Abstract

Background:

Previous studies have suggested consumption of red meat may be associated with an increased risk of developing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). However, large-scale, prospective data regarding red meat consumption in relation to the incidence of NAFLD are lacking, nor is it known whether any association is mediated by obesity.

Objective:

We aimed to evaluate the relationship between red meat consumption and the subsequent risk of developing NAFLD.

Design:

This prospective cohort study included 77,795 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort without NAFLD at baseline (in 1995), who provided detailed, validated information regarding diet, including consumption of red meat, every 4 years, followed through 2015. Lifestyle factors, clinical comorbidities and body mass index (BMI), were updated biennially. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

Over 1,444,637 person years of follow-up, we documented 3,130 cases of incident NAFLD. Compared to women who consumed ≤1 serving/week of red meat, the multivariable-adjusted HRs of incident NAFLD were 1.20 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.50) for 2–4 servings/week; 1.31 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.61) for 5–6 servings/week; 1.41 (95% CI: 1.13, 1.75) for 1 serving/day; and 1.52 (95% CI: 1.23, 1.89) for ≥2 servings/day. However, after further adjustment for BMI, all associations for red meat, including unprocessed and processed red meat, were attenuated and not statistically significant (all P-trend>0.05). BMI was estimated to mediate 66.1% (95% CI: 41.8%, 84.2%; P<0.0001) of the association between red meat consumption and NAFLD risk.

Conclusions:

Red meat consumption, including both unprocessed and processed red meat, was associated with significantly increased risk of developing NAFLD. This association was mediated largely by obesity.

Keywords: Red meat, Obesity, NAFLD, Women, Epidemiology

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as a result of its growing health and economic burden in both developed and developing countries [1]. NAFLD is pathogenically associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome, and can progress to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure [2, 3]. NAFLD is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus [4], and is associated with several extra-hepatic chronic complications including chronic kidney disease and certain type of cancer [5].

It has been suggested that a Western dietary pattern characterized by overconsumption of fructose [6], saturated fat and cholesterol [7], and lower intake of fiber, plays an important role in the development and progression of NAFLD [8]. Red meat is comprised of a considerable portion of the Western-style diet [9], and is rich in a variety of essential nutrients, including protein, iron, zinc, and vitamin B12 [10]. However, red meat contains high levels of saturated fatty acids and cholesterol [7, 11–13], as well as other potentially harmful compounds such as heme iron, and advanced glycation end products [14, 15]. In addition, sodium and nitrate preservatives are rich in processed red meat. [15] Average of 400% more sodium is contained in processed red meat than unprocessed red meat in the US [16].

Epidemiological studies have shown that red meat consumption is associated with increased risks of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [17–19], metabolic syndrome [19], and oxidative stress [20]. While two recent studies have demonstrated the positive association between red meat intake and NAFLD [21, 22], both have been limited by cross-sectional design, which may not accurately represent the long-term effect of red meat consumption in the longitudinal development of NAFLD. Furthermore, although an association for consumption of red meat with obesity was demonstrated [23, 24], no previous study has examined the potential role of obesity as a mediator of the association between red meat and NAFLD risk.

Thus, we conducted a nationwide, prospective cohort study of US women with 20 years of long-term follow-up, to comprehensively evaluate the relationship between red meat consumption and the subsequent risk of developing NAFLD. Moreover, given the robust evidence linking red meat intake with obesity [23, 24], as well as the close relationship between obesity and the development of NAFLD [25, 26], we also examined the potential mediating influence of obesity in explaining the relationship between red meat consumption and NAFLD risk.

Methods

Study Population

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II) is an ongoing, prospective US cohort study that began in 1989 with the enrollment of 116,430 US female registered nurses, aged 25 to 42 years. Every 2 years since enrollment, participants have provided detailed information regarding demographics, lifestyle factors, medical history and disease outcomes, and dietary information has been prospectively updated every 4 years, with an average follow-up that exceeds 90% [27]. For the current study, we included women who completed the questionnaire in 1995, which we established as the baseline of the current study, the first survey that collected detailed information regarding NAFLD. We excluded women with a diagnosis of NAFLD at baseline (n=308), a diagnosis of hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection (n=974), cirrhosis (n=12), and excess alcohol intake (defined as weekly alcohol consumption of more than 140 g [28]) (n=2,202). Consistent with prior work [29], we further excluded participants with missing body mass index (BMI) (n=14,110) and energy intake (n=19,602), who reported implausible energy intake (<500 or ≥3,500 kcal/d, n=7), and who did not answer questions regarding intake of meat (n=11). After these exclusions, a total of 77,795 participants were eligible for this study. Participants were followed prospectively through June 30, 2015.

The NHS II cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Informed consent was indicated by questionnaire return.

Ascertainment and Validation of NAFLD

The primary endpoint was a physician-confirmed diagnosis of NAFLD. In 2013 and 2015, participants were asked if they had received a diagnosis from a physician of fatty liver disease. If yes, participants were subsequently asked the year of diagnosis (dating back to before 1995), the method of diagnosis, details regarding the presence or absence of cirrhosis, and diagnoses of either hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection. In a validation study within our parallel cohort of female nurses (NHS I), a blinded study physician reviewed 33 randomly-selected medical records from women who met our criteria for NAFLD, and applied validated radiographic and/or histological criteria to identify hepatic steatosis, and excluded alternative etiologies of liver disease [30]. With that algorithm, 29/33 cases were confirmed to have NAFLD (positive predictive value, 88%).

Assessment of Dietary Intake

Detailed dietary information was ascertained at baseline (1995) using a validated, semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [31–34], and updated every 4 years, thereafter. In each FFQ, participants were asked to report the average frequency of consumption of foods with a commonly used portion size during the previous year. With each questionnaire, participants quantified how frequently they consumed a standard portion of a specific food item during the previous year, using 9 categories ranging from, “never or less than once per month”, to, “more than 6 times daily”. The cumulative average intakes of total and specific types of meat were calculated by multiplying the portion size of a single serving of each meat item by its reported frequency of intake over time from baseline to the current questionnaire (in 1995, 2003, 2007, and 2011). As previously described [35], questions regarding unprocessed red meat intake included, “beef, pork or lamb as main dish” (pork was separately asked since 1990), “hamburger”, and “beef, pork or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish”, and the standard serving size for unprocessed red meat was 85g (3 ounces). Processed red meat included “bacon” (2 slices, i.e. 28g), “hot dogs” (one, i.e. 45g), and “sausage, salami, bologna and other processed red meat” (one piece, i.e. 45g). Detailed questions were also asked regarding poultry (i.e. chicken or turkey) and fish, as previously described. Total meat consumption, as well as intake of red meat (including processed and unprocessed red meat), poultry and fish were calculated by multiplying the portion size of a single serving of each meat item by its frequency of intake. The reproducibility and validity of the FFQ have been extensively assessed in these cohorts [31–33]. The correlation coefficients between the FFQ and prospectively collected 1-week dietary records were 0.59 for unprocessed red meat and 0.52 for processed red meat [33, 34].

Assessment of Covariates

Details regarding the ascertainment and validation of lifestyle factors in this cohort have been described [36–38]. Briefly, height, body weight, smoking, and physical activity were self-reported on validated biennial questionnaires at baseline and updated every 2 years, with high validity and reproducibility that has been demonstrated [39–41]. Waist circumference (WC) was self-reported in 1989, and updated again in 1993 and 2005 [42]. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2) and categorized in 3 groups (i.e. <25, 25 to <30 and ≥30 kg/m2), and these data were updated prospectively over follow-up. Each type of physical activity was defined as a metabolic equivalent of tasks (MET) score based on energy expenditure, and the MET score was multiplied by the mean time spent in each activity to calculate the amount of total physical activity [40]. From each FFQ, we also ascertained other food intake, regular alcohol consumption, and total caloric intake, and these data were updated, every 4 years. The Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 was used to assess diet quality, with a higher score reflecting a healthier dietary pattern [43, 44]. On each biennial questionnaire, participants also provided validated information regarding clinical comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and incident diagnoses of viral hepatitis, and use of medications, including aspirin and menopausal hormone therapy [45–48].

Statistical analysis

Follow-up time was calculated from the date of the baseline questionnaire until the date of NAFLD diagnosis, last follow-up questionnaire, or the end of the study period, whichever came first.

All the finally enrolled participants who completed the last questionnaire reported the diagnostic status of fatty liver. To better reflect the association of long-term red meat intake with study outcome, and to minimize within-person variation, the cumulative average intake of red meat was calculated over time from baseline to the current questionnaire cycle from the repeated FFQs [49]. Similarly, we calculated the cumulative average intake of other dietary variables and other appropriate covariates. We stopped updating these covariates when participants reported NAFLD because covariates after development of NAFLD may confound the association between red meat and NAFLD risk.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between different categories of red meat consumption was analyzed using analysis of variance and Chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models with time-varying exposures and covariates to calculate age- and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Our primary exposure was total red meat consumption; additional analyses focused on consumption of specific types of meat (i.e. processed and unprocessed red meat, poultry and fish). Covariates were selected a priori based on established risk factors for NAFLD; multivariable model 1 accounted for race (white/non-white) and time-varying covariates, including total caloric intake, diabetes (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), dyslipidemia (yes/no), smoking status (never, past, current), physical activity (quintiles), regular use of aspirin use (yes/no), menopausal status (premenopausal or postmenopausal), and menopausal hormone use (never, past, or current). Model 2 included all covariates in model 1 plus BMI, in order to specifically evaluate the effect of BMI on the association between red meat intake and NAFLD risk. For all models, tests for linear trends were performed using continuous variables.

We performed stratified analyses according to age, BMI, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking status, physical activity, menopausal status, and aspirin use, and we tested for evidence of significant effect modification using the log likelihood ratio test. We also investigated whether BMI might mediate the association between red meat intake and NAFLD risk, using an established macro (Mediate SAS; Harvard School of Public Health; available at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/faculty/donna-spiegelman/software/mediate/) [50].

We performed a series of sensitivity analyses, to test the robustness of our results. To assess whether specific nutrient(s) concentrations in red meat (i.e. iron, animal fat or palmitic acid) might have influenced our findings, we constructed separate multivariable-adjusted models further accounting for heme iron, iron, animal fat, cholesterol, nitrate or palmitic acid. We repeated primary analysis after excluding anyone diagnosed with NAFLD within the first 3 years of follow-up to address potential reverse causation. We also repeated primary analysis after excluding participants who reported an incident diagnosis of hepatitis B or C virus infection during follow-up. Finally, we investigated the association of red meat consumption with the risk of cirrhosis (physician diagnosed, self-reported).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), with a two-tailed P-value set at ≤0.05.

Results

Over 1,444,637 person-years of follow-up, we documented 3,130 cases of incident NAFLD. Women who consumed more total red meat (i.e. both processed and unprocessed red meat) had higher overall BMI, were less physically active, and more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. They had lower Alternative Healthy Eating Index score, consumed a greater total caloric intake, less whole grains, less plant-based proteins, less fruits, and less vegetables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to red meat consumption

| ≤1 serving/week (n = 5,432) | 2–4 servings/week (n = 15,358) | 5–6 servings/week (n = 25,749) | 1 serving/day (n = 11,747) | ≥2 serving/day (n = 19,509) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 40.6 (4.6) | 40.4 (4.7) | 40.1 (4.7) | 40 (4.7) | 39.9 (4.6) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.7 (4.7) | 24.8 (5.2) | 25.6 (5.7) | 26.2 (5.9) | 27.1 (6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 82.1 (11.5) | 84.3 (11.9) | 85.8 (12.7) | 86.7 (13.0) | 88.3 (14.1) | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week | 33.2 (39.5) | 24.4 (29.7) | 20.0 (25.3) | 18 (23) | 16.9 (23) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | |||||

| Never, % | 67.1 | 67.6 | 68.1 | 69.4 | 69.6 | |

| Past,% | 29.3 | 27.1 | 25 | 22.6 | 20.5 | |

| Current, % | 3.6 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 9.8 | |

| Diabetes, % | 0.8 | 1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, % | 3.8 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 7.9 | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 8.5 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 11.3 | 12.7 | <0.0001 |

| Alternate Healthy Eating Index score | 61.6 (9.9) | 55.6 (9.5) | 50.1 (9) | 46.2 (8.7) | 42.2 (8.7) | <0.0001 |

| Regular aspirin use1 % | 22.9 | 23.5 | 24.2 | 25.2 | 25.7 | <0.0001 |

| Premenopausal, % | 93.3 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.3 | 92 | <0.0001 |

| Current menopausal hormone,2 % | 4.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.3 | 6.5 | <0.0001 |

| Race (white), % | 95.2 | 96.2 | 97 | 97 | 96.8 | <0.0001 |

| Total calories, kcal | 1531.7 (510.2) | 1540.3 (476) | 1706 (480.9) | 1890 (487) | 2177.3 (540.7) | <0.0001 |

| Poultry, servings per day | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Fish, servings per day | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Legume, servings per day | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Whole grains, servings per day | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Nut, servings per day | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Plant-based protein, servings per day | 2.3 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Fruits, servings per day | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Vegetables, servings per day | 4.3 (2.9) | 3.5 (2.3) | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.4 (2.0) | 3.6 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: MET, metabolic equivalent of tasks.

All data were reported as mean (SD) or percentage (%). Except for mean of age, all data were standardized to the age distribution of the study population.

Regular aspirin use was defined as the regular use of at least 2 aspirin pills per week.

Among postmenopausal participants.

Increasing total red meat consumption was significantly associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of incident NAFLD, after multivariable adjustment (P-trend <0.0001 for model 1; HR: 1.31 [95% CI: 1.18, 1.46] per 1 serving/day increase of total red meat) (Table 2). Compared to women who consumed ≤1 serving/week of red meat, the multivariable-adjusted HRs of incident NAFLD were 1.20 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.50) for 2–4 servings/week; 1.31 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.61) for 5–6 servings/week; 1.41 (95% CI: 1.13, 1.75) for 1 serving/day; and 1.52 (95% CI: 1.23, 1.89) for ≥2 servings/day. Similarly, significant and positive gradients of increasing risk were observed for both unprocessed and processed red meat consumption, after multivariable adjustment (both P-trend <0.0005 with model 1; HR: 1.29 [95% CI: 1.13, 1.47] per 1 serving/day increase of unprocessed red meat; HR: 1.80 [95% CI: 1.44, 2.26] per 1 serving/day increase of processed red meat). Although there was a significant trend toward increasing NAFLD risk with increasing poultry intake (P-trend<0.0001; HR: 1.49 [95% CI: 1.27, 1.75]), estimates for specific categories were not statistically significant. In contrast, fish intake was not significantly associated with NAFLD risk (P-trend=0.718).

Table 2.

Meat consumption and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Cases | Person years | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 1 multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)1 |

Model 2 multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total red meat | |||||

| ≤1 serving/week | 99 | 83394 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 2–4 servings/week | 451 | 266690 | 1.35 (1.09, 1.68) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.27) |

| 5–6 servings/week | 1064 | 510348 | 1.64 (1.33, 2.01) | 1.31 (1.06, 1.61) | 0.995 (0.81 to 1.23) |

| 1 serving/day | 554 | 234477 | 1.90 (1.54, 2.36) | 1.41 (1.13, 1.75) | 0.995 (0.80 to 1.24) |

| ≥2 servings/day | 962 | 349728 | 2.33 (1.90, 2.87) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.89) | 0.999 (0.81 to 1.24) |

| Per 1 serving/day increase | 1.82 (1.66, 2.01) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.46) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.10) | ||

| P for trend3 | .. | .. | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.855 |

| Unprocessed red meat | |||||

| ≤1 serving/week | 148 | 119702 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 2–4 servings/week | 943 | 472669 | 1.53 (1.28, 1.81) | 1.32 (1.11, 1.57) | 1.12 (0.94 to 1.34) |

| 5–6 servings/week | 1293 | 579591 | 1.70 (1.43, 2.02) | 1.32 (1.11, 1.56) | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.21) |

| 1 serving/day | 419 | 153351 | 2.19 (1.82, 2.64) | 1.52 (1.25, 1.84) | 1.09 (0.90 to 1.32) |

| ≥2 servings/day | 327 | 119324 | 2.36 (1.94, 2.86) | 1.50 (1.23, 1.84) | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.25) |

| Per 1 serving/day increase | 1.89 (1.68, 2.13) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.09) | ||

| P for trend3 | .. | .. | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.482 |

| Processed red meat | |||||

| < 1 serving/month | 114 | 107908 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 1–3 servings/month | 409 | 247377 | 1.29 (1.04, 1.58) | 1.16 (0.94, 1.43) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.24) |

| 1 serving/week | 626 | 320486 | 1.49 (1.22, 1.83) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.52) | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.21) |

| 2–4 servings/week | 1506 | 607929 | 1.88 (1.55, 2.27) | 1.41 (1.16, 1.71) | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.27) |

| ≥ 5 servings/week | 475 | 160938 | 2.43 (1.98, 2.98) | 1.56 (1.26, 1.92) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.31) |

| Per 1 serving/day increase | 3.50 (2.84, 4.31) | 1.80 (1.44, 2.26) | 1.12 (0.89, 1.41) | ||

| P for trend3 | .. | .. | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.326 |

| Poultry | |||||

| < 1 serving/month | 42 | 27746 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 1–3 servings/month | 87 | 61084 | 1.01 (0.70, 1.46) | 0.86 (0.59, 1.24) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.20) |

| 1 serving/week | 1147 | 586029 | 1.18 (0.87, 1.61) | 0.99 (0.73, 1.35) | 0.86 (0.63 to 1.17) |

| 2–4 servings/week | 1470 | 633099 | 1.35 (0.99, 1.84) | 1.12 (0.82, 1.52) | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.20) |

| ≥5 servings/week | 384 | 136679 | 1.65 (1.20, 2.26) | 1.28 (0.92, 1.76) | 0.91 (0.66 to 1.25) |

| Per 1 serving/day increase | 1.68 (1.44, 1.97) | 1.49 (1.26, 1.75) | 1.08 (0.91, 1.27) | ||

| P for trend3 | -- | -- | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.397 |

| Fish | |||||

| < 1 serving/month | 341 | 188460 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 1–3 servings/month | 935 | 458116 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 0.93 (0.82, 1.05) | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.06) |

| 1 serving/week | 1041 | 463365 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) |

| 2–4 servings/week | 778 | 312690 | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 1.02 (0.90, 1.17) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.16) |

| ≥ 5 servings/week | 35 | 22007 | 0.69 (0.49, 0.98) | 0.78 (0.55, 1.11) | 0.80 (0.56 to 1.13) |

| Per 1 serving/day increase | 0.82 (0.55, 1.24) | 1.08 (0.71, 1.66) | 1.07 (0.70, 1.64) | ||

| P for trend3 | -- | -- | 0.349 | 0.718 | 0.749 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for smoking status (never, past, current), total calories (continuous, kcal), menopausal hormone therapy (never, past, current, premenopausal), type 2 diabetes (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no), dyslipidemia (yes or no), physical activity (MET-hours/week, quintiles), regular use of aspirin (yes/no), fruits consumption (quartiles), vegetable consumption (quartiles), and race (white or non-white).

Adjusted for all covariates in Model 1, and additionally adjusted for current body mass index (<25, 25–29.9, 30+ kg/m2).

Calculated using the median value of each meat intake category as a continuous variable.

Further adjustment for consumption of other foods (poultry, fish, legumes, nuts, whole grains and dairy products) did not materially alter these associations (all P-trend<0.005; HR per each 1 serving/day increase of total red meat, unprocessed and processed red meat: 1.29 [95% CI: 1.15, 1.44], 1.25 [95% CI: 1.09, 1.43] and 1.76 [95% CI: 1.39, 2.21], respectively) (Supplementary Table 1). The analyses of specific red meat items found significant positive associations with NAFLD risk; for consumption of hamburger (P-trend=0.0001; HR: 2.03 [95% CI: 1.42, 2.91] per 1 serving/day increase), hot dogs (P-trend=0.008; HR: 3.27 [95% CI: 1.74, 6.15] per 1 serving/day increase), bacon (P-trend=0.0004; HR: 2.50 [95% CI: 1.51, 4.16] per 1 serving/day increase), and beef, pork, or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish (P-trend=0.005; HR: 1.62 [95% CI: 1.16, 2.28] per 1 serving/day) (Supplementary Table 2).

Further adjustment for updated BMI markedly attenuated the observed association of incident NAFLD, with total red meat, and with both unprocessed and processed red meat (all P-trend>0.05; Table 2). We estimated that 66.1% (95% CI: 41.8%, 84.2%, P<0.0001) of the association between total red meat and risk of incident NAFLD was mediated by BMI. Similar mediation effects were observed for both unprocessed red meat (percent mediated 73.4%, 95% CI: 39.2%, 92.2%, P<0.0001) and processed red meat (percent mediated 59.2%, 95% CI: 40.8%, 75.4%, P <0.0001). When we adjusted for updated WC instead of BMI, the observed association of incident NAFLD with total red meat and unprocessed red meat was similarly attenuated and not statistically significant (both P-trend>0.05; HR: 1.08 [95% CI: 0.97, 1.21] for total red meat; HR:1.06 [95% CI: 0.93, 1.21] for unprocessed red meat). Processed red meat intake was positively and significantly associated with NAFLD risk even after adjusting for WC (P-trend=0.039; HR: 1.27 [95% CI: 1.01, 1.60]) (Supplementary Table 3).

Tests for heterogeneity did not demonstrate effect modification according to age, BMI, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, menopausal status, or aspirin use (all P for interaction>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Red meat and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease according to strata of additional risk factors

| ≤1 serving/week | 2–4 servings/week | 5–6 servings/week | 1 serving/day | ≥2 servings/day | P for interaction1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age <60 years | 2567 | 1 (Reference) | 1.28 (0.99, 1.64) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.79) | 1.50 (1.17, 1.92) | 1.62 (1.27, 2.07) | 0.923 |

| Age ≥60 years | 563 | 1 (Reference) | 0.99 (0.63, 1.55) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.51) | 1.14 (0.72, 1.79) | 1.23 (0.78, 1.92) | |

| Body mass index | |||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 370 | 1 (Reference) | 0.94 (0.61, 1.44) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.32) | 1.10 (0.70, 1.73) | 1.14 (0.72, 1.78) | 0.289 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 916 | 1 (Reference) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.61) | 1.03 (0.71, 1.48) | 1.06 (0.72, 1.56) | 1.18 (0.81, 1.73) | |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 1844 | 1 (Reference) | 1.01 (0.72, 1.43) | 1.02 (0.73, 1.41) | 0.96 (0.68, 1.34) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.28) | |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 2558 | 1 (Reference) | 1.21 (0.96, 1.53) | 1.35 (1.08, 1.69) | 1.47 (1.16, 1.86) | 1.62 (1.29, 2.04) | 0.314 |

| Yes | 572 | 1 (Reference) | 1.08 (0.59, 1.96) | 0.95 (0.54, 1.69) | 0.97 (0.54, 1.74) | 1.00 (0.57, 1.77) | |

| Dyslipidemia | |||||||

| No | 2642 | 1 (Reference) | 1.17 (0.92, 1.47) | 1.29 (1.03, 1.61) | 1.40 (1.11, 1.77) | 1.51 (1.20, 1.89) | 0.085 |

| Yes | 488 | 1 (Reference) | 1.43 (0.78, 2.64) | 1.41 (0.78, 2.55) | 1.42 (0.77, 2.61) | 1.60 (0.88, 2.92) | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | 1168 | 1 (Reference) | 1.15 (0.81, 1.63) | 1.12 (0.80, 1.56) | 1.43 (1.01, 2.01) | 1.29 (0.92, 1.82) | 0.419 |

| Ever | 1962 | 1 (Reference) | 1.22 (0.92, 1.61) | 1.42 (1.08, 1.85) | 1.36 (1.03, 1.80) | 1.64 (1.25, 2.15) | |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| <14 MET-hours/week | 2237 | 1 (Reference) | 1.53 (1.12, 2.07) | 1.61 (1.20, 2.17) | 1.75 (1.29, 2.37) | 1.85 (1.37, 2.49) | 0.464 |

| ≥14 MET-hours/week | 893 | 1 (Reference) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.28) | 1.14 (0.85, 1.53) | 1.23 (0.89, 1.69) | 1.52 (1.11, 2.06) | |

| alcohol consumption | |||||||

| <1.5 g | 1673 | 1 (Reference) | 1.30 (0.97, 1.74) | 1.28 (0.97, 1.69) | 1.25 (0.93, 1.67) | 1.40 (1.05, 1.86) | 0.525 |

| ≥1.5 g | 1457 | 1 (Reference) | 1.15 (0.83, 1.59) | 1.37 (1.005, 1.87) | 1.63 (1.18, 2.24) | 1.66 (1.21, 2.29) | |

| Menopausal status | |||||||

| Pre | 1142 | 1 (Reference) | 1.44 (0.97, 2.12) | 1.58 (1.09, 2.30) | 1.87 (1.27, 2.75) | 1.93 (1.32, 2.82) | 0.801 |

| Post | 1988 | 1 (Reference) | 1.10 (0.85, 1.43) | 1.19 (0.93, 1.53) | 1.22 (0.94, 1.58) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | |

| Aspirin use | |||||||

| No | 1963 | 1 (Reference) | 1.09 (0.84, 1.40) | 1.18 (0.93, 1.50) | 1.29 (0.998, 1.66) | 1.38 (1.08, 1.77) | 0.289 |

| Yes | 1167 | 1 (Reference) | 1.55 (1.01, 2.38) | 1.68 (1.11, 2.54) | 1.77 (1.15, 2.71) | 1.94 (1.27, 2.96) | |

Abbreviations: MET, metabolic equivalent of tasks.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios were adjusted for smoking status (never, past, current), total calories (kcal), menopausal hormone therapy (never, past, current, premenopausal), type 2 diabetes (yes or no), hypertension (yes/no), dyslipidemia (yes or no), physical activity (MET-hours/week, quintiles), regular use of aspirin (yes/no), fruits consumption (quartiles), vegetable consumption (quartiles), and race (white or non-white).

The log likelihood ratio test was used to test for the significant of interactions.

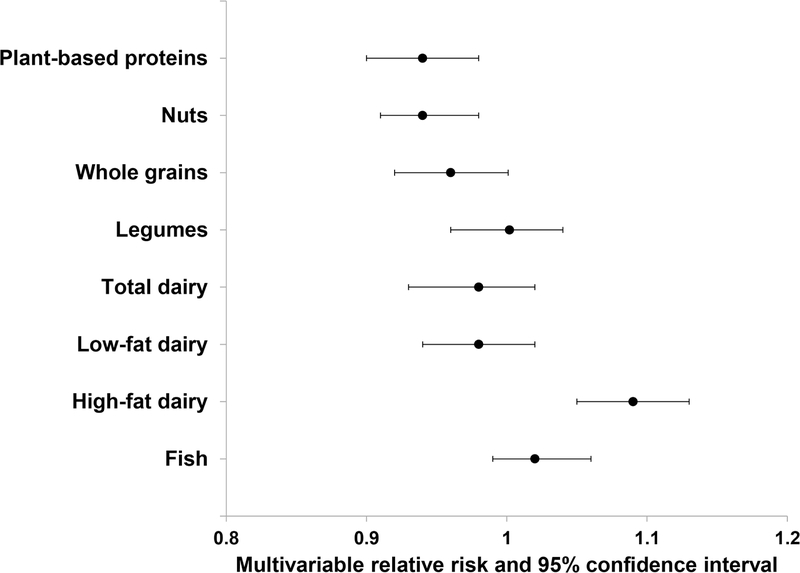

In the substitution analyses, replacing one serving of total red meat with one serving of nuts or whole grains was associated with a relative risk reduction of NAFLD; 6% for nuts (HR, 0.94; 95% CI: 0.90, 0.98), and 5% for whole grains (HR, 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.996), respectively. Replacing one serving of total red meat with one serving of plant-based proteins (combined with nuts, whole grains, and legumes) was associated with 6% relative risk reduction of NAFLD (95% CI: 0.90, 0.98). In contrast, substitution for red meat with neither legumes, low-fat dairy, high-fat dairy, total dairy nor fish were not associated with lower risk of NAFLD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relative risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with replacement of 1 serving /day of red meat with other protein sources.

Association of Nutrients of Red Meat with NAFLD

Finally, we evaluated whether the association of red meat intake with NAFLD might be explained by nutrients present at high concentrations in red meat (i.e., iron, heme iron, animal fat, cholesterol, nitrate, and palmitic acid). When both total red meat and heme iron were included in the multivariable-adjusted models, associations for red meat were attenuated (P-trend= 0.262; HR: 1.08 [95% CI: 0.95, 1.23]) (Table 4). Similarly, further adjustment for cholesterol intake also markedly attenuated the association of red meat with NAFLD risk, but the risk still remained significant (P-trend= 0.025; HR: 1.15 [95% CI: 1.02, 1.29]). In contrast, accounting for other nutrients did not materially impact our results. Heme iron and cholesterol intake were positively associated with the risk of NAFLD (all P-trend <0.0001). The multivariable adjusted HR between the highest and lowest quintiles of heme iron intake was 1.46 (95% CI: 1.28, 1.65, P-trend <0.0001). Compared to women in the lowest quintile, those in the highest quintile of cholesterol consumption had a multivariable adjusted HR of 1.49 (95% CI: 1.32, 1.69) (Supplementary Table 4). In further mediation analyses, we estimated that heme iron mediated 22.9% (95% CI: 7.3%, 52.6%) of the association between total red meat consumption and NAFLD risk, while cholesterol mediated 26.4% (95% CI: 13.8, 44.5) of the association between total red meat and NAFLD risk. When we further adjusted BMI in the mediation analysis, the mediation effect of both heme iron and cholesterol were attenuated and did not remain significant. When we further adjusted heme iron and cholesterol in the mediation analysis for red meat with NAFLD risk, the mediation effect of BMI was attenuated but maintained significance (percent mediated 16.6%, 95% CI: 0.6%, 87.7%, P=0.001 for total red meat; percent mediated 10.0.%, 95% CI: 0.4%, 77.7%, P=0.042 for unprocessed red meat; percent mediated 12.0.%, 95% CI: 4.7%, 27.5%, P<0.0001 for processed red meat).

Table 4.

Red meat consumption and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after adjusting for nutrients concentrated in red meat

| ≤1 serving/week | 2–4 servings/week | 5–6 servings/week | 1 serving/day | ≥2 servings/day | Per 1 serving/day increase | P for trend1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Red meat | 1 (Reference) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.31 (1.06, 1.61) | 1.41 (1.13, 1.75) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.89) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.46) | <0.0001 |

| Red meat adjusted for heme iron | 1 (Reference) | 1.08 (0.87, 1.36) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.34) | 1.10 (0.87, 1.39) | 1.14 (0.90, 1.45) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 0.262 |

| Red meat adjusted for iron | 1 (Reference) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.31 (1.06, 1.61) | 1.41 (1.13, 1.75) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.89) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.46) | <0.0001 |

| Red meat adjusted for animal fat | 1 (Reference) | 1.19 (0.95, 1.49) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.62) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.79) | 1.54 (1.21, 1.96) | 1.34 (1.16, 1.53) | <0.0001 |

| Red meat adjusted for cholesterol | 1 (Reference) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.39) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.42) | 1.19 (0.95, 1.50) | 1.25 (0.996, 1.56) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) | 0.025 |

| Red meat adjusted for nitrate | 1 (Reference) | 1.22 (0.98, 1.51) | 1.33 (1.08, 1.64) | 1.44 (1.16, 1.79) | 1.57 (1.26, 1.94) | 1.34 (1.20, 1.49) | <0.0001 |

| Red meat adjusted for palmitic acid | 1 (Reference) | 1.19 (0.96, 1.49) | 1.29 (1.04, 1.60) | 1.38 (1.10, 1.74) | 1.49 (1.18, 1.87) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.46) | <0.0001 |

Adjusted for smoking status (never, past, current), total calories (continuous, kcal), menopausal hormone therapy (never, past, current, premenopausal), type 2 diabetes (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no), dyslipidemia (yes or no), physical activity (MET-hours/week, quintiles), regular use of aspirin (yes/no), fruits consumption (quartiles), vegetable consumption (quartiles), and race (white or non-white).

Calculated using the median value of each meat intake category as a continuous variable.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our findings were robust after excluding anyone diagnosed with NAFLD within the first 3 years of follow-up (Supplementary Table 5). We also observed similar associations after excluding any person diagnosed with incident viral hepatitis during study follow-up (Supplementary Table 6). The risk of cirrhosis development was also associated with red meat consumption (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

In this nationwide, prospective cohort of US women, a higher intake of red meat was associated with a significant, dose-dependent increased risk of developing incident NAFLD, and this association was mediated largely by BMI. Significant excess risk was apparent with consumption of both unprocessed and processed red meat, and these associations were robust after adjusting for numerous covariates, and also after accounting for consumption of other foods. Substitution of red meat with either nuts or whole grains was associated with a significantly lower risk of NAFLD.

To our knowledge, this represents the first large-scale, prospective study to evaluate red meat consumption in relation to NAFLD risk, among women. Prior studies have established that red meat intake is associated with incident diabetes [51], cardiovascular disease [16], cancer [52], and mortality [53–55]. Two recent case control studies found a positive association between red meat intake and the risk of having NAFLD [21, 22]. In a nested case-control study from the Multiethnic cohort, red meat, processed red meat intakes were positively associated with NAFLD (both P-trend<0.05) [21]. Similarly, a recent analysis of Israeli adults found that consumption of both red meat and processed red meat were associated with increased risks of having prevalent NAFLD (odds ratio, 1.47 and 1.52, respectively) [22]. However, these studies were limited by a cross-sectional design, and diet was only assessed at a single time-point, which may introduce measurement error and misclassification [21, 22]. Thus, by leveraging a nationwide, prospective cohort study of women with detailed dietary data and repeated assessments over 20 years of long-term follow-up, the current study offers a more comprehensive assessment of long-term patterns of red meat intake in relation to NAFLD risk, among women.

In this study, red meat intake was associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of developing incident NAFLD, and this significant, positive association persisted after adjusting for multiple confounders. Moreover, our estimates were fully attenuated after further accounting for BMI, and we found that BMI mediated 66% of the relationship between red meat consumption and NAFLD risk. These findings are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that BMI partly mediates the association between red meat intake and incident diabetes [56–58], and further that intake of processed and unprocessed red meat contribute to risk of subsequent weight gain [59]. Given the established link between obesity and NAFLD [60, 61], it is therefore plausible that a diet rich in red meat contributes to weight gain and changes in adiposity, which in turn promote the development of NAFLD. Alternatively, it is also possible that BMI is both a confounder and an intermediate factor, which also could result in attenuation of risk estimates. Elevated BMI is associated both with consumption of red meat and also with the development of NAFLD. Nevertheless, our data demonstrated that a substantial portion of the association between red meat intake and NAFLD risk is in fact mediated by BMI. Future large-scale, long-term randomized controlled trials that carefully account for other potential confounders and mediators, including changes in adiposity over time, are needed to fully characterize these associations.

Lifestyle factors also can be confounders of the relationship of red meat consumption with NAFLD development. In our cohort, women who consumed more total red meat were less physically active, had unhealthier dietary pattern, consumed a greater total caloric intake, less whole grains, less plant-based proteins, less fruits, and less vegetables. Previous study also showed that those with unhealthy lifestyles consumed more red meat [62]. Given the close association of red meat intake with lifestyle patterns, it is possible that lifestyle factors confound the significant association of red meat intake with NAFLD development. However, our results were robust after adjustment for a wide spectrum of potential lifestyle confounders. Furthermore, the results were consistent when stratified analyses were applied according to various lifestyle factors.

Several potential mechanisms might explain why red meat might promote the development of NAFLD. First, red meat consumption could cause chronic low-grade systemic inflammation [63], which may contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Such inflammation may be mediated by pro-inflammatory factors such as C-reactive protein and ferritin [64], which are associated with the development of numerous related chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer [64]. Second, the gut microbiome may also mediate the link between red meat intake and NAFLD [65]. The diet, particularly red meat intake, has been shown to modulate the community structure and metabolism of colonic bacteria [66], which in turn may promote the development of NAFLD. Lastly, the constituents of processed and unprocessed red meat, including heme iron, nitrate, nitrite and their by-products, may directly influence metabolic homeostasis [67].

Strengths of this study include its prospective design, large population, high follow-up rate, repeated dietary assessments, and adjustment for a wide spectrum of lifestyle factors. In addition, the use of cumulative average red and processed meat intake increased the accuracy of long-term dietary habit data by minimizing within-person error. The prospective design of the study is a substantial strength, especially compared to the case-control study design with its potential for recall bias and inability to account for the potential influence of diagnoses or disease symptoms on dietary choices. Furthermore, unlike prior studies that used a non-validated food questionnaire to collect dietary information that did not control for total energy intake, we adjusted for total calorie intake, which minimizes correlational errors and decreases between-person variation [68].

This study also had several limitations. First, the ascertainment of NAFLD was based on self-report. In addition, we lacked information regarding the method of diagnosis of fatty liver and whether participants were screened for fatty liver. As our previous study using same cohort [69], many participants may not be aware of underlying NAFLD due to lack of systematic screening, thus, under-ascertainment of cases may be possible. In turn, the prevalence of NAFLD estimated in this study was much lower than that from studies where every participant underwent an ultrasound examination [70]. This under-ascertainment of NAFLD cases may influence differentially on the results according to the presence of obesity. NAFLD can be screened preferentially in individuals with obesity. In contrast, NAFLD patients with normal weight could not be diagnosed until they have liver enzyme elevations or metabolic abnormalities. Validation using liver imaging or histological data was lacking in our current study. Our results should be validated in the cohort with ultrasound or histology data. Second, we lacked detailed information regarding NAFLD fibrosis stages due to lack of histologic data or laboratory information for calculating non-invasive fibrosis markers. Advanced liver fibrosis is the most relevant predictor of long-term outcomes in NAFLD patients [71]. Lack of liver histology also precluded us from ascertaining nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Further research will be needed to assess the association of red meat consumption and NAFLD fibrosis severity, particularly since poor outcome of NAFLD is linked to the extent to which components of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis evolve within the context of NAFLD. Third, while reverse causation is possible, our results were similar in analyses that included long durations of elapsed time between exposure assessment and the development of NAFLD. Fourth, anthropometric measurements were also self-reported or recalled; however, the validity and high reproducibility of these measurements has previously been established [39, 72]. Fifth, it would be helpful to assess critical window of time in which red meat exposure might most accurately predict the development of NAFLD. Our data using the cumulative consumption of red meat as an exposure could not investigate this association. Further study is warranted to address this issue to clearly show the causal effect of red meat consumption on NAFLD development. Sixth, we could not further analyze the association of cooking methods of red meat with NAFLD risk because data on the cooking methods of red meat are not sufficient in our cohort. Meat cooking with high temperature can increase the levels of hazard chemicals [73, 74]. Previous study reported that open-flame and/or high-temperature cooking for red meat is associated with an increased risk of diabetes [75]. Further comprehensive study about the association between cooking methods of red meat and NAFLD risk is warranted. Finally, our participants were female health professionals, and most were white, underscoring the need for additional prospective studies in more diverse populations of both men and women. However, we would highlight that this likely minimizes the risk of confounding by socioeconomic status or ethnicity.

In conclusion, within a nationwide, prospective cohort of U.S. women, higher intake of red meat, including both processed and unprocessed red meat, contributed to a significant, dose-dependent increased risk of developing incident NAFLD, and this association was largely mediated by obesity. Identifying modifiable dietary factors for the prevention of NAFLD are critical to help reduce the growing burden of NAFLD among at-risk adults. Public health efforts focused on the prevention of NAFLD should consider encouraging diets that minimize red meat consumption as part of a general strategy to address obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support

UM1 CA186107 (Nurses’ Health Study infrastructure grant)

K24 DK 098311 (ATC)

K23 DK122104 (TGS)

ATC is a Stuart and Suzanne Steele MGH Research Scholar

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- HR

hazard ratio

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- WC

waist circumference

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Chan has previously served as a consultant for Bayer Pharma AG, Pfizer Inc., and Boehringer Ingelheim for work unrelated to this manuscript. Dr. Simon has previously served as a consultant for Aetion, for work unrelated to this manuscript. The remaining authors have no disclosures and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2013;10:686–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Malik SM, deVera ME, Fontes P, Shaikh O, Ahmad J. Outcome after liver transplantation for NASH cirrhosis. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9:782–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yoo JJ, Kim W, Kim MY, Jun DW, Kim SG, Yeon JE, et al. Recent research trends and updates on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical and molecular hepatology. 2019;25:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tariq R, Axley P, Singal AK. Extra-Hepatic Manifestations of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Review. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2020;10:81–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, McCall S, Bruchette JL, Diehl AM, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of hepatology. 2008;48:993–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yasutake K, Nakamuta M, Shima Y, Ohyama A, Masuda K, Haruta N, et al. Nutritional investigation of non-obese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the significance of dietary cholesterol. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2009;44:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of hepatology. 2016;64:1388–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Recaredo G, Marin-Alejandre BA, Cantero I, Monreal JI, Herrero JI, Benito-Boillos A, et al. Association between Different Animal Protein Sources and Liver Status in Obese Subjects with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Fatty Liver in Obesity (FLiO) Study. Nutrients. 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Battaglia Richi E, Baumer B, Conrad B, Darioli R, Schmid A, Keller U. Health Risks Associated with Meat Consumption: A Review of Epidemiological Studies. International journal for vitamin and nutrition research Internationale Zeitschrift fur Vitamin- und Ernahrungsforschung Journal international de vitaminologie et de nutrition. 2015;85:70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hernandez EA, Kahl S, Seelig A, Begovatz P, Irmler M, Kupriyanova Y, et al. Acute dietary fat intake initiates alterations in energy metabolism and insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2017;127:695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bjermo H, Iggman D, Kullberg J, Dahlman I, Johansson L, Persson L, et al. Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat, lipoproteins, and inflammation in abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;95:1003–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wouters K, van Gorp PJ, Bieghs V, Gijbels MJ, Duimel H, Lutjohann D, et al. Dietary cholesterol, rather than liver steatosis, leads to hepatic inflammation in hyperlipidemic mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2008;48:474–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Iwamoto K, Arihiro K, Takeuchi M, Sato T, et al. Elevated levels of serum advanced glycation end products in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2007;22:1112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim Y, Keogh J, Clifton P. A review of potential metabolic etiologies of the observed association between red meat consumption and development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2015;64:768–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121:2271–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fretts AM, Follis JL, Nettleton JA, Lemaitre RN, Ngwa JS, Wojczynski MK, et al. Consumption of meat is associated with higher fasting glucose and insulin concentrations regardless of glucose and insulin genetic risk scores: a meta-analysis of 50,345 Caucasians. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2015;102:1266–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mozaffarian D Dietary and Policy Priorities for Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and Obesity: A Comprehensive Review. Circulation. 2016;133:187–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cocate PG, Natali AJ, de Oliveira A, Alfenas Rde C, Peluzio Mdo C, Longo GZ, et al. Red but not white meat consumption is associated with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and lipid peroxidation in Brazilian middle-aged men. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2015;22:223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Belinova L, Kahleova H, Malinska H, Topolcan O, Vrzalova J, Oliyarnyk O, et al. Differential acute postprandial effects of processed meat and isocaloric vegan meals on the gastrointestinal hormone response in subjects suffering from type 2 diabetes and healthy controls: a randomized crossover study. PloS one. 2014;9:e107561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Noureddin M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wilkens LR, Porcel J, Boushey CJ, Le Marchand L, et al. Diet Associations With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in an Ethnically Diverse Population: The Multiethnic Cohort. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2020;71:1940–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zelber-Sagi S, Ivancovsky-Wajcman D, Fliss Isakov N, Webb M, Orenstein D, Shibolet O, et al. High red and processed meat consumption is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Journal of hepatology. 2018;68:1239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schlesinger S, Neuenschwander M, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Bechthold A, Boeing H, et al. Food Groups and Risk of Overweight, Obesity, and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2019;10:205–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rouhani MH, Salehi-Abargouei A, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. Is there a relationship between red or processed meat intake and obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2014;15:740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;313:2263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ikejima K, Kon K, Yamashina S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcohol-related liver disease: From clinical aspects to pathophysiological insights. Clinical and molecular hepatology. 2020;26:728–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. Jama. 2011;306:1884–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, Adams LA, Bjornsson ES, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389–97.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu PH, Burke KE, Ananthakrishnan AN, Lochhead P, Olen O, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Obesity and Weight Gain Since Early Adulthood Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Microscopic Colitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;17:2523–32.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chalasani N, Younossi Z. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. 2018;67:328–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, et al. Relative Validity of Nutrient Intakes Assessed by Questionnaire, 24-Hour Recalls, and Diet Records as Compared With Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. American journal of epidemiology. 2018;187:1051–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, et al. Validity of a Dietary Questionnaire Assessed by Comparison With Multiple Weighed Dietary Records or 24-Hour Recalls. American journal of epidemiology. 2017;185:570–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. International journal of epidemiology. 1989;18:858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1999;69:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yamamoto A, Harris HR, Vitonis AF, Chavarro JE, Missmer SA. A prospective cohort study of meat and fish consumption and endometriosis risk. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;219:178.e1–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology. 1996;7:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;122:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 1990;1:466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. International journal of epidemiology. 1994;23:991–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Higuchi LM, Khalili H, Chan AT, Richter JM, Bousvaros A, Fuchs CS. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107:1399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kim MN, Lo CH, Corey KE, Liu PH, Ma W, Zhang X, et al. Weight gain during early adulthood, trajectory of body shape and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective cohort study among women. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2020;113:154398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McCullough ML, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Hu FB, et al. Diet quality and major chronic disease risk in men and women: moving toward improved dietary guidance. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2002;76:1261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. The Journal of nutrition. 2012;142:1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Stason WB, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, et al. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. American journal of epidemiology. 1987;126:319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:1596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Fuchs C, Rosner BA, et al. Multivitamin use, folate, and colon cancer in women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Annals of internal medicine. 1998;129:517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:207–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Rosner BA, Spiegelman D, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;149:531–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tobias DK, Hu FB, Chavarro J, Rosner B, Mozaffarian D, Zhang C. Healthful dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:1566–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Willett WC, et al. Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;94:1088–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zheng W, Lee SA. Well-done meat intake, heterocyclic amine exposure, and cancer risk. Nutrition and cancer. 2009;61:437–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fraser GE. Associations between diet and cancer, ischemic heart disease, and all-cause mortality in non-Hispanic white California Seventh-day Adventists. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1999;70:532s–8s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Key TJ, Fraser GE, Thorogood M, Appleby PN, Beral V, Reeves G, et al. Mortality in vegetarians and nonvegetarians: detailed findings from a collaborative analysis of 5 prospective studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1999;70:516s–24s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Sinha R, Cross AJ, Graubard BI, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A. Meat intake and mortality: a prospective study of over half a million people. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Malik VS, Li Y, Tobias DK, Pan A, Hu FB. Dietary Protein Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women. American journal of epidemiology. 2016;183:715–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].van Nielen M, Feskens EJ, Mensink M, Sluijs I, Molina E, Amiano P, et al. Dietary protein intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: the EPIC-InterAct Case-Cohort Study. Diabetes care. 2014;37:1854–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Tinker LF, Sarto GE, Howard BV, Huang Y, Neuhouser ML, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, et al. Biomarker-calibrated dietary energy and protein intake associations with diabetes risk among postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;94:1600–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].O’Brien J, Powell LW. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: is iron relevant? Hepatology international. 2012;6:332–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, Willett WC, Longo VD, Chan AT, et al. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176:1453–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BM. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107:1486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ley SH, Sun Q, Willett WC, Eliassen AH, Wu K, Pan A, et al. Associations between red meat intake and biomarkers of inflammation and glucose metabolism in women. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;99:352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ma J, Zhou Q, Li H. Gut Microbiota and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Insights on Mechanisms and Therapy. Nutrients. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Etemadi A, Sinha R, Ward MH, Graubard BI, Inoue-Choi M, Dawsey SM, et al. Mortality from different causes associated with meat, heme iron, nitrates, and nitrites in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study: population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;357:j1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].WillettW. Nutritional Epidemiology2. Oxford University, Inc. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kim MN, Lo CH, Corey KE, Liu PH, Ma W, Zhang X, et al. Weight Gain during Early Adulthood, Trajectory of Body Shape and the Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study among Women. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2020:154398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2016;64:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Hammar U, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, et al. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. Journal of hepatology. 2017;67:1265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Knize MG, Salmon CP, Pais P, Felton JS. Food heating and the formation of heterocyclic aromatic amine and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mutagens/carcinogens. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999;459:179–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Knize MG, Dolbeare FA, Carroll KL, Moore DH 2nd, Felton JS. Effect of cooking time and temperature on the heterocyclic amine content of fried beef patties. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 1994;32:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Liu G, Zong G, Wu K, Hu Y, Li Y, Willett WC, et al. Meat Cooking Methods and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Results From Three Prospective Cohort Studies. Diabetes care. 2018;41:1049–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.