Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). CVD risk scores underestimate risk in this population as CVD is driven by clustering of traditional and non-traditional risk factors, which lead to prognostic pathological changes in cardiovascular structure and function. While exercise may mitigate CVD in this population, evidence is limited, and physical activity levels and patient activation towards exercise and self-management are low. This pilot study will assess the feasibility of delivering a structured, home-based exercise intervention in a population of KTRs at increased cardiometabolic risk and evaluate the putative effects on cardiovascular structural and functional changes, cardiorespiratory fitness, quality of life, patient activation, healthcare utilisation and engagement with the prescribed exercise programme.

Methods and analysis

Fifty KTRs will be randomised 1:1 to: (1) the intervention; a 12week, home-based combined resistance and aerobic exercise intervention; or (2) the control; usual care. Intervention participants will have one introductory session for instruction and practice of the recommended exercises prior to receiving an exercise diary, dumbbells, resistance bands and access to instructional videos. The study will evaluate the feasibility of recruitment, randomisation, retention, assessment procedures and the intervention implementation. Outcomes, to be assessed prior to randomisation and postintervention, include: cardiac structure and function with stress perfusion cardiac MRI, cardiorespiratory fitness, physical function, blood biomarkers of cardiometabolic health, quality of life and patient activation. These data will be used to inform the power calculations for future definitive trials.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol was reviewed and given favourable opinion by the East Midlands-Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference: 19/EM/0209; 14 October 2019). Results will be published in peer-reviewed academic journals and will be disseminated to the patient and public community via social media, newsletter articles and presentations at conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: renal transplantation, cardiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data on the effects of exercise interventions on the cardiac structural and functional aspects of cardiovascular disease in this population are lacking and baseline values of multiparametric cardiac MRI in kidney transplant recipients are previously undefined.

This study uses a novel home-based exercise intervention with the potential to translate into a widespread, low-resource intervention compared with in-centre, supervised interventions that are costly and labour intensive.

As it can be difficult to ensure control groups are not influenced to change their lifestyle as a result of being part of the study, control participants will be offered the intervention after completion of the study.

This study will provide quantitative and qualitative feasibility and pilot data to inform a definitive randomised controlled trial that will explore longer term engendered lifestyle change in this population in response to a complex, home-based, lifestyle intervention.

Secondary outcome analysis will identify the putative cardiometabolic and muscular effects of the intervention, although these results would need confirming in adequately powered studies due to the small sample size of this pilot study.

Background

Kidney transplantation is the preferred modality of renal replacement therapy for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Although kidney transplantation confers a significant survival advantage over remaining on dialysis,1 cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity, mortality and graft loss.2–4 Since 2015, mortality rates attributed to CVD have been rising.4 CVD in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) associates with traditional cardiometabolic risk factors,3 5 6 which drive classical atheromatous coronary artery disease, and non-traditional risk factors resulting in pathological changes in cardiovascular structure and function that associate with mortality.7 Immunosuppressive agents are well known to drive traditional3 and non-traditional cardiometabolic risk factors.8 9 Non-traditional cardiometabolic risk factors, including endothelial dysfunction, systemic inflammation, acute rejection, anaemia and deranged bone mineral metabolism,10–12 are of at least equal importance in the pathogenesis of CVD in KTRs.7 This is further illustrated by the fact that traditional CVD risk stratification tools dramatically underestimate cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).11 13–15 Coronary revascularisation does not improve outcomes for KTRs as it does in the general population12 and cardiac events are more likely to be fatal in KTRs.16

CKD-related cardiomyopathy, which has been termed ‘Uremic Cardiomyopathy’, is characterised by stereotypical changes in the cardiovascular structure and function of the heart such as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricular dilatation, left ventricular systolic dysfunction,17 myocardial fibrosis18 and aortic stiffness,19 all of which relate to poor cardiovascular outcomes.20 21 Although structural and functional improvements of the heart and vessels have been seen post-transplantation in some studies,22 others have shown no regression23 and parameters such as LVH are independent factors for cardiac failure and mortality in KTRs.15 Cardiac MRI (CMR) is the gold standard for assessment of ventricular structure and function and we have shown methods for assessment of tissue characterisation, aortopathy and subclinical systolic and diastolic function to be reproducible in patients with kidney disease,24–26 making CMR the ideal imaging modality for assessing multiple aspects of prognostically relevant measures of CVD in clinical studies.

Numerous epidemiological studies have observed the association between low levels of physical activity and increased prevalence of CVD risk factors,27–29 and an inverse relationship between physical activity and all-cause and CVD mortality.30 31 Physical activity levels in KTRs are lower than the general population,32–34 with only 27% classified as meeting the UK national recommended physical activity levels.35 While physical activity levels improve in the year following transplantation, they plateau after 1 year.33 In the general population, lifestyle changes that increase physical activity through structured exercise lower mortality.36 37 Despite this evidence, there is a lack of rigorous research into the role of increased physical activity in mitigating cardiovascular risk in KTRs.38 Recent consensus recommendations from experts and stakeholders highlighted the need for a priority research agenda in exercise for solid organ transplant recipients to improve cardiovascular outcomes in this patient population.39 While supervised exercise interventions in KTRs improve cardiorespiratory fitness and a variety of traditional and non-traditional risk factors for CVD, including metabolic profile,40–42 strength,43 vascular stiffening,41 weight44 and inflammation,45 they are not realistically deliverable in the current financial climate and have not translated to clinical practice. Furthermore, exercise habits following in-centre supervised programmes are not maintained46–48 which can be potentially attributed to low levels of patient activation (a measure of a person’s skills, confidence and knowledge to manage their own health) and a failure for such programmes to engender sustained lifestyle changes.49 50 Home-based exercise training programmes have been shown to be deliverable in patients on dialysis and patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation,51–54 but the effectiveness and deliverability of home-based exercise interventions are largely untested in KTRs. It cannot be assumed that such programmes will be acceptable to KTRs, whose home lives and social and occupational circumstances are significantly different from dialysis and cardiac patients. Many KTRs have had enforced sedentary lifestyles prior to transplantation as dialysis patients and their goals for rehabilitation as well as the disease processes at work may be different.55 56

Objectives

The aims of this study are to evaluate the impact of a 12week, home-based exercise intervention in KTRs with increased cardiometabolic risk, specifically addressing:

The deliverability and feasibility of the home-based exercise intervention in KTRs, defining recruitment, retention, compliance and adverse events (AE).

Potential cardiovascular structural and functional parameters measured using stress perfusion CMR.

Cardiorespiratory fitness and strength.

Biochemical markers of cardiometabolic health, body composition, physical function and quality of life.

Patient activation and continued adherence to the prescribed home-based exercise programme.

Two substudies will assess:

The acceptability of the intervention through qualitative semistructured interviews postintervention.

The differences between cardiorespiratory fitness in ‘healthy controls’ without a kidney transplant versus KTRs.

Methods and analysis

ECSERT trial design

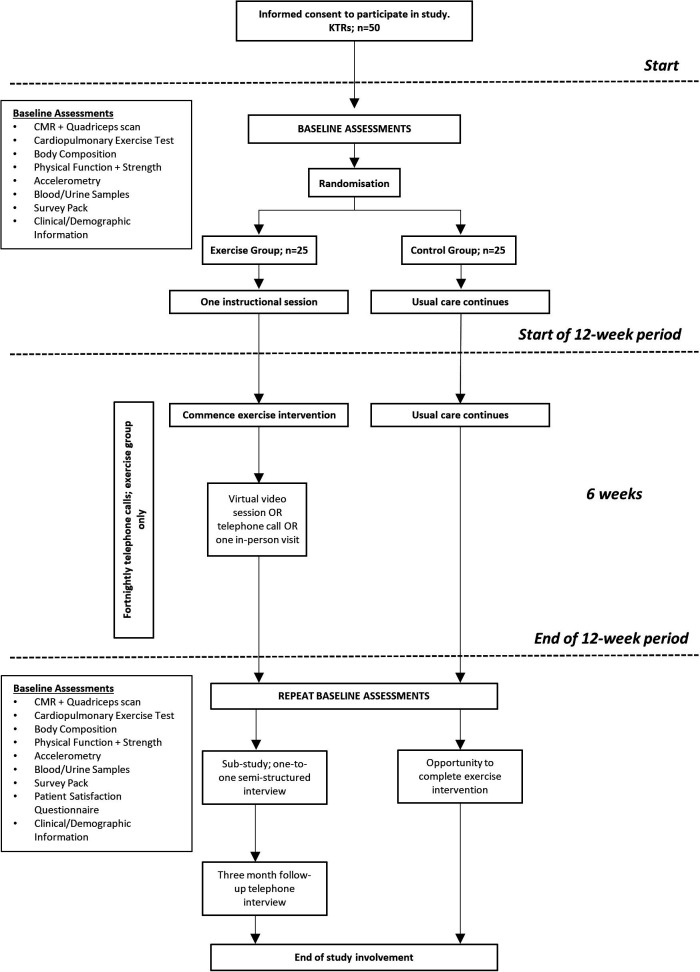

This study is a prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint pilot study. The study flow chart is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

ECSERT study flow diagram. CMR, cardiac MRI; KTR, kidney transplant recipient.

Participant identification and recruitment

Fifty KTRs with a stable kidney transplant of >1 year will be recruited from University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (UHL) kidney transplant outpatient clinic lists. There are approximately 400–420 KTRs registered in UHL kidney transplant outpatient clinics. Full lists of inclusion and exclusion criteria for KTRs are included in table 1. Patients will be screened by a clinician for eligibility to enter the study. Eligible patients will be approached (via telephone, post or during their routine clinical appointment) and will be provided with verbal and written study information and time to consider without further contact (at least 24 hours). Additionally, eligible patients who have given prior consent to be contacted regarding research opportunities will be contacted via post. All patients will be given the opportunity to discuss the study in more detail and to consider their participation. Consent will be performed by the chief investigator (MG-B) according to the rules of good clinical practice. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for healthy controls are included in table 1.

Table 1.

ECSERT inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

KTRs

|

|

Healthy controls

|

|

*That is, significant comorbidity including unstable hypertension, potentially lethal arrhythmia, myocardial infarction within 6 months, unstable angina, active liver disease, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (HbA1c ≥9%), advanced cerebral or peripheral vascular disease which, in the opinion of the patient’s own clinician, may either put the patient at risk because of participation in the study, or may influence the result of the study, or the patient’s ability to participate in the study.

BMI, body mass index; CMR, cardiac MRI; KTR, kidney transplant recipient.

Randomisation

Following baseline assessment, participants will be randomly allocated (1:1) to either: (1) a 12week, home-based combined resistance and aerobic exercise intervention (n=25); or (2) control (n=25; receiving usual care). Randomisation will be blocked (using computer-generated random permuted blocks with allocation concealment; https://www.sealedenvelope.com/simple-randomiser/v1/) to ensure periodic balancing. The clinical trials facilitator will perform the randomisation. Given the nature of the intervention, it is not possible for the participants to be blinded to their allocation.

Intervention and comparator arms

Intervention group: 12week, home-based combined aerobic and resistance training

The 12week, home-based, structured exercise programme includes aerobic and resistance training (four to five sessions in total per week). Participants will be advised to complete a warm-up and cool-down prior to and following each session, respectively. Participants will continue to receive usual clinical care.

Aerobic component

The aerobic component of the intervention will be walking, jogging, cycling or similar, depending on resources available and participant preference. Participants will be asked to complete two to three sessions per week using a rating of perceived exertion (RPE)57 of 13–15 (somewhat hard) for 20–30 min. RPE will be collected throughout cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPET) and participants will be educated on its use during the instructional session(s). RPE will be used rather than heart rate for two reasons: (1) Many patients are on medication which impacts heart rate (eg, beta blockers). We therefore cannot ascertain a true maximal heart rate from the exercise test in order for them to safely (and reliably) monitor intensity this way without supervision. (2) This is a pragmatic decision based on the potential for translation into low-cost future studies and clinical practice. However, should participants in the trial already own a smart watch or heart rate monitor, we would not discourage them from using it if they desire.

Resistance component

The resistance component of the exercise intervention will include a combination of six to eight exercises per session chosen by the participant from a pool of 12 exercises (to provide variety) targeting upper and lower body and core muscle groups using free weights and/or resistance bands. The chosen pool of exercises include: squat, hip abduction, lunge, calf raise, side lunge, bicep curl, bent-over row, reverse fly, lateral raise, chest press, side bends and standing trunk rotation. Each exercise has modifications for different abilities and may be pragmatically adjusted or changed throughout the study as required. These exercises were chosen based on their ability to be modified, their subjective difficulty and their safety when being performed by participants new to exercise in an unsupervised environment. Participants will aim to complete six to eight resistance exercises twice a week (but not on consecutive days to allow appropriate recovery). Initially, they will be advised to complete one to two sets of 10 repetitions (at approximately 60% of estimated 1 repetition maximum (1RM)58) gradually increasing to three to six sets of 10 repetitions over the study period with a minimum of 30 s rest between sets. The 1RM will be determined after randomisation by an exercise physiologist. These figures may be adjusted to accommodate different abilities and different rates of progression. Where equipment is limited (eg, participants reach the highest provided dumbbell weight), participants will be advised to increase the number of sets performed. The load chosen was based on previous research which suggests while heavier loads (>60% of 1RM) are favoured for increasing strength, the effect size is still large for lighter loads (<60% of 1RM) and both are effective for increasing muscle size.59 It is important not to discourage inactive or inexperienced participants with very heavy loads. Participants will be provided with an exercise diary which includes additional instructions, dumbbells and resistance bands, and access to educational and instructional videos. Instructional videos will include: the importance of an active and healthy lifestyle, the importance of warming up and cooling down and how to do it, a reminder of how to use the RPE scale, demonstrations of each resistance exercise and information about the aerobic component (videos can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLwbE3AF9Ej_Vul5uoiF-C9Cl8wrgKz5Nv). Participants will receive a telephone call from a member of the research team every 2weeks in order to discuss the progression of the exercise and address any issues that may arise. Participants will also be able to contact the research team at any time should they require and will continue to attend any scheduled clinic appointments and take prescribed medication as normal.

Control group: ‘Usual care’

Participants in the control group will be asked to maintain their current lifestyle and exercise habits throughout the study. This includes continuing to attend any scheduled clinic appointments and taking prescribed medication as normal. As part of routine care, KTRs are recommended to take regular exercise and maintain a healthy lifestyle. This advice will be reiterated to patients in the control group to ensure the intervention is being appropriately compared with best practice standard care. Participants will be asked to complete a ‘control diary’ to note any exercise, medication changes, illness and other relevant information. Once control participants complete the postintervention assessments, they will be offered the opportunity to complete the same intervention as the exercise group.

Study timeline

Baseline assessments

The ECSERT study timeline is shown in figure 1. Baseline assessments described below will be carried out on the same day where possible and in conjunction with routine clinical appointments to prevent additional travel.

Collection of routine clinical information and cost-effectiveness

Clinical information will be extracted from the medical notes including: age, gender, ethnicity, primary cause of kidney failure, transplant type, transplant vintage, dialysis duration, comorbidities, blood/urine results, current medication and smoking habits. This information will be used to primarily capture cofounding variables and during analyses of differences and similarities between groups.

A questionnaire will be administered at baseline to capture the previous 3 months of self-reported healthcare utilisation including: inpatient and outpatient appointments, emergency care, community and primary care services, support services and changes in medications. This will be compared with data gathered from healthcare records allowing validation of the questionnaire for future cost-effectiveness analyses.

Cardiac stress MRI

All participants will undergo a comprehensive adenosine stress perfusion CMR scans at baseline and on study completion. Participants will be scanned on a 3T platform (Skyra, Siemens Medical Imaging, Erlangen, Germany) with an 18-channel phased array receiver coil. New-generation gadolinium-based contrast agent with a licence for use in patients with an (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 will be given for perfusion and delayed enhancement imaging. Patients with an eGFR <40 mL/min/1.73 m2 will undergo non-contrast CMR scanning without gadolinium. Scans will quantitatively define:

Left and right ventricular structures and functions (left ventricular mass, left and right ventricular volumes and ejection fractions).60

Tissue characterisation with native and postcontrast T1 mapping and delayed gadolinium enhancement.61–63

Myocardial systolic strain and peak early-diastolic strain rate.26

Quantitative perfusion imaging (coronary blood flow to quantify coronary reserve and ischaemia).64

Aortic distensibility.24

Quadriceps MRI

At the end of the CMR scan, participants will immediately undergo an MRI scan of the quadriceps muscle in their right leg to assess muscle size (volume) as previously described.65

Cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET)

A CPET using a standardised ramp protocol will be performed on a stationary electronically braked cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur Sport, Groningen, Netherlands) with increasing workload (1 W every 4 s (10–15 W/min)) ensuring volitional exhaustion within 12–15 min.66 Participants will be encouraged to cycle at a continuous cadence (~70 rpm). The highest oxygen uptake will be measured (V̇O2 peak) using a simultaneous gas analyser (Metalyser 3B CPX System, CORTEX, Germany) as true maximal (plateau) V̇O2 (V̇O2max) is less commonly achieved in deconditioned and/or clinical patients. Test data will be considered usable if respiratory exchange ratio is ≥1.00 and RPE is ≥18. The test will be in the presence of a cardiac nurse to confirm safety to commence exercise training. Blood pressure will be assessed at baseline and every 2min throughout the test. A continuous 12-lead ECG will be monitored throughout. A non-invasive monitor (Moxy, Fortiori Design, Minnesota, USA) will be worn on the quadriceps muscle which uses near-infrared spectroscopy to measure local oxygen saturation (SmO2) and total haemoglobin of the muscle.

Lower limb strength and muscular endurance

Isometric and isokinetic muscle (knee extension) strength of the dominant leg will be assessed using a dynamometer (Biodex System 4, Biodex Medical Systems, New York, USA).67 Peak isometric strength (torque, Nm) will be assessed from three repetitions of maximum effort at 90° knee flexion for ~3–5 s with 60 s rest. Isokinetic strength will be assessed at three speeds for one set of five repetitions at each speed: 60°/s, 90°/s, 120°/s. Participants will perform a ‘sit-to-stand-60’ (STS-60) test measuring how many sit-to-stand cycles can be performed over 60 s to assess lower limb muscular endurance.68

Hand grip strength

Peak grip strength of the left and right hands will be assessed with a hand dynamometer (Jamar Plus+; Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, Illinois). Each hand will be alternatively tested for three attempts each and the highest value on each hand with be recorded.69

Gait speed

A 4 m walk test will be used to assess gait speed. Participants will be asked to walk 4 m at their ‘usual walking pace’ for one practice and two timed trials. The average score (m/s) of the timed trials will be recorded.

Functional mobility

The ‘timed-up-and-go’ (TUAG) test will be used to assess functional mobility.70 71 The participant is timed while rising from the seated position on a chair, walking 3 m, turning around and returning to a seated position.

Balance and postural stability

Postural stability and balance will be assessed using a previously reported method72 with a FysioMeter device (modified Nintendo Wii balance board (Nintendo, Kyoto, Japan)) connected via Bluetooth to software on a portable computer (FysioMeter, Brønderslev, Denmark). Total centre of pressure ellipse area (mm2) will be obtained.

Quadriceps ultrasound and myotonometry

Rectus femoris anatomical cross-sectional area will be measured from the right leg using B-mode 2D ultrasonography (Hitachi EUB-6500; probe frequency, 7.5 MHz) under resting conditions with the participant lying prone at 45° as previously described.65 Rectus femoris and vastus lateralis thickness, subcutaneous fat thickness and fibre pennation angles will be obtained. Measurements of the viscoelastic properties of the soft tissue above the midpoint of the rectus femoris muscle will be obtained using a myotonometry device (MyotonPro, Tallinn, Estonia).

Anthropometric measures

Anthropometric measures of height, body mass, and waist and hip circumference will be attained in accordance with standard protocols.73 Bioelectrical impedance analysis performed on an InBody analyser (InBody 370, Chicago, Illinois, USA) will be used to estimate body composition (eg, body fat percentage, fat-free mass).74 75

Survey pack

Participants will be provided with a survey pack containing the following questionnaires:

Integrated Palliative Outcome Scale (IPOS-Renal): a validated questionnaire measuring the presence and severity of disease-related symptoms. The IPOS-Renal was developed based on the Palliative Outcome Scale (POS) and IPOS palliative care surveys, but with the additional inclusion of symptoms common in CKD such as pruritus and restless legs.76

12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12): a validated 12-item questionnaire used to assess generic health outcomes from the patient’s perspective.77

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F): a validated 13-item multidimensional scale that assesses fatigue over the past 7 days using a 5-point Likert scale that covers physical fatigue, functional fatigue, emotional fatigue and social consequences of fatigue with excellent internal consistency and test–retest reliability.78 79

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): self-rated questionnaire which assesses sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month time interval.80

Patient Activation Measure (PAM): a validated, licensed tool measuring the spectrum of knowledge, skills and confidence in patients and capturing the extent to which they feel engaged and confident in taking care of their condition (‘activation’).81

Brief Health Literacy Screen: a three-item questionnaire to identify inadequate health literacy,82 validated against longer screening tools in populations with ESKD.83 84

The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ): developed by the WHO for physical activity surveillance in countries. It collects information on physical activity participation in three settings or domains (activity at work, travel to and from places and recreational activities) as well as sedentary behaviour, comprising 16 questions.85

Duke Activity Status Index (DASI): a 12-item questionnaire that uses self-reported physical work capacity to estimate peak metabolic equivalents and has been shown to be a valid measurement of functional capacity.86

Habitual physical activity

Objective data on habitual physical activity levels over a 7-day period (ideal minimum 6 days)87 will be gained from triaxial accelerometers (GENEActiv, ActivInsights, Cambridge, UK). Participants will receive the monitor at the baseline and follow-up assessments and will be asked to wear it from midnight that evening for 7 days.

Blood and urine sampling

Venous blood (30 mL) will be collected using venepuncture of the antecubital vein and prepared and stored appropriately for the following analysis:

Circulating markers of CVD.

Circulating markers of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress.

Blood glucose and HbA1c.

Lipids and triglycerides.

Full blood count and renal profile.

A urine sample will be requested to ascertain urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio.

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up visits are summarised in figure 1. An instructional session (or more if required) following baseline assessments will allow the intervention group to become familiar with the exercise requirements and allow the research team to ensure safety and competence before commencing the 12week, home-based training programme. This can be via video call or in person. At 6 weeks into the 12week period for the intervention group only, participants will be invited to review exercise progression (via video call or in person), particularly if participants are struggling to undertake the requisite amount of exercise, and as a refresher of the intervention. This combined with regular contact from research staff should aid participant compliance and monitoring.

Final assessments will be conducted for the exercise and control groups within 14 days of completing the 12week exercise or control period. Assessments completed will be identical to the baseline visit with the addition of a ‘patient satisfaction questionnaire’ to allow pragmatic future development of the study. This will also be offered to participants who withdraw from the trial. Three months after completing the exercise intervention, participants will be contacted for a semistructured one-to-one telephone interview. This will aim to understand the impact of the intervention, if any, on subsequent lifestyle and exercise habits.

Substudies

Additional informed consent will be sought for:

Ten ‘healthy’ control participants to undertake a CPET to assess the differences, if any, between CPET parameters in ‘healthy controls’ versus KTRs, particularly during the recovery period.

KTRs completing the exercise intervention will be invited to undertake a semistructured interview (via telephone, video call or in person) incorporating exercise self-efficacy, enjoyment, difficulties encountered, perceived advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and study design. Participants who withdraw before the end of the intervention will also be invited to attend, although in line with ethical standards, this will be optional.

Sample size

The purpose of this pilot study is to obtain appropriate data to adequately power future definitive trials88; a power calculation is neither relevant nor possible. A minimum sample size of 50 is based on accepted values to provide adequate estimates of SDs for future power calculations.89

Data collection and management

Data from all time points will be collected in case report forms (CRFs) by the trial team. All data will be entered into a secure database and will only be accessible on password-protected computers at UHL and University of Leicester by relevant members of the study team. No identifying information will be kept in electronic form. All source data and original participant identities will be kept in a locked office in the trial site file only at UHL.

Data analysis

Data will be assessed for normality using histograms, the Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots; continuous data to be expressed as mean (±SD) if normally distributed, or median (IQR) if not. To investigate the differences between interventions we will use analysis of (co-) variance. Independent samples t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests will be used assess for baseline differences between variables for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. These data will be used to inform the power calculation for future definitive trials.

Qualitative data will be transcribed verbatim and analysed according to the principles of interpretive thematic analysis to explore themes emerging from patient journeys through, and experiences of, the interventions and outcome measures.

Outcomes pertaining to the feasibility of the intervention and trial will be assessed and include:

Eligibility: the percentage of patients screened who are eligible.

Recruitment rate: the percentage of patients eligible who consent to the trial and the monthly recruitment rate.

Adherence to the exercise intervention: the number of completed sessions per week and specific intensity and durations achieved.

Acceptability of randomisation: comparison of the final group characteristics and identification of any stratification variables, if applicable.

Attrition rate: the number of participants who drop out of the study.

Outcome acceptability: the percentage of missing data for each outcome measure.

Safety: the number of self-reported injuries or AEs throughout the trial.

The a priori thresholds for specific feasibility and acceptability criteria are as follows: eligibility (≥50%), recruitment success of 20% of eligible participants (≥2 participants per month), adherence (an average of three exercise sessions per week) and attrition (≤30%).

Safety reporting

All AEs or adverse reactions (ARs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) or serious adverse reactions (SARs) will be recorded from the time a patient enters the study to the final study visit. Each AE or AR will be considered for severity, causality and expectedness and may be reclassified as an SAE or SAR if required.

An SAE is any AE that:

Is life threatening.

Requires hospitalisation or prolongation of a hospital admission.

Results in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity.

Is a congenital anomaly.

Results in death.

All AEs and ARs will be documented in participants’ CRFs, medical notes and an AE log, and will record the following information: description, date of onset and end date, severity, assessment of relatedness to study, other suspect device and action taken. Only AEs that are judged to be related to the study intervention or procedures will be reported to the sponsor.

All SAEs will be reported by the investigators to the sponsor within 24 hours of discovery or notification and the report will be signed by the chief investigator within 7 days. If the SAE is deemed related to the research procedures or intervention and is unexpected, a report will be sent to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) within 15 days.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement (PPI) group has been convened and will meet with the research team to review progress and address issues that arise throughout the duration of the study. The PPI partners will assist in the interpretation and dissemination of results. The trial was designed in consultation with PPI partners who advised on intervention content and outcome measure acceptability, paying particular attention to patient burden, ensuring outcome measures would not overburden participants. The PPI group approved the final design and duration of this intervention and advised the inclusion of an initial supervised intervention familiarisation period to build confidence in exercise capability.

Changes to the study protocol following the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has made us all review the ways we design and deliver clinical studies. While patient safety remains the absolute priority of clinical and research teams, there is a need for research to continue in a safe way that balances the benefits of continuing programmes of research against the risks from COVID-19. We have amended the study protocol in several ways to reduce any additional exposure of patients to clinical environments where COVID-19 may be present:

We have reduced the number of study visits to a minimum. The original study flow diagram is included in online supplemental file 1. All interim assessments have been removed in the modified protocol (figure 1) and the baseline and final study visits are now wrapped into part of patient clinical care. That is to say, when they attend for their baseline and follow-up study visits they will have their clinical review and clinical blood tests as they would for their normal clinical care with a transplant nephrologist (MG-B), so there is no increase in patient visits to a clinical environment over and above their normal care.

The original study design included a 2week, face-to-face training period where participants would attend the hospital to learn how to complete the exercises and the exercise programme with a member of the research team. This training period will now be done remotely via videoconferencing, with discussion and feedback over the telephone and using the instructional videos and literature that support the home-based exercise intervention.

When participants attend for their study visits, departmental procedures have been updated to now include meticulous cleaning of all equipment before and after use, one-way flows of participants to ensure participants do not mix and the use of personal protective equipment for all staff and participants.

bmjopen-2020-046945supp001.pdf (97KB, pdf)

The above changes have been agreed with the local REC and the study sponsor and have allowed recommencement of study recruitment and procedures.

Discussion

This pilot study is designed to assess the feasibility of delivering a structured, home-based exercise intervention in KTRs at increased cardiometabolic risk and evaluate the putative effects on cardiovascular structure and functional changes, cardiorespiratory fitness, quality of life, healthcare utilisation, patient activation and engagement with the prescribed exercise programme. It is the first trial to use a pragmatic home-based programme of exercise in this patient group. It is also the first to use CMR to evaluate the structural and functional changes of the heart in this at-risk population.

Qualitative data will provide valuable personal perspectives on the acceptability of this specific exercise programme. Transplant recipients experience complex medical journeys and are likely to have specific unmet needs in the area of exercise and lifestyle.90 This will be valuable information for future randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and exercise guideline development.

Home-based intervention outcomes are reliant on accurate reporting by participants with regard to frequency, intensity and duration of exercise performed. This under-reporting is often a limitation of unsupervised interventions. We will ensure participants are correctly advised on how to monitor and report their exercise completion throughout the trial and encourage this through telephone communications.

We anticipate that a positive outcome will lead to both an increased understanding of the specific exercise requirements of KTRs and the development of new programmes that promote longer term engendered lifestyle change that can be incorporated into standard practice with much lower financial implications than in-centre supervised rehabilitation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical issues

The University of Leicester is the sponsor for this study (UOL 0714). The protocol was reviewed by the East Midlands-Nottingham 2 REC and was given a favourable opinion (REC reference: 19/EM/0209) on 14 October 2019. Health Research Authority regulatory approval was given on 14 October 2019, and the study was adopted on the National Institute for Health Research portfolio on 26 September 2019. Local governance approval was granted by UHL Research & Innovation on 31 January 2020. This study was prospectively registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (11 October 2019). The first participant was recruited on 9 March 2020. The predicted study end date is 31 December 2022. This manuscript is quorate with the most recent approved protocol (version 6, 26 August 2020). Relevant parties will be informed of any substantial protocol modifications. Steps have been taken when designing this protocol to minimise the ethical implications and ensure patient welfare. The study will comply with the International Conference for Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care.

Dissemination

On completion, the results of this study will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international conferences. Contributions of all authors to manuscripts arising from this study will be made explicit in the relevance of each individual journal. Participant-level data will be available following publication of results on request to the chief investigator. Results will also be disseminated to the patient and public community via social media and newsletter articles and presentations at patient conferences and forums, led by the patient partners. It is anticipated that the results of this study will inform future design of larger RCTs in this subject area and contribute to future specific physical activity guidelines in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Twitter: @RBillany, @SAdenwalla

Contributors: REB and MG-B: study design, study set-up, completion of study visits, drafting of manuscript, revision of manuscript, finalising of manuscript. NCB, TJW, ACW, SFA, KAR, KC, EMB, NJC, JB, GPM, JOB, ACS: study design, drafting of manuscript, revision of manuscript. NV, KSP, JVW: completion of study visits, drafting of manuscript, revision of manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by a project grant from Kidney Research UK (ref: KS_RP_003_20180913).

Disclaimer: Neither the sponsor nor the funder had or will have any input into study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JLR. How great is the survival advantage of transplantation over dialysis in elderly patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:945–51. 10.1093/ndt/gfh022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steenkamp R, Rao A, Fraser S. Uk renal registry 18th annual report (December 2015) chapter 5: survival and causes of death in UK adult patients on renal replacement therapy in 2014: national and Centre-specific analyses. Nephron;2016:111–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neale J, Smith AC. Cardiovascular risk factors following renal transplant. World J Transplant 2015;5:183–95. 10.5500/wjt.v5.i4.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Renal Registry (2020) UK renal registry 22nd annual report – data to 31/12/2018, Bristol, UK. Available: renal.org/audit-research/annual-report

- 5.Kasiske BL, Guijarro C, Massy ZA, et al. Cardiovascular disease after renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996;7:158–65. 10.1681/ASN.V71158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter MA, John A, Weir MR, et al. Bp, cardiovascular disease, and death in the folic acid for vascular outcome reduction in transplantation trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:1554–62. 10.1681/ASN.2013040435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mall G, Huther W, Schneider J, et al. Diffuse intermyocardiocytic fibrosis in uraemic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1990;5:39–44. 10.1093/ndt/5.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakri RS, Afzali B, Covic A. Cardiovascular disease in renal allograft recipients is associated with elevated sialic acid or markers of inflammation. Clin Transpl 2004;18:201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liefeldt L, Budde K. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in renal transplant recipients and strategies to minimize risk. Transpl Int 2010;23:1191–204. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Laecke S, Malfait T, Schepers E, et al. Cardiovascular disease after transplantation: an emerging role of the immune system. Transpl Int 2018;31:689–99. 10.1111/tri.13160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, et al. The Framingham predictive instrument in chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:217–24. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aalten J, Peeters SA, van der Vlugt MJ, et al. Is standardized cardiac assessment of asymptomatic high-risk renal transplant candidates beneficial? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:3006–12. 10.1093/ndt/gfq822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansell H, Rosaasen N, Dean J, et al. Evidence of enhanced systemic inflammation in stable kidney transplant recipients with low Framingham risk scores. Clin Transplant 2013;27:E391–9. 10.1111/ctr.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansell H, Stewart SA, Shoker A. Validity of cardiovascular risk prediction models in kidney transplant recipients. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:750579. 10.1155/2014/750579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devine PA, Courtney AE, Maxwell AP. Cardiovascular risk in renal transplant recipients. J Nephrol 2019;32:389–99. 10.1007/s40620-018-0549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasiske BL. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease after renal transplantation. Transplantation 2001;72:S5–8. 10.1097/00007890-200109271-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Albuquerque Suassuna PG, Sanders-Pinheiro H, de Paula RB. Uremic cardiomyopathy: a new piece in the chronic kidney Disease-Mineral and bone disorder puzzle. Front Med 2018;5:206–06. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoki J, Ikari Y, Nakajima H, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of dilated cardiomyopathy in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2005;67:333–40. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mark PB, Doyle A, Blyth KG, et al. Vascular function assessed with cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts survival in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2008;10:39. 10.1186/1532-429X-10-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic disease in patients starting end-stage renal disease therapy. Kidney Int 1995;47:186–92. 10.1038/ki.1995.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular geometry in uremic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;5:2024–31. 10.1681/ASN.V5122024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali A, Macphee I, Kaski JC, et al. Cardiac and vascular changes with kidney transplantation. Indian J Nephrol 2016;26:1–9. 10.4103/0971-4065.165003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel RK, Mark PB, Johnston N, et al. Renal transplantation is not associated with regression of left ventricular hypertrophy: a magnetic resonance study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1807–11. 10.2215/CJN.01400308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham-Brown MPM, Adenwalla SF, Lai FY, et al. The reproducibility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging measures of aortic stiffness and their relationship to cardiac structure in prevalent haemodialysis patients. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:864–73. 10.1093/ckj/sfy042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham-Brown MPM, Rutherford E, Levelt E, et al. Native T1 mapping: inter-study, inter-observer and inter-center reproducibility in hemodialysis patients. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19:21. 10.1186/s12968-017-0337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham-Brown MP, Gulsin GS, Parke K, et al. A comparison of the reproducibility of two cine-derived strain software programmes in disease states. Eur J Radiol 2019;113:51–8. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriska AM, Saremi A, Hanson RL, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in a high-risk population. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:669–75. 10.1093/aje/kwg191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatakis E, Gale J, Bauman A, et al. Sitting time, physical activity, and risk of mortality in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2062–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koolhaas CM, Dhana K, Schoufour JD, et al. Impact of physical activity on the association of overweight and obesity with cardiovascular disease: the Rotterdam study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:934–41. 10.1177/2047487317693952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swift DL, Lavie CJ, Johannsen NM, et al. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and exercise training in primary and secondary coronary prevention. Circ J 2013;77:281–92. 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barengo NC, Hu G, Lakka TA, et al. Low physical activity as a predictor for total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men and women in Finland. Eur Heart J 2004;25:2204–11. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielens H, Lejeune TM, Lalaoui A, et al. Increase of physical activity level after successful renal transplantation: a 5 year follow-up study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:134–40. 10.1093/ndt/16.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dontje ML, de Greef MHG, Krijnen WP, et al. Longitudinal measurement of physical activity following kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant 2014;28:394–402. 10.1111/ctr.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masiero L, Puoti F, Bellis L, et al. Physical activity and renal function in the Italian kidney transplant population. Ren Fail 2020;42:1192–204. 10.1080/0886022X.2020.1847723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson TJ, Clarke AL, Nixon DGD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of physical activity across kidney disease stages: an observational multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2021;36:641–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfz235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol 2012;2:1143–211. 10.1002/cphy.c110025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth FW, Laye MJ, Roberts MD. Lifetime sedentary living accelerates some aspects of secondary aging. J Appl Physiol 2011;111:1497–504. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00420.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oguchi H, Tsujita M, Yazawa M, et al. The efficacy of exercise training in kidney transplant recipients: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Exp Nephrol 2019;23:275–84. 10.1007/s10157-018-1633-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathur S, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Wickerson L, et al. Meeting report: consensus recommendations for a research agenda in exercise in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014;14:2235–45. 10.1111/ajt.12874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Muras K, Nowicki M. Effects of a structured physical activity program on habitual physical activity and body composition in patients with chronic kidney disease and in kidney transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant 2019;17:155–64. 10.6002/ect.2017.0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor EM, Koufaki P, Mercer TH, et al. Long-term pulse wave velocity outcomes with aerobic and resistance training in kidney transplant recipients - A pilot randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moraes Dias CJ, Anaisse Azoubel LM, Araújo Costa H, et al. Autonomic modulation analysis in active and sedentary kidney transplanted recipients. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2015;42:1239–44. 10.1111/1440-1681.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karelis AD, Hébert M-J, Rabasa-Lhoret R, et al. Impact of resistance training on factors involved in the development of new-onset diabetes after transplantation in renal transplant recipients: an open randomized pilot study. Can J Diabetes 2016;40:382–8. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roi GS, Stefoni S, Mosconi G, et al. Physical activity in solid organ transplant recipients: organizational aspects and preliminary results of the Italian project. Transplant Proc 2014;46:2345–9. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romano G, Simonella R, Falleti E, et al. Physical training effects in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2010;24:510–4. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinnafick F-E, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Shepherd SO, et al. In it together: a qualitative evaluation of participant experiences of a 10-Week, group-based, workplace HIIT program for Insufficiently active adults. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2018;40:10–19. 10.1123/jsep.2017-0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Baar ME, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, et al. Effectiveness of exercise in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: nine months' follow up. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:1123–30. 10.1136/ard.60.12.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmons JF, Griffin C, Cogan KE, et al. Exercise maintenance in older adults 1 year after completion of a supervised training intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:163–9. 10.1111/jgs.16209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff 2013;32:207–14. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skolasky RL, Mackenzie EJ, Wegener ST, et al. Patient activation and adherence to physical therapy in persons undergoing spine surgery. Spine 2008;33:E784–91. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818027f1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baggetta R, D'Arrigo G, Torino C, et al. Effect of a home based, low intensity, physical exercise program in older adults dialysis patients: a secondary analysis of the excite trial. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:248. 10.1186/s12877-018-0938-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Imran HM, Baig M, Erqou S, et al. Home-Based cardiac rehabilitation alone and hybrid with center-based cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012779. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uchiyama K, Washida N, Morimoto K, et al. Home-Based aerobic exercise and resistance training in peritoneal dialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2019;9:2632. 10.1038/s41598-019-39074-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aoike DT, Baria F, Kamimura MA, et al. Home-based versus center-based aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary performance, physical function, quality of life and quality of sleep of overweight patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 2018;22:87–98. 10.1007/s10157-017-1429-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majchrzak KM, Pupim LB, Chen K, et al. Physical activity patterns in chronic hemodialysis patients: comparison of dialysis and nondialysis days. J Ren Nutr 2005;15:217–24. 10.1053/j.jrn.2004.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carvalho EV, Reboredo MM, Gomes EP, et al. Physical activity in daily life assessed by an accelerometer in kidney transplant recipients and hemodialysis patients. Transplant Proc 2014;46:1713–7. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borg GA. Perceived exertion: a note on "history" and methods. Med Sci Sports 1973;5:90–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brzycki M. Strength testing—predicting a one-rep max from reps-to-fatigue. J Phys Educ Recreat Dance 1993;64:88–90. 10.1080/07303084.1993.10606684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, et al. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res 2017;31:3508–23. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hunold P, Vogt FM, Heemann UW, et al. Myocardial mass and volume measurement of hypertrophic left ventricles by MRI--study in dialysis patients examined before and after dialysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2003;5:553–61. 10.1081/jcmr-120025230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Graham-Brown MPM, March DS, Churchward DR, et al. Novel cardiac nuclear magnetic resonance method for noninvasive assessment of myocardial fibrosis in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2016;90:835–44. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu H-Y, Yang Z-G, Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic value of heart failure in hemodialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease patients with myocardial fibrosis quantification by extracellular volume on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020;20:12. 10.1186/s12872-019-01313-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Graham-Brown MP, Singh AS, Gulsin GS, et al. Defining myocardial fibrosis in haemodialysis patients with non-contrast cardiac magnetic resonance. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2018;18:145. 10.1186/s12872-018-0885-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xue H, Brown LAE, Nielles-Vallespin S, et al. Automatic in-line quantitative myocardial perfusion mapping: processing algorithm and implementation. Magn Reson Med 2020;83:712–30. 10.1002/mrm.27954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gould DW, Watson EL, Wilkinson TJ, et al. Ultrasound assessment of muscle mass in response to exercise training in chronic kidney disease: a comparison with MRI. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:748–55. 10.1002/jcsm.12429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:211–77. 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feiring DC, Ellenbecker TS, Derscheid GL. Test-retest reliability of the biodex isokinetic dynamometer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1990;11:298–300. 10.2519/jospt.1990.11.7.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilkinson TJ, Xenophontos S, Gould DW, et al. Test-retest reliability, validation, and "minimal detectable change" scores for frequently reported tests of objective physical function in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Physiother Theory Pract 2019;35:565–76. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1455249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilkinson TJ, Gabrys I, Lightfoot CJ, et al. A systematic review of handgrip strength measurement in clinical and epidemiological studies of kidney disease: toward a standardized approach. J Ren Nutr 2021. 10.1053/j.jrn.2021.06.005. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Jul 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hadjiioannou I, Wong K, Lindup H, et al. Test-restest reliability for physical function measures in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 2020;46:25-34. 10.1111/jorc.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilkinson TJ, Nixon DGD, Smith AC. Postural stability during standing and its association with physical and cognitive functions in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2019;51:1407–14. 10.1007/s11255-019-02192-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eston RG, Reilly T. Kinanthropometry and exercise physiology laboratory manual: tests, procedures, and data. 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chertow GM, Lowrie EG, Wilmore DW, et al. Nutritional assessment with bioelectrical impedance analysis in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6:75–81. 10.1681/ASN.V6175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Macdonald JH, Marcora SM, Jibani M, et al. Bioelectrical impedance can be used to predict muscle mass and hence improve estimation of glomerular filtration rate in non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:3481–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfl432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raj R, Ahuja K, Frandsen M, et al. Validation of the IPOS-Renal symptom survey in advanced kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:281–7. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang S-Y, Zang X-Y, Liu J-D, et al. Psychometric properties of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) in Chinese patients receiving maintenance dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:135–43. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (fact) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13:63–74. 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004;36:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cavanaugh KL, Osborn CY, Tentori F, et al. Performance of a brief survey to assess health literacy in patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J 2015;8:462–8. 10.1093/ckj/sfv037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dageforde LA, Cavanaugh KL, Moore DE, et al. Validation of the written administration of the short literacy survey. J Health Commun 2015;20:835–42. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health 2009;6:790–804. 10.1123/jpah.6.6.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke activity status index). Am J Cardiol 1989;64:651–4. 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90496-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dillon CB, Fitzgerald AP, Kearney PM, et al. Number of days required to estimate habitual activity using Wrist-Worn GENEActiv Accelerometer: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0109913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moore CG, Carter RE, Nietert PJ, et al. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin Transl Sci 2011;4:332–7. 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00347.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:301–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gordon EJ, Prohaska T, Siminoff LA, et al. Needed: tailored exercise regimens for kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;45:769–74. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046945supp001.pdf (97KB, pdf)