Abstract

Introduction:

Microbiome status is considered an important factor that contributes to obesity. Investigations have shown that the oral microbiome comprises a vast array of bacterial species that can influence human health.

Objective:

To determine the association between the presence of the bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes and the body mass index (BMI) status of normal, overweight and obese subjects in Duhok, Iraq. Additionally, to investigate the composition of oral Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes profiles for individuals with different BMI statuses.

Methods:

A total of 155 saliva samples were collected from participants in Duhok, Iraq. Bacterial genomic DNA was then extracted from the collected saliva. The presence of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla was detected via polymerase chain reaction.

Results:

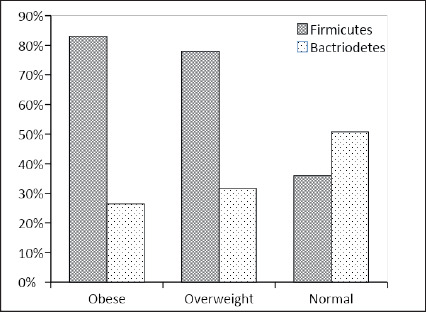

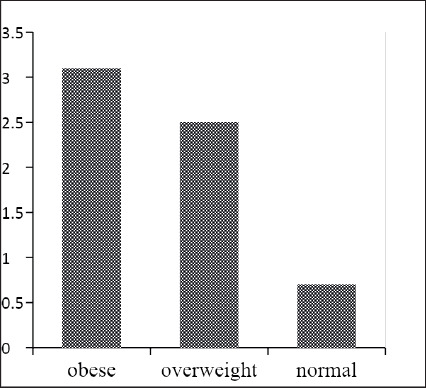

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were detected in 63.2 and 37.4% of the population, respectively. Differences in the carriage rates of oral Firmicutes in overweight (78%) and obese individuals (83%) were statistically significant when compared to normal weight individuals (36%) (P<0.0001). The percentage rates of Bacteroidetes in obese individuals (26.4%) was statistically significant when compared to normal weight individuals (50.8%) (P=0.0078). The Firmicutes/ Bacteroidetes ratios (obese=3.1, overweight= 2.5 and normal weight=0.7) were higher with increasing BMI.

Conclusion:

This study provides evidence of the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio growing with increasing BMI. High rates of Firmicutes could serve a role in the development of obesity. Further studies are required to clarify the exact relationship between oral bacteria and obesity, which could lead to a promising therapeutic method for improving the physical health of humans.

Keywords: Obesity, oral bacteria, firmicutes, bacteroidetes, Iraq

Introduction

Obesity rates are increasing among people worldwide.1,2 In Europe, the prevalence of obesity has risen from 10 to 40% in the last 10 years.3 At the simplest level, obesity is a change in the natural energy balance that can lead to an increase in energy consumption and excess fat accumulation in the body. Thus, it can have a negative impact on health and is associated with early mortality, which contributes to significant medical and social costs.4 Several studies have been conducted to identify the main factors contributing to obesity development.5 The interaction between genetics and the environment is the result of complex pathological adaptations by cells in the human body and represents the most crucial factor contributing to obesity.6 There are several pathophysiological mechanisms behind systemic metabolic dysfunctions. Mechanisms that contribute to obesity include insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.7 In the past decade, the association between the microbiome and the increased risk of obesity has received considerable attention.8 The gut contains bacteria belonging to the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria. According to recent studies, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes mainly disturb human nutrition and metabolism.9 Studies of human gut microbiota in obese individuals have shown that the guts of obese individuals had a higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B).10 However, several studies failed to observe a significant alteration in the F/B ratio between normal weight and obese individuals.11,12

Although most studies have focused on intestinal microbiota, all gastrointestinal bacteria enter through the oral cavity, with some of these transients localising there.13 The oral microbiome serves a role in the occurrence of various diseases in humans and is composed of a vast array of bacterial species that interact in complex ways.14 In 2009, the first association between the oral microbiome and obesity was highlighted.13 Further investigations have shown differences in the oral microbiome compositions of obese individuals.15,16 It was found that the salivary microbiome has a higher phylogenetic diversity in obese individuals.8,17,18 Iraq has obesity rates of approximately 8% in males and 19% in females.19 However, there are no data related to obesity and the oral microbiome in Iraq. Hence, the present study aimed to assess and analyse differences in the composition of oral Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla among individuals with different body mass indexes (BMIs) in Duhok city, Kurdistan Region, Iraq by using a molecular approach.

Methods

Study Design and Sample Collection

The present study was conducted between September 2018 and September 2019 in Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. A total of 155 saliva samples were collected from adult participants (69 males and 86 females) aged between 19–35 years. All participants completed a brief questionnaire and were then tested for their BMI. Based on the World Health Organization guidelines.20 participants were grouped into three categories according to their BMI. These categories include normal weight individuals (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight individuals (BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2) and obese individuals (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2).

Before sampling (between 9:00 and 11:00 am), participants refrained from drinking and eating, and the mouth was rinsed with water to remove any food residue. After 10 min, 5 ml of unstimulated whole saliva was collected in a 50 mL DNA-free sterile container and then transported to a laboratory for further investigation. 18 The exclusion criteria were severe periodontal destruction, the existence of any systemic disease, use of medications, smoking, pregnancy/lactation, not using antibiotics (the last 3 months), any chronic illness (e.g., psychiatric disorders, anorexia, acute relapse, etc.). Also, individuals with an inadequate quantity (<2 mL) or insufficient quality (concentrated) of saliva were excluded.

Genomic DNA Extraction

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from human saliva samples using a commercial DNA purification kit (A1620) (Promega, Germany), according to the manufacturers recommendations. Briefly, 2 ml of saliva sample was centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 2 min, and the pellet was suspended in 480 μl of 50 mM EDTA. Then, 120 μl of lysozyme (10 mg/ml) was added and gently mixed using a pipet. Next, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 40 min, centrifuged for 2 min at 16,000 xg and the supernatant was removed. Thereafter, 600 μl of nuclei lysis solution was added, gently mixed using a pipet and incubated at 80°C for 5 min. RNase solution (3 μl) was then added and incubated at 37°C for 40 min. Then, 200 μl of protein precipitation solution was added and mixed vigorously for 20 sec. The samples were then cooled on ice for 5 min and centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 3 min. The supernatant (genomic DNA) was then transferred into a new tube and 600 μl of isopropanol was added and gently mixed by inversion until thread-like strands of DNA were formed. The mixture was then centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 2 min. At this point, the supernatant was poured off. Then, 600 μl of 70% ethanol was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 2 min. Next, the supernatant was poured off and 100 μl of DNA rehydration solution was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The DNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific - USA).

Polymerase Chain Reaction

The detection of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes from saliva samples was performed via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). FirmF (5’GCGTGAGTGAAGAAGT3’) and FirmR (5’CTACGCTCCCTTTACAC3’ primers were used to detect the Firmicutes phylum (161 bp).21 BactF (5’AACGCTAGCTACAGGCTTAACA3’) and BactR (5’ACGCTACTTGGCTGGTTCA3’) primers were used to detect the Bacteroidetes phylum (396 bp).22-24 PCR amplification reactions were prepared for a final volume of 20 μl and contained the following: 10 μl PCR master mix (Promega - USA), 7 μl nuclease-free deionised water, 1 μl of each forward and reverse primer (10 pmol/μl) and 1 μl of genomic DNA (25-50 ng/μl). For the detection of the Firmicutes, the reaction was started with one cycle at 95°C for 5 min for denaturation, followed by 35 cycles consisting of 45 sec of denaturation at 94°C. Annealing was performed at 60°C for 30 sec, with a 45- sec extension at 72°C and a final 7-min cycle at 72°C. For Bacteroidetes detection, the reaction was started with one cycle at 95°C for 5 min to achieve denaturation, followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation for 30 sec at 94°C, annealing for 20 sec at 65°C, extension for 60 sec at 72°C and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were run on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel (Amersham - USA) at 65 V for 40 min. Agarose gels were stained by ethidium bromide at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml for 40 min.25 DNA bands were visualised under UV light at 366 nm. The sizes of PCR products were assessed by a (100-1500 bp) DNA ladder (Atom Scientific - UK).

Ethics Statement

This study and its protocol for obtaining consent were approved by the Scientific Committee of the College of Sciences, University of Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq (amended in September 2018). Consent was obtained from the patients recruited for this study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the chi-squared test. The statistical analysis was performed using Minitab 18 software. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

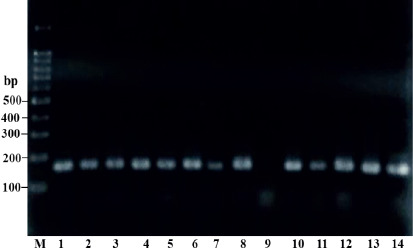

The salivary samples for all 155 participants were screened for the presence of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes using PCR. Two sets of universal oligonucleotide primers were used to detect Firmicutes (FirmF and FirmR) and Bacteroidetes (BactF and BactR) by targeting 16S rRNA. DNA was successfully extracted from all saliva samples. All DNA was examined via PCR analysis. The PCR products were run and then visualised via agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products with an expected size of ~ 161 bp were considered positive for Firmicutes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. 1% agarose gel analysis showing the amplicon bands from the PCR product of Firmicutes. Lanes: M, 100 bp DNA marker; 1–14, (except line 9; negative) ~161 bp fragments amplified using FirmF and FirmR primers for screened DNA samples.

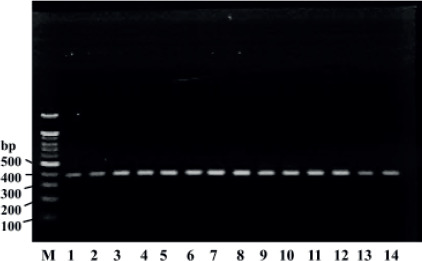

PCR fragments of ~396 bp were deemed positive for Bacteroidetes (Figure 2). The 155 participants were divided into three groups: 61 normal weight individuals (control group; BMI = 18. 5-24. 9 kg/2), 41 overweight individuals (BMI=25.0-29.9 kg/m2) and 53 obese individuals (BMI >30 kg/m2).

Figure 2. 1% agarose gel analysis showing the amplicon bands from the PCR product for Bacteroidetes. Lanes: M, 100 bp DNA marker; 1-14, ~396 bp fragments amplified using BactF and BactR primers for screened DNA samples.

Overall, 98/155 (63.2%) of the participants were positive for Firmicutes and 58/155 (37.4%) were positive for Bacteroidetes. Moreover, 34/155 (21.9%) of the participants were positive for both Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. The relative abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes substantially varied between the different BMI categories. Overall, the carriage rates of oral Firmicutes bacteria were 36, 78 and 83% in normal weight, overweight and obese individuals, respectively (Table 1). The differences in Firmicutes carriage rates among these categories were statistically significant (P<0.0001).

Table 1. Distribution of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in obese, overweight and normal weight individuals.

|

BMI groups |

Firmicutes |

P * |

Bacteroidetes |

P * |

F/B *** |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total population (n=155) |

Positive n(%) |

Negative n(%) |

Positive n(%) |

Negative n(%) |

|||

|

Normal (n=61) |

22 (36) |

39 (64) |

31 (50.8) |

30 (49.2) |

0.7 |

||

|

Overweight (n=4l) |

32 (78) |

9 (22) |

<0.0001 |

13 (31.7) |

28 (68.3) |

0.0560 |

2.5 |

|

Obese (n=53) |

44 (83) |

9 (17) |

<0.0001 |

14 (26.4) |

39 (73.6) |

0.0078 |

3.1 |

|

Male population (n=69) | |||||||

|

Normal (n=29) |

8 (27.8) |

21 (72.4) |

14 (48.3) |

15 (51.7) |

0.57 |

||

|

Overweight (n=23) |

19 (82.6) |

4 (17.4) |

<0.0001 |

5 (21.7) |

18 (78.3) |

0.0484 |

3.8 |

|

Obese (n=17) |

10 (58.8) |

7 (41.2) |

0.0361 |

6 (35.3) |

11 (64.7) |

0.3912 |

1.7 |

|

Female population (n=86) | |||||||

|

Normal (n=32) |

14 (43.8) |

18 (56.2) |

18 (56.3) |

14 (43.7) |

0.77 |

||

|

Overweight (n=18) |

13 (72.2) |

5 (27.8) |

0.0525 |

8 (44.4) |

10 (55.6) |

0.4225 |

1.6 |

|

Obese (n=36) |

34 (94.4) |

2 (5.6) |

<0.0001 |

8 (22.2) |

28 (77.8) |

0.0039 |

4.3 |

P-value of Firmicutes carriers compared to normal weight individuals.

P-value of Bacteroidetes carriers compared to normal weight individuals.

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in positive carriers.

The percentage rates of Bacteroidetes among the normal weight, overweight, obese groups were 50.8, 31.7 and 26.4%, respectively. In general, these differences were statistically significant (P=0.0184). The average abundances of both phyla in salivary samples for all BMI categories are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Average abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in the saliva samples of obese, overweight and normal weight individuals.

It was observed that the frequencies of oral Firmicutes in obese (n=44) and overweight individuals (n=32) were markedly different from that of normal weight individuals (n=22). The Firmicutes level in obese individuals (n=44) was higher than the level in overweight individuals (n=32). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.5436) (Table 1).

The phylum Bacteroidetes was significantly less abundant in obese individuals (n=14) in comparison to normal weight individuals (n=31) (P=0.0078). Also, the prevalence of Bacteroidetes in overweight individuals (n=13) was lower in comparison to normal weight individuals (n=31); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.0560).

The prevalence of Bacteroidetes in obese individuals (26.4%) was lower than that in overweight individuals (31.7%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.5738).

In the male population, the prevalence of Firmicutes in overweight individuals was higher than in obese individuals, and both of these levels were significantly higher than those of normal weight individuals (P<0.0001 and P=0.0361, respectively). However, Bacteroidetes prevalence was significantly higher in normal weight individuals than in overweight individuals (P=0.0484), but not significantly higher than in obese individuals (P=0.3912) (Table 1).

In the female population, the Firmicutes rate in obese individuals was significantly higher than in normal weight individuals (P<0.0001). No significant difference was observed between Firmicutes prevalence in overweight and normal weight individuals (P=0.0525). However, a higher prevalence of Bacteroidetes was observed in normal weight individuals. This prevalence was significantly higher than that in obese individuals (P=0.0039) but not significantly higher than that in overweight individuals (P=0.4225) (Table 1).

Generally, the phylum Firmicutes was more abundant in individuals with higher BMI, while the phylum Bacteroidetes was less abundant in such individuals. Hence, the relative abundance of the F/B ratio was also higher with increasing BMI. The F/B ratio was 3.1 (44/14) in the obese group, 2.5 (32/13) in the overweight group and 0.7 (22/31) in the control group (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Figure 4. Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in different BMI groups.

Discussion

Obesity has become a significant public health problem worldwide. Although a tremendous amount of research has focused on the causes of obesity, its exact mechanism remains to be fully elucidated.26 The interaction between genetics and the environment is the result of complex pathological adaptations by cells in the human body and represents the most essential factor contributing to obesity.6,27 Moreover, studies have noted that potential environmental impacts such as diet, energy expenditure, early life influences, sleep deprivation, endocrine disruptors, drugs, chronic inflammation and microbiome status contribute to a higher risk of obesity.28 The purpose of this study was to characterise the salivary Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes bacterial profiles of healthy individuals with different BMIs in Duhok, Iraq.

The present study used a molecular technique (PCR) and detected high levels of oral Firmicutes (63.2%) and Bacteroidetes (37.4%) among participants. The oral cavity is colonised by a complex microbiota, with the largest and most diverse group being bacteria—many of which cannot be successfully cultivated in the laboratory.29 Cultivation methods for the isolation and identification of oral bacteria require complex procedures for diagnosis, which can be time-consuming and expensive. Therefore, the detection of oral organisms is now based on molecular techniques, especially the PCR method.30,31

The upper digestive tract harbours microbes and diverse ecosystems, including the teeth, gingival sulcus, tongue, cheeks, hard and soft palates and tonsils.32 The Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD) includes 619 taxa in 13 phyla. Among these, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes and Fusobacteria are the six major phyla that contain 96% of the taxa.33 The phylum Firmicutes is almost entirely composed of gram-positive bacteria and includes five major classes: Bacilli, Clostridia, Mollicutes, Thermolithobacteria and Negativicutes.34,35 On the other hand, the phylum Bacteroidetes is characterised by gram-negative bacteria and includes four major classes: Bacteroidia, Cytophagia, Flavobacteriia and Sphingobacteria.36

In the present study, the general carriage rates of Firmicutes were significantly higher with an increase in BMI, whilst the rates of Bacteroidetes were significantly lower under the same condition. The association between salivary bacterial profile and obesity has been reported in many studies.13,15 Both obese males and females had significantly higher levels of Firmicutes and lower levels of Bacteroidetes when compared to normal weight individuals, which is in agreement with a previous study.8 The high proportion of Firmicutes may play a causative role in the development of obesity. There is strong evidence to suggest that the prevalence of Firmicutes can serve an essential role in the regulation of weight and body composition.13,37

In the present study, the oral profile of the F/B ratio was gradually more abundant with increasing BMI. The F/B was 3.1 in the obese group, 2.5 in the overweight group and 0.7 in the control group. According to the literature, evidence from several human models with participants from different countries emphasise that alterations to gut microbiota communities—particularly increases in the F/B ratio—have been observed.38-40 It is known that the presence of specific microbes in the gut (e.g., Firmicutes) can promote the absorption of monosaccharides and serve a role in the development of obesity.41,42 Similar to our findings, various studies reported consistent data regarding the F/B ratio. For example, one study noted significant differences between the two phyla in the oral cavity but not in the gut. This suggests that the oral microbiota is established with potential signatures of obesity that occur earlier than in the gut microbiota.43

However, several studies have produced contradictory results. For example, some investigations have failed to find significant alterations to the F/B ratio between normal weight and obese phenotypes.11,12,44 Piombino et al. (2014) observed a higher proportion of Bacteroidetes in the saliva of obese compared to normal weight individuals; however, this result was not statistically significant.8 Also, Schwiertz et al. (2010) observed the predominance of Bacteroidetes in the guts of both overweight and obese individuals when compared to those of normal weight.45 Such contrasting results from investigators in various parts of the world may be due to the impact of external environmental influences on human microbiota, such as geographic location, diet and physical activity.46

The majority of the Firmicutes phylum includes two main groups, known as Clostridium cluster XlVa and Clostridium cluster IV.47 Members in Clostridium cluster XIV are the primary fermenters of carbohydrates within the gut and produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as the principal end product of this fermentation. Moreover, a decrease in Clostridium cluster XIVa can result in the reduction of intestinal fermentation and fewer SCFAs or food for the intestinal epithelial cells.48,49 One possible mechanism related to how the microbiome participates in obesity is SCFAs providing additional calories when they are oxidised by the host, which leads to fat gain.50 Also, the binding and activation of G protein-coupled receptors with the released SCFA result in the secretion of hormone peptide YY (PYY).51 This hormone reduces intestinal transit time, thereby increasing the time required for nutrient absorption from the intestinal lumen.52

Several studies have shown an insulin resistance state with increased levels of plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein in obese subjects.53 Despite LPS secretion, the intestinal microbiota also produce many molecules that promote inflammation (e.g., peptidoglycans and flagellins), which activate inflammatory pathways and result in obesity and insulin resistance.54,55 Fat is considered a reservoir for inflammatory cytokines, and it has been suggested that obesity likely affects periodontal disease through this pathway.56

Furthermore, studies have shown that periodontal bacteria could induce the generation of inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor a (TNFa ), which alters the metabolism of energy to the synthesis of lipid and can thus contribute to obesity.13,57 Additionally, it was shown that the decrease in circulation C-reactive protein CRP is directly associated with the amount of weight loss. In addition to a reduction in plasma, inflammatory cytokine levels have also been directly observed after weight loss in obese phenotypes.58

It was hypothesised that oral bacteria could serve a role in obesity via three mechanisms. First, they redirect energy metabolism by increasing insulin resistance in response to increasing TNF. Secondly, bacteria increase metabolic efficiency (consuming even small amounts of calories), which causes the body to gain weight without changes in exercise and diet. Third, they can increase the appetite of the host; however, there is no research to support this theory.13

Although oral hygiene is the primary cause of oral microbial dysbiosis, antibiotic treatments can also be considered an essential factor affecting microbial composition.

Thus, any disturbance to the microbial ecosystem can change the F/B ratio, which can lead to an increase in the proportion of Firmicutes and thus a higher absorption of fats, which ultimately increases both the weight and fat proportion of the host.59

The reasons for the connection between obesity and oral bacteria are undoubtedly complex and diverse. These relationships can be indirect since they are related to diet, drugs, smoking or perhaps the return to different physiological natures of a host. This is supported by evidence of microbiota differing between obese and normal weight individuals. A potential therapy for controlling weight gain in both obese and overweight individuals via the selective modulation of microbiota using probiotics and/or prebiotics has emerged. This could be an alternative step in standard treatments such as bariatric surgery and non-surgical multicomponent approaches, which are known to have side effects and high costs. One limitation of our study is that it used PCR based analysis. Since PCR is a highly sensitive method, any form of DNA contamination can lead to the detection of unclassified microbes. Additionally, more advanced methods (e.g., 16S metagenome sequencing) could provide a more robust analysis.

Conclusion

This study provided evidence of the saliva microbiota being positively associated with obesity. Moreover, this is the first study to show that obesity is associated with oral Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes composition in the Iraqi population. Our results demonstrate that Firmicutes were more abundant in obese individuals, whilst the Bacteroidetes were dominant in the normal weight group. Moreover, individuals with higher BMI were more susceptible to the oral colonisation and retention of Firmicutes, which could be considered a factor linked to the development of obesity. Thus, obese individuals may be treated via the alteration of microbial communities in their oral cavity rather than by standard treatments such as bariatric surgery and the use of drugs that are costly and have side effects. However, further studies with larger sample sizes that include individuals with different demographic statuses may be required to clarify the exact relationship between oral bacteria and obesity. If the human oral microbiome is proven to serve a role in obesity, the next step could involve new and promising therapeutic approaches that provide a new target for improving the physical health of humans.

References

- 1.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, et al. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(9):1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism. 2019;92:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha M, Agha R. The rising prevalence of obesity: Part A: Impact on public health. Int J Surg Oncol (NY) 2017;2(7):e17. doi: 10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000;404(6778):635–43. doi: 10.1038/35007508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang WM, Kuchar S, Mozes S. Body fat and RNA content of the VMH cells in rats neonatally treated with monosodium glutamate. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35(4):383–5. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams LM. Hypothalamic dysfunction in obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(4):521–33. doi: 10.1017/S002966511200078X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, et al. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(2):85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piombino P, Genovese A, Esposito S, et al. Saliva from obese individuals suppresses the release of aroma compounds from wine. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6):105–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(31):11070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson CL, Onnerfalt J, Xu J, et al. The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(11):2257–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu HJ, Park SG, Jang HB, et al. Obesity alters the microbial community profile in Korean adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodson JM, Groppo D, Halem S, et al. Is obesity an oral bacterial disease? J Dent Res. 2009;88(6):519–23. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J, Li Y, Cao Y, et al. The oral microbiome diversity and its relation to human diseases. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2015;60(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s12223-014-0342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeigler CC, Persson GR, Wondimu B, et al. Microbiota in the oral subgingival biofilm is associated with obesity in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(1):157–64. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qadir RM, Assafi MS. Frequency of Selenomonas noxia in oral microbiota of obese and normal weight people in Duhok-Iraq. SJUOZ. 2019;7(4):120–124. doi: 10.25271/sjuoz.2019.7.4.674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita T, Kageyama S, Furuta M, et al. Bacterial diversity in saliva and oral health-related conditions: The Hisayama study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22164. doi: 10.1038/srep22164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Chi X, Zhang Q, et al. Characterization of the salivary microbiome in people with obesity. Peerj. 2018;16(6):e4458. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, et al. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . Obesity and overweight [Internet] World Health Organization; 2021. [2021 June 9; ]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight cited. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scupham AJ, Presley LL, Wei B, et al. Abundant and diverse fungal microbiota in the murine intestine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(1):793–801. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.793-801.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dick LK, Field KG. Rapid estimation of numbers of fecal Bacteroidetes by use of a quantitative PCR assay for 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(9):5695–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5695-5697.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail NA, Ragab SH, Abd Elbaky A, et al. Frequency of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in gut microbiota in obese and normal weight Egyptian children and adults. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7(3):501–7. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.23418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sellitto M, Bai G, Serena G, et al. Proof of concept of microbiome-metabolome analysis and delayed gluten exposure on celiac disease autoimmunity in genetically at-risk infants. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mamiatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J, et al. Molecular cloning-A laboratory manual. Acta Biotechnol. Vol. 5. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. p. 104. 545 S., 42 $. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komaroff M. For researchers on obesity: Historical review of extra body weight definitions. J Obes. 2016:2460285. doi: 10.1155/2016/2460285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Genetic effects in human energy expenditure components. Int J Obes. 1990;14(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franks PW, McCarthy MI. Exposing the exposures responsible for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Science. 2016;354(6308):69–73. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benn A, Heng N, Broadbent JM, et al. Studying the human oral microbiome: Challenges and the evolution of solutions. Aust Dent J. 2018;63(1):14–24. doi: 10.1111/adj.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giovannoni SJ, Britschgi TB, Moyer CL, et al. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature. 1990;345(6270):60–3. doi: 10.1038/345060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Lillo A, Booth V, Kyriacou L, et al. Culture-independent identification of periodontitis-associated Porphyromonas and Tannerella populations by targeted molecular analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(12):5523–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5523-5527.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50(4):353–80. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, et al. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(11):5721–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51(2):221–71. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf M, Muller T, Dandekar T, et al. Phylogeny of Firmicutes with special reference to Mycoplasma (Mollicutes) as inferred from phosphoglycerate kinase amino acid sequence data. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(3):871–5. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Euzéby J, et al. Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; Phylum XIV. Bacteroidetes phyl. nov; pp. 2010pp. 25–469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boutaga K, Savelkoul PH, Winkel EG, et al. Comparison of subgingival bacterial sampling with oral lavage for detection and quantification of periodontal pathogens by realtime polymerase chain reaction. J Periodontol. 2007;78(1):79–86. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sweeney TE, Morton JM. The human gut microbiome: A review of the effect of obesity and surgically induced weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):563–9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathur R, Barlow GM. Obesity and the microbiome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(8):1087–99. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1051029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koliada A, Syzenko G, Moseiko V, et al. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, et al. Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):460–9. doi: 10.4065/83.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tehrani AB, Nezami BG, Gewirtz A, et al. Obesity and its associated disease: A role for microbiota? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craig SJC, Blankenberg D, Parodi ACL, et al. Child weight gain trajectories linked to oral microbiota composition. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14030. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31866-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(11):1720–4. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, et al. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(1):190–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dugas LR, Fuller M, Gilbert J, et al. The obese gut microbiome across the epidemiologic transition. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2016;13(2):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12982-015-0044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–80. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(4):2365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan ZE, Kang DW, et al. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27(2):201–14. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):58–65. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Interactions between gut microbiota and host metabolism predisposing to obesity and diabetes. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:361–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012510-175505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(43):16767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, et al. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):228–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328(5975):228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma N, Bhatia S, Sodhi AS, et al. Oral microbiome and health. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4(1):42–66. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2018.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwamoto Y, Nishimura F, Nakagawa M, et al. The effect of antimicrobial periodontal treatment on circulating tumor necrosis factor-alpha and glycated hemoglobin level in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Periodontol. 2001;72(6):774–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziccardi P, Nappo F, Giugliano G, et al. Reduction of inflammatory cytokine concentrations and improvement of endothelial functions in obese women after weight loss over one year. Circulation. 2002;105(7):804–9. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.104279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riley LW, Raphael E, Faerstein E. Obesity in the United States - Dysbiosis from exposure to low-dose antibiotics? Front Pub Health. 2013;1:69. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]