Abstract

Context

Recent evidence suggests that vasomotor symptoms (VMS) or hot flashes in the postmenopausal reproductive state and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in the premenopausal reproductive state emanate from the hyperactivity of Kiss1 neurons in the hypothalamic infundibular/arcuate nucleus (KNDy neurons).

Objective

We demonstrate in 2 murine models simulating menopause and PCOS that a peripherally restricted kappa receptor agonist (PRKA) inhibits hyperactive KNDy neurons (accessible from outside the blood–brain barrier) and impedes their downstream effects.

Design

Case/control.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Participants

Mice.

Interventions

Administration of peripherally restricted kappa receptor agonists and frequent blood sampling to determine hormone release and body temperature.

Main Outcome Measures

LH pulse parameters and body temperature.

Results

First, chronic administration of a PRKA to bilaterally ovariectomized mice with experimentally induced hyperactivity of KNDy neurons reduces the animals’ elevated body temperature, mean plasma LH level, and mean peak LH per pulse. Second, chronic administration of a PRKA to a murine model of PCOS, having elevated plasma testosterone levels and irregular ovarian cycles, suppresses circulating levels of LH and testosterone and restores normal ovarian cyclicity.

Conclusion

The inhibition of kisspeptin neuronal activity by activation of kappa receptors shows promise as a novel therapeutic approach to treat both VMS and PCOS in humans.

Keywords: menopause, hot flashes, PCOS, hypothalamus, KOR

The pulsatile secretion of GnRH drives gonadotropin release and sustains reproductive function. Pulsatile GnRH secretion is itself driven by an ensemble of pacemaker cells in the hypothalamic arcuate/infundibular nucleus, which produce kisspeptin (Kiss1) and constitute what is now termed the Kiss1 pulse generator. Kiss1 acts directly on GnRH neurons through its receptor to stimulate GnRH secretion, which in turn generates pulsatile LH (and FSH) secretion from the gonadotropes of the anterior pituitary. These Kiss1-expressing cells coexpress 2 other neuropeptides, neurokinin B (NKB) and dynorphin A. The coexpression of Kiss1, NKB, and dynorphin led to the coined acronym “KNDy” to describe this particular subset of Kiss1-expressing cells in the hypothalamus (1).

NKB and dynorphin act in concert to generate pulsatile Kiss1 secretion. Pacemaker currents expressed by KNDy neurons allow these cells to spontaneously depolarize and discharge action potentials (2), which spread throughout their neuronal network. NKB acts through recurrent facilitatory collaterals to KNDy neurons and its receptor (NK3R) to stimulate the release of Kiss1 by KNDy neurons throughout its network (3, 4). Dynorphin also acts on KNDy neurons in this network—but does so through recurrent inhibitory collaterals and kappa opioid receptors (KORs) to silence their activity following activation by NKB (4). We have proposed that a pacemaker event arising from 1 or more KNDy neurons initiates depolarization in the KNDy network and triggers trains of action potentials, which in turn stimulates GnRH and LH secretion (4). As KNDy neurons begin to secrete kisspeptin, they also secrete NKB, which activates and fully discharges the readily releasable pool of kisspeptin (and NKB) from the entire ensemble of KNDy neurons (4, 5). Dynorphin, the third cotransmitter, acts with a phase lag to silence the Kiss1 pulse generator (4, 6). Following a refractory period, the ensemble of neurons resets, and another pulse is triggered—and so on, repeatedly. Indeed, recent optogenetic studies have confirmed that KNDy neurons constitute the proximate source generator for driving pulsatile GnRH and LH secretion (7). Although direct evidence that this mechanisms of GnRH pulse generation also occurs in the human is currently lacking, indirect evidence in patients with inactivating mutations in the genes that encode for KISS1/KISS1R (8, 9) or NKB/NK3R (10–14) as well as direct evidence from primate models (15) strongly support the evolutionary conserved nature of this model in mammals.

KNDy neurons are also the direct targets for negative feedback regulation of gonadotropin secretion exerted by sex steroids, such as estradiol (E2). KNDy neurons express estrogen receptor alpha (16), as well as the progesterone (16, 17) and androgen receptors (18, 19). Accordingly, if circulating levels of E2 decline, as occurs with menopause, KNDy neurons become activated to initiate compensation (16). Kiss1 secretion becomes amplified, which induces GnRH and LH secretion, which then coaxes the ovary into producing more E2. Conversely, if circulating levels of E2 rise, KNDy neurons become inhibited to stall further E2 production (20). The diminished activity of KNDy neurons reduces pulsatile Kiss1 secretion and thereby diminishes the stimulatory drive to GnRH neurons (21), the pituitary gonadotropes and the ovary—and hence circulating E2 levels decline. This feedback loop constitutes the homeostatic mechanism that sustains physiological levels of E2 during the ovarian cycle—but regulatory function becomes disrupted when the feedback loop is disrupted, as would be the case with ovarian insufficiency (eg, menopause).

Menopause occurs as a result of the depletion of ovarian follicles that takes place with reproductive aging in females, resulting in reduced circulating levels of E2 (22). As a result of the decline of E2 production and its diminished action on key targets (eg, hypothalamus), individuals typically experience the classical symptoms of low sex steroids including vasomotor symptoms (VMS or hot flashes) (23, 24), chronic sleep disturbances, depression, and other comorbidities, which seriously compromise the quality of life of those who are afflicted (25). VMS reflect the physiological manifestations of episodic temperature dysregulation, which typically begins with the perception of feeling “too hot,” followed by compensatory sweating and peripheral vasodilation (26). VMS appear to be triggered by hyperactive KNDy neurons (27). KNDy neurons become hyperactivated following the disinhibition that results from the decline in circulating levels of E2 (16). Hypersecretion of NKB from these KNDy neurons reaches the adjacent hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, where it disrupts its homeostatic function (26–31). Unfortunately, there are few good options to treat VMS, besides postmenopausal estrogen therapy, which is contraindicated for individuals at risk for estrogen-sensitive conditions such as cancer, venous thromboembolism, and stroke (26, 32–35). Clearly, nonhormonal options for treating VMS would benefit those individuals who suffer from VMS and their comorbidities, but available nonhormonal treatments to date are suboptimal, relieving ~50% of moderate to severe symptoms as compared with a placebo effect of ~30% to 40% (36). Indeed, recent efforts directed at blocking pulsatile KNDy neuron secretion with NK3R antagonists show great promise as therapeutic options to quell VMS (28, 29) with ~80% efficacy (37); however, further evaluation of the side effect profile of NK3R antagonists is needed to validate their safety in large populations. Moreover, NK3R antagonists are but one of several strategies that could be used to block pulsatile KNDy neuronal activity and thereby prevent VMS (6, 30).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common reproductive endocrine disorders in females, affecting up to 10% reproductive age females (38) and is characterized by oligo- or anovulation, excessive androgen production, and so-called “polycystic” ovaries observed on imaging studies (38). PCOS is associated with multiple comorbid conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease (39). However, the etiology of PCOS appears to be multifactorial and remains the subject of debate and investigation (40, 41). It is well established that PCOS is associated with excess LH pulsatility, which induces excessive ovarian androgen production, one of the hallmarks of PCOS (40, 41). Pulsatile kisspeptin/GnRH and LH secretion must occur within a narrow range of amplitude and frequency to sustain normal ovarian function (ie, folliculogenesis, ovulation, and appropriate levels of circulating sex steroids) (21, 42). Excessive pulsatility from KNDy neurons may play a role in PCOS—and by inference, restraining excessive KNDy neuronal activity could ameliorate the symptoms of PCOS. There are hormonal treatments available for ameliorating the hyperandrogenism and oligomenorrhea of PCOS; however, they are only modestly effective, carry cancer risks, and do not remedy the underlying pathophysiology of PCOS (40). Surely, nonhormonal treatments that target the etiology of PCOS would be attractive alternatives to those currently available and could have the additional benefit of ameliorating some of its comorbidities. Here again, NK3R antagonists show potential as a nonhormonal therapy to treat the inciting mechanism of PCOS (43, 44); however, there are other promising strategies to restrain pulsatile KNDy neuronal activity, including kappa opioid agonists (6, 30)—perhaps most notably those agents whose activity is restricted to the periphery.

There is a new class of peripherally restricted kappa receptor agonists (PRKAs), which are kappa receptor agonists whose activity is restricted to the peripheral vasculature and thus do not appear to influence cognition, mood, or other functions of the higher nervous system (45–49). These unique compounds activate kappa receptors, which are spread widely throughout the peripheral nervous system. They also have access to areas of the brain that reside outside of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), such as the median eminence whose capillaries are fenestrated and allow relatively large, charged molecules to transit into adjacent brain regions, including the arcuate/infundibular nucleus, where KNDy neurons and some of their terminals are located (50). We argue that PRKAs could be used to restrain the hyperactive state of KNDy neurons and thus constitute a novel therapeutic approach to impede its bothersome downstream effects, such as such VMS and PCOS and their comorbidities. Here, we describe the effects of several kappa agonists, including 2 highly selective PRKAs, on gonadotropin release, body weight, and thermoregulation in 2 different murine models of human pathophysiology—1 that recapitulates the hyperactive state of KNDy neurons associated with menopause and another that simulates the classical features of PCOS. We present evidence that PRKAs inhibit KNDy neuronal function and thus may offer therapeutic benefit in treating VMS and PCOS, and perhaps other disorders of the reproductive endocrine system.

Material and Methods

Animals

Mice were group housed and maintained on a 12:12-hour light:dark cycle with standard rodent chow and water available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on the Use of Animals in Research and Teaching in the Harvard Medical School Center for Animal Resources and Comparative Medicine. Wild-type (WT) C57/Bl6 female mice were generated in the Harvard Medical School Center for Animal Resources and Comparative Medicine vivarium by breeding C57/Bl6 founder males and females obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Prenatally androgenized (PNA) female mice were produced by a method described earlier (51, 52). Briefly, female C57/Bl6 mice were paired with adult male C57/Bl6 mice overnight. The following day, the males were removed from the cage and females were monitored for signs of pregnancy. Pregnant females were divided into 2 groups and treated on days 16 through 18 of gestation with either DHT (250 µg/100 µL in sesame oil, subcutaneously [SC]) to create the PNA group or vehicle (sesame oil, Sigma) to create the control group. Female offspring from the 2 treatment groups were used in experiments.

General Methods

Surgery

Adult C57/Bl6 female mice were bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) under isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were treated with Buprenex (0.1 mg/kg, SC) and meloxicam (5 mg/kg, SC) on the day of surgery and for 48 hours after surgery; Buprenex was administered every 6 to 12 hours and meloxicam was administered every 24 hours. Mice were allowed to recover for at least 1 week before the start of experiments. For the experiments requiring body temperature (Tb) monitoring, female mice were implanted (SC) with an IPTT-300 temperature transponder (BioMedic Data Systems, Inc, Seaford, DE, USA) at the time of OVX. Temperatures from the transponder were collected with a DAS-8007 Reader and DAS-Host 8000 software (BioMedic Data Systems, Inc).

For long-term treatment experiments with difelikefalin (either 1-week treatment in OVX WT females or 28-day treatment in PNA females), mice were implanted with an Alzet osmotic pump (DURECT Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA) model 2001 (1-week duration, reservoir volume 200 µL, flow rate 1 µL/h) or 2004 (1-month duration, reservoir volume 200 µL, flow rate 0.25 µL/h) SC on the back. Pumps contained either vehicle (5% mannitol in MilliQ water) or the experimental compound dissolved in vehicle. Mice were treated with meloxicam (5 mg/kg SC) on the day of surgery and allowed at least 24 hours to recover before the start of experiments. For the 1-week treatment in OVX female mice, adult C57/Bl6 female were implanted with Alzet osmotic minipumps 8 days following OXV (n = 20). Three different infusion rates of difelikefalin were used to achieve estimated target plasma steady-state concentrations of difelikefalin of 10 nM, 30 nM, and 100 nM (n = 5 per group). Difelikefalin is an all D tetrapeptide with a zwitterionic amide moiety with low plasma protein binding (53). Its SC bioavailability was assumed to be 100% because the peptide is unlikely to be cleaved by proteases in the SC space. Because of its low plasma protein binding and resistance to proteolysis, it was assumed that its clearance would be similar to the glomerular filtration rate in normal mice, taken as 13 mL/kg/min (54). With these parameters and the initial average body weight of the animals in each group (range, 20-22 g), the necessary infusion rates and concentrations of solutions of difelikefalin to be delivered by the Alzet pumps were calculated using the equation infusion rate = clearance × steady-state concentration. For the 1-week experiment, pump (model 2001, 1 µL/h) concentrations of 0.106, 0.350, and 1.114 mg/mL provided infusion rates of 88, 265, and 884 ng/kg/min for target 10, 30, and 100 nM plasma concentrations of difelikefalin, respectively. The pumps were primed overnight before implantation and drug delivery started immediately after the procedure. Steady-state plasma concentrations of difelikefalin would be expected to be achieved in less than a day. Control animals (n = 5) were implanted with a minipump containing vehicle. Mice in this experiment were tested for LH pulses (see protocol in the following section) 24 hours and 1 week after the minipumps were implanted. For the 28-day treatment with difelikefalin experiment in PNA mice, adult ovary-intact PNA (n = 13) and control (n = 6) female mice were implanted with Alzet osmotic minipumps according to the protocol described previously in the following groups: control = vehicle (5% mannitol in MilliQ water; n = 5), PNA + vehicle (5% mannitol in MilliQ water; n = 6), and PNA with difelikefalin (n = 7). Only the 100-nM target steady-state plasma concentration of difelikefalin was studied. This was provided by an infusion rate of 884 ng/kg/min from model 2004 Alzet pumps at 0.25 µL/h flow rate loaded with 4.624 mg/mL solutions of difelikefalin. Mice were then tested for LH pulses 1 week and 28 days after the minipumps were implanted.

LH ELISA

To measure LH levels, a sensitive sandwich ELISA was used to measure LH from whole-blood samples (55, 56). A 96-well high-affinity microplate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) was coated with antibovine LH-β monoclonal antibody in 1x PBS (1:1000; catalog no. 518B7; RRID:AB_2665514; National Hormone & Peptide Program, Torrance, CA, USA) and incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Plates were blocked the next day with 5% skim milk powder in 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS (PBS-T) for 2 hours at room temperature (RT), and then washed with PBS-T. Whole blood samples and a standard curve were then added to the plates and incubated for 2 hours at RT. Standard curves were generated using a serial dilution of an LH reference preparation (AFP-5306A; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Hormone and Pituitary Program National Hormone & Peptide Program (NIDDK-NHPP), CA, USA) diluted in 0.2% BSA in 1x PBS. Plates were then washed again in PBS-T, and then incubated for 1.5 hours at RT in rabbit polyclonal anti-LH antiserum detection antibody (1:10 000 in 50% 1x PBS and 50% skim milk blocking buffer; catalog no. AFP240580Rb; RRID:AB_2665533; NIDDK-NHPP, CA, USA). The plates were then washed with PBS-T and incubated for 1.5 hours at RT with goat anti-rabbit HRP antibody (1:2000; catalog no. 1706515; RRID:AB_2617112; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After a final wash step, a solution of o-Phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in citrate buffer was added and left to incubate for 30 minutes. The reaction was stopped using 3 M hydrochloric acid. The absorbance of each plate was read at 490 nm using a Sunrise microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland). The concentration of LH in each blood sample was determined by comparing the optical density values of the experimental LH samples to the optical density values of the known LH standard curve.

LH pulses were identified using a custom MatLab code (10) that identified LH pulses based on previously published criteria of LH pulses in mice (57–59). To be considered an LH pulse, the LH value (ng/mL) of that peak must have been at least 20% greater than the LH value of 1 the of the 2 immediately preceding time points as well as being at least 10% greater than the LH value of 1 of the 2 immediately following time points. The exceptions to this rule were (1) that the second time point was only compared with the single preceding time point and the 2 following time points, and (2) the second to last time point was only compared with the 2 preceding time points and the single following time point. Once LH pulses were identified, the following parameters were determined for each treatment group: the mean pulse frequency (average number of LH pulses per the period of the test), the mean peak of LH (mean of highest 5 peaks) for each animal, and the baseline LH (mean of lowest 5 nadirs) for each animal, as described previously (60). The functional sensitivity of the ELISA assay was 0.0039 ng/mL with a coefficient of variation percent of 3.3%.

Real-time quantitative PCR protocol

The mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) and preoptic area (POA) were freshly dissected from whole brains, snap frozen, and stored at -80°C until sample processing. The tissues were homogenized and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), bromochloropropane phase separation, isopropanol precipitation, and DNase treatment. RNA purity and concentration were measured via an absorbance spectrophotometer (260/280 nm > 1.8; NanoDrop 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using random hexamers (High Capacity cDNA Synthesis Kit, Life Technologies). The mRNA levels of Tac2, Tacr3, Pdyn, and Kiss1 were determined by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using gene-specific primers (Table 1). cDNA samples, standards, and negative control reactions were run in duplicate on a QuantStudio 3 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green RT-qPCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). The RT-qPCR cycling conditions were applied accordingly: 10 minutes at 95°C, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, and annealing for 1 minute at 60°C. A terminal dissociation melt curve step was used to verify generation of a single PCR amplicon. The absence of genomic DNA contamination was ascertained using water (No Template Control) and DNase-treated RNA that did not undergo reverse transcription (No Amplification Control) as negative controls. Cycle threshold values were transformed against a standard curve of serially diluted cDNA vs cycle threshold values, normalized to the reference gene Hprt, and reported as fold change relative to control treatments.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for measurement of gene expression at the MBH and POA using RT-qPCR

| Gene | F1 | R1 | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kiss1 | AGCTGCTGCTTCTCCTCTGT | GATTCCTTTTCCCAGGCATT | AF472576.1 |

| Pdyn | ACAGGGGGAGACTCTCATCT | GGGGATGAATGACCTGCTTACT | NM_018863.4 |

| Tac2 | GCTCCACAGCTTTGTCCTTC | GCTAGCCTTGCTCAGCACTT | NM_001199971.1 |

| Tacr3 | GCCATTGCAGTGGACAGGTAT | ACGGCCTGGCATGACTTTTA | NM_021382.6 |

| Hprt | CCTGCTGGATTACATTAAAGCGCTG | GTCAAGGGCATATCCAACAACAAAC | NM_013556.2 |

Abbreviations: MBH, mediobasal hypothalamus; POA, preoptic area; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

Methods for Testing the Effect of PRKAs on LH and Behavior

OVX adult C57/Bl6 female mice were used to compare the effects of different KOR agonists on LH release in female mice. Before OVX, 4-µL blood samples were collected from the tail tip to determine the ovary-intact baseline levels of LH for each mouse. One week after OVX, female mice were treated with KOR agonists (IP) to look at the effect on LH secretion. Mice were first treated with (±)U50 488 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 10 mg/kg IP) (n = 6) and then 1 week later with (D-Ala2)-Dynorphin A (1-13)-NH2 (AlaDyn; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc, Burlingame CA; 3 mg/kg IP). Serial 4-µL blood samples were collected from the tail tip at 4 different time points on the day of testing to determine LH levels. After collection of blood samples at time point 0 (which served as the baseline for LH levels after OVX), mice were injected with a KOR agonist and blood samples were collected again at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after injection. The effect of an additional KOR agonist, difelikefalin (0.2 mg/kg IP), on LH release was also tested in a different set of OVX female mice (n = 3). Baseline tail blood samples were collected at time point 0, and then again 15, 30, and 60 minutes after injection. Blood samples were stored at -80°C until analysis of LH levels with a sensitive LH ELISA protocol (see protocol described previously).

To determine if the effects on LH secretion observed with AlaDyn were caused by the action of this peptide specifically through its action on KORs, an additional test of AlaDyn activity was performed in the presence of the selective KOR-antagonist nor-binaltrophimine dihydrochloride (nor-BNI; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN; 10 mg/kg IP) (n = 6). Blood samples were stored at -80°C until analysis of LH with an LH ELISA.

An additional set of tests were carried out in 2 groups of ovary-intact adult C57/Bl6 female mice (n = 13 for tests with AlaDyn and n = 12 for tests with difelikefalin) to determine specifically where AlaDyn and difelikefalin were acting to disrupt LH release. For tests with AlaDyn, tail blood was first collected to determine baseline LH levels in all mice on the day of testing. Then mice were injected either with kisspeptin-10 alone (mouse kisspeptin [110-119] amide; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Burlingame, CA; 7.5 nmol/100 µL, IP) (n = 4), with AlaDyn only (3 mg/kg, injected IP in 100 µL) (n = 4), or mice were injected (IP) with both kisspeptin-10 and AlaDyn (n = 5). Additional tail blood samples were collected at 4 time points after the injection (15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes) and stored at -80°C until analysis with LH ELISA (see previous protocol).

For tests with difelikefalin (provided by Peptide Logic, San Diego, CA) (0.2 mg/kg, IP), the same protocol was used in a different set of female mice (n = 4 for each group), and tail blood was collected at baseline and then 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after injection. Difelikefalin (aka CR845, FE 202845) (61, 62) is a D-amino acid tetrapeptide KOR agonist and a close analog of FE 200041 (47, 63) and FE 200665 (aka CR665) (45, 46). Difelikefalin and analogs exhibit high potency at the human KOR (sub nM), high receptor selectivity (> 10 000-fold), and high peripheral selectivity (> 500-fold) (45–47, 61–63).

Tail suspension test

To determine the effect of treatment with different KOR agonists on behavior, mice were tested for their response in a tail suspension test after treatment with different compounds (64, 65). Before the start of behavioral testing, adult ovary-intact C57/Bl6 female mice were habituated to the testing room for at least 30 minutes in their home cage. After the habituation period, mice were injected (IP) with either vehicle (5% mannitol in MilliQ water), ± U50 488 (10 mg/kg), or difelikefalin (0.2 mg/kg) 30 minutes before the start of testing. At the start of each test, small plastic cylinders (4 cm length, 1.6 cm outside diameter) were placed around the tail of each mouse to prevent climbing behavior during the tests. Mice were then individually suspended vertically from a metal shelf 15 cm above the floor of a clean cage using tape attached securely to the end of their tail 2 to 3 mm below the tail tip. The total duration of each test was 6 minutes and mice were immediately returned to their home cage at the end of the test period. Mice were tested on the tail suspension test twice (tests were randomized and separated by 3 weeks) with a different compound injected (IP) on each test day (total n for each group = 8). Behavior tests were videotaped and then scored by a trained observed that was blind to the treatment groups. To determine the effect of treatment on different escape behaviors, the total time spent immobile during each test was determined for each mouse (64).

Testing the Effect of Difelikefalin on LH Pulsatility and Tb in OVX Mice

To determine the effect of chronic treatment with difelikefalin on LH pulses and body temperature in OVX mice, ovary-intact female mice were first handled daily for 4 weeks to habituate them to the blood and temperature collection procedure. Mice (n = 20) were then bilaterally ovariectomized and implanted with temperature probes as described above. Before OVX, baseline temperature in ovary-intact females (n = 9) was monitored daily for 3 days.

The OVX mice were then implanted with the osmotic minipumps containing either vehicle (n = 5) or different infusion rates of difelikefalin (n = 5 per group as described previously). The effect of drug treatment on LH pulses and temperature was then determined by repeating the blood sampling and temperature collection protocols 24 hours and then again 1 week after the implantation of the minipumps (4 µL tail blood in 116 µL in PBS-T and temperature were collected every 10 minutes for 3 hours). Blood samples were stored at -80°C until analysis of LH pulses with a LH ELISA. The body weight of each mouse was also determined at the time of minipump implantation and after 1 week of treatment with difelikefalin.

Validation of PNA model

PNA females generated using this model display delayed vaginal opening and first estrus compared with control females (51). To validate the PNA model, female offspring (n = 6 control and n = 13 PNA females) were monitored daily for markers of puberty onset from postnatal day 21 for vaginal opening, weight at vaginal opening, and time to first estrus. To determine the time to first estrus, daily vaginal smears were collected (56). To determine the estrous cyclicity of both the control and PNA mice, daily vaginal smears were also taken for 40 days before the start of experiments. Mice were also weighed weekly for 11 weeks after postnatal day 21.

Protocol for assessing the effects of difelikefalin in PNA mice

To evaluate the regularity of estrous cyclicity in the control and PNA mice, daily vaginal smears were collected for 30 days and evaluated for histology. During this time, mice were also handled daily to habituate them to the blood sampling protocol. Mice were implanted with osmotic minipumps as described previously and divided into 3 groups: control (n = 6), PNA + vehicle (n = 6), and PNA + difelikefalin (n = 7). Estrous cycles were monitored daily in all 3 treatment groups for 28 days after minipump implantation. The number of cycles and days spent in each phase of the cycle were determined for each group during the treatment. Tail blood samples were also collected 1 week and 28 days after the implantation of the minipumps. For these experiments, blood samples (4 µL in 116 µL PBS-T) were collected every 8 minutes for 4 hours. Samples were stored at -80°C until analysis of LH pulses with a LH ELISA. On day 28 of treatment, after the blood sampling protocol was completed, the animals were euthanized, and the ovaries and brains were collected for analysis. Ovaries were stored in Bouin’s fixative, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin at the Harvard Histopathology core. Corporal lutea were counted in the middle section of each ovary. Brains were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C for RT-PCR analysis. Serum samples were also collected for analysis of testosterone levels in these mice. Serum testosterone was measured at the University of Virginia Ligand Assay core with the Mouse & Rat Testosterone ELISA assay (reportable average range 10-1600 ng/dL; sensitivity of 10 ng/dL).

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the median ± max/min values (represented by box plots) or the mean ± SEM for each group. In the box plots presented in these experiments, the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum, whereas the box represents the lower and upper quartiles with the median represented by the middle line. A 2-tailed unpaired Student t test or a 1- or 2-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s or Fisher’s post hoc test was used to assess variation among experimental groups. Significance level was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism Software 9, Inc (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Effect of PRKAs on LH Secretion

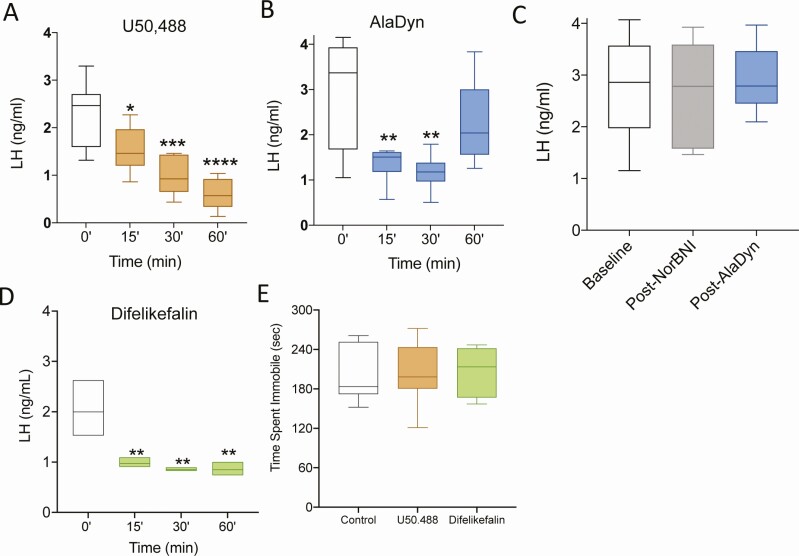

OVX female mice were used to simulate the neuroendocrine state of menopause, with its low circulating levels of E2 and high levels of gonadotropins, driven by hyperactive KNDy neurons. We examined the effects of the KOR selective agonist (±) U50 488 (10 mg/kg, IP) and the PRKA AlaDyn (3 mg/kg, IP). In rodents, (±) U50 488 readily penetrates the BBB (66), whereas AlaDyn does not (67). The incorporation of a D-amino acid in AlaDyn increases the stability to aminopeptidase degradation and blocks its ability to penetrate of the BBB (68). The KOR agonist (±) U50 488 significantly inhibited LH in OVX animals at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration (Fig. 1A). Similarly, AlaDyn inhibited LH release at 15 and 30 minutes after administration (Fig. 1B). Of note, the D-Ala2 substitution decreases the affinity of Dyn for KOR (68). To confirm that the decrease in LH observed is attributable to KOR binding, an additional group of OVX mice were pretreated with the selective KOR antagonist nor-BNI (10 mg/kg, IP) before the administration of AlaDyn. Blood was collected for serum LH before nor-BNI (baseline), 90 minutes after norBNI, and 30 minutes after AlaDyn (3 mg/kg IP) (ie, 120 minutes after nor-BNI). Nor-BNI prevented the action of AlaDyn on LH release (Fig. 1C), confirming its KOR-mediated effect.

Figure 1.

KOR agonists inhibit LH secretion without central effects. The synthetic KOR agonist (±) U50 488 (A) and the peripherally restricted KOR agonist [D-Ala2]-Dynorphin A (1-13)-NH2 (AlaDyn) (B) significantly decrease LH release. Pretreatment with the KOR antagonist nor-BNI blocked the action of AlaDyn (C). The inhibitory effect on LH was replicated by the peripherally restricted KOR agonist (PRKA) difelikefalin (D). On a tail suspension test, neither (±) U50 488 nor difelikefalin induced any discernable central effects as assessed by the tail suspension test at the doses tested (E). Values are presented as median (middle line) ± max/min (box and whiskers). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test: (A) n = 6, F (4, 24) 0.4844; (B) n = 6, F (3, 20) 2.249; (C) n = 6, F (2, 15) 0.4753; (D) n = 3, F (3, 8) 1.611. For (E) n = 8, 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test, F (2, 21) 0.028. Statistical values are compared with time 0 (A, B, and D), the baseline LH (C) or the control group (E): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, ****P < 0.001.

To affirm the generalized efficacy of PRKAs to inhibit the release of LH, we used another highly selective, peripherally restricted KOR agonist, the D-amino acid tetrapeptide, difelikefalin, in the OVX mouse. As was the case with AlaDyn, difelikefalin (0.2 mg/kg IP) inhibited LH release at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration (Fig. 1D). The action of systemically administered difelikefalin is reported to be peripherally restricted (ie, lacks the ability to penetrate the BBB) at doses higher than those used in this study (47). However, to confirm this statement, we further examined its peripherally restricted activity by testing its effects in a behavior model previously used in mice to determine the effects of different compounds on depression-related behaviors. To this end, we evaluated the effect of peripherally administered difelikefalin (IP) in a tail suspension test for 30 minutes (64, 65). At the doses used in our study, neither (±) U50 488 (able to cross the BBB) nor difelikefalin induced any apparent central effect (ie, reduce mobility), as observed by their similar immobility time posttreatment compared with controls (Fig. 1E). This experiment demonstrates that PRKAs inhibit gonadotropin secretion—and by inference Kiss1 and GnRH secretion—without exerting discernable effects on the central nervous system as assessed by the tail suspension test.

Target of PRKAs Action in the Brain-pituitary Axis

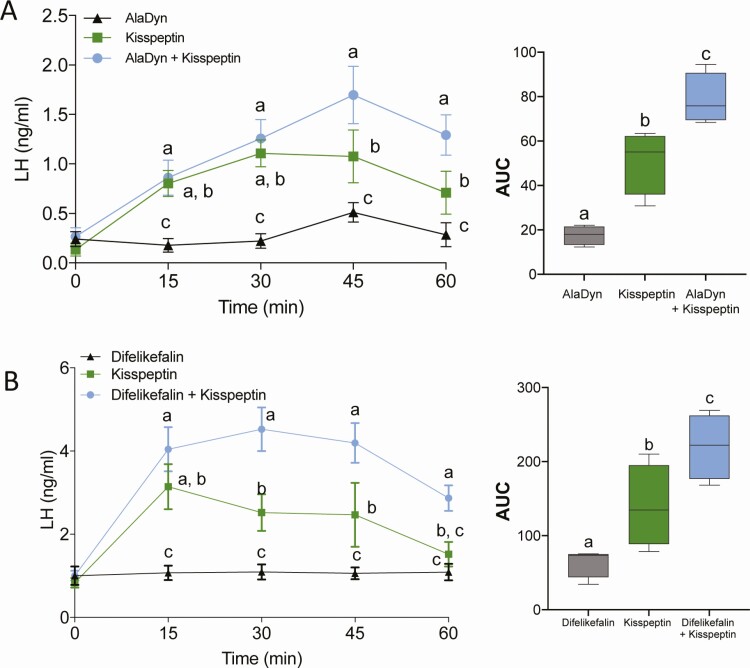

We hypothesized that the inhibitory action of PRKAs on gonadotropin secretion is exerted at the level of KNDy neurons, by virtue of their ability to penetrate the fenestrated capillaries in the mediobasal hypothalamus, where the BBB is leaky (50), and the median eminence, which is outside the BBB. To test this hypothesis, AlaDyn (3 mg/kg, IP) and difelikefalin (0.2 mg/kg, IP) were administered either alone or with mouse kisspeptin-10 (7.5 nmol, IP) in intact WT females in diestrus. We argued that if PRKAs act either on GnRH neurons or at the pituitary (ie, downstream of KNDy neurons), AlaDyn and difelikefalin would either block or reduce the stimulatory action of kisspeptin-10. Instead, these PRKAs amplified the effect of mouse kisspeptin alone (Fig. 2A-B), corroborating the idea that the effect of PRKAs is mediated by KOR acting either directly upon or proximate to KNDy neurons.

Figure 2.

PRKAs increase the response of GnRH neurons to kisspeptin. AlaDyn (A) and difelikefalin (B) amplified the response of GnRH neurons and gonadotropes to mouse kisspeptin-10. Values expressed as mean ± SEM. Groups with different letters are significantly different. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Fisher’s post hoc test. In (A) n = 4-5/group, F (2, 10) = 9.502 P = 0.0049; for (B) n = 4/group, F (2, 9) = 12.85, P = 0.0023.

Effects of PRKA on Serum Levels of LH, Tb, and the Rate of Body Weight Gain Following OVX

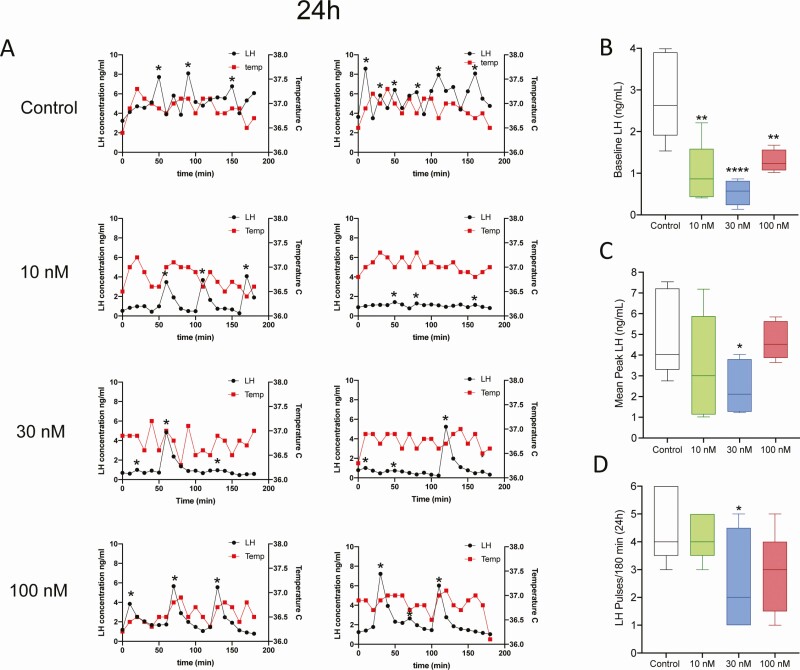

To test the feasibility of using PRKAs to inhibit of the neuroendocrine sequelae of menopause (48, 49), we examined the effects of a PRKA in OVX mice. We measured the effects of difelikefalin on mean circulating levels of LH, LH pulsatility, Tb, and the rate of weight gain in mice that were ovariectomized 1 week earlier. Following OVX but before treatment with difelikefalin, these animals exhibited increased serum levels of LH, an increase in mean Tb, and an accelerated rate of weight gain.

To establish the lowest effective infusion rate of difelikefalin, we used Alzet osmotic minipumps for a week, which continuously delivered either the vehicle (5% mannitol) or a targeted steady-state concentration of difelikefalin at 10 nM, 30 nM, or 100 nM (n = 5/group; see Methods for details on the infusion procedures). In addition, at the time of the surgery (OVX), all mice were implanted (SC) with temperature transponders. Blood samples and temperature readings were collected every 10 minutes for 180 minutes at 24 hours and 1 week after minipump implantation. The week-long treatment with difelikefalin elicited no discernable behavioral effects in any of the 3 treatment groups; all animals appeared to be healthy throughout the course of the experiment.

At 24 hours after beginning treatment with difelikefalin, baseline levels of LH were markedly reduced at all infusion rates (Fig. 3A-B). The mean peak of LH pulses was also significantly reduced at the 30 nM targeted plasma concentration (Fig. 3A,C). Likewise, the frequency of LH pulses appeared to be modestly reduced by the highest 2 infusion rates of difelikefalin, but this was statistically significant only at the 30 nM targeted plasma concentration (Fig. 3D). At the end of the week-long treatment with difelikefalin, baseline levels of LH and the mean peak of LH pulses were both significantly reduced compared with the vehicle control at the highest targeted plasma concentration (100 nM) (Fig. 4B,C). The frequency of LH pulses was unaffected (Fig. 4A,D).

Figure 3.

Effect of 24 hours of difelikefalin treatment on LH pulsatility and body temperature in OVX mice. OVX mice were implanted with osmotic minipumps delivering target 10 nM, 30 nM, or 100 nM steady-state plasma concentrations of difelikefalin for a week (n = 5/group). (A) Depicts 2 representative samples from each group. (B) Baseline LH release during 180 minutes, F (3, 15) = 10.73, P = 0.0005. (C) Peak of LH pulses observed during 180 minutes, F (3, 16) = 2.109, P = 0.1393. (D) Number of LH pulses in 180 minutes, F (3, 16) = 2.492, P = 0.097. One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Effects of 1 week treatment with difelikefalin on LH pulsatility and body temperature in OVX mice. OVX mice were implanted with osmotic minipumps delivering target 10 nM, 30 nM, or 100 nM steady-state plasma concentrations of difelikefalin for a week (n = 5/group). (A) Depicts 2 representative samples of LH and body temperature (Tb) from each treatment group (n = 5/group). (B) Baseline LH release during 180 minutes, F (3, 15) = 2.061, P = 0.1486. (C) Peak of LH pulses observed during 180 minutes, F (3, 16) = 1.992, P = 0.1558. (D) Number of LH pulses in 180 minutes, F (3, 16) = 0.8015, P = 0.5111. One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05.

These observations demonstrate the efficacy of a highly selective PRKA to reduce LH secretion (and presumably GnRH and Kiss1 secretion)—through its actions on KOR of nerve terminals that reside outside of the BBB (eg, the median eminence). Pulsatile secretion from KNDy neurons emanates from their cell bodies, not their nerve terminals (2, 7), which may explain why difelikefalin appears to have little or no effect on the frequency of LH pulses—yet exerts a profound inhibitory effect on the serum levels of LH.

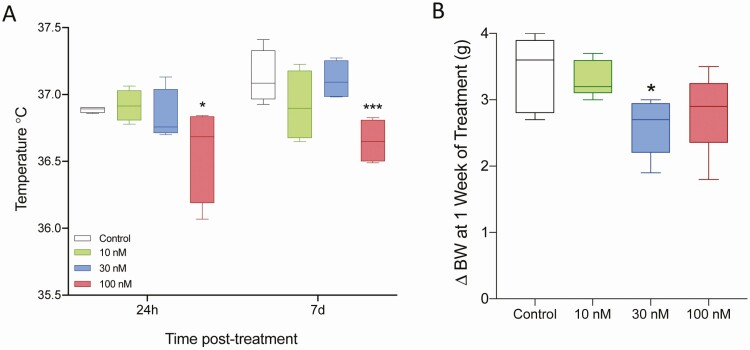

Mean (SC) Tb increased significantly in mice following OVX, rising from a baseline of 35.5°C in intact females at diestrus to nearly 37°C, reflecting the role of ovarian hormones to modify the setpoint for Tb regulation and the possible role of hyperactive KNDy neurons in mediating this phenomenon (Figs 3 and 4). Animals treated with a targeted plasma concentration of 100 nM of difelikefalin exhibited a significant decrease in their Tb 24 hours after treatment began, which persisted throughout the week-long treatment (Fig. 5A). This is compatible with a decrease in the output of KNDy neurons, which includes NKB, effectively reduces superficial temperature, associated with VMS.

Figure 5.

Effect of difelikefalin on body temperature and body weight. Body temperature (Tb) was recorded every 10 minutes for 180 minutes at 2 time points: 24 hours and 1 week after initiation of treatment (A). Target 100 nM plasma concentration of difelikefalin significantly decreased Tb at both time points, F (3, 24) = 6.076, P = 0.0032, 2-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. (B) Difelikefalin reduces the rate of increase in body weight observed following OVX, F (3, 16) = 3.064, P = 0.0582, 1-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Female mice exhibit an accelerated weight gain following OVX (69), as appears to be the case in humans (ie, with menopause in females and as a result of hypogonadism in males, having low circulating levels of testosterone [T]) (70, 71). The rate of weight gain following OVX was reduced by ~25% in mice treated with the highest infusion rates of difelikefalin, being significantly reduced in the group treated with the targeted plasma concentration of 30 nM (Fig. 5B), in line with a potential role of KNDy neurons in the increase in BW in the absence of sex steroids.

Effects of Month-long Treatment With Difelikefalin on Serum Levels of LH and T and on Ovarian Cyclicity in PNA Mice

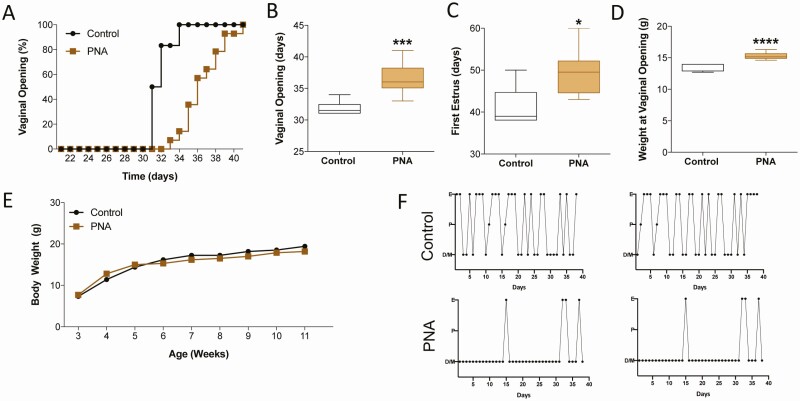

Treatment of pregnant mice with androgens gives rise to female offspring (PNA mice) that have a phenotype that resembles PCOS and is the best available murine PCOS model (51). In the present study, the PNA mice displayed the expected phenotype of having delayed puberty (ie, delayed vaginal opening and first estrus) and irregular estrous cycles as adults (Fig. 6A-F). However, this murine model of PCOS does not result in obesity (Fig. 6E). Once the mice reached adulthood, the PNA group was divided into 2 groups (PNA + vehicle: n = 6; PNA + difelikefalin: n = 7). The control group (non-PNA: n = 6) and one-half of the PNA mice were implanted Alzet osmotic minipumps with a month-long duration filled with vehicle (5% mannitol). The remaining one-half of the PNA mice (n = 7) received a similar minipump with difelikefalin that delivered a targeted steady-state plasma concentration of 100 nM for the treatment duration. This dose was selected based on our previous 1-week exposure experiments showing this targeted plasma concentration as the most efficient one long-term in OVX mice (Fig. 4). All of the mice appeared to be healthy throughout the experiment.

Figure 6.

PNA replicates a model of PCOS in adult female mice. DHT treatment prenatally (PNA) delays puberty onset in females as observed by vaginal opening (VO) (A, B) and first estrous (C). Because of the older age, body weight (BW) was significantly elevated at the time of VO in PNA mice (D), although the BW of age-matched littermates was not different at any age (E). In 2 representative examples of estrous cycles in controls (treated with oil prenatally) and PNA mice are depicted showing disruption of the estrous cycle with prolonged phases in diestrus (F). Values are presented as median (middle line) ± max/min (box and whiskers). Control group n = 6; PNA n = 14. Student t test. In (B) ***P = 0.001, in (C) *P = 0.0194; in (D) ****P < 0.0001.

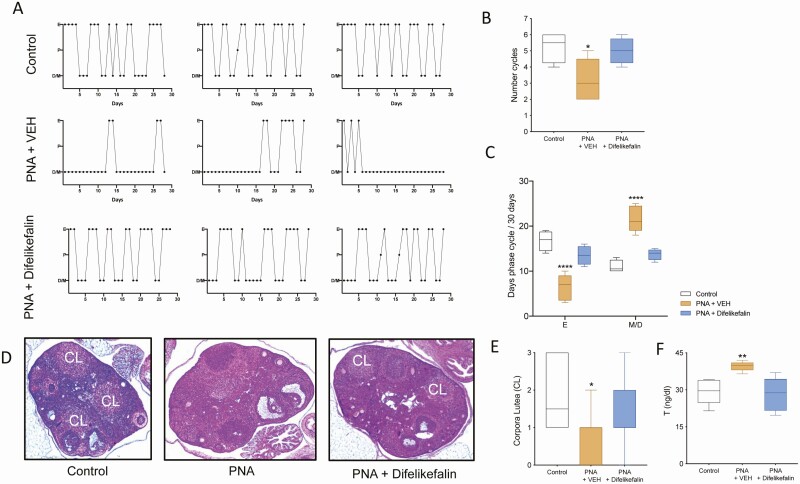

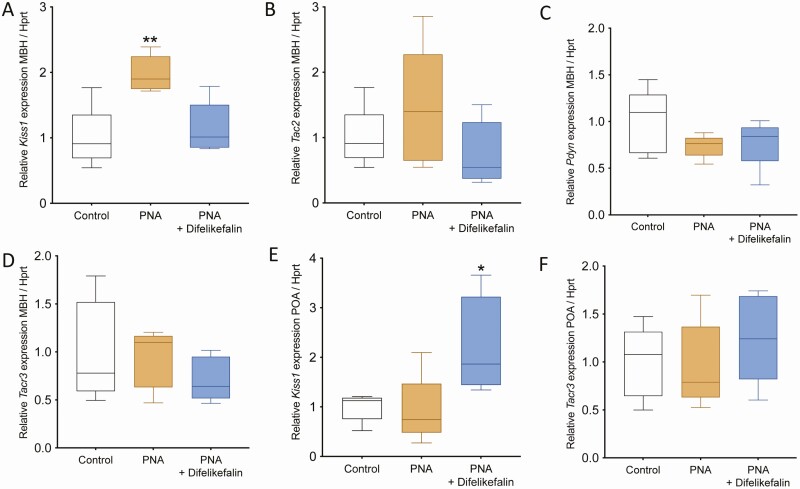

The estrous cycle of all the mice was monitored for the duration of the treatment. As expected, PNA + vehicle mice maintained a disrupted estrous cycle during treatment, which displayed fewer cycles with extended times in metestrus and diestrus and fewer days in estrus (Fig. 7A-C). However, the PNA group that received difelikefalin completely reversed their cycles to a normal state and did not differ from controls at any of the measurements (ie, number of cycles and days spent in each phase) (Fig. 7A-C). At the end of the experiment, ovaries were collected for histological determination. Corpora lutea, which are a marker of ovulation, were present in control and PNA + difelikefalin-treated mice but they were significantly fewer or absent in ovaries of the PNA + vehicle group compared with controls (Fig. 7D-E). As expected, serum levels of T were elevated in the vehicle-treated PNA mice, and difelikefalin treatment reduced T levels to that of the untreated of control (Fig. 7F). Brains were also collected for expression determination of the genes involved in GnRH pulsatility (ie, Kiss1, Tac2, Pdyn, and Tacr3). At the MBH, PNA + vehicle treatment increased Kiss1 mRNA levels by 2-fold compared with oil-treated control, whereas PNA + difelikefalin treatment restored Kiss1 to control levels (Fig. 8A). There was no effect of PNA + vehicle treatment nor PNA + difelikefalin on mRNA levels of Tac2, Pdyn, and Tacr3 at the MBH (Fig. 8B-D). At the POA, PNA + difelikefalin treatment increased Kiss1 mRNA levels by 2-fold compared with oil-treated control and PNA + vehicle (Fig. 8E). There was no effect of PNA + vehicle treatment nor PNA + difelikefalin on mRNA levels of Tacr3 (Fig. 8F), Pdyn, and Tac2 (data not shown) at the POA.

Figure 7.

Difelikefalin restores estrous cyclicity, decreases serum levels testosterone (T) levels, and induces ovulation in PNA mice. One month of chronic exposure to difelikefalin 100 nM targeted plasma concentration restored estrous cyclicity in PNA mice (A), as observed by the number of estrous cycles in 28 days (F (2, 10) = 4.990, P = 0.0314, n = 4-5, 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test) (B) and time spent in estrus vs diestrus (F (2, 20) = 50.69, P < 0.0001, n = 4-5, 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test) (C). In (D), representative samples of ovarian histology from each group are depicted. The number of corporal lutea (CL) was quantified in the middle section of each ovary (E). (F) T levels at the end of the treatment (28 days) (F (2, 12) = 7.738, P = 0.0069, n = 5/group, 1-Way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 8.

Effect of 1 month of difelikefalin treatment on Kiss1, Tac2, Tacr3, and Pdyn expression in the MBH and POA. PNA significantly increased Kiss1 expression in the MBH, which was restored by difelikefalin (100 nM targeted plasma concentration) treatment for a month (A) F (2, 12) = 9.531, P = 0.0033. The expression of Tac2 (B), Pdyn (C), and Tacr3 (D) were not significantly altered. In the POA, difelikefalin treatment significantly increased the expression of Kiss1 (E) (F (2, 12) = 5.4, P = 0.0205) but not Tacr3 (F). One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s post hoc test, n = 5/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

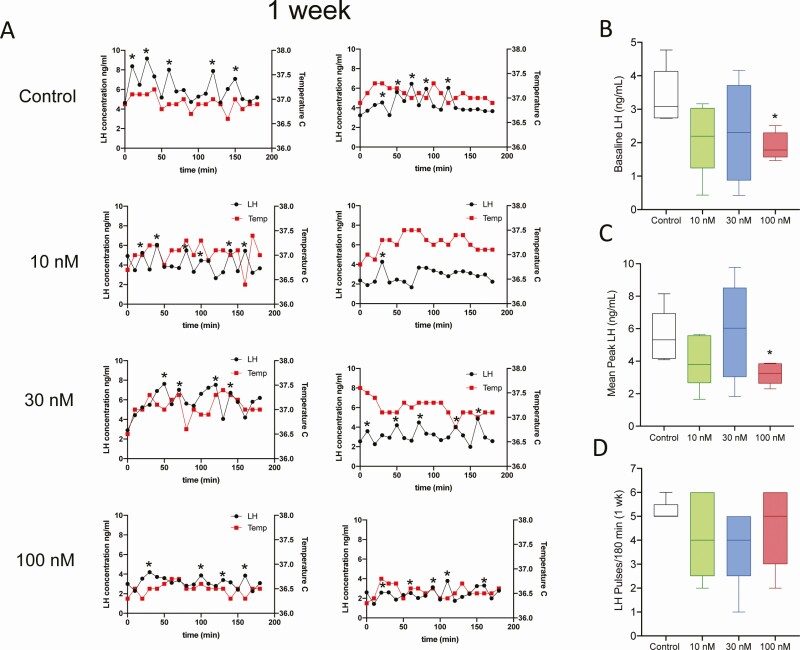

We assessed the effect of difelikefalin on LH pulsatility at 2 time points during treatment, at 1 week then again at 1 month of treatment. Blood samples were collected every 10 minutes for 240 minutes to measure serum levels of LH, as described previously. These mice all have intact ovaries, and therefore their LH pulsatility reflects each particular phase of the estrous cycle (72). LH pulsatility was compared between groups at a cycle phase that was shared by at least 3 mice in each group during the 2 periods of sampling. At the 1-week assessment, LH pulsatility was measured and compared between mice at estrus, whereas at the 1-month assessment, assessment was performed in mice at diestrus.

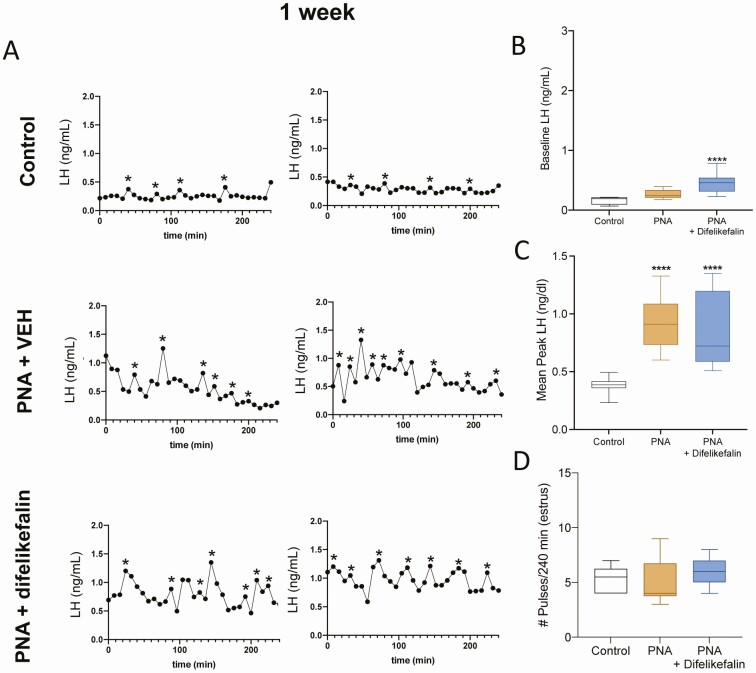

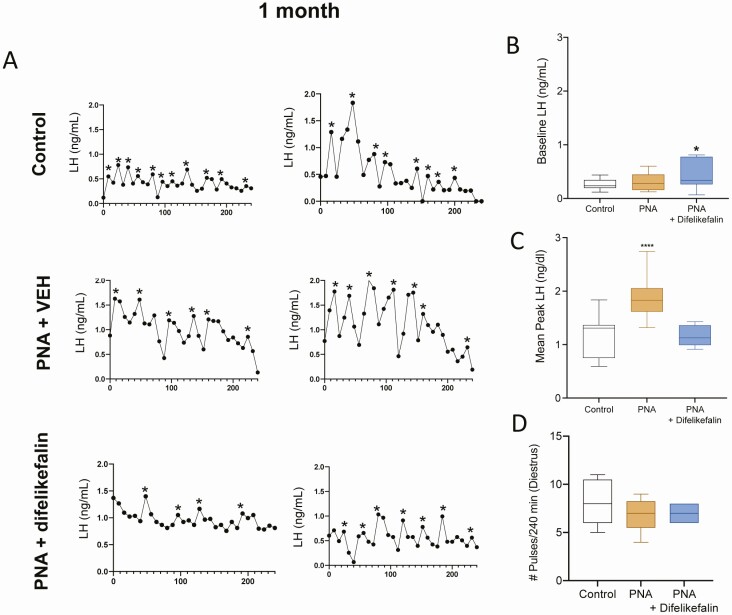

One week into the treatment of PNA mice with either difelikefalin or the vehicle alone revealed a slight but significant increase in baseline LH in treated mice (Fig. 9A-B). The peak of each LH pulse was significantly augmented in PNA mice compared with controls, with no evident effect of difelikefalin treatment (Fig. 9C). LH pulse frequency was not different between PNA and control mice (Fig. 9D). At the end of the month-long treatment with difelikefalin, the mean peak of LH pulses was reduced to control levels in the PNA + difelikefalin group but not in the PNA + vehicle group (Fig. 10A-D). Baseline LH remained modestly elevated after difelikefalin and LH pulse frequency was not affected. In summary, the PRKA difelikefalin reversed key features of the PNA phenotype—including establishing regular ovarian cyclicity and ovulation, reducing the magnitude of the LH peaks per pulse, normalizing Kiss1 expression levels in the arcuate nucleus and diminishing the elevated levels of T that characterize this model.

Figure 9.

Effect of 1 week of difelikefalin treatment on LH pulsatility in PNA mice. (A) Depicts 2 representative samples of LH pulses from each group after 1 week of difelikefalin treatment (100 nM targeted plasma concentration). (B) Baseline LH levels during 240 min (F (2, 41) = 21.86, P < 0.0001). (C) Mean peak LH release of pulses during 240 minutes, (F (2, 41) = 19.94, P < 0.0001). (D) Number of LH pulses in 240 min, F (2, 16) = 0.6283, P = 0.5461. One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s test. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. Control n = 3; PNA + vehicle n = 3; PNA + difelikefalin; n = 5. (These mice had intact ovaries, and estrus was the only cycle phase that had a sufficient number of animals to compare between treatment groups [ie, 3 or more mice at the same cycle phase].).

Figure 10.

Effect of 1 month of difelikefalin treatment on LH pulsatility in PNA mice. (A) Depicts 2 representative samples of LH pulses from each group after 1 month of difelikefalin treatment (100 nM targeted plasma concentration). (B) Baseline LH levels during 240 minutes (F (2, 37) = 3.397, P = 0.0442). Mean peak LH release of pulses during 240 minutes, (F (2, 37) = 23.76, P < 0.0001). (D) Number of LH pulses in 240 minutes, F (2, 15) = 1.077, P = 0.3656. (C) One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s test. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. Control n = 3; PNA + vehicle n = 4; PNA + difelikefalin n = 3. (These mice had intact ovaries, and diestrus was the only cycle phase that had a sufficient number of animals to compare between treatment groups [ie, 3 or more mice at the same cycle phase].).

Discussion

The pulsatile secretory activity of KNDy neurons drives the reproductive axis, awakening its activity at puberty and sustaining its function during reproductive life (73). KNDy neurons are also the primary target for the negative feedback control of GnRH and gonadotropin secretion by sex steroids (74). Thus, reproductive function in females is coordinated by the pulsatile activity of KNDy neurons, which operate within the physiological constraints of a narrow bandwidth of frequency and amplitude to orchestrate the ovarian cycle. Too little or too much activity of KNDy neurons can obstruct ovarian cyclicity and imperil other bodily functions, such as thermoregulation and metabolic homeostasis. For example, impaired KNDy neuronal function, caused by disabling mutations in one of the neurotransmitters (eg, TAC3) or blockade of Kiss1 signaling (eg, KISS1 or KISS1R), cause hypogonadism and infertility (9, 13, 14, 75–78). Conversely, hyperactive KNDy neuronal activity during the perimenopause generates VMS and may contribute to the excessive androgen production in PCOS (79). Thus, given their involvement in these disorders, KNDy neurons are now prime targets for new therapeutic interventions to ameliorate menopausal symptoms (80–82) and PCOS (43, 44). Here, we demonstrate that gonadotropin output and body temperature can be attenuated by peripherally restricted kappa agonists (PRKAs) in 2 different murine models: one that simulates menopause and the other replicating key features of PCOS, including elevated serum levels of LH and androgens, likely as a consequence of the attenuation in the activity of KNDy neurons.

Oophorectomy was performed in mice to replicate the decline in circulating levels of estradiol and the compensatory rise in the secretion of kisspeptin, GnRH and LH that ensues during the perimenopause. We demonstrated that three different kappa opioid receptor agonists—including 2 that cannot penetrate the BBB (AlaDyn and difelikefalin)—can inhibit LH secretion and might do so through either KNDy neurons, which express the kappa receptor (4), or their kappa receptor-expressing afferents. Although we cannot be sure of the identity of the target neurons for the PRKAs, we can infer that these molecules penetrate areas of the hypothalamus that lie outside of the BBB (50). This would include the median eminence, one of the brain’s circumventricular organs. Here, the endothelial cell lining of their capillaries is fenestrated and allow even relatively large molecules to diffuse into the parenchyma of the brain. It is here in the median eminence that axons of KNDy neurons make contact with fibers of GnRH neurons and represent plausible targets for PRKAs. The PRKAs blocked gonadotropin secretion without preventing the stimulatory action of kisspeptin onto GnRH neurons, indicating that PRKAs do not act directly on GnRH neurons or gonadotropes. The PRKAs not only blocked gonadotropin secretion but did so without exerting discernable effects on the higher functions of central nervous system—as evidenced by behavioral analysis (ie, tail suspension test) and in line with previous reports demonstrating the peripherally restricted effect of these PRKAs (46, 47). This observation suggests that PRKAs may have therapeutic value for treating disorders of the neuroendocrine reproductive axis, and do so without compromising cognition, mood, or motor function, which is a problem with nonperipherally restricted kappa agonists, such as pentazocine (30, 83).

In addition to their inhibitory action on gonadotropin secretion, PRKAs were also shown to reverse the effects of OVX on Tb (albeit only at the highest infusion rate tested). It is conceivable that the higher infusion rate of difelikefalin required to decrease Tb (compared with its effect on LH secretion) reflects its relative accessibility to the different sites that control thermoregulation vs of GnRH/LH secretion (27). This may reflect that the hypothalamic temperature-regulating center in the medial preoptic area, where long axons from KNDy release NKB (27), lies at a further distance from the median eminence than GnRH nerve terminals, where the short axons of KNDy neurons release kisspeptin to stimulate GnRH (84, 85). Notwithstanding, the demonstrated effects of PRKAs on Tb and LH secretion suggests that the putative effects of hyperactive KNDy neurons on temperature regulation can be attenuated by the action of PRKAs (27, 86).

OVX accelerates the rate of weight gain over time, as is the case following menopause (69–71, 87, 88). Treatment with difelikefalin at an intermediate dosage reduced the rate of weight gain by ~25%—although at the highest dosage administered, difelikefalin’s apparent effect on weight gain was equivocal. Nevertheless, the effect of this PRKA on body weight suggests that PRKAs may be useful to countermand the effects of menopause on temperature regulation and metabolism (eg, increased visceral adiposity, reduced metabolic rate) (70, 71, 88). We do not yet know whether these PRKAs would be capable of blocking or attenuating menopausal VMS; however, we do know based on a short-term clinical trial that a nonperipherally restricted kappa agonist (pentazocine) is capable of reducing the incidence of VMS in menopausal women (30). We can also infer from our present investigation that difelikefalin alters the set point for core temperature in an OVX murine model, as evidenced by its effect on Tb. This would imply that the hypothalamic temperature regulating center may be regulated by PRKAs through the inhibition of the hyperactivity of KNDy neurons that triggers VMS.

We used a murine model to simulate key aspects of PCOS (prenatal androgen exposure or PNA), which include disrupted estrous cycles and increased circulating levels of LH and T (51). The PNA-treated mice also exhibited an increase in the expression of Kiss1 mRNA in the MBH, reflecting its key role in KNDy neurons to amplify the secretion of GnRH, LH, and T in this animal model of PCOS. We demonstrated that sustained treatment of PNA-treated mice with the PRKA difelikefalin reduced their elevated serum levels of LH and T, returning them to a range exhibited by non–PNA-treated controls. The sustained treatment with difelikefalin reversed the amplified expression of Kiss1 mRNA exhibited by the PNA-treated animals. This observation bolsters the idea that PRKAs may be useful as a pharmacological clamp on the hyperactivity of KNDy neurons and thereby reduced its clinical manifestations in PCOS, such acne, hirsutism, and infertility (40, 89, 90). We also showed that a month-long treatment with difelikefalin restored normal estrous cyclicity and ovulation in the PNA-treated animals. Together, these observations testify to the therapeutic potential of PRKAs to ameliorate the hallmark features of PCOS (ie, hyperandrogenism and oligo/anovulation). We acknowledge that PCOS is a multifactorial disorder, and the murine PNA model may not recapitulate the entire spectrum of its complex etiology and phenotype (91).

Current treatments for PCOS include lifestyle management (eg, diet and exercise to reduce body weight), combined hormonal contraception, progestins, and antiandrogens, as well as other hormonal therapies used to induce ovulation (40, 90). These remedies can ameliorate some of the more troubling features PCOS, but not in everyone (40, 90); moreover, hormonal therapies may be unacceptable for some individuals (or contraindicated by the risk posed by hormone-dependent conditions) (92). Thus, finding alternative therapies to treat PCOS meets a growing and important need.

Finally, we show that the responsiveness of GnRH neurons to kisspeptin increases in the presence of peripheral PRKAs. This implies that, under normal physiological conditions, there is a tonic inhibition of GnRH secretion being imposed by an unidentified population of neurons, whose activity is blocked by PRKAs. This finding also demonstrates that PRKAs do not act on either GnRH neurons or gonadotropes, which would otherwise reduce their responsiveness to Kiss1. This corroborates earlier reports indicating that GnRH neurons (in rodents) are devoid of KOR (93, 94). This was an unexpected finding but unmasks a previously unrecognized regulatory input to GnRH neurons (and thus the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis), which emanates from a population of cells that express the KOR.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the activity of KNDy neurons can be restrained by PRKAs in 2 murine models that recapitulate phenotypic aspects of menopause and PCOS. These experiments provide a preclinical foundation from which human investigations may be launched to test safety and efficacy of PRKAs to treat disorders of the neuroendocrine reproductive axis, including VMS and PCOS. Clinical studies of these unique compounds could significantly improve the quality of life of individuals suffering from these conditions and for whom other remedies are either ineffective or unacceptable. Indeed, ongoing clinical trials with difelikefalin for other indications have revealed no adverse side effects and excellent safety profiles (48, 49), which offers promise for their use to treat VMS and PCOS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston, MA, for the use of the Rodent Histopathology Core. Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center is supported in part by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH 5 P30 CA06516.

Funding : This work was supported by grants R01HD090151, R01HD099084, and R21HD095383 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and National Institute of Health (NIH) and Ferring Innovation Grants to V.M.N. T32HL007609-31 and F32HD097963 by the NIH to E.A.M. The University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH Grant R24HD102061.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AlaDyn

(D-Ala2)-Dynorphin A (1-13)-NH2

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- E2

estradiol

- Kiss1

kisspeptin

- KNDy

Kiss1, NKB, and dynorphin

- KOR

kappa opioid receptor

- MBH

mediobasal hypothalamus

- NKB

neurokinin B

- nor-BNI

nor-binaltrophimine dihydrochloride

- OVX

ovariectomized

- PBS-T

PBS with Tween

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- PNA

prenatally androgenized

- POA

preoptic area

- PRKA

peripherally restricted kappa receptor agonist

- RT

room temperature

- RT-qPCR

real-time quantitative PCR

- SC

subcutaneously

- T

testosterone

- Tb

body temperature

- VMS

vasomotor symptom

- WT

wild-type

Additional Information

Disclosures : P.R. is a scientific cofounder of Cara Therapeutics, the company that develops difelikefalin, and holds shares of the company. C.S. is one of the inventors of difelikefalin on all the patents assigned to Cara Therapeutics.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151(8):3479-3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gottsch ML, Popa SM, Lawhorn JK, et al. Molecular properties of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152(11):4298-4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goodman RL, Lehman MN, Smith JT, et al. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe express both dynorphin A and neurokinin B. Endocrinology. 2007;148(12):5752-5760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Chavkin C, Okamura H, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. J Neurosci. 2009;29(38):11859-11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Navarro VM. New insights into the control of pulsatile GnRH release: the role of Kiss1/neurokinin B neurons. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2012;3:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, et al. Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the goat. J Neurosci. 2010;30(8):3124-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarkson J, Han SY, Piet R, et al. Definition of the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(47):E10216-E10223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gill JC, Kwong C, Clark E, Carroll RS, Shi YG, Kaiser UB. A role for the histobe demethylase LSD1 in controlling the timing of pubertal onset. Paper Presented at: the Endocrine Society Meeting; Houeston, TX; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17): 1614-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lippincott MF, León S, Chan YM, et al. Hypothalamic reproductive endocrine pulse generator activity independent of neurokinin B and dynorphin signaling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4304-4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Francou B, Bouligand J, Voican A, et al. Normosmic congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to TAC3/TACR3 mutations: characterization of neuroendocrine phenotypes and novel mutations. Plos One. 2011;6(10):e25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gianetti E, Tusset C, Noel SD, et al. TAC3/TACR3 mutations reveal preferential activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone release by neurokinin B in neonatal life followed by reversal in adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2857-2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet. 2009;41(3):354-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young J, Bouligand J, Francou B, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 defects cause hypothalamic congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(5):2287-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keen KL, Wegner FH, Bloom SR, Ghatei MA, Terasawa E. An increase in kisspeptin-54 release occurs with the pubertal increase in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-1 release in the stalk-median eminence of female rhesus monkeys in vivo. Endocrinology. 2008;149(8):4151-4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146(9):3686-3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clarkson J, d’Anglemont de Tassigny X, Moreno AS, Colledge WH, Herbison AE. Kisspeptin-GPR54 signaling is essential for preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activation and the luteinizing hormone surge. J Neurosci. 2008;28(35):8691-8697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iwata K, Kunimura Y, Matsumoto K, Ozawa H. Effect of androgen on Kiss1 expression and luteinizing hormone release in female rats. J Endocrinol. 2017;233(3):281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith JT, Dungan HM, Stoll EA, et al. Differential regulation of KiSS-1 mRNA expression by sex steroids in the brain of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146(7):2976-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith JT. Sex steroid regulation of kisspeptin circuits. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;784:275-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plant TM. The neurobiological mechanism underlying hypothalamic GnRH pulse generation: the role of kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus. F1000Res. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raz L. Estrogen and cerebrovascular regulation in menopause. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;389(1-2):22-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pachman DR, Jones JM, Loprinzi CL. Management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: current treatment options, challenges and future directions. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:123-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reed SD, Newton KM, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Ehrlich K. Night sweats, sleep disturbance, and depression associated with diminished libido in late menopausal transition and early postmenopause: baseline data from the Herbal Alternatives for Menopause Trial (HALT). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):593 e591-597; discussion 593 e597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steiner M. Psychobiologic aspects of the menopausal syndrome. In: Buchsbaum BHJ, ed. The Menopause. Clinical Perspectives in Obstetrics and Gynecology. New York, NY: Springer; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Deecher DC, Dorries K. Understanding the pathophysiology of vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats) that occur in perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause life stages. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Padilla SL, Johnson CW, Barker FD, Patterson MA, Palmiter RD. A Neural circuit underlying the generation of hot flushes. Cell Rep. 2018;24(2):271-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tataryn IV, Meldrum DR, Lu KH, Frumar AM, Judd HL. LH, FSH and skin temperaure during the menopausal hot flash. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;49(1):152-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krull AA, Larsen SA, Clifton DK, Neal-Perry G, Steiner RA. A comprehensive method to quantify adaptations by male and female mice with hot flashes induced by the neurokinin B receptor agonist senktide. Endocrinology. 2017;158(10):3259-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oakley AE, Steiner RA, Chavkin C, Clifton DK, Ferrara LK, Reed SD. κ Agonists as a novel therapy for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1328-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gambone J, Meldrum DR, Laufer L, Chang RJ, Lu JK, Judd HL. Further delineation of hypothalamic dysfunction responsible for menopausal hot flashes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59(6):1097-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abel TW, Voytko ML, Rance NE. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression in a primate model of menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(6):2111-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast C. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1159-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reed SD. Reproductive endocrinology: postmenopausal hormone therapy to prevent chronic conditions. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):196-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. Jama. 2013;310(13):1353-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22(11):1155-1172; quiz 1173-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trower M, Anderson RA, Ballantyne E, Joffe H, Kerr M, Pawsey S. Effects of NT-814, a dual neurokinin 1 and 3 receptor antagonist, on vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Menopause. 2020;27(5):498-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wolf WM, Wattick RA, Kinkade ON, Olfert MD. Geographical prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome as determined by region and race/ethnicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Witchel SF, Teede HJ, Peña AS. Curtailing PCOS. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(2):353-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;6:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vilmann LS, Thisted E, Baker JL, Holm JC. Development of obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;78(5-6):269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Herbison AE. Physiology of the GnRH neuronal network. In: Knobil JNaE, ed. Physiology of Reproduction. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006:1415-1482. [Google Scholar]

- 43. George JT, Kakkar R, Marshall J, et al. Neurokinin B receptor antagonism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4313-4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Skorupskaite K, George JT, Veldhuis JD, Millar RP, Anderson RA. Kisspeptin and neurokinin B interactions in modulating gonadotropin secretion in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(6):1421-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Binder W, Machelska H, Mousa S, et al. Analgesic and antiinflammatory effects of two novel kappa-opioid peptides. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(6):1034-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vanderah TW, Largent-Milnes T, Lai J, et al. Novel D-amino acid tetrapeptides produce potent antinociception by selectively acting at peripheral kappa-opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583(1):62-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vanderah TW, Schteingart CD, Trojnar J, Junien JL, Lai J, Riviere PJ. FE200041 (D-Phe-D-Phe-D-Nle-D-Arg-NH2): a peripheral efficacious kappa opioid agonist with unprecedented selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(1):326-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fishbane S, Jamal A, Munera C, Wen W, Menzaghi F; KALM-1 Trial Investigators . A phase 3 trial of difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):222-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fishbane S, Mathur V, Germain MJ, et al. ; Trial Investigators . Randomized controlled trial of difelikefalin for chronic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(5):600-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miyata S. New aspects in fenestrated capillary and tissue dynamics in the sensory circumventricular organs of adult brains. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moore AM, Prescott M, Campbell RE. Estradiol negative and positive feedback in a prenatal androgen-induced mouse model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):796-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coutinho EA, Prescott M, Hessler S, Marshall CJ, Herbison AE, Campbell RE. Activation of a classic hunger circuit slows luteinizing hormone pulsatility. Neuroendocrinology. 2020;110(7-8):671-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Albert-Vartanian A, Boyd MR, Hall AL, et al. Will peripherally restricted kappa-opioid receptor agonists (pKORAs) relieve pain with less opioid adverse effects and abuse potential? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(4):371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hackbarth H, Büttner D, Gärtner K. Intraspecies allometry: correlation between kidney weight and glomerular filtration rate vs. body weight. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(3):R303-R305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Steyn FJ, Wan Y, Clarkson J, Veldhuis JD, Herbison AE, Chen C. Development of a methodology for and assessment of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in juvenile and adult male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(12):4939-4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. León S, Fergani C, Talbi R, et al. Characterization of the role of NKA in the control of puberty onset and gonadotropin release in the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2019;160(10):2453-2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Esparza LA, Schafer D, Ho BS, Thackray VG, Kauffman AS. Hyperactive LH pulses and elevated kisspeptin and NKB gene expression in the arcuate nucleus of a PCOS mouse model. Endocrinology. 2020;161(4):bqaa018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Esparza LA, Terasaka T, Lawson MA, Kauffman AS. Androgen suppresses in vivo and in vitro LH pulse secretion and neural Kiss1 and Tac2 gene expression in female mice. Endocrinology. 2020;161(12):bqaa191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang JA, Hughes JK, Parra RA, Volk KM, Kauffman AS. Stress rapidly suppresses in vivo LH pulses and increases activation of RFRP-3 neurons in male mice. J Endocrinol. 2018;239(3):339-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Talbi R, Kaitlin F, Choi JH, et al. Characterization of the action of tachykinin signaling on pulsatile LH secretion in male mice. Endocrinology. 2021;162(8):bqab074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gardell LR, Spencer RH, Chalmers DT, Menzaghi F. Preclinical profile of CR845: a novel, long-acting peripheral kappa opioid receptor agonist. Paper Presented at: International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), 12th World Congress on Pain; 2008, Glasgow, Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spencer RH, Mathur V, Stauffer JW, Menzaghi F. Decrease of itch intensity by CR845, a novel kappa opioid receptor agonist. Paper Presented at: 8th World Congress on Itch; 2015, Nara, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dooley CT, Ny P, Bidlack JM, Houghten RA. Selective ligands for the mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors identified from a single mixture based tetrapeptide positional scanning combinatorial library. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(30):18848-18856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Can A, Dao DT, Terrillion CE, Piantadosi SC, Bhat S, Gould TD. The tail suspension test. J Vis Exp. 2012;59:e3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Berrocoso E, Ikeda K, Sora I, Uhl GR, Sánchez-Blázquez P, Mico JA. Active behaviours produced by antidepressants and opioids in the mouse tail suspension test. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(1):151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rivière PJ. Peripheral kappa-opioid agonists for visceral pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(8):1331-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Turner TD, Browning JL, Widmayer MA, Baskin DS. Penetration of dynorphin 1-13 across the blood-brain barrier. Neuropeptides. 1998;32(2):141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aldrich JV, McLaughlin JP. Peptide kappa opioid receptor ligands: potential for drug development. Aaps J. 2009;11(2):312-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Witte MM, Resuehr D, Chandler AR, Mehle AK, Overton JM. Female mice and rats exhibit species-specific metabolic and behavioral responses to ovariectomy. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010;166(3):520-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gibson CJ, Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Matthews KA. Body mass index following natural menopause and hysterectomy with and without bilateral oophorectomy. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(6):809-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Poehlman ET, Tchernof A. Traversing the menopause: changes in energy expenditure and body composition. Coron Artery Dis. 1998;9(12):799-803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McQuillan HJ, Han SY, Cheong I, Herbison AE. GnRH pulse generator activity across the estrous cycle of female mice. Endocrinology. 2019;160(6):1480-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pinilla L, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Millar RP, Tena-Sempere M. Kisspeptins and reproduction: physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(3):1235-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Smith JT. Sex steroid control of hypothalamic Kiss1 expression in sheep and rodents: comparative aspects. Peptides. 2009;30(1):94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):10972-10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. d’Anglemont de Tassigny X, Fagg LA, Dixon JP, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(25):10714-10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]