Abstract

Lamins interact with a host of nuclear membrane proteins, transcription factors, chromatin regulators, signaling molecules, splicing factors, and even chromatin itself to form a nuclear subcompartment, the nuclear lamina, that is involved in a variety of cellular processes such as the governance of nuclear integrity, nuclear positioning, mitosis, DNA repair, DNA replication, splicing, signaling, mechanotransduction and -sensation, transcriptional regulation, and genome organization. Lamins are the primary scaffold for this nuclear subcompartment, but interactions with lamin-associated peptides in the inner nuclear membrane are self-reinforcing and mutually required. Lamins also interact, directly and indirectly, with peripheral heterochromatin domains called lamina-associated domains (LADs) and help to regulate dynamic 3D genome organization and expression of developmentally regulated genes.

The nucleus is structurally organized into functional domains and, as an interpreter and regulator of cellular function, is unique between cell types. In addition to expressing cell-type-specific transcription factors and genome regulators, this diversity is also quite evident at the periphery of the nucleus. The nuclear periphery encompasses the nuclear envelope and the underlying nuclear lamina (Aebi et al. 1986). The nuclear envelope is a dual membrane barrier composed of the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), which is contiguous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The nuclear envelope (NE) is studded with nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) that span the ONM and INM. Underlying the INM is the nuclear lamina, a 10- to 30-nm-thick filamentous meshwork, with its thickness varying between different cell types (Höger et al. 1991). The principal components of the lamina are the type V intermediate filament proteins—the lamins (Fig. 1; Gerace and Huber 2012). In mammals, the lamins are grouped into two classes: A-type (LMNA, LMNAΔ10, and LMNC) and B-type (LMNB1, LMNB2, and LMNB3) (Peter et al. 1989; Vorburger et al. 1989). All metazoans express at least one B-type lamin, with most invertebrates expressing a single lamin gene, although Drosophila has one B-type (Dm0 or Dmel/Lam) and one A-type (DmeI/LamC). In mammals, most adult differentiated somatic cells contain four major lamin proteins (LMNA, LMNB1, LMNB2, and LMNC). A single gene, LMNA, encodes the A-type lamins LMNA and LMNC, along with other minor variants including LMNAΔ10, which are all generated by alternative splicing of a common pre-mRNA (Lin and Worman 1993; Machiels et al. 1996; DeBoy et al. 2017). A minor spliced variant, LMNC2, is also produced in the testis (Furukawa et al. 1994). Separate genes encode LMNB1 and LMNB2 with LMNB3 being produced as a minor spliced variant of LMNB2 and, as with LMNC2, is found in the testis (Furukawa and Hotta 1993; Lin and Worman 1993). All lamin isotypes share a similar overall structure: a head domain, a central α-helical rod domain comprising four coiled-coil domains that enable lamin dimer formation, interspersed by unstructured linkers, followed by a nuclear localization signal (NLS), an Ig-fold domain ending in an unstructured carboxy-terminal tail (detailed in Fig. 2). The basic unit of the lamins is the lamin dimer, which forms protofilaments in a head-to-tail manner and form higher-order assemblies to make the final lamin filament structure (Dechat et al. 2010). In mammals, recent high-resolution light and electron microscopy studies have revealed that the A-, B-, and C-lamin isotypes form their own spatially separate but interacting and overlapping filament networks of 3.5-A tetrameric filaments (Shimi et al. 2008; Turgay et al. 2017), with lamin C showing an apparent preferential association with nuclear pores (Xie et al. 2016). This makes lamin organization in mammalian somatic cells more complex and less regular than previously observed in the frog oocyte lamina (Aebi et al. 1986).

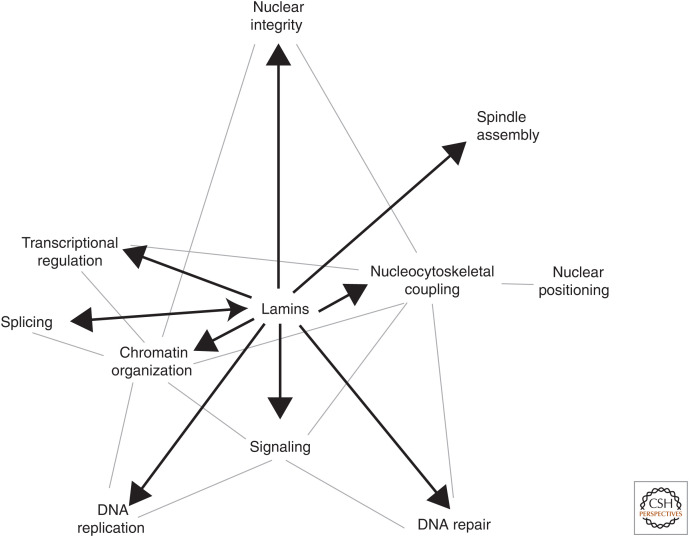

Figure 1.

Lamins—a critical nexus in the regulation of cellular processes. Lamins and their associated proteins (lamin-associated proteins [LAPs] and nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins [NETs]) have been implicated in a wide range of interdependent cellular processes placing lamins at the center of an integrative hub at the nuclear lamina. Black arrows indicate lamin influences on specific pathways and processes and the gray lines indicate cross talk between these processes. These processes include maintaining structural integrity of the nucleus (Shin et al. 2013; Swift et al. 2013; Harada et al. 2014), regulation of transcription through direct interactions with transcription factors as well as signaling pathways (Andrés and González 2009; Ho and Lammerding 2012), and three-dimensional chromatin organization (scaffolding of lamina-associated domains [LADs]) (van Steensel and Belmont 2017; Briand and Collas 2020), which in turn impacts nuclear integrity and structure, since chromatin and lamins collaborate to confer mechanical properties to the nucleus (Chalut et al. 2012; Furusawa et al. 2015; Shimamoto et al. 2017; Stephens et al. 2017; Strickfaden et al. 2020). The nuclear lamina and interacting proteins also regulate other DNA-based processes such as DNA replication (Dorner et al. 2006; Shumaker et al. 2008; Pope et al. 2014) and DNA repair (Redwood et al. 2011; Aymard et al. 2014; Gibbs-Seymour et al. 2015; Lottersberger et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018; Marnef et al. 2019). Linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex (LINC) proteins mediate nucleocytoskeletal coupling, which in turn influences other processes such as signaling, chromatin organization, DNA repair, and gene regulation (through mechanosensation and mechanotransduction) as well as nuclear position through direct interaction of LINCs with cytoskeletal motors (Razafsky et al. 2014; Wong et al. 2021a). Other identified but less commonly known roles of the lamins include splicing and spindle pole assembly (Georgatos et al. 1997; Maison et al. 1997; Kumaran et al. 2002; Tsai et al. 2006; Ma et al. 2009).

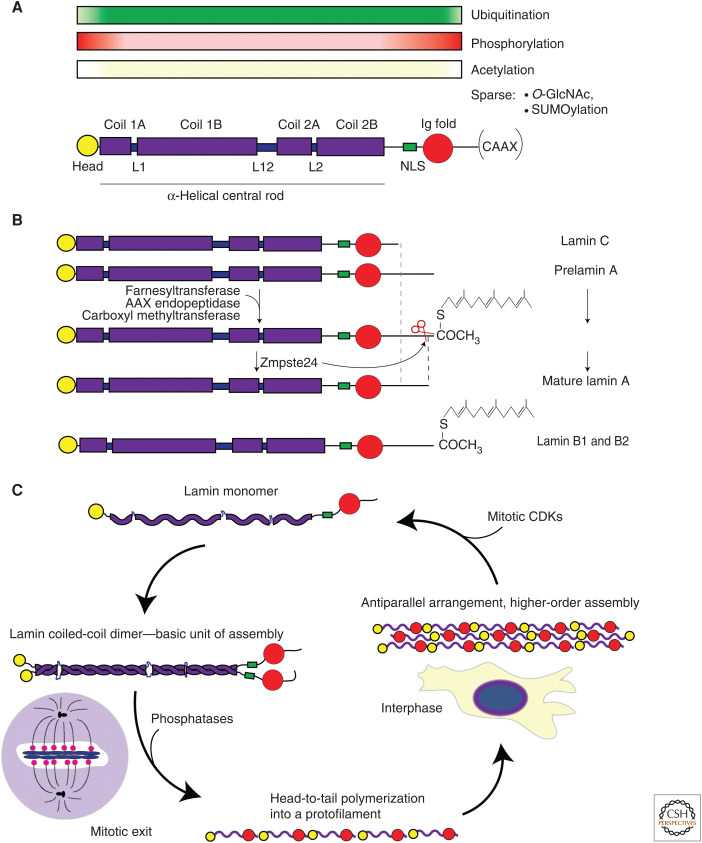

Figure 2.

Assembly, processing, and regulation of lamins. (A) The general structure of a lamin protein, consisting of a short unstructured head domain (yellow), a central α-helical rod domain comprised of four helical subregions (coils 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B in purple) interspersed by unstructured linkers (L1, L12, and L2), a tail region that includes a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (green), an immunoglobulin-fold domain (Ig-fold) (red), and a fairly unstructured carboxy-terminal end that in most cases terminates with a carboxy-terminal CAAX motif (Stuurman et al. 1998; Krimm et al. 2002; Herrmann and Aebi 2004). (Continued) While the rod domain is involved in the dimerization of lamins through coiled-coil interactions, the head and tail domains play a significant role in regulating the higher assembly of lamins (Gieffers and Krohne 1991; Heitlinger et al. 1992; Stuurman et al. 1996; Klapper et al. 1997; Sasse et al. 1998; Izumi et al. 2000; Moir et al. 2000a; Ben-Harush et al. 2009). Also shown are potential posttranslational modifications (PTMs) and their documented density occurring throughout the monomer where the color intensity is proportional to the probability of finding the PTMs. The most highly occurring PTMs, as shown, are phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which exhibit an inverse distribution, with phosphorylation more often occurring near and at the head and tail domains while ubiquitination more frequently found within the central rod domain and extending toward the Ig fold. The distribution pattern of acetylation is similar to that of ubiquitination, albeit less frequently occurring. In contrast, O-GlcNAcylation and SUMOylation are sparse and have been found only on a few residues (Simon and Wilson 2013). (B) A-type lamins (LMNA and LMNC) are the result of alternative splicing from the LMNA gene, while the major B-type isoforms (LMNB1 and LMNB2) are transcribed from two different genes. Both LMNA and LMNB1/2 are farnesylated at the cysteine residue of the –CAAX motif by a farnesyltransferase, followed by the removal of the last three amino acids by means of an AAX endopeptidase and finally carboxymethylation via carboxyl methyltransferase (Dechat et al. 2008). Lamin B1 and B2 remain farnesylated, facilitating their anchorage to the nuclear envelope. LMNA undergoes an additional step: removal of the farnesyl group and the 15 most carboxy-terminal residues by the protease Zmpste24, rendering a fully functional and mature, lamin A protein (Dechat et al. 2008). (C) Depicts principles of lamin assembly and their regulation through the cell cycle. Lamin monomers associate in a parallel, head-to-head manner, leading to a coiled-coil dimer formation—the basic unit for higher-order assembly. As cells enter mitosis, higher-order lamin filaments localized at the nuclear lamina become phosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and potentially other kinases triggering the disassembly of the nuclear lamina as lamins depolymerize and become cytosolic. A-type lamins are found in the cytosol, while depolymerized B-type remain anchored to lipid membranes (Gerace and Blobel 1980). As the cell approaches interphase, lamins are dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 1a (PP1a) and are recruited to and reassembled at the reforming NE (Thompson et al. 1997; Dechat et al. 2010). This reincorporation at the NE is temporally regulated, with B-type lamins organizing to the lamin first, followed by lamin A and then lamin C networks (Pugh et al. 1997; Shimi et al. 2015; Xie et al. 2016; Wong et al. 2020). Importantly, and particularly for A-type lamins, a subpopulation of lamins can remain nucleoplasmic, due to the persistence of mitotic PTMs such as S22P (Simon and Wilson 2013; Gruenbaum and Medalia 2015; Ikegami et al. 2020; Wong et al. 2020).

REGULATION OF LAMINS

Lamin functions are regulated by a myriad of posttranslational modifications (PTMs) (see Fig. 1), especially higher-order assembly into filaments and disassembly during nuclear envelope breakdown as cells enter mitosis. Most prominently, lamins are regulated by phosphorylation, but are also subjected to farnesylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, O-linked sugar modification (O-GlcNAc), and acetylation (Gerace and Blobel 1980; Simon and Wilson 2013; Kochin et al. 2014; Gruenbaum and Foisner 2015; Torvaldson et al. 2015). While the roles of the vast majority of phosphorylation and other modifications to lamin proteins are not understood, there is a clear role for phosphorylation in lamin disassembly in mitosis. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1 or cdc2) directly phosphorylates both A- and B-type lamins during mitosis. Phosphorylation of amino-terminal Serine 22 (S22P) and carboxy-terminal Serine 392 (S392P) in human lamin A/C or analogous residues in B-type lamins near the coiled-coil domains induce the disassembly of the nuclear lamina. Intriguingly, a subset of A-type lamins remains phosphorylated, soluble, and nucleoplasmic during interphase (Gerace and Blobel 1980; Kochin et al. 2014; Torvaldson et al. 2015; Ikegami et al. 2020). While S22P is necessary for lamin depolymerization, it is not sufficient; thus, CDK1 is likely working in concert with other kinases, such as protein kinase C (PKC), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), and AKT to facilitate complete disassembly and to further regulate lamin functions (Torvaldson et al. 2015). It is important to note that the majority of PTM sites of lamins have been identified by mass spectrometry without accompanying mechanistic and functional studies, so there is still much to be understood about the dynamic regulation of lamins through these different modifications and modification sites.

In addition to being regulated by PTMs (and splicing), expression of lamin isotypes is also developmentally regulated, with expression of A-type lamins (LMNA and LMNC) being restricted to more differentiated cells, and each cell type displaying different relative ratios of the different lamin isotypes. All nucleated mammalian cells express at least one B-type lamin, whereas A-type lamins are absent during the early pre- and postimplantation embryonic stages and in embryonic stem (ES) cells, with these types expressing high levels of LMNB1 and LMNB2 (Stewart and Burke 1987; Wong and Stewart 2020). A-type lamins are expressed as different tissues form in the postimplantation embryo, although some tissues and cell types do not express A-type lamins until after birth (Solovei et al. 2013). Lamins appear to be nonessential for ES cells, since ES cells and their derivative progenitors lacking LMNA, LMNC, and LMNB1 proliferate normally in culture, maintain euploidy, and differentiate normally into multiple cell types (Kim et al. 2013). However, it should be noted that the ES culture system reflects early pre-organ development. The story is not as clear-cut in vivo, although A-type lamins are dispensable for early development. Mice lacking either LMNA, LMNC, or both are indistinguishable from normal siblings at birth, possibly because of some functional redundancy with the developmentally regulated INM protein lamin B receptor (LBR) that is expressed (or over- or re-expressed) in cells engineered to lack Lmna (Sullivan et al. 1999; Jahn et al. 2012; Solovei et al. 2013). Loss of Lmna does, however, result in severe postnatal growth retardation and death within 3 weeks, which is correlated to some extent with the normal silencing of LBR expression in many postnatal tissues (Sullivan et al. 1999; Jahn et al. 2012; Solovei et al. 2013). Intriguingly, the ratio of LMNA/LMNC varies across different cell types suggesting cell-type-specific and developmental regulation of LMNA splicing or posttranscriptional regulation. One striking example of differential A/C expression is in neurons where LMNA (and not the LMNC splice variant) translation is inhibited by the microRNA miR-9, which binds specifically to the longer LMNA mRNA 3′ UTR (untranslated region) (Jung et al. 2012). Less is known about the cell and tissue variation of expression of somatic B-type lamins. Both LMNB1 and LMNB2 are required for normal neuronal development (Vergnes et al. 2004; Coffinier et al. 2011). In addition, both human and murine fibroblasts with reduced levels of LMNB1 undergo senescence and display reduced proliferation and loss of LMNB1 correlates with keratinocyte senescence in vivo (Shimi et al. 2011; Dreesen et al. 2013; Shah et al. 2013). In adults, B-type lamin expression appears to be nonessential in some tissues, such as the skin epidermis and liver (Yang et al. 2011). These findings reveal that an absolute dependence on lamin expression in mammals varies among different cell types and that early embryos, including pluripotent cells and some of their differentiated derivatives, may not require any of the lamins for their proliferation and early differentiation.

LAMINS AS A SCAFFOLD FOR THE LAMINA INTERFACE

Lamins interact with a host of nuclear membrane proteins, transcription factors, chromatin regulators, signaling molecules, splicing factors, and even chromatin itself to form a nuclear subcompartment that is involved in a variety of cellular processes such as the governance of nuclear integrity, nuclear positioning, mitosis, DNA repair, DNA replication, splicing, mechanotransduction and -sensation, transcriptional regulation, and genome organization. The INM and the nuclear lamina are interdependent structures held together by mutual molecular interactions between a myriad of INM proteins and the underlying lamina meshwork (Fig. 3; Simon and Wilson 2013; Wong et al. 2014, 2021b). The protein composition at the nuclear periphery has been profiled in various cell types using different approaches. Initially, lamin-associated proteins (LAPs) were identified by cofractionation in nuclei extracted with high concentrations of monovalent salts and ionic detergents (Senior and Gerace 1988; Gerace and Foisner 1994). More recently, nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins (NETs) have been identified by mass spectrometry identification proteins extracted from the NE (Korfali et al. 2012; de Las Heras et al. 2013, 2017; Worman and Schirmer 2015). Additional LAPs have been identified by BioID, a technique to biotinylate proximal proteins, followed by mass spectrometry (Kim et al. 2016; Mehus et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2016; Wong et al. 2021b). While the terms may be used interchangeably for the most part, it is important to note that LAPs are presumed to interact with lamins, but not necessarily the NE, since some lamins are nucleoplasmic and, conversely, NETs are present in the nuclear envelope, but may not interact with lamins or be at the INM. Many new tissue-specific NETs have not been fully characterized.

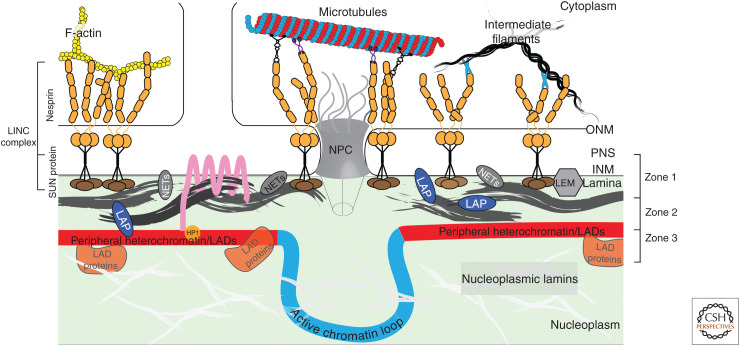

Figure 3.

Structure and complexity at the nuclear periphery. The nuclear lamina serves as an integrative hub for various aspects of nuclear and cellular functions (Wong et al. 2021b). The lamin meshwork(s) (gray), serves to maintain nuclear integrity as well as act as a structural scaffold, anchoring a diverse range of proteins and heterochromatin domains (lamina-associated domains [LADs]) to the nuclear envelope (NE). Lamin-associated proteins (LAPs) and some nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins (NETs) interact with lamins and chromatin. Relatively more well studied, NETs/LAPs include the components that form the linker of cytoskeleton and nucleoskeleton complexes (LINCs) (SUN and KASH domain-containing nesprins), LEM domain proteins, and lamin B receptor (LBR) (pink), shown above. Additionally, the NE also associates with interphase heterochromatin (red chromatin—LADs) providing a structural basis for establishing interphase chromosome topology and at the same time providing a means for transcriptional gene regulation through repression of genes sequestered at the periphery. The tethering of chromatin at the nuclear periphery can be achieved via LBR interactions or lamin A/C. LBR is known to interact directly with chromatin binders (such as Hp1α and PRR14) while A-type lamins may mediate chromatin contacts through LAPs and chromatin binders and modifiers (orange circles) interacting with LADs. A recent comparative proteomics study querying the interaction of lamins, LAP2β and LADs, further resolved the nuclear periphery into three functional zones with respect to chromatin regulation. Zone 1 includes proteins at the INM/lamina that do not interact with LADs, Zone 2 is comprised of proteins that bind the INM/lamina network and LADs—the “middlemen,” and Zone 3 contains only proteins associating uniquely with LADs and chromatin (Wong et al. 2021b).

The LEM (Lap2-Emerin-Man1) domain family of proteins are LAPs/NETs containing a LEM domain that binds a conserved metazoan chromatin protein, barrier to autointegration factor (BAF), allowing their indirect interaction with chromatin (Furukawa 1999; Cai et al. 2001, 2007; Lee et al. 2001; Shumaker et al. 2001; Shimi et al. 2004; Margalit et al. 2007; Kind and van Steensel 2014). Mouse and human LEM domain proteins include LAP2 (lamina-associated polypeptide 2), emerin, and MAN1 along with other LEM and LEM-like proteins (Lin et al. 2000; Schirmer et al. 2003; Lee and Wilson 2004; Brachner et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2006; Ulbert et al. 2006; Simon and Wilson 2013). These LEM domain proteins, like lamins, are strongly conserved, reflecting their fundamental roles in the nucleus. LEM proteins primarily reside in the INM, but LAP2 has several isoforms, at least one of which, LAP2α, lacks a transmembrane domain and is nucleoplasmic; thus, LAP2 can interact with both nucleoplasmic and INM-associated lamins (Harris et al. 1994; Berger et al. 1996; Dechat et al. 1998). Nucleoplasmic LAP2α interacts with nucleoplasmic lamin A (likely phosphorylated) and has been implicated in gene activation (Gesson et al. 2016). LEM domain proteins are translated into the ER membrane and diffuse into the ONM and then retained in the INM via interactions with lamin proteins (Holmer and Worman 2001; Wilson and Foisner 2010; Berk et al. 2013); thus, perturbations of the nuclear lamina can lead to delocalization of these proteins.

Additional well-studied lamin-interacting proteins include INM proteins such as LBR and linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex (LINC) proteins (Fig. 2). LBR is an eight-pass transmembrane protein localized at the INM that contains a nucleoplasmic domain that codes for a sterol reductase. LBR is required for nuclear shape changes, as seen in neutrophils, and is developmentally regulated, with higher expression in ES and progenitor cells. LBR has been shown to interact with heterochromatin organizers HP1 (heterochromatin protein 1) and PRR14 (proline-rich protein 14), and to interact with the repressive heterochromatin modification histone H4 lysine 20 dimethylation (H4K20me2) (Ye et al. 1997; Polioudaki et al. 2001; Hirano et al. 2012; Dunlevy et al. 2020). The LINC complex spans the NE and is formed by interactions between SUN domain proteins of the INM (SUN1 and SUN2 in somatic cells) and the KASH domain proteins of the ONM (nesprins) (Méjat and Misteli 2010; Rothballer and Kutay 2013; Chang et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2015). KASH domain proteins are able to interact with cytoskeletal elements (actin, myosin, and cytosolic intermediate filaments); thus, LINCs physically link the nucleoplasm and lamina to the cytoskeleton, ultimately connecting to the extracellular matrix (ECM) via integrins. It is through these interactions that the nuclear lamina acts as a critical mechanosensing and transduction node (Lombardi and Lammerding 2011; Osmanagic-Myers et al. 2015; Belaadi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Maurer and Lammerding 2019). LINCs are also involved in the cytoplasmic motor-driven movement of the nucleus within the cell (Luxton et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2014) and have been implicated in gene regulation as well (Kim and Wirtz 2015; Tajik et al. 2016). Specific isoforms of nesprins are expressed in different cell types (Duong et al. 2014) and some KASH-less nesprin isotypes can be found at the INM and interact with lamins and emerin directly (Rajgor and Shanahan 2013; Kim et al. 2015).

As mentioned above, during mitosis, lamins are phosphorylated and disassembled. Likewise, LAPs and BAFs are also phosphorylated, thus leading to loss of LAP–lamin interactions (Haraguchi et al. 2001; Foisner 2003; Ellenberg 2013). This leads to the vesiculation or movement into the mitotic ER of these INM proteins. At the onset of anaphase/telophase, these proteins are dephosphorylated and ER/vesicle membranes are recruited back onto chromatin to reform the nuclear envelope and subsequently recruit the lamins. Interestingly, the LEM domain proteins emerin and LAP2β appear to interact with condensed chromatin (mediated through BAF, which is also regulated by mitotic phosphorylation) and interact with different chromatin domains than LBR during NE assembly (Haraguchi et al. 2001; Dechat et al. 2004). Thus, while in the interphase, nuclear lamins retain the LAP INM proteins and prevent their redistribution to the ONM and ER, after mitosis membrane-bound LAPs scaffold on chromatin and subsequently recruit the nuclear lamins, highlighting the interdependence of interactions and the lamina interface.

CELL- AND TISSUE-SPECIFIC INM/LAMINA PROTEOMES

Many of the proteins that are resident to the peripheral zone of the nucleus—the lamins, LAPs, and NETs—are differentially expressed (Figs. 3 and 4; Furukawa and Hotta 1993; Furukawa et al. 1994; Alsheimer et al. 1999; Schütz et al. 2005a,b; Chen et al. 2006; Korfali et al. 2010, 2012; Jung et al. 2012; Solovei et al. 2013). This has been highlighted in several proteomic studies using isolated NE from different cell and tissue types that have identified many new tissue- and cell-specific NET proteins. These experiments uncovered an impressive proteomic diversity of this cellular compartment. In particular, a comparative study across three disparate tissues (liver, leukocytes, and muscle) revealed that the majority of the 598 NETs displayed distinct expression profiles between the tissues examined, with only a modest 16% of these identified NETs being shared across all three tissue types (Korfali et al. 2012). Other high throughput studies have documented differential NE proteomes even in less disparate cell types, such as during T-cell activation and in addition, using mRNA expression analyses, during myogenesis. These types of studies will undoubtedly continue to identify additional novel and differential NET proteins and profiles. How such changes to the nuclear peripheral proteome affects cellular process and behavior and how their deregulation would allow the manifestation of disease phenotypes would be of particular interest (Wong et al. 2014).

Figure 4.

Tissue- and cell-type proteomic diversity at the nuclear lamina. (A) The inferred tissue-specific expression of nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins (NETs) determined by a transcriptomic analysis (Chen et al. 2006). For this representation, the proteins were binned into three expression groups for each tissue type examined: low (green), medium (orange), and high (red). It is clear, even given the small number of proteins considered here, how different the NE proteome is in divergent cell types. It has been shown for a few cardiomyopathy lamin mutations that chromatin organization is perturbed in induced pluripotent stem cells derived cardiomyocytes in the form of gain and loss of lamina-associated domains (LADs), thereby affecting transcriptional output and lineage commitment. (Continued) The same mutations, however, have no impact on LAD architecture in hepatocytes and adipocytes, underscoring the tissue specificity of lamin mutations (Shah et al. 2021). (B) How tissue-specific proteomes at the nuclear periphery can allow differential susceptibility to lamin mutations. In the top panel, the expression of a lamin mutation associated with cardiomyopathy disrupts the function of a cardiomyocyte-specific NET protein (heart shape to broken heart) that may be involved in LAD anchorage, leading to the loss of LADs at the periphery. In adipocytes, however, a different tissue-specific NET may be involved in LAD tethering (depicted as lipid droplets), the function of which is not affected by the same lamin mutation and hence LAD architecture remains unperturbed. It is important to note that such structural reorganization could result from a mutation in either lamin or the NET protein itself. Crossed-out proteins indicate a documented absence of these NETs from the indicated tissue. (Figure adapted from Wong et al. 2014.)

LAMINA-ASSOCIATED DOMAINS (LADs)

The genome is functionally organized, with regions of late-replicating heterochromatin positioned at the nuclear lamina and at the nucleolar periphery in most metazoan cells (Cremer and Cremer 2001). Conversely, more euchromatic regions are positioned in the nuclear interior or interact with NPC (Buchwalter et al. 2019). Not surprisingly, lamins have long been implicated in regulating the three-dimensional (3D) organization of chromatin, particularly via these heterochromatin domains found at the nuclear lamina. 3D genome organization and chromatin compartments were initially identified and studied by microscopy and cytological tools using DNA stains, DNA hybridization techniques such as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), or electron microscopy. These early studies led to an understanding of nonrandom organization of chromatin, including identification of chromosome territories (CTs) and putative regulatory subdomains within the nucleus, including the lamina. These studies relied heavily on identifying spatial relationships between a known sequence (or sequences) and a protein compartment (such as the lamina) in the nucleus. More recently, deep-sequencing-based approaches have led to genome-wide and molecular-level understanding of genome organization and identification of specific DNA sequences and features that accompany such 3D architecture. Three different molecular methods and their derivatives are most routinely used to measure genome organization: chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Ma and Zhang 2020), the proximity-labeling technique DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID) (Orian et al. 2009), and chromatin conformation capture methods such as Hi-C (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009; Belaghzal et al. 2017). ChIP is used to identify chromatin domains and binding sites of chromatin interactors, while DamID and Hi-C directly measure 3D genome organization, with DamID and related techniques measuring proximity to a protein nuclear compartment and Hi-C-related techniques measuring chromatin–chromatin interactions. DamID is most often used to detect peripheral heterochromatin domains, the so-called LADs (Greil et al. 2006; Vogel et al. 2007). Hi-C is used to identify both local and long-range chromatin interactions (Dekker 2002; Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009; Dixon et al. 2012; Phillips-Cremins et al. 2013; Rao et al. 2014; Belaghzal et al. 2017), in particular, local self-interacting regions called topologically associated domains (TADs) and, in active regions of the genome, promoter–enhancer interactions. Of importance to LAD organization, Hi-C also identifies longer-range chromosome and genome-wide self-interacting domains: the A (active) and B (inactive) compartments, with activity state of the compartments being defined via intersections of other data (such as RNA-seq or chromatin state maps by ChIP) (Dekker 2002; Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009; Dixon et al. 2012; Rao et al. 2014). It is important to note that special care must be taken in ChIP assays to identify chromatin state and lamin interactions in heterochromatic regions since these regions are resistant to traditional ChIP fragmentation and isolation protocols (Das et al. 2004; Gesson et al. 2016). An alternative method to DamID is TSA-seq (tyramide signal amplification–seq), another proximity-based method to identify geographic chromatin domains, including LADs (Chen et al. 2018b). These molecular methods are often combined with advanced microscopy approaches, including superresolution FISH technologies and live cell imaging, to complement and extend the molecular findings and to map single-cell chromatin conformations and locus positioning in single cells in situ (Boettiger and Murphy 2020; Kempfer and Pombo 2020). While genome-wide sequencing approaches have the advantage of higher resolution (in base pairs) and numbers of cells processed, imaging approaches are inherently single cell, thus giving an immediate output of cell–cell variability, but also provide additional contextual information, such as cellular state and changes over time. Integration of different data types is key to understanding genome organization generally and this also applies to LADs.

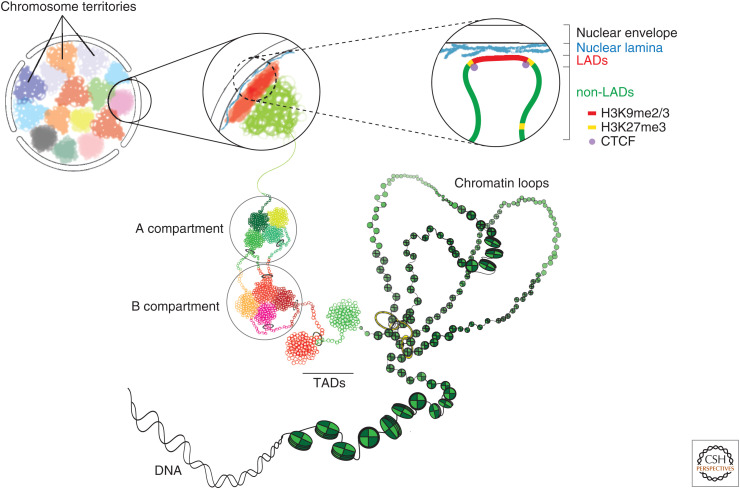

As identified by DamID, LAD regions are large (>100 kb), AT-rich, mostly heterochromatic, and largely correlate with the inactive B compartment as determined by Hi-C (Fig. 5; Dixon et al. 2012; Rao et al. 2014; Fraser et al. 2015; Robson et al. 2017). Although CTCF is found at the boundaries between LADs and non- or inter-LAD (iLAD) regions (Guelen et al. 2008), thus demarcating the transition between B and A compartments, it is depleted within the LADs themselves (Guelen et al. 2008; Harr et al. 2015), suggesting that LADs (and the B compartment) have a fundamentally different organization than the CTCF and cohesin-mediated looping structures found in the active iLAD regions (A compartment). Indeed, depletion of either CTCF or cohesin leads to loss of observable TAD and sub-TAD organization, but A/B compartmentalization is largely maintained with only minor changes, most strikingly the movement of some inactive regions previously constrained in the A compartment to the B compartment (Nora et al. 2017; Schwarzer et al. 2017a). Thus, the genome remains partitioned, even if reconfigured (Nora et al. 2017; Schwarzer et al. 2017b; Falk et al. 2019). It remains unclear, however, whether LADs remain geographically positioned at the nuclear lamina in the absence of CTCF or cohesin.

Figure 5.

Higher-order genome organization in mammalian cells. Shown is a schematic of the levels of chromatin folding within the higher-order 3D genome organization. The DNA interacts with histone octamers and aggregates forming nucleosome arrays that are more or less compacted, depending on the histone variants present and the posttranslational modifications (PTMs) to their amino-terminal tails. The next level of organization is the formation of topologically associated domains (TADs), which in active chromatin domains are formed by loop extrusion via cohesin and stabilized by CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) (Dixon et al. 2012; Rao et al. 2014; Sanborn et al. 2015). TADs and sub-TADs range from tens of kilobases to megabase-sized and have delimited boundaries and high rates of interactions inside of these domains. TADs segregate based on their transcriptional status into active A and inactive B compartments, with A compartments mostly occupying the nuclear interior and B compartments associated with transcriptionally repressive nuclear domains enriched in histone H3 lysine 9 di- and trimethylation (H3K9me2/3) and histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K7me3) at the NE and the periphery of the nucleoli (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009; Harr et al. 2015, 2016; Guelen et al. 2008). It is important to note that A/B compartments exist even if TADs are depleted, suggesting that segregation into A/B compartments is not driven by TAD architecture (Nora et al. 2017; Schwarzer et al. 2017b). The geographic organization of the B compartment to the nuclear envelope (NE) aids in the establishment and/or maintenance of interphase chromosome topology and hence overall genome organization. Moreover, since the nuclear lamina is a transcriptionally repressive compartment, it represents a manipulative model for transcriptional regulation via spatial organizational changes relative to the lamina. The territorial organization of chromosomes in interphase (chromosome territories [CTs]) constitutes a basic feature of nuclear architecture and these other levels of organization occur within the context of CTs (Cremer and Cremer 2010). (Figure based on data in Maeshima et al. 2020.)

GEOGRAPHIC ORGANIZATION OF LADs IS REGULATED BY CHROMATIN STATE

LADs are enriched in histone H3 lysine 9 di- and trimethylation (H3K9me2/3) and this modification is also required for LAD recruitment to and maintenance at the nuclear lamina (Guelen et al. 2008; Towbin et al. 2012; Harr et al. 2015). In mammals, proline-rich protein 14 (PRR14) has been shown to anchor these regions to the lamina through its interactions with heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), a chromodomain protein that binds H3K9me3 (Poleshko and Katz 2014; Dunlevy et al. 2020), while in Caenorhabditis elegans this function is carried out by the INM-bound chromodomain protein CEC-4 (Towbin et al. 2012; Gonzalez-Sandoval et al. 2015; Gonzalez-Sandoval and Gasser 2016; Harr et al. 2016, 2020; Bian et al. 2020). Intriguingly, heterochromatic regions have been shown to accrete due to phase separation directed by HP1α, and the organization of LADs at the lamina likely depends upon such biophysical forces (Larson et al. 2017; Strom et al. 2017; Falk et al. 2019). In particular, biophysical models predict that, in the absence of an active constraint at the nuclear lamina, LADs would form large clusters in the nucleoplasm (Falk et al. 2019). This is supported by studies showing that in cells lacking lamin A/C and LBR (either naturally or engineered) heterochromatin configuration is inverted (Solovei et al. 2013). Thus, the heterochromatic nature of LADs leads to their separation from euchromatic regions, but other forces and interactions are likely at play in geographically organizing these regions to the lamina. There is a less clear role for the facultative heterochromatin modification histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) in LAD organization, since this modification is found mostly outside of LADs, but is enriched at LAD borders (Guelen et al. 2008; Harr et al. 2015) and necessary to target an inserted test locus to the lamina in coordination with H3K9me2/3 (Harr et al. 2015). In contrast, in C. elegans, H3K27me3 modifications seem to be dispensable for driving peripheral localization, but there is a second pathway for lamina localization independent of Cec-4/H3K9me3 anchoring (Towbin et al. 2012). In a clever screen using cec-4 null worms, this second pathway was discovered to be a sequestration of euchromatin away from the lamina (Cabianca et al. 2019). In this case, the delocalization of CBP/p300 causes aberrant H3K27Ac to replace H3K27me3, suggesting that sequestration of active chromatin modifiers is a driving force for tethering of heterochromatin to the lamina in differentiated cells. Similarly, in a recent study in mouse T-cells in which a LAD border region at the T-cell receptor (TCR) locus was deleted, invading H3K27ac was found to drive an enhancer region away from the nuclear lamina and subsequently led to altered enhancer–promoter interactions (Chen et al. 2018a). The role of histone H4 lysine 20 dimethylation (H4K20me2), a repressive chromatin mark bound by the tudor domain of LBR (Hirano et al. 2012), in LAD regulation and organization remains unclear. H4K20me2 has a wide genome distribution with enrichment on centromeric and telomeric chromatin and does not appear to be particularly enriched on LADs (Mattout et al. 2015). However, this modification does seem to play a role in LAD regulation/organization under certain conditions, particularly senescence and in particular laminopathies (Shumaker et al. 2006; Barski et al. 2007; Bártová et al. 2008; Mattout et al. 2015; Nelson et al. 2016). Taken together, these studies suggest a complex interplay between chromatin state and chromatin-binding proteins in the separation and organization of LADs to the periphery.

GENE REGULATION IN LADs

LAD regions contain relatively few genes, but are, conversely, enriched in developmental and lineage-specific genes, leading to the hypothesis that the epigenetic state of these regions is tied to both organization and developmental control of gene expression (Guelen et al. 2008; Peric-Hupkes et al. 2010; Bian et al. 2013; Harr et al. 2015). Indeed, early studies of regulation of individual genes by the nuclear lamina focused on developmentally regulated gene loci, such as the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (Igh) in B-cell development (Kosak et al. 2002), the β-globin locus in erythroid development (Bian et al. 2013), and MyoD in muscle development (Yao et al. 2011) among others. These early studies pointed to the dynamic nature of loci associated with (and presumably regulated by) the nuclear lamina during development, but it was not until genome-wide mapping through DamID that the shifting LAD organization, chromatin, and expression landscape could be fully appreciated. LADs are dynamic between cell states and in a simplistic view can be divided into constitutive or facultative LADs, cLADs, and fLADs, respectively (Peric-Hupkes et al. 2010; Meuleman et al. 2012; van Steensel and Belmont 2017). cLADs are LADs that remain irrespective of cell type, while fLADs reorganize between cell types or developmental stages. The majority of LADs do not change between individual cell types, although 70% of LADs are fLADs; thus, reorganization is restricted by cell type. fLADs are more gene rich and in cell types where they undergo reorganization away from the lamina, genes in these regions are activated or poised for activation (Peric-Hupkes et al. 2010). Even within a given cell type or population there is some cell–cell heterogeneity in LAD organization, as detected by low-resolution, single-cell DamID, with more gene-dense LADs displaying greater fluctuations in their association with the lamina, implying that these disruptions may be due to differential gene usage between cells (Kind et al. 2015). A level of heterogeneity in reorganizing to the lamina after cell division has also been noted, with some LADs appearing to become nucleolar-proximal in the daughter cells, although there is some expected overlap between nucleolar-associated domains (NADs) and LADs given the invaginations of nuclear lamins at nucleoli noted in many cell types (Cremer and Cremer 2001; Legartová et al. 2014; Padeken and Heun 2014).

In addition to LAD heterogeneity between cells, it has been documented that different promoters respond differently to integration into a LAD and to different environments within a LAD. Early ectopic lamina tethering experiments suggested that recruitment to the nuclear lamina reduces expression of the tethered locus. In one report, an integrated reporter gene in mouse cells showed a two- to threefold reduction in expression after tethering using a truncated emerin to tether a lac operator array (lacO) (Reddy et al. 2008). A similar study, using Lap2β to target a lacO array in a human cell line, found only a minimal reduction in the recruited reporter gene expression, while a subset of endogenous flanking genes on the same chromosome did show reduced expression (Finlan et al. 2008). In Drosophila, the tethering of two lacO tagged reporter genes by Dme/LamC to the nuclear lamina caused substantial repression, but the level of repression was integration site and reporter gene dependent (Dialynas et al. 2010). These early results suggested that recruitment to the lamina could cause repression, but that this repression was variable depending upon local chromatin context and different promoters. A more recent study sought to investigate exactly this question and found that upon integration into LADs some promoters are more sensitive to the more repressive environment and are almost universally repressed, while other promoters can “escape” silencing within LAD regions (Leemans et al. 2019). These escapers were generally less sensitive repressive domains, particularly H3K27me3. All promoters showed some variation in regulation by LADs and less repressed promoters were found to reside in more weakly (and perhaps transiently) lamina-bound regions within LADs (Leemans et al. 2019). Thus, even though LADs are generally repressive, genes respond differently depending upon promoter type and local LAD context.

ROLE OF TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS IN LAD ORGANIZATION

While both lamins and chromatin are important for organization of LADs to the nuclear lamina, there is some evidence that transcription factors and machinery may be more directly involved in peripheral localization (and regulation) of genes at the lamina. Several transcription factors have been found to interact with lamins and/or lamin-interacting proteins, and some of these have been proposed to be more directly involved in organizing specific loci to the lamina. One study found that sequences from two different LAD-regulated loci enriched in GA dinucleotides were able to drive an ectopic region to the lamina (Zullo et al. 2012). This is interesting given that GA dinucleotides are not enriched in the relatively AT-rich LADs (Guelen et al. 2008). These motifs were found to bind a cell-type-specific transcription factor (ZBTB7B, also known as THPOK) in complex with a histone deacetylase (HDAC3), and an inner nuclear membrane protein (LAP2β) to mediate de novo interactions with the nuclear lamina. Both ZBTB7B and HDAC3 were also found to be important for myogenesis and in regulating myogenic genes and their organization to the lamina (Poleshko et al. 2017), suggesting that specific transcription factor complexes can regulate lamina interactions, potentially directly. ZBTB7B features a BTB–POZ domain that recruits Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to chromatin, thereby initiating trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (Boulay et al. 2012). Interestingly, there are numerous BTB-POZ domain transcription factors that are expressed in a cell-type-specific manner, and these have been found to both activate and repress gene expression and to interact with HDAC3. HDAC3 itself, which interacts with numerous transcription factor complexes, has been shown in independent studies to interact with both LAP2β and emerin (Somech et al. 2005; Demmerle et al. 2012). Whether this complex of ZBTB7B, HDAC3, and LAP2β initiates locus interaction at the lamina or simply maintains a heterochromatin state is unclear. Other studies suggest that altered chromatin state, including both H3K9me2/3 and H3K27me3, drive lamina association (Bian et al. 2013, 2020; Kind et al. 2013; Harr et al. 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that the epigenetic state may be the ultimate factor in determining organization to the lamina. Lamina-associating sequences may recruit repressive transcriptional complexes to promote a local chromatin signature favorable for lamina association. While at the lamina, these complexes would then maintain or reinforce this repressive state, in agreement with studies showing that integration of promoter sequences into LADs leads to their repression.

LAD ORGANIZATION HELPS ENFORCE CHROMATIN AND GENE EXPRESSION PROGRAMS

If chromatin state drives lamin association, is association with the nuclear lamina simply a by-product of this chromatin state and biophysical properties? It is difficult to tease apart the role that chromatin state itself versus organization to the lamina plays. As discussed previously, recruiting inserted reporter genes to the lamina is able to repress some genes, depending on promoters and integration site (Finlan et al. 2008; Reddy et al. 2008). In addition, biophysical modeling shows that in the absence of nuclear periphery “tethers,” heterochromatin will not organize to the lamina, but is instead predicted to collapse into the center of the nucleus and form an “inverted” type of chromatin organization (Falk et al. 2019). This implies that there are active mechanisms to organize LADs to the nuclear lamina. In support of this, several studies have implicated A-type lamins as especially important for the geographical organization of LADs to the lamina in differentiated cells (Solovei et al. 2013; Harr et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2018). In particular, the predicted inverted chromatin organization is noted in the absence of both A-type lamins and LBRs (Solovei et al. 2013); thus, chromatin organization to the lamina is not the default. But is there evidence that loss of lamin association affects gene regulation—that such localization is itself important? In C. elegans, a global reduction of lamin–chromatin interactions through depletion of the chromobox protein CEC-4, which is required for lamina association, resulted in up-regulation of only one single gene, while depletion of H3K9 methylation caused widespread disruption (Gonzalez-Sandoval et al. 2015). From this experiment, one could conclude that organization of chromatin into LADs at the lamina is not important for gene repression (although there is a second non-CEC-4-dependent anchoring pathway that confounds these results (Cabianca et al. 2019). However, loss of CEC-4 did impair induced differentiation into muscle cells, reminiscent of mouse studies, in which the effect of loss of lamins is seen later in muscle differentiation (Sullivan et al. 1999). In addition, several developmentally regulated tissue-restricted NETs have been shown to cause reorganization of lineage-specific genes and altered expression when ectopically expressed, suggesting that these proteins directly influence organization and regulation (de Las Heras et al. 2017). In cells induced to undergo senescence, alterations in LAD organization were noted, including altered chromatin state outside and inside of LADs, particularly an encroachment across boundaries, suggesting a “blurring” of chromatin domains (Shah et al. 2013). This disorganization and dysregulation could be mimicked by acute depletion of lamin B1, suggesting that, unlike ES cells, more differentiated cells may rely on the geographical organization of heterochromatin to the lamina to maintain a cell-type-specific chromatin landscape. This is in agreement with the idea of LAD organization functioning as a mechanism to maintain a cell-type-specific epigenetic state; some cell types and states will be more sensitive to disruption of LAD organization.

DYNAMIC ORGANIZATION OF LADs THROUGH THE CELL CYCLE

Interphase genome organization, including LAD and lamin organization, is ablated during mitosis and re-established after mitosis (Burke and Ellenberg 2002; Salina et al. 2003; Kind et al. 2013; Naumova et al. 2013; Kind and van Steensel 2014; Gibcus et al. 2018; Luperchio et al. 2018). Several studies have suggested that A-type lamins organize to the reforming nuclear envelope with different kinetics, although there is some discrepancy on how lamin A and C might differ in their timing of association (Pugh et al. 1997; Moir et al. 2000b; Vaughan et al. 2001; González-Cruz et al. 2018). Recent work has not only highlighted how chromosomes condense into their mitotic configuration, but also how these regions reorganize into their interphase configuration postmitosis (Gibcus et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019). These studies focused on chromatin configuration as measured by Hi-C and it is notable that chromatin A/B compartment organization precedes TAD organization, and that compartmentalization intensifies as the cells proceed further into interphase. Given that LADs are highly enriched in the B compartment, such findings highlight a dynamic process of organization of LADs postmitosis. In a clever study using an antibody variant of DamID technology called pA-DamID on synchronized cells, dynamics of LAD organization after mitotic exit were revealed (van Schaik et al. 2020). LADs organize to the nuclear lamina in early G1, with more telomere-proximal LADs interacting first, followed by more centromere-proximal LADs. Because these studies were done in human cells, this stepwise association of different chromosomal positions suggests that the orientation of the chromosomes postmitosis influences LAD organization to the lamina. These associations generally increase as cells progress further into interphase, in agreement with the increased A/B compartmentalization noted in the earlier Hi-C studies. The relationship between LAD organization and lamin reorganization after mitosis remains to be determined.

LAMINOPATHIES

Disruption of the unique protein environment of the nuclear lamina often leads to disease (Table 1). The diseases that result from mutations in LMNA, or other NET or LAP proteins that heavily interact with lamins, are collectively termed “laminopathies” or “envelopathies.” Because of differential expression of lamins during development and in different cell types along with the complex and cell-type-specific interactomes (NETs and LAPs), laminopathies display a wide breadth of phenotypes. Most laminopathies are autosomal dominant and generally cause late-onset degeneration of mesenchymal-derived cells (Wong et al. 2021a). Nearly 500 disease-causing mutations have mapped to the LMNA gene, each with its own specific phenotype, and many of these mutations are dominant. A variety of models have been suggested to explain the variety of cell- and tissue-specific phenotypes. Indeed, it appears that disruption of lamins or lamin-binding proteins affect numerous cellular functions, depending upon the particular mutation and cell type, including perturbations in mechanosensation and resilience, DNA repair, signaling pathways, interactions with specific transcription factor, altered interactions with NETs/LAPs, altered chromatin state, and genome organization, none of which are mutually exclusive (Mewborn et al. 2010; Osmanagic-Myers et al. 2015; Vadrot et al. 2015; Worman and Schirmer 2015; Perovanovic et al. 2016; Le Dour et al. 2017; Briand and Collas 2018; Bianchi et al. 2018; and reviewed in Wong et al. 2021a).

Table 1.

Diseases of the nuclear periphery

| Gene | Disease/anomaly | Other notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary laminopathies | ||

| LMNA | Autosomal-dominant form of Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (AD-EDMD) | Affects striated muscle tissues |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) | ||

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1B (LMG1B). | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy (R298C), a recessive form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (AR-CMT2A) | ||

| Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy (FPLD2) | Affects fat distribution and skeletal development | |

| Mandibuloacral dysplasia (MAD) | ||

| Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) | Premature aging | |

| Atypical Werner's syndrome | ||

| LMNB1 | Adult-onset autosomal-dominant leukodystrophy (ADLD) | Neural |

| Ataxia telangiectasia | ||

| Gene | Function | Disease/anomaly |

| Secondary envelopathies | ||

| Emerin (EMD) | NE associated, may regulate β-catenin nuclear entry and MKL1 nuclear localization | X-linked Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

| Man1 (LEMD3) | Regulates TGF-β signaling by modulating Smad phosphorylation | Buschke–Ollendorff syndrome; excessive bone nodule formation, required for development of the vascular system |

| Lap1/Traf3/TOR1AIP1 | Interacting protein with Torsin, LULL1, and emerin | Myopathy exacerbated by EMD loss |

| LEMD2/Net25 | Chromatin organization MAP/AKT signaling | Homozygote nulls embryonic lethal progeroid; symptoms result from missense mutations |

| Lap2 | Chromatin organization, telomere maintenance | Dilated cardiomyopathy, reduced epidermal proliferation, ameliorates LMNA-induced MD/DCM |

| Torsin | AAA+ATPAse interacts closely with Lap1 | DYT dystonia in CNS, steatohepatitis |

| Lamin B receptor (LBR) | Multifunctional-reduced sterol reductase activity, heterochromatin organization | Pelger–Huët anomaly, Greenberg dysplasia |

| Nesprin1 (SYNE1) | LINC complex tethers nucleus to cytoskeleton | Limb girdle muscular dystrophy; ARCA1 cerebellar ataxia required for nuclear migration during CNS development |

| Nesprin2 (SYNE2) | LINC complex tethers nucleus to cytoskeleton | EDMD variants required for nuclear migration during CNS development |

| Nesprin/Kash4 | Interacts with MT motor proteins | Required for nuclear positioning in cochlear hair cells, mutations result in deafness |

| SUN1 | Anchors LINC complex to the INM, regulates miRNA synthesis during muscle regeneration | Ameliorates LMNA-induced DCM/MD, missense mutations associated with MD |

| BANF1 | Postmitotic nuclear reassembly, chromatin organization | Nestor–Guillermo progeria |

Data adapted from Wong and Stewart (2020).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The multiple functions of lamins and the nuclear lamina make it very difficult to assess the impact of lamina abnormalities on diseases initiated by LMNA or NET mutations. In laminopathies, both gene dysregulation and the loss of nuclear integrity seem to play a role in observed phenotypes. Since this interface controls both the mechanical “fitness” of the nucleus (through LINCs, lamins, and heterochromatin scaffolding) as well as genome regulation, it will be interesting to determine how mechanical force relates to genome organization. In addition, while it is clear that lamina association frequently represses genes, how LADs are mechanistically maintained at and/or reorganized to the nuclear periphery during interphase and particularly during mitotic exit are only recently getting unraveled. Systematic study of how candidate factors (including lamin isotypes, chromatin interactors, NETs, and mechanical inputs) influence LAD and lamina organization during mitosis to G1 may help provide more definitive answers on the role of these regulators in lamina and LAD organization and regulation, and the consequences of their disruption in disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding sources were NIHR01GM132427 to K.L.R. and A.J.M-P. and NIH R25GM109441 to A.J.M.-P.

Footnotes

Editors: Ana Pombo, Martin W. Hetzer, and Tom Misteli

Additional Perspectives on The Nucleus available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Aebi U, Cohn J, Buhle L, Gerace L. 1986. The nuclear lamina is a meshwork of intermediate-type filaments. Nature 323: 560–564. 10.1038/323560a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsheimer M, von Glasenapp E, Hock R, Benavente R. 1999. Architecture of the nuclear periphery of rat pachytene spermatocytes: distribution of nuclear envelope proteins in relation to synaptonemal complex attachment sites. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1235–1245. 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés V, González JM. 2009. Role of A-type lamins in signaling, transcription, and chromatin organization. J Cell Biol 187: 945–957. 10.1083/jcb.200904124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aymard F, Bugler B, Schmidt CK, Guillou E, Caron P, Briois S, Iacovoni JS, Daburon V, Miller KM, Jackson SP, et al. 2014. Transcriptionally active chromatin recruits homologous recombination at DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 366–374. 10.1038/nsmb.2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bártová E, Krejcí J, Harnicarová A, Galiová G, Kozubek S. 2008. Histone modifications and nuclear architecture: a review. J Histochem Cytochem 56: 711–721. 10.1369/jhc.2008.951251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaadi N, Millon-Frémillon A, Aureille J, Guilluy C. 2018. Analyzing mechanotransduction through the LINC complex in isolated nuclei. The LINC Complex 1840: 73–80. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8691-0_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaghzal H, Dekker J, Gibcus JH. 2017. Hi-C 2.0: an optimized Hi-C procedure for high-resolution genome-wide mapping of chromosome conformation. Methods 123: 56–65. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Harush K, Wiesel N, Frenkiel-Krispin D, Moeller D, Soreq E, Aebi U, Herrmann H, Gruenbaum Y, Medalia O. 2009. The supramolecular organization of the C. elegans nuclear lamin filament. J Mol Biol 386: 1392–1402. 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R, Theodor L, Shoham J, Gokkel E, Brok-Simoni F, Avraham KB, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Rechavi G, Simon AJ. 1996. The characterization and localization of the mouse thymopoietin/lamina-associated polypeptide 2 gene and its alternatively spliced products. Genome Res 6: 361–370. 10.1101/gr.6.5.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk JM, Tifft KE, Wilson KL. 2013. The nuclear envelope LEM-domain protein emerin. Nucleus 4: 298–314. 10.4161/nucl.25751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Q, Khanna N, Alvikas J, Belmont AS. 2013. β-Globin cis-elements determine differential nuclear targeting through epigenetic modifications. J Cell Biol 203: 767–783. 10.1083/jcb.201305027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Q, Anderson EC, Yang Q, Meyer BJ. 2020. Histone H3K9 methylation promotes formation of genome compartments in Caenorhabditis elegans via chromosome compaction and perinuclear anchoring. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117: 11459–11470. 10.1073/pnas.2002068117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A, Manti PG, Lucini F, Lanzuolo C. 2018. Mechanotransduction, nuclear architecture and epigenetics in emery dreifuss muscular dystrophy: tous pour un, un pour tous. Nucleus 9: 321–335. 10.1080/19491034.2018.1460044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger A, Murphy S. 2020. Advances in chromatin imaging at kilobase-scale resolution. Trends Genet 36: 273–287. 10.1016/j.tig.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay G, Dubuissez M, Van Rechem C, Forget A, Helin K, Ayrault O, Leprince D. 2012. Hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) recruits polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to a subset of its target genes through interaction with human polycomb-like (hPCL) proteins. J Biol Chem 287: 10509–10524. 10.1074/jbc.M111.320234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachner A, Reipert S, Foisner R, Gotzmann J. 2005. LEM2 is a novel MAN1-related inner nuclear membrane protein associated with A-type lamins. J Cell Sci 118: 5797–5810. 10.1242/jcs.02701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand N, Collas P. 2018. Laminopathy-causing lamin A mutations reconfigure lamina-associated domains and local spatial chromatin conformation. Nucleus 9: 216–226. 10.1080/19491034.2018.1449498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand N, Collas P. 2020. Lamina-associated domains: peripheral matters and internal affairs. Genome Biol 21: 85. 10.1186/s13059-020-02003-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwalter A, Kaneshiro JM, Hetzer MW. 2019. Coaching from the sidelines: the nuclear periphery in genome regulation. Nat Rev Genet 20: 39–50. 10.1038/s41576-018-0063-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B, Ellenberg J. 2002. Remodelling the walls of the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 487–497. 10.1038/nrm860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabianca DS, Muñoz-Jiménez C, Kalck V, Gaidatzis D, Padeken J, Seeber A, Askjaer P, Gasser SM. 2019. Active chromatin marks drive spatial sequestration of heterochromatin in C. elegans nuclei. Nature 569: 734–739. 10.1038/s41586-019-1243-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M, Huang Y, Ghirlando R, Wilson KL, Craigie R, Clore GM. 2001. Solution structure of the constant region of nuclear envelope protein LAP2 reveals two LEM-domain structures: one binds BAF and the other binds DNA. EMBO J 20: 4399–4407. 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M, Huang Y, Suh JY, Louis JM, Ghirlando R, Craigie R, Clore GM. 2007. Solution NMR structure of the barrier-to-autointegration factor-Emerin complex. J Biol Chem 282: 14525–14535. 10.1074/jbc.M700576200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalut KJ, Höpfler M, Lautenschläger F, Boyde L, Chan CJ, Ekpenyong A, Martinez-Arias A, Guck J. 2012. Chromatin decondensation and nuclear softening accompany Nanog downregulation in embryonic stem cells. Biophys J 103: 2060–2070. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. 2015. Accessorizing and anchoring the LINC complex for multifunctionality. J Cell Biol 208: 11–22. 10.1083/jcb.201409047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IHB, Huber M, Guan T, Bubeck A, Gerace L. 2006. Nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins (NETs) that are up-regulated during myogenesis. BMC Cell Biol 7: 38. 10.1186/1471-2121-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Luperchio TR, Wong X, Doan EB, Byrd AT, Roy Choudhury K, Reddy KL, Krangel MS. 2018a. A lamina-associated domain border governs nuclear lamina interactions, transcription, and recombination of the Tcrb locus. Cell Rep 25: 1729–1740.e6. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Brinkman EK, Adam SA, Goldman R, van Steensel B, Ma J, Belmont AS. 2018b. Mapping 3D genome organization relative to nuclear compartments using TSA-Seq as a cytological ruler. J Cell Biol 217: 4025–4048. 10.1083/jcb.201807108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier C, Jung HJ, Nobumori C, Chang S, Tu Y, Barnes RH II, Yoshinaga Y, de Jong PJ, Vergnes L, Reue K, et al. 2011. Deficiencies in lamin B1 and lamin B2 cause neurodevelopmental defects and distinct nuclear shape abnormalities in neurons. Mol Biol Cell 22: 4683–4693. 10.1091/mbc.e11-06-0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Cremer C. 2001. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat Rev Genet 2: 292–301. 10.1038/35066075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Cremer M. 2010. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a003889. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PM, Ramachandran K, vanWert J, Singal R. 2004. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. BioTechniques 37: 961–969. 10.2144/04376RV01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoy E, Puttaraju M, Jailwala P, Kasoji M, Cam M, Misteli T. 2017. Identification of novel RNA isoforms of LMNA. Nucleus 8: 573–582. 10.1080/19491034.2017.1348449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Gotzmann J, Stockinger A, Harris CA, Talle MA, Siekierka JJ, Foisner R. 1998. Detergent-salt resistance of LAP2α in interphase nuclei and phosphorylation-dependent association with chromosomes early in nuclear assembly implies functions in nuclear structure dynamics. EMBO J 17: 4887–4902. 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Gajewski A, Korbei B, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Haraguchi T, Furukawa K, Ellenberg J, Foisner R. 2004. LAP2α and BAF transiently localize to telomeres and specific regions on chromatin during nuclear assembly. J Cell Sci 117: 6117–6128. 10.1242/jcs.01529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Pfleghaar K, Sengupta K, Shimi T, Shumaker DK, Solimando L, Goldman RD. 2008. Nuclear lamins: major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev 22: 832–853. 10.1101/gad.1652708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Adam SA, Taimen P, Shimi T, Goldman RD. 2010. Nuclear lamins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a000547. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. 2002. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295: 1306–1311. 10.1126/science.1067799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Las Heras JI, Meinke P, Batrakou DG, Srsen V, Zuleger N, Kerr AR, Schirmer EC. 2013. Tissue specificity in the nuclear envelope supports its functional complexity. Nucleus 4: 460–477. 10.4161/nucl.26872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Las Heras JI, Zuleger N, Batrakou DG, Czapiewski R, Kerr ARW, Schirmer EC. 2017. Tissue-specific NETs alter genome organization and regulation even in a heterologous system. Nucleus 8: 81–97. 10.1080/19491034.2016.1261230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmerle J, Koch AJ, Holaska JM. 2012. The nuclear envelope protein emerin binds directly to histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and activates HDAC3 activity. J Biol Chem 287: 22080. 10.1074/jbc.M111.325308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dialynas G, Speese S, Budnik V, Geyer PK, Wallrath LL. 2010. The role of Drosophila lamin C in muscle function and gene expression. Development 137: 3067–3077. 10.1242/dev.048231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. 2012. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485: 376–380. 10.1038/nature11082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner D, Vlcek S, Foeger N, Gajewski A, Makolm C, Gotzmann J, Hutchison CJ, Foisner R. 2006. Lamina-associated polypeptide 2α regulates cell cycle progression and differentiation via the retinoblastoma-E2F pathway. J Cell Biol 173: 83–93. 10.1083/jcb.200511149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, Zhao TY, Common JE, Lunny D, Lane EB, Lee SJ, Vardy LA, Stewart CL, et al. 2013. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol 200: 605–617. 10.1083/jcb.201206121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlevy KL, Medvedeva V, Wilson JE, Hoque M, Pellegrin T, Maynard A, Kremp MM, Wasserman JS, Poleshko A, Katz RA. 2020. The PRR14 heterochromatin tether encodes modular domains that mediate and regulate nuclear lamina targeting. J Cell Sci 133: jcs240416. 10.1242/jcs.240416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong NT, Morris GE, Lam LT, Zhang Q, Sewry CA, Shanahan CM, Holt I. 2014. Nesprins: tissue-specific expression of epsilon and other short isoforms. PLoS ONE 9: e94380. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg J. 2013. Dynamics of nuclear envelope proteins during the cell cycle in mammalian cells. Landes Bioscience, Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Falk M, Feodorova Y, Naumova N, Imakaev M, Lajoie BR, Leonhardt H, Joffe B, Dekker J, Fudenberg G, Solovei I, et al. 2019. Heterochromatin drives compartmentalization of inverted and conventional nuclei. Nature 570: 395–399. 10.1038/s41586-019-1275-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, Ylstra B, Chubb JR, Bickmore WA. 2008. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet 4: e1000039. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foisner R. 2003. Cell cycle dynamics of the nuclear envelope. ScientificWorldJournal 3: 1–20. 10.1100/tsw.2003.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J, Ferrai C, Chiariello AM, Schueler M, Rito T, Laudanno G, Barbieri M, Moore BL, Kraemer DCA, Aitken S, et al. 2015. Hierarchical folding and reorganization of chromosomes are linked to transcriptional changes in cellular differentiation. Mol Syst Biol 11: 852. 10.15252/msb.20156492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K. 1999. LAP2 binding protein 1 (L2BP1/BAF) is a candidate mediator of LAP2-chromatin interaction. J Cell Sci 112: 2485–2492. 10.1242/jcs.112.15.2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Hotta Y. 1993. cDNA cloning of a germ cell specific lamin B3 from mouse spermatocytes and analysis of its function by ectopic expression in somatic cells. EMBO J 12: 97–106. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05635.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Inagaki H, Hotta Y. 1994. Identification and cloning of an mRNA coding for a germ cell-specific A-type lamin in mice. Exp Cell Res 212: 426–430. 10.1006/excr.1994.1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa T, Rochman M, Taher L, Dimitriadis EK, Nagashima K, Anderson S, Bustin M. 2015. Chromatin decompaction by the nucleosomal binding protein HMGN5 impairs nuclear sturdiness. Nat Commun 6: 6138. 10.1038/ncomms7138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgatos SD, Pyrpasopoulou A, Theodoropoulos PA. 1997. Nuclear envelope breakdown in mammalian cells involves stepwise lamina disassembly and microtubule-drive deformation of the nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci 110: 2129–2140. 10.1242/jcs.110.17.2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Blobel G. 1980. The nuclear envelope lamina is reversibly depolymerized during mitosis. Cell 19: 277–287. 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90409-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Foisner R. 1994. Integral membrane proteins and dynamic organization of the nuclear envelope. Trends Cell Biol 4: 127–131. 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90067-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Huber MD. 2012. Nuclear lamina at the crossroads of the cytoplasm and nucleus. J Struct Biol 177: 24–31. 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesson K, Rescheneder P, Skoruppa MP, von Haeseler A, Dechat T, Foisner R. 2016. A-type lamins bind both hetero- and euchromatin, the latter being regulated by lamina-associated polypeptide 2α. Genome Res 26: 462–473. 10.1101/gr.196220.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs-Seymour I, Markiewicz E, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Hutchison CJ. 2015. Lamin A/C-dependent interaction with 53BP1 promotes cellular responses to DNA damage. Aging Cell 14: 162–169. 10.1111/acel.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibcus JH, Samejima K, Goloborodko A, Samejima I, Naumova N, Nuebler J, Kanemaki MT, Xie L, Paulson JR, Earnshaw WC, et al. 2018. A pathway for mitotic chromosome formation. Science 359: eaao6135. 10.1126/science.aao6135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieffers C, Krohne G. 1991. In vitro reconstitution of recombinant lamin A and a lamin A mutant lacking the carboxy-terminal tail. Eur J Cell Biol 55: 191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Cruz RD, Dahl KN, Darling EM. 2018. The emerging role of lamin C as an important LMNA isoform in mechanophenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol 6: 151. 10.3389/fcell.2018.00151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Gasser SM. 2016. Mechanism of chromatin segregation to the nuclear periphery in C. elegans embryos. Worm 5: e1190900. 10.1080/21624054.2016.1190900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Towbin BD, Kalck V, Cabianca DS, Gaidatzis D, Hauer MH, Geng L, Wang L, Yang T, Wang X, et al. 2015. Perinuclear anchoring of H3K9-methylated chromatin stabilizes induced cell fate in C. elegans embryos. Cell 163: 1333–1347. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil F, Moorman C, van Steensel B. 2006. DamID: mapping of in vivo protein-genome interactions using tethered DNA adenine methyltransferase. Methods Enzymol 410: 342–359. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)10016-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Foisner R. 2015. Lamins: nuclear intermediate filament proteins with fundamental functions in nuclear mechanics and genome regulation. Annu Rev Biochem 84: 131–164. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Medalia O. 2015. Lamins: the structure and protein complexes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 32: 7–12. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, Eussen BH, de Klein A, Wessels L, de Laat W, et al. 2008. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature 453: 948–951. 10.1038/nature06947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Swift J, Irianto J, Shin J-W, Spinler KR, Athirasala A, Diegmiller R, Dingal PCDP, Ivanovska IL, Discher DE. 2014. Nuclear lamin stiffness is a barrier to 3D migration, but softness can limit survival. J Cell Biol 204: 669–682. 10.1083/jcb.201308029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi T, Koujin T, Segura-Totten M, Lee KK, Matsuoka Y, Yoneda Y, Wilson KL, Hiraoka Y. 2001. BAF is required for emerin assembly into the reforming nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci 114: 4575–4585. 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harr JC, Luperchio TR, Wong X, Cohen E, Wheelan SJ, Reddy KL. 2015. Directed targeting of chromatin to the nuclear lamina is mediated by chromatin state and A-type lamins. J Cell Biol 208: 33–52. 10.1083/jcb.201405110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harr JC, Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Gasser SM. 2016. Histones and histone modifications in perinuclear chromatin anchoring: from yeast to man. EMBO Rep 17: 139–155. 10.15252/embr.201541809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harr JC, Schmid CD, Muñoz-Jiménez C, Romero-Bueno R, Kalck V, Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Hauer MH, Padeken J, Askjaer P, Mattout A, et al. 2020. Loss of an H3K9me anchor rescues laminopathy-linked changes in nuclear organization and muscle function in an Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy model. Genes Dev 34: 560–579. 10.1101/gad.332213.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CA, Andryuk PJ, Cline S, Chan HK, Natarajan A, Siekierka JJ, Goldstein G. 1994. Three distinct human thymopoietins are derived from alternatively spliced mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 6283–6287. 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitlinger E, Peter M, Lustig A, Villiger W, Nigg EA, Aebi U. 1992. The role of the head and tail domain in lamin structure and assembly: analysis of bacterially expressed chicken lamin A and truncated B2 lamins. J Struct Biol 108: 74–91. 10.1016/1047-8477(92)90009-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Aebi U. 2004. Intermediate filaments: molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular scaffolds. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 749–789. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano Y, Hizume K, Kimura H, Takeyasu K, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. 2012. Lamin B receptor recognizes specific modifications of histone H4 in heterochromatin formation. J Biol Chem 287: 42654–42663. 10.1074/jbc.M112.397950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY, Lammerding J. 2012. Lamins at a glance. J Cell Sci 125: 2087–2093. 10.1242/jcs.087288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höger TH, Grund C, Franke WW, Krohne G. 1991. Immunolocalization of lamins in the thick nuclear lamina of human synovial cells. Eur J Cell Biol 54: 150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmer L, Worman HJ. 2001. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: functions and targeting. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1741–1747. 10.1007/PL00000813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K, Secchia S, Almakki O, Lieb JD, Moskowitz IP. 2020. Phosphorylated lamin A/C in the nuclear interior binds active enhancers associated with abnormal transcription in progeria. Dev Cell 52: 699–713.e11. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Vaughan OA, Hutchison CJ, Gilbert DM. 2000. Head and/or CaaX domain deletions of lamin proteins disrupt preformed lamin A and C but not lamin B structure in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 11: 4323–4337. 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn D, Schramm S, Schnölzer M, Heilmann CJ, de Koster CG, Schütz W, Benavente R, Alsheimer M. 2012. A truncated lamin A in the Lmna–/– mouse line: implications for the understanding of laminopathies. Nucleus 3: 463–474. 10.4161/nucl.21676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HJ, Coffinier C, Choe Y, Beigneux AP, Davies BS, Yang SH, Barnes RH II, Hong J, Sun T, Pleasure SJ, et al. 2012. Regulation of prelamin A but not lamin C by miR-9, a brain-specific microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: E423–E431. 10.1073/pnas.1111780109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempfer R, Pombo A. 2020. Methods for mapping 3D chromosome architecture. Nat Rev Genet 21: 207–226. 10.1038/s41576-019-0195-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Wirtz D. 2015. Cytoskeletal tension induces the polarized architecture of the nucleus. Biomaterials 48: 161–172. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]