Summary

A critical challenge in genetic diagnostics is the computational assessment of candidate splice variants, specifically the interpretation of nucleotide changes located outside of the highly conserved dinucleotide sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends of introns. To address this gap, we developed the Super Quick Information-content Random-forest Learning of Splice variants (SQUIRLS) algorithm. SQUIRLS generates a small set of interpretable features for machine learning by calculating the information-content of wild-type and variant sequences of canonical and cryptic splice sites, assessing changes in candidate splicing regulatory sequences, and incorporating characteristics of the sequence such as exon length, disruptions of the AG exclusion zone, and conservation. We curated a comprehensive collection of disease-associated splice-altering variants at positions outside of the highly conserved AG/GT dinucleotides at the termini of introns. SQUIRLS trains two random-forest classifiers for the donor and for the acceptor and combines their outputs by logistic regression to yield a final score. We show that SQUIRLS transcends previous state-of-the-art accuracy in classifying splice variants as assessed by rank analysis in simulated exomes, and is significantly faster than competing methods. SQUIRLS provides tabular output files for incorporation into diagnostic pipelines for exome and genome analysis, as well as visualizations that contextualize predicted effects of variants on splicing to make it easier to interpret splice variants in diagnostic settings.

Keywords: splicing, splice variant, splice mutation, exome sequencing, genome sequencing, bioinformatics, Mendelian genetics, machine learning, random forest, sequence logo, cryptic splicing

Introduction

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) are effective tools to diagnose Mendelian disorders. However, although the diagnostic yield of WES/WGS has improved from between 16%–25% in early studies1, 2, 3 to around 35%–60% currently,4,5 a substantial proportion of diagnostic cases remains unsolved. One reason is that the filtering and prioritization typically used by diagnostic WES/WGS software is not able to correctly classify some kinds of disease-causing variants. It can be difficult to correctly classify splice-altering variants, especially those deep within exons or introns.6 Variants that affect pre-mRNA splicing are documented to account for at least 15% of disease-causing variants.7 However, the true number may be substantially higher because of a historical ascertainment bias reflecting a selective focus on coding sequences in the pre-next generation sequencing (NGS) era and a continued interpretation bottleneck due to the difficulty of predicting the effects of variants on splicing. For instance, in NF1 (MIM: 613113) and ATM (MIM: 607585), studies have shown that ∼50% of all disease-causing variants result in defective splicing.8,9 Recent results have shown that RNA-seq may be able to identify the diagnosis in up to ∼30% of exome-negative cases,10, 11, 12, 13 and a massively parallel assay suggested that up to 10% of all exonic variants, including missense and nonsense variants, may alter splicing.14 However, RNA samples may not always be available in the diagnostic setting, and the relevant genes and transcripts may not be expressed in tissues commonly assayed for RNA analysis such as blood and muscle. A typical diagnostic exome or genome can contain more than 500 candidate splice-altering variants of unknown significance.15 Therefore, there is a pressing need for algorithmic approaches that can effectively prioritize splice variants in diagnostic next-generation sequencing. Additionally, the interpretability of predictions is important for integration of results into medical workflows.16

For brevity, we use the term splice-altering variant (SAV) to refer to disease-associated DNA variants that result in splice alterations. SAVs can lead to a number of molecular defects including exon skipping, cryptic splicing, intron inclusion, leaky splicing, or the introduction of pseudo-exons into the processed mRNA.17 There are no general rules that allow one to interpret the effect of a variant based solely on the affected sequence context, but it is generally accepted that alterations of the canonical ±1 or ±2 splice sites are most likely to be pathogenic. This is reflected in the fact that the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines state that the location of a variant in these positions can be taken as very strong evidence of pathogenicity in genes where loss of function is a known mechanism.18 However, the natural donor and acceptor splice sites span much longer intervals that overlap the exon-intron boundaries. In addition, the branch point and polypyrimidine tract motifs as well as intronic and exonic splicing enhancers and silencers further modulate the strength of any given splice site. Variants in any of these sequences can reduce or abolish the ability of the spliceosome to recognize the splice site, leading to exon skipping or usage of cryptic splice sites. The sequence between the branch point and the 3′ splice site is generally devoid of AG dinucleotides and is called the AG-exclusion zone; variants that introduce an AG in this zone tend to be pathogenic.19 Additionally, variants in introns or exons can activate cryptic splice sites to the extent that they are preferentially utilized compared to wild-type splice sites. We will use the term “canonical” SAV to refer to variants at the ±1 or ±2 splice sites, and “non-canonical” SAV to refer to any other SAV.

While canonical SAVs are trivial to identify computationally, non-canonical SAVs are substantially more difficult to interpret. Numerous bioinformatics tools such as PolyPhen20 have been developed to assess pathogenicity of missense variants, but far fewer have been developed for non-canonical SAVs. Suggestive evidence exists that non-canonical SAVs might be a more common cause of Mendelian disease than is commonly appreciated.9,19,21 Several previous approaches to prioritizing SAVs are based on the concept of “decrease in surprisal,” grounded on information theory.22 Maximum entropy modeling of splicing signals (MaxEnt) is a similar approach that additionally may include dependencies between nonadjacent as well as adjacent positions.23

Numerous algorithms have been presented for the prioritization of SAVs.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Recently, machine learning methods surpassed previous state-of-the-art results in the prediction of pathogenic SAVs including sequence-based deep neural networks30,31 and gradient boosting trees.15 However, it is not straightforward to interpret the results of these methods. For instance, SpliceAI is a deep residual neural network that predicts whether each position in a pre-mRNA is a splice donor, splice acceptor, or neither; differences in the scores of wild-type and variant sequences can be used to predict pathogenicity of variants, but no information is provided by the algorithm as to what sequence features led to the prediction.31 This makes it challenging to use in a clinical setting, where explainability is essential for clinical decision making. S-CAP uses a gradient-boosting tree (GBT) classifier, with 29 features including predictions from a number of other algorithms; the results of the algorithm are presented as a single score that does not allow further interpretation.15

Here we present a new algorithm, super quick information-content random-forest learning of splice variants (SQUIRLS). SQUIRLS first scores variants according to associated changes in individual information content, changes in splicing regulatory elements (SREs), and several other features, followed by random forest classification. SQUIRLS was trained on a comprehensive dataset of 1,623 non-canonical SAVs. SQUIRLS prioritized more correct variants in the top five ranks, with substantially higher speed and interpretability than the previously proposed best performing methods.15,31 The results can be output with visualizations and assessments of each feature, allowing users to quickly identify the major abnormalities that led to the prioritization. SQUIRLS is an interpretable and fast machine-learning algorithm that assesses variants for potential effects on splicing. SQUIRLS was designed to perform well on difficult-to-classify non-canonical splice variants located outside of the nearly perfectly conserved AG/GT dinucleotides at the termini of introns. We believe that SQUIRLS will support improved and scalable diagnostic capability for clinical interpretation of splice variants identified by WES/WGS.

Material and methods

Dataset of splice variants

We performed an extensive review of the scientific literature to curate a collection of 8,314 splice variants associated with Mendelian diseases. Candidates were derived from a review of ClinVar pathogenic mutations32 and a manual review of the medical literature. We included case reports, mutation updates, and review articles describing variants whose splicing deleteriousness was supported by experimental evidence, such as minigene assay, site-directed mutagenesis, or patient-derived RNA sample analysis. We also included cases where the proband’s phenotype corresponded to the phenotype of the Mendelian disease associated with the affected gene. Our review of ClinVar database focused on synonymous pathogenic mutations as well as on non-canonical SAVs that overlap with canonical splice site regions. The variants are listed in Table S1. The curated variants were located on chromosomes 1–22 and chromosome X (minimum count per chromosome: 77 for chr21; maximum: 1,339 for chrX) and were derived from a total of 4,522 articles with PubMed IDs. 4,753 were assigned to the donor site, 3,388 to the acceptor site, and 173 were not assigned to a specific site. Variants from 1,080 genes were included, with 370 genes with just one SAV, 401 genes with 2–5 SAVs each, 233 genes with 6–20 SAVs, 50 genes with 21–50 SAVs, and 26 genes with more than 50 SAVs.

Dataset of non-deleterious variants

We prepared a collection of 73,203 presumed non-deleterious variants from the ClinVar database.32 After downloading the VCF file released on Nov 11, 2019 from the ClinVar FTP site, we selected variants where both the wt and alt alleles were shorter than 50 bp, whose clinical significance was classified as either benign or likely benign, and that were located in coding region of a gene or distance from the closest exon was less than 100 bp. Each non-deleterious variant was assigned to a donor and/or acceptor site, depending on distance to the site.

Engineering of the splicing features

We developed a set of numeric features to discriminate splicing pathogenic variants from the neutral variants. The features can be separated into three groups: (1) information content features, (2) features representing the sequence context, and (3) variant site features.

The first group of features is related to the individual information content of the affected sequences.22 We compute the individual information content of the closest canonical splice sites and the maximum information content of the surrounding wt sequence to model the inherent potential of the wt sequence for abnormal splicing. Then, the differential information content-based feature is related to changes of free energy of binding of spliceosome components of pre-mRNA induced by the alt allele, according to the Schneider’s derivation from the Second Law of Thermodynamics that shows that a minimum of energy must be dissipated by any molecular machine to gain 1 bit of information.33

The sequence context features include length of the closest exon and the offset (distance in nucleotides) to the closest canonical splice sites to capture potential positional dependencies, The two remaining features of this group identify variants that introduce an AG dinucleotide into the AG exclusion zone (the sequence between the branch point and the 3′ splice site that is devoid of AGs, AGEZ). In our implementation, the AGEZ is defined to be positions −50 to −3, although biologically, the branchpoint is located between −18 and −40 (and not reliably identifiable computationally).

The variant site features are calculated for the nucleotides that are altered by the variant. We use ESRSeq34 and SMS35 to assess changes to splicing regulatory element sequences that are associated with exon skipping and inclusion and may be related to functional elements such as exonic splicing enhancers for which currently no sensitive and specific sequence motifs are available. phyloP evolutionary conservation scoring36 reflects whether the nucleotide or nucleotides altered by the variant are under natural selection against a background of neutral evolution.

In the next section we describe more in detail the construction of the features based on the information content of the sequences. Table 1 provides an overview of features, and the following sections provide additional details.

Table 1.

Features used to discriminate deleterious splice variants from splicing-neutral variants in SQUIRLS

| Splicing feature name | Description |

|---|---|

| Donor | |

| Donor offset | Distance to the exon/intron border of the closest donor site. The number is negative if the variant is located upstream of the border. |

| Rican ref | Information content (Ri) of the closest canonical donor site. |

| max Ri cryptic donor window | Maximum Ri of sliding window of all 9 bp sequences that contain the alt allele. |

| Difference between Ri of ref and alt alleles of the closest donor site (0 if the variant does not affect the site). | |

| Difference between max Ri of sliding window of all 9 bp long sequences that contain the alt allele and Ri of alt allele of the closest donor site. | |

| Difference between Ri of the closest donor and the downstream (3′) donor site (0 if this is the donor site of the last intron). | |

| phyloP | Mean phyloP score of the reference nucleotides altered by the variant, where phyloP denotes conservation scoring calculated by PHAST package for multiple alignments of 99 vertebrate genomes to the human genome.36 |

| Acceptor | |

| Acceptor offset | Distance to the exon/intron border of the closest acceptor site. The number is negative if the variant is located upstream of the border. |

| Difference between Ri of ref and alt alleles of the closest acceptor site (0 if the variant does not affect the site). | |

| Difference between max Ri of sliding window applied to alt allele neighboring sequence and Ri of alt allele of the closest acceptor site. | |

| Exon length | Number of nucleotides spanned by the exon in which the variant is located (−1 for non-coding variants that do not affect the canonical donor/acceptor regions). |

| Creates ‘AG’ in AGEZ | 1 (true) if the variant creates a novel ‘AG’ dinucleotide in AGEZ, 0 (false) otherwise. |

| Creates ‘YAG’ in AGEZ | 1 (true) if the variant creates a novel ‘YAG’ trinucleotide in AGEZ where ‘Y’ stands for pyrimidine derivatives (cytosine or thymine), 0 (false) otherwise. |

| ESRSeq | Estimate of impact of random hexamer sequences on splicing efficiency when inserted into five distinct positions of two different minigene exons obtained by in vitro screening.34,37 |

| SMS | Estimated splicing efficiency for 7-mer sequences obtained by saturating a model exon with single and double base substitutions (saturation mutagenesis derived splicing score).35 |

| phyloP | See above. |

We used 7 features to train site specific random forest classifiers for donor variants, and 9 features to train the classifier for acceptor variants. Note that phyloP is used by both splice donor and acceptor classifiers. Ri - information content of a nucleotide sequence in bits.

Features based on the information content of the sequences

The core features used to train the splice donor and acceptor site models are based on information theory applied to the analysis of splice sites.22 First, to construct a matrix with frequencies of nucleotides occurring at different positions of the splice sites, we aligned wild-type sequences of exon/intron junctions of GENCODE basic gene annotation transcripts v32 (accessed on Oct 2019). We selected 49,821 protein coding transcripts with gene annotation source Havana and GENCODE confidence level ≤2, corresponding to transcripts supported by the highest amount of the experimental evidence.

Then, we grouped the transcripts by gene and identified genomic coordinates of unique exon/intron junctions, producing sets with 200,459 donor and 197,874 acceptor site coordinates. Next, we extracted ±80 bp of the nucleotide sequence surrounding the sites and we subsequently aligned the sequences by exon/intron junction coordinate. After alignment, we calculated a matrix, F4xm where 4 refers to the number of different types of nucleotides and m to the length of the sequences. Each element f(b,l) of the matrix F represents frequencies and estimates a probability of observing base b∈{A,C,G,T} at position l within the aligned sequences (Figure S1). Finally, we created an information weight matrix Riw grounded in the concept of decrease in surprisal38 to model a splice junction by the equation

where is a sample size correction factor for the n sequences at position l.39 The Riw matrix represents the sequence conservation of each nucleotide within the binding site, measured in bits of information. After checking for background noise, we determined the lengths of the donor and acceptor sites to be ldon = 9 bp and lacc = 27 bp (see Figure S1 for more details).

The Riw matrix can be used to calculate the individual information content Ri of any nucleotide sequence j with length m as:

where N = {A,C,G,T} is the set of nucleotides, and A is a 4 x m binary matrix that represents a one-hot encoding of the sequence j: the A matrix has only a single 1 for each column while the remaining elements of the column are set to 0. In effect, each base of the sequence “picks out” a specific entry of the matrix Riw and these entries are finally added to compute the information content of the sequence. In our setting, Riw is a weight matrix representing the splice junction, and the mean values of the Ri distribution for the donor and acceptor sites, that represent the mean information of the sequences used to construct Riw, were 7.87 (donor) and 9.50 (acceptor) bits. The resulting Ri(j) is related to thermodynamic entropy and the free energy of binding and can be used to compare sites with one another.39

Training and test variant sets

We pooled the SAV and neutral variants and then we annotated each variant with splicing features (Table 1) and additional metadata, including label (deleterious or neutral), gene symbol, transcript accession ID, and cytoband. Next, we split the variants into train and test sets by applying a “cytoband-aware” hold-out scheme: we randomly chose 10% (67) of the total number of 676 cytobands, and we put the variants contained in these cytobands into the test set. The variants located in the remaining 90% (609) cytobands were used for training (Figure S2). The cytoband-based scheme was designed to minimize bias resulting from distinct variants located in the same gene being used for both training and testing. Then, we partitioned the training variants into two subsets consisting of either donor or acceptor-affecting variants, based on curation metadata or vicinity to one or the other splice site. We removed 6,008 canonical SAV variants from the training set, since we aimed to optimize the classifier for non-canonical SAVs. We tested SQUIRLS using both the subset of non-canonical SAVs as well as the entire set.

Training of the SQUIRLS model

SQUIRLS is a “paired ensemble” model that predicts the potential of a variant to alter the splicing pattern of an overlapping transcript. The model consists of two random forest classifiers40 trained individually on either the donor or the acceptor variant subset. If features are missing for a data point, they are replaced by the median value prior to random forest analysis.

To train the classifiers and perform model selection, we ran 50 iterations of randomized search cross-validation. In each iteration we randomly sampled hyperparameter values from pre-defined parameter distributions and performed 10-fold cross-validation on the training set. Each cross-validation step included calculation of the following performance metrics: balanced accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. We selected the hyperparameters that produced the model with the highest sensitivity (recall) and we subsequently retrained the donor and acceptor classifiers on the entire variant subset.

Most of the machine learning methods used to identify potential pathogenic variants report predicted deleteriousness/pathogenicity estimates as a number in the range [0,1], where higher scoring variants are more likely to be deleterious.41, 42, 43 In addition, thresholds for assigning variants into discrete classes (e.g., neutral and deleterious) while obtaining the desired specificity or sensitivity are available for most of the methods. In a random forest, probability estimates for a class can be calculated as the proportion of the forest’s decision trees that voted for the class. To find the class probability threshold that attains the best separation of splice and neutral variants, we used the value that maximized the informedness criterion (Youden’s J statistic).

To generate the final SQUIRLS score, we trained a logistic regression model from the raw scores computed by the two random forests, to automatically learn how to better combine their output.

For model training and evaluation, we used random forest, logistic regression, and imputer implementations provided within the Scikit-learn framework.44 For the SQUIRLS application and library, we wrote a custom implementation of the imputer, random forest, and logistic regression. The implementation is available in the SQUIRLS source code repository (web resources).

Model testing, validation, and comparison with other splicing pathogenicity algorithms

To obtain the unbiased performance estimate for SQUIRLS scores, we computed pathogenicity estimates for the test set variants and then we performed ROC and precision-recall analysis. We used the thresholds and evaluated classification accuracy.

We compared the SQUIRLS scores with other algorithms that are used for prioritization of splice variants. We chose two algorithms designed to assess splice variants that performed well in recently published analyses (SpliceAI31 and S-CAP15), an older well-established method (MaxEntScan23), and an algorithm that is commonly used for variant prioritization in WES/WGS experiments even though it was not specifically designed for analysis of splice variants (CADD45). To evaluate the ability of all algorithms to discriminate between the neutral and the splice variants, we calculated predictions for variants and constructed ROC and PR curves. We ran the comparison of runtime performance of SQUIRLS and SpliceAI on a consumer laptop with the following specifications: Intel Core i7-8650U CPU @ 1.90GHz, 8 cores, 32GB DDR4 RAM, M.2 256GB SSD HDD (no GPUs).

SpliceAI

SpliceAI provides four delta scores for each variant where the maximum score denotes a probability of the variant being splice-altering.31 In order to evaluate SpliceAI performance, we precalculated the delta scores for variants in our dataset. We used version 1.3.1 (accessed on April 25, 2020; see web resources) with the ‘-M True’ option to mask scores representing annotated acceptor/donor gain and unannotated acceptor/donor loss. We chose the maximum value to perform ROC and PR evaluation. We benchmarked SpliceAI runtime performance using the Python package spliceai v.1.3.1 available at PyPi. The runtime of spliceai for a single VCF file with ∼100,000 variants is roughly one day, so we benchmarked spliceai on VCF files subsampled to 5,000 variants only.

S-CAP

The S-CAP algorithm provides splicing-specific pathogenicity scores calculated using the gradient-boosting tree (GBT) algorithm.15 The algorithm consists of six GBT predictors, one predictor for each of six author-defined regions relative to the splice site. The authors provide a VCF file with precomputed scores for all possible single nucleotide variants in the splicing region. There are two score types: raw score is the output of the corresponding GBT, and sensitivity score which is a transformed raw score to make it directly comparable with scores of the other regional predictors. We used both raw and sensitivity scores for the ROC and PR evaluation.

MaxEntScan

MaxEntScan is a framework that employs the maximum entropy principle for building a model m that represents a particular sequence motif, including mRNA splice sites.23 During the building phase, a collection of aligned sequences is used to estimate the maximum entropy distribution and a set of constraints. Using this approach, the authors built and evaluated multiple maximum entropy models. For our comparison, we chose the models that yielded the highest AUCs (mme2x5 for the donor and mme2x3 for the acceptor site), as described in the MaxEntScan manuscript.23

In order to allow MaxEntScan to be compared with SQUIRLS, we created a set of rules for constructing nucleotide snippets jwt and jalt to be scored by the appropriate MaxEntScan model m. For each variant, we considered four situations: (1) the variant disrupts the canonical donor site, (2) the variant activates a cryptic donor site, (3) the variant disrupts the canonical acceptor site, and (4) the variant activates a cryptic acceptor site.

For situations (1) and (3), we prepared sequence snippets jwt and jalt for the canonical sites and we calculated the final score DMES as DMES = m(jwt) - m(jalt). For situations (2) and (4), we calculated a score vector s for the sliding window of all n-bp sequences jwt or jalt that contain the wt or alt alleles. Then, the final score was computed as DMES = max(salt) - max(swt). After calculating DMES for all four situations, we used the maximum value as the final pathogenicity estimate for ROC and PR analysis.

Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion

Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) estimates the deleteriousness of variants by integrating multiple annotations into a single score.45 The score is applicable across diverse variant functional categories, including variants affecting mRNA splicing. For comparing CADD with SQUIRLS, we downloaded TSV files with PHRED-scaled pathogenicity scores precalculated for all possible SNVs and INDELs built by the model v.1.4 (accessed on November 20, 2019). For each variant, we transformed the PHRED score into [0,1] by applying . If the score was not available, we considered the variant to be benign (pathogenicity = 0.0). The transformed scores were used for ROC and PR analysis.

Implementation

We designed multiple optimizations to achieve fast runtime performance. SQUIRLS fetches all data required to evaluate a variant’s effect on the overlapping transcripts in a single I/O lookup and all the subsequent operations are performed in memory. An additional performance increase is achieved by limiting the number of splicing features and by exploiting inherent parallelism of the random forest, which can be distributed across multiple CPU cores. The source code of SQUIRLS and a standalone “executable JAR” file are available for download from the GitHub repository (web resources).

Results

SQUIRLS is designed to predict variants associated with splice defects from exome- or genome-sequencing data. All variants that overlap transcripts are evaluated for potential effects on splicing including both variants at the canonical donor and acceptor sequences as well as other exonic and intronic variants that could generate cryptic splice sites or otherwise alter normal splicing. SQUIRLS evaluates the effect of variants with respect to all transcripts that overlap the variant. The output visualizations and tabular assessments are designed for human consumption and can also be used to output a VCF file with annotations of the predictions of relevant splice variants for use in larger bioinformatic pipelines for diagnostic genomics.

Overview of the algorithm

SQUIRLS first calculates a set of numerical features for each variant/transcript pair. The features include changes in information content between reference and alternate alleles (Figure 1), changes in SREs, distances from the canonical splice sites, and a measure of evolutionary conservation. The features were chosen to be interpretable by humans (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3). The features are used as input for a pair of random forest classifiers specialized in computing site-specific splice scores for donor and acceptor sites. The algorithm then uses logistic regression to transform the scores into the final SQUIRLS score that estimates the probability of the variant in question being a splice variant.

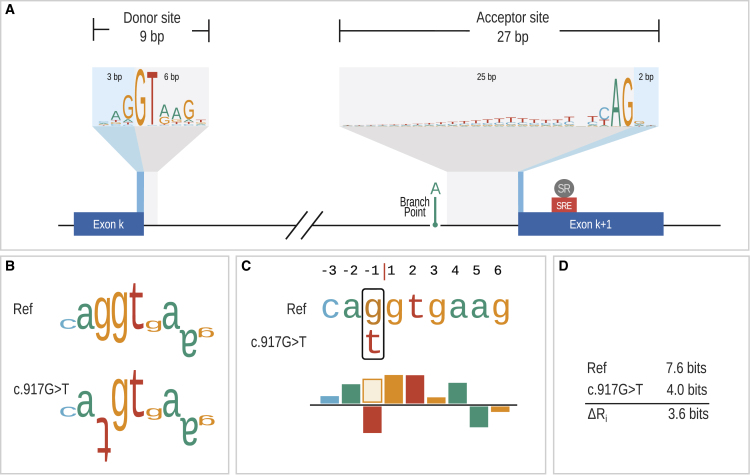

Figure 1.

mRNA splicing and sequence logos/walkers

(A) The figure shows an intron and the corresponding canonical splice donor and acceptor sites, which are represented as logos, where the letters representing the sequence are stacked on top of each other for each position in the splice site. The height of the character stack at each position represents the sequence information gained, Rsequence(l), by aligning wild-type sequences of exon/intron junctions of GENCODE transcripts (material and methods). The heights of the characters within a stack represent contributions of the individual bases to the position.

(B) Individual sequence information (Ri) for a wild-type splice donor sequence of CHRNE (MIM: 100725) and for the corresponding sequence with the variant GenBank: NM_000080.3; c.917G>T (p.Arg306Met). c.917G>T is located at the last (3′ most) position of an exon and although it is predicted to lead to a missense change, it reduces the strength of the donor sequence and leads to skipping of the affected exon.46 The sequence walker representations as introduced by Schneider38 are shown for the wild-type and variant sequences. Sequence walkers display nucleotides that represent favorable contacts to the spliceosome and a test sequence by letters that extend upward and positions that are predicted to make unfavorable contacts are shown by inverted letters.

(C) SQUIRLS introduces a new graphical representation in which a bar chart is used to show the degree to which a sequence “matches” the donor or acceptor model. The height of the bars is calculated in the same way as for the height of the letters in the sequence walker. Positions that are changed by a variant are displayed such that the original nucleotide is shown as an outline (the “g” in this example) and the variant (alternate) base is shown filled.

(D) The variant reduces the Ri from 7.6 to 4.0 bits. Changes in Ri are referred to as . SQUIRLS calculates in several contexts (Figures 2 and 3).

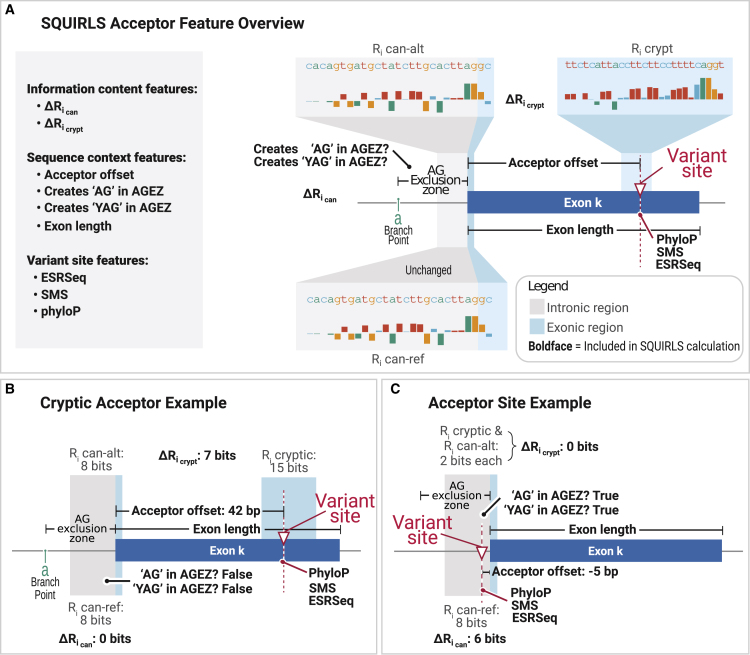

Figure 3.

Calculation of features for the splice acceptor site

(A) SQUIRLS calculates as the difference in the Ri between the reference and alternate sequence of the canonical acceptor sequence (Figure 1A). If the variant is located outside of this sequence, = 0. SQUIRLS evaluates the potential of variants to create cryptic splice sites using a sliding window approach (material and methods). is calculated by subtracting Ri of the alternate sequence of the canonical acceptor site from the Ri of the best candidate cryptic splice site. The random forest for acceptor variants does not use as our initial analysis showed that it did not boost classification performance. See Table 1 for information about other features.

(B) In this example, a coding variant activates a cryptic acceptor site with 15 bits which is greater than the canonical acceptor site by 7 bits ().

(C) A situation where a variant located in a splice acceptor site introduces novel AG dinucleotide into the AGEZ leading to cryptic splicing or exon skipping.

A dataset of non-canonical splice variants

We performed a comprehensive review of scientific literature to curate a dataset of splice variants associated with Mendelian diseases. In total, we collected 8,314 splice variants as well as 73,203 variants classified as benign or likely-benign variants from ClinVar (Tables 2 and S1).32 The distribution of the variants with respect to the donor and acceptor splice site is shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Summary of the variant dataset

| Outcome | Donor |

Acceptor |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-canonical | Canonical | Non-canonical | Canonical | ||

| Cryptic site creation | 143 | 7 | 191 | 13 | 354 |

| Canonical site disrupted | 1,125 | 3,576 | 360 | 2,882 | 7,943 |

| Other | 7 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 17 |

| Totals | 1,275 | 3,583 | 561 | 2,895 | 8,314 |

We created a collection of splice variants by curating literature. During curation, we recorded metadata regarding the variant pathomechanism and the observed outcome. Based on the outcome, we categorized the variants into two major groups: (1) variants disrupting canonical splice sites and leading to activation of a cryptic splice site, or to exon skipping, and (2) variants that activate cryptic splice. 73,203 neutral variants were used as negative training examples. There were 4,858 donor variants and 3,456 acceptor variants. Of these, 1,836 were non-canonical and 6,478 were canonical (i.e., located at the ±1 or ±2 positions).

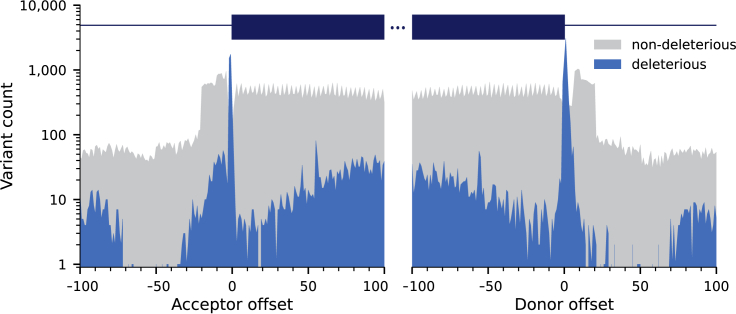

Figure 4.

Distribution of deleterious SAVs and non-deleterious variants used to develop SQUIRLS

The figure shows the distribution of variants used for developing SQUIRLS on a logarithmic scale. The position with respect to the nearest acceptor or donor intron/exon boundary is shown.

In order to prepare the variant dataset for training of machine learning models, we split the dataset into training and test sets. We used a “cytogenetic band-aware” method that ensures that variants affecting the same gene are used for either training or testing, but not both, since nearby variants may share similar features which might bias the results. This way we randomly partitioned the splice and non-deleterious variants into training (609 cytobands, ∼90%) and test (67 cytobands, ∼10%) sets, consisting of 70,617 and 10,901 variants (Figure S2).

Then, we assigned the training set variants to either donor or acceptor sites, based on the curation metadata or distance to the closest splice site. The training set was further narrowed down by removing 6,008 canonical SAVs, yielding the final training set consisting of 1,623 deleterious noncanonical SAVs and 62,986 non-deleterious variants. We chose to train SQUIRLS on non-canonical SAVs, but note that SQUIRLS also displays state of the art performance in the (relatively simple) classification task of predicting deleteriousness of canonical SAVs.

Selection of interpretable features for machine learning

We trained two site-specific random forest classifiers to separate splice variants from neutral variants, one for the donor variants and the other for the acceptor variants. During training, we used random search hyperparameter optimization48 and 10-fold cross-validation to evaluate different combinations of 21 splicing features and learning parameters, to select the combination that provides classifiers with the highest area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and precision-recall scores. The final set of 15 features included features based on information content, changes in candidate 6/7-mer SRE motifs, evolutionary conservation of the variant position, and distance from the closest splice sites (Table 1, Figures 2, 3, and S3). After selecting the best-performing features and learning parameters, we trained the final site-specific classifiers using the entire training set.

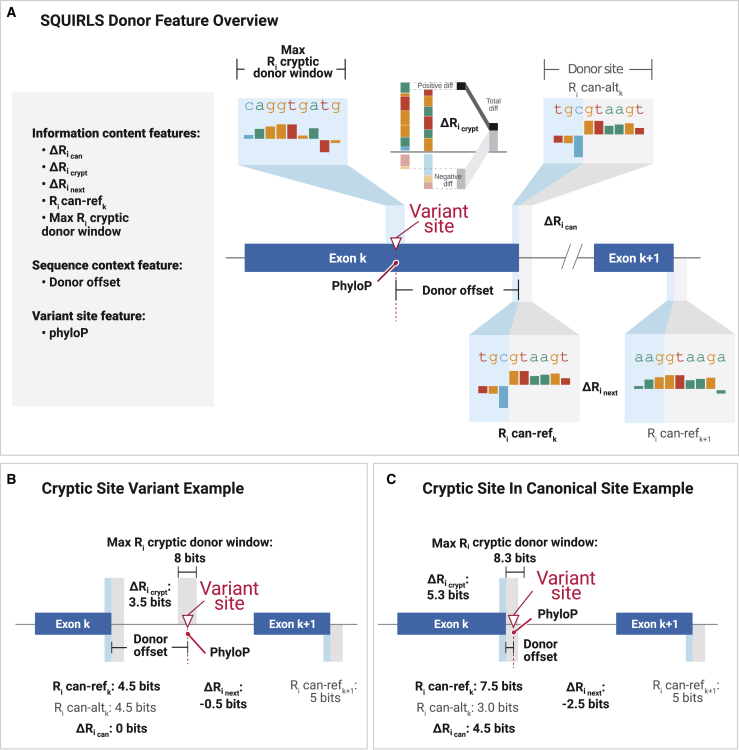

Figure 2.

Calculation of features for the donor site

(A) SQUIRLS calculates seven features to evaluate variant impact on the donor site. The individual information content of the reference and alternate canonical splice site and of the donor site in the following exon (Exon ) are calculated and used to determine the difference in information content between the reference and alternate canonical splice site , the difference between the best candidate cryptic splice site and the alternate sequence of the canonical splice site , and the difference between the donor site at exon k and k+1, because differences in splice site strength can be predictive of exon skipping.14 See Table 1 for information about other features.

(B) In this example, a variant in intron k creates a cryptic splice site with 8 bits, which is greater than the individual information of the canonical splice site (4.5 bits), so = 3.5 bits. The variant does not change the sequence of the canonical splice site, so = 0. The individual information of the donor site of the next exon has 0.5 bits more than that of exon k, so = −0.5 bits.

(C) In this example, a variant in the canonical splice site (e.g., the +5 position) reduces the strength of the canonical splice site from 7.5 to 3.0 bits and simultaneously creates a novel cryptic site with an individual information content of 8.3 bits. An example of this is the variant GenBank: NM_000314.7; c.253+2T>C (PTEN [MIM: 601728]), which alters the canonical splice site and simultaneously changes the sequence of a cryptic splice site located 3 nucleotides downstream, resulting in the inclusion of 4 intronic nucleotides in the variant mRNA.47

The donor and acceptor scores are calculated for all variants. The ranges and thresholds of the acceptor and donor scores are, however, different (Figure S4), which precludes direct integration of the site-specific estimators into variant prioritization frameworks. To combine the donor and acceptor estimators into a single measure, we used logistic regression as the last step of our algorithm. We calculated site-specific deleteriousness estimations for all training variants and we subsequently used the site-specific estimates to obtain logistic regression parameters that provide the best predictions (splice deleterious = 1, neutral = 0). The final SQUIRLS score is the output of the logistic function, integrating the raw scores into a single measure with range [0,1].

Performance evaluation and comparison with other methods

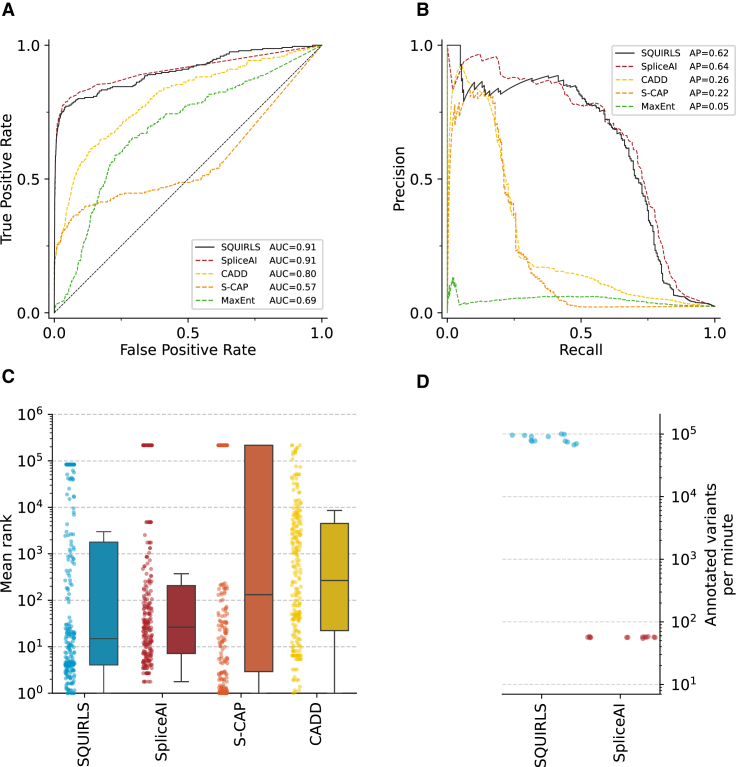

We evaluated SQUIRLS using a test set consisting of 808 splice variants (213 non-canonical SAVs) and 10,092 neutral variants (10,068 non-canonical SAVs) that were not used for training. After calculating SQUIRLS scores for all variants, we assessed diagnostic utility by creating receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision-recall (PR) curves, as well as calculating the area under the ROC (AUROC) and the average precision (AP).

SQUIRLS achieved an AUROC of 0.91 and an AP of 0.62 on a test set consisting only of non-canonical SAVs (Figure 5). Although SQUIRLS does not use canonical (±1 or 2) SAVs for training, it achieved an AUROC of 0.97 and an AP of 0.88 on a dataset that included both canonical SAVs and non-canonical SAVs (Figure S5). These results show that SQUIRLS can accurately identify both easy (canonical) and difficult to assess (non-canonical) SAVs.

Figure 5.

Performance of SQUIRLS, SpliceAI, S-CAP, CADD, and MaxEnt on non-canonical SAVs

(A) Receiver operating characteristic curves indicate that SQUIRLS and SpliceAI achieve comparable performance.

(B) Precision-recall curves show that SQUIRLS and SpliceAI are able to find the most of the true splice variants, while maintaining high precision.

(C) Mean ranks of splice variants among background variants in simulated exome sequencing runs. Each dot represents the mean rank of one of the splice variants in 13 WES simulations. The boxes represent distributions of the mean ranks. The horizontal line of each box indicates the median mean rank, box borders indicate positions of the 1st and the 3rd quartile, and the whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile range.

(D) Comparison of algorithm runtimes for SQUIRLS and SpliceAI. We recorded the time required for analysis of 13 VCF files containing 87,000–107,000 variants. The figure shows the annotation speed that was achieved on a consumer laptop. We could not compare the performance of S-CAP and CADD, since they provide precomputed predictions as tabular files. Therefore, the annotation speed is only dependent on a package used to query the tabular file (e.g., tabix).

We then compared SQUIRLS to four state-of-the-art methods for assessing the pathogenicity of candidate splice variants: SpliceAI,31 a deep residual neural network that predicts whether each position in a pre-mRNA transcript is a splice donor, acceptor, or neither, and S-CAP,15 a gradient-boosting tree approach that provides splicing-specific pathogenicity scores. Moreover, we compared SQUIRLS to MaxEntScan,23 a well-established tool employing maximum entropy principle to model splicing motifs, and to CADD,45 a framework that integrates diverse genome annotations into a single quantitative score to estimate deleterious effect of arbitrary variants and hence not specific for splice variants.

We obtained predictions for variants in the test dataset and constructed ROC curves and PR curves. SQUIRLS and SpliceAI achieved the best AUROC and AP on our test set, largely outperforming the other methods (Figures 5 and S5). We compared the performance of SQUIRLS and SpliceAI according to the variant’s distance from the canonical splice site. Both methods were the most confident in finding splice variants located in canonical splice sites, while assigning lower scores to coding or noncoding variants located outside of the canonical sites (Figure S6).

To further evaluate the expected performance of SQUIRLS in real-life scenarios, we developed a simulation strategy based on 13 VCF files generated by exome sequencing of individuals unaffected by a Mendelian disease. In the simulation, we added a single splice variant to each of the 13 VCF files, then we predicted pathogenicity for all variants, and subsequently ranked the variants according to predicted pathogenicity. Finally, we calculated the rank of the added splice variant averaged over the 13 VCF files.

In order for a prioritization method to be useful, it needs to place causal variants near the top of the list (“on the first page”) such that the causal variant is discoverable during the clinical interpretation. SQUIRLS achieved the best performance, placing 35% of splice variants within the top 5 positions, 50% of splice variants at rank 14 or below (median rank). The second-best method, SpliceAI, achieved a median rank of 25, and the third best method, S-CAP, achieved a median rank of 114 (Figures 5C and S7).

SQUIRLS enables rapid prioritization of arbitrary variants

With an ever-increasing availability of sequencing data, computationally expensive algorithms may quickly become a bottleneck in the sequence data analysis. Precalculating pathogenicity scores for each genome position and storing the predictions in sorted and compressed tabular file or also using parallel hardware devices (e.g., graphics processing unit, GPU) are workarounds commonly used for computationally expensive algorithms. In contrast to single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), this approach does not work well for multi-nucleotide variants or indels, as the number of possible ref/alt allele combinations grows exponentially with increasing variant length. Then, storing pathogenicity prediction for each combination quickly becomes infeasible. Additionally, pre-calculated scores are not always available with respect to a particular transcript. To support pathogenicity prediction for an arbitrary genome variant at scale, the algorithm must be both efficient and easily portable to different computational platforms. SQUIRLS was designed to satisfy these requirements.

Apart from SpliceAI, SQUIRLS is the only tool in our comparison that directly annotates variants in a VCF file. S-CAP does not provide software that can analyze arbitrary variants, and a downloaded file with score mainly for SNVs was used for the comparison. SQUIRLS annotates a VCF file containing 100,000 exome variants in roughly 1 min on a consumer laptop, which is over 1,000 times faster than SpliceAI (Figure 5D). SpliceAI provides both a downloadable file with predictions for SNVs as well as an executable program that can analyze arbitrary variants. SQUIRLS was faster than all competitors except for the lookup of S-CAP predictions (material and methods).

SQUIRLS is written in Java 11 and can be used both as a library as well as a standalone command-line application (see tutorial in online manual in web resources). The command line application is intended to be used with a Variant Call Format (VCF) file from exome or genome sequencing. The application generates output in multiple formats, including HTML report with figures and supporting information (see next section), a tabular file with predictions, and an annotated VCF file that contains pathogenicity predictions with respect to all overlapping transcripts. SQUIRLS also supports pre-computing the pathogenicity predictions for all possible variants in the regions of interest, including SNVs and if desired MNVs up to specified length.

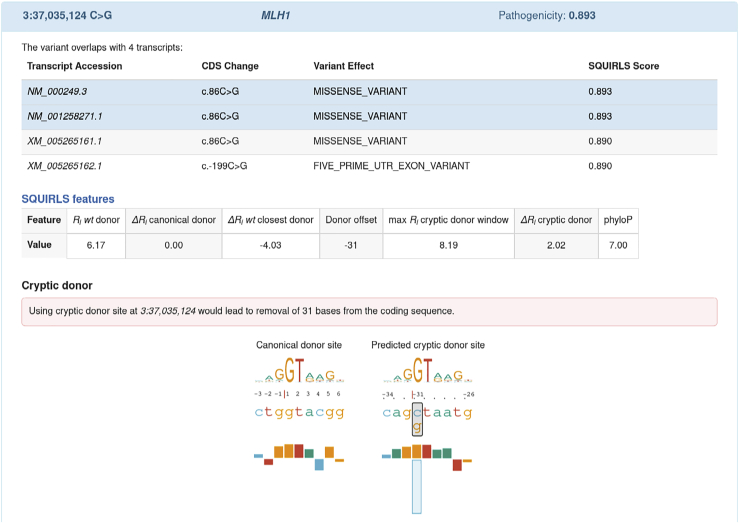

SQUIRLS provides interpretable predictions

The majority of machine learning algorithms that are used as aids in variant prioritization work as black boxes. After making a prediction, the algorithms do not explain how the particular answer was made, which factors were considered, and the insights regarding the most likely molecular cause. When designing SQUIRLS, our motivation was to create an algorithm that is both accurate and interpretable. We addressed these goals by limiting features to a small set of biologically interpretable attributes (Table 1). SQUIRLS can output its results in three ways: (1) by adding annotations to the VCF file; (2) as a tab-separated values (TSV) file that can be easily incorporated into larger analysis pipelines; and (3) as an HTML file that presents the specific values calculated for each of the attributes relevant to a given variant in the context of visualizations that show the most important predicted effects. Figure 6 presents an example of the output produced by SQUIRLS for each candidate SAV.

Figure 6.

Screenshot of SQUIRLS HTML output

The variant GenBank: NM_000249.3; c.86C>G generates a cryptic splice site in MLH1 (MIM: 120426).49 The variant is evaluated with respect to four overlapping transcripts and it is assigned maximum SQUIRLS score = 0.893. Transcripts with predicted maximum SQUIRLS score are highlighted in the table. The variant is located 31 bp upstream of the canonical site of exon 1 and it is predicted to create a cryptic donor site (Ri = 8.19 bits) which is stronger than the canonical donor (Ri = 6.17 bits) by 2.02 bits. Using the cryptic donor site would lead to removal of 31 bases from the coding sequence. Bar charts compare the canonical donor site with the predicted cryptic site. The bar chart shows that the variant replaces cytosine (blue rectangle) with a guanine (orange rectangle). The change is predicted to allow a more favorable contact between spliceosome and the alt allele, resulting in usage of the cryptic site and removing 31 bases from the coding sequence.

Discussion

In this work, we have presented SQUIRLS, an efficient and accurate algorithm for the prioritization of splice variants in exome or genome data. Our approach displays AUROC and AP performance that is comparable or better than that of previously published methods and is superior to these methods with respect to its ability to rank disease-associated variants within the long list of candidate splicing variants found in exomes. In contrast to previous methods, SQUIRLS was designed to leverage a small set of interpretable features and can provide visualizations of the predicted effects of variants on splicing that can help clinical interpretation.

To develop SQUIRLS, we focused on non-canonical splice variants. Canonical variants, defined as those that affect positions ±1 or ±2 of introns, are typically easy to interpret because variants at these positions only rarely do not deleteriously affect splicing. It has been substantially more difficult to develop algorithms that accurately classify splice variants at other positions. For this work, therefore, we performed extensive and detailed curation to identify non-canonical splice variants that are associated with Mendelian disease from the literature and from ClinVar. The resulting dataset, which to our knowledge is the largest of its kind, is freely available (Table S1). We developed a machine learning model using random forests and logistic regression, whereby substantial preprocessing of sequence data is performed to generate a set of 15 features, using also information theory techniques to assess the information content of sequences that include splice variants. Using logistic regression as the final step is essential in this context to improve performance. Indeed, a simple ensemble combination strategy based on averaging the raw scores computed by the random forests, or each random forest alone, worsens the overall performance (data not shown).

While SQUIRLS can be used on its own to specifically look for diagnostically relevant splice variants, it can also be easily used as a component of diagnostic exome/genome pipelines to improve recognition of causal splice variants. We optimized the classifier for high sensitivity to reduce the number of false negatives. In a full WES/WGS analysis pipeline, the false positive rate can be controlled by other strategies available for data analysis such as phenotype-based prioritization.50, 51, 52 For instance, combining the predictions of SQUIRLS with linkage analysis, candidate gene lists, or phenotype analysis would be likely to further improve rankings of causal variants.50,51

Many resources for genomic diagnostics precalculate scores for some subset of all possible variants. For instance, dbNSFP collects functional predictions and annotations for over 80,000,000 human nonsynonymous single-nucleotide variants and splice-site variants from various other algorithms that precompute values for all possible nucleotide changes in specified regions.53 Even if pre-computing indels can be feasible when limited to a few bp and to a specific region or gene panel, this approach does not scale well for the prediction of splicing-relevant variation, which can affect multiple nucleotides and be located at arbitrary intronic and exonic positions. In our study, three of the approaches we compared with SQUIRLS offer precomputed scores but did not cover all tested variants. Of the 243 test variants, CADD missed 3 (1%), SpliceAI missed 27 (11%), and S-CAP missed 108 (43%). For clinical use, it is therefore important to optimize not only recall and precision but to engineer software such that it can analyze a wide range of variants in little time.

A limitation of SQUIRLS and all other approaches for computational prediction of SAVs in WES/WGS data that we are aware of, is that the algorithms predict the existence of an alteration of splicing, but do not attempt to predict the exact defect. In general, SAVs can be associated with a range of splice defects such as exon skipping, partial loss of exonic sequence, complete or partial intron inclusion, and the creation of pseudoexons. We included all available disease-associated SAVs in our training and test sets without reference to molecular mechanisms because, in most cases, this information was not available. It is likely that machine learning algorithms could leverage mechanistic information to further improve performance, and this represents a promising avenue for future research. Another limitation is that SQUIRLS was trained on relatively common classes of noncanonical SAVs and may not be able to correctly classify rarer classes of variants such as deep intronic SAVs, multinucleotide SAVs, or variants affecting exonic splicing enhancers.

The UK 100,000 Genomes project and many other initiatives are poised to make genomic medicine part of healthcare for individuals with rare and common disease. In order to maximize the diagnostic yield of these programs, speed, efficiency, and ease of use are critical for technical incorporation of an algorithm into the diagnostic pipeline. However, it is also crucial that the output of the algorithm is easily interpretable by the clinical scientists receiving the results of this pipeline in order that they can apply their findings to the treatment of the affected individual. In this work, we have presented an accurate and interpretable algorithmic approach for analyzing non-canonical splice variants that to date have been difficult to assess in exome or genome data. SQUIRLS combines state-of-the-art accuracy with the ability to analyze arbitrary variants. On typical mid-range consumer hardware, SQUIRLS can analyze an exome file within a minute. To our knowledge, SQUIRLS is currently the only software that combines these abilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thomas D. Schneider for comments on the preprint that greatly improved the manuscript. This work was supported by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program Solve-RD. The Solve-RD project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 779257. Additional funding was provided by Monarch R24 (2R24OD011883-05A1), by NICHD (1R01HD103805-01), by the National Scholarship Program of the Slovak Republic, and by the transition grant “UNIMI partenariat H2020” (PSR2015-1720GVALE_01).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 20, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.06.014.

Data and code availability

SQUIRLS source code and pre-compiled release files are freely available for academic use on GitHub (see web resources). Links to the database files required for running SQUIRLS are available in the setup section of the online manual. The dataset of the splice variants used for training and evaluation of SQUIRLS is available in the online supplement.

Web resources

OMIM, https://www.omim.org/

SpliceAI, https://github.com/Illumina/SpliceAI

SQUIRLS download, https://github.com/TheJacksonLaboratory/Squirls/releases

SQUIRLS manual, https://squirls.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

SQUIRLS source code, https://github.com/TheJacksonLaboratory/Squirls

Supplemental information

References

- 1.de Ligt J., Willemsen M.H., van Bon B.W.M., Kleefstra T., Yntema H.G., Kroes T., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T., Koolen D.A., de Vries P., Gilissen C. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1921–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y., Muzny D.M., Reid J.G., Bainbridge M.N., Willis A., Ward P.A., Braxton A., Beuten J., Xia F., Niu Z. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1502–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y., Muzny D.M., Xia F., Niu Z., Person R., Ding Y., Ward P., Braxton A., Wang M., Buhay C. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312:1870–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lionel A.C., Costain G., Monfared N., Walker S., Reuter M.S., Hosseini S.M., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Merico D., Jobling R., Nalpathamkalam T. Improved diagnostic yield compared with targeted gene sequencing panels suggests a role for whole-genome sequencing as a first-tier genetic test. Genet. Med. 2018;20:435–443. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan T.Y., Dillon O.J., Stark Z., Schofield D., Alam K., Shrestha R., Chong B., Phelan D., Brett G.R., Creed E. Diagnostic Impact and Cost-effectiveness of Whole-Exome Sequencing for Ambulant Children With Suspected Monogenic Conditions. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:855–862. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadei S., Gulsuner S., Shirts B.H., Mandell J.B., Kortbawi H.M., Norquist B.S., Swisher E.M., Lee M.K., Goldberg Y., O’Connor R. Characterization of splice-altering mutations in inherited predisposition to cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:26798–26807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915608116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawczak M., Reiss J., Cooper D.N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum. Genet. 1992;90:41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teraoka S.N., Telatar M., Becker-Catania S., Liang T., Onengüt S., Tolun A., Chessa L., Sanal O., Bernatowska E., Gatti R.A., Concannon P. Splicing defects in the ataxia-telangiectasia gene, ATM: underlying mutations and consequences. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:1617–1631. doi: 10.1086/302418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ars E., Serra E., García J., Kruyer H., Gaona A., Lázaro C., Estivill X. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing are the most common molecular defects in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:237–247. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddirevula S., Kuwahara H., Ewida N., Shamseldin H.E., Patel N., Alzahrani F., AlSheddi T., AlObeid E., Alenazi M., Alsaif H.S. Analysis of transcript-deleterious variants in Mendelian disorders: implications for RNA-based diagnostics. Genome Biol. 2020;21:145. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H., Huang A.Y., Wang L.-K., Yoon A.J., Renteria G., Eskin A., Signer R.H., Dorrani N., Nieves-Rodriguez S., Wan J. Diagnostic utility of transcriptome sequencing for rare Mendelian diseases. Genet. Med. 2020;22:490–499. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0672-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings B.B., Marshall J.L., Tukiainen T., Lek M., Donkervoort S., Foley A.R., Bolduc V., Waddell L.B., Sandaradura S.A., O’Grady G.L., Genotype-Tissue Expression Consortium Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonorazky H.D., Naumenko S., Ramani A.K., Nelakuditi V., Mashouri P., Wang P., Kao D., Ohri K., Viththiyapaskaran S., Tarnopolsky M.A. Expanding the Boundaries of RNA Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool for Rare Mendelian Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:466–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soemedi R., Cygan K.J., Rhine C.L., Wang J., Bulacan C., Yang J., Bayrak-Toydemir P., McDonald J., Fairbrother W.G. Pathogenic variants that alter protein code often disrupt splicing. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:848–855. doi: 10.1038/ng.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagadeesh K.A., Paggi J.M., Ye J.S., Stenson P.D., Cooper D.N., Bernstein J.A., Bejerano G. S-CAP extends pathogenicity prediction to genetic variants that affect RNA splicing. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:755–763. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu K.-H., Beam A.L., Kohane I.S. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2:719–731. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caminsky N., Mucaki E.J., Rogan P.K. Interpretation of mRNA splicing mutations in genetic disease: review of the literature and guidelines for information-theoretical analysis. F1000Res. 2014;3:282. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5654.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wimmer K., Schamschula E., Wernstedt A., Traunfellner P., Amberger A., Zschocke J., Kroisel P., Chen Y., Callens T., Messiaen L. AG-exclusion zone revisited: Lessons to learn from 91 intronic NF1 3¢ splice site mutations outside the canonical AG-dinucleotides. Hum. Mutat. 2020;41:1145–1156. doi: 10.1002/humu.24005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., Sunyaev S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013;Chapter 7 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. Unit7.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houdayer C., Caux-Moncoutier V., Krieger S., Barrois M., Bonnet F., Bourdon V., Bronner M., Buisson M., Coulet F., Gaildrat P. Guidelines for splicing analysis in molecular diagnosis derived from a set of 327 combined in silico/in vitro studies on BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:1228–1238. doi: 10.1002/humu.22101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogan P.K., Faux B.M., Schneider T.D. Information analysis of human splice site mutations. Hum. Mutat. 1998;12:153–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:3<153::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeo G., Burge C.B. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J. Comput. Biol. 2004;11:377–394. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cygan K.J., Sanford C.H., Fairbrother W.G. Spliceman2: a computational web server that predicts defects in pre-mRNA splicing. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2943–2945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desmet F.-O., Hamroun D., Lalande M., Collod-Béroud G., Claustres M., Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leman R., Gaildrat P., Le Gac G., Ka C., Fichou Y., Audrezet M.-P., Caux-Moncoutier V., Caputo S.M., Boutry-Kryza N., Léone M. Novel diagnostic tool for prediction of variant spliceogenicity derived from a set of 395 combined in silico/in vitro studies: an international collaborative effort. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:1600–1601. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jian X., Boerwinkle E., Liu X. In silico prediction of splice-altering single nucleotide variants in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:13534–13544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowlands C.F., Baralle D., Ellingford J.M. Machine Learning Approaches for the Prioritization of Genomic Variants Impacting Pre-mRNA Splicing. Cells. 2019;8:8. doi: 10.3390/cells8121513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mort M., Sterne-Weiler T., Li B., Ball E.V., Cooper D.N., Radivojac P., Sanford J.R., Mooney S.D. MutPred Splice: machine learning-based prediction of exonic variants that disrupt splicing. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naito T. Predicting the impact of single nucleotide variants on splicing via sequence-based deep neural networks and genomic features. Hum. Mutat. 2019;40:1261–1269. doi: 10.1002/humu.23794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaganathan K., Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S., McRae J.F., Darbandi S.F., Knowles D., Li Y.I., Kosmicki J.A., Arbelaez J., Cui W., Schwartz G.B. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell. 2019;176:535–548.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G.R., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider T.D. Theory of molecular machines. II. Energy dissipation from molecular machines. J. Theor. Biol. 1991;148:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soukarieh O., Gaildrat P., Hamieh M., Drouet A., Baert-Desurmont S., Frébourg T., Tosi M., Martins A. Exonic Splicing Mutations Are More Prevalent than Currently Estimated and Can Be Predicted by Using In Silico Tools. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke S., Anquetil V., Zamalloa J.R., Maity A., Yang A., Arias M.A., Kalachikov S., Russo J.J., Ju J., Chasin L.A. Saturation mutagenesis reveals manifold determinants of exon definition. Genome Res. 2018;28:11–24. doi: 10.1101/gr.219683.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubisz M.J., Pollard K.S., Siepel A. PHAST and RPHAST: phylogenetic analysis with space/time models. Brief. Bioinform. 2011;12:41–51. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ke S., Shang S., Kalachikov S.M., Morozova I., Yu L., Russo J.J., Ju J., Chasin L.A. Quantitative evaluation of all hexamers as exonic splicing elements. Genome Res. 2011;21:1360–1374. doi: 10.1101/gr.119628.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider T.D. Sequence logos, machine/channel capacity, Maxwell’s demon, and molecular computers: a review of the theory of molecular machines. Nanotechnology. 1994;5:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider T.D. Information content of individual genetic sequences. J. Theor. Biol. 1997;189:427–441. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caron B., Luo Y., Rausell A. NCBoost classifies pathogenic non-coding variants in Mendelian diseases through supervised learning on purifying selection signals in humans. Genome Biol. 2019;20:32. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1634-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou J., Troyanskaya O.G. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning-based sequence model. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:931–934. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrini A., Mesiti M., Schubach M., Frasca M., Danis D., Re M., Grossi G., Cappelletti L., Castrignanò T., Robinson P.N., Valentini G. parSMURF, a high-performance computing tool for the genome-wide detection of pathogenic variants. Gigascience. 2020;9:9. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giaa052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedregosa F. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kircher M., Witten D.M., Jain P., O’Roak B.J., Cooper G.M., Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohno K., Tsujino A., Shen X.-M., Milone M., Engel A.G. Spectrum of splicing errors caused by CHRNE mutations affecting introns and intron/exon boundaries. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:e53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.026682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Celebi J.T., Wanner M., Ping X.L., Zhang H., Peacocke M. Association of splicing defects in PTEN leading to exon skipping or partial intron retention in Cowden syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2000;107:234–238. doi: 10.1007/s004390000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergstra J., Bengio Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012;13:281–305. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanamori M., Kon H., Nobukuni T., Nomura S., Sugano K., Mashiyama S., Kumabe T., Yoshimoto T., Meuth M., Sekiya T., Murakami Y. Microsatellite instability and the PTEN1 gene mutation in a subset of early onset gliomas carrying germline mutation or promoter methylation of the hMLH1 gene. Oncogene. 2000;19:1564–1571. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smedley D., Robinson P.N. Phenotype-driven strategies for exome prioritization of human Mendelian disease genes. Genome Med. 2015;7:81. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson P.N., Köhler S., Oellrich A., Wang K., Mungall C.J., Lewis S.E., Washington N., Bauer S., Seelow D., Krawitz P., Sanger Mouse Genetics Project Improved exome prioritization of disease genes through cross-species phenotype comparison. Genome Res. 2014;24:340–348. doi: 10.1101/gr.160325.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smedley D., Jacobsen J.O.B., Jäger M., Köhler S., Holtgrewe M., Schubach M., Siragusa E., Zemojtel T., Buske O.J., Washington N.L. Next-generation diagnostics and disease-gene discovery with the Exomiser. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:2004–2015. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X., Wu C., Li C., Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v3.0: A One-Stop Database of Functional Predictions and Annotations for Human Nonsynonymous and Splice-Site SNVs. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:235–241. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

SQUIRLS source code and pre-compiled release files are freely available for academic use on GitHub (see web resources). Links to the database files required for running SQUIRLS are available in the setup section of the online manual. The dataset of the splice variants used for training and evaluation of SQUIRLS is available in the online supplement.