Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Weight reduction is fundamental for type 2 diabetes management and remission, but uncertainty exists over which diet type is best to achieve and maintain weight loss. We evaluated dietary approaches for weight loss, and remission, in people with type 2 diabetes to inform practice and clinical guidelines.

Methods

First, we conducted a systematic review of published meta-analyses of RCTs of weight-loss diets. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, up to 7 May 2021. We synthesised weight loss findings stratified by diet types and assessed meta-analyses quality with A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2. We assessed certainty of pooled results of each meta-analysis using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) (PROSPERO CRD42020169258). Second, we conducted a systematic review of any intervention studies reporting type 2 diabetes remission with weight-loss diets, in MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, up to 10 May 2021. Findings were synthesised by diet type and study quality (Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2.0 and Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions [ROBINS-I]), with GRADE applied (PROSPERO CRD42020208878).

Results

We identified 19 meta-analyses of weight-loss diets, involving 2–23 primary trials (n = 100–1587), published 2013–2021. Twelve were ‘critically low’ or ‘low’ AMSTAR 2 quality, with seven ‘high’ quality. Greatest weight loss was reported with very low energy diets, 1.7–2.1 MJ/day (400–500 kcal) for 8–12 weeks (high-quality meta-analysis, GRADE low), achieving 6.6 kg (95% CI −9.5, −3.7) greater weight loss than low-energy diets (4.2–6.3 MJ/day [1000–1500 kcal]). Formula meal replacements (high quality, GRADE moderate) achieved 2.4 kg (95% CI −3.3, −1.4) greater weight loss over 12–52 weeks. Low-carbohydrate diets were no better for weight loss than higher-carbohydrate/low-fat diets (high quality, GRADE high). High-protein, Mediterranean, high-monounsaturated-fatty-acid, vegetarian and low-glycaemic-index diets all achieved minimal (0.3–2 kg) or no difference from control diets (low to critically low quality, GRADE very low/moderate). For type 2 diabetes remission, of 373 records, 16 met inclusion criteria. Remissions at 1 year were reported for a median 54% of participants in RCTs including initial low-energy total diet replacement (low-risk-of-bias study, GRADE high), and 11% and 15% for meal replacements and Mediterranean diets, respectively (some concerns for risk of bias in studies, GRADE moderate/low). For ketogenic/very low-carbohydrate and very low-energy food-based diets, the evidence for remission (20% and 22%, respectively) has serious and critical risk of bias, and GRADE certainty is very low.

Conclusions/interpretation

Published meta-analyses of hypocaloric diets for weight management in people with type 2 diabetes do not support any particular macronutrient profile or style over others. Very low energy diets and formula meal replacement appear the most effective approaches, generally providing less energy than self-administered food-based diets. Programmes including a hypocaloric formula ‘total diet replacement’ induction phase were most effective for type 2 diabetes remission. Most of the evidence is restricted to 1 year or less. Well-conducted research is needed to assess longer-term impacts on weight, glycaemic control, clinical outcomes and diabetes complications.

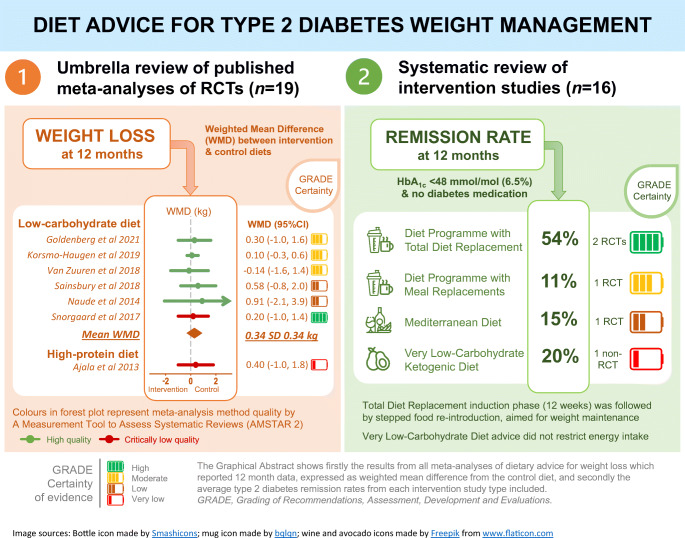

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00125-021-05577-2.

Keywords: Diet, Evidence-based guidelines, Informed clinical practice, Meta-analysis, Quality assessment, Randomised trial, Remission, Systematic review, Type 2 diabetes, Weight loss

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes has both environmental and genetic contributors, the global epidemic consistently following obesity. Its onset is primarily driven by weight gain to an excessive level for that individual, in a complex disease process involving gut hormones, low-grade inflammation and metabolites, possibly including some from the gut microbiota [1]. Ectopic fat accumulation in liver, pancreas and muscle impairs organ functions, resulting in hyperglycaemia, commonly associated with hypertension and dyslipidaemia [2, 3]. Type 2 diabetes requires lifelong management, but disabling and life-shortening complications occur despite treatment [4]. Without strategic commitment, internationally, to effective preventive actions, type 2 diabetes will affect 629 million people worldwide by 2045 [5].

Weight loss improves all weight-related risk factors and reduces medication load. During an intensive weight loss programme, or early after bariatric surgery, there are already significant improvements in hepatic and muscle insulin sensitivity, and pancreatic first-phase insulin secretion, with rapid loss of ectopic fat from skeletal muscle and liver [2, 3, 6]. A non-diabetic state can be restored for 2 years for 70–80% of people with type 2 diabetes by interventions that maintain over 10 kg weight loss (36/149, 24% of participants in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial [DiRECT]) [7], which sustains loss of ectopic fat, reversing the pathophysiology and normalising pancreas morphology [8].

Awareness of the benefits of weight loss for type 2 diabetes is high, but both patients and healthcare practitioners currently lack authoritative guidance over diets [9]. Current guidelines state that various dietary strategies may be effective, and stress personalising weight management, to take account of social situations, but do not provide guidance over diet compositions [9, 10]. Consequently, practice can be led by distorted evidence and claims.

Adhering to any energy-reduced diet will inevitably generate and sustain weight loss, whether defined by restriction of energy, of food groups or of specific nutrients, provided that there is incomplete compensation in energy intake and expenditure. In practice, adherence and weight losses vary widely within the same programme, and comparisons between diets often appear to have conflicting results [11]. Metabolic diversity in response to specific nutrient contents has been postulated, but possibly overwhelmed or confounded by mixed behavioural responses to dietary advice. Unless carefully designed, some diets may achieve negative energy imbalance but lack essential micronutrients [12, 13] or introduce adverse health effects through other pathways [14–16]. Furthermore, short-term results may not be sustained, potentially requiring additional behavioural approaches for long-term maintenance. While different strategies may work better for some individuals (or some practitioners) than others, there may be preferred diet compositions to optimise weight control [17].

Guideline development has been difficult because systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diet types, themselves open to bias, have appeared conflicting [11]. To resolve these uncertainties and to inform clinical decision making and guideline development as part of a programme of work to update the EASD dietary recommendations, we conducted an umbrella review, to collate and critically appraise all available systematic reviews with meta-analyses of dietary interventions for weight loss in people with type 2 diabetes. As remission of diabetes is now an important goal for weight management, we also conducted a new systematic review and quality appraisal of published intervention studies of non-surgical dietary approaches for type 2 diabetes remission.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This paper focuses on dietary strategies for weight loss and type 2 diabetes remission and includes two systematic reviews: (1) a systematic ‘umbrella review’ of published meta-analyses of RCTs of diets for weight loss in people with type 2 diabetes (PROSPERO CRD42020169258); (2) a systematic review of any intervention studies which report type 2 diabetes remission (PROSPERO CRD42020208878). Our paper is written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [18] and the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis in systematic reviews: reporting guideline [19].

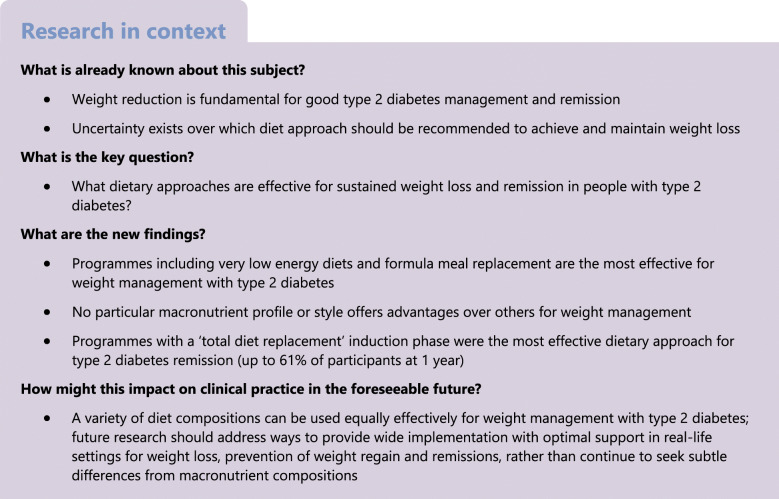

Detailed methods of both systematic reviews are presented in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) Methods and summarised in Fig. 1. The search strategy is in ESM Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the methodological processes of both systematic reviews. Detailed methods are presented in the ESM Methods. aThese types of NRSs provided intervention to participants and assessed outcomes at designated specific time points (baseline and at the end of intervention), although they could suffer from selection bias and confounding bias. bAMSTAR 2 level of quality assessment: high quality—the meta-analysis provides an accurate and comprehensive summary of the results of the available studies that addresses the question of interest; moderate—the meta-analysis has more than one weakness, but no critical flaws. It may provide an accurate summary of the results of the available studies; low—the meta-analysis has a critical flaw and may not provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies that address the question of interest; or critically low—the meta-analysis has more than one critical flaw and should not be relied on to provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies. CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; ROBINS-I, Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions; T2D, type 2 diabetes

(1) Umbrella review of published meta-analyses

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, up to 7 May 2021, for eligible meta-analyses of RCTs of dietary advice for weight loss.

Data synthesis

Synthesised findings (weight loss and HbA1c) from each meta-analysis included are grouped by diet type, ranked by overall methodological quality using A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 (ESM Tables 2, 3) and categorised into four levels: high, moderate, low and critically low. Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) evaluates the certainty of evidence of pooled results (ESM Table 4).

Planned analysis of associations between changes in energy intake and weight changes from baseline, to differentiate effects of energy restriction and dietary regimen, proved impossible from the published information.

(2) Systematic review of diets for type 2 diabetes remission

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, up to 10 May 2021, for any intervention studies reporting type 2 diabetes remission with weight loss dietary advice. We first included RCTs reporting type 2 diabetes remission as the primary outcome, the design most likely to provide trustworthy evidence. However, as few such RCTs have been conducted, we also evaluated non-randomised studies (NRSs) to capture the totality of the evidence for ‘best available advice’ to inform practice and policy [20]. Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2.0 [21] and Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [22] were used for quality assessment of RCTs and NRSs, respectively.

Data synthesis

Remission of diabetes was reported as percentage from intention to treat (ITT), including all participants. If only completers were reported, we computed an ITT figure assuming participants lost to follow-up all failed to achieve remission (as in the published RCTs). We summarised effect estimates (e.g., median and interquartile ranges), without performing meta-analysis, due to the limited number and heterogeneity of studies [23]. GRADE assesses the certainty of synthesised findings [24].

For the main synthesis, priority was set to RCTs reporting 1 year outcome and low risk of bias. If there was no RCT for a particular diet, synthesis findings were drawn from NRSs with low, followed by high, risk of bias. If both RCTs and NRSs were available for a diet, RCTs were used for synthesised findings and NRSs as supportive evidence [20]. Heterogeneity was explored according to hypothesised effect modifiers: study design, duration of type 2 diabetes and ethnicity.

Results

(1) Umbrella review of published meta-analyses of RCTs of diets for weight loss and glycaemic control

Identification of meta-analyses

We retrieved 1064 records, including all languages. After removing duplicates, we screened 690 titles and abstracts, and assessed 59 full texts for eligibility. Excluded full texts, with reasons, are shown in ESM Table 5. We included a total of 21 systematic reviews (with 19 meta-analyses) for data synthesis and quality assessment (ESM Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included meta-analyses

Of the 19 meta-analyses (Table 1, ESM Table 6), 18 reported direct comparisons of specific diets. Control diets varied, either usual/routine care or a particular dietary regimen. One meta-analysis used a network method to consider both direct and indirect comparisons between multiple diets (Mediterranean diets, low-carbohydrate diets [LCDs], low-fat diets [LFDs], high-carbohydrate diets and usual diets) [25]. Most meta-analyses were of critically low (n = 7; [25–31]) to low quality (n = 5; [32–36]). Only seven meta-analyses (LCDs, n = 5 [37–40, 41]; liquid meal replacement, n = 1 [42]; very low energy diet (VLED), n = 1 [43]) were assessed as high quality. The ESM Results and ESM Tables 7–10 present methodological quality, heterogeneity and overlaps in source trials of meta-analyses included in the umbrella review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included meta-analyses of RCTs of dietary weight management in type 2 diabetes

| Authors, yr | AMSTAR 2 quality | Protocol and no. of DBs/registries searcheda | No. of RCTs (N individuals) for weight loss outcomeb | Publication bias | INT diets (criteria) | INT: reported macronutrient intake | CON diets (criteria) | CON diet: reported macronutrient intake | Criteria for duration | Criteria for E restriction | Reported E intake in included RCTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCDs | |||||||||||

| Goldenberg et al., 2021 [41] | High |

Protocol: yes 6 DBs: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, CAB and grey literature |

18 (882) Used data from complete cases, not ITT |

Publication bias for weight loss at 6 mo | LCD (<26% E CHO) | <20 to <130 g CHO | ≥26% E CHO | NR | >12 wk | NR | NR; included RCTs with either E restriction or ad libitum E intake |

| Korsmo-Haugen et al., 2019 [37] | High |

Protocol: yes 6 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, CINAHL, Food Science Source and SweMed+ |

17 (1587) | No publication bias | LCD (<40% E CHO) |

5–40% E CHO 15–30% protein 30–50% fat |

>40% E CHO |

45–60% CHO 10–20% protein 20–36% fat |

>3 mo | NR | NR; included RCTs with either E restriction or ad libitum E intake |

| van Zuuren et al., 2018 [38] | High |

Protocol: yes 11 DBsc 5 trial registries |

16 (1000) | <10 studies included, did not conduct test for publication bias | LCD (<40% E CHO) | NR | LFD (<30% E) | NR | ≥4 wk | NR | NR; included RCTs with either E restriction or ad libitum E intake |

| Sainsbury et al., 2018 [39] | High |

Protocol: yes 5 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Global Health and CENTRAL |

7 (521)d for low- and very low-CHO diets by their definition |

Publication bias for HbA1c at 3 mo No publication bias for HbA1c at 6 or 12 mo Did not assess for weight loss |

(1) Very low CHO (<50 g CHO) (2) LCD (<130 g CHO) |

14–20% E CHO 20–120 g CHO 28–30% protein 35–58% fat |

High-CHO diet (>45% E) |

45–55% CHO 10–20% protein <30% fat |

>3 mo | NR |

INT: E intake was mostly ad libitum CON: E restriction: 6.3–7.5 MJ/d (1500–1800 kcal/d) or 2.1 MJ (500 kcal) deficit |

| Naude et al., 2014 [40] | High |

Protocol: yes 3 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL |

5 (599) | <10 studies included, did not conduct test for publication bias | LCD (<40% E CHO) |

20–40% CHO 30% protein 30–50% fat |

High-CHO diet Isoenergetic to INT 45–65% CHO 25–35% fat 10–20% protein |

55–60% CHO 30% fat 10–15% protein |

>3 mo | NR |

INT: 5.3–8.6 MJ (1260–2054 kcal) CON: 5.9–7.5 MJ (1416–1800 kcal) |

| McArdle et al., 2019 [34] | Low |

Protocol: yes 5 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and DARE |

13 (706)d for low- and very low-CHO diets by their definition |

Did not conduct |

(1) Very low CHO (<50 g CHO) (2) LCD (<130 g CHO) |

8 RCTs <50 g CHO 4 RCTs 70–130 g CHO 1 RCT unclear amount of CHO |

Low-fat, high-CHO, low-GI, high-protein, Mediterranean and ‘healthy eating’ |

CHO range: 138–232 g (50–60% E) Did not report other macronutrients |

>12 wk | NR | NR |

| Meng et al., 2017 [33] | Low |

Protocol: NR 3 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Library |

8 (590) | No publication bias for weight loss and HbA1c | LCD (<130 g or 26% E CHO) |

5–20% E CHO <20–130 g CHO |

High-CHO diet | 45–60% E CHO | NR | NR | NR |

| Snorgaard et al., 2017 [31] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 3 DBs: Embase, MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library |

10 (1376) | Did not conduct | LCD (<45% E CHO) |

14–45% CHO 15–28% protein 33–58% fat |

High-CHO (45–50% E CHO) |

41–55% CHO 15–21% protein 29–37% fat |

NR | NR | NR |

| Fan et al., 2016 [27] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 4 DBs: Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE and Cochrane Library |

9 (997) | Stated that publication bias was evaluated but did not report result | LCD (<130 g CHO) | 20-–50% CHO or 20–130 g CHO | LFD, high-CHO, ADA diete |

50–60% CHO 15–20% protein 25–30% fat |

NR | NR |

Included RCTs with either E restriction or ad libitum E intake E-restricted trials: INT: 6.3–7.5 MJ/d (1500–1800 kcal); CON: 5.9–7.5 MJ/d (1400–1800 kcal) |

| High-protein diets | |||||||||||

| Pfeiffer et al., 2020 [28] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 1 DB: PubMed |

5 (265) | Did not conduct | High-protein diet (>20% E protein), in exchange for CHO |

35–45% CHO 25–35% protein 30–35% fat |

Lower protein intake (<20% E) |

55% CHO 30% fat 15% protein |

≥8 wk | NR |

INT: 5.1–8.5 MJ/d (1219–2029 kcal) CON: 5.2–7.5 MJ/d (1235–1785 kcal) Included RCTs were of E restriction |

| Zhao et al., 2018 [30] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 2 DBs: PubMed and Embase |

16 (1059) | No publication bias for weight loss, did not assess for HbA1c | High-protein diet |

30–51% CHO 25–32% protein 18–59% fat |

Not specified |

40–60% CHO 10–20% protein 10–42% fat |

>4 wk | NR | NR |

| Low-GI diets | |||||||||||

| Zafar et al., 2019 [36] | Critically low |

Protocol: yes 3 DBs: PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase 3 trial registries |

24 (1488) | No publication bias | Low-GI diet | NR | High-GI, LFD, LCD, low-E weight-loss diets | NR | ≥1 wk | NR | NR |

| Mediterranean diets | |||||||||||

| Huo et al., 2015 [32] | Low |

Protocol: NR 3 DBs: PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase |

6 (835) | Publication bias for HbA1c | Mediterranean-style diets: high vegetable, nuts, legume, fish and fruit intakes, and low red meat intake | NR | Usual diet, usual care, ADA diete, LFD, LCD | NR | >4 wk | NR | NR |

| Liquid meal replacement | |||||||||||

| Noronha et al., 2019 [42] | High |

Protocol: yes 3 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL |

9 (931) | <10 studies included, did not conduct test for publication bias | Liquid meal replacement that replaced 1/3 of main meals |

Liquid meal represented 20% of total daily E intake (range: 13–47%) 46–52% CHO 20–35% protein 18–33% fat |

Low-E weight-loss diets Total E is isoenergetic to INT diet |

Total daily E intake 6.3 MJ (1500 kcal) 45–60% CHO 8–31% protein 15–37% fat |

>2 wk | NR | Mean 6.3 MJ (1500 kcal) (5.0–6.9 MJ [1195–1659 kcal]) in both arms |

| VLEDs | |||||||||||

| Rehackova et al., 2016 [43] | Low |

Protocol: yes 11 DBsf |

2 (100) | Did not conduct | VLED (<3.3 MJ/d [800 kcal]) | NR | Low-E diet (4.2–6.3 MJ/d [1000–1500 kcal]) | NR | NR |

VLEDs (<3.3 MJ/d [800 kcal]) |

INT: 1.7–2.1 MJ/d (400–500 kcal) CON: 4.2–6.3 MJ/d (1000–1500 kcal) |

| High-monounsaturated-fat diets | |||||||||||

| Qian et al., 2016 [29] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 3 DBs: PubMed, MEDLINE and CENTRAL |

16 (1081) | No publication bias |

High-MUFA diet No specified criteria |

39% (range: 9.5–45%) CHO 17% (range: 10–41%) protein 43% (range: 30–70%) fat 25% (range: 10–49%) MUFA |

High-CHO diet No specified criteria |

54% (range: 41–70%) CHO 17% (range: 10–23%) protein 28% (range: 10–39%) fat 11% (range: 1–20%) MUFA |

>2 wk | NR | NR |

| Vegetarian/vegan diets | |||||||||||

| Viguiliouk et al., 2019 [35] | Critically low |

Protocol: yes 3 DBs: MEDLINE, Embase and CNETRAL |

6 (532) | <10 studies included, did not conduct test for publication bias | Vegetarian diet pattern, including vegan to lacto-ovo-vegetarian |

60% (range: 49–78%) CHO 15% (range: 12–17%) protein 25% (range: 10–34%) fat 5% (range: 2–9%) SFA 28 g/d (range: 13–39 g/d) fibre |

LFD, usual diet |

50% (range: 41–65%) CHO 19% (range: 16–22%) protein 30% (range: 19–37%) fat 9% (range: 4–12%) SFA 20 g/d (range: 8–39 g/d) fibre |

≥3 wk | NR |

NR 8 RCTs E restricted 1 RCT E balanced |

| Meta-analyses with multiple diets | |||||||||||

| Ajala et al., 2013 [26] | Critically low |

Protocol: NR 3 DBs: PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar |

20 (3073) | Did not conduct | LCD | NR | LFD, low-GI, Mediterranean, high-CHO | NR | ≥6 mo | NR | NR |

| Low-GI | High-fibre, high-GI, ADA dietse | ||||||||||

| Mediterranean | Usual care, ADA dietse | ||||||||||

| High-protein diet | Low-protein, high-CHO diets | ||||||||||

| Pan et al., 2019 [25]g | Critically low |

Protocol: yes 3 DBs: PubMed, Embase and CENTRAL |

10 (921) | Did not conduct | Mediterranean | NR | High-CHO diet (>55% CHO) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mediterranean | LCD | ||||||||||

| Mediterranean | LFD (<30% E) | ||||||||||

| LCD (<26% E /<130 g) | High-CHO diet | ||||||||||

| LFD (<30% E) | LCD (<26% E or <130 g) | ||||||||||

| LFD (<30% E) | High-CHO diet | ||||||||||

aSee ESM Table 5 for detailed data sources and search used in meta-analyses in the umbrella review

bThese numbers of RCTs are not all the same as are reported in the original meta-analyses

cEleven databases: MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CENTRAL, Emcare, Academic Search Premier, ScienceDirect, Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, and Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de Salud

dThis meta-analysis also included ‘moderate’-carbohydrate RCTs (26–45% E) and these RCTs were also featured in other meta-analyses as an LCD

eDiet according to the recommendation of the ADA [66]

fEleven databases: all EBM Reviews (1991), CAB Abstracts (1973), CINAHL (1994), Embase (1980), HMIC (1979), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946), and PsychINFO (1806). We hand-searched PubMed (1984), Web of Knowledge (1983), The Cochrane library and The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)

gNetwork meta-analysis

CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; CHO, carbohydrate; CON, control; d, day; DB, database; E, energy; GI, glycaemic index; INT, intervention; mo, month; NR, not reported; SFA, saturated fatty acids; wk, week; yr, year

Dietary advice for weight loss

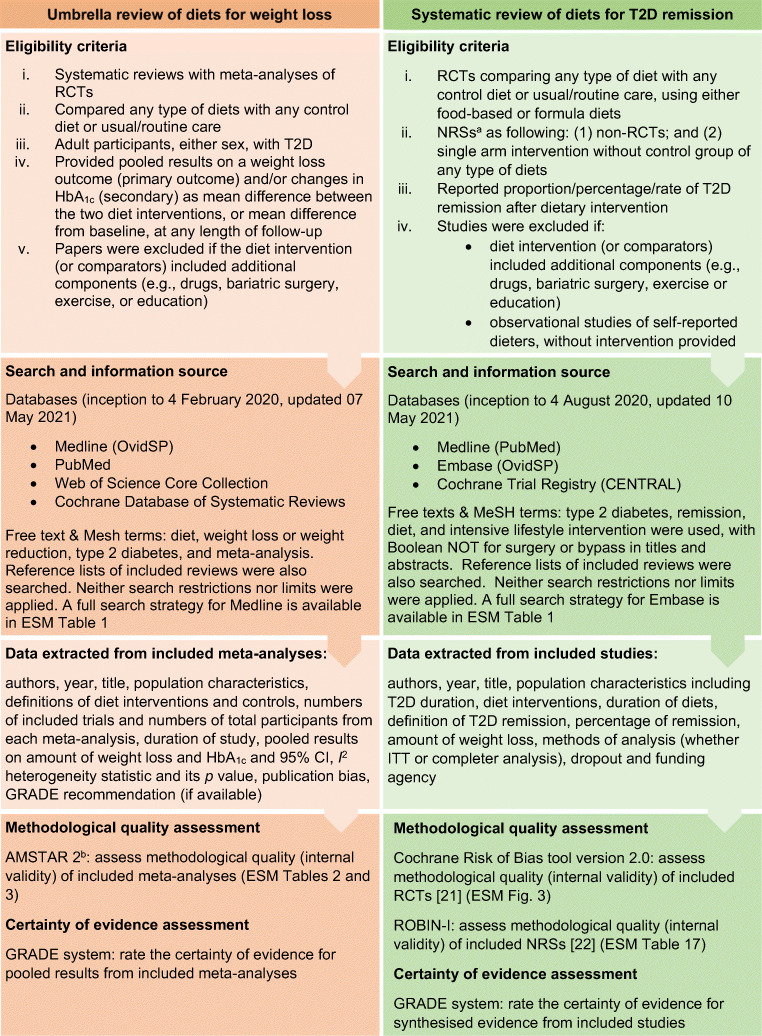

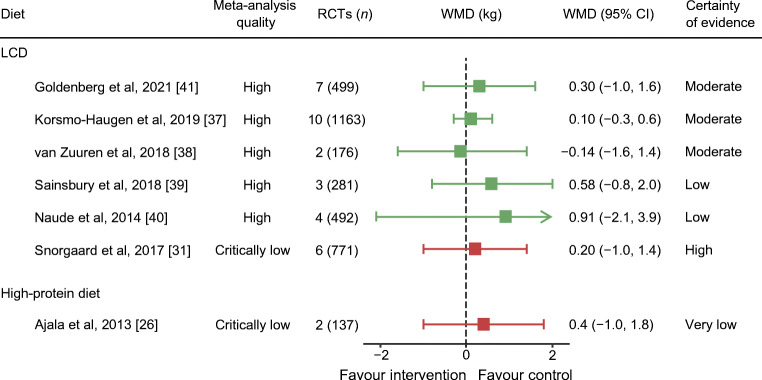

Weight loss outcomes from published meta-analyses are presented in Figs. 2, 3 and ESM Table 11.

Fig. 2.

All published meta-analyses of intervention diets vs control diets on weight loss (kg) stratified by overall quality in each diet type using AMSTAR 2 quality (green, high quality; orange, low quality; red, critically low quality). WMDs are presented alongside 95% CIs (error bars). Pooled results of McArdle et al., 2019 [34], Fan et al., 2016 [27], Zafar et al., 2019 [36] and Zhao et al., 2018 [30] are standardised mean differences. aComplete case data. GRADE level for certainty of evidence is rated as follows: ‘high’ indicates that we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; ‘moderate’ indicates that we are moderately confident in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different); ‘low’ indicates that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited (the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect); and ‘very low’ indicates that we have very little confidence in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect)

Fig. 3.

Meta-analyses with source RCTs of 12 months or longer on weight loss (kg) outcome. WMDs are presented alongside 95% CIs (error bars). Different colours indicate meta-analysis quality: green, high quality; red, critically low quality. GRADE level for certainty of evidence: ‘high’ indicates that we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; ‘moderate’ indicates that we are moderately confident in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different); ‘low’ indicates that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited (the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect); and ‘very low’ indicates that we have very little confidence in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect)

LCDs

Ten meta-analyses reported on LCDs compared with higher-carbohydrate diets. Not all reported whether source RCTs were ad libitum or hypocaloric prescriptions, with results often pooled from both trial types. Definitions of LCDs varied, including <130 g/day, and <26% or <45% of energy intake from carbohydrate. Duration of interventions ranged from 8 weeks to 4 years.

Four high-quality meta-analyses [37–40] reported that LCDs and higher-carbohydrate diets were equally effective for weight loss, with mean difference ranging between <1 and <2.5 kg, at all durations. GRADE assessment ranged from low to high certainty of evidence. Just one meta-analysis reported greater weight loss with LCD, by 3.5 kg, using complete case data for pooled results [41]. The remaining critically low- to low-quality meta-analyses showed differences of <1 kg between the two diets [26, 27, 31, 33, 34].

Very low-carbohydrate diets (21–70 g of carbohydrate daily) showed no greater weight loss than higher-carbohydrate diets over durations of 3–36 months (weight mean difference [WMD] −0.7 kg; 95% CI −2.0, 0.7; I2 = 46%, p = 0.10) in a subgroup analysis [37]. A subgroup analysis of RCTs with low risk of bias reported no difference (WMD 0.9 kg; 95% CI -1.9, 3.6), while RCTs with high risk of bias showed greater weight loss for LCDs than higher-carbohydrate diets (WMD −1.8 kg; 95% CI −2.8, −0.7) [37].

High-protein diets

All meta-analyses (n = 3) of high-protein diets were of critically low quality [26, 28, 30]. Critical domains unmet were presence of a review protocol and assessing risk of bias in synthesised findings (ESM Table 3). Only one provided a definition of ‘high protein’ (>20% of energy intake), reporting significantly greater weight loss (−1.2 kg; 95% CI −2.17, −0.24; I2 = 5%, p = 0.38) than with lower-protein diets (<20% of energy from protein) [28].

Mediterranean diets

Two meta-analyses, of low and critically low quality, considered weight loss from Mediterranean diets [26, 32]. The control interventions combined no diet (usual care) and specified diets, including LFD and LCD. Pooled results indicated significantly greater weight loss with Mediterranean diets than in control groups, by 0.3 kg (low quality; [32]) to 1.8 kg (critically low quality; [26]), over durations of 4–24 weeks. A network meta-analysis also reported that Mediterranean diets were marginally more effective than LFDs for weight loss (−1.2 kg; 95% CI −1.99, −0.37; four RCTs, low quality; p-heterogeneity = 0.08; ESM Table 12) [25].

Formula meal replacement

One high-quality meta-analysis [42] of nine RCTs including 931 participants reported that replacing one to three main meals daily (replacing 13–47% of total energy) produced significantly greater weight loss than low-energy diets over 12–52 weeks (−2.4 kg; 95% CI −3.3, −1.4; I2 = 84%, p < 0.001; GRADE moderate certainty of evidence).

VLEDs

One high-quality meta-analysis [43] of two RCTs reported that VLEDs (1.7–2.1 MJ/day for 8–12 weeks) achieved greater weight loss at 3 months (−6.6 kg; 95% CI −9.5, −3.7; I2 = 58%, p = 0.12) and at 6 months (−5.7 kg; 95% CI −11.1, −0.4; I2 = 58%, p = 0.12), compared with an energy-restricted diet (4.2–6.3 MJ/day). These data were from participants who completed the trials.

High-monounsaturated-fatty-acid, vegetarian and low-glycaemic-index diets

High-monounsaturated-fatty-acid (MUFA) [29] and vegetarian diets [35] showed greater weight losses, by −1.6 to −2 kg, than the control diets. Low-glycaemic-index diets [26, 36] were not associated with greater weight loss than control diets. Published meta-analyses of these diets were of low to critically low quality.

Intermittent fasting

We did a post hoc analysis to evaluate all systematic reviews without meta-analyses (no pooled weight loss; n = 10) that were excluded from our main analysis (as intended protocol). Eight were systematic reviews whose source RCTs were already pooled in meta-analyses identified in this umbrella review. The remaining two systematic reviews compared altered eating patterns with conventional energy-restricted diets (ESM Table 13) [44, 45]. From these two reviews, three RCTs were identified: two for 5:2 diets reported no difference in weight loss (high-risk-of-bias RCTs) [46, 47], and one for time-restricted dieting reported 1.4 kg greater weight loss than conventional energy restriction (high-risk-of-bias RCT) [48].

Adherence

Some meta-analyses offered assessed dietary adherence separately from weight change. Adherence assessed up to 1 year was poorer with very low-carbohydrate diets (<50 g of carbohydrate) than with LCDs (<130 g of carbohydrate) [34, 37, 40], possibly because most of the trials allowed increased carbohydrate intake for later weight loss maintenance. High adherence to VLEDs (up to 6 months), judged from rapid early weight loss and dietary assessment, led to better long-term results [43].

Effects of weight-loss diet intervention on HbA1c

Among published meta-analyses, HbA1c reduction broadly followed weight loss, and differences between diet types assessed over 3–12 months were small. The published data do not permit an individual-level regression analysis to quantify weight loss-independent effects on HbA1c (ESM Results, ESM Table 14).

(2) Systematic review of intervention studies (either RCTs or NRSs) of diets for remission of type 2 diabetes

Identification of studies

From 373 records identified, we included 16 papers for data synthesis and quality assessment (ESM Fig. 2; excluded studies with reasons in ESM Table 5). These reported on 14 studies (six RCTs, eight NRSs), of seven diet types: total diet replacement (n = 4), formula meal replacement (n = 2), VLED (n = 2), very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (n = 1), Mediterranean diet (n = 2), LFD (n = 4) and the ADA diet (n = 1). Five studies compared diet interventions with usual care according to clinical guidelines, without providing foods or dietary products for participants [49–53]. Among these, three provided diabetes education or advice (Table 2) [49, 50, 52]. Included studies were conducted in Barbados, India, Italy, Qatar, South Africa, Spain, Thailand, the UK and the USA. Detailed characteristics and methodological quality are in the ESM Results, ESM Tables 15–17 and ESM Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Type 2 diabetes remission (%) and mean weight loss (kg) from baseline according to different dietary regimens/patterns

| Authors, yr (study) | Design | Diet INT | CON arm | Analysis and dropout during INT | T2D remission | Weight change (kg or %) | Risk of biasa | Funding | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | CON | INT | CON | |||||||

| TDR | ||||||||||

| Taheri et al. 2020 (DIADEM-I) [53] | RCT |

TDR 3.3–3.4 MJ/d (800–820 kcal) for 12 wk, then food re-introduction over 12 wk (n = 70) |

Usual care: no diet (n = 77) |

ITT Dropout: INT = 15/70 (21%); CON = 10/77 (13%) |

1 yr: 61% (43/70) | 1 yr: 12% (9/77) | 1 yr: −12.0 | 1 yr: −4.0 | Low | Qatar National Research Fund |

| Lean et al. 2018 and 2019 (DiRECT) [51, 89] | RCT |

TDR 3.5–3.6 MJ/d (825–853 kcal) for 12 wk, then food re-introduction over 2–8 wk. (n = 149) |

Usual care: no diet (n = 149) |

ITT Dropout 1 yr: INT = 32/149 (21%); CON = 0/149 Dropout 1–2 yr: INT = 16; CON = 0 |

1 yr: 46% (68/149) 2 yr: 36% (53/149) |

1 yr: 4% (6/149) 2 yr: 3% (5/149) |

1 yr: −10.0 2 yr: −7.6 |

1 yr: −1.0 2 yr: −2.3 |

Low | Diabetes UK |

| Bynoe et al. 2020 [102] | Single arm |

TDR 3.2 MJ/d (760 kcal) for 8 wk, then food re-introduction over 4 wk (n = 25) |

N/A |

ITT Dropout:1/25 at 8 mo |

8 wk: 60% (15/25) 8 mo: 36%b (9/25) |

N/A |

8 wk: −10.1 8 mo: −8.2 |

N/A | Critical | A grant from Virgin Unite |

| Steven et al. 2016 [103] | Single arm |

TDR 2.6–2.9 MJ/d (624–700 kcal) for 8 wk, then food re-introduction over 2 wk. (n = 30) |

N/A |

ITT Dropout: 1 at 1 wk due to not meeting weight loss target |

8–10 wk: 40% (12/30) 8 mo: 43% (13/30) |

N/A |

8–10 wk: −14.2 6 mo: −13.3 |

N/A | Critical | NIHR Newcastle |

| Formula meal replacement | ||||||||||

| Gregg et al. 2012 (Look AHEAD) [49] | RCT |

Liquid meal replacement to achieve goal of 5.0–7.5 MJ/d (1200–1800 kcal) with two meal replacements during 0–20 wk and then one meal replacement thereafter (n = 2262) |

Usual care: diabetes support and education; no diet (n = 2241) |

ITT: ancillary analysis Dropout 1 yr: INT = 74/2570 (3%); CON = 112/2575 (4%) |

1 yr: 11.5% (247/2157) 2 yr: 10.4% (218/2090) 3 yr: 8.7% (181/2083) 4 yr: 7.3% (150/2056) |

1 yr: 2.0% (43/2170) 2 yr: 2.3% (48/2101) 3 yr: 2.2% (46/2085) 4 yr: 2.0% (41/2042) |

1 yr: −8.6% | 1 yr: −0.7% | Some concerns | US Department of Health and Human Services and NIH |

| Mottalib et al. 2015 (Why WAIT) [57] | Single arm |

Liquid meal replacement for breakfast and lunch to achieve goal of 5.0–7.5 MJ/d (1200–1800 kcal), 40% CHO, 30% fat, 30% protein (n = 126) |

N/A |

ITT: ancillary analysis Dropout: 38/126 (30%) at 1 yr |

1 yr: 3.2%c (4/126) | N/A | 1 yr: −7.2 in those achieving remission | N/A | Critical | See footnoted |

| Mediterranean diets and LFDs | ||||||||||

| Gutierrez-Mariscal et al. 2021 [54] | RCT |

Mediterranean diet No E restriction (n = 80) |

LFD No E restriction (n = 103) |

Complete case analysis in subset of people with CHD with T2D in original trial. Ancillary analysis | 5 yr: 41.3% (33/80) | 5 yr: 38.8% (40/103) | 5 yr: −1.16 | 5 yr: −1.4 | Some concerns | See footnotee |

| Esposito et al. 2014 [59] | RCT |

Mediterranean diet E restriction Women: 6.3 MJ/d (1500 kcal) Men: 7.5 MJ/d (1800 kcal) (n = 108) |

LFD E restriction Women: 6.3 MJ/d (1500 kcal) Men: 7.5 MJ/d (1800 kcal) (n = 107) |

ITT: ancillary analysis Dropout 1 yr: INT = 10/108 (9%); CON = 10/107 (9%) |

1 yr: 14.7% (15/102) 2 yr: 10.6% (9/85) 3 yr: 9.7% (7/72) 4 yr: 7.7% (4/52) 5 yr: 5.9% (2/34) 6 yr: 5.0% (1/20) |

1 yr: 4.1% (4/97) 2 yr: 4.7% (3/64) 3 yr: 4.0% (2/50) 4 yr: 2.9% (1/35) 5 yr: 0 6 yr: 0 |

1 yr: −6.2 | 1 yr: −4.2 | Some concerns | Second University of Naples |

| Mollentze et al. 2019 [52] | Pilot RCT |

LFDf E restriction, mainly vegetables and soups (n = 9) |

Usual care: diet advice (n = 9) |

ITT No dropout |

3 mo: NR 6 mo: 22.2% (2/9) |

3 mo: NR 6 mo: 0% |

3 mo: −9.0% 6 mo: −9.6% |

3 mo: −1.9% 6 mo: −1.5% |

High | Mr Christo Strydom, South Africa |

| Sarathi et al. 2017 [104] | Single arm |

LFD 6.3 MJ/d (1500 kcal) (n = 32) |

N/A |

ITT No dropout |

1 yr: 75.0% (24/32) 2 yr: 68.8% (22/32) |

N/A | NR | N/A | Critical | No funding |

| Dave et al. 2019 [105] | Single arm |

LFD (ADA dietg) (n = 45) |

N/A |

ITT Dropout: 4 at 5y |

1 yr: 71.1% (32/45) 5 yr: 42.2%h (19/45) |

N/A |

1 yr: −7.6 5 yr: −6.4 |

N/A | Critical | No funding |

| Ketogenic diet | ||||||||||

| Hallberg et al. 2018 and Athinarayanan et al. 2019 (VIRTA) [50, 55] | Non-RCT |

VLCKD CHO <30 g/d to achieve ketosis, 1.5 g/kg protein per d, 3–5 servings of non-starchy vegetables, multivitamin, vitamin D3 and n-3 fatty acids supplements No E restriction advised (n = 262) |

Usual care: local medical provider and education (n = 87) |

ITT: ancillary analysis Dropout 1 yr: INT = 44/262 (17%); CON = 9/87 (10%) Dropout 1–2 yr: INT = 24; CON = 10 |

1 yr: 19.8%i (52/262) 2 yr: 17.6% (46/262) |

1 yr: NR 2 yr: 2.3% (2/87) |

1 yr: −13.8 2 yr: −11.9 |

1 yr: +0.6 2 yr: +1.3 |

Serious | Virta Health |

| VLED | ||||||||||

| Umphonsathien et al. 2019 [56] | Single arm |

VLED 8 wk 2.5 MJ/d (600 kcal) food-based diet, then food re-introduction over 4 wk (n = 20) |

N/A |

ITT Dropout: 1 during run-in |

8 wk: 75% (15/20) 12 wk: 75% (15/20) |

N/A |

8 wk: NR 12 wk: −9.5 |

N/A | Critical | Prasert Prasarttong-Osoth Research Fund |

| Thomas and Shamanna, 2018 [60] | Single arm |

VLED 1 wk 2.9 MJ/d (700 kcal) food-based on diet, then advice diet for ideal body weight (n = 9) |

N/A |

ITT Dropout: 1 after completing E restriction phase |

1 yr: 22.2%j (2/9) | N/A | 1 yr: −4.2 | N/A | Critical | NR |

Remissions in Gregg et al. 2012 [49 and Esposito et al. 2014 [59] are prevalence estimates with raw cases/denominators.

aCochrane Risk of Bias tool version 2 for RCT, and Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions for non-RCT and single-arm intervention

bITT analysis was calculated from nine participants, who had fasting plasma glucose <7 mmol/l and no medication, in a total of 25 participants. For completer analysis, remission rate was 37.5% calculated from nine out of 24 completers at 8 months

cITT analysis calculated from four out of 126 participants who had HbA1c< 48 mmol/mol (<6.5%) and no medication at 1 year. For completer analysis, remission rate was 4.6% calculated from 52 out of 88 completers

dWhy WAIT programme received contributions from Novartis Medical Nutrition (currently Nestlé HealthCare Nutrition) and LifeScan.

eMinisterio de Economia y Competitividad & the Instituto de Salud Carlos III of Spain, the Directorate General for Assessment and Promotion of Research and the European Union's (EU's) European Regional Development Fund

fSee ESM Table 15 for details

gDiet according to the recommendation of the ADA [66]

hITT analysis was calculated from 19 participants who achieved remission in a total of 45 participants. For completer analysis, remission rate was 46.3% calculated from available data at 12 months (19 out of 41 completers)

iITT analysis calculated from 52 out of 262 participants in the intervention group who had HbA1c< 48 mmol/mol (<6.5%) and no medication at 1 year. For completer analysis, remission rate was 26% calculated from available data at 12 months (52 out of 204 completers)

jITT analysis calculated from two participants who had HbA1c< 48 mmol/mol (<6.5%) and no medication at 1 year, in a total of nine participants. For completer analysis, remission rate was 25% calculated from available data at 12 months (two out of eight completers)

CON, control; d, day; DIADEM-I, Diabetes Intervention Accentuating Diet and Enhancing Metabolism-I; E, energy; INT, intervention; Look AHEAD, Action for Health in Diabetes; mo, month; N/A, not applicable; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; NR, not reported; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TDR, total diet replacement; VIRTA, Virta Health Corp; VLCKD, very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet; Why WAIT, Weight Achievement and Intensive Treatment; wk, week; yr, year

Definition of type 2 diabetes remission

All included studies defined remission as a diagnostic test result, without glucose-lowering medication, below the WHO threshold for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol [6.5%], or fasting plasma glucose <7 mmol/l), but they differed in the duration prior to assessment of remission (ESM Tables 15–16). Some studies [54–57] subdivided results as previously proposed by Buse et al. [58]. Glucose-lowering medications were not routinely withdrawn at the beginning of diets in some of the studies, so only minimum remissions can be reported.

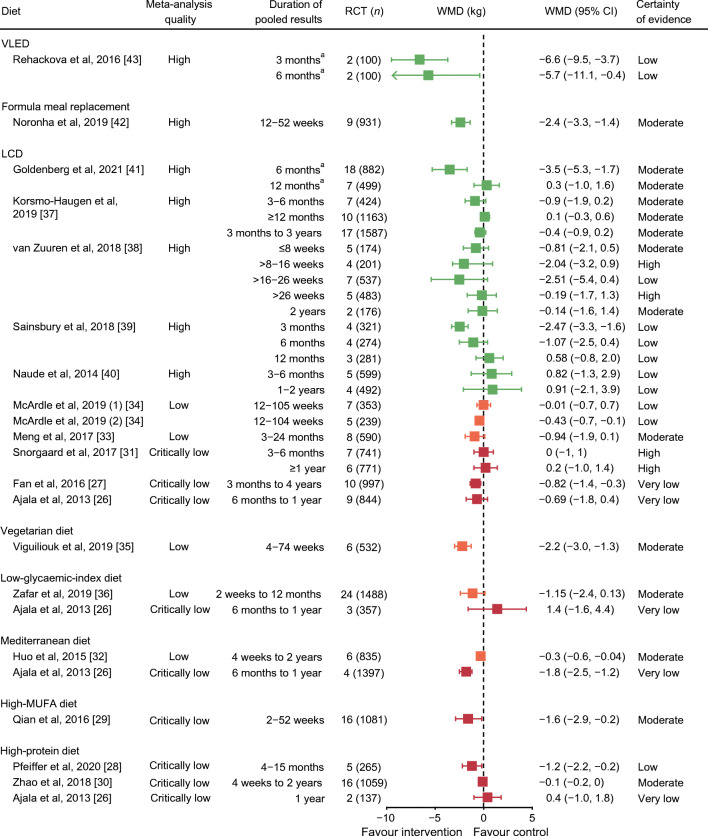

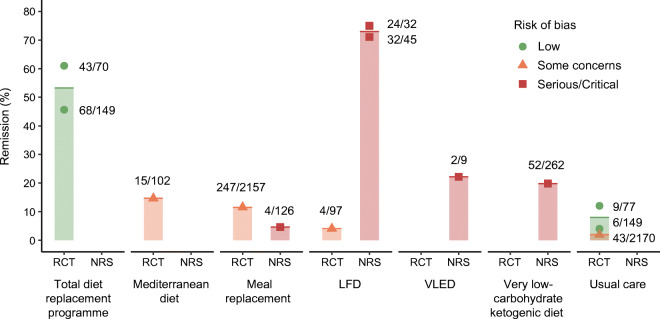

Effects of diets on type 2 diabetes remission and weight at 1 year

Remission rates and weight changes at 1 year are summarised in Fig. 4 and Table 2, with GRADE certainty of evidence in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of remissions of type 2 diabetes at 12 months after intervention with different diet types, stratified by study design and risk of bias. Each dot, with varying shapes to reflect risk of bias, indicates the data point for each of the studies mentioned in the main text which provided data in this form at 12 months. The column represents the mean for the diet type. Remission was defined as either HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (<6.5%) or fasting plasma glucose <7 mmol/l, with no glucose-lowering medication. Total diet replacement programmes included an initial low-energy formula diet, prescribed for an 8–12 week induction phase, followed by stepped food re-introduction aimed to achieve energy balance for weight loss maintenance. VLED advised a 2.9 MJ (700 kcal) food-based diet for 1 week, then dietary advice for energy intake that matched for ideal body weight. Very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet was ad libitum intake, carbohydrate <30 g/day to achieve ketosis and 3–5 servings of non-starchy vegetables. Usual diet or standard diet interventions included diabetes education support, but no new diet intervention

Table 3.

Summary of findings of type 2 diabetes remission at 1 year after diet intervention compared with baseline with GRADE certainty of a body of evidence

| Diet | Conclusion statement | No. of participants (no. of studies) | Certainty in the evidencea | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDR | TDR leads to a large increase in T2D remission by a median of 54% from baseline (range 46–61%), when compared with standard care (4–12%). | 445 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

Low-risk-of-bias RCTs, pre-specified outcomes with power calculation |

| Meal replacement | Meal replacement likely leads to T2D remission by 11% from baseline, when compared with standard care plus diabetes education (2%). | 4503 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕◯ MODERATE Due to possible publication bias |

Ancillary observational analysis of RCT |

| Mediterranean diet | Mediterranean diet may lead to T2D remission by 15% from baseline, when compared with LFD (4%). | 215 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕◯◯ LOW Due to imprecisionb and possible publication bias |

Small sample size, and ancillary observational analysis of RCT |

| Very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketogenic diet on T2D remission due to serious risk of bias of the study methods and imprecision, although one non-RCT reported a remission rate of 20%, compared with no remission in usual care with diabetes education. | 349 (1 non-RCT) |

⊕◯◯◯ VERY LOW Due to serious risk of bias (rated down 2 levels) and imprecisionb |

Lack of randomisation, uncontrolled confounding, selection bias, incomplete outcome data, possible selective reporting, imprecision and imbalance between groups |

| VLED (food based) | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of food-based VLED on T2D remission, although one small uncontrolled intervention study reported a remission rate of 22%. | 9 (1 single group uncontrolled intervention) |

⊕◯◯◯ VERY LOW Due to critical risk of bias (rated down 3 levels), imprecision and potential publication bias |

Lack of randomisation, uncontrolled confounding, selection bias and selective reporting of result. Only one positive, small study |

Remission is defined as either HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (<6.5%) or fasting plasma glucose <7 mmol/l and no glucose-lowering medication

aGRADE level for certainty of evidence: ‘high’ indicates that we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; ‘moderate’ indicates that we are moderately confident in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different); ‘low’ indicates that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited (the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect); and ‘very low’ indicates that we have very little confidence in the effect estimate (the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect)

bRated down one level due to imprecision, as the sample size is less than an optimal information size of 400

T2D, type 2 diabetes; TDR, total diet replacement

Programmes that included an induction phase of formula ‘total diet replacement’ were studied in two RCTs with low risks of bias. Compared with remissions of 4–12% in well-matched usual care control arms, the interventions generated median 54% remission at 12 months from baseline (N = 445, two RCTs; GRADE high certainty of evidence), with diabetes durations <6 or <2 years, and mean weight loss of 10 and 12 kg. These two RCTs were designed with remission as the primary outcome [51, 53].

Among trials reporting post hoc analyses for remission, one using two meal replacements/day during 0–20 weeks and one per day thereafter reported 11% (247/2157) remission at 1 year (prevalence estimates), with mean weight loss 8.6 kg, compared with 2% (43/2170) in standard care (N = 4503; GRADE low certainty of evidence), with some concern over risk of bias [49].

A single RCT of Mediterranean diet over 12 months reported a remission prevalence of 15% (15/102), with mean weight loss 6.2 kg, compared with 4% (4/97) with weight loss 4.2 kg in the control LFD arm (N = 215; GRADE low certainty of evidence; some concern over risk of bias) [59].

No RCT has evaluated LCDs/ketogenic diets for type 2 diabetes remission. A non-randomised, controlled study of a very low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diet reported 20% remission (52 out of 262 who started treatment [ITT] who had HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol [6.5%] without diabetes medication), with mean weight loss 13.8 kg, at 1 year, compared with no remission in a control arm (N = 349; GRADE very low certainty of evidence; serious risk of bias) [50]. The dropout rate was 17% (44/262) and 22% had incomplete outcome data. This study primarily focused on HbA1c lowering, not remission, so glucose-lowering medications were not routinely withdrawn.

Another very small uncontrolled study evaluated a 1 week 2.9 MJ/day (700 kcal) food-based diet, finding 22% (2/9) remission at 1 year, with mean weight loss 4.2 kg (N = 9, one single-arm intervention; GRADE very low certainty of evidence; critical risk of bias) [60].

Sources of heterogeneity

Single-arm intervention studies reported higher remission than RCTs. Participants with shorter type 2 diabetes duration, and Asian ethnicity, were more likely to achieve remission than those with longer type 2 diabetes duration or another ethnicity (Table 2, ESM Tables 15,16).

Discussion

Dietary weight reduction for people with type 2 diabetes

This study was conducted to inform practice and policy over dietary advice for weight management of people with type 2 diabetes. It has therefore focused on interventions in free-living individuals, with a view to long-term management. Based on methodological quality and certainty of the evidence, our umbrella review of meta-analyses found that VLEDs and formula meal replacements produce greater weight losses than conventional low-energy diets. The evidence does not favour LCDs above higher-carbohydrate diets, nor other dietary approaches, i.e., high-protein, Mediterranean, high-MUFA, vegetarian and low-glycaemic-index diets, above control diets. Currently popular intermittent fasting was only captured in systematic reviews without meta-analysis (high-risk-of-bias RCTs) [44, 45]. The evidence, albeit of variable ‘quality’, is rather consistent such that no one diet type is superior over others for weight management in type 2 diabetes.

While the evidence does not suggest important differences between macronutrient compositions in effectiveness, there may be differences in cost-effectiveness. The evidence on relative cost-effectiveness of weight-loss diet programmes is limited from head-to-head diet comparison trials, but one RCT showed that LCD was not more cost-effective than the standard weight-loss diet [61]. In the Doctor Referral of Overweight People to Low Energy total diet replacement Treatment (DROPLET) trial among people without diabetes, in routine practice, a total diet replacement programme (formula diets) with behavioural support proved more cost-effective than nurse-led dietary advice for long-term prevention of obesity-related diseases [62]. For diabetes remission, a total diet replacement programme was estimated to be both more cost-effective and cost-saving than standard care in the DiRECT trial, reflecting reduced need for medications and fewer diabetes complications [63].

Health benefits from weight management depend largely on long-term control of body weight. Most of the evidence cited relates to short-term outcomes, relevant to the initial weight loss induction phase of weight management. Few trials have reported data beyond 12 months, to reflect weight loss maintenance, which may demand different behavioural strategies. One large RCT of high-protein diet suggested benefit for weight loss maintenance, increasing satiety and energy expenditure, albeit for a maintenance phase of only 6 months after completing weight loss [64]. Nutrient-specific effects have been postulated, but are likely to be overwhelmed by variable behavioural responses to dietary advice [65]. Behavioural programmes help to sustain new behaviours, relationships with foods and adherence to dietary advice [66–68]. Consistent evidence is also accruing that long-term weight loss maintenance is better after more rapid early weight loss [69]. Thus, treatments effective for weight loss only in the short term may have long-term value if complemented with a good weight loss maintenance strategy. Practitioners can therefore be confident that a variety of diet types can all achieve the intended weight losses, and potentially remissions of type 2 diabetes, if their patients are able to adhere to the programme sufficiently.

The analyses contradict some popular claims about specific diets: in particular, ‘low-carb’ diets hold no overall advantage for weight loss when compared with higher-carbohydrate diets. However, we cannot conclude that any individual with type 2 diabetes, in any context, will do equally well with any diet advice, or that a skilled practitioner may not have greater success advising one diet type. The skills and empathy of practitioners may overcome any diet-specific effects on weight loss by providing consistent evidence-based support [70]. Realistic trials are required, in which individuals are offered choices, perhaps using n = 1 randomised trial designs.

Weighing benefits against risks

Food is fundamental for personal and social wellbeing, and diets can be psychologically testing. Patient preferences, culture, context and lifestyle demand open conversation and shared decision making between practitioners and patients. For either medication or diet, weighing benefits against risks is vital: treatment benefits are often overestimated but harms underestimated [71]. Although all diet types are similarly effective for weight control, health risks were not systematically reported across the studies, and could differ [72]. More rapid early weight loss with more intensive programmes is associated with better longer-term weight outcomes [69], but severe caloric restriction without attention to nutrient content can have unwanted effects. Blood pressure falls with weight loss, and postural hypotension, common in older people and those with diabetes, is aggravated during rapid weight loss if diuretic or antihypertensive drugs are taken concurrently [73]. Hypoglycaemia is possible if hypoglycaemic drugs are also taken [74]. Diets other than nutritionally complete formula diets could incur vitamin and mineral deficiencies [75]. With ketogenic diets, heart failure and neurological problems from thiamine deficiency have been reported [76, 77], as well as reduced intakes of folate, iron and magnesium [12]. Replacing high-carbohydrate foods with red or processed meat (high animal protein and fat) increases sodium and long-chain saturated fat intakes, elevating LDL-cholesterol [15, 16] and potentially increasing cardiovascular disease risk [78–80]. High protein intake has been associated with kidney diseases in several observational studies [81]. Metabolic ketoacidosis with ketogenic diets is a hazard, particularly with sodium−glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors [82–87]. Meanwhile, extreme fat avoidance provokes cholelithiasis [88].

Remission of type 2 diabetes

Current evidence on diets for type 2 diabetes remission is more limited. Only two RCTs had remission as the pre-specified outcome, both relatively large and using almost identical designs and diets, with very similar results, but in very different populations, notably with different durations of diabetes [51, 53, 89]. A large majority can achieve remission if they maintain sufficient weight loss.

NRSs (non-RCT, single-arm intervention) reported remission rates ranging from 3% to 75% by ITT, over various follow-up durations. The highest remission rates, up to 75%, were in people with newly diagnosed diabetes or with <2 years of type 2 diabetes duration. Much lower 20–22% remissions were reported with longer type 2 diabetes duration (8 years) or a very brief diet period (1 week). However, these studies did not all fully ascertain remission status, and they had critical risks of bias due to lack of comparator groups and/or randomisation. NRSs reflect performance among those who select and can adhere to a particular diet, and so usually reported better results than those featuring random assignment. In some cases, remission rates were reported for completers only, rather than using the ITT population to properly guide healthcare practice and policy. Despite extracting baseline data for ITT analysis, residual bias/confounding may remain with these study designs.

The main contributor to HbA1c reduction and remission appears to be weight loss, irrespective of diet type. From the high-quality studies with high GRADE certainty, structured programmes with an intensive induction phase with total diet replacement were effective. Remission of diabetes occurs when a patient no longer satisfies the diagnostic criteria, without receiving glucose-lowering medication. To ascertain remission for those already prescribed glucose-lowering drugs, a therapeutic trial of withdrawing medication is necessary, with an appropriate protocol for re-introduction if necessary. Confirmation over a defined duration (e.g., 6 or 12 months) will be required for re-classifying individuals, and for legal or insurance purposes. The diagnostic HbA1c cut-off for diabetes of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) was defined by WHO as broadly the level where diabetes-specific microvascular complications start to emerge [90, 91]. However, many people in remission from type 2 diabetes remain in the pre-diabetes range of HbA1c, where cardiovascular disease risk begins to rise [92, 93]. Lowering HbA1c to very low levels with multiple medications among people with longstanding disease is associated with increased mortality rate, possibly by relative hypoglycaemia provoking arrythmias [94]. No such concerns have been reported in the small numbers who achieved and sustained HbA1c < 42 mmol/mol (<6.0%) from diet restriction [89].

Most type 2 diabetes is treated in primary care, the setting for both published remission trials using an intensive ‘total diet replacement’ induction phase with formula diets [51]. Simpler food-based programmes may be effective. A service evaluation from one UK general practice reported weight loss and remission in 59 out of 128 patients who opted for, and persisted with, LCD advice for a mean 23 months [95]. This completers’ analysis omits information about numbers who declined the diet, who started but failed to persist and who did not provide outcome data at designated times. The LCD was routinely offered since 2013, and the total number of patients with type 2 diabetes was 473 at the time of evaluation, so these data imply that 12.5% of the practice achieved remission [95]. A population-based cohort study from 49 general practices in the UK (the Anglo–Danish–Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care [ADDITION-Cambridge]) included 867 participants with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes; after being followed up for 5 years, there was an overall 30% remission (n = 257/867; ITT analysis). Loss of >10% of baseline body weight in the first year after diagnosis was associated with 70% higher chance of remission at 5 years [96]. Every 1 kg of weight loss was associated with 7% higher chance of remission at 5 years, regardless of specific diet regimens or lifestyle interventions [96]. There is therefore consistent evidence that remission should be attempted as early as possible from diabetes diagnosis [70, 96].

Limitations

AMSTAR 2 assesses the quality of meta-analyses, prioritising critical domains, where errors and bias can impact pooled findings (ESM Table 2). Only one or two flaws can label a meta-analysis ‘low’ or ‘critically low’, with some criteria potentially subjective (e.g., adequacy of the literature search; ESM Table 2). In the umbrella review, many meta-analyses were of ‘low’ and ‘critically low’ AMSTAR 2 quality, predominantly through ‘no protocol reported’ (despite clear and sound methods) and no assessment of publication bias. Many meta-analyses had fewer than ten RCTs to permit assessment of publication bias by funnel plot [97]. If AMSTAR 2 criteria are relaxed for protocol reporting and publication bias, the meta-analyses allow some confidence in the consistent findings of little/no difference in weight loss between any diets.

Although the search strategy was wide and not language-restricted, most studies included European participants; results may not be equally applicable to other ethnic and/or deprived communities. South Asians develop type 2 diabetes at younger ages, more rapidly and with lower BMI, so may be more sensitive to weight loss, with physiological differences in insulin resistance, body composition and fat oxidation [98, 99].

The criteria used in the reported meta-analyses and studies focused on specific diet types. However, not all reported sufficient detail about macronutrient or micronutrient contents, or prescribed and reported energy intakes, including energy intake of nutrient-restricted ad libitum diets, which limits interpretation and transferability of results. Control diets used in the meta-analyses and source RCTs also varied, including ‘usual’ diets in different countries, as well as specified dietary regimens (Table 1). Despite this, differences in weight loss between intervention and control diets, commonly 0–2 kg, are of little clinical significance. Durations of interventions varied: as weight regain is frequent over a longer period, heterogeneity might be expected. However, duration did not introduce heterogeneity, probably because trials with longer follow-up tended to be evaluating more intensive interventions with greater initial weight loss, such that the net weight changes at endpoint are similar to short-term trials.

Given the extent of literature concluding that differences in weight control or HbA1c from different diet compositions are not clinically significant, future trials of similar diet comparisons are unlikely to add useful information. Instead, evidence from clinical practice is needed to identify safe and effective approaches to achieve and maintain weight loss with available skills and training, to assess long-term outcomes from high-quality trials and prospective audits of practice with different diets. Interpretating the existing data might be enhanced through individual patient data meta-analysis. Alternatively, the very large amount of work entailed in conducting repeated meta-analyses, and the limitations of different inclusion criteria and detailed methods, support a prospective meta-analysis approach [100, 101]. All primary studies for inclusion should use an RCT design, with data analyses conducted ‘blind’. They should define the intervention clearly (e.g., diets, physical activity, and behavioural and psychological support), and address separately the induction (usually 3–6 months) and maintenance (≥12 months) phases of weight management, potentially employing different methods within a treatment programme.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 815 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank O. Wu, Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Complex Reviews Support Unit (CRSU), University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, for providing expert advice on an internal review of the manuscript.

Authors’ relationships and activities

CC is supported by a PhD scholarship from the Prince of Songkla University, Faculty of Medicine, Thailand. JH and AR declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work. SJG is undertaking trials of interventions to promote weight loss and weight loss maintenance for people living with or at risk of diabetes, for which the interventions are provided by WW (Weight Watchers UK). He has received fees from Astra Zeneca and Napp for speaking at educational meetings. The University of Cambridge has received salary support in respect of SJG from the NHS in the East of England through the Clinical Academic Reserve. EC has received funds from Filippo Berio. MEJL has received departmental research support from Diabetes UK, Cambridge Weight Plan and Novo Nordisk, and consultancy fees and support for meeting attendance from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Merck, Sanofi and Oviva.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews

- DiRECT

Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations

- ITT

Intention to treat

- LCD

Low-carbohydrate diet

- LFD

Low-fat diet

- MUFA

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- NRS

Non-randomised study

- VLED

Very low energy diet

- WMD

Weight mean difference

Contribution statement

CC, EC, AR and MEJL conceptualised the idea, as part of a programme of evidence synthesis conducted by the Nutrition and Diabetes Study Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, to inform new Dietary Guidelines. CC, JH and EC were responsible for the umbrella review of published meta-analyses for weight loss, and the systematic review of trials for diabetes remission. CC, JH, EC, AR, SJG and MEJL were involved with the interpretation of results. CC wrote the initial draft, with critical revision and comments from JH, AR, SJG, EC and MEJL. All authors approved the submission of the final manuscript. MEJL is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data analysed during this work are included in this published article and its ESM file, and in the relevant references.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kahn SE, Cooper ME, Del Prato S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1068–1083. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62154-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor R, Al-Mrabeh A, Zhyzhneuskaya S, et al. Remission of human type 2 diabetes requires decrease in liver and pancreas fat content but is dependent upon capacity for beta cell recovery. Cell Metab. 2018;28(4):547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lara-Castro C, Newcomer BR, Rowell J, et al. Effects of short-term very low-calorie diet on intramyocellular lipid and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects. Metabolism. 2008;57(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AK, Kontopantelis E, Emsley R, et al. Life expectancy and cause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study quantifying relationships in ethnic subgroups. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):338–345. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Diabetes Federation (2017) IDF Diabetes Atlas. Available from www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 10 Oct 2019

- 6.Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, Chen MJ, Mathers JC, Taylor R. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia. 2011;54(10):2506–2514. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thom G, Messow CM, Leslie WS, et al. Predictors of type 2 diabetes remission in the diabetes remission clinical trial (DiRECT) Diabet Med. 2021;38(8):e14395. doi: 10.1111/dme.14395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Mrabeh A, Hollingsworth KG, Shaw JAM, et al. 2-year remission of type 2 diabetes and pancreas morphology: a post-hoc analysis of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(12):939–948. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30303-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association 8. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S100–S110. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson PA, Twenefour D, Breen C, et al. Diabetes UK evidence-based nutrition guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes. Diabet Med. 2018;35(5):541–547. doi: 10.1111/dme.13603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churuangsuk C, Kherouf M, Combet E, Lean M. Low-carbohydrate diets for overweight and obesity: a systematic review of the systematic reviews. Obes Rev. 2018;19(12):1700–1718. doi: 10.1111/obr.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churuangsuk C, Griffiths D, Lean MEJ, Combet E. Impacts of carbohydrate-restricted diets on micronutrient intakes and status: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(8):1132–1147. doi: 10.1111/obr.12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlak R, Lester SE, Babatunde T. The prevalence of cobalamin deficiency among vegetarians assessed by serum vitamin B12: a review of literature. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(5):541–548. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churuangsuk C, Lean MEJ, Combet E. Low and reduced carbohydrate diets: challenges and opportunities for type 2 diabetes management and prevention. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020;79(4):498–513. doi: 10.1017/S0029665120000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu S, Williams PT, Krauss RM. Effects of a very high saturated fat diet on LDL particles in adults with atherogenic dyslipidemia: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elidottir AS, Halldorsson TI, Gunnarsdottir I, Ramel A. Dietary intake and cardiovascular risk factors in Icelanders following voluntarily a low carbohydrate diet. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0156655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Churuangsuk C, Lean MEJ, Combet E. Carbohydrate knowledge, dietary guideline awareness, motivations and beliefs underlying low-carbohydrate dietary behaviours. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14423. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70905-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Reeves BC, et al. Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(1):49–62. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenzie JE, Brennan SE (2020) Chapter 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 6.1 [updated September 2020]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.Cochrane-handbook.org (or updated version when available: see http://training.cochrane.org/handbook)

- 24.Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Schunemann HJ, Sultan S, Santesso N. Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. Evid Based Med. 2017;22(3):85–87. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan B, Wu Y, Yang Q, et al. The impact of major dietary patterns on glycemic control, cardiovascular risk factors, and weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 2019;12(1):29–39. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ajala O, English P, Pinkney J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(3):505–516. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.042457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan YF, Di HJ, Chen GF, Mao XD, Liu C. Effects of low carbohydrate diets in individuals with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(6):11166–11174. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeiffer AFH, Pedersen E, Schwab U, et al. The effects of different quantities and qualities of protein intake in people with diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):365. doi: 10.3390/nu12020365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian F, Korat AA, Malik V, Hu FB. Metabolic effects of monounsaturated fatty acid-enriched diets compared with carbohydrate or polyunsaturated fatty acid-enriched diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(8):1448–1457. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao WT, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Zhao TT. High protein diet is of benefit for patients with type 2 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(46):e13149. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snorgaard O, Poulsen GM, Andersen HK, Astrup A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000354. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huo R, Du T, Xu Y, et al. Effects of Mediterranean-style diet on glycemic control, weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors among type 2 diabetes individuals: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(11):1200–1208. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng Y, Bai H, Wang S, Li Z, Wang Q, Chen L. Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McArdle PD, Greenfield SM, Rilstone SK, Narendran P, Haque MS, Gill PS. Carbohydrate restriction for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2019;36(3):335–348. doi: 10.1111/dme.13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viguiliouk E, Kendall CW, Kahleova H, et al. Effect of vegetarian dietary patterns on cardiometabolic risk factors in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(3):1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zafar MI, Mills KE, Zheng J, et al. Low-glycemic index diets as an intervention for diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(4):891–902. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korsmo-Haugen HK, Brurberg KG, Mann J, Aas AM. Carbohydrate quantity in the dietary management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(1):15–27. doi: 10.1111/dom.13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Kuijpers T, Pijl H. Effects of low-carbohydrate- compared with low-fat-diet interventions on metabolic control in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review including GRADE assessments. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(2):300–331. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sainsbury E, Kizirian NV, Partridge SR, Gill T, Colagiuri S, Gibson AA. Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naude CE, Schoonees A, Senekal M, Young T, Garner P, Volmink J. Low carbohydrate versus isoenergetic balanced diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e100652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldenberg JZ, Day A, Brinkworth GD et al (2021) Efficacy and safety of low and very low carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trial data. BMJ 372:m4743. 10.1136/bmj.m4743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Noronha JC, Nishi SK, Braunstein CR et al (2019) The effect of liquid meal replacements on cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 42(5):767–776. 10.2337/dc18-2270 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Rehackova L, Arnott B, Araujo-Soares V, Adamson AA, Taylor R, Sniehotta FF (2016) Efficacy and acceptability of very low energy diets in overweight and obese people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Diabet Med 33(5):580–591. 10.1111/dme.13005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Vitale R, Kim Y. The effects of intermittent fasting on glycemic control and body composition in adults with obesity and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2020;18(10):450–461. doi: 10.1089/met.2020.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welton S, Minty R, O'Driscoll T, et al. Intermittent fasting and weight loss: systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(2):117–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carter S, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. The effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; a pragmatic pilot trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;122:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter S, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. Effect of intermittent compared with continuous energy restricted diet on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180756. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kahleova H, Belinova L, Malinska H, et al. Eating two larger meals a day (breakfast and lunch) is more effective than six smaller meals in a reduced-energy regimen for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover study. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1552–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gregg EW, Chen H, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2012;308(23):2489–2496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.67929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]