stack can be expressed in terms of the scattering potential convolved with the 3D PSF according to , where the operator *** represents a 3D convolution and is the 3D scattering potential PSF.

C. Numerical Evaluation of the 3D OTF

The numerical evaluation of this transfer function was accomplished by looping through discrete points in the pupil plane, shifting the source distribution, and windowing in z axis spatial frequency by treating the delta function in Eq. (13) as a scaled Kronecker delta. The angular distribution of the source, S(u), is derived from Monte Carlo simulation using bulk tissue scattering properties from the literature [6,33,34] (see Supplement 1, Section 2 for more details). An example 3D transfer function produced in this way is given in Fig. 1. Quantitative reconstruction is therefore achieved by an appropriate deconvolution technique [35,36]. Iterative approaches to linear deconvolution can also be applied (as explicitly shown here) but trade computational cost for reconstruction fidelity [10]. We note that for the wide volumetric fields of view achieved here (e.g., 243 μm × 243 μm × 104 μm), direct inversion via Tikhonov regularization provides the most efficient reconstruction,

| (17) |

Here represents the Fourier transform of the 3D intensity stack of the kth illumination, and α is the regularization term, here determined heuristically. Lastly, we use Eq. (11) to recover the 3D RI distribution from the scattering potential.

In this work, k = 2 for the two odd effective sources at orthogonal shear directions, each produced from the subtraction of two diametrically opposed sources, in a differential phase configuration. The four (or more) illumination sources can be deconvolved independently, in which case k ≥ 4, but we find that subtracting opposed images first yield better results. This may be due to a better rejection of non-phase information in the subtraction process, compared to that achieved in the least squares process for the independent Tikhonov reconstructions.

Additionally, to show the benefits and trade-offs of an iterative reconstruction method, we apply a total-variation (TV) nonnegativity constrained iterative deconvolution in small select reconstruction volumes [37]. This iterative approach seeks to find a compromise between data fidelity and a total sum of directional gradients and is commonly used in coherent tomographic phase methods [9]. A discussion of the appropriateness of this approach in dense wide-field volumes of unperturbed tissue is taken up in Section 3 of Supplement 1. This approach provides a higher fidelity reconstruction compared to the direct inversion at the cost of computational time (>500 times slower than a Tikhonov reconstructions; see Supplement 1, Section 3).

4. RESULTS

To validate our 3D RI tomography approach, we first use polystyrene microspheres (n = 1.581 at 720 nm) suspended in a thermoplastic medium (Cargille, Meltmount, n = 1.533 at 720 nm), and placed in a 100 μm well on a glass slide. The surrounding medium was selected such that the bead produced adequate contrast without higher-order scattering artifacts, such as lensing, providing an environment similar to that of a biological sample.

A 1% intralipid-agar phantom was placed over the bead preparation [38], and a through-stack of qOBM images was taken with Δz = 0.5 μm. The 3D RI distribution was produced by first stacking 2D images produced from the 2D model, and then by deconvolving the volume with the 3D OTF (Eq. 17). As described above, two types of 3D reconstructions were implemented: Tikhonov and iterative deconvolution. As an additional step in this validation, the 3D microscope image stack of the bead was simulated using a partially coherent first-Born simulation of the microscope developed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc). RI volumes were also computed with the 2D and 3D models for comparison with the experimental results. A discussion of the validity of the first-Born approximation for the beads with the chosen RI contrast is given in Section 4 of Supplement 1.

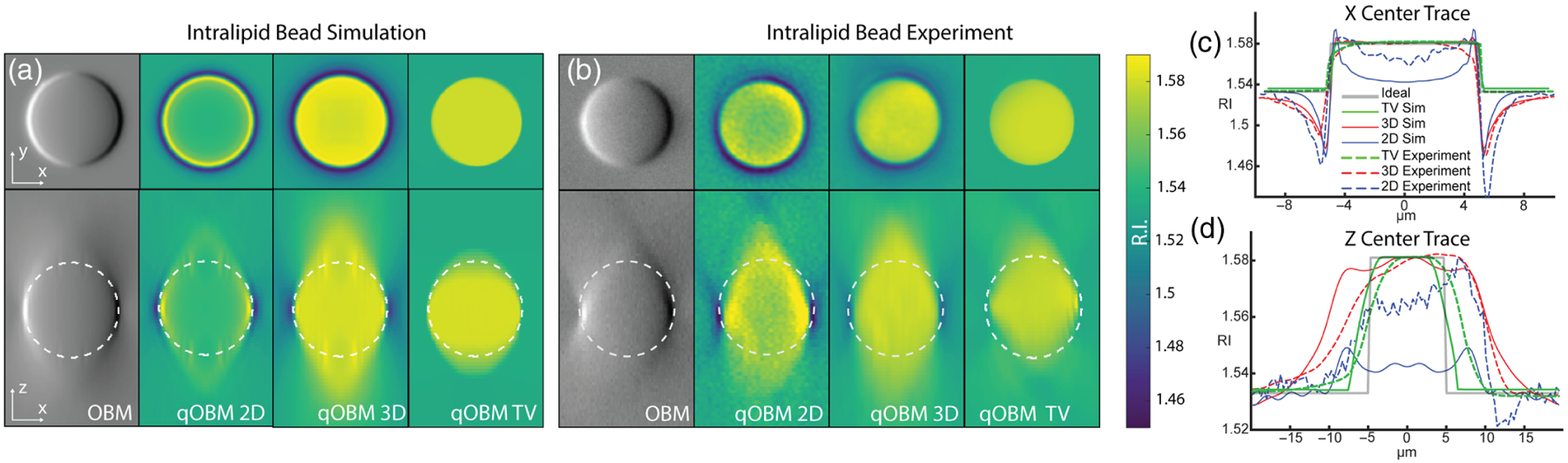

Simulation and corresponding experimental results of polystyrene microsphere are shown in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b), respectively, which show excellent agreement. Data are presented in four formats: The first column shows the OBM images produced from subtracting raw captures from one diametrically opposed light source pair. The second column shows the RI reconstructed from 2D phase images axially stacked, with Δz = 0.35 μm. The third column shows the RI distribution obtained for the direct Tikhonov 3D deonvolution of the entire stack. Finally, the fourth column shows the RI distribution for the iterative TV reconstruction. It can be seen by comparing the 2D and 3D reconstruction methods that deconvolving with a 3D OTF results in a fuller, more consistent bead reconstruction with the shape of a solid structure with a level cross-sectional profile. On the other hand, the 2D reconstruction shows a hollow structure. This is a consequence of the 2D model not correctly accounting for the curvature of the pupil function (i.e., Ewald sphere) as described in Eq. (13), resulting in a loss of low-frequency content. Both the 2D and 3D Tikhonov deconvolution reconstructions retain some degree of axial spread due to the difficulty of restoring frequencies with a direct deconvolution in the high-axial frequency “missing cone” region. This issue is largely mitigated with the iterative TV reconstruction, which shows a near perfect 3D reconstruction. However, this comes at the significant cost of computational resources, which for this small volume translates to a factor of 372 times slower compared to the direct 3D deconvolution (see Supplement 1, Sections 1 and 3 for more details). As computational power improves and as more advanced algorithms are implemented and developed, we expect this trade-off to be less severe.

Fig. 2.

(a) Bead simulation and (b) experimental results of z-stacks of 10 μm polystyrene bead underneath a 1% intralipid-agar scattering phantom. Cross sections through the imaging plane (X − Y) are shown on top and through the axial plane (X − Z) are shown on bottom. From left to right, the images show a volume rendition of bead using OBM, 2D effective RI reconstruction, direct Tikhonov 3D RI reconstruction, and iterative TV-constrained 3D RI reconstruction. (c) Center trace through x axis demonstrating halo-artifact reduction by the 3D reconstruction. (d) Center trace through z axis.

Next, the entire validation experiment was repeated using a fresh, thick brain instead of intralipid-agar phantom as the scattering media for the bead preparation. Results, described in Supplement 1, Section 1 and Fig. S1, are nearly identical to the intralipid-agar phantom experiment (Fig. 2). These data further support the quantitative capabilities of 3D qOBM in a thick inhomogeneous scattering medium like those natively present in vivo and in bulk biological tissue samples.

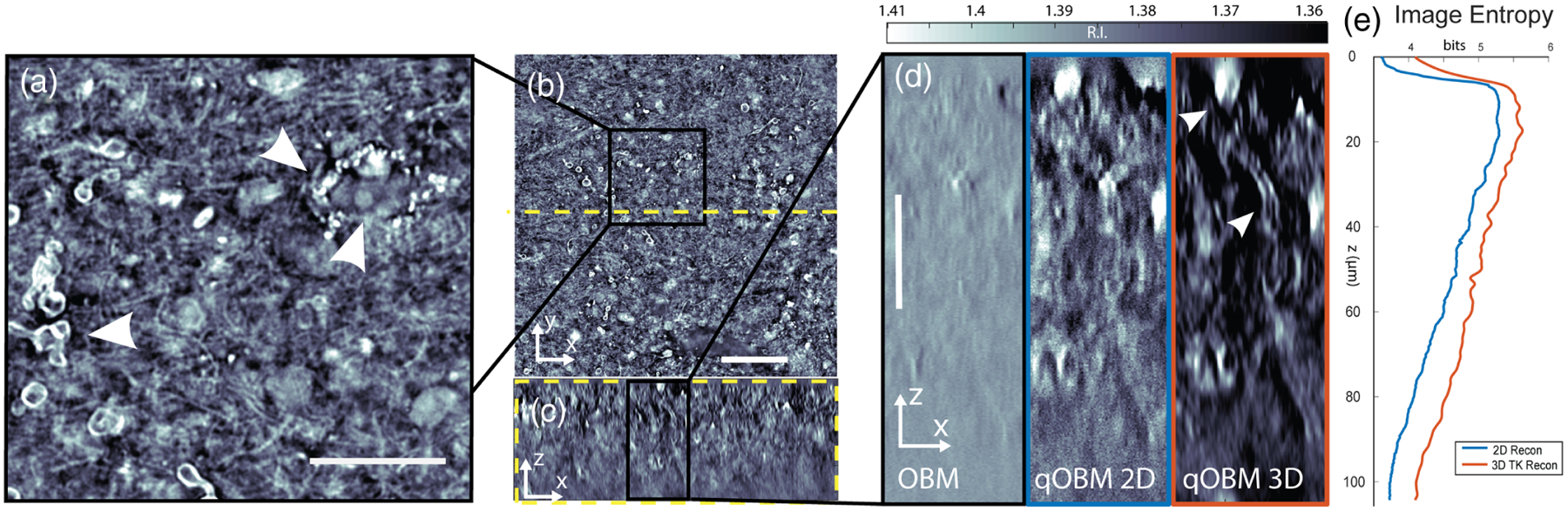

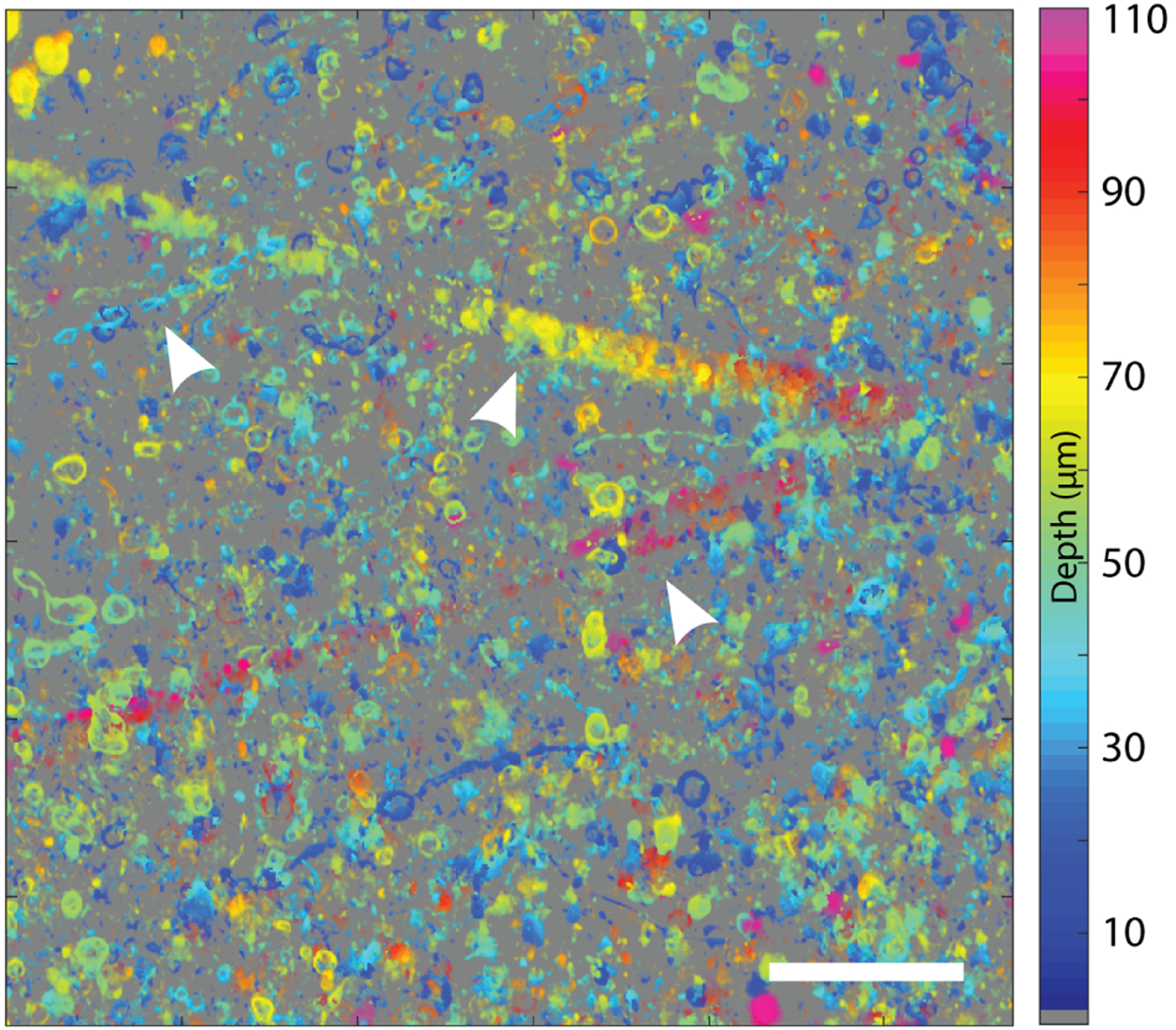

We proceed to demonstrate the 3D qOBM system in complex, unaltered, semi-infinite opaque biological samples, in which qOBM is uniquely suited to resolve diffraction-limited 3D RI structural information. Figure 3(a) shows a full-field image of a portion of unaltered fresh human cortex tissue discarded from surgery at 48 μm of depth. A cross section of this depth may be produced with this fidelity due to the high degree of incoherence of the net (multiply scattered) illumination source. Further, speckle noise is completely eliminated. A select magnified region [Fig. 3(b)] clearly shows an axonal cross section, extracellular vesicles, and neuronal cell nucleus, highlighting the ability of qOBM to provide detailed subcellular insight. Figure 3(c) shows an X − Z cross section of the same 243 × 243 × 104 μm volume of cortex, with a magnified version in Fig. 3(d), which captures a red blood cell (top) and an axially traversing axon cross section. The benefits provided by the 3D qOBM reconstruction compared to the 2D stacks and OBM are clear, with the former showing better object conspicuity and image quality (i.e., SNR), and consequently deeper penetration depth. Figure 4 is a maximum intensity projection of this volume, with color encoding depth. While contrast diminishes with depth, structural features up to 100 μm deep remain distinguishable (ca. one mean free scattering path length). This behavior can also be seen in Fig. 3(e) with the steady decline of Shannon entropy, an indicator of image information content [39] and surrogate for SNR, decreasing steadily with depth due to scattering noise. Note that the 3D reconstruction has higher entropy than the 2D reconstruction at all depths, in agreement with visual inspection of Fig. 3. Additional examples are provided in Figs. S3 and S4 of Supplement 1.

Fig. 3.

Human brain biopsy (cortex). A 243 μm × 243 μm × 104 μm volume is shown embedded in a 1 cm bulk sample. (a) Enlarged selected region from (b) a representative en face slice at 48 μm depth. Scale bar is 50 μm. (b) From left to right, arrows indicate axonal cross section, extracellular vesicles, and neuronal cell nucleus, respectively. Scale bar is 20 μm. (c) Side central cross section at the yellow dashed line in (b), at the same scale as (b). (d) Enlarged selected region from (c). From left to right, the images represent the same region from a conventional OBM reconstruction, 2D qOBM, and 3D qOBM reconstructions, respectively. Arrows indicate a pooled red blood cell (top) and an axially traversing axon cross section. Scale bar is 25 μm. (e) Shannon entropy of image as function of depth.

Fig. 4.

Depth coded maximum intensity projection in XY, depth encoded by color. The most prominent visible features are myelinated axons, due to their high-RI lipid rich content. From left to right, the arrows indicate an axon, a descending blood vessel, and an ascending blood vessel. Scale bar is 50 μm.

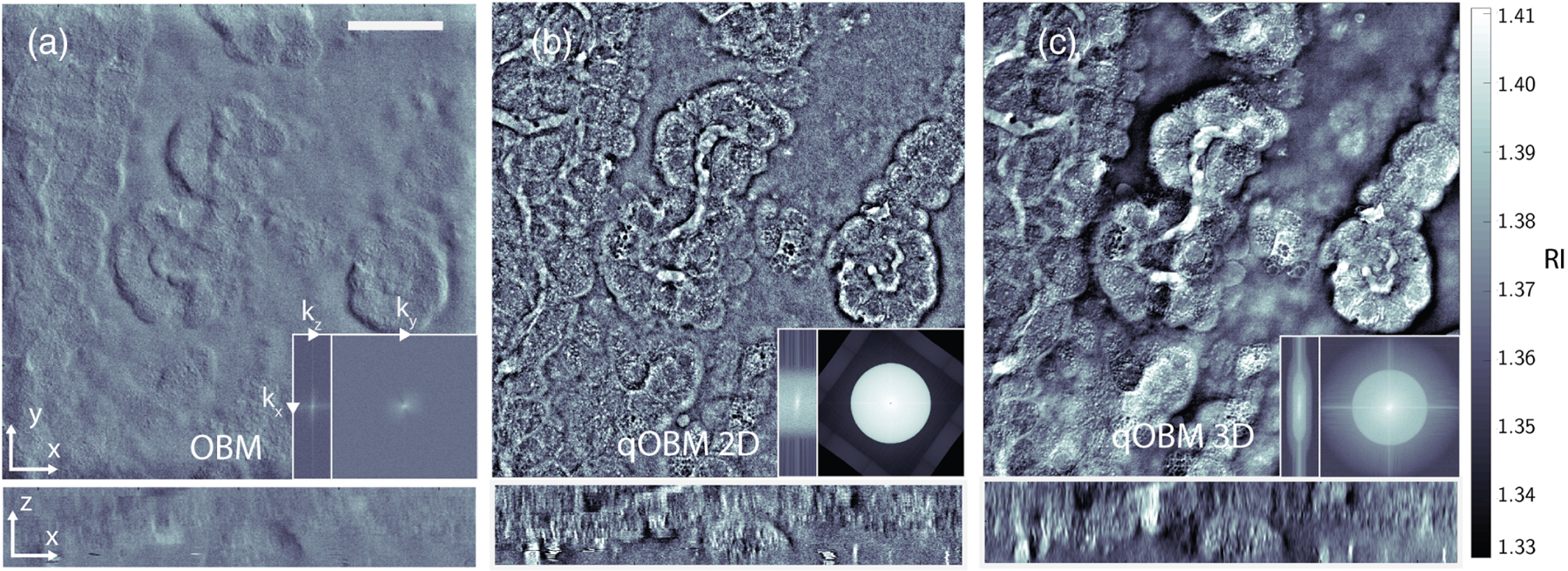

Finally, Fig. 5 shows images collected from choroid plexus of a thick unaltered (fresh) coronal section of a rat brain [see Figs. 1(a) and 1(b)]. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Georgia Tech and Emory University. This tissue consists of mesoscale folds of epithelial cells that mediate the production of cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain [40]. The reconstructions of bulk tissue with the 3D transfer functions in Fig. 5(c) can be seen to preserve low-frequency variations in mesoscale structures and reduce noise, when compared to the flatter, noisier images from the 2D reconstruction and OBM. This effect is directly analogous to the hollow structure observed in the 2D reconstruction of the beads in Fig. 2. For the choroid plexus, as with the beads, the 3D treatment of RI is necessary to preserve axial structures that vary slowly over the course of several frames in a through-stack.

Fig. 5.

Rat brain choroid plexus. A 243 μm × 243 μm × 44 μm image volume is shown from a large intact rostral half of the brain. (a) En face (x − y) phase contrast image produced by original OBM, cross section at 15 μm depth. Bottom shows x − z cross section. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Left inset, axial (kx, kz) Fourier space of reconstructed volume. Right inset, transverse (kx, ky) Fourier space of reconstructed volume. Spatial frequency axes shown span ± 3.7 μm−1 laterally (kx, ky) and ± 1 μm−1 axially (kz). Note missing bow-tie region due to lack of transverse shear information. (b) Same regionas (a), 2D reconstruction from two orthogonal illuminations. Left and right insets, corresponding Fourier space cross sections in x − z and x − y spatial frequencies, respectively. Note cylindrical shape of reconstructed support structure, indicating a passage of high z-frequency noise. (c) Same region as (b), but with a 3D OTF reconstruction. Note the preservation of low- to mid-range frequencies indicating mesoscale structure of epithelial folds in choroid plexus. Left and right insets, corresponding Fourier space cross sections in x − z and x − y spatial frequencies, respectively. Note that the region of support is roughly limited to frequencies predicted by the 3D linear OTF.

Fourier space images shown in Fig. 5 (insets) demonstrate another important advantage of the 3D model. Specifically, the support structure in the 3D reconstruction is well confined to the domain of the OTF of the system. On the other hand, the stacked 2D reconstruction includes axial frequency components beyond the figure-eight support structure of the system. This results from the inherent assumption of the 2D model that it probes a thin Δz slice of the thick 3D object. While there may be recoverable structural information in some of these higher kz terms, without proper treatment, these components mostly contribute to noise in the 2D reconstruction [41]. It is also worth highlighting that the image reconstructed with OBM lacks a substantial number of lateral spatial frequencies. Of note, the transverse Fourier space image (kx, ky) shows a bow-tie structure, resulting from the use of a single diametrically opposed light source pair. The missing information in the orthogonal direction ensures that no properly filtered gradient integration or deconvolution can properly recover the phase information present in the object without a second, perpendicularly illuminated image. This limitation is shared across any modality that uses gradient phase information along one direction [42,43].

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

By producing 3D maps of RI, qOBM proceeds naturally from a QPI method to a method of TPM [9]. Importantly, as we have shown here, qOBM simplifies the instrumentation and overcomes many important limitations of TPM. For example, instead of using laser light sources, which are expensive and subject to coherent artifacts [44], qOBM uses low-cost, incoherent LEDs. The qOBM system also does not require beam scanning or other specialized equipment, as is often required in TPM [9]. Rather, tomographic imaging is achieved with simple modifications to a bright-field microscope and a through-focus image stack. Furthermore, qOBM yields a wide field of view, which is typically restricted in TPM. The inherent optical sectioning capabilities of qOBM allow a direct deconvolution to produce robust 3D RI results in seconds, even for very large data sets (see Supplement 1, Section 3 for more details). If necessary, more complex iterative methods can be implemented to achieve higher fidelity reconstructions, at the cost of computational time. Finally, the most critical advantage of qOBM is that it is designed to operate in semi-infinite opaque scattering samples, which has been a long standing limitation of TPM. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, this work presents the first quantitative RI volumetric images of arbitrarily thick biological samples (≫1 cm3) with subcellular resolution and with a current penetration depth of ca. one mean free scattering pathlength.

The advancement of the 3D model from the 2D model for qOBM is also substantial. We have shown that the RI map produced by concatenating sequentially captured 2D qOBM images may be numerically faithful to RI of the object, with minimal out-of-plane diffraction artifacts. However, the 2D RI reconstruction limits mesoscale structures due to an incorrect mapping of frequency components. Further, the tendency of the 2D reconstruction to treat out-of-plane diffraction artifacts as in-plane phase features inadvertently amplifies high-axial frequency noise. In light of a complete 3D linear systems interpretation of the microscope, a more accurate RI map is produced by deconvolving the intensity image stack with the non-paraxial 3D OTF of the system. With this approach, qOBM offers a unique ability to investigate biological structures in scales and domains previously unavailable to RI tomography techniques.

It is important to note that other recent advances have also sought to overcome some of the aforementioned limitations of TPM. For example, dynamic-speckle has been applied to overcome coherent artifacts [45], temporally or spatially incoherent illumination has been used for depth sectioning [13,46], and implementation of a reflection Nomarski system allows investigation of thick samples [43]. Each of these methods addresses an important problem with or limitation of conventional TPM, but manages to solve one or two of the several difficulties individually that 3D qOBM is able to overcome simultaneously.

The advantages provided by qOBM pave the way for broader usage of 3D RI tomography, particularly for in vivo, translational, and/or clinical applications, which have been largely out of reach for this technology. Here we have presented images of thick brain tissues, demonstrating the ability of qOBM to provide detailed 3D RI biophysical insight of this critical organ. Indeed, qOBM can provide clear visualization and quantification of axons, neuron soma, blood vessels, and other brain structures in a label-free manner and potentially in vivo, which is vitally important for improving our understanding of brain function and tracking changes that may occur in the progression of disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease). Similarly, there are many other biomedical applications that would benefit from label-free in vivo or in situ 3D RI tomography, ranging from regenerative medicine to clinical applications. Therefore, we expect qOBM to become an important tool in the hands of researchers and clinicians alike.

Supplementary Material

Funding.

Burroughs Wellcome Fund (1014540); Marcus Center for Therapeutic Cell Characterization and Manufacturing; National Cancer Institute (R21CA223853); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21NS117067); National Science Foundation (NSF CBET CAREER 1752011); Georgia Institute of Technology.

Footnotes

Disclosures. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this paper.

See Supplement 1 for supporting content.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park Y, Depeursinge C, and Popescu G, “Quantitative phase imaging in biomedicine,” Nat. Photonics 12, 578–589 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popescu G, Park YK, Lue N, Best-Popescu C, Deflores L, Dasari RR, Feld MS, and Badizadegan K, “Optical imaging of cell mass and growth dynamics,” Am. J. Physiol 295, C538–C544 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaked NT, Rinehart MT, and Wax A, “Dual-interference-channel quantitative-phase microscopy of live cell dynamics,” Opt. Lett 34, 767–769 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jourdain P, Boss D, Rappaz B, Moratal C, Hernandez MC, Depeursinge C, Magistretti PJ, and Marquet P, “Simultaneous optical recording in multiple cells by digital holographic microscopy of chloride current associated to activation of the ligand-gated chloride channel GABAA receptor,” PLoS ONE 7, e51041 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marquet P, Depeursinge C, and Magistretti PJ, “Review of quantitative phase-digital holographic microscopy: promising novel imaging technique to resolve neuronal network activity and identify cellular biomarkers of psychiatric disorders,” Neurophotonics 1, 020901 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledwig P and Robles FE, “Epi-mode tomographic quantitative phase imaging in thick scattering samples,” Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 3605–3621 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gureyev TE and Nugent KA, “Rapid quantitative phase imaging using the transport of intensity equation,” Opt. Commun 133, 339–346 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ou X, Horstmeyer R, Yang C, and Zheng G, “Quantitative phase imaging via Fourier ptychographic microscopy,” Opt. Lett 38, 4845–4848 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin D, Zhou R, Yaqoob Z, and So PTC, “Tomographic phase microscopy: principles and applications in bioimaging [Invited],” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 34, B64–B77 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim K, Yoon J, Shin S, Lee S, Yang S-A, and Park Y, “Optical diffraction tomography techniques for the study of cell pathophysiology,” J. Biomed. Photon. Eng 2, 020201 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi W, Fang-Yen C, Badizadegan K, Oh S, Lue N, Dasari RR, and Feld MS, “Tomographic phase microscopy,” Nat. Methods 4, 717–719 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haeberlé O, Belkebir K, Giovaninni H, and Sentenac A, “Tomographic diffractive microscopy: basics, techniques and perspectives,” J. Mod. Opt 57, 686–699 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T, Zhou R, Mir M, Babacan SD, Carney PS, Goddard LL, and Popescu G, “White-light diffraction tomography of unlabelled live cells,” Nat. Photonics 8, 256–263 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T, Zhou R, Goddard LL, and Popescu G, “Solving inverse scattering problems in biological samples by quantitative phase imaging,” Laser Photon. Rev 10, 13–39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, Hee MR, Flotte T, Gregory K, and Puliafito CA, “Optical coherence tomography,” Science (New York, N.Y.) 254, 1178–1181 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White WM, Rajadhyaksha M, González S, Fabian RL, and Anderson RR, “Noninvasive imaging of human oral mucosa in vivo by confocal reflectance microscopy,” Laryngoscope 109, 1709–1717 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertz J, Introduction to Optical Microscopy (1st Edition) Solution Set (Roberts, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford TN, Chu KK, and Mertz J, “Phase-gradient microscopy in thick tissue with oblique back-illumination,” Nat. Methods 9, 1195–1197 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta SB and Sheppard CJR, “Partially coherent image formation in differential interference contrast (DIC) microscope,” Opt. Express 16, 19462–19479 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preza C, King SV, Dragomir NM, and Cogswell CJ, Phase Imaging Microscopy: Beyond Dark-Field, Phase Contrast, and Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy (CRC Press, 2016), Chap. 24, pp. 438–515. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledwig P, Sghayyer M, Kurtzberg J, and Robles FE, “Dual-wavelength oblique back-illumination microscopy for the non-invasive imaging and quantification of blood in collection and storage bags,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 2743–2754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casteleiro Costa P, Ledwig P, Bergquist A, Kurtzberg J, and Robles FE, “Noninvasive white blood cell quantification in umbilical cord blood collection bags with quantitative oblique back-illumination microscopy,” Transfusion 60, 588–597 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman JW, Introduction to Fourier Optics (Roberts & Co, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheppard C and Choudhury A, “Image formation in the scanning microscope,” Opt. Acta 24, 1051–1073 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigo JA and Alieva T, “Rapid quantitative phase imaging for partially coherent light microscopy,” Opt. Express 22, 13472–13483 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streibl N, “Three-dimensional imaging by a microscope,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2, 121–127 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Born M, Wolf E, Bhatia AB, Clemmow PC, Gabor D, Stokes AR, Taylor AM, Wayman PA, and Wilcock WL, Principles of Optics (Cambridge University, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bao Y and Gaylord TK, “Clarification and unification of the obliquity factor in diffraction and scattering theories: discussion,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 34, 1738–1745 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao Y and Gaylord TK, “Quantitative phase imaging method based on an analytical nonparaxial partially coherent phase optical transfer function,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 33, 2125–2236 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCutchen CW, “Generalized aperture and the three-dimensional diffraction image,” J. Opt. Soc. Am 54, 240–244 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheppard CJR and Mao XQ, “Three-dimensional imaging in a microscope,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 6, 1260–1269 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheppard CJR and Larkin KG, “Wigner function for nonparaxial wave fields,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 18, 2486–2490 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang Q and Boas DA, “Monte Carlo simulation of photon migration in 3D turbid media accelerated by graphics processing units,” Opt. Express 17, 20178–20190 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacques SL and Pogue BW, “Tutorial on diffuse light transport,” J. Biomed. Opt 13, 041302 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen M, Tian L, and Waller L, “3D differential phase contrast microscopy,” Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 3940–3950 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian L and Waller L, “3D intensity and phase imaging from light field measurements in an LED array microscope,” Optica 2, 104–111 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan SH, Wang X, and Elgendy OA, “Plug-and-play ADMM for image restoration: fixed-point convergence and applications,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 3, 84–98 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raju M and Unni SN, “Concentration-dependent correlated scattering properties of Intralipid 20% dilutions,” Appl. Opt 56, 1157–1166 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon CE, “A mathematical theory of communication,” Bell Syst. Tech. J 27, 379–423 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plog BA and Nedergaard M, “The glymphatic system in central nervous system health and disease: past, present, and future,” Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis 13, 379–394 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim J, Lee K, Jin KH, Shin S, Lee S, Park Y, and Ye JC, “Comparative study of iterative reconstruction algorithms for missing cone problems in optical diffraction tomography,” Opt. Express 23, 16933–16948 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen TH, Kandel ME, Rubessa M, Wheeler MB, and Popescu G, “Gradient light interference microscopy for 3D imaging of unlabeled specimens,” Nat. Commun 8, 210 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kandel ME, Hu C, Naseri Kouzehgarani G, Min E, Sullivan KM, Kong H, Li JM, Robson DN, Gillette MU, Best-Popescu C, and Popescu G, “Epi-illumination gradient light interference microscopy for imaging opaque structures,” Nat. Commun 10, 4691 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim J, Ayoub AB, Antoine EE, and Psaltis D, “High-fidelity optical diffraction tomography of multiple scattering samples,” Light Sci. Appl 8, 1–12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi H, Cha J, and So P, “Nonlinear optical microscopy for biology and medicine,” in Handbook of Biomedical Optics (CRC Press, 2011), pp. 561–588. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigo JA, Soto JM, and Alieva T, “Fast label-free microscopy technique for 3D dynamic quantitative imaging of living cells,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 5507–5517 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.