Abstract

Background

The understanding of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) has accelerated over the last decade, producing a number of practice-changing developments. Diagnosis is challenging. No diagnostic criteria exist, no single finding is diagnostic, and other causes of back pain may act as confounders.

Aim

To update and expand the 2014 consensus statement on the investigation and management of non‐radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA).

Methods

We created search questions based on our previous statements and four new topics then searched the MEDLINE and Cochrane databases. We assessed relevant publications by full-text review and rated their level of evidence using the GRADE system. We compiled a GRADE evidence summary then produced and voted on consensus statements.

Results

We identified 5145 relevant publications, full-text reviewed 504, and included 176 in the evidence summary. We developed and voted on 22 consensus statements. All had high agreement. Diagnosis of nr-axSpA should be made by experienced clinicians, considering clinical features of spondyloarthritis, blood tests, and imaging. History and examination should also assess alternative causes of back pain and related conditions including non-specific back pain and fibromyalgia. Initial investigations should include CRP, HLA-B27, and AP pelvic radiography. Further imaging by T1 and STIR MRI of the sacroiliac joints is useful if radiography does not show definite changes. MRI provides moderate-to-high sensitivity and high specificity for nr-axSpA. Acute signs of sacroiliitis on MRI are not specific and have been observed in the absence of spondyloarthritis. Initial management should involve NSAIDs and a regular exercise program, while TNF and IL-17 inhibitors can be used for high disease activity unresponsive to these interventions. Goals of treatment include improving the frequent impairment of social and occupational function that occurs in nr-axSpA.

Conclusions

We provide 22 evidence-based consensus statements to provide practical guidance in the assessment and management of nr-axSpA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-021-00416-7.

Keywords: Consensus statements, Diagnosis, MRI, Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, TNF inhibitor

Key Summary Points

| Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis is closely related to ankylosing spondylitis, but has no definite sacroiliac changes on plain radiography. |

| Diagnosis requires consideration of symptoms, examination, HLA-B27, CRP, and imaging by a clinician experienced in this condition. |

| No single diagnostic feature or test is perfectly sensitive or specific. |

| Management should begin with NSAIDs and an exercise program and can be escalated to targeted therapy. |

Introduction

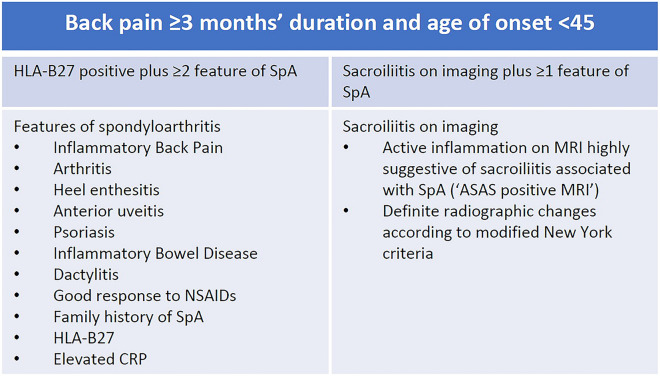

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is an inflammatory arthritis that predominantly affects the axial skeleton. Characteristic changes to the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) on plain radiography are seen in ankylosing spondylitis (AS), but not in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) [1]. For decades AS has been straightforward to identify using the modified New York criteria, which includes clinical features and definite radiographic changes. The classification criteria for axSpA developed by the SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) in 2009 includes other objective findings and has been widely used to identify nr-axSpA for clinical trials [2, 3]. To meet classification criteria, an individual with predominantly axial symptoms must have other possible causes of back pain excluded, and must have either HLA-B27 plus two other features of spondyloarthritis (SpA) or sacroiliitis on imaging plus one clinical feature of SpA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ASAS classification criteria for axSpA [1]

In clinical practice and trial cohorts, nr-axSpA is heterogeneous and often comorbid with other conditions, including other forms of SpA and non-specific back pain (NSBP). The complex presentation and lack of a diagnostic biomarker makes diagnosis and treatment of nr-axSpA challenging even for experienced clinicians.

Diagnosis is based on the expert opinion of a rheumatologist, with MRI imaging an important part of current classification criteria [4]. However, the sensitivity and specificity of MRI is lower than required for an independent diagnostic test, and caution needs to be exercised when interpreting MRI findings for diagnosis [5]. ASAS have also defined and validated an ‘ASAS-positive MRI’ to describe sacroiliitis highly suggestive of axSpA adequate for classification, however even this definition is undergoing modification as more information becomes available [6].

The construct of nr-axSpA has generated diverse opinions and controversy. As a disease entity, some authors have described it as part of the spectrum of axSpA, an early stage of AS, and as a different but overlapping entity to AS [7–10]. Confounding the concept that nr-axSpA is a pre-AS condition are reproducible differences between the two conditions. Non-radiographic axSpA has a higher proportion of females, a lower proportion of HLA-B27, and not all progress to AS. In observational studies, individuals with solely non-inflammatory conditions have been classified as nr-axSpA [11].

The diverse and complex descriptions and presentation of nr-axSpA encourage the development of practical guidelines to aid clinicians. The European League Against Rheumatism has published unified recommendations on axSpA in 2016, while the American College of Rheumatology published separate recommendations for AS and nr-axSpA in 2019 [12, 13]. To provide guiding principles for clinicians in our region, we published a set of nr-axSpA consensus statements in 2014 [14]. Here we update and expand these statements to include numerous practice-changing developments, including interpretation of investigations, the natural history and functional consequences of disease, use of biologic therapy, and other interventions.

Methods

We formed a panel of authors from our previous consensus statements and other interested parties. Our approach to updating our work was to update and expand our previous 2014 statements and to search around current topics of interest suggested by the panel. Author disclosures were declared before search questions were formulated. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

PICO style search questions were created for the 14 previous statements and four new topics of interest (Supplementary data S1–S2). The new questions ask what impact nr-axSpA has on function, what the predictors of function and quality of life are, what predicts response to treatment, and if one biologic class is superior to others for axial symptoms. To increase sensitivity, we used a pooled search strategy, using broad search terms for the new topics. The closely related topics of functional outcomes, predictors of function, quality of life, and work outcomes were each covered with a single set of search terms.

We searched the MEDLINE and Cochrane Library databases, excluding conference abstracts and studies of animals or minors. Relevant studies identified in reference lists were included, and publications identified by any question’s literature search could be progressed to another question’s full-text review. We searched for the disease state of axial spondyloarthritis, aiming only to use findings from AS cohorts if no high-quality, relevant papers examined nr-axSpA or mixed AS/nr-axSpA cohorts. Searches performed to update the previous statements were date limited from September 1, 2013 until November 1, 2020, and searches of new topics had no date limit. Search terms and search questions are listed in Supplementary data S1–S2.

Two authors (ST, TM) performed the searches, reviewed the title/abstract of each publication, and progressed relevant articles to full-text review. Included publications were assessed by the same two authors for publication quality and bias using the GRADE system [15]. For the GRADE population bias assessment, cohorts with < 25% nr-axSpA were penalized by two GRADE levels and those with 25–50% nr-axSpA one GRADE level (unless nr-axSpA participants were reported separately).

A GRADE style summary of evidence for each search question was presented to the panel at an online meeting. The recommendations were discussed using the GRADE framework, which considers risk/benefit, quality of evidence, confidence in patient values, and resource use.

Following the GRADE presentation, the panel was given the opportunity to modify the recommendations and review the GRADE summary. The panel voted anonymously on each of the finalized recommendations using an online survey. A scale of 0 (‘do not agree at all’) to 10 (‘fully agree’) was used with the predetermined requirement that any recommendation scoring less than seven would be redrafted and voted on again. The recommendations were forwarded to relevant stakeholders—two patient representatives and a rheumatology nurse practitioner for feedback.

Results

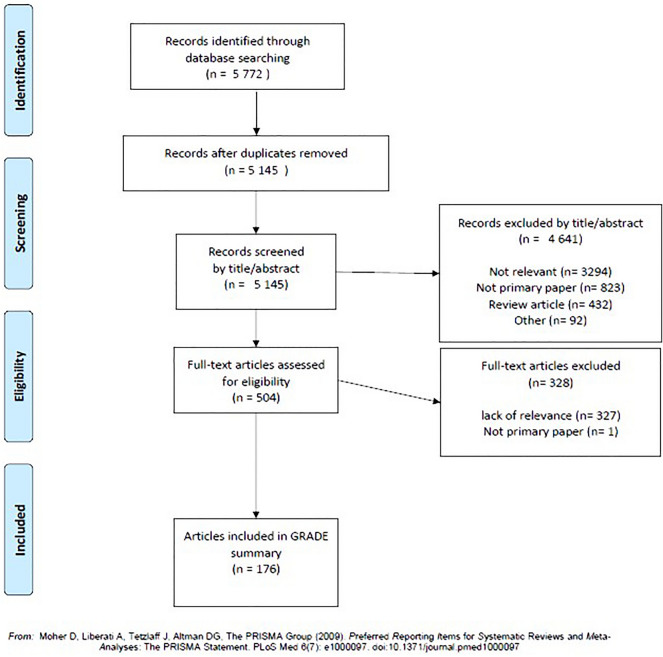

Searches of the MEDLINE and Cochrane Library databases identified 5772 records, of which 504 were assessed by full-text review, and 176 relevant articles included in the GRADE summary (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of literature search and full-text review

Aside from RCTs, many topics lacked high-quality evidence, most frequently due to the lack of nr-axSpA specific data. Evidence was often from observational studies or reported without standardization of metrics such as functional outcomes, abnormal CRP, or disease activity. Imaging studies were often well conducted but limited in size or had inconsistent results between cohorts. Exercise and physiotherapy related interventions had no standardized intervention or reproduced findings. We found only low quality evidence for use of NSAIDs, conventional DMARDs, and systemic or intra-articular corticosteroids.

Voting produced a high level of agreement for each recommendation (Table 1). Statements with perfect levels of agreement included those based on reproducible findings (e.g., sacroiliac bone marrow edema has been observed in individuals without axial spondyloarthritis, including healthy controls, athletes, and post-partum women) while statements with the lowest level of agreement tended to have very low levels of evidence or involve some risk (e.g., sacroiliac corticosteroid injections may have a limited role in the treatment of nr-axSpA).

Table 1.

Consensus statements

| Statement | GRADE level | GRADE strength | Level of agreement Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The patient’s views, preferences, and goals are central and care should be a partnership between the clinical team and the patient | Very low | Strong | 9.6 (0.5) |

| Patient education is a key part of the management of nr-axSpA | Low | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| A comprehensive history and physical examination should be carried out for the assessment of suspected nr-axSpA | Moderate | Strong | 10 (0) |

| CRP should be measured when considering the diagnosis of nr-axSpA | Low | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| HLA-B27 status should be determined when considering the diagnosis of nr-axSpA | Moderate | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| Plain pelvic radiographs should be obtained to evaluate back pain with features suggestive of spondyloarthritis | Moderate | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| Sacroiliac joint pathology observed on radiographs is not specific for sacroiliitis and should be interpreted within the clinical context | Moderate | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| A normal radiograph does not exclude nr-axSpA | High | Strong | 10 (0) |

| Computed tomography is not recommended for the investigation of suspected nr-axSpA | Moderate | Strong | 9.4 (0.8) |

| Sacroiliac joint MRI should be used in those with clinical suspicion of nr-axSpA. The recommended protocol is the combination of non-contrast T1 and STIR | Moderate | Strong | 10 (0) |

| Sacroiliac bone marrow edema is not unique to spondyloarthritis and should be interpreted in the clinical context | Moderate | Strong | 10 (0) |

| Sacroiliac bone marrow oedema has been observed in individuals without axial spondyloarthritis, including healthy controls, athletes and post-partum women | Moderate | Strong | 10 (0) |

| The components of the classification criteria have value in guiding a diagnosis of nr-axSpA, but should not be used as diagnostic criteria in individual patients | High | Strong | 9.7 (0.5) |

| Management plans should include long-term, regular exercise | Very low | Strong | 9.6 (0.5) |

| Physiotherapy may be useful in the management of nr-axSpA | Very low | Strong | 8.4 (1.7) |

| There is no role for DMARDs in the management of axial manifestations in nr-axSpA | Very low | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| Sulfasalazine can be considered for those with peripheral manifestations in nr-axSpA | Very low | Conditional | 9.1 (0.7) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are recommended as first-line pharmacological treatment for the management of nr-axSpA | Low | Strong | 9.9 (0.4) |

| TNF and IL-17 inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of nr-axSpA | High | Strong | 9.7 (0.5) |

| TNF inhibitor dose reductions are associated with an increase in risk of flares, while TNF inhibitor cessation has a significant risk of flare | High | Strong | 8.7 (1.3) |

| Sacroiliac corticosteroid injections may have a limited role in the treatment of nr-axSpA | Very low | Conditional | 8.3 (1.5) |

| Systemic corticosteroids have no definite role in the treatment of nr-axSpA | Very low | Conditional | 8.9 (1.1) |

No recommendation had an agreement score less than seven. No recommendations were made specifically mentioning observed effects of nr-axSpA on natural history, quality or life, social and occupational function, or predictors of response to treatment. Instead, we discuss the best evidence on these topics to summarize the knowledge base to inform the clinical decisions of our readers.

Stakeholder Feedback

The patient and nurse representatives described the statements as practical and thorough, covering relevant topics and not missing major areas of concern. They appreciated the patient-centric approach used throughout the statements.

Decision Making

The patient’s views, preferences, and goals are central and care should be a partnership between the clinical team and the patient.

Patient education is a key part of the management of nr-axSpA.

We regard a patient-centric approach including informed decision making to be central to shared decision making. We found no directly relevant literature for these recommendations, only evidence detailing diverse preferences and frequent discordance between patient and physician global assessment. A survey of axSpA reported a wide variety of medication administration route preferences where only 50% preferred tablets [16]. A single study comparing patient global assessment and physician global assessment found these metrics to be significantly discordant at 48% of encounters [17].

The importance of patient education has been highlighted by a French axSpA cohort where strong beliefs were common and influential, including numerous that might obstruct management, such as the belief that physical activity can trigger flares or increase disease activity [18]. This belief was associated with higher psychological distress and lower general education levels. In another cohort of predominantly nr-axSpA, negative illness perceptions were associated with quality of life, back pain, and work productivity loss [19]. The follow-up study of this cohort found coping strategies and illness perceptions unchanged over 2 years [20]. Negative beliefs included the notions that the disease has major consequences on one’s life, the disease causes distress, and that the disease is from chance or bad luck. This link between illness-related beliefs, general literacy, and disease outcomes implies a critical role of health literacy in axSpA management.

While these observational studies reinforce the potential consequences of incorrect disease-related beliefs, we found no high-quality evidence that education promotes improvement, although very little has been published. Only one study has assessed education as an intervention in axSpA, providing a 1-day nurse-led education session followed by a self-assessment program [21]. The primary outcome of coping was unchanged, BASDAI slightly improved, and the number of participants performing home-based exercises after 1 year almost doubled, suggesting this program may provide some benefit with little risk of harm.

Other practical reasons to recommend disease education include improved medication compliance and awareness of adverse reactions, reporting of extra-articular manifestations, and improved attendance at appointments. From an ethical perspective, patient education improves shared decision making and autonomy. The desire for patient education is present—a survey of various rheumatic diseases, including axSpA, found the majority of patients were interested in more education as one-on-one from clinicians, online, or in group sessions [22]. In other forms of rheumatic disease, it is recognized that disease-related education is best provided using an individualized needs-based framework from specialist nurses, and can improve self-efficacy, self-management, adherence, coping skills, and physical and psychological status [23, 24].

Clinical Assessment

A comprehensive history and physical examination should be carried out for the assessment of suspected nr-axSpA.

Diagnosis of nr-axSpA requires a thorough assessment to identify features of axSpA, differential diagnoses, and common comorbidities such as NSBP and fibromyalgia.

A history of inflammatory back pain (IBP) is the cardinal feature of axSpA. IBP has high sensitivity (74%) but low specificity (40%) for nr-axSpA, similar to values observed in axSpA (94 and 25%, respectively) [25, 26]. Typical IBP presents with numerous features not seen in non-specific or mechanical back pain, such as no relief from rest, pain overnight, and early morning pain and stiffness that improves with movement or exercise [1]. A mixture of inflammatory and non-specific symptoms are often present.

A family history of SpA increases the likelihood of nr-axSpA, with low sensitivity and high specificity for axSpA [26, 27]. However, in a single cohort of 80% nr-axSpA, once the contribution of HLA-B27 was removed, no value was found in a positive family history of SpA [28].

Other clinical features of SpA contain predictive value for nr-axSpA, including heel enthesitis, psoriasis, uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, peripheral inflammatory arthritis, and a good response to NSAIDs [27]. The combination of a good response to NSAIDs, early morning stiffness > 30 min, and elevated CRP has high sensitivity (91%) and moderate specificity (67%) [29]. The examination finding with the most evidence is the FABER sacroiliac provocation test, which demonstrated moderate sensitivity (71%) and specificity (75%) for MRI sacroiliitis in a small cohort [30].

History and examination of suspected nr-axSpA should include a consideration of fibromyalgia, which can present as comorbidity, consequence, or mimic of axSpA. Prominent features of central sensitization pain can complicate the diagnostic process, especially if more non-inflammatory than inflammatory features are present. Comorbid fibromyalgia is common in nr-axSpA, identified in 23% of males, 21% of females, and in 22–38% of axSpA [31–34]. Similarly, axSpA has been identified in 10% of a fibromyalgia cohort, where most of those meeting ASAS classification criteria had an ASAS-positive MRI [35].

Initial Investigations

CRP should be measured when considering the diagnosis of nr-axSpA.

Elevated CRP is a recognized feature of SpA that is present in 36–58% of nr-axSpA [36–38]. AS and AS-containing axSpA cohorts also often have elevated CRP, probably more often and at a higher level than nr-axSpA [36, 38–41].

The pitfall of finding a normal CRP in highly suspected nr-axSpA can be partly addressed by repeated testing. In the placebo arm of a nr-axSpA RCT, 50% of subjects with a normal CRP at baseline developed an elevated CRP within 16 weeks over a mean of seven tests [42].

HLA-B27 status should be determined when considering the diagnosis of nr-axSpA.

The presence of HLA-B27 increases the likelihood of nr-axSpA in suspected individuals (OR 5.6–5.9) [27, 43]. For axSpA, its predictive value is even higher (LR 17) with moderate-to-high sensitivity (41–66%) and positive predictive value (68%) and high specificity (80–96%) [26, 44, 45]. There is no nr-axSpA-specific data reporting the predictive value of HLA-B27 for extra-articular manifestations of spondyloarthritis, however, HLA-B27 in axSpA is associated with twice the risk of uveitis and half the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or psoriasis [46].

Presence of HLA-B27 and an ASAS-positive MRI is highly suggestive of nr-axSpA, with specificity reported at 99%, and only 2% with neither present having axSpA [26, 43]. These findings reinforce that exclusion of axSpA should be strongly influenced by the negative predictive value of HLA-B27 (78%) and sacroiliitis on imaging (84%) [26].

Plain pelvic radiographs should be obtained to evaluate back pain with features suggestive of spondyloarthritis.

Sacroiliac joint pathology observed on radiographs is not specific for sacroiliitis and should be interpreted within the clinical context.

A normal radiograph does not exclude nr-axSpA.

Non-radiographic axSpA requires features of axSpA without definite sacroiliac changes on plain radiographs [1]. Obtaining plain radiographs before MRI is an important step for rational use of resources, prognostic value and to inform an approach to treatment.

Antero-posterior (AP) pelvic views are sufficient for sacroiliac joint assessment and also assess hip arthritis, which is common in AxSpA [47]. Sacroiliac joint views uncommonly add diagnostic information so are not recommended. AP pelvic radiographs are often sufficient for diagnosis in suspected axSpA, so should be performed before sacroiliac MRI. They have moderate sensitivity (40–70%) and high specificity (86–95%) for axSpA compared to low-dose CT but low sensitivity (20–50%), and high specificity (80–99%) compared to expert diagnosis [48–51].

Plain radiography of the spine is a useful investigation when spinal fracture is suspected. Low bone density is an established consequence of AS, and has been reported in nr-axSpA but the vertebral fracture rate in an early AxSpA cohort was low [52–54].

In a cohort of suspected axSpA, diagnosis was made after history, examination, and blood tests in 62% [55]. Imaging with radiography and MRI changed the diagnosis in 14% of remaining subjects, of which 42% were diagnosed by plain radiography. Similar rates of definite radiographic sacroiliac changes in 38–40% have been reported in other groups of suspected axSpA [36, 56].

Radiography must be considered in conjunction with other clinical features of back pain and axSpA. It cannot be used as a sole test for diagnosis of axSpA as the characteristic features of erosions, sclerosis, and joint space changes, and even ‘radiographic sacroiliitis’ by modified New York criteria have been identified in subjects without inflammatory axial disease [50]. Inflammatory arthritis most typical of another form of spondyloarthritis often causes ‘radiographic sacroiliitis’, for example in 16–33% of psoriatic arthritis without a significant history of back pain [57, 58].

Rates of progression from nr-axSpA to AS over years have been reported, but their estimates vary greatly. One study found no net progression over 3.9 years as an equal number reverted from AS to nr-axSpA, attributed to inter-reader variability [59]. The ASAS and DESIR cohorts reported net progression of 19.2% and 6.3% over a mean 4.6 years [60]. Over longer periods, 17% progression at 10 years and 26% at 15 years were observed in a US cohort, with a median time to progression of 5.9 years and no reported reversion rate [11].

Computed tomography is not recommended for the investigation of suspected nr-axSpA.

Computed tomography (CT) provides excellent resolution of structural bony lesions, but is unable to detect acute inflammation and has no diagnostic criteria for axSpA, making it inferior to MRI for diagnosis. CT is highly useful for investigation of suspected pelvic fracture.

A direct comparison of low-dose CT and T1 MRI to expert diagnosed nr-axSpA found similar sensitivity for structural lesions (44% and 46%) but a higher specificity of CT than T1 MRI (96% and 69%) [61]. Bone marrow edema (BMO) on fat-suppressed MRI was highly sensitive (88%) and moderately specific (67%) favoring the use of MRI over CT.

Comparison of CT to T1 MRI in an axSpA cohort with 36% nr-axSpA demonstrated high agreement for erosions and joint space changes (kappa 0.74 and 0.8) but not for sclerosis (kappa 0.32) [62]. Sensitivity of T1 MRI for sclerosis was low (30%), but the same study reported moderate-to-high sensitivity of plain radiographs for sclerosis (70%). Thus, the combination of pelvic radiography plus MRI provides high sensitivity and moderate-to-high specificity for a global impression of axSpA, while the remaining lesions detected by CT lack a validated framework for diagnosing axSpA.

MRI Use and Interpretation

Sacroiliac joint MRI should be used in those with clinical suspicion of nr-axSpA. The recommended protocol is the combination of non-contrast T1 and STIR.

Signs of sacroiliac joint inflammation are often present in nr-axSpA when suitable MRI protocols are used. In the context of suspected nr-axSpA, we recommend STIR to detect acute sacroiliac inflammation (represented as BMO), and T1 to visualize chronic structural changes, which add to the global impression.

MRI-positive sacroiliitis is common in cohorts of IBP and nr-axSpA, where an ASAS-positive MRI involving highly suggestive BMO is present in 41–48% of subjects [36, 49, 56]. MRI-positive sacroiliitis is highly specific, and both sensitivity and specificity improve when clinical features are added [27]. Presence of ‘Deep BMO’ (extending > 1 cm from the SIJ articular cortex) or BMO plus one structural lesion increases specificity [5].

Detection of BMO is therefore critical for diagnosis, and is achieved with fat-nulling MRI sequences. STIR has been preferred over T2 fat-suppressed sequences due to more homogeneous suppression and has been repeatedly validated for this purpose, while DWI and T1 with gadolinium offer no additional diagnostic value over STIR [1, 63–66]. Assessment of the ligamentous compartment of the SIJ for acute inflammation very rarely adds diagnostic information, changing the diagnosis in 0–0.6% in two nr-axSpA cohorts [67].

AxSpA can cause characteristic changes in lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spinal MRI, but these features have insufficient specificity for diagnostic use and no method of interpretation has been validated. Vertebral BMO is common and has been observed concurrently with SIJ BMO in half of scans in nr-axSpA [68]. Whole-spine MRI increases sensitivity for nr-axSpA modestly when the SIJ have no BMO, but one-third of these spinal MRIs are false-positive, a rate two–threefold higher than SIJ MRI alone [69]. Due to these challenges, we have only made a recommendation regarding interpretation of sacroiliac MRI and await validation of diagnostic criteria for spinal lesions.

The interpretation of structural sacroiliac joint lesions also presents a challenge when diagnosing axSpA, with variable interpretation among rheumatologists and radiologists [5]. One high-quality, well-conducted study was performed to assess frequency of structural changes in nr-axSpA [70]. The chronic structural changes of backfill and fat metaplasia were rare in subjects without BMO, occurring in 0–1.8%, and were far more common when BMO was present. This and a previous study found that erosions are uncommon without BMO in nr-axSpA (7.5–11%), and rarely occur without BMO in NSBP and healthy controls (1.3–3.8%) [70, 71]. The presence of multiple structural lesions is also highly specific (> 90%) but uncommon, and so does not significantly increase sensitivity [5, 71]. The presence of one erosion plus at least one BMO lesion achieves moderate-to-high sensitivity and specificity which is an improvement but still inadequate for diagnosis without considering clinical features.

Currently, no widely used scoring system combines BMO and structural lesions as a diagnostic tool, leaving structural lesions a component of global SIJ assessment for expert readers. The CANDEN MRI spine scoring system is a comprehensive system that permits a detailed description of the involvement of different spinal structures, various topographic parts of the vertebral bodies, the facet joints, the spinous processes, the transverse processes, the ribs, and soft tissue [72]. By covering various inflammatory and structural lesion types, the CANDEN MRI spine scoring system may help identify subgroups of patients and different disease trajectories. The ASAS MRI group has also recently proposed the definition for a definite structural lesion typical of AxSpA as ≥ 3 sacroiliac joint quadrants with erosion, or ≥ 5 quadrants with fat lesions, or structural lesions at the same location on consecutive slices, or a deep fat lesion [73].

Repeat MRI After a Negative Scan

Repeat MRI scans looking for sacroiliac joint changes has a role in the diagnosis of nr-axSpA, although the yield is low, especially if HLA-B27 is negative. In suspected nr-axSpA, repeating sacroiliac joint MRI yields an ASAS-positive scan in 2.5–15% of cases, with a similar rate of 9.3% in diagnosed nr-axSpA [74–77]. Two studies report that BMO on repeat MRI is more common in males and far more likely if HLA-B27 is positive [75, 78]. Both studies report that if HLA-B27 is negative, the likelihood of an initial ASAS-negative MRI changing to positive on follow-up is < 5%.

Sacroiliac bone marrow edema is not unique to spondyloarthritis and should be interpreted in the clinical context.

Sacroiliac bone marrow edema has been observed in individuals without axial spondyloarthritis, including healthy controls, athletes, and post-partum women.

MRI signs of acute and chronic sacroiliitis are known to occur in the absence of nr-axSpA so should not be used in isolation for diagnosis. False-positive ‘sacroiliitis’ is not uncommon even when using the validated cutoff of an ASAS-positive MRI, developed to represent a significant amount of BMO ‘highly suggestive’ of sacroiliitis from axSpA [1]. It has been observed in 23% of healthy controls, 23% of military recruits, 30–41% of runners and professional ice hockey players, and 40–64% of postpartum women [79–83]. The most common site of false-positive sacroiliac BMO is the posterior lower ilium [79].

Structural lesions of the SIJ are also seen in the absence of SpA, with reports of fatty lesions occurring in 4–10% of controls, and at least one erosion in 9–10% of post-partum women and 9.5% of runners and ice hockey players [79, 80, 84].

Diagnostic Considerations

The components of the classification criteria have value in guiding a diagnosis of nr-axSpA, but should not be used as diagnostic criteria in individual patients.

Classification criteria exist to select a patient population for clinical research, assume the pre-test population has an existing diagnosis, and that relevant differential diagnoses have been excluded [7]. When applied to trial populations in this manner, the ASAS classification criteria for axSpA show moderate sensitivity and moderate specificity compared to the gold standard of expert diagnosis [27, 36, 37, 44, 56, 85]. Long-term follow-up has confirmed that classification of axSpA is reproducible and persists over numerous years [27, 36, 56, 86]. Classification criteria should not be applied as a diagnostic list. They have not been validated for this purpose and will fail to completely rule in or rule out the diagnosis without assessment from an experienced clinician [8]. Classification criteria are, however, a valuable list of features that aid global assessment by experienced clinicians who can assess other possible causes of symptoms, comorbidities, and sequelae.

The specialist’s challenge is to apply recognized disease concepts to replicate the gold standard of expert diagnosis. Our recommendations describe many practical steps that can be taken when the diagnosis is not clear, such as repeating MRI and CRP, and starting low-risk treatments including NSAIDs, exercise, and physiotherapy.

Exercise and Physiotherapy

Management plans should include long-term, regular exercise.

An exercise program involving cardiovascular exertion and range of movement back exercises is a low-risk intervention that will help to improve musculoskeletal heath and obesity. We only found very low quality evidence on these interventions, as trials were only in axSpA, lack a standardized intervention, and have not been reproduced.

A single group of authors in Norway have investigated the benefit of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) for management of axSpA (30% nr-axSpA, 70% AS). Their RCT of HIIT and resistance training, three times per week for 3 months, compared to no change in exercise, saw small improvements in outcome measures (ASDAS, BASFI, BASMI) and waist circumference, and a modest improvement in the symptom-based disease activity measure BASDAI of 1.2 points [87]. Fatigue, vitality, and general health improved at the end of the intervention period and reduced to no improvement after 12 months [88]. A Spanish RCT of pool-based exercise therapy for axSpA also found small improvements in quality of life, BASFI, BASDAI, neck, back and hip pain, and morning stiffness [89].

Physiotherapy may be useful in the management of nr-axSpA.

Physiotherapy (physical therapy) is a low-risk intervention that addresses multiple causes of back pain, including NSBP, which can occur secondary to, or as a mimic of, nr-axSpA. Evidence for physiotherapy in nr-axSpA is very limited, and was rated very low quality using the GRADE method. We did not identify any standardized program or reproduced results in axSpA.

An observational cohort of 50% nr-axSpA recorded slight improvement in disease activity and mobility outcomes after 6 months of core and spinal exercises and brief exertion compared to baseline, but not compared to controls [90]. A trial of non-controlled physiotherapy in the DESIR cohort of axSpA found a small improvement in BASFI but not other outcome measures [91].

A 2019 Cochrane review of exercise and physiotherapy for AS found that it probably slightly improves function and patient-reported disease activity and may reduce pain, with no evidence it helps fatigue [92].

Use of Conventional Medication/Pharmacotherapy

There is no role for conventional synthetic DMARDs in the management of axial manifestations in nr-axSpA.

There is no evidence base to support the use of conventional synthetic DMARDs to treat axial symptoms in axSpA. A placebo-controlled RCT of sulfasalazine for 230 people with AS found no benefit for axial symptoms, while a small RCT of 67 subjects with AS reported small but significant improvements in outcomes (ASDAS, BASDAI, BASMI) [93, 94]. Multiple observational axSpA and AS studies have not found benefit for axial symptoms [95–97]. Observational data from the control arm of an etanercept AS trial reported the sulfasalazine arm achieving ASAS40 33% and ASAS20 52%, but little improvement in objective measures [98]. As this result occurred in an AS trial with no comparison to placebo to remove confounding disease activity fluctuation, this is very low quality evidence. A 2014 Cochrane review found no significant benefit of SSZ for axial symptoms in AS [99].

A very low quality study of axSpA reported superior TNF inhibitor retention in people taking conventional DMARDs, although the higher rate of peripheral arthritis in the DMARD group confounds this result [100].

Sulfasalazine can be considered for those with peripheral manifestations in nr-axSpA.

Conventional DMARDs are widely used for peripheral arthritis in nr-axSpA and are presumed to have efficacy based on their use in other forms of SpA. We found no interventional study of nr-axSpA that reports peripheral arthritis as an outcome. An AS RCT reported improvements in patient and physician global assessment on sulfasalazine, and an observational study reported an improvement in peripheral pain score [97, 98]. Neither study found a clinically significant improvement in swollen or tender joint count or CRP. Use of sulfasalazine to treat peripheral arthritis in spondyloarthritis is common but lacks high-quality evidence [101, 102].

We leave our 2014 recommendation unchanged as a low-risk and low-cost initial treatment option for peripheral arthritis.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are recommended as first-line pharmacological treatment for the management of nr-axSpA.

NSAID use is based on efficacy seen in axSpA, as there is no nr-axSpA specific evidence. We recommend NSAIDs for back pain in nr-axSpA as they can help inflammatory and non-inflammatory back pain and improve participation in an exercise program.

Uncontrolled studies of axSpA found clinically significant improvement from NSAIDs at the maximum tolerated dose, attaining ASAS40 in 30–57% and BASDAI50 in 29%, which compares favorably to a previously reported placebo response of 12.5% in axSpA [103–106]. A Cochrane review of NSAIDs for AS found high-to-moderate quality evidence of benefit for axial symptoms [107].

Sacroiliac corticosteroid injections may have a limited role in the treatment of nr-axSpA.

Systemic corticosteroids have no definite role in the treatment of nr-axSpA.

We found no trials that investigate the use of corticosteroids in nr-axSpA. Sacroiliac corticosteroid injections are an established practice in axSpA with little evidence while systemic corticosteroids have inconsistent results.

A single study reports response to corticosteroid injection of the sacroiliac joints for MRI sacroiliitis (52% AS, 48% nr-axSpA) [108]. VAS pain scores halved, which was twice the improvement seen in the active control group of peri-articular injection.

Two small double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs have examined treating axSpA with high-dose oral prednisone. One describes the inconsistent finding of an improvement in BASDAI50 but not ASAS20 or ASAS40 in 32 subjects taking 60 mg prednisone weaned over 18 weeks [109]. The second reports mild-to-moderate improvement in BASDAI (2.4 points) and ASDAS (1.6 points) from 50 mg but not 20 mg prednisone after 2 weeks [110]. A small improvement was seen following intramuscular triamcinolone, where ASDAS fell by 1.4 points in an open, uncontrolled trial of AS and PsA with axial disease [111].

Systemic corticosteroids do not have consistent evidence of benefit. Safer and more efficacious alternatives are available, leaving no clear role in the treatment of axial symptoms. Sacroiliac corticosteroid injections can possibly be considered for acute management of axSpA associated sacroiliitis, however their duration of action is limited.

Use of bDMARDs

TNF and IL-17 inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of nr-axSpA.

The efficacy of TNF inhibitors for the axial symptoms of nr-axSpA has been demonstrated by four large placebo-controlled RCTs of individuals meeting either the clinical or imaging arms of the ASAS classification criteria [112–115]. Trials of anti-TNF in nr-axSpA demonstrated good ASAS40 responses, ranging from 32 to 57%. AxSpA-associated acute anterior uveitis also responded well to certolizumab in a single open-label trial where uveitis flares fell by 87% [116]. Uveitis flares on etanercept are believed to be more common than on other TNF inhibitors [117]. TNF blockade is also recognized to provide significant improvements in enthesitis in AxSpA, with uncommon adverse events such as serious infection or injection site reaction (118). They are also an established treatment for psoriasis and IBD, favoring its use when these comorbidities are present.

The efficacy of IL-17 inhibitors for axial symptoms of nr-axSpA has been demonstrated by two large placebo-controlled RCTs with ASAS40 responses of 35–42% [119, 120]. Their efficacy has not been directly compared to TNF inhibitors in nr-axSpA, while their serious adverse event rate is similar [121]. IL-17 blockade is highly effective for psoriasis and has a small but significant effect on enthesitis in AS, but does not improve IBD and has no evidence for treatment of anterior uveitis [122, 123]. Large trials of the IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab for nr-axSpA and AS found no benefit compared to placebo [124].

High disease activity is more likely to respond to TNF inhibition. This is most evident when measures of disease activity are combined. ASDAS-CRP, which scores symptoms and CRP, is highly predictive of response to TNF inhibitors in nr-axSpA RCTs, while the value of the symptom-only score BASDAI has mixed results [125–128]. The combination of an ASAS-positive MRI and elevated CRP appears to have some predictive value—two secondary analyses of RCTs observed a modestly higher treatment response [125, 129].

Elevated CRP alone appears to have low-to-moderate predictive value for treatment response, while MRI sacroiliitis alone does not have definite predictive value. In two nr-axSpA RCTs, elevated CRP predicted a two-fold increase in treatment response, whereas another RCT found only a very small difference (OR 1.04) [112, 125, 126]. MRI sacroiliitis at baseline was compared to treatment response in four nr-axSpA RCTs. Three found no predictive effect and one a very small effect (OR 1.02) [112, 125, 126, 130].

Other investigations for predictors of TNF inhibitor response, including fibromyalgia, HLA-B27, age, obesity, and smoking have had negative or inconclusive results. Comorbid fibromyalgia does not significantly change the improvement in disease activity scores, although it does increase their baseline values [33, 34]. HLA-B27’s predictive value has highly inconsistent reports from three nr-axSpA RCTs and one axSpA RCT [112, 125, 126, 130]. Half found predictive value of moderate size and half found no value. Age at TNF commencement and gender have wide estimates of effect, ranging from no association to moderate or large effect sizes [112, 125, 126, 130–134]. Two very large longitudinal axSpA cohorts compared smoking to treatment response—one found a large detrimental effect and the other no difference [135, 136]. No interventional studies directly assess whether obesity influences response to TNF inhibitors in nr-axSpA, a phenomenon observed in axSpA and SpA [134, 137]. No difference was observed between the > 70 kg and < 70 kg groups in the ABILITY-1 nr-axSpA RCT [112].

TNF inhibitor dose reductions are associated with an increase in risk of flares, while TNF inhibitor cessation has a significant risk of flare.

RCTs of TNF cessation versus continuation in nr-axSpA report very high flare rates of 70–87% over 48–68 weeks [138, 139]. Doubling the dosing interval only slightly increased the flare rate from 16.3 to 21%. In axSpA, two of three open-label trials that halved TNF doses observed an increase in flares of 19–27% within 1 year, significantly higher than no dose reduction [140–142].

Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life

Function and quality of life are frequently affected by nr-axSpA and are strongly influenced by disease activity and comorbidities. These outcomes improve in treatment responders.

Functional impairment in nr-axSpA is similar to AS with similar scores for axial spondyloarthritis disease activity, mental and physical impairment, quality of life scores, and sleep outcomes [143–146]. Occupational impairment is common, causing self-reported decreased productivity at work in 25–79% and disease-related absence from work in 8–19% for an average of 2.5 days per month [147–151]. Functional impairment frequently affects home life, causing an inability to perform domestic tasks 6.5 days per month, and missed family, social and leisure activities 5.4 days per month [151].

Disease activity is strongly predictive of quality of life, function, and work participation scores, and these outcomes improve in treatment responders [152, 153]. Disease activity is also correlated with fatigue, although only slight improvement in fatigue has been observed after starting TNF inhibitors [143, 154].

Some common comorbidities worsen function in nr-axSpA. The presence of fibromyalgia confers higher disease activity scores, with and without TNF inhibitor treatment [33, 34]. Fibromyalgia in axSpA cohorts is an established contributor to higher disease activity scores and lower quality-of-life scores [32, 34, 147, 155]. Depression, fatigue, and negative perceptions of illness are also predictors of worse function and quality of life [19, 147, 156, 157].

Discussion

Diagnosis and treatment of nr-axSpA is challenging for all clinicians, and this area has progressed rapidly over the last decade. While the nature of many disease-related concepts are still unclear or controversial, we present 22 statements using the best available literature and summarize evolving disease concepts.

Initial assessment of suspected nr-axSpA should involve taking a history and examination for features of spondyloarthritis and alternative causes of back symptoms, testing of HLA-B27, and CRP and plain pelvic radiography. If radiography does not show definite sacroiliac changes and nr-axSpA is still suspected, sacroiliac T1 and STIR MRI adds valuable diagnostic information. Signs typical of sacroiliitis on MRI can occur in the absence of axSpA, and therefore must be considered alongside other clinical features.

Initial management should include a regular exercise program and an NSAID. If the diagnosis of nr-axSpA is clear and disease activity remains high despite these interventions, biologic therapy can be considered. Functional impairment, quality of life, and work impairment is similar to AS, and improves in treatment responders. We anticipate that future practice-changing developments will occur in the fields of MRI interpretation and pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted grants from Novartis, UCB Pharma, Janssen, and Pfizer. This funding paid for investigator time and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: all authors. Literature review and presentation: ST, TM. Drafting the manuscript: ST. Approving final manuscript version: all authors. The authors would like to thank Linda Bradbury and our patient representatives for reviewing and commenting on this manuscript.

Disclosures

Lionel Schachna and Tim McEwan have no disclosures. All other authors except Philip Robinson received an honorarium from the University of Queensland funded by Novartis, UCB, Pfizer, and Janssen related to this publication. Steven Truong reports advisory boards from Novartis and Eli Lilly and speaker fees from Novartis. Paul Bird reports advisory board fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Research grant funding from UCB, Janssen and Novartis; (all unrelated to this work). Irwin Lim has received speaker fees and being involved in advisory boards with AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Nivene Saad reports past board guest advisor for AbbVie, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. Andrew Taylor reports advisory boards and speaker fees from AbbVie, Lily, Novartis, Gilead, UCB and Pfizer. Philip Robinson reports personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Kukdong, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Research grant funding from UCB, Janssen, and Novartis; non-financial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb (all unrelated to this work).

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Search terms are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. All results are listed in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson PC, Sengupta R, Siebert S. Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA): advances in classification. Imaging Ther Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(2):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s40744-019-0146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Linden S, Akkoc N, Brown MA, Robinson PC, Khan MA. The ASAS criteria for axial spondyloarthritis: strengths, weaknesses, and proposals for a way forward. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(9):62. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0535-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michelena X, López-Medina C, Marzo-Ortega H. Non-radiographic versus radiographic axSpA: what’s in a name? Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2020;59(Supplement_4):iv18–24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrada I, Devilliers H, Fayolle C, Attané G, Loffroy R, Verhoeven F, et al. Diagnostic performance of sacroiliac and spinal MRI for the diagnosis of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients with inflammatory back pain. J Bone Spine. 2020;88(2):105106. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.105106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, Jurik AG, Hermann K-GA, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, et al. Defining active sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: a consensual approach by the ASAS/OMERACT MRI group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1520–1527. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.110767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poddubnyy D. Classification vs diagnostic criteria: the challenge of diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2020;59(Supplement_4):iv6–17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson PC, van der Linden S, Khan MA, Taylor WJ. Axial spondyloarthritis: concept, construct, classification and implications for therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(2):109–118. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1000–1008. doi: 10.1002/art.20990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson PC, Wordsworth BP, Reveille JD, Brown MA. Axial spondyloarthritis: a new disease entity, not necessarily early ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):162–164. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang R, Gabriel SE, Ward MM. Progression of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis to ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(6):1415–1421. doi: 10.1002/art.39542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Sepriano A, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):978–991. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Dubreuil M, Yu D, Khan MA, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1599–1613. doi: 10.1002/art.41042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson PC, Bird P, Lim I, Saad N, Schachna L, Taylor AL, et al. Consensus statement on the investigation and management of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(5):548–556. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joo W, Almario CV, Ishimori M, Park Y, Jusufagic A, Noah B, et al. Examining treatment decision-making among patients with axial spondyloarthritis: insights from a conjoint analysis survey. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(7):391–400. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindström Egholm C, Krogh NS, Pincus T, Dreyer L, Ellingsen T, Glintborg B, et al. Discordance of global assessments by patient and physician is higher in female than in male patients regardless of the physician’s sex: data on patients with rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis from the DANBIO registry. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(10):1781–1785. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gossec L, Berenbaum F, Chauvin P, Hudry C, Cukierman G, de Chalus T, et al. Development and application of a questionnaire to assess patient beliefs in rheumatoid arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(10):2649–2657. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Lunteren M, Scharloo M, Ez-Zaitouni Z, de Koning A, Landewé R, Fongen C, et al. The impact of illness perceptions and coping on the association between back pain and health outcomes in patients suspected of having axial spondyloarthritis: data from the SPondyloArthritis caught early cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(12):1829–1839. doi: 10.1002/acr.23566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Lunteren M, Landewé R, Fongen C, Ramonda R, van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA. van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA. Do illness perceptions and coping strategies change over time in patients recently diagnosed with axial spondyloarthritis? J Rheum. 2020;47(12):1752–1759. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.191353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molto A, Gossec L, Poiraudeau S, Claudepierre P, Soubrier M, Fayet F, et al. Evaluation of the impact of a nurse-led program of systematic screening of comorbidities in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: the results of the COMEDSPA prospective, controlled, one year randomized trial. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(4):701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammer NM, Flurey CA, Jensen KV, Andersen L, Esbensen BA. Preferences for self-management and support services in patients with inflammatory joint disease—A Danish Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73(10):1479–1489. doi: 10.1002/acr.24344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bech B, Primdahl J, van Tubergen A, Voshaar M, Zangi HA, Barbosa L, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):61–68. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, Andersen L, Bode C, Boström C, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):954–962. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poddubnyy D, Callhoff J, Spiller I, Listing J, Braun J, Sieper J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of inflammatory back pain for axial spondyloarthritis in rheumatological care. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000825. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieper J, Srinivasan S, Zamani O, Mielants H, Choquette D, Pavelka K, et al. Comparison of two referral strategies for diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis: the Recognising and Diagnosing Ankylosing Spondylitis Reliably (RADAR) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1621–1627. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomero E, Mulero J, de Miguel E, Fernández-Espartero C, Gobbo M, Descalzo MA, et al. Performance of the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society criteria for the classification of spondyloarthritis in early spondyloarthritis clinics participating in the ESPERANZA programme. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2014;53(2):353–360. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Lunteren M, van der Heijde D, Sepriano A, Berg IJ, Dougados M, Gossec L, et al. Is a positive family history of spondyloarthritis relevant for diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis once HLA-B27 status is known? Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2019;58(9):1649–1654. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baraliakos X, Tsiami S, Redeker I, Tsimopoulos K, Marashi A, Ruetten S, et al. Early recognition of patients with axial spondyloarthritis-evaluation of referral strategies in primary care. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2020;59(12):3845–3852. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro MP, Stebbings SM, Milosavljevic S, Pedersen SJ, Bussey MD. Assessing the construct validity of clinical tests to identify sacroiliac joint inflammation in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(8):1521–1528. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baraliakos X, Regel A, Kiltz U, Menne H-J, Dybowski F, Igelmann M, et al. Patients with fibromyalgia rarely fulfil classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2018;57(9):1541–1547. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rencber N, Saglam G, Huner B, Kuru O. Presence of fibromyalgia syndrome and its relationship with clinical parameters in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Pain Physician. 2019;22(6):E579–E585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moltó A, Etcheto A, Gossec L, Boudersa N, Claudepierre P, Roux N, et al. Evaluation of the impact of concomitant fibromyalgia on TNF alpha blockers’ effectiveness in axial spondyloarthritis: results of a prospective, multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):533–540. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macfarlane GJ, MacDonald RIR, Pathan E, Siebert S, Gaffney K, Choy E, et al. Influence of co-morbid fibromyalgia on disease activity measures and response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in axial spondyloarthritis: results from a UK national register. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2018;57(11):1982–1990. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ablin JN, Eshed I, Berman M, Aloush V, Wigler I, Caspi D, et al. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis among patients with fibromyalgia: a magnetic resonance imaging study with application of the assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(5):724–729. doi: 10.1002/acr.22967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dougados M, Etcheto A, Molto A, Alonso S, Bouvet S, Daurès J-P, et al. Clinical presentation of patients suffering from recent onset chronic inflammatory back pain suggestive of spondyloarthritis: The DESIR cohort. Jt Bone Spine. 2015;82(5):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deodhar A, Mease PJ, Reveille JD, Curtis JR, Chen S, Malhotra K, et al. Frequency of axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis among patients seen by us rheumatologists for evaluation of chronic back pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(7):1669–1676. doi: 10.1002/art.39612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallman JK, Kapetanovic MC, Petersson IF, Geborek P, Kristensen LE. Comparison of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis patients–baseline characteristics, treatment adherence, and development of clinical variables during three years of anti-TNF therapy in clinical practice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;24(17):378. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0897-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turina MC, Yeremenko N, van Gaalen F, van Oosterhout M, Berg IJ, Ramonda R, et al. Serum inflammatory biomarkers fail to identify early axial spondyloarthritis: results from the SpondyloArthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. RMD Open. 2017;3(1):e000319. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong C, Kwan YH, Leung Y-Y, Lui NL, Fong W. Comparison of ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in a multi-ethnic Asian population of Singapore. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(8):1506–1511. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bubová K, Forejtová Š, Zegzulková K, Gregová M, Hušáková M, Filková M, et al. Cross-sectional study of patients with axial spondyloarthritis fulfilling imaging arm of ASAS classification criteria: baseline clinical characteristics and subset differences in a single-centre cohort. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e024713. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landewé R, Nurminen T, Davies O, Baeten D. A single determination of C-reactive protein does not suffice to declare a patient with a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis “CRP-negative”. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ez-Zaitouni Z, Bakker PAC, van Lunteren M, Berg IJ, Landewé R, van Oosterhout M, et al. Presence of multiple spondyloarthritis (SpA) features is important but not sufficient for a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis: data from the SPondyloArthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1086–1092. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moltó A, Paternotte S, Comet D, Thibout E, Rudwaleit M, Claudepierre P, et al. Performances of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society axial spondyloarthritis criteria for diagnostic and classification purposes in patients visiting a rheumatologist because of chronic back pain: results from a multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(9):1472–1481. doi: 10.1002/acr.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ziade N, Abi Karam G, Merheb G, Mallak I, Irani L, Alam E, et al. HLA-B27 prevalence in axial spondyloarthritis patients and in blood donors in a Lebanese population: results from a nationwide study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(4):708–714. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derakhshan MH, Dean L, Jones GT, Siebert S, Gaffney K. Predictors of extra-articular manifestations in axial spondyloarthritis and their influence on TNF-inhibitor prescribing patterns: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register in Ankylosing Spondylitis. RMD Open. 2020;6(2):e001206. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Truong SL, Saad NF, Robinson PC, Cowderoy G, Lim I, Schachna L, et al. Consensus statements on the imaging of axial spondyloarthritis in Australia and New Zealand. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2017;61(1):58–69. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diekhoff T, Hermann K-GA, Greese J, Schwenke C, Poddubnyy D, Hamm B, et al. Comparison of MRI with radiography for detecting structural lesions of the sacroiliac joint using CT as standard of reference: results from the SIMACT study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(9):1502–1508. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joven BE, Navarro-Compán V, Rosas J, Dapica PF, Zarco P, de Miguel E. Diagnostic value and validity of early spondyloarthritis features: results from a National Spanish Cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(6):938–942. doi: 10.1002/acr.23017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molto A, Gossec L, Lefèvre-Colau M-M, Foltz V, Beaufort R, Laredo J-D, et al. Evaluation of the performances of “typical” imaging abnormalities of axial spondyloarthritis: results of the cross-sectional ILOS-DESIR study. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000918. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Włodkowska-Korytkowska M, Kwiatkowska B. Spectrum of inflammatory changes in the SIJs on radiographs and MR images in patients with suspected axial spondyloarthritis. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:125–133. doi: 10.12659/PJR.895867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sahuguet J, Fechtenbaum J, Molto A, Etcheto A, López-Medina C, Richette P, et al. Low incidence of vertebral fractures in early spondyloarthritis: 5-year prospective data of the DESIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):60–65. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forien M, Moltó A, Etcheto A, Dougados M, Roux C, Briot K. Bone mineral density in patients with symptoms suggestive of spondyloarthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(5):1647–1653. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akgöl G, Kamanlı A, Ozgocmen S. Evidence for inflammation-induced bone loss in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2014;53(3):497–501. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ez-Zaitouni Z, Landewé R, van Lunteren M, Bakker PA, Fagerli KM, Ramonda R, et al. Imaging of the sacroiliac joints is important for diagnosing early axial spondyloarthritis but not all-decisive. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2018;57(7):1173–1179. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sepriano A, Landewe R, Van Der Heijde D, Sieper J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. Predictive validity of the ASAS classification criteria for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis after follow-up in the ASAS cohort: a final analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1034–1042. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yap KS, Ye JY, Li S, Gladman DD, Chandran V. Back pain in psoriatic arthritis: defining prevalence, characteristics and performance of inflammatory back pain criteria in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(11):1573–1577. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carvalho PD, Savy F, Moragues C, Juanola X, Rodriguez-Moreno J. Axial involvement according to ASAS criteria in an observational psoriatic arthritis cohort. Acta Reumatol Port. 2017;42(2):176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Hermann K, Landewé R, Machado P, Maksymowych W, et al. Limited radiographic progression and sustained reductions in MRI inflammation in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: 4-year imaging outcomes from the RAPID-axSpA phase III randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(5):699–705. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sepriano A, Ramiro S, Landewé R, Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Rudwaleit M. Is active sacroiliitis on MRI associated with radiographic damage in axial spondyloarthritis? Real-life data from the ASAS and DESIR cohorts. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2019;58(5):798–802. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ye L, Liu Y, Xiao Q, Dong L, Wen C, Zhang Z, et al. MRI compared with low-dose CT scanning in the diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(4):1295–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diekhoff T, Greese J, Sieper J, Poddubnyy D, Hamm B, Hermann K-GA. Improved detection of erosions in the sacroiliac joints on MRI with volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination (VIBE): results from the SIMACT study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(11):1585–1589. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kucybała I, Ciuk S, Urbanik A, Wojciechowski W. The usefulness of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequences visual assessment in the early diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(9):1559–1565. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan CWS, Tsang HHL, Li PH, Lee KH, Lau CS, Wong PYS, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging versus short tau inversion recovery sequence: usefulness in detection of active sacroiliitis and early diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradbury LA, Hollis KA, Gautier B, Shankaranarayana S, Robinson PC, Saad N, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging is a sensitive and specific magnetic resonance sequence in the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(6):771–778. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boy FN, Kayhan A, Karakas HM, Unlu-Ozkan F, Silte D, Aktas İ. The role of multi-parametric MR imaging in the detection of early inflammatory sacroiliitis according to ASAS criteria. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(6):989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weber U, Maksymowych WP, Chan SM, Rufibach K, Pedersen SJ, Zhao Z, et al. Does evaluation of the ligamentous compartment enhance diagnostic utility of sacroiliac joint MRI in axial spondyloarthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0729-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Der Heijde D, Sieper J, Maksymowych W, Brown M, Lambert R, Rathmann S, et al. Spinal inflammation in the absence of sacroiliac joint inflammation on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(3):667–673. doi: 10.1002/art.38283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber U, Zubler V, Zhao Z, Lambert RGW, Chan SM, Pedersen SJ, et al. Does spinal MRI add incremental diagnostic value to MRI of the sacroiliac joints alone in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):985–992. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maksymowych W, Wichuk S, Dougados M, Jones H, Szumski A, Bukowski J, et al. MRI evidence of structural changes in the sacroiliac joints of patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis even in the absence of MRI inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weber U, Østergaard M, Lambert RGW, Pedersen SJ, Chan SM, Zubler V, et al. Candidate lesion-based criteria for defining a positive sacroiliac joint MRI in two cohorts of patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(11):1976–1982. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krabbe S, Sørensen IJ, Jensen B, Møller JM, Balding L, Madsen OR, et al. Inflammatory and structural changes in vertebral bodies and posterior elements of the spine in axial spondyloarthritis: construct validity, responsiveness and discriminatory ability of the anatomy-based CANDEN scoring system in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000624. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maksymowych WP, Lambert RG, Baraliakos X, Weber U, Machado PM, Pedersen SJ, et al. Data-driven definitions for active and structural MRI lesions in the sacroiliac joint in spondyloarthritis and their predictive utility. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2021;60(10):4778–4789. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rusman T, John M-LB, van der Weijden MAC, Boden BJH, van der Bijl CMA, Bruijnen STG, et al. Presence of active MRI lesions in patients suspected of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis with high disease activity and chance at conversion after a 6-month follow-up period. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(5):1521–1529. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04885-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bakker PAC, Ramiro S, Ez-Zaitouni Z, van Lunteren M, Berg IJ, Landewé R, et al. Is it useful to repeat magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joints after three months or one year in the diagnosis of patients with chronic back pain and suspected axial spondyloarthritis? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(3):382–391. doi: 10.1002/art.40718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Onna M, van Tubergen A, Jurik AG, van der Heijde D, Landewé R. Natural course of bone marrow oedema on magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joints in patients with early inflammatory back pain: a 2-year follow-up study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(2):129–134. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2014.933247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baraliakos X, Sieper J, Chen S, Pangan A, Anderson J. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis patients without initial evidence of inflammation may develop objective inflammation over time. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2017;56(7):1162–1166. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Onna M, Jurik AG, van der Heijde D, van Tubergen A, Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Landewé R. HLA-B27 and gender independently determine the likelihood of a positive MRI of the sacroiliac joints in patients with early inflammatory back pain: a 2-year MRI follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1981–1985. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weber U, Jurik AG, Zejden A, Larsen E, Jørgensen SH, Rufibach K, et al. Frequency and anatomic distribution of magnetic resonance imaging features in the sacroiliac joints of young athletes: exploring “Background Noise” toward a data-driven definition of sacroiliitis in early spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(5):736–745. doi: 10.1002/art.40429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Agten CA, Zubler V, Zanetti M, Binkert CA, Kolokythas O, Prentl E, et al. Postpartum bone marrow edema at the sacroiliac joints may mimic sacroiliitis of axial spondyloarthritis on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(6):1306–1312. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Winter J, de Hooge M, van de Sande M, de Jong H, van Hoeven L, de Koning A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joints indicating sacroiliitis according to the assessment of spondyloarthritis international society definition in healthy individuals, runners, and women with postpartum back pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(7):1042–1048. doi: 10.1002/art.40475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varkas G, de Hooge M, Renson T, De Mits S, Carron P, Jacques P, et al. Effect of mechanical stress on magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joints: assessment of military recruits by magnetic resonance imaging study. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2018;57(3):508–513. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Renson T, Carron P, De Craemer A-S, Deroo L, de Hooge M, Krabbe S, et al. Axial involvement in patients with early peripheral spondyloarthritis: a prospective MRI study of sacroiliac joints and spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;80(1):103–108. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seven S, Østergaard M, Morsel-Carlsen L, Sørensen IJ, Bonde B, Thamsborg G, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of lesions in the sacroiliac joints for differentiation of patients with axial spondyloarthritis from control subjects with or without pelvic or buttock pain: a prospective, cross-sectional study of 204 participants. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(12):2034–2046. doi: 10.1002/art.41037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin Z, Liao Z, Huang J, Jin O, Li Q, Li T, et al. Evaluation of Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis in Chinese patients with chronic back pain: results of a 2-year follow-up study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(7):782–789. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gazeau P, Cornec D, Timsit MA, Dougados M, Saraux A. Classification criteria versus physician’s opinion for considering a patient with inflammatory back pain as suffering from spondyloarthritis. Jt Bone Spine. 2018;85(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sveaas S, Bilberg A, Berg I, Provan S, Rollefstad S, Semb A, et al. High intensity exercise for 3 months reduces disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA): a multicentre randomised trial of 100 patients. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(5):292–297. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sveaas S, Dagfinrud H, Berg I, Provan S, Johansen M, Pedersen E, et al. High-intensity exercise improves fatigue, sleep, and mood in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2020;100(8):1323–1332. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.García RF, de Sánchez LCS, Mdel MLR, Granados GS. Effects of an exercise and relaxation aquatic program in patients with spondyloarthritis: a randomized trial. Med Clin (Barc) 2015;145(9):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Levitova A, Hulejova H, Spiritovic M, Pavelka K, Senolt L, Husakova M. Clinical improvement and reduction in serum calprotectin levels after an intensive exercise programme for patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):275. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]