Abstract

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is an important bioactive lipid molecule in cell membrane metabolism and binds to G protein-coupled S1P receptors (S1PRs) to regulate embryonic development, physiological homeostasis, and pathogenic processes in various organs. S1PRs are lipid-sensing receptors and are therapeutic targets for drug development, including potential treatment of COVID-19. Herein, we present five cryo-electron microscopy structures of S1PRs bound to diverse drug agonists and the heterotrimeric Gi protein. Our structural and functional assays demonstrate the different binding modes of chemically distinct agonists of S1PRs, reveal the mechanical switch that activates these receptors, and provide a framework for understanding ligand selectivity and G protein coupling.

Subject terms: Cryoelectron microscopy, Lipid signalling

Introduction

Lipid signaling has long been recognized as a critical regulator of cellular processes. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a metabolic product of cell membrane sphingolipids, is a ubiquitous lysophospholipid signaling molecule that modulates diverse biological functions, including lymphocyte trafficking, vascular development, endothelial integrity, and heart rate.1–3 The different physiological functions exerted by S1P are mediated through five S1P receptor (S1PR) subtypes, S1PR1–S1PR5.4,5 S1PRs are distributed over a wide range of tissues with distinct downstream G protein preferences. S1PR1, S1PR2, and S1PR3 are expressed primarily in the immune, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems; S1PR4 is expressed mainly in the lymphoid system, hematopoietic tissue, and lung; and S1PR5 is expressed predominantly in the brain and spleen.6,7 S1PR1 exclusively couples with Gi/o proteins; S1PR2 and S1PR3 couple with Gi/o, Gq and G12/13; and S1PR4 and S1PR5 couple with Gi/o and G12/13.6 The differential but overlapping expression patterns and intracellular signaling pathways of each receptor probably form the molecular basis for the diverse functions of S1P that regulate different physiological functions.8

The S1P-S1PR signaling system is an effective therapeutic target for multiple diseases, including autoimmune disorders,9 inflammation,1 cancer,10 and even COVID-19.11 Accordingly, drug discovery efforts have focused on the interactions of receptors with chemically distinct ligands with subfamily cross-reactivity and individual specificity.12 Fingolimod (FTY720) was first developed to undergo in vivo phosphorylation and then bind to the S1PR subfamily for treating relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).13 Given the adverse consequences of “off-target” effects, subtype-specific ligands for receptors have been developed as an alternative approach for improving drug selectivity.14 For example, the drug siponimod was globally approved in March 2019 for treating adults with relapsing MS by targeting S1PR1 and S1PR5.15 In 2020, the US FDA approved ozanimod for MS treatment because this drug displays 25-fold higher selectivity toward S1PR1 compared with that of S1PR5.16,17 In particular, during the current COVID-19 pandemic situation, agonist drugs targeting S1PRs have been repurposed for COVID-19 treatment via an immune-modulating therapy strategy.18 Compared with fingolimod, the drug ozanimod demonstrates an advantage in reducing the related symptoms of COVID-19 in patients and is currently in clinical trials.11

Despite the urgent need, the development of specific agonists that selectively target S1PRs is greatly hindered by the high sequence homology among S1PRs and the lack of structural information on active S1PRs bound to agonists.19 Only the crystal structure of inactive S1PR1 bound with an antagonist had been determined. Here, we report the cryo-electron microscopy (EM) structures of agonists-bound S1PR1 and S1PR5 with Gi coupling, providing a structural framework for the ligand recognition, activation and Gi protein coupling mechanisms of both receptors.

Results

Preparation of S1PR1/S1PR5–Gi complexes and overall structures

Preparation of a stable human S1PR–heterotrimeric Gi complex bound by agonists was achieved by fusing a T4L protein at the N-terminus of S1PR1 and removing the disordered region at the C-terminus of both S1PR1 and S1PR5. Similar to wild-type S1PRs, the modified versions exhibited Gi signaling activity (Supplementary information, Fig. S1a, b). The modified S1PRs–heterotrimeric Gi complexes were co-expressed in insect cells and the complexes were assembled on the membrane by incubation with agonists and apyrase. The antibody fragment scFv16 was added to the nucleic acid-free S1PR–Gi complex to further stabilize the S1PR–Gi complexes.20 These strategies yielded stable complexes, and size-exclusion chromatography profiles and the results of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showed that pure and monodisperse samples suitable for single-particle cryo-EM analysis were obtained (Supplementary information, Fig. S1c–f).

We then acquired cryo-EM data and reconstructed the structures of five S1PR–Gi complexes, including four structures of S1PR1 bound to siponimod, cenerimod, ozanimod, and a highly selective agonist SEW2871, and one structure of S1PR5 bound to siponimod (Supplementary information, Figs. S1g, S2, S3). These structures were determined by single-particle cryo-EM at resolutions ranging from 2.98 to 3.42 Å (Fig. 1a–d; Supplementary information, Table S1). The high-quality cryo-EM maps enabled construction of the transmembrane domains of the two receptors, the Gi heterotrimer and scFv16, with the majority of side chains in the complexes explicitly identified (Supplementary information, Fig. S1h). Moreover, well-defined densities for agonists were unambiguously observed in the orthosteric sites of the receptors (Supplementary information, Fig. S4a). In addition, the N-linked glycosylation modification was identified at residue N30 of S1PR1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S4b). Our functional assay showed that mutation N30A in S1PR1 reduced G protein signaling, whereas mutations N30D and N30Q did not affect the potency of receptor activation notably (Supplementary information, Fig. S4c). In agreement with the previous report,21 our results showed that the cell-surface expression level of the N30A mutant was lower compared with that of wild-type S1PR1, whereas the N30D and N30Q mutants retained similar expression levels to that of wild-type S1PR1. The corresponding residue with potential glycosylation in S1PR5 is N20. Mutation of this residue in S1PR5 reduced its cell-surface expression (Supplementary information, Fig. S4d) and almost abolished the inhibitory effect of siponimod on forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation (Supplementary information, Fig. S4c). Thus, glycosylation of S1PR1 and S1PR5 regulates the receptor activation potency possibly because this modification plays a role in maintaining surface expression of the receptors, which suggests that glycosylation may facilitate receptor transport to the cell surface.

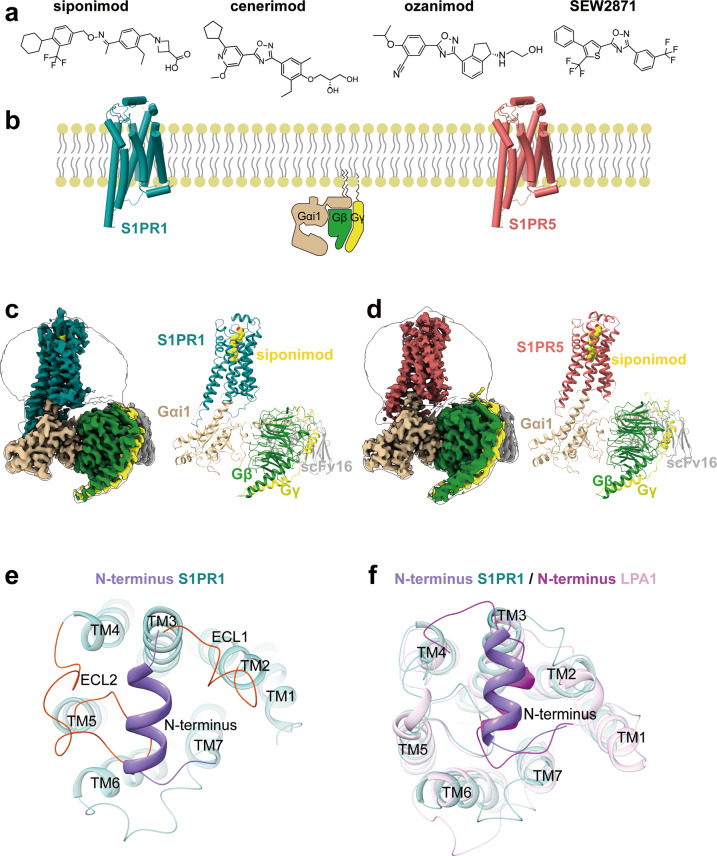

Fig. 1. Overall cryo-EM structures of the S1PRs–Gi heterotrimer complexes.

a Two-dimensional representation of chemical structures of siponimod, cenerimod, ozanimod and SEW2871. b Signaling paths of S1PR1 and S1PR5. Both receptors predominantly signal through Gi-type G protein. c The cryo-EM map (left) of S1PR1–Gi–scFv16 in complex with siponimod and the cartoon representation (right) of the complex structure are shown. Teal, S1PR1; yellow, siponimod; tan, Gαi; forest green, Gβ; yellow, Gγ; gray, scFv16. The cryo-EM density map colored according to different subunits is shown at 0.3 contour level. d The cryo-EM map (left) of S1PR5–Gi–scFv16 in complex with siponimod and the cartoon representation (right) of the complex structure are shown. Indian red, S1PR5; yellow, siponimod; tan, Gαi; forest green, Gβ; yellow, Gγ; gray, scFv16. The cryo-EM density map colored according to different subunits is shown at 0.011 contour level. e Extracellular view of S1PR1. The N-terminus of S1PR1 fold helical cap over TM domain. Teal, S1PR1; orange red, extracellular loops (ECL); medium purple, N-terminus. f Structural superposition of S1PR1 (active) with LPAR1 (inactive; PDB code: 4Z35) reveals a similar N-terminal helical conformation. Teal, S1PR1; medium purple, N-terminus of S1PR1; plum, LPAR1; magenta, N-terminus of LPA1.

Consistent with another lipid receptor, LPA1,22 the S1PR subfamily has a highly conserved N-terminal region that folds a helical cap over the extracellular vestibules and packs tightly against extracellular loop 1 (ECL1) and ECL2. This structural feature seems to restrict extracellular access to the ligand-binding pocket, which results in an occluded orthosteric site in S1PR1 (Fig. 1e, f). In general, the overall structure of the S1PR–Gi complex showed a similar assembly mode to that of other activated GPCR–Gi complex structures23 (Supplementary information, Fig. S4e, f). The active states in the two receptors had low Cα atom root mean square deviation values of 0.49 Å for the whole complex and 1.09 Å and 0.47 Å for the receptor and Gi protein, respectively.

Recognition of the drug siponimod in S1PR1 and S1PR5

Siponimod is an orally available immunomodulatory drug used to treat relapsing MS,15 as a result of its action on S1PR1 and S1PR5 with similar binding affinity.24 The S1PR structures determined herein in this paper provide insight into the basis of siponimod recognition in both receptors. As shown in Supplementary information Fig. S4g, siponimod exhibits an identical linear conformation in both the S1PR1 and S1PR5 structures and binds to a deep central cavity of both S1PRs, which is formed by residues from the extracellular regions (N-terminus, ECL1 and ECL2) and TM bundles (TM3, TM5, TM6, and TM7) (Fig. 2a). The orthosteric site in S1PR1 is composed of two classic essential modules: a polar-network region at the top and a hydrophobic region deep in the cavity (Fig. 2b, c). This particular ligand-binding pocket pattern was also found in structures of LPA receptors,22 reflecting similar endogenous ligands with polar headgroups and phenyl acyl-tail hydrophobic frameworks.

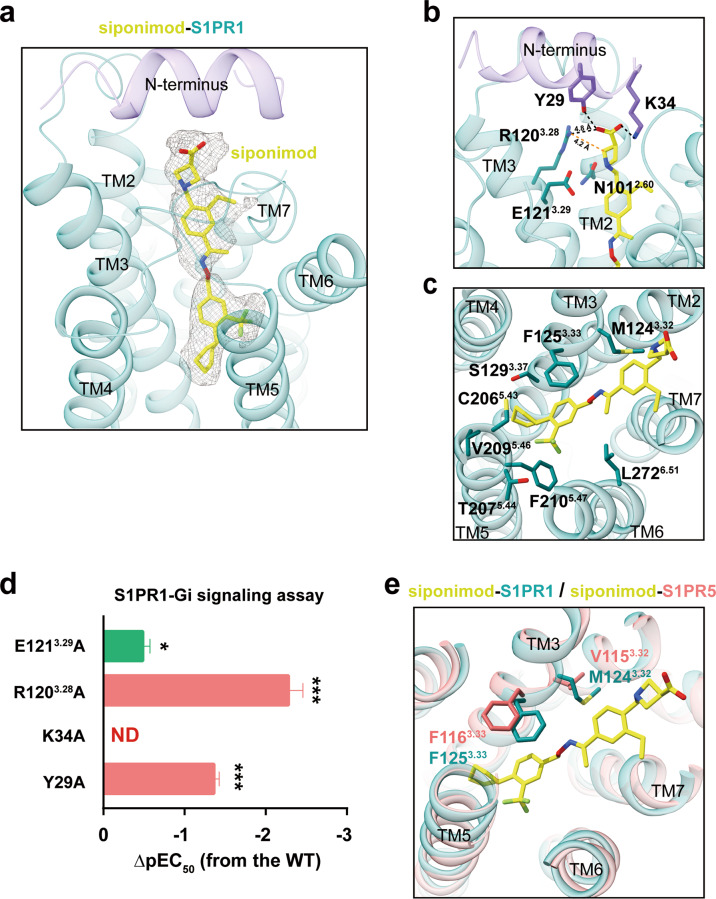

Fig. 2. Binding mode of the drug siponimod in S1PRs.

a Siponimod exhibits linear conformation in the orthosteric site of S1PR1 with clear density (0.206 contour level). Siponimod is shown as yellow stick and the interaction residues within 4 Å are also shown as sticks. b The polar-network in siponimod recognition of S1PR1. The polar headgroup of the ligand forms potential polar interactions with the side-chains of Y29N-ter, K34N-ter, N1012.60, R1203.28 and E1213.29 in S1PR1. The polar interactions are highlighted as black dashed lines and the distances between R1203.28 and siponimod are labeled. c The hydrophobic interaction module of siponimod with S1PR1. The siponimod inserts into a deeply hydrophobic cavity that is mainly comprised of TM3, TM5 and TM6 in S1PR1. d Effects of key residues Y29N-ter, K34N-ter, R1203.28 and E1213.29 mutations of S1PR1 on siponimod-induced Gi signaling activation potency. Bars represent the difference in calculated potency (pEC50) of agonist siponimod for S1PR1 mutants relative to WT. Data are colored according to the extent of effect. ND, not detected; *P < 0.1, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett’s test, compared with the response of WT). Data represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. e Comparison of siponimod recognition between S1PR1 and S1PR5.

In general, the zwitterionic head group of siponimod, which mimics the phosphate group of endogenous S1P, is exposed to the extracellular environment and forms polar interactions with Y29N-ter and K34N-ter from the N-terminal capping helix of S1PR1. Additionally, the head group of siponimod forms van der Waals interactions or a potentially weak salt bridge with the side chain of R1203.28 (Fig. 2b). In contrast to the inactive structure of S1PR1 bound to antagonist ML05619 (Supplementary information, Fig. S4h), residue E1213.29 does not interact with siponimod. Our functional assays indicated that alanine substitution of Y29N-ter, K34N-ter, or R1203.28 decreased the efficacy of siponimod significantly, probably due to a loss of the interactions described above, whereas the E1213.29A mutation reduced the Gi signaling by 3-fold compared with that of the wild-type S1PR1 (Fig. 2d; Supplementary information, Table S2). Additionally, water-mediated interactions play an important role in activation of GPCRs as indicated by a molecular dynamics simulation study25 and the high-resolution structures of GPCRs.26 Therefore, water-mediated interactions may be involved in the contacts between siponimod and the receptor.

The hydrophobic portion of siponimod extends into the aromatic pocket of S1PR1, with the cyclohexyl moiety projecting into the cleft between TM3 and TM5, thus defining an absolute long channel shape of the orthosteric site in both S1PR1 and S1PR5 (Fig. 2c). The notable differences in the ligand-binding cavities of the two receptors are: (i) the residue M1243.32 in S1PR1 is replaced by the corresponding residue V1153.32 in S1PR5, both of which interact directly with the 2-ethylphenyl moiety of siponimod via their side-chains; and (ii) a rotamer displacement of F3.33 occurs in both receptors, creating subtle differences in the cavity (Fig. 2e). Overall, these observations provide a structural basis for siponimod recognition by both receptors.

Comparison of diverse structural agonist binding modes of S1PR1

Selectivity design is an important component in the drug development process for the S1PR subfamily.12,27 Fingolimod, also known as FTY720, was the first prodrug of S1PR1 and S1PR3–5 and inspired the development of a series of drugs with diverse structures, including variable or alternative polar head groups represented by the near clinical and clinical-stage agonists, such as the polar-zwitterionic group in siponimod, the polar-neutral headgroup of cenerimod, and the polar-basic headgroup of ozanimod. As shown in the structural comparison (Figs. 2b, 3a, b), the polar headgroups from the three agonists form direct contacts with K34N-ter from the N-terminal capping helix (Supplementary information, Fig. S5a). Furthermore, the ligand with the minimum required element (nonpolar headgroup) was observed to display robust activity. The ligand SEW2871 is a representative example of an analog from this compound class, displaying > 10,000-fold selectivity for S1PR1 over S1PR5.28 Unfortunately, SEW2871 was found to cause severe cardiac side effects in pre-clinical trials.29 Incorporation of the polarizable trifluoromethyl group particularly improved the selectivity and potency by forming direct interactions with N1012.60 and E1213.29 in S1PR130 (Fig. 3c). We performed mutagenesis studies and receptor signaling assays to validate the contributions of charged residues to binding chemically distinct agonists. Our results indicated that K34N-terA and Y29N-terA mutants markedly weakened the binding to ligands bearing polar headgroups (Fig. 2d), and that the E1213.29A mutation remarkably decreased SEW2871’s potency in activating the receptor (Supplementary information, Fig. S5b).

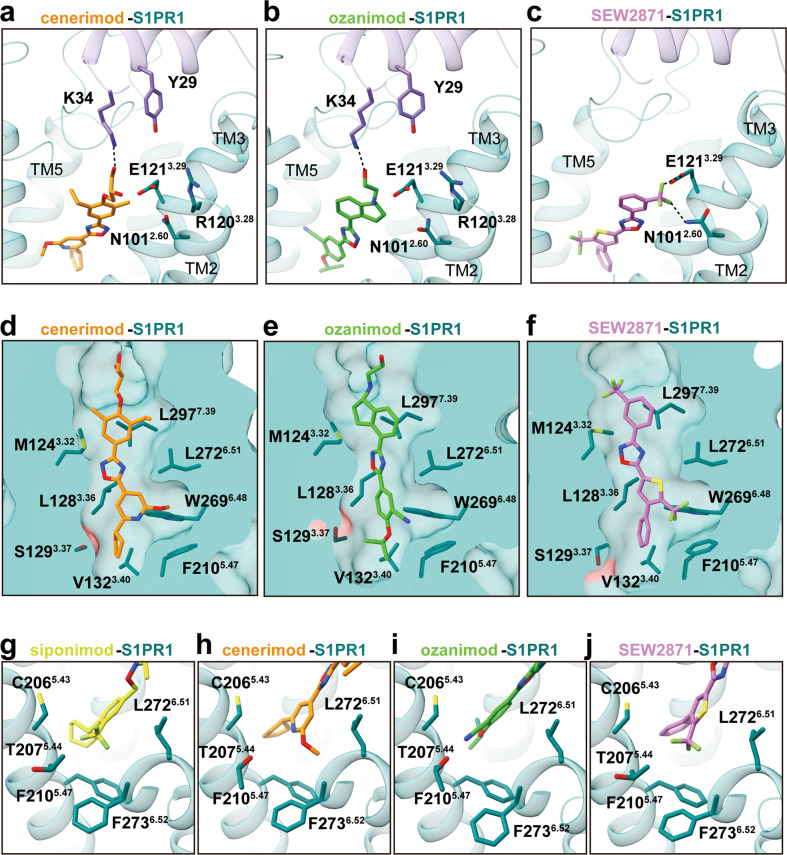

Fig. 3. Comparison of recognition modes of chemically distinct agonists by S1PR1.

a–c Structural basis underlying the recognition of cenerimod (dark orange) with polar-neutral headgroup (a), ozanimod (lime green) with polar-basic headgroup (b), and selective SEW2871 (orchid) without classic polar headgroup (c) by S1PR1. d–f Cut away view of different ligand-binding cavities for cenerimod-bound (d), ozanimod-bound (e), and SEW2871-bound S1PR1 (f). g–j The sub-pocket in the orthosteric site of S1PR, which is composed of the residues C2065.43, T2075.44, F2105.47, L2726.51 and F2736.52 from TM5 and TM6, respectively, accommodates different moieties from four chemically distinct agonists, including trifluoromethyl moiety, methoxy moiety or cyano-moiety.

In accordance with structural analyses and functional assays, the polar module in the ligand-binding pocket was possibly engaged with ligand binding and receptor activation; however, a previous study showed that the volume occupied by the hydrophobic portion of the ligand played a key role in receptor activation.31 By aligning four agonists in the S1PR1 structures (Supplementary information, Fig. S5c), we found that the hydrophobic portion of each ligand was located in a nearly identical narrow hydrophobic pocket of S1PR1 (Figs. 2c, 3d–f). Notably, a sub-pocket of the orthosteric site was identified to accommodate the subgroups of agonists, such as the trifluoromethyl moiety of siponimod and SEW2871, the methoxy moiety of cenerimod and the cyano moiety of ozanimod. These moieties form hydrophobic interactions with the surrounding residues C2065.43, T2075.44, F2105.47, L2726.51, and F2736.52 from TM5 and TM6 (Fig. 3g–j). When we generated alanine replacements in this sub-pocket, the results of the signaling assay indicated that the activation potency of all receptor variants decreased when sensing different agonists (Supplementary information, Fig. S5d).

The solved structures provide a basis for the recognition of chemically distinct agonists of S1PR1, which may afford opportunities for the development of new drugs with improved specificity and efficacy for disease treatment.32 Nonpolar agonists were defined as a new category lacking polar headgroups; however, they still exhibited high selectivity and modest potency against S1PR1, which suggests that the hydrophobic ligand pocket in the S1PR subfamily plays a critical role in lipid signaling activation.

Activation mechanism of S1PRs

The determined structures of Gi-coupled S1PR1 bound to different agonists together with the previously reported antagonist-bound S1PR1 structure enabled an examination of the mechanism of agonist-mediated activation. Further careful structural comparison of antagonist ML056-bound S1PR119 showed subtle rearrangement of the extracellular ends of helix bundles and the N-terminal helical cap. In contrast, notable conformational rearrangements were observed at the cytoplasmic end of the receptor with TM6 moving outwards by ~9 Å, and TM7 moving inward by ~4 Å (Fig. 4a). Such structural changes allowed the C-terminal helix of Gαi to couple to the receptor core cavity and initiate signaling.

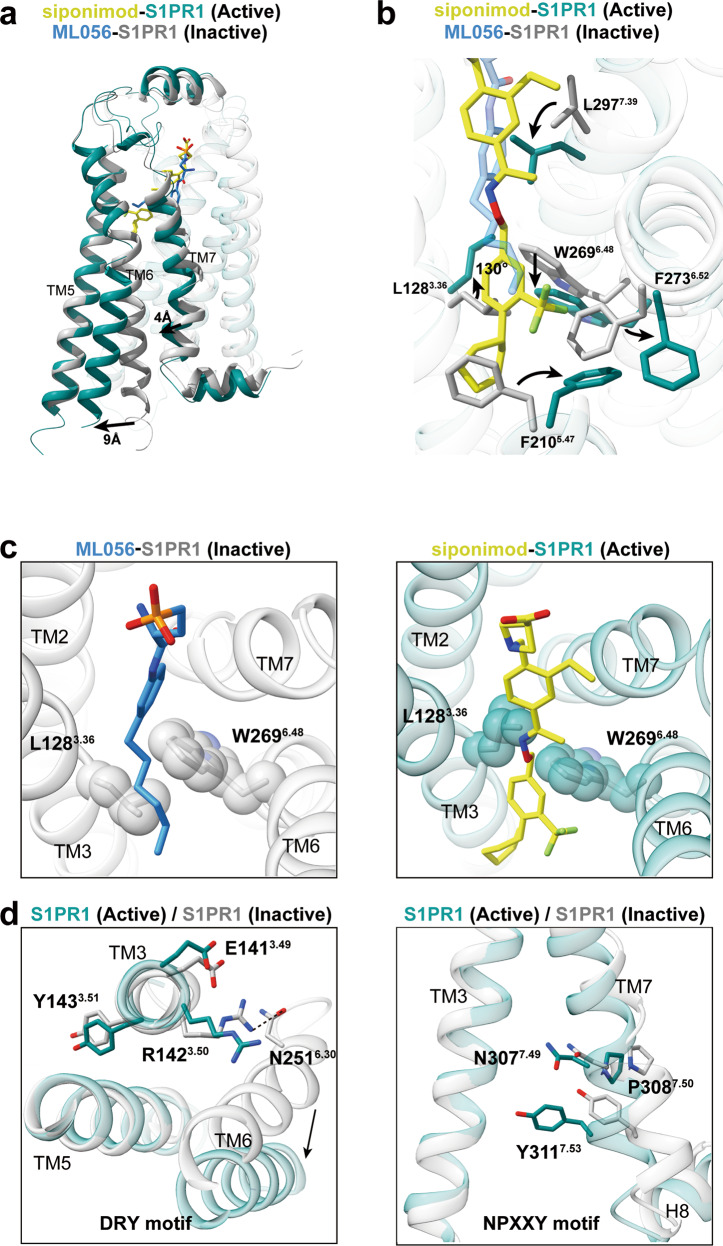

Fig. 4. S1PR1 activation mechanism.

a Superposition of S1PR1 structures in inactive (gray; PDB code: 3V2Y) and Gi-stabilized active states (teal). Notable conformational changes occur at intracellular ends of TM6 and TM7 upon receptor activation. b Detailed comparison of the orthosteric binging pocket of antagonist ML056 (dodger blue)-bound inactive S1PR1 with that of agonist siponimod-bound active S1PR1. In particular, side-chains of the residues L1283.36, F2105.47, W2696.48, F2736.52 and L2977.39 are observed to exhibit a notable displacement upon activation. c The toggle molecular switch L1283.36 and W2696.48 in S1PR1. The left panel displays relative orientation of L1283.36–W2696.4 in inactive S1PR1, whereas the right panel represents movement of L1283.36–W2696.4 when sensing agonist. d The key D/E–R3.50–Y and N–P7.50–xx–Y7.53 motifs important for activation of S1PR1 are observed to display conformational rearrangement in activated receptor.

Analysis of the structures of chemically distinct agonists bound to S1PR1 and the results of previous studies suggest that the hydrophobic cavity is critical for receptor activation. Notably, some critical large residues in the ligand-binding pocket exhibit marked rotamer changes when an agonist binds to the receptor. The aromatic group of the antagonist ML056 inserts into a side pocket of the ligand-binding cavity that is formed by M1243.32 and L2977.39 from TM3 and TM7, respectively, and the side chain of L2977.39 undergoes a major conformational change during receptor activation, which results in a steric clash with ligand ML056 (Fig. 4b). More importantly, the side chain displacements of L1283.36, F2105.47, and F2736.52 in TM3, TM5, and TM6, respectively, afford a large hydrophobic volume that can accommodate agonists longer than ML056 (Fig. 4b).

To understand the key role of these residues (L3.36, F5.47, and F6.52) in activation transition of S1PR1, we further compared the S1PR1 structures with the endogenous S1P-bound S1PR3–Gi complex structure determined in our companion paper.33 Moreover, a comparison between the side chain of the corresponding residue F6.52 in active S1PR3 revealed that this residue resembles the same rotamer conformation as that in inactive S1PR1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S6a). The side chains of L3.36 and F5.47 in active S1PR1 exhibited notable displacements compared with those in the inactive state of the receptor (Fig. 4b). Therefore, residues L3.36 and F5.47 in S1PRs appear to participate in the initial activation of the receptor. In agreement with our observations, mutation of these residues impaired the signaling activation of the receptor (Supplementary information, Fig. S6b).

As is seen in inactive S1PR1 (Fig. 4c), residue L1283.36, which is stabilized by direct contact with W2696.48, rotates 130° away from TM5 and forms a direct interaction with the hydrophobic portion of agonists upon activation (Fig. 4b). This change is accompanied by a synergistic downward movement of W2696.48 (Fig. 4c). Thus, the hydrophobic interaction between these two residues is disrupted upon activation, which loosens the interactions between TM3 and TM6 and induces a consequent outward movement of TM6 in response to G protein binding. The mutations L1283.36A and W2696.48A both decreased the activation efficacy in our cAMP accumulation assay (Supplementary information, Fig. S6b). The activation process of S1PR1 with participation from L3.36–W6.48 appears similar to the activation of the CB1 receptor by the “twin toggle switch” residues F2003.36 and W3566.48 (Supplementary information, Fig. S6c).23,34 Interestingly, the reconfiguration of residues 3.36–6.48 was also found to act as a mechanical activation switch in MC4R.35 Thus, our structural observations suggest that residues L1283.36–W2696.48 in S1PR1 are also a “twin toggle switch”, and this switch is associated with lipid receptor activation.

In contrast to the typical P5.50–I3.40–F6.44 motif in most class A GPCR families, the homologous corresponding residues in S1PR1 are L5.50, V3.40, and F6.44. Interestingly, S1PR1, S1PR5, and several lipid receptors have leucine or isoleucine at position 5.50 instead of proline, which makes TM5 a more rigid helix connecting the orthostatic site and G protein–coupled domain compared with that of activated μOR and β2AR (Supplementary information, Fig. S6d). As observed in the structures of active S1PR1 and inactive S1PR1, F2656.44 adopts distinct rotameric conformations, which cause notable rearrangement of the D/E–R3.50–Y and N–P7.50–xx–Y7.53 motifs that function as microswitches (Fig. 4d). The ionic lock between residues R3.50 and N6.30 in TM3 and TM6, respectively, and the intrahelical salt bridges between R3.50 and E3.49 are disrupted (Fig. 4d), releasing constraints on the relative movement of TM6 and creating more cavities for G protein binding. Distinct inward movement of the cytoplasmic portion of TM7 is accompanied by rearrangement of TM6, in which residue Y3117.53 points into the interior of the TM domain during S1PR1 activation (Fig. 4d). This striking behavior of conserved motifs is observed in all family A GPCRs for which active- and inactive-state structural data are available.36 Superposition of S1PR1 and S1PR5 reveals that these receptors adopt similar conformations of critical motifs (Supplementary information, Fig. S6e–g), which suggests that S1PR5 uses the same activation process as S1PR1.

Comparison of S1PR1/S1PR5–Gi complexes

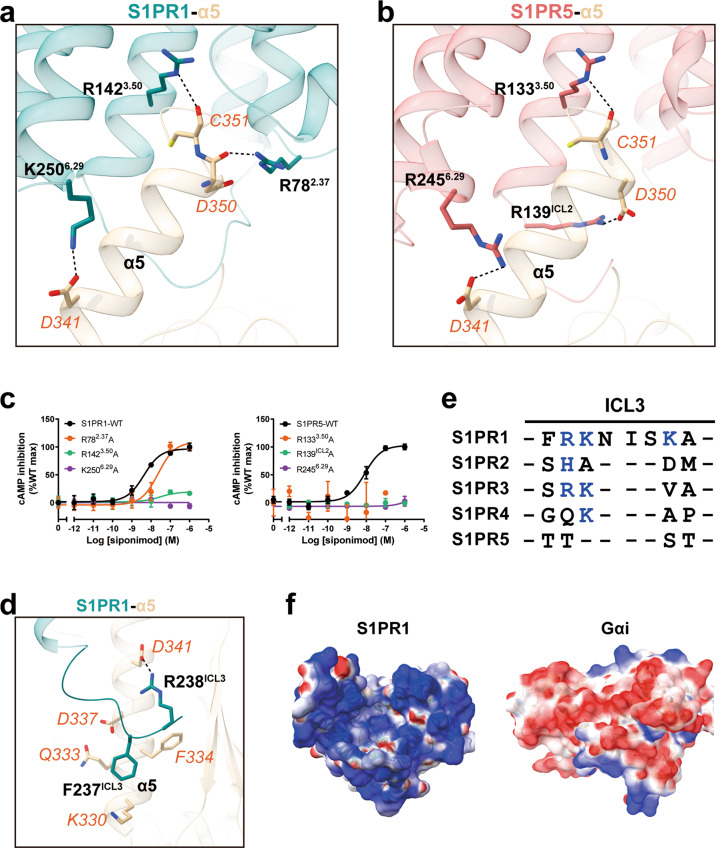

The overall structures of the S1PR1–Gi and the S1PR5–Gi complexes revealed a similar coupling mode of receptors to the heterotrimeric G protein.37 The main interface is mediated through the C-terminal α5 helix of the Gαi subunit with the cytoplasmic cavity of the receptor formed by TM3, TM5, TM6, and TM7 (Fig. 5a, b). Additional contacts are observed between the α5 helix of Gαi and ICL regions. Among the direct contacts, three polar interactions play an important role in Gi protein anchoring: (i) the end of Gαi inserts into the core of the cytoplasmic cavity via ionic contact of the main chain of C351G.H5.23 in Gαi with R3.50 in S1PR1; (ii) D350G.H5.22 from one side of Gαi forms direct contacts with R782.37 in S1PR1; and (iii) D341G.H5.13 from another side of Gαi forms a key ionic interaction with K2506.29 in S1PR1 (Fig. 5a). A similar interaction mode was observed for S1PR5, but the notable difference is that R139ICL2 instead of R782.37 of S1PR1 forms a direct interaction with D350G.H5.22 in Gαi (Fig. 5b). In particular, a similar pattern of polar interactions was also observed in the CB1–Gi complex,23 CB2–Gi complex38 and μOR–Gi complex20 (Supplementary information, Fig. S7a–e), suggesting that these three polar interactions probably serve as a key determinant for Gi coupling. Consistent with these observations, our mutagenesis and functional assays showed that either R782.37A or R1423.50A mutations, or the K2506.29A mutation in S1PR1, as well as the equivalent mutations in S1PR5, caused a significant decrease in receptor activation compared with the wild-type response to agonists (Fig. 5c; Supplementary information, Table S3). In addition to these polar contacts, the hydrophobic side of Gαi forms extensive contacts with the residues of TM3, TM5, TM6 and ICL2, and ICL3 (Supplementary information, Fig. S7f, g).

Fig. 5. Comparison of the receptor–G protein interface between S1PR1–Gi and S1PR5–Gi complex.

a The polar interactions of S1PR1 (teal) with Gαi α5 helix (tan). The residues R1423.50, R782.37 and K2506.29 of S1PR1 and the residues C351G.H5.23, D350G.H5.22 and D341G.H5.13 of Gαi are shown as sticks. Polar interactions are highlighted as black dashed lines. b The interactions of S1PR5 (indian red) with Gαi α5 helix. c Effects of the R782.37A, R1423.50A and K2506.29A mutations of S1PR1 and the equivalent residue mutations in S1PR5 on agonist siponimod-induced signaling activation. Data are presented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. d Detailed interactions between ICL3 of S1PR1 (teal) and α5 helix of Gαi (tan). The residues from S1PR1 are shown in black font, and the residues belonging to α5 are shown in orange font. e Sequence alignment of ICL3 in S1PR subfamily. Positively charged residues are highlighted in blue. f Surface representation of charge property of S1PR1 (left, intracellular view) and Gαi subunits (right, top view) colored according to their electrostatic charge.

In addition to the TM domains, the cytoplasmic loops, particularly ICL2 and ICL3, are postulated to contribute to G protein interactions following activation.39 In our structural comparison, the ICL2 region in S1PR1 packs against the α5 helix more tightly than that observed for S1PR5, and detailed analysis will be discussed in the next section. Moreover, in the structure of the S1PR1–Gi complex, particular residues (R233–K239) from the ICL3 region form direct contacts with one side of the α5 helix in Gi through hydrophobic interactions and salt bridges (Fig. 5d). Consistent with these observations, the R238ICL3A substitution disrupted the R238ICL3–D341G.H5.13 interaction, leading to a 5-fold reduction in the potency of signaling activation (Supplementary information, Fig. S7h). Further sequence analysis revealed that the ICL3 region and the intracellular end of TM6 in each receptor are rich in basic residues (Fig. 5e), which is consistent with the “positive-inside rule” for integral membrane proteins.40 Alanine replacement of those positively charged residues in ICL3 impaired Gi activation markedly (Supplementary information, Fig. S7h), which suggests that electrostatic interactions between receptors and G proteins contribute to receptor activation (Fig. 5f). In agreement, a similar interaction was reported to play a key role in determining Gi protein coupling by members of Gi-coupled GPCRs.20,41

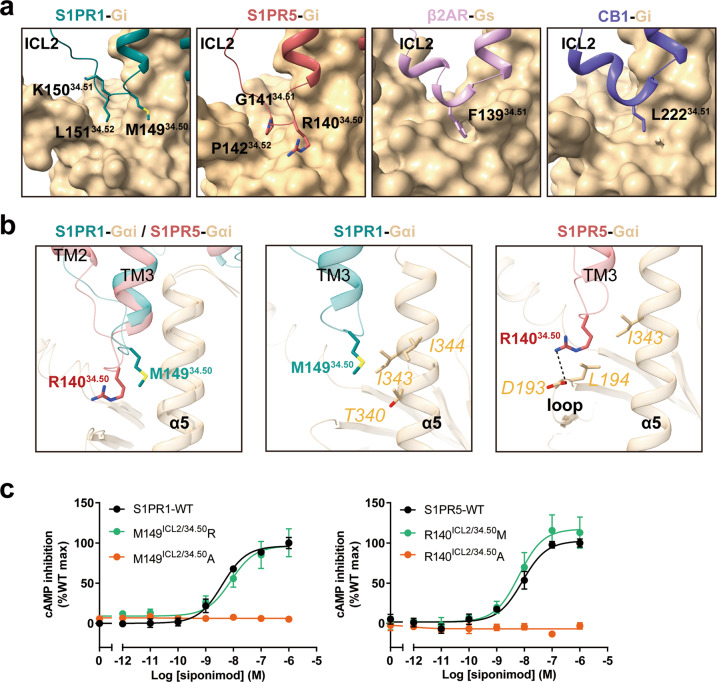

Role of ICL2 of S1PR1 and S1PR5 in Gi coupling

In many GPCRs, the ICL2 region folds into a short α-helix when the receptor is in the active state and has been hypothesized to be a key determinant for G protein coupling selectivity.42 In contrast, the ICL2 region of S1PR1 or S1PR5 lacks a secondary structure and adopts a disordered conformation by tightly interacting with the α5 helix of the Gi protein (Fig. 6a; Supplementary information, Fig. S8a–d). As a result, the α5 helix of Gi coupled to S1PR1 rotates away from ICL2 and TM3, leading to a notable displacement compared with the CB1–Gi complex (Supplementary information, Fig. S8e). β2AR was reported to initiate signaling through the Gs protein, whereas S1PR1 and S1PR3 primarily couple to the Gi protein. The critical role of the ICL2 region of S1PRs in G protein selectivity was examined by replacing the ICL2 region of S1PR1 with that of β2AR. This replacement of the ICL2 region caused an increase in basal Gs signaling induced by S1PR1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S8f). Because S1PR3 has higher basal Gi activity than S1PR1, mutual exchange of the ICL2 region between S1PR1 and S1PR3 lead to increase of S1PR1 basal activation but decrease of S1PR3 basal activation compared with that of the wild-type receptor, respectively (Supplementary information, Fig. S8g). The findings suggest that the ICL2 region of S1PRs is involved in the determination of G protein selectivity.

Fig. 6. Role of ICL2 of S1PR1 and S1PR5 in Gi coupling.

a Comparison of contacts between ICL2 regions of the receptors and Gα subunit. ICL2 regions from S1PR1 (teal), S1PR5 (indian red), β2AR (plum) and CB1 (slate blue) are shown as cartoon and Gα subunit from each receptor complex is shown as surface representation. b Structural superposition of ICL2 regions between the S1PR1–Gi complex and S1PR5–Gi complex when aligned on the receptor (left panel). Detailed interactions of M149ICL2/34.50 of S1PR1 with Gαi (middle panel) and R140ICL2/34.50 of S1PR5 with Gαi (right panel) are shown. c Effects of M149ICL2/34.50 mutants of S1PR1 (left) and R140ICL2/34.50 mutants of S1PR5 (right) on siponimod-induced Gi signaling activation potency. Data are presented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

The difference observed from structures substantially changes the ICL2–Gi interface organization in the S1PR1 complex (Fig. 6a). In CB1 and CB2 receptors, L222ICL2/34.51 and the equivalent P139ICL2/34.51 bind in a hydrophobic pocket formed by L194G.S3.01, I343G.H5.15, T340G.H5.12, and F336G.H5.08 in Gαi and likely play an important role in G protein activation or selectivity23,38 (Supplementary information, Fig. S8h, i). Distinct from those Gi-coupled receptors, the corresponding amino acids at position ICL2/34.51 in S1PR1 and S1PR5 are lysine and glycine, respectively, which are not observed to form a hydrophobic interaction with Gαi. Instead, another two residues at positions ICL2/34.50 and ICL2/34.52 (M149ICL2/34.50 and L151ICL2/34.52 in S1PR1, R140ICL2/34.50 and P142ICL2/34.52 in S1PR5) bind in a hydrophobic pocket in Gαi which is also observed in β2AR–Gs or CB1–Gi complexes and is occupied by the residue at position ICL2/34.51 in either β2AR or CB1 (Fig. 6a).

The ICL2 region of S1PR1 appears to be closer to the α5 helix in Gi than that observed for the S1PR5–Gi complex. Mutations of L151ICL2/34.52 in S1PR1 and P142ICL2/34.52 in S1PR5 retained similar activation potency compared with the corresponding wild-type receptors (Supplementary information, Fig. S8j, k). In our structures, M149ICL2/34.50 in S1PR1 forms extensive hydrophobic interactions with the α5 helix of Gi (including I344G.H5.16, I343G.H5.15, and T340G.H5.12), whereas R140ICL2/34.50 in S1PR5 has potential contact with D193G.s2s3.02 in Gαi via formation of a salt bridge (Fig. 6b). To determine the exact role of these residues in Gi activation, we initially generated mutations M149ICL2/34.50R in S1PR1 and R140ICL2/34.50M in S1PR5. The results from our functional assays revealed that these mutants displayed similar activation ability as the wild-type receptors. In contrast, further mutations of M149ICL2/34.50A in S1PR1 and R140ICL2/34.50A in S1PR5 nearly abolished potency of activation (Fig. 6c). Collectively, M149ICL2/34.50 of S1PR1 and R140ICL2/34.50 of S1PR5 are key determinants for Gi protein coupling.

Discussion

In this study, we reported the cryo-EM structures of the lipid-sensing G protein-coupled receptors S1PR1 and S1PR5 in complex with heterotrimeric Gi. The structures of both S1PR1 and S1PR5 revealed a conserved ligand-binding pocket consisting of a polar module and a hydrophobic cavity. The structures also revealed a gap between TM1 and TM7 in the extracellular leaflet, which may contribute to a membrane-embedded access channel for ligand entry.43 Further analysis showed that R2927.34 in S1PR1 is replaced by Q2877.34 in S1PR5 (Supplementary information, Fig. S8l, m), and the different extracellular vestibules in the GPCR subfamily have been reported to contribute to the ligand access path and selectivity.44 The possible mechanism of ligand selectivity in both S1PR1 and S1PR5 was explored by mutating residues in both receptors and carrying out signaling assays. R292Q7.34 in S1PR1 and Q287R7.34 in S1PR5 did not change receptor activation upon siponimod binding, whereas R292Q7.34 in S1PR1 decreased SEW2871-induced receptor potency and Q287R7.34 in S1PR5 increased the receptor potency (Supplementary information, Fig. S8n–q).

Moreover, accompanied by the rearrangement of F2105.47 in S1PR1, residues L3.36 and W6.48 undergo conformational displacements similar to those in the CB1 receptor, and this “twin toggle switch” mechanism of S1PR1 appears to function in the activation of S1PRs. In addition, the conserved polar networks and ICL2 region participate in Gi coupling to S1PRs, whereas the structural differences result in a notable difference in the relative orientation of the α5 helix in Gi coupling to the two receptors. As reported previously, the ICL2 region is likely to play a major role in determining Gs/Gi protein selectivity by GPCRs. Although the S1PRs have a highly conserved sequence, S1PR1 couples exclusively to Gi, whereas S1PR5 is reported to couple to Gi and G12/13. Differences in sequence and conformation are observed in the ICL2 region of S1PRs, which indicates that ICL2 may play versatile roles in either receptor activation or G protein selectivity.42

Materials and methods

Constructs

The human S1PR1 and S1PR5 cDNAs were cloned into the pFastBac1 vector with the haemagglutinin (HA) signal sequence followed by a Flag epitope tag at the N-terminus. To facilitate receptor expression and purification, a synthetic DNA sequence for translating T4 lysozyme (T4L) was inserted to the N-terminus of S1PR1. In addition, the amino acids 338–382 at C-terminus of S1PR1 as well as the amino acids 345–398 at S1PR5 were removed. The wild-type human Gai1 version (UniProt: P63096) was cloned into the pFastBac1 vector without any modifications. The human Gβ1 containing N-terminal hexahistidine-tag and the human Gγ2 were cloned into a pFastBac-dual vector for co-expression. The synthetic cDNA of single-chain variable fragment scFv16 that is utilized to further enhance the nucleotide-free Gi complex stability was cloned into pFastBac1 vector containing a GP67 secretion signal before the N-terminus of the protein and hexahistidine-tag at the C-terminus.

Expression and purification of scFv16

The procedures of expression and purification were performed as previously described.20 Briefly, the His-tagged scFv16 protein was expressed in secreted form in Trichoplusia ni Hi5 insect cells using Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus system (Invitrogen) and purified by Ni-NTA resin. The eluted protein was further loaded into a size exclusion column (Superdex 200 16/60) equilibrated in a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 and 100 mM NaCl. The fractions containing pure protein were collected and concentrated to 10 mg/mL, then the protein was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and was stored at −80 °C for further use.

Expression and purification of S1PRs-Gi complex

The Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells were used to co-express receptors–Gi complexes in this study. The Sf9 cells were infected at a cell density of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL with three separate viruses at a ratio of 1:2:1 for S1PR1 or S1PR5, Gαi1 and Gβ1γ2, respectively. The infected cells were cultured at 27 °C with 8000 × g for 48 h and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were stored at −80 °C for further use.

Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 160 μg/mL benzamidine, 100 μg/mL leupeptin, supplemented with 10 µM agonists (siponimod or cenerimod or ozanimod or SEW2871) and scFv16 (30 μg/mL) and apyrase (25 mU/mL, NEB). The suspension was incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The membranes were solubilized by 0.5% (w/v) lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG; Anatrace) supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) cholesteryl for 2 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was isolated by centrifugation at 65,000 × g for 30 min, and incubated with M1 anti-Flag affinity resin in the presence of 5 mM CaCl2 for 2 h at 4 °C. The resin was transferred to a gravity column and washed with 30 column volumes of Flag-resin wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2, 5 μM agonists, 0.01% (w/v) LMNG and 0.001% (w/v) cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS)). The bound complex was eluted with 10 column volumes of elute buffer containing 10 mM EDTA and 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide. The concentrated sample was loaded onto a Superdex 200 10/300 increase size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) that was pre-equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.00075% (w/v) LMNG, 0.00025% glyco-diosgenin (GDN; Anatrace) and 0.0001% (w/v) CHS, and 5 µM agonist. Peak fractions of complex were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter (MWCO, 100 kDa).

Cryo-grid preparation and EM data collection

Three microliters of protein solution was applied onto glow-discharged (60 s) 200-mesh Au R2/1 or 300-mesh Au R1.2/1.3 Quantifoil grids. The grids were blotted for 2–3 s and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher). Samples were loaded in a Titan Krios cryo-electron microscope (Thermo Fisher) operated at 300 kV in one of the following settings: condenser lens aperture 70 μm, spot size 4, magnification at 105,000× (corresponding to a calibrated sampling of 0.855 Å per physical pixel), and a K3 direct electron device equipped with a BioQuantum energy filter operated at 20 eV (Gatan); condenser lens aperture 50 μm, spot size 5, magnification at 165,000× (corresponding to a calibrated sampling of 0.85 Å per physical pixel), and a K2 direct electron device equipped with a BioQuantum energy filter operated at 20 eV (Gatan). Movie stacks were collected automatically using EPU2 software (Thermo Fisher) with the K3 (or K2) detector operating in counting mode at a recording rate of 16 (or 5) raw frames per second and a total exposure time of 2 (or 7) s, yielding 32 (or 35) frames per stack and a total dose of 63 (or 56) e–/Å2.

Image processing and 3D reconstructions

The movie stacks were motion corrected using Motioncor2.45 After CTF estimation by CTFFIND4,46 selected micrographs were subjected to EMAN2.3147 for neural network particle picking, with a threshold setting of 0.1 used to maximize inclusion of good particles. The resulting picked particles were extracted in Relion 3.1, with the box size as 256 pixels.48 After two rounds of 2D classifications, the best classes selected by visual examination were subjected to cryoSPARC3.149 ab initio to generate initial models. The resulting particles were then subjected to a combination of multiple rounds of cryoSPARC heterogeneous refinement and Relion 3D classification. The resulting best 3D classes by visual examination were subjected to cryoSPARC non-uniform refinement. A measured B factor was used for sharpening to yield the final sharpened map, which was displayed in UCSF Chimera.50 Details for each cryo-EM reconstruction could be found in Supplementary information, Table S1.

Model building and structure refinement

The initial template of Gi protein and scFv16 was built from the cryo-EM structure of the CB2–Gi complex (PDB: 6PT0), and the initial S1PR1 receptor model was generated by the swiss-model that is a fully automated protein structure homology-modeling server.51 All models were fit into the EM density map by using UCSF Chimera1.14,50 followed by iterative rounds of manual adjustment and real-space refinement using Coot 0.8.9.252 and Phenix 1.19,53 respectively. The models were validated using MolProbity.54 The final structures showed a good model geometry, and the detailed refinement statistics are provided in Supplementary information, Table S1. Structural figures were mapped with UCSF ChimeraX1.155 and PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/). For ozanimod-bound S1PR1 structure determination, we used the high-resolution structure of siponimod-bound S1PR1 as a reference to get the model of ozanimod-bound S1PR1. Because siponimod adopts the same conformation in both S1PR1 and S1PR5 structures, and the orthosteric pockets in those receptors are highly conserved, the N-terminus in ozanimod-bound S1PR1 is reliable. For siponimod-bound S1PR5 structure, despite of the weak density in the extracellular region in S1PR5, the N-terminus displays the similar conformation with that in S1PR1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S1h). In addition, fusion protein T4L is not observed in the map of S1PR1, due to the flexibility of T4L at the N-terminus of receptor.

S1PRs–Gi-mediated cAMP inhibition assay

The cDNA sequences of wild-type S1PR1 and S1PR5 were cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1+ with a HA signal sequence followed by a Flag tag at the N-terminus. Site-directed mutations in both receptors were generated using Q5 site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (NEB). All constructs used in this study were expressed in CHO-K1 cells using jetPRIME transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection, France) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were harvested 48 h post transfection. Cell surface expression levels of receptors were determined by ELISA.

To measure cAMP inhibition effects on forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation of S1PRs, the GloSensor cAMP assay (Promega) was performed as described in the previous study.56 Briefly, Flag-tagged wild-type human S1PR1 and S1PR5 were co-expressed with GloSensor plasmid in CHO-K1 cells in 6-well culture plates. After at least 24 h, transfected cells were harvested and suspended in assay buffer Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, with additional 3% v/v dilution of the d-Luciferin-Potassium Salt (YEASEN, 40902ES03). The ligands used in this study were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma) to a stock concentration of 10 mM and followed by serial dilution using HBSS solution immediately before ligand stimulation. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, cells were stimulated by agonist (diluted in assay buffer containing foreskin) for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the luminescence signals were counted on Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek). Each measurement was repeated in at least three independent experiments, each in triplicate. Data were processed using the nonlinear regression (curve fit) dose-response function in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Measurement of receptor cell-surface expression by ELISA

To measure the cell surface expression level of receptors, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed in our study as described in the previous study.57 Briefly, CHO-K1 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type and mutants of S1PR1 and S1PR5 (pcDNA3.1+ as a vehicle) using jetPRIME transfection reagent. After 24 h incubation, the transfected cells were plated in poly-lysine-coated 96-well cell culture plates and incubated overnight. The next day, the cells were washed twice using Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), and then were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA at room temperature for 30 min. Anti-Flag HRP conjugate was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, HRP substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added. Reactions were quenched by adding 2 M H2SO4 solution and the optical density at 450 nm was measured using the Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek). Each measurement was repeated in at least four independent experiments performed in triplicate. Values were normalized to the wild-type receptor and graphed as a percentage of wild-type using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Cryo-EM data were collected at SKLB West China Cryo-EM Center in Sichuan University and Cryo-EM Center in Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech), processed at SKLB Duyu High Performance Computing Center in Sichuan University. This work was supported by Sichuan University start-up funding (20822041D4057 to Z. Su), the Natural Science Foundation of China grants (82041016 and 32070049 to Z. Su); Ministry of Science and Technology of China grant (2019YFA0508800 to Z. Shao), Science and Technology department of Sichuan Province (2020YJ0208 to Z. Shao).

Author contributions

Z. Shao, W.Y. and C.W. designed the cellular assays and analyzed results. Y.Y., W.W. and C.W. designed the expression constructs, purified the S1PRS–Gi–scFv16 complex, prepared the final samples for data collection toward the structures, and participated in figure and paper preparation with assistance from Q.L., Z.L., K.L. and S.Y.; Z. Su designed the cryo-EM experiments; G.J. prepared the cryo-EM grids, collected and processed cryo-EM data under the supervision of Z. Su; Y.Y., L.C. and G.J. built and refined the models under the supervision of Z. Shao and Z. Su; Z. Shao supervised the overall project, and wrote the paper.

Data availability

All data produced or analyzed in this study are included in the main text or the Supplementary Materials. The cryo-EM density maps and atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession numbers EMD-31341 and 7EVY for the siponimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31342 and 7EVZ for cenerimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31343 and 7EW0 for the ozanimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31349 and 7EW7 for the SEW2871–S1PR1 complex; and EMD-31344 and 7EW1 for the siponimod–S1PR5 complex.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yuan Yuan, Guowen Jia, Chao Wu, Wei Wang.

Contributor Information

Wei Yan, Email: weiyan2018@scu.edu.cn.

Zhaoming Su, Email: zsu@scu.edu.cn.

Zhenhua Shao, Email: zhenhuashao@scu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41422-021-00566-x.

References

- 1.Obinata H, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and inflammation. Int. Immunol. 2019;31:617–625. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proia RL, Hla T. Emerging biology of sphingosine-1-phosphate: its role in pathogenesis and therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1379–1387. doi: 10.1172/JCI76369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen H, Stevens RC, Hanson M, Roberts E, Oldstone MB. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors: structure, signaling, and influence. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:637–662. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062411-130916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jozefczuk E, Guzik TJ, Siedlinski M. Significance of sphingosine-1-phosphate in cardiovascular physiology and pathology. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;156:104793. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kihara Y, Maceyka M, Spiegel S, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature review: IUPHAR Review 8. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014;171:3575–3594. doi: 10.1111/bph.12678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendelson K, Zygmunt T, Torres-Vázquez J, Evans T, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling regulates proper embryonic vascular patterning. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:2143–2156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.427344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelson K, Evans T, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling. Development. 2014;141:5–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.094805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelletier D, Hafler DA. Fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:339–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1101691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrc2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu-Farha M, et al. The role of lipid metabolism in COVID-19 virus infection and as a drug target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3544. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyckman AJ. Modulators of sphingosine-1-phosphate pathway biology: recent advances of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) agonists and future perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:5267–5289. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strader CR, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH. Fingolimod (FTY720): a recently approved multiple sclerosis drug based on a fungal secondary metabolite. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:900–907. doi: 10.1021/np2000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wacker D, Stevens RC, Roth BL. How ligands illuminate GPCR molecular pharmacology. Cell. 2017;170:414–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Salama ZT. Siponimod: first global approval. Drugs. 2019;79:1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb YN. Ozanimod: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott FL, et al. Ozanimod (RPC1063) is a potent sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1) and receptor-5 (S1P5) agonist with autoimmune disease-modifying activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016;173:1778–1792. doi: 10.1111/bph.13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan EM, Haddadi N, Nassif NT, Lin Y. Targeting the SphK-S1P-SIPR pathway as a potential therapeutic approach for COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7189. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson MA, et al. Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2012;335:851–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1215904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koehl A, et al. Structure of the micro-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex. Nature. 2018;558:547–552. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohno T, Igarashi Y. Roles for N-glycosylation in the dynamics of Edg-1/S1P1 in sphingosine 1-phosphate-stimulated cells. Glycoconj. J. 2004;21:497–501. doi: 10.1007/s10719-004-5540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrencik JE, et al. Crystal structure of antagonist bound human lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1. Cell. 2015;161:1633–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna Kumar K, et al. Structure of a signaling cannabinoid receptor 1-G protein complex. Cell. 2019;176:448–458.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan S, et al. Discovery of BAF312 (Siponimod), a potent and selective S1P receptor modulator. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:333–337. doi: 10.1021/ml300396r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. Diverse GPCRs exhibit conserved water networks for stabilization and activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:3288–3293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809251116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mobbs JI, et al. Structures of the human cholecystokinin 1 (CCK1) receptor bound to Gs and Gq mimetic proteins provide insight into mechanisms of G protein selectivity. PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cartier A, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate: Lipid signaling in pathology and therapy. Science. 2019;366:eaar5551. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanna MG, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor subtypes S1P1 and S1P3, respectively, regulate lymphocyte recirculation and heart rate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13839–13848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flemming S, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 agonist Sew2871 causes severe cardiac side effects and does not improve microvascular barrier breakdown in sepsis. Shock. 2018;49:71–81. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsolais D, et al. Local not systemic modulation of dendritic cell S1P receptors in lung blunts virus-specific immune responses to influenza. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:896–903. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujiwara Y, et al. Identification of the hydrophobic ligand binding pocket of the S1P1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2374–2385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609648200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizuno H, Kihara Y. Druggable lipid GPCRs: past, present, and prospects. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1274:223–258. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-50621-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao, C. et al. Structural insights into sphingosine-1-phosphate recognition and ligand selectivity of S1PR3-Gi signaling complexes. Cell Res.10.1038/s41422-021-00567-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.McAllister SD, et al. Structural mimicry in class A G protein-coupled receptor rotamer toggle switches: the importance of the F3.36(201)/W6.48(357) interaction in cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48024–48037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israeli H, et al. Structure reveals the activation mechanism of the MC4 receptor to initiate satiation signaling. Science. 2021;372:808–814. doi: 10.1126/science.abf7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manglik A, Kruse AC. Structural basis for G protein-coupled receptor activation. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5628–5634. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hua T, et al. Activation and signaling mechanism revealed by cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex structures. Cell. 2020;180:655–665.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing C, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human cannabinoid receptor CB2-Gi signaling complex. Cell. 2020;180:645–654.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013;494:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gavel Y, Steppuhn J, Herrmann R, von Heijne G. The ‘positive-inside rule’ applies to thylakoid membrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 1991;282:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80440-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu P, et al. Structures of the human dopamine D3 receptor-Gi complexes. Mol. Cell. 2021;81:1147–1159.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flock T, et al. Selectivity determinants of GPCR-G-protein binding. Nature. 2017;545:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature22070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shao Z, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of the human CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Nature. 2016;540:602–606. doi: 10.1038/nature20613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu X, et al. Binding pathway determines norepinephrine selectivity for the human beta1AR over beta2AR. Cell Res. 2021;31:569–579. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang G, et al. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheres SHW. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao P, et al. Ligand recognition and allosteric regulation of DRD1-Gs signaling complexes. Cell. 2021;184:943–956.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ping YQ, et al. Structures of the glucocorticoid-bound adhesion receptor GPR97-Go complex. Nature. 2021;589:620–626. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03083-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data produced or analyzed in this study are included in the main text or the Supplementary Materials. The cryo-EM density maps and atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession numbers EMD-31341 and 7EVY for the siponimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31342 and 7EVZ for cenerimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31343 and 7EW0 for the ozanimod–S1PR1 complex; EMD-31349 and 7EW7 for the SEW2871–S1PR1 complex; and EMD-31344 and 7EW1 for the siponimod–S1PR5 complex.