Abstract

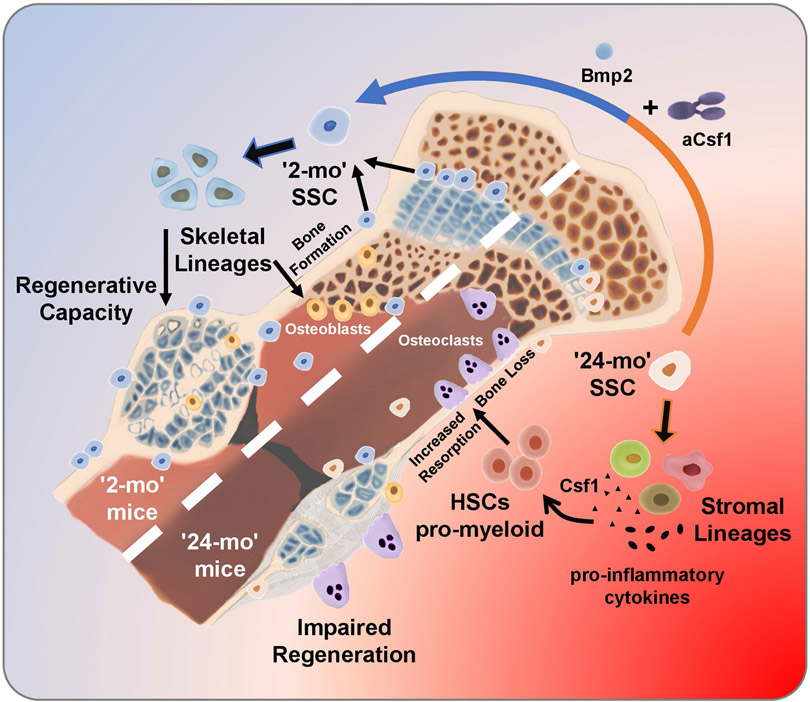

Loss of skeletal integrity during ageing and disease is associated with an imbalance in the opposing actions of osteoblasts and osteoclasts1. Here we show that intrinsic ageing of skeletal stem cells (SSCs)2 in mice alters signalling in the bone marrow niche and skews the differentiation of bone and blood lineages, leading to fragile bones that regenerate poorly. Functionally, aged SSCs have a decreased bone- and cartilage-forming potential but produce more stromal lineages that express high levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-resorptive cytokines. Single-cell RNA-sequencing studies link the functional loss to a diminished transcriptomic diversity of SSCs in aged mice, which thereby contributes to the transformation of the bone marrow niche. Exposure to a youthful circulation through heterochronic parabiosis or systemic reconstitution with young haematopoietic stem cells did not reverse the diminished osteochondrogenic activity of aged SSCs, or improve bone mass or skeletal healing parameters in aged mice. Conversely, the aged SSC lineage promoted osteoclastic activity and myeloid skewing by haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, suggesting that the ageing of SSCs is a driver of haematopoietic ageing. Deficient bone regeneration in aged mice could only be returned to youthful levels by applying a combinatorial treatment of BMP2 and a CSF1 antagonist locally to fractures, which reactivated aged SSCs and simultaneously ablated the inflammatory, pro-osteoclastic milieu. Our findings provide mechanistic insights into the complex, multifactorial mechanisms that underlie skeletal ageing and offer prospects for rejuvenating the aged skeletal system.

The progressive and gradual deterioration of an ageing body is one of the most familiar yet most resilient of medical challenges. The aetiology of most age-related conditions, including those that cause changes in skeletal tissue composition, such as osteoporosis, remains incompletely understood. Some aspects of ageing are clearly rooted in cell-intrinsic alterations, and studies have also found that the initiation and progression of the aged phenotype is dependent on cell-extrinsic factors3. Many multicellular organisms contain tissue-resident stem and progenitor cells that consistently give rise to new cells for tissue building and regeneration4, and some species even evade ageing because their somatic tissues are replenished continuously by their stem-cell systems5. Nevertheless, vertebrate animals are unable to escape the ageing process, potentially owing to the fact that regenerative stem cells and their supportive niche environment deteriorate with age6. Stem-cell ageing has been characterized in detail for haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)7. Despite their greater abundance, aged HSCs are skewed in terms of their developmental output8,9. As HSCs normally reside in the marrow niches of adult bones, ageing of HSCs and the haematopoietic system could be linked to ageing of bones. To understand the origins of bone ageing from the bone-forming stem-cell perspective, we used a defined model system of bona fide SSCs2,10,11. Our SSC-centric analysis provides notable insights into how ageing occurs at the level of local skeletal niches and how it may affect systemic aspects of multi-organ physiological ageing.

Age-related functional decline of SSCs

In agreement with previous reports12,13, we observed an age-dependent decline of skeletal architecture and remodelling–including an attenuation of the growth plate, reduced bone mass and decreases in various remodelling parameters–between 2-month-old and 24-month-old C57BL/6J male mice (Extended Data Fig. 1a-d). Using a transverse mid-diaphyseal femoral fracture model, we also found differences in the skeletal regeneration capacities of ageing mice (Extended Data Fig. 1e-i). To determine whether the age-related skeletal phenotype was due to reduced stem-cell activity, including proliferation and differentiation capacity, we next focused on the cellular origins of bone-forming cell types. In previous studies we described a purified, self-renewing mouse and human SSC that, through a multipotent bone–cartilage–stromal progenitor (BCSP), gives rise to committed lineage cells of bone, cartilage, and stroma but not fat2,11 (Extended Data Fig. 2a-c). The stromal cell populations are further delineated by a THY1+ subset, which supports short-term haematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cell populations in vitro, and a HSC- and lymphopoiesis-maintaining 6C3+ subset14. We also observed that in contrast to fetal SSCs, in the adult SSC lineage all CD51+THY1−6C3−CD105− cells were CD200-positive, potentially only allowing separation into SSCs and pre-BCSPs by the level of CD200 expression2 (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

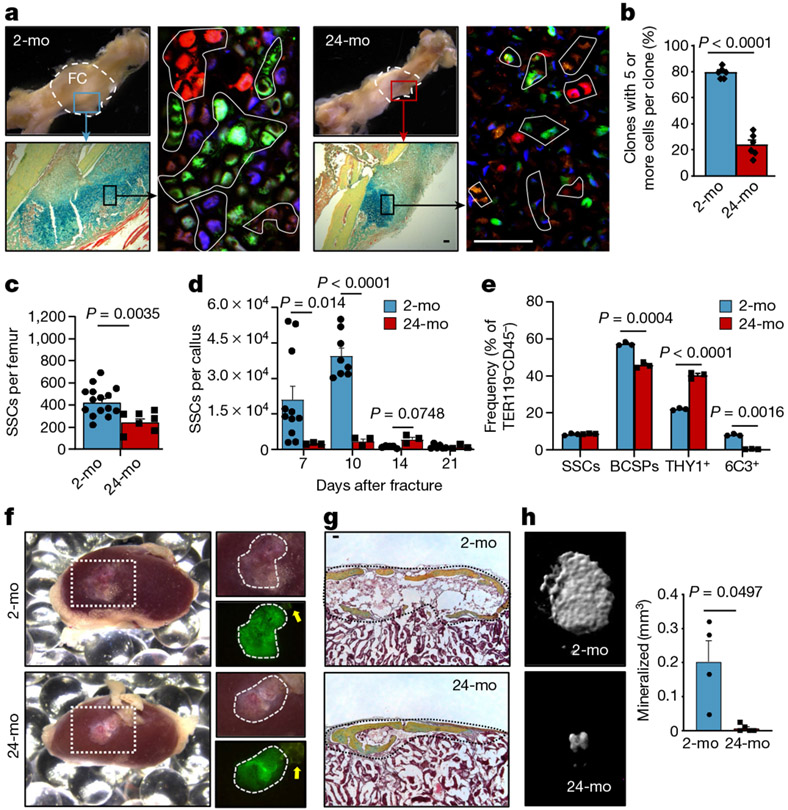

Next, we used Actin-CreERT Rainbow (‘Rainbow’) mice in a setting of skeletal regeneration known to stimulate SSC activity, to compare clonal activity in calluses from 2-month-old versus 24-month-old mice2,15 (Extended Data Fig. 2e). We found significantly increased clonal activity in healing calluses of 2-month-old mice compared to 24-month-old mice at day 10 after fracture (Fig. 1a, b). We then isolated SSCs and BCSPs from uninjured and fractured bones using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and observed corresponding age-related reductions in total cell numbers, prevalence of activated CD49f-expressing stem and progenitor cells15, and proliferative activity, with generally low but slightly increased levels of apoptosis (Fig. 1c, d, Extended Data Fig. 2f-j). Finally, flow cytometric analyses revealed that downstream SSC lineage output was shifted towards pro-myeloid THY1+ and away from 6C3+ stroma in 24-month-old mice both during in vitro culture and when induced by fracture injury in vivo (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 2k, l). Together, these data suggest that the aged skeletal phenotype corresponds to reduced SSC activity and shifted SSC lineage output in mice.

Fig. 1 ∣. Age-related bone loss coincides with altered skeletal stem-cell function.

a, Representative gross images showing fracture calluses (FC) of Actin-CreERT Rainbow mice at day 10 after fracture (top left), magnified outer callus region stained with Movat’s pentachrome (bottom left) and fluorescent clones (right) in 2-month-old (2-mo) and 24-month-old (24-mo) mice. b, Quantification of clone sizes. Six distinct callus regions (5–19 clones per section) from two mice per age group were counted. c, Flow cytometric quantification of SSCs per uninjured femur (2-mo, n = 15; 24-mo, n = 7). d, Prevalence of SSCs at different days after fracture injury in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (2-mo, day-7 n = 11, day-10 n = 7, day-14 n = 5, day-21 n = 6; 24-mo, n = 3). e, Flow cytometric analysis of the lineage output of freshly isolated SSCs from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. Cells were cultured for six days (n = 3 mice per age). f, Four-week renal capsule grafts derived from GFP-labelled SSCs of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. Representative gross images of kidneys (left) and magnified graft as bright-field images and with GFP signal shown (right). Yellow arrow indicates auto-fluorescent collagen sponge (not part of the graft). g, Sectioned grafts stained with Movat’s pentachrome. h, Representative μCT images (left) and quantification of mineralization (right) of renal grafts (2-mo, n = 4; 24-mo, n = 5). All comparisons by two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann-Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Mouse SSCs exhibit intrinsic ageing

We next isolated SSC lineage populations from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice to compare their intrinsic ability to generate skeletal tissue in vitro and in vivo. SSCs and BCSPs displayed a significantly higher colony-forming ability than downstream cell populations, independent of age, suggesting that surface-marker profiles of SSCs and BCSPs are preserved in 24-month-old mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Consistent with our observations in ‘Rainbow’ mice (Fig. 1a, b), SSCs and BCSPs isolated from 24-month-old mice generated fewer and smaller colonies compared to 2-month-old mice and led to a significantly reduced osteochondrogenic capacity in vitro. Notably, we also observed that neither young nor aged SSCs underwent adipogenic differentiation, even under highly adipogenesis-inducing conditions in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 3a-f).

To study intrinsic skeletogenic potential in vivo, we purified 3,000 GFP-labelled SSCs and BCSPs from bones of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice and transplanted them beneath the renal capsules of 2-month-old immunocompromised NSG mice. At four weeks, histological and micro-computed tomography (μCT) analyses showed that cells from 2-month-old mice formed robust bone grafts with an ectopic marrow cavity. By contrast, SSCs and BCSPs from 24-month-old mice formed smaller and less-mineralized grafts (Fig. 1f-h, Extended Data Fig. 3g). Furthermore, staining grafts with tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) to assess osteoclast activity showed that there was more bone resorption in aged grafts, implying that aged SSCs create grafts that stimulate increased osteoclast activity (Extended Data Fig. 3h). In summary, transplantation of aged SSCs into young NSG mice did not improve their skeletogenic potential, indicating that cell-autonomous changes underlie their functional decline and suggesting that aged skeletal lineages produce factors that enhance bone resorption, at least in the setting of immunocompromised mice enriched for monocytic cells.

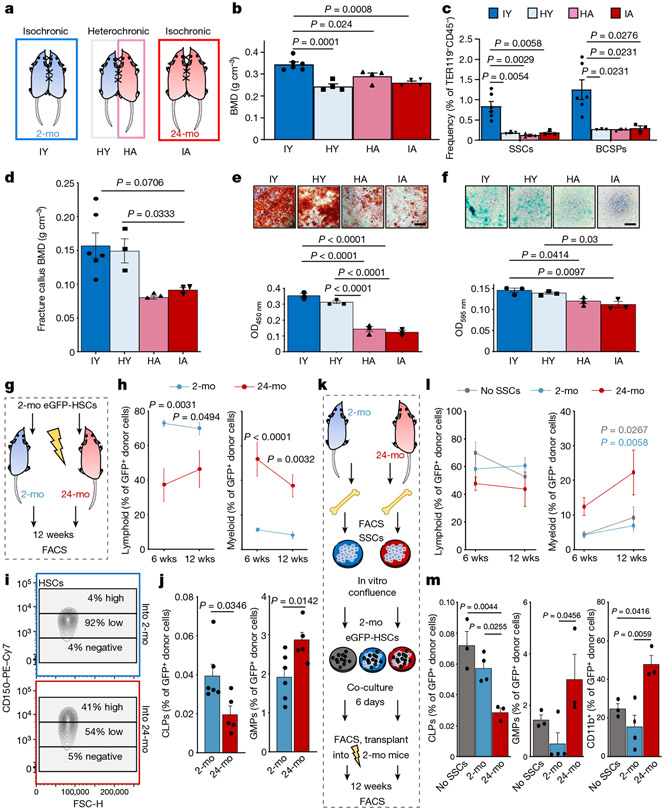

Young blood fails to rejuvenate bone

Previous studies suggest that exposure to young blood can reverse age-related changes of multiple tissues16. Because heterotopic transplantation into a young host did not rejuvenate aged SSC activity, we wondered whether exposure to a young systemic circulation by heterochronic parabiosis could revive SSCs within their endogenous microenvironment. We have previously shown that SSCs do not migrate systemically; therefore, differences in skeletogenic activity between parabionts are likely to be due to effects of circulating factors17. Testing this hypothesis, we observed that in four-week heterochronic aged parabionts, the femoral bone mineral density (BMD) and SSC frequencies were maintained at isochronic aged levels. By contrast, exposure to aged blood significantly reduced the BMD and the prevalence of SSCs in heterochronic young mice compared to isochronic young controls and resembled isochronic aged mice (Fig. 2a-c, Extended Data Fig. 4a). During skeletal regeneration we found that although callus size–an indicator of healing response15–initially increased in heterochronic aged and decreased in heterochronic young parabionts compared to their controls, no significant changes were observed at day 21 after injury. Furthermore, BMD, SSC frequency and the SSC in vitro osteochondrogenic differentiation potential of healing calluses collected from heterochronic aged mice did not improve from isochronic aged levels (Fig. 2d-f, Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). Collectively, these data show that exposure to young blood did not rejuvenate aged bones, as has been proposed for fracture healing and other tissues16,18. Our results instead indicate that factors present in the circulation of aged mice can exert a negative effect on the young SSC lineage, at least during steady state heterochronic parabiosis. Myeloid lineage overproduction is a hallmark of HSC ageing and has been attributed to an age-related overabundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines19. In the context of heterochronic parabiosis, the expression of pro-inflammatory marker genes by purified SSCs was low in both age groups. Serum levels of the pro-myogenic, osteoclastic protein RANKL and the bone resorption marker CTX1 were reduced in heterochronic aged compared to isochronic aged mice; however, osteoclastic activity at fracture sites was increased in heterochronic young compared to isochronic young mice, suggesting the possibility of an altered local microenvironment, at least in part through changes in SSC lineage composition and the involvement of factors beyond RANKL (Extended Data Fig. 4d-h). Of note, phenotypic HSCs derived from each parabiont, when transplanted into lethally irradiated young recipients showed a balanced lineage output for cells derived from isochronic young, heterochronic young and heterochronic aged mice, whereas isochronic aged HSCs gave rise to mostly myeloid lineages (Extended Data Fig. 4i). However, the presence of circulating young HSCs in heterochronic aged mice cannot be excluded20. Moreover, the age of HSCs used for haematopoietic reconstitution in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice did not affect bone mass or regeneration (Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). These findings suggest that the local microenvironment, rather than blood-borne factors, has a more immediate effect on age-related changes of skeletal integrity.

Fig. 2 ∣. The SSC lineage contributes to age-related skewing of the haematopoietic lineage.

a, Schematic representation of parabiosis experiments with isochronic 2-month-old (isochronic young; IY) and 24-month old (isochronic aged; IA) pairs as well as heterochronic pairs with one 2-month-old (heterochronic young; HY) and one 24-month-old (heterochronic aged; HA) mouse. b, BMD at four weeks of parabiosis (IY, n = 6; HY, HA, IA, n = 4 per group). c, Frequency of SSCs and BCSPs at four weeks of parabiosis. d, BMD at day 10 after fracture of parabiosed mice (IY, n = 6; HY, n = 3; HA, n = 3; IA, n = 3). e, In vitro osteogenesis of SSCs from parabiosed mice at day 10 after fracture showing representative staining (top) and quantification (bottom). OD450 nm, optical density at 450 nm. f, In vitro chondrogenesis of the same SSCs (n = 3 per group). g, Schematic for transplantation of GFP-labelled HSCs from the bone marrow of 2-month-old mice into lethally irradiated 2-month-old or 24-month-old mice. h, Peripheral blood analysis at 6 weeks (wks) and 12 weeks after haematopoietic reconstitution for lymphoid (B and T cells) and myeloid (GR1+) fractions (2-mo, n = 6; 24-mo, n = 5). i, Expression of CD150 (SLAM) in donor-derived GFP+LIN−cKIT+SCA1+FLT3−CD34− bone marrow HSCs. j, Bone marrow analysis of donor-derived (GFP+) haematopoietic cell populations at 12 weeks by flow cytometry (2-mo, n = 6; 24-mo, n = 5). CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte–monocyte progenitor. k, Schematic of SSC–HSC co-culture experiments. l, Peripheral blood analysis after haematopoietic reconstitution with co-cultured haematopoietic cells. m, Bone marrow analysis of co-cultured donor-derived (GFP+) haematopoietic cell populations at 12 weeks (no SSCs, n = 3; 2-mo, n = 4; 24-mo, n = 3). Data are mean + s.e.m. Statistical testing in b–f, m by one-way ANOVA analyses with Tukey’s post-hoc test for all comparisons. j, Two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) where appropriate. h, l, Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Aged SSCs promote myeloid bias in HSCs

On the basis of these findings, we next tested the possibility of instructive cross-talk from SSC- to HSC-lineage cells. When GFP-labelled HSCs from 2-month-old mice were transplanted into either 2-month-old or 24-month-old lethally irradiated mice, the composition of donor-derived peripheral blood cells at 12-weeks showed a myeloid bias in 24-month-old hosts (Fig. 2g, h, Extended Data Fig. 5d). Bone marrow analyses revealed that donor-derived LIN−SCA1+cKIT+FLT3−CD34− HSCs in 24-month-old mice contained larger proportions of myeloid-biased CD150/SLAMhigh expressing cells compared to 2-month-old mice9. In line with this observation, at 12 weeks, the frequencies of engrafted bone marrow cells in 24-month-old mice significantly shifted from generating common lymphoid progenitors towards producing myeloid lineages (Fig. 2i,j, Extended Data Fig. 5e-g). In support of these results, we found that if bi-cortical fractures were induced in the same mice, significantly more donor-derived TRAP-positive osteoclastic areas were observed at day-10 callus sites of 24-month-old compared to 2-month-old mice (Extended Data Fig. 5h, i). We next tested the ability of SSC-derived stroma from 2-month-old versus 24-month-old mice to skew co-cultured young HSCs directly. Whereas HSCs from 2-month-old mice cultured with SSC-derived stroma from 2-month old mice presented a balanced lineage output, transplantation of HSCs co-cultured with SSC-derived stroma from 24-month-old mice into lethally irradiated 2-month-old recipient mice led to an increased myeloid output in peripheral blood, as well as higher numbers of common myeloid progenitor, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor and CD11b+ cells at the expense of populations of common lymphoid progenitors in the host bone marrow (Fig. 2k-m, Extended Data Fig. 5j-l). Together, these findings suggest that aged SSC-derived stroma directly contributes to the age-related myeloid skewing of the haematopoietic system.

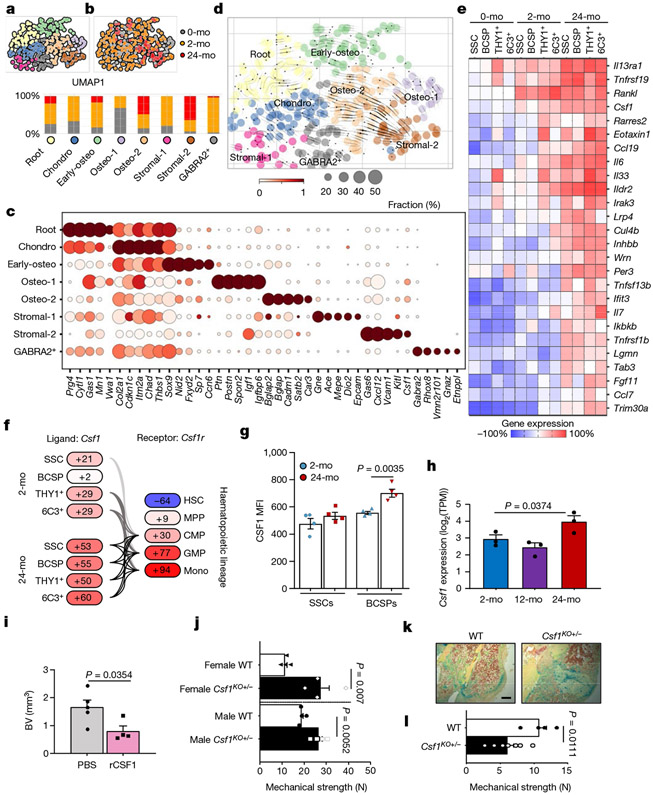

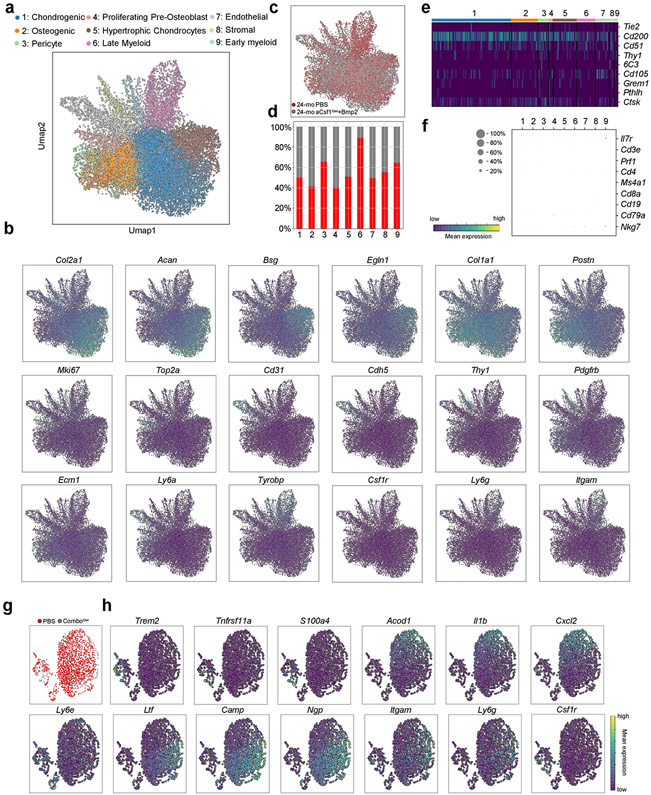

Age-related loss of SSC diversity

To determine whether SSC ageing is associated with characteristic transcriptional changes, we FACS-purified phenotypic SSCs from the long bones of postnatal day 3 (‘0-month-old’), 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice for full-length Smart-seq2 single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Using Leiden clustering on quality filtered cells, we identified eight subpopulations with subtle differences in their transcriptomic profiles, indicative of potential priming stages of distinct SSC subsets (Fig. 3a-c, Extended Data Fig. 6a-j, Supplementary Data 1). On the basis of enriched genes, these clusters were annotated as a chondrogenic population (‘Chondro’); an osteogenic population, separated into ‘Early-osteo’, ‘Osteo-1’ and ‘Osteo-2’ cell types; and a stromal population, with extracellular matrix genes-expressing ‘Stromal-1’ and pro-haematopoietic ‘Stromal-2’ cells, as well as a ‘GABRA2-positive’ population that warrants further investigation in the future. By performing CytoTrace analysis to detect variations in differentiation state and RNA velocity to infer trajectories from related populations, it was possible to annotate the remaining cluster as the potential SSC ‘Root’ (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 6k, Supplementary Table 1). Accordingly, SSCs from all age groups were represented in the Root cluster. Although SSCs from young (0-month-old and 2-month-old) mice were part of each cluster, they were specific to Chondro, Osteo-1 and Stromal-1, implying that there are multiple distinct fate-specification programs at young ages. By contrast, SSCs from 24-month-old mice were most abundant in the pro-haematopoietic Stromal-2 cluster; this suggests that these cells have a limited and stromal-shifted lineage potential during ageing, corresponding to observations of their reduced osteochondrogenic differentiation and in vivo ossicle formation capacity. In sum, these results couple the functional decline of aged SSCs to a loss in transcriptomic diversity, which thereby restricts developmental potential.

Fig. 3 ∣. A pro-inflammatory aged skeletal lineage drives enhanced osteoclastic activity through CSF1.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot showing Leiden clusters from combined Smart-seq2 scRNA-seq of single cells from postnatal day 3 (0-month-old), 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. b, Clustering of the same UMAP plot by age (top), showing the distribution within Leiden clusters (bottom) of sequenced single cells by age. c, Dot plot showing marker genes for each Leiden cluster. d, RNA velocity trajectory inference analysis with cells labelled by Leiden cluster. e, Heat map of bulk microarray data for the expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-myeloid or pro-osteoclastic genes of purified skeletal lineage populations. Wisp3 is also known as Ccn6. Each cell population reflects the expression of a pooled sample of three to five mice. f, Ligand (Csf1) and receptor (Csf1r) microarray bulk gene expression (in percentage) in the 2-month-old and 24-month-old SSC lineage and in the haematopoietic lineage, respectively. MPP, multipotent progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; mono, monocyte. g, Levels of CSF1 protein measured by Luminex assay in the supernatant of SSC and BCSP cultures from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 4 per group). MFI, median fluorescence intensity. h, Csf1 expression in bulk RNA-sequencing data of purified SSCs of day-10 fracture calluses from 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 3 per age). TPM, transcripts per million. One-sided Student’s t-test to compare ageing groups to the 2-month-old group. i, μCT analysis of bone volume (BV) of day-10 fracture calluses that were locally treated with PBS or 5 μg of recombinant CSF1 (rCSF1) (PBS, n = 5; rCSF1, n = 4). j, Mechanical strength of uninjured femur bones from 15-month-old haplo-insufficient Csf1-knockout (Csf1KO) mice versus wild-type (WT) mice (n = 4 per group). k, l, Movat’s pentachrome staining of day-21 fracture callus tissue (k) and mechanical strength of the same calluses (l) from 15-month-old Csf1KO and wild-type mice (wild type, n = 4; Csf1KO, n = 7). Two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate (g, i, j, l). Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bar, 150 μm.

When we further probed specific differences in gene expression as a consequence of ageing, we found that SSCs from 24-month-old mice were enriched for genes that have been associated with reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of biological processes also revealed an enrichment of genes associated with increased monocyte and macrophage chemotaxis, supporting the pro-myeloid axis that was observed in functional experiments (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 6l, m, Supplementary Table 2). Together, these findings provide a molecular basis by which aged SSCs lose their skeletogenic potential while also increasing their interaction with the haematopoietic compartment, which ultimately could promote enhanced osteoclastogenesis.

Aged SSCs promote osteoclastogenesis

Owing to the relative rarity of stem cells and the possibility that stem-cell-based defects are inherited by their progenies, we reasoned that we would find similar alterations in gene expression in downstream SSC lineages. Thus, we extended our transcriptomic analyses to include detailed genome-wide microarray data of SSCs, BCSPs, THY1+ and 6C3+ cells from 0-month-old, 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. The results showed a pronounced age-related shift in all lineage populations to a profile supportive of inflammatory osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3e). Notably, Rankl (also known as Tnfsf11) and Csf1–factors that are necessary and sufficient for osteoclast maturation21–showed specific expression patterns. Whereas Rankl was expressed at relative high levels at 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice, Csf1 showed a pronounced increase in expression in all four subpopulations in 24-month-old mice. SSC-lineage-specific expression of Csf1 matched with strong expression of Csf1r on granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and monocytes. Accordingly, bone marrow mononuclear cells from 24-month-old mice exhibited enhanced osteoclast activity in vitro when supplemented with RANKL and CFS1, compared to bone marrow cells from 2-month-old mice, indicating higher frequencies of osteoclast progenitors (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 7a-g).

We then quantified the secretion of CSF1 by FACS-purified SSCs and BCSPs in vitro and found that cells from 24-month-old mice secreted increased levels of CSF1, as determined by Luminex assay, as well as more pro-inflammatory CCL11 (eotaxin-1) and less pro-osteochondrogenic TGFβ compared to cells from 2-month-old mice (Fig. 3g, Extended Data Fig. 7h). We also found a general increase in inflammatory factors (for example, IL-1β, IL-10 and TNF) in the serum of aged mice, whereas systemic levels of CSF1, CCL11 and TGFβ were not significantly different between 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice, indicating that the concentrations of these cytokines are more tightly regulated in the local niche environment (Extended Data Fig. 7i,j). Bulk RNA sequencing of gene expression profiles of SSCs from fracture calluses of 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice further supported our transcriptomic analyses of homeostatic SSCs, including the age-dependent upregulation of pro-haematopoietic and pro-myeloid factors such as Csf1 and the downregulation of pro-skeletogenic genes (Fig. 3h, Extended Data Fig. 7k).

We next tested whether upregulated CSF1 affected bone maintenance and regeneration. We applied hydrogels containing recombinant CSF1 to femoral fractures of 2-month-old mice and found impaired healing without any alteration in the frequency of SSCs, as measured by μCT and flow cytometry17 (Fig. 3i, Extended Data Fig. 8a-c). Although not necessarily age-related, we also found that 15-month-old haplo-insufficient Csf1 mice had superior bone parameters, independent of sex. Unexpectedly, however, femurs from transgenic mice at day 21 after fracture showed decreased mechanical strength compared to wild-type controls, despite having increased BMD and similar callus volume (Fig. 3j, k, Extended Data Fig. 8d-g). These observations resemble a state of osteopetrosis, leading to higher skeletal fragility, and altogether suggest that tightly controlled levels of CSF1 by the SSC lineage are necessary to support healthy bone remodelling and regeneration.

Restoring fracture healing to youthful levels

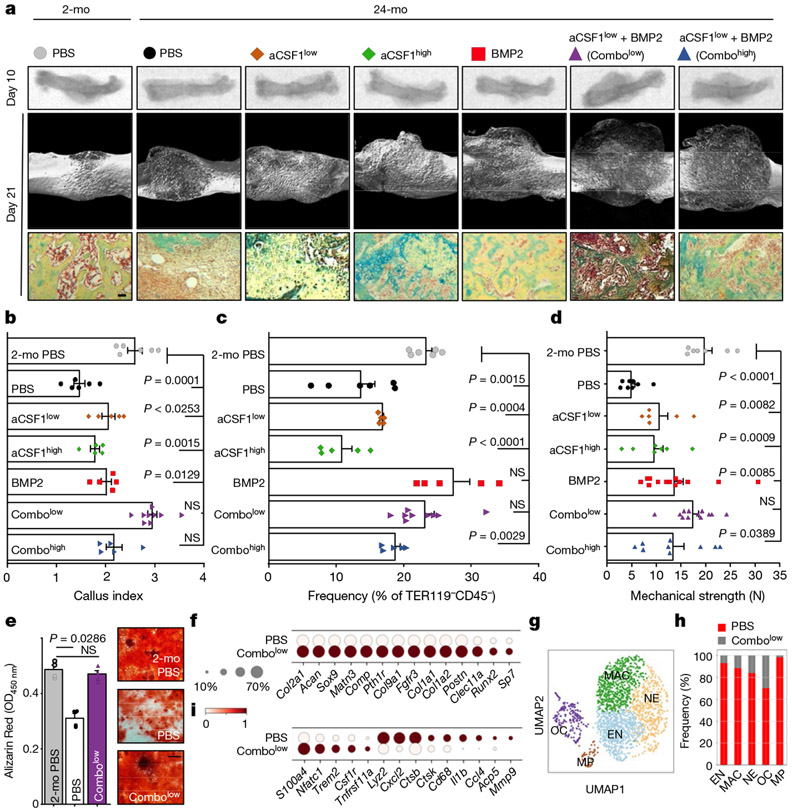

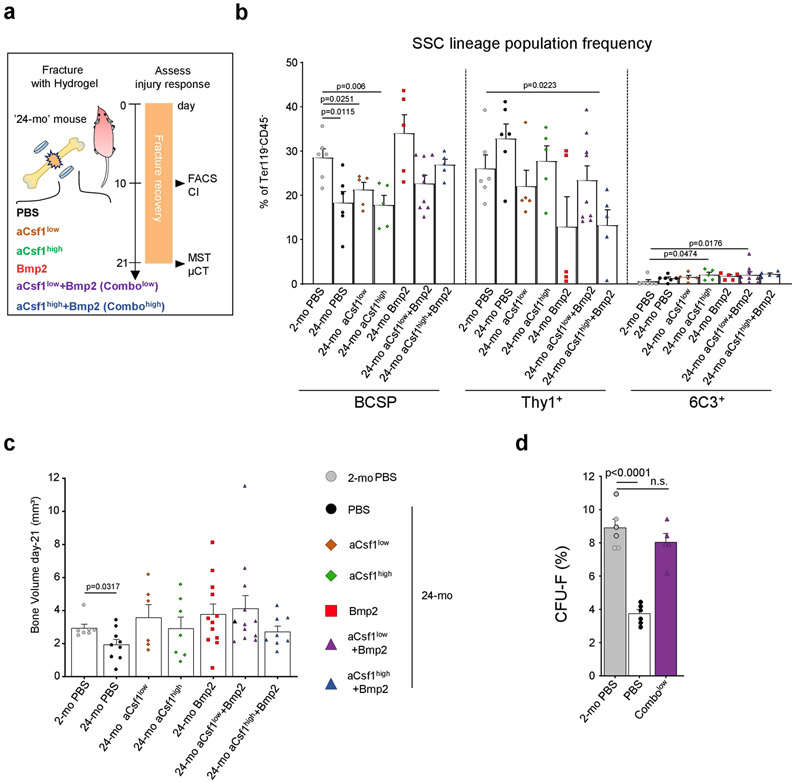

Our findings indicate that aged SSCs lose osteochondrogenic activity while paradoxically enhancing bone resorption through the generation of an inflammatory, pro-osteoclastic niche. To test whether bone regeneration could be restored in aged mice by targeting both processes, we placed hydrogels containing the potent osteo-inductive agent BMP2 (5 μg); a CSF1 antagonist (‘aCSF1’) at a dose of either 2 μg (‘low’) or 5 μg (‘high’); a combination of both factors; or PBS locally to transverse femoral fractures of 24-month-old mice2,22 (Extended Data Fig. 9a). The callus index at day 10 after fracture only remained similar to 2-month-old controls when 24-month-old mice were given combinatorial treatments (Fig. 4a, b). Flow cytometric analysis of these calluses showed that BMP2 was sufficient to increase SSC frequencies to youthful levels despite having no effect on callus size. Nonetheless, at day 21 after fracture, all BMP2 and aCSF1 treatment groups of 24-month-old mice formed comparable amounts of mineralized tissue to that formed by 2-month-old control mice (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). Consistent with our observations that genetic ablation of Csf1 is detrimental to fracture repair, we found that the combination of BMP2 together with a low dose–but not a high dose–of aCSF1 uniquely restored the mechanical strength of healing femurs of 24-month-old mice to that of young bones (Fig. 4d). Notably, SSCs from fracture calluses of 24-month-old mice treated with a combination of low aCSF1 and BMP2 showed a youthful colony-forming and osteogenic capacity, thus linking rejuvenated stem-cell characteristics to improved healing outcomes (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 9d). On the molecular level, 10X scRNA-seq of day-10 fracture calluses from 24-month-old combinatorial rescue mice (that is, mice that were treated with BMP2 and a low dose of aCSF1) showed much higher expression of osteochondrogenic genes in non-haematopoietic cell types compared to the 24-month-old mice that were treated with PBS (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 10a-c). Compositionally, and in support of the treatment, fracture calluses from 24-month-old combinatorial rescue mice had higher fractions of bone-forming cells, including phenotypic SSCs (clusters 2 and 4)2,23,24, whereas 24-month-old control mice that were treated with PBS exhibited a higher abundance of immune cells, almost exclusively of myeloid origin (Fig. 4g, h, Extended Data Fig. 10d-h). The combinatorial rescue treatment reduced the overall prevalence of myeloid cells and led to higher expression of pre-osteoclastic genes compared to late osteoclast markers in 24-month-old control mice that were treated with PBS, supporting the enhanced inhibition of osteoclast maturation by the presence of aCSF1 (Fig. 4i). Altogether, these data show that the local and temporal application of BMP2 to stimulate the activation of SSCs, combined with low levels of aCSF1 to constrain bone resorption, restores youthful bone regeneration in aged bones (Extended Data Fig. 11).

Fig. 4 ∣. Combinatorial targeting of the aged skeletal niche restores youthful fracture regeneration.

a, Radiographic images of fractured femurs at day 10 (top) and μCT reconstructions of calluses at day 21 after fracture (middle). Bottom, Movat’s pentachrome staining of sections of calluses. b, Callus index at day 10 after fracture. c, Frequency of SSCs at day 10 (2-mo PBS, n = 6; PBS n = 6; CSF1low, n = 5; CSF1hlgh, n = 5; BMP2, n = 5; Combolow, n = 9; Combohlgh, n = 5). d, Mechanical strength test of fractured bones at day 21 (2-mo PBS, n = 7; PBS, n = 8; CSF1low, n = 6; CSF1high, n = 7; BMP2, n = 13; Combolow, n = 12; Combohigh, n = 9). e, In vitro osteogenesis of SSCs at day 10 (n = 4 per group). Data are mean + s.e.m. Two-sided Student’s t-test between the 2-month PBS group and each 24-month group, adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) where appropriate (NS, not significant). f, Dot plot showing the expression of osteochondrogenic genes from 10X scRNA-seq of 24-month PBS and Combolow fracture calluses; subset for non-haematopoietic cells. g, Leiden clustering of the 10X scRNA-seq dataset for cell fractions enriched for haematopoietic gene expression (myeloid progenitor (MP), osteoclast (OC), early neutrophil (EN), neutrophil (NE), macrophage (MAC)). h, Percentage of treatment-group cell fraction per Leiden cluster. i, Dot plot showing early and late osteoclastic gene expression in the OC cluster. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Discussion

Our findings reveal the multifaceted nature of skeletal ageing, in which multiple types of stem-cell defect contribute to the overall functional decline of skeletal tissue and regeneration. We demonstrate that bone ageing is rooted in cell-intrinsic alterations at the SSC level that ultimately skew skeletal and haematopoietic lineage output, diminish bone integrity and limit healing capacity. Genetic data indicate that SSCs lose transcriptomic diversity with age, suggesting that clonal selection of a functionally distinct subpopulation of SSCs could contribute to the aged skeletal phenotype25. Similarly, epigenetic priming or drift could be drivers of intrinsic SSC ageing26. Although our parabiosis studies could not entirely resolve the relative contributions of anabolic versus catabolic mechanisms that lead to skeletal dysfunction by aged SSCs, future studies will have to assess the degree of bone-forming defects on the level of downstream cell populations that might inherit or even accumulate age-related impairments. Our studies also provide a framework for the development of approaches to reverse age-related skeletal decline therapeutically, which could have clinical implications beyond the skeleton. Simultaneous local targeting of SSC-autonomous and -non-autonomous activities can restore ageing-impaired skeletal regeneration. However, it seems likely that other cell types apart from SSCs-for example, osteoblasts and immune cells-are positively affected by the rescue treatment. Considering the divergence of regulatory mechanisms between SSCs in mice and humans, two vertebrates with distinct growth and ageing rates, we anticipate that a comprehensive comparative study between equivalent populations of the two SSC lineages could elucidate the full spectrum of deterministic mechanisms, including negative pleiotropy, that underlie skeletal ageing12. Finally, our results provide evidence that the development of systemic ‘inflamm-aging’ might originate from age-related changes in the activity of SSCs.

Methods

Data reporting

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Mice

All mouse experiments complied with all relevant ethical regulations and were conducted under approved protocols by Stanford’s Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Mice were maintained at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility in accordance with Stanford University guidelines. Mice were given food and water ad libitum and housed in temperature-, moisture- and light-controlled (12-h light-dark cycle) micro-insulators. Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were conducted using postnatal day 3 (‘O-month-old’), 2-month-old and 24-month-old male B6 mice (C57BL/Ka-Thy1.1-CD45.1; JAX: 000406). Rainbow immunofluorescence experiments were conducted using young and old male Actin-CreERT2;R26VT2/GK3 mice bred and maintained in our laboratory. To study clonal activity during fracture healing, Rainbow mice were given intraperitoneal injections of 200 mg kg−1 of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil three and five days after fracture. For parabiosis experiments, young and old male GFP mice (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)1Osb/J; JAX: 003291) were used. Cells for renal transplants into male NSG mice (NOD scid gamma; JAX: 005557) were also derived from young and old GFP mice. Csf1KO+/− mice were generated by initial breeding of B6 mice (JAX: 000406) with op/+ mice (B6;C3Fe a/a-Csf1op/J) obtained from Jackson Laboratories (JAX: 000231), followed by op/+ B6 mice with op/+ mice interbreeding. Female and male Csf1KO+/− mice were used in experiments as indicated.

Bi-cortical femoral fracture

Mice were anaesthetized using aerosolized isoflurane and analgesia was administered before incision. The femur was exposed after muscle distraction and lateral dislocation of the patella. A 25-gauge regular bevel needle (BD BioSciences) was inserted between the femoral condyles to provide relative intramedullary fixation, and a transverse fracture was created in the mid-diaphysis using micro-scissors. Then, the patella was relocated, and 6-0 nylon suture (Ethicon) was used to re-approximate the muscles15,27.

Hydrogel fabrication and placement

Eight arm polyethylene glycol (PEG) monomers with end groups of norbornene (molecular weight (MW) 10 kDa) or mercaptoacetic ester (MW 10 kDa) were dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 20% w/v. Then, photo-initiator lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate was added to each solution to make a concentration of 0.05% w/v. The two polymer solutions were mixed at a 1:1 volume ratio to obtain a hydrogel precursor solution. Recombinant mouse growth factor BMP2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 355-BM) and anti-CSF1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MAB4161SP) were added to the precursor solution at desired concentrations28. Solutions were exposed to ultraviolet light (365 nm, 4 mW cm−2) for 5 min in the mould with a volume of 4 μl each to obtain factor-loaded hydrogels in 50% of the concentrations noted in figure legends.

X-ray radiography

Femurs were dissected and cleaned of soft tissue. Femurs (with pin removed) were radiographed within 2 h of dissection using a Lago-X scanner (Spectral Instruments Imaging). Radiograph images were analysed using ImageJ v.1.48 to determine the callus index. The callus index is a ratio of the maximal mid-diaphyseal callus diameter to the maximal diameter of adjacent uninjured diaphysis.

Mechanical strength testing

Mechanical strength testing was conducted using a delaminator maintained by the R.H. Dauskardt laboratory (Stanford). Before testing, uninjured and post-fracture day-21 femurs were dissected and cleaned of soft tissues. Intramedullary fixation was removed. Femur samples were stored in PBS on ice until testing within 6 h of dissection. The maximum load (N) sustained before fracture was recorded.

Micro-computed tomography

Soft tissue and pin-free femurs were scanned within 2 h of dissection using a Bruker Skyscan 1276 (Bruker Preclinical Imaging) with a source voltage of 85 kV, a source current of 200 μA, a filter setting of AI 1 mm, and pixel size of 12 μm at 2016 × 1344. Phantom targets provided by the manufacturer were used to calibrate instrument measurements. Reconstructed samples were analysed using CT Analyser (CTan) v.1.17.7.2 and CTvox v.3.3.0 software (Bruker). Trabecular bone parameters of uninjured femur bones were assessed by analysing a region of 200 sections that was defined 50 sections distal of the end of the growth plate. Fracture calluses were analysed by selecting 150 sections in both directions of the fracture gap, yielding a total area of 300 sections. The exact region spanning fracture callus outside the boundaries of cortical bone was then manually selected using CTAn for analyses.

Dynamic histomorphometric analysis

For calcein labelling of non-decalcified bone specimens, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2.5 mg ml−1 of calcein (Sigma-Aldrich, C-0875) in a 2% sodium bicarbonate solution. Mice were labelled 7 days apart and euthanized 3 days after the second injection for sectioning and analysis.

Histology

Dissected, soft-tissue-free specimens were fixed in 2% PFA at 4 °C overnight. Samples were decalcified in 400 mM EDTA (EDTA) in PBS (pH 7.2) at 4 °C for 2 weeks with a change of EDTA twice every week. The specimens were then dehydrated in 30% sucrose at 4 °C overnight. Specimens were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) and sectioned at 5 mm. Representative sections were stained with freshly prepared haematoxylin and eosin, Movat’s pentachrome or TRAP.

Flow cytometry of skeletal progenitors

Ageing affects the composition and lineage fates of bone marrow niche cell types29-35. Multiple overlapping SSC populations have been reported23,24,36-38. Here, SSC lineage populations were isolated using cell-surface-marker profiles as previously described2,39. In brief, femurs were dissected, cleaned of soft tissue and crushed using mortar and pestle. Then, the tissue was digested in M199 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11150067) with 2.2 mg ml−1 collagenase II buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, C6885) at 37 °C for 60 min. Dissociated cells were strained through a 100-μm nylon filter, washed in staining medium (10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS) and pelleted at 200g at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in staining medium and haematopoietic lineage cells were depleted via ACK lysis for 5 min. The cells were washed again in staining medium and pelleted at 200g at 4 °C. Then, the cells were prepared for flow cytometry with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) against CD45 (15-0451; 1:200), TER119 (15-5921; 1:200), CD51 (12-0512; 1:50), TIE2 (14-5987; 1:20), THY1.1 (47-0900; 1:100), THY1.2 (47-0902; 1:100), 6C3 (17-5891; 1:100), CD49f (11-0495; 1:100), CD105 (13-1051; 1:50) and streptavidin–PE–Cy7 conjugate (25-4317-82; 1:100) as well as CD200 (MA5-17980; 1:100) and Rat IgG2a, κ isotype control (11-4321-80; 1:100). Flow cytometry was conducted on a FACS Aria II Instrument (BD BioSciences) using a 70-μm nozzle in the Shared FACS Facility in the Lokey Stem Cell Institute (Stanford). The skeletal stem-cell lineage gating strategy was determined using fluorescence-minus-one controls. Propidium iodide staining was used to determine cell viability. All cell populations were sorted for purity.

Proliferation and apoptosis assays

EdU proliferation assays were conducted according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. In brief, FACS-purified mouse SSCs and BCSPs were fixed and permeabilized separately using a fix–perm kit (BD Biosciences, 554714) and processed via ClickIT Edu reaction (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10337). Then, the cells were reanalysed by flow cytometry for their proliferative potential. For annexin V apoptosis assays, cells were processed using the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, V13241) on freshly isolated mouse SSCs and BCSPs.

Cell culture

Wells were cultured in MEM-α with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 15140-122). For in vitro colony-forming assays, 500 FACS-purified mouse SSCs were plated in 6-well tissue culture well plates for 14 days. Then, colonies were stained using Crystal Violet (Sigma-Aldrich, C0775). Colony size was determined using ImageJ software of photo-scanned well plates. For in vitro skeletogenic differentiation, 12,000 FACS-purified mouse SSCs or BCSPs were cultured in separate wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate. Cells were washed in PBS, trypsinized and transferred to osteogenic differentiation medium (10% FBS, 100 μg ml−1 ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate in DMEM for 14 days), chondrogenic medium (micromass cultures generated by a 5-μl droplet of cell suspension with approximately 1.5 × 107 cells per ml were pipetted in the centre of a 48-well plate and cultured for 2 h in the incubator before adding warm chondrogenic medium consisting of DMEM (high glucose) with 10% FBS, 100 nM dexamethasone, 1 μM L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate and 10 ng ml−1 TGF-β1 and maintained for 21 days), or adipogenic medium (50 μM indomethacin, 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 μM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 nM 3,3’,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (T3) were added for 48 h, followed by further differentiation in growth medium without growth factors and the addition of T3 and insulin only until day 10). At the end of differentiation cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% PFA and stained with Alizarin Red S (Sigma-Aldrich, A5533-25G) solution (osteogenesis), Alcian Blue (Sigma-Aldrich, A3157) solution (chondrogenesis), or Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich; O0625) solution (adipogenesis). For in vitro cytokine secretion assays, 25,000 FACS-purified SSCs or BCSPs were cultured in separate wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate in the above conditions. Forty-eight hours after seeding cells, well plates were washed three times with PBS and culture medium conditions were changed to serum-free MEM-α with 1% penicillin-streptomycin. After 24 h, the conditioned medium was collected and spun at 200g at 4°C. The aspirate was flash-frozen and immediately submitted for Luminex analyses at the Human Immune Monitoring Center (Stanford). To test functionally whether aged bones are more responsive to the two pro-osteoclastic factors RANKL and CSF1, we supplemented whole bone marrow from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice with these factors in vitro. In brief, bone marrow cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 200,000 cells per well with MEM-α without phenol red, 1% GlutaMAX supplement (Gibco, 35050061), 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin 10,000 U ml−1, 10−7 μM prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Sigma-Aldrich, P5640), 10 ng ml−1 CSF1 recombinant human protein (Peprotech, 315-02) for 3 days. On day 3, the medium was changed daily to also include 10 ng ml−1 recombinant mouse RANKL (Peprotech, 315-11). Osteoclast culture continued for 7–10 days until large, multinucleated osteoclasts appeared. Plates were stained for osteoclasts using the TRAP kit (Sigma-Aldrich, 387A).

Renal capsule transplantation

Renal capsule transplantations were conducted as previously described2,40. In brief, in the anaesthetized mouse a 5-mm dorsal incision was made and the kidney was exposed manually. Then, a 2-mm incision was created in the renal capsule using a needle bevel, and 3,000 FACS-purified mouse SSCs or BCSPs resuspended in 2 μl of Matrigel were transplanted beneath the capsule. The kidney was re-approximated manually and incisions were closed using sutures and staples. Grafts were collected after 28 days.

Parabiosis

Mice were paired 4 weeks before experimental intervention in the following chimeric pairs: isochronic young (2 × 2-month-old), heterochronic (2-month-old × 24-month-old), and isochronic aged (2 × 24-month-old). Mice were anaesthetized and an incision from the distal foreleg to the distal hindleg was made on the right side of one parabiont and on the left side of the second parabiont. The forelegs and hindlegs and the dorsal–dorsal and ventral–ventral skin folds were sutured together using 5-0 nylon suture (Ethicon). Flow cytometry verified blood chimerism after two weeks via peripheral blood sample. Peripheral blood chimerism of 1:1 was used to determine full fusion of the circulatory systems. Fractures in parabionts were induced on opposite sides of the pairing flanks as described above.

Haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation from parabionts

Parabiotic pairs of 4 weeks were euthanized and the bone marrow was collected. Long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs; LIN−cKIT+SCA1+CD150+CD34−) were isolated by FACS according to their specific surface marker profiles: [lineage-negative (CD3 (15-0031; 1:20), CD4 (15-0041; 1:20), CD8 (15-0081; 1:20), B220 (15-0452; 1:20), GR-1 (15-9668; 1:20), MAC1 (15-0112; 1:20), TER119 (15-5921; 1:20)], positive for cKIT (A15423; 1:50), SCA1 (Biolegend, 108120; 1:50), Slam/CD150 (12-1502; 1:50), and negative for CD34 (50-0341; 1:50). For HSC transplantation, 100 double-sorted GFP+ LT-HSCs were combined with 300,000 unsorted host bone marrow cells as helper marrow and injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated (800 rad) young mice. Peripheral blood cells were then stained with antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for TER119 (15-5921 CD34 (50-0341; 1:200), B220 (47-0452), CD3 (17-0031 CD34 (50-0341; 1:100), MAC1 (25-0112) and CD34 (50-0341; 1:100). Flow cytometric analysis was conducted using FlowJo v.10 software.

Haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation into young and aged mice

For HSC transplantation experiments into 2-month-old or 24-month-old recipients, 100 embryonic day 15 (E15) fetal liver HSCs or 24-month-old bone marrow HSCs were injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated (800 rad) B6 mice together with 300,000 unsorted host bone marrow cells as helper marrow. Eight weeks after injection, bone mineral density was measured by μCT. In addition, at this time point bi-cortical fractures were generated in these mice. For HSC transplantation experiments into 2-month-old or 24-month-old recipients 1,000 HSCs from 2-month old GFP-mouse bone marrow were injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated (950 rad) B6 mice together with 500,000 SCA1-depleted, unlabelled bone marrow cells as helper marrow. Peripheral blood analysis was conducted at 6 and 12 weeks after injection. At 12 weeks bone marrow was analysed for donor-derived (GFP+) haematopoietic lineage tree cell populations as described previously41. For flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow, cells were stained with the following antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific unless otherwise stated): lineage [(CD3 (15-0031; 1:20), CD4 (15-0041; 1:20), CD8 (15-0081; 1:20), B220 (15-0452; 1:20), GR-1 (15-9668; 1:20), TER119 (15-5921; 1:20)], MAC1 (56-0112-82; 1:50), cKIT (A15423; 1:50), SCA1 (Biolegend; 108120; 1:50), FLK2/FLT3 (46-1351-82; 1:50), CD16/32 (12-0161-82; 1:50), CD127 (Biolegend; 135035; 1:50) and CD34 (50-0341;1:50).

Co-culture of SSCs and HSCs

For co-culture experiments SSCs were freshly isolated from 2-month-old or 24-month-old mice as described above and seeded at 3,000 cells per well into 96-well plates. Cells were maintained in growth medium for three to five days until they reached confluency. SSC growth medium was removed and replaced with HSC supporting medium as described previously42, supplemented with recombinant fibroblast growth factor. In brief, the medium contained 1× Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mix liquid medium (Gibco, 11765-054), 1× penicillin–streptomycin–glutamine (Gibco, 10378-016), 1× insulin–transferrin–selenium–ethanolamine (ITSX; Gibco, 51500-056), 1% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA; 87–90%-hydrolyzed; Sigma, P8136), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, 15630-080), 10 ng ml−1 recombinant animal-free mouse stem cell factor (SCF; Peprotech, AF-250-03), 5 ng ml−1 recombinant animal-free mouse thrombopoietin (TPO; Peprotech, AF-315-14), 25 ng ml−1 recombinant animal-free mouse FGF-basic (bFGF; Peprotech, AF-450-33). At this time, 1,000 HSCs from GFP-reporter mice were freshly sorted into each well. Half the medium was replenished three days later, and cells were lifted with 0.2% collagenase at day 6 for FACS analysis or retro-orbital transplantation into lethally irradiated (950 rad) 2-month-old recipient mice (together with 300,000 unlabelled helper marrow cells). Wells with HSCs expanded alone for 6 days were included as control. Peripheral blood analysis was conducted at 6 and 12 weeks after injection. Mice were euthanized at the 12-week time point and BM was analysed for donor-derived (GFP+) haematopoietic lineage tree cell populations as described above.

Microarray

Microarray analyses were performed on FACS-purified SSC as well as HSC lineage populations. Cell suspensions from 3–5 different mice were pooled before FACS purification. Five thousand to ten thousand cells of target cell populations were directly sorted into tubes containing 1 ml Trizol. RNA was isolated with a nRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen; 74004) as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA was amplified twice with Arcturus RiboAmp PLUS amplification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; KIT0521). Amplified cRNA was streptavidin-labelled, fragmented and hybridized to Affymetrix 430-2.0 arrays (Affymetrix). Arrays were scanned with a Gene Chip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix) running GCOS 1.1.1 software. Raw microarray data were submitted to Gene Expression Commons (http://gexc.riken.jp), where data normalization was computed against the Common Reference, a large collection (n = 11,939) of publicly available microarray data from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Meta-analysis of the Common Reference also provides the dynamic range of each probe set on the array. Only gene probe sets with dynamic ranges of greater than 6 were selected and in situations in which multiple probe sets for a gene exist, the probe set with the widest dynamic range was used. For ligand-receptor interactions, a connecting line was drawn if gene expression levels exceeded +25%. Data are publicly available under GSE34723 as well as https://gexc.riken.jp/models/2399 and https://gexc.riken.jp/models/2400.

Bulk RNA sequencing

Ten thousand SSCs were freshly FACS-purified from 10-day-old fracture calluses of 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old B6 mice (n = 3 each). Bulk mRNA was processed and sequenced as described before43. In brief, RNA was isolated with Qiagen miRNeasy kit (1071023), cDNA was prepared using the Clontech Smarter Ultra Low Input RNA kit (Takara Bio, 634848), and libraries were generated with the Clontech Low Input Library Prep kit (Takara Bio, 634947). The barcoded samples were pooled and then sequenced on four lanes of NextSeq 500 (Illumina) to obtain 2 × 76 base-pair paired-end reads (average no. of mapped reads per sample: around 45 million). Bulk mRNA-sequencing data were analysed as described before43. In brief, raw FASTQ reads from each lane were merged and then aligned to the GENCODE v.M20 mouse reference transcripts (GRCm38.p6) with Salmon44 v.0.12.0 using the–seqBias,–gcBias,–posBias,–useVBOpt,–rangeFactorizationBins 4, and–validateMappings flags and otherwise default parameters for paired-end mapping. Salmon results were merged into a single gene-level transcripts per million (TPM) matrix using the R package tximport45 v.1.10.1 and log2-normalized. Raw and processed data are available from GEO with accession number GSE166441.

Smart-seq2 scRNA-seq

Single cells were isolated by FACS as described above from freshly processed long bones pooled from 3–5 mice of either postnatal day 3 (0-month-old), 2-month-old or 24-month-old B6 mice. Single cells were captured in separate wells of a 96-well plate containing 4 μl lysis buffer containing 1 U μl−1 RNase inhibitor (Clontech, 2313B), 0.1% Triton (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 85111), 2.5 mM dNTP (Invitrogen, 10297-018), 2.5 μM oligo dT30VN (IDT, custom: 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACT30VN-3’), and 1:600,000 ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix 2 (ERCC; Invitrogen, 4456739)) in nuclease-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10977023). Cells were spun down and plates kept at −80 °C until cDNA synthesis. cDNA synthesis from single-cell RNA was performed using oligo-dT primed reverse transcription with SMARTScribe reverse transcriptase (Clontech, 639538) and a locked-nucleic acid containing template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO; Exiqon, custom: 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACATrGr G+G-3’). PCR amplification was conducted using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, KK2602) with ISPCR primers (IDT, custom: 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3’). Amplified cDNA was then purified using 0.6× volume of Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, A63882). cDNA was quantified by high-sensitivity AATI 96-capillary fragment analyser (Advanced Analytical, Agilent HS NGS Fragment Kit (1–6,000 bp)). Concentration of wells containing single-cell cDNA was averaged to determine a dilution factor used to normalize each well to the desired concentration range (0.05–0.16 ng μl−1). The content of four 96-well plates was then consolidated into 384-well plates without cherry-picking or removing wells not holding any single-cell cDNA. Subsequently the 384-well plates were used for library preparation (Nextera XT kit; Illumina, FC-131-1096) using a semi-automated pipeline. The barcoded libraries of each well were pooled, cleaned-up and size-selected using two rounds (0.35× and 0.75×) of Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), as recommended by the Nextera XT protocol (Illumina). Pooled libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq6000 (Illumina) to obtain 2× 101-bp paired-end reads.

Single-cell data processing and analysis

scRNA-seq data were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq2 2.18 (Illumina). Raw reads were further processed using skewer v.0.2.2 for 3’ quality trimming, 3’ adaptor trimming, and removal of degenerate reads46. Trimmed reads were then mapped to the mouse genome v.M20 using STAR v.2.6.1plus47 (with an average of more than 70% of uniquely mapped reads), and counts per million (CPM) was calculated using RSEM v.1.3.1plus48. Data were explored and plots were generated using the Scanpy package (v.1.8.0.)49. To select for high-quality single cells, cells with fewer than 250 genes and fewer than 2,500 counts were excluded. Genes that were detectable in fewer than 3 cells across all cells were also removed. In addition, any cells exceeding 7.5% mitochondrial and 5% ribosomal gene content as well as with a ERCC fraction higher than 30% were excluded. After these stringent quality filtering steps 65 0-month-old SSCs, 170 2-month-old SSCs and 67 24-month-old SSCs were used for downstream analysis. Raw CPM values were mean- and log-normalized. Batch correction using Scanpy integrated ComBat was applied for cells derived from separate 96-well processing plates followed by data scaling. Clustering of single-cell data was done using UMAP (v.0.4.6.) and leidenalg (v.0.8.2.). Principal component (PC) elbow plots were used to select the number of PCs for each clustering analysis. Genes were ranked and differential expression between groups was assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann–Whitney U) for identification of cluster-specific genes. Cell-cycle status was assessed using the ‘score_genes_cell_cycle’ function with the updated gene list provided previously50. Lineage trajectory inference was performed using scvelo - RNA velocity51. Differences in developmental state were assessed with CytoTrace52. Differentially expressed genes between 24-month-old and 0-month-old or 2-month-old groups were tested for GO enrichment using the Enrichr53 Webserver version of GO Biological Processes. Only significantly enriched GO terms were considered (adj. P < 0.1) and provided combined statistical scores are shown in the figures. Analysis of filtered high-quality single cells revealed a high transcriptomic similarity of top expressed genes between SSCs of different age groups despite significantly lower total gene counts in 24-month-old SSCs (Fig. 3a, b, Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Analysed cells showed no notable expression of genes related to apoptosis or senescence across all cells, in line with unaltered telomerase activity between 2-month-old and 24-month-old SSCs (Extended Data Fig. 6c-e, Supplementary Data 1). Of note, as reported for tissue dissociation protocols, stress-induced gene expression was observed in single SSCs, albeit limited to cells from 2-month-old mice54,55 (Extended Data Fig. 6f). This might point to a more sensitive environmental sensing of 2-month-old SSCs that in turn, at least to some extent, explains the strong responses of the same group when exposed to aged blood during parabiosis experiments. Expression of stress-associated genes, total read count per cell, and cell cycle status had no dominant effect on leiden cluster distribution (Extended Data Fig. 6g-j). Data and processing notebook are available under GEO accession number GSE161946.

10X Genomics scRNA-seq

Fracture callus tissue was collected from 24-month-old mice at day 10 after injury. Three fracture calluses from PBS-treated mice (control) and aCSFlow- and BMP2-treated mice each were processed, digested and prepared for FACS as described above. Single-cell solutions of each treatment group were then pooled (n = 3 per group) and 2 × 105 PI-TER119- cells were sorted into collection tubes containing FACS buffer. Cells were then processed with 10X Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ GEM kit (10X Genomics, v.3.1) according to the manufacturer’s instruction to target 10,000 cells per group. Barcoded samples were demultiplexed, aligned to the mouse genome (v.M20), and UMI-collapsed with the Cell Ranger toolkit with standard settings and the force pipeline set to 10,000 cells (v.4.0.0, 10X Genomics), and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 platform yielding an average of 80,589 reads per cell and a median of 1,633 genes per cells for the PBS control group and 100,053 reads per cell and a median of 2,062 genes per cells for the aCSFlow- and BMP2-treated group. We used the Scanpy package (v.1.8.0.)49 to explore the data. First, quality filtering to exclude multiplets and cells of poor quality was conducted by only keeping cells with a gene count of more than 250 and fewer than 3,000, with less than 10% mitochondrial and 20% ribosomal gene content, leaving 17,230 cells. Genes expressed in fewer than three cells across all cells were also removed from downstream analysis. Data were log-normalized, batch-corrected (for treatment groups) with ComBat implementation and scaled for analysis. Dimensionality reduction and Leiden clustering as well as subclustering were conducted choosing parameters based on PCA elbow plots. All further analyses were conducted as described for Smart-seq2 above. Data and processing notebook are available under GEO accession number GSE172149.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance between two groups was determined using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test unless stated otherwise in the figure legend. Normality was assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test. If normality was not met, a Mann–Whitney test was used. If data showed unequal variances (F-test) the t-test was adjusted with Welch’s correction. For comparison of more than two groups, ANOVA analysis was used with an appropriate post-hoc test as described in the figure legends. P values were considered significant if P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad). All data points represent biological replicates, unless otherwise indicated in the figure legend. All data are presented as mean + s.e.m. unless otherwise stated in the figure legend.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Extended Data

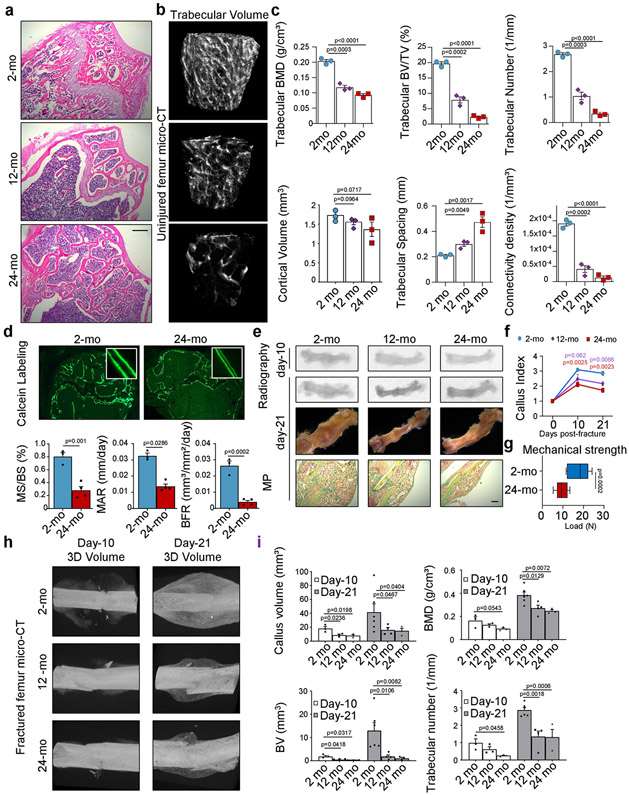

Extended Data Fig. 1 ∣. Ageing alters bone physiology and fracture healing in mice.

a, Representative haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of proximal femurs from 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice (representative of sections from three independent mice per age group). b, Three-dimensional μCT reconstruction of femoral bone mass in 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice. c, Quantification of bone parameters by μCT measurements in the three age groups (n = 3 per age group). d, Bone formation rate (BFR) assessment by calcein labelling in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 3 per age group). MS, mineralizing surface; BS, bone surface; MAR: mineral apposition rate. e, Radiograph, μCT, and Movat’s pentachrome staining images of fracture calluses at day 10 and day 21 after injury. f, Callus index measurements at day 10 and day 21 after fracture in femurs from 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice (day 10 12-mo, n = 5; all other groups, n = 3). g, Mechanical strength test of fracture calluses at day 21 after fracture (2-mo, n = 10; 24-mo, n = 8). Box-and-whisker plots with centre line as median, box extending from 25th to 75th percentile and minimum to maximum values for whiskers. h, μCT images of fracture calluses from 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mouse femurs at day 10 and day 21 after injury. i, Quantification of fracture callus parameters by μCT measurements in the three age groups (n = 3–6). All scatter plot data are mean + s.e.m. One-sided Student’s t-test for comparison of ageing groups to the 2-month-old group, adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bars, 150 μm.

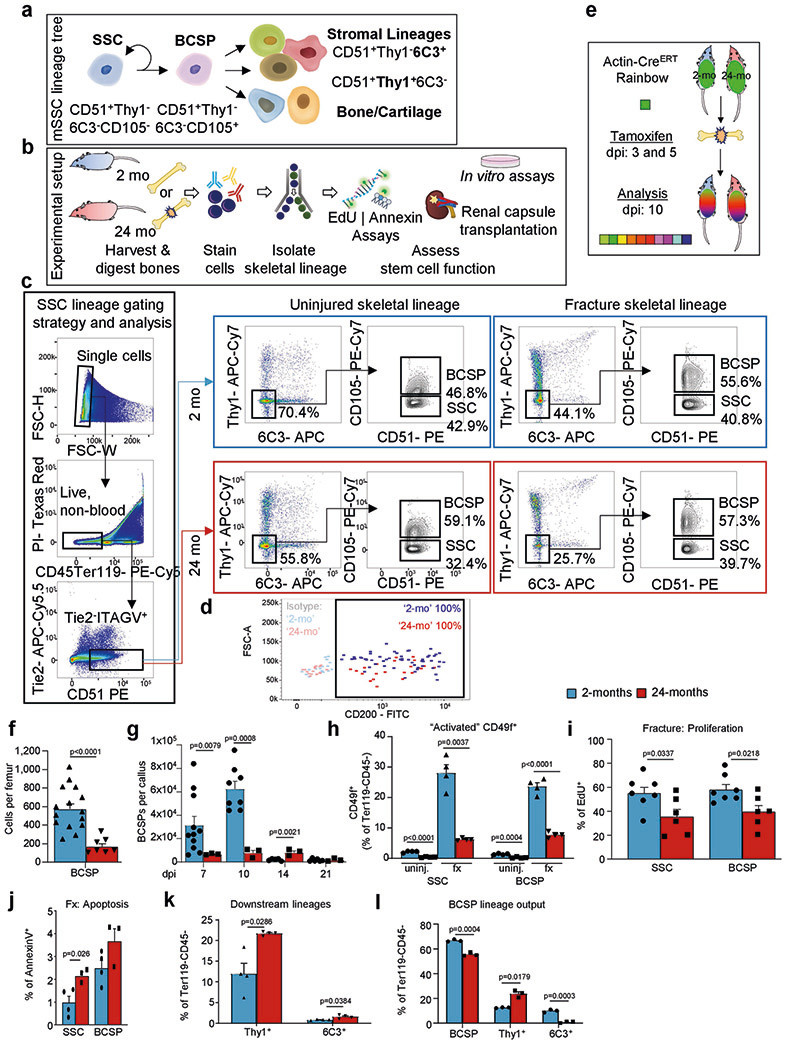

Extended Data Fig. 2 ∣. Phenotypic SSCs are present in aged mice.

a, The mouse skeletal stem-cell lineage. A self-renewing SSC gives rise to a BCSP cell which is the precursor for committed cartilage, bone and stromal lineages. b, Schematic of experimental strategy to analyse intrinsic characteristics of highly purified SSC lineage cells from 2-month-old or 24-month-old mice. c, FACS gating strategy for the isolation of mouse SSC lineage cells. Representative FACS profiles for 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice are shown during the uninjured state and the day-10 fracture state. d, CD200 expression of SSC gated cells in 2-month-old (blue) and 24-month-old (red) mice. Isotype controls performed on SSCs from 2-month-old or 24-month-old mice are shown for gating of the CD200-positive fraction. e, Schematic representation of the experimental set-up investigating clonal activity in fractures of 2-month-old or 24-month-old Actin-CreERT Rainbow mice (dpi, days post-injury). f, Flow cytometric quantification of BCSPs per uninjured femur (2-mo, n = 15; 24-mo, n = 7). g, Prevalence of BCSPs at different days after fracture injury in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (2-mo, n = 5-11; 24-mo, n = 3). h, Flow cytometric analysis of CD49f+ phenotypic SSCs and BCSPs under uninjured (uninj.) and fractured (fx; day 10) conditions in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 4 per state, age and population). i, Proliferative activity within SSCs and BCSPs at day 10 after fracture as measured by EdU incorporation (2-mo, n = 7; 24-mo, n = 6).j, Assessment of apoptotic activity within SSCs and BCSPs at day 10 after fracture as measured by Annexin V staining (2-mo, n = 4; 24-mo, n = 3). k, Flow cytometric quantification of THY1+ and 6C3+ downstream cell population frequency in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice in response to fracture at day 10 after injury (n = 4 per age). l, Flow cytometric analysis of the lineage output of BCSPs freshly isolated from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice and cultured for six days (n = 3 per age). Comparison of 2-month-old and 24-month-old age groups by two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann-Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data.

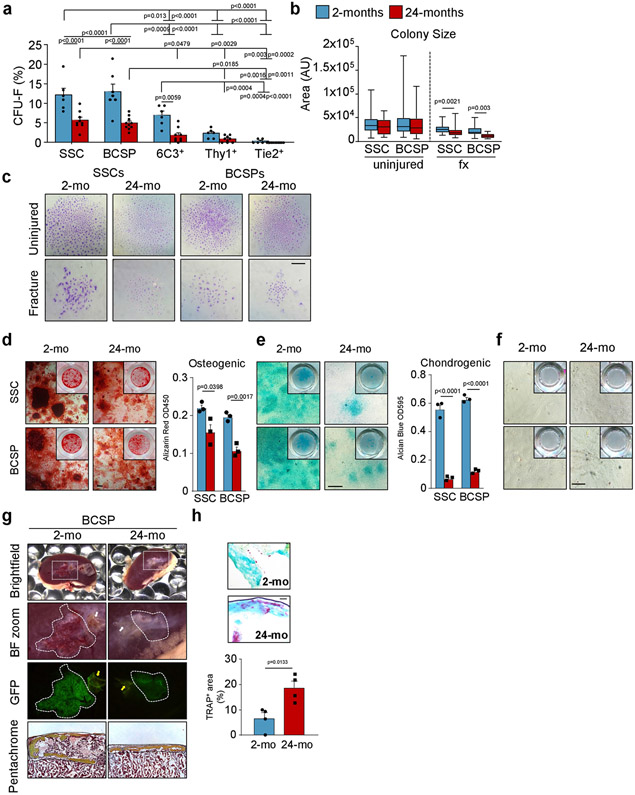

Extended Data Fig. 3 ∣. SSCs and BCSPs show reduced functionality in vitro and in vivo.

a, Fibroblast colony forming unit (CFU-F) ability of 2-month-old and 24-month-old SSC-derived cell populations of long bones (2-mo, n = 5-6; 24-mo, n = 9-10). Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. b, SSC- and BCSP-derived colony size of cells derived from uninjured and day-10-fractured bones (n = 7–120). Statistical testing between age groups by unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test for non-normality. c, Representative images of colonies stained by Crystal Violet (representative of CFU-F from three independent experiments). d, In vitro osteogenic capacity of SSCs and BCSPs from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice as determined by Alizarin Red S staining. Representative staining (left) and quantification of osteogenesis (right) (n = 3 per age). e, In vitro chondrogenic capacity of SSCs and BCSPs from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice as determined by Alican Blue staining. Representative staining (left) and quantification of chondrogenesis (right) (n = 3 per age). f, In vitro adipogenic capacity of SSCs and BCSPs from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice as determined by Oil Red O staining. g, Renal capsule transplantation results of grafts excised 4 weeks after transplantation of GFP-labelled BCSPs derived from long bones of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. Representative gross images of kidneys and magnified graft as bright-field images and with GFP signal shown, for cells derived from 2-month-old (left) and 24-month-old (right) mice. Sectioned grafts stained by Movat’s pentachrome are displayed at the bottom. White and yellow arrows point at auto-fluorescent collagen sponge, which is not part of the graft (representative of 4 independent mice or experiments per age group). h, TRAP-staining images (top) and quantification (bottom) for osteoclast surfaces in sections derived from SSC-derived renal grafts (n = 4 per age group). Statistical testing by two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bars, 50 μm.

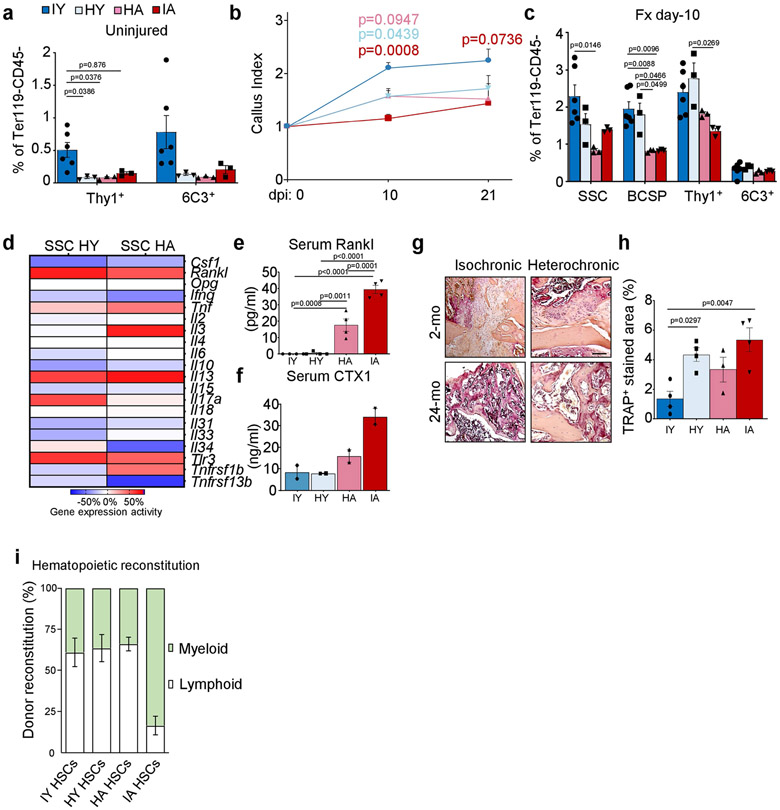

Extended Data Fig. 4 ∣. Exposure to a young circulation does not rejuvenate the SSC lineage.

a, THY1+ and 6C3+ cell frequency as assessed by flow cytometry at four weeks of parabiosis (IY, n = 6; HY, n = 3; HA, n = 3; IA, n = 3). b, Callus index (highest width of callus divided by bone shaft width next to fracture) for parabiosed mice at day 10 (IY, n = 9; HY, n = 9; HA, n = 6; IA, n = 5) and day 21 (IY, n = 4; HY, n = 5; HA, n = 3; IA, n = 3) after fracture injury. Statistical testing by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. c, SSC lineage frequencies as assessed by flow cytometry at day 10 after fracture (Fx) in parabionts (IY, n = 6; HY, n = 3; HA, n = 3; IA, n = 3). Statistical testing by one-way ANOVA analyses with Tukey’s post-hoc test for all comparisons. d, Microarray-based inflammatory gene expression levels of purified SSCs from HA and HY mice. e, Blood serum concentration of RANKL in the circulation of four-week parabionts (n = 4 per group). f, Blood serum concentration of CTX1 in the circulation of four-week parabionts (n = 2 per group). g, Representative images of TRAP staining of fracture calluses of parabionts. h, Quantification of TRAP staining in fracture calluses of parabionts (IY, n = 4; HY, n = 4; HA, n = 3; IA, n = 4). i, Percentage of myeloid and lymphoid reconstitution from transplanted HSCs of parabionts into irradiated recipient mice (n = 4 per group). Statistical testing by one-way ANOVA analyses with Tukey’s post-hoc test for all comparisons. All data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bar, 100 μm.

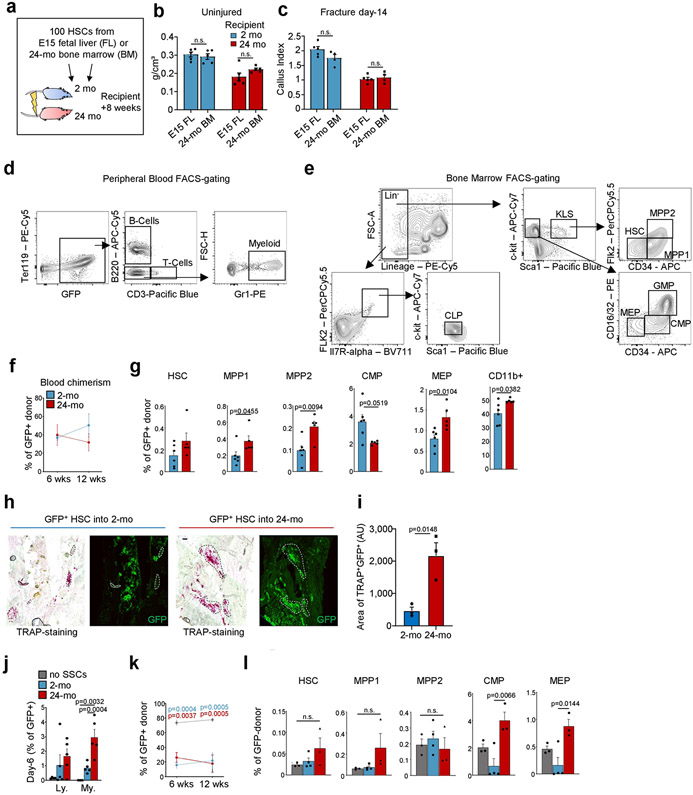

Extended Data Fig. 5 ∣. The bone marrow microenvironment influences HSC lineage output.

a, Schematic of experimental approach for transplanting freshly isolated HSCs from fetal liver or 24-month-old mice into either 2-month-old or 24-month-old lethally irradiated mice. b, BMD in 2-month-old and 24-month-old lethally irradiated mice transplanted with fetal liver (FL) HSCs or HSCs from 24-month-old mice 8 weeks after haematopoietic reconstitution (E15 FL into old mice, n = 6; n = 5, all other groups). BM, bone marrow. c, Callus index of recipient mice at day 14 after fracture induced at the 8-week time point after transplantation (E15 FL groups, n = 5; 24-mo BM groups, n = 4). d, Representative FACS-gating strategy for myeloid (GR1+) and lymphoid (B and T cells) cells in peripheral blood after haematopoietic reconstitution with GFP-donor HSCs (gated from TER119−, live cells). e, Representative bone marrow FACS-gating strategy of GFP+ donor-derived cells for haematopoietic lineage tree populations. f, Peripheral blood analysis for donor chimerism after haematopoietic reconstitution of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice with young HSCs. g, BM analysis of donor-derived (GFP+) HSC lineage cell populations by flow cytometry. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. h, Representative TRAP-staining and GFP-fluorescence images (same section) from day-10 fracture calluses of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice reconstituted with GFP-labelled HSCs from 2-month-old mice. i, Quantification of the total area of TRAP+GFP+ regions in sections of fracture calluses of mice (n = 3 per age group).j, Flow cytometric analysis of lymphoid and myeloid cell types in 6-day co-cultures (no SSCs, n = 4; 2-mo, n = 5; 24-mo, n = 5). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc test for comparison of more than two groups. k, Peripheral blood analysis for donor chimerism after haematopoietic reconstitution with co-cultured haematopoietic cells. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. l, Bone marrow analysis of co-cultured donor-derived (GFP+) HSC lineage cell populations by flow cytometry (no SSCs, n = 3; 2-mo, n = 4; 24-mo, n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for comparison of more than two groups. Comparison of 2-month-old versus 24-month-old groups by two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. All data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data. Scale bar, 100 μm.

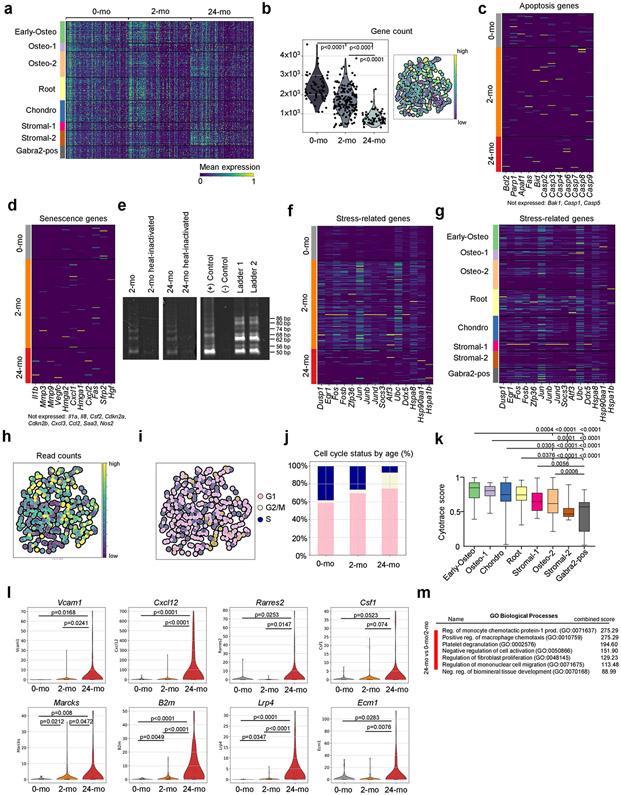

Extended Data Fig. 6 ∣. Distinct transcriptomic signatures in SSCs of different ages.

a, Heat map of the top 150 differentially expressed genes in each age group by Leiden clusters. b, Gene count per single cell as violin plots grouped by age (left) and in a UMAP plot. Statistical testing by Mann–Whitney test. c, Heat map showing the expression of apoptosis-related genes in single-cell data grouped by age. d, Heat map showing the expression of senescence-associated genes in single-cell data grouped by age. e, Electrophoresis gel showing telomerase expression in freshly purified SSCs from 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice. For gel source data, see Supplementary Data 1. f, Heat map showing the expression of tissue digest and stress-associated response genes in single-cell data grouped by age. g, Heat map showing the expression of tissue digest and stress-associated response genes in single-cell data grouped by Leiden cluster. h, Total read count per single cell in UMAP plot. i, Cell-cycle status of single cells illustrated in UMAP plot.j, Proportion of cell-cycle state per age group. k, CytoTrace scores of single SSCs grouped by Leiden cluster (Early-osteo, n = 48; Osteo-1, n = 19; Chondro, n = 48; Root, n = 51; Stromal-1, n = 19; Osteo-2, n = 56; Stromal-2, n = 33; GABRA2+, n = 28 single cells). Data are shown as box-and-whisker plots with centre line as median, box extending from 25th to 75th percentile and minimum to maximum values for whiskers. l, Single-cell data of selected age-associated genes related to enhanced bone loss and support of osteoclastogenesis, shown as violin plots grouped by age. Statistical testing between age groups by two-sided Student’s t-test adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. m, EnrichR GO analysis of differentially expressed genes of SSCs from 24-month-old versus 0-month-old or 2-month-old SSCs and their relation to cell function as determined by GO Biological Processes.

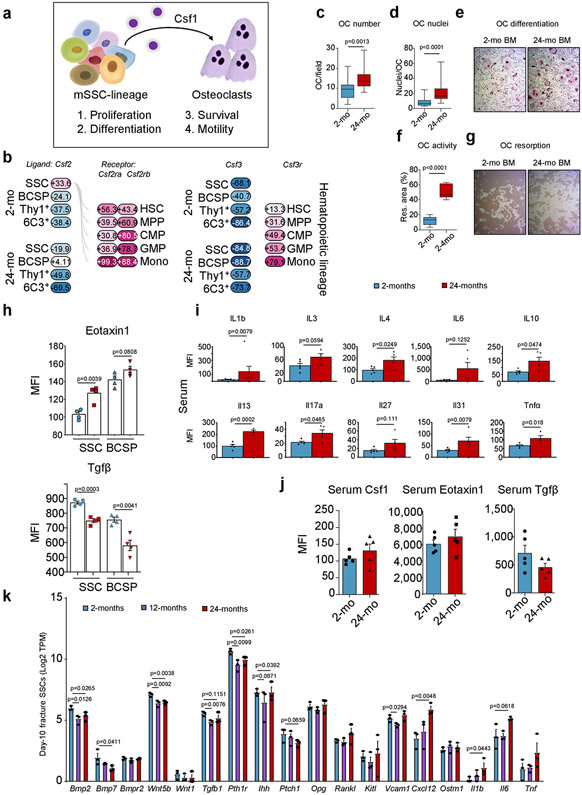

Extended Data Fig. 7 ∣. Skeletal-lineage-derived CSF1 promotes bone resorption with age.

a, Model of SSC-lineage-derived CSF1 actions as described in the literature for osteoclast function. b, Ligand (Csf2 or Csf3) and receptor (Csf2r or Csf3r) bulk microarray gene expression (%) in the 2-month-old and 24-month-old SSC lineage and in the haematopoietic lineage, respectively. c, Quantification of the number of in-vitro-cultured osteoclasts derived from the bone marrow of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (2-mo, n = 16; 24-mo, n = 18, number per field of view, from three mice per age group). d, Number of nuclei per derived osteoclast (n = 14 per age group). e, Representative bright-field images of in-vitro-derived osteoclasts. f, Quantification of in vitro resorption activity of bone-marrow-derived osteoclasts from the bone marrow of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 5 wells with cells from two different mice per age). g, Representative bright-field images in the same experiment. h, Luminex protein data of eotaxin1 and TGFβ in the supernatant of SSC and BCSP cultures of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 4 per age group). Statistical testing by two-sided Student’s t-test. i, Blood serum concentrations of selected inflammatory markers in 2-month-old and 24-month-old mouse blood (n = 4-5 per age). Statistical testing by two-sided Student’s t-test.j, Blood serum concentrations of CSF1, eotaxin1 and TGFβ in the circulation of 2-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 5 per age). Statistical testing by two-sided Student’s t-test. k, Gene expression of pro-haematopoietic or pro-osteoclastic and pro-osteogenic genes in bulk RNA-sequencing data of SSCs of day-10 fracture calluses from 2-month-old, 12-month-old and 24-month-old mice (n = 3 per age). One-sided Student’s t-test of ageing groups versus 2-month-old group. All data in scatter plots are mean + s.e.m., except c, d, f, which show box-and-whisker plots with centre line as median, box extending from 25th to 75th percentile and minimum to maximum values for whiskers. For exact P values, see Source Data.

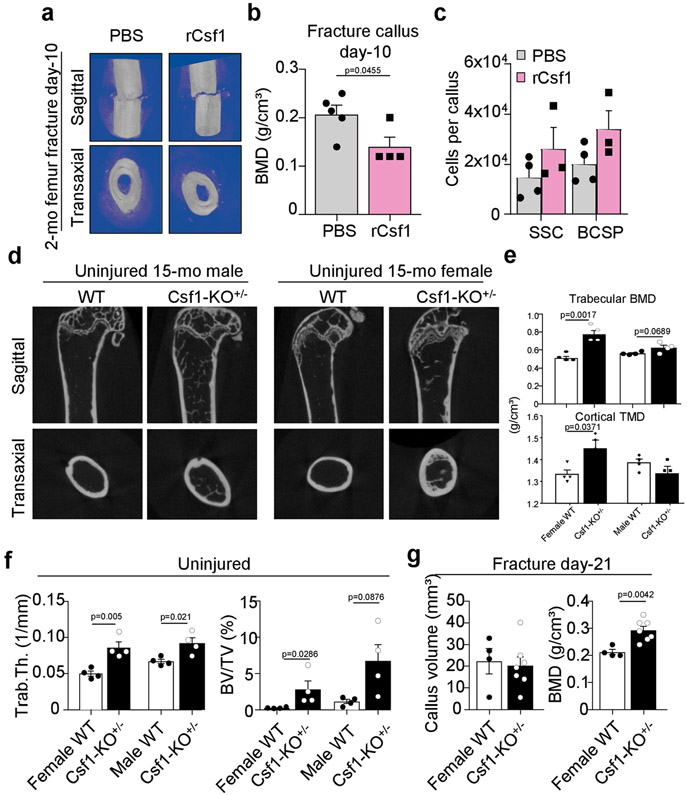

Extended Data Fig. 8 ∣. CSF1 levels control skeletal maintenance and repair.

a, Representative μCT images of day-10 fracture calluses at the time of surgery supplemented with hydrogel containing recombinant CSF1 (5 μg) or PBS as control. b, BMD of day-10 fracture calluses treated with or without rCSF1 (PBS, n = 5; rCSF1, n = 4). c, Total number of SSCs and BCSPs at day 10 assessed by FACS (PBS, n = 4; rCSF1, n = 3). d, Representative μCT reconstructions of femur bones from uninjured wild-type or haplo-insufficient Csf1KO (Csf1KO+/−) 15-month-old female and male mice. e, Trabecular BMD (top) and cortical total mineral density (TMD; bottom) of femur bones from female and male wild-type and Csf1KO mice (n = 4 per genotype and sex). f, Bone parameters quantified by μCT from uninjured 15-month-old wild-type and Csf1KO female and male mice (n = 4 per genotype and sex). g, Bone parameters quantified by μCT from 21-day fracture calluses of 15-month-old wild-type and Csf1KO female mice (WT, n = 4; Csf1KO, n = 7). All comparison of 2-month-old versus 24-month-old groups by two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data.

Extended Data Fig. 9 ∣. Rejuvenating fracture healing in aged mice with defined factors.

a, Schematic representation of experimental set-up of rescue experiments with 24-month-old mice. b, Frequency of BCSPs, THY1+ and 6C3+ in 24-month-old mice at day 10 after fracture induction and application of factors (BMP2: 5 μg; CSF1low: 2 μg; CSF1high: 5 μg) (2-mo PBS, n = 6; PBS, n = 6; CSF1low, n = 5; CSF1high, n = 5; BMP2, n = 5; Combolow, n = 9; Combohigh, n = 5). c, μCT analysis of newly formed mineralized bone volume of treated fracture calluses at day 21 (2-mo PBS, n = 7; PBS, n = 9; CSF1low, n = 6; CSF1high, n = 7; BMP2, n = 12; Combolow, n = 12; Combohigh, n = 8). All two-sided Student’s t-tests between the 2-month-old group and each 24-month-old group adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) or unequal variances (Welch’s test) where appropriate. d, CFU-F capacity of SSCs isolated from fracture calluses from the 2-mo-PBS, PBS and ‘Combolow treatment groups at day 10 (2-mo PBS, n = 6; PBS, n = 6; Combolow, n = 5). Two-sided Student’s t-test between the 2-month-old PBS-treated group and each 24-month-old group adjusted for non-normality (Mann–Whitney test) where appropriate (n.s., not significant). Data are mean + s.e.m. For exact P values, see Source Data.

Extended Data Fig. 10 ∣. Compositional and transcriptomic changes in fracture calluses of aged mice after rescue treatment.

a, Leiden clustering of 10X scRNA-seq experiment of 17,230 fracture callus cells from 24-month-old mice treated with PBS and from 24-month-old mice treated with aCSF1low + BMP2 (Combolow). b, UMAP plot showing expression of selected marker genes for Leiden clusters. c, UMAP plot showing distribution of cells from each treatment group. Red, 24-mo PBS; grey, 24-mo Combolow. d, Percentual fraction of treatment group cells per Leiden cluster. e, Heat map showing positive and negative markers used to identify SSCs. f, Dot plot showing the absence of lymphoid gene expression in 10X datasets. g, UMAP plot with cells labelled by treatment group in 10X dataset subset for cells enriched for haematopoietic gene expression. h, Same UMAP plot showing expression of selected marker genes.

Extended Data Fig. 11 ∣. Graphical abstract of SSC-mediated skeletal ageing.

Loss of skeletal integrity with age owing to reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption is associated with reduced SSC frequency and activity. The 24-month-old skeleton is characterized by increased bone loss, impaired regeneration and lineage skewing of the SSC lineage towards osteoclast-supportive stroma. Skeletal regeneration can be rejuvenated by simultaneous application of recombinant BMP2 and a low dose of an antibody blocking the action of CSF1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements