Abstract

Objective:

Atopic dermatitis often precedes the development of other atopic diseases, and the atopic march describes this temporal relationship in the natural history of these diseases. Although the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie this relationship are poorly understood, epidemiological and genetic data have suggested that the skin might be an important route of sensitization to allergens

Data Sources:

Review of recent studies on the role of skin barrier defects in systemic allergen sensitization.

Study Selections:

Recent publications on the relationship between skin barrier defects and expression of epithelial

Results:

Animal models have begun to elucidate how skin barrier defects can lead to systemic allergen sensitization. Emerging data now suggest that epithelial cell-derived cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) drive the progression from atopic dermatitis to asthma and food allergy. Skin barrier defects can lead to induction of epithelial cell-derived cytokines, which in turn leads to the initiation and maintenance of allergic inflammation and the atopic march.

Conclusion:

Development of new biologic drug targeting type 2 cytokines provide novel therapeutic interventions for atopic dermatitis.

Keywords: atopic, allergic, TSLP, epithelial, inflammation

1. Introduction

The concept of “atopy” is characterized by exaggerated immune responses to allergic stimuli and high IgE that can lead to clinical disease at a variety of anatomic sites. In general, clinical symptoms of atopy are not present at birth; however, atopic individuals are predisposed to the development of allergies1. For example, the “allergic triad” – atopic dermatitis (eczema), allergic rhinitis, and allergic asthma – frequently presents in a single individual2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Other allergic diseases, such as food allergies, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), and allergic conjunctivitis are also common in atopic patients7, 8, 9, 10.

The natural history of atopic diseases tends to follow a characteristic sequence of events: the first manifestation of atopy is frequently atopic dermatitis, followed later by food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and allergic asthma. The term “atopic march” (or “allergic march”) describes this developmental progression of atopic diseases3, 4, 5, 6. The atopic march often begins early in infancy with the development of atopic dermatitis, which peaks in prevalence within the first two years of life11, 12. Of the children who develop atopic dermatitis, many, if not most, develop the disease within the first six months of life13, 14. There is also a link between atopic dermatitis and the development of food allergies, especially to peanut15, 16, 17. Although asthma has substantial heterogeneity that likely represents distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, individuals with chronic asthma often present before the age of five18, 19.

Children with atopic dermatitis are more likely to develop other atopic diseases than those without atopic dermatitis17, 20, 21. Furthermore, the severity and chronicity of atopic dermatitis also correlate with increased incidence of atopic diseases; whereas around 20% of children with mild atopic dermatitis develop asthma, over 60% with severe atopic dermatitis develop asthma20, 21, 22, 23.

Although the mechanisms that underlie the temporal relationship of diseases in the atopic march are still poorly understood, epidemiological studies have provided a framework for experimental models to examine how atopic dermatitis and skin barrier dysfunction can lead to disease at other anatomic sites. This review will focus on the factors that affect the development of atopic diseases and the atopic march, with a focus on the role of skin barrier dysfunction and the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoetin (TSLP). target for the prevention of the atopic march and treatment of atopic diseases.

The genetics of atopic diseases and the atopic march

While changes in environmental exposures provide some potential as targeted means of decreasing the prevalence of atopic disease, there is a strong influence of genetics on the development of allergies. Based primarily on twin studies of asthma and atopic dermatitis, the heritability of atopic diseases has been estimated to be around 60 to 75%24, 25, 26.

Genetic studies have provided evidence of the importance of epithelial barrier defects in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and other atopic diseases. In particular, mutations in genes encoding three important components of the epithelial barrier of the skin – filaggrin, serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal-type 5 (SPINK5), and corneodesmosin – are associated with atopic dermatitis or atopic dermatitis-like syndromes as well as atopic diseases at other sites.

Filaggrin is expressed as the precursor protein profilaggrin that is subsequently cleaved into filaggrin, which then aggregates and organizes keratin filaments within the skin epithelium. Mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG) can give rise to ichthyosis vulgaris and lead to an increased susceptibility to atopic dermatitis27, 28. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations have been shown to be associated with increased risk of food allergy and eosinophilic esophagitis29, 30, but only in individuals with atopic dermatitis31. Some studies have also reported increased risk of asthma or increased asthma severity with these filaggrin mutations, but it is unclear whether this effect on asthma incidence or severity was dependent on having coincident atopic dermatitis27, 32, 33.

Another example of a monogenic atopic disease is Netherton syndrome, a severe, autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 5 (also referred to as lympho-epithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor [LEKTI])34, 35. At the neutral pH of the deep stratum corneum, LEKTI binds and inhibits the proteases kallikrein related peptidase 5 (KLK5) and KLK7; however, in the acidic conditions of the upper stratum corneum, LEKTI is inhibited, which allows KLK5 and KLK7 to function and promote skin peeling36. In Netherton syndrome, LEKTI deficiency results in KLK5 and KLK7 proteolytic activity in the deeper levels of the skin, resulting in the development of a severe atopic dermatitis-like syndrome and a specific hair shaft defect (trichorrexis invaginata or 'bamboo hair')37. Netherton syndrome patients also have other atopic manifestations including hay fever, food allergies, high serum IgE levels, and hypereosinophilia38, 39. Importantly, these patients display extremely high levels of circulating TSLP, and elevated TSLP expression in the skin, consistent with a role for TSLP in the allergic manifestations of this mutation40.

Autosomal recessive mutations in the corneodesmosin gene (CDSN) result in an inflammatory subtype of generalized skin peeling syndrome (type B), a disorder that overlaps clinically with Netherton’s syndrome41, 42. Mutations associated with generalized skin peeling syndrome type B typically result in a complete loss of corneodesmosin, a secreted glycoprotein component of corneodesmosomes that maintain cell-cell adhesion in the outer layers of the skin. Loss of corneodesmosin in this syndrome results in generalized skin peeling (exfoliation). Although skin peeling syndrome type B is quite rare, atopic manifestations, including food allergies and asthma, do seem to be major features of this syndrome43.

As discussed earlier, mutations in the filaggrin gene are strongly associated with risk for atopic dermatitis but have also been associated with risk for food allergies and asthma. Additional support for a central role of the epithelium in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases is provided by variants of genes encoding epithelial cell-derived cytokines and their receptors that confer increased risk of allergic disease. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) at the loci for thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) or its receptor have been implicated in risk for asthma, atopic dermatitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis44, 45, 46, 47, while SNPs in the loci for IL-33 or its receptor are associated with risk for asthma and atopic dermatitis48, 49, 50. These data are consistent with an important role for epithelial cytokines in the initiation and progression of atopic disease.

Although some genetic susceptibility loci seem specific to certain atopic diseases, the numerous loci associated with both atopic dermatitis and asthma suggest shared underlying pathways. Of note, the genetics of atopic dermatitis has highlighted the importance of the skin barrier. The increased susceptibility to allergic diseases at multiple anatomic sites seen in individuals with fillaggrin, SPINK5, and CDSN mutations also suggests a pathophysiological or mechanistic link between skin barrier defects and increased risk of atopic disease at other sites.

Skin sensitization and the atopic march

Although it is difficult to establish directly the frequency to which sensitization occurs through the skin, the observation that atopic dermatitis tends to precede atopic disease at other sites has led to the proposal that the skin may be an important site in the initiation of the atopic march. In fact, even in the absence of atopic dermatitis, children with skin barrier defects are still at a higher risk for asthma than healthy children, suggesting that the skin may serve as a site for sensitization to allergens even when allergic skin inflammation is absent21.

Several studies have been able to link skin allergen exposure to increased risk of food allergies to those allergens. A case-control study in Japan showed that use of a wheat-containing facial soap was positively correlated with development of food allergy to wheat51. In the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, skin sensitization was also linked to food allergy by demonstrating that application of peanut oil to inflamed skin was positively associated with the development of peanut food allergies52. In this study, maternal consumption of peanuts during pregnancy was not associated with the development of food allergies in the child, and peanut-specific IgE was not detectable in cord blood, suggesting that sensitization to food antigens did not occur in utero. Furthermore, levels of peanut allergens found in breast milk were also not associated with sensitization.

Additional insights into where allergic sensitization takes place have come from the analysis of allergen-specific T cells that become “imprinted” and express specific patterns of homing molecules based on where they are activated and differentiate. In peanut-allergic patients, peanut allergen Ara h 1-specific T cells expressing a memory phenotype also expressed CCR4, a Th2-associated cell trafficking marker53, 54, 55. In another study, memory T cells from peanut-allergic subjects that expressed the skin-homing marker cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA) showed increased proliferation compared to those that expressed α4β7 integrin, a gastrointestinal-homing marker56. Taken together these data suggest that in peanut allergy, allergic sensitization may occur through the skin.

In addition to allergen exposure, sensitization usually requires the presence of other factors that may function as adjuvants: exogenous adjuvants, bacteria colonization of lesional skin, allergens with intrinsic protease activity, or skin barrier damage or defects57. Most, if not all, of these factors elicit the production of cytokines, notably thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and interleukin-33 (IL-33), from the epithelium.

TSLP and the atopic march

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is a member of the 4-helix bundle cytokine family, and a distant paralog of IL-758. As the name suggests, TSLP was first identified in the supernatant of a mouse thymic stromal cell line as an activity capable of supporting immature B cell proliferation and development59, 60, 61. A humanTSLP homolog was subsequently identified in humans using in silico methods62, 63. Similarly, several groups isolated a TSLP-binding protein in both humans and mice (referred to as TSLP receptor (TSLPR) in mice and cytokine receptor-like factor 2 (CRLF2) in humans), which bound TSLP with low affinity64, 65, 66, 67. Sequence analysis found that TSLPR was most closely related to the common gamma chain (γc; 64). It is now known that the functional, high affinity, TSLPR complex is a heterodimer of TSLPR and interleukin 7 receptor alpha (IL-7Rα; Fig. 1)64, 65. Cross-species homology for both the cytokine and its receptor is relatively low (~40% for each), although functionally they appear to be quite similar. Thus, the role of this cytokine axis is conserved between man and mouse despite of a loss of sequence identity.

Figure 1. Schematic of TSLP Receptor Complex.

High affinity signaling TSLP receptor complex consists of the TSLPR and IL-7Rα chains. The tyrosine kinases Jak1 and Jak2 bind IL-7Rα and TSLPR, respectively, and activate the transcriptional regulator Stat5.

A primary cellular target for TSLP are dendritic cells (DCs), which upregulate OX40L, CD80, and CD86 in response to TSLP, and TSLP-treated DCs can drive IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 production from naïve CD4+ T cells upon co-culture68, 69, 70, 71. In addition to its effects on Th2 cell polarization through antigen presenting cells, TSLP can also act directly on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and Treg cells69, 72, 73, 74. TSLP can also promote Th2 cytokine responses through its actions on mast cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), epithelial cells, macrophages, and basophils75, 76, 77, 78. Finally, TSLP was found to play an important role in basophil biology, where in vitro, TSLP could induce basophil maturation from bone marrow precursors in an IL-3 independent manner; furthermore, TSLP-elicited basophils in vivo were phenotypically distinct from IL-3-elicited basophils79.

TSLP is expressed at basal levels at mucosal surfaces (e.g., gut and lung), as well as in the skin62, 80, 81, 82. Its expression can be further enhanced through exposure to viral, bacterial, or parasitic pathogens as well as TLR agonists78, 83, 84. A link between TSLP expression and atopic disease first came from work from Soumelis et al. who showed dramatically elevated expression in the lesional skin of individual with atopic dermatitis85. Following that finding, TSLP expression was found in the airways of asthmatics and the nasal passages of individuals with allergic rhinitits86, 87, 88. TSLP levels in asthmatic airways correlated with Th2-attracting chemokine expression and disease severity86. In eosinophilic esophagitis, a gain-of-function polymorphism in TSLP is associated with disease in pediatric subjects44, 45, and TSLP expression was higher in esophageal biopsy samples from children with active EoE than in biopsy samples from control subjects or subjects with inactive EoE89.

Mouse model systems have been important to understand the role of TSLP in atopic disease. For example, skin-specific overexpression of TSLP under a keratinocyte-specific promoter resulted in a spontaneous atopic dermatitis-like phenotype90. In models of skin sensitization, TSLP is induced following tape stripping or topical application of MC903 (a low calcemic analogue of vitamin D3 that induces TSLP expression)91, 92. Skin sensitization in these models drives local skin inflammation that resembles atopic dermatitis. After sensitization with MC903, antigen challenge in the lung aggravated airway inflammation93, 94, whereas antigen challenge orally drove esophageal inflammation that resembled eosinophilic esophagitis89. We have developed a model of the atopic march in which skin sensitization is induced through intradermal injection of TSLP in the presence of antigen95, 96. Following skin sensitization, intranasal antigen challenge promoted airway inflammation95, and oral antigen challenge drove allergic diarrheal disease96. Dendritic cell-intrinsic TSLP signaling was required to during sensitization, demonstrating the critical role of TSLP in initiating antigen-specific type 2 responses.

As mentioned above, TSLP has been shown to be important for the development of atopic disease in humans. For example, genetic studies in patients with AD have demonstrated that genetic variants of TSLP are associated with both disease severity and persistence97, 98. The TSLP gene variant rs1898671 has been demonstrated to be significantly associated with less persistent AD in white children, which is further enhanced by two filaggrin protein loss-of-function mutations99, 100. TSLP has been shown to be highly expressed in both acute and chronic lesions of AD compared with non-diseased patients and non-lesional skin of patients with AD85 and is correlated with measures of severity and epidermal barrier function101. A small proof-of-concept clinical trial was conducted in patients with moderate-severe AD with tezepelumab, a human anti-TSLP antibody102. Treatment with tezepelumab resulted in a numerical, but not statistically-significant, improvement in eczema severity scores102.

An important symptom of AD is chronic pruritis, which is mediated by primary afferent somatosensory neurons that innervate the skin and are activated by endogenous pruritogens to drive itching103. TSLP may evoke itching indirectly by activating immune cells that secrete inflammatory mediators and cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-13, IL-31) which stimulate sensory neurons104. TSLP has also been shown to act on a subset of TRPA1-positive sensory neurons to trigger pruritis directly105. These data suggest that TSLP may contribute to AD early in the course of the disease by causing itching, scratching and breakdown of the skin barrier.

TSLP has also been found to be involved in asthma in humans. Lung epithelium, like skin, is chronically exposed to a variety of environmental substances and forms a critical barrier to the external environment. Many of these environmental and pathogenic insults to the airway epithelium result in the expression of TSLP (Fig. 2). These include respiratory viruses, allergens, TLR agonists and diesel particulate matter84, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110. Genetics studies have also found a link between polymorphisms in the TSLP gene and asthma susceptibility, with the TSLP SNP rs1837253 associated with childhood-onset asthma in 2 genome wide association studies111, 112.

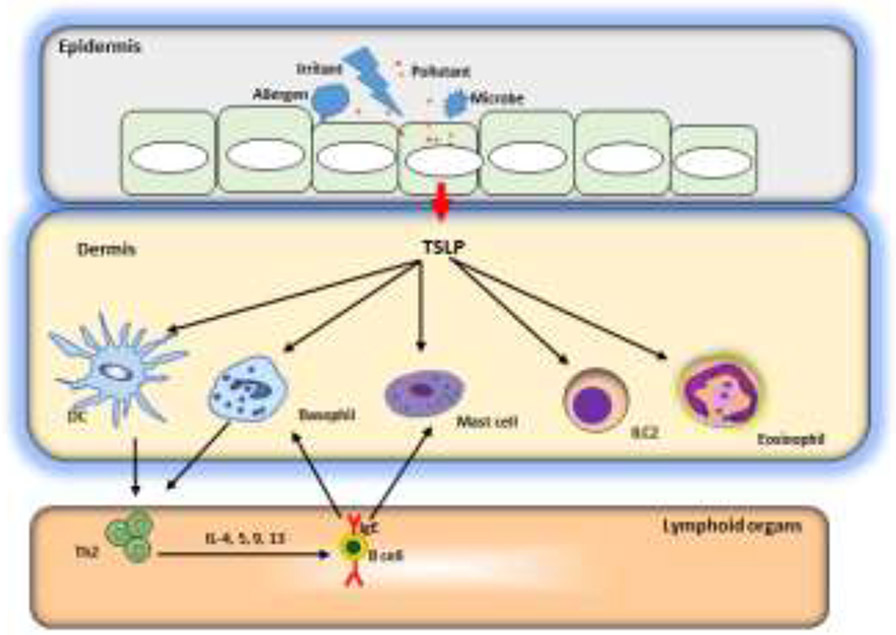

Figure 2. A model of barrier disruption and skin sensitization.

Allergens, infections, and tissue damage can all stimulate release of TSLP (as well as IL-25 and IL-33) from the epithelium. These epithelial cell-deried cytokines license DCs to drive type 2 responses but also act on a variety of cell types, including basophils, eosinophils, mast cells and ILCs to initiate and maintain allergic inflammation.

Several recent studies have examined the therapeutic potential of TSLP inhibition in patients with asthma. The first, a bronchial allergen challenge study in patients with mild allergic asthma, found that after three months of treatment with tezepelumab significant reductions of blood and sputum eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide, indicating that TSLP plays a key upstream role in regulating the release of type-2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-4/IL-13113. Tezepelumab also significantly reduced both early- and late-phase allergen-induced bronchoconstriction, suggesting that both immediate (airway mast cell release) and late events (Th2 cytokine release, eosinophil recruitment and activation) were inhibited. In a subsequent placebo-controlled 52 week trial in moderate-severe uncontrolled asthma, tezepelumab treatment was associated with up to a 71% reduction in the annualized asthma exacerbation rate, with significant reductions observed in patients with type 2 (blood eosinophils > 250 cells/mcl) as well as non-type 2 asthma114. These results in the type 2 subgroup suggest that inhibition of TSLP alone has robust effects on asthma exacerbations, largely caused by viral infections, even in the absence of IL-33 and/or IL-25 antagonism115. The unexpected efficacy of tezepelumab in non-type 2 asthma is not well-understood at present, and data from a current phase 3 study will further elucidate the role TSLP plays as a key player in asthma exacerbations across a range of asthma subtypes.

Conclusion

The development of atopic dermatitis early in life predisposes children to subsequent development of food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma – a phenomenon known as the “atopic march.” Data from epidemiologic studies and animal models suggest that skin barrier defects that allow increased exposure and sensitization to allergens may be important factors in the march from allergic skin inflammation to disease at other sites. It is increasingly apparent that the epithelium at barrier sites is not only a protective lining but is also an important source of cytokines such as TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 that may initiate and drive type 2 inflammation at these sites. Further studies are needed to clarify the specific roles of these cytokines in the atopic march. While some level of redundancy exists, animal models have demonstrated that these cytokines do play distinct roles in allergic inflammation as shown by the effects of TSLP blockade in asthma. The requirements for these epithelial cytokines in both the initiation and maintenance of inflammation make them attractive targets for therapy.

Key Messages.

Skin barrier defects are associated with susceptibility to atopic dermatitis and subsequent food allergies

Skin barrier defects can lead to allergen sensitization

The epithelial cell-derived cytokine TSLP acts as an “alarmin” that is released by the barrier epithelium

TSLP acts to promote type 2 inflammatory responses

TSLP blockade can be an important therapeutic intervention in atopic disease.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges contributions from Drs. Hongwei Han, Florence Roan, and Kazushige Obata-Ninomiya in the preparation of this review.

Financial support:

NIH grants R01AI068731, U19AI125378, and R01AI124220

Footnotes

The author declares no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wahn U & von Mutius E Childhood risk factors for atopy and the importance of early intefention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 107, 567–574 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn EL & Bacharier LB The atopic march: the pattern of allergic disease development in childhood. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 25, 231–246 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jimenez J & Paller AS The Atopic March and its Prevention. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabryszewski SJ et al. Unsupervised modeling and genome-wide association identify novel features of allergic march trajectories. J Allergy Clin Immunol 147, 677–685 e610 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill DA & Spergel JM The atopic march: Critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 120, 131–137 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson E & Hershey GKK Contribution of an impaired epithelial barrier to the atopic march. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 120, 118–119 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burks AW et al. ICON: food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129, 906–920 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sicherer SH & Sampson HA Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125 (Suppl 2), S116–125 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rance F Food allergy in children suffering from atopic eczema. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 19, 279–284 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothenberg ME Molecular, genetic, and cellular bases for treating eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 148, 1143–1157 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bieber T Atopic dermatitis. N Eng J Med 358, 1483–1494 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang K & Stevens SR Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 21, 116–121 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ & Jaron AG The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol 30, 35–39 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eller E, Kjaer HF, Host A, Andersen KE & Bindslev-Jensen C Food allergy and food sensitization in early childhood: results from the DARC cohort. Allergy 64, 1023–1029 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill DJ & Hosking CS Food allergy and atopic dermatitis in infancy: an epidemiologic study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 15, 421–427 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill DJ, Sporik R, Thorburn J & Hosking CS The association of atopic dermatitis in infancy with immunoglobulin E food sensitization. J Pediatr 137, 475–479 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brough HA et al. Atopic dermatitis increases the effect of exposure to peanut antigen in dust on peanut sensitization and likely peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 135, 164–170 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yunginger JW et al. A community-based study of the epidemiology of asthma. Incidence rates, 1964-1983. Am Rev Respir Dis 146, 888–894 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelan PD, Robertson CF & Olinsky A The Melbourne Asthma Study: 1964-1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol 109, 189–194 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsakok T et al. Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137, 1071–1078 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lack G et al. Factors associated with the development of peanut allergy in childhood. N Engl J Med 348, 977–985 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafsson D, Sjoberg O & Foucard T Development of allergies and asthma in infants and young children with atopic dermatitis--a prospective follow-up to 7 years of age. Allergy 55, 240–245 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Kobyletzki LB et al. Eczema in early childhood is strongly associated with the development of asthma and rhinitis in a prospective cohort. BMC Dermatol 12, 11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy DL, Martin NG, Battistutta D, Hopper JL & Mathews JD Genetics of asthma and hay fever in Australian twins. Am Rev Respir Dis 142, 1351–1358 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ullemar V et al. Heritability and confirmation of genetic association studies for childhood asthma in twins. Allergy 71, 230–238 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elmose C & Thomsen SF Twin Studies of Atopic Dermatitis: Interpretations and Applications in the Filaggrin Era. J Allergy (Cairo) 2015, 902359 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer CN et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet 38, 441–446 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandilands A et al. Prevalent and rare mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris and predispose individuals to atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 126, 1770–1775 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkataraman D et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with food allergy in childhood and adolescence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 134, 876–882 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown SJ et al. Loss-of-function variants in the filaggrin gene are a significant risk factor for peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127, 661–667 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thyssen JP et al. Filaggrin gene mutations are not associated with food and aeroallergen sensitization without concomitant atopic dermatitis in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 135, 1375–1378 e1371 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu K et al. Filaggrin null mutations are associated with increased asthma exacerbations in children and young adults. Allergy 63, 1211–1217 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson J et al. The burden of disease associated with filaggrin mutations: a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 121, 872–877 e879 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chavanas S et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nature Genet 25, 141–142 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Judge MR, Morgan G & Harper JI A clinical and immunological study of Netherton's syndrome. Brit J Dermatol 131, 615–621 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubo A, Nagao K & Amagai M Epidermal barrier dysfunction and cutaneous sensitization in atopic diseases. J Clin Invest 122, 440–447 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Netherton EW A unique case of trichorrhexis nodosa; bamboo hairs. AMA Arch Derm 78, 483–487 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walley AJ et al. Gene polymorphism in Netherton and common atopic disease. Nat Genet 29, 175–178 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusunoki T et al. SPINK5 polymorphism is associated with disease severity and food allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115, 636–638 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briot A et al. Kallikrein 5 induces atopic dermatitis-like lesions through PAR2-mediated thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in Netherton syndrome. The Journal of experimental medicine 206, 1135–1147 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teye K et al. A founder deletion of corneodesmosin gene is prevalent in Japanese patients with peeling skin disease: Identification of 2 new cases. J Dermatol Sci 82, 134–137 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Telem DF, Israeli S, Sarig O & Sprecher E Inflammatory peeling skin syndrome caused a novel mutation in CDSN. Arch Dermatol Res 304, 251–255 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oji V et al. Loss of corneodesmosin leads to severe skin barrier defect, pruritus, and atopy: unraveling the peeling skin disease. Am J Hum Genet 87, 274–281 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothenberg ME et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat. Genet 42, 289–291 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherrill JD et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 126, 160–165 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harada M et al. TSLP Promoter Polymorphisms are Associated with Susceptibility to Bronchial Asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol Epub ahead of print (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyake Y, Hitsumoto S, Tanaka K & Arakawa M Association Between TSLP Polymorphisms and Eczema in Japanese Women: the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. Inflammation 38, 1663–1668 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moffatt MF et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association of asthma. New Engl J Med 363, 1211–1221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimizu M et al. Functional SNPs in the distal promoter of the ST2 gene are associated with atopic dermatitis. Hum. Mol. Genet 14, 2919–2927 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Savenije OE et al. Association of IL33-IL-1 receptor-like 1 (IL1RL1) pathway polymorphisms with wheezing phenotypes and asthma in childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 134, 170–177 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukutomi Y, Taniguchi M, Nakamura H & Akiyama K Epidemiological link between wheat allergy and exposure to hydrolyzed wheat protein in facial soap. Allergy 69, 1405–1411 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lack G, Fox D, Northstone K & Golding J Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team. Factors associated with the development of peanut allergy in childhood. N Eng J Med 348, 977–985 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wambre E et al. A phenotypically and functionally distinct human TH2 cell subpopulation is associated with allergic disorders. Sci Transl Med 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeLong JH et al. Ara h 1-reactive T cells in individuals with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127, 1211–1218 e1213 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tordesillas L et al. Skin exposure promotes a Th2-dependent sensitization to peanut allergens. J Clin Invest 124, 4965–4975 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan SM et al. Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen and alpha4beta7 T-lymphocyte responses are associated with peanut allergy and tolerance in children. Allergy 67, 336–342 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunkin D, Berin MC & Mayer L Allergic sensitization can be induced via multiple physiologic routes in an adjuvant-dependent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128, 1251–1258 e1252 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sims JE et al. Molecular cloning and biological characterization of a novel murine lymphoid growth factor. J Exp Med 192, 671–680 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levin SD et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: a cytokine that promotes the development of IgM+ B cells in vitro and signals via a novel mechanism. Journal of Immunology 162, 677–683 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friend SL et al. A thymic stromal cell line supports in vitro development of surface IgM+ B cells and produces a novel growth factor affecting B and T lineage cells. Exp. Hematol 22, 321–328 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ray RJ, Furlonger C, Williams DE & Paige CJ Characterization of thymic stromal-derived lymphopoietin (TSLP) in murine B cell development in vitro. Eur J Immunol 26, 10–16 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reche PA et al. Human thymic stromal lymphopoietin preferentially stimulates myeloid cells. J Immunol 167, 336–343 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quentmeier H et al. Cloning of human thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and signaling mechanisms leading to proliferation. Leukemia 15, 1286–1292 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park LS et al. Cloning of the murine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) receptor: Formation of a functional heteromeric complex requires interleukin 7 receptor. J. Exp. Med 192, 659–670 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pandey A et al. Cloning of a receptor subunit required for signaling by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Nat. Immunol 1, 59–64 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujio K et al. Molecular cloning of a novel type 1 cytokine receptor similar to the common gamma chain. Blood 95, 2210 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tonozuka Y et al. Molecular cloning of a human novel type I cytokine receptor related to delta1/TSLPR. Cytogenet Cell Genet 93, 23–25 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ito T et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J. Exp. Med 202, 1213–1223 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kitajima M, Lee HC, Nakayama T & Ziegler SF TSLP enhances the function of helper type 2 cells. Eur. J. Immunol 41, 1862–1871 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kitajima M & Ziegler SF Cutting edge: identification of the thymic stromal lymphopoietin-responsive dendritic cell subset critical for initiation of type 2 contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol 191, 4903–4907 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu YJ et al. TSLP: an epithelial cell cytokine that regulates T cell differentiation by conditioning dendritic cell maturation. Annu Rev Immunol 25, 193–219 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rochman Y & Leonard WJ The role of thymic stromal lymphpoietin in CD8+ T cell homeostasis. J Immunol 181, 7699–7705 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rochman I, Watanabe N, Arima K, Liu YJ & Leonard WJ Cutting edge: direct action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin on activated human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 178, 6720–6724 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omori M & Ziegler S Induction of IL-4 expression in CD4(+) T cells by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Immunol 178, 1396–1404 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kabata H et al. Targeted deletion of the TSLP receptor reveals cellular mechanisms that promote type 2 airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 13, 626–636 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allakhverdi Z, Comeau MR, Jessup HK & Delespesse G Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a mediator of crosstalk between bronchial smooth muscles and mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 123, 958–960 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim BS et al. TSLP elicits IL-33-independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci Transl Med 5, 170ra (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miazgowicz MM, Elliott MS, Debley JS & Ziegler SF Respiratory syncytial virus induces functional thymic stromal lymphopoietin receptor in airway epithelial cells. J Inflamm Res 6, 53–61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Siracusa MC et al. TSLP promotes interleukin-3-independent basophil haematopoiesis and type 2 inflammation. Nature 477, 229–233 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watanabe N et al. Human thymic stromal lymphopoietin promotes dendritic cell-mediated CD4+ T cell homeostatic expansion. Nat Immunol 5, 426–434 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rimoldi M et al. Intestinal immune homeostasis is regulated by the corsstalk between epithelial cells and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 6, 507–514 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang K et al. Constitutive and inducible thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Physiol Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 293, L375–L382 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kato A, Favoreto S Jr., Avila PC & Schleimer RP TLR3- and Th2 cytokine-dependent production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 179, 1080–1087 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee H-C & Ziegler SF Inducible expression of the proallergic cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin in airway epithelial cells is controlled by NFkappaB. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 914–919 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Soumelis V et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat. Immunol 3, 673–680 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ying S et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in asthmatic airways and correlates with expression of Th2-attracting chemokines and disease severity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 174, 8183–8190 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mou Z et al. Overexpression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in allergic rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol 129, 297–301 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bunyavanich S et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is associated with allergic rhinitis in children with asthma. Clin Mol Allergy 9, 1 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Noti M et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin–elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nature Medicine, 1–11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yoo J et al. Spontaneous atopic dermatitis in mice expressing an inducible thymic stromal lymphopoietin transgene specifically in the skin. J. Exp. Med 202, 541–549 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li M et al. Topical vitamin D3 and low-calcemic analogs induce thymic stromal lymphopoietin in mouse keratinocytes and trigger an atopic dermatitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 11736–11741 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He R et al. TSLP acts on infiltrating effector T cells to drive allergic skin inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 11875–11880 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Z et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin overproduced by keratinocytes in mouse skin aggravates experimental asthma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 1536–1541 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leyva-Castillo JM, Hener P, Jiang H & Li M TSLP Produced by Keratinocytes Promotes Allergen Sensitization through Skin and Thereby Triggers Atopic March in Mice. J Invest Dermatol 133, 154–163 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han H et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)-mediated dermal inflammation aggravates experimental asthma. Mucosal. Immunol 5, 342–351 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Han H, Data L, Comeau MR & Ziegler SF Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated epicutaneous inflammation promotes acute diarrhea and anaphylaxis. J. Clin. Invest 124, 5442–5452 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bin L & Leung DY Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 12, 52 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liang Y, Chang C & Lu Q The Genetics and Epigenetics of Atopic Dermatitis-Filaggrin and Other Polymorphisms. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 51, 315–328 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chang J, Mitra N, Hoffstad O & Margolis DJ Association of Filaggrin Loss of Function and Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Variation With Treatment Use in Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 153, 275–281 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Margolis DJ et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin variation, filaggrin loss of function, and the persistence of atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 150, 254–259 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sano Y et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in the horny layer of patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Immunol 171, 330–337 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Simpson EL et al. Tezepelumab, an anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized phase 2a clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 80, 1013–1021 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McCoy ES, Taylor-Blake B & Zylka MJ CGRPalpha-expressing sensory neurons respond to stimuli that evoke sensations of pain and itch. PLoS One 7, e36355 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mack MR & Kim BS The Itch-Scratch Cycle: A Neuroimmune Perspective. Trends Immunol 39, 980–991 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wilson SR et al. The epithelial cell-derived atopic dermatitis cytokine TSLP activates neurons to induce itch. Cell 155, 285–295 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee HC et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is induced by respiratory syncytial virus-infected airway epithelial cells and promotes a type 2 response to infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 130, 1187–1196 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Headley MB et al. TSLP conditions the lung immune environment for the generation of pathogenic innate and antigen-specific adaptive immune responses. J. Immunol 182, 1641–1647 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Iijima K et al. IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin mediate immune pathology in response to chronic airborne allergen exposure. J. Immunol 193, 1549–1559 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bleck B et al. MicroRNA-375 regulation of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by diesel exhaust particles and ambient particulate matter in human bronchial epithelial cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 190, 3757–3763 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bleck B, Tse DB, Gordon T, Ahsan MR & Reibman J Diesel exhaust particle-treated human bronchial epithelial cells upregulate Jagged-1 and OX40 ligand in myeloid dendritic cells via thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Immunol 185, 6636–6645 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Torgerson DG et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat. Genet 43, 887–892 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hirota T et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for adult asthma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet 43, 893–896 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gauvreau GM et al. Effects of an anti-TSLP antibody on allergen-induced asthmatic responses. N Engl J Med 370, 2102–2110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Corren J et al. Tezepelumab in Adults with Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med 377, 936–946 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Uller L & Persson C Viral induced overproduction of epithelial TSLP: Role in exacerbations of asthma and COPD? J Allergy Clin Immunol 142, 712 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]