Abstract

Background

Babesia spp. are protozoan parasites of great medical and veterinary importance, especially in the northern Hemisphere. Ticks are known vectors of Babesia spp., although some Babesia-tick interactions have not been fully elucidated.

Methods

The present review was performed to investigate the specificity of Babesia-tick species interactions that have been identified using molecular techniques in studies conducted in the last 20 years under field conditions. We aimed to indicate the main vectors of important Babesia species based on published research papers (n = 129) and molecular data derived from the GenBank database.

Results

Repeated observations of certain Babesia species in specific species and genera of ticks in numerous independent studies, carried out in different areas and years, have been considered epidemiological evidence of established Babesia-tick interactions. The best studied species of ticks are Ixodes ricinus, Dermacentor reticulatus and Ixodes scapularis (103 reports, i.e. 80% of total reports). Eco-epidemiological studies have confirmed a specific relationship between Babesia microti and Ixodes ricinus, Ixodes persulcatus, and Ixodes scapularis and also between Babesia canis and D. reticulatus. Additionally, four Babesia species (and one genotype), which have different deer species as reservoir hosts, displayed specificity to the I. ricinus complex. Eco-epidemiological studies do not support interactions between a high number of Babesia spp. and I. ricinus or D. reticulatus. Interestingly, pioneering studies on other species and genera of ticks have revealed the existence of likely new Babesia species, which need more scientific attention. Finally, we discuss the detection of Babesia spp. in feeding ticks and critically evaluate the data on the role of the latter as vectors.

Conclusions

Epidemiological data have confirmed the specificity of certain Babesia-tick vector interactions. The massive amount of data that has been thus far collected for the most common tick species needs to be complemented by more intensive studies on Babesia infections in underrepresented tick species.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-021-05019-3.

Keywords: Piroplasm, Polymerase chain reaction, Sequencing, Phylogenetic analysis, Ticks

Background

Babesia spp. are protozoan parasites of great medical and veterinary importance, especially in the northern Hemisphere [1, 2]. Amongst the many Babesia species that infect animals, Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina are notable for the significant economic losses they cause in the cattle industry worldwide [3], and several Babesia species (i.e. Babesia canis, Babesia rossi, Babesia vogeli, Babesia gibsoni, Babesia conradae and Babesia vulpes) may cause serious health problem in dogs [4–6]. There is increasing interest in babesiosis in humans due to the rising number of cases in the USA [2, 7], Canada [8] and China [7, 9]. In the USA alone, the cumulative number of cases of babesiosis in humans from 2006 to 2018 was estimated to be between 20,000 and 24,000 [7]. In Canada, over 1100 human cases, mostly due to Babesia duncani, have been recently reported [7, 8]. In China, over 125 cases have been reported, including 58 due to a Babesia crassa-like novel pathogen [7, 9–12].

Hard ticks are the vectors of Babesia parasites, which are emerging tick-borne pathogens [1, 13]. In a recent review/meta-analysis on Babesia spp. prevalence in questing ticks, the estimated global prevalence was 2.1% [14]. However, this prevalence was calculated jointly for 19 different Babesia species and 23 tick species.

In the life cycle of piroplasms, obligate intracellular parasites that belong to the phylum Apicomplexa [15, 16], ticks play a pivotal role as definitive hosts, in which sexual reproduction of the parasite (gametogony) occurs, followed by asexual amplification (sporogony), resulting in life stages invasive for vertebrate hosts (sporozoites). As highly specialized intracellular parasites, Babesia are believed to display a high specificity for both tick vectors and vertebrate hosts [1]. However, humans may be an example of broadened/disrupted host specificity for Babesia, as there is no human-specific Babesia species and babesiosis in humans is caused by several zoonotic species, including Babesia microti, Babesia divergens, Babesia venatorum, Babesia duncani and Babesia crassa-like [2, 7, 9].

Interestingly, a single tick species may act as a specific vector for several species of Babesia, e.g. Ixodes ricinus has already been indicated as a presumptive vector for at least nine species of Babesia, Ixodes persulcatus for five, and Dermacentor reticulatus for six [14]. However, this phenomenon is not contradictory to the specificity of certain Babesia sp.-tick vector interactions. In addition, the main vectors for many important Babesia species, including B. conradae, B. duncani and B. crassa-like, have yet to be identified.

This review was carried out to investigate the specificity of Babesia-tick interactions that have been identified using molecular techniques in studies performed over the past 20 years under field conditions. Based on published research papers and molecular data derived from the GenBank database (Additional file 1: Text S1), we indicate the main vectors for important Babesia species. Finally, we discuss the detection of Babesia spp. in feeding ticks and critically evaluate the data on the role of the latter as vectors.

Proving the specificity of a Babesia-tick vector interaction

The first records of babesiosis in cattle (also termed Texas fever or redwater disease) and dogs (also termed malignant jaundice and bilious fever) are from the end of the nineteenth century (reviewed in [3, 4, 6]). At that time, a classical approach to identifying the etiological agent and vector of a disease was based on experimental infection under controlled conditions by injecting blood from an infected dog into a naïve one, or through the infestation of naïve animals with a suspected tick vector [6]. For canine babesiosis, early research carried out from the 1890s to the 1930s showed that there were three distinct vector-specific parasites in different regions of the world. Interestingly, this knowledge was overlooked for the next 50 years, and only at the end of twentieth century was the ‘Babesia canis’ complex of species divided into three distinct vector-specific species: Babesia canis, with the ornate dog tick D. reticulatus as its vector; Babesia rossi, with Haemaphysalis elliptica as its vector; and Babesia vogeli, with the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (s.l.) as its vector [6, 17, 18].

In recent years, the use of novel laboratory/molecular biology techniques allowing for the identification of genetic material of pathogens/endosymbionts in ticks collected from humans, domestic animals, wildlife, or the environment, has resulted in an enormous increase in new data on tick-microorganism interactions. This rapidly growing amount of new information for various tick-borne pathogens, including Babesia, presents challenges, including how the detection of the genetic material of pathogens in ticks should best be interpreted [19]. A review focused on the vector competence of hard ticks and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes [20] underlined the pitfalls of concluding vector competence based only on the detection of pathogen DNA in ticks, i.e. without complementary experimental studies.

A well-established, experimental approach to conclusively prove vector competence should encompass three distinct processes: the acquisition of a piroplasm by uninfected ticks feeding on an infected experimental host (or on infected blood in in vitro experiments); the maintenance of the piroplasm through the moult to the next life stadium (transstadial transmission); and, finally, transmission of the piroplasm to naïve hosts during a subsequent blood meal (based on [20]). A tick species should not be considered a competent vector of Babesia spp. unless all three of these processes have been experimentally demonstrated. These kinds of experiments are laborious and expensive due to difficulties in obtaining infective piroplasm isolates, the raising of laboratory colonies of ticks of appropriate species (including artificial feeding and infection of ticks), and/or access to specific vertebrate hosts of babesiae. Therefore, it is not surprising that the great majority of studies on species of Babesia in ticks are presently based on field-derived data, with the application of molecular techniques for the detection of DNA of the piroplasm in questing and/or engorged ticks [14, 21–30].

In the case of field-derived data, the detection of Babesia DNA in engorged ticks (of any life stage) collected from human or animal hosts is only indicative of the acquisition of piroplasms from an infected host. It is worth remembering that, although the majority of humans are free of tick-borne pathogens, piroplasm infections may be very common among free-living animals (i.e. > 80% in roe deer and > 60% in red foxes; [21]) or circulating among pets and livestock [26, 31]. Whereas detection of Babesia DNA in questing (host-seeking) larvae suggests successful transovarial transmission, detection in questing nymphs or adult ticks indicate that babesiae were both acquired during the blood meal in the preceding life stadium and passed through the moult (transstadial transmission) [20, 32], confirming the occurrence of at least two of the key processes mentioned above.

However, field-derived data alone can never satisfy the final criterion of vector competence (the unequivocal demonstration of the transmission of babesiae by a feeding tick), but may provide important information on actual health risks constituted by certain tick species in certain regions, habitats or conditions.

Confirmed and unconfirmed interactions between Babesia and Ixodes spp.

Confirmed interactions between Babesia capreoli, Babesia divergens, Babesia microti, Babesia venatorum and I. ricinus

Ixodes ricinus has been the best-examined tick species for babesiae in recent years [33–104], with the wide application of molecular techniques for piroplasm identification resulting in the confirmation of a specific vector role of this tick species for at least four species of Babesia: B. venatorum, B. microti, B. divergens and B. capreoli (Additional file 2: Table S1). Interestingly, in the papers published between 2000 and 2010, mostly B. microti and B. divergens were reported in I. ricinus, and only in the last 5–10 years have the range and ranking of Babesia species expanded and changed. Babesia venatorum (previously known as ‘Babesia sp. EU1’) has been more frequently reported in I. ricinus since its identification as a species separate from B. divergens [105], and seems to be more common/widespread than B. microti or B. divergens (Additional file 2: Table S1). Similarly, since the detailed re-description of B. capreoli by Malandrin et al. [106] in a study which also provided a simple method to differentiate between B. capreoli and B. divergens based on the presence of three single nucleotide polymorphisms in a complete 18S ribosomal DNA sequence (rDNA), both the recognition and reported prevalence of B. capreoli in I. ricinus have increased. It is worth underlining here that B. capreoli, B. venatorum and B. divergens all belong to the Babesia sensu stricto group (clade X; [107]) and share a high similarity (up to 99.8% identity; [105, 106]) in the conserved 18S rRNA gene. Consequently, before wide recognition of B. capreoli and B. venatorum, these two species could have been (mis)identified as B. divergens or B. divergens-like, and this (mis)identification could have contributed to a higher reported prevalence of B. divergens in papers published in the period between 2000 and 2010 (Additional file 2: Table S1). It has also contributed to misidentification of B. divergens in human cases of babesiosis [105]. Better awareness of this is still needed for differentiation between these three Babesia species. Moreover, co-infection of ticks with different combinations of B. venatorum, B. capreoli and B. divergens has also been reported in several recent studies [21], and may have contributed to the lack of proper identification of the species involved. Ixodes ricinus ticks can acquire these three Babesia species when feeding on domestic and free-living ungulates, including cattle (acquisition of B. divergens), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus; acquisition of B. capreoli and B. venatorum) and red deer ((Cervus elaphus; acquisition of B. divergens) [21, 106, 108–110]. In natural conditions, deer species (roe deer Capreolus capreolus and red deer Cervus elaphus) are considered the most important sources of a blood meal for I. ricinus females, and the presence/density of deer is positively associated with the occurrence/density of I. ricinus [111].

Among the numerous studies on Babesia in I. ricinus ticks, the largest dataset (between 18,000 and 25,000 examined ticks) originated from long-term (2000–2019) studies in the Netherlands and Belgium (Additional file 2: Table S1; [21]). Four Babesia species from two clades and a Babesia sp. deer genotype were identified in this dataset: B. venatorum (210 positive ticks, prevalence 0.8%); B. microti-like [45 sequences of B. microti, prevalence of B. microti-like (clade 1) 2.6%]; B. capreoli (11 positive ticks, prevalence 0.04%); B. divergens (four positive ticks, prevalence 0.01%); and Babesia sp. deer genotype (Babesia odocoilei-like, one sequence, prevalence < 0.01%).

Additional evidence supporting the specific interactions between I. ricinus and these four Babesia species is the repeated observations of these babesiae in different European countries (Additional file 2: Table S1). Interestingly, apart from a single observation for D. reticulatus, these species of Babesia have not been observed in other (questing) tick species that did not belong to the genus Ixodes (Table 1). Three of these species were additionally identified in two other Ixodes species from Eurasia, i.e. B. capreoli, B. microti, and B. venatorum in Ixodes persulcatus from Mongolia, Russia and Japan, and B. microti in Ixodes pavlovskyi from Russia (Additional file 2: Table S1; [112]). These tick species constitute the ‘I. ricinus complex’, thus the observed Babesia-tick interactions may be specific for all the species in the complex; however, this idea needs further investigation.

Table 1.

Species of Babesia reported in Dermacentor spp.

| Country | Reference | Dermacentor species (n) | Babesia spp. prevalence | Species of Babesia, number of isolates, prevalence (%) | Species identification method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Hodžić et al. [155] | Dermacentor reticulatus (128) | 10% | Babesia canis, 9 (7%) | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia vulpes, 4 (3%) | |||||

| Austria | Leschnik et al. [161] | D. reticulatusa (12) | 16.7% | B. canis, 2 (16.7%) | PCR sequencing |

| Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, UK | Sprong et al. [162] | D. reticulatus (1741) | 0.9% | B. canis, 16 (0.9%) | PCR sequencing |

| Belgium, the Netherlands | Jongejan et al. [139] | D. reticulatus (855) | 1.9% | B. canis, 14 (1.6%) | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia caballi, 2 (0.2%) | |||||

| France | Bonnet et al. [140] | Dermacentor marginatus (377) | 0.6% | Babesia bovis, 1 (0.3%) | PCR-RLB for selected Babesia species |

| Babesia/Theileria spp., 1 (0.3%) | |||||

| D. reticulatus (74) | 0% | - | |||

| Germany | Galfsky et al. [50] | D. reticulatus (30) | 3.3% | Babesia capreoli, 1 (3.3%) | PCR sequencing |

| Germany | Silaghi et al. [163] | D. reticulatus (301) | 0.3% | B. canis, 1 (0.3%) | PCR sequencing |

| Hungary | Hornok et al. [164] | D. reticulatus (413) | 8.2% | B. canis, 34 (8.2%) | PCR sequencing |

| Lithuania and Latvia | Radzijevskaja et al. [67] | D. reticulatus (2440) | 1.3% | B. canis, 17 | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia venatorum, 1 | |||||

| Poland | Bajer et al. [131] | D. reticulatus (29) | 3.4% | B. canis, 1 (3.4%) | PCR sequencing |

| Poland | Mierzejewska et al. [137] | D. reticulatus (2585) | 4.2% (108) | B. canis, 57 | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia microti Munich, 1 | |||||

| Poland | Wojcik-Fatla et al. [165] | D. reticulatus (468) | 4.5% | B. microti Munich, 21 (4.5%) | PCR sequencing |

| Poland | Wojcik-Fatla et al. [74] | D. reticulatus (582) | 2.7% | B. microti, 12 (2.1%) | PCR sequencing |

| B. canis, 4 (0.7%) | |||||

| Romania | Corduneanu et al. [166] | D. reticulatus (75 in 15 pools) | 8% MIR | B. canis, 6 (8% MIR) | PCR sequencing |

| Russia | Rar et al. [167] | D. reticulatus (81) | 3.6% | B. canis, 3 (3.6%) | PCR sequencing |

| Slovakia | Majláthová et al. [168] | D. reticulatus (326) | 36% | B. canis, 5 | PCR sequencing |

| Slovakia | Svehlová et al. [80] | D. reticulatus (600) | 1.8% | B. canis, 11 (1.8%) | PCR sequencing |

| Slovenia | Duh et al. [169] | D. reticulatus (100) | 1% | B. canis, 1 (1%) | PCR sequencing |

| Spain | Garcia-Sanmartin et al. [125] | D. reticulatus (97) | 5% | B. canis, 1 (1%) | PCR-RLB |

| B. caballi, 1 (1%) | |||||

| B. caballi-like, 2 (2%) | |||||

| Babesia bigemina, 1 (1%) | |||||

| Babesia divergens, 2 (2%) | |||||

| Switzerland | Schaarschmidt et al. [88] | D. reticulatus (23) | 39% | B. canis, 9 (39%) | PCR sequencing |

| Ukraine | Karbowiak et al. [170] | D. reticulatus (205) | 3.4% | B. canis, 4 | PCR sequencing |

| Ukraine | Rogovskyy et al. [90] | D. reticulatus (98) | 4% | B. canis, 1 (1%) | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia odocoilei-like, 3 (3%) | |||||

| USA | Swei et al. [144] | Dermacentor albipictus (471 questing larvae) | 7.2% | Babesia duncani (2 strains: WA1 And BH3), 34 (7.2%) | PCR sequencing |

| China | Abdallah et al. [171] | Dermacentor silvarum (84) | 4.8% | Babesia motasi-like, 3 (3.6%) | RLB, PCR sequencing |

| Babesia sp. Xinjiang, 1 (1.2%) | |||||

| Mongolia | Battsetseg et al. [153] | Dermacentor nuttalli (108 = 54 pools) | 6.5% MIR | B. caballi, 7 (6.5% MIR) | Species-specific PCR |

MIR Minimal infection rate, PCR polymerase chain reaction, RLB reverse line blot

aQuesting and feeding ticks

More evidence for the specificity of the interactions between these four Babesia species and ticks from the I. ricinus complex was obtained from data deposited in GenBank. The data are presented in Fig. 1 as percentage share of each tick species from which certain Babesia sequences were obtained. Clearly, I. ricinus and I. persulcatus are the main sources of numerous B. venatorum, B. divergens and B. capreoli sequences (95–97% of all deposited 18S rDNA sequences), and are significant sources of B. microti sequences.

Fig. 1 a–j.

Percentage share of certain tick species as the source of 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences of specific Babesia species. a 70 sequences of Babesia vogeli: from Brazil (n = 1), China (n = 5), Cuba (n = 1), Egypt (n = 4), France (n = 29), India (n = 4), Portugal (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 22), Tunisia (n = 1), Palestine (n = 2). b 41 sequences of Babesia canis: from Austria (n = 1), Hungary (n = 5), Italy (n = 2), Kazakhstan (n = 1), Latvia (n = 1), Lithuania (n = 6), Poland (n = 6), Romania (n = 3), Russia (n = 2), Serbia (n = 2), Slovakia (n = 7), Ukraine (n = 4), UK (n = 1). c 11 sequences of Babesia rossi: from Nigeria (n = 3), Turkey (n = 8). d 64 sequences of Babesia venatorum: from China (n = 3), Czech Republic (n = 4), Germany (n = 2), Japan (n = 1), Latvia (n = 6), Lithuania (n = 2), Mongolia (n = 14), Norway (n = 12), Romania (n = 1), Russia (n = 2), Slovakia (n = 1), Sweden (n = 15), Great Britain (n = 1). e Babesia bovis: four sequences from Egypt. f 34 sequences of Babesia divergens: from Belgium (n = 3), China (n = 5), Germany (n = 3), Japan (n = 14), Luxembourg (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Norway (n = 3), Russia (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 2). g 17 sequences of Babesia crassa: from China (n = 1), Hungary (n = 3), Russia (n = 1), Turkey (n = 12). h 19 sequences of Babesia capreoli: from Belgium (n = 2), Germany (n = 6), Latvia (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Norway (n = 2), Poland (n = 2), Slovakia (n = 2), South Korea (n = 1). i 102 sequences of Babesia microti: from Austria (n = 1), Belarus (n = 3), Belgium (n = 3), China (n = 2), Estonia (n = 8), Germany (n = 27), Japan (n = 4), Latvia (n = 11), Lithuania (n = 1), Luxembourg (n = 3), Mongolia (n = 21), Poland (n = 2), Russia (n = 3), Slovakia (n = 1), Sweden (n = 10), Ukraine (n = 2), USA (n = 6). j 25 sequences of Babesia caballi: from Brazil (n = 2), Bulgaria (n = 1), China (n = 7), Ethiopia (n = 1), Guinea (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), Kenya (n = 4), Malaysia (n = 3), Mongolia (n = 2)

Babesia microti is one of these four species commonly reported in I. ricinus (Additional file 2: Table S1). In many of the studies conducted at the beginning of the present century this piroplasm species was reportedly the most common one in I. ricinus ticks in Europe, although again, some of the results may be misleading as PCR products were not sequenced in any of these studies, and all positive PCR results were assumed to indicate B. microti infections. There is also a high discrepancy between the reported prevalences of B. microti in ticks (Additional file 2: Table S1). Rodents constitute the main reservoir hosts and the main source of B. microti infection for I. ricinus ticks [113–116], especially for larvae and nymphs which feed on rodents in woodland and open habitats [23, 117, 118].

Interestingly, although more species of ticks feed as juveniles on rodents, B. microti has been rarely reported in tick species other than I. ricinus, although again, B. microti DNA has been repeatedly identified in engorged ticks of different species (Ixodes trianguliceps, D. reticulatus, Haemaphysalis concinna [23, 28, 30]. Interestingly, both main B. microti strains, of which one is potentially zoonotic (US type, Jena) and the other non-zoonotic (Munich), were identified in I. ricinus ticks from different European countries and at different frequencies [30, 112, 114, 119].

Babesia microti has also been reported in other species of the I. ricinus complex, as mentioned previously (Additional file 2: Table S1; Fig. 1). Babesia microti (US type, Hobetsu, Kobe) has also been found in ticks in Japan, with a zoonotic US type identified in I. persulcatus ticks [120]. However, the most significant characteristic of this piroplasm is the role of I. scapularis as its vector in the USA, where this Babesia species is responsible for the majority of human cases, including fatal and congenital cases [121], and one of the reasons that Yang et al. [7] declared this region ‘Ground Zero’ for human babesiosis. The majority of tick studies in the USA have been focused on I. scapularis for this reason, and Babesia cf. microti has been found additionally, to date, only in one study, in two questing Amblyomma americanum ticks (Table 2). Thus, the specificity of the B. microti-I. scapularis interaction based on environmental studies in the USA is well documented (Additional file 2: Table S1) and the relevant sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database (Fig. 1i).

Table 2.

Species of Babesia reported in tick species other than Ixodes or Dermacentor spp.

| Country | Reference | Tick species (n) | Babesia spp. prevalence |

Babesia species, number of isolates and prevalence (%) |

Species identification method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic, Slovakia | Rybarova et al. [126] | Haemaphysalis concinna (150) | 4% | Babesia sp., 6 (4%) | PCR sequencing |

| USA | Shock et al. [172]a | Amblyomma americanum (184, including questing) | 3.3% | Babesia cf. microti, 2 (from questing) | PCR sequencing |

| China | Abdallah et al. [171] | Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis (242) | 13.5% | Babesia sp. Xinjiang, 32 (13.2%) | PCR-RLB, PCR sequencing |

| Babesia bovis, 1 (0.4%) | |||||

| China | Li et al. [173] | Rhipicephalus microplus (459) | 0.4% | Babesia bigemina, 2 (0.4%) | PCR sequencing |

| China | Zhuang et al. [174] | Haemaphysalis longicornis (144) | 0.7% |

Babesia sp., 1 (0.7%) |

NGS |

| China | Niu et al. [175] | Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis (188) | 21.3% | Babesia sp. Xinjiang, 40 (21.3%) | Species-specific PCR |

| Haemaphysalis longicornis (113) | 9.7% | Babesia sp. Xinjiang, 11 (9.7%) | |||

| Hungary | Hornok et al. [150] | Haemaphysalis inermis (315) | NC | Babesia crassa-like, ten pools | PCR sequencing (pools) |

| Haemaphysalis concinna (259) | NC | Babesia sp. Kh-Hc222, one pool | |||

| Babesia sp. Irk-Hc133, four pools | |||||

| Haemaphysalis punctata (61) | NC | No Babesia | |||

| Spain | Garcia-Sanmartin et al. [125] | Haemaphysalis inermis (87) | 1.1% | B. bigemina, 1 (1.1%) | PCR-RLB |

| Haemaphysalis punctata (111) | 4.5% | B. bigemina, 1 (0.9%) | |||

| B. bovis, 1 (0.9%) | |||||

| Babesia caballi, 1 (0.9%) | |||||

| B. caballi-like, 1 (0.9%) | |||||

| Babesia vulpes (Theileria annae), 1 (0.9%) | |||||

| Haemaphysalis concinna (24) | 0% | - | |||

| Rhipicephalus bursa (50) | 4% | B. caballi, 1 (2%) | |||

| Babesia ovis, 1 (2%) | |||||

| Slovakia | Hamšíková et al. [116] | Haemaphysalis concinna (91) | 6.6% | Babesia sp. 1 (Eurasia), 5 | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia sp. 2 (Eurasia), 1 | |||||

| Turkey | Brinkmann et al. [176] | Rhipicephalus bursa (76) | 1.3% | B. ovis, 1 (1.3%) | NGS |

| Turkey | Orkun et al. [151] | Haemaphysalis parva (793) | 1.6% | B. crassa, n = 8 (1%) | PCR sequencing |

| Babesia rossi, 4 (0.5%) | |||||

| Babesia sp., 1 (0.1%) | |||||

| Hyalomma marginatum (105) | 12% | Babesia occultans, 12 (11%) | |||

|

Babesia sp. tavsan 1 1 (1%) |

|||||

| Rhipicephalus turanicus (9) | 11% |

Babesia sp. tavsan 2 1 (11%) |

|||

| Israel | Harrus et al. [177] | Rhipicephalus turanicus (83 pools) | 1.2% MIR |

Babesia vogeli, one pool (1.2%) |

PCR sequencing (pools) |

| Rhipicephalus sanguineus (48 pools) | 4.2% MIR | B. vogeli, two pools (4.2%) | |||

| Hyalomma spp. (13 specimens) | 0% | - | |||

| Italy | Romiti et al. [152] | Rhipicephalus bursa (980 in 110 pools) | 14.6% pools |

B. caballi, 16 pools (14.5%) |

qPCR with TaqMan probe for B. caballi |

| Japan | Masatani et al. [178]a | Haemaphysalis formosensis (159) | 1.3% | Babesia sp. (feral raccoon strain) (1.3%) | PCR sequencing |

| Haemophysalis flava (191) | 1.6% | Babesia sp. (feral raccoon strain) (1.6%) | |||

| Haemophysalis longicornis (219) | 0% | - | |||

| Japan | Sivakumar et al. [101] | Haemophysalis longicornis (175) | 9.7% | Babesia ovata, 17 (9.7%) | Species-specific PCR for B. ovata |

| Thailand | Wattanamethanont et al. [179] | Haemaphysalis lagrangei (11,309), Haemaphysalis wellingtoni (16), Rhipicephalus microplus (859); total of 419 tick pools | 0.2% (1/419 pools) |

Babesia sp. (new), 1 (0.2% pools) |

PCR sequencing |

MIR for tick pools

NGS Next-generation sequencing, qPCR quantitative PCR, NC not calculated (pools with different number of ticks tested); for other abbreviations, see Table 1

aMostly questing, but also some feeding ticks tested together

Confirmed interactions between B. odocoilei and I. scapularis and between B. odocoilei-like and I. ricinus

In contrast to I. ricinus, in I. scapularis only one other Babesia species has been identified, B. odocoilei in ticks from Canada and the USA (Additional file 2: Table S1). In Canada, B. odocoilei was found to be the prevailing species [122–124]. This is another babesiae with deer as its main vertebrate host (American white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus) [124]. Interestingly, also in Europe, DNA of a Babesia sp. genetically similar to B. odocoilei (B. odocoilei-like or ‘deer genotype’) was detected several times in I. ricinus ticks (Additional file 2: Table S1; [21, 108]). However, this interaction needs more studies to support its relevance. In summary, molecular data from 20 years of eco-epidemiological studies support the role of I. ricinus (or I. ricinus complex) as a vector of two babesiae clades, I and X [107], associated with two groups of reservoir hosts, deer and rodents.

Unconfirmed interactions between Babesia bigemina, Babesia bovis, Babesia caballi, B. caballi-like, Babesia canis, Babesia major, Babesia ovis, Babesia vulpes and I. ricinus

The available molecular studies on questing I. ricinus ticks do not support interactions between B. bigemina, B. bovis, B. caballi, B. caballi-like, B. canis, B. major, B. ovis or B. vulpes and I. ricinus. Also, the available sequences of these Babesia species do not support the role of I. ricinus as their vector (Fig. 1). The majority of these Babesia species have been reported only in one study, which used a PCR-reverse line blot (RLB) method [125]. Considering the high number of studies on these Babesia species, together with the wide range of diagnostic methods applied (PCR sequencing, nested PCR, quantitative PCR, next-generation sequencing), it is highly probable that I. ricinus ticks are not vectors for them. The highest number of these studies concern B. canis, which was reported from the Czech Republic and Poland [126–128]. However, the authors of the first study, Rybarova et al. [126], concluded that B. canis may have been misidentified, possibly as a consequence of the short-sequence PCR product, and thus requires further investigation [126]. In Poland, a recent analysis of the distribution of D. reticulatus and outbreaks of canine babesiosis found strong geographical and temporal (seasonal) associations between them [129], which would be less likely if I. ricinus were also a competent vector of this piroplasm.

Interactions between Babesia and Dermacentor spp.

Confirmed interaction between B. canis and D. reticulatus

The ornate dog tick is both the second most common tick species in Europe and the second-best studied tick species (Table 1). Other Dermacentor species have been much less studied. Although a range of babesiae have been reported in D. reticulatus, the most common and widespread one is B. canis (Table 1), the main cause of canine babesiosis in central and north-eastern Europe [130–133]. The great majority (> 80%) of B. canis sequences originate from the tick species D. reticulatus (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the geographical range of this tick species is expanding in many European countries [129, 134, 135], and this expansion is clearly associated with the emergence of canine babesiosis, although in some tick populations DNA of B. canis has not yet been found [136, 137]. During our long-term studies (since 2012 up until the present) on the expansion of the distributions of D. reticulatus and B. canis in Poland, we have examined the highest number of questing adult ticks for Babesia spp. to date (Additional file 2: Table S1; [137]). About 100 Babesia sequences were derived from at least 200 Babesia-positive ticks, all but one identified as B. canis [32, 132, 137]. In addition, DNA of B. microti was identified in one adult D. reticulatus tick [137]. Interestingly, the opposite occurrence of these two Babesia species was found in juvenile, partially engorged D. reticulatus ticks (larvae and nymphs) collected from rodents, where B. microti constituted the majority of Babesia-positive samples, and only two samples yielded B. canis DNA [23]. As larvae and nymphs of D. reticulatus feed on rodents, and mainly on voles (Microtus and Alexandromys spp.), the key reservoir of B. microti (over 60% of voles infected in three studies [21, 30, 114]), the detection of B. microti DNA in engorged instars collected directly from these hosts is not surprising. More surprising is the apparent loss of B. microti during the moult of instars to the adult stadium, as DNA of B. microti is sporadically found in questing adult D. reticulatus ticks (Table 1). Transovarial and transstadial transmissions of B. canis in D. reticulatus ticks constitute the key routes enabling maintenance of this piroplasm in tick populations [32] and are in contrast with unsuccessful transstadial transmission of B. microti in this tick species, as can be seen in the results of the eco-epidemiological studies listed in Table 1. Thus it is highly unlikely that D. reticulatus plays any role as a vector of B. microti, and the identification of DNA of B. microti in adult ticks can be the result of the detection of blood remnants of previous stages that have fed on infected rodents [138].

The possible role of D. reticulatus as a vector of B. caballi (aetiological agent of equine babesiosis) seems questionable in light of the numerous studies (Table 1), as DNA of B. caballi was detected only once, in two questing ticks in the Netherlands [139]. The second report on B. caballi in D. reticulatus was based on PCR-RLB method [125]. In that study, many other Babesia spp. were found in D. reticulatus ticks (Tables 1, 2; Additional file 2: Table S1). However, as there is little or no support from other field studies for these findings, the role of D. reticulatus as a vector of B. bigemina or B. divergens is considered doubtful (Table 1).

Unconfirmed interactions between B. bigemina, B. caballi, B. capreoli, B. divergens, B. microti, B. odocoilei-like, B. venatorum, B. vulpes and D. reticulatus

Despite the high number of studies carried out in large geographical areas, there are only a few reports of B. bigemina, B. caballi, B. capreoli, B. divergens, B. microti, B. odocoilei-like, B. venatorum or B. vulpes in D. reticulatus (Table 1). Thus the role of this tick species as their vector is not supported by published eco-epidemiological studies.

Babesia bovis-Dermacentor marginatus interaction

The only available field study, from France [140], on questing D. marginatus ticks reported one tick infected with B. bovis (Table 1). More studies are needed on field-collected ticks from different areas where D. marginatus occurs.

Babesia duncani-Dermacentor albipictus interaction

Babesia duncani is a quite recently described species, and causes human babesiosis in western USA [141, 142]. Babesia duncani was first isolated in 1991 from a patient from Washington State, USA, and was then referred to as ‘Babesia strain WA1’ [143]. To date, there have been 12 confirmed human cases of babesiosis due to B. duncani, two presumed cases that preceded the description of B. duncani in the USA [144], and a rapidly increasing number of suspected cases in Canada [7]. Babesia duncani has not been found in questing I. scapularis (Additional file 2: Table S1). Swei et al. [144] provide evidence from their recent field study that the vector for B. duncani is the winter tick D. albipictus (Table 1), and the reservoir host is likely the mule deer Odocoileus hemionus. Interestingly, broad, overlapping ranges of these two species cover a large portion of far-western North America, where the human cases were identified. Swei et al.’s [144] study was focused on the detection of Babesia DNA in questing ticks, so the authors attempted to collect the only questing stadium in the life cycle of D. albipictus, larvae, and were able to support their research hypothesis by the detection of DNA of B. duncani in 7% of field-collected larvae. However, to further support this hypothesis, more field studies are needed.

Interactions between Babesia and Haemaphysalis spp.

Confirmed interactions between B. crassa-like and Haemaphysalis concinna and between B. crassa and Haemaphysalis parva

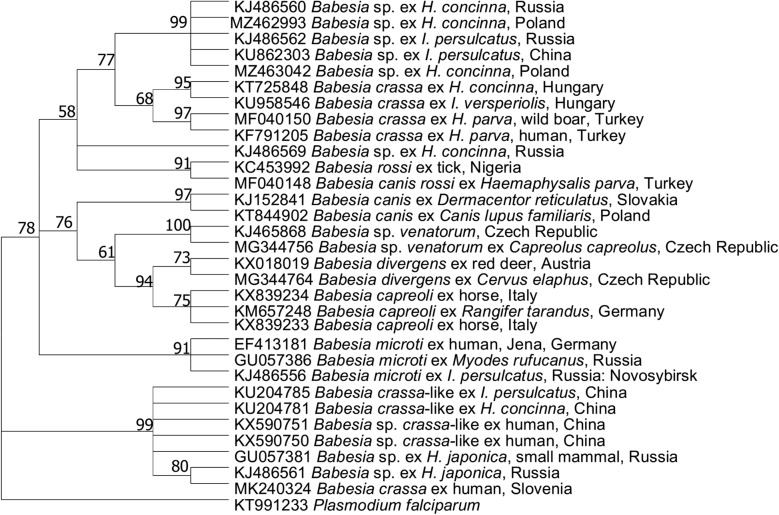

The relict tick H. concinna occurs in Europe and Asia in isolated, geographically limited locations [145]. Together with I. ricinus and D. reticulatus, H. concinna constitutes an important element of the ectoparasite community of domestic and wild animals and humans in Europe [145–147]. Although there is a rather limited number of studies on Babesia in H. concinna (Table 2), they encompass a wide geographical area, from central Europe to the Far East. Recent studies have revealed (i) a great diversity of Babesia in H. concinna; (ii) the presence of unique strains or species of Babesia, which could not be identified to species level; (iii) the wide distribution of these strains/species in the world (Table 2); and (iv) the possible role of strains/species with an increasing distribution in human babesiosis, i.e. in China [9]. We recently detected one of these strain/species in two juvenile H. concinna ticks collected from rodents in western Poland [148]. Two Babesia sequences displayed the highest similarity (97.4 and 100%) to an undescribed Babesia species from H. concinna in Russia (KJ486560). In a phylogenetic analysis using information on Babesia from H. concinna available from GenBank (Fig. 2), these two sequences grouped with a few Babesia sequences from I. persulcatus and H. concinna from Russia and China [Fig. 2; [149]; shown in Table 2 for Babesia from Hungary [150]). Interestingly, this group of sequences was the most similar (sister group) to those of the ovine piroplasm B. crassa (95.7% similarity). The third branch of the tree includes B. crassa-like sequences from both human clinical cases [9] and H. concinna ticks. According to this phylogenetic tree, at least three different species/strains of Babesia are associated with H. concinna, and are of some pathogenic potential, thus there is an urgent need for better descriptions and characterizations of babesiae from H. concinna.

Fig. 2.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of 18S rDNA of selected Babesia spp. (550 base pairs). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method and the Kimura two-parameter model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (− 2752,03) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbour-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood approach, and then selecting the topology with a superior log likelihood value. A discrete γ distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [five categories (+ G, parameter = 2,1600)]. This analysis involved 32 nucleotide sequences. There were a total of 458 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X

Interestingly, the majority (71%) of sequences of ovine piroplasm B. crassa deposited in GenBank originated from H. parva, a well-established vector of this species [1], with some share of other Haemaphysalis and Ixodes spp. (Fig. 1). This interaction was also reported in a recent study from Turkey ([151]; Table 2). This pattern suggests that, although H. parva is a vector of B. crassa, H. concinna is a vector of B. crassa-like species, a likely parasite of free-living ungulates [149]. Additionally, B. crassa-like was also identified in one Haemaphysalis inermis from Hungary [150].

Interactions between Babesia sp. Xinjiang and Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis or Haemaphysalis longicornis

In two recent studies from China, new zoonotic Babesia sp. Xinjiang was found in 13% of H. qinghaiensis (Table 2). The prevalence was also similar in H. longicornis, so it is likely that these two Haemaphysalis spp. can act as vectors for this species, although more field studies are needed to confirm these interactions.

Interactions between Babesia and other tick species

As can be seen in Table 2, there are only a few studies on Babesia in other tick species (questing ticks) despite the availability of suitable molecular techniques (reviewed in [22]). This is partially due to the difficulty of obtaining questing individuals of tick species with life cycles that involve one or two host species, like Rhipicephalus microplus or Hyalomma spp. Studies on the genera Rhipicephalus and Hyalomma are mainly focused on feeding ticks, and thus do not provide strong evidence on their role as vectors.

Confirmed and unconfirmed interactions between Babesia and other tick species based on GenBank data

The majority of molecular data (18S rDNA) derived from GenBank confirmed the expectations that arose from earlier experimental studies and field observations (summarized in [1]), and reflect specificity in Babesia-tick vector interactions. In the case of Babesia vogeli, the majority (96%) of sequences originated from R. sanguineus s.l. (Fig. 1a); both H. parva (73%) and Haemaphysalis leachi (27%) constituted the source of B. rossi (Fig. 1b), and B. canis originated mostly from D. reticulatus (Fig. 1c), as mentioned previously. Sequences of B. bovis were derived only from R. annulatus (Fig. 1e).

However, in the case of B. caballi, with ten tick species assigned to deposited 18S rDNA sequences of this species, there is no evidence of any established interaction (Fig. 1j). Of these ten species, four are Rhipicephalus species, three Dermacentor spp. (but not D. reticulatus), two Hyalomma spp. and one Amblyomma. In two recent studies, B. caballi was found in 16 pools of R. bursa in Italy (Table 2; [152]) and in seven D. nuttalli from Mongolia [153]. Such a variety of tick species might reflect the ability of B. caballi to adapt to transmission in parts of the world where horses are bred and/or our inability to determine the main vector for this Babesia species. These days, because anti-tick treatments (acaricides, vaccines [3]) can easily be applied to animals of economic significance (horses, cattle, sheep), Babesia species specific for these hosts may have been partially eliminated and thus hard to find in their vectors.

A similar problem concerning the determination of tick vectors exists for the recently described B. vulpes, a common parasite of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Europe [154]. There are not many sequences of B. vulpes derived from ticks in GenBank, although at least six tick species, I. ricinus, Ixodes canisuga, Ixodes hexagonus, Ixodes kaiseri, D. reticulatus and H. punctata, have been identified as vectors of this species [29, 125]. Babesia vulpes was found in one study in four D. reticulatus in Austria [155], and in another study in one I. ricinus and one H. punctata in Spain [125]. As can be seen from the data discussed here, there is little evidence from eco-epidemiological studies that I. ricinus, D. reticulatus or H. concinna constitute the main vector of B. vulpes. The apparent scarcity of data from the most common tick species, together with one of the highest prevalences of this species of Babesia in foxes (30–60%), suggests that nidicolous tick species associated with red foxes, such as I. hexagonus or I. canisuga [29, 156], are its main vectors. Interestingly, dogs are sporadically found infested with I. hexagonus [157], and a few cases of babesiosis due to B. vulpes have been also recorded in dogs [5, 154]. Due to their nidicolous habit, it would be problematic to collect unfed ticks of these species and either confirm or exclude their role as vectors of B. vulpes.

New Babesia species and their vectors

Few studies have been carried out on tick species other than the three most studied ones (Table 2). However, these studies often reveal new Babesia species or strains, e.g. in studies carried out in Turkey, Japan and Thailand (Table 2). These interesting findings should encourage researchers to continue, and expand on, such studies to increase the number of new species described. More records of new Babesia species/strains in association with certain tick species are needed to recognize new Babesia-vector interactions.

Detection of Babesia spp. in ticks from hosts

There are numerous studies reporting Babesia spp. in ticks collected from their hosts, especially ticks collected from dogs, cattle, animals that are hunted (i.e. deer or foxes), birds or small mammals [23, 25, 26, 29, 31, 158]. As mentioned at the beginning of this review, and also in many other reviews [19], the results of such studies can be inconclusive or misleading if no control of host infection is performed at the time of tick collection. When ticks are collected from species of rodents in which Babesia infections are common [114, 159, 160], these ticks, regardless of the species, may contain pathogen DNA (‘meal contamination’ [23]). The detection of DNA of certain Babesia sp. in engorged/partially engorged ticks should be treated with caution and considered in the light of a possible reservoir role of the vertebrate host for the Babesia species in question. As mentioned above, the detection of B. microti in a high percentage of D. reticulatus larvae feeding on voles does not actually support the role of this tick as a vector of B. microti because the parasite is apparently lost during the moult of the tick. Similarly, the detection of any Babesia species known to be associated with dogs in ticks collected from dogs (i.e. B. canis in I. ricinus) should be treated as an accidental finding, not as the discovery of a new Babesia—tick vector interaction. Regarding B. vulpes, DNA of this piroplasm has been identified in three tick species (I. ricinus, I. hexagonus, I. canisuga) collected from foxes, while the prevalence of B. vulpes in foxes was close to 50% [29]. Determination of the presence of a pathogen in a tick collected from a certain host may provide very useful information; however, this information should not be used as proof that the tick in question is a vector of that particular pathogen.

Conclusions

The application of molecular methods in eco-epidemiological studies may help researchers to identify specific interactions between certain Babesia and tick species. Well-supported data for the most common Babesia and tick species, i.e. I. ricinus, I. scapularis, I. persulcatus and D. reticulatus, have been reported during the past 20 years. Published findings on Babesia-tick associations have provided evidence for specific interactions, and also complemented experimental transmission studies because they reflect the actual epidemiological situation in certain habitats, e.g. the actual health hazard constituted by certain Babesia and tick species in certain locations. It is worth underlining the importance of the correct choice of methods for studies on Babesia-tick interactions. These methods should enable both the detection and accurate identification of a wide range of Babesia species in ticks. There are presently many methods/techniques that can be used to perform such studies [22]. The wide use of combined PCR and sequencing methods has enabled the identification/confirmation of new or lesser known species of Babesia, such as B. venatorum and B. capreoli, in the widely studied I. ricinus tick. The same methods enabled the identification of new strains/species of Babesia in less-studied tick species, such as H. concinna, Haemophysalis flava and Rhipicephalus turanicus (Table 2). The massive amount of data collected thus far for the most common tick species should be complemented by more intensive studies on Babesia infection in underrepresented tick species.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Text S1. Range of this review.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Species of Babesia reported in Ixodes spp.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Ms Caroline Rust, UK, for the proofreading of a previous version of this article.

Abbreviations

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- rDNA

Ribosomal DNA

- RLB

Reverse line blot

Authors’ contributions

DDS: data collection and analysis, phylogenetic analysis, drafting the manuscript; AB: conceptualization, data collection, drafting the manuscript, project funding. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science Centre Sonata Bis grant no. 2014/14/E/NZ7/00153 (AB).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anna Bajer, Email: anabena@biol.uw.edu.pl.

Dorota Dwużnik-Szarek, Email: dorota.dwuznik@biol.uw.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Gray JS, Estrada-Peña A, Zintl A. Vectors of babesiosis. Annu Rev Entomol. 2019;64:149–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011118-111932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock R, Jackson L, de Vos A, Jorgensen W. Babesiosis of cattle. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl):S247–S269. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004005190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkenheuer AJ, Buch J, Beall MJ, Braff J, Chandrashekar R. Global distribution of canine Babesia species identified by a commercial diagnostic laboratory. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2020;22:100471. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solano-Gallego L, Sainz Á, Roura X, Estrada-Pena A, Guadalupe M. A review of canine babesiosis: the European perspective. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:336. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penzhorn BL. Don't let sleeping dogs lie: unravelling the identity and taxonomy of Babesia canis, Babesia rossi and Babesia vogeli. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:184. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04062-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y, Christie J, Köster L, Du A, Yao C. Emerging human babesiosis with "Ground Zero" in North America. Microorganisms. 2021;9:440. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott JD, Scott CM. Human babesiosis caused by Babesia duncani has widespread distribution across Canada. Healthcare (Basel) 2018;6:49. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia N, Zheng YC, Jiang JF, Jiang RR, Jiang BG, Wei R, et al. Human babesiosis caused by a Babesia crassa-like pathogen: a case series. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;14:1110–1119. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou X, Li SG, Wang JZ, Huang JL, Zhou HJ, Chen JH, Zhou XN. Emergence of human babesiosis along the border of China with Myanmar: detection by PCR and confirmation by sequencing. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2014;3:e55. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang JF, Zheng YC, Jiang RR, Li H, Huo QB, Jiang BG, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of 48 cases of “Babesia venatorum” infection in China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:196–203. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi C, Zhou D, Liu J, Cheng Z, Zhang L, Wang L, et al. Detection of Babesia divergens using molecular methods in anemic patients in Shandong Province. China Parasitol Res. 2011;109:241–245. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl):S3–14. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004005967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onyiche TE, Răileanu C, Fischer S, Silaghi C. Global distribution of Babesia species in questing ticks: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on published literature. Pathogens. 2021;10:230. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adl SM, Simpson AGB, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, et al. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2012;59:429–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, et al. Revisions to the classification, nomenclature, and diversity of eukaryotes. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2019;66:4–119. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zahler M, Schein E, Rinder H, Gothe R. Characteristic genotypes discriminate between Babesia canis isolates of differing vector specificity and pathogenicity to dogs. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:544–548. doi: 10.1007/s004360050445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahler M, Rinder H, Schein E, Gothe R. Detection of a new pathogenic Babesia microti-like species in dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2000;89:241–248. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estrada-Peña A, Cevidanes A, Sprong H, Millán J. Pitfalls in tick and tick-borne pathogens research, some recommendations and a call for data sharing. Pathogens. 2021;10:712. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10060712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisen L. Vector competence studies with hard ticks and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes: a review. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101359. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azagi T, Jaarsma RI, van Leeuwen AD, Fonville M, Maas M, Franssen FJ, et al. Circulation of Babesia species and their exposure to humans through Ixodes ricinus. Pathogens. 2021;10:386. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10040386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-García G, Santamaría-Espinosa RM, Lira-Amaya JJ, Figueroa JV. Challenges in tick-borne pathogen detection: the case for Babesia spp. identification in the tick vector. Pathogens. 2021;10:92. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwużnik D, Mierzejewska EJ, Drabik P, Kloch A, Alsarraf M, Behnke JM, et al. The role of juvenile Dermacentor reticulatus ticks as vectors of microorganisms and the problem of ‘meal contamination’. Exp Appl Acarol. 2019;78:181–202. doi: 10.1007/s10493-019-00380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adamska M, Skotarczak B. Molecular detecting of piroplasms in feeding and questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Ann Parasitol. 2017;63:21–26. doi: 10.17420/ap6301.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maia C, Ferreira A, Nunes M, Vieira ML, Campino L, Cardoso L. Molecular detection of bacterial and parasitic pathogens in hard ticks from Portugal. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reye AL, Arinola OG, Hübschen JM, Muller CP. Pathogen prevalence in ticks collected from the vegetation and livestock in Nigeria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2562–2568. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06686-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reye AL, Stegniy V, Mishaeva NP, Velhin S, Hübschen JM, Ignatyev G, et al. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from different geographical locations in Belarus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bown KJ, Lambin X, Telford GR, Ogden NH, Telfer S, Woldehiwet Z, et al. Relative importance of Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes trianguliceps as vectors for Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti in field vole. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7118–7125. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00625-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Najm NA, Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Herb I, Fensterer V, Pfister K, et al. A molecular survey of Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and their ticks from Thuringia, Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welc-Falęciak R, Bajer A, Behnke JM, Siński E. Effects of host diversity and the community composition of hard ticks (Ixodidae) on Babesia microti infection. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levytska VA, Mushinsky AB, Zubrikova D, Blanarova L, Długosz E, Vichova B, et al. Detection of pathogens in ixodid ticks collected from animals and vegetation in five regions of Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021;12:101586. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mierzejewska EJ, Dwużnik D, Bajer A. Molecular study of transovarial transmission of Babesia canis in the Dermacentor reticulatus tick. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018;25:669–671. doi: 10.26444/aaem/94673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blaschitz M, Narodoslavsky-Gföller M, Kanzler M, Stanek G, Walochnik J. Babesia species occurring in Austrian Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4841–4846. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00035-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lempereur L, Lebrun M, Cuvelier P, Sépult G, Caron Y, Saegerman C, et al. Longitudinal field study on bovine Babesia spp. and Anaplasma phagocytophilum infections during a grazing season in Belgium. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1525–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Václavík T, Balážová A, Baláž V, Tkadlec E, Schichor M, Zechmeisterová K, et al. Landscape epidemiology of neglected tick-borne pathogens in central Europe. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68:1685–1696. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venclíková K, Mendel J, Betášová L, Blažejová H, Jedličková P, Straková P, et al. Neglected tick-borne pathogens in the Czech Republic, 2011–2014. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudolf I, Golovchenko M, Sikutová S, Rudenko N, Grubhoffer L, Hubálek Z. Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) in nymphal Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Czech Republic. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 2005;52:274–276. doi: 10.14411/fp.2005.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klitgaard K, Kjær LJ, Isbrand A, Hansen MF, Bødker R. Multiple infections in questing nymphs and adult female Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in a recreational forest in Denmark. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sormunen JJ, Andersson T, Aspi J, Bäck J, Cederberg T, Haavisto N, et al. Monitoring of ticks and tick-borne pathogens through a nationwide research station network in Finland. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101449. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sormunen JJ, Klemola T, Hänninen J, Mäkelä S, Vuorinen I, Penttinenet R, et al. The importance of study duration and spatial scale in pathogen detection-evidence from a tick-infested island. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7:189. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akl T, Bourgoin G, Souq ML, Appolinaire J, Poirel MT, Gibert P, et al. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus in the French Pyrenees and first identification of Rickettsia monacensis in France. Parasite. 2019;26:20. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2019019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonnet S, Michelet L, Moutailler S, Cheval J, Hébert C, Vayssier-Taussat M, Eloit M. Identification of parasitic communities within European ticks using next-generation sequencing. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jouglin M, Perez G, Butet A, Malandrin L, Bastian S. Low prevalence of zoonotic Babesia in small mammals and Ixodes ricinus in Brittany, France. Vet Parasitol. 2017;30:58–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebert I, Agoulon A, Bastian S, Butet A, Cargnelutti B, Cèbe N, et al. Distribution of ticks, tick-borne pathogens and the associated local environmental factors including small mammals and livestock, in two French agricultural sites: the OSCAR database. Biodivers Data J. 2020;5:e50123. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e50123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paul REL, Cote M, Le Naour E, Bonet SI. Environmental factors influencing tick densities over seven years in a French suburban forest. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:309. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reis C, Cote M, Paul RE, Bonnet S. Questing ticks in suburban forest are infected by at least six tick-borne pathogens. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:907–916. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lejal E, Moutailler S, Šimo L, Vayssier-Taussat M, Pollet T. Tick-borne pathogen detection in midgut and salivary glands of adult Ixodes ricinus. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:152. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franke J, Fritzsch J, Tomaso H, Straube E, Dorn W, Hildebrandt A. Coexistence of pathogens in host-seeking and feeding ticks within a single natural habitat in central Germany. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6829–6836. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01630-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franke J, Hildebrandt A, Meier F, Straube E, Dorn W. Prevalence of Lyme disease agents and several emerging pathogens in questing ticks from the German Baltic coast. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:441–444. doi: 10.1603/ME10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galfsky D, Król N, Pfeffer M, Obiegala A. Long-term trends of tick-borne pathogens in regard to small mammal and tick populations from Saxony, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:131. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3382-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hildebrandt A, Franke J, Schmoock G, Pauliks K, Krämer A, Straube E. Diversity and coexistence of tick-borne pathogens in central Germany. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:651–655. doi: 10.1603/ME10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hildebrandt A, Fritzsch J, Franke J, Sachse S, Dorn W, Straube E. Co-circulation of emerging tick-borne pathogens in Middle Germany. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:533–537. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Overzier E, Pfister K, Thiel C, Herb I, Mahling M, Silaghi C. Diversity of Babesia and Rickettsia species in questing Ixodes ricinus: a longitudinal study in urban, pasture, and natural habitats. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:559–564. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Overzier E, Pfister K, Herb I, Mahling M, Böck G, Jr, Silaghi C. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), in questing ticks (Ixodes ricinus), and in ticks infesting roe deer in southern Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Springer A, Höltershinken M, Lienhart F, Ermel S, Rehage J, Hülskötter K, et al. Emergence and epidemiology of bovine babesiosis due to Babesia divergens on a northern German beef production farm. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:649. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schorn S, Pfister K, Reulen H, Mahling M, Silaghi C. Occurrence of Babesia spp, Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Bavarian public parks, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2011;15:135. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eshoo MW, Crowder CD, Carolan HE, Rounds MA, Ecker DJ, Haag H, et al. Broad-range survey of tick-borne pathogens in southern Germany reveals a high prevalence of Babesia microti and a diversity of other tick-borne pathogens. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:584–591. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartelt K, Oehme R, Frank H, Brockmann SO, Hassler D, Kimmig P. Pathogens and symbionts in ticks: prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ehrlichia sp.), Wolbachia sp., Rickettsia sp., and Babesia sp. in southern Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hildebrandt A, Pauliks K, Sachse S, Straube E. Coexistence of Borrelia spp. and Babesia spp. in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Middle Germany. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:831–837. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Egyed L, Elő P, Sréter-Lancz Z, Széll Z, Balogh Z, Sréter T. Seasonal activity and tick-borne pathogen infection rates of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Hungary. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aureli S, Galuppi R, Ostanello F, Foley JE, Bonoli C, Rejmanek D, et al. Abundance of questing ticks and molecular evidence for pathogens in ticks in three parks of Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22:459–466. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1167714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Capelli G, Ravagnan S, Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Cazzin S, Porcellato E, et al. Occurrence and identification of risk areas of Ixodes ricinus-borne pathogens: a cost-effectiveness analysis in north-eastern Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2012;27:61. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cassini R, Bonoli C, Montarsi F, Tessarin C, Marcer F, Galuppi R. Detection of Babesia EU1 in Ixodes ricinus ticks in northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Floris R, Cecco P, Mignozzi K, Boemo B, Cinco M. First detection of Babesia EU1 and Babesia divergens-like in Ixodes ricinus ticks in north-eastern Italy. Parassitologia. 2009;51:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zanet S, Ferroglio E, Battisti E, Tizzani P. Ecological niche modeling of Babesia sp. infection in wildlife experimentally evaluated in questing Ixodes ricinus. Geospat Health. 2020;15(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Capligina V, Berzina I, Bormane A, Salmane I, Vilks K, Kazarina A, et al. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of Babesia spp. in Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Latvia. Exp Appl Acarol. 2016;68:325–336. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radzijevskaja J, Mardosaitė-Busaitienė D, Aleksandravičienė A, Paulauskas A. Investigation of Babesia spp. in sympatric populations of Dermacentor reticulatus and Ixodes ricinus ticks in Lithuania and Latvia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reye AL, Hübschen JM, Sausy A, Muller CP. Prevalence and seasonality of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Luxembourg. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2923–2931. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03061-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Øines Ø, Radzijevskaja J, Paulauskas A, Rosef O. Prevalence and diversity of Babesia spp. in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Norway. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pieniazek N, Sawczuk M, Skotarczak B. Molecular identification of Babesia parasites isolated from Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in northwestern Poland. J Parasitol. 2006;92:32–35. doi: 10.1645/GE-541R2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siński E, Bajer A, Welc R, Pawełczyk A, Ogrzewalska M, Behnke JM. Babesia microti: prevalence in wild rodents and Ixodes ricinus ticks from the Mazury Lakes District of north-eastern Poland. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sytykiewicz H, Karbowiak G, Hapunik J, Szpechciński A, Supergan-Marwicz M, Goławska S, et al. Molecular evidence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti co-infections in Ixodes ricinus ticks in central-eastern region of Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welc-Falęciak R, Bajer A, Paziewska-Harris A, Baumann-Popczyk A, Siński E. Diversity of Babesia in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Poland. Adv Med Sci. 2012;57:364–369. doi: 10.2478/v10039-012-0023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Sawczyn A, Cisak E, Dutkiewicz J. Babesia spp. in questing ticks from eastern Poland: prevalence and species diversity. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:3111–3116. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rar VA, Epikhina TI, Livanova NN, Panov VV. Genetic diversity of Babesia in Ixodes persulcatus and small mammals from north Ural and west Siberia, Russia. Parasitology. 2011;138:175–182. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Movila A, Dubinina HV, Sitnicova N, Bespyatova L, Uspenskaia I, Efremova G, et al. Comparison of tick-borne microorganism communities in Ixodes spp. of the Ixodes ricinus species complex at distinct geographical regions. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014;63:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10493-013-9761-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karlsson ME, Andersson MO. Babesia species in questing Ixodes ricinus, Sweden. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Potkonjak A, Gutiérrez R, Savić S, Vračar V, Nachum-Biala Y, Jurišić A, et al. Molecular detection of emerging tick-borne pathogens in Vojvodina, Serbia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blaňarová L, Stanko M, Miklisová D, Víchová B, Mošanský L, Kraljik J, et al. Presence of Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis and Babesia microti in rodents and two tick species (Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes trianguliceps) in Slovakia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Svehlová A, Berthová L, Sallay B, Boldiš V, Sparagano OA, Spitalská E. Sympatric occurrence of Ixodes ricinus, Dermacentor reticulatus and Haemaphysalis concinna ticks and Rickettsia and Babesia species in Slovakia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duh D, Petrovec M, Avsic-Zupanc T. Diversity of Babesia infecting European sheep ticks (Ixodes ricinus) J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3395–3397. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3395-3397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Remesar S, Díaz P, Prieto A, García-Dios D, Panadero R, Fernández G, et al. Molecular detection and identification of piroplasms (Babesia spp. and Theileria spp.) and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing ticks from northwest Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2021;35:51–58. doi: 10.1111/mve.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burri C, Dupasquier C, Bastic V, Gern L. Pathogens of emerging tick-borne diseases, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia spp., and Babesia spp., in Ixodes ticks collected from rodents at four sites in Switzerland (canton of Bern) Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:939–944. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Casati S, Sager H, Gern L, Piffaretti J. Presence of potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. for human in Ixodes ricinus in Switzerland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006;13:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gigandet L, Stauffer E, Douet V, Rais O, Moret J, Gern L. Prevalence of three zoonotic Babesia species in Ixodes ricinus (Linné, 1758) nymphs in a suburban forest in Switzerland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:363–366. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lommano E, Bertaiola L, Dupasquier C, Gern L. Infections and coinfections of questing Ixodes ricinus ticks by emerging zoonotic pathogens in western Switzerland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4606–4612. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07961-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oechslin CP, Heutschi D, Lenz N, Tischhauser W, Péter O, Rais O, et al. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in urban and suburban areas of Switzerland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:558. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2500-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schaarschmidt D, Gilli U, Gottstein B, Marreros N, Kuhnert P, Daeppen JA, et al. Questing Dermacentor reticulatus harbouring Babesia canis DNA associated with outbreaks of canine babesiosis in the Swiss Midlands. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Didyk YM, Blaňárová L, Pogrebnyak S, Akimov I, Peťko B, Víchová B. Emergence of tick-borne pathogens (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ricketsia raoultii and Babesia microti) in the Kyiv urban parks, Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(2):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rogovskyy A, Batool M, Gillis DC, Holman PJ, Nebogatkin IV, Rogovska YV, et al. Diversity of Borrelia spirochetes and other zoonotic agents in ticks from Kyiv, Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aliota MT, Dupuis AP, Wilczek MP, Peters RJ, Ostfeld RS, Kramer LD. The prevalence of zoonotic tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes scapularis collected in the Hudson Valley, New York State. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:245–250. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edwards MJ, Russell JC, Davidson EN, Yanushefski TJ, Fleischman BL, Heist RO, et al. A 4-yr survey of the range of ticks and tick-borne pathogens in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania. J Med Entomol. 2019;56:1122–1134. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Edwards MJ, Barbalato LA, Makkapati A, Pham KD, Bugbee LM. Relatively low prevalence of Babesia microti and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hersh MH, Ostfeld RS, McHenry DJ, Tibbetts M, Brunner JL, Killilea ME, et al. Co-infection of blacklegged ticks with Babesia microti and Borrelia burgdorferi is higher than expected and acquired from small mammal hosts. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hutchinson ML, Strohecker MD, Simmons TW, Kyle AD, Helwig MW. Prevalence rates of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae), and Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) in host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) from Pennsylvania. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:693–698. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjv037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Milholland MT, Xu G, Rich SM, Machtinger ET, Mullinax JM, Li AY. Pathogen coinfections harbored by adult Ixodes scapularis from white-tailed deer compared with questing adults across sites in Maryland, USA. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021;21:86–91. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2020.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Prusinski MA, Kokas JE, Hukey KT, Kogut SJ, Lee J, Backenson PB. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae), and Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from recreational lands in the Hudson Valley Region, New York State. J Med Entomol. 2014;51:226–236. doi: 10.1603/ME13101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Steiner FE, Pinger RR, Vann CN, Grindle N, Civitello D, Clay K, Fuqua C. Infection and co-infection rates of Anaplasma phagocytophilum variants, Babesia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi, and the rickettsial endosymbiont in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) from sites in Indiana, Maine, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:289–297. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/45.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Steiner FE, Pinger RR, Vann CN, Abley MJ, Sullivan B, Grindle N, et al. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia odocoilei DNA in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) collected in Indiana. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:437–442. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/43.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scott JD, Pascoe EL, Sajid MS, Foley JE. Detection of Babesia odocoilei in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in southern Ontario, Canada. Pathogens. 2021;10:327. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sivakumar T, Tattiyapong M, Okubo K, Suganuma K, Hayashida K, Igarashi I, et al. PCR detection of Babesia ovata from questing ticks in Japan. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zamoto-Niikura A, Morikawa S, Hanaki KI, Holman PJ, Ishihara C. Ixodes persulcatus ticks as vectors for the Babesia microti U.S. lineage in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:6624–6632. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02373-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karnath C, Obiegala A, Speck S, Essbauer S, Derschum H, Scholz H, et al. Detection of Babesia venatorum, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis in Ixodes persulcatus ticks from Mongolia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tuvshintulga B, Sivakumar T, Battsetseg B, Narantsatsaral SO, Enkhtaivan B, Battur B, et al. The PCR detection and phylogenetic characterization of Babesia microti in questing ticks in Mongolia. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Herwaldt BL, Cacciò S, Gherlinzoni F, Aspöck H, Slemenda SB, Piccaluga P, et al. Molecular characterization of a non–Babesia divergens organism causing zoonotic babesiosis in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:942–948. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.020748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Malandrin L, Jouglin M, Sun Y, Brisseau N, Chauvin A. Redescription of Babesia capreoli (Enigk and Friedhoff, 1962) from roe deer (Capreolus capreolus): isolation, cultivation, host specificity, molecular characterisation and differentiation from Babesia divergens. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]