Abstract

Background:

We assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a collaborative shared care (CSC) model for psychosis delivered by traditional and faith healers (TFH) and primary health care providers (PHCW).

Methods:

Cluster-randomized trial in Kumasi, Ghana and Ibadan, Nigeria. Clusters, each consisting of a primary care clinic and neighbouring TFH facilities, were stratified by size and country and randomly allocated (1:1) to either intervention group in which a manualised CSC was delivered by TFH and PHCW or control group with enhanced care as usual (eCAU). Participants were adults (aged ≥18 years) on admission in TFH facilities with active psychotic symptoms (Positive and Negative Schizophrenia Syndrome (PANSS) score ≥ 60). Blinded primary outcome assessments with PANSS and of costs were conducted at 6 months and at individual level. Trial registration number: ID:NCT02895269

Findings:

51 clusters were randomly allocated (26 intervention, 25 control). 307 patients (166[54%] in the intervention group and 141[47%] in the control group) were enrolled between September 1, 2016 and May 3, 2017; 190(62%) were male. Baseline mean PANSS score was 107.3 (SD17.5) for CSC group and 108.9 (SD18.3) for eCAU group. 286 (93%) completed the 6-month follow-up at which the mean total PANSS score for CSC group was 53.4 (SD19.9), significantly lower than 67.6 (SD 23.3) for eCAU control group (adjusted mean difference −15.01 (95%CI −21.17to−8.84; p<0.0001). Mean PANSS negative, positive and general psychopathology sub-scale scores were also all significantly lower for CSC participants. CSC led to greater reductions in overall care costs. Mild extrapyramidal side effects were experienced by 5 CSC participants.

Interpretation:

Findings indicate that a collaborative shared care delivered by TFH and conventional health providers for persons with psychosis is effective and cost-effective. The model of care offers the prospect of scaling up improved care to this vulnerable population in settings with low resources.

Funding:

National Institute of Mental Health.

INTRODUCTION

With schizophrenia alone being responsible for about 7% of Years Lived with Disability, psychotic disorders are a major cause of disability as well of considerable burden to families and caregivers globally1. In many low-and-middle-income countries as well as in poorly-resourced parts of high-income countries, many people with psychotic disorders receive healthcare from complementary alternative health providers, including traditional and faith healers (TFH)2–4. In much of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), factors such as scarcity of mental health specialists, nearness to the community, and shared belief about the causes and treatment of psychosis make TFH the preferred sources of care5–8. These realities have often led to calls for the integration of traditional healers into mainstream health services9, with several countries including the idea of integration in their national policies.

While there is interest in integration9, which implies the inclusion of TFH in the formal health system, a more cautious program of collaboration has been suggested to be tested for its feasibility and effectiveness in promoting better outcomes for patients2. One of the main reasons for that caution is the concern that some TFH use treatment approaches that are potentially harmful or that verge on human rights infringements of vulnerable patients with serious mental disorders, such as shacking, use of untested or unknown concoctions, and forced prolonged fasting10,11, even though some of such practices also sometimes occur in institutional care.

While there is some evidence that a collaborative care program with TFH can be feasible, especially in the care of persons with HIV12,13, no previous study has examined the clinical effectiveness of such a program for severe mental health conditions. In a series of formative studies, we had systematically explored strategies that might promote trust and facilitate collaboration between healers and formal healthcare providers14,15, This trial, COllaborative Shared care to IMprove Psychosis Outcome (COSIMPO), using cluster randomization to avoid contamination, aims to determine the effectiveness of such collaboration in improving the clinical outcome of persons with psychosis16. We hypothesised that a collaborative intervention delivered by TFH and conventional primary health care providers would be more effective and cost-effective than care as usual for persons with psychotic disorders. Typically, TFH do not engage with biomedical health providers in their usual or routine practice.

METHOD

Study Setting

A full description of the setting and methods of the study has been published16. COSIMPO is a single-blind, cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in the 11 local government areas (LGAs) in and around the city of Ibadan in Nigeria and in the Ashanti region of Ghana. Following a mapping of all facilities run by TFH providing mental health services as well as all the public primary health care clinics in the two locations, a sampling frame of service clusters was constructed. A cluster consisted of one primary care clinic (PHC) and all the TFH facilities in the catchment area served by the PHC. A cluster was thus composed of one PHC and between one and five TFH facilities, Across the two sites, a total of 71 clusters were formed following this procedure (37 in Ghana and 34 in Nigeria).

In the setting of COSIMPO, Ghana and Nigeria, traditional healers comprise herbalists (those who use plant products for medicinal purposes) or diviners (those who claim to gain insight for healing by occultic or ritualistic processes). Faith healers are those who subscribed to Christian or Islamic faith and rely on prayers and religious rituals, including divination and sacrifices to provide healing. In practice, an eclectic approach in which both herbs and divination are used as treatment modalities is common between the three groups. In both settings, healers provide care for the majority of persons with psychotic disorders17 and most healers who treat mental disorders, offer in-patient services. Primary health care workers (PHCW) consisted of registered nurses, clinical officers, community health officers, or community health extension workers. In Ghana, a few PHCs have Community Psychiatric Nurses. In both settings, referrals from PHCs can be made to other levels of care such as a general hospital staffed by general physicians or to specialists when available.

Randomization and masking

The unit of randomization were eligible and consenting clusters consisting of one PHC and a group of TFH facilities, while the unit of analysis was individual participants. A cluster was eligible if it had at least one TFH facility with active inpatient service and a PHC with full complement of staff to permit the participation of two PHCW in the trial. Participating clusters were stratified by country and randomly allocated to deliver collaborative shared care (CSC) or enhanced care as usual (eCAU). Allocation to the two arms was balanced by site (Ghana versus Nigeria) and by size of the cluster, using the total number of admission beds in each cluster (small versus large). Following the mapping exercise of the facilities and the composition of the clusters, anonymized codes for each cluster were provided by the research team to the statistician, with no other involvement in the implementation of the trial, who generated the allocation sequence and carried out the random allocation.

Enrolment Procedure

All patients were recruited into the trial at the TFH facilities where they were on admission for treatment of psychosis. The trained research assistants (RAs), all college educated, came to know about potential participants either during the RAs routine visits to the facilities or following calls from the TFH to the study team about the presence of potential participants. All patients who were on admission at TFH facilities during recruitment were deemed potentially eligible and were approached by the RAs and, if they provided consent to be screened, were assessed for eligibility. Eligible patients were those aged 18 years or over, fluent in the study language of Yoruba (Nigeria) or Twi (Ghana), with a confirmed diagnosis of non-organic psychosis as assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version IV (SCID)18, and who were actively symptomatic at the time of recruitment as indicated by a minimum score of 60 on the total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scale19. Designed as a pragmatic trial, only few exclusion criteria were used. Eligible subjects were not pregnant, did not have a serious physical illness in need of urgent medical attention, were not severely cognitively impaired and gave verbal commitment to being available for the 6-month outcome assessment. As detailed in the protocol16, a strict consenting procedure, including prior assessment by an independent social worker of capacity to consent, was followed to obtain participants’ as well as primary caregivers’ consents. Baseline assessments of participants who consented were conducted within 3 days of enrolment. Outcome assessments conducted at 3 months were not blinded, while those conducted at 6 months following trial entry were fully blinded.

The trial was approved by the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital Ethics Committee (UI/EC/12/0219) and the Ethics Committee of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (CHRPE/AP/512/16). It was also approved and monitored by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health Data Safety and Monitoring Board, an independent oversight body established by the funder.

INTERVENTIONS

Intervention Arm

The intervention involved the working together of TFH and PHCW to provide care for persons with psychotic disorders who were admitted to the facilities of the TFH. In each cluster, two PHCW were engaged in the collaborative care model (as described later). The PHCW made two types of visits to the TFH facilities in their cluster: scheduled visits conducted at least weekly and unscheduled visits initiated by the TFH and conducted in response to urgent requests for assistance in the management of the trial participants. Such requests might be for acute deterioration in trial participants mental status, including risks of violence, self-harm or of absconding or emergent or worsening physical illness.

As described in the protocol and specified in a detailed intervention manual, there were two main components in the Collaborative Shared Care (CSC): 1. Clinical support to respond to the medical needs of psychotic patients. Commonly, this often meant the administration of medication to manage psychotic symptoms, especially in response to acute psychotic disturbance, or medication for emergent physical illnesses, such as infections or injuries. 2) Clinical support to improve service on a continuous basis. This consisted of engagement and interactions with the TFH, the patient, and the caregivers of the patient. During the regular weekly visits, the PHCW provided information on best clinical practice (reinforcing the message provided to the TFH during training prior to trial commencement, especially on how to avoid the use of potentially harmful treatment practices), provided information on patient rehabilitation, and attended to any other clinical issues raised by TFH. The PHCW also provided psychoeducation to both patients and any available relative during such visits. All inputs from the PHCW were in addition to the treatments routinely provided by the healers, including herbal, ritual, and psychosocial interventions.

In this CSC arrangement, medication could only be prescribed by the PHCW. If a patient required a prescription of a psychotropic medication, the PHCW would take into account any herbs prescribed for the patient by the TFH and monitor closely for any side effects. Chlorpromazine, which the PHCWs are authorised to prescribe, was the antipsychotic of first choice and this was made freely available by the project. In Ghana, primary care providers also had access to and were able to prescribe olanzapine. PHCW at each site were supervised by the psychiatrists in the research teams and were consulted on as-needed basis using closed-user-group mobile telephony. The PHCW could also refer a trial participant to a health facility, as necessary, but always following consultation with the TFH.

As described in full in the protocol, the PHCW in the intervention arm received a manualised, 3-day interactive training on the medical management of psychosis while the TFH were trained over 2 days about how to avoid the use of harmful treatment practices, among other topics. Both were trained on the modalities for implementing the CSC including expectations, roles, and possible barriers and facilitatory factors for effective collaboration.

Control arm

Participants in the control arm received enhanced care as usual (eCAU). Since the participants were all on admission at TFH facilities, usual care consisted of the usual treatment provided by the TFH, which varied according to the healer’s orientation. Typically, this consisted of combinations of herbs, rituals, prayer, fasting and divination. As indicated earlier, eclectic approaches are common and so is the use of shacking to restrain acutely disturbed patients and scarification to drain away “bad” blood.

Usual care meant that no formal collaboration was fostered between the TFH and PHCW in this arm. Nevertheless, care as usual was enhanced through the separate training of both the TFH and PHCW in this arm. In particular, and as requested by our Ethics Committees, detailed discussions were held with the TFH in the control arm about ways to reduce inhumane and potentially harmful treatment practices. While the PHCW had a 2-day session, the TFH were invited for a 1-day interactive session. The contents of the workshops were essentially similar to those for the CSC groups except that topics dealing with the features and modality of CSC were not included. The goal of the trainings was to reduce potential harm to patients who were nonetheless still receiving care as usual.

OUTCOMES

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome, assessed at 6 months following enrolment into the trial, was the difference in psychotic symptom improvement (or reduction in symptoms) as measured with the PANSS. Similar to previous observations in the setting of our study20, both the internal reliability of PANSS, using screening data of the total trial sample, (N=307; Cronbach’s alpha, 0.82) and the inter-rater reliability, from the independent ratings of 10 patients by 4 assessors (intraclass correlation, 0.99) were excellent. Secondary outcomes measured at 3 and 6 months included: disability (using the WHO Disability Assessment Scale 2.0)21, experience of self-stigma (using the 29-item Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness)22, exposure to harmful treatment practices (such as shackling, scarification, prolonged fasting) and to victimization by relatives, friends or neighbours (such as verbal, physical or sexual abuse, financial exploitation, or neglect) both of which were assessed using locally designed tools as described in the protocol. An overall blind assessment of the course of illness (using the Life Chart Schedule23) including duration of admission, symptom course, work performance and residence was also conducted at 6 months.

We also collected information on other serious adverse events (including serious medical emergency, serious suicidal behavior, and death).

All outcome assessments were conducted via face-to-face interviews using either the Yoruba (in Nigeria) or Twi (in Ghana) versions of the different instruments, derived by standard protocols of iterative back-translation that take account of language and cultural nuances. The 6-month primary outcome assessment was conducted in Nigeria by senior trainee psychiatrists and a mix of senior trainee psychiatrists and pre-doctoral psychology graduates in Ghana. These assessors had no role in patient recruitment and the assessments were conducted blind to patient arm allocation and mostly in patients’ homes or, in a few instances, at the TFH facilities. These assessors were trained at each site over 3 days by OG and VM.

Costs measures

To assess the cost-effectiveness of CSC compared to eCAU over the period of the trial, we administered to all participants an adapted version of the Service Utilization Questionnaire (SUQ)24 to capture the range of health-related services consumed by service users over the preceding two months (including the care received from TFHs and services delivered by PHCWs and other conventional health providers) as well as any out-of-pocket health care spending for consultations, medicaments and other related costs. The adaptation enabled us to collect data on use of herbs and drugs as well as those incurred on rituals and sacrifices. Also included are the costs of training PHCWs and TFH as well as of incentives to the former (see Online Table 1). We used simplified costing templates and local data inputs to generate a set of unit costs and prices for inpatient and outpatient service use provided and paid for by government or non-state actors; for health services or goods paid for privately by individuals or households we used the monetary amounts reported in the SUQ. Multiplication of unit costs or prices with reported levels of service utilisation enabled us to compute health service costs per trial participants both for the 3-month periods leading to the baseline and to the follow-up assessment at 3 and 6 months. All costs were collected in the local currency units of the two participating countries and were subsequently converted into US$ dollars for the year 2017/8 using the mean official exchange rate for the period.

Sample Size

Using data from a previous naturalistic follow-up study of persons with psychosis undergoing treatment conducted by our team25, we estimated that a mean difference of 7 points on the total PANSS outcome scores between the two arms would represent a clinically significant difference. As detailed in the protocol16, we estimated an intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 based on other studies and we estimated a loss of 20% of participants for the primary analysis. The estimated uninflated sample size required was 112 participants per arm, with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05. With a target of 6 participants per cluster and a design effect of 1.10, the total number required for analysis was 246. We therefore aimed to recruit a total of 296 from 49 clusters. Since 51 clusters were eligible and agreed to participate in the trial, we decided to include them all.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed in accordance with CONSORT guidelines26, with between group comparisons analysed by intention to treat. All analyses were conducted for the total sample, pooled across both country sites and focussed primarily on baseline and the blindly collected 6-month outcome data. Descriptive statistics were used to compare the characteristics of participants across arms at baseline. The 6-month follow-up rate was high (93%), and therefore no imputation of missing data was made and the analyses also disregarded adherence to the intervention or withdrawal from the trial. We present unadjusted as well as adjusted estimates. For continuous outcomes with normally distributed residuals, the intervention effect was estimated as the difference in mean scores between CSC and eCAU using random effects linear regression, adjusted for sex, marital status baseline PANSS score, country as well as cluster. The effect sizes are reported as standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. Random-effects logistic regression is used to analyze binary outcomes with the effect sizes reported as relative risks estimated using the marginal standardization technique with 95% confidence intervals of the ratios estimated by the delta method. In both analyses, cluster and country site were accounted for, with the clustering variable included as random effect. For a higher standard of evidence, we set our statistical significance level as p< 0.005.27

For every service, input and time loss, mean 3-month costs were computed at baseline, 3-month and 6-month follow-ups as well as for the entire 6 months of follow-up. For cost-effectiveness analysis, mean costs were computed for each trial arm and these were then linked to the change from baseline of the clinical measure (PANSS total score) as well as functioning (WHO-DAS summary scores) at 3-and 6-month outcome points. Owing to the non-normal distribution of mean service costs per study participant, the 95% confidence intervals around cost and cost-effectiveness estimates were derived using non-parametric bootstrapping techniques (1000 resamples were run). All analyses were conducted using the STATA (version 15.0) software.

This trial was registered with the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trial registry, ID: NCT02895269.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author has full access to all data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

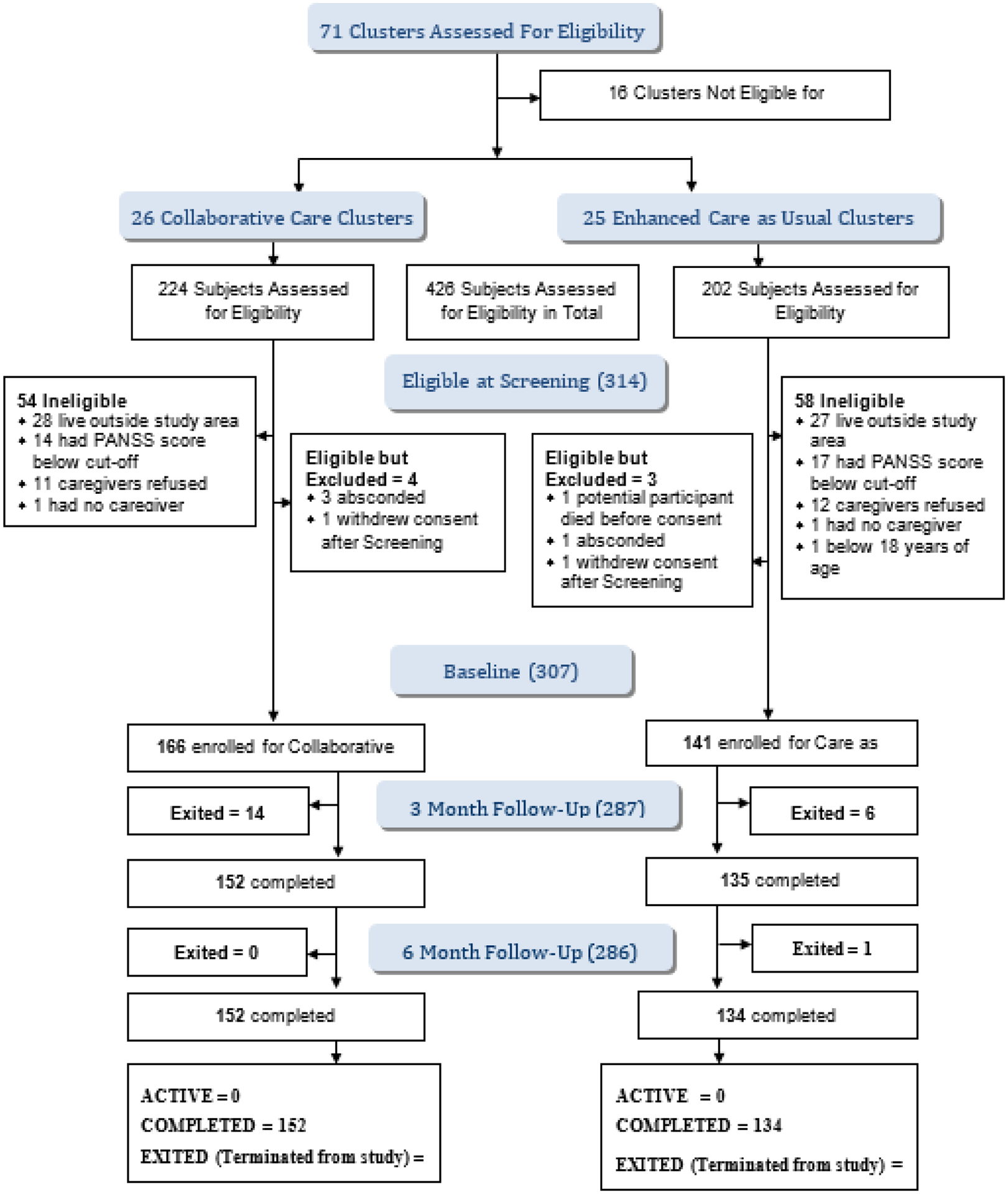

Of 71 clusters assessed, 16 were found ineligible and 4 had PHCs that declined to participate. The 16 ineligible clusters either had TFH that were no longer active (10) or had PHC with inadequate manpower to guarantee the participation of at least two PHCW in the collaborative activities (6). The remaining 51 eligible clusters, where all the TFH and PHCW provided consent, were randomized to the two arms of the study (Figure 1). Recruitment into the trial commenced on 01 September 2016 and ended on 03 May 2017. The last 6-month outcome assessment was conducted on 03 October 2017. Figure 1 shows the recruitment details. Follow-up at 6 months was completed for 152 (91.6%) subjects in the intervention arm and for 134(95%) subjects in the control arm. The 14(8.4%) subjects in the intervention arm and the 7(5%) subjects in the control for whom primary outcome data was not collected exited the trial before completion, with 20 of the 21(95.2%) doing so before the 3-month outcome assessments.

Figure 1:

COSIMPO Flow chart

The groups were similar in demographic and clinical features at baseline except for higher proportions of males (p=0.051 and those who had never been married (p<0.05) in the CSC group (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics (N=307)

| Characteristics | Intervention Arm (N=166) | Control Arm (N=141) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | ||

| Male | 111(66.9) | 79(56.0) |

| Female | 55(33.1) | 62(44.0) |

| Religion, N (%) | ||

| Christianity | 101(60.8) | 89(63.1) |

| Islam | 64(38.6) | 52(36.9) |

| Traditional | 1(0.6) | - |

| Marital status, N (%) | ||

| Single | 110(66.3) | 73(51.8) |

| Married | 31(18.7) | 32(22.7) |

| Divorced | 10(6.0) | 17(12.1) |

| Separated/widowed | 15(9.0) | 19(13.5) |

| Employment Status | ||

| Unemployed | 120 (72.3) | 106 (75.2) |

| Housewife | 6 (3.6) | 2 (1.4) |

| Unskilled laborer | 14 (8.4) | 15 (10.6) |

| Skilled laborer | 19 (11.4) | 13 (9.2) |

| Middle-level worker | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.7) |

| Professional | 4 (2.4) | 4 (2.8) |

| Type of Psychosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 136(82.4) | 122(87.1) |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 13(7.9) | 7(5.0) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 9(5.5) | 6(4.3) |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 7(4.2) | 5(3.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) years | 33.2(12.1) | 33.4(10.2) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 9.6(3.8) | 9.3(3.6) |

| Total PANSS score, mean(SD) | 107.3 (17.5) | 108.9 (18.3) |

| Total WHO-DAS score, mean(SD) | 94.7 (29.5) | 91.5 (28.7) |

| Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), mean (SD) | 36.8(11.2) | 35.6(10.1) |

| Total ISMI score, mean (SD) | 2..4 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) |

PANSS is Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, scores range from 30 (best) to 210 (worst); WHODAS=WHO disability assessment schedule., scores range from 0 (best) to 144 (worst); GAS is Global Assessment of Functioning, scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best); ISMI is Internalized Stigma of Mental Disorders, mean scores range from 1(best) to 4 (worst). *Employment statuses were defined as follows: unemployed=not currently in paid employment; housewife=woman who is a homemaker and not seeking employment outside the home; unskilled labourer=worker who has not learnt any trade; skilled labourer=artisan; middle-level worker=clerical or secretarial staff, junior admin worker, etc; professional=teacher, nurse, doctor, senior admin staff,

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Trial participants in the CSC arm achieved a significantly better primary outcomes at 6 months than controls (PANSS total mean score 53.4(sd 19.9) vs. 67.6(sd 23.3; adjusted mean difference: −15.01 (95%CI −21.17 to −8.84; p< 0.0001) (Table 2; Online Table 1). The better improvement was seen in the three sub-scales of PANSS.

Table 2:

Outcomes at 6months

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Arm (N=152) | Control Arm (N=134) | Unadjusted mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI)* | p-value** | |

| PANSS scales, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Positive scale | 14.6(7.6) | 19.3(7.8) | −5.23(−7.48, −2.98) | 0.0001 | −4.85(−7.01, −2.70) | 0.0001 |

| Negative scale | 12.9(6.0) | 15.8(6.8) | −3.27(−5.15, −1.39) | 0.001 | −3.16(−5.00, −1.31) | 0.001 |

| General Psychopathology scale | 25.9(9.0) | 32.4(11.3) | −7.03(−9.97, −4.10) | 0.0001 | −6.75(−9.54, −3.97) | 0.0001 |

| Total score | 53.4(19.9) | 67.6(23.3) | −15.70(−22.18, −9.22) | 0.0001 | −15.01(−21.17, −8.84) | 0.0001 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

| ISMI scales, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Alienation | 1.9(08) | 2.2(0.8) | −0.2(−0.5, 0.0) | 0.053 | −0.3(−0.4, −0.1) | 0.009 |

| Stereotype endorsement | 2.0(0.7) | 2.1(0.7) | −0.2(−0.4, 0.1) | 0.199 | −0.2(−0.4, 0.0) | 0.059 |

| Discrimination experience | 1.9(0.7) | 2.1(0.9) | −0.2(−0.5, 0.1) | 0.268 | −0.2(−0.4, 0.0) | 0.014 |

| Social withdrawal | 1.9(0.7) | 2.0(0.8) | −0.1(−0.3, 0.1) | 0.323 | −0.1(−0.3, 0.0) | 0.090 |

| Stigma resistance | 2.2(0.7) | 2.2(0.7) | −0.0(−0.3, 0.2) | 0.745 | 0.0(−0.1, 0.2) | 0.567 |

| Total score | 2.0(0.6) | 2.1(0.6) | −0.1(−0.4, 0.1) | 0.227 | −0.2(−0.3, 0.0) | 0.007 |

| WHODAS scales, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Cognition | 10.6(6.1) | 12.6(6.5) | −2.6(−4.7, −0.5) | 0.014 | −2.2(−3.8, −0.6) | 0.006 |

| Mobility | 6.8(3.1) | 7.5(3.8) | −0.9(−2.1, 0.3) | 0.131 | −0.9(−1.9, 0.1) | 0.065 |

| Self care | 5.5(2.9) | 6.4(3.3) | −1.3(−2.4, −0.2) | 0.022 | −1.0(−1.7, −0.3) | 0.005 |

| Getting along with people | 7.6(4.3) | 9.2(5.4) | −2.0(−3.7, −0.3) | 0.020 | −1.8(−3.2, −0.4) | 0.014 |

| Life activities(household) | 7.1(4.4) | 8.5(5.2) | −2.2(−3.9, −0.5) | 0.010 | −1.8(−3.0, −0.6) | 0.004 |

| Life activities(work) | 8.9(5.6) | 10.2(5.6) | −1.6(−4.3, 1.1) | 0.241 | −0.7(−2.9, 1.6) | 0.568 |

| Participation | 15.2(7.1) | 17.5(8.0) | −2.6(−4.8, −0.5) | 0.016 | −2.5(−4.3, −0.8) | 0.005 |

| Total score | 52.3(25.0) | 61.8(28.3) | −11.8(−20.3, − 3.3) | 0.006 | −10.5(−17.0, −4.0) | 0.001 |

| Course of illness and recovery | ||||||

| Months on admission, Mean(SD) | 3.7(2.1) | 4.4(1.9) | −0.7(−1.3, 0.0) | 0.064 | −0.7(−1.4, −0.1) | 0.029 |

| Course of illness, % rated ‘Not continuous’ | 93(61.2%) | 54(40.9%) | 2.3(1.3, 4.1) | 0.003 | 2.5(1.4, 4.8) | 0.003 |

| Engagement in work (including housekeeping) % rated ‘good/fair’ | 118(79.2%) | 77(57.9%) | 3.0(1.6, 5.5) | 0.001 | 3.3(1.7, 6.2) | 0.001 |

| Ever in independent living, % | 92 (60.5) | 57 (42.5) | 2.2 (1.0, 4.7) | 0.52 | 2.4 (1.1, 5.2) | 0.026 |

Adjusted by baseline total PANSS score, sex, marital status, country and PHCP. PHCP included as random effects;

Significant p value at < 0.005 levels are highlighted

PANSS, positive and negative symptoms scale; ISMI, internalized stigma of mental illness; WHODAS, WHO disability assessment scale.

Compared to eCAU, CSC produced better improvements in functioning (significantly lower scores on the WHO-DAS) and suggestive evidence for less experience of self-stigma (lower scores on the ISMI, Table 3). Assessment with the Life Chart Schedule showed that, compared to participants in the eCAU arm, participants who received CSC were 1) significantly more likely to have episodic rather than continuous illness, and 2) significantly more likely to be rated as good or fair in their engagement with work or housekeeping at follow-up. There was suggestive evidence for shorter duration of admission and higher likelihood of independent living following discharge in the CSC group.

Table 3:

Costs and cost effectiveness of collaborative shared care and enhanced care as usual interventions at 3 and 6-month follow-up assessment (all costs in USD 2017/8)

| 3 months follow-up point | 6 months follow-up point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERVICE COSTS | CSC | eCAU | Adjusted difference(95% C.I) | CSC | eCAU | Adjusted difference (95% C.I) |

| Total service cost over 3 months Mean(SE) | 283(20) | 175(13) | 108(63,155) | 148(13) | 111(10) | 37(1,69) |

| Change in cost since baseline Mean(SE) | 29(28) | −73(59) | 102(64) | −106(26) | −137(54) | 31(62) |

| Incremental cost effectiveness ratio(PANSS) * | 9(−0.5, 21) | 2(−6, 14) | ||||

| Incremental cost effectiveness ratio(WHODAS) * | 10(−0.3, 22) | 2(−5, 14) | ||||

| SERVICE & TIME COSTS | Intervention | Control | Adjusted difference (95% C.I) | Intervention | Control | Adjusted difference (95% C.I) |

| Total service and time cost over 3 months Mean(SE) | 382(44) | 240(17) | 142(61,247) | 247(26) | 292(105) | −45(−288,103) |

| Change in cost since baseline Mean(SE) | −43(61) | −185(81) | 142(101) | −178(43) | −133(130) | −45(137) |

| Incremental cost effectiveness ratio(PANSS) * | 13(−4, 32) | −4(−29, 15) | ||||

| Incremental cost effectiveness ratio(WHODAS) * | 14(−4, 36) | −4(−29, 18) | ||||

CSC, collaborative shared care; eCAU, enhanced care as usual; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; WHODAS, WHO disability assessment scale

Effectiveness measure expressed as the level of positive improvement between Intervention and Control (e.g. a relatively greater reduction in symptoms); therefore, a positive cost-effectiveness ratio refers to the mean additional 3-month cost required to obtain a unit of improved effect, while a negative ratio means that the intervention dominates (less costly but also more effective than control).

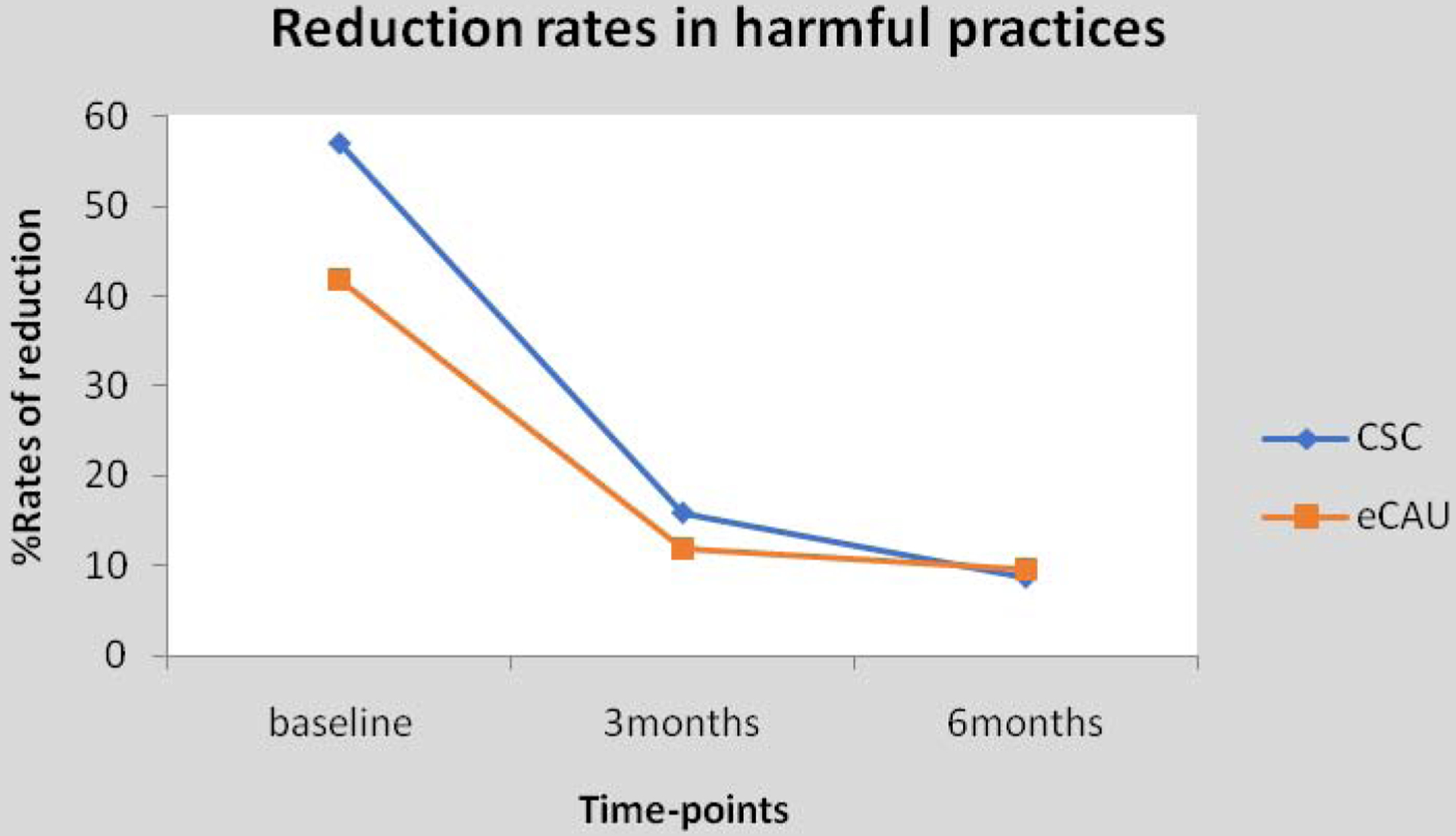

Participants in both trial arms had significant reductions in the experience of harmful treatment practices from baseline to the 6-month primary endpoint (Figure 2; Online Table 2) with no difference between the groups. The proportions of participants reporting experiencing victimization of any type over the 6-month trial period were also similar in the CSC and eCAU groups (8.6% vs. 9.7%; adjusted odds ratio 0.80; CI 0.3 – 2.4; p= 0.702)

Figure 2:

Experience of harmful practices in collaborative shared care and enhanced care as usual arms

CSC, collaborative shared care; eCAU, enhanced care as usual

Five participants, all in the CSC arm (3 in Ghana and 2 in Nigeria), were treated for extrapyramidal side effects, all of which resolved. One participant in the CSC arm in Ghana, aged 41 years, died of a stroke. This death was not deemed to be related to study procedure by the Ethics Committees as well as the NIMH DSMB.

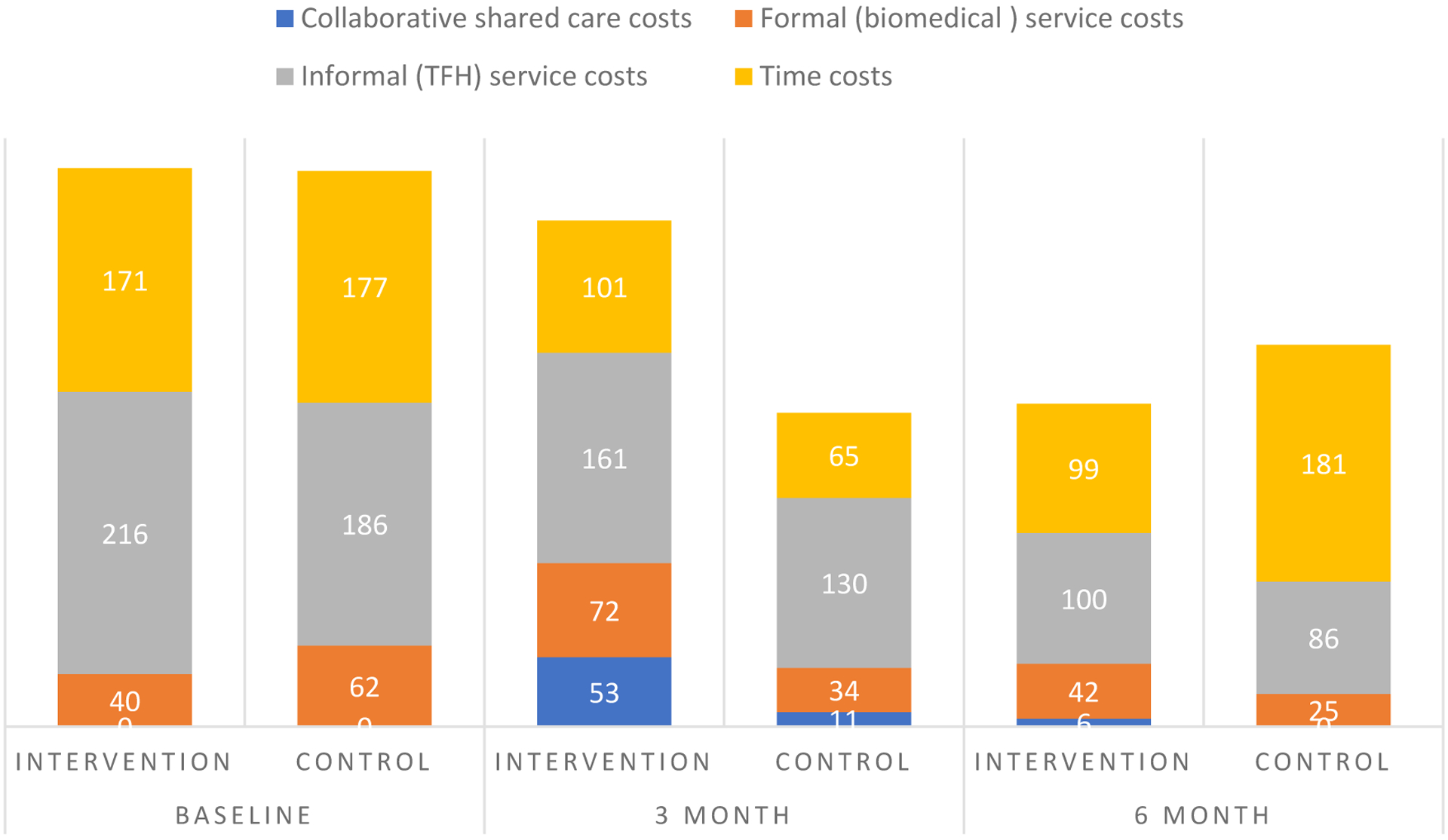

Cost and cost-effectiveness

Estimated quarterly service use and time costs per participant in the CSC group fell from US$ 425 for the three months prior to baseline to US$ 382 (at 3-month follow-up) and US$ 247 (at 6-month follow-up). Costs per participant in the eCAU group decreased from US$ 425 to 240 (at 3-month follow-up) but rose to US$ 292 (at 6month follow-up). Over the full 6-month period from baseline, the estimated total cost for the CSC group was US$ 627 while it was US$ 526 for the control group. Health service costs alone (without time costs) followed a broadly similar pattern. (Figure 3; Online Table 3).

Figure 3:

Breakdown of costs (US$ over 3 months) at baseline and follow-up assessments

Over the follow-up periods at 3 and 6 months, both symptom and functional status improvements were better in the CSC. However, while reduction in total service and time costs was greater in the CSC group at 6 months, the reverse was observed at 3 months (that is, costs reduced less in the CSC group than eCAU group). When only service costs were considered (time costs omitted), eCAU was also associated with a slightly greater cost reduction at both 3- and 6-month follow-up points. At 6-month follow-up, the total health service and time cost associated with a one-point improvement on the PANSS was US$ −4 (95% CI, −29 to 15) and US$ −4 (−29 to 18) with a one-point improvement on WHODAS in the CSC group (meaning that CSC was dominant, i.e. both more effective and less costly than control). When only health service costs were assessed, the cost associated with a one-point improvement on the PANSS at 6 months was US$ US$ 2(95% CI, −6 to 14) and US$ US$ 2(−5 to 14) for a one-point improvement on WHODAS in the CSC group. These findings indicate that at the primary outcome assessment CSC was a dominant intervention over eCAU for total (health service plus time) costs, while for service costs alone there is a marginal value of less than US$ 1 per month to pay for a unit improvement on both symptoms and functioning (Table 3; Online Figure showing cost-effectiveness scatter graphs).

Profile of treatment engagements by PHCW in the CSC arm

Across the two study sites, PHCW in the CSC arm made a total of 1480 scheduled and 54 unscheduled visits to TFH facilities during the trial. Of the 161 in the intervention arm, a total of 103(62%), 53 in Ghana and 50 in Nigeria, were prescribed oral medication while 28(16.9%), 22 in Ghana and 6 in Nigeria, were prescribed depot medication following reviews by specialists.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a program of collaboration between TFH and conventional health providers (in this case, primary health care providers) in the care of persons with psychotic disorders. Many previous studies have explored the practice and profile of traditional and faith healing as well as the views of the healers about collaboration with or integration into the conventional public health system2,28–30 but none has designed a package for such interventions or tested its effectiveness on patient outcomes. We found that patients in receipt of CSC had significantly better outcomes than those receiving eCAU. Better clinical improvements in the CSC arm were seen on each of the syndromes (positive, negative and general psychopathology) as well as overall. CSC participants also had significantly less disability, better course of illness and better adjustment to work. A suggestive trend for shorter admission and greater likelihood of independent living was also observed. CSC was also more cost-effective for total costs but marginally less so for health service costs only. In both arms, there was a similar but significant drop in the experience of harmful treatment practices.

Even though rigorously conducted trials of the practical implementation of collaboration between TFH and conventional providers are not available for comparison, our findings are in keeping with reports suggesting that healers might be willing to collaborate with conventional health providers31. It is of particular interest that this collaboration led not only to better symptom remission, but to improved overall functioning and self-appraisal as indicated by suggestive evidence for lower self-stigma. It is plausible to speculate that having less self-stigma might reflect the improvement in symptoms and functioning rather than better attitudes of those around the patients. In view of the strict ethical requirements we implemented, including the training and close monitoring of the practice of TFH in the eCAU arm, there was a significant reduction in the use of harmful treatment practices in both arms. What these findings showed is that healers can be trained and monitored to substantially reduce the use of such practices, a veritable barrier to the integration of their service into mainstream mental health care2. This observation contrasts with that of a previous study in which, apparently, no such training was provided32. Nevertheless, more work is required to understand what may promote or impede a rights-based service approach by TFH as well as their readiness to collaborate with biomedical service in routine practice.

The findings of this trial should be considered within its limitations. First, the participants were not told arm allocation but they could have guessed this and the assessments were based on self-reports. The possibility that the knowledge of the involvement of conventional providers in their care could have influenced the reporting of the outcomes by participants in the CSC arm cannot be excluded. However, primary 6-month outcome assessments were conducted by assessors blind to the intervention and who were meeting the trial participants for the first time thus reducing the tendency for desirability bias (i.e participants seeking to please the assessors). Second, the judgement about whether a psychotic episode was organic was based on history and physical signs, such as fever and recent head injuries, and not on laboratory investigations. Third, the 3-month assessments were not conducted blind and for this reason, we have not placed much emphasis on the findings at that outcome point. Forth, even though the trial was designed to be pragmatic, there were at least two inputs that are not available in routine patients care at the sites: the providers were given incentives to make the visits to the TFH facilities and medications were provided free for the purpose of the trial. In Nigeria, as opposed to Ghana, patients would have had to pay for these medications. Fifth, even though our cost estimates were comprehensive, we have not included the minimal costs of supervision, done mainly by mobile phone. Sixth, healers used eclectic treatment approaches which were not systematically studied in this trial. The possibility of significant differences between the arms in treatment approaches that may affect patient outcome cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, we have shown that collaboration between traditional and faith healers and conventional health providers in the care of persons with psychotic disorders is possible in these two sub-Saharan African countries and that such collaboration led to improved patient outcomes and led to greater reductions in overall care costs. We provide the first empirical evidence that collaboration may have the potential to expand evidence-based care to persons with psychosis, and possibly other health conditions, and that the practice of TFH can be made more humane and in observance of basic human rights.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed and PsychINFO from 25 September 2012 to 1 October 2014 for studies exploring the feasibility, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of collaboration between complementary alternative providers, specifically traditional and faith healers, and conventional health providers in the care of persons with psychosis. We imposed no language restrictions. Our search terms included “severe mental disorders”, “psychosis”, “traditional healers”, “faith healers”, “mental health providers”, “collaboration”, “integration”, and “low and middle-income countries”. We also hand searched reference lists of papers and books. Several sources provided information about the profile of patients in the care of traditional and faith healers, with evidence that persons with psychosis were commonly among the patient groups. There was also information about diagnostic and treatment approaches as well as observation that, even though the care provided often led to improvement in the clinical condition of the patients, some of the treatment practices were potentially harmful and not always in conformity with the human rights of patients. A need to develop approaches to facilitate collaboration between the healers and conventional providers was frequently emphasized even though there was also scepticism about whether collaboration could work given discordant views about the nature of psychopathology between healers and conventional providers. Other than collaborative efforts involving the engagement of traditional healers in the provision of care, specifically counselling, to persons with HIV, no systematic study had been conducted to test whether healers and conventional providers can collaborate in the care of persons with psychosis and no previous randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of collaboration between healers and providers has ever been conducted.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a collaborative shared care for psychosis delivered by traditional/faith healers and conventional primary care providers. Prespecified primary and secondary outcomes, assessed at 6 months following trial entry, included psychotic symptoms, disability, self-stigma, course of illness, duration of admission, quality of work performance, living condition, and the experience of harmful or inhumane treatments. Findings show that most outcomes were better with a model of care in which primary care providers worked collaboratively with traditional and faith healers to deliver care to persons with psychotic disorders compared to care as usual. CSC was successfully implemented between healers and conventional providers and was cost-effective.

Implications of all the available evidence

It is widely recognized that traditional and faith healers constitute an important group of mental health service workforce in low- and middle-income countries. Even though a need for collaboration between healers and conventional providers has been recognized and canvassed by many stakeholders, including by governments in these countries, no systematic assessment of the potential impact of such collaboration on patient care has ever been conducted. Our findings suggest that such collaboration can be designed and implemented and that collaboration has the potential for delivering effective and cost-effective care to the large population of persons in need of care for psychosis in low- and middle-income countries. More research is however needed to examine the factors that may be relevant for scaling up such collaborative shared care model into real-live routine service for persons with psychosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (5U19MH098718-05). The funder had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The corresponding author has full access to all data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest

We declare no conflicting of interests.

Contributor Information

Oye Gureje, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, Neurosciences and Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

John Appiah-Poku, Department of Behavioural Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Toyin Bello, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, Neurosciences and Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Lola Kola, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, Neurosciences and Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Ricardo Araya, Department of Health Services and Population Research, King’College London.

Dan Chisholm, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Oluyomi Esan, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, Neurosciences and Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Benjamin Harris, Department of Psychiatry, University of Liberia, Monrovia.

Victor Makanjuola, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, Neurosciences and Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Caleb Othieno, Department of Psychiatry, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

LeShawndra Price, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Bethesda, MD, USA.

Soraya Seedat, Department of Psychiatry, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2013; 382(9904): 1575–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gureje O, Nortje G, Makanjuola V, Oladeji BD, Seedat S, Jenkins R. The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in the treatment of mental health disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2(2): 168–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saeed K, Gater R, Hussain A, Mubbashar M. The prevalence, classification and treatment of mental disorders among attenders of native faith healers in rural Pakistan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2000; 35: 480–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst E Prevalence of use of complementary/alternative medicine: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organization 2000; 78(2): 252–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Watt ASJ, Nortje G, Kola L, et al. Collaboration Between Biomedical and Complementary and Alternative Care Providers: Barriers and Pathways. Qualitative Health Research 2017; 27(14): 2177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbo C, Ekblad S, Waako P, Okello E, Musisi S. The prevalence and severity of mental illnesses handled by traditional healers in two districts in Uganda. Africa Health Science 2009; 9(Suppl 1): S16–S22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbo C, et al. Lay concepts of psychosis in Busoga, Eastern Uganda: a pilot study. J World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review 2008; 3(3): 132–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186: 436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy, 2014–2023; 2013.

- 10.Minas H, Diatri H. Pasung: Physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2008; 2: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campion J, Bhugra D. Experiences of religious healing in psychiatric patients in South India. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 1997; 32(4): 215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayombo EJ, et al. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2007; 3: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King R. Collaboration with traditional healers on prevention and care in Sub Saharan Africa: a practical guideline for programs. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Watt ASJ, Nortje G, Kola L, et al. Collaboration Between Biomedical and Complementary and Alternative Care Providers: Barriers and Pathways. Qual Health Res 2017; 27(14): 2177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esan O, Appiah-Poku J, Othieno C, et al. A survey of traditional and faith healers providing mental health care in three sub-Saharan African countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gureje O, Makanjuola V, Kola L, et al. COllaborative Shared care to IMprove Psychosis Outcome (COSIMPO): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017; 18(1): 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esan O, Appiah-Poku J, Othieno C, et al. A survey of traditional and faith healers providing mental health care in three sub-Saharan African countries. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IVTR Axis I Disorders Research Version, (SCID-I). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1987; 13(2): 261–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole NA, Crabb J, Osei A, Hughes P, Young D. Insight, psychosis, and depression in Africa: a cross-sectional survey from an inpatient unit in Ghana. Transcult Psychiatry 2013; 50(3): 433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88(11): 815–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiat Res 2003; 121(1): 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Susser E, Finnerty M, Mojtabai R, et al. Reliability of the life chart schedule for assessment of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2000; 42(1): 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chisholm D, Knapp MRJ, Knudsen HC, et al. Client socio-demographic and service receipt inventory - European version: development of an instrument for international research: EPSILON Study 5. British Journal of Psychiatry 2000; 177(suppl.39): s28–s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiliza B, Ojagbemi A, Esan O, et al. Combining depot antipsychotic with an assertive monitoring programme for treating first-episode schizophrenia in a resource-constrained setting. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016; 10(1): 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Group ftC. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Lancet 2001; 357: 1191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamin DJ, Berger JO, Johannesson M, et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nature human behaviour 2018; 2(1): 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbo C, Okello ES, Musisi S, Waako P, Ekblad S. Naturalistic outcome of treatment of psychosis by traditional healers in Jinja and Iganga districts, Eastern Uganda - a 3- and 6 months follow up. Int J Ment Health Syst 2012; 6(1): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Watt ASJ, van de Water T, Nortje G, et al. The perceived effectiveness of traditional and faith healing in the treatment of mental illness: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018; 53(6): 555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nortje G, Oladeji B, Gureje O, Seedat S. Effectiveness of traditional healers in treating mental disorders: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(2): 154–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arias D, Taylor L, Ofori-Atta A, Bradley EH. Prayer Camps and Biomedical Care in Ghana: Is Collaboration in Mental Health Care Possible? PloS one 2016; 11(9): e0162305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ofori-Atta A, Attafuah J, Jack H, Baning F, Rosenheck R, Joining Forces Research C. Joining psychiatric care and faith healing in a prayer camp in Ghana: randomised trial. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science 2018; 212(1): 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.