Key Points

Question

What is the effect of an inpatient symptom monitoring intervention on symptom burden and health care use among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 321 hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, an inpatient symptom monitoring intervention did not have a significant effect on patients’ self-reported physical and psychological symptoms or their hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rates.

Meaning

Among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, this type of inpatient symptom monitoring intervention did not have a significant effect on symptom burden or health care use.

Abstract

Importance

Symptom monitoring interventions are increasingly becoming the standard of care in oncology, but studies assessing these interventions in the hospital setting are lacking.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of a symptom monitoring intervention on symptom burden and health care use among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nonblinded randomized clinical trial conducted from February 12, 2018, to October 30, 2019, assessed 321 hospitalized adult patients with advanced cancer and admitted to the inpatient oncology services of an academic hospital. Data obtained through November 13, 2020, were included in analyses, and all analyses assessed the intent-to-treat population.

Interventions

Patients in both the intervention and usual care groups reported their symptoms using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) and the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) daily via tablet computers. Patients assigned to the intervention had their symptom reports displayed during daily oncology rounds, with alerts for moderate, severe, or worsening symptoms. Patients assigned to usual care did not have their symptom reports displayed to their clinical teams.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of days with improved symptoms, and the secondary outcomes were hospital length of stay and readmission rates. Linear regression was used to evaluate differences in hospital length of stay. Competing-risk regression (with death treated as a competing event) was used to compare differences in time to first unplanned readmission within 30 days.

Results

From February 12, 2018, to October 30, 2019, 390 patients (76.2% enrollment rate) were randomized. Study analyses to assess change in symptom burden included 321 of 390 patients (82.3%) who had 2 or more days of symptom reports completed (usual care, 161 of 193; intervention, 160 of 197). Participants had a mean (SD) age of 63.6 (12.8) years and were mostly male (180; 56.1%), self-reported as White (291; 90.7%), and married (230; 71.7%). The most common cancer type was gastrointestinal (118 patients; 36.8%), followed by lung (60 patients; 18.7%), genitourinary (39 patients; 12.1%), and breast (29 patients; 9.0%). No significant differences were detected between the intervention and usual care for the proportion of days with improved ESAS-physical (unstandardized coefficient [B] = −0.02; 95% CI, –0.10 to 0.05; P = .56), ESAS-total (B = −0.05; 95% CI, –0.12 to 0.02; P = .17), PHQ-4–depression (B = −0.02; 95% CI, –0.08 to 0.04; P = .55), and PHQ-4–anxiety (B = −0.04; 95% CI, –0.10 to 0.03; P = .29) symptoms. Intervention patients also did not differ significantly from patients receiving usual care for the secondary end points of hospital length of stay (7.59 vs 7.47 days; B = 0.13; 95% CI, –1.04 to 1.29; P = .83) and 30-day readmission rates (26.5% vs 33.8%; hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48-1.09; P = .12).

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial found that for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, the assessed symptom monitoring intervention did not have a significant effect on patients’ symptom burden or health care use. These findings do not support the routine integration of this type of symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03396510

This nonblinded randomized clinical trial compares the effects of a symptom monitoring intervention vs usual care on symptom burden and health care use among hospitalized adult patients with advanced cancer.

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer experience a substantial symptom burden, which is often underrecognized by their clinicians.1,2,3,4,5 Symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and nausea lead to poor quality of life and functional impairment, and patients with these symptoms report high rates of depression and anxiety.6,7,8,9 In addition, patients’ symptoms contribute to their use of health care services, such as prolonged hospitalizations and readmissions.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 Despite the high symptom burden of patients with advanced cancer, data suggest that clinicians frequently fail to accurately identify their patients’ symptoms, often underestimating the severity, and patients may underreport their symptoms to their oncology team.4,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 Thus, inadequately treated symptoms represent a highly prevalent and problematic issue for patients with advanced cancer, underscoring the need for interventions to help monitor and address these patients’ symptom burden when seeking to improve care delivery and outcomes in oncology.

Symptom monitoring interventions using patient-reported outcomes have shown the ability to enhance the care of patients with cancer and have increasingly become the standard of care in oncology.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 Specifically, data support the use of patient-reported symptom monitoring interventions for patients with cancer to improve symptom management, enhance quality of life, prevent hospitalizations, and potentially increase survival.26,27,28,29,33,34,35 Based on the compelling results with symptom monitoring interventions in the outpatient setting to date, a growing interest exists to implement remote monitoring of patient-reported outcomes as part of routine oncology practice.30,31,32 However, most of the existing data on patient-reported symptom monitoring interventions focus on patients in the outpatient setting, despite the higher symptom burden and worse clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with cancer.10,12,13,14,15,35,36,37 We previously conducted a pilot randomized clinical trial of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, which we called Improving Management of Patient-Reported Outcomes Via Electronic Data (IMPROVED).38 In that prior work, we showed the feasibility of delivering IMPROVED and highlighted the need for a larger randomized clinical trial to further investigate the efficacy of this intervention.

In the present study, we sought to assess the effects of IMPROVED on symptom burden and health care use among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. We hypothesized that patients assigned to IMPROVED would report significantly improved symptom burden over the course of hospitalization (primary outcome), experience shorter hospital length of stay (LOS), and have lower readmission rates compared with those assigned to usual care. We chose these outcomes because they are meaningful to patients, clinicians, and health systems as key measures of patients’ care experience and outcomes and because they are frequent outcome measures for symptom monitoring interventions.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 By showing the effects of a symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, findings from this work have the potential to inform future efforts to enhance outcomes for this highly symptomatic population.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

From February 12, 2018, to October 30, 2019, we enrolled patients at Massachusetts General Hospital in a nonblinded randomized clinical trial of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention (IMPROVED) vs usual care (Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology A20 Pilot739). Trained study staff identified and recruited patients with an unplanned hospital admission during the study period by screening the daily inpatient oncology service census. After providing informed consent, participants completed baseline study measures and were then randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive IMPROVED or usual care (randomization list generated by statistician and performed within randomly permuted blocks and stratified by cancer type). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Within 36 hours of hospital admission, eligible patients provided written informed consent. No one received compensation or was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

Participants

Eligible patients included those 18 years or older who were admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital oncology service with a known diagnosis of advanced cancer (defined as receiving treatment with palliative intent as per chemotherapy order entry designation or oncology clinic notes, or not receiving chemotherapy but followed up for incurable disease as per oncology clinic notes). Study participants had to be able to read and respond to questions in English. We excluded patients with planned or elective hospitalizations, defined as hospital admissions for scheduled procedures or for chemotherapy administration or desensitization.

IMPROVED

Patients assigned to receive the IMPROVED intervention reported their symptoms daily using tablet computers. Each day during morning inpatient rounds, trained study staff presented the symptom reports to the clinical team (nurses, advanced practice providers, and physicians) via both a printout version of the symptom reports and a computer-based projection screen as they were being discussed. Notably, morning rounds each day consisted of the clinical team meeting in a central room on the inpatient oncology ward to discuss each patient. The detailed symptom reports provided patients’ numeric symptom scores as well as alerts for any specific symptom worsening by 2 or more points from the previous assessment or for any symptom reaching an absolute score of 4 or higher. Those detailed symptom reports also contained graphs depicting patients’ symptom trajectory for the hospitalization. We offered no guidance about managing patients’ symptoms and left all symptom management decisions up to the treating oncology team per their clinical judgment.

Usual Care

Patients receiving usual care reported their symptoms each day, yet these participants’ clinical teams did not receive their symptom reports. Study staff instructed patients in both study groups to report their symptoms as they normally would to their clinical team.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Participants completed baseline study measures prior to randomization. To describe participant demographic characteristics, we asked patients to self-report their race, relationship status, employment, educational level, and annual income. We obtained information about participants’ age, sex, cancer, and comorbidities from the electronic health record.

Patient-Reported Symptom Burden

We obtained patients’ self-reported symptom burden at baseline (at the time of study consent) and daily throughout their hospital admission, including weekends. We used the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), a validated tool for patients with cancer, to measure symptom burden.40,41,42,43 The ESAS assesses pain, fatigue, tiredness, nausea, drowsiness, appetite, dyspnea, and well-being. We also included constipation and diarrhea because they are highly prevalent and modifiable symptoms among patients with cancer.42,44,45,46,47 Patients rated their symptoms on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 reflecting absence of the symptom; 10, the worst possible severity). We categorized the severity of each symptom score as none (0), mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-10), consistent with prior work.16 In addition, we computed composite ESAS-physical and ESAS-total symptom scores, which included summated values of patients’ physical and total symptoms, as previously used in the oncology setting.38,41,48 To evaluate patients’ self-reported psychological symptoms, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), a 4-item tool with two 2-item subscales assessing depression and anxiety (scores ≥3 for each subscale denoting clinically significant depression or anxiety symptoms).49,50 Both subscales (range, 0-6) and the composite PHQ-4 (range, 0-12) can be evaluated continuously, with higher scores indicating worse psychological distress.49

Health Care Use

We obtained information about hospital LOS and unplanned hospital readmissions from the electronic health record because most patients receiving their cancer care at Massachusetts General Hospital are admitted within this health system.38 For hospital LOS, we calculated the number of days from admission to discharge. To determine the risk of hospital readmissions, we identified unplanned readmissions within 30 and 90 days of hospital discharge and calculated time to first unplanned readmission as the number of days from hospital discharge to the first unplanned admission within 30 and 90 days, consistent with prior work.16,38,51

Statistical Analysis

We included data obtained through November 13, 2020, in the analyses. The primary outcome was a comparison of change in ESAS-physical symptom burden, as measured by the proportion of days with improved symptoms for those who completed 2 or more days of symptom reports, between study groups.38 To calculate the proportion of days that patients’ symptoms improved, we summed the total days that patients had an improvement in their symptom score and divided this value by the total number of days with symptom assessments completed after baseline. Based on data from the pilot study, we estimated that 320 patients would provide greater than 80% power to detect a mean (SD) difference of 0.09 (0.28) in the mean proportion of days with improved ESAS-physical symptoms between study groups using a t test with a 2-sided significance level of .05.38 To determine differences in the mean proportion of days that patients’ symptoms improved, we used linear regression, adjusted for baseline symptom score. To further assess changes in patients’ symptom burden throughout their hospitalization, we used linear regression to evaluate the mean daily change in symptom scores during the hospitalization, adjusted for baseline symptom score. We also explored differences in the proportion of days in which patients reported any symptom worsening by 2 or more points from the previous assessment or any symptom scored 4 or higher because these are clinically important cutoffs to patients and would have resulted in an alert to the team for patients receiving the intervention.43,48 To evaluate differences in hospital LOS, we used linear regression. To compare differences in time to first unplanned readmission within 30 and 90 days, we used competing-risk regression (with death treated as a competing event). All data analyses included the intent-to-treat population and were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participant Characteristics

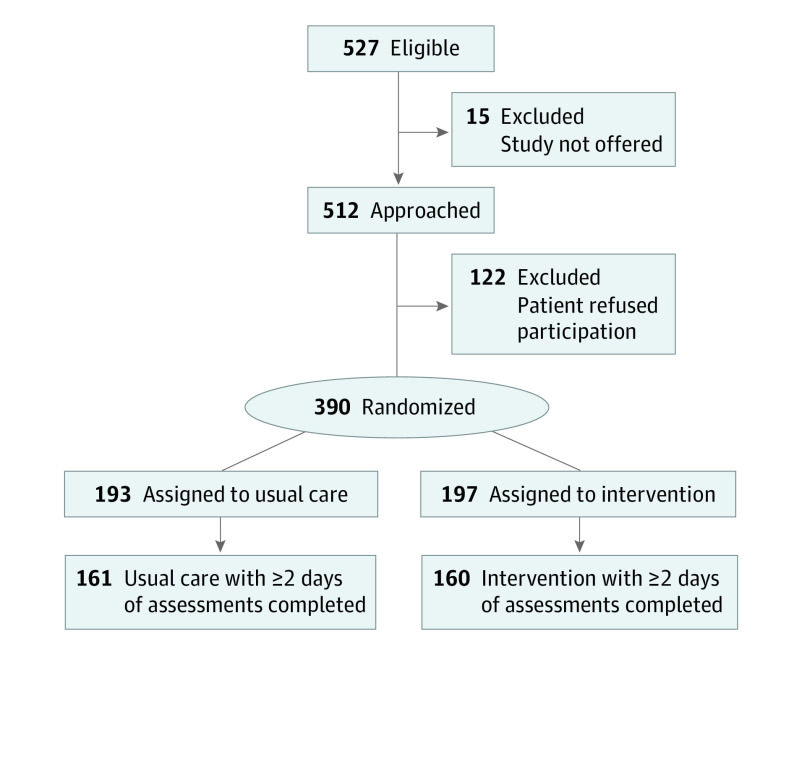

We enrolled 390 patients (76.2% of patients approached; Figure). Our study analyses included 321 of 390 patients (82.3%) who had 2 or more days of symptom reports completed (usual care, 161 of 193; IMPROVED, 160 of 197), as we sought to assess change in symptom burden. We found no significant differences in baseline characteristics between patients who did or who did not complete 2 or more days of symptom reports. Patients completed a total of 1270 daily symptom reports during a total of 1723 hospitalized days in which symptom collection was possible. The average rate of daily symptom report completion per patient was 81.0%, with a mean (SD) of 3.74 (2.20) symptom reports completed per patient. Participants had a mean (SD) age of 63.6 (12.8) years and were mostly male (180; 56.1%), self-reported as White (291; 90.7%), and married (230; 71.7%) (Table 1). The most common cancer type was gastrointestinal (118 patients; 36.8%), followed by lung (60 patients; 18.7%), genitourinary (39 patients; 12.1%), and breast (29 patients; 9.0%). At baseline, patients reported experiencing a mean (SD) of 3.31 (1.79) moderate or severe symptoms, with only 17 patients (5.3%) reporting no moderate or severe symptoms. More than one-fifth of patients had clinically significant symptoms of depression (71 patients; 22.2%) and anxiety (82 patients; 25.6%) based on their PHQ-4 scores. Few patients died during hospitalization (12 patients; 3.7%), with the remaining being discharged to home (253 patients; 78.8%), hospice (29 patients; 9.0%), or another facility (27 patients; 8.4%).

Figure. CONSORT Diagram.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Patients.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 161) | Intervention (n = 160) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.7 (13.1) | 64.5 (12.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 90 (55.9) | 90 (56.3) |

| Female | 71 (44.1) | 70 (43.8) |

| Race and ethnicity, self-report | ||

| African American | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| Asian | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| White | 141 (87.6) | 150 (93.8) |

| Othera | 10 (6.2) | 6 (3.8) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married or living with partner | 119 (73.9) | 111 (69.4) |

| Widowed | 9 (5.6) | 9 (5.6) |

| Divorced or separated | 19 (11.8) | 18 (11.3) |

| Never married | 12 (7.5) | 22 (13.8) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 0 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 41 (25.5) | 33 (20.6) |

| Part time | 11 (6.8) | 11 (6.9) |

| Retired | 69 (42.9) | 80 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 10 (6.2) | 7 (4.4) |

| Disability | 22 (13.7) | 22 (13.8) |

| Other | 8 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) |

| Educational level | ||

| <College graduate | 66 (41.0) | 60 (37.5) |

| ≥College graduate | 91 (56.5) | 100 (62.5) |

| Missing | 4 (2.5) | 0 |

| Annual income, $ | ||

| <60 000 | 45 (28.0) | 50 (31.3) |

| ≥60 000 | 71 (44.1) | 63 (39.4) |

| Missing | 45 (28.0) | 47 (29.4) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 58 (36.0) | 60 (37.5) |

| Lung | 31 (19.3) | 29 (18.1) |

| Genitourinary | 18 (11.2) | 21 (13.1) |

| Breast | 16 (9.9) | 13 (8.1) |

| Lymphoma | 12 (7.5) | 10 (6.3) |

| Skin | 9 (5.6) | 11 (6.9) |

| Head and neck | 8 (5.0) | 8 (5.0) |

| Sarcoma | 8 (5.0) | 5 (3.1) |

| Gynecologic | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) |

| Unknown primary type | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD), score | 0.96 (1.53) | 1.21 (1.58) |

Other included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or unanswered.

Effect of IMPROVED on Patient-Reported Symptom Burden

We found no significant differences between the intervention and usual care groups for the primary outcome of the proportion of days with improved symptoms (Table 2). We found no significant intervention effect on the proportion of days with improved ESAS-physical (unstandardized coefficient [B] = –0.02; 95% CI, –0.10 to 0.05; P = .56), ESAS-total (B = –0.05; 95% CI, –0.12 to 0.02; P = .17), PHQ-4–depression (B = –0.02; 95% CI, –0.08 to 0.04; P = .55), PHQ-4–anxiety (B = –0.04; 95% CI, –0.10 to 0.03; P = .29), and PHQ-4–total (B = –0.06; 95% CI, –0.13 to 0.01; P = .11) symptoms. The mean proportion of days with improved symptoms for each of the individual ESAS symptoms by study group is shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2.

Table 2. Effect of IMPROVED on the Mean Proportion of Days That Symptoms Improved.

| IMPROVED effecta | Score, mean (SD) | B (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS-physical | |||

| Usual care | 0.61 (0.36) | –0.02 (–0.10 to 0.05) | .56 |

| Intervention | 0.57 (0.33) | ||

| ESAS-total | |||

| Usual care | 0.66 (0.34) | –0.05 (–0.12 to 0.02) | .17 |

| Intervention | 0.60 (0.33) | ||

| PHQ-4–depression | |||

| Usual care | 0.23 (0.32) | –0.02 (–0.08 to 0.04) | .55 |

| Intervention | 0.21 (0.29) | ||

| PHQ-4–anxiety | |||

| Usual care | 0.26 (0.34) | –0.04 (–0.10 to 0.03) | .29 |

| Intervention | 0.21 (0.31) | ||

| PHQ-4–total | |||

| Usual care | 0.33 (0.36) | –0.06 (–0.13 to 0.01) | .11 |

| Intervention | 0.26 (0.32) |

Abbreviations: B, unstandardized coefficient; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; IMPROVED, Improving Management of Patient-Reported Outcomes Via Electronic Data; PHQ-4, 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Adjusted for baseline symptom score (for the respective symptom).

In addition, we found no significant differences in the mean day-to-day change in symptom scores during patients’ hospitalization (Table 3). We found no significant intervention effect on the mean daily change in ESAS-physical (B = 0.57; 95% CI, –1.10 to 2.24; P = .50), ESAS-total (B = 1.24; 95% CI, –0.69 to 3.16; P = .21), PHQ-4–depression (B = 0.03; 95% CI, –0.15 to 0.20; P = .76), PHQ-4–anxiety (B = 0.11; 95% CI, –0.09 to 0.31; P = .27), and PHQ-4–total (B = 0.13; 95% CI, –0.17 to 0.42; P = .41) symptoms. Furthermore, we did not find significant differences in the proportion of days in which patients reported any symptom worsening by 2 or more points from the previous assessment or any symptom scored 4 or higher (usual care, 95.4% vs IMPROVED, 92.9%; P = .19).

Table 3. Effect of IMPROVED on the Mean Day-to-Day Change in Symptom Burden.

| IMPROVED effecta | Score, mean (SD) | B (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS-physical | |||

| Usual care | –4.47 (8.65) | 0.57 (–1.10 to 2.24) | .50 |

| Intervention | –3.40 (8.41) | ||

| ESAS-total | |||

| Usual care | –6.24 (10.04) | 1.24 (–0.69 to 3.16) | .21 |

| Intervention | –4.50 (9.19) | ||

| PHQ-4–depression | |||

| Usual care | –0.07 (0.93) | 0.03 (–0.15 to 0.20) | .76 |

| Intervention | –0.04 (0.77) | ||

| PHQ-4–anxiety | |||

| Usual care | –0.16 (1.07) | 0.11 (–0.09 to 0.31) | .27 |

| Intervention | –0.02 (0.79) | ||

| PHQ-4–total | |||

| Usual care | –0.23 (1.52) | 0.13 (–0.17 to 0.42) | .41 |

| Intervention | –0.08 (1.30) |

Abbreviations: B, unstandardized coefficient; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; IMPROVED, Improving Management of Patient-Reported Outcomes Via Electronic Data; PHQ-4, 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Adjusted for baseline symptom score (for the respective symptom).

Effect of IMPROVED on Health Care Use

We did not find significant intervention effects on health care use. We found no significant differences in hospital LOS (usual care, 7.47 days vs IMPROVED, 7.59 days; B = 0.13; 95% CI, –1.04 to 1.29; P = .83) or risk of unplanned hospital readmissions (competing-risk regression) in 30 days (usual care, 33.8% vs IMPROVED, 26.5%; hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48-1.09; P = .12) and 90 days (usual care, 45.5% vs IMPROVED, 38.7%; hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.55-1.10; P = .15) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, IMPROVED did not have a significant effect on patients’ symptoms or health care use. Despite a well-designed and rigorously conducted study, this trial did not meet the primary end point of showing improvements in patients’ symptom burden, as measured by the proportion of days with improved symptoms, with an inpatient symptom monitoring intervention. In addition, IMPROVED did not significantly reduce patients’ hospital LOS or risk of unplanned readmission. Collectively, findings from this work do not support the routine integration of this type of symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. However, as the largest randomized clinical trial to date investigating a global symptom monitoring intervention in the inpatient oncology setting, this study provides important insights to inform future efforts to integrate symptom monitoring interventions using patient-reported outcomes into the care of patients with cancer.

Although the field of oncology has begun adopting efforts to integrate patient-reported outcomes into routine practice, the present study shows a lack of benefit for a symptom monitoring intervention in the inpatient setting. In our prior pilot study of IMPROVED, we found encouraging preliminary efficacy for this intervention, despite similar enrollment rates in the same population; thus, our present findings illustrate how pilot studies may overestimate benefits.52 Moreover, findings from the present study highlight the need for population-specific interventions because different patient populations have unique care needs meriting interventions designed to meet these needs.53,54,55 Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer clearly represent a highly symptomatic population, as evidenced by the high symptom burden among the patients in the present study.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,36 However, hospitalized patients uniformly receive intensive symptom management in the inpatient setting, which may negate the effect of systematic symptom monitoring.18 In addition, supportive care interventions may not have the same utility in the hospital setting as that of the outpatient setting, considering that the goals and care needs of inpatients and outpatients often differ.56,57,58 Thus, our findings in the present study underscore the importance of developing and testing population-specific supportive care interventions, particularly in the field of oncology, as patients’ care needs often differ by cancer type and stage as well as across care settings.

In addition, when designing patient-centered, population-specific interventions, researchers must carefully consider the details of the intervention and usual care provided. In the present randomized clinical trial, patients in both study groups reported their symptoms daily throughout their hospitalization using validated measures, and only patients assigned to the IMPROVED intervention had their symptoms presented to their clinical team. We did not provide guidance or feedback about managing patients’ symptoms or ask clinicians to document clinical actions in response to the symptom reports, which other studies have done,33,35,59 thus possibly limiting the potency of IMPROVED. In addition, we reported intervention patients’ symptoms to all members of their inpatient care team each day, including nurses, advanced practice providers, and physicians. Although this ensured that all members of the care team remained updated about patients’ symptoms each day, we never assigned a specific clinician to take responsibility for addressing the symptoms, and this could result in a diffusion of responsibility.60 For this study, we asked patients in the usual care group to also report their symptoms each day, which could have encouraged these patients to more proactively report their symptoms to their clinical teams than they otherwise would have done in the absence of the study. Thus, our findings with the IMPROVED symptom monitoring intervention should be interpreted within the context of the details of the care provided in both the intervention and usual care groups.

The selection of study outcomes may play a major role in determining the utility and meaningfulness of interventions involving patient-reported outcomes. We used the ESAS tool to monitor patients’ symptoms, and we selected the ESAS-physical symptom score as our primary outcome, which may have influenced our results, but other studies have successfully used this strategy.34,38 Prior studies of symptom monitoring interventions have used other symptom assessment tools, as no uniform tool exists for this work.26,27,28,29,59 Notably, symptom burden may not represent a readily modifiable study outcome in the inpatient oncology population, and IMPROVED may have resulted in benefits to other unmeasured outcomes, such as patient activation or satisfaction with care, even despite the lack of an effect of IMPROVED on symptom burden.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,35,36 Moreover, we did not power the current study to find significant effects on health care use, yet the differences in the rates of hospital readmissions appeared to favor the intervention, whereas hospital LOS was longer for patients assigned to IMPROVED, consistent with our prior work.38 Ultimately, IMPROVED did not result in detectable benefits in the present study, despite our selection of clinically important outcomes, which further supports the lack of a meaningful impact from this type of symptom monitoring intervention in the inpatient oncology setting.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study merit discussion. First, we conducted the trial at an academic center with limited sociodemographic diversity, thereby limiting the generalizability of our results. Patients with other racial and ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics as well as patients in other clinical settings may have experienced differential effects from this type of intervention. Second, we lack data regarding some factors that could influence the effect of IMPROVED, such as patients’ health literacy, prognostic understanding, physical and cognitive function, and level of caregiver involvement.61,62,63 Future studies should investigate whether those, and other important factors, such as cancer type and use of additional support services (eg, nutrition, palliative care, and physical or occupational therapy) influence the effect of IMPROVED. We chose symptom burden and health care use as important outcomes in the current study, but additional outcomes could be considered in future work, such as patient-clinician communication and coordination of care. In addition, we lacked information about how often clinicians discussed the symptom reports or developed a plan to address patients’ symptoms. Third, patients in our study had various cancer types with varying times since diagnosis with advanced disease, thereby limiting our ability to determine how best to personalize IMPROVED according to patients’ distinct care needs. Fourth, we did not collect information about postdischarge patient-reported outcomes or patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ perceptions of IMPROVED. Future efforts to integrate symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes into the care of patients with cancer should consider these key outcomes.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, we sought to determine the effects of IMPROVED on symptom burden and health care use among hospitalized patients with cancer. Few studies of inpatient symptom monitoring interventions exist, and the present study addressed this gap by investigating daily symptom monitoring in the inpatient oncology setting. The IMPROVED intervention did not show improvements in patients’ symptom burden, hospital LOS, or unplanned readmission. Notably, our data highlight the critical importance of efforts to address the symptomatic needs of hospitalized patients with cancer, as evidenced by these patients’ high symptom burden and willingness to participate in a symptom monitoring intervention, based on the high rates of study enrollment and completion of daily symptom assessments. Collectively, findings from this trial provide key insights to help guide future work investigating symptom monitoring interventions using patient-reported outcomes in oncology and demonstrate the lack of benefit for this type of symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Proportion of Days with Improved Symptoms

eFigure 2. Graphical Depiction of Competing Risk Regression for Readmissions

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Davis MP, Dreicer R, Walsh D, Lagman R, LeGrand SB. Appetite and cancer-associated anorexia: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1510-1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1665-1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):94-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nekolaichuk CL, Maguire TO, Suarez-Almazor M, Rogers WT, Bruera E. Assessing the reliability of patient, nurse, and family caregiver symptom ratings in hospitalized advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3621-3630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA, et al. A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1525-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooley ME, Short TH, Moriarty HJ. Symptom prevalence, distress, and change over time in adults receiving treatment for lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2003;12(7):694-708. doi: 10.1002/pon.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, Kasimis BS. Symptom and quality of life survey of medical oncology patients at a Veterans Affairs medical center: a role for symptom assessment. Cancer. 2000;88(5):1175-1183. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fodeh SJ, Lazenby M, Bai M, Ercolano E, Murphy T, McCorkle R. Functional impairments as symptoms in the symptom cluster analysis of patients newly diagnosed with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(4):500-510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lage DE, El-Jawahri A, Fuh CX, et al. Functional impairment, symptom burden, and clinical outcomes among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(6):747-754. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1907-1917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):496-503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, et al. Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(1):51-54. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Numico G, Cristofano A, Mozzicafreddo A, et al. Hospital admission of cancer patients: avoidable practice or necessary care? PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbera L, Paszat L, Qiu F. End-of-life care in lung cancer patients in Ontario: aggressiveness of care in the population and a description of hospital admissions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(3):267-274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modonesi C, Scarpi E, Maltoni M, et al. Impact of palliative care unit admission on symptom control evaluated by the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):367-373. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Moran SM, et al. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(23):4720-4727. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newcomb RA, Nipp RD, Waldman LP, et al. Symptom burden in patients with cancer who are experiencing unplanned hospitalization. Cancer. 2020;126(12):2924-2933. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen H, Johnson M, Boland E, Seymour J, Macleod U. Emergency admissions and subsequent inpatient care through an emergency oncology service at a tertiary cancer centre: service users’ experiences and views. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(2):451-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. ; SAGE Study Group. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1877-1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breetvelt IS, Van Dam FS. Underreporting by cancer patients: the case of response-shift. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(9):981-987. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52(3):319-324. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, Hsieh YC, Beer TM. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? a comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485-3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, Skorpen F, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson TM, Li Y, Coffey CW, et al. Reliability of adverse symptom event reporting by clinicians. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1159-1164. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0031-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Maio M, Gallo C, Leighl NB, et al. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):910-915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denis F, Basch E, Septans AL, et al. Two-year survival comparing web-based symptom monitoring vs routine surveillance following treatment for lung cancer. JAMA. 2019;321(3):306-307. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, et al. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up to routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9):djx029. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197-198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basch E, Stover AM, Schrag D, et al. Clinical utility and user perceptions of a digital system for electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring during routine cancer care: findings from the PRO-TECT trial. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:947-957. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1846-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, Velikova G. Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:122-134. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry DL, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Electronic self-report assessment for cancer and self-care support: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(3):199-205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.6662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strasser F, Blum D, von Moos R, et al. ; Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) . The effect of real-time electronic monitoring of patient-reported symptoms and clinical syndromes in outpatient workflow of medical oncologists: E-MOSAIC, a multicenter cluster-randomized phase III study (SAKK 95/06). Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):324-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Absolom K, Warrington L, Hudson E, et al. Phase III randomized controlled trial of eRAPID: eHealth intervention during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):734-747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(3):183-189. doi: 10.1007/BF00435383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164-2171. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Ruddy M, et al. Pilot randomized trial of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(2):274-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Electronic symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03396510. Updated February 9, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03396510

- 40.Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Johnson L, Myers J, Strasser F. A multicenter study comparing two numerical versions of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(2):456-468. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9. doi: 10.1177/082585979100700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hannon B, Dyck M, Pope A, et al. Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment System including constipation and sleep: validation in outpatients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(5):945-952. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a prospective, multicenter study. Cancer. 2015;121(17):3027-3035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mancini I, Bruera E. Constipation in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6(4):356-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMillan SC. Presence and severity of constipation in hospice patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19(6):426-430. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhondali W, Nguyen L, Palmer L, Kang DH, Hui D, Bruera E. Self-reported constipation in patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(1):23-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Fulfaro F. The course of symptom frequency and intensity in advanced cancer patients followed at home. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(2):104-112. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in the physical, emotional, and total symptom distress scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(2):262-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1-2):86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lage DE, Nipp RD, D’Arpino SM, et al. Predictors of posthospital transitions of care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):76-82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.0340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kistin C, Silverstein M. Pilot studies: a critical but potentially misused component of interventional research. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1561-1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauman J, El-Jawahri A. One size does not fit all: the need for population-specific palliative care interventions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1449-1450. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nipp RD, Temel B, Fuh CX, et al. Pilot randomized trial of a transdisciplinary geriatric and palliative care intervention for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(5):591-598. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nipp RD, Horick NK, Deal AM, et al. Differential effects of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention based on the age of patients with advanced cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):123-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905-912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120(11):1743-1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidal M, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Hui D, et al. Place-of-death preferences among patients with cancer and family caregivers in inpatient and outpatient palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare-2019-002019. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fallon M, Walker J, Colvin L, Rodriguez A, Murray G, Sharpe M; Edinburgh Pain Assessment and Management Tool Study Group . Pain management in cancer center inpatients: a cluster randomized trial to evaluate a systematic integrated approach—the Edinburgh Pain Assessment and Management Tool. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(13):1284-1290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stavert RR, Lott JP. The bystander effect in medical care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):8-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1210501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright JP, Edwards GC, Goggins K, et al. Association of health literacy with postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):137-142. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer LF, Dunn CL, Moss M. Preoperative cognitive dysfunction is related to adverse postoperative outcomes in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(1):12-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korc-Grodzicki B, Downey RJ, Shahrokni A, Kingham TP, Patel SG, Audisio RA. Surgical considerations in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2647-2653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.0962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Proportion of Days with Improved Symptoms

eFigure 2. Graphical Depiction of Competing Risk Regression for Readmissions

Data Sharing Statement