Abstract

Photosynthetic organisms are exposed to various environmental sources of oxidative stress. Land plants have diverse mechanisms to withstand oxidative stress, but how microalgae do so remains unclear. Here, we characterized the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor BLZ8, which is highly induced by oxidative stress. Oxidative stress tolerance increased with increasing BLZ8 expression levels. BLZ8 regulated the expression of genes likely involved in the carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM): HIGH-LIGHT ACTIVATED 3 (HLA3), CARBONIC ANHYDRASE 7 (CAH7), and CARBONIC ANHYDRASE 8 (CAH8). BLZ8 expression increased the photosynthetic affinity for inorganic carbon under alkaline stress conditions, suggesting that BLZ8 induces the CCM. BLZ8 expression also increased the photosynthetic linear electron transfer rate, reducing the excitation pressure of the photosynthetic electron transport chain and in turn suppressing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production under oxidative stress conditions. A carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, ethoxzolamide, abolished the enhanced tolerance to alkaline stress conferred by BLZ8 overexpression. BLZ8 directly regulated the expression of the three target genes and required bZIP2 as a dimerization partner in activating CAH8 and HLA3. Our results suggest that a CCM-mediated increase in the CO2 supply for photosynthesis is critical to minimize oxidative damage in microalgae, since slow gas diffusion in aqueous environments limits CO2 availability for photosynthesis, which can trigger ROS formation.

The Chlamydomonas bZIP transcription factor BLZ8 induces the carbon-concentrating mechanism to provide an electron sink pathway, reducing reactive oxygen species production under oxidative stress

Introduction

Photosynthetic organisms are continuously exposed to stresses from the natural environment, and the effects of these stresses often severely inhibit biomass production. Much attention has been directed toward understanding how photosynthetic organisms withstand stresses (Chan et al., 2016; Zhu, 2016) such as high light, alkaline pH, low or high temperatures, high salinity, and nutrient deficiencies, which all trigger reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Liu et al., 2007; Erickson et al., 2015; You and Chan, 2015). Under stress conditions, ROS accumulate within chloroplasts as a consequence of harvesting light energy during photosynthesis, which involves the movement of electrons within the electron transport chain. Multiple ROS are generated when electron transfer is disrupted, including singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide (O2−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Asada, 1999; Erickson et al., 2015). The excessive accumulation of ROS in chloroplasts damages many cellular structures and enzymes (Apel and Hirt, 2004). Thus, photosynthetic organisms deploy multiple mechanisms to minimize ROS generation and scavenge existing ROS.

To minimize ROS formation, photosynthetic organisms dissipate the energy of stray electrons within chloroplasts and tightly regulate the flow of electrons. For example, nonphotochemical quenching dissipates excess light energy reaching photosystem II (PSII) (Müller et al., 2001). Several O2-reducing pathways, including the water–water cycle and chlororespiration, quench energetic electrons generated by PSI and PSII (Asada, 1999; Cournac, 2002; Chaux et al., 2017). Photorespiration can also function as an electron outlet through which energetic electrons are photochemically quenched (Kozaki and Takeba, 1996). Rubisco fixes CO2 to operate the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, consuming photosynthetically derived energetic electrons and thereby providing another electron sink (Saroussi et al., 2019). To scavenge toxic ROS generated from the overflow of energetic electrons along the electron transport chain, chloroplasts are equipped with several ROS detoxification pathways, including enzymatic (involving superoxide dismutase, catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, and peroxiredoxin) and nonenzymatic (involving ascorbate and glutathione) antioxidant defense mechanisms (Waszczak et al., 2018).

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying plastid oxidative stress responses in microalgae is rudimentary compared to our understanding of such mechanisms in terrestrial plants. Although some stress response mechanisms might be shared between terrestrial plants and microalgae, since they are both photosynthetic organisms, differences are also likely to exist since they live in very different environments. Several genes mediate oxidative stress responses in the unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii), including genes that trigger singlet oxygen responses (Fischer et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2013; Wakao et al., 2014). In addition, the cytoplasmic protein kinase MUTANTS AFFECTING RETROGRADE SIGNALING1 is essential for mitigating photooxidative stress (Perlaza et al., 2019).

In this study, we identified a bZIP transcription factor, BLZ8, as an important factor contributing to tolerance to several ROS-inducing environmental stresses in Chlamydomonas. Furthermore, we identified three BLZ8 target genes: HLA3, encoding a bicarbonate transporter involved in the carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM), and two carbonic anhydrase (CA) genes, CAH7 and CAH8, likely also involved in the CCM. Our experiments support roles for these target genes in oxidative stress tolerance, establishing that the CCM contributes to oxidative stress tolerance. We provide supporting genetic, biochemical, and physiological evidence for the role of the CCM in oxidative stress responses and discuss its unique importance in stress tolerance of photosynthetic organisms living in an aqueous environment.

Results

Chlamydomonas BLZ8 is highly induced under oxidative stress

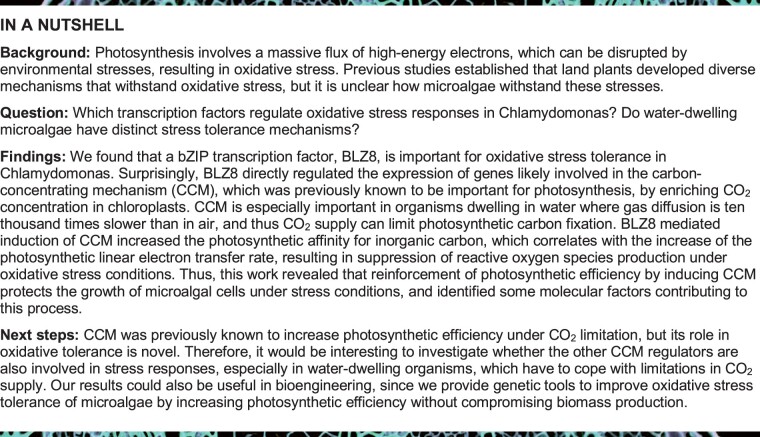

bZIP transcription factors participate in diverse stress responses throughout the plant kingdom (Nijhawan et al., 2008; Dröge-Laser et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2020). The Chlamydomonas genome encodes 19 bZIP transcription factors (Yamaoka et al., 2019). To identify which of the bZIP transcription factors might be involved in oxidative stress responses, we performed an RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of cells exposed to 5-mM metronidazole (Met), which triggers the production of H2O2 in chloroplasts (Schmidt et al., 1977). We detected expression of 17,741 Chlamydomonas genes (Supplemental Data Set S1); among the genes encoding bZIP transcription factors, three were highly upregulated in response to Met treatment: Cre05.g238250 (bZIP1), Cre12.g501600 (BLZ8), and Cre17.g746547 (bZIP2) (Figure 1A). We previously reported that bZIP1 is important for the lipid remodeling that protects cells during endoplasmic reticulum stress (Yamaoka et al., 2019). We thus selected BLZ8 for further characterization. We validated the induction of BLZ8 transcript levels by Met using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

BLZ8 transcript levels increase under oxidative stress conditions in Chlamydomonas. A, TPM values of bZIP transcription factor genes in Chlamydomonas after treatment with 5 mM Met. Dots: single data points; Bars: means of the two data points. B, Fold change in BLZ8 transcript levels in the parental strain CC-4533 at 1 h after treatment with 5 mM Met, high light stress (750 μmol photons·m−2·s−1), or alkaline stress (pH 8.5). BLZ8 transcript levels are normalized to the housekeeping gene CBLP; fold difference relative to the control are presented. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P <0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N = 4.

If BLZ8 globally mediates responses to oxidative stress, its expression might increase under various oxidative stress conditions such as alkaline stress and high light stress, which trigger ROS production in algal cells (Liu et al., 2007; Erickson et al., 2015). Indeed, BLZ8 expression increased 1.7- and 1.9-fold under high light stress and alkaline stress, respectively, relative to control cultures (Figure 1B), suggesting that BLZ8 functions in oxidative stress responses.

BLZ8 expression levels correspond with cell growth under oxidative stress

To dissect the function of BLZ8, we used one Chlamydomonas strain overexpressing BLZ8 (BLZ8 OX) and one blz8 knockdown mutant strain (blz8-1). BLZ8 OX was part of the CLiP library (Li et al., 2016), and blz8-1 was isolated from the random insertional mutant library derived from the C9 Chlamydomonas strain following a previously described protocol (Yamano et al., 2015). blz8-1 had an APHVII cassette inserted into the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of BLZ8 (Supplemental Figure S1A) that reduced BLZ8 transcript levels to 1.8% that of the parental strain C9 (Supplemental Figure S1B). BLZ8 OX harbored an APHVIII cassette in the BLZ8 3′-UTR (Supplemental Figure S1A), which increased BLZ8 transcript level 2.9-fold compared to its parental strain, CC-4533 (Supplemental Figure S1C), for an unknown reason.

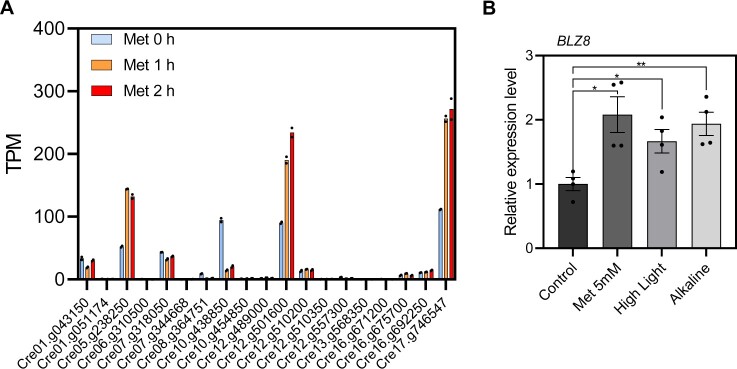

To test whether altered BLZ8 expression levels affect oxidative stress tolerance in Chlamydomonas, we examined the growth of parental, blz8-1, and BLZ8 OX cells exposed to ROS-inducing chemicals (Figure 2A). Under control conditions, we observed no clear difference in growth between BLZ8 OX, blz8-1, and their respective parental strains. However, in the presence of organic tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBOOH), which facilitates the production of peroxyl and alkoxyl radicals, and H2O2-inducing Met, the BLZ8 OX strain grew better than CC-4533, while blz8-1 was more sensitive to these chemicals compared to C9. In contrast, all strains exhibited comparable growth in the presence of the 1O2-inducing chemicals neutral red and Rose Bengal (Supplemental Figure S2). These results indicate that BLZ8 expression correlates with the tolerance of Chlamydomonas cells to H2O2 and tBOOH.

Figure 2.

BLZ8 overexpression improves while loss of BLZ8 limits growth under oxidative stress conditions. A, Quantitative analyses of the oxidative stress tolerance of BLZ8 OX and blz8-1 in comparison with their parental strains. Chlamydomonas cell cultures were subjected to 2-fold serial dilutions, exposed to the indicated ROS-inducing chemicals for 24 h in liquid cultures, and subsequently spotted on TAP agar plates for recovery at 25°C under continuous illumination at 80-μmol photons·m−2·s−1. B, Growth of cells spotted onto TAP plates and exposed to continuous illumination of high light (750 μmol photons·m−2·s−1). Cell densities were reduced to half in series, as indicated on the left under OD730 nm. C, Representative photographs (upper) and chlorophyll content (per mL of culture) (lower) of Chlamydomonas cultures first grown in TAP medium pH 7.0 and then transferred to and cultured in AMPSO-acetate phosphate medium (pH 9.0) for the indicated days. Data are shown as the mean ± sem; N = 3. D, Lipid peroxidation levels in the parental strain C9 and the blz8-1 mutant under alkaline stress conditions. MDA equivalents were measured from whole cells. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N = 3.

Next, we evaluated the growth of BLZ8 OX and blz8-1 under two ROS-inducing abiotic stress conditions: high light (750-μmol photons·m−2·s−1) and alkaline pH (pH 9.0). When exposed to high light stress, BLZ8 OX grew faster than CC-4533, while the blz8-1 mutant showed reduced growth compared to C9 (Figure 2B). Under alkaline stress conditions, both BLZ8 OX and CC-4533 had decreased chlorophyll contents on the first day, but their recovery thereafter differed; BLZ8 OX exhibited higher chlorophyll content than CC-4533 (Figure 2C, left). In contrast, blz8-1 cells had lower levels of chlorophyll than C9 (Figure 2C, right). Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, a marker of oxidative stress and indicator of lipid peroxidation, were three-fold higher in blz8-1 compared to C9 when the cells were grown at alkaline pH (Figure 2D). These results indicate that BLZ8 confers tolerance to the two abiotic stresses.

We next tested whether the oxidative stress phenotypes of blz8-1 and BLZ8 OX were due to the altered expression of BLZ8. First, we introduced a genomic copy of BLZ8 into blz8-1 to generate a complementation strain, designated blz8-1(BLZ8) (Supplemental Figure S1B). Under oxidative stress conditions, the growth of blz8-1(BLZ8) was comparable to that of C9, indicating that BLZ8 fully complemented the blz8-1 mutant (Figure 2, A–C). Second, we conducted a tetrad analysis from a cross between BLZ8 OX and CC-5155, an isogenic strain of CC-4533 of opposite mating type, to test whether there was co-segregation between the higher stress tolerance seen in BLZ8 OX and the selection cassette inserted at BLZ8. The 24 progenies obtained from six full tetrads segregated in a 2:2 ratio when tested for paromomycin antibiotic resistance (Supplemental Figure S1D), indicating the insertion of a single APHVIII cassette in the genome of BLZ8 OX. All antibiotic-resistant progenies grew better than antibiotic-sensitive progenies in medium containing paraquat (Supplemental Figure S1D), indicating that the insertion of the paromomycin resistance gene was responsible for the oxidative stress tolerance seen in BLZ8 OX. Together, these results indicate that changes in BLZ8 expression modulate oxidative stress tolerance.

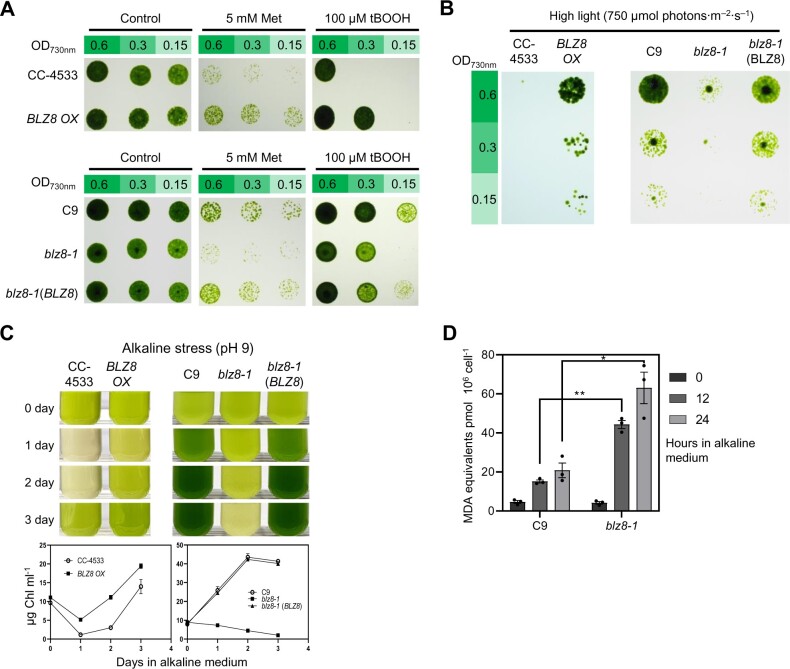

BLZ8 regulates the expression of oxidative stress-responsive genes

To decipher the molecular mechanism of BLZ8 function, we explored the transcriptome of BLZ8 OX and CC-4533 cells grown with 5 mM Met by RNA-seq for 1 or 2 h (Supplemental Data Set S1). Sample correlation and principal component analysis (PCA) of all samples revealed that the two replicates of RNA-seq analysis were highly reproducible (Supplemental Figure S3). We identified 4,940 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between BLZ8 OX and CC-4533. Among those, 1,441 and 1,103 DEGs were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in BLZ8 OX at all time points (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Expression levels of oxidative stress-responsive genes are altered in BLZ8 OX and blz8-1. A, Venn diagram representing upregulated and downregulated DEGs in BLZ8 OX compared to its parental strain CC-4533 before (0 h) and 1 and 2 h into treatment with 5 mM Met. B, GO analysis of upregulated DEGs in BLZ8 OX using REVIGO. The 640 Arabidopsis genes homologous to the 1,441 Chlamydomonas genes were used for GO analysis. The size of each rectangle within the treemap was adjusted to reflect the absolute log10 P-value of each GO term. C, Relative expression levels of oxidative stress-responsive genes, as determined by RT-qPCR. Cells were grown in TAP medium pH 7.0 and then transferred to HEPES-acetate phosphate medium pH 8.5 for 2 h. Transcript levels are normalized to the housekeeping gene CBLP. Presented values are fold difference from the value at 0 h in the C9 strain under the same experimental conditions. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N = 4.

To identify cellular processes regulated by BLZ8, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using annotations associated with Arabidopsis thaliana homologs of these DEGs (Supplemental Data Set S2). Genes preferentially upregulated in BLZ8 OX were associated with chloroplast activities including pigment biosynthesis, carbohydrate derivative biosynthesis, tetrapyrrole metabolism, photosynthesis light reaction, and plastid organization. Genes involved in responses to light stimulus, such as response to abiotic stimulus, were enriched as well (Figure 3B). The downregulation of many genes involved in chloroplast functions in CC-4533 upon Met treatment (Supplemental Data Set S2) is consistent with previous transcriptome data in response to H2O2 (Blaby et al., 2015). The most highly enriched GO terms among downregulated genes were non-coding RNA metabolism and ribosome biosynthesis (Supplemental Figure S4).

To identify the oxidative stress-responsive genes directly regulated by BLZ8, we first focused on 84 genes that belong to the “response to abiotic stimulus” GO category in Figure 3B (Supplemental Data Set S2). Among the 84 genes, we selected 6 candidate genes (Supplemental Table S1) that have been described as being involved in oxidative stress responses. Next, we compared the expression levels of the candidate genes between C9 and blz8-1 under alkaline stress conditions by RT-qPCR, reasoning that genuine BLZ8 targets would be expressed at lower levels in blz8-1 compared to C9 under oxidative stress conditions. Four of the six genes satisfied this criterion: PLASTOQUINOL OXIDASE1 (PTOX1), METHIONINE SULFOXIDE REDUCTASE2 (MSRA2), PEROXIREDOXIN1 (PRX1), and CAH8 (Figure 3C).

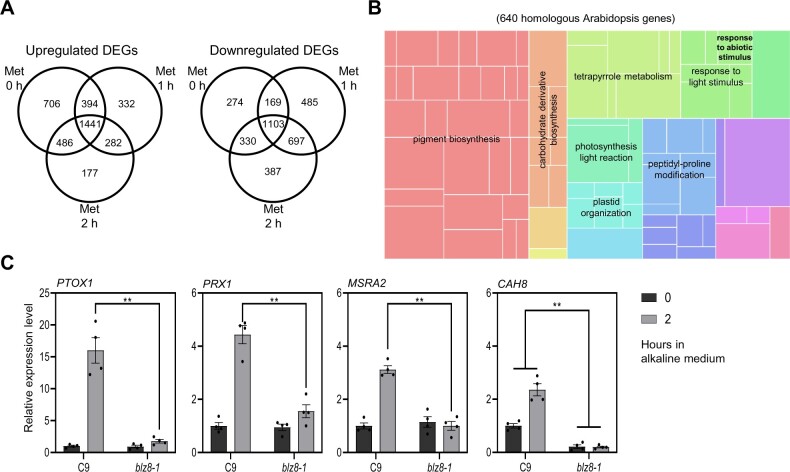

BLZ8 induces the CCM to enhance alkaline stress tolerance

Among the four candidate genes was CAH8, encoding CA (Ynalvez et al., 2008). Because several CAs, for example CAH3 and low-CO2-inducible protein B, play critical roles in the CCM in Chlamydomonas (Yamano et al., 2010; Fukuzawa et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2016), CAH8 might also participate in the CCM (Moroney et al., 2011). Moreover, CAH7, encoding CA, and HLA3, encoding an ABC-type bicarbonate transporter located at the plasma membrane, were among the upregulated DEGs in BLZ8 OX (Supplemental Data Set S2), suggesting that CCM components might be BLZ8 target genes.

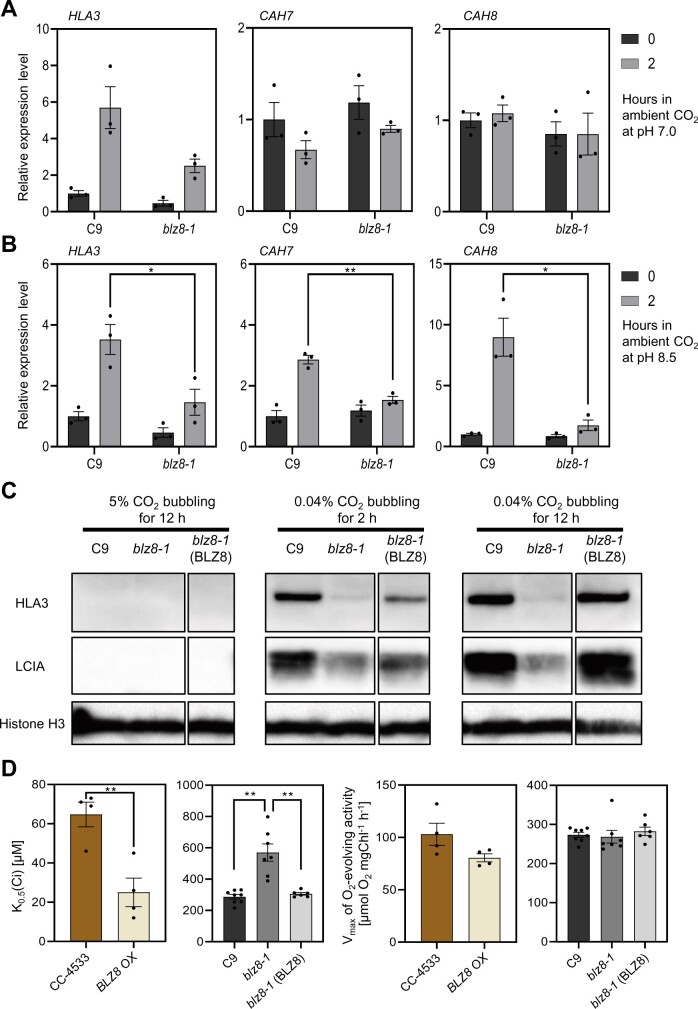

To test this possibility, we compared transcript levels of HLA3, CAH7, and CAH8 in the blz8-1 and C9 strains under two CO2-deprived conditions. Under ambient CO2 levels (0.04% CO2) and normal pH (7.0), conditions that induce the expression of CCM-related genes (Miura et al., 2004), HLA3 transcript levels were lower in blz8-1 relative to C9, while those of CAH7 and CAH8 did not differ between the two strains (Figure 4A). When alkaline stress was combined with ambient CO2, the expression levels of HLA3, CAH7, and CAH8 were significantly lower in blz8-1 than in C9 (Figure 4B). Together, these results indicate that BLZ8 induces the expression of these CCM-related genes under oxidative stress conditions and ambient CO2 levels. Thus, we hypothesized that CCM induction might be one of the mechanisms by which BLZ8 enhances oxidative stress tolerance in Chlamydomonas cells.

Figure 4.

BLZ8 increases photosynthetic Ci affinity. A and B, Relative expression levels of BLZ8 target genes after a shift in CO2 concentration and a change in medium pH, as determined by RT-qPCR. Cells grown in MOPS·P medium (pH 7.0) under high CO2 conditions (5%) were transferred to either the same medium (A) or HEPES·P medium (pH 8.5) (B) under ambient CO2 conditions (0.04%) and incubated for 2 h. Transcript levels are normalized to the housekeeping gene CBLP. Presented values are fold difference from the value at 0 h in the C9 strain under the same experimental conditions. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N = 3. C, Immunoblot analysis of the HLA3 and LCIA protein levels in blz8-1, its parental strain C9, and the blz8-1(BLZ8) strain. Cells were grown under either 5% CO2 or 0.04% CO2 at pH 7.0 for the indicated times. Proteins were extracted from cells and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Histone H3 was used as a loading control. D, Photosynthetic affinity against Ci and maximum photosynthetic O2 evolution activity of CC-4533, BLZ8 OX, C9, blz8-1, and blz8-1(BLZ8) strains grown in MOPS·P medium (pH 7.0) under ambient CO2. Photosynthetic O2-evolving activity was measured at pH 9.0. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N ≥ 4.

To test whether BLZ8 activates the CCM, we first examined levels of proteins in the central cooperative bicarbonate uptake system in the Chlamydomonas CCM, the transporters HLA3 and LCIA, because CCM activity is correlated with protein levels of CCM components (Duanmu et al., 2009; Yamano et al., 2015). HLA3 and LCIA accumulated to lower levels in blz8-1 relative to C9 but returned to the levels seen in the parental strain in blz8-1(BLZ8) under ambient CO2 at pH 7.0 (Figure 4C). Next, we measured photosynthetic O2-evolving activity and evaluated the photosynthetic affinity against inorganic carbon (Ci) by calculating K0.5 (Ci) values, the Ci concentration required for half-maximal photosynthetic O2-evolving activity, under alkaline stress (pH 9.0). BLZ8 OX had a K0.5 (Ci) value that was 39% that of CC-4533, while K0.5 (Ci) was twice as high in blz8-1 as in C9 (Figure 4D, left). These results indicated that BLZ8 overexpression improved Ci affinity, while the blz8 mutation lowered it. The decreased Ci affinity seen in blz8-1 was restored in blz8-1(BLZ8) (Figure 4D, left).

The maximum rates of O2-evolving activity were comparable among all strains tested (Figure 4D, right), indicating that altered BLZ8 expression did not alter overall photosynthetic capacity. To test whether the Ci affinity of each strain correlated with its stress tolerance capacity, we evaluated cell growth under the same experimental conditions used to measure Ci affinity and determined that BLZ8 OX recovered faster from the transfer to alkaline pH than did CC-4533, whereas blz8-1 did not recover (Supplemental Figure S5). These results indicate that BLZ8 induces components of the CCM, thereby enhancing oxidative stress tolerance of Chlamydomonas cultures.

BLZ8 reduces the excitation pressure of the photosynthetic electron transport chain and formation of ROS

Previous reports suggested that low CCM activity decreases photosynthetic electron transfer, resulting in the accumulation of energetic electrons in the electron transport chain, which in turn triggers the production of ROS (Caspari et al., 2017; Shimakawa et al., 2017; Saroussi et al., 2019). Since BLZ8 increases the CO2 supply for photosynthesis by inducing the CCM under alkaline stress conditions (Figure 4), we suspected that it might prevent the overreduction of the electron transport chain, suppressing the formation of ROS.

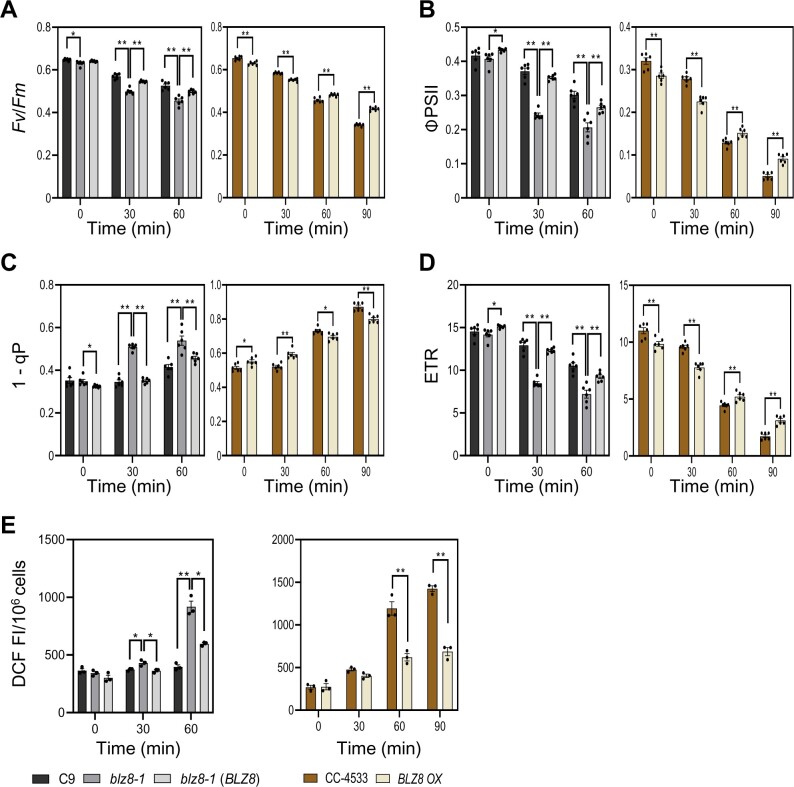

To test this possibility, we analyzed PSII photochemistry and intracellular ROS levels after exposing cells to alkaline stress under ambient CO2 (Figure 5). The maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) and the photochemical quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) were significantly lower in blz8-1 than in C9 and blz8-1(BLZ8) (Figure 5, A and B). To estimate the redox state of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool of each cell strain, the proportion of the closed PSII reaction center (1-qP) was measured. The PQ pool was more reduced in blz8-1 than in C9 and blz8-1(BLZ8) (Figure 5C), suggesting that the photosynthetic electron transport chain was overreduced in blz8-1. Finally, blz8-1 had a lower electron transfer rate (ETR) than C9 and blz8-1(BLZ8) (Figure 5D), which correlated positively with the reduced photosynthetic Ci affinity of blz8-1 compared with C9 and blz8-1(BLZ8) (Figure 4D). Conversely, overexpression of BLZ8 increased the quantum yield of PSII and ETR (Figure 5, A, B, and D) and decreased the excitation pressure on the electron transport chain (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

BLZ8 expression reduces excitation pressure of the photosynthetic electron transport chain and suppresses ROS production. To impose alkaline stress conditions, cells grown in MOPS·P medium (pH 7.0) under high CO2 conditions (5%) were transferred to AMPSO·P medium (pH 9.0) under ambient CO2 conditions (0.04%). Photochemical quenching parameters, Fv/Fm (A), ΦPSII (B), 1–qP (C), ETR (D), and intracellular ROS content (E) were determined at the indicated time points. Data are shown as mean ± sem; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test); N ≥ 3.

We then tested whether the ROS levels differed between the cell strains under the same conditions. To measure intracellular ROS levels, we stained cells with CM-H2DCFDA. The ROS content was significantly higher in blz8-1 than in C9 and blz8-1(BLZ8), whereas it was lower in BLZ8 OX than in CC-4533 (Figure 5E). These results suggest that induction of CCM by BLZ8 provided an electron sink pathway that reduced the excitation pressure of the electron transport chain, which in turn suppressed ROS formation.

Inhibiting CA activity in BLZ8 OX abolishes enhanced tolerance to alkaline stress

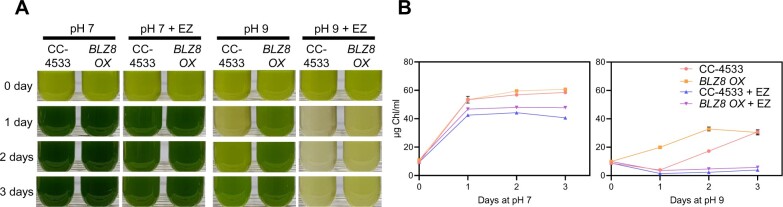

To examine the contribution of CAH7 and CAH8 to BLZ8-mediated oxidative tolerance, we employed ethoxzolamide (EZ), a membrane-permeable CA inhibitor (Moroney et al., 1985). While BLZ8 OX recovered growth faster than CC-4533 when transferred to high pH, the addition of EZ to the medium completely abolished this effect (Figure 6), revealing that, in the absence of CA activity, BLZ8 overexpression does not protect cells from alkaline stress. This effect was specific to alkaline stress, as EZ did not induce a dramatic decrease in growth of BLZ8 OX or CC-4533 at pH 7.0 and resulted in only a slight growth delay in both strains. These results suggest that the two CAs induced by BLZ8 may mitigate the stress imposed by alkaline growth conditions.

Figure 6.

The CA inhibitor EZ abolishes BLZ8 overexpression effect on the alkaline stress tolerance. Representative photographs (A) and chlorophyll content (B) of CC-4533 and BLZ8 OX grown in either TAP medium (pH 7.0) or AMPSO-acetate phosphate medium (pH 9.0). The final concentration of EZ in the medium was 50 μM. Data are shown as mean ± sem; N = 3.

BLZ8 interacts with bZIP2 to regulate the expression of oxidative stress-responsive genes

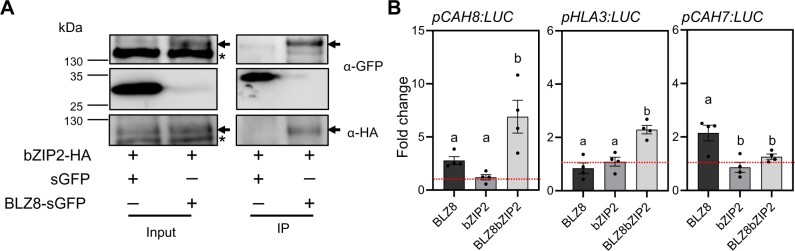

Since bZIP transcription factors generally function as dimers (Dröge-Laser et al., 2018), we next sought to identify the potential dimerization partner of BLZ8. Co-expression data obtained from ALCOdb (Aoki et al., 2015) revealed that bZIP2 showed the highest co-expression with BLZ8 (Supplemental Table S2). In agreement, bZIP2 transcript levels were highly induced by Met treatment (Figure 1A), making bZIP2 a likely candidate partner of BLZ8. To test this notion, we transiently transfected Arabidopsis protoplasts with constructs encoding BLZ8-sGFP and bZIP2-HA. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays using anti-GFP antibody revealed that BLZ8 interacts with bZIP2 in planta (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

bZIP2 binds to BLZ8 and enhances transcriptional activity of BLZ8 at the HLA3 and CAH8 promoters. A, Co-IP of BLZ8 with bZIP2 in planta. bZIP2-HA was transiently co-transfected with BLZ8-sGFP or sGFP (as negative control) in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Extracted proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody. Input and IP samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP and anti-HA antibodies. Arrows indicate BLZ8-sGFP or bZIP2-HA, and asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. B, Binding of BLZ8 and bZIP2 to the CAH8, HLA3, and CAH7 promoters, as seen with the luciferase reporter system in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Presented values are fold difference from the control (the value obtained from cells transfected with the reporter construct only). Data are shown as mean ± sem; statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s HSD test (P ≤ 0.05); N = 4.

To investigate the role of the BLZ8–bZIP2 heterodimer in regulating oxidative stress-responsive genes, we transfected Arabidopsis protoplasts with effector constructs overexpressing BLZ8 and bZIP2 and reporter constructs consisting of the firefly luciferase (LUC) reporter gene driven by the promoters of BLZ8 targets identified earlier. BLZ8 expression alone increased the luciferase activity associated with the ProCAH8:LUC and ProCAH7:LUC reporters. Co-transfection of bZIP2 together with BLZ8 further elevated LUC activity from ProCAH8:LUC but not ProCAH7:LUC. LUC activity derived from the ProHLA3:LUC reporter increased only when bZIP2 was co-transfected with BLZ8 (Figure 7B). These results suggest that BLZ8 directly activates the transcription of the three target genes tested here. Furthermore, for a subset of BLZ8 targets, including HLA3 and CAH8, bZIP2 is required to fully activate transcription.

Discussion

bZIP-type transcription factors have been extensively studied in stress responses of terrestrial plants, and many mediate stress-induced ROS responses (Nijhawan et al., 2008; Dröge-Laser et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2020). However, in the model microalga Chlamydomonas, only one bZIP transcription factor has been characterized in detail so far and was reported to participate in acclimation to 1O2 (Fischer et al., 2012). Here, we provide several lines of evidence that the bZIP transcription factor BLZ8 functions in the oxidative stress signaling induced by H2O2 in Chlamydomonas. First, BLZ8 expression was induced upon Met treatment, which specifically generates H2O2 in the chloroplast (Figure 1). Second, the BLZ8 OX strain grew better, while the growth of the blz8-1 mutant was impaired, in the presence of H2O2-inducing chemicals (Met) (Figure 2A). Third, RNA-seq of BLZ8 OX cells experiencing oxidative stress revealed that upregulated DEGs were enriched in ROS detoxification in the chloroplast (Figure 3). Fourth, BLZ8 induced the CCM, which provided an electron sink pathway to suppress ROS formation (Figures 4 and 5). Finally, BLZ8 directly regulated the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress responses, in part by physically interacting with bZIP2 to activate a subset of the target genes (Figure 7). No other microalgal transcription factor has been identified to date that mediates tolerance responses to H2O2.

BLZ8 function does not appear to be restricted to H2O2 tolerance but might contribute to general oxidative stress responses, because BLZ8 expression levels corresponded with tolerance to high pH and high light, as well as to Met and tBOOH (Figure 2). However, BLZ8 may be independent of 1O2-specific responses, as the BLZ8 OX strain and the blz8-1 mutant did not exhibit adverse growth effects compared to their parental strains when treated with neutral red or Rose Bengal, which generate 1O2 (Supplemental Figure S2). Responses to H2O2 and to 1O2 were previously suggested to be independent based on studies in photosynthetic organisms (Laloi et al., 2007; Blaby et al., 2015). Our data on BLZ8 also support the independence of responses to these two ROS species and indicate that BLZ8 is specifically involved in responses to H2O2.

As demonstrated by the RNA-seq analysis conducted in BLZ8 OX and its parental strain, BLZ8-regulated genes were mainly involved in chloroplast activities (Figure 3B). Highly expressed genes in BLZ8 OX upon Met treatment also included those likely critical to ROS detoxification, as well as the CCM. Among them, PTOX1, GLUTATHIONE PEROXIDASE5, ferredoxin-5, and Cre10.g439550 were previously reported to be induced by H2O2 treatment (Blaby et al., 2015). In addition, PRX1, another gene previously reported to be involved in antioxidation of ROS in the chloroplasts (Goyer et al., 2002), required BLZ8 to be induced under the oxidative stress conditions (Figure 3C and Supplemental Table S1), suggesting that BLZ8 contributes to the detoxification of ROS in the chloroplast. These data suggest that Chlamydomonas cells developed diverse mechanisms that protect chloroplasts from oxidative damage, with the transcription factor BLZ8 mediating multiple pathways.

We established that the CCM is induced by BLZ8 under oxidative stress conditions, thereby conferring higher stress tolerance. Our evidence is four-fold. First, the expression of CCM-related genes (HLA3, CAH7, and CAH8) was regulated by BLZ8 (Figures 3, 4, B, and 7B). Second, expression of BLZ8 was necessary for the accumulation of HLA3 and LCIA (Figure 4C). Third, BLZ8 expression levels correlated with Ci affinity and growth of cells at high pH (Figure 4D and Supplemental Figure S5B). Alkaline pH of the medium lowers the concentration of dissolved CO2 available for photosynthesis and disrupts the ion balance and enzymatic activities, thus triggering strong oxidative stress in microalgae (Vardi et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2007). Indeed, when the cultures were exposed to alkaline stress, we observed a severe reduction in Chlamydomonas growth (Supplemental Figure S5B) and increased lipid peroxidation (Figure 2D). Fourth, BLZ8-mediated CCM induction correlates with enhanced ETR (Figure 5D), which reduced the excitation pressure on the electron transport chain (Figure 5C). Furthermore, ROS measured under the same conditions revealed that BLZ8 expression reduced ROS levels (Figure 5E). These results suggested that BLZ8 expression provided an electron sink pathway that reduced ROS production.

Several reports support the notion that the CCM plays a role in oxidative stress tolerance. A reduction in the transcript levels of HLA3, a representative CCM gene that encodes an HCO3− transporter located at the plasma membrane, decreased Ci affinity and inhibited growth under alkaline stress (pH 9.0) (Duanmu et al., 2009; Yamano et al., 2015). The chlorosis phenotype of a mutant deficient in lipid metabolism resulting from high ROS production under high light exposure was rescued by treatment with bicarbonate (Du et al., 2018). In the CAC1 Chlorella mutant, a constitutively active CCM improved tolerance to high light stress (Hwangbo et al., 2018). In terrestrial plants, the enhanced abiotic stress tolerance of C4 plants was similarly speculated to be due to high radiation use efficiency mediated by the CCM to prevent generation of ROS (Singh and Thakur, 2018). However, the genetic basis of the direct role of CCM activation upon oxidative stress has not been demonstrated in microalgae or land plants. Our results establish that various oxidative stresses activate BLZ8, which in turn elevates CCM activity, thus contributing to oxidative stress tolerance in microalgae. To the best of our knowledge, BLZ8 has not previously been implicated in the CCM.

CAs mediate the interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−, an essential step in the CCM. Chlamydomonas CAH3 was induced by the transition from high to ambient levels of CO2 and was required for growth under CO2-limiting conditions (Moroney et al., 2011). Our results on CAH7 and CAH8 suggest that they differ from CAH3 in their induction kinetics. CAH7 and CAH8 transcript levels dramatically increased under alkaline stress in a BLZ8-dependent manner, but not after a decrease in CO2 levels (Figure 4, A and B). Expression of these two CAs and BLZ8 was not regulated by the master regulator CCM1, which induces the CCM genes necessary for acclimation to CO2 limitation (Fang et al., 2012). The alkaline stress-tolerant phenotype of BLZ8 OX was abolished by treatment with EZ, an inhibitor of CAs (Figure 6). These results indicate that the two CAs function in alleviating oxidative stress and may not be important for acclimation to changes in CO2 concentration. In terrestrial plants, CAs were also reported to have antioxidant activity and mitigate the damage caused by oxidative stress (Slaymaker et al., 2002). However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

The CCM in microalgae is activated mainly by the limitation of CO2, mediated by two transcription regulators, a zinc-containing nuclear protein, CCM1 (Fukuzawa et al., 2001) and a MYB-type transcription factor, low-CO2 stress response1 (Yoshioka et al., 2004). Recent “omics” studies have attempted to identify additional factors that regulate CCM induction upon CO2 limitation (Fang et al., 2012; Arias et al., 2020) and provided many candidate regulators of the process. However, fluctuation of CO2 levels does not seem to be the only cue for CCM induction, and retrograde signals originated from stresses might also induce CCM (Wang et al., 2016; Santhanagopalan et al., 2021). For example, the CCM is induced under high light stress conditions even in CO2-supplemented conditions, in which the cell culture is bubbled with air containing 1.2% CO2 (v/v) (Yamano et al., 2008). Our data indicate that oxidative stress could induce the CCM, too. Therefore, we speculate that the CCM is activated by multiple triggers and contributes to multiple pathways by which microalgae adapt to the ever-changing environmental conditions they encounter.

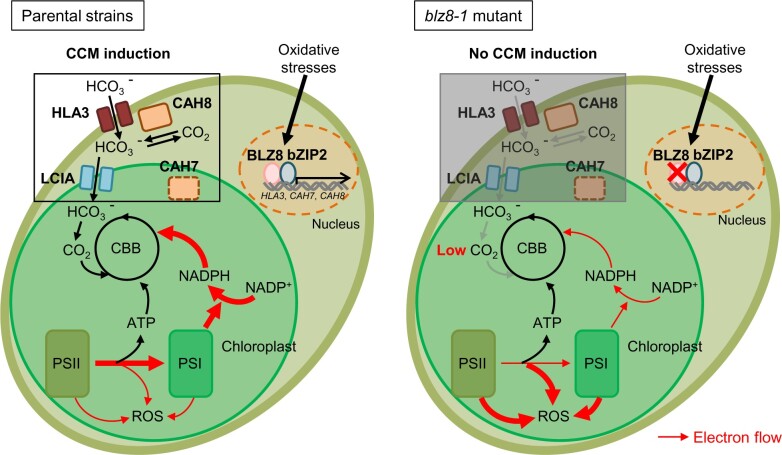

In the vast literature on stress tolerance in terrestrial plants, few reports suggest a role for the CCM. In microalgae, the importance of the CCM in oxidative stress tolerance was suggested based on physiological data (Hwangbo et al., 2018), but supporting genetic evidence was lacking. Here, we provided rigorous genetic, biochemical, and physiological evidence demonstrating the role of the CCM in oxidative stress responses in Chlamydomonas. We suspect that the CCM is more important in stress tolerance in microalgae than in terrestrial plants, since the aqueous environment differs from the land environment in terms of CO2 availability; in water, gas diffusion is 10,000 times slower than in air, which might impose a bottleneck in photosynthetic electron flow. Thus, it is likely that photosynthetic water dwellers evolved mechanisms that reinforce the CCM not just for photosynthetic efficiency, but also to minimize oxidative stress. In summary, our study revealed that Chlamydomonas exploits BLZ8 to increase the CO2 supply for photosynthesis by inducing the CCM, thereby providing an electron sink pathway that suppresses ROS production (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

A working model for BLZ8 function in Chlamydomonas under oxidative stress conditions. Oxidative stresses induce the expression of BLZ8 in Chlamydomonas. BLZ8, alone or in collaboration with bZIP2, induces the CCM (HLA3, LCIA, CAH7, and CAH8). CCM proteins increase the CO2 supply to the CBB cycle, the carbon assimilation step of photosynthesis, which consumes the high energy of the excited electrons. Thus, the CCM reduces excitation pressure on the photosynthetic electron transport chain and consequently suppresses ROS production in the chloroplast. In the blz8-1 mutant strain, the CCM is not induced under oxidative stress conditions, excitation pressure on the electron transport chain increases, and ROS are produced in the chloroplast. The localization of CAH7 protein was predicted using PredAlgo (Tardif et al., 2012).

There have been attempts to increase agricultural yield by introducing and/or enhancing the CCM in crop plants (Mackinder, 2018; Hennacy and Jonikas, 2020). Our data reveal that growth of Chlamydomonas cells under stress conditions is protected by reinforcing the CCM (Figure 4D; Supplemental Figure S5). This result suggests a potential for the CCM strategy in buffering the yield of terrestrial crop plants against the stresses caused by global weather changes, which are becoming increasingly severe and erratic. The genes identified here might be useful to enhance oxidative stress tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency, thus protecting future agricultural yield.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC-4533 (cw15 mt−) and the BLZ8 OX (LMJ.RY0402.052754) strain were obtained from the Chlamydomonas Library Project (CLiP, https://www.chlamylibrary.org) (Li et al., 2016). Since there was no knockout or knockdown mutant of BLZ8 in the CC-4533 background, we isolated the blz8-1 mutant from the random insertional mutant library derived from the C9 Chlamydomonas strain, following a previously described protocol (Yamano et al., 2015). CC-4533 is a cell wall-deficient strain whereas C9 has an intact cell wall. The insertion sites of the antibiotic resistance cassettes in the mutants were confirmed by PCR using KOD FX Neo polymerase (TOKFX-201, TOYOBO) as described previously (Li et al., 2016).

Cells were cultured at 23°C under continuous white light illumination supplied by tubular fluorescent lamps (color temperature of 4,000 K) at 80-μmol photons·m−2·s−1. For mixotrophic growth, cells were grown in Tris–acetate phosphate (TAP) medium, either as liquid cultures on an orbital shaker with 160 rpm shaking or on solid plates with the addition of 1% micro agar (M1002, Duchefa). Cells in the exponential growth phase (optical density at 730 nm (OD730) of ∼0.6) were treated with individual ROS-inducing chemicals to the final indicated concentrations. For high light illumination, 6 μL of culture was spotted onto TAP plates and exposed to high light of 750-μmol photons·m−2·s−1 supplied by an LED flat panel of white light (T5065O, KUMHO ELECTRIC). To induce alkaline stress, cells grown in TAP medium to an OD730 of ∼0.6 were collected by centrifugation (750g, 5 min, 25°C), washed, and resuspended in either N-(1,1-dimethyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-3-amino-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid (AMPSO)-acetate phosphate medium, in which 25 mM AMPSO-KOH (pH 9.0) was used to replace Tris–HCl in TAP medium, or 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-acetate phosphate medium, in which 25-mM HEPES-KOH (pH 8.5) was used to replace Tris–HCl in TAP medium. For photoautotrophic growth, cells grown overnight in TAP medium were diluted into MOPS·P medium containing 620-µM K2HPO4, 412-µM KH2PO4, and Hutner’s trace elements, buffered with 25-mM MOPS-KOH to pH 7.0, and aerated with 5% CO2 (HC). To induce low CO2-inducible genes and alkaline stress, cells grown in MOPS·P with HC (OD730 of ∼0.6) were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in the indicated medium aerated with 0.04% CO2 (ambient CO2). The pH of the medium was adjusted to 8.5 using 25 mM HEPES-KOH (HEPES·P) or to 9.0 using 25 mM AMPSO-KOH (AMPSO·P). Total chlorophyll content of cultures was determined using a microplate reader (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN) as described (Warren, 2008).

Lipid peroxidation measurements

MDA assays were performed as described (Hochmal et al., 2016), with minor modifications. Two 8-mL aliquots per culture with known cell numbers were mixed with 0.01% (w/v) butylated hydroxytoluene and then harvested by centrifugation at 750g for 5 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1.8-mL extraction buffer (3.75% trichloroacetic acid (w/w) and 0.05 N HCl) with or without 0.1% thiobarbituric acid. Mixtures were boiled in a water bath for 15 min, cooled, and centrifuged at 750g for 5 min at 25°C. Absorbance of the supernatants was read at 440, 532, and 600 nm. MDA equivalents were calculated using a molar extinction coefficient for MDA of 157,000 M−1 cm−1 (Hodges et al., 1999).

RNA-seq experiments

Two independent replicate cultures in the exponential growth phase (OD730 of ∼0.6) were collected immediately before the addition of 5 mM Met (0 h control) or treated with 5 mM Met and collected 1 and 2 h into the chemical treatment. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (74,904, Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples with an RNA integrity number >8 were used for library preparation. Each paired-end cDNA library was prepared according to the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Guide (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Paired-end reads were cleaned using prinseq-lite version 0.20.4 with the following parameters: min_len 50; min_qual_score 10; min_qual_mean 20; derep 14; trim_qual_left 20; trim_qual_right 20 (Schmieder and Edwards, 2011). The clean paired-end reads were aligned to the reference genome and annotation (C. reinhardtii version 5.5 from Phytozome version 12 database (Merchant et al., 2007)) using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009). RSEM version 1.3.0 software was used to obtain read counts and Trimmed Mean of M-values-normalized transcripts per million (TPM) values for each transcript (Li and Dewey, 2011). For differential expression analysis, EdgeR version 3.16.5 was used to calculate the negative binomial dispersion across conditions (Robinson et al., 2010). Genes were determined to be significantly differentially expressed if the expression levels showed a fold-change > 4 with a P<0.001. Functional annotation of DEGs was performed via sequence similarity searches using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool program against the A. thaliana protein database with an e-value threshold of 1 × 10−7. For GO enrichment analysis, homologous Arabidopsis genes for all DEGs were analyzed in DAVID (Dennis et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2009). To analyze representative enriched GO terms shown in Figure 3B, GO terms with P value < 0.05 were summarized and visualized using REVIGO (Supek et al., 2011) set to “Medium (0.7)” similarity cut-off with SimRel semantic similarity measures.

RNA extraction and quantification

Total RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus (9109, Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated RNA was quantified with a NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and 2.5 μg RNA was subjected to reverse transcription with the RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (K1621, Thermo Fisher). RT-qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (RR420A, Takara) and the primer sets listed in Supplemental Table S3. Transcript levels were normalized to CBLP as an internal control (Yamano et al., 2015). The R2 value of calibration curve and percentage of PCR efficiency using a CBLP gene primer set and cDNA from Chlamydomonas cells were 0.9997% and 119%, respectively.

Immunoblot analyses of HLA3 and LCIA

To examine the protein levels of HLA3 and LCIA, cells were grown under either high CO2 conditions (5%) or ambient CO2 conditions (0.04%) at pH 7.0 for the indicated periods. Immunoblot analyses were conducted following the described method (Yamano et al., 2015).

Ci-dependent photosynthetic O2 evolution

Ci-dependent photosynthetic O2 evolution was measured using a Clark-type O2 electrode (Hansatech Instruments), as described (Yamano et al., 2015). Cells grown in MOPS·P under ambient CO2 were collected and resuspended in Ci-depleted 20 mM AMPSO-NaOH buffer (pH 9.0). Cell suspension (1.5 mL) was transferred into the O2 electrode chamber illuminated by 320 μmol photons·m−2·s−1 for 15 min with bubbling of N2 gas to deplete Ci. The intensity of actinic light was increased to 750 μmol photons·m−2·s−1, and an increasing concentration of NaHCO3 was injected into the cells. K0.5 (Ci) indicates the Ci concentration required for the half-maximal rate of oxygen evolution.

Chlorophyll fluorescence analyses and ROS measurements

To analyze PSII photochemistry and ROS levels, cells grown in MOPS·P medium (pH 7.0) under high CO2 conditions (5%) were transferred to AMPSO·P medium (pH 9.0) under ambient CO2 conditions and incubated for the indicated periods. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were performed as described (Niyogi et al., 1997), with modifications. Cells containing 20-μg chlorophyll a were deposited on a 1.5-μm pore-size glass microfiber filter disc (934-AH, Whatman) by filtration. The filtered cells were dark-acclimated for at least 20 min before chlorophyll fluorescence was measured using IMAGING-PAM (IMAG-K5, Walz). For ROS measurements, 1 mL culture with a known cell number was harvested and washed with MOPS·P medium (pH 7.0). Cell pellets were resuspended in 300 μL MOPS·P medium that contained 10 μM chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; C6827, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). The cell mixtures were incubated in the dark for 20 min. The fluorescence intensity of 2',7'-dichlorofluorescein was measured using a microplate reader with excitation/emission at 485/530 nm (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN).

Protoplast transient expression assay and Co-IP

BLZ8 and bZIP2 cDNAs were cloned into pGWB5 and pGWB14 (Nakagawa et al., 2008), respectively. The promoter regions for CAH7, CAH8, and HLA3, ∼2,000-bp upstream of the translation start codon, were cloned into pGreenII 0800-LUC (Hellens et al., 2005) upstream of the firefly LUC gene, yielding the reporter constructs ProCAH7:LUC, ProCAH8:LUC, and ProHLA3:LUC. In these constructs, the Renilla luciferase gene (REN) under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter was used as an internal control. Primer sets used for cloning are listed in Supplemental Table S3. For luciferase reporter activity assays, 20-μg total plasmid DNA comprising combinations of effectors (35S:BLZ8 and 35S:bZIP2) and LUC reporters was introduced into 4 × 105 Arabidopsis protoplasts by polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transfection as described (Lee et al., 2008; Lee and Hwang, 2011), with minor modifications. Shoots of 2- to 3-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown on B5 medium agar plates were harvested and incubated in 25-mL enzyme solution (0.25% w/v Macerozyme R-10 (Yakult Honsha Co., Tokyo, Japan), 1.0% w/v Cellulase R-10 (Yakult Honsha Co.), 400-mM mannitol, 8 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Mes-KOH, pH 5.6) at 22°C for 15 h with agitation (50–75 rpm). Subsequently, the protoplast suspension was filtered through 100-μm mesh, loaded onto 25 mL 21% (w/v) sucrose solution, and centrifuged at 98g for 10 min at 25°C. The intact protoplasts in the top layer and at the interface were collected, washed with 30-mL W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, and 1.5 mM Mes-KOH, pH 5.6), and incubated on ice for 30 min. The protoplasts were pelleted and resuspended in MaMg solution (400-mM mannitol, 15-mM MgCl2, and 5-mM Mes-KOH, pH 5.6) at a density of 4 × 106 cells mL‒−1. For transfection, 100-μL protoplast suspension was mixed with 20 μL plasmid DNA (1 μg μL−1), and then 120-μL PEG solution (40% w/v PEG4000 (P0633, SAMCHUN), 200-mM mannitol, and 100-mM Ca(NO3)2) was added. The mixture was shaken gently and incubated for 10 min at 25°C under dim light. The protoplasts diluted with 500-μL W5 solution were collected, resuspended in 500 μL W5 solution, and incubated at 23°C under dim light. After 24-h incubation, LUC and REN activities were assayed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (E1910, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and chemiluminescence was measured using a microplate reader (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN).

For Co-IP assays, transfected protoplasts were resuspended in 100 μL IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100-mM NaCl, 1-mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor tablets (88266, Thermo Fisher)) and lysed by vortexing vigorously for 10 s. The lysates were centrifuged at 13,800g for 5 min at 4°C, and the total proteins in the supernatant were incubated with 1-μg anti-GFP antibody (A-11122, Invitrogen) at 4°C to immunoprecipitate sGFP-tagged proteins. After 12-h incubation, the mixture was incubated with 60-μL protein A Agarose (16–157, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and washed with IP buffer for 2 h at 4°C. Then the protein-coated agarose beads were washed with IP buffer three times. Subsequently, proteins on the beads were eluted by boiling for 3 min in Laemmli buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gels, and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-HA (1:500; sc-7392, Santa Cruz) or anti-GFP (1:2,000; A-11122, Invitrogen) primary antibodies. Anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:50,000; no. 32,260, Thermo) and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:5,000; A90-116P, Bethyl) conjugated antibodies were used to detect anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies, respectively. Chemiluminescence was detected by the LAS-4000 imaging system (Fuji) with the SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (34095, Thermo).

Tetrad analysis

Tetrad analysis was performed as described (Yamaoka et al., 2018). BLZ8 OX in the CC-4533 background (cw15 mt−) and CC-5155 (cw15 mt+, isogenic strain of CC-4533) grown on TAP agar medium were transferred to TAP agar medium without nitrogen (TAP −N) to induce gametogenesis. After 1 day incubation, cells were resuspended in TAP −N liquid medium and illuminated at 80 μmol photons·m−2·s−1 for 2 h with agitation. Equal amounts of mt+ and mt− gametes were mixed and incubated in the light without agitation for 2 h. The mixture was spotted onto TAP plates with 3% agar and incubated at 23°C in the dark for 6 days. For germination, zygotes were transferred to TAP agar plates and incubated in the light for 1 day. Progenies from germinated zygotes were dissected under an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE2000-U, Nikon).

Complementation of the blz8-1 mutant

A DNA fragment covering 1,932-bp upstream of the BLZ8 start codon was used as the BLZ8 promoter and was cloned into pMO449 (Onishi and Pringle, 2016) at the NheI/HpaI sites, yielding pMO449-Pro. A DNA fragment containing the BLZ8 3′-UTR was cloned into pMO449-Pro at the BamHI/NcoI sites, yielding pMO449-Pro3′-UTR. The BLZ8 genomic DNA sequence without the stop codon was cloned into pChlamy_4 vector (Life Technologies) and subcloned into pMO449-Pro3′UTR using SLiCE (Zhang et al., 2012), yielding pMO449-BLZ8. Finally, the APHVIII cassette (ProHSP70A/RBCS2-APHVIII-3′-UTRRBCS2) from pLM005 (Yang et al., 2015) was cloned into pMO449-BLZ8 at the XbaI site to obtain pTP-BLZ8, which was used to transform blz8-1 by electroporation using a NEPA-21 electroporator, as described previously (Yamano et al., 2013). Transformants were selected on TAP agar plates containing 7.5 μg mL−1 paromomycin. Primer sets used for cloning are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

Statistics

The pairwise Student’s t test (two-tailed) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9 software. All data were expressed either as mean value or fold-change of mean values as indicated. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (sem) based on biological replicates (N) from independent cell cultures. Statistical data are provided in Supplemental Data Set S3.

Accession numbers

Genes analyzed in this article have the following accession numbers in Phytozome v12 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html): BLZ8 (Cre12.g501600), bZIP2 (Cre17.g746547), CAH7 (Cre13.g607350), CAH8 (Cre09.g405750), HLA3 (Cre02.g097800), LCIA (Cre06.g309000), MSRA2 (Cre06.g257650), PTOX1 (Cre07.g350750), and PRX1 (Cre06.g257601). The RNA-seq data generated in this study were deposited to the SRA database at the National Center for Biotechnological Information under the accession number PRJNA775620.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Isolation of the blz8 mutant and BLZ8 overexpression strain.

Supplemental Figure S2. blz8-1 and BLZ8 OX do not differ from their respective parental lines in growth on medium containing singlet oxygen-inducing chemicals.

Supplemental Figure S3. Sample correlation and PCA indicating the high reproducibility of the two replicates of our RNA-seq analysis.

Supplemental Figure S4. GO analysis of downregulated DEGs in BLZ8 OX.

Supplemental Figure S5. BLZ8 OX and blz8-1 differ from their respective parental strains in their tolerance to alkaline stress under photoautotrophic growth conditions.

Supplemental Table S1. List of candidate target genes of BLZ8 selected from the genes that belong to the ‘response to abiotic stimulus’ GO category shown in Figure 3B.

Supplemental Table S2. Genes co-expressed with BLZ8, analyzed from ALCOdb data.

Supplemental Table S3. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set S1. RNA-seq results of the CC-4533 and BLZ8 OX strains exposed to 5-mM Met.

Supplemental Data Set S2. GO analysis of upregulated and downregulated DEGs in BLZ8 OX compared to CC-4533.

Supplemental Data Set S3. Data for all statistical analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Chlamydomonas Mutant Library Group at the Carnegie Institution for Science and the Chlamydomonas Resource Center at the University of Minnesota for providing the indexed Chlamydomonas insertional mutants. We thank Donghui Hu for technical assistance in generating the C. reinhardtii C9 insertion mutant library and Prof. Ildoo Hwang for helping with chlorophyll fluorescence measurements.

Funding

B.Y.C. was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (KRF) grant (NRF-2017H1A2A1046102) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT). Y.L. was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (2021R1A2B5B03001711) and the Advanced Biomass R&D Center (ABC) of Global Frontier Project (ABC-2015M3A6A2065746) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT). D.S. was supported by a Korea Forestry Promotion Institute (KOFPI) grant (2021368A00-2123-BD01) funded by the Korea Forest Service (KFS). T.Y. and H.F. were supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants (JP20H03073 and JP16H04805, respectively).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Bae Young Choi, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

Hanul Kim, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

Donghwan Shim, Department of Biological Sciences, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134 Korea.

Sunghoon Jang, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

Yasuyo Yamaoka, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

Seungjun Shin, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

Takashi Yamano, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan.

Masataka Kajikawa, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan.

EonSeon Jin, Department of Life Science, Hanyang University, Seoul 133-791, South Korea.

Hideya Fukuzawa, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan.

Youngsook Lee, Department of Life Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Pohang 37673, Korea.

B.Y.C., H.K., S.J., Y.Y., S.S., H.F., and Y.L. designed the experiments. B.Y.C., H.K., and T.Y. performed the experiments. D.S. and B.Y.C. analyzed the RNA-seq data. M.K. produced C. reinhardtii mutants. B.Y.C., H.K., T.Y., E.J., H.F., and Y.L. analyzed the data. B.Y.C., T.Y., H.F., and Y.L. wrote the manuscript.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plcell) are: Hideya Fukuzawa (fukuzawa@lif.kyoto-u.ac.jp) and Youngsook Lee (ylee@postech.ac.kr).

References

- Aoki Y, Okamura Y, Ohta H, Kinoshita K, Obayashi T (2015) ALCOdb: gene coexpression database for microalgae. Plant Cell Physiol 57: e3–e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel K, Hirt H (2004) REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Ann Rev Plant Biol 55: 373–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias C, Obudulu O, Zhao X, Ansolia P, Zhang X, Paul S, Bygdell J, Pirmoradian M, Zubarev RA, Samuelsson G, et al. (2020) Nuclear proteome analysis of Chlamydomonas with response to CO2 limitation. Algal Res 46: 101765 [Google Scholar]

- Asada K (1999) THE WATER-WATER CYCLE IN CHLOROPLASTS: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 601–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaby IK, Blaby-Haas CE, Pérez-Pérez ME, Schmollinger S, Fitz-Gibbon S, Lemaire SD, Merchant SS (2015) Genome-wide analysis on Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals the impact of hydrogen peroxide on protein stress responses and overlap with other stress transcriptomes. Plant J 84: 974–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari OD, Meyer MT, Tolleter D, Wittkopp TM, Cunniffe NJ, Lawson T, Grossman AR, Griffiths H (2017) Pyrenoid loss in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii causes limitations in CO2 supply, but not thylakoid operating efficiency. J Exp Bot 68: 3903–3913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KX, Phua SY, Crisp P, McQuinn R, Pogson BJ (2016) Learning the languages of the chloroplast: retrograde signaling and beyond. Ann Rev Plant Biol 67: 25–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaux F, Burlacot A, Mekhalfi M, Auroy P, Blangy S, Richaud P, Peltier G (2017) Flavodiiron proteins promote fast and transient O2 photoreduction in Chlamydomonas. Plant Physiol 174: 1825–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournac GP (2002) Chlororespiration. Ann Rev Plant Biol 53: 523–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA (2003) DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol 4: R60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröge-Laser W, Snoek BL, Snel B, Weiste C (2018) The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor family—an update. Curr Opin Plant Biol 45: 36–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du ZY, Lucker BF, Zienkiewicz K, Miller TE, Zienkiewicz A, Sears BB, Kramer DM, Benning C (2018) Galactoglycerolipid lipase PGD1 is involved in thylakoid membrane remodeling in response to adverse environmental conditions in chlamydomonas. Plant Cell 30: 447–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu D, Miller AR, Horken KM, Weeks DP, Spalding MH (2009) Knockdown of limiting-CO2–induced gene HLA3 decreases transport and photosynthetic Ci affinity in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5990–5995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson E, Wakao S, Niyogi KK (2015) Light stress and photoprotection in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 82: 449–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang W, Si Y, Douglass S, Casero D, Merchant SS, Pellegrini M, Ladunga I, Liu P, Spalding MH (2012) Transcriptome-wide changes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii gene expression regulated by carbon dioxide and the CO2-Concentrating mechanism regulator CIA5/CCM1. Plant Cell 24: 1876–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BB, Ledford HK, Wakao S, Huang SG, Casero D, Pellegrini M, Merchant SS, Koller A, Eggen RIL, Niyogi KK (2012) SINGLET OXYGEN RESISTANT links reactive electrophile signaling to singlet oxygen acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E1302–E1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa H, Ogawa T, Kaplan A (2012) The uptake of CO2 by cyanobacteria and microalgae. In Eaton-Rye JJ, Tripathy BC, Sharkey TD, eds, Photosynthesis: Plastid Biology, Energy Conversion and Carbon Assimilation, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp 625–650 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa H, Miura K, Ishizaki K, Kucho KI, Saito T, Kohinata T, Ohyama K (2001) Ccm1, a regulatory gene controlling the induction of a carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by sensing CO2 availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5347–5352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer A, Haslekås C, Miginiac-Maslow M, Klein U, Le Marechal P, Jacquot JP, Decottignies P (2002) Isolation and characterization of a thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eur J Biochem 269: 272–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Allan AC, Friel EN, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Templeton MD, Karunairetnam S, Gleave AP, Laing WA (2005) Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennacy JH, Jonikas MC (2020) Prospects for engineering biophysical CO2 concentrating mechanisms into land plants to enhance yields. Annu Rev Plant Biol 71: 461–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochmal AK, Zinzius K, Charoenwattanasatien R, Gäbelein P, Mutoh R, Tanaka H, Schulze S, Liu G, Scholz M, Nordhues A, et al. (2016) Calredoxin represents a novel type of calcium-dependent sensor-responder connected to redox regulation in the chloroplast. Nat Commun 7: 11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges DM, DeLong JM, Forney CF, Prange RK (1999) Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 207: 604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protocol 4: 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo K, Lim JM, Jeong SW, Vikramathithan J, Park YI, Jeong WJ (2018) Elevated inorganic carbon concentrating mechanism confers tolerance to high light in an arctic Chlorella sp. ArM0029B. Front Plant Sci 9: 590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Sun J, Wunder T, Tang D, Cousins AB, Sze SK, Mueller-Cajar O, Gao YG (2016) Structural insights into the LCIB protein family reveals a new group of β-carbonic anhydrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 14716–14721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaki A, Takeba G (1996) Photorespiration protects C3 plants from photooxidation. Nature 384: 557–560 [Google Scholar]

- Laloi C, Stachowiak M, Pers-Kamczyc E, Warzych E, Murgia I, Apel K (2007) Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 672–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DW, Hwang I (2011) Transient expression and analysis of chloroplast proteins in Arabidopsis Protoplasts. In Jarvis RP, ed, Chloroplast Research in Arabidopsis: Methods and Protocols, Vol. I, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Choi Y, Burla B, Kim YY, Jeon B, Maeshima M, Yoo JY, Martinoia E, Lee Y (2008) The ABC transporter AtABCB14 is a malate importer and modulates stomatal response to CO2. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1217–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN (2011) RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang R, Patena W, Gang SS, Blum SR, Ivanova N, Yue R, Robertson JM, Lefebvre PA, Fitz-Gibbon ST, et al. (2016) An indexed, mapped mutant library enables reverse genetics studies of biological processes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 28: 367–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Au DWT, Anderson DM, Lam PKS, Wu RSS (2007) Effects of nutrients, salinity, pH and light: dark cycle on the production of reactive oxygen species in the alga Chattonella marina. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 346: 76–86 [Google Scholar]

- Mackinder LCM (2018) The Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism and its potential for engineering photosynthesis in plants. New Phytologist 217: 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, Harris EH, Karpowicz SJ, Witman GB, Terry A, Salamov A, Fritz-Laylin LK, Maréchal-Drouard L (2007) The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318: 245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Yamano T, Yoshioka S, Kohinata T, Inoue Y, Taniguchi F, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Yamato KT, et al. (2004) Expression profiling-based identification of CO2-responsive genes regulated by CCM1 controlling a carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Plant Physiol 135: 1595–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Husic HD, Tolbert NE (1985) Effect of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on inorganic carbon accumulation by Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 79: 177–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Ma Y, Frey WD, Fusilier KA, Pham TT, Simms TA, DiMario RJ, Yang J, Mukherjee B (2011) The carbonic anhydrase isoforms of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: intracellular location, expression, and physiological roles. Photosynth Res 109: 133–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P, Li XP, Niyogi KK (2001) Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol 125: 1558–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Nakamura S, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, Suzuki T, Nakamura K, Kimura T, Ishiguro S (2008) Development of R4 gateway binary vectors (R4pGWB) enabling high-throughput promoter swapping for plant research. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72: 624–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan A, Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP (2008) Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol 146: 333–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi KK, Bjorkman O, Grossman AR (1997) Chlamydomonas xanthophyll cycle mutants identified by video imaging of chlorophyll fluorescence quenching. Plant Cell 9: 1369–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi M, Pringle JR (2016) Robust transgene expression from bicistronic mRNA in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. G3 6: 4115–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlaza K, Toutkoushian H, Boone M, Lam M, Iwai M, Jonikas MC, Walter P, Ramundo S (2019) The Mars1 kinase confers photoprotection through signaling in the chloroplast unfolded protein response. eLife 8: e49577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanagopalan I, Wong R, Mathur T, Griffiths H (2021) Orchestral manoeuvres in the light: crosstalk needed for regulation of the Chlamydomonas carbon concentration mechanism. J Exp Bot 72: 4604–4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saroussi S, Karns DAJ, Thomas DC, Bloszies C, Fiehn O, Posewitz MC, Grossman AR (2019) Alternative outlets for sustaining photosynthetic electron transport during dark-to-light transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 11518–11527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt GW, Matlin KS, Chua NH (1977) A rapid procedure for selective enrichment of photosynthetic electron transport mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74: 610–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder R, Edwards R (2011) Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27: 863–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao N, Duan GY, Bock R (2013) A mediator of singlet oxygen responses in chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis identified by a luciferase-based genetic screen in algal cells. Plant Cell 25: 4209–4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa G, Matsuda Y, Nakajima K, Tamoi M, Shigeoka S, Miyake C (2017) Diverse strategies of O2 usage for preventing photo-oxidative damage under CO2 limitation during algal photosynthesis. Sci Rep 7: 41022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Thakur JK (2018) Photosynthesis and abiotic stress in plants. In Vats S, ed, Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants, Springer Singapore, Singapore, Asia, pp 27–46 [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker DH, Navarre DA, Clark D, del Pozo O, Martin GB, Klessig DF (2002) The tobacco salicylic acid-binding protein 3 (SABP3) is the chloroplast carbonic anhydrase, which exhibits antioxidant activity and plays a role in the hypersensitive defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11640–11645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T (2011) REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 6: e21800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif M, Atteia A, Specht M, Cogne G, Rolland N, Brugière S, Hippler M, Ferro M, Bruley C, Peltier G, et al. (2012) PredAlgo: a new subcellular localization prediction tool dedicated to green algae. Mol Biol Evol 29: 3625–3639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi A, Berman-Frank I, Rozenberg T, Hadas O, Kaplan A, Levine A (1999) Programmed cell death of the dinoflagellate Peridinium gatunense is mediated by CO2 limitation and oxidative stress. Curr Biol 9: 1061–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakao S, Chin BL, Ledford HK, Dent RM, Casero D, Pellegrini M, Merchant SS, Niyogi KK (2014) Phosphoprotein SAK1 is a regulator of acclimation to singlet oxygen in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. eLife 3: e02286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yamano T, Takane S, Niikawa Y, Toyokawa C, Ozawa SI, Tokutsu R, Takahashi Y, Minagawa J, Kanesaki Y, et al. (2016) Chloroplast-mediated regulation of CO2-concentrating mechanism by Ca2+-binding protein CAS in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 12586–12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR (2008) Rapid measurement of chlorophylls with a microplate reader. J Plant Nutr 31: 1321–1332 [Google Scholar]

- Waszczak C, Carmody M, Kangasjärvi J (2018) Reactive oxygen species in plant signaling. Ann Rev Plant Biol 69: 209–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Miura K, Fukuzawa H (2008) Expression analysis of genes associated with the induction of the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 147: 340–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Iguchi H, Fukuzawa H (2013) Rapid transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii without cell-wall removal. J Biosci Bioeng 115: 691–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Sato E, Iguchi H, Fukuda Y, Fukuzawa H (2015) Characterization of cooperative bicarbonate uptake into chloroplast stroma in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 7315–7320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Tsujikawa T, Hatano K, Ozawa SI, Takahashi Y, Fukuzawa H (2010) Light and low-CO2-dependent LCIB–LCIC complex localization in the chloroplast supports the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol 51:1453–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, Choi BY, Kim H, Shin S, Kim Y, Jang S, Song WY, Cho CH, Yoon HS, Kohno K, et al. (2018) Identification and functional study of the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 94: 91–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, Shin S, Choi BY, Kim H, Jang S, Kajikawa M, Yamano T, Kong F, Légeret B, Fukuzawa H, et al. (2019) The bZIP1 transcription factor regulates lipid remodeling and contributes to ER stress management in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 31: 1127–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Wittkopp TM, Li X, Warakanont J, Dubini A, Catalanotti C, Kim RG, Nowack ECM, Mackinder LCM, Aksoy M, et al. (2015) Critical role of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ferredoxin-5 in maintaining membrane structure and dark metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 14978–14983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ynalvez RA, Xiao Y, Ward AS, Cunnusamy K, Moroney JV (2008) Identification and characterization of two closely related β-carbonic anhydrases from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Physiol Plant 133: 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y, Seo DH, Shin H, Kim HJ, Kim CM, Jang G (2020) The role of stress-responsive transcription factors in modulating abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Agronomy 10: 788 [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka S, Taniguchi F, Miura K, Inoue T, Yamano T, Fukuzawa H (2004) The novel Myb transcription factor LCR1 regulates the CO2-responsive gene Cah1, encoding a periplasmic carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [W]. Plant Cell 16: 1466–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Chan Z (2015) ROS regulation during abiotic stress responses in crop plants. Front Plant Sci 6: 1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Werling U, Edelmann W (2012) SLiCE: a novel bacterial cell extract-based DNA cloning method. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e55–e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK (2016) Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167: 313–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.