Abstract

The TATA binding protein (TBP) plays a central role in eukaryotic and archael transcription initiation. We describe the isolation of a novel 23-kDa human protein that displays 41% identity to TBP and is expressed in most human tissue. Recombinant TBP-related protein (TRP) displayed barely detectable binding to consensus TATA box sequences but bound with slightly higher affinities to nonconsensus TATA sequences. TRP did not substitute for TBP in transcription reactions in vitro. However, addition of TRP potently inhibited basal and activated transcription from multiple promoters in vitro and in vivo. General transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB bound glutathione S-transferase–TRP in solution but failed to stimulate TRP binding to DNA. Preincubation of TRP with TFIIA inhibited TBP-TFIIA-DNA complex formation and addition of TFIIA overcame TRP-mediated transcription repression. TRP transcriptional repression activity was specifically reduced by mutations in TRP that disrupt the TFIIA binding surface but not by mutations that disrupt the TFIIB or DNA binding surface of TRP. These results suggest that TFIIA is a primary target of TRP transcription inhibition and that TRP may modulate transcription by a novel mechanism involving the partial mimicry of TBP functions.

The TATA box is a promoter-proximal transcriptional regulatory element that positions the start site of RNA polymerase II transcription (reviewed in references 38 and 42). The TATA binding protein (TBP) binds directly to consensus TATA elements and provides a scaffold for the formation of an RNA polymerase II-dependent preinitiation complex (7; reviewed in reference 22). TBP was first isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae extracts as a protein that bound to the TATA box and substituted for general transcription factor IID (TFIID) in reconstituted transcription reactions for mammalian promoters (8, 12). The gene encoding TBP was subsequently cloned from multiple organisms and found to have highly conserved sequence and function throughout evolution. The evolutionary conservation of TBP was underscored by the discovery that all eukaryotes and some archaebacteria encode a TBP which functions as a general transcription factor for a multisubunit RNA polymerase (43). TBP is utilized by all three eukaryotic RNA polymerases, as well as from TATA-less promoters transcribed by RNA polymerase II, suggesting that it is a universal transcription factor (22).

In higher eukaryotes, TBP can be isolated as a component from a variety of multiprotein complexes. The TBP-associated factors (TAFs) were originally found by virtue of their ability to confer on TBP a responsiveness to transcriptional activators in vitro (10, 19). Subsequently, the multiprotein general transcription factors SL1 and TFIIIB for RNA polymerase I and III, respectively, were found to consist of TBP complexed with a distinct set of polymerase-specific TAFs (22). Thus, one function of the TAFs was to confer polymerase specificity. The polymerase II TAFs were also found to be essential for mediating transcription from a TATA-less promoter in vitro (10, 51), and several of the TAFIIs were found to have DNA binding specificity for core promoter sequences distinct from the TATA box itself (9, 16, 50). Thus, TAFIIs may function to recruit TBP to promoters lacking canonical TATA sequences. TBP can also be found in a complex with Mot1, a global regulator of transcription that can dissociate TBP from DNA in an ATP-dependent manner (5, 40). TBP has been biochemically isolated as a monomer from yeast, where its affinity for TAFs may be reduced relative to those found in higher eukaryotes (reviewed in reference 21).

The association of TBP with the TATA box nucleates the formation of a preinitiation complex consisting of other general transcription factors (38). The general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB bind directly to TBP, stabilize its association with the promoter, and form the core of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex (18, 36, 48). The formation of the TFIIA-TFIIB-TFIID promoter complex can be rate limiting for transcription and is subject to multiple forms of positive and negative regulation (13, 44). Diverse transcriptional modulators compete with TFIIA and TFIIB for access to the TBP surface and thus regulate preinitiation complex formation and activity (24). Crystallographic studies of the TBP-DNA, TFIIA-TBP-DNA, and TFIIB-TBP-DNA structures reveal that TBP functions as a molecular saddle that distorts and bends TATA DNA through a concave inner surface and makes protein contacts through a vast convex outer surface (18, 26, 27, 36, 48). The crystal structures of human, yeast, and archaebacterial TBPs are nearly identical and are thought to interact with DNA in a similar fashion (35).

Most organisms were thought to encode a single TBP gene, although specific organisms such as Arabidopsis thaliana encode two highly similar TBP proteins (17). Examination of the database of expressed sequence tags indicates that at least one additional TBP-related protein (TRP) exists in humans and mice, and examination of the complete Caenorabditis elegans genome suggests that most metazoan organisms have at least one TBP-related gene. Drosophila TBP-related factor 1(TRF1) is 56% identical to TBP and has been recently characterized (15). Like TBP, TRF can bind to TATA box elements, support basal transcription in vitro, and be isolated as a multiprotein complex (20). Unlike TBP, TRF expression is restricted primarily to neural tissue and thus may represent a tissue-specific form of TBP (15, 20). In this study, we describe a human gene encoding a TRP that is expressed in most human tissues but differs from both TBP and TRF1 in DNA binding and transcription properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA cloning.

The expressed sequence tag (EST) cDNA database at The Institute of Genomic Research and at Human Genome Sciences Inc. was screened for homologues of the human TBP with the BLAST Network service provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Multiple overlapping ESTs showing significant homology to the conserved carboxy-terminal region of human TBP were identified. The sequence of full-length human TRP cDNA clones revealed an open reading frame of 186 amino acids (aa) that encodes a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 20.9 kDa and an isoelectric point of 10.31.

Generation of GST fusion proteins.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST), GST-TRP, and GST-TBP were produced from Escherichia coli containing the plasmids pGEX2T, pGEX-TRP, and pGEX-TBP, respectively. pGEX-TRP was constructed by first amplifying the coding region of TRP, restricting the amplified fragment with BamHI and EcoRV, and cloning the fragment in frame with GST in BamHI- and SmaI-digested pGEX-2T (Pharmacia). pGEX-TBP was described previously (29). E. coli DH5α cells transformed with pGEX-TBP, pGEX-TRF, and pGEX-2T were grown in 2× Luria Broth (LB) supplemented with 2% glucose at 28°C until an absorbance at 600 nm of 0.3 was reached. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to 1 mM, and cultures were induced at 22°C for 4 h. Cells were harvested and washed twice in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then sonicated in 1× PBS supplemented with 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mg of aprotinin per ml, 2 mg of leupeptin per ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). After sonication, Triton X-100 was added to 0.1%, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 15 min. The clarified lysates were mixed with glutathione-Sepharose (Pharmacia) for 90 min at 4°C with gentle shaking. The beads were then washed four times in wash buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 200 mM KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT), and the fusion proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) at room temperature for 10 min. Eluted material was dialyzed directly into D100 buffer (100 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT) and stored in small aliquots at −70°C. GST-TRP-Amut, -Bmut, and -Dmut were generated by site-directed mutagenesis with the Quick Change system (Stratagene). GST-TRP-Amut contains alanine substitutions at K50 and R52. GST-TRP-Bmut contains alanine substitutions at E131 and E133. GST-TRP-Dmut contains alanine substitutions at W61 and K65.

EMSA.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were carried out with purified GST fusion protein and double-stranded oligonucleotides. For the adenovirus E1B (AdE1B) promoter TATA probe, the following pair of oligonucleotides was used: 5′-GGTTTCGACTTAAAGGGTATATAATGCGCCGTG-3′ and 5′-GGTTCACGGCGCATTATATACCCTTTAAGTCGA-3′. For the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) long terminal repeat TATA probe, the following pair of oligonucleotides was used: 5′-GGTTGCGTGCCTCAGATGCTGCATATAAGCCAGCTGCTT-3′ and 5′-GGTTAAGCAGCTGCTTATATGCAGCATCTGAGGCACGC-3′. For the 2N and 6N probes, the following oligonucleotides were used as templates for primer-directed double-strand synthesis: 5′-CAGTGCTCGAGGATCCGTGAATNNATATACGAAGCTTGAATTCCCGAGCG (2N) and 5′-CAGTGCTCGAGGATCCGTGANTNNATANNCGAAGCTTGAATTCCCGAGCG (6N). The primer oligonucleotide was 5′-CGCTCGGGAATTCAAGCTTCG-3′. Each pair of annealed double-stranded oligonucleotides was labeled by filling in with reverse transcriptase, 32P[dATP], and 32P[dCTP]. The AdE1B TATA box probe was a 30-mer oligonucleotide described previously (25). The AdE4, HSP70, simian virus 40 (SV40), and BZLF1 TATA probes contain BamHI and XhoI sticky ends, which were labeled by Klenow fill-in reaction. The top strand of each oligonucleotide is listed below: 5′-GATCCGGAGTATATATAGGACCTTG for AdE4, 5′-GATCCGGACTTATAAAAGCCCCTTG for HSP70, 5′-GATCCGCATTTTATTTATGCACTTG for SV40, and 5′-GATCCGGGCTTTAAAGGGGAGCTTG for BZLF1. The oligonucleotide probes used for the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 3C contain the following sequences: 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAAATTCACGCGGATCCGC (oPL120), 5′-GCGAAGCTTATAGATCCACGCGGATCCGC (oPL121), 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAAATCCACGCGGATCCGC (oPL122), 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAGATTGACGCGGATCCGC (oPL123), 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAAATTGACGCGGATCCGC (oPL124), 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAGATCGACGCGGATCCGC (oPL125), 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTAAATTGCACGCGGATCCGC (oPL126), and 5′-GCGAAGCTTCTATATAAACGCGGATCCGC (oPL127). (Underlining in all sequences above indicates TBP binding site TATA-like squence.) Double-stranded probes were generated by primer extension with oligonucleotide oPL118 (5′-GCGGATCCGCG) and Klenow polymerase. DNA binding reactions were performed with 15-μl reaction mixtures that contained approximately 50 to 100 ng of GST-TRP, 10 to 20 ng of GST-TBP, or 50 to 100 ng of GST protein incubated with 50,000 cpm of probe in a solution containing 12 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 60 mM KCl, 0.12 mM EDTA, 6 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 5 pmol of single-stranded DNA, 5.0 μg of bovine serum albumin, 20 μg of poly(dG-dC)–poly(dG-dC) (Pharmacia) per ml, and 0.5 mM DTT. TFIIA (50 ng) and TFIIB (10 to 50 ng) were used in complex-assembly assays as described previously (39). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 min at 30°C and analyzed on 5% acrylamide (39:1) polyacrylamide gels run in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA.

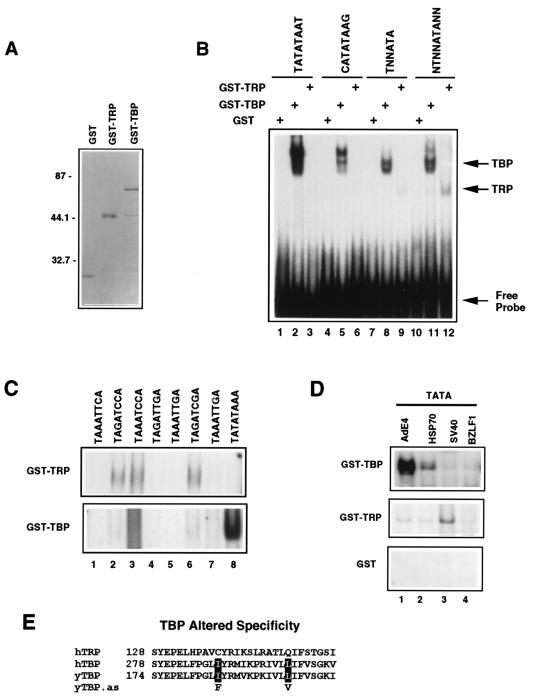

FIG. 3.

TRP lacks TATA binding activity. (A) Purified GST, GST-TRP, and GST-TBP were visualized by Coomassie staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are noted at the left. (B) GST, GST-TBP, and GST-TRP were incubated with the radiolabeled Ad E1B promoter TATA element (TATATAAT), the HIV long terminal repeat promoter TATA element (CATATAAG), an oligonucleotide with two degenerate nucleotides (TNNATA), or an oligonucleotide with five degenerate nucleotides (NTNNATANN). DNAs bound by GST-TBP and GST-TRP are indicated by the arrows at the right. (C) EMSA indicating the GST-TRP (top gel)- or GST-TBP (bottom gel)-bound fraction of oligonucleotides containing the TATA-related sequences as depicted above each lane. (D) EMSA indicating the GST-TBP-, GST-TRP-, or GST-bound fraction of oligonucleotides containing TATA box sequences derived from the AdE4 (TATATA), HSP70 (TATAAA), SV40 (TATTTA), or EBV BZLF1 (TTTAAA) promoter. (E) TRP contains amino acid changes at positions known to alter DNA binding specificities of human and yeast TBP. as, altered specificities.

GST interaction assay.

TFIIAαβ and TFIIB cDNAs cloned in pBSKII were used as templates for T7 polymerase-directed, coupled in vitro transcription-translation reactions with rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) supplemented with [35S]methionine. GST interaction assays were performed as described previously (39).

Transient-transfection assays.

HeLa cells were transfected and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays were performed essentially as described previously (31). TBP and TRP were expressed in eukaryotic cells from the expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) or pRTS2, a derivative of pSG5 (Stratagene). The Zta activator and Z7E4TCAT promoter have been described previously (11, 30). The p53 expression vector (pCR3-p53) was a gift of T. Halazonetis, and the p53 reporter plasmid was constructed by replacing the Zta response element sites of Z7E4TCAT with two p53 binding sites. EBNA1 was subcloned in pSRαcDL296 (47), used to activate p403.3, which contains Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oriP Dyad3xTKCAT (53). The GAL4VP16 expression vector and the G5E4TCAT reporter have been described previously (32).

In vitro transcription.

The purification of activators, transcription reaction, and primer extension assay have been described previously (39). Heat inactivation of TBP has also been described previously (34).

Northern blotting.

A multiple-tissue Northern blot (Clonetech) containing 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from eight tissue types was hybridized separately with randomly primed 32P-labeled probes (Boehringer) in 0.4 M NaCl–80 mM NaPO4 (pH 6.5)–4 mM EDTA–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 65°C overnight. The filters were then washed in 0.2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS at 25°C for 30 min and twice in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C for 30 min. For TBP, a 510-bp StuI-PvuII cDNA fragment corresponding to amino acids 98 to 270 of human TBP (25) was used as a probe; for TRP, the full-length 1.5-kb cDNA was used as the probe; and for TFIIAγ, the full-length 0.8-kb cDNA (39) was used as the probe. Blots were reprobed after the membrane was stripped by boiling it in 10% SDS for 10 min.

Western blotting.

Rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against hexahistidine-tagged TRP was purified over CM affigel blue (Bio-Rad) and used at a 1:200 dilution for detection of TRP in 250 μg of HeLa cell nuclear extract. Blots were visualized by the enhanced-chemiluminescence method (Amersham).

RESULTS

Isolation of a human cDNA encoding TRP.

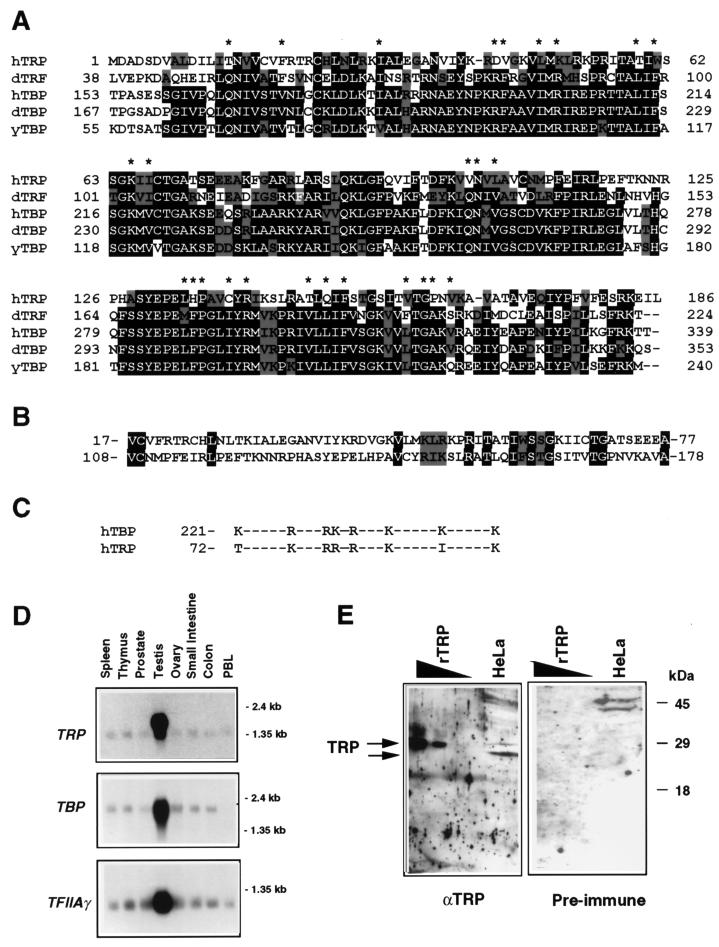

To determine if a mammalian gene encoding a protein with sequence similarity to TBP exists, a database of expressed sequence tags (1, 2) generated from multiple human tissues was searched with the BLAST algorithm (3). Multiple, overlapping tags showing significant homology to the conserved carboxy-terminal domain of TBP were identified. Sequence examination of the longest cDNA obtained revealed an mRNA capable of encoding a 186-aa open reading frame with significant similarity to TBP (data not shown). Comparison of the TRP amino acid sequence with those of TBPs from a variety of species revealed that TRP contains the conserved carboxy-terminal domain present in TBP and has only a 12-aa N-terminal domain, which is species specific for the TBP family (Fig. 1A). Comparison of TRP with the conserved domain of human TBP revealed a 41% identity over a span of 176 aa. In contrast, human TBP displays 81% identity with yeast TBP over the same region.

FIG. 1.

TRP sequence analysis and tissue distribution. (A) Alignment of the human TRP amino acid sequence with human (h), Drosophila (d), and yeast (y) TBP and Drosophila TRF1. White letters on a black background indicate amino acid identity. Black letters on a gray background indicate conservative changes in sequence. Asterisks indicate amino acid residues that make TBP DNA base contacts. (B) Alignment of the direct repeat sequence in human TRP. (C) Alignment of basic amino acid repeat regions of human TBP and TRP. (D) Tissue distribution of TRP expression determined by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA (2 μg) from various tissues was probed with 32P-labeled TRP (top gel), TBP (middle gel), or TFIIAγ (lower gel). The 1.35- and 2.4-kb RNA markers are indicated to the right. PBL, peripheral blood leukocytes. (E) TRP protein is made in HeLa cells. Polyclonal antibody directed against TRP (αTRP) or preimmune control serum was used to probe Western blots of HeLa cell nuclear extract (250 μg) or recombinant TRP (rTRP) (50 to 12 ng).

An important characteristic of all TBP proteins isolated thus far is the presence of two copies of an approximately 60-aa imperfect direct repeat sequence separated by a basic stretch of amino acids (22). Examination of the TRP amino acid sequence reveals that it likewise contains a 60-aa imperfect direct repeat sequence (Fig. 1B). In addition, the direct repeat sequences of TRP are separated by a stretch of basic amino acids, partially conserved with those present in TBP (Fig. 1C). Further analysis of the TRP amino acid sequence reveals that a subset of residues shown previously to be important for TBP DNA binding are also conserved in TRP but that others are clearly changed (Fig. 1A) (26, 27). Likewise, amino acids previously demonstrated to be important for the ability of TBP to interact with the general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB are largely conserved (see Fig. 6A) (6, 18, 36, 48, 49).

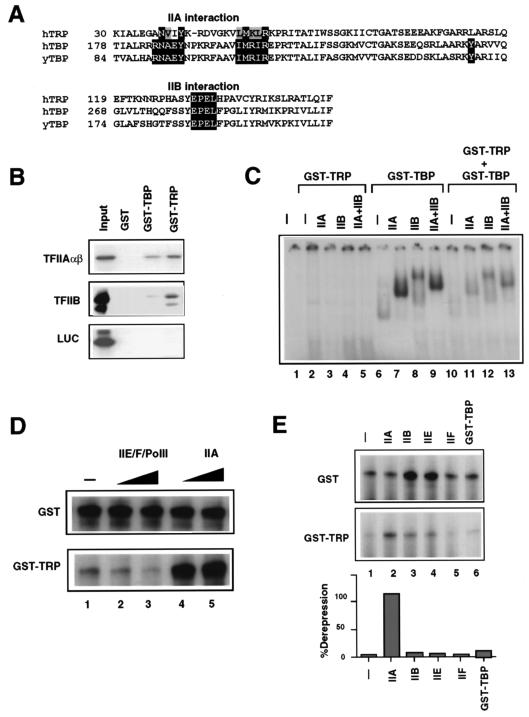

FIG. 6.

TFIIA can derepress TRP-mediated transcription inhibition. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment between TRP and human (h) and yeast (y) TBP residues known to interact with the general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB based on crystallographic and mutagenesis studies. (B) Interaction assay with purified GST, GST-TBP, and GST-TRP and in vitro-translated 35S-labeled TFIIAαβ (top gel), TFIIB (middle gel), or luciferase (LUC) (lower gel). Input represents 10% of the starting reaction mixture. (C) TRP inhibits TBP-TFIIA complex formation. The E1B TATA probe was preincubated with GST-TRP (lanes 2 to 5 and 10 to 13) and TFIIA (lanes 3, 7, and 11), TFIIB (lanes 4, 8, and 12), or both TFIIA and TFIIB (lanes 5, 9, and 13). GST-TBP (lanes 6 to 13) was added after a 15-min preincubation of other components and then incubated for an additional 30 min at 30°C. Bound complexes were analyzed by EMSA. (D) Transcription reaction mixtures reconstituted with HeLa nuclear extract, the GAL4-AH activator, and the G5E4TCAT template were incubated with 50 ng of GST control protein (top gel) or GST-TRP (lower gel). Transcription reaction mixtures were then supplemented with one or two transcription units of the TFIIE-TFIIF-polymerase II (PolII) fraction (lanes 2 and 3) or TFIIA (lanes 4 and 5). (E) Transcription reaction mixtures reconstituted with HeLa nuclear extract, the GAL4-AH activator, and the G5E4TCAT template were incubated with GST (top gel) or GST-TRP (bottom gel). Reaction mixtures were then supplemented with two transcription units of recombinant TFIIA (40 ng) (lane 2), TFIIB (20 ng) (lane 3), TFIIE (50 ng) (lane 4), TFIIF (50 ng) (lane 5), or GST-TBP (40 ng) (lane 6). Transcription derepression is quantified in the graph as percent derepression.

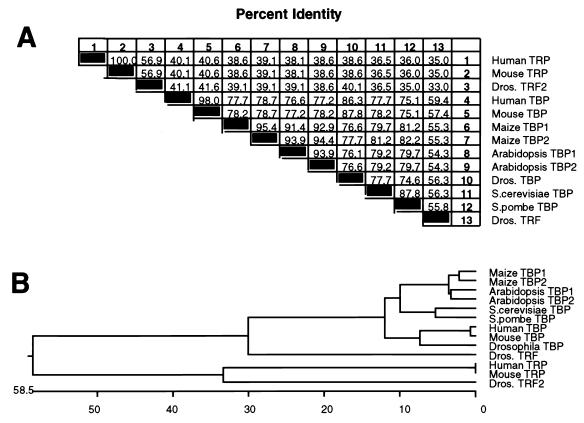

To determine the relationship between TRP and other TBP family members, the complete TRP amino acid sequence was aligned with those of the conserved carboxy-terminal domains of human, mouse, plant, insect, and yeast TBPs and with Drosophila TRF1 and TRF2 (41) and mouse TRP (37) with the CLUSTAL multiple-alignment algorithm in the Megalign package (DNASTAR) (Fig. 2A). This analysis shows that mouse and human TRPs are identical but that both are significantly diverged from Drosophila TRF1. As illustrated by the deduced phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2B), TRP demonstrates the greatest sequence divergence compared to the other TBP family members. Human TRP demonstrates equivalent levels of divergence from TBP (36.6% identity to human TBP; 34.2% identity to Drosophila TBP) and Drosophila TRF1 (33.2% identity), suggesting that TRP is not the ortholog of Drosophila TRF1 but is rather a distinct class of the TBP family.

FIG. 2.

Evolutionary relationships of the TBP family. (A) Percentages of similarity of TBP family members. (B) Phylogenetic tree of TBP and TRPs from various organisms. Numbers at the bottom represent percentages of disimilarity (i.e., TRP is 57.8% different than the other TBP molecules). Dros., Drosophila; S. pombe, Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

TRP is expressed in most human tissues.

Analysis of The Human Genome Sciences, Inc., and The Institute for Genomic Research database of cDNA sequences generated from approximately 300 different disease and normal tissue types revealed that TRP is expressed in a variety of human tissues and is highly represented in testes (data not shown). To determine if TRP has a tissue distribution similar to that of TBP, Northern blot analysis was performed (Fig. 1D). We found that the 1.6-kb TRP mRNA was expressed most predominantly in testes. However, a slightly smaller mRNA was expressed at lower levels in all the other tissue types examined, further suggesting that TRP is expressed ubiquitously. The expression pattern of TRP was compared with that of TBP, and the patterns were similar in all tissues examined. Likewise, the TFIIAγ mRNA was also abundant in testes and present at lower levels in all other tissue types, just as with TRP. The equal levels of integrity and quantities of RNA loaded in each lane were confirmed by probing the ubiquitously expressed interferon regulatory factor 3 mRNA (data not shown). To determine if TRP was expressed at detectable protein levels in human tissue culture cells, HeLa cell nuclear extract was examined by Western blotting for the presence of TRP. Purified polyclonal rabbit antisera raised against the ∼25-kDa recombinant hexahistidine-tagged TRP detected an ∼23-kDa protein in HeLa extracts, while no band of similar mobility was detected with preimmune serum (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that TRP is expressed at detectable levels in human tissue culture cells.

TRP has a reduced affinity for TATA sequences.

Sequence analysis indicated that TRP has several amino acid substitutions in positions that are important for TATA box recognition (Fig. 1A). To compare the in vitro DNA binding properties of TRP and TBP, recombinant TRP was expressed as a GST fusion protein and compared to GST-TBP or GST in EMSA. GST fusion proteins were approximately 90% pure after glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography (Fig. 3A). As expected, the GST-TBP protein was capable of binding both the AdE1B promoter TATA box (TATATAAT) and the HIV-1 TATA box (CATATAAG) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, under the same binding conditions, GST-TRP formed a barely detectable complex with both the HIV-1 and Ad TATA boxes. Thus, recombinant TRP has a significantly reduced binding affinity to TATA box sequences compared to that of recombinant TBP. To determine if TRP can bind DNA sequences related to the TATA box, its ability to bind a set of double-stranded oligonucleotides with increasing degeneracy from the canonical sequence was examined. GST-TRP bound weakly, but detectably, to both degenerate sequences, suggesting that GST-TRP can bind double-stranded oligonucleotides containing TATA-related sequences (Fig. 3B, lanes 9 and 12). Cleavage of the GST moiety did not improve the binding of TRP to any DNA sequence assayed (data not shown).

TRP has an altered DNA binding specificity relative to that of TBP.

GST-TRP was compared with GST-TBP for its ability to bind a panel of TATA-related sequences (Fig. 3C). TATA-related sequences were selected based on inspection of the cocrystal structure between TBP and TATA sequences, with nucleotide changes being selected to best accommodate differences in amino acid structure between TBP and TRP. Based on this analysis, we predicted that TRP binds preferentially to a TA(G/A)AT(C/T)(G/A)A sequence. All permutations of this degenerate sequence were tested in EMSA for binding to GST-TRP. We found that TAGATCCA, TAAATCCA, and TAGATCGA were the preferred TRP binding sites (Fig. 3C, top gel). The same series of TATA-related probes were tested for their ability to bind GST-TBP. We found that the consensus TATATAAA was the preferred recognition sequence for TBP binding, although weak binding was detected for TAGATCGA (Fig. 3C, lower gel, lanes 6 and 8).

GST-TRP was further compared to GST-TBP for the ability to bind to the naturally occurring TATA box elements from the AdE4 promoter (TATATA) and the HSP70 promoter (TATAAA) and to nonconsensus elements found in the SV40 early promoter (TATTTA) or the EBV BZLF1 promoter (TTTAAA). While GST-TBP bound to the AdE4 TATA most avidly, GST-TRP showed a weak (approximately threefold) preference for the SV40 nonconsensus TATA box (Fig. 3D). Comparison of TRP with TBP mutations that confer an altered DNA binding specificity predicts that TRP has an altered DNA binding specificity (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that TRP has a generally reduced TATA binding activity relative to that of TBP and that it prefers to bind sequences distinct from consensus TATA elements recognized by TBP.

TRP is a potent inhibitor of transcription.

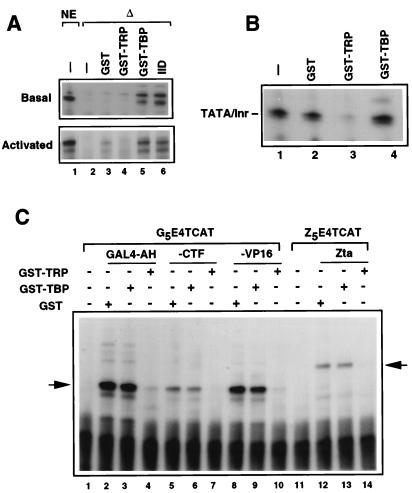

We next tested whether TRP functions similarly to TBP in transcription reactions. Biochemical preparations of TRP did not substitute for TBP in transcription reaction mixtures reconstituted with partially purified factors in vitro (data not shown). With heat-treated HeLa cell nuclear extracts, which inactivate TBP, TRP failed to stimulate transcription from a strong basal promoter (Fig. 4A, top gel) or from a promoter activated by Zta, a potent viral transactivator (Fig. 4A, lower gel). Thus, TRP does not substitute for TBP-stimulated transcription at TATA-containing promoters in vitro. To determine if TRP interacts with essential transcription factors to inhibit transcription, we assayed the effect of TRP when it was added to a nuclear extract competent for transcription (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we found that TRP, but not TBP or control GST protein, was a potent inhibitor of basal transcription directed by a promoter containing a consensus TATA element and an initiator (Inr) element (Fig. 4B, lane 3). To determine if TRP could similarly inhibit activated transcription in vitro, we tested the effect of TRP on transcription stimulated by GAL4-AH, GAL4-CTF, GAL4-VP16, and Zta. In all cases, TRP strongly inhibited transcription while similar concentrations of TBP and GST had no effect on activated transcription levels (Fig. 4C). Cleavage of the GST moiety and baculovirus-expressed TRP had similar repression activity to that of GST-TRP (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

TRP is a potent general transcription inhibitor in vitro. (A) TRP does not substitute for TBP. Nuclear extracts heat treated (Δ) to inactivate endogenous TBP were reconstituted with GST (lane 3), GST-TRP (lane 4), GST-TBP (lane 5), or partially purified TFIID (lane 6). Reaction mixtures with untreated nuclear extracts (NE) are indicated (lane 1). Shown is basal transcription with a TATA/Inr-containing promoter (top gel) or transcription activated by Zta (bottom gel). (B) Transcription reaction mixtures reconstituted with the untreated nuclear extracts and the TATA/Inr promoter in the presence of 50 ng of GST (lane 2), GST-TRP (lane 3), and GST-TBP (lane 4). (C) Transcription reaction mixtures activated by GAL4-AH (lanes 2 to 4), GAL4-CTF (lanes 5 to 7), GAL4-VP16 (lanes 8 to 10), or Zta (lanes 12 to 14) were reconstituted with 50 ng of GST (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 12), GST-TBP (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 13), or GST-TRP (lanes 4, 7, 10, and 14). Primer extension products from the G5E4TCAT and Z7E4TCAT reporters are indicated by the arrows at the left and right, respectively.

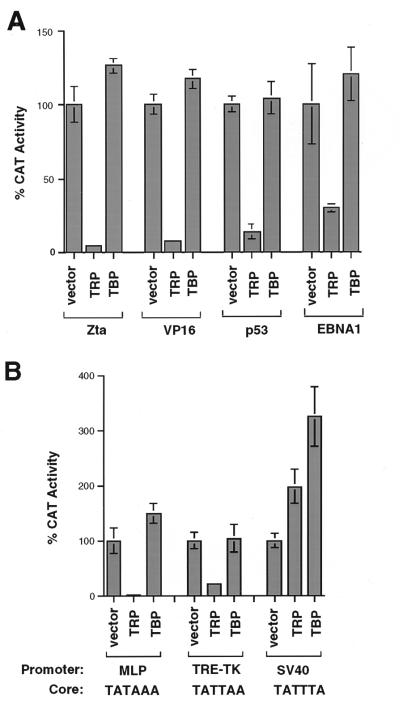

To determine if the inhibition of transcription by TRP was a peculiarity of the in vitro transcription assay, we tested the effect of TRP in transient-transfection assays. Work by others has shown that TBP stimulates transcription from several promoters and activators in transient-transfection assays in Drosophila Sf9 cells (14). We found that transfection of TBP in HeLa cells led to a very modest stimulation of transcription mediated by various transcriptional activators (Zta, VP16, p53, and EBNA1) (Fig. 5A). In contrast, transfection of TRP led to a dramatic inhibition of transcription from all of these activators (Fig. 5A). Transcription repression by TRP was not restricted to TATA-containing promoters since a similar level of inhibition was observed with Zta activation of a TGTA core promoter sequence (data not shown). Thus, TRP can function as a potent transcriptional inhibitor for multiple activators and core promoters in vitro and in vivo.

FIG. 5.

TRP inhibits transcription from some promoters in HeLa cells. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with expression vectors for the Zta, GAL4-VP16, p53, and EBNA1 transcriptional activators and their respective CAT reporter plasmids and were cotransfected with the expression vector alone, TRP, or TBP (as indicated in the figure). (B) HeLa cells were transfected with CAT reporters containing the promoters derived from the Ad MLP, the TPA response element (TRE)-HSV TK, or the SV40 early promoter. CAT constructs were cotransfected with the expression vector control (vector), TRP, or a TBP expression plasmid. The sequences of promoter core TATA elements are indicated below the promoters. Values are the averages of results of three independent transfections and set as percentages of activated transcription.

TRP may not function as a transcription repressor for all promoters. TRP was next tested for its ability to repress several promoters that produce high-level transcription activity in the absence of exogenously transfected activators (Fig. 5B). We found that TRP was a potent transcription inhibitor of the Ad major late promoter (MLP) and the TPA response element (TRE)-herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase (TK) core promoter fusion. In contrast to these promoters, TRP had slight stimulatory activity on the SV40 early promoter. Interestingly, the SV40 early promoter contains a nonconsensus TATA box that bound to TRP with slightly higher affinity than to consensus TATA elements (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that TRP may activate transcription from some promoters to which it binds.

TFIIA is a target of TRP-mediated repression.

To explore the mechanism of TRP transcription inhibition, we examined the ability of TRP to form a stable preinitiation complex with the general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB. As noted above, amino acid residues determined to be important for TFIIA and TFIIB binding in TBP are mostly conserved in TRP (Fig. 6A). To determine if TRP can associate with the general transcription factors TFIIB and TFIIA in the absence of DNA, we compared the abilities of GST-TRP and GST-TBP to bind in vitro-translated 35S-labeled TFIIB or the large subunit of TFIIA (Fig. 6B). Using a GST pull-down assay, we found that TRP bound to TFIIB and TFIIAαβ with affinities similar to that found for the binding with TBP (Fig. 6B). Thus, TRP can associate with TFIIB and TFIIA independently of DNA binding.

Both TFIIA and TFIIB can stabilize and alter the mobility of a TBP-TATA DNA complex in EMSA. TFIIA and TFIIB were tested for their ability to stabilize and/or alter the DNA binding properties of TRP by EMSA (Fig. 6C). As noted above, TRP did not bind stably to a consensus TATA box derived from the AdE1B promoter (Fig. 6C, lane 2). Addition of TFIIA or TFIIB or the combination of TFIIA and TFIIB had no detectable effect on TRP binding, while it significantly stabilized and altered the mobility of the TBP-TATA complex (Fig. 6C, lanes 2 to 9). To determine if TRP inhibited transcription by competing with TBP for the association of other general transcription factors, we tested TRP’s ability to inhibit preinitiation complex formation with TBP (Fig. 6C, lanes 10 to 13). Preincubation of TRP with TFIIA significantly inhibited the ability of TBP to complex with TFIIA (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 11 and 7). Preincubation of TRP with TFIIB modestly reduced TBP-TFIIB complex formation (lanes 12 and 8), and preincubation with TFIIA and TFIIB had an intermediate effect on the TBP-TFIIA-TFIIB complex (lanes 13 and 9). These results indicate that TRP interferes with TBP-TFIIA complex formation and suggest a potential mechanism by which TRP inhibits some transcription activation pathways.

One mechanism of TRP transcriptional inhibition may be the sequestration of an essential general transcription factor. In the above-described experiments, we found that TRP could inhibit TBP-TFIIA complex formation and bind TFIIA avidly in the absence of promoter DNA (Fig. 6B and C). If TRP competes for TFIIA, then transcription repression by TRP should be reversible by addition of a molar excess of TFIIA. To directly test this model, transcription reactions stimulated to high levels by GAL4-AH activation were subjected to inhibition with addition of TRP (Fig. 6D and E, compare lanes 1 in both gels). Addition of a molar excess of the TFIIE-TFIIF-polymerase II fraction did not restore transcription to nonrepressed transcription levels (Fig. 6D, lower gel, lanes 2 and 3). However, addition of two transcription units of recombinant TFIIA completely reversed the TRP-mediated transcription repression (Fig. 6D, lower gel, lanes 4 and 5). Addition of two transcription units of recombinant TFIIB, TFIIE, TFIIF, or GST-TBP did not rescue GST-TRP transcription repression, while repression was reversed by the addition of TFIIA (Fig. 6E). Recombinant TFIIB and TFIIE stimulated transcription in the absence of TRP, but they did not reverse the effects of TRP-mediated repression, as demonstrated by quantitative comparison of GST-TRP and GST transcription levels (Fig. 6E, bar graph).

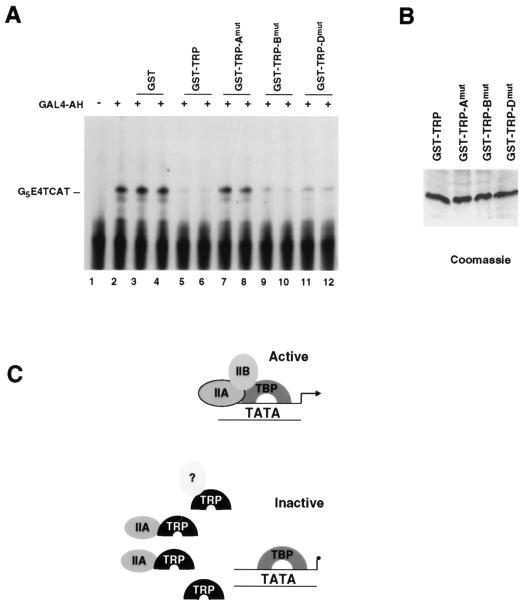

To further study the role of TFIIA as a primary target of TRP-mediated transcriptional repression, we generated mutations in TRP residues predicted to be binding surfaces for TFIIA (GST-TRB-Amut), TFIIB (GST-TRB-Bmut), or DNA (GST-TRP-Dmut). Amino acid residues chosen for mutagenesis were selected based on conservation with TBP and the known crystal structure contacts between TBP and TFIIA, TFIIB, and DNA. These mutants were expressed in E. coli and purified to near homogeneity (Fig. 7B). GST-TRP mutants were then compared to wild-type GST-TRP for their ability to repress transcription from the GAL4-AH activator and the G5E4TCAT template. GAL4-AH activated transcription nearly 10-fold (Fig. 7A, lane 2). Addition of GST had no effect on transcription levels (lanes 3 and 4). Addition of GST-TRP reduced transcription to basal levels (lanes 5 and 6). GST-TRP-Amut had no effect on transcription activation levels (lanes 5 and 6), indicating that this mutant had lost transcription repression function. In contrast, GST-TRP-Bmut and GST-TRP-Dmut did not lose transcription repression function (lanes 9 to 12). These results indicate that the TFIIA interaction domain of TRP is required for its transcriptional repression function and further suggest that TRP represses transcription by sequestering TFIIA.

FIG. 7.

A TRP mutant fails to repress transcription. (A) Transcription reaction mixtures were reconstituted with HeLa nuclear extract and the G5E4TCAT template. The GAL4-AH activator was added to the reaction mixtures in lanes 2 to 12. Reaction mixtures were supplemented with 40 ng of GST (lanes 3 and 4), GST-TRP (lanes 5 and 6), GST-TRP-Amut (lanes 7 and 8), GST-TRP-Bmut (lane 9 and 10), or GST-TRP-Dmut (lanes 11 and 12). (B) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of GST-TRP, GST-TRP-Amut, GST-TRP-Bmut, and GST-TRP-Dmut preparations stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (C) Model depicting the sequestration of TFIIA and potentially other unidentified TBP-interacting proteins (?) by TRP away from the TBP-TATA complex. TRP fails to bind TATA DNA but can efficiently bind TFIIA in solution. High levels of TRP down regulate TBP-dependent transcription by making TFIIA limiting for transcription.

DISCUSSION

Human TRP exhibits 41% identity with the conserved carboxy-terminal core of TBP, which is known to be important for TATA box binding and interaction with other transcription factors. TRP contains sequence features characteristic of all members of the TBP family of proteins, including a direct repeat with a basic linker region. The mouse homologue of TRP (referred to as TLP) was recently isolated and found to have no DNA binding activity or the ability to substitute for TBP in reconstituted transcription reaction mixtures with basal factors (37). In this study, we found that recombinant human TRP had very low affinity for consensus TATA box sequences but that it bound TATA-related sequences with higher relative affinity. This suggests that TRP can recognize unique sequences distinct from TATA elements. Inspection of TRP reveals that amino acids critical for DNA binding specificity in TBP are altered in TRP. A well-characterized mutation in yeast TBP (I194F, L205V) confers an altered DNA binding specificity from TATA to TGTA (46). The corresponding amino acids in TRP are replaced with Cys and Gln, respectively, and thus may confer a novel DNA recognition sequence (Fig. 3E). Similarly, the spt15 mutations L205F and L114F suppress a Ty insertion element by utilizing an alternative transcriptional initiation site and have relaxed DNA binding specificities (4). The corresponding positions in TRP have varied these amino acids to Gln 150 and Thr 59, respectively. Thus, inspection of the TRP amino acid sequence predicts an altered DNA binding specificity and our experimental data is consistent with this prediction.

While TRP did not substitute for TBP in transcription reactions in vitro, we found that TRP was a potent general inhibitor of basal and activated transcription for multiple promoters and activators (Fig. 4). TRP also inhibited transcription in transient-transfection assays, while TBP stimulated or had no effect on expression levels (Fig. 5). While TRP inhibited transcription from the consensus TATA elements of the Ad MLP and the HSV TK promoter, TRP did not repress transcription from the nonconsensus TATA element of the SV40 early promoter (Fig. 5B). We also found that TRP bound to the SV40 early promoter TATA element with threefold higher affinity than it bound to several consensus TATA elements (Fig. 3D). Based on these results, we hypothesize that TRP inhibits promoters with consensus TATA elements (MLP) yet activates transcription from promoters with TATA-related sequences to which it may bind (e.g., SV40).

Transcription inhibition by TRP occurred in HeLa and 293 cells when TRP was expressed at relatively low levels, based on Western blotting of transfected cells (data not shown). Furthermore, concentrations of TRP required for inhibition of transcription in vitro were comparable to the amounts of TBP required to stimulate transcription (10 to 50 ng). We estimate that 50 ng of TRP is an ∼10-fold molar excess of the amount of native TRP in the 100 μg of HeLa nuclear extract used in transcription reactions. This finding suggests that TRP-mediated transcription inhibition is not merely an artifact of high expression levels but that it may occur in some cell types or under conditions where TRP is at a high concentration relative to those of TFIIA and other general transcription factors.

The association of TFIIA with TBP can be rate limiting for activated and basal transcription in vivo or with partially purified factors in vitro (44, 45, 52). Our experiments suggest that TFIIA is a primary target of TRP-mediated transcription inhibition. TRP repression was prevented by the addition of recombinant TFIIA but not by the addition of comparable amounts of recombinant TFIIB, TFIIE, TFIIF, or TBP (Fig. 6D and E). TRP bound to TFIIAαβ in solution (Fig. 6B). TRP was inhibitory to the formation of the TFIIA-TBP complex in EMSA reactions (Fig. 6C). The amino acid residues in TBP determined to be important for TFIIA and TFIIB binding are well conserved between TBP and TRP (Fig. 6A). TRP mutations in the conserved amino acid residues predicted for TFIIA binding disrupted its transcriptional repression in vitro (Fig. 7A). Similar mutations in the predicted TFIIB or DNA binding surfaces had no effect on TRP-mediated repression. Taken together, these data support a model in which TRP can bind to TFIIA and prevent its ability to function as a coactivator at TBP-dependent promoters (Fig. 7C).

TBP associates with a variety of other polypeptides important for transcription regulation, and it is unclear which, if any, of these may also bind TRP. In particular, TAFs for all classes of RNA polymerase associate with TBP and mediate promoter specificity and activator regulation. The Drosophila TRF1 protein associates with a unique class of factors that function analogously to TAFIIs (20). At present, we do not know whether TRP can compete with TBP for any TAFs or if it has its own family of associated polypeptides, like Drosophila TRF1, that may alter its DNA binding specificity and transcription function in vivo.

Several inhibitors of general transcription factors have been characterized previously. Dr1 (also called NC2) inhibits preinitiation complex formation by binding to TBP and preventing TFIIB association (23). Mot1 can bind TBP and dissociate TBP from DNA in an ATP-dependent manner (5). TAFII230 may also be a general inhibitor of transcription since it can inhibit TBP binding to DNA and compete with TFIIA binding to TBP (28). Interestingly, the structure of TAFII230 resembles the distorted TBP-bound DNA, which binds directly to the DNA binding surface of TBP in a competitive manner (33). We suggest that TRP represses transcription by mimicking the TBP surface required for TFIIA interactions but that it fails to bind the TATA sequence with high affinity. Thus, TRP down regulates TBP-dependent transcription by acting as a molecular decoy that sequesters essential general factors, like TFIIA, from binding authentic TBP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

P.A.M. and J.O. made equal contributions to this work.

We thank Chi-Ju Chen and other members of the Lieberman lab for advice and assistance. We acknowledge the HGS sequencing facility.

P.A.M is a recipient of a Michael Bennet/AmFar scholarship. J.O. is the recipient of a Howard Temin award (NCI). P.M.L. is a Leukemia Society scholar. This work was supported by NIH grant GM54687 to P.M.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, Dubnick M, Kerlavage A R, Moreno J M, Kelley T R, Utterback T R, Nagle J W, Fields C, Venter J C. Sequence identification of 2,375 human brain genes. Nature. 1992;355:632–634. doi: 10.1038/355632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams M D, Kelley J M, Gocayne J D, Dubnick M, Polymeropoulos M H, Xiao H, Merril C R, Wu A, Olde B, Moreno R F, Kerlavage A R, McCombie W R, Venter J C. Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project. Science. 1991;252:1651–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2047873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arndt K M, Ricupero S L, Eisenmann D M, Winston F. Biochemical and genetic characterization of a yeast TFIID mutant that alters transcription in vivo and DNA binding in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2372–2382. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auble D T, Hansen K E, Mueller C G, Lane W S, Thorner J, Hahn S. Mot1, a global repressor of RNA polymerase II transcription, inhibits TBP binding to DNA by an ATP-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1920–1934. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant G O, Martel L S, Burley S K, Berk A J. Radical mutations reveal TATA-box binding protein surfaces required for activated transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2491–2504. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Guarente L, Sharp P A. Five intermediate complexes in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1989;56:549–561. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Sharp P S, Guarente L. Functions of a yeast TATA element-binding protein in a mammalian transcription system. Nature. 1988;334:37–42. doi: 10.1038/334037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey M, Kolman J, Katz D A, Gradoville L, Barberis L, Miller G. Transcriptional synergy by the Epstein-Barr virus transactivator ZEBRA. J Virol. 1992;66:4803–4813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4803-4813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavallini B, Huet J, Plassat J, Sentenac A, Egly J, Chambon P. A yeast activity can substitute for the HeLa cell TATA box factor. Nature. 1988;334:77–80. doi: 10.1038/334077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choy B, Green M R. Eukaryotic activators function during multiple steps of preinitiation complex assembly. Nature. 1993;366:531–536. doi: 10.1038/366531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colgan J, Manley J L. TFIID can be rate limiting in vivo for TATA-containing, but not TATA-lacking, RNA polymerase II promoters. Genes Dev. 1992;6:304–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowley T E, Hoey T, Liu J-K, Jan Y N L, Jan Y, Tjian R. A new factor related to TATA-binding protein has highly restricted expression in Drosophila. Nature. 1993;361:557–561. doi: 10.1038/361557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emami K H, Jain A, Smale S T. Mechanism of synergy between TATA and initiator: synergistic binding of TFIID following a putative TFIIA-induced isomerization. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3007–3019. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasch A, Hoffmann A, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Chua N. Arabidopsis thaliana contains two genes for TFIID. Nature. 1990;346:390–394. doi: 10.1038/346390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geiger J H, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler P B. The crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–836. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodrich J A, Tjian R. TBP-TAF complexes: selectivity factors for eukaryotic transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:403–409. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen S K, Takada S, Jacobson R H, Lis J T, Tjian R. Transcription properties of a cell type-specific TATA-binding protein, TRF. Cell. 1997;91:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hempsey M. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:465–503. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.465-503.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez N. TBP, a universal eukaryotic transcription factor? Genes Dev. 1993;7:1291–1308. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inostroza J A, Mermelstein F H, Ha I, Lane W S, Reinberg D. Dr1, a TATA-binding protein-associated phosphoprotein and inhibitor of class II gene transcription. Cell. 1992;70:477–489. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser K, Meisterernst M. The human general co-factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:342–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kao C C, Lieberman P M, Schmidt M C, Zhou Q, Pei R, Berk A J. Cloning of a transcriptionally active human TATA binding factor. Science. 1990;248:1646–1650. doi: 10.1126/science.2194289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J L, Nikolov D B, Burley S K. Co-crystal structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of a TATA element. Nature. 1993;365:520–527. doi: 10.1038/365520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y, Geiger J H, Hahn S, Sigler P B. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature. 1993;365:512–520. doi: 10.1038/365512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokubo T, Yamashita S, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Nakatani Y. Interaction between the N-terminal domain of the 230-kDa subunit and the TATA box-binding subunit of TFIID negatively regulates TATA-box binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3520–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee W S, Kao C C, Bryant G O, Liu X, Berk A J. Adenovirus E1A binds to the TATA-box transcription factors TFIID. Cell. 1991;67:365–376. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberman P M, Berk A J. The Zta trans-activator protein stabilizes TFIID association with promoter DNA by direct protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2441–2454. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lieberman P M, Ozer J, Gursel D B. Requirement for TFIIA-TFIID recruitment by an activator depends on promoter structure and template competition. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6624–6632. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y S, Green M R. Mechanism of action of an acidic transcriptional activator in vitro. Cell. 1991;64:971–981. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90321-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu D, Ishima R, Tong K I, Bagby S, Kokubo T, Muhandiram D R, Kay L E, Nakatani Y, Ikura M. Solution structure of a TBP-TAF(II)230 complex: protein mimicry of the minor groove surface of the TATA box unwound by TBP. Cell. 1998;94:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakajima M, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: purification, genetic specificity, and TATA-box promoter interactions of TFIID. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4028–4040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikolov D B, Burley S K. RNA polymerase II transcription initiation: a structural view. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;94:15–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolov D B, Chen H, Halay E D, Usheva A A, Hisatake K, Lee D K, Roeder R G, Burley S K. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature. 1995;377:119–128. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohbayashi T, Makino Y, Tamura T. Identification of a mouse TBP-like protein (TLP) distantly related to the Drosophila TBP-related factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:750–755. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozer J, Moore P A, Bolden A H, Lee A, Rosen C A, Lieberman P M. Molecular cloning of the small (gamma) subunit of human TFIIA reveals functions critical for activated transcription. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2324–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poon D, Knittle R A, Sabelko K A, Yamamoto T, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Weil P A. Genetic and biochemical analyses of yeast TATA-binding protein mutants. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5005–5013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabenstein M D, Zhou S, Lis J T, Tjian R. TATA box-binding protein (TBP)-related factor 2 (TRF2), a third member of the TBP family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4791–4796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowland T, Baumann P, Jackson S P. The TATA-binding protein: a general transcription factor in eukaryotes and archaebacteria. Science. 1994;264:1326–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.8191287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stargell L, Struhl K. Mechanisms of transcriptional activation in vivo: two steps forward. Trends Genet. 1996;12:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stargell L A, Struhl K. The TBP-TFIIA interaction in response to acidic activators in vivo. Science. 1995;269:75–78. doi: 10.1126/science.7604282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Struben M, Struhl K. Yeast and human TFIID with altered DNA-binding specificity TATA elements. Cell. 1992;68:721–730. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takebe Y, Seiki M, Fujisasa J-I, Hoy P, Yokota K, Arai K-I, Yoshida M, Arai N. SRα promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA promoter and R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:466–472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996;381:127–134. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang H, Sun X, Reinberg D, Ebright R H. Protein-protein interactions in eukaryotic transcription initiation: structure of the preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1119–1124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verrijzer C P, Chen J L, Yokomori K, Tjian R. Binding of TAFs to core elements directs promoter selectivity by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1995;81:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verrijzer C P, Tjian R. TAFs mediate transcriptional activation and promoter selectivity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang W, Gralla J D, Carey M. The acidic activator GAL4-AH can stimulate polymerase II transcription by promoting assembly of a closed complex requiring TFIID and TFIIA. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1716–1727. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wysokenski D A, Yates J L. Multiple EBNA1-binding sites are required to form an EBNA1-dependent enhancer and to activate a minimal replicative origin within oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1989;63:2657–2666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2657-2666.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]