Abstract

Electromyographic biofeedback (EMG-BF) can be regarded as an adjuvant to pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training (PFMT) for the management of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). This meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy of PFMT with and without EMG-BF on the cure and improvement rate, PFM strength, urinary incontinence score, and quality of sexual life for the treatment of SUI or pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Wanfang, and CNKI were systematically searched for studies published up to January 2021. The outcomes were the cure and improvement rate, symptom-related score, pelvic floor muscle strength change, and sexual life quality. Twenty-one studies (comprising 1967 patients with EMG-BF + PFMT and 1898 with PFMT) were included. Compared with PFMT, EMG-BF + PFMT had benefits regarding the cure and improvement rate in SUI (OR 4.82, 95% CI 2.21–10.51, P < 0.001; I2 = 85.3%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) and in PFD (OR 2.81, 95% CI 2.04–3.86, P < 0.001; I2 = 13.1%, Pheterogeneity = 0.331), and in quality of life using the I-QOL tool (SMD 1.47, 95% CI 0.69–2.26, P < 0.001; I2 = 90.1%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001), quality of sexual life using the FSFI tool (SMD 2.86, 95% CI 0.47–5.25, P = 0.019; I2 = 98.7%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001), urinary incontinence using the ICI-Q-SF tool (SMD − 0.62, 95% CI − 1.16, − 0.08, P = 0.024), PFM strength (SMD 1.72, 95% CI 1.08–2.35, P < 0.001; I2 = 91.4%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001), and urodynamics using Qmax (SMD 0.84, 95% CI 0.57–1.10, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.420) and MUCP (SMD 1.54, 95% CI 0.66–2.43, P = 0.001; I2 = 81.8%, Pheterogeneity = 0.019). There was limited evidence of publication bias. PFMT combined with EMG-BF achieves better outcomes than PFMT alone in SUI or PFD management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-021-01831-6.

Keywords: Electromyographic biofeedback, Meta-analysis, Pelvic floor dysfunction, Pelvic floor muscle training, Stress urinary incontinence

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Electromyographic biofeedback (EMG-BF) can be regarded as an adjuvant to pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) for the management of stress urinary incontinence. |

| This meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy of PFMT with and without EMG-BF on the cure and improvement rate, PFM strength, urinary incontinence score, and quality of sexual life for the treatment of SUI or PFD. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| PFMT combined with EMG-BF achieves better outcomes than PFMT alone in SUI or PFD management. Still, randomized controlled trials in different countries are still necessary to confirm the results. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14787660.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine and affects approximately 50% of women at some point in their lifetime, with an increasing incidence in older age [1–5]. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) occurs during physical exertion, effort, coughing, or sneezing [1]. In women under 65 years old, SUI is slightly more common, whereas women over 65 years old are more likely to have mixed incontinence. Deficient or inadequate pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function is an etiological factor in SUI development [6–9]. Urinary incontinence directly impacts the quality of life, general and sexual, in women [5, 10]. If left unmanaged, urinary incontinence is more likely to worsen than improve [11].

Conservative treatment, recommended by the International Continence Society as first-line therapy, consists of an assessment of pelvic floor strength and functional use of PFM training (PFMT) [4, 5, 12–14]. PFMT increases the contraction and holding strength, coordination, velocity, and endurance of the PFMs to keep the bladder elevated during rises in intra-abdominal pressure, maintain adequate urethral closure pressure, and support and stabilize the pelvic organs [4, 12–14].

Furthermore, clinicians can assess the myoelectric activation of these muscle groups and train them using electromyographic biofeedback (EMG-BF) [15, 16]. EMG-BF can be regarded as an adjuvant to PFMT and is designed to assess muscle integrity and to allow both patient and physical therapist to observe correct PFM contraction and relaxation, thus facilitating neuromuscular learning or re-adaptation in the setting of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) [15, 16]. A meta-analysis in 2011 suggested that EMG-BF might benefit PFMT but that additional studies were required [16]. Since 2011, new studies were published around the world.

This meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy of PFMT with and without EMG-BF on the cure and improvement rate, PFM strength, urinary incontinence score, and quality of sexual life for the treatment of SUI or PFD.

Methods

Literature Search

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17]. PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Wanfang, and CNKI were systematically searched for studies published up to January 2021 using the MeSH terms of “Pelvic Floor Disorders”, “Urinary Incontinence, Stress”, and “Women”, and “electromyographic biofeedback”, “female”, as well as relevant keywords. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were (1) diagnosis of SUI or PFD, (2) intervention and control: BF + PFMT vs. PFMT, (3) outcomes: cure and improve rate, symptom-related score, pelvic floor muscle strength change, and sexual life quality, (4) study type: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or nonrandomized controlled trials (nRCTs), and (5) published in English or Chinese. The exclusion criteria were (1) overlapping publications, (2) single-arm study, case report, case series, or review, or (3) incomplete reported data for this meta-analysis.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The selection and inclusion of studies were performed in two stages by two independent reviewers (Yuping Lan and Xiaoli Wu). The retrieved records were first screened on the basis of the titles/abstracts, and the full-text papers were then examined for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (Xiu Zheng).

Data including authors, publication year, study design, country, sample size, mean age, diagnostic criteria, intervention methods, instrument model, follow-up, outcomes, radiographic outcomes, and criteria for success were extracted by two authors (Xiaoli Wu and Xiaohong Yi). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third author (Ping Lai).

The risk of bias of the RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [18]. The nRCTs were assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool [19].

Statistical Analysis

The odds ratios (ORs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine the value of dichotomous data. Continuous data were evaluated using standardized mean differences (STDs) and their corresponding 95% CIs using the Mantel–Haenszel method. In all cases, P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to obtain a solid conclusion and to evaluate the stability of the results. Cochran’s Q statistic (P < 0.10 indicated evidence of heterogeneity) was used to assess heterogeneity among studies [20]. When significant heterogeneity (P < 0.10) was observed, the random-effects model was used to combine the effect sizes of the included studies; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was adopted [18]. All analyses were performed using STATA SE 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

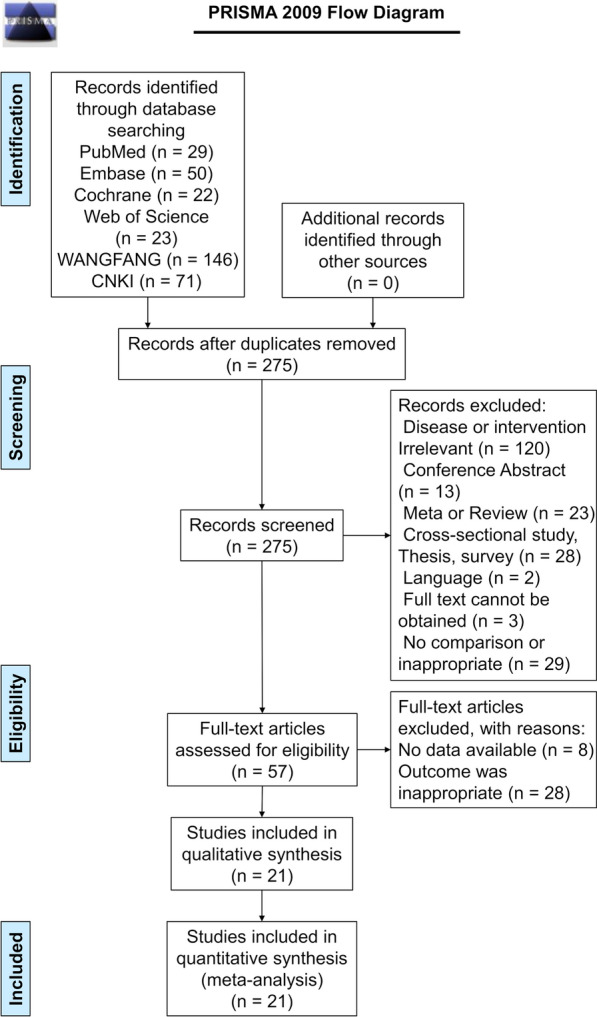

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the search process. The initial search yielded 341 records. After removal of the duplicates, 275 records were screened, and 218 were excluded. Then, 57 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 36 were excluded (missing data, n = 8; inappropriate outcome, n = 28).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search process and included studies

Finally, 21 studies were included (Table 1). There were 13 RCTs and eight nRCTs. Seventeen studies were from China, two from Europe, one from Brazil, and one from Turkey. A total of 1967 patients received EMG-BF + PFMT, and 1898 received PFMT alone. When reported, the studies used different diagnostic criteria for SUI and PFD and used different EMG-BF instruments. The follow-up also varied from 1 month to 2 years. Table 2 presents the quality assessment of the included studies. Among the RCTs, six had one item with a high risk of bias, and seven had at least one item with an unclear risk of bias. All eight nRCTs had at least one item with a moderate risk of bias.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Region | Study design | Age (years, mean, or range) I/C | Simple size I/C | Diagnosis SUI/PFD | Intervention I/C |

Stimulation instrument | Follow-up (months) | Definition of cure and improvement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding, 2020 [25] | China | RCT | 26.3 ± 3.6/26.8 ± 4.3 | 50/50 | PFM strength screening | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | AM 3000 | 6 | – | |

| Hagen, 2020 [15] | UK | RCT | 48.2 ± 11.6/47.3 ± 11.4 | 300/300 | Clinically diagnosed | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | – | 6, 12, 24 | Cure (never or no responses to ICIQ-UI SF frequency or quantity items) and improvement in urinary incontinence (reduction in ICIQ-UI SF score of ≥ 3 points) |

| Lan, 2020 [26] | China | RCT | 28.65 ± 2.73/28.7 ± 2.68 | 150/150 | – | – | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | – | 6 | PFM strength score > 4 or 3–4 |

| Li, 2020 [27] | China | RCT | 28.41 ± 2.33/28.46 ± 2.47 | 145/145 | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | – | 2 | Significant effect: grade > 4, > 80 points; effective grade 2–3, 60–80 points | |

| Liu, 2020 [28] | China | RCT | 31.82 ± 4.67/32.38 ± 5.14 | 40/40 | Diagnostic criteria | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | PHENIX USB4 | 2 |

Cured (urinary incontinence completely disappeared, no leakage of urine during coughing, laughing and exercise) Effective (the perceived frequency and quantity of urine leakage were improved) |

| Zeng, 2020 [29] | China | RCT | 34.4 ± 2.9/34.5 ± 2.8 | 36/36 | – | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | SOKO 900 III | 2 | Significant effect: clinical symptoms disappeared and indicators returned to normal; effective: symptoms improved and indicators improved |

| Ge, 2019 [30] | China | RCT | 29.65 ± 3.26/30.21 ± 3.52 | 90/90 | Diagnostic criteria | – | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | Laborie | 1 | – |

| Bertotto, 2017 [31] | Brazil | RCT | 58.4 ± 6.8/59.3 ± 4.9 | 16/15 | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | Miotool 400 system | 1 | – | |

| Özlü, 2017 [32] | Turkey | RCT | 42.22 ± 8.88/42.82 ± 6.30 | 35/18 | Urodynamically confirmed diagnoses of SUI | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | Enraf Nonius Myomed 932 device | 1, 2 |

1-h pad test, 2 g and under of it is considered as a cure The improvement was assessed in terms of 50% and more reduction in wet weight compared to baseline measurements in the 1-h pad test |

| Fang, 2016 [23] | China | RCT | 59.09 ± 15.86/59.17 ± 15.62 | 40/40 | 72 h urination record, routine urine examination, urine dynamic examination, PFM strength test | – | eBF + Vaginal dumbbell | Vaginal dumbbell | PHENIX USB4 | – | Significant effect, PFM strength reached level 5. No urinary incontinence occurred; effective, PFM strength reached grade 4 or increased by 50%, and urinary incontinence was reduced |

| Yao, 2015 [21] | China | RCT | 28.84 ± 3.36/29.13 ± 3.39 | 45/43 | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | PHENIX USB8 | 3 | – | |

| Ji, 2013 [33] | China | RCT | – | 80/80 | Gynecological examination, nervous system examination, stress test, finger pressure test, cotton swab test, and urodynamic examination | – | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | PHENIX | – | Cure: symptoms disappeared, urinary incontinence disappeared, urination normal, no leakage of urine; Significant effect: symptom relief |

| Ding, 2012 [34] | China | RCT | 50.1 ± 7.63/52.1 ± 6.96 | 48/48 | Clinically diagnosed | – | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | AM 1000B | 10 | Cure (urinary incontinence symptoms disappeared) Improvement (reduce the number of urine leakage by > 50%) |

| Chmielewska, 2019 [35] | Poland | PCS | 52.9 ± 4/51.5 ± 5.2 | 18/13 | Clinically diagnosed | – | eBF + PFMT | Pilates exercises | – | 2, 6 | – |

| Shen, 2017 [36] | China | PCS | 38.6 ± 7.2/38.8 ± 7.2 | 500/500 | – | PFM strength screening | eBF + Vaginal dumbbell | Vaginal dumbbell | – | 6 | Increase the muscle strength of type I and II muscle fibers by 2 grades or more |

| Yang, 2017 [37] | China | PCS | 36.55 ± 1.24/36.25 ± 1.34 | 45/45 | – | Clinically diagnose | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | SOKO 900 III | 2 | Significant effect: the clinical symptoms and various indicators are obviously restored or normal; effective: the clinical symptoms and various indicators are somewhat restored |

| Cai, 2014 [38] | China | PCS | – | 32/24 | 72 h urination record, routine urine examination, urine dynamic examination, PFM strength test | – | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | UROSTYM | 4.8 |

1-h pad test, 2 g and under of it is considered as a cure The improvement was assessed in terms of 50% and more reduction in wet weight compared to baseline measurements in the 1-h pad test |

| Yang, 2014 [39] | China | PCS | – | 90/78 | Medical history and urological examination | – | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | PHENIX | 2 | Cure (urinary incontinence symptoms disappeared) Improvement (reduce the number of urine leakage by > 50%) |

| Xuan, 2019 [40] | China | RCS | 46.3 ± 7.7/45.3 ± 8.2 | 72/48 | Clinically diagnosed | eBF + Kegel | Kegel | – | – |

1-h pad test, 2 g and under of it is considered as a cure The improvement was assessed in terms of 50% and more reduction in wet weight compared to baseline measurements in the 1-h pad test |

|

| Ma, 2018 [41] | China | RCS | 28.5 ± 2.8/29.4 ± 3.7 | 110/110 | – | PFM strength | eBF + vaginal dumbbell | Vaginal dumbbell | Medtronics-Synetics | – | Significant effect: pelvic floor muscle contraction is complete, and can be maintained for more than 5 s, and the body is in good condition; effective: after treatment, the pelvic floor muscles contracted completely and slightly against each other. The number of times was 2–4 and the time was 2-4 s. The physical state was stable |

| Xiao, 2018 [22] | China | RCS | 47.29 ± 10.36/47.25 ± 10.24 | 25/25 | Clinically diagnosed | eBF + PFMT | PFMT | UROSTIM | – | Cure (urinary incontinence symptoms disappeared) Improvement (reduced the number of urine leakage by > 50%) | |

I/C intervention/control, SUI stress urinary incontinence, PFD pelvic floor dysfunction, eBF electronic biofeedback stimulator, PFMT pelvic floor muscle training, RCT randomized controlled trial, PCS prospective comparative study, RCS retrospective comparative study

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies

| RCT study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding, 2020 [25] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Hagen, 2020 [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Lan, 2020 [26] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Li, 2020 [27] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Liu, 2020 [28] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Zeng, 2020 [29] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Ge, 2019 [30] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Bertotto, 2017 [31] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Özlü, 2017 [32] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Fang, 2016 [23] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Yao, 2015 [21] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Ji, 2013 [42] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Ding, 2012 [34] | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| nRCT study | Bias due to confounding | Bias in selection of participants | Bias in classification of interventions | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data | Bias in measurement of outcomes | Bias in selection of the reported result | Overall bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chmielewska, 2019 [35] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Shen, 2017 [36] | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Yang, 2017 [37] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Cai, 2014 [38] | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Yang, 2014 [39] | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Xuan, 2019 [40] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Ma, 2018 [41] | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Xiao, 2018 [22] | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

Cure and Improvement Rate

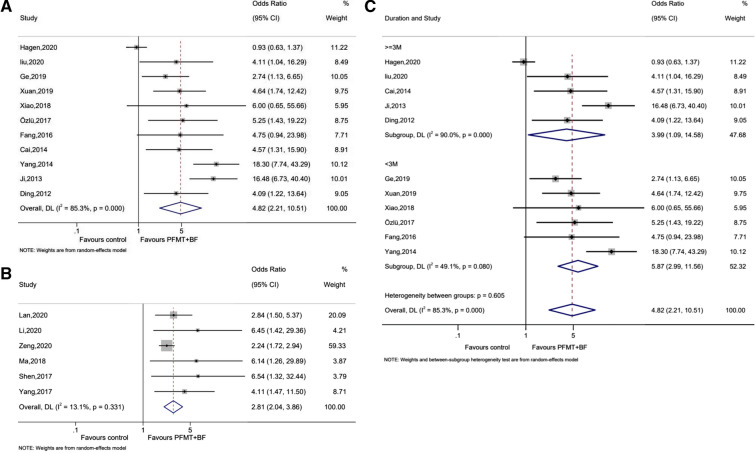

Eleven studies reported the cure and improvement rate of SUI. There was a significant difference between the two groups, favoring EMG-BF + PFMT in patients with SUI (OR 4.82, 95% CI 2.21–10.51, P < 0.001; I2 = 85.3%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). The analysis of six studies showed a significant benefit with EMG-BF + PFMT in PFD (OR 2.81, 95% CI 2.04–3.86, P < 0.001; I2 = 13.1%, Pheterogeneity = 0.331) (Fig. 2B). Then, a subgroup analysis of the cure and improvement rate of SUI was performed according to follow-up. Five studies reported a follow-up of at least 3 months, and six studies reported a follow-up of less than 3 months. In both cases, there was a benefit of EMG-BF + PFMT in women with SUI (at least 3 months: OR 3.99, 95% CI 1.09–14.58, P = 0.036; I2 = 90.0%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001; less than 3 months: OR 5.87, 95% CI 2.99–11.56, P ≤ 0.001; I2 = 49.1%, Pheterogeneity = 0.080) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the cure and improvement rate. A Stress urinary incontinence. B Pelvic floor dysfunction. C Subgroup analysis of stress urinary incontinence (> 3 months and ≤ 3 months)

Quality of Life

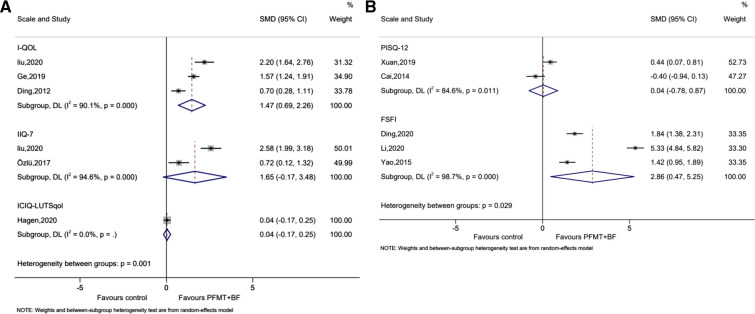

Six studies reported quality of life, using three different tools (I-QOL, IIQ-7, and ICIQ-LUTSqol). The three studies that used I-QOL showed benefits of EMG-BF + PFMT on quality of life (SMD 1.47, 95% CI 0.69–2.26, P < 0.001; I2 = 90.1%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). The two studies and one study that used IIQ-7 and ICIQ-LUTSqol, respectively, did not report significant differences between the two groups (SMD 1.65, 95% CI − 0.17 to 3.48, P = 0.076; I2 = 94.6%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001; SMD 0.04, 95% CI − 0.17 to 0.25, P = 0.376) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of the quality of life score. A Urinary incontinence quality of life. B Quality of sexual life

Five studies reported the quality of sexual life, using the PISQ-12 and the FSFI. Two studies used the PISQ-12 and showed no difference between the two groups (SMD 0.04, 95% CI − 0.78 to 0.87, P = 0.919; I2 = 84.6%, Pheterogeneity = 0.011) (Fig. 3B). Three studies used the FSFI and showed a benefit of EMG-BF + PFMT on the quality of sexual life (SMD 2.86, 95% CI 0.47–5.25, P = 0.019; I2 = 98.7%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 3B).

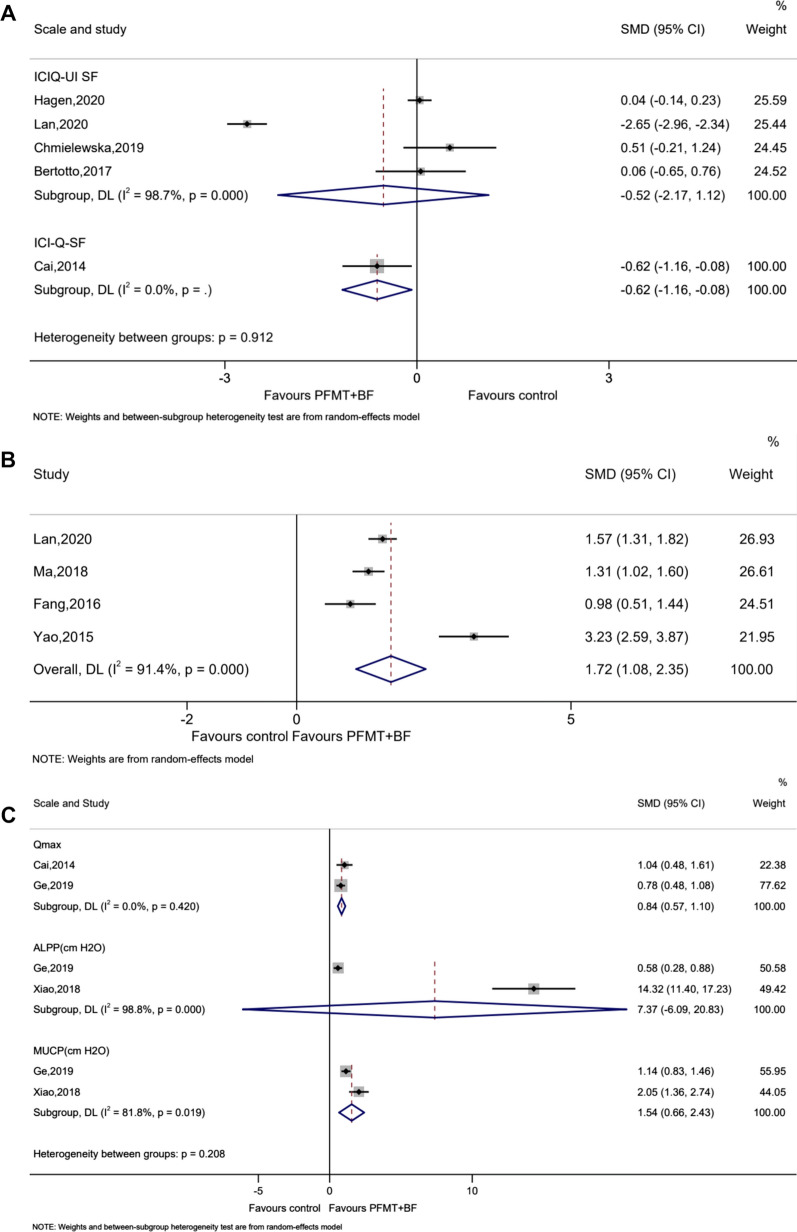

Severity of Urinary Incontinence, PFM Strength, and Urodynamics

Five studies reported the severity of urinary incontinence, using either the ICIQ-UI SF or the ICI-Q-SF scale. For the ICIQ-UI SF, the pooled data showed no significant difference between the two groups (SMD − 0.52, 95% CI − 2.17, 1.12, P = 0.532; I2 = 98.7%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). For ICI-Q-SF, the pooled data showed a significant difference between the two groups in favor of EMG-BF + PFMT (SMD − 0.62, 95% CI − 1.16, − 0.08, P = 0.024) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of A the severity of urinary incontinence, B pelvic floor muscle strength, and C urodynamics

Four studies reported PFM strength. The pooled data showed benefits of EMG-BF + PFMT (SMD 1.72, 95% CI 1.08–2.35, P < 0.001; I2 = 91.4%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

Six studies reported the urodynamics using three indicators (Qmax, ALPP, and MUCP). For Qmax and MUCP the pooled data showed benefits of EMG-BF + PFMT (Qmax: SMD 0.84, 95% CI 0.57–1.10, P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.420; MUCP: SMD 1.54, 95% CI 0.66–2.43, P = 0.001; I2 = 81.8%, Pheterogeneity = 0.019) (Fig. 4C). For ALPP, the pooled data showed no significant difference between the two groups (SMD 7.37, 95% CI − 6.09–20.83, P = 0.283; I2 = 98.8%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001) (Fig. 4C).

Publication Bias

There was limited evidence of publication bias (Supplementary Fig. S1A), as suggested by Begg’s test (P = 0.062) and Egger’s test (P = 0.034). Supplementary Fig. S1B also shows the trim and fill analysis.

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis showed that the sequential exclusion of each study did not influence the outcomes regarding the effective rate (Supplementary Fig. S2A) and the cure and improvement rate (Supplementary Fig. S2B), and the analyses were robust. For the analysis of PFM strength, excluding the study by Yao et al. [21] significantly changed the results, but not the conclusion of the analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

Discussion

EMG-BF can be regarded as an adjuvant to PFMT to manage SUI or PFD [15, 16]. This meta-analysis aimed to summarize the recent literature comparing the efficacy of PFMT with and without EMG-BF on the cure and improvement rate, PFM strength, urinary incontinence score, and quality of sexual life for the treatment of SUI or PFD. The results showed that EMG-BF + PFMT improved the cure and improvement rate, quality of life using the I-QOL tool, quality of sexual life using the FSFI tool, urinary incontinence using the ICI-Q-SF tool, PFM strength, and urodynamics using Qmax and MUCP.

A Cochrane review published in 2011 suggested that EMG-BF + PFMT benefited women with urinary incontinence, but that further evidence was still needed [16]. Still, this previous meta-analysis was not limited to SUI and included all women with urinary incontinence. Since the different types of urinary incontinence have different pathogenic mechanisms [1–5], the inclusion of all types probably biased the results. The present meta-analysis only included SUI/PFD, which could help refine the results. It showed that EMG-BF + PFMT had benefits over PFMT alone regarding the outcomes of SUI/PFD, concordant with the previous meta-analysis [16], although with different patient populations and different outcomes.

Nevertheless, these benefits of EMG-BF + PFMT are not observed in all included studies. Three studies reported no benefit of EMG-BF + PFMT on the cure and improvement rate [15, 22, 23]. Two of these studies still reported a tendency toward a benefit of EMG-BF + PFMT [22, 23], while Hagen et al. [15] showed no tendency toward a benefit of EMG-BF + PFMT on the cure and improvement rate, quality of life, and urinary incontinence. The reasons why are difficult to determine since no particular characteristics of the study or the patient population differentiate that study from the others. Still, among the 21 included studies, only three were negative, and the publication bias analysis suggested the possible presence of such bias. Hence, additional studies are still necessary to confirm the benefits of EMG-BG + PFMT on SUI.

Nevertheless, the benefits of EMG-BF are not based on any direct effect of EMG-BF on the PFMs, but rather indicate the activity of the PFMs and aim to improve the teaching of the adequate contraction techniques by showing the patients the actual activity of their PFMs in real time. Therefore, it has the indirect effects of motivating them and increasing their adherence to the PFMT. PFMT alone is already known to improve SUI/PFD [24]. Thus, EMG-BF could be an adjunct management method to PFMT. It could also increase the patients’ empowerment toward their condition and increase their sense of control, which could help them manage their symptoms. Indeed, Hagen et al. [15] showed that the self-efficacy of the EMG-BF + PFMT group was higher than in the PFMT group.

This meta-analysis has limitations. First and foremost, heterogeneity was high for nearly all analyses. That is probably due to the use of different diagnostic criteria for SUI and PFD, the use of different protocols and devices for EMG-BF, and different definitions of treatment success. In addition, different tools were used for the assessment of the quality of life, sexual quality of life, and urodynamic indicators, including qualitative and quantitative assessments, severely limiting the meta-analyses for these outcomes because of the lack of direct comparability among the different tools. In addition, different results were observed with different tools for the same outcome (e.g., quality of sexual life), probably because of the questionnaires’ constructs. Third, most of the included studies were from China, which could introduce some bias. It could be that EMG-BF is more popular in China, but this might constitute a bias since the physicians would have more experience with the treatment. Fourth, studies in languages other than English and Chinese were excluded, possibly excluding useful and precious data. Finally, this meta-analysis was not registered.

Conclusions

PFMT combined with EMG-BF achieves better outcomes than PFMT alone in SUI or PFD management. Still, RCTs in different countries are still necessary to confirm the results.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. S1 (A) Funnel plot of cure and improvement rate. (B) Trim and fill analysis of cure and improvement rate (TIF 243 KB)

Supplementary Fig. S2 Sensitivity analysis of cure and improvement rate (TIF 258 KB)

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by the 2018 Panzhihua Municipal Science and Technology Plan Project and Financial Science and Technology Special Fund [grant number 2018CY-S-11].

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xiaoli Wu, Xiu Zheng, Xiaohong, Yi Ping Lai and Yuping Lan. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xiaoli Wu and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Xiaoli Wu, Xiu Zheng, Xiaohong Yi, Ping Lai and Yuping Lan have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:141–148. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds WS, Dmochowski RR, Penson DF. Epidemiology of stress urinary incontinence in women. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:370–376. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, et al. Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:429–440. doi: 10.7326/M13-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 155: urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e66–e81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardozo L, Chapple CR, Dmochowski R, et al. Urinary urgency—translating the evidence base into daily clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1675–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osman NI, Li Marzi V, Cornu JN, Drake MJ. Evaluation and classification of stress urinary incontinence: current concepts and future directions. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oelke M, De Wachter S, Drake MJ, et al. A practical approach to the management of nocturia. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(11):e13027. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Tannenbaum C, Thorpe KE, Straus SE. What type of urinary incontinence does this woman have? JAMA. 2008;299:1446–1456. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatton B, de Tayrac R, Costa P. Stress urinary incontinence and LUTS in women–effects on sexual function. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:565–578. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lifford KL, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. The epidemiology of urinary incontinence in older women: incidence, progression, and remission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD007471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritel X, de Tayrac R, Bader G, et al. Preventing urinary incontinence with supervised prenatal pelvic floor exercises: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:370–377. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkhard FC, Bosch JLHR, Cruz F, et al. EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence in adults. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagen S, Elders A, Stratton S, et al. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training with and without electromyographic biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020;371:m3719. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herderschee R, Hay-Smith EJ, Herbison GP, Roovers JP, Heineman MJ. Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selcuk AA. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;57:57–58. doi: 10.5152/tao.2019.4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. London: Cochrane Collaboration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao Q, Xu X, Liu Y, Zeng B, Liao B. The function of biofeedback-electrical stimulation-pelvic floor muscle exercise on the quality of sexual life in postpartum women. Health Med Res Pract. 2015;12:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao G. Effect of functional electrical stimulation combined with biofeedback pelvic floor muscle exercise in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Inner Mongolia J Tradit Chin Med. 2018;37:80–81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang K. Feasibility study of biofeedback and electrical stimulation therapy for female stress urinary incontinence. China Modern Med. 2016;23:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding X, Wang L, Chen X. Effects of pelvic floor electromyography biofeedback therapy on postpartum pelvic floor muscle strength and sexual function in primiparas. China Modern Doctor. 2020;58:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan Q. Analyze the effect of biofeedback electrical stimulation treatment on the improvement and recovery of pelvic floor function after delivery. Women’s Health Res. 2020;14–5.

- 27.Li Y, Dong L, Zhu Q. Effect of electrical stimulation biofeedback therapy on functional rehabilitation of postpartum women’s pelvic floor muscles. China Foreign Med Treat. 2020;39:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Zhou W, Li L, Zhang L, Li Q, Wang E. The fate of inverted limbus in children with developmental dysplasia of the hip: clinical observation. J Orthop Res. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jor.24864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng X. Effect of electrostimulation biofeedback therapy combined with pelvic floor muscle exercise in the treatment of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Jilin Med J. 2020;41:1941–1942. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge J, Ye H, Pu W, et al. Effect of rehabilitation training combined with biofeedback and electrical stimulation on postpartum stress urinary incontinence. Chin J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;20:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertotto A, Schvartzman R, Uchôa S, Wender MCO. Effect of electromyographic biofeedback as an add-on to pelvic floor muscle exercises on neuromuscular outcomes and quality of life in postmenopausal women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:2142–2147. doi: 10.1002/nau.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Özlü A, Yıldız N, Öztekin Ö. Comparison of the efficacy of perineal and intravaginal biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle exercises in women with urodynamic stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:2132–2141. doi: 10.1002/nau.23257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jing J. Clinical study of female stress urinary incontinence treated by biofeedback electrical stimulation of pelvic floor muscle: 80 cases. Chin Remedies Clin. 2013;13:499–501. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding C, Ma L, Sun Y. A comparative study of the effect of biofeedback electrical stimulation combined with pelvic floor muscle exercises and simple pelvic floor muscle exercises on female stress urinary incontinence. Acta Acad Med Weifang. 2012;34:417–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chmielewska D, Stania M, Kucab-Klich K, et al. Electromyographic characteristics of pelvic floor muscles in women with stress urinary incontinence following sEMG-assisted biofeedback training and Pilates exercises. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen F. Clinical effect of electrostimulation biofeedback combined with pelvic floor muscle exercise in 500 cases of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Med Front. 2017;7:201–202. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H. Efficacy of electrostimulation biofeedback therapy combined with pelvic floor muscle exercise in female patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. J Med Theory Pract. 2017;30:3535–3537. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai Y, Zhao X, Wang Y, Zheng L, Liu J. Observation on the curative effect of biofeedback combined with electrical stimulation in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Maternal Child Health Care China. 2014;29:4661–4664. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Pang J, Gong M. Curative effect of treating postpartum stress urinary incontinence with electrogymnastics and biofeedback. Modern Med J. 2014;42:1034–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xuan J, Lou C, Qiu Y. Efficacy of biofeedback combined with electrical stimulation in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Zhejiang J Traumatic Surg. 2019;24:35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma X, Liu Y, Lv Y, Shang L, Zhang L. Efficacy of electrostimulation biofeedback therapy combined with pelvic floor muscle exercise in the treatment of female pelvic floor dysfunction and the effect on POP-Q. Maternal Child Health Care China. 2018;33:3378–3380. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji J. Clinical study of female stress urinary incontinence treated by biofeedback electrical stimulation of pelvic floor muscle: 80 cases. Chin Remedies Clin. 2013;13:499–501. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S1 (A) Funnel plot of cure and improvement rate. (B) Trim and fill analysis of cure and improvement rate (TIF 243 KB)

Supplementary Fig. S2 Sensitivity analysis of cure and improvement rate (TIF 258 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.