Abstract

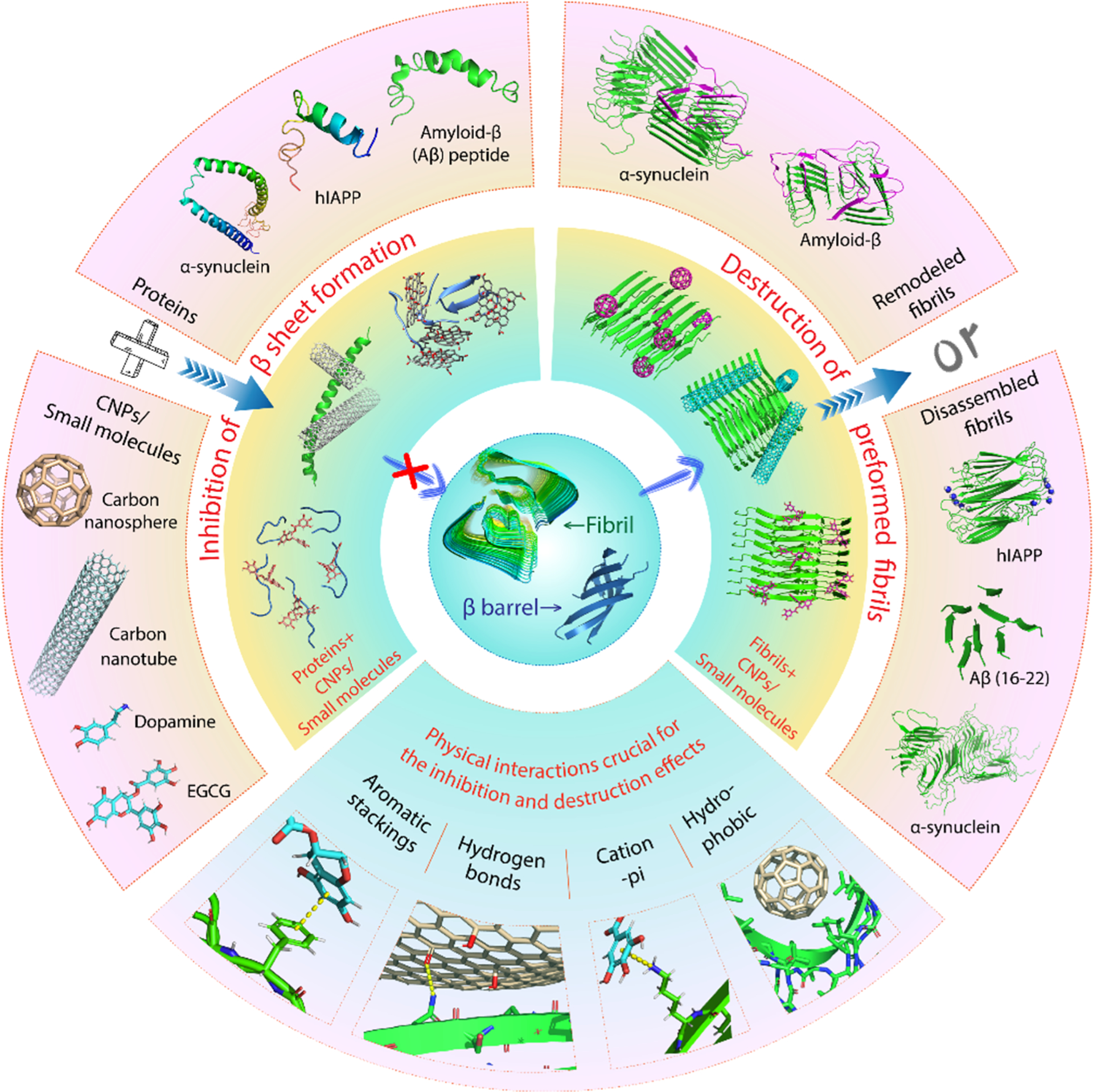

Protein misfolding and aggregation is observed in many amyloidogenic diseases affecting either the central nervous system or a variety of peripheral tissues. Structural and dynamic characterization of all species along the pathways from monomers to fibrils is challenging by experimental and computational means because they involve intrinsically disordered proteins in most diseases. Yet understanding how amyloid species become toxic is the challenge in developing a treatment for these diseases. Here we review what computer, in vitro, in vivo, and pharmacological experiments tell us about the accumulation and deposition of the oligomers of the (Aβ, tau), α-synuclein, IAPP, and superoxide dismutase 1 proteins, which have been the mainstream concept underlying Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), type II diabetes (T2D), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) research, respectively, for many years.

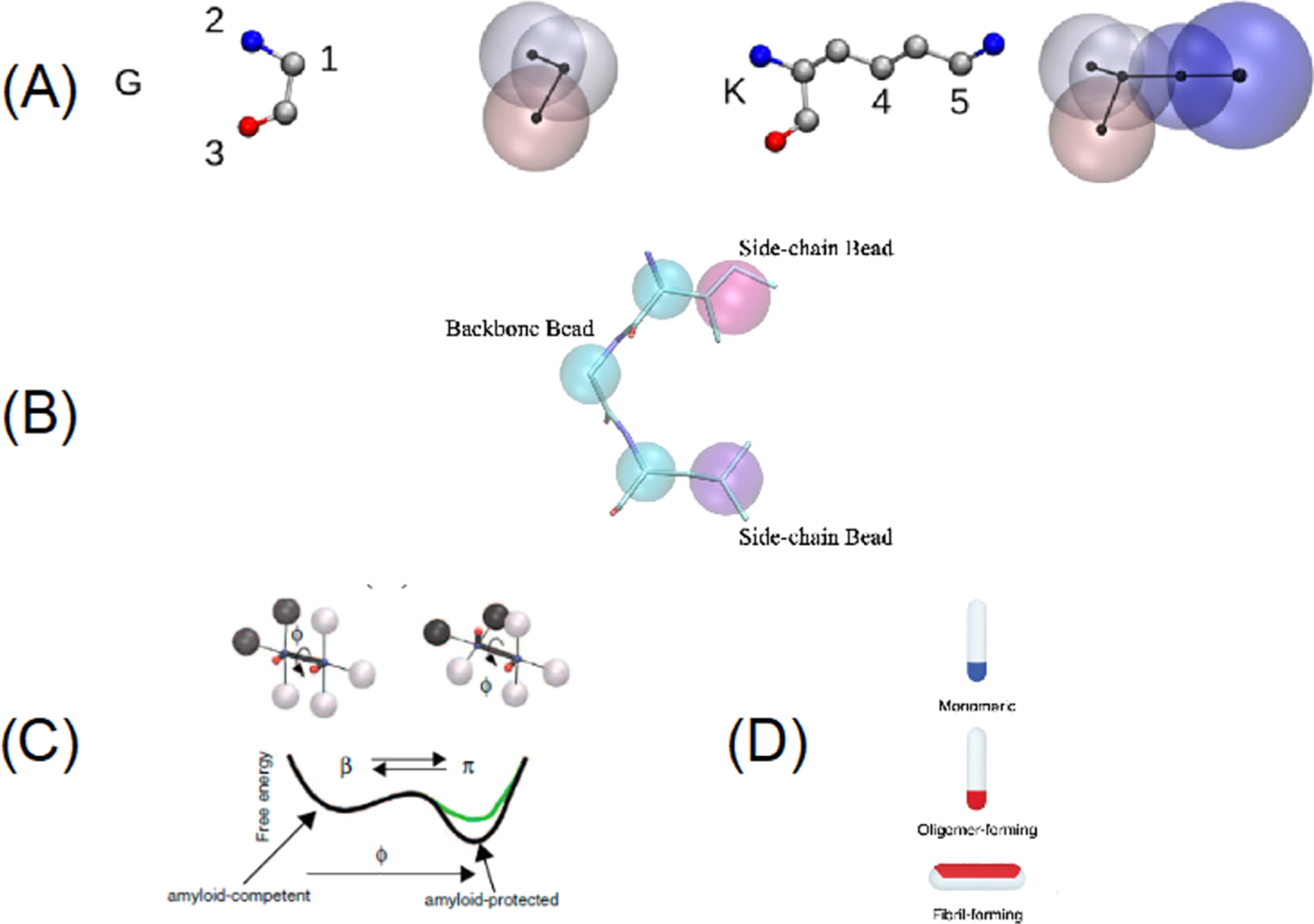

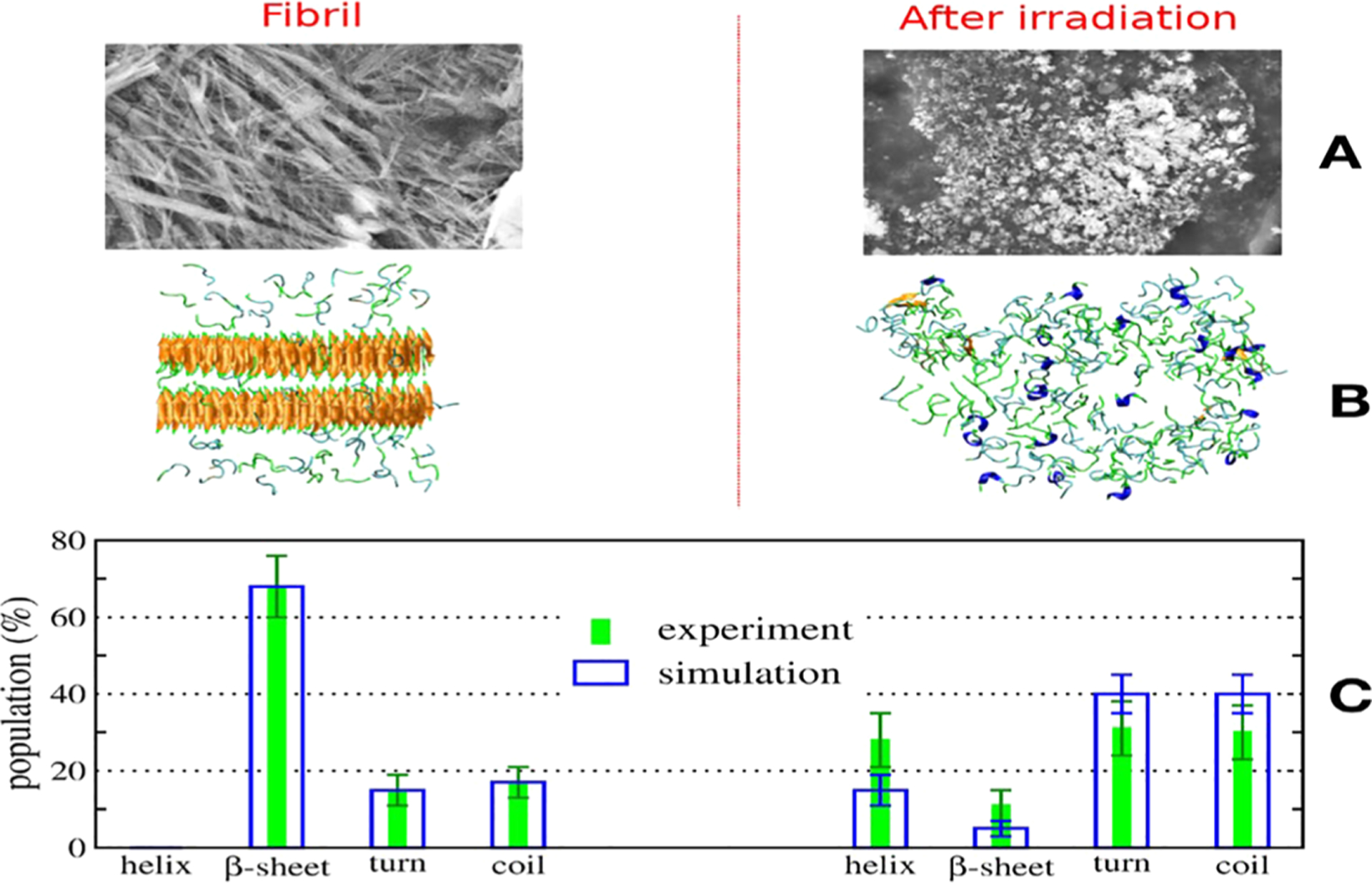

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The self-assembly of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) into extracellular or intracellular transient oligomers and amyloid fibrils is shared by many human diseases, including Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s (PD) diseases, type II diabetes (T2D), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and prion diseases.1 It is estimated that there about 50 and 10 million people worldwide living with AD and PD, respectively, and it was recently reported that AD can also be found in old chimpanzees.2 As citizens, we do not have an idea of its worldwide financial cost, but many of us know exactly the suffering for the patients and their families.

The history of senile dementia is very rich, dating back to the Greco-Roman period.3 However, AD was first described in 1906 by the German doctor Alois Alzheimer, PD was first described in 1817 by the English doctor James Parkinson, the French medical Professor Etienne Lancereaux is the pathfinder of T2D in 1877, and ALS, also named “maladie de Charcot” or “Lou Gehrig’s disease (American baseball player)”, was first described by Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris in 1874.

The key misfolded proteins are clearly identified for each disease: the Aβ protein (Aβ40 and Aβ42 with 40 and 42 amino acids) and the tau protein ranging from 352 to 421 amino acids in AD, the 140 amino acid α-synuclein (αS) protein in PD, the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) or amylin of 37 amino acids in T2D, and the superoxide dismutase 1 of 32 kDa (SOD1), TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TPD-43), and 526 amino acid fused in sarcoma protein (FUS) in ALS. The first authors to correlate Aβ and αS proteins to AD and PD were Glenner and Wong,4 Goldberg and Lansbury,5 and Hardy and Selkoe,6 and the implications of the other proteins are reviewed in refs7–9. Their sequences do not have any homology and are very diverse in length, yet they all share the ability to form amyloid deposits or inclusions in the brain or the tissue (T2D) of patients, the exception being the wild-type SOD1 protein, but the monomeric apo-SOD1 in its disulfide-reduced state forms fibrillar aggregates under near quiescent conditions.10

In vitro, the Aβ, tau, αS, IAPP, TDP-43, and FUS proteins form readily cross-β structures with an aggregation kinetics profile typically displaying a sigmoidal curve where the proteins assemble into oligomers (lag-phase) prior to fibril elongation (growth phase) and a plateau where the fibrils and free monomers are in equilibrium (saturation phase), as shown in many reviews.11,12 Amyloid fibrils display an intermolecular hydrogen-bond (H-bond) network parallel to the fibril axis. The molecular mechanisms leading to amyloid fibrils are well described by primary nucleation, (fragmentation and surface-catalyzed) secondary nucleation, and elongation growth mechanisms as shown elsewhere.13 The aggregation kinetics and the lifetimes of the heterogeneous conformations of all oligomers along the amyloid fibril formation pathways are very sensitive to the amino acid length (e.g., Aβ42 vs Aβ40) and genetic risks, including several mutations in Aβ, αS, and SOD1 proteins and one unique mutation in IAPP, the level of hyperphorylation in tau and SOD1, and acetylation and glycosylation in tau. Experimental conditions modulate the self-assembly process, such as pH, T, peptide concentration, external applications resulting from agitation, electric field and shear forces, and the presence of membrane, metal ions, crowding, and heparin (for tau, in particular).14–16

Until 20 years ago, it was believed that the ability to form amyloid fibrils was restricted to a few proteins involved in diseases. However, there have been many more recent reports that nondisease proteins, short peptides, and even single amino acid homopolymers can form fibrils under appropriate conditions,17,18 and changing experimental conditions lead to nanotubes and ordered nanomaterials.19,20 Many studies have indicated the strategies and the selection pressures that protein sequences (either alone or helped by chaperones) have followed to avoid undesired aggregation, to adjust the kinetic and thermodynamic stability of their well folded three-dimensional (3D) structures, and to optimize the efficiency of their folding pathways.21

However, the emergence of amyloid folds is not a surprise for several reasons. They allow a variety of functional roles in both prokaryote and eukaryote organisms.22 Amyloids are able to replicate and catalyze their own formation, transmit information, and provide a scaffold for chemical reactions (e.g., ester hydrolysis) and enzyme-like activities.23–25 Even under early earth (prebiotic) conditions, peptides can form amyloid fibrils leading to the current amyloid world hypothesis in the origin of life26,27 and the possibility that all globular protein structures may have originated from amyloid fibrils.28

While SOD1 is a globular protein with a well-defined 3D structure, the Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein proteins belong to the class of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). IDPs are also known to play a critical role in many cellular functions, such as signal transduction, cell growth, binding with DNA and RNA, and transcription, and are implicated in the development of cardiovascular problems and cancers.29 The IDPs involved in neurodegenerative diseases have a few aggregation-prone regions, and overall all IDPs have a low mean hydrophobicity and a high mean net charge.30

IDPs are structurally flexible and lack stable secondary structures in aqueous solution. When isolated, they behave as polymers in a good solvent and their radii of gyration are well described by the Flory scaling law.31 The insolubility and high self-assembly propensity of IDPs implicated in degenerative diseases have prevented high-resolution structural determination by solution nuclear magnetic resolution (NMR) and X-ray diffraction experiments. Local information at all aggregation steps can be, however, obtained by chemical shifts, residual coupling constants, and J-couplings from NMR, exchange hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) NMR, Raman spectroscopy, and secondary structure from fast Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) or circular dichroism (CD). Long-range tertiary contacts can be deduced from paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR spectroscopy and single molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (sm-FRET), and short-range distance contacts can be extracted by cross-linked residues determined by mass spectrometry (MS). Low-resolution 3D information on monomers and oligomers can be obtained by ion-mobility mass-spectrometry data (IM/MS) providing cross-collision sections, dynamic light scattering (DLS), pulse field gradient NMR spectroscopy, and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) providing hydrodynamics radius, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) providing height features of the aggregates, as reported by some of the first and recent applications of these methods to IDPs.32–38 However, the information obtained from most experimental observables represents an average over the free energy landscape and gives time- and space-averaged properties. Experiments can also lead to different values of properties, for example the radius of gyration (Rg) as a result of the equilibrium between the monomeric and multimeric states of the IDPs under the conditions used. Fibril structures of long amyloid proteins are mainly proposed based on solid-state NMR (ssNMR) with the first high resolution structure of HET-s(218–289) prion39 and on cryo-electron miscroscopy (cryo-EM) experiments.40,41 Fibril structures of short amyloid peptides were also determined by X-ray diffraction analysis.42

Computer simulations at different time and length scales can in principle provide the dominant microstates of IDPs using multiple sampling techniques and various representations ranging from all-atom and coarse-grained (CG) to mesoscopic models.12,14,43–45 However, they are limited by the accuracy of the force field and the size of the energy landscape to be explored. Even on the fastest Anton computer, the simulation time using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations does not exceed 1 ms for a monomeric protein of 76 amino acids,46 i.e., several orders of magnitude less than the time scales of hours and days required for fibril formation in vitro at a μM concentration.11

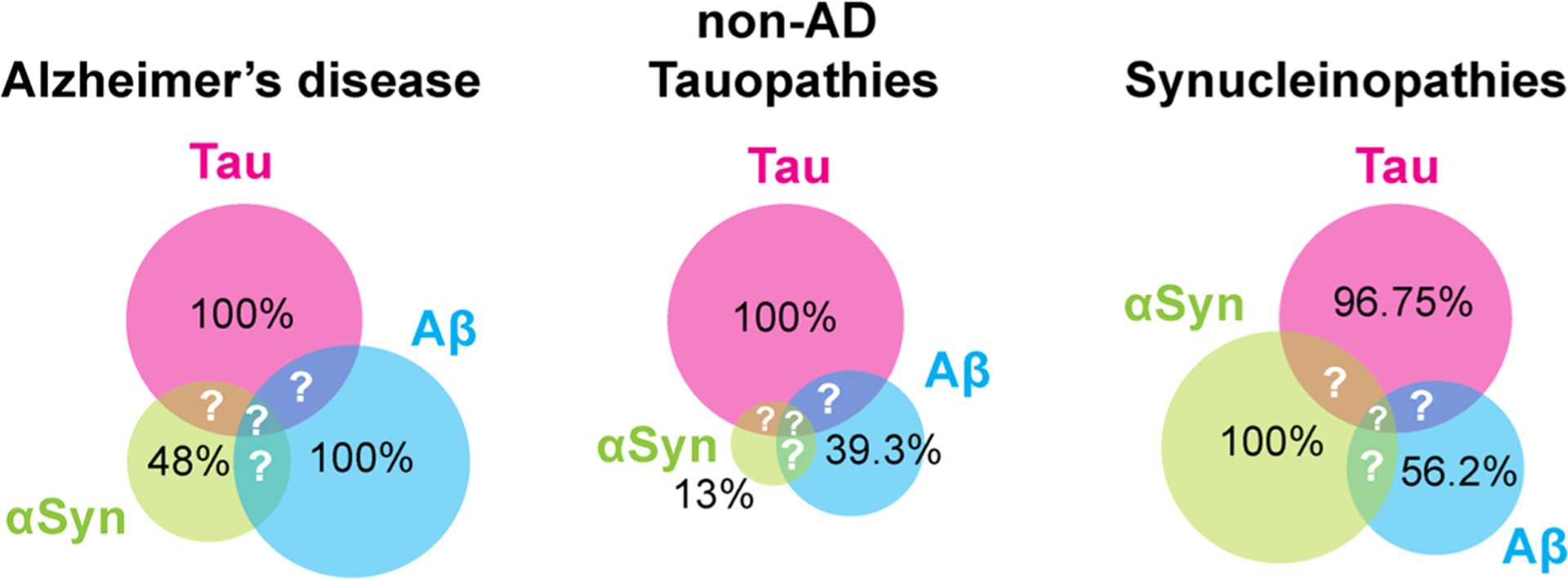

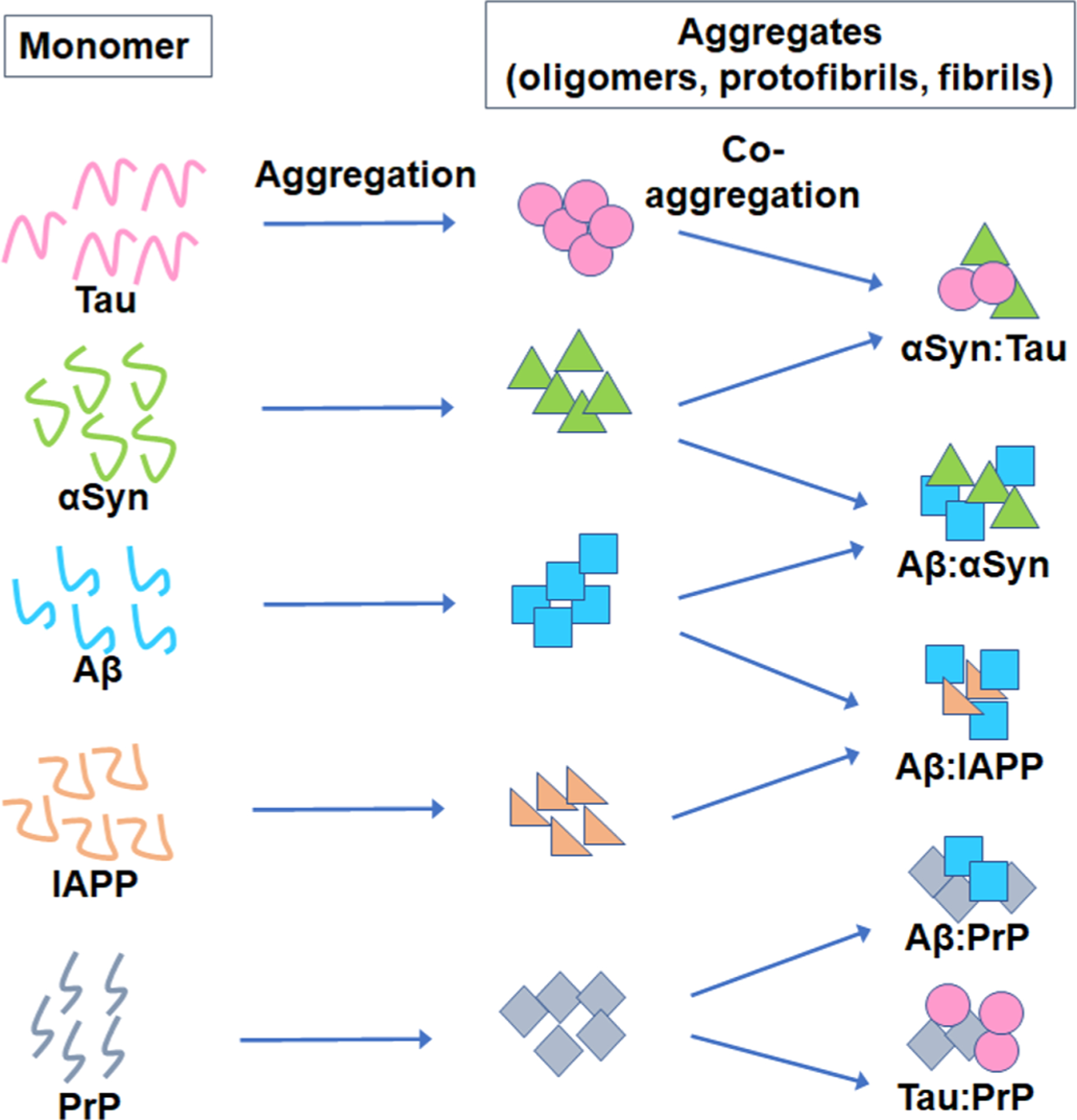

The most currently accepted hypothesis is that accumulation of oligomers of the key proteins is the primary cause of AD, PD, T2D, and ALS diseases and initiates a series of events leading to neuronal or tissue death, a view pioneered by Golberg and Lansbury5 and reviewed more recently.47–50 There is also growing evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies of co-occurring pathologies across common neuogenerative diseases,51 indicating cross-talk between the amyloid proteins and interactions and cross-seeding between the Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein proteins which promote aggregation, generate different strains, and accelerate cognitive dysfunction.52–54

In summary, we provide an in-depth overview of our current knowledge on the biogenesis and domain organizations of Aβ, tau, α-synuclein, and IAPP related to their aggregation and binding properties, the molecular structures of amyloid monomers, oligomers and fibrils implicated in AD, T2D, and PD from experiments and simulations, as well as the early and final aggregation steps using coarse-grained simulations. We will not provide all the answers to the questions that we are facing, nor describe all the protein cellular partners interacting with these amyloid proteins, but we will discuss what experiments and simulations tell us about the role of liquid–liquid phase separation, the effect of crowding and shear flow, and the role played by the cell membranes and the Zn and Cu metal ions on protein aggregation. Next, we discuss what we know about ALS etiology and present a pharmacological perspective to cure these diseases considering small compounds, antibodies, or physical methods. This is followed by recent findings on crosstalk between amyloid proteins from in silico to in vivo experiments. We conclude with a series of unanswered questions that can potentially be handled by simulations and experiments, discuss the alternative hypotheses to amyloid oligomers causing human diseases, and list future directions.

2. Aβ BIOGENESIS AND DOMAIN ORGANIZATIONS OF TAU, α-SYNUCLEIN AND IAPP

2.1. Aβ Biogenesis: Role of Pathogenetic and Protective Mutations, Membrane Composition, and Detailed Interaction with γ-Secretase (gS)

2.1.1. Generation of Aβ Peptides by gS.

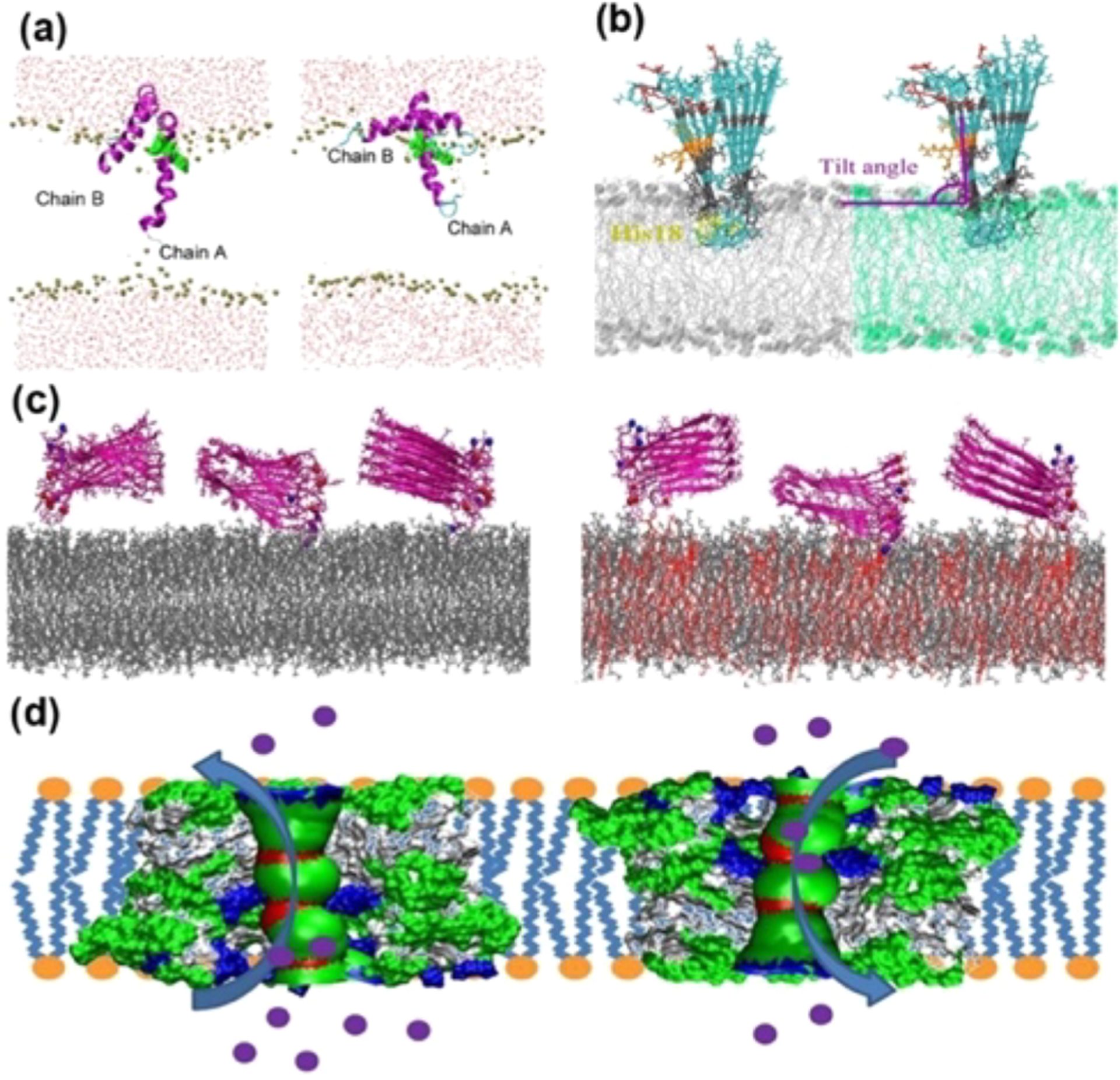

It is established that amyloid β protein (Aβ) contributes to the dysfunction and degeneration of neurons and the pathogenesis of AD.6,55–57 Aβ is derived from the proteolytic cleavage of the single-pass transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) by secretases and may be processed along nonamyloidogenic and amyloidogenic pathways. The nonamyloidogenic pathway involves initial cleavage of APP by α-secretase (aS) leading to formation of sAPPα and the 83 amino acid fragment APP-C83. The amyloidogenic pathway involves initial cleavage of APP by β-secretase (bS) leading to formation of sAPPβ and the 99 amino acid fragment referred to as CTF99, APP-C99, or simply C99. Cleavage of C99 by γ-secretase is the last step in the production of Aβ (Figure 1).

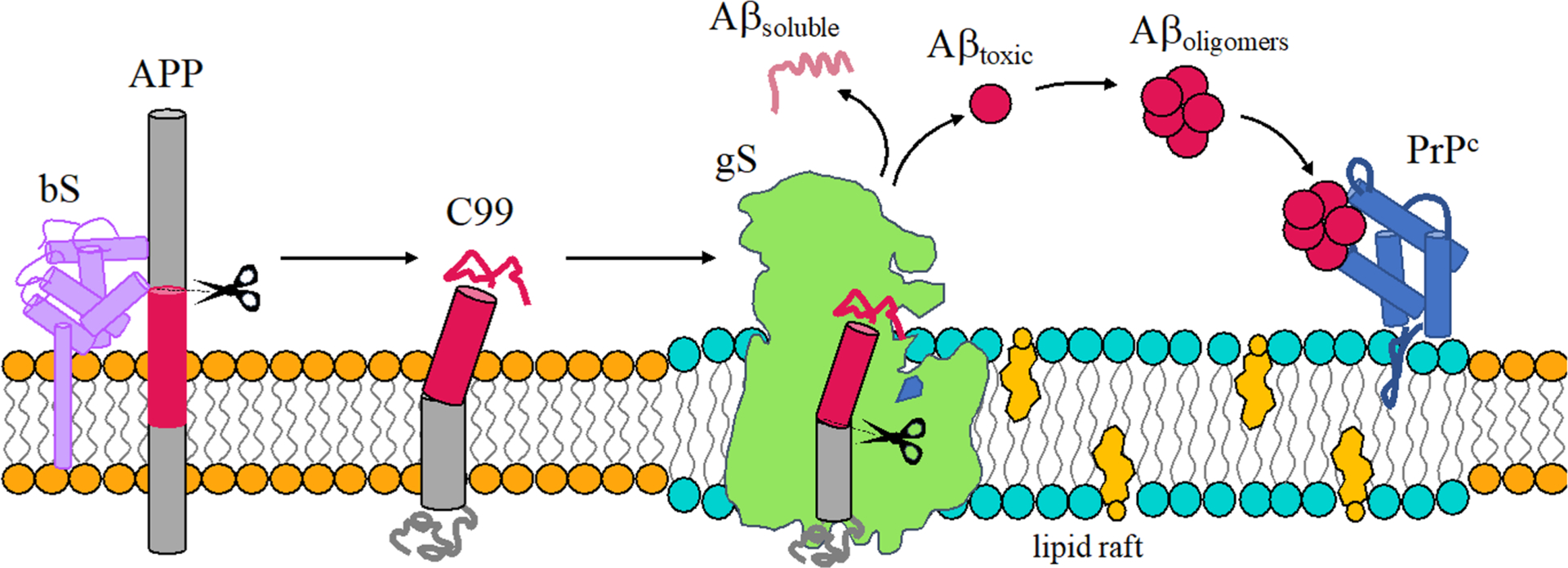

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the amyloidogenic processing of APP. Aβ is produced by sequential processing of APP by bS and gS to produce either a soluble and nontoxic mixture of Aβ or a more amyloidogenic Aβ mixture with a propensity to form oligomers that bind PrPc and potentially induce AD.

Cleavage of C99 by gS lacks fidelity.58–60 Cleavage of C99 by gS is initiated at the ε-sites (gS endopeptidase activity) to produce the amyloid intracellular domain (AICD) and Aβ49 or Aβ48 peptides. After the first cut, tri- and tetrapeptides are generated from sequential cleavage (gS carboxypeptidase-like activity) until Aβ proteins are released to the extracellular environment.61 Cleavage of C99 results in a variety of Aβ isoforms with Aβ40 being most prevalent and Aβ42 being a minor but more amyloidogenic form. Sequential cleavage by gS at points separated by roughly 0.5 nm results in a specific isoforms of Aβ. C99 is produced along two main cleavage lines Aβ49 > 46 > 43 > 40 and Aβ48 > 45 > 42 > 38 (Figure 2, panel 2D). The first is responsible for the release of the major isoform Aβ40 and the second leads to the minor isoforms Aβ42 and Aβ38.62

Figure 2.

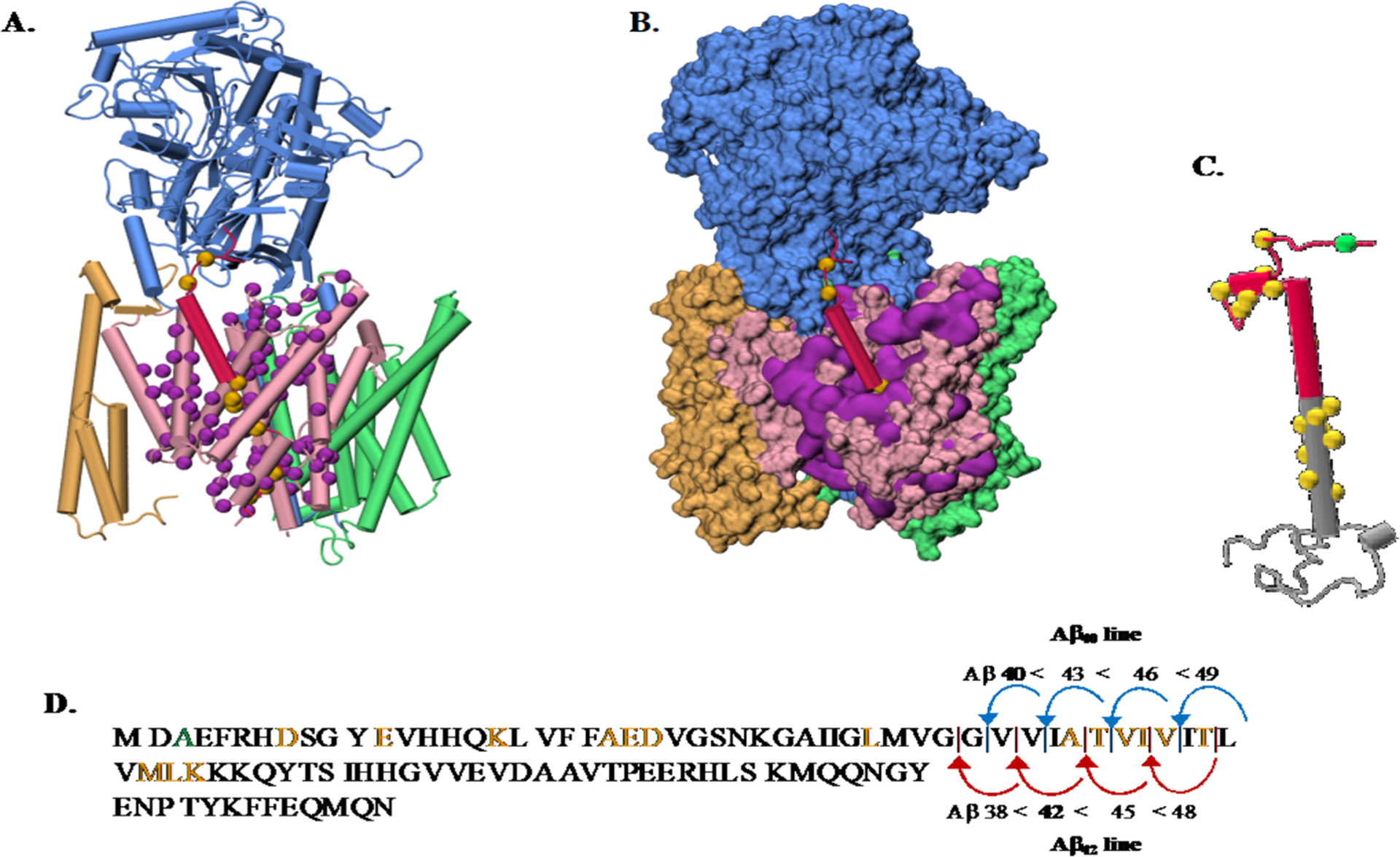

(A) Overview of the gS and APP structures and pathogenic AD mutations. (A) Depiction of the gS complex (PDB 6IYC).95 NCT subunit (blue), APH-1A (green), PEN-2 (yellow), and the catalytic PSN subunit (pink) bound to a C99 fragment (red). C-alpha atoms from the PSN disease-causing mutations139 that affect C99 processing are shown (purple spheres). C99 disease causing mutations available in the 6IYC structure are shown (yellow spheres). (B) gS structure with the same color code as part A in a surface representation. (C) Depiction of a C99 structure model (gray) with the Aβ sequence highlighted (red). C-alpha atoms from disease causing mutations are shown in yellow spheres with the protective Icelandic mutant (green). (D) C99 sequence with mutations highlighted in the same color code representation and showing the two main Aβ production lines. The structures in parts A, B, and C from the PDB were drawn using VMD.140

The observed infidelity in the cleavage of C99 may result from variation in the points of initiation and termination of cleavage, which in turn may be influenced by a variety of factors. Interestingly, gS is also known to process a wide variety of substrates,63–66 some of which are cleaved with high fidelity, suggesting that substrate sequence plays a primary role. A minimal model of the transmembrane domain of C99, Glu22-Lys55, is required for cleavage by gS, and importantly, negative charges on the extracellular side and positive charges on the intracellular side are required.67 The polybasic regions on the C-terminal side of TM helices are globally found in gS substrates68 and are conserved in both C99 and the Notch family. MD simulations have shown that following the first cleavage step the substrate is pulled deeper into the binding cavity of PS1. Negative charges at the N-terminus are observed to remain in place during the processing process.69 These observations support the conclusion that the N-terminal 21 amino acids of C99 are not required for gS cleavage.70

Evidence suggests that the mature gS complex is active at the plasma membrane and in endosomes71–73 and that cleavage of C99 by γ-secretase most commonly occurs when the enzyme and the substrate are colocalized in cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains. Therefore, while an important contributing factor to AD is mutation of APP or gS, alterations in the lipid membrane environment in which APP and gS are embedded also play a critical role. The actual products of APP cleavage depend on the specific membrane environment.74

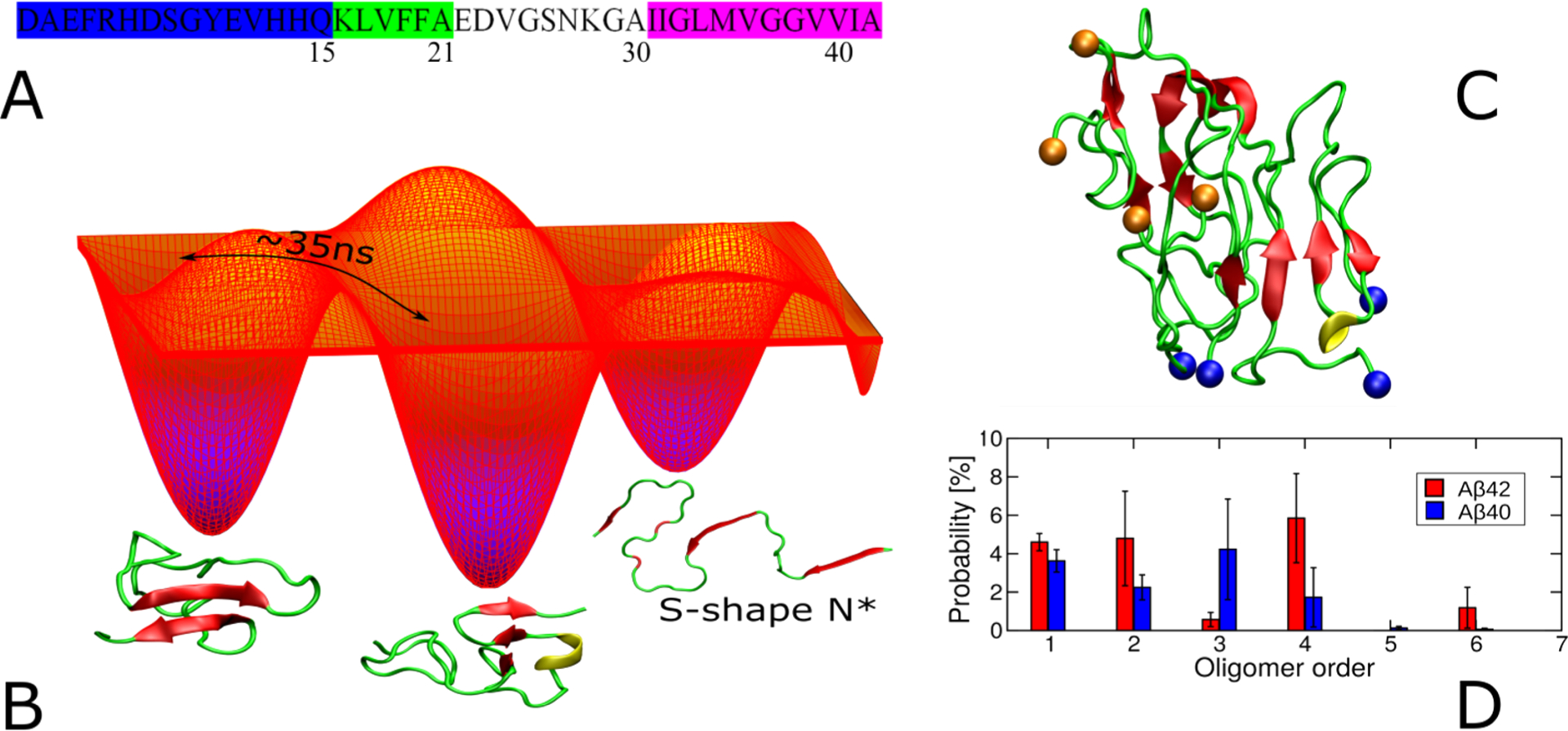

While Aβ has long been implicated as a pathogenic agent in AD, the molecular mechanism by which Aβ induces neuronal dysfunction largely remains a mystery.75–79 One focus has been to characterize the structural ensembles of Aβ40 and Aβ42 monomers using experimental NMR and computational studies80,81 with an eye on identifying aggregation prone structures termed N* states.82 Given the role of the monomer ensemble in identifying aggregation prone sequences (N* conjecture), one promising putative mechanism for Aβ cytotoxicity involves the binding of Aβ oligomers with cellular prion protein PrPC83 leading to activation of a kinase and the abnormal phosphorylation of tau (see section 2.2).

2.1.2. Impact of Disease-Causing Mutations on APP and gS.

APP pathogenic mutations were the first to be recognized to cause early onset AD which led to the amyloid hypothesis.84–87 APP mutations are observed to be clustered near the aS, bS, and gS proteolytic cleavage sites and can be categorized according to location in the APP structure, including mutations located in the (1) APP extracellular region and (2) APP transmembrane fragment N-terminal to the Aβ42 cleavage site that typically have little effect on C99 cleavage. In addition, (3) the transmembrane C-terminal fragment below the Aβ42 cleavage site is a hotspot of familial AD (FAD) mutation and has been proposed to be important as the main gS recognition site. This latter region has also been proposed to be the region that determines the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio by distorting the relative efficiencies of the ε-cleavage sites at C99 residues 48 or 49. Mutations that remove the positive charges from the invariant lysine or arginine residue located at the C99 TM junction greatly compromise the cleavage efficiency of gS.

2.1.3. Role of Mutations to APP and gS.

The majority of pathogenic APP mutations decrease the overall cleavage of C99 by gS, meaning that they are loss-of-function (LOF) mutations.68 Interestingly, the protective Icelandic mutation A673T was discovered in an individual with Down Syndrome (DS) who did not develop early onset AD related degeneration. Individuals with DS carry an extra copy of chromosome 21, and therefore, they also carry an extra copy of the gene for APP. This Aβ-lowering APP mutation is located in the APP extracellular region, close to the bS cleavage site and has been identified in the Islandic population.

PS1 pathogenic mutations modify substrate recognition, enzyme structure, or catalytic activity. These mutations result in partial or total loss-of-function of the enzyme. Before 2015, there was no structure available for gS. At this time, eight human gS structures have been determined by cryo-EM with a resolution range between 2.6 and 4.4 Å. gS is a transmembrane protein with four components.88–90 (1) Nicastrin (NCT) has been proposed to be in charge of substrate sorting, acting as a gatekeeper by sterically obstructing the access of proteins with large extracellular domains.91 (2) Anterior pharynx defective-1 (APH-1A) is required for the gS complex stability. Computational studies showed that it contains a water cavity able to transport water and store cations.92 (3) Presenilin (PS1) contains two aspartate residues that form the active site. (4) Presenilin enhancer 2 (PEN-2) is needed for the autocatalytic maturation.93,94 The recognition of APP by gS is illustrated in Figure 2A.95 180 mutations occurring in the PS1 subunit have been linked to familial AD.

Pathogenic PSEN-FAD mutations may affect gS endopeptidase activity (and the initial ε-cleavage site) and consistently impair the carboxypeptidase-like efficiency. This results in reduced processivity of Aβ49 or Aβ48 and the release of longer and more toxic Aβ43 or Aβ42 isoforms. These mutations result in the partial or total loss-of-function of the gS enzyme. PS1 mutants are dispersed among the whole gS structure, but those located at the gS complex surface may point to a substrate interaction/recognition site (Figure 2A and B).

While mutations to APP and gS mutations are known to modify C99 processing by gS, the details of how various mutations impact the cleavage process are still unknown. The disperse distribution of the mutation sites suggests that there should be a variety of mechanisms. (1) Disturbed PS1/APP interactions96 act by changing the preference of the initial position of the ε-cleavage site (gS endopeptidase activity). It has been proposed that APP mutations modify the tilting of the TMD helix, thereby altering the presentation of substrate to the proteolytic enzyme changing the initial ε-cleavage site. Alternatively, the mechanism of substrate docking and displacement toward the catalytic site may be impacted, as there is evidence that the substrate binding site is distinct from the catalytic active site. Once the substrate is docked, it is subsequently displaced to the catalytic site of the enzyme.97 (2) Loss of gS carboxypeptidase activity interferes with the catalytic efficiency, releasing premature intermediate and longer APP products.98 (3) Inhibitory effects at the initial ε-cleavage sites may lead to changes in the distribution of Aβ isoforms critically impacting aggregation kinetics and toxic effects.99 (4) Finally, catalytic cycle impairment may lead to alterations in the gS product lines.98

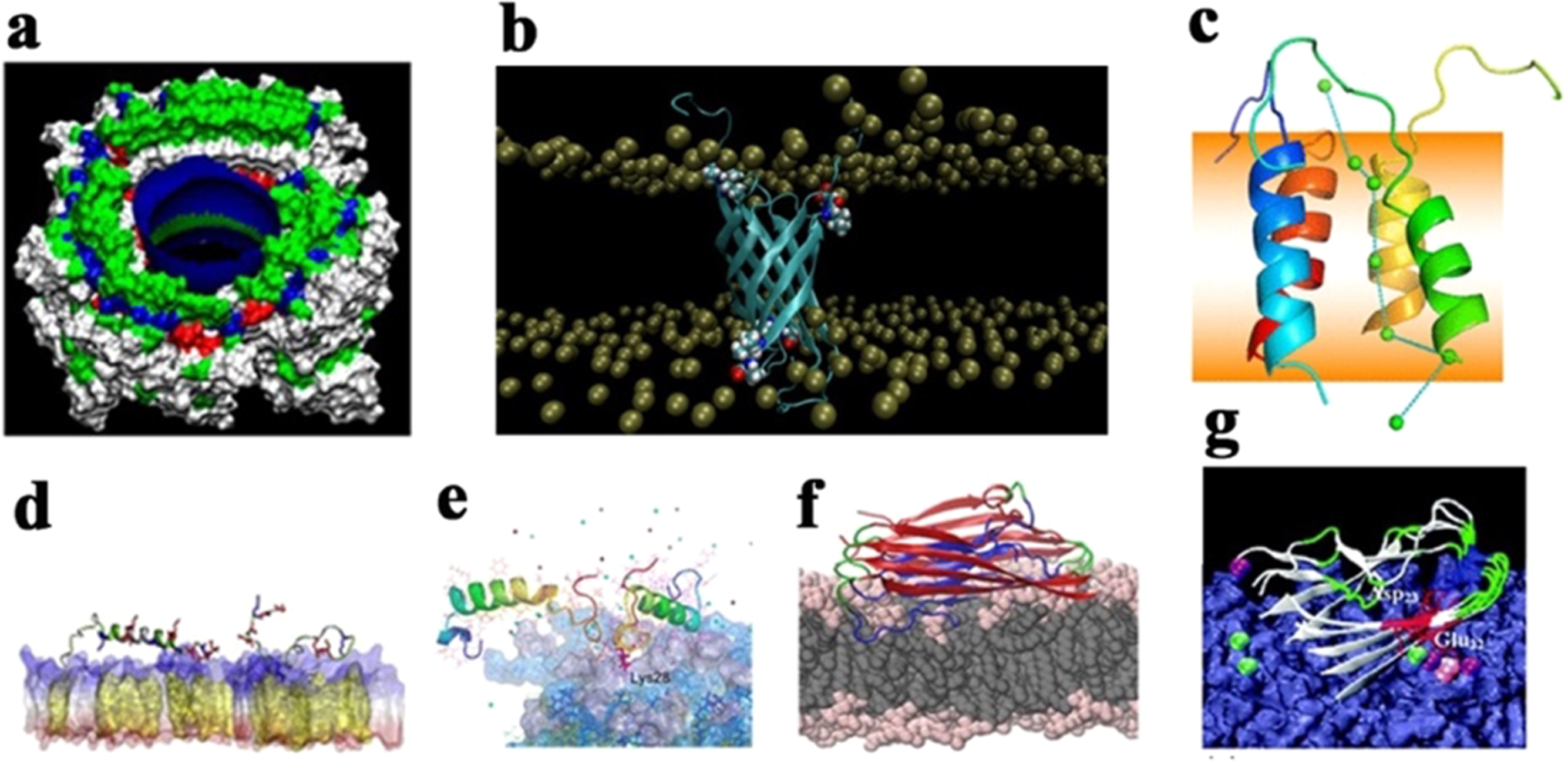

2.1.4. Role of Membrane in Aβ Genesis and Aggregation.

Early experimental63 and computational100 studies demonstrated that C99 consists of an extracellular region, including asparagine glycosylation sites, an extracellular juxtamembrane (JM) helical domain Q15–V21 (Q686–V695), an TM domain K28–K53 (K699–K724), and an intracellular C-terminal domain in model membranes (Figure 2C). Using ssNMR experiments, Tycko and co-workers suggested that, for the construct containing 27 residues K28–K55 (K699–K726) in multilamellar vesicles, the TM domain of APP adopts a mixture of helical and nonhelical structures,101 which varies as temperature is altered. Smith and workers reported NMR and FTIR data of the wild type (WT) construct N1–K55 (N672–K726) and the Flemish mutant A21G (A692G).102 They observed that at least part of the JM domain assumes a β-strand structure. Recent simulation results provide some support for this intriguing observation.103

Variations in sequence of C99 impact dimerization of the C99 TM domain, altering not only lateral mobility of the protein but also its TM helical structure (tilt and kink), C99 dimer structure and stability, and the structure of the TM helices within the dimer.100,104 There is evidence that changes in the stability of the C99 dimer influence its cleavage by gS and the resulting overall level of Aβ protein and its isoform distribution.101,104,105 Multhaup et al. first recognized that modifications in sequence that reduced homodimer affinity impacted cleavage of C99 by gS.106 Subsequent studies of homodimer formation in WT and mutant C99 congeners supported the view that C99 homodimerization is critical to C99 processing by gS and Aβ formation.107,108 However, it has been argued that C99 homodimerization is weak and may be largely irrelevant in vivo, suggesting that C99 monomer is the sole substrate for gS in the production of Aβ.109 There is little doubt that C99 homodimer is an essential species in the overall ensemble of C99 structures.107–111 More recently, Sanders et al. reported an ensemble of coexisting C99 monomer, dimer, and large-scale oligomers in lipid bicelles.112

2.1.5. Role of Membrane and Cholesterol on APP.

The role of membrane and cholesterol on APP has been examined in computational studies of C99 monomer and dimer structure in membrane and micelle environments as a function of protein sequence and composition of the lipid environment.103,110,113,114 Many of the observations derived from simulations have been validated using NMR experiments, including the existence of a flexible “hinge” region in the C99 monomer structure,113,114 the first C99 homodimer structure in a bilayer environment,113 and the ability to “environmentally select” C99 topologically distinct homodimer structures in membrane environments of varying lipid composition.114

Enhanced levels of cholesterol resulting from diet, genetic predisposition, or aging are positively correlated with early onset of AD.115–117 A variety of theories have been proposed to explain these observations. Lower levels of cholesterol promote membrane fluidity and nonamyloidogenic cleavage of APP by aS.118,119 In addition, decreased levels of cholesterol diminish both bS and gS activity and deplete cholesterol rich lipid raft microdomains deemed important for colocalization of gS and its substrate C99.62,120,121 Finally, site-specific binding of cholesterol to C99 protein has been observed. It has been proposed that elevated levels of cholesterol may increase the population of C99–cholesterol dimers,109,122 thus enhancing the partitioning of C99 to lipid raft domains and the proteolytic cleavage of C99 by gS to produce Aβ.

Membranes comprising these distinct cellular domains are composed of a mixture of lipids, including glycerolipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol. The complex lipid mixtures are characterized not by a uniform mixture but by a heterogeneous mosaic of liquid-disordered regions and liquid-ordered microdomains of varying lipid composition, including regions rich in saturated lipids, sphingomyelin, and cholesterol referred to as detergent-resistant membranes or lipid rafts. Many studies120,123–127 have proposed a role for raft domains in the biogenesis of Aβ. However, their influence on the mechanism of creation of Aβ is not understood.

Current evidence suggests that the mature gS complex is active at the plasma membrane and in endosomes. However, the actual product of APP cleavage depends on the specific membrane environment. In addition, there is substantial evidence that cleavage of C99 by gS most commonly occurs when the enzyme and substrate are colocalized in cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains.

The enzyme bS possesses a single transmembrane anchoring domain. It has been observed in the plasma membrane and endosomes colocalized with APP in regions where the membrane is enriched in lipid raft domains. Like bS, APP possesses a single transmembrane domain and is found in a variety of locations in the cell including in lipid raft domains, colocalized with the enzymes bS and gS. It was recently proposed that a complex of βS and gS formed in cholesterol rich membrane domains might lead to substrate shuttling and enhanced efficiency in the biogenesis of Aβ.128 Taken together, these observations demonstrate the important role played by membrane spatial heterogeneity in Aβ genesis.

2.1.6. Role of Membrane on gS.

gS is accountable for the final step in the regulated intramembrane proteolysis of APP to generate Aβ. As such, substantial attention has focused on understanding how the lipid environment modulates gS activity, including variations in the membrane lipid composition and the presence of cholesterol and sphingolipids.66,129 Clinical and experimental studies suggest that lipid composition is altered in AD brain tissue130 and that the production of Aβ peptides varies with the membrane composition.131 The mechanism explaining these observations and the exact cause or consequence have not been determined. Holmes et al. reported that the composition of lipid bilayers has profound and complicated effects on the production of Aβ peptides by gS.132 Both the fatty acyl chains and headgroups of the bilayer can regulate proteolysis of the intramembrane protease. gS has very low activity when embedded in fatty acyl chain lengths below 14 carbons then activity rises in a bell-shaped form and decreases again at 22 carbons. It has also been proposed that the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio decreases as the FA chain length increases. Thicker hydrophobic membranes, together with a reduced fluidity induced by modification of the head groups, retain longer Aβ species and allow subsequent gS cleavage to shorter isoforms. In the same study, Holmes et al. found that the double bond isomer in a phospholipid fatty acyl chain also influences the gS activity modifying the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratios. Similarly, the presence of cholesterol in a membrane leads to a considerable increase in gS activity that decreased at higher concentrations producing a bell-shaped form in the gS activity.132

Computational modeling approaches have made an effort to characterize changes in the gS conformational states while varying the bilayer lipid composition.69,133 Aguayo et al. found that bilayer lipid composition has a large impact on the gS structural ensemble and proposed that lateral pressure across the bilayer and the protein-bilayer hydrophobic mismatch regulate the proteolytic enzyme.133 Higher transmembrane lateral pressures restrain the gS dynamics and favor active state conformations of the PS1 catalytic subunit, which may explain experimentally observed differences in gS activity when varying, for example, cis/trans unsaturations of lipids.133 Thinner bilayers reduce the distances between the PS1 catalytic ASP residues in the active site.

Variations in lipid headgroups can impact the mobility of the enzyme. In particular, a reduced flexibility is observed in transmembrane helix 2 related to substrate entry. Inactivation of gS resulting from the presence of charged lipids has been observed. This may be due to high PS1 structural restriction caused by bilayer rigidity that disturbs substrate recruitment and entry into the gS active site, as proposed by Holmes et al. Alternatively, it has been proposed that charged lipids interacting with the catalytic aspartates may lead to inactivation of the enzyme.134,135

Since C99 cleavage by gS most commonly occurs when the enzyme and its substrates are colocalized in cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains, Aguayo et al. studied the structural properties of gS in the presence of cholesterol rich bilayers and a mixture of lipids mimicking a lipid raft.133 They found that higher cholesterol concentrations lead to increased lateral pressures favoring active enzyme conformations. Interestingly, gS in the presence of lipid mixtures does not show high lateral pressures but does favor dynamic structural transitions between active and inactive states of the GS complex. These dynamics were also observed in more compact NCT conformations. In that case, lipid headgroups interact with and retain the NCT extracellular domain,133 which is folded over the gS active site. This allows for the steric sorting of gS substrates, similar to what has been observed in other studies. Of note, the omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids are two components of brain cell membranes, with omega-3 slowing the progression of AD and omega-6 increasing the AD risk,137,138 but their impact on Aβ biogenesis and the conformational ensemble remains poorly understood.

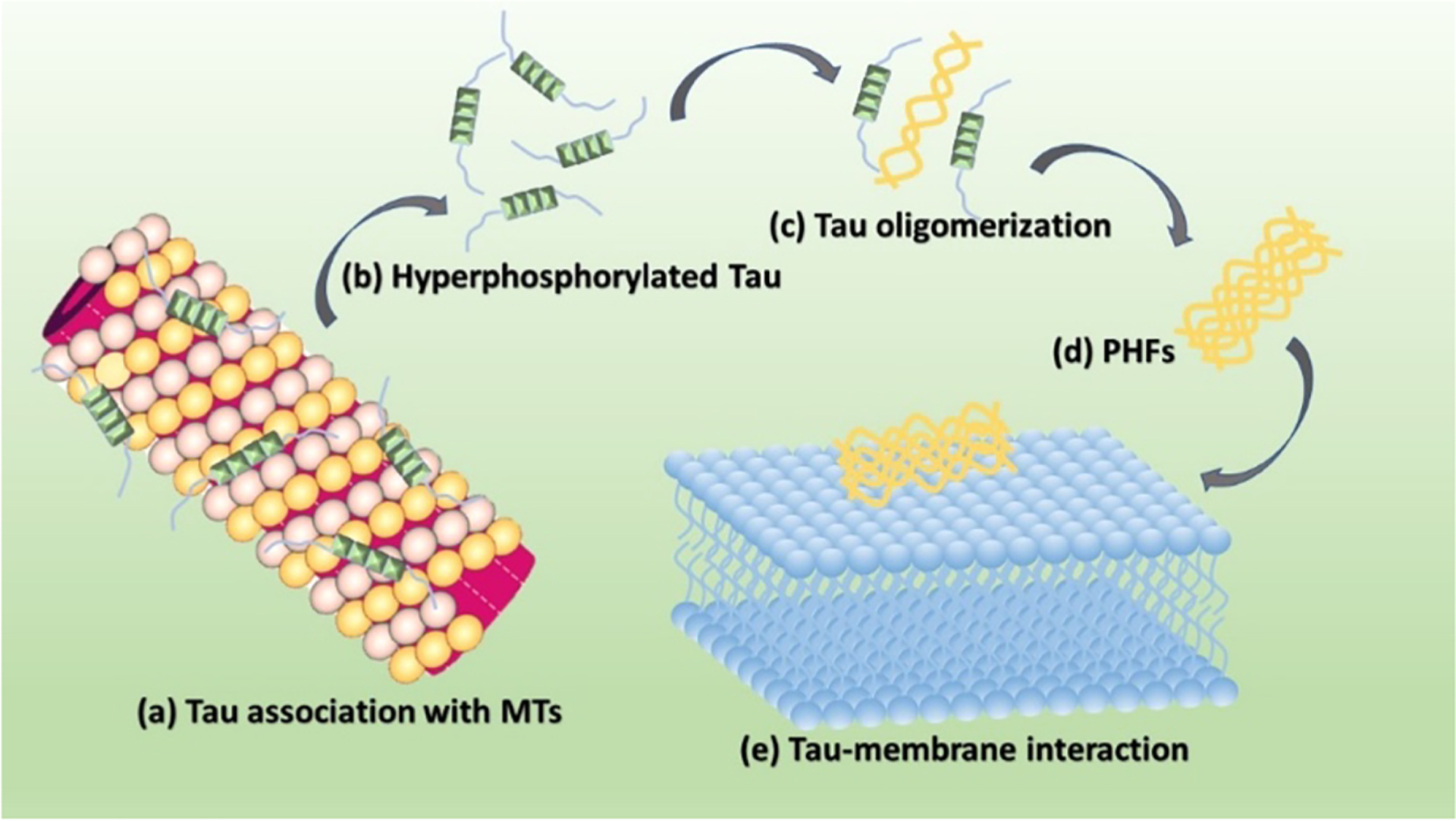

2.2. Domain Organization, Isoforms of Tau, and Minimal Sequence for Tau Aggregation and Toxicity

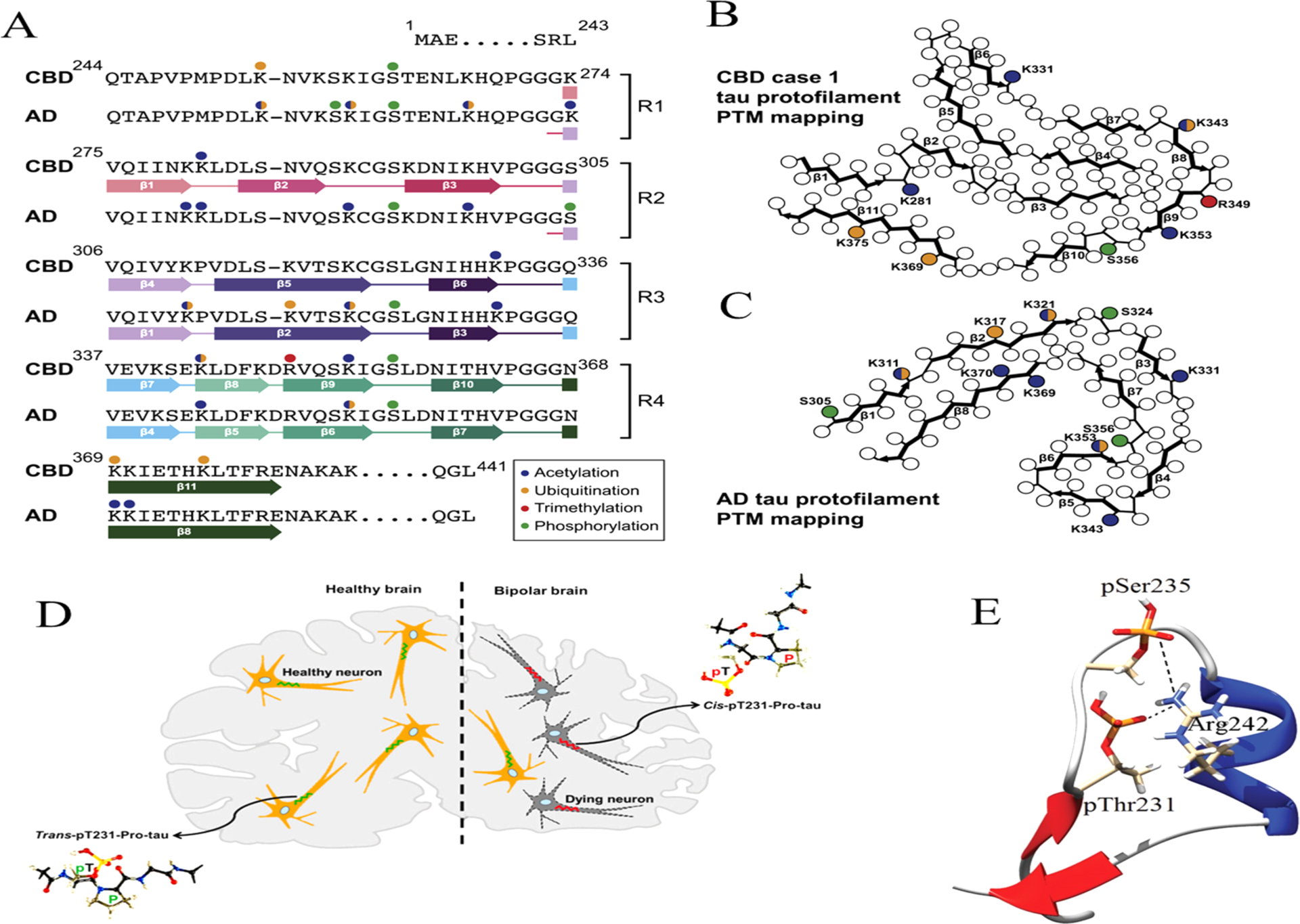

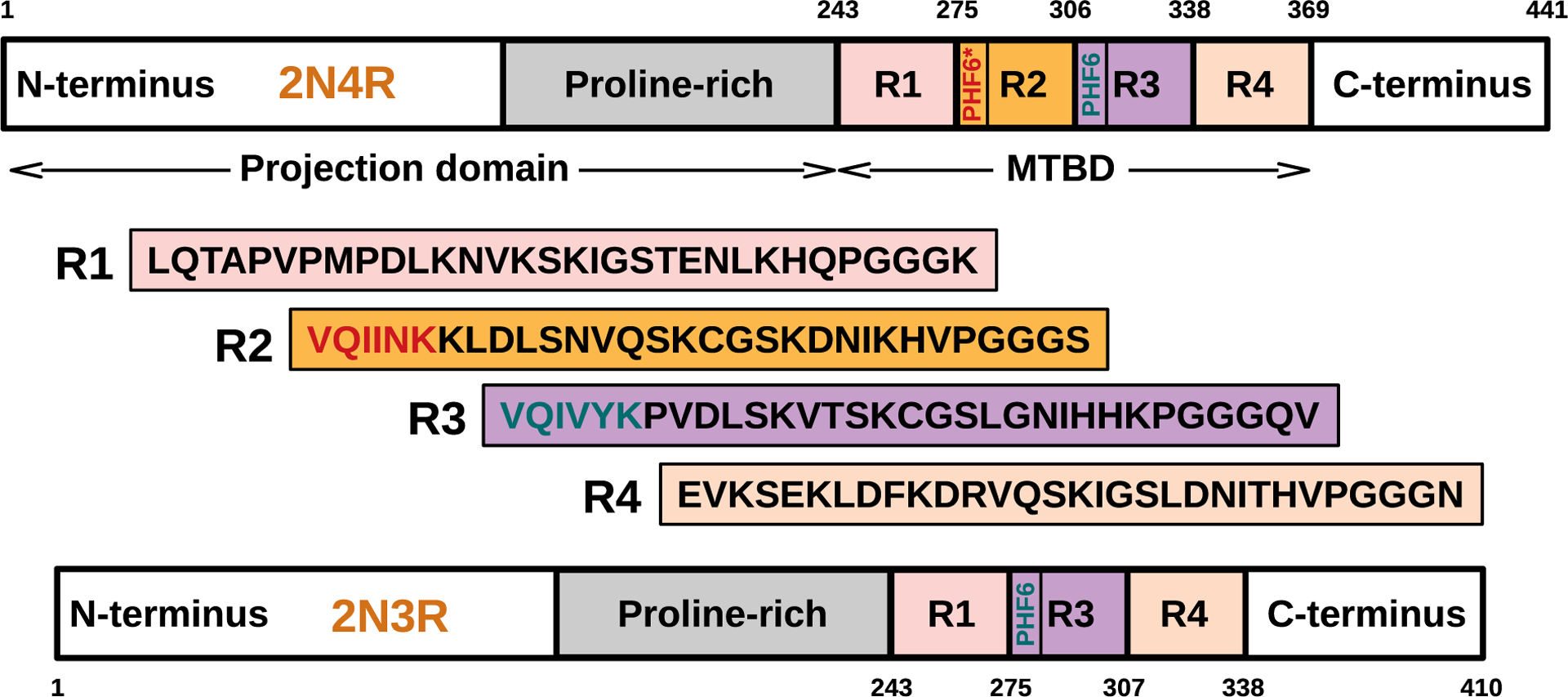

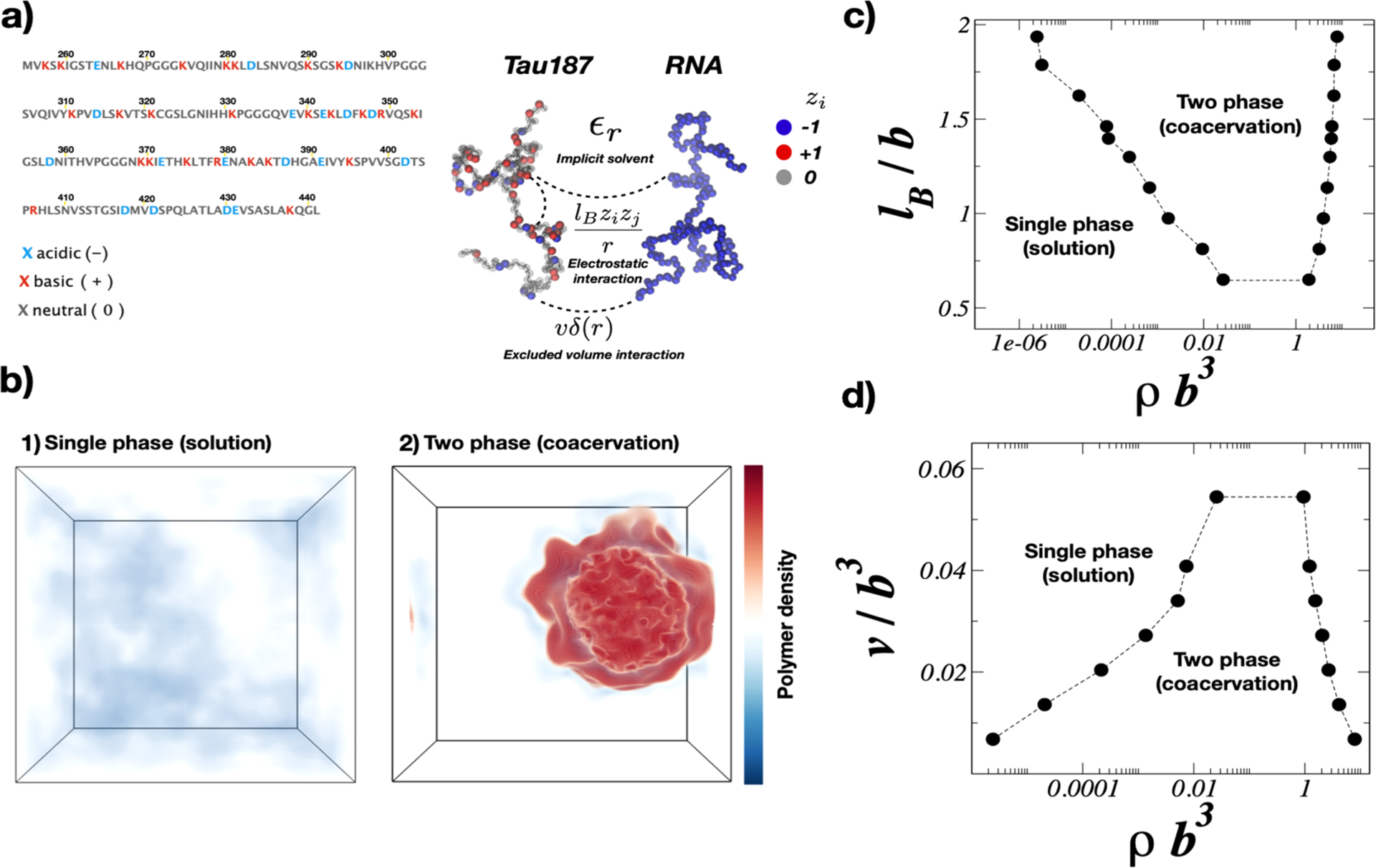

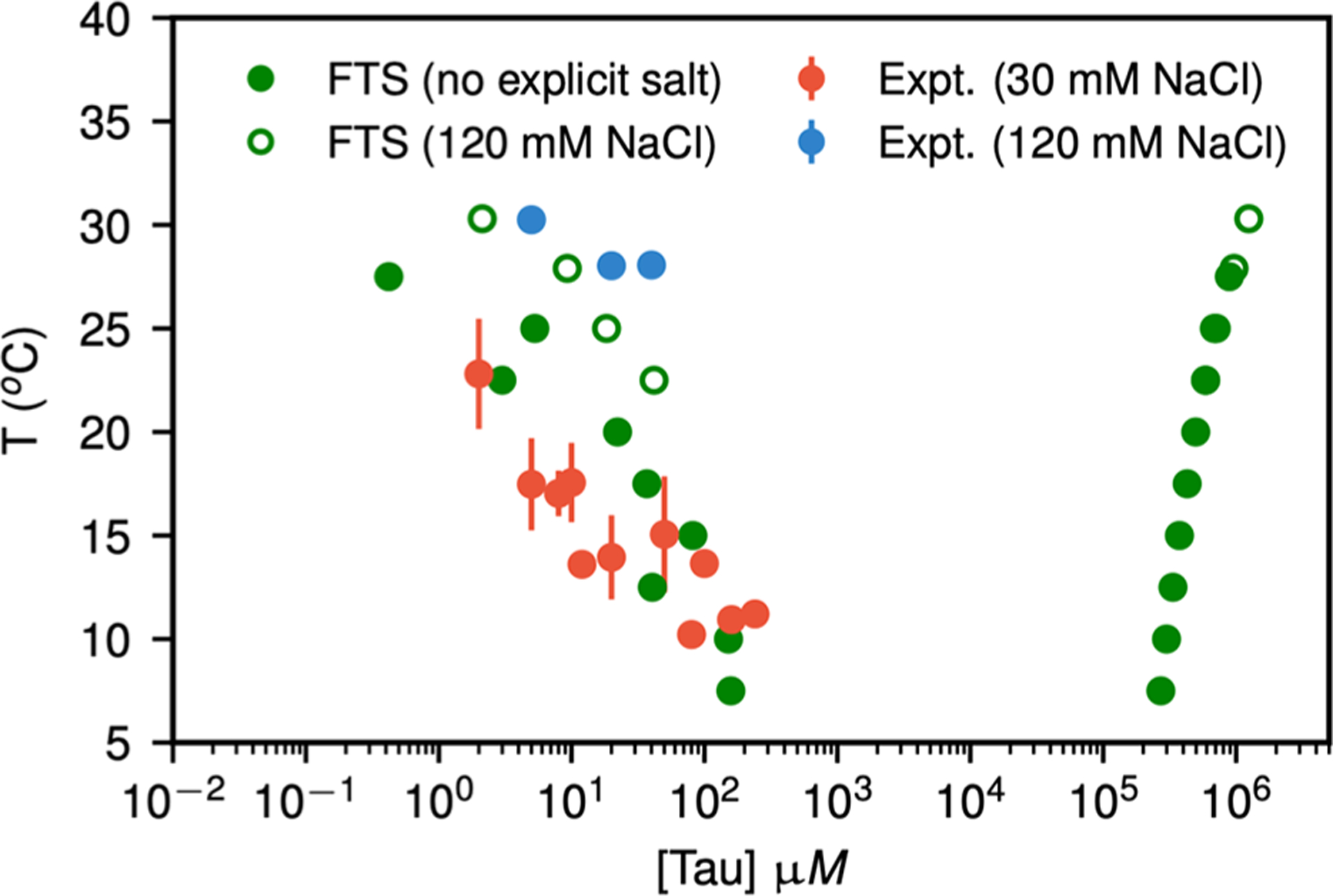

The tau protein forms paired helical filaments (PHFs) in neurofibrillary tangles central to the development of AD and other tauopathies. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that plays an important role in axonal stabilization, neuronal development, and neuronal polarity. Full-length tau (htau40) includes a projection domain, a microtubule-binding domain (MBD) of four imperfect sequence repeats (R1 to R4), and a C-terminal domain (Figure 3A). The projection domain protrudes from the microtubule surface and it contains an N-terminal region (with two N-terminal inserts 2N) and a proline-rich region. The MBD has high affinity for microtubules. All 4 repeats end with a PGGG sequence, and there are two hexapeptide regions (PHF6*: 275VQIINK280 and PHF6: 306VQIVYK311) located in repeats 2 (R2) and 3 (R3). The MBD and the proline-rich regions are both positively charged. The N-terminal part and a short region at the C-terminus are acidic. Alternative splicing leads to the generation of six major isoforms of tau in the human brain: htau40-(2N4R), htau32(1N4R), htau24(0N4R), htau39(2N3R), htau37(1N3R), and htau23(0N3R), ranging from 352 to 441 amino acid residues in length (Figure 3B). The MBD itself reproduces much of the aggregation behavior of tau in cells and animal models. Therefore, the peptides only encompassing the repeat region including K18 (4R) and K19 (3R) were often used to study tau aggregation to provide important insights into the amyloidogenesis of tau. The K18 and K19 are prone to aggregation since they do not contain the flanking regions that inhibit amyloidogenesis and they correspond to an amyloid core of PHFs.141

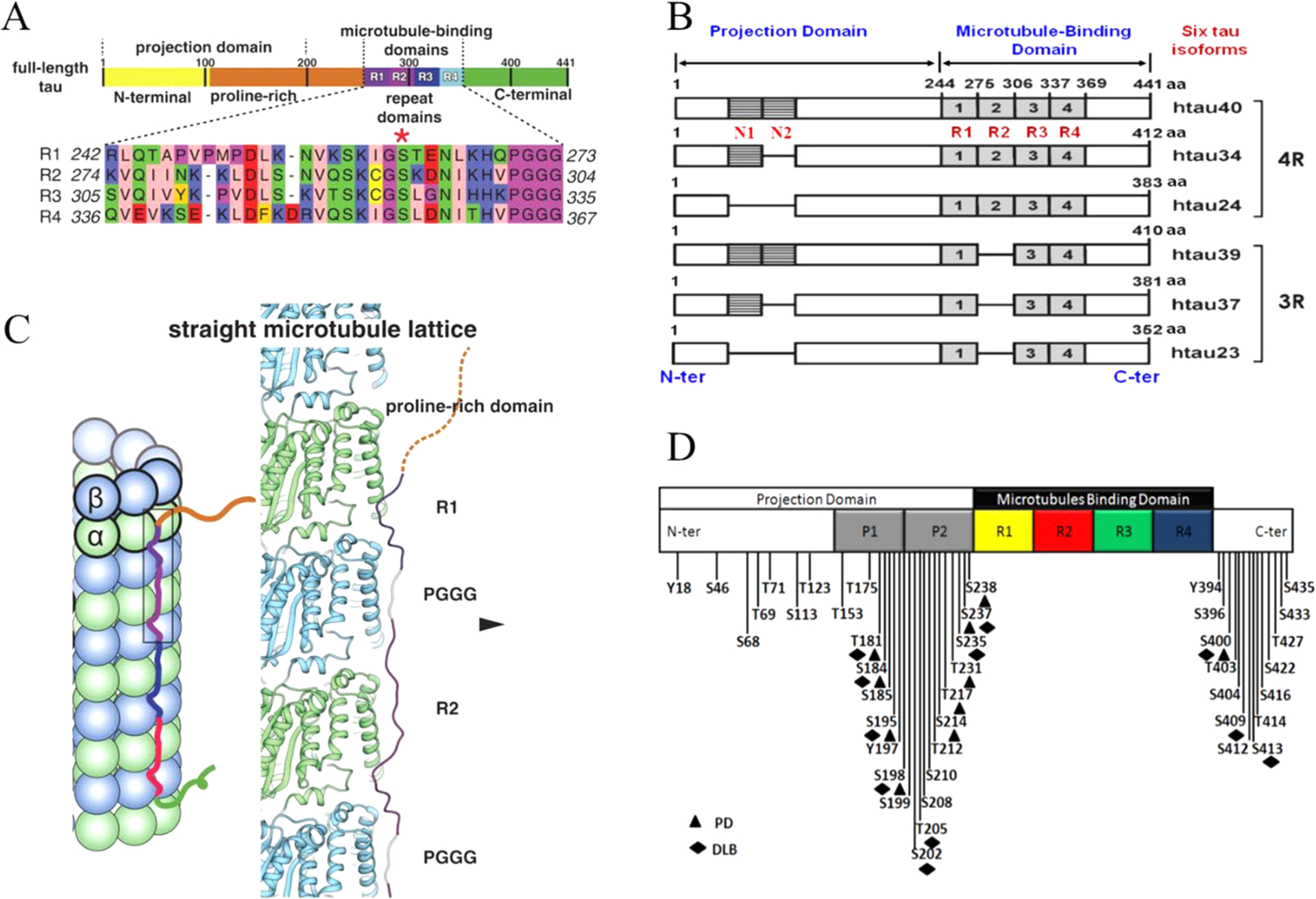

Figure 3.

Domain organization, isoforms of tau, and binding to microtubules. (A) Schematic of tau domain architecture and assigned functions. The MT-binding domain of four repeats is defined as residues 242 to 367. The inset shows the sequence alignment of the four repeat sequences, R1 to R4, that make up the repeat domain. Ser262 is marked by the asterisk.142 (B) Schematic representation of the six human tau isoforms and two tau constructs. Tau isoforms differ by the absence or presence of one or two 29-amino acid inserts in the amino-terminal part, in combination with either three (R1, R3, and R4) or four (R1–R4) repeat regions (black boxes) in the carboxy-terminal part. Isoform sizes range from 352 amino acids (aa) to 441 aa. (C) Model of full-length tau binding to microtubules and tubulin oligomers.142 (D) Schematic representation of the largest isoform of tau with specific phosphorylation sites. Serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues that can be phosphorylated in AD, PD, and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are indicated.

A recent cryo-EM study revealed different tau constructs on microtubules, and complemental atomic models of tau–tubulin interactions were generated by Rosetta modeling (Figure 3C).142 The conserved tubulin-binding repeats within tau adopt similar extended structures along the crest of the protofilament, spanning both intra- and interdimer interfaces, centered on α-tubulin and connecting three tubulin monomers. The cryo-EM structures suggest that all four tau repeats are likely to associate with the MT surface in tandem, through adjacent tubulin subunits along a PF. This modular structure explains how alternatively spliced variants can have essentially identical interactions with tubulin but different affinities according to the number of repeats present.142

Besides the six tau isomers, other tau fragments were also studied for their roles in tau aggregation. There is considerable interest in discovering the minimal sequence and active conformational nucleus that defines tau aggregation events. Truncation of tau may play a causative role in tauopathies. The long-running research of truncated tau has led to the generation of the first active tau vaccine that has entered clinical trials.143 Studies have shown that proteolytic fragments of tau can drive neurodegeneration in a fragment-dependent manner. Proteolytic fragments of tau have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with different tauopathies, providing an opportunity to develop these fragments as novel disease progression biomarkers.144 For example, tau (297–391) forms filaments that structurally mimic the core of paired helical filaments in AD brain.145 A fragment from the proteolytically stable core of the PHF, tau 297–391 known as “dGAE”, spontaneously forms cross-β-containing PHFs and straight filaments under physiological conditions. The comparison of the structures of the filaments formed by dGAE in vitro with those deposited in the brains of individuals diagnosed with AD found that they share a similar macromolecular structure.145 Cleavage of tau by legumain (LGMN) has been proposed to be crucial for aggregation of tau into fibrils.136 Using an in vitro enzymatic assay and nontargeted mass spectrometry, four putative LGMN cleavage sites were identified at tau residues N167-, N255-, N296-, and N368. Cleavage at N368 generates variously sized N368-tau fragments that are aggregation prone in the Thioflavin T assay in vitro. Both N368-cleaved tau and uncleaved tau were significantly increased in AD because of the accumulation of pathological tau inclusions. However, most of N368-cleaved tau remains largely soluble and is present only in low proportion in tau insoluble aggregates compared to uncleaved tau. This suggests that LGMN-cleaved tau has a limited role in the progressive accumulation of tau inclusions in AD.146

It is well-known that two hexapeptide regions, PHF6* and PHF6, located in R2 and R3 are top amyloidogenic motifs. The AcPHF6 may promote Aβ fibrillogenesis.147 However, in the longer tau sequence, tau local structure shields the PHF6 motif.148 When Aβ acts as tau aggregation seeds, Aβ fibril can promote the exposure of these hexapeptide regions.149 However, the PHF6 peptide lacks the ability to seed aggregation of tau244–372 in cells.150 But as the hexapeptide is gradually extended to 31 residues, the peptides aggregate more slowly and gain potent activity to induce aggregation of tau244–372 in cells.150 Further characterizations narrow down the β-forming region to a 25-residue sequence, indicating that the nucleus for self-propagating aggregation of tau244–372 in cells is packaged in a remarkably small peptide. Disease-associated mutations, isomerization of a critical proline, or alternative splicing are all sufficient to destabilize this local structure and trigger spontaneous aggregation.148 Numerous MD simulations have been conducted to study the PHP6 conformation and aggregation. In a recent MD and Markov state model (MSM) study,151 PHF6 can spontaneously aggregate to form multimers enriched with β-sheet structure, and the β-sheets in multimers prefer to exist in a parallel way. The residues Ile308, Val309, and Tyr310 play an essential role in the dimerization. MSM analysis shows that the formation of dimer mainly occurs in three steps. The separated monomers collide with each other at random orientations, and then a dimer with short β-sheet structure at the N-terminal forms; finally, β-sheets elongate to form an extended parallel β-sheet.151

Many studies have targeted these hexapeptide regions to prevent tau aggregation and toxicity. Using the model peptide, Ac-PHF6-NH2, the substitution of its amino acids with proline is shown to reduce self-assembly. Two of these modified inhibitors also disassemble preformed Ac-PHF6-NH2 fibrils, and one inhibits induced cytotoxicity of the fibrils.152 Inhibitors based on the peptide SVQIVY, shifted by −1 residue compared with PHF6 (VQIVYK), can also block proteopathic seeding by patient-derived fibrils.153 It was suggested that inhibitors based on the structure of the PHF6 segment only partially inhibit full-length tau aggregation and are ineffective at inhibiting seeding by full-length fibrils and that the PHF6* segment is the more powerful driver of tau aggregation.154 The PHF6* based-inhibitors not only inhibit tau aggregation but also inhibit the ability of exogenous full-length tau fibrils to seed intracellular tau in HEK293 biosensor cells into amyloid.154

Tau constructs can self-aggregate to PHFs directly; however, hyperphosphorylated tau appears to aggregate more readily and may sequester normal tau at lower concentrations.155,156 The regulation of tau primarily involves post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, truncation, and acetylation. The most common tau PTM is phosphorylation. In the AD brain, tau is excessively phosphorylated, at least ~3-fold over normal brain, leading to the disruption of the MTs and the promotion of filament formation.157 Other PTMs can also regulate tau aggregation; for example, tau truncation may take place after tau hyperphosphorylation with subsequent glycation.158 Methylation has been shown to suppress tau aggregation propensity whereas glycation and acetylation promote pathological tau aggregation.159,160 The distribution of phosphorylation sites along the sequence of full-length tau is uneven. Htau40 has 80 serine/threonine and 5 tyrosine residues that can be phosphorylated. Most of them are in either the N- or C-terminal regions. Mass spectrometry identified around 36 sites in purified PHF-tau from human Alzheimer brain.161 Figure 3D illustrates the known phosphorylation sites in tau.

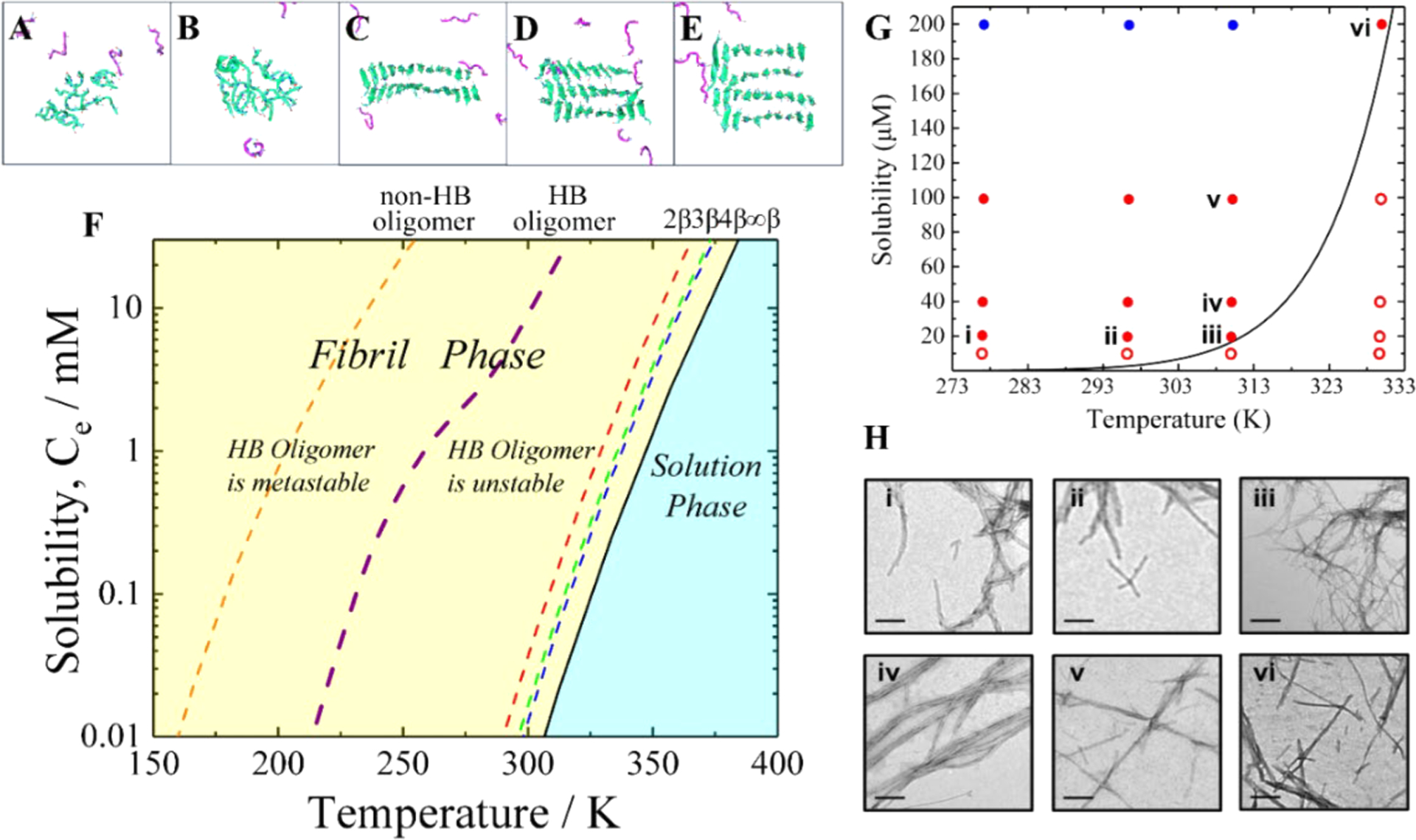

Cryo-EM structures of tau fibers in four distinct diseases, AD,140 Pick’s disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) have different conformations.41,162–164 These structures are discussed in section 3. The tau protein and its fragments have an intrinsic ability to assemble into amyloid structures of large dimensions in the absence of aggregation-enhancing species, such as heparin or alternative polyanions. Luo et al. have shown that heating K18 to a high temperature leads to tau aggregation, but it disassociates to monomeric state reversibly when cooling down.165 Their replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations predicted that tau proteins could form amyloid fibrils at a high temperature of 343 K, and the tau amyloid fibrils may cold dissociate at 275 K. This intriguing feature was then confirmed by fluorescence experiments, and it was observed that K18 fibrils cold dissociate when cooled. They also found that heparin locks the tau fibril and prevents its reversion. Adamcik et al. demonstrated that in the absence of heparin, the tau306–327 R3 fragment is able to self-assemble into large, flat, multistranded ribbons consisting of up to 45 laterally assembled protofilaments.166

Besides heparin, other polyanions have also been employed to study the structural consequences; aggregation through interaction with a physiologically relevant aggregation inducer is important. The formation of AD filaments is routinely modeled in vitro by mixing tau with heparin. Heparin promotes tau aggregation and recently has been shown to be involved in the cellular uptake of tau aggregates.167 Polyphosphate initiates tau aggregation through intra- and intermolecular scaffolding, most notably breaking long-range interactions between the termini.168 Different from heparin, polyglutamic acid does not immediately convert tau into oligomers.169 Tau is predominantly monomeric in the presence of polyglutamic acid at low temperature and only aggregates into oligomers and fibrils at higher temperature and longer incubation time. Utilizing this feature, through a combined NMR spectroscopy and molecular ensemble calculation method, Akoury et al. examined the conformational ensembles of K18 in the presence and absence of the polyglutamic acid and found that binding of polyglutamic acid to tau remodels the conformational ensemble of tau.170

Using a heparin-immobilized chip, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) revealed that tau K18 and K19 bind heparin with a Kd of 0.2 and 70 μM, respectively. In SPR competition experiments, N-desulfation and 2-O-desulfation had no effect on heparin binding to K18, whereas 6-O-desulfation severely reduced binding, suggesting a critical role for 6-O-sulfation in the tau-heparin interaction. The tau-heparin interaction became stronger with longer-chain heparin oligosaccharides. As expected for an electrostatics-driven interaction, a moderate amount of salt (0.3 M NaCl) abolished binding.171 However, it was found that heparin-induced tau filaments are structurally heterogeneous and differ from AD filaments,172 as discussed in section 3.

The heparin induced tau structures illustrate the structural versatility of amyloid filaments and raise questions about the relevance of in vitro assembly.173 Our understanding of this question is that polyanion induced tau structure and those found in patients’ brain so far present favorable states in the complex amyloid formation energy landscape. As the structure of Aβ fibril, the tau fibril may exist in different forms from different patients. This can be supported by the study of PHP6 based inhibitors. Donors with progressive supranuclear palsy exhibited more variation in inhibitor sensitivity, suggesting that fibrils from these donors were more polymorphic and potentially vary within individual donor brains.153 Exploring the interplay between fibrillization and amorphous aggregation channels on the energy landscapes of 3R and 4R tau provided a global view of polymorphic tau aggregates.174 A coarse-grained protein force field was used to study the energy landscapes of nucleation of the 3R and 4R fibrils derived from patients with Pick’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. The landscapes for nucleating both fibril types contain amorphous oligomers leading to branched structures as well as prefibrillar oligomers. These two classes of oligomers differ in their structural details: The prefibrillar oligomers have more parallel in-register β-strands, which ultimately lead to amyloid fibrils, while the amorphous oligomers are characterized by a near random β-strand stacking, leading to a distinct amorphous phase.174 The feature of the energy landscape connecting the tau oligomers and fibrils was reflected in the sm-FRET studies of oligomer diversity during aggregation of K18, although also in the presence of heparin.175 Kjaergaard et al. observed that the shortest growing filaments only represent a small population of transient oligomers with cross-β structure, while the two largest oligomer populations are structurally distinct from fibrils and are both kinetically and thermodynamically unstable. The first electrostatic driven population is in rapid exchange with monomers; the second kinetically more stable one is probably off-pathway to fibril formation.175

In vitro, 0N4R tau fibrils contain a monomorphic β-sheet core enclosed by dynamically heterogeneous fuzzy coat segments.176 A variety of experiments indicate that 0N4R tau fibrils exhibit heterogeneous dynamics. Outside the rigid R2-R3 core, the R1 and R4 repeats are semirigid even though they exhibit β-strand character and the proline-rich domains undergo large-amplitude anisotropic motions, whereas the two termini are nearly isotropically flexible. It has been suggested that the N- and C-termini differentially associate with PHFs177 and play distinct roles in the stability and consequently neurotoxicity of tau filaments.178 The N-terminal fragment (residues 1–15) did not affect tau polymerization179 whereas a fragment consisting of residues 1–196 could inhibit polymerization of full-length tau.180 The tau C-terminus is crucial in the formation of tau PHFs,181 and it also modulates the cross-seeding barrier between 4R and 3R tau.182 Xu et al. performed multiscale MD simulations to study the structure and dynamics of full-length tau filaments, especially the effects of the flanking regions on the stability of the filament core.183 They found that full-length tau filaments consist of one dense core and two sparse layers, consistent with the structural model derived from the experimental observations. The relative stability of the filaments not only depends on the core morphology but can also shift by interactions among different domains.

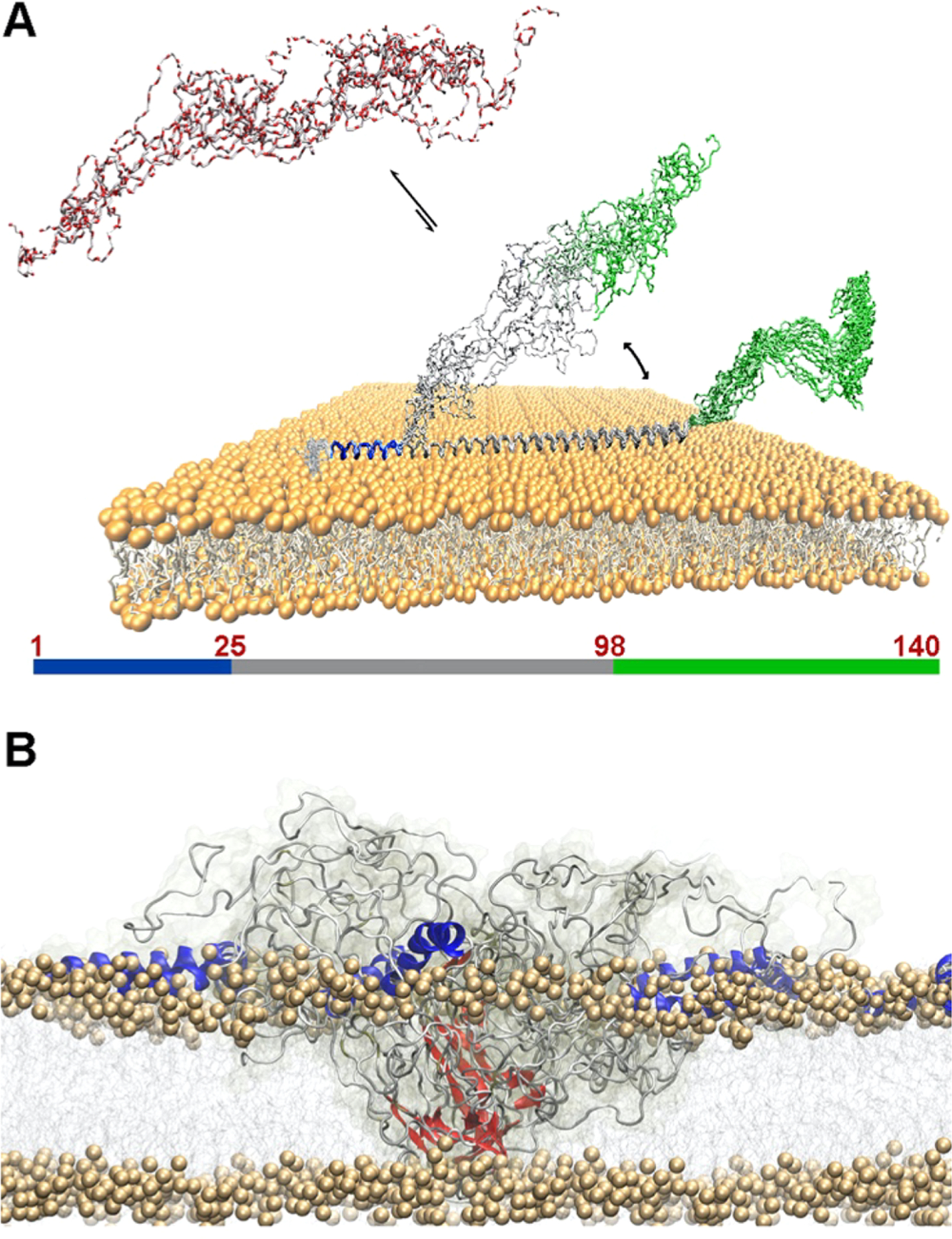

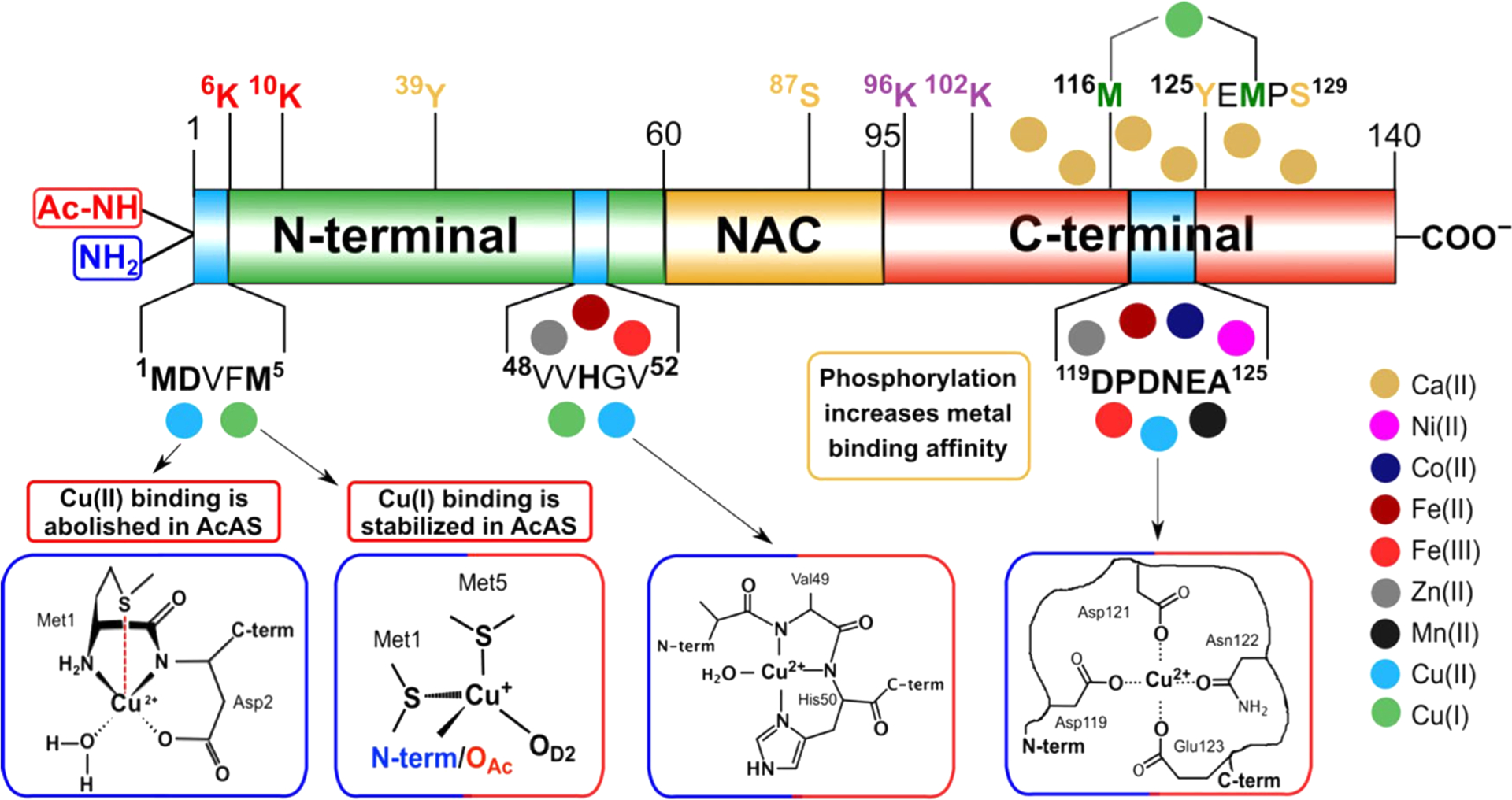

2.3. α-Synuclein and IAPP Domains and Aggregation Properties

αS is a 14 kDa neuronal protein that is predominantly localized at the presynaptic termini.184 In its physiological form, αS is monomeric and disordered,185 although some studies have generated a debate186 on whether it adopts a helical tetramer in vivo.187 The aggregation of αS is inherently connected with PD, as its aggregates are major components of intracellular inclusions known as Lewy bodies forming in dopaminergic neurons of PD patients.188 There are also links between the αS-encoding gene and familial forms of PD, with mutations, duplications, and triplications being found in patients affected by early onset forms of PD.189 Fibrillar aggregates of the relevant aggregation-prone region of αS, the nonamyloid-β component (NAC), are also found in AD patients190 and in the context of other neurodegenerative disorders, including dementia with Lewy bodies,191 multiple system atrophy,192 and other synucleinopathies.193

While the pathological relevance of αS is generally acknowledged, its function remains unclear.194 The abundance of αS at the synaptic termini has suggested that it may be involved in neuronal processes and studies have indicated possible roles in synaptic plasticity195 and learning.196 A number of pieces of evidence have been collected on a possible function of αS in the trafficking of synaptic vesicles (SVs) during neurotransmitter release.197,198 αS binds SVs in vitro and colocalizes with SVs in synaptosomes in a calcium responsive manner.199 Key evidence indicates that αS has a role of chaperone for the assembly of the SNARE complex;200 the machinery promoting the fusion of SVs with the plasma membrane. αS was indeed shown to rescue the formation of the SNARE complex in knockout mice lacking CSPα,201 whereas knockout mice lacking the three synucleins (α-, β-, and γ-) showed neuropathological phenotypes that are indicative of impaired SNARE activity.202 The interaction with SVs by αS has also been implicated in the promotion of SV-clustering,203,204 a key process in the maintenance of pools regulating SV homeostasis during neurotransmitter release.198 In addition to its interaction with SVs, αS has also been implicated in the regulation of the vesicle trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi205 and the mitigation of oxidative stress in mitochondria.206

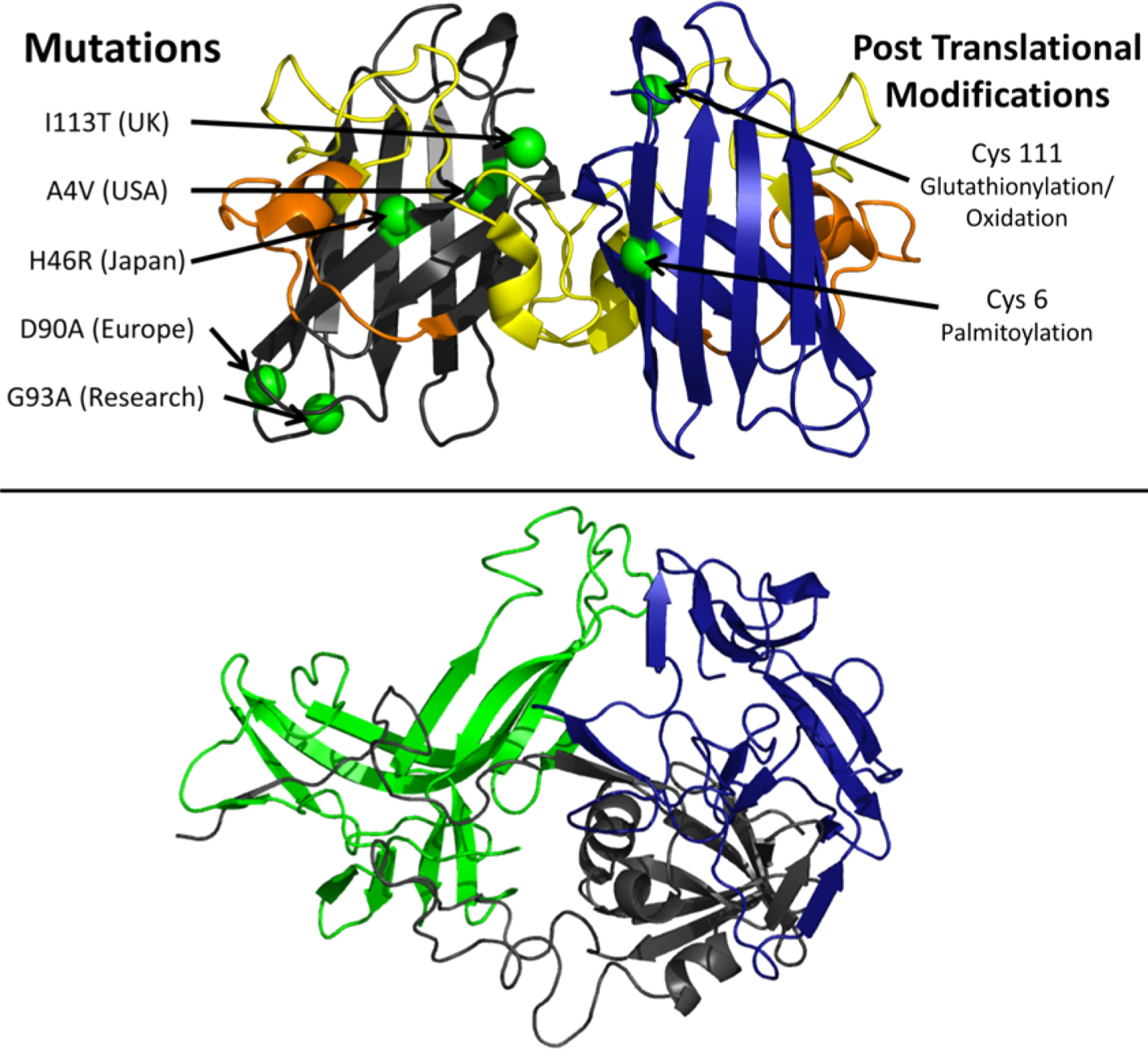

The domain organization of αS is defined on the basis of its sequence properties and in relation to the biological context (Figure 4). The major biological form of αS in vivo features the binding with cellular membranes.207 Membrane interactions by αS are promoted by a lipophilic domain (residues 1 to 90) and featuring 7 imperfect sequence repeats. These 11 residue repeats induce binding via a disorder-to-order transition into amphipathic class A2 α-helical segments that promote the membrane binding.208 This domain also has genetic links with inherited forms of early onset PD, as it hosts all the PD-related αS mutations (A30P, E46K, H50Q, G51D, and A53T).189

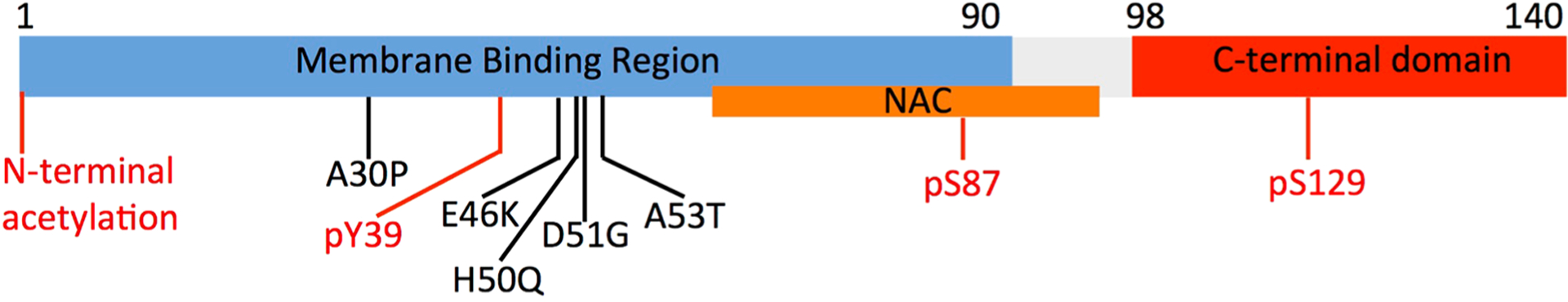

Figure 4.

Key αS domains having a role in functional and pathological contexts. The membrane-binding domain (residues 1 to 90), the NAC region (residues 61 to 95), and the C-terminal domain (residues 98 to 140) are shown in blue, orange, and red, respectively. The diagram also shows the main pathological mutations (black) and key post-translational modifications (red) such as the N-terminal acetylation and phosphorylation of residues Ser87, Ser129, and Tyr39.

Another domain of αS, the NAC (residues 61–95), has relevance in the context of self-assembly and aggregation. NAC is essential for the kinetics of αS aggregation209 and is the main component of the core of αS fibrils. Fibrils of the NAC region have been isolated in the context of PD as well as in other neurodegenerative diseases.190 Finally, the negatively charged C-terminal domain of αS spanning residues 99 to 140 (net charge of −9) is implicated in calcium binding199 and in protein–protein interactions at the surface of synaptic vesicles.197,200

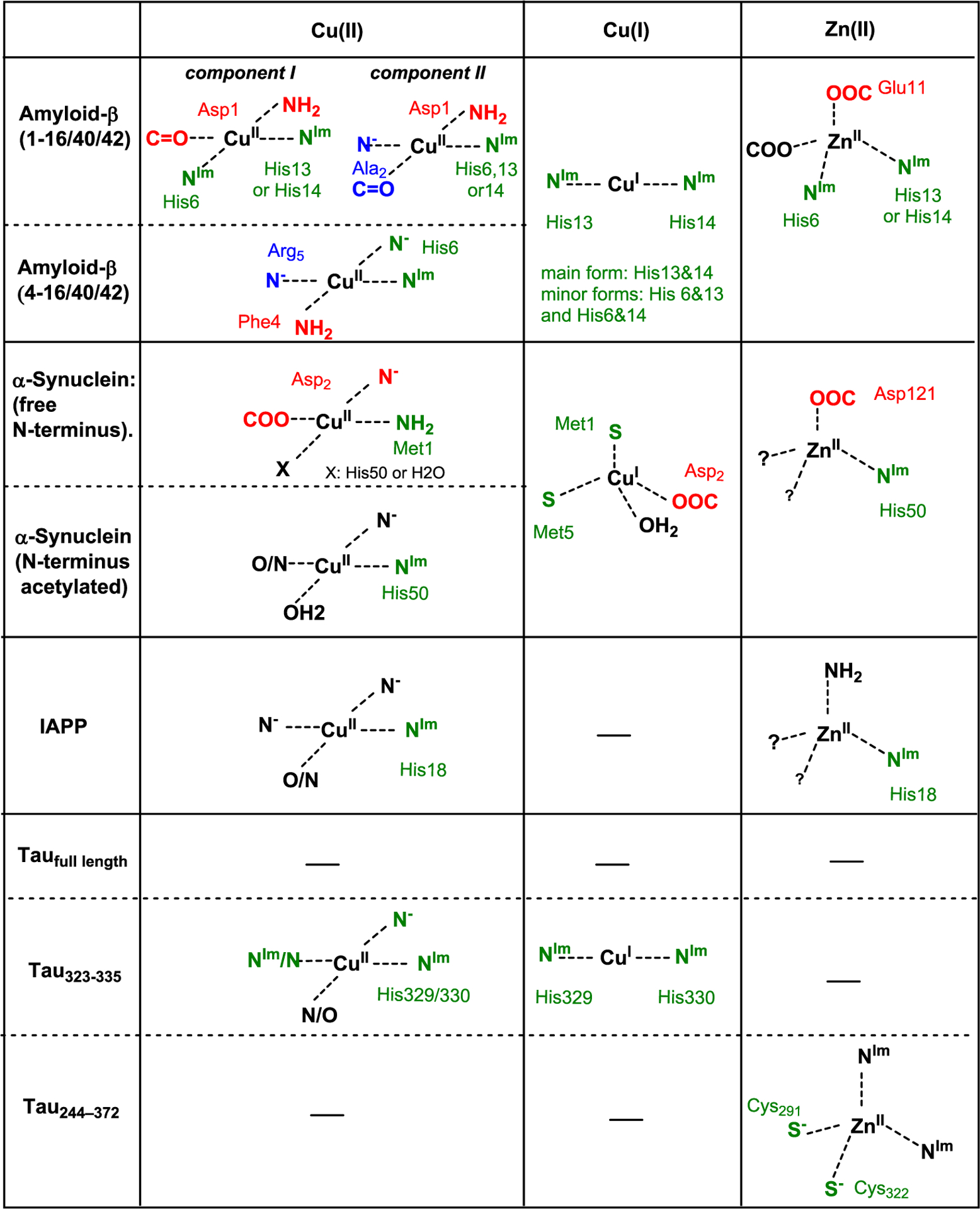

IAPP or amylin is a 37-residue hormone produced by pancreatic β-cells to regulate the response to high glucose levels in the blood in conjunction with insulin, which is cosecreted.210 The biogenesis of amylin requires the production of the proIAPP, a peptide composed of 67 residues whose cleavage generates IAPP.211 In addition to his role as a hormone, IAPP is well-known for its connection with T2D. Indeed, fibrillar aggregates of IAPP are the major constituents of deposits in pancreatic islets that are found in the majority of patients suffering from this condition. Despite the fact that the toxicity of IAPP amyloids has been shown in vitro,212,213 it remains to be established whether its aggregation is a causative factor or a downstream effect of TD2. Indeed, in contrast to Aβ protein where many familial mutations exist, there is only one unique disease-causing mutation in IAPP (S20G), and in the majority of the cases, no specific alterations or mutations of IAPP are found in diabetic individuals, suggesting that other factors, such as the failure of control mechanisms to prevent protein misfolding, may be involved. Islet amyloids are de facto found also in small populations of nondiabetic elderly individuals,214 likely owing to a reduced efficiency in the mechanisms of clearance of protein aggregation. In vitro IAPP has been shown to aggregate in a concentration dependent manner, and it rapidly self-assembles into amyloids when concentrated in the millimolar range, a condition that by contrast is well managed in the secretory granules of β-cells of healthy individuals.

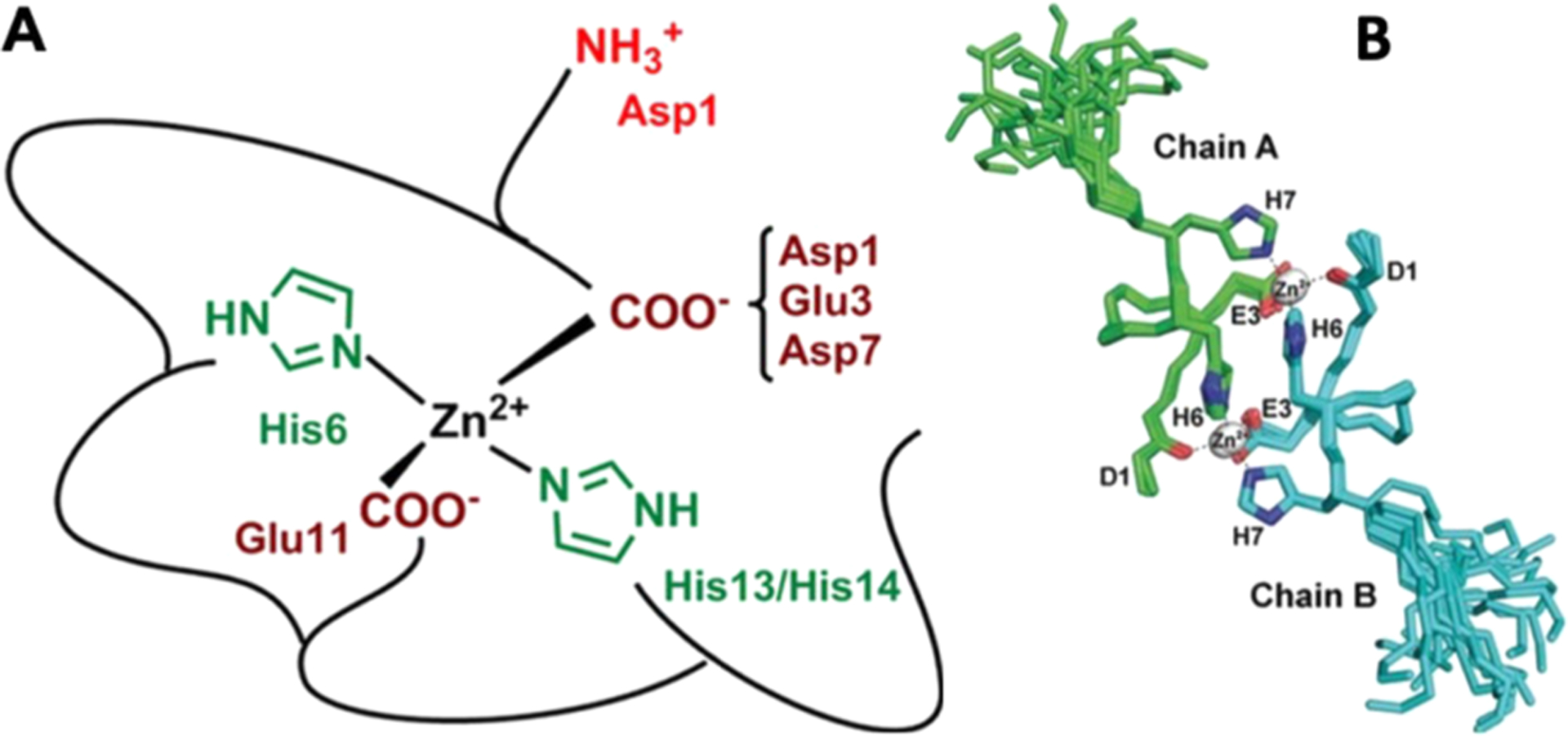

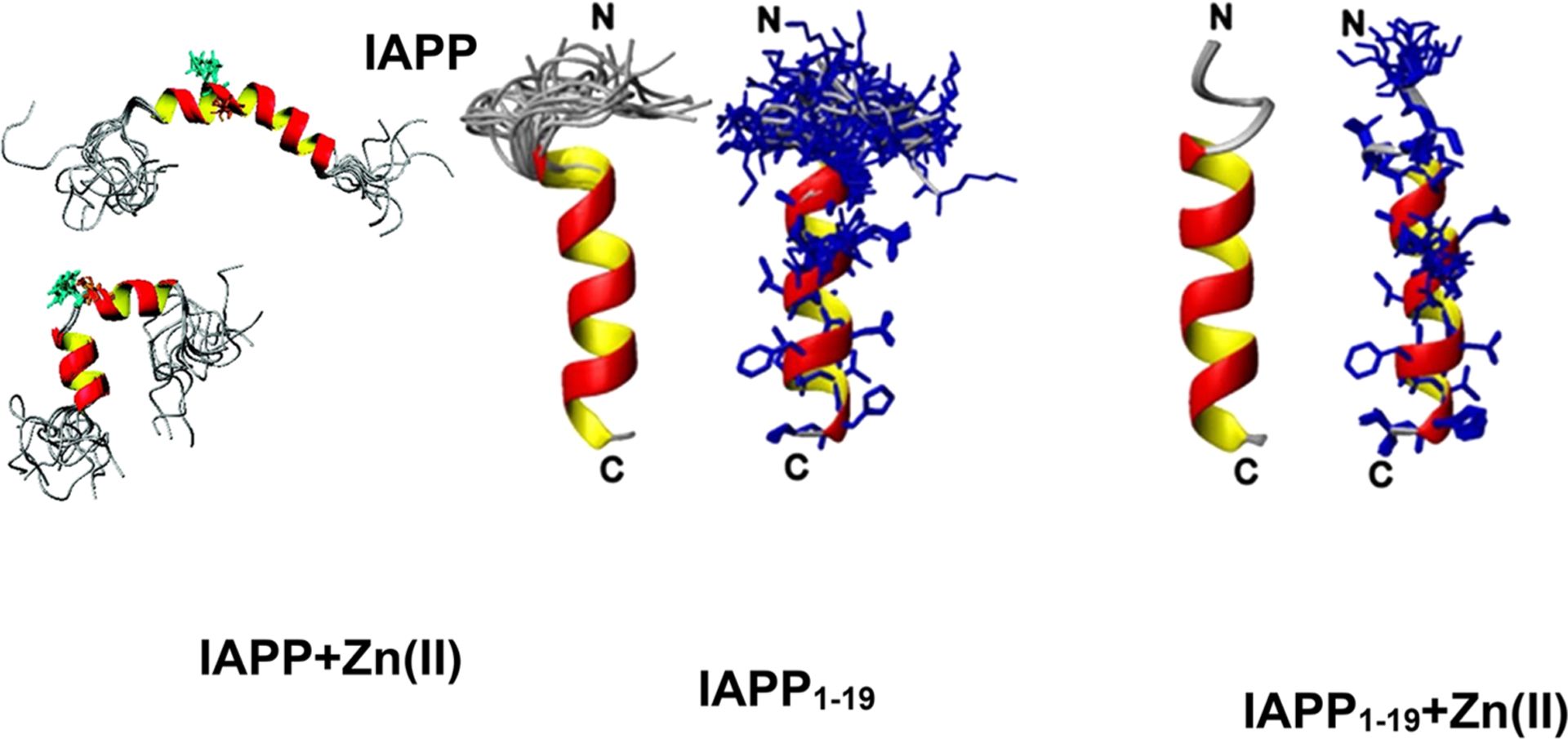

Among the factors that inhibit the aggregation of IAPP in β-cells are the acidic pH (~5.0), shown to be largely unfavorable to the misfolding of IAPP in vitro,215 and the presence of high levels of Zn(II) in β-cells. The binding to Zn(II) indeed promotes conformations of the otherwise intrinsically disordered IAPP that are aggregation resistant, presumably by shielding the two amyloidogenic sequences of IAPP. Indeed, two regions have been found to be crucial for the fibrillization of IAPP. These are included in the N- and C-strands forming the fibrillar core of IAPP amyloids and spanning respectively residues 8 to 17 and 28 to 37. The two strands form a single stack in the cross-β arrangement, generating two facing β-sheets stabilized by a steric-zipper dry interface.216

3. STRUCTURES OF Aβ, TAU, α-SYNUCLEIN, IAPP OLIGOMERS, AND FIBRILS FROM EXPERIMENTS

3.1. Experimental Techniques for Fibrils

Amyloids are proteineous deposits associated with peculiar physical and chemical features: (i) they exhibit a very low degree of solubility, (ii) they form nanoobjects of various ultrastructural shapes and multiple sizes ranging from a few nanometers to microns, and (ii) they can represent objects of heterogeneous morphologies at the macroscopic scale (e.g., aggregates, fibrils, or oligomers) and heterogeneous conformation or polymorphic nature at the atomic level.217 Additionally, amyloid deposits tend to be difficult to isolate, biochemically handle, and purify due to their insolubility. Their biochemical features constitute major hurdles for biophysical approaches and structural biology toward determining atomic resolution structural models. The development of innovative methods in structural biology during the past two decades has been very fruitful, and more than 100 structures of protein and peptide fibrils (~40 from full length constructs) have been deposited at the PDB218 using different techniques such as X-ray diffraction, NMR, and EM.210 3D model determination of amyloid architecture relies on a multistep process to elucidate structural features at various levels:

3.1.1. Length of the Amyloid Core.

The amino acid sequence of the amyloid core usually covers only a fraction of the full-length protein; for example, the amyloid core of α-synuclein does not comprise its C-terminal domain.219 A simple biochemical maneuver to delineate the length of the amyloid core is the enzymatic digestion of protein segments that are not involved in the core region. H/D exchange performed by mass spectrometry220 or solution NMR221 is an experimental approach that is commonly used to delineate the amyloid core at a residue-specific resolution.

3.1.2. Secondary Structure.

Amyloid deposits are rich in β-sheet secondary structure; this information can be rapidly extracted with CD and FTIR. A key step toward determining the amyloid structure is the identification of the number and delineations of the β-sheets as well as the localization of β-sheet breakers or turns. This can be achieved by high-resolution techniques, i.e. ssNMR and cryo-EM. Using solid-state, the secondary structure can be predicted from chemical shifts using computational routines such as TALOS222 or by the secondary chemical shifts.223 Because the chemical exchange of amide hydrogens with the buffer is remarkably slowed down if the involved residue is comprised in the amyloid core, H/D exchange techniques offer a powerful approach to distinguish amino-acids involved in the hydrophobic amyloid core and thus identify β-sheet positioning. Recent advances in cryo-EM methodology, including software developments and new electron detectors, have facilitated structure determination of amyloid fibrils, backbone conformation, and secondary structure elements.224 They can be recognized after single particle EM analysis, recently demonstrated for αS225 and Aβ.226

3.1.3. Three-Dimensional Fold and Intermolecular Packing.

Although most amyloids share the generic cross-β architecture, the number of β-sheet elements and their placement relative to each other can be very diverse. Several generic architectures have been proposed, such as the β-helix, β-sandwich, superpleated β-sheet structure, or β-roll. The supramolecular arrangement of amyloid fibrils is often regular in a protofilament and has been observed as β-sheets that run antiparallel or parallel in-register along the fibril axis. The β-solenoid fold was the first experimentally determined amyloid fold at high resolution, from the amyloid prion HET-s by ssNMR.39 This architecture is characterized by specific amino acid sequence patterns composed of hydrophobic residues pointing inside the core that sequentially alternate with polar residues pointing outside. Although originally associated with functional amyloids, this fold has been recently seen in tau fibrils by cryo-EM,40 suggesting this fold to be generic in the context of pathological and functional amyloids.

The cross-β nature of the sample is essentially characterized by X-ray diffraction,227 and additional information relative to high-order symmetry can be derived from scanning transmission EM228 and tilted-beam transmission EM.229 These two approaches provide the so-called mass-per-length measurement, a crucial structural parameter to determine how many protein monomers are stacked per fibril layer. 3D structure determination of amyloids using ssNMR relies on the collection of internuclear distance restraints, typically in the range of 2–8 Å.230 Distinction between intramolecular proximities (i.e., two nuclei in two β-sheets within the same molecule) and intermolecular proximities (i.e., two nuclei in two β-sheets in adjacent molecules) requires the use of strategic isotope labeling231 and is still a major bottleneck for ssNMR-based structure determination. In analogy to distance measurements by ssNMR, double electron–electron resonance spectroscopy (DEER) and continuous-wave electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) are powerful approaches to provide residue–residue structural restraints in a distance range not accessible to ssNMR > 10 Å.232

In the case of short amyloid-forming peptides that crystallize, conformational studies at atomic resolution can be performed by X-ray diffraction analysis42 and microelectron diffraction.233 Numerous fibril-forming peptides have been crystallized to uncover numerous intermolecular stacking arrangements. Notably, these studies have highlighted the role of steric zipper motifs that consist of complementary side chains interdigitation in a dry interface, resulting in stable packing of high density.

Cryo-EM has opened an avenue to obtain both intramolecular and intermolecular arrangement of amyloid fibrils at atomic resolution.224 A major advantage of cryo-EM is the ability to obtain high-resolution maps from patient-derived samples, reducing artifacts associated with in vitro aggregation of recombinant proteins. Amyloid fibrils are usually observed as bundles of individual filaments termed protofilaments. Ultrastructural analysis of such bundles has revealed the presence of particular high order architectures, such as twisted or straight morphologies. AFM and EM are used to decipher the morphology of amyloid fibrils, but their resolution is limited. Cryo-EM has recently proven to be a unique technique to characterize the quaternary arrangement of protofilaments, as exemplified by the determination of the staggering of nonplanar β-strands in the case of Aβ42226 and tau.40

3.2. Diversity of Fibril Structures in Tau, α-Synuclein, Aβ, and IAPP

3.2.1. Tau Filaments.

Tau filaments were first observed in paired helical PHF234 and then a mixing of PHF and straight filaments (SF) by EM.235 Structure determination of tau filaments has been limited for a long time by the important length of the amyloid core and the particular nature of the filament that is composed of a rigid core and a fuzzy coat lacking structural order. Moreover, in vitro aggregation of recombinant tau requires the use of cofactors such as heparin, and these cofactors might modulate the details and the obtained polymorphism236 of the cryo-EM structures of tau in AD and Pick’s disease.

In AD, both structures of PHF and SF (Figures 5A and B) are composed of eight β-sheets in a C-shaped fold, although lateral protofilament contacts revealed a different intermolecular organization between the protofilaments, suggesting an important role of ultrastructural polymorphism in the context on in vivo tau aggregation. Filament cores are made of two identical protofilaments comprising residues 306–378 of tau protein, which adopt a combined cross-β/β-helix structure and define the seed for tau aggregation. Paired helical and straight filaments differ in their interprotofilament packing, showing that they are ultrastructural polymorphs.40

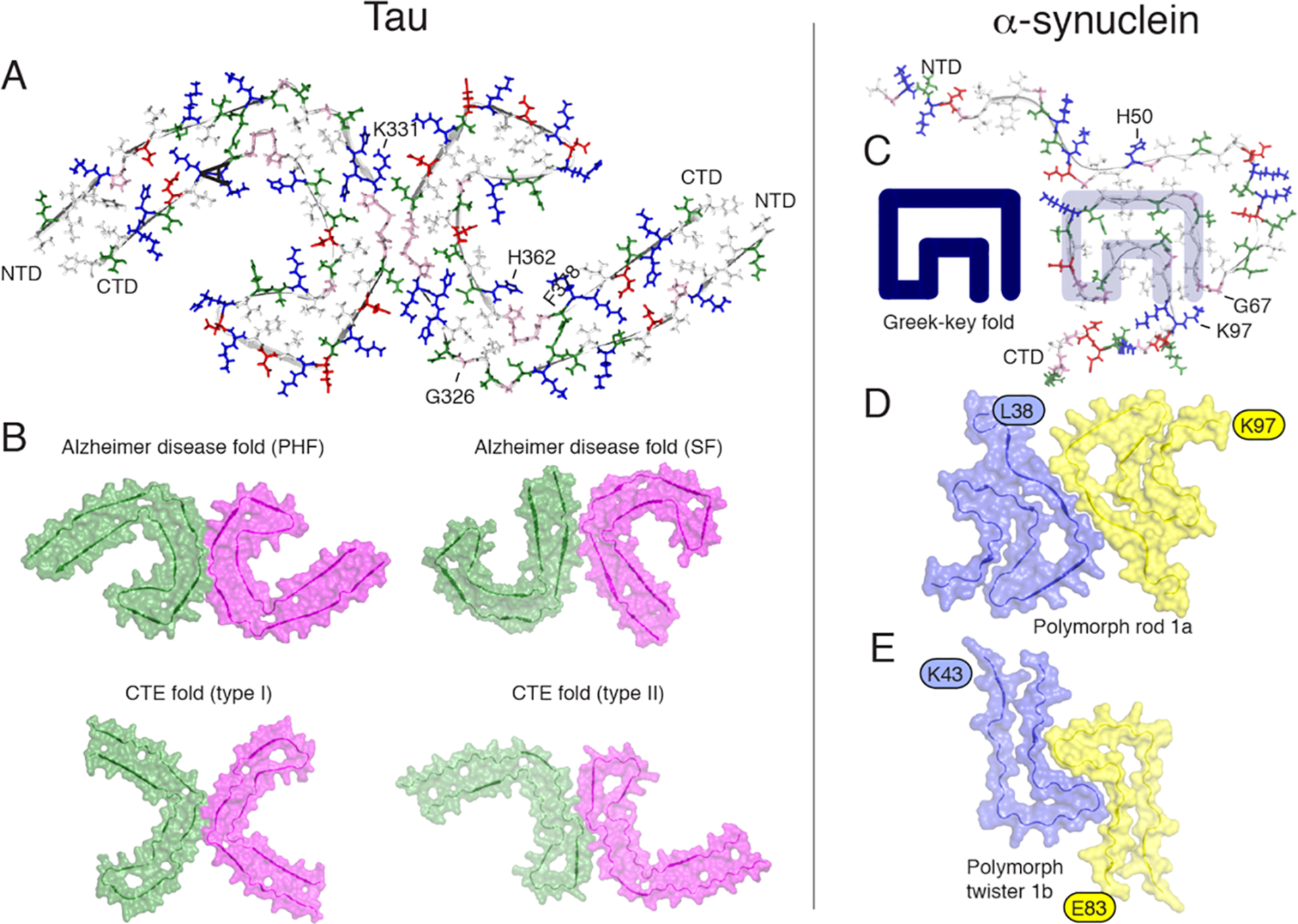

Figure 5.

Orthogonal view of the three-dimensional structural models of tau filaments and α-synuclein amyloid fibrils. NTD and CTD are the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. (A) Solid-state tau paired PHF spanning residues 306–378 in the right protofilament. (B) Cryo-EM PHF and SF tau amyloid cores in AD. In chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), tau filaments contain predominantly the type I (90%) and type II filaments. The interprotofilament interfaces are different compared to those in AD. (C) Amyloid core of human α-synuclein amyloid fibrils (PDB 2NOA), containing a Greek-key fold. (D and E) Amyloid core fibril structure of α-synuclein: polymorph rod 1a (PDB entry 6CU7) and polymorph twister 1b (PDB entry 6CU8). The authors prepared the figure with pymol.254

In Pick’s disease, the tau filament core comprises a distinct fold41 compared to the structures of AD’s PHF and SF. This suggests that a disease-specific amyloid fold might be the hallmark of clinical phenotypes, in analogy with structural strains observed in prion diseases.237 The structures of tau filaments from several brains of patients with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) confirmed this observation, revealing the presence of several structural polymorphs (Figure 5B) with a molecular fold and protofilament interfaces different to AD’s filaments.41 Additional density, not connected to tau, was observed in Pick’s disease tau filaments, suggesting a tight incorporation of biological cofactors into the structure. Structures of filaments from Pick’s disease consist of residues Lys254–Phe378 of 3R tau, explaining the selective incorporation of 3R tau in Pick bodies and the differences in phosphorylation relative to the tau filaments of AD. Interestingly, novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Importantly, residues K274–R379 of 3R tau and S305–R379 of 4R tau form the ordered core of two identical C-shaped protofilaments, indicating common driving forces do exist in tau aggregation. The core of a CBD filament comprises residues lysine 274 to glutamate 380 of tau, spanning the last residue of the R1 repeat, the whole of the R2, R3, and R4 repeats, and 12 amino acids after R4.163 The core adopts a previously unseen four-layered fold, which encloses a large nonproteinaceous density. This density is surrounded by the side chains of lysine residues 290 and 294 from R2 and lysine 370 from the sequence after R4.

Finally, heparin-induced filaments of 2N4R tau have at least four different conformations. Cryo-EM structures of three of these conformations reveal a common, kinked hairpin fold, with differences in kink, helical twist, and offset distance of the ordered core from the helical axis. 2N3R tau filaments are structurally homogeneous and adopt a dimeric core, where the third repeats of two tau molecules pack in a parallel manner.173

3.2.2. α-Synuclein Fibrils.

Unlike tau, recombinant expression of αS led to the preparation of homogeneous fibrils amenable to structure determination. A first 3D structure was proposed by ssNMR,238 revealing a Greek-key topology (Figure 5C). This structure, later classified as the polymorph “1c”,225 contains a parallel in-register arrangement with hydrophobic side chain packing and a steric zipper. Cryo-EM studies have uncovered the high-resolution structures of various polymorphs, including the familial PD mutant H50Q.239 The interprotofibril arrangement is characterized by the presence of staggered β-strands, and familial mutations H50, G51, and A53 are localized at the protofilament interface and participate to its stability. Several wild type polymorphs have been solved (Figures 5D and E), revealing different protofilament interfaces. The familial mutations are localized at crucial positions that stabilize either the intramolecular fold or the inter protofilament interface.

The atomic structures of αS fibrils extracted from brains of individuals with multiple system atrophy (MSA) have been determined by cryo-EM.240 Two types of filaments were identified (named type I and II) each composed of two protofilaments. An astonishing feature of type I and type II αS filaments is the asymmetry of their protofilaments, leading to a different solvent exposure of the critical residues (e.g., K60). Post-translational modifications of only one protofilament have been proposed to explain the different conformations of the two protofilaments in the same fibril.240 Structures of brain-derived α-synuclein fibrils are distinct from fibrils obtained by recombinant expression and in vitro aggregation, as already observed for tau filaments.

3.2.3. Aβ40/42 Fibrils.

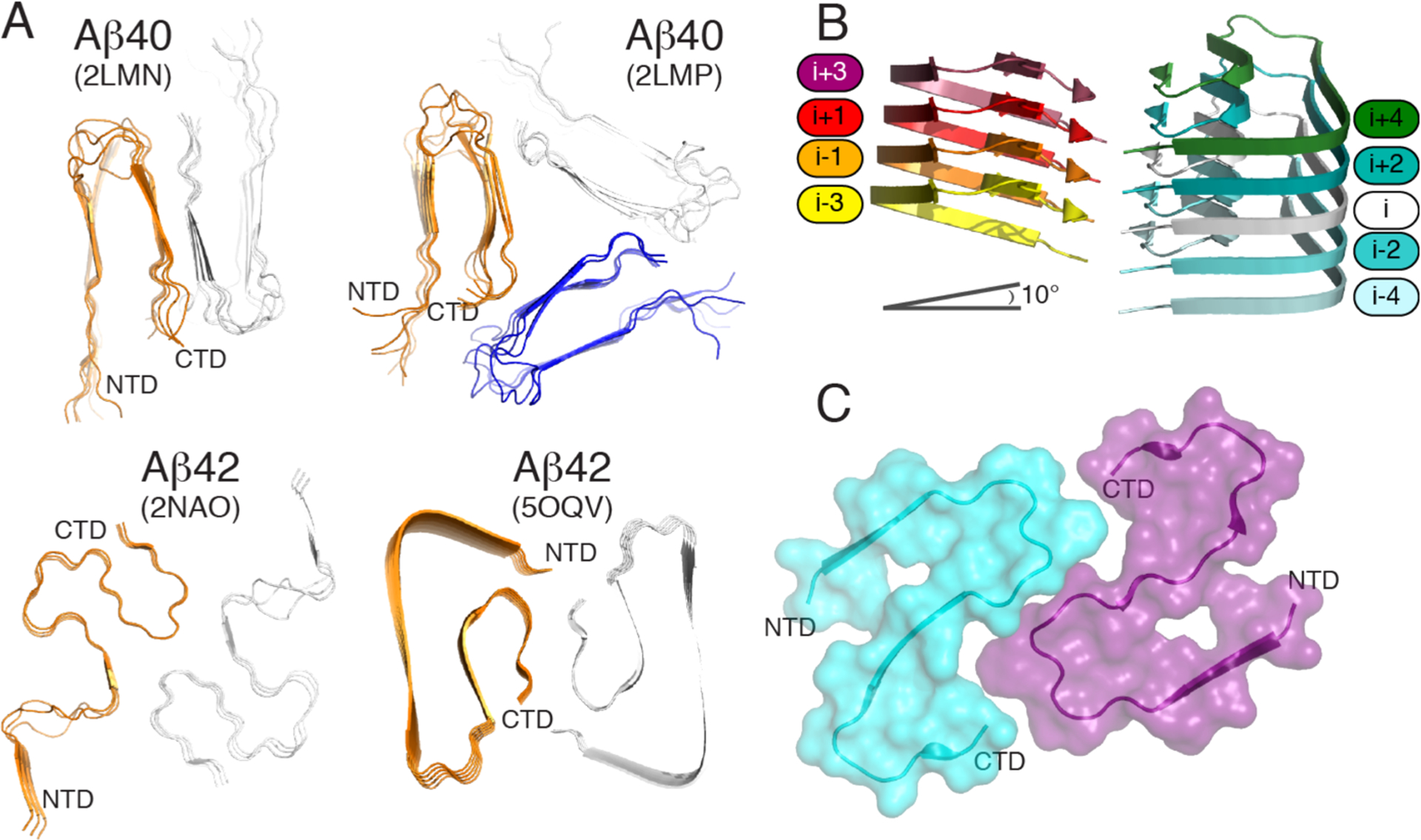

Because of its small size (compared to tau or α-synuclein proteins), its production by solid-phase peptide synthesis has offered a convenient way for numerous research groups to investigate its structure by biophysical techniques. To date, most methodological developments in structural biology of amyloid fibrils have been performed on Aβ peptides. Early studies using FTIR and CD have demonstrated the high propensity of the β-sheet structure of Aβ fragments.241 Pioneering work by the Tycko’s laboratory using solid-state242,243 determined the β-turn-β (U-shape) fold in an in-register, parallel arrangement for Aβ40 fibril with residues 12–24 and 30–40 in β-strand conformations based on distance restraints and torsion angle measurements.244

Several 3D models of AβA40 and Aβ42 (Figure 6A) have been proposed on the basis on ssNMR and cryo-EM,226,245–247 showing a diversity of intramolecular fold (U-shape or S-shape) and quaternary arrangement between Aβ40 and Aβ42. Small variations in the aggregation conditions can lead to distinct molecular conformation within the same peptide sequence and even different toxicity level.248 By combining cryo-EM and ssNMR, Schröder et al. presented a structure of Aβ42 fibrils assembled at low pH which is to date the highest resolution model of Aβ peptides.226 As already observed for other pathogenic amyloids, the staggering of nonplanar molecules (Figure 6B) constitutes a unique feature that has profound implications for fibril growth mechanisms, because the binding sites of the two fibril ends are different, implying a polarity of subunit growth. To date no high resolution of Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils extracted from brains has been solved. Tycko et al. have reported conformational studies at high resolution of Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils seeded from brain extracts.249,250 Studies of these human brain-derived fibrillar assemblies showed distinct molecular conformation by solid-state from each patient, suggesting the existence of structure-specific conformations depending on the patient AD clinical history. Comparison of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in this context revealed a predominant molecular conformation in Aβ40, while Aβ42 exhibited a larger degree of structural heterogeneity as revealed by ssNMR chemical shift analysis.250 It implies a greater structural susceptibility of Aβ42 brain seeds compared to those for Aβ40, as already suggested.251 As suggested for α-synuclein or tau, the existence of structure-based strains for Aβ40 and Aβ42, in analogy to conformational strains known for prion-like proteins, is still a matter of debate.

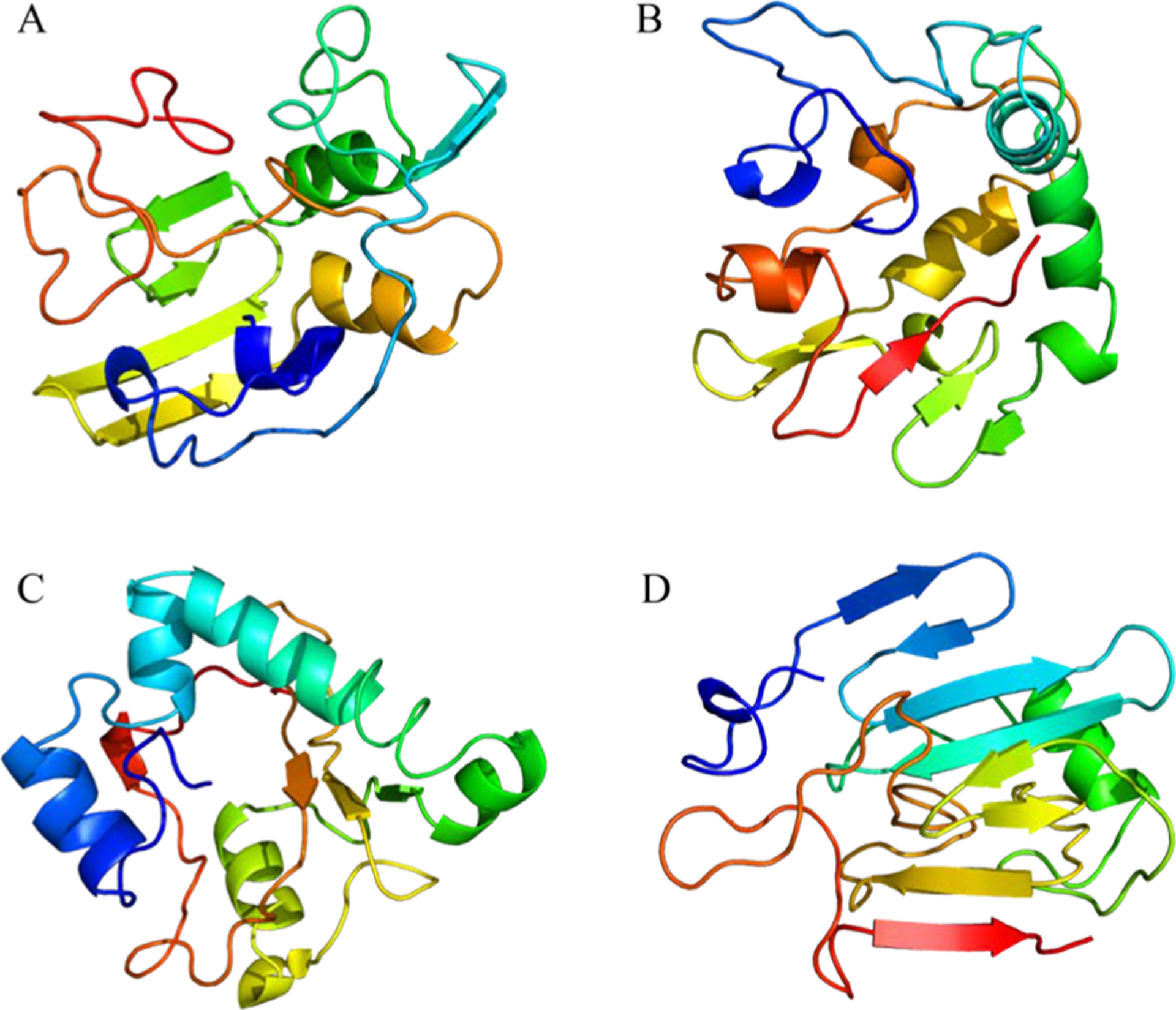

Figure 6.

(A) Orthogonal view of Aβ40 structures (PDB entries 2LMN and 2LMP) spanning residues 9–40 and Aβ42 structures (PDB entries 2NAO and 5OQV) spanning residues 1–42. (B) Cryo-EM structure of Aβ42 showing the staggered arrangement of nonplanar Aβ42 subunits. (C) Cryo-EM structure of IAPP grown at physiological pH (PDB 6Y1A) spanning residues 13–37. The authors designed the figure with pymol.254

3.2.4. IAPP Fibrils.

Previous studies based on ss NMR of IAPP place the majority of the 37 residues into the fibril core and a U-shape conformation, with the N-terminus being at the periphery, but all models display substantial deviation.216,252 A very recent study by cryo-EM at physiological pH253 provides three polymorphs with the dominant one comprising residues 13–37 with two S-shaped, intertwined protofilaments (Figure 6C). The high similarity between this model and the Aβ42 model from Gremer is striking considering the link between T2D and AD.

3.3. Structures of Transient Oligomers

3.3.1. Aβ and IAPP.

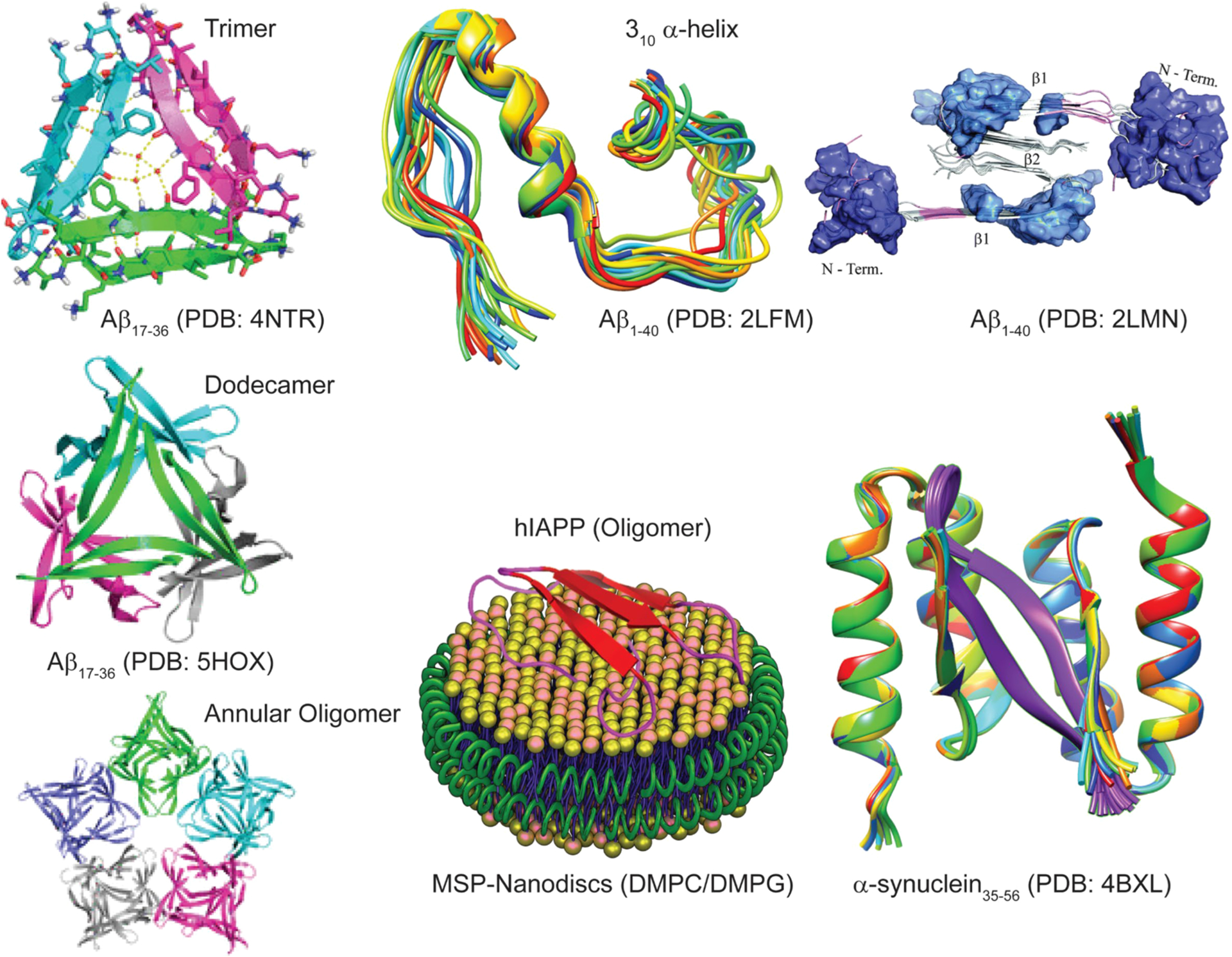

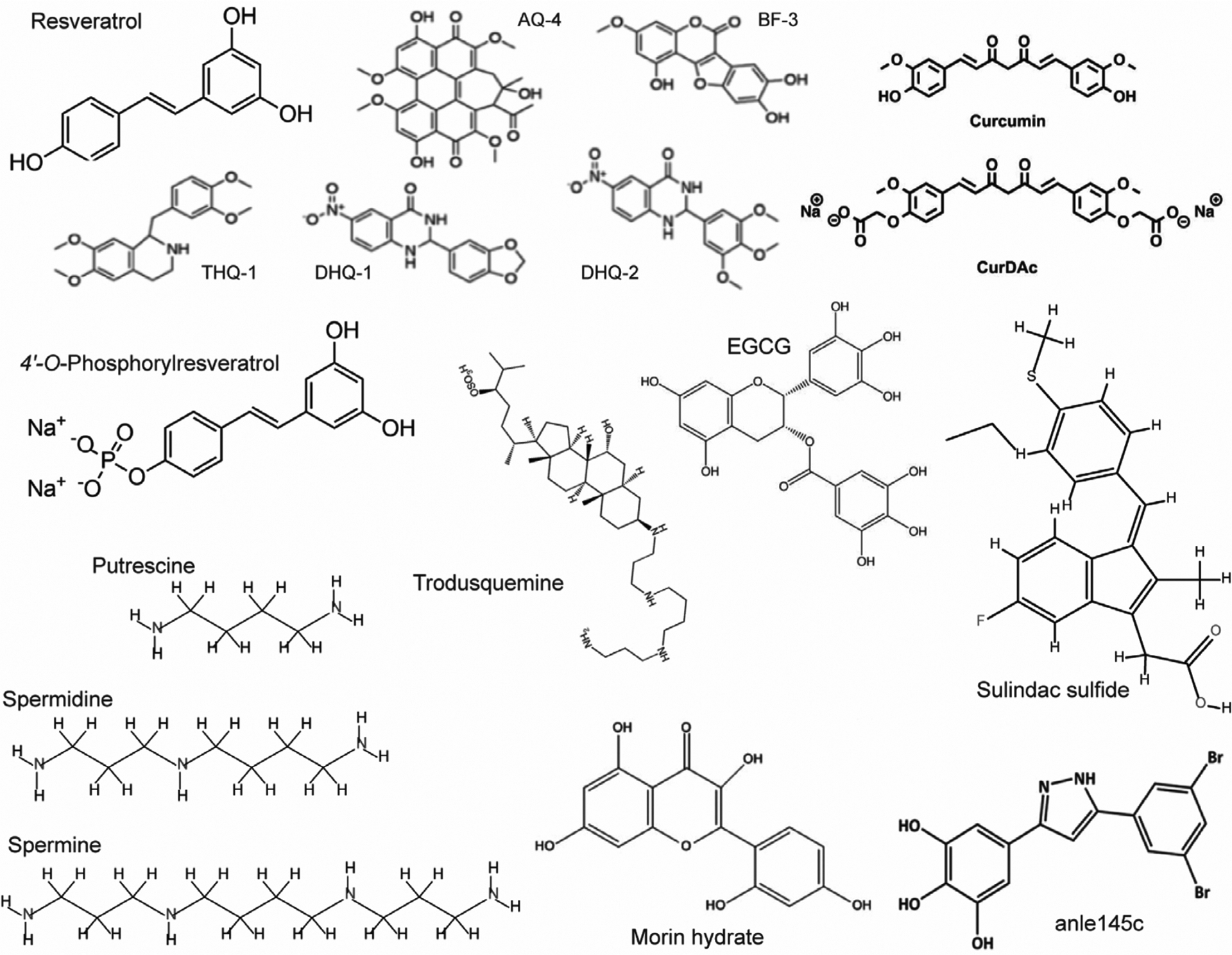

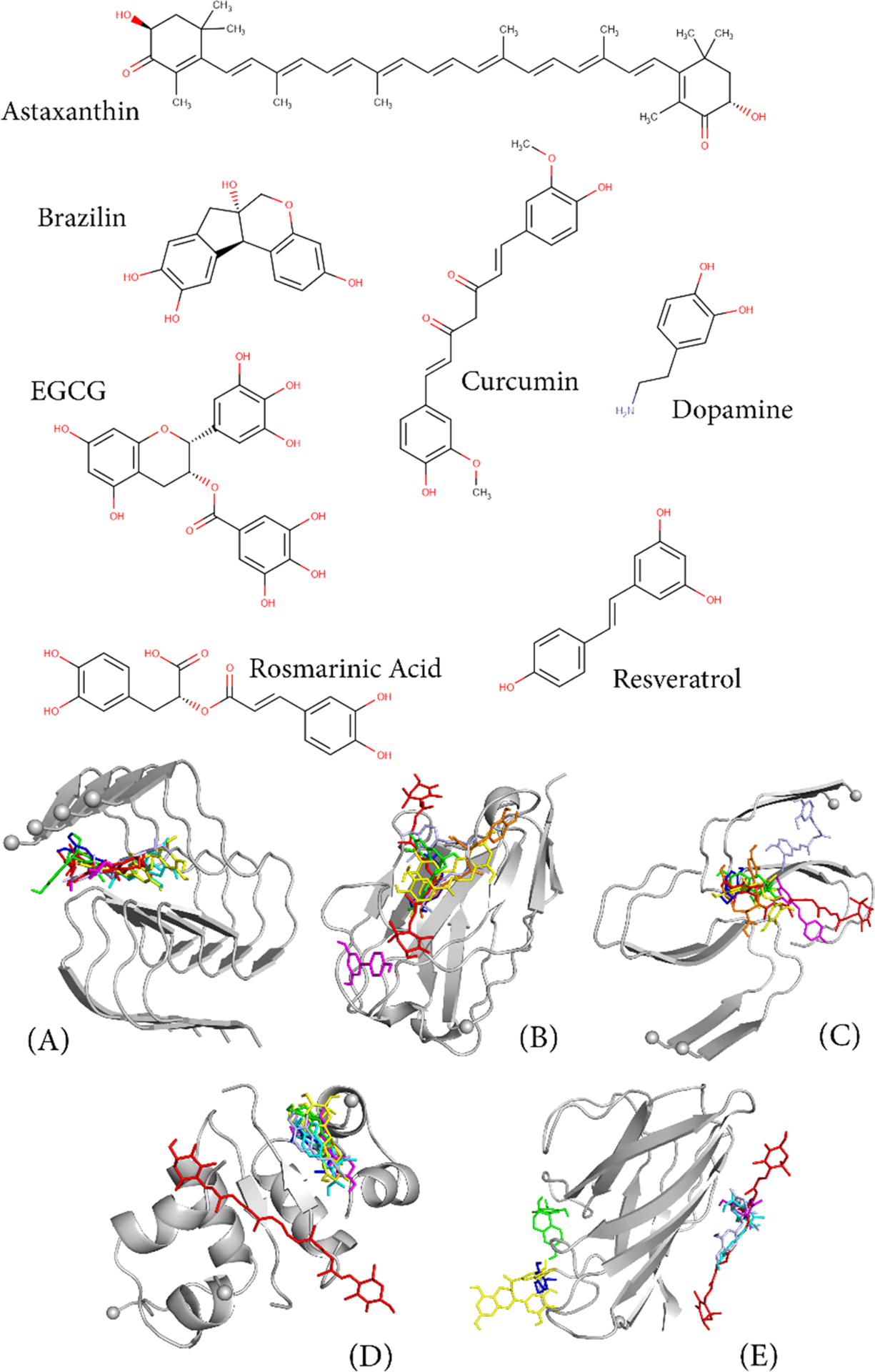

The fibrillation of Aβ is preceded by a transition from a random-coil like structure to helical conformation where the latter facilitates the formation of β-sheet structured amyloid filaments.255 The helical conformation of Aβ1–40 monomer determined by NMR in a water-detergent solution adopts a helical structure in the K16–V24 and K28–V36 regions.256 The bihelical structure is shown to be disrupted in the oxidized Aβ1–40 and adopts a single helical region between residues K16 and V24.257 Another NMR study trapped a low population of an early intermediate of Aβ1–40 characterized by a 310 α-helix (Figure 7) spanning the core hydrophobic regions H13 to D23 in an aqueous medium containing no detergent.258 The partially folded 310-helical structure has also been observed in computations259 highlighting the identification of a potential target species from an on-pathway aggregation to design small-molecule Aβ inhibitors. The phenolic inhibitor EGCG is used to study the ligand–Aβ interaction using the 310 α-helical structure and shows a tendency to bind the hydrophilic N-terminus and the α-helical (H13 to D23) region.260

Figure 7.

High-resolution structures of amyloid oligomers in solution or membrane-bound state solved using X-ray and NMR methods, with the exception being the model of Aβ40 assembly toxic surface (top, right).

Since high-resolution 3D model structure determination of pathologically relevant low- and high-ordered Aβ species is very challenging, a chemical cross-linking approach has been employed to homogenize the sample for structural determination. Macrocyclic β-sheet peptides that mimic β-hairpins of amyloid peptides and stabilize both low- and high-ordered oligomers have been developed for X-ray crystallography study.261 Using Aβ β-hairpin mimicking peptides,262 a twisted β-hairpin triangular Aβ trimer structure has been solved which also forms hexamers, dodecamers, and annular oligomers (Figure 7) through self-assembling that resembles annular structures reported for Aβ oligomers by EM.263,264 These Aβ oligomers present substantial neurotoxicity and thus are proposed to be useful molecular models of Aβ oligomer for structure-based inhibitor designing. Stable Aβ dimers and trimers characterized with parallel β-sheets and neurotoxicity have been developed by sequentially varying the position for cross-linking using chemical linkers or disulfide bridges.265–267 A combination of solution and ssNMR and AFM characterized highly disordered oligomers of Aβ that were formed in parallel to the fibril formation process.268 A recent study employed pressure-jump NMR to observe the oligomerization of Aβ.269 By combining solution NMR, DLS, EM, and wide-angle X-ray diffraction and cell viability, Melacini et al. provide an atomic resolution map of soluble Aβ toxic surfaces, with the exposure of a hydrophobic surface spanning residues 17–28 and the shielding of the N-terminus (Figure 7).270 While isolation and characterization of Aβ dimers, trimers, tetramers, etc. without chemical modification is challenging in experimental conditions, atomistic MD simulations complemented these limitations and provide high-resolution 3D structures. For example, simulations identified dimer, trimer, tetramer, and stable globular-like oligomers starting from disordered monomers with 13–23% of β-sheet content.271 While self-assembled Aβ oligomers are of interest, recent studies highlighted the formation of Aβ hetero-oligomers through cross seeding or binding to other proteins in the brain. Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 mixed oligomers are reported to have an intermediate structure between those of the self-assembled oligomers and proposed to have a large surface with antiparallel β-sheet structure.272 Aβ interaction with prion protein was reported to trap an antiparallel β-sheet oligomer but lacks a high-resolution structure; on the other hand, Aβ shows a random-coil structure when forming heterooligomers with apolipoprotein-E derived peptide fragments with enhanced neurotoxicity.273–275 Readers are referred to a review that discusses the high-resolution solution and ssNMR approaches to monitor the formation and characterization of Aβ oligomers.276

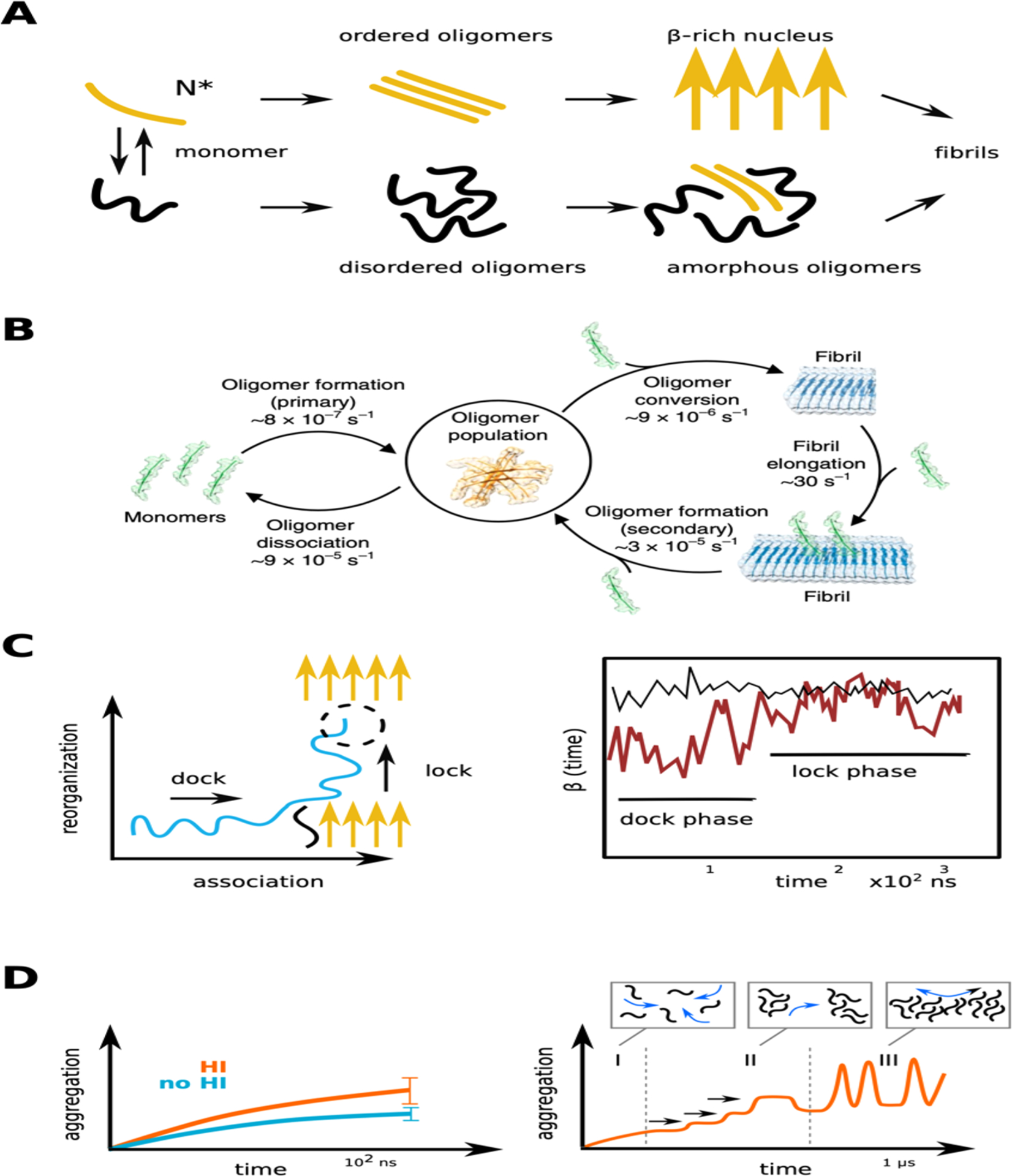

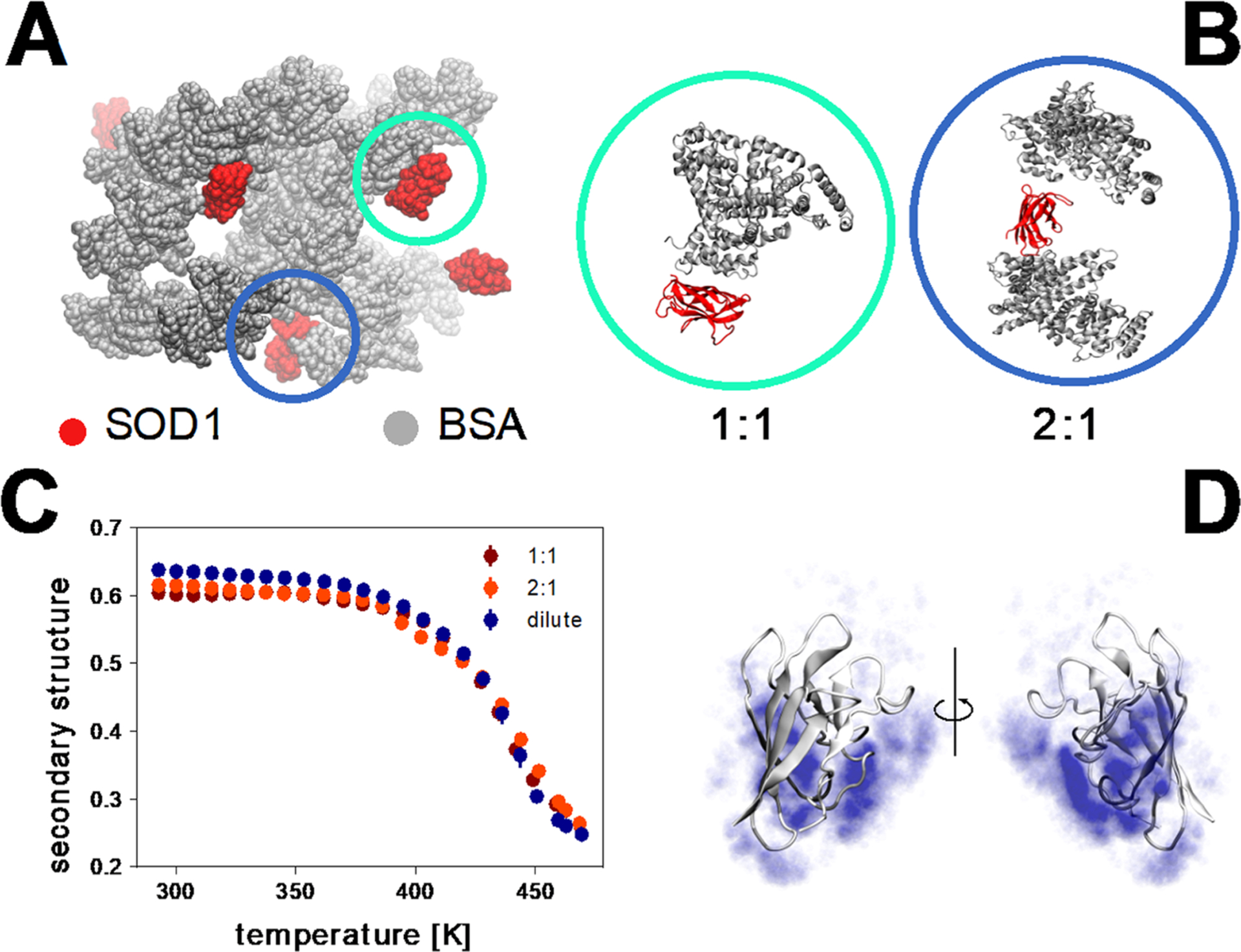

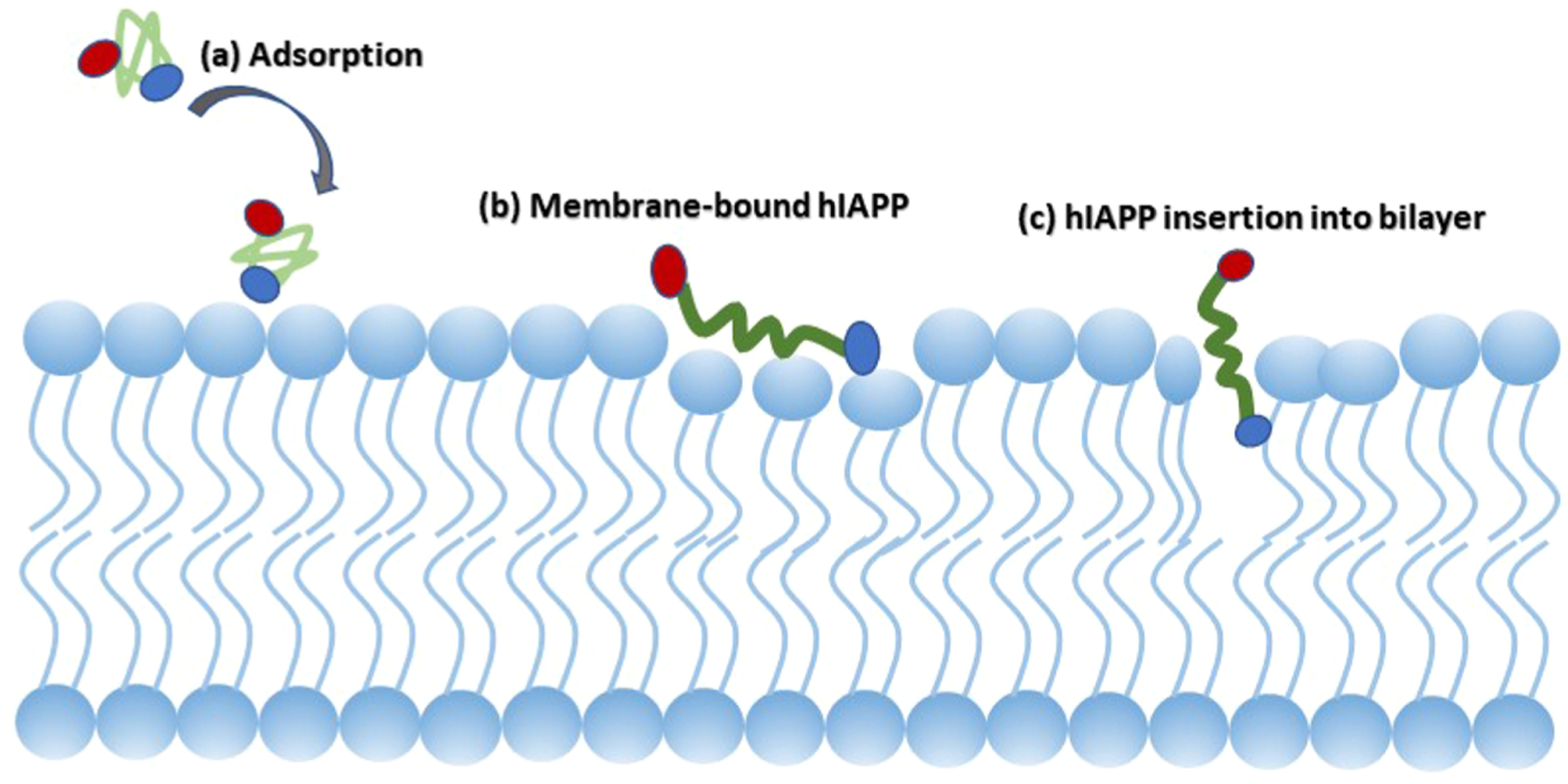

A number of biophysical techniques and different types of sample preparations have been used to investigate the aggregation mechanisms of IAPP. Helical intermediates of human-IAPP have been reported.277,278 NMR experiments have shown high-resolution structures for full-length human-IAPP,279 human-IAPP-1-19,280 and full-length rat-IAPP281 peptides both in solution as well as in a membrane environment. Investigation of the aggregation pathways revealed the formation intermediate species of IAPP,282–288 and Figure 7 shows a structure of membrane (nanodisc)-associated hIAPP oligomers. For additional details on the structure and kinetics of aggregation under various conditions, readers are referred to review articles on IAPP.289–291

3.3.2. α-Synuclein and Tau Proteins.

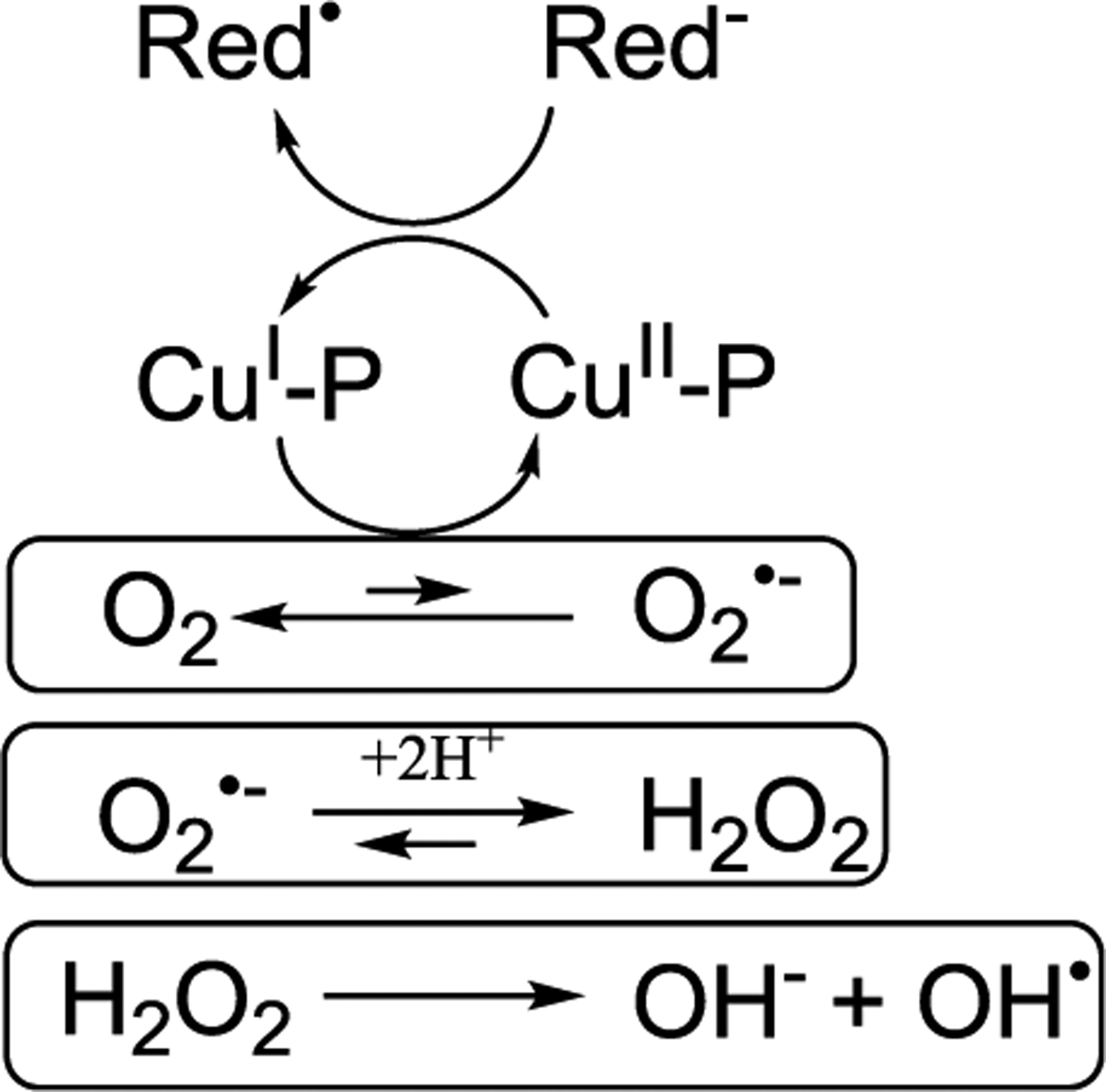

In PD, oligomerization of αS has been shown to increase in individuals with Lewy pathology. A low-resolution structural evolution of individual αS oligomers characterized by antiparallel β-sheet structure is detected using AFM-IR.292 Structural mapping of oligomers at all-stages of aggregation by AFM-IR highlighted the early oligomers (with 1 day incubation) are spherical in shape and dominated by a α-helix/random-coil secondary structure, but some of the oligomers showed mixed parallel and antiparallel β-sheet structures. The size of the spherical oligomers is observed to grow on day-2 with an increasing β-sheet and decreasing α-helix structures. Later on day-3, AFM-IR detected the presence of both spherical oligomers (α-helix/β-sheet rich structures) and protofibers with a predominant β-sheet structure.292 The structure of αS oligomers observed under cryo-EM is shown to have a cylinder-like appearance and be characterized with a predominant β-sheet structure (35 ± 5%).293 The formation of early aggregates of αS and interaction between monomers and stable bioengineered oligomers are studied using fluorescence spectroscopy by labeling αS species with differently labeled fluorophores.294 This study highlighted a comparatively higher binding affinity between oligomers as compared to oligomer–monomer/monomer–monomer interactions suggesting oligomeroligomer assembly is a major driving molecular process of aggregation in the early stages of the disease progression. Importantly, large oligomers are found to assemble to form aggregates sooner as compared to low-size oligomers (octamer > tetramer > dimer/monomer) but not competently assist nucleation and monomer recruitment.294 Another study showed αS oligomers do not seed the fibrillation reaction. This study underlined metastable spherical shape (10 nm), with a disordered conformation, for the αS oligomers by a small-angle neutron scattering method.295 Amyloid oligomers differ in their surface properties (in general hydrophobic residues are solvent exposed) which correlate to its competent membrane binding and toxicity. Hydrophobicity surface landscaping of individual αS oligomers by selective fluorescent molecules is probed using a super-resolution imaging technique.296 The hydrophobicity of the surface of the oligomers is found to be comparatively higher than that of aged fibers evidencing αS aggregation proceeds via generation of toxic intermediates characterized with hydrophobic heterogeneity like that which has been reported for amyloid proteins and peptides.296 A recent study showed that αS promotes formation of Aβ oligomers and inhibits fibrillation by stabilizing the oligomer structure.297 Notably, this effect is identified only by the soluble species of αS (monomers and oligomers) but not by fibers. EM studies revealed globular morphologies for the oligomer mixture of Aβ and αS. While structural information for the Aβ oligomers induced by αS has still not been reported, further investigation could provide more details to establish a correlation between AD and PD.297 The aggregation and folding of αS is shown to be modulated by the isomeric state of the five proline residues (P108, P117, P120, P128, and P138) located in the disordered C-terminus.298 Among the five-proline residues, isomerization of P128 is identified to be catalyzed by cyclophilin A (CypA), a protein belonging to the family of peptidylprolyl isomerases. CypA and αS are colocalized in cells, where CypA interacts with αS with a micromolar binding affinity.298 NMR titration experiments, combined with a crystal structure of the αS–CypA complex, showed CypA binds to the amyloid core preNAC hydrophobic domain (residues 47–56) of αS298 and also is known to bind membrane.299 The α-synuclein complexed by affibody displays a β-hairpin spanning residues 35–56 by NMR (Figure 7).261