Abstract

Background

Anaemia is a condition where the number of red blood cells (and consequently their oxygen‐carrying capacity) is insufficient to meet the body's physiological needs. Fortification of wheat flour is deemed a useful strategy to reduce anaemia in populations.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of wheat flour fortification with iron alone or with other vitamins and minerals on anaemia, iron status and health‐related outcomes in populations over two years of age.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, 21 other databases and two trials registers up to 21 July 2020, together with contacting key organisations to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included cluster‐ or individually‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) carried out among the general population from any country, aged two years and above. The interventions were fortification of wheat flour with iron alone or in combination with other micronutrients. We included trials comparing any type of food item prepared from flour fortified with iron of any variety of wheat

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the search results and assessed the eligibility of studies for inclusion, extracted data from included studies and assessed risks of bias. We followed Cochrane methods in this review.

Main results

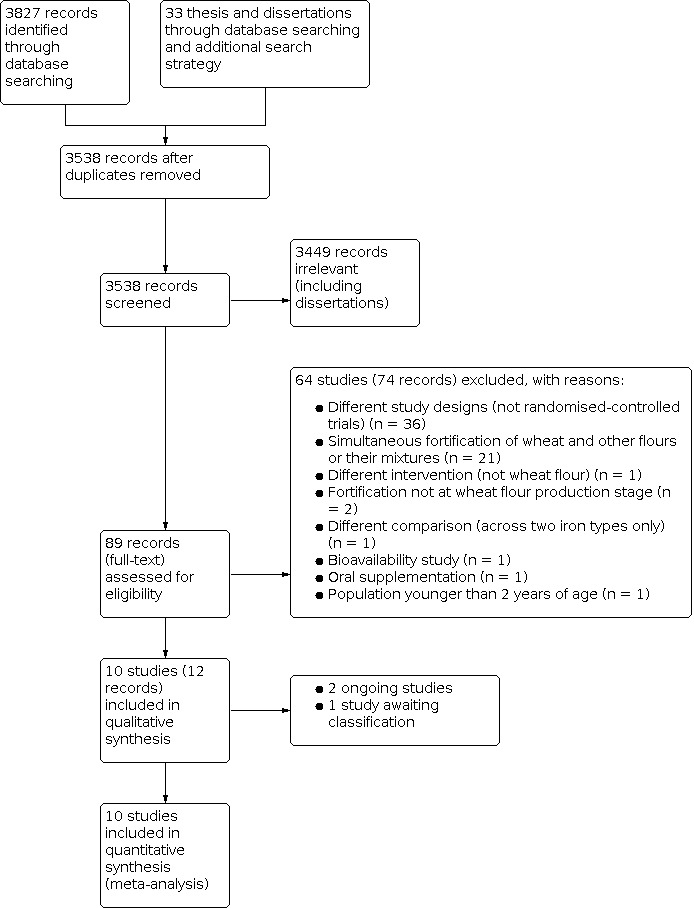

Our search identified 3538 records, after removing duplicates. We included 10 trials, involving 3319 participants, carried out in Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Kuwait, Philippines, South Africa and Sri Lanka. We identified two ongoing studies and one study is awaiting classification. The duration of interventions varied from 3 to 24 months. One study was carried out among adult women and one trial among both children and nonpregnant women. Most of the included trials were assessed as low or unclear risk of bias for key elements of selection, performance or reporting bias.

Three trials used 41 mg to 60 mg iron/kg flour, three trials used less than 40 mg iron/kg and three trials used more than 60 mg iron/kg flour. One trial used various iron levels based on type of iron used: 80 mg/kg for electrolytic and reduced iron and 40 mg/kg for ferrous fumarate.

All included studies contributed data for the meta‐analyses.

Iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added versus wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added

Iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added versus wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added may reduce by 27% the risk of anaemia in populations (risk ratio (RR) 0.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 0.97; 5 studies, 2315 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain whether iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients reduces iron deficiency (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.04; 3 studies, 748 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or increases haemoglobin concentrations (in g/L) (mean difference MD 2.75, 95% CI 0.71 to 4.80; 8 studies, 2831 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

No trials reported data on adverse effects in children (including constipation, nausea, vomiting, heartburn or diarrhoea), except for risk of infection or inflammation at the individual level. The intervention probably makes little or no difference to the risk of Infection or inflammation at individual level as measured by C‐reactive protein (CRP) (mean difference (MD) 0.04, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.11; 2 studies, 558 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Iron‐fortified wheat flour with other micronutrients added versus unfortified wheat flour (nil micronutrients added)

It is unclear whether wheat flour fortified with iron, in combination with other micronutrients decreases anaemia (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.46; 2 studies, 317 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The intervention probably reduces the risk of iron deficiency (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.99; 3 studies, 382 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and it is unclear whether it increases average haemoglobin concentrations (MD 2.53, 95% CI −0.39 to 5.45; 4 studies, 532 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

No trials reported data on adverse effects in children.

Nine out of 10 trials reported sources of funding, with most having multiple sources. Funding source does not appear to have distorted the results in any of the assessed trials.

Authors' conclusions

Fortification of wheat flour with iron (in comparison to unfortified flour, or where both groups received the same other micronutrients) may reduce anaemia in the general population above two years of age, but its effects on other outcomes are uncertain.

Iron‐fortified wheat flour in combination with other micronutrients, in comparison with unfortified flour, probably reduces iron deficiency, but its effects on other outcomes are uncertain.

None of the included trials reported data on adverse side effects except for risk of infection or inflammation at the individual level. The effects of this intervention on other health outcomes are unclear. Future studies at low risk of bias should aim to measure all important outcomes, and to further investigate which variants of fortification, including the role of other micronutrients as well as types of iron fortification, are more effective, and for whom.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Infant; Male; Middle Aged; Young Adult; Anemia; Anemia/blood; Anemia/diet therapy; Edetic Acid; Edetic Acid/administration & dosage; Ferric Compounds; Ferric Compounds/administration & dosage; Ferrous Compounds; Ferrous Compounds/administration & dosage; Flour; Food, Fortified; Fumarates; Hemoglobin A; Hemoglobin A/analysis; Iron; Iron/administration & dosage; Iron Deficiencies; Micronutrients; Micronutrients/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Triticum

Plain language summary

Does adding iron to wheat flour reduce anaemia and increase iron levels in the general population?

Why do we need iron in our diet?

Iron is an essential mineral found in every cell of the body. It is needed to make haemoglobin, the oxygen‐carrying protein in the blood. Iron molecules in haemoglobin bind to oxygen and carry it from the lungs to all the cells and tissues in the body. Low levels of haemoglobin means the body does not get enough oxygen.

Anaemia develops when haemoglobin levels in the blood fall too low. Symptoms of anaemia include: tiredness and lack of energy, getting out of breath quickly, pale skin and a greater susceptibility to infections.

Low haemoglobin levels can be caused by blood loss, pregnancy or not eating enough foods containing iron (iron‐deficiency anaemia). Iron‐deficiency anaemia may be treated by taking iron tablets or eating foods rich in iron.

Fortified foods

Adding micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) to foods, whether those micronutrients were originally present or not, is called fortification. Fortifying foods is one way to improve nutrition in a population.

People living in low‐income countries may not have enough iron in their diet, and may be at risk of anaemia. Adding iron and other nutrients to foods routinely eaten in large quantities, such as flour, is thought to help prevent iron‐deficiency anaemia.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to find out how adding iron, and other minerals and vitamins, to wheat flour affected the blood iron levels of the general population, and whether fewer people developed anaemia or other health conditions. We also wanted to know if adding iron to wheat flour caused any unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated eating any types of food made with wheat flour containing added iron, or foods made with wheat flour without added iron. We then compared the studies with each other, to find out the effects of adding iron to wheat flour on people's health and the levels of iron and haemoglobin in their blood.

Search date: we included evidence published up to 21 July 2020.

What we found

We found 10 studies in 3319 people (aged 2 years and older). The studies lasted from 3 months to 24 months, and took place in Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Kuwait, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and South Africa.

The studies looked at the effects of:

· wheat flour containing added iron (with or without other minerals and vitamins) compared with wheat flour without added iron (but with the same other minerals and vitamins);

· wheat flour containing added iron and other minerals and vitamins compared with wheat flour without any added minerals or vitamins.

The wheat flours used in the studies contained different amounts of iron: from under 40 mg/kg to over 60 mg/kg.

We were interested in:

· how many people had anaemia (defined by low haemoglobin levels);

· how many people had low levels of iron in their blood (iron deficiency; tested using a biomarker);

· haemoglobin concentrations in people's blood;

· how many children had diarrhoea or respiratory infections;

· how many children died (of any cause);

· signs of infection or inflammation (the body's response to injury) in children (by testing a biomarker in the blood); and

· any unwanted effects.

Most studies had multiple sources of funding; some were partly funded by companies involved in the food, chemical or pharmaceutical industries.

What are the results of our review?

Compared with flour without added iron (but with other minerals and vitamins)

Flour containing added iron (with or without other minerals and vitamins):

· may reduce anaemia, by 27% (evidence from 5 studies, 2315 people); and

· probably makes no difference to children's risk of infection or inflammation (2 studies, 558 children).

It was unclear how flour with added iron affected iron deficiency (3 studies, 748 people), or haemoglobin levels (8 studies, 2831 people).

Compared with flour without any added minerals or vitamins

Flour containing added iron (with other minerals and vitamins) probably reduced iron deficiency (3 studies, 382 people). It was unclear from the studies how flour containing added iron affected anaemia (2 studies, 317 people) or haemoglobin levels (4 studies, 532 people).

No studies reported information about unwanted effects, or how many children died, or had diarrhoea or respiratory infections.

Our confidence in our results

Our confidence is moderate to low that adding iron to flour probably reduces iron deficiency and anaemia. The studies appeared to show fewer people with iron deficiency and slightly higher haemoglobin levels associated with flour with added iron, but the results varied widely, so we are uncertain about the effect. These results might change if further evidence becomes available. We found limitations in the ways some of the studies were designed and conducted, and this could have affected their results.

Key messages

Adding iron to wheat flour may lead to fewer people with anaemia or low blood‐iron levels in the general population.

We do not know if adding iron to wheat flour causes any unwanted effects, because no studies looked at these.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added versus wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added.

| Iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added versus wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population of all age groups (including pregnant women) from any country, over two years of age Setting: any country (studies providing data for this comparison: Brazil, India, Kuwait, Pakistan, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka) Intervention: iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added Comparison: wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with flour ± micronutrients (no iron). | Risk with wheat flour ± micronutrients + iron | |||||

|

Anaemia (defined as haemoglobin below WHO cut‐off for age and adjusted for altitude as appropriate) follow‐up: range 3 months to 24 months |

231 per 1000a | 169 per 1000 (127 to 224) | RR 0.73 (0.55 to 0.97) | 2315 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb.c | Included studies: Barbosa 2012 (C); Cabalda 2009; Dad 2017; Muthayya 2012; Nestel 2004 (C); data for Barbosa 2012 (C); Nestel 2004 (C) are adjusted for clustering effect |

|

Iron deficiency (as defined by study authors, based on a biomarker of iron status) follow‐up: range 5.5 months to 8 months |

543 per 1000a | 250 per 1000 (109 to 565) | RR 0.46 (0.20 to 1.04) | 748 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd,e,f | Included studies: Biebinger 2009; Cabalda 2009; Muthayya 2012 |

|

Haemoglobin concentration (g/L) follow‐up: range 3 months to 24 months |

The mean haemoglobin concentration was 122.63 g/La | The mean haemoglobin concentration was 2.75 g/L higher (0.71 higher to 4.80 higher) |

‐ | 2831 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW e,g,h | Included studies: Amalrajan 2012; Barbosa 2012 (C); Biebinger 2009; Cabalda 2009; Dad 2017; Muthayya 2012; Nestel 2004 (C); Van Stuijvenberg 2008; data for Barbosa 2012 (C); Nestel 2004 (C) are adjusted for clustering effect |

| Diarrhoea (3 liquid stools in a single day) (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| Respiratory infections (as measured by trialists) (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| All‐cause death (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| Infection or inflammation at individual level as measured by C‐reactive protein (CRP) (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) follow up: mean 7 months | The mean CRP was 123.5a | The mean CRP was 0.04 higher (0.02 lower to 0.11 higher) | ‐ | 558 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEi | Included studies: Amalrajan 2012; Muthayya 2012 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aMean of control group values across studies included in the meta‐analysis. bDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design or execution (risk of bias). Two studies included for this outcome were at low overall risk of bias and three studies were at high risk. cDowngraded 1 level for indirectness. Of the five studies contributing data for this outcome, three were conducted in children or adolescents. Only one study was conducted among pre‐school‐age children (9 ‐ 71 months of age); school‐age children (6 ‐ 11 years of age); adult, non‐pregnant women. dDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design and execution (risk of bias). Most of the information from results came from studies at overall high risk of bias, which lowers our confidence in the estimate of the effect. eDowngraded 1 level for inconsistency (heterogeneity measured as I2 > 80%). fDowngraded 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals consistent with the possibility of either a decrease or increase in the outcome). gDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design or execution (risk of bias). Most of the information for this outcome came from studies considered to have an overall high risk of bias sufficient to affect the interpretation. Two studies were at low overall risk of bias, but five studies were at high risk. hDowngraded 1 level for indirectness. The prevalence of anaemia at baseline varied among the trials, being low (< 20%) in one trial; moderate 20% ‐ 39%) in three trials, and high in two trials. One trial did not specify the prevalence of anaemia at baseline. Mos studies were conducted in children. iDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design and execution. Only two studies provided information for this assessment and one was considered to have overall high risk of bias, lowering our confidence in the results.

Summary of findings 2. Iron‐fortified wheat flour with other micronutrients added versus unfortified wheat flour (no micronutrients added).

| Iron‐fortified wheat flour with other micronutrients added versus unfortified wheat flour (no micronutrients added) | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population of all age groups (including pregnant women) from any country, over two years of age Setting: any country (studies providing data for this comparison: Bangladesh, Kuwait and Philippines) Intervention: Iron‐fortified wheat flour with other micronutrients Comparison: unfortified wheat flour (no micronutrients added) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with unfortified wheat flour (no micronutrients added) | Risk with wheat flour fortified with iron in combination with other micronutrients | |||||

|

Anaemia (defined as haemoglobin below WHO cut‐off for age and adjusted for altitude as appropriate) follow‐up: range 6 months to 8 months |

281 per 1000a | 216 per 1000 (115 to 410) | RR 0.77 (0.41 to 1.46) | 317 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW b,c,d | Included studies: Cabalda 2009; Rahman 2015 (C) |

|

Iron deficiency (as defined by study authors, based on a biomarker of iron status) follow‐up: range 5.5 months to 8 months |

355 per 1000a | 259 per 1000 (192 to 352) | RR 0.73 (0.54 to 0.99) | 382 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEe | Included studies: Biebinger 2009; Cabalda 2009; Rahman 2015 (C) |

|

Haemoglobin concentration (g/L) follow‐up: range 5.5 months to 8 months |

The mean haemoglobin concentration was 123.08 g/La | The mean haemoglobin concentration was 2.53 g/L higher (0.39 lower to 5.45 higher) |

‐ | 532 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd,e,f | Included studies: Biebinger 2009; Cabalda 2009; Rahman 2015 (C); Van Stuijvenberg 2006 |

| Diarrhoea (3 liquid stools in a single day) (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome. |

| Respiratory infections (as measured by trialists) (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| All‐cause death (only in children 2 to 11 years of age) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| Infection or inflammation at individual level (as measured by urinary neopterin, C‐reactive protein or alpha‐1‐acid glycoprotein variant A) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No study reported on this outcome |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aMean of control group values across studies included in the meta‐analysis. bDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design or execution (risk of bias). The two studies contributing information were considered as having overall high risk of bias. cDowngraded 1 level for indirectness. The studies were conducted in children, in settings with high or moderate prevalence of anaemia. dDowngraded 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals consistent with the possibility of either a decrease or increase in the outcome). eDowngraded 1 level for limitations in the study design or execution (risk of bias). All three studies contributing information were considered to have overall high risk of bias sufficient to affect the interpretation of the results. fDowngraded 1 level for indirectness. One study included adult participants who were already iron‐deficient and another on children who were already anaemic.

Background

Description of the condition

Anaemia is a condition in which the number of red blood cells (and consequently their oxygen‐carrying capacity) is insufficient to meet the body's physiological needs. Specific physiological needs vary with a person's age, sex, residential elevation above sea level (altitude), smoking behaviour, and different stages of pregnancy. Haemoglobin concentrations are used for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of its severity (WHO 2011a; WHO 2017). Anaemia results when there is an imbalance between production and the destruction of erythrocytes (Chaparro 2019; Schnall 2000). Similarly, iron deficiency occurs when physiological demands for iron are not met due to inadequate intake, absorption or utilisation, or due to excessive losses. Several processes lead to iron‐deficiency anaemia, starting with a decrease in body iron stores, an impaired supply of iron to tissues, a sustained shortage of iron leading to iron‐deficient erythropoiesis, and finally an inadequate supply of ferrous iron for haemoglobin synthesis (Camaschella 2017; Chaparro 2019; Cook 1999).

Although iron deficiency is the most common cause of anaemia globally, other nutritional deficiencies (particularly folate, vitamin B12, vitamin A, copper); parasitic infections (including malaria, helminthes, schistosomes (i.e. hookworms and others)); chronic infection‐associated inflammation; and genetic disorders, such as common haemoglobinopathies like sickle cell disease, can all cause anaemia (WHO 2017). A high prevalence of anaemia is often found in low‐income countries, especially where infections such as malaria or hookworm are common. In addition, infection with HIV affects millions of people in the low‐ and middle‐income countries and may influence their iron status, but little is known about the acute phase response during HIV infection in the absence of opportunistic infection (WHO/CDC 2007; WHO 2017). In most settings, the relative contributions of these interacting factors are often unknown (Osorio 2002; WHO 2017). The red blood cell indices (mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular haemoglobin) are reduced in iron deficiency and can therefore help distinguish iron deficiency anaemia from some other causes, but they are not specific to iron deficiency, and can also be affected in the thalassaemic syndromes, which are common in many countries, and to some extent in the anaemia of infection and inflammation (Ganz 2019; Lynch 2012).

Haemoglobin concentrations alone cannot be used to diagnose iron deficiency. However, the concentration of haemoglobin should be measured, even though not all anaemia is caused by iron deficiency. For diagnosis of earlier stages of iron deficiency (before anaemia onset) several indicators are used. Currently available iron indicators permit a specific diagnosis of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in the clinical setting where other patient‐related information is available. However, these indicators are more difficult to interpret in populations from low‐ and middle‐income countries because anaemia is a multifactorial disease (Chaparro 2019; Lynch 2012). For example, the concentration of serum ferritin is positively correlated with the size of the total body iron stores in the absence of inflammation. Ferritin concentration is low in iron‐deficient individuals, regardless of confounding clinical conditions (Garcia‐Casal 2018b) and the laboratory methods most used to determine ferritin concentrations have comparable accuracy and performance (Garcia‐Casal 2018c). The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently updated their global evidence‐informed recommendations on the use of ferritin concentration for assessing iron status in a population and for monitoring and evaluating iron interventions (WHO 2020). A low serum ferritin value reflects depleted iron stores, but not necessarily the severity of the depletion as iron deficiency progresses (Lynch 2017; WHO 2011b). Serum ferritin concentrations are proportional to stainable marrow iron in healthy individuals and are an indicator of depleted iron stores in liver, spleen, and bone marrow (Dallman 1986; Lynch 2017). Serum ferritin is also an acute‐phase protein and therefore values may not reflect iron status accurately in the presence of infection, limiting its usefulness in developing countries where malaria, HIV disease and tuberculosis are prevalent (Thurnham 2012).

Transferrin receptor is primarily expressed on cell surfaces to allow uptake of circulating iron bound to transferrin into cells and it is increased when tissue iron supply is reduced (Lynch 2007; Lynch 2017). However, this marker can also be an indicator of erythropoietic drive, as it is increased in conditions of haemolysis during acute and chronic asymptomatic malaria infection (Stoltzfus 2017; Verhoef 2001) and in conditions like sickle cell disease (Lulla 2010).

Transferrin saturation, which is less affected by inflammation status, is widely used to assess inadequate iron supply to tissue despite its diurnal variation (Lynch 2017; Umbreit 2005). Iron‐deficient erythropoiesis can be measured using zinc protoporphyrin, a relatively simple and valid technique (Gibson 2005; Lynch 2017), which may differentiate between infants who benefit from iron supplementation versus those who do not in a malaria‐endemic settings (Sazawal 2006).

Finally, the ratio of logged serum ferritin to soluble transferrin receptor concentration allows for the combination of iron status and tissue iron supply to determine body iron stores (Cook 2003), and is reported in one study to reflect bone marrow iron stores even in the presence of malaria and other infections (Phiri 2009). Since most of these indicators to assess iron status are susceptible to inflammation, markers of the acute phase, such as C‐reactive protein or alpha‐1‐acid‐glycoprotein (Wieringa 2002), should be measured concomitantly (Lynch 2017; Stoltzfus 2017; WHO 2017).

Ferritin concentrations increase in response to iron‐related interventions and may be used to monitor and assess the impact of interventions on iron status (WHO 2020) and should be measured with the haemoglobin concentration in all programme evaluations (WHO 2017).

Epidemiology

The population groups most vulnerable to anaemia, as of 2016, include children under five years of age (41.7% with anaemia worldwide), particularly infants and children under two years; non‐pregnant women (15 to 49 years; 32.5% with anaemia worldwide); and pregnant women (40.1% with anaemia worldwide) (Stevens 2013; WHO 2019a). Iron deficiency, a primary cause of anaemia in many settings, is estimated to affect an even larger number of people – two billion (Chaparro 2019; WHO 2019b). For severe anaemia, the aetiology of this condition is 50% in non‐pregnant women and children and 60% in pregnant women (Stevens 2013), reflecting the increased iron requirements during pregnancy. However, since iron deficiency can occur without concomitant anaemia, population iron‐deficiency rates may be greater than those of anaemia (Zimmermann 2007). Furthermore, while the early stages of iron deficiency are often asymptomatic, functional consequences in the absence of anaemia may include increased maternal and perinatal mortality, low birth weight, impaired cognitive performance and poorer educational achievement as well as reduced work capacity (Beard 2006; Khan 2006), with serious economic impact on families and populations (Garcia‐Casal 2019; Horton 2007).

In low‐ and middle‐income countries, populations may experience a greater infectious burden and greater systemic inflammation, both of which can increase iron loss and concomitantly reduce iron absorption and utilisation (Prentice 2007; Weiss 2005). Moreover, in resource‐poor settings, demands for iron are less likely to be met through the diet, which is commonly plant‐based and low in bioavailable iron (Hurrell 2000; WHO 2017).

Description of the intervention

There are several strategies to prevent and/or treat iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia: dietary modification and diversification that aims to increase the content and bioavailability of iron in the diet (FAO/CAB International 2011); preventive or intermittent iron supplementation through tablets, syrups or drops; blood transfusion, indicated only for very severe anaemia; biofortification through conventional plant breeding or genetic engineering that increases the iron content or its bioavailability in edible plants and vegetables; and fortification with iron compounds of staple foods (typically maize, soy and wheat flour) at the point of production or milling (WHO/FAO 2006; WHO 2017). These are complementary interventions, some of which are population‐based while others are targeted at specific age groups or consumer groups. Deworming in conjunction with other interventions, such as malaria control interventions, can be effective in some situations in reducing anaemia and in increasing the efficacy of interventions that increase iron intakes (Spottiswoode 2012).

Mass large‐scale fortification of staple foods or condiments is a preventive strategy aimed at reducing the risk of developing iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia through increased dietary iron. This intervention aims to reduce pre‐existing iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia prevalence and is designed and implemented to reach a large proportion of the population ‐ the one that consumes the industrialised fortified product. Iron fortification can be, and often is, accompanied by fortification with other micronutrients (i.e. folic acid, vitamin B12 or vitamin C), which may or may not enhance the effectiveness of the intervention (Zimmermann 2007).

Mass, targeted or market‐driven food fortification with iron has been used with various vehicles: soy sauce, fish sauce, salt, milk, sugar, beverages, bouillon cubes, maize flour, and complementary foods (WHO/FAO 2006). Iron fortification of foods is associated with increased haemoglobin, improved iron status, and reduced anaemia across populations (Barkley 2015; Gera 2012).

Wheat flour is a staple food for bread‐baking and by far the most commonly used medium in large‐scale iron‐fortification programmes. There are over 80 countries with legislation to fortify wheat flour produced in industrial mills with vitamins and minerals (FFI 2017). In all countries where it is mandatory to fortify wheat flour, it is required that the flour includes at least iron and folic acid. The exceptions are Australia, which does not require iron, and Congo, Philippines, United Kingdom and Venezuela, which do not require folic acid (FFI 2020). Mandatory fortification of wheat flour was a key success in Morocco and Uzbekistan (Wirth 2012). Uzbekistan has wheat flour enriched with iron and folic acid at 50% of the nation's flour milling enterprises, with support provided by the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) grant administered by the World Bank (Wirth 2012). Through the national wheat flour fortification programme, ferrous sulphate and folic acid are added to all wheat flour produced under the national food subsidy programme for baladi bread, a traditional bread in Egypt reaching an estimated 50 million Egyptians on a daily basis (Elhakim 2012). In 2009, Kyrgyzstan introduced the law 'On the Enrichment of Bread Flour' that envisages a phased transition of all mills to mandatory production of enriched flour (FAO 2009b).

The benefit from and sustainability of an iron fortification programme depends not only on factors such as regular consumption of the chosen vehicle across the entire population, the quantity of added iron and its bioavailability, but also on the organisation of the industrial sector in a given country. The choice of the food vehicle should be based on consumption data to ensure that the vehicle is consumed throughout the population and in sufficient quantity such that a suitable and affordable fortificant can be added for bioavailability, sensorial stability, mixing properties, and cost constraints. More specifically, there must also be a balance between intake of the vehicle (wheat flour) and the amount of iron added to achieve an estimated effective daily iron absorption of about 1 to 2 mg per day (WHO 2009).

Wheat production, processing and flour preparation

Wheat is the third largest cereal crop produced in the world, after maize and rice, and the second most consumed in the diet after rice. It is estimated that about 65% of the global wheat crop is used for food, 17% is used for animal feed and 12% is used in industrial applications including bio‐fuel production (FAO 2013). Wheat varieties including hard/soft, winter/spring, and red, white, or durum are grown at a variety of altitudes and in various soil types throughout the world (FAO 2009a). All types belong to the genus Triticum aestivum, subspecies vulgare. In addition, three other species are cultivated and traded: the Triticum durum, compactum and spelta. Because of its quality, durum wheat is used by the pasta industry, and non‐durum is used either for milling, for livestock feed or for ethanol production.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is forecasting global wheat output at 761.7 million tonnes for 2020 (at a comparable level with that for the year 2019) (FAO 2020). Consumption of wheat is forecast to register 758 million tonnes in 2019/20 (FAO 2020). International wheat prices declined slightly over the course of 2019, with the benchmark United States wheat (No.2 hard red winter) ending around USD 220 per tonne (FAO 2019). The United States, the European Union, Canada, Australia and the former Soviet Union were the five top wheat exporters between 1980 and 2013. Developing countries consume 77% of wheat produced globally and are generally wheat importers, with wheat accounting for 24% of imported food commodities in these countries (Enghiad 2017).

Wheat kernels have three components: the bran, the germ, and the endosperm. Most wheat is milled into flour through the mechanical extraction of the endosperm, the core part of the kernel. The endosperm contains the bulk portion of the kernel's protein and carbohydrates (FAO 2009a). The cost of grain accounts for about 81% of the total cost of flour, while the rest of the cost is for electricity (6.5%), labour (4%), expendable materials and other costs (8.5%), according to the International Association of Operative Millers (FAO 2009a). Wheat flour is then used to prepare different breads that use methods for bread‐making that have been developed and adapted to consumer demands, such as conventional bread‐making, retarded proofing, interrupted proofing, frozen dough, frozen fermented dough and bake‐off technology (Rosell 2011). Bread‐making involves continuous biochemical, microbiological and organoleptic changes that result from the mechanical and thermal action, as well as the activity of the yeast, lactic acid bacteria and the endogenous enzymes.

The production of wheat flour is a complex, multi‐step process that depends upon the physical grinding and separation of the kernel components of wheat (more specifically, to isolate the protein‐ and carbohydrate‐containing endosperm) and subsequent sifting into flour (Van Der Borght 2005). The extent to which the flour is sifted to separate the fine‐grain endosperm is known as the extraction rate, with a higher extraction rate indicating higher retention of the bran and germ. Most of the vitamins and minerals from wheat are found in the bran or germ, and flours of 80% or lower extraction rates have a significantly reduced nutrient content. However, high‐extraction flour contains higher levels of phytates, which chelate minerals and thus interfere with intestinal absorption of iron (Kumar 2010).

Some products made with wheat flour may be leavened or unleavened. In India, wheat flour is used to produce unleavened flat bread such as the South Indian paro, naan and batura (Indrani 2011). Sourdough breads are also produced primarily in retail and artisan bakeries with wheat flour and water, using baker's yeast for dough leavening. Lactic acid, bacteria and yeast are responsible for the fermentation as well as for the aromatic precursors of bread (Catzeddu 2011). Composite wheat flours that include plantains, soybeans, tiger nuts, and breadfruits can be relevant for places with scarce resources for bread production, but at least 70% of wheat flour is required for good dough formation (Olaoye 2011).

How the intervention might work

The more the industrial sector of wheat flour is centralised, formalised and has established an efficient distribution system, the lower the costs associated with mass fortification. Local governments have a central role in regulatory enforcement, good manufacturing practices, distribution and control of the fortificant premix (Dary 2002). Together with an effective distribution system for wheat flour, this increases the accessibility and affordability of appropriately fortified wheat flour to the at‐risk population. It also limits the need to promote an active role for individuals to maintain adherence to the intervention itself.

The challenges of wheat flour fortification with iron relate to the bioavailability of the iron compound used, the sensory effects of the compound in the final wheat‐flour product, and/or the shelf stability of the compound in the flour or the final product, or both. For example, ferrous fumarate and ferrous sulphate are relatively bioavailable, but ferrous sulphate can affect product flavour, especially after long‐term storage and in the presence of fat (Dary 2002; Hurrell 2010). It is also important to consider wheat consumption patterns and the cost/feasibility of the fortification scheme when determining optimal iron fortificant levels in flour (Hurrell 2010). Although sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate is protected from chelation by phytates in high extraction‐rate wheat flour, it is considerably more costly than the other iron forms used for fortification (Hurrell 2010).

For wheat flour fortification, several iron compounds have been used over the years, but recently‐published recommendations suggest the following iron fortificants and levels, which also take into account wheat‐flour extraction rates and consumption levels (Hurrell 2010; WHO 2009).

For high‐extraction wheat flour (that has a high content of iron absorption inhibitors), the only recommended compound is sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate. Levels of addition depend on the daily per capita consumption: 15 parts per million (ppm) iron as sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate if daily consumption is over 300 g of wheat flour/day, 20 ppm if daily consumption is between 150 and 300 g per day, and 40 ppm if consumption is below 150 g/day.

Ferrous sulphate and fumarate can be used with low extraction‐rate flour: 20 ppm iron for flour intake above 300 g/day; 30 ppm iron for flour intake between 150 and 300 g/day and 60 ppm iron for intake below 150 g/day.

Sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate, ferrous sulphate and ferrous fumarate are first choices as iron fortificants. The use of electrolytic iron, which can be used for low‐extraction flours, is now discouraged (Hurrell 2010).

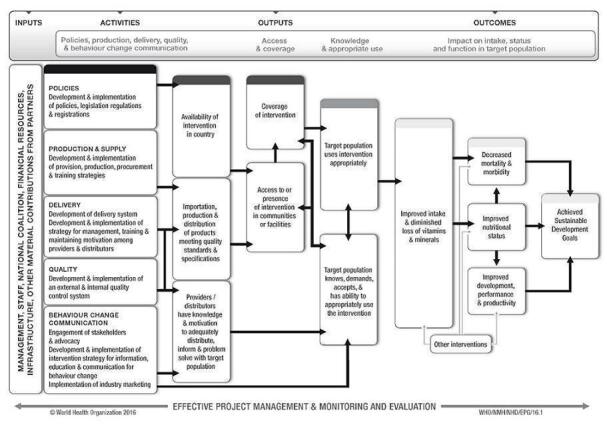

This review aims to assess the effects of wheat‐flour fortification with iron as a public health intervention. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (WHO/CDC) logic model for micronutrient interventions in public health depicts the programme theory and plausible relationships between inputs and expected improvement in Sustainable Development Goals (WHO 2018). This model can be adapted to different contexts (De‐Regil 2014). The effectiveness of wheat‐flour fortification with iron in public health depends on several factors related to policies and legislation regulations; production and supply of the fortified maize flour; the development of delivery systems for the fortified wheat flour; the development and implementation of external and internal food‐quality control systems; and the development and implementation of strategies for information, education and communication for behaviour change among consumers (WHO 2011c). A generic logic model for micronutrient interventions that depicts these processes and outcomes is presented in Figure 1.

1.

WHO/CDC generic logic model for micronutrient interventions (with permission from WHO)

Risks of wheat‐flour fortification with iron

As is the case with any fortification or supplementation programme involving iron, the largest potential risk of the programme is secondary iron overload in certain individuals of the given fortified population (Pasricha 2018). Iron overload is observed in individuals who have heritable iron metabolism disorders which cause perturbed iron absorption or storage, or both, leading to iron accumulation to subsequent tissue damage, most commonly in the liver, pancreas and endocrine organs (Sousa 2020). The most common iron overload disorder is associated with mutations in the HFE gene, the gene for hereditary haemochromatosis. Other physiological conditions are also associated with iron overload, including, thalassaemia, pyruvate kinase deficiency, and glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, among others (Andrews 2000; Garcia‐Casal 2018a).

Why it is important to do this review

Iron deficiency is one of the most common micronutrient deficiencies worldwide, and iron‐deficiency anaemia affects billions of people in all countries (Chaparro 2019; Zimmermann 2007). Fortification of staple foods with iron is thought to be a feasible, well‐tolerated and potentially very effective strategy to prevent and reduce iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia (Garcia‐Casal 2018a; WHO/FAO 2006). Wheat flour is a staple food for baking in a large number of countries, and is therefore considered one of the best vehicles for fortification with iron and with other vitamins and minerals. Since wheat‐flour fortification is a complex intervention, a variety of study designs across a range of settings and amongst diverse populations are needed to adequately measure success and to develop policies for improving the health of diverse populations. The generalisability of findings remains crucial. Several studies have been conducted to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of wheat flour fortification with iron to reduce iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia (Darnton‐Hill 1999; Hurrell 2000; Mannar 2002; Nestel 2004 (C); Zimmermann 2005a), but results from both experimental and observational studies have not been systematically summarised.

This review is an update of a previously published version (Field 2020).

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of wheat flour fortification with iron alone or with other vitamins and minerals (vitamin A, zinc, folic acid, others) on anaemia, iron status and health‐related outcomes in populations over two years of age.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included the following study designs.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with randomisation at either the individual or cluster level;

Quasi‐RCTs (where allocation of treatment has been made, for example, by alternate allocation, date of birth, alphabetical order, or other means).

RCTs can provide information on whether iron‐fortified wheat flour can effectively achieve changes in health outcomes and anaemia, iron deficiency, or vitamin and mineral status for those receiving the intervention. Food fortification is, however, an intervention that aims to reach large sections of the population and is frequently delivered through the food system. We used only RCTs to assess the efficacy of wheat fortification in reducing the prevalence of anaemia. Hence we excluded non‐RCTs and observational studies from this review. This change is reported in Differences between protocol and review..

Types of participants

General population of all age groups (including pregnant women) from any country, and over two years of age. If any study included participants aged under two years and also had more than half of its population in the two‐years and above category, we included such studies in this review. We excluded studies of interventions targeted at participants with a pre‐diagnosed critical illness or severe co‐morbidities.

Types of interventions

We include any form of iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients, compared to wheat flour with no iron.

Standard criteria and terminology for fortification interventions has been used since January 1970 (Finch 1972). We thus considered any form of wheat flour iron fortification independently of length of intervention, extraction rate of wheat flour, iron compounds used, preparation of the iron‐flour premix, and fortification levels achieved in the wheat flour or derivative foods.

We considered any wheat flour for direct human consumption, prepared from common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), or club wheat (Triticum compactum Host.), or mixtures thereof (Codex Alimentarius 1995); durum wheat semolina, including whole durum wheat semolina and durum wheat flour prepared from durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) (Codex Alimentarius 1991), as well as products prepared with these flours. We included composite flours that contained more than 70% wheat flour within the definition of wheat flour in this review.

We excluded studies with wheat flour destined for use as a brewing adjunct or for the manufacture of starch or gluten or both, or flours whose protein content had been reduced or which had been submitted after the milling process to a special treatment other than drying or bleaching.

We only included studies where the fortification occurred at the production stage of food items (e.g. biscuits, bread rolls) made with the fortified wheat flour (fortification at flour stage). In a previous version we assessed different comparisons, but in this updated version we focus only on two comparisons:

Comparisons include the following:

Iron‐fortified wheat flour with or without other micronutrients added versus wheat flour (no added iron) with the same other micronutrients added;

Iron‐fortified wheat flour with other micronutrients added versus unfortified wheat flour (nil micronutrients added).

We include studies with co‐interventions (e.g. education, deworming) only if all compared groups received the same co‐interventions.

We excluded studies comparing iron‐fortified wheat flour with other forms of micronutrient interventions, i.e. iron supplementation (De‐Regil 2011; Finkelstein 2018; Low 2016), dietary diversification, point‐of‐use fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders (De‐Regil 2017), biofortification of crops (Garcia‐Casal 2016) or the effects of the iron fortification of other food vehicles (Garcia‐Casal 2018a; Peña‐Rosas 2019; Self 2012). We also excluded fortification of wheat flours with other micronutrients (Centeno Tablante 2019; Hombali 2019; Santos 2019; Shah 2016), as these topics are covered in other systematic reviews or protocols.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes considered across all populations in this review are the presence of anaemia, iron deficiency and haemoglobin concentrations.

Anaemia (defined as haemoglobin below WHO cut‐off for age and adjusted for altitude as appropriate).

Iron deficiency (as defined by trialists, based on a biomarker of iron status).

Haemoglobin concentration (g/L).

For children aged 2 to 11 years, we also include the following primary outcomes.

Diarrhoea (three liquid stools in a single day).

Respiratory infections (as measured by trialists).

All‐cause death.

Infection or inflammation at individual level (as measured by urinary neopterin, C‐reactive protein or alpha‐1‐acid glycoprotein variant A).

Secondary outcomes

We considered the following secondary outcomes.

Anthropometric measures (height‐for‐age z‐score and weight‐for‐height z‐score for children, body mass index (BMI) for adults).

Risk of iron overload (defined as serum ferritin higher than 150 µg/L in women and higher than 200 µg/L in men) (WHO 2011b).

Cognitive development in children aged 2 to 11 years (as defined by trialists).

Motor skill development in children aged 2 to 11 years (as defined by trialists).

Clinical malaria (as defined by trialists).

Severe malaria (as defined by trialists).

Adverse side effects (including constipation, nausea, vomiting, heartburn or diarrhoea, as defined by trialists).

Search methods for identification of studies

We designed and piloted a structured search strategy. We carried out this search strategy to date in electronic databases, and hand searched relevant journals and publications to identify relevant primary studies and, where necessary, we contacted authors for unpublished/ongoing studies. We consulted institutions, agencies and experts in the fields about the results of our search and for any additional data (see Dealing with missing data).

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

International databases

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO) (21 July 2020);

MEDLINE (OVID; 1946 to 17 July 2020);

MEDLINE (R) In Process (OVID) 1946 to July week 4 2020 (21 July 2020);

Web of Science; Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index (SCI) (21 July 2020);

Embase (OVID; 1947 to 21 July 2020);

CINAHL EBSCOhost (1982 to 21 July 2020);

POPLINE (www.popline.org/; 16 April 2018) ‐ Database no longer exists;

BIOSIS (ISI; Previews to January 2020);

AGRICOLA (Ebsco; 1970 to 27 September 2019);

Food Science and Technology Abstracts (FSTA) 1969 to present (16 April 2018);

OpenGrey 1960 to present (16 April 2018);

Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI) (16 April 2018);

ClinicalTrials.gov (searched 21 July 2020)

The International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 21 July 2020);

We also contacted relevant organisations (July 2020) for the identification of ongoing and unpublished studies.

Regional databases

Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud (IBECS); ibecs.isciii.es; searched 21 July 2020

Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO); www.scielo.br; searched 21 July 2020

Global Index Medicus ‐ WHO African Region (AFRO) (includes African Index Medicus (AIM); www.globalhealthlibrary.net/php/index.php?lang=en); WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) (includes Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR); www.globalhealthlibrary.net/php/index.php?lang=en); searched 21 July 2020

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature); lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 21 July 2020

WHO Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Library; www1.paho.org/english/DD/IKM/LI/library.htm; searched 21 July 2020

WHO Library and Information Networks for Knowledge online catalogue (WHOLIS (WHO Library); dosei.who.int/); searched 21 July 2020

WPRIM (Western Pacific Region Index Medicus; www.wprim.org/); searched 21 July 2020

Index Medicus for South‐East Asia Region (IMSEAR; imsear.hellis.org); searched 21 July 2020

IndMED, Indian medical journals; medind.nic.in/imvw/; searched to 21 July 2020

Native Health Research Database; hslic-nhd.health.unm.edu; searched to 21 July 2020

For dissertations or theses, we searched WorldCat, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations and ProQuest‐Dissertations and Theses. We also contacted the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Public Health Group to search the Group's Specialised Register. The search used keywords and controlled vocabulary (when available), using the search strategy set out in Appendix 1 and adapting them as appropriate for each database. As wheat‐flour fortification technologies are relatively novel, we limited the search, from 1960 to present, for all databases.

We did not apply any language restrictions. If we identified articles written in a language other than English, we commissioned their translation into English. If this was not possible, we aimed to seek advice from the Cochrane Public Health Group. We aimed to categorise such articles as Studies awaiting classification until the availability of English translation. However, we did not find any studies screened in full‐text published in other languages.

Searching other resources

For assistance in identifying ongoing or unpublished studies, we contacted headquarters and regional offices of the WHO, the nutrition section of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Agency for International Development (USAID), Nutrition International (NI), the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), Hellen Keller International (HKI), Sight and Life Foundation, PATH, the Wright Group, premix producers DSM and BASF, and the Food Fortification Initiative (FFI) (July 2020).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MF, Diana Estevez (author on the first version of the review)) independently screened the titles and abstracts of articles retrieved by each search to assess eligibility, as determined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above in the initial search. Two review authors (PM, JPPR) independently screened the updated search results in September 2019, using the Covidence platform (Covidence 2018). We retrieved full‐text copies of all eligible papers for further evaluation when a title or abstract could not be rejected with certainty. If we could not access full‐text articles, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain further details of the study. Failing this, we classified such studies as Studies awaiting classification until further information is published or made available to us. We resolved any disagreements at any stage of the eligibility assessment process through discussion and consultation with a third review author (JPPR) in the initial search and with MF in the updated search in 2020, where necessary. A review author (JPPR) checked the excluded titles. We used a PRISMA flow diagram to summarise our study‐selection processes (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

For this updated version, two review authors (MF, PM) independently extracted data using the data extraction forms released by the Cochrane Public Health Group and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group (Cochrane EPOC Group 2013; Cochrane Public Health Group 2011).

All review authors were involved in piloting the form, using a subset of articles in order to enhance consistency amongst review authors; based on this, we modified the form. We collected information on study design, study setting, participants (number and characteristics) and provide a full description of the interventions examined. We also collected details of outcomes measured (including a description of how and when outcomes were measured) and study results.

The form was designed so that we were able to record results for our prespecified outcomes, as well as for other (non‐specified) outcomes (although such outcomes did not underpin any of our conclusions). We extracted additional items relating to study recruitment and the implementation of the intervention, including number of sites for an intervention, whether recruitment was similar at different sites, levels of compliance and use of condiments in different sites within studies, resources required for implementation, and whether a process evaluation was conducted. We used the PROGRESS plus (Place of Residence, Race/Ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic Status, and Social Capital) checklist (O'Neill 2013) to record whether or not outcome data had been reported by sociodemographic characteristics known to be important from an equity perspective. We also recorded whether or not studies included specific strategies to address diversity or disadvantage. We documented the sources of study funding (marked as 'unknown' if this information was not available and we were unable to obtain it on request from the authors).

We entered all data into the Cochrane Review Manager 5.4 software (Review Manager 2020), and checked them for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane EPOC Group 'RIsk of bias' tool for studies with a separate control group to assess the risks of bias of all studies (Cochrane EPOC Group 2013). This includes five domains of bias: selection, performance, attrition, detection and reporting, as well as an 'other bias' category to capture other potential threats to validity. The 'Risk of bias' assessment was made at the study level. We assessed each item to be at low, high, or unclear risk of bias (unclear bias corresponding to studies with insufficient information for judgement, despite all efforts to gather the information related to that domain), as set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). While justifying the judgement, we provided a quote from the study for each item in the 'Risk of bias' tables. In case of unclear data or missing information, we contacted the authors of included studies for clarification.

Two review authors (JPPR, MF) independently assessed risks of bias for each study and resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving an additional review author (PM).

Assessing risk of bias in randomised trials and quasi‐randomised trials

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed studies as:

low risk of bias if there is a random component in the sequence generation process (e.g. random‐number table; computer random‐number generator);

high risk of bias if a non‐random approach has been used (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number). Non‐randomised studies should be scored 'high';

unclear risk of bias if not specified in the paper.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed studies as:

low risk of bias if participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because an appropriate method was used to conceal allocation (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes). This rating was given to studies where the unit of allocation was by institution and allocation was performed on all units at the start of the study;

high risk of bias if participants of investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and potentially introduce selection bias (e.g. open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes);

unclear.

(3) Baseline outcome measurements similar

We assessed studies as:

low risk of bias if performance or patient outcomes were measured prior to the intervention, and no important differences were present across study groups. In randomised trials, score 'low risk' if imbalanced but appropriately‐adjusted analysis was performed (e.g. Analysis of covariance);

high risk of bias if important differences were present and not adjusted for in analysis;

unclear risk of bias if randomised trials have no baseline measure of outcome.

(4) Baseline characteristics similar

We assessed studies as:

low risk of bias if baseline characteristics of the study and control providers are reported and similar;

high risk of bias if there is no report of characteristics in text or tables or if there are differences between control and intervention providers. Note that in some cases imbalance in participant characteristics may be due to recruitment bias whereby the provider was responsible for recruiting participants into the trial;

unclear risk of bias if it is not clear in the paper (e.g. characteristics are mentioned in text but no data were presented).

(5) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We assessed the risk of performance bias associated with blinding as:

low risk of bias if there was blinding of participants and key study personnel and it was unlikely to have been broken;

high risk of bias if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding or if there was blinding that was likely to have been broken;

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We assessed the risk of detection bias associated with blinding as low, high or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessment as:

low risk of bias if there was blinding of the outcomes.

high risk of bias if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding or if there was blinding that was likely to have been broken and the outcome or outcome assessment was likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding.

unclear risk of bias.

(7) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts and protocol deviations)

We assessed outcomes in each included study as:

low risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data, which could be either that there were no missing outcome data or the missing outcome data were unlikely to bias the results based on the following considerations: study authors provided transparent documentation of participant flow throughout the study, the proportion of missing data was similar in the intervention and control groups, the reasons for missing data were provided and balanced across the intervention and control groups, the reasons for missing data were not likely to bias the results (e.g. moving house);

high risk of bias if missing outcome data was likely to bias the results. Studies will also receive this rating if an 'as‐treated' (per protocol) analysis is performed with substantial differences between the intervention received and that assigned at randomisation, or if potentially inappropriate methods for imputation have been used;

unclear risk of bias.

(8) Selective reporting bias

We assessed studies as:

low risk of bias if it is clear, either by availability of the study protocol or otherwise, that all prespecified outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported;

high risk of bias if it is clear that not all of the study's prespecified outcomes have been reported, or reported outcomes were not prespecified (unless justification for reporting is provided), or outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and cannot be used, or where one or more of the primary outcomes is reported using measurements or analysis methods that were not prespecified, or finally if the study report fails to include an important outcome that would be expected to have been reported;

unclear risk of bias.

(9) Other sources of bias

We detail other possible sources of bias (if any, for e.g. source of funding, protocol quality, etc) for each included study and give a rating of low, high or unclear risk of bias for this item.

Assessing risk of bias in cluster‐randomised trials

In addition to the domains mentioned above, the domains of 'Risk of bias' assessed for cluster‐randomised trials included recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and comparability with individually‐randomised trials. We assessed each domain to be at low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

We assessed included studies as follows.

(1) Recruitment bias

We assessed the risk of recruitment bias as:

low risk of bias if individuals were recruited to the trial before the clusters were randomised;

high risk of bias if individuals were recruited to the trial after the clusters were randomised;

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Baseline imbalance

We assessed the risk of baseline imbalance bias as:

low risk of bias if baseline characteristics were reported and were similar across clusters or if authors used stratified or pair‐matched randomisation of clusters;

high risk of bias if baseline characteristics were not reported or if there were differences across clusters;

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Loss of clusters

We assessed the risk of loss of clusters bias as:

low risk of bias if no complete clusters were lost or omitted from the analysis;

high risk of bias if complete clusters were lost or omitted from the analysis;

unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incorrect analysis

We assessed the risk of in correct analysis bias as:

low risk of bias if study authors appropriately accounted for clusters in the analysis or provided enough information for review authors to account for clusters in the meta‐analysis;

high risk of bias if study authors have not appropriately accounted for clusters in the analysis or did not provide enough information for review authors to account for clusters in the meta‐analysis;

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Compatibility with individual RCT

We assessed the risk of compatibility with individual RCT as:

low risk of bias if effects of the intervention were probably not altered by the unit of randomisation;

high risk of bias if effects of the intervention were likely altered by the unit of randomisation;

unclear risk of bias.

Overall risk of bias

For each of the included studies, we summarised the overall risk of bias by primary outcomes within that study. We rated studies at low risk of bias if they were assessed as low risk of bias in all of the following domains: allocation concealment, similarity of baseline outcome measurements, and incomplete outcome data. When the risk of bias in any of the domains was either high or unclear, we classified that study at high overall risk of bias. Judgements also considered the likely magnitude and direction of bias and whether it was likely to impact on the findings of the study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we present proportions and, for two‐group comparisons, we present results as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For continuous outcomes, we used the mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. Where some studies have reported endpoint data and others have reported changes from baseline data (with errors), we combined these in the meta‐analyses if the outcomes had been reported using the same scale.

We used standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs to combine trials that measured the same outcome (for example, haemoglobin) but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We combined results from both cluster‐ and individually‐randomised studies if there was little heterogeneity between the studies. If the authors of cluster‐randomised trials (C‐RCTs) conducted their analyses at a different level to that of allocation, and they had not appropriately accounted for the cluster design in their analyses, we calculated trials' effective sample sizes to account for the effect of clustering in those data. Whenever available, we used the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial. However, the Nestel 2004 (C) study did not report an ICC, so we took it as 0.02 from other sources (Adams 2004; Gulliford 1999), as recommended by Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions based on the cluster size, adjusted for baseline characteristics, at the 75th centile and then calculated the design effect with the formula provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020). We reported these adjusted values and then undertook sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of variations in ICC.

We extracted these parameters from the C‐RCT articles: type of outcome (haemoglobin, anaemia, and iron deficiency (ID)); number of control and intervention participants as well as sample size; mean and standard deviation (for continuous variables) or number of events and prevalence (dichotomous variables); description of methods used and study design; description of the clusters including average cluster size (M). We made the following assumptions: 1) the ICC for the outcome 'anaemia' was taken as the ICC for the outcome 'haemoglobin' (in the absence of a specific haemoglobin ICC); 2) the cluster type 'not‐for‐profit daycare' was taken as the same as 'postal code cluster' (in the absence of a not‐for‐profit daycare‐specific ICC) for Barbosa 2012 (C); and 3) for Rahman 2015 (C), the average number of children aged six years or above in the bari was considered as the mean cluster size. Finally, we corrected all quantities affected by the effective sample size (number of control and intervention samples, sample size etc.) due to cluster‐randomisation by dividing the corresponding quantity by the design effect. The details of adjustments for the design effect related to each of the included C‐RCTs are given in Characteristics of included studies.

Studies with more than two treatment groups

Where we identified studies with more than two intervention groups (multi‐arm studies), we combined groups where possible to create a single pair‐wise comparison or used the methods set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to avoid double‐counting study participants (Higgins 2020). If the control group was shared by two or more study arms, we divided the control group over the number of relevant subgroup categories to avoid double‐counting the participants; for dichotomous data, we divided the events and the total population, while for continuous data we assumed the same mean and standard deviation but divided the total population. We illustrate these details in the Characteristics of included studies tables. For the Nestel 2004 (C) trial, which had multiple arms of interventions and different study populations; the continuous variables were reported separately for each group within the population, so we computed the weighted average and included this in the pair‐wise analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We aimed to record missing outcome data and levels of attrition for included studies on the data extraction form. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, including all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial is the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined forest plots from meta‐analyses to visually determine the level of heterogeneity (in terms of the size or direction of treatment effect) between studies. We used T2, I2 and Chi2 statistics to quantify the level of heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. We regard substantial or considerable heterogeneity as T2 > 0 and either I2 > 30% or a low P value (< 0.10) in the Chi2 test. We noted this in the text and explored it using prespecified subgroup analyses mentioned below. We were cautious in our interpretation of those results with high levels of unexplained heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias, we attempted to contact study authors and asked them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results, using a sensitivity analysis.

We did not anticipate that there would be sufficient studies contributing data for any particular outcome for us to examine possible publication bias; if more than 10 studies reporting the same outcome of interest were available, we planned to generate funnel plots in Review Manager 2020, and to visually examine them for asymmetry. Where we pooled studies in a meta‐analysis, we ordered them by weight, so that a visual examination of forest plots allowed us to assess whether the results from smaller and larger studies were similar, or if there were any apparent differences by study size.

Data synthesis

We carried out meta‐analyses to provide an overall estimate of treatment effect when one or more studies examined the same intervention, provided that studies used similar methods and measured the same outcome in similar ways and in similar populations. We used random‐effects model meta‐analyses (Borenstein 2009) for combining data, as we anticipated that there may be natural heterogeneity among studies attributable to the different doses, durations, populations, and implementation or delivery strategies. For continuous variables, we used the inverse‐variance method, while for dichotomous variables we used the Mantel‐Haenzel model (Mantel‐Haenszel 1959).

Guided by the data extraction form for the ways in which studies may be grouped and summarised as well as by an equity perspective based on the PROGRESS framework (Oliver 2008), we used narrative synthesis to describe the outcomes, explore intervention processes, and describe the impact of interventions by sociodemographic characteristics.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses address whether the summary effects vary by specific (usually clinical) characteristics of the included studies or their participants.

We considered the following subgroups:

Prevalence of anaemia at baseline in the target group: less than 20% versus 20% to 39% versus 40% or higher versus mixed/unknown;

Type of iron compound: high relative bioavailability (e.g. iron ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) versus ferrous sulphate and comparable relative bioavailability (e.g. fumarate) versus low relative bioavailability (e.g. reduced iron, electrolytic iron, others);

Estimated wheat flour available per capita: less than 75 g/day versus 75 to 149 g/day versus 150 to 300 g/day versus more versus unknown/unreported;

Malaria endemicity at the time that the trial was conducted: malaria setting versus non/unknown malaria setting;

Duration of intervention: less than six months versus six months to one year versus more than one year;

Flour extraction rate: 80% or less versus more than 80% versus unknown/unreported;

Amount of elemental iron added to flour: 40 mg/kg or less versus 41 to 60 mg/kg versus more than 60 mg/kg versus unreported/unknown;

By iron alone versus no iron or in iron in combination with other micronutrients compared to other micronutrients but no iron (only for comparison 1, isolating the effect of iron).

We examined differences between subgroups by visual inspection of the CIs (non‐overlapping CIs suggesting a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups), and a statistical test for subgroup effects. We conducted analyses in Review Manager 2020. We limited our subgroup analyses to those primary outcomes for which two or more trials contributed data to each subgroup.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis to examine:

The effects of removing trials at high risk of bias (trials with poor or unclear allocation concealment and either blinding or high/imbalanced loss to follow‐up) from the analysis;

The effects of different intra‐cluster correlation (ICC) values for cluster‐randomised controlled trials on the overall effect estimate (Table 3);

Source of funding (industry versus non‐industry funding of study).

1. Sensitivity analysis of the cluster RCTs with different ICCs.

| Outcome (all studies included in the analysis) | Study (ICC) | RR (95% CI) | Tau² | Chi² | P value | I² (%) |

|

Anaemia ‐ Comparison 1 (Barbosa 2012 (C); Cabalda 2009; Dad 2017; Muthayya 2012; Nestel 2004 (C)) (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.97; 5 studies, 2315 participants; Tau2 = 0.05; Chi2 = 9.09, df = 4; P = 0.06; I2 = 56%) |

Barbosa 2012 (C) (0) | 0.74 [0.56 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 8.81 | 0.07 | 55 |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.001) | 0.74 [0.56 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 8.79 | 0.07 | 54 | |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.002) | 0.74 [0.56 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 8.78 | 0.07 | 54 | |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.005) | 0.73 [0.56 to 0.95] | 0.05 | 8.44 | 0.05 | 53 | |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.01) | 0.73 [0.56 to 0.95] | 0.04 | 8.40 | 0.08 | 52 | |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.02723) | 0.73 [0.55 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 9.09 | 0.06 | 56 | |

| Barbosa 2012 (C) (0.1) | 0.72 [0.55 to 0.96] | 0.05 | 8.62 | 0.07 | 54 | |

| Nestel 2004 (C) (0) | 0.73 [0.55 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 9.05 | 0.06 | 56 | |

| Nestel 2004 (C) (0.001) | 0.73 [0.55 to 0.97] | 0.05 | 9.05 | 0.06 | 56 | |