Summary

Adaptive immune responses mediated by T cells and B cells are crucial for protective immunity against pathogens and tumors. Differentiation and function of immune cells require dynamic reprogramming of cellular metabolism. Metabolic inputs, pathways, and enzymes display remarkable flexibility and heterogeneity, especially in vivo. How metabolic plasticity and adaptation dictate functional specialization of immune cells is fundamental to our understanding and therapeutic modulation of the immune system. Immense progress has been made in characterizing the effects of metabolic networks on immune cell fate and function in discrete microenvironments or immunological contexts. In this review, we summarize how rewiring of cellular metabolism determines the outcome of adaptive immunity in vivo, with a focus on how metabolites, nutrients, and driver genes in immunometabolism instruct cellular programming and immune responses during infection, inflammation, and cancer in mice and humans. Understanding context-dependent metabolic remodeling will manifest legitimate opportunities for therapeutic intervention of human disease.

eTOC blurb:

Recent studies demonstrate that metabolic adaptation instructs adaptive immunity in discrete microenvironments or in response to inflammatory signals. Chapman and Chi review the emerging principle for metabolic reprogramming of lymphocyte fate and function in infection, inflammatory disease, and cancer, and discuss how lymphocyte metabolism contributes to disease pathogenesis and therapeutics.

Introduction

Adaptive immune responses are essential for the clearance of pathogens and tumors but are also implicated in the development of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Aside from immunological cues, nutrients and metabolites are major regulators of immune cell function. Also, dynamic and bidirectional interplay between immunological signals and metabolism orchestrates adaptive immunity (Chapman et al., 2020). However, there are differential requirements or compensatory roles for nutrients and metabolic enzymes in vivo compared to in vitro. As examples, extracellular serine supports T cell responses in vitro but glucose-derived de novo synthesized serine is important for T cell responses in vivo (Ma et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2019a), and certain metabolic enzymes, such as hexokinase (HK2), that are dispensable in vitro are crucial in some in vivo contexts (Gu et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2017). Also, selective nutrients or metabolic pathways can functionally compensate for glucose metabolism in certain environments in vivo (Mager et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Wu et al., 2020b). Therefore, we are only beginning to understand how immune cells undergo context-dependent metabolic adaptation to support their differentiation and function in physiologically relevant conditions.

Here, we summarize metabolic adaptation in lymphocytes under different immunological contexts in vivo. Specifically, we highlight the cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic metabolic factors that regulate adaptive immune responses to infection, inflammation, and cancer in murine models, as well as the emerging studies in the human system. A better understanding of how metabolic rewiring shapes adaptive immunity may uncover additional immunotherapies or vaccination strategies for human disease.

Metabolic adaptation in acute and chronic infection

Naïve T and B cells dynamically alter their metabolic programs upon activation. During the period of quiescence exit, glucose metabolism, nutrient uptake, and anabolism are rapidly upregulated, associated with lactate production. Moreover, mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are also increased (Boothby and Rickert, 2017; Chapman et al., 2020; Reina-Campos et al., 2021). These events are coordinated by selective transcription factors that induce gene expression programs necessary for anabolism, including MYC (Wang et al., 2011), IRF4 (Man et al., 2013), BATF (Kurachi et al., 2014), NFAT (Klein-Hessling et al., 2017; Vaeth et al., 2017), and SREBPs (Kidani et al., 2013), as well as mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-associated signaling (Tan et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013a) (Figure 1). Accordingly, inhibition of anabolic metabolism impairs the activation and proliferation of lymphocytes (Bailis et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2013; Kidani et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2016; Ron-Harel et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021a; Xu et al., 2021b; Yang et al., 2013a). Effector T and B cell subsets also display differences in glucose, polyamine, purine, lipid, and glutamine metabolism that regulate their differentiation and function (Caro-Maldonado et al., 2014; Clever et al., 2016; Ersching et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2018; Michalek et al., 2011; Puleston et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2011; Sugiura et al., 2021; Tsui et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2021). These discrete metabolic programs are also dependent upon transcription factors that can sense metabolic signals, such as HIF-1α (Clever et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2011) (Figure 1). Thus, anabolism drives cellular activation and differentiation. However, metabolic adaptation continues to occur during the course of infection, and such changes influence cell fate, function, and localization, as discussed below.

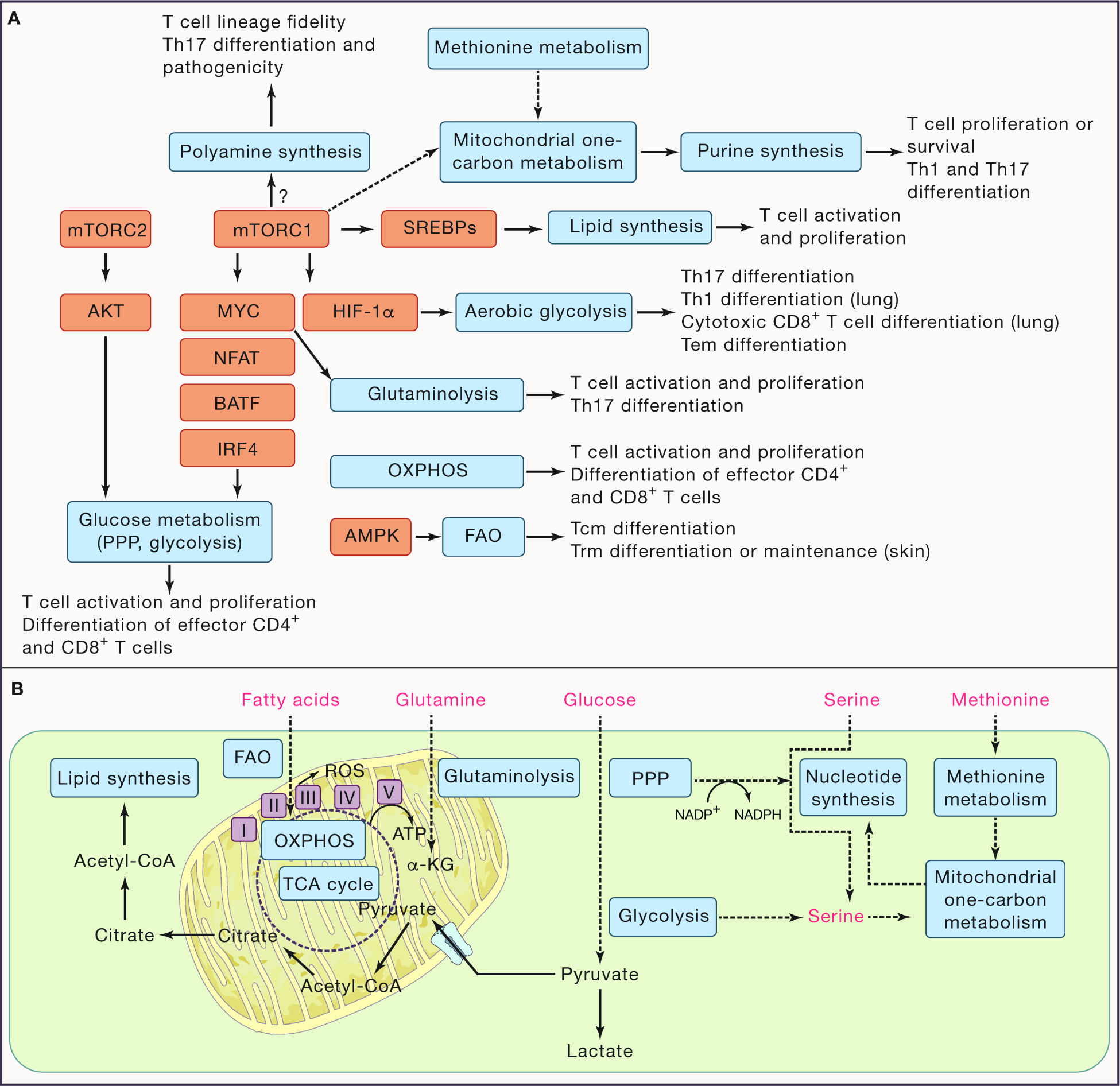

Figure 1. Signaling networks orchestrate metabolism for coordination of T cell fate.

(A) Signaling networks regulate metabolic state to tune T cell fate decisions. Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complexes 1 and 2 (mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively) orchestrate signaling to induce anabolic metabolism in T cells. Mechanistically, mTORC1 activity regulates these programs, in part, by upregulating transcriptional programs mediated by MYC, sterol regulatory binding element proteins (SREBPs), and hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α). Additional transcriptional networks regulated by NFAT, BATF, and IRF4 are also crucial to support certain anabolic processes. In contrast, AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK) activation promotes fatty acid oxidation (FAO), a catabolic program. The metabolic programs are shown in grey boxes and their impacts on the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are shown. (B) The interplay between the major metabolic pathways involved in T cell fate decisions are depicted. Key selective nutrients are shown in red. Note that serine can be de novo synthesized or acquired from extracellular sources. PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; Tcm, central memory T cell; Tem, effector memory T cell; Th, CD4+ T helper; Trm, tissue-resident T cell.

During an acute infection, activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells differentiate into terminal effector (Teff) or memory (Tmem) T cells, including circulatory effector memory (Tem) and central memory (Tcm) cells. Nutrient uptake is a key regulator of T cell activation and specialization, and nutrients are now considered to serve as ‘signal 4’ to license T cell immunity by interplaying with TCR, costimulatory, and cytokine signals (‘signals 1, 2, and 3’) (Long et al., 2021). Indeed, glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) drives glucose uptake and differentiation of effector CD4+ T cell subsets (Macintyre et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2016). Also, leucine, glutamine, methionine, and their transporters play key roles in promoting Teff cell survival and proliferation (Carr et al., 2010; Nakaya et al., 2014; Sinclair et al., 2019; Sinclair et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2021). Notably, activated CD4+ T cells express lower amount of amino acid transporters than activated CD8+ T cells, possibly due to their different composition of ribosomes and protein translation complexes, so they may be outcompeted for limited amino acids (Howden et al., 2019). Moreover, the metabolism of methionine, glutamine and arginine differs among CD4+ T cell subsets (Johnson et al., 2018; Puleston et al., 2021; Wagner et al., 2021). Meanwhile, fermentation of dietary fiber contributes to anti-influenza immunity, associated with butyrate accumulation that boosts mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism in CD8+ T cells (Trompette et al., 2018). Thus, nutrients and their transporters modulate T cell responses.

Quiescent, long-lived Tmem cells have discrete metabolic profiles than Teff cells (Figure 2), with the former displaying a metabolic profile that favors OXPHOS over aerobic glycolysis in vitro, which is partly mediated by CD28-dependent mitochondrial fusion (Buck et al., 2016; Klein Geltink et al., 2017; van der Windt et al., 2012). Circulating Tmem cells take up lower amounts of certain lipids than Teff cells in vivo, and rely more on glucose-dependent de novo fatty acid synthesis to fuel a ‘futile’ cycle of fatty acid oxidation (FAO); nonetheless, glycerol uptake also contributes to lipid synthesis for the differentiation and survival of Tmem cells (Cui et al., 2015; O’Sullivan et al., 2014). Such a ‘futile’ cycle likely exists only in certain contexts, as deletion of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1), an enzyme involved in fatty acid synthesis, results in a marked increase of mitochondrial metabolism partly fueled by oxidation of exogenous fatty acids, and also improves CD4+ Tmem formation upon parasitic infection (Endo et al., 2019). FAO is induced by AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK) signaling, and promotes Tmem development by inducing ketogenesis (Ma et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2020b). However, unlike pharmacological inhibition using etomoxir, deletion of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1a), the rate-limiting enzyme of long-chain FAO, does not impair Tmem formation in vivo (Pearce et al., 2009; Raud et al., 2018), suggesting the presence of alternative carbon sources for OXPHOS. Of note, ATP produced via aerobic glycolysis is sufficient for Tmem cell differentiation and persistence in certain contexts (Phan et al., 2016). This finding implies that net ATP production, rather than an absolute reliance on OXPHOS, is an important determinant of Tmem cell accumulation.

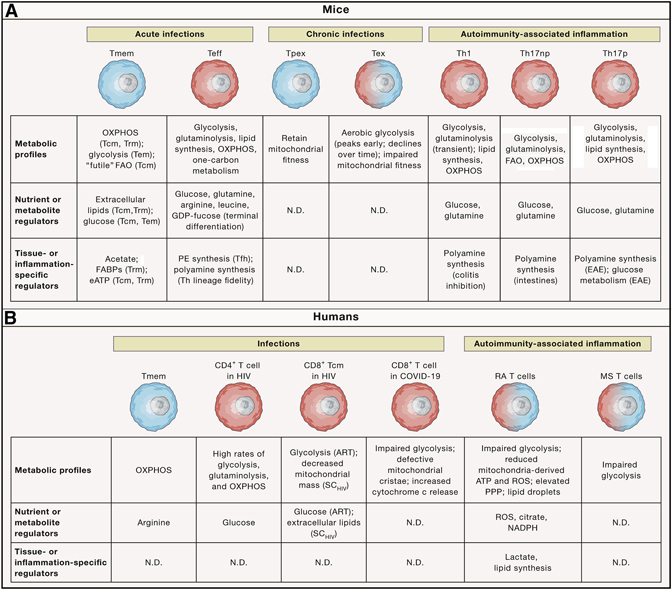

Figure 2. Metabolic reprogramming in response to infection or autoimmune inflammation.

Metabolic adaptation occurs in acute or chronic infection and autoimmunity-associated inflammation. A summary of the metabolic profiles, nutrient or metabolic regulators, and tissue- or inflammation-specific regulators that orchestrate metabolic reprogramming in the representative murine (upper) and human (lower) T cell populations. Small, blue cells display more catabolic metabolism; large, red cells are anabolic; and intermediate-sized cells with blue–red gradient coloring represent cells that display some features of anabolism and catabolism. Labels in parentheses indicate the specific contexts (e.g. cell subset or disease) in which the metabolic pathways or regulators have been shown to be functionally important. ART, antiretroviral therapy; eATP, extracellular adenosine triphosphate; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MS, multiple sclerosis, N.D., not determined; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SCHIV, spontaneous HIV controller; Tcm, central memory T cell; Teff, effector T cell; Tem, effector memory T cell; Tex, terminally exhausted T cell; Th, CD4+ T helper; Th17np, non-pathogenic Th17; Th17p, pathogenic Th17; Tmem, memory T cell; Tpex progenitor of exhausted T cell; Trm, tissue-resident T cell.

Nutrient availability shapes Tmem cell differentiation and function. Specifically, butyrate supports the memory potential of activated CD8+ T cells by remodeling metabolism such that fatty acid and glutamine catabolism, rather than glucose, fuels OXPHOS (Bachem et al., 2019). Accordingly, deletion of the glutamine transporter Slc38a2 reduces Teff but enhances circulatory Tmem cell generation following acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, with similar effects observed upon deletion of the arginine transporter Slc7a1 (Huang et al., 2021b). Enhanced Tmem cell generation in these contexts is associated with impaired mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) activation, extending upon observations that rapamycin treatment increases Tmem cell accumulation (Araki et al., 2009; Pearce et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2010). These studies are in line with observations that arginine and glutamine, as well as leucine, license mTORC1 activity in lymphocytes (Do et al., 2020; Nakaya et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2019; Sinclair et al., 2013). Of note, human Tmem cells require arginine catabolism for their survival (Geiger et al., 2016), which is dependent on the transcriptional regulators, C3PO (encoded by TSN), BAZ1B, and PSIP1, but not mTORC1. Future investigations are warranted to determine amino acid-induced signaling mechanisms for Tmem cell generation, long-term survival, or functionality.

Metabolites are substrates for posttranslational modifications that regulate lymphocyte biology (Araujo et al., 2017; Chapman et al., 2020; Su et al., 2020; Swamy et al., 2016). For instance, protein acetylation, which contributes to T cell differentiation, survival, and function, is dependent upon acetyl-CoA that is derived from glucose, fatty acids, or acetate (Peng et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2019). Pofut1-dependent protein fucosylation (wherein GDP-fucose is covalently conjugated to target proteins) is a metabolic driver of Teff and Tmem responses after infection (Huang et al., 2021b). Loss of Pofut1 or GDP-fucose metabolism-related enzymes (encoded by Gmds and Fcsk) causes Teff cells to accumulate in a transitional state (called Tint), which can further differentiate into either terminal Teff or memory precursor cells. How metabolism-associated posttranslational modifications tune Tmem cell heterogeneity remains important to address. As aerobic glycolysis is upregulated in Tem cells to facilitate their formation (Phan et al., 2016), future studies are warranted to determine if glycolysis-regulated glycosylation of proteins, glycans, or lipids contributes to these effects (Araujo et al., 2017; Swamy et al., 2016). Collectively, nutrient transport, metabolic programs, and intracellular signaling cooperatively regulate T cell fate and function during acute infection.

Chronic infection and persistent antigen stimulation alter lymphocyte function as compared with acute infections. Specifically, exhausted T (Tex) cells express certain coinhibitory molecules and show decreased proliferation and production of effector cytokines, which are coordinated by stepwise changes in cellular, transcriptional and epigenetic profiles (Collier et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2018). These cellular alterations are considered to be beneficial in preventing immunopathology during chronic infection.

Substantial metabolic changes occur during chronic as compared with acute LCMV infection, including dampened glycolysis and OXPHOS early after infection that persist over time. Additionally, GLUT1 expression and glucose uptake are reduced, and depolarized mitochondria that produce excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulate (Bengsch et al., 2016). Mechanistically, aberrant mTOR signaling drives mitochondrial dysfunction in cells with exhausted features early during chronic infection. In established chronic LCMV infection, the metabolic alterations, especially defective mitochondrial fitness, occur exclusively in terminal Tex cells, and antagonism of PD-1 signaling rectifies the dysfunctional metabolic profiles of early Tex cells (Bengsch et al., 2016; Gabriel et al., 2021). In contrast, precursors of Tex (Tpex) cells (a stem-like subset that can self-renew and act as the precursor for terminal Tex cells (Collier et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2018)) display enhanced transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling to suppress mTOR activation, thereby preserving their stem-like metabolic features and preventing terminal Tex cell differentiation (Gabriel et al., 2021). Specific metabolic drivers of Tpex versus terminal Tex cells or mTOR signaling may therefore modulate immune responses to chronic infection.

T cell metabolism in tissue specialization and trafficking

During an acute infection, host–pathogen and cell–cell interactions alter the local composition of nutrients and metabolites for temporospatial regulation of adaptive immunity (Kedia-Mehta and Finlay, 2019). Acetate regulates the induction or accumulation of T helper 17 (Th17) and Th1 cells in the intestines (Park et al., 2015), as well as IgA generation (Takeuchi et al., 2021). Further, during acute bacterial infection, serum acetate concentration transiently increases, and acetate facilitates metabolic and epigenetic programming to promote CD8+ T cell effector function in glucose-restricted environments (Balmer et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2019). Acetate conditioning of in vitro-derived Tmem-like cells improves their recall responsiveness by increasing acetylation of the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAPDH) (Balmer et al., 2016). However, sites of infection contain up to 20-fold higher acetate concentration than serum, which impedes the pro-inflammatory functions of Tmem cells and instead allows for tissue repair (Balmer et al., 2020). Mechanistically, exposure to high concentration of acetate upregulates glutaminolysis that favors OXPHOS over glycolysis. Collectively, acetate serves multifactorial roles in regulating infection-associated inflammatory processes.

Tissue-resident memory (Trm) cells express surface receptors, including CD103, that favor tissue retention in non-lymphoid tissues (Reina-Campos et al., 2021). The transcription factor Bhlhe40 induces mitochondrial gene expression in Trm cells for their survival and function (Li et al., 2019a). Trm cells may also have discrete nutrient requirements than circulating Tmem cells. For instance, Trm cells are found in the skin epidermis that is enriched for exogenous free fatty acids (Jiang et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2017). Accordingly, skin Trm cells acquire more exogenous fatty acids than Tem or Tcm cells, which promote OXPHOS in skin Trm but not Tcm cells (Pan et al., 2017). Uptake of exogenous fatty acids by skin Trm cells is mediated by intracellular fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs), specifically FABP4 and FABP5, that facilitate lipid trafficking and signaling. Moreover, tissue-specific signals drive expression of distinct FABPs in Trm populations in the skin (FABP4 and FABP5), liver (FABP1), and intraepithelial region of the small intestine (FABP1, FABP2, and FABP6) (Frizzell et al., 2020). Accordingly, accumulation and function of skin Trm cells require FABP4 and FABP5, whereas liver Trm cells require FABP1 (Frizzell et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2017). FABP4 and FABP5 expression is induced by PPARγ, a transcription factor activated by certain lipid moieties (Pan et al., 2017). In addition, extracellular ATP, which can accumulate in inflamed or damaged tissues, signals via the purinergic receptor P2RX7 to promote circulatory Tcm and intraepithelial Trm development. Mechanistically, extracellular ATP tunes mitochondrial metabolism via activation of AMPK, which promotes Tcm or Trm cell differentiation, or by synergizing with TGF-β signaling to upregulate CD103 expression (Borges da Silva et al., 2018; Borges da Silva et al., 2020). However, P2RX7 signaling can either promote or inhibit Trm cell persistence, which is possibly time- or microbiota-dependent (Borges da Silva et al., 2020; Stark et al., 2018). Certain bile acids also drive the formation and possibly tissue residency of Th17 cells (Hang et al., 2019). Thus, the interplay among nutrients or metabolites and metabolic and/or signaling networks orchestrates microenvironment-specific programs in T cells.

Metabolism affects lymphocyte migration. First, mitochondria direct lymphocyte trafficking, with Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission mediating chemokine-induced migration and extravasation (Campello et al., 2006; Quintana et al., 2007; Simula et al., 2018). Moreover, local ATP sensing by purinergic receptors tunes mitochondrial metabolism in different cellular regions to orchestrate cell migration. Specifically, P2X4 promotes mitochondrial metabolism in the pseudopod, while P2Y11 inhibits mitochondrial metabolism in the uropod (Ledderose et al., 2020; Ledderose et al., 2018). Aside from ATP, other metabolites also control lymphocyte migration and functionality. PI3K–Akt–mTOR-induced anabolic metabolism regulates generation and function of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, germinal center (GC) B cells, and plasma cells (Choi et al., 2018; Ersching et al., 2017; Ray et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2016a; Zeng et al., 2016), although little is known about their unique metabolic requirements. GCs display enrichments for ether lipid species, including phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (Jones et al., 2020). Moreover, de novo PE synthesis via the CDP–ethanolamine pathway promotes GC formation and humoral immunity by acting as an intrinsic regulator of Tfh cell differentiation. Mechanistically, PE stabilizes the follicular homing receptor CXCR5 on the cell surface, thereby facilitating CXCR5-dependent follicular migration (Fu et al., 2021). How metabolites interface with chemotactic signaling to regulate cell migration and tissue localization remains underexplored.

Whether regional changes in metabolic processes influence infection-induced cell fate is of growing interest. White adipose tissue (WAT) contains multiple Tmem subsets that localize to fatty bodies, which accumulate upon mucosal infection (Han et al., 2017). Secondary pathogen exposure induces lipid metabolic remodeling in WAT, associated with enhanced secretion of lipids, including glycerol, whose import via aquaporin-9 fuels OXPHOS in circulatory Tmem cells (Cui et al., 2015; Han et al., 2017). Lymphocytes are also distributed in discrete regions of the small intestine, with the metabolic requirements yet to be defined. Mitochondrial metabolism is orchestrated by mitochondrial cardiolipins to maintain the activated state of intraepithelial Trm cells (Konjar et al., 2018), although cardiolipins also contribute to Teff and circulatory Tmem responses (Corrado et al., 2020). Whether discrete metabolic signals regulate Trm cell accumulation in other intestinal regions (e.g. Peyer’s patches or lamina propria) or in other organs (e.g. lung interstitium versus parenchyma) will be important to explore. Collectively, metabolic adaptation regulates lymphocyte migration to and retention in tissues or regions within tissues.

Metabolic reprogramming in autoimmune inflammation

In addition to infection, inflammation also occurs in autoimmune disease, which is characterized by dysregulated adaptive immune responses that underlie inflammation and tissue damage (Crotty, 2019; Lee et al., 2021). Cellular metabolic programs also contribute to autoimmunity (Figure 2). Glycolysis drives the generation of Th1 and Th17 cells that induce colitis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE; a murine model of multiple sclerosis), with Th17 cells displaying high glycolytic rate mediated by HIF-1α (Dang et al., 2011; Gerriets et al., 2015; Michalek et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021a; Yang et al., 2013a). Accordingly, high glucose uptake promotes Th17 cell differentiation and exacerbates autoimmune inflammation (Zhang et al., 2019). Additionally, glucose metabolism provokes spontaneous Tfh and GC reactions in a mouse model of system lupus erythematous (SLE) (Choi et al., 2018). Further, insulin receptor signaling in T cells promotes glucose uptake and mitochondrial respiration, which are associated with their ability to drive colitis (Tsai et al., 2018). It is currently unknown whether dysregulated insulin signaling in T cells contributes to the pathogenesis of metabolic syndromes.

Glutamine metabolism also supports Th17 cell differentiation. Deficiency of glutaminase (GLS) inhibits Th17 cell differentiation that is associated with altered epigenetic programming and reduced production of glutathione, which maintains the redox state and pathogenic function of Th17 cells in EAE (Johnson et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2018; Mak et al., 2017). Such effects are consistent with observations that glutamine depletion or abrogation of glutamine transport via ablation of ASCT2 reduces Th17 cell differentiation (Nakaya et al., 2014). Dimethyl fumarate is a therapeutic agent for multiple sclerosis and exerts its anti-inflammatory effects, in part, by inhibiting activity of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH (Kornberg et al., 2018). In addition, dimethyl fumarate treatment leads to glutathione depletion, resulting in increased ROS production that reduces IL-17 production by murine and human CD8+ T cells (Luckel et al., 2019). It is noteworthy that glutamine depletion or deficiency of ASCT2, but not loss of GLS, leads to sustained inhibition of Th1 cell differentiation over time (Johnson et al., 2018; Nakaya et al., 2014). Instead, GLS-deficient Th1 cells upregulate mTORC1 activity at the later stages of activation to support their proliferation and functional fitness (Johnson et al., 2018). Moreover, reduced glutathione production that occurs as a consequence of GLS deficiency may lead to an upregulation of serine-dependent one-carbon metabolism to allow for Th1 cell accumulation (Johnson et al., 2018; Kurniawan et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2017; Ron-Harel et al., 2016; Sugiura et al., 2021). Thus, activated T cell subsets are metabolically flexible across time and in different inflammatory contexts.

Glucose and glutamine metabolism support mitochondrial function, which also promotes autoimmune inflammation. The intracellular metabolite BH4 is crucial for regulating mitochondrial redox state, and BH4 production in T cells via the rate-limiting enzyme GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) promotes autoimmune inflammation (Cronin et al., 2018). Although Th17 cells are highly glycolytic (Gerriets et al., 2015; Michalek et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011), reprogramming of mitochondrial metabolism and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) activity can overcome the requirements for glycolysis in the generation of intestinal Th17 cells; however, glycolysis is essential for survival in hypoxic environments (Wu et al., 2020b). C1q, which initiates the classical complement pathway, modulates mitochondrial fitness via globular C1q receptor (called p32–gC1qR) to restrain self-reactive CD8+ T cell responses (Ling et al., 2018). Also, polyamine metabolism displays discrete activity in different CD4+ T cell subsets, and orchestrates their lineage fidelity and inflammatory properties. Mechanistically, polyamine metabolism regulates acetyl-CoA production and epigenetic remodeling in CD4+ T cells (Puleston et al., 2021; Shi and Chi, 2021; Wagner et al., 2021). In addition, purine synthesis induced downstream of the one-carbon metabolic pathway is essential for the differentiation and function of Th1 and Th17 cells in autoimmune models (Sugiura et al., 2021). Thus, multiple metabolic networks tune T cell-dependent autoimmune inflammation.

Non-pathogenic Th17 cells are stem-like, while pathogenic Th17 cells show features of terminal differentiation in response to inflammatory and metabolic cues (Karmaus et al., 2019; Wagner et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2015). Non-pathogenic Th17 cells have lower polyamine synthesis rate than Th1 or Th2 cells, while pathogenic Th17 cells have higher rates of arginine catabolism and polyamine synthesis than non-pathogenic Th17 cells (Puleston et al., 2021; Wagner et al., 2021). Further, polyamine synthesis is critical for driving EAE pathogenesis triggered by pathogenic Th17 cells (Wagner et al., 2021). Pathogenic Th17 cells also have higher glycolytic rate that supports their generation and function in promoting EAE (Karmaus et al., 2019; Wagner et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020b). Finally, CD5L regulates lipid and cholesterol composition that contributes to Th17 pathogenicity (Wang et al., 2015). Collectively, metabolism is a key determinant of lymphocyte dysfunction in autoimmunity.

Metabolic rewiring in obesity-associated inflammation

Inflammation also occurs in obesity, and recent studies show that the metabolic state and function of lymphocytes are altered in obesity and its associated diseases. Adipose tissues are reservoirs of immune cells whose composition and inflammatory status change in response to obesity (McLaughlin et al., 2017). Adipose tissue–immune cell interactions and inflammation govern systemic glucose and fatty acid metabolism (Lercher et al., 2020). Moreover, obesity and obesity-associated inflammation drive functional and phenotypic changes in conventional T cell populations, including the induction of senescence- or exhaustion-like programs in CD8+ T cells (Porsche et al., 2021; Shirakawa et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2010). Fatty acid synthesis is essential for Th17 cell differentiation (Berod et al., 2014; Endo et al., 2015), and Th17 cell accumulation is elevated among effector–memory phenotype CD4+ T cells in high fat diet (HFD)-associated obesity (Endo et al., 2015). Mechanistically, HFD increases expression of ACC1 and other enzymes in the de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway in these CD4+ T cells to exacerbate the development of EAE (Endo et al., 2015). Thus, obesity leads to marked changes in T cell activation state, with alterations in fatty acid metabolism partially contributing to these effects.

How obesity shapes lymphocyte metabolism and adaptive immune responses in different contexts is also emerging. HFD is associated with increased tumor growth rates, which often correlates with reduced accumulation and function of intratumoral CD8+ T cells (Ringel et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). In an MC38 adenocarcinoma model, tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells reduce pathways associated with lipid uptake but not FAO in HFD, whereas tumor cells increase both lipid uptake and FAO gene expression programs, which likely contribute to metabolic dysfunction and dampened accumulation and function of CD8+ T cells (Ringel et al., 2020). In contrast, obesity promotes FAO in CD8+ T cells in a murine breast cancer model, which is mediated by PD-1–STAT3 signaling and is associated with reduced CD8+ T cell function (Zhang et al., 2020a). Moreover, tumor-adjacent mammary fat tissue produces leptin, which induces STAT3 signaling and FAO, but inhibits glycolysis, in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Zhang et al., 2020a). Thus, HFD can alter lipid metabolism that drives intratumoral CD8+ T cell dysfunction. Whether HFD has effects on Tpex or terminal Tex cell differentiation in the TME is unknown.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a metabolic disorder that is mediated, in part, by intrahepatic Th17 cells, whose proinflammatory functions are driven by PKM2-dependent glycolysis (Moreno-Fernandez et al., 2021). NAFLD can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that causes liver disease and cancer (Huang et al., 2021a). T cells are important for NASH development (Dudek et al., 2021). Indeed, CXCR6+CD8+ T cells accumulate in the liver during obesity and NASH, which is mediated by IL-15 and inactivation of the transcription factor FOXO1. Subsequent exposure to acetate equips these cells with the capacity to kill hepatocytes, leading to release of extracellular ATP that signals via P2XR7 to further enhance CXCR6+CD8+ T cell pathogenicity and promote liver damage. CXCR6+CD8+ T cells express P2RX7 and the transcription factor Bhlhe40 that regulate mitochondrial function (Borges da Silva et al., 2018; Borges da Silva et al., 2020; Dudek et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019a), but whether mitochondrial fitness contributes to their function and maintenance during NASH requires further investigation.

Nutrients and cellular metabolism in antitumor immunity

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is characterized by nutrient competition or coordination between tumor cells and infiltrating immune cells that impacts antitumor immunity (Li et al., 2019b; O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Below, we describe the roles of metabolic reprogramming in the functional adaptation and antitumor activity of lymphocytes (Figure 3).

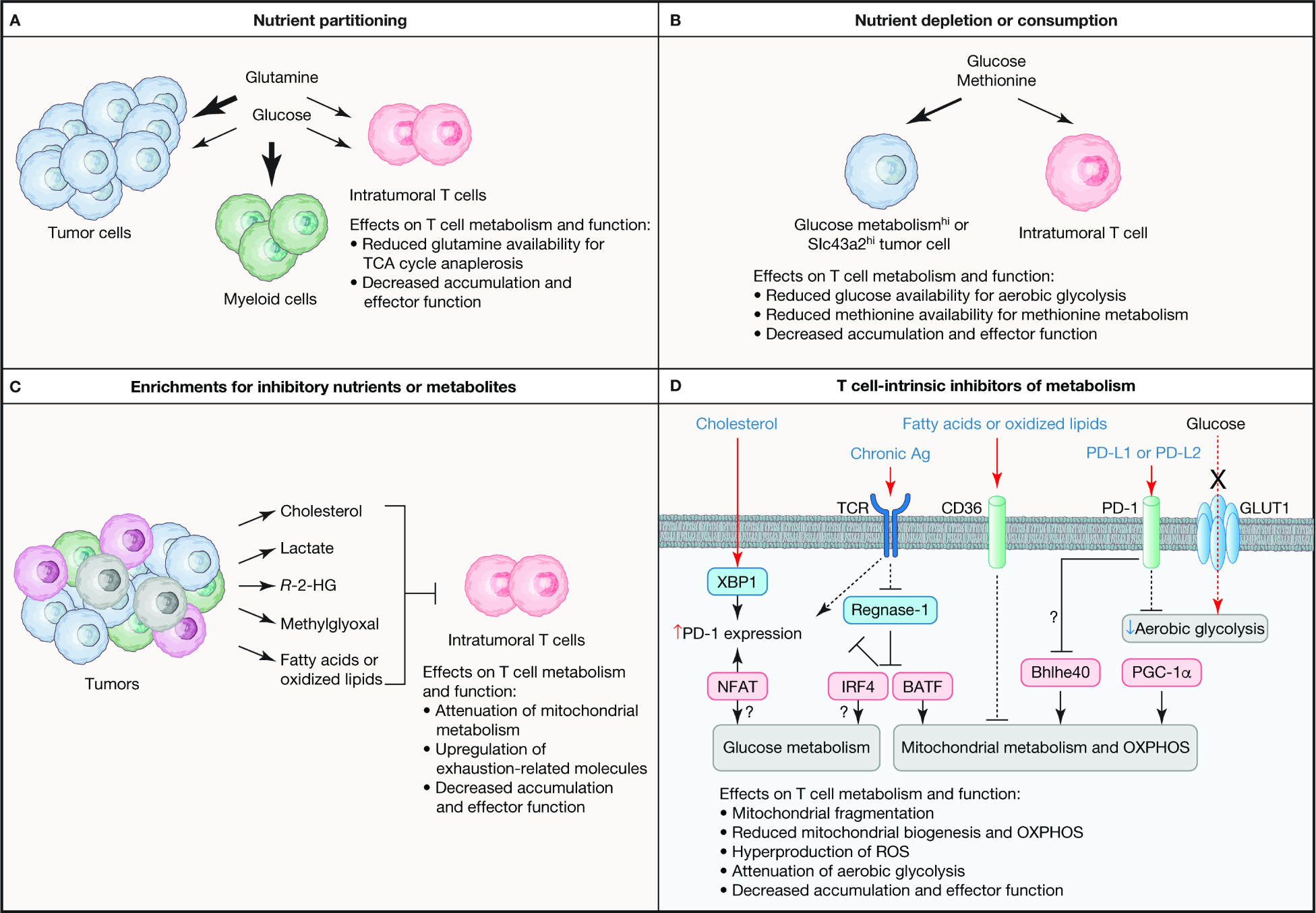

Figure 3. Mechanisms for inhibition of T cell metabolism in the TME.

Intratumoral T cells show defects in metabolic programs that are associated with their dysfunction, with both cell-extrinsic and -intrinsic mechanisms orchestrating metabolic adaptation in the TME. (A) Nutrient partitioning in the TME contributes to dysfunctional T cell responses. Specifically, glucose is preferentially consumed by tumor-infiltrated myeloid cells, which creates competition between tumor cells and intratumoral T cells for glutamine. In instances where tumor cells have elevated glutamine consumption as compared with T cells, glutamine-dependent regeneration of TCA cycle metabolites is impaired, leading to reduced T cell accumulation and function in the TME. (B) Certain tumor cells have higher rate of aerobic glycolysis (indicated as Glucose metabolismhi) or increased expression of the methionine transporter Slc43a2 (denoted as Slc43a2hi) than intratumoral T cells, resulting in depletion or consumption of these nutrients. Restriction of glucose or methionine reduces glucose and mitochondrial metabolism in intratumoral T cells, thereby limiting the accumulation and function of these cells. (C) The tumor is a source for nutrients and metabolites that restrain intratumoral T cell function, such as by suppressing mitochondrial metabolism or increasing the expression of exhaustion-related proteins. See the main text for more details. (D) T cell-intrinsic regulators also reprogram metabolism in the TME to impede T cell function. Mitochondrial metabolism and OXPHOS are antagonized by chronic antigen (Ag) stimulation of the T cell receptor (TCR) or extracellular fatty acids or oxidized lipids that are transported into cells via CD36. TCR signals induce glucose and mitochondrial metabolism, in part, by inactivating Regnase-1 that acts to restrain IRF4 and BATF activity, which suppresses PD-1 expression. However, chronic antigen stimulation can also promote upregulation of PD-1 via NFAT. PD-1–PD-L1 or PD-L2 signaling may inactivate the transcription factor Bhlhe40, which is important to upregulate mitochondrial metabolism in certain contexts, with PD-1 signaling also being further amplified by the cholesterol-dependent activation of XBP1 that can induce PD-1 expression. Intratumoral T cells also have low expression of the transcription factor PGC-1α that is important for mitochondrial biogenesis. Moreover, glucose metabolism is often inhibited in intratumoral T cells, which may be mediated by PD-1 signaling, as well as intrinsic defects in glucose metabolism, such as reduced expression of GLUT1 or glycolytic enzymes. R-2-HG, R-2-hydroglutarate.

Glucose metabolism profoundly influences antitumor immunity. Tumor-infiltrating T cells show impaired glucose metabolism, with defective activity of enolase 1, a crucial glycolytic enzyme, contributing to these effects (Gemta et al., 2019; Siska et al., 2017). In addition, intratumoral glucose concentration is limiting (Ho et al., 2015; Scharping et al., 2016), as rapidly dividing tumor cells consume more glucose than T cells, thereby impinging on T cell function (Chang et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). Mechanistically, glucose restriction is associated with reduced NFAT activity, due to impaired intracellular calcium release mediated by the glycolytic intermediate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) binding to and inhibiting SERCA channels; accordingly, enforcing PEP production by T cells improves antitumor immunity (Ho et al., 2015). Similarly, enhancing aerobic glycolysis by deleting the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) protein increases Trm programming and improves antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells (Liikanen et al., 2021). Ectopic expression of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) also increases glycolysis by preventing the autophagic degradation of the glycolytic enzyme HK2 to facilitate activation-induced metabolic reprogramming and limit terminal Tex cell accumulation in tumors (Gu et al., 2021). Inhibition of glucose metabolism also restrains expression of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 that supports the polyfunctionality and survival of intratumoral T cells (Zhao et al., 2016). Defects in aerobic glycolysis may induce metabolic dysfunction by limiting PI3K–Akt–mTOR signaling (Xu et al., 2021b). How PI3K–Akt–mTOR signaling shapes intratumoral T cell functionality remains an important topic, given its essential role in tuning anabolic metabolism. Toward that end, acylglycerol kinase (AGK) binds and phosphorylates PTEN, which antagonizes PI3K, to promote downstream glycolytic metabolism for improved antitumor immunity (Hu et al., 2019). Thus, multiple mechanisms contribute to defects in glucose metabolism in T cells from the TME.

While T cells have reduced glucose uptake in certain cancer models (Scharping et al., 2016), such effects are likely tumor context-specific. It was recently reported that T cells acquire more or similar amount of glucose as cancer cells, with tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells taking up the most glucose in certain TMEs (Reinfeld et al., 2021). Consequently, myeloid cells have the highest glycolytic rate, and whether myeloid-derived lactate limits T cell effector function, similar as tumor-derived lactate, remains to be explored (Brand et al., 2016; Reinfeld et al., 2021). Moreover, acute glucose restriction improves the antitumor efficacy of T cells by promoting increased flux of glucose-derived carbons into anabolic pathways when glucose is no longer limiting (Klein Geltink et al., 2020), which may also apply to other metabolites that functionally compensate for glucose to promote antitumor immunity, including inosine (Mager et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b). Thus, glucose metabolism acts as a context-dependent regulator of antitumor immunity.

Intratumoral lipids regulate functions of conventional T cells, dendritic cells (Box 1) and regulatory T (Treg) cells (Box 2) to tune antitumor immunity. In tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, cholesterol uptake activates the ER stress-associated transcription factor XBP1 and increases PD-1 expression (Ma et al., 2019b). PD-1 ligation in the TME may further lead to altered mitochondrial or lipid metabolism in tumor-infiltrating T cells (Bengsch et al., 2016; Patsoukis et al., 2015). Similarly, fatty acids or oxidized lipids are taken up by CD36-expressing CD8+ T cells, thereby triggering lipid peroxidation that induces both ferroptosis and p38 kinase-driven Tex cell programming to limit their antitumor function (Ma et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021c). However, certain lipids, like cholesterol, play an important role in tuning TCR signaling (Wang et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016b), and deletion of acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 (ACAT1), an enzyme that promotes cholesterol esterification, potentiates the antitumor function of CD8+ T cells by increasing TCR clustering and signaling (Yang et al., 2016b), suggesting complex regulation of antitumor immunity by lipids.

Box 1. Cellular metabolism of dendritic cells in the TME.

Dendritic cells (DCs) prime T cell-mediated immune responses for proper induction of antitumor immunity. Metabolic reprogramming is associated with DC maturation, with glycolysis and OXPHOS playing critical roles in this process to facilitate T cell activation for antitumor immunity (Giovanelli et al., 2019). How metabolism orchestrates DC function in the TME is being explored. Oxidized lipids suppress cross presentation in DCs (Ramakrishnan et al., 2014; Veglia et al., 2017). Moreover, tumor-derived DCs express high amount of lipid scavenger receptor A that promotes uptake of extracellular fatty acids (Herber et al., 2010). In turn, peroxidation of these lipids activates XBP1, which triggers dysfunctional synthesis and an accumulation of lipids in DCs that are associated reduced DC function and antitumor immunity (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015; Herber et al., 2010). In addition, the conditional deletion of Mst1 and Mst2 in DCs reduces antitumor immunity. Further, conventional DC 1 (cDC1), but not cDC2, cells that lack Mst1 and Mst2 contain mitochondria with disorganized cristae and have reduced expression of OPA1, a protein that promotes mitochondrial fusion (Du et al., 2018), suggesting a crucial role for mitochondrial dynamics in DC subsets for the establishment of T cell-mediated immunity to tumors. Dysregulated lipid signaling and mitochondrial dynamics also directly impact CD8+ T cell function (Buck et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2019b; Yu et al., 2020), suggesting that metabolism shapes the functional interplay between DCs and T cells in the TME. How the TME regulates metabolism in DC subsets, including those with anti-inflammatory properties, and the metabolic pathways that underlie DC function in different disease contexts, require further investigation.

Box 2. Metabolic adaptation of intratumoral Treg cells.

Although crucial for immune tolerance, Treg cells represent a major barrier to antitumor immunity (Savage et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2017). Treg cells undergo metabolic reprogramming upon activation, with mitochondrial metabolism and autophagy being essential for Treg cell function under homeostasis and in the TME (Chapman et al., 2018; Field et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2019; Saravia et al., 2020; Su et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2016; Weinberg et al., 2019). Mitochondrial metabolism and fitness in intratumoral Treg cells are supported by extracellular lactate or fatty acids, and Treg cell-specific deletion of the lactate transporter MCT1 or fatty-acid transporter CD36 provokes robust antitumor responses (Kumagai et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2020a; Watson et al., 2021). In contrast, glucose metabolism suppresses Treg cell function in the TME, in part by impinging upon their stability (Watson et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2016; Zappasodi et al., 2021); however, activated Treg cells upregulate glycolysis, which may regulate Treg cell trafficking to or within tumors (Kishore et al., 2017). Ligation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on intratumoral Treg cells suppresses glycolytic flux and may therefore divert their dependence to other nutrient sources (Zappasodi et al., 2021). PD-1 is also expressed on intratumoral Treg cells (Kumagai et al., 2020a; Lim et al., 2021) and is implicated in limiting glucose metabolism in Treg cells (Tan et al., 2021). Mechanistically, PD-1 expression on intratumoral Treg cells requires the SCAP–SREBP-dependent upregulation of HMGCR, which promotes mevalonate metabolism-dependent protein geranylgeranylation to orchestrate Treg cell function in the TME (Lim et al., 2021). Moreover, SCAP–SREBP signaling promotes FASN expression, which is crucial to maintain the function of activated Treg cells, such as those found in the TME (Lim et al., 2021). Thus, metabolism orchestrates intratumoral Treg cell function.

Besides glucose and lipids, other nutrients, metabolites, and minerals also modulate the metabolic state of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Tumor cells have higher expression of the methionine transporter Slc43a2, thereby limiting methionine metabolism and the antitumor function of T cells (Bian et al., 2020). Additionally, cancer cells acquire more intratumoral glutamine than T cells, and blockade of glutamine uptake leads to greater glucose acquisition by T cells and other cells in the TME, associated with enhanced T cell infiltration into the tumor (Reinfeld et al., 2021). Similar potentiating effects on antitumor immunity are observed upon inhibition of glutaminolysis in the TME (Leone et al., 2019), or upon transient inhibition of glutaminolysis in CAR T cells (Johnson et al., 2018). Extracellular potassium is elevated in the TME and promotes stem-like programs in T cells, associated with long-term persistence; consequently, potassium-treated T cells have better antitumor immunity (Vodnala et al., 2019). Thus, extracellular nutrients, metabolites, and minerals tune intratumoral T cell responses.

Intracellular metabolites are also emerging as crucial regulators of metabolic reprogramming and antitumor immunity in the TME. For example, enforced expression of the BH4 synthetic enzyme GCH1 improves the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells (Cronin et al., 2018), suggesting that BH4 synthesis is a limiting factor for intratumoral T cell function. CD8+ T cells produce the mitochondrial metabolites S-2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) and R-2-HG, with S-2-HG being produced at higher concentration and whose supplementation improves the proliferation, survival and antitumor function of T cells (Tyrakis et al., 2016). However, tumors with mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1, an enzyme of the TCA cycle, hyperproduce R-2-HG, which impairs the functionality of tumor-infiltrating T cells (Bunse et al., 2018). IL-2 stimulation induces T cells to produce the tryptophan catabolite, 5-hydroxytrypotphan, which limits antitumor immunity by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) transcriptional activity that promotes Tex cell-associated programming (Liu et al., 2021c). Tumor-derived tryptophan catabolites like kynurenic acid also activate AhR and may therefore have similar effects on T cell responses (Sadik et al., 2020). How the TME shapes production of these intracellular metabolites by T cells requires additional studies.

T cells in the TME acquire Tex cell features (Collier et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2018), with alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis, membrane potential, and ROS production all being associated with T cell dysfunction in the TME (Scharping et al., 2016; Scharping et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020). Improving the mitochondrial fitness of T cells increases their antitumor efficacy (Klein Geltink et al., 2020; Scharping et al., 2016; Vardhana et al., 2020; Verma et al., 2021). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the regulators of mitochondrial metabolism in intratumoral T cells. Chronic TCR triggering may suppress mitochondrial metabolism in intratumoral CD8+ T cells, as chronic antigen stimulation in vitro triggers an initial increase and subsequent progressive decline in mitochondrial metabolism (Vardhana et al., 2020). Chronic TCR stimulation induces PD-1 expression that may also reprogram mitochondrial or glucose metabolism in intratumoral T cells (Bengsch et al., 2016; Patsoukis et al., 2015). Defects in PGC-1α expression also dampen mitochondrial biogenesis in the TME, with PGC-1α overexpression improving the antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells (Scharping et al., 2016). In addition, the ribonuclease Regnase-1 inhibits mitochondrial metabolism in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells via its ability to antagonize the expression and function of the transcription factor BATF (Wei et al., 2019), and possibly IRF4 that frequently cooperates with BATF in mediating T cell effector function (Jeltsch et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2021). Accordingly, Regnase-1 deletion improves the accumulation and effector function of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells, including CAR T cells (Wei et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2021). Loss of Regnase-1 also reduces exhaustion-associated programs in TCF-1− CAR T cells, and leads to expansion of TCF-1+ Tpex cells, with TCF-1 being a direct target of Regnase-1 (Zheng et al., 2021). Finally, administration of IL-10-Fc fusion protein increases OXPHOS in terminal Tex cells, as well as their expansion and cytotoxicity; further, IL-10-Fc administration synergizes with adoptive cell therapy for enhanced antitumor therapy (Guo et al., 2021b). Identifying TME-specific regulators of metabolism therefore has strong clinical potentials for improving adoptive cell therapy for cancer.

Metabolic dysfunction in lymphocytes promotes malignant transformation

One of the hallmarks for cancer development is dysregulated metabolism (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Altered lymphocyte metabolism influences malignant transformation and the development of hematological tumors. For instance, the protein phosphatase PP2A protects B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) cells from oxidative stress to preserve their survival. Mechanistically, PP2A signaling redirects glucose utilization toward the PPP in B-ALL cells, although elevated PI3K–Akt–mTOR signaling also contributes to these effects (Xiao et al., 2018). Aberrant PI3K–Akt–mTOR signaling that is induced by deletion or mutation of regulatory proteins PTEN and RagC is also associated with the development of other hematological malignancies (Hagenbeek and Spits, 2008; Okosun et al., 2016; Suzuki et al., 2001). T cell leukemogenesis driven by PTEN deletion is rectified upon inhibition of protein O-GlcNAcylation; this posttranslational modification is induced downstream of glucose and glutamine metabolism to further control metabolic reprogramming mediated by the transcription factor MYC (Swamy et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011). Moreover, MYC-dependent development of B cell lymphoma requires mTORC1 (Zeng et al., 2018). However, MYC also induces expression of TSC1, a key inhibitor of mTORC1 signaling, to promote the maintenance of Burkitt’s lymphoma cells (Hartleben et al., 2018), suggesting a complex interplay between MYC, mTORC1 and metabolism in B cell-associated cancers. Finally, metabolic regulation also contributes to the fitness of metastatic hematological malignancies, as ALL cells upregulate stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) expression and fatty acid synthesis, which is important for ALL cell accumulation in the central nervous system (Savino et al., 2020). Together, these studies support key roles for anabolic pathways in driving the development or progression of hematological cancers.

Excessive immune activation may also elicit uncontrolled, tumor-permissive inflammation (Greten and Grivennikov, 2019), and emerging studies demonstrate that dysregulated lymphocyte metabolism also contributes to solid tumor formation. Indeed, T cell-specific deletion of liver kinase B1 (LKB1), another crucial regulator of T cell metabolism, drives intestinal polyp formation, a risk factor for intestinal tumorigenesis (MacIver et al., 2011; Poffenberger et al., 2018). Further, oxygen sensing by the prolyl hydroxylase domain containing proteins (called PHDs) is essential for T cells to curtail the spontaneous formation of pulmonary tumors, by repressing HIF-1α-induced glycolytic programming that supports the differentiation of Th1 or cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Clever et al., 2016). Uncovering the metabolic drivers that distinguish physiological lymphocyte activation versus malignant transformation or tumor progression provides additional opportunities to target metabolism for cancer therapy.

Immunometabolism in human infection, autoimmunity, and cancer

Targeting immunometabolism is a promising strategy for the treatment of human disease. While metabolic networks that drive lymphocyte activation are likely conserved, mouse and human systems may also differ in their metabolic requirements, as evidenced by the different roles of aerobic glycolysis for inducing murine and human Treg cells in vitro (Clever et al., 2016; De Rosa et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013a). Thus, there remains a need to better understand context-dependent regulation of human lymphocyte metabolism. We summarize below recent studies that have characterized the metabolic state of human lymphocytes in infection, autoimmunity, and cancer (Figure 2).

Chronic infection in humans is associated with altered T cell responses (Collier et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2018), as well as rewired lymphocyte metabolism. CD4+ T cells with higher rates of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and OXPHOS are more susceptible to infection by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Clerc et al., 2019; Valle-Casuso et al., 2019). Further, GLUT1 expression is increased on CD4+ T cells from HIV patients, thus enforcing aerobic glycolysis that sustains viral replication (Guo et al., 2021a; Palmer et al., 2014; Valle-Casuso et al., 2019). Certain HIV-infected individuals spontaneously control viral load without antiretroviral therapy. In such cases, HIV-specific CD8+ Tcm cells with enhanced functionality accumulate, associated with greater acquisition of extracellular fatty acids relative to glucose, thereby endowing them with metabolic plasticity upon glucose deprivation. In contrast, patients who control viral load while on antiretroviral therapy retain the requirement for glucose utilization and show reduced accumulation of functional HIV-specific Tcm cells (Angin et al., 2019). Whether altered glucose metabolism in T cells contributes to improved control of HIV remains to be tested.

In addition, OXPHOS is upregulated in CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals, which is mediated by NLRX1, a mitochondria-associated protein that binds FASTKD5. NLRX1 and FASTKD5 are essential to promote the expression and assembly of the electron transport chain that supports OXPHOS and viral replication (Clerc et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2021a; Valle-Casuso et al., 2019). Glutaminolysis primarily supports OXPHOS for early viral replication in naïve and memory CD4+ T cells, although glucose-derived carbons also contribute to this process when pyruvate conversion to lactate is reduced (Clerc et al., 2019). CD8+ Tcm cells from spontaneous HIV controllers also require mitochondrial activity for their enhanced function. However, mitochondrial mass is moderately downregulated in CD8+ Tcm cells from spontaneous HIV controllers relative to those on antiretroviral therapy, and increased mitochondrial mass is associated with acquisition of senescent-like or exhausted phenotype in hepatitis B virus-specific CD8+ T cells (Angin et al., 2019; Henson et al., 2014; Schurich et al., 2016), suggesting complex regulation of mitochondrial metabolism in chronic infection. It will be important to determine the extent of which antigen load, inflammatory status, and activation state influence T cell metabolism in HIV and other chronic infections.

Metabolic alterations in lymphocytes are also observed in COVID-19 relative to other infections or pulmonary inflammatory conditions. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-reactive CD8+ T cells show lower expression of glycolysis-related genes as compared with influenza- or respiratory syncytial virus-specific cells, associated with reduced CD8+ T cell polyfunctionality (Kusnadi et al., 2021). Moreover, certain T cell subsets from COVID-19 patients accumulate depolarized mitochondria and have reduced fatty acid uptake during acute infection, associated with altered cellularity of all CD8+ T cell subsets and CD4+ Tcm cells. Further, activation-induced metabolic reprogramming is impaired in CD8+, and to a lesser extent CD4+, T cells from COVID-19 patients with acute infection compared to healthy individuals (Liu et al., 2021b). In addition, a distinct T cell subset marked by high expression of voltage-dependent ion channel 1 (VDAC1) and histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 (called H3K27me3hiVDAC1hi cells) are expanded in patients with acute COVID-19 (Thompson et al., 2021). H3K27me3hiVDAC1hi cells contain mitochondria with disorganized cristae and have increased cytochrome c release that can trigger apoptotic cell death, while VDAC1 inhibition blocks these events. Of note, GLUT1 expression on H3K27me3hiVDAC1hi cells is negatively associated with COVID-19 disease severity. The functional effects of the metabolic alterations observed in COVID-19 warrant further investigation.

Systemic metabolic alterations also occur in patients with COVID-19. Proteomic profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals reductions of glycogenolysis, galactose degradation, and glycolysis, but increases in OXPHOS and FAO that contribute to excessive ROS generation in several tissues. In the lung and spleen, there are corresponding reductions of T and B cells and altered immune signaling (Nie et al., 2021). Serum amino acids or their metabolites are also altered, including a pronounced reduction of arginine metabolites (Shen et al., 2020), thereby possibly impeding appropriate Teff or Tmem responses (Geiger et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2021b). Serological analysis of proteins in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with pulmonary disease also shows that glycosaminoglycan metabolism is upregulated as compared with patients with other forms of pulmonary disease; the changes are associated with reductions of memory B and CD8+ Tem cells and an accumulation of effector-like CD8+ T cell populations (Arthur et al., 2021). Future studies are needed to determine whether systemic or organ-specific metabolic alterations following SARS-CoV-2 infection contribute to adaptive immunity or disease severity.

In addition to infection, lymphocytes from patients with autoimmune disease display dysregulated metabolism. Although T cell-intrinsic glucose metabolism drives EAE (Karmaus et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2021a), T cells from patients with multiple sclerosis have defects in glycolysis (De Rosa et al., 2015). Defective glycolysis is also evident in T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (called RA T cells hereafter), which is attributed to reduced activation-induced expression of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphase 3 (PFKFB3). This reduction diverts glucose metabolism to the PPP and renders these cells more susceptible to apoptosis (Yang et al., 2013b). Additionally, dysregulated PFKFB3 function induces RA T cells to express high amount of TKS5, a scaffolding protein that promotes the invasiveness of RA T cells into non-lymphoid tissues (Shen et al., 2017). Also, naïve RA T cells have reduced expression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, which contributes to glucose shuttling into the PPP. These effects are associated with increased consumption of ROS that promotes hyperproliferation, elevated differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells, and synovial inflammation (Yang et al., 2016c). Moreover, in the inflamed synovial tissue of RA patients, accumulation and uptake of lactate by CD4+ T cells impair glycolysis and increase fatty acid synthesis, associated with increased retention and pathogenicity of T cells (Pucino et al., 2019). Thus, T cells from autoimmune patients show altered glucose metabolism.

RA T cells also have decreased expression of the mitochondrial DNA repair protein MRE11A and generate less mitochondria-derived ATP and ROS production (Li et al., 2019c). Moreover, the TCA cycle is disrupted, associated with the accumulation of citrate and acetyl-CoA over succinate, with acetyl-CoA-dependent protein acetylation also contributing to tissue invasion and damage (Wu et al., 2020a). The preference of glucose flux into the PPP for the generation of NADPH, and the accumulation of citrate, also promote increased lipid synthesis that leads to the formation of lipid droplets in RA T cells (Shen et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020a). Collectively, these studies reveal metabolic alterations in T cells from patients with autoimmune disease, some of which are disease- or location-specific. It is important to determine whether metabolic changes in human T cells are a driver, or a consequence of, autoimmune inflammation.

Dysregulated metabolism in human lymphocytes is also associated with cancers. CD8+ T cells that infiltrate clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) have impaired glucose uptake and glycolytic flux. Furthermore, mitochondrial fitness is impaired in both tumor-infiltrating and circulatory CD8+ T cells from patients with ccRCC, associated with an accumulation of fragmented, hyperpolarized mitochondria that produce excessive ROS (Siska et al., 2017). Mitochondrial content and glucose uptake are also decreased in tumor-infiltrating relative to circulatory CD8+ T cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (Scharping et al., 2016). Also, T cell infiltration in HNSCC and other squamous cell carcinomas is impaired, accompanied by increased glucose consumption by tumor cells (Ottensmeier et al., 2016). Moreover, CD8+ T cells exposed to the ascites of ovarian cancer upregulate XBP1 expression, associated with reduced glucose or glutamine uptake, mitochondrial activity, and antitumor function (Song et al., 2018). Thus, dysregulated glucose and mitochondrial metabolism are characteristic of intratumoral T cells.

Metabolites also regulate T cell function in the TME. Consistent with this notion, pyruvate supplementation or treatment with ROS scavengers partially restores ccRCC-derived CD8+ T cell function (Siska et al., 2017). In addition, metabolites produced within the TME modulate T cell function. First, myeloid-derived suppressor cells produce methylglyoxal, which inhibits T cell function (Baumann et al., 2020). Second, the metabolite 1-methylnicotinamine (MNA) that is likely derived from tumors accumulates in intratumoral T cells from patients with ovarian cancer. Moreover, MNA promotes TNF-α but reduces IFN-γ production by T cells, and limits their antitumor activity in vitro (Kilgour et al., 2021). Third, hepatocellular carcinoma cells produce high amounts of methionine metabolites that can promote Tex programming and impair antitumor responses (Hung et al., 2021). Therefore, metabolic profiling of the TME, including in T cells, offers a means to identify context-dependent regulators of lymphocyte function in the TME.

Metabolic reprogramming is also likely a driver of T cell fate in the TME. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from patients with breast cancer or melanoma accumulate lipid droplets and cholesterol esters, which induce senescence in these cells (Liu et al., 2021a). Moreover, a subset of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells from colorectal carcinoma patients have defective expression of enzymes related to mitochondrial and glutamine metabolism, which is associated with the acquisition of terminal exhaustion-related features, including high expression of PD-1 and CD39 and low expression of TCF-1 (Hartmann et al., 2021). In addition, a population that co-expresses PD-1, CD39, and TCF-1 (likely representing a Tpex population (Collier et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2018)) and is characterized by higher metabolic activity is also present in the TME. Such changes in metabolic state are associated with the distribution of CD8+ T cells in discrete regions near the tumor–immune border (Keren et al., 2018), with metabolic activity decreasing in PD-1- and CD39-expressing cells as their distance from tumor–immune border increases (Hartmann et al., 2021). It remains uncertain whether the spatial organization of lymphocytes in the TME contributes to altered metabolic and functional features.

Concluding remarks

Metabolism has emerged as a key driver of lymphocyte fate and function in vivo, with T cells and B cells displaying extensive plasticity and adaptability to metabolic perturbations that they encounter in the contexts of infection, inflammation, and cancer. How metabolism is rewired, and the immunological and physiological consequences of such reprogramming, are being actively investigated in murine models of these immunological conditions, with many of the observed effects extending to human patients with infections, autoimmune diseases, or cancer. These investigations, in conjunction with advances on metabolic profiling approaches, have revealed both conserved and context-dependent metabolic programs that facilitate the differentiation and functional fitness of lymphocyte populations in discrete microenvironments or inflammatory contexts. These exciting findings will accelerate the application of targeting metabolic pathways for immune modulation in human disease.

Several areas remain underexplored but will be critical for understanding the mechanisms, drivers, and clinical translation of context-dependent metabolic reprogramming. First, the mechanisms that dictate the metabolism-driven effects on specific cellular responses in different diseases, across time and in specific locations, will be important to explore. These mechanisms include the distinct upstream immunological, nutrient, or growth factor signals that drive metabolic reprogramming in different contexts, and how immunometabolism functionally interplays with intracellular signaling to enforce its functional effects (Chapman et al., 2020). Toward that end, single cell profiling combined with in-depth bioinformatic analyses will help to uncover the immunometabolic regulatory networks in different contexts (Karmaus et al., 2019; Wagner et al., 2021). Second, while an active area of investigation in the context of tumor–immune cell interactions (Chang et al., 2015; Leone et al., 2019; Reinfeld et al., 2021), how intercellular signaling processes involving metabolites and nutrients mediate metabolic adaptation, lymphocyte fate, and disease outcome are important to address in various physiological and pathological conditions, including spatial resolution of such communication within tissues. Third, nutritional state influences lymphocyte fate and function in different disease contexts (Collins et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2021b; Huang et al., 2021c; Roy et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019), so dietary metabolic intervention or perturbation of systemic metabolism may aid in resolving aberrant inflammatory responses or improving the efficacy of vaccines or adoptive cell therapies. Finally, the application of different profiling and computational analyses combined with functional screening approaches will be instrumental in establishing the metabolism-associated transporters, transducers, and effectors that orchestrate context-specific lymphocyte fate and function (Long et al., 2021). Collectively, these future investigations will likely identify actionable targets in immunometabolism to improve therapeutic intervention of human disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge H. Huang, J. Raynor, J. Saravia, and H. Shi for critical reading or editing of the manuscript. This work was supported by ALSAC and NIH grants AI105887, AI131703, AI140761, AI150241, AI150514, and CA253188 (to H.C.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests

H.C. is a consultant for Kumquat Biosciences.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angin M, Volant S, Passaes C, Lecuroux C, Monceaux V, Dillies MA, Valle-Casuso JC, Pancino G, Vaslin B, Le Grand R, et al. (2019). Metabolic plasticity of HIV-specific CD8(+) T cells is associated with enhanced antiviral potential and natural control of HIV-1 infection. Nat Metab 1, 704–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, and Ahmed R (2009). mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature 460, 108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo L, Khim P, Mkhikian H, Mortales CL, and Demetriou M (2017). Glycolysis and glutaminolysis cooperatively control T cell function by limiting metabolite supply to N-glycosylation. Elife 6, e21330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur L, Esaulova E, Mogilenko DA, Tsurinov P, Burdess S, Laha A, Presti R, Goetz B, Watson MA, Goss CW, et al. (2021). Cellular and plasma proteomic determinants of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pulmonary diseases relative to healthy aging. Nature Aging 1, 535–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachem A, Makhlouf C, Binger KJ, de Souza DP, Tull D, Hochheiser K, Whitney PG, Fernandez-Ruiz D, Dahling S, Kastenmuller W, et al. (2019). Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Promote the Memory Potential of Antigen-Activated CD8(+) T Cells. Immunity 51, 285–297 e285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis W, Shyer JA, Zhao J, Canaveras JCG, Al Khazal FJ, Qu R, Steach HR, Bielecki P, Khan O, Jackson R, et al. (2019). Distinct modes of mitochondrial metabolism uncouple T cell differentiation and function. Nature 571, 403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer ML, Ma EH, Bantug GR, Grahlert J, Pfister S, Glatter T, Jauch A, Dimeloe S, Slack E, Dehio P, et al. (2016). Memory CD8(+) T Cells Require Increased Concentrations of Acetate Induced by Stress for Optimal Function. Immunity 44, 1312–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer ML, Ma EH, Thompson AJ, Epple R, Unterstab G, Lotscher J, Dehio P, Schurch CM, Warncke JD, Perrin G, et al. (2020). Memory CD8(+) T Cells Balance Pro- and Anti-inflammatory Activity by Reprogramming Cellular Acetate Handling at Sites of Infection. Cell Metab 32, 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann T, Dunkel A, Schmid C, Schmitt S, Hiltensperger M, Lohr K, Laketa V, Donakonda S, Ahting U, Lorenz-Depiereux B, et al. (2020). Regulatory myeloid cells paralyze T cells through cell-cell transfer of the metabolite methylglyoxal. Nat Immunol 21, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, Stelekati E, McLane LM, Paley MA, Delgoffe GM, and Wherry EJ (2016). Bioenergetic Insufficiencies Due to Metabolic Alterations Regulated by the Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Are an Early Driver of CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity 45, 358–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, Freitag J, Hagemann S, Harmrolfs K, Sandouk A, Hesse C, Castro CN, Bahre H, et al. (2014). De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med 20, 1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Li W, Kremer DM, Sajjakulnukit P, Li S, Crespo J, Nwosu ZC, Zhang L, Czerwonka A, Pawlowska A, et al. (2020). Cancer SLC43A2 alters T cell methionine metabolism and histone methylation. Nature 585, 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby M, and Rickert RC (2017). Metabolic Regulation of the Immune Humoral Response. Immunity 46, 743–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges da Silva H, Beura LK, Wang H, Hanse EA, Gore R, Scott MC, Walsh DA, Block KE, Fonseca R, Yan Y, et al. (2018). The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long-lived memory CD8(+) T cells. Nature 559, 264–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges da Silva H, Peng C, Wang H, Wanhainen KM, Ma C, Lopez S, Khoruts A, Zhang N, and Jameson SC (2020). Sensing of ATP via the Purinergic Receptor P2RX7 Promotes CD8(+) Trm Cell Generation by Enhancing Their Sensitivity to the Cytokine TGF-beta. Immunity 53, 158–171 e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M, Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et al. (2016). LDHA-Associated Lactic Acid Production Blunts Tumor Immunosurveillance by T and NK Cells. Cell Metab 24, 657–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Klein Geltink RI, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Sanin DE, Qiu J, Kretz O, Braas D, van der Windt GJ, et al. (2016). Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell 166, 63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunse L, Pusch S, Bunse T, Sahm F, Sanghvi K, Friedrich M, Alansary D, Sonner JK, Green E, Deumelandt K, et al. (2018). Suppression of antitumor T cell immunity by the oncometabolite (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate. Nat Med 24, 1192–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campello S, Lacalle RA, Bettella M, Manes S, Scorrano L, and Viola A (2006). Orchestration of lymphocyte chemotaxis by mitochondrial dynamics. J Exp Med 203, 2879–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro-Maldonado A, Wang R, Nichols AG, Kuraoka M, Milasta S, Sun LD, Gavin AL, Abel ED, Kelsoe G, Green DR, and Rathmell JC (2014). Metabolic reprogramming is required for antibody production that is suppressed in anergic but exaggerated in chronically BAFF-exposed B cells. J Immunol 192, 3626–3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EL, Kelman A, Wu GS, Gopaul R, Senkevitch E, Aghvanyan A, Turay AM, and Frauwirth KA (2010). Glutamine uptake and metabolism are coordinately regulated by ERK/MAPK during T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol 185, 1037–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr., Faubert B, Villarino AV, O’Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J, et al. (2013). Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 153, 1239–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ, et al. (2015). Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 162, 1229–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman NM, Boothby MR, and Chi H (2020). Metabolic coordination of T cell quiescence and activation. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman NM, Zeng H, Nguyen TM, Wang Y, Vogel P, Dhungana Y, Liu X, Neale G, Locasale JW, and Chi H (2018). mTOR coordinates transcriptional programs and mitochondrial metabolism of activated Treg subsets to protect tissue homeostasis. Nat Commun 9, 2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SC, Titov AA, Abboud G, Seay HR, Brusko TM, Roopenian DC, Salek-Ardakani S, and Morel L (2018). Inhibition of glucose metabolism selectively targets autoreactive follicular helper T cells. Nat Commun 9, 4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc I, Moussa DA, Vahlas Z, Tardito S, Oburoglu L, Hope TJ, Sitbon M, Dardalhon V, Mongellaz C, and Taylor N (2019). Entry of glucose- and glutamine-derived carbons into the citric acid cycle supports early steps of HIV-1 infection in CD4 T cells. Nat Metab 1, 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever D, Roychoudhuri R, Constantinides MG, Askenase MH, Sukumar M, Klebanoff CA, Eil RL, Hickman HD, Yu Z, Pan JH, et al. (2016). Oxygen Sensing by T Cells Establishes an Immunologically Tolerant Metastatic Niche. Cell 166, 1117–1131 e1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JL, Weiss SA, Pauken KE, Sen DR, and Sharpe AH (2021). Not-so-opposite ends of the spectrum: CD8(+) T cell dysfunction across chronic infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 22, 809–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N, Han SJ, Enamorado M, Link VM, Huang B, Moseman EA, Kishton RJ, Shannon JP, Dixit D, Schwab SR, et al. (2019). The Bone Marrow Protects and Optimizes Immunological Memory during Dietary Restriction. Cell 178, 1088–1101 e1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado M, Edwards-Hicks J, Villa M, Flachsmann LJ, Sanin DE, Jacobs M, Baixauli F, Stanczak M, Anderson E, Azuma M, et al. (2020). Dynamic Cardiolipin Synthesis Is Required for CD8(+) T Cell Immunity. Cell Metab 32, 981–995 e987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin SJF, Seehus C, Weidinger A, Talbot S, Reissig S, Seifert M, Pierson Y, McNeill E, Longhi MS, Turnes BL, et al. (2018). The metabolite BH4 controls T cell proliferation in autoimmunity and cancer. Nature 563, 564–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty S (2019). T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity 50, 1132–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Silberman PC, Rutkowski MR, Chopra S, Perales-Puchalt A, Song M, Zhang S, Bettigole SE, Gupta D, Holcomb K, et al. (2015). ER Stress Sensor XBP1 Controls Anti-tumor Immunity by Disrupting Dendritic Cell Homeostasis. Cell 161, 1527–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Staron MM, Gray SM, Ho PC, Amezquita RA, Wu J, and Kaech SM (2015). IL-7-Induced Glycerol Transport and TAG Synthesis Promotes Memory CD8+ T Cell Longevity. Cell 161, 750–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y, Bordman Z, Fu J, Kim Y, Yen HR, et al. (2011). Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell 146, 772–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa V, Galgani M, Porcellini A, Colamatteo A, Santopaolo M, Zuchegna C, Romano A, De Simone S, Procaccini C, La Rocca C, et al. (2015). Glycolysis controls the induction of human regulatory T cells by modulating the expression of FOXP3 exon 2 splicing variants. Nat Immunol 16, 1174–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MH, Wang X, Zhang X, Chou C, Nixon BG, Capistrano KJ, Peng M, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM, and Li MO (2020). Nutrient mTORC1 signaling underpins regulatory T cell control of immune tolerance. J Exp Med 217, e20190848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Wen J, Wang Y, Karmaus PWF, Khatamian A, Tan H, Li Y, Guy C, Nguyen TM, Dhungana Y, et al. (2018). Hippo/Mst signalling couples metabolic state and immune function of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. Nature 558, 141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek M, Pfister D, Donakonda S, Filpe P, Schneider A, Laschinger M, Hartmann D, Huser N, Meiser P, Bayerl F, et al. (2021). Auto-aggressive CXCR6(+) CD8 T cells cause liver immune pathology in NASH. Nature 592, 444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Asou HK, Matsugae N, Hirahara K, Shinoda K, Tumes DJ, Tokuyama H, Yokote K, and Nakayama T (2015). Obesity Drives Th17 Cell Differentiation by Inducing the Lipid Metabolic Kinase, ACC1. Cell Rep 12, 1042–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Onodera A, Obata-Ninomiya K, Koyama-Nasu R, Asou HK, Ito T, Yamamoto T, Kanno T, Nakajima T, Ishiwata K, et al. (2019). ACC1 determines memory potential of individual CD4(+) T cells by regulating de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. Nat Metab 1, 261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersching J, Efeyan A, Mesin L, Jacobsen JT, Pasqual G, Grabiner BC, Dominguez-Sola D, Sabatini DM, and Victora GD (2017). Germinal Center Selection and Affinity Maturation Require Dynamic Regulation of mTORC1 Kinase. Immunity 46, 1045–1058 e1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CS, Baixauli F, Kyle RL, Puleston DJ, Cameron AM, Sanin DE, Hippen KL, Loschi M, Thangavelu G, Corrado M, et al. (2020). Mitochondrial Integrity Regulated by Lipid Metabolism Is a Cell-Intrinsic Checkpoint for Treg Suppressive Function. Cell Metab 31, 422–437 e425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]