Abstract

Iron is an essential micronutrient for all bacteria but presents a significant challenge given its limited bioavailability. Furthermore, iron’s toxicity combined with the need to maintain iron levels within a narrow physiological range requires integrated systems to sense, regulate and transport a variety of iron complexes. Most bacteria encode systems to chelate and transport ferric iron (Fe3+) via siderophore receptor mediated uptake or via cytoplasmic energy dependent transport systems. Pathogenic bacteria have further lowered the barrier to iron acquisition by employing systems to utilize haem as a source of iron. Haem, a lipophilic and toxic molecule, presents a significant challenge for transport into the cell. As such pathogenic bacteria have evolved sophisticated cell surface signaling (CSS) and transport systems to sense and obtain haem from the host. Once internalized haem is cleaved by both oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms to release iron. Herein we summarize our current understanding of the mechanism of haem sensing, uptake and utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, its role in pathogenesis and virulence, and the potential of these systems as antimicrobial targets.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, haem uptake and utilization, biliverdin, iron homeostasis, transcriptional regulation, ECF σ-factor systems, iron and haem regulated sRNAs, bacterial pathogenesis

1. INTRODUCTION

Iron due to its versatile coordination and tunable redox catalyzes a number of chemical reactions required for life in an oxygen environment. Iron is found as a cofactor in proteins whose functions range from dioxygen transport, energy transduction, to nitrogen and hydrogen fixation (Dlouhy & Outten, 2013). Although iron is the fourth most abundant metal on earth, it is not readily bioavailable at neutral pH due to its rapid oxidation to insoluble iron (II/III) oxides haematite (Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4). In contrast the fully reduced Fe2+ state is more soluble, but it can promote the generation of toxic oxygen species (ROS) through Fenton chemistry. Such ROS are particularly damaging to membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. For bacterial pathogens, iron is a significant limiting factor for colonization and infection of the host (Becker & Skaar, 2014). Bacterial pathogens face a significant challenge in accessing iron within a host as it is sequestered in high affinity binding proteins such as transferrin, ferritin, lactoferrin or chelated in haem which represents greater than 75% of the total body iron (Becker & Skaar, 2014; Otto, Verweij-van Vught, & MacLaren, 1992). Moreover, as a first line defense the host further restricts iron from the invading bacteria, a process known as nutritional immunity (Barber & Elde, 2014). This initial innate immune response is facilitated by the combined action of the key regulators of iron homeostasis, hepcidin and ferroportin (Schmidt, 2015). Moreover, secretion of lipocalin-2 (also known as siderocalin or neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein, NGAL) can directly bind and sequester iron away from the invading bacteria (Clifton, Corrent, & Strong, 2009; Sia, Allred, & Raymond, 2013). Additionally, iron transporters such as the natural resistance-associated protein (Nramp1) and Nramp-2 (also referred to as divalent metal transporter DMT-1) expressed on the surface of monocytes and macrophages further sequester iron from the invading bacteria (Wessling-Resnick, 2015). In response to this limited iron and haem availability bacterial pathogens have evolved high affinity iron-siderophore and haem acquisition systems to compete for tightly bound iron (O'Neill & Wilks, 2013a; Payne, Mey, & Wyckoff, 2016; Sheldon & Heinrichs, 2015; Smith & Wilks, 2012).

2. PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA AND THE HOST-PATHOGEN INTERFACE.

P. aeruginosa is a ubiquitous Gram negative bacteria often encountered by healthy individuals but readily cleared by the host immune defenses. However, for immune compromised individuals P. aeruginosa is a serious opportunistic pathogen capable of causing debilitating and often fatal chronic infections. In particular P. aeruginosa can cause chronic lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) that can persist for months and often years. Such chronic infections present a formidable challenge especially in the context of CF where such infections become resistant to antibiotic therapy. P. aeruginosa’s ability to adapt to a wide range of physiological conditions is what allows for its long term survival and persistence in patients.

P. aeruginosa infection also requires a complex array of virulence traits that are modulated through a series of regulatory pathways in response to host immune factors. As described in the previous section the initial sequestration of iron by the host is a robust trigger for the expression of several virulence traits in P. aeruginosa, not least of which is the ability to acquire iron from the host via two siderophores pyoverdine and pyochelin (reviewed in detail elsewhere (Schalk, 2008) (Cornelis, 2010)), the uptake of ferrous iron (Fe2+) by the Feo system (Hunter et al., 2013; Konings et al., 2013), or through the uptake and utilization of haem via the haem assimilation system (Has) and the Pseudomonas haem uptake (Phu) system (Ochsner, Johnson, & Vasil, 2000a; Smith & Wilks, 2015). However, iron regulation in P. aeruginosa involves integration of several environmental cues ensuring the timely expression of iron acquisition systems but also several other virulence traits. Critical to the global regulation of iron homeostasis and virulence is the Ferric uptake regulatory (Fur) protein that sits a top of this hierarchy regulating the various iron uptake systems (Cornelis, Matthijs, & Van Oeffelen, 2009; Poole & McKay, 2003) and indirectly several virulence factors including exotoxin A (ExoA), endoprotease PrpL (Wilderman et al., 2001), alkaline protease (AP), quorum sensing, and biofilm formation. The role of Fur in regulating specific virulence traits is complex, for example, regulation of ExoA (an A-B type toxin that inhibits host protein synthesis by ADP-ribosylation of host elongation factor 2) (Lamont, Beare, Ochsner, Vasil, & Vasil, 2002; Ochsner, Johnson, Lamont, Cunliffe, & Vasil, 1996; Ochsner, Vasil, & Vasil, 1995; Stintzi et al., 1999), endoprotease PrpL (Wilderman et al., 2001) and alkaline protease (AP) (Shigematsu et al., 2001), is through the pyoverdine dependent cell surface signaling (CSS) cascade which itself is regulated by Fur (Cornelis et al., 2009; Leoni, Orsi, de Lorenzo, & Visca, 2000; Ochsner et al., 1995).

Iron has also been shown to be important for biofilm formation and while the exact mechanisms are not known it is to some degree dependent on Fur (Banin, Vasil, & Greenberg, 2005; Patriquin et al., 2008). Again this may be indirect as a consequence of Fur regulation of several factors that influence biofilm formation such as the negative regulation of rhamnolipid biosynthesis, a surfactant that promotes swarming motility and inhibits biofilm formation (Glick et al., 2010). Conversely, iron positively promotes the formation of the Psl exopolysaccharide a structural component of biofilms that is also proposed to form iron channels within the biofilm (Yu, Wei, Zhao, Guo, & Ma, 2016). Interestingly, iron-deprivation upregulates production of alginate an exopolysaccharide important in mucoid biofilms associated with CF lung infections (Wiens, Vasil, Schurr, & Vasil, 2014). In addition to Fur dependent regulation, the Feo system is also regulated by a two-component regulatory system BqsSR that senses extracellular Fe2+ (Kreamer, Wilks, Marlow, Coleman, & Newman, 2012). Additionally, BqsSR is a mediator of biofilm dispersal (Dong, Zhang, An, Xu, & Zhang, 2008) and has also been shown to prevent cationic stress associated with ferrous iron uptake (Kreamer, Costa, & Newman, 2015). Therefore, iron through its integration in several virulence associated regulatory networks plays a central role in biofilm formation, maturation and dispersal.

In addition to the negative regulation of genes involved in iron uptake and virulence Fur also exerts an indirect positive regulation over several genes through its negative regulation of two-non-coding sRNAs prrF1and prrF2 (Wilderman et al., 2004). The PrrF sRNAs repress the expression of several non-essential iron containing proteins in what is often termed the “iron-sparing response”. Genes regulated by PrrF include the iron containing superoxide dismutase SodB and several iron-sulfur cluster containing enzymes involved in key metabolic pathways (Oglesby-Sherrouse & Murphy, 2013). Thus, in an iron deficient environment the limited “iron pool” is available for essential iron-containing proteins. The PrrF sRNAs have also been shown to be required for virulence although this may be an indirect consequence of an inability to regulate the iron-sparing response. However, the PrrF sRNAs have been shown to be directly required for optimal biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) a quorum sensing molecule involved in the regulation of several virulence factors (Oglesby et al., 2008).

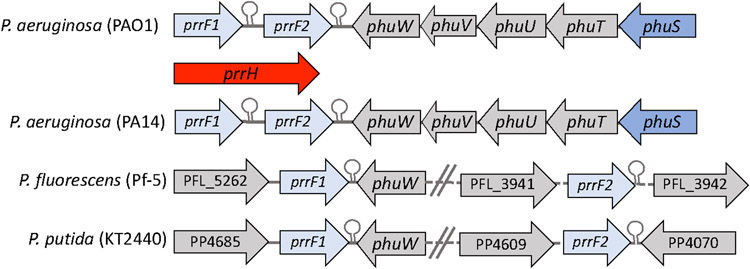

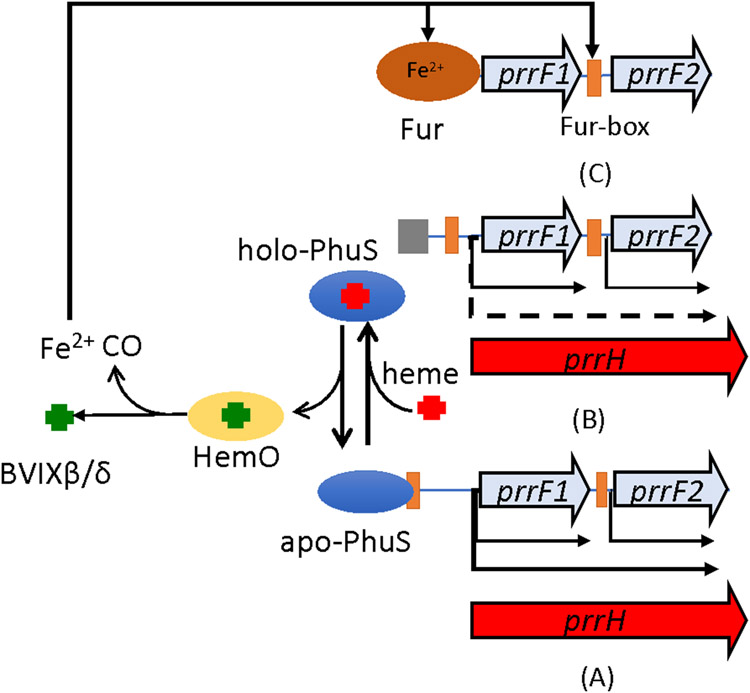

The tandem arrangement of the prrF1,F2 sRNAs provided the first insight into the link between haem utilization and its role the iron and virulence regulatory networks. This tandem arrangement of prrF1,F2 is found only in the pathogenic Pseudomonas strains and allows for a haem responsive read through of the prrF1 terminator to yield a third sRNA PrrH (Oglesby-Sherrouse & Vasil, 2010) (Fig 4). PrrH, through the unique sequence defined by the prrF1-prrF2 intergenic region is thought to regulate a subset of genes involved in haem biosynthesis (nirL, a regulator of haem d1 biosynthesis), haem uptake (phuS, a haem trafficking protein that regulates haem flux through haem oxygenase) and virulence (vreR, a CSS receptor involved in virulence gene regulation) (Reinhart et al., 2015). However, beyond the initial identification of these targets the role of PrrH role in regulating the putative targets and its overall role in pathogenesis remains to be determined.

FIGURE 4. Genetic organization of the phu and prrF1,F2 locus in pathogenic and non-pathogenic Pseudomonas strains.

PrrH sRNA obtained on read through of the prrF1 Rho-independent terminator.

Our laboratory recently identified a direct link between extracellular haem uptake and the regulation of the prrF1,F2 locus that involves the cytoplasmic haem binding protein PhuS (Wilson, Mourino, & Wilks, 2021). PhuS as will be described is section 5.3 controls the flux of haem into the cell via its specific interaction with the iron-regulated HemO (Lansky et al., 2006; O'Neill & Wilks, 2013b). However, we have further shown that in its apo-form PhuS binds to the promoter upstream of prrF1 modulating PrrF and PrrH expression and integrating haem utilization into the “iron sparing” response (Wilson et al., 2021). The role of PhuS in regulating PrrF and PrrH expression will be discussed in detail in section 4.3.

Beyond these recent findings the mechanisms by which P. aeruginosa adapts to utilize a particular iron source are not well understood despite the fact that both phenotypic and genotypic adaptation is critical for colonization and infection. Recent metabolic studies have shown P. aeruginosa in chronic lung infection decreases its reliance on pyoverdine, while increasing haem utilization (Nguyen et al., 2014). Furthermore, positive selection of mutations within the promoter of the outer membrane haem receptor phuR that lead to an increase in the utilization of haem, coincides with the loss of pyoverdine uptake (Marvig et al., 2014). We have previously shown the P. aeruginosa Has and Phu haem uptake systems have distinct functions in haem sensing and uptake, respectively (Smith & Wilks, 2015). PhuR is the major haem transporter whereas HasR primarily functions as a haem sensor via the HasS/HasI anti-σ/σ factor CSS cascade (see section 4.1). Thus, mutations that constitutively express the major haem transporter PhuR are consistent with in host adaptation toward haem utilization providing an advantage in chronic infection. In contrast recent studies of P. aeruginosa gene expression in vitro versus in vivo revealed that in an acute mouse lung infection the has operon is the most upregulated operon with the extracellular haemophore HasAp being the most upregulated protein (Damron, Barbier, Oglesby-Sherrouse, & Wilks, 2016). Similarly, this upregulation of the haem sensing system in acute infection is consistent with its role in responding and adapting to the physiological environment. However, despite these findings there is still a significant gap in our knowledge of the differential regulation of the P. aeruginosa iron and haem uptake systems and their role in virulence. For example, it remains to be determined if the HasS/HasI anti-σ/σ factor system also regulates specific virulence factors as is the case with pyoverdine dependent CSS cascade. Studies in our laboratory addressing these questions are currently underway. Furthermore, we have recently shown the P. aeruginosa specific BVIXβ isomer, generated as a consequence of haem cleavage by the iron-regulated HemO, act as positive post-transcriptional regulator of the Has system (see section 4.2). This metabolic feedback loop provides an entry point for both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of haem uptake and potentially virulence.

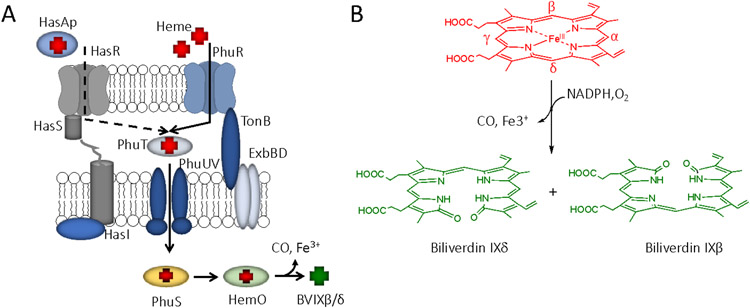

3. OVERVIEW OF HAEM UPTAKE AND UTILIZATION

Gram negative bacterial haem acquisition systems are comprised of a series of highly evolved proteins that i) sense and signal the up regulation of the haem transport systems; ii) bind haem with high affinity; and iii) harness the free energy gained on protein-protein interaction or the energy generating TonB-ExbBD complex of the cell membrane to translocate haem into the periplasm. The haem uptake systems of Gram negative bacteria fall into one of two categories, those that transport haem and those that in addition to transporting haem, also sense and signal the presence of extracellular haem via a secreted haemophore (W. Huang & Wilks, 2017; Smith & Wilks, 2012). Haemophores are low molecular weight proteins (~20kDa) that are secreted into the extracellular environment and sequester free haem released from oxidized or damaged haemproteins (Yukl et al., 2010). The most well characterized haemophore systems are the Has systems of S. marcescens (Biville et al., 2004) and P. aeruginosa (Ochsner, Johnson, & Vasil, 2000b). The distinction between the haemophore and non-haemophore dependent uptake systems is the cell surface signaling (CSS) function of the haemophore-dependent OM receptors. In P. aeruginosa the mechanism of haem transport by the haemophore and non-haemophore dependent OM receptors is similar in that both receptors require the coupling of cytoplasmic membrane potential through a TonB-ExbBD complex to transport haem into the periplasm, where it is sequestered by a periplasmic binding protein (PBP) (Fig 1A). The holo-PBP acts as a soluble receptor for the ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-transporter that then transports haem into the cytoplasm, where the action of an iron-regulated haem oxygenase releases Fe3+ with biliverdin IXβ/δ (BVIX β/δ) and carbon monoxide (CO) as by-products (Fig 1B) (Ratliff, Zhu, Deshmukh, Wilks, & Stojiljkovic, 2001; Wilks & Ikeda-Saito, 2014). P. aeruginosa encodes a second BVIXα selective haem oxygenase BphO in an operon with a bacteriophytochrome sensor kinase BphP that responds to far-red light as its sensory input (Barkovits, Harms, Benkartek, Smart, & Frankenberg-Dinkel, 2008; Mukherjee, Jemielita, Stergioula, Tikhonov, & Bassler, 2019; Wegele, Tasler, Zeng, Rivera, & Frankenberg-Dinkel, 2004). As will be outlined in the following sections the ability to traffic haem through the iron-regulated HemO with its unique BVIX-regioselectivity has significance for the physiology and pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa.

Figure 1.

Overview of P. aeruginosa haem uptake and utilization. A. Haem is bound by HasAp or extracted from hemoglobin (Hb) for transport across the outer membrane by the TonB-dependent receptors HasR and PhuR, respectively. In the periplasm haem is shuttled to the ABC transporter (PhuUV) by the periplasmic binding protein (PhuT) and actively transported across the cytoplasmic membrane by PhuUV. Haem is sequestered by the cytoplasmic haem binding protein (PhuS) for transfer to haem oxygenase (HemO). B. HemO oxidatively cleaves haem releasing iron, carbon monoxide (CO), and biliverdin IXβ/δ.

4. REGULATION OF EXTRACELLULAR HAEM SENSING, SIGNALING AND TRANSPORT

4.1. Regulation of the Has Operon by the Haem Dependent Extra Cytoplasmic Function (ECF) σ Factor System.

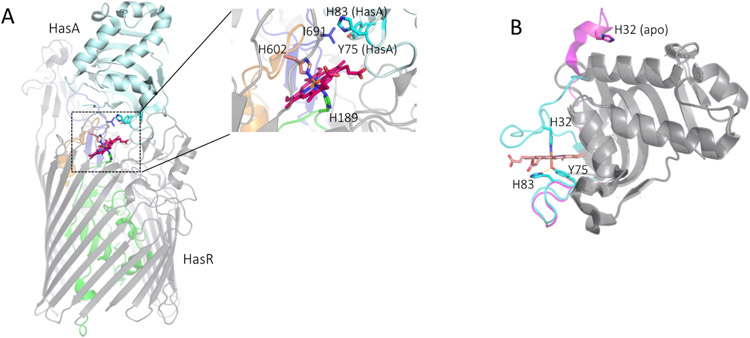

The ECF σ factor systems are a major family of bacterial regulators and the most diverse group of alternatives σ factors (Casas-Pastor et al., 2021; Staron et al., 2009). ECF σ systems typically sense and respond to a variety of signals generated outside or within the cell membrane including oxidative and osmotic stress, heat shock, and most notably ferric-siderophores and haem, where they are often referred to as iron starvation ECF systems because of their role in regulating iron uptake (Campagne, Allain, & Vorholt, 2015; Llamas, Imperi, Visca, & Lamont, 2014; Llamas et al., 2008; Otero-Asman, Wettstadt, Bernal, & Llamas, 2019). Haem dependent ECF systems have been identified in a number of Gram negative organisms, including the S. marcescenns and P. aeruginosa σ/anti-σ factor hasSI systems (Biville et al., 2004; Cescau et al., 2007; Ochsner et al., 2000b). The P. aeruginosa hasSI genes are found in close proximity to the OM haem receptor and transducer HasR, and its cognate extracellular haemophore HasAp (Ochsner et al., 2000a). The OM haem receptors range in molecular weight from 70-95 kDa and share a similar overall fold consisting of a 22-25 β-stranded barrel and a globular domain (N-terminal "plug") that occludes the pore of the β-barrel (Fig 2A) (Smith & Wilks, 2012). The haemophore-dependent HasR receptor has an extended N-terminal that includes an ECF signaling domain. In the only available crystal structure, that of the S. marcescens HasAp-HasR complex, the extended N-terminal signaling domain is not visible (Fig 2A) (Krieg et al., 2009). However, the structure of the truncated N-terminal signaling domain has been independently solved by NMR (Malki et al., 2014).

FIGURE 2. Structure of the HasA-HasR complex and HasAp.

(A) S. marcescens HasA docked to HasR. HasR, the membrane spanning β-barrel and extracellular loops are shown in grey, the N-terminal plug in green. The haemophore HasA is shown in cyan the haem in red and the HasR extended L7 and L8 loops that interact with HasA orange and blue, respectively. The boxed area is shown magnified in the right panel as a close-up view of haem ligated in HasR through H602 from the FRAP/PNPL L7 and H189 of the N-terminal plug. L8 I691 that provides the steric clash with the H32 loop of HasA shown in blue. The HasA protein is shown in cyan with the displaced H83 and Y75 as sticks. Adapted from PDB file 3CSL. (B) Overlay of the P. aeruginosa apo-HasAp and holo-HasAp structures. Apo- and holo HasAp H32 and Y75 loops shown in magenta and cyan, respectively. Overall fold shown in grey. Residues as labeled with the Y75-H83 hydrogen bond interaction highlighted in yellow. PDB files 3MOK (apo) and 3ELL holo).

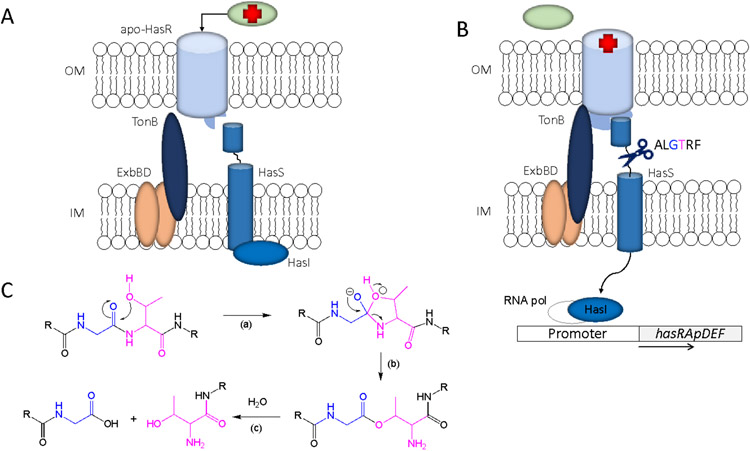

The function of the OM receptor N-terminal signaling domain is to sense and transduce the presence of extracellular haem via activation of the ECF σ factor system (Llamas et al., 2014). Early studies reconstituting the S. marcescens ECF system in an E. coli hasR-lacZ reporter strain elucidated the sequence of events leading to activation of the σ factor HasI and transcriptional upregulation of the hasRA operon (Biville et al., 2004). The interaction of exogenously added holo-HasA with the OM receptor was proposed to transduce the signal through the N-terminal domain inactivating the anti-σ factor HasS, and releasing the σ factor HasI (Fig 3A). HasI enables the recruitment and binding of RNA polymerase to the hasR promoter upregulating hasR transcription. Deletion of the N-terminal signaling domain resulted in a receptor competent to transport haem, but unable to direct the holo-HasA activation of the ECF system and transcriptional upregulation of hasR. It was further shown that the apo-HasA H32A-Y75A mutant, which is unable to coordinate haem but can still interact with HasR, does not activate the signaling cascade indicating haem is required for signal transduction (Cwerman, Wandersman, & Biville, 2006). Conversely, the E. coli hasR-lacZ strain expressing a HasR H189A/H603A mutant receptor that is unable to accept haem, is not competent to activate the signaling cascade in the presence of WT holo-HasA. Based on these results it was proposed that haem release to the receptor is required for haem signaling and transport. However, inconsistent with the requirement for haem release to the receptor in triggering signaling, the HasA single point mutants H32A or Y75A were reported to be competent to transport haem but deficient in signaling (Cwerman et al., 2006). We have recently revisited haem signaling and transport in P. aeruginosa by supplementing a ΔhasAp strain with purified HasAp variants and monitoring activation of the CSS cascade by readout of hasR mRNA levels by qPCR (Dent, Mourino, Huang, & Wilks, 2019). In contrast to the previous studies we show H32A and Y75A HasAp are not only competent to trigger the CSS cascade but show increased signaling activity compared to wt HasAp. We interpreted this to be the result of an off pathway kinetically trapped “signaling” intermediate on interaction of the HasAp variants with HasR. The implication of these results in terms of haem release and transport will be discussed in the section 5.1.

FIGURE 3. Schematic representation of the ECF σ-factor signaling system.

(A) Signaling cascade in the “off” state prior to holo-HasAp binding. The N-terminal signaling domain as well as the TonB box are not bound by HasR. (B) Holo-HasA binds to HasR inducing a conformational change in the N-terminal signaling domain that recruits the anti-σ factor, promoting self-cleavage triggering the release of HasI. Additionally, it is thought that the TonB-box engages with the periplasmic TonB complex. (C) Proposed autocatalytic cleavage and corresponding N-O acyl rearrangement. The HasS self-cleavage motif ALGTRF located between the N and C-terminal domain with the catalytic residues shown in cyan (Thr) and blue (Gly). (C) (a) nucleophilic attack of Thr (cyan) on the preceding Gly residue (blue) forming a tetrahedral hydroxyoxazolidine intermediate. (b) rearrangement of the tetrahedral intermediate to yield the ester. (c) ester hydrolysis and peptide cleavage.

We further analyzed the role of the HasR haem coordinating His residues of the extracellular FRAP/PNPNL loop H624 and N-terminal plug H221 (Fig 2A) in transduction of the haem signal (Dent & Wilks, 2020). The activation of the CSS cascade by P. aeruginosa hasRH624A supplemented with haem or holo-HasAp was significantly dampened compared to the parent strain. In contrast, the hasRH221R strain showed no activation of the CSS cascade compared with the significant increase in hasR mRNA on addition of haem or holo-HasAp to the wt PAO1 strain. Taken together the data suggests that haem coordination to the N-terminal plug is required to trigger the conformational rearrangement allowing transduction of the signal through the N-terminal plug domain, whereas the FRAP/PNPNL loop residue while important for optimal signaling is critical for haem transport across the OM (Dent & Wilks, 2020). Moreover, in the case of the HasR H221R N-terminal plug mutant, inactivation of the CSS cascade and inability to sense extracellular haem also had an effect, direct or indirect, on the mRNA and protein expression profile of the major haem transporter PhuR. Given the non-redundant roles of the Has and Phu systems in haem utilization, and their distinct roles within the host it is perhaps not surprising there would be a regulatory link. Although the nature of the regulatory link between the Has and Phu systems remains to be elucidated, it is possible the ECF σ factor HasI directly or indirectly plays a role in regulation of the phu operon.

It has also been proposed that haem signaling across the OM requires interaction of the HasR receptor with the TonB-ExbBD complex. The TonB-ExbBD complex couples the proton motive force of the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) to HasR to actively transport haem into the cell. In S. marcescens there are two TonB systems one of which termed HasB, is specific for the HasR receptor and does not interact with or support haem transport by the non-haemophore dependent receptor HemR (Benevides-Matos, Wandersman, & Biville, 2008). In vitro isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements of the interaction between the C-terminal domains of TonBCTD and HasBCTD with HasR, revealed that HasB has a distinct binding mode that differs from TonB (Lefevre, Delepelaire, Delepierre, & Izadi-Pruneyre, 2008). Structural determination of the HasB C-terminal domain (HasBCTD) revealed a novel fold distinct from that of previously characterized TonB periplasmic domains (de Amorim et al., 2013). Furthermore, chemical shift perturbations on titration of the HasBCTD or TonBCTD with varying length HasR peptides incorporating the consensus sequence (98ALDSLTVLGAGG108) referred to as the TonB box, revealed a shifted sequence for the “HasB box” (95GALALDSLGAGG102) but not the aforementioned TonB box. Electron microscopy (EM), small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) along with three-dimensional structural characterization of HasR in two signaling states led to a model where the signaling domain is some 90 Å and 70 Å from the periplasmic face of the receptor in the HasA free and holo-HasA activated state, respectively (Wojtowicz et al., 2016). Consistent with a conformational rearrangement on haem binding to the N-terminal plug, earlier NMR studies of the S. marcescens system suggested that binding of holo-HasA to HasR induced conformational changes within the HasR N-terminal plug known to interact with HasB (de Amorim et al., 2013), as well as the HasR N-terminal signaling domain that triggers inactivation of HasS (Malki et al., 2014). Taken together the accumulated data reveals a model where holo-HasA binding and release of haem to HasR induces a conformational change on the periplasmic face of the receptor that couples both haem signaling and transport (Fig 3B). Interestingly, in the P. aeruginosa genome there are three TonB genes of which TonB1 has been shown to be required for the utilization of haem (Poole, Zhao, Neshat, Heinrichs, & Dean, 1996; Zhao & Poole, 2000). Interestingly, TonB1 is also specifically required for the FpvA dependent CSS cascade through the anti-σ factor FpvR and the σ factor, PvdS (Shirley & Lamont, 2009). In contrast TonB2 while compensating to some degree for the loss of TonB1 in terms of iron acquisition cannot compensate for signal transduction. Moreover, TonB3 is required for the correct assembly of extracellular pilli, most likely through its involvement in the secretion and transport of pilli or a component required for assembly (Ainsaar, Tamman, Kasvandik, Tenson, & Horak, 2019; B. Huang, Ru, Yuan, Whitchurch, & Mattick, 2004). Based on bacterial genetics and the emerging structural information on TonB it is evident that ECF σ factor associated receptors require a specialized TonB to stabilize the signaling domain for interaction with the anti-σ factor, whereas receptors associated only with transport may only require a generic TonB capable of supporting the transport of structurally diverse ligands.

Once the signal from the OM receptor is transduced to the CM bound anti-σ factor, there are several mechanisms by which activation of the respective σ-factors occurs, including i) degradation of the anti-σ factor cytoplasmic domain (Draper, Martin, Beare, & Lamont, 2011), ii) direct sensing of a signal such as redox that lowers the binding affinity of the σ-factor for the anti σ-factor (Kang et al., 1999), or iii) alternative anti-σ factor binding partners (C. C. Chen, Lewis, Harris, Yudkin, & Delumeau, 2003). The iron starvation ECF anti-σ factors such as FoxR undergo a self-cleavage event between their N- and C-terminal domains triggering the release of the σ-factor (Fig 3B) (Bastiaansen, Otero-Asman, Luirink, Bitter, & Llamas, 2015). The conserved autoproteolytic sequence motif (ALGTRF) identified in the iron-siderophore anti-σ factors is also found in the P. aeruginosa HasS anti-σ factor suggesting a similar self-cleavage mechanism activates the σ factor, HasI (Bastiaansen, van Ulsen, Wijtmans, Bitter, & Llamas, 2015) (Fig 3B). In FoxR the autocatalytic cleavage event is driven by a non-enzymatic N-O acyl rearrangement through nucleophilic attack of a threonine side chain on the preceding glycine residue within the ALGTRF motif (Fig 3C) (Bastiaansen, van Ulsen, et al., 2015).

ECF σ factors regulate gene expression by binding the target promoter and redirecting transcription initiation. In RpoE-like ECF σ factors, the binding motif recognized in the target promoter is typically characterized by a consensus AAC in the −35 region, and a conserved CGT motif at −10 (Lane & Darst, 2006), (Staroń et al., 2009). However, there are a number of σ factors with uncharacterized DNA binding elements. This lack of a consensus motif has been attributed to differences in promoter recognition or, most recently, to the requirement of additional DNA sequences localized outside of the σ binding site that play a major role in promoter recognition through modulation of DNA structure (Todor et al., 2020) (Agnoli, Haldipurkar, Tang, Butt, & Thomas, 2019). In S. marcesens where hasS is autoregulated comparison of the promoter sequences upstream of hasR and hasS identified the sequence TTTACGGGTTT, which partially overlaps the −35 region of both target promoters (Biville et al., 2004). Site-directed mutagenesis confirmed this region as the DNA motif recognized by protein HasI to bind and modulate the gene expression. Despite the high sequence homology and similar chromosomal organization between the haem-sensing ECF systems in S. marcescens and P. aeruginosa, the hasS and hasI genes in P. aeruginosa their regulation differs. In P. aeruginosa the hasS and hasI genes are co-transcribed in an operon and hasS is not autoregulated by HasI as is the case in S. marcescens (Dent et al., 2019). Therefore, identification of the HasI binding motif was not possible via comparison of promoter regions. In S. marcescens the autoregulation and accumulation of the anti-σ factor HasS is a means to rapidly down regulate the CSS cascade in response to fluctuations in extracellular haem availability. It could be assumed in the case of P. aeruginosa the lack of autoregulation over HasS would be a disadvantage. However, P. aeruginosa has integrated several alternate post-transcriptional mechanisms to control gene expression of the haem-sensing system which are described in the following sections. Moreover, in a recent review article it was reported that P. aeruginosa also encodes a second haem activated σ factor system hxuIS upstream of a putative haem transporter huxA although the role of this system in haem sensing and/or utilization has yet to be determined (Otero-Asman et al., 2019).

4.2. Biliverdin Dependent Post-transcriptional Regulation of the Extracellular Haemophore HasAp.

We have previously shown the P. aeruginosa has operon is transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA that is rapidly processed into individual mRNAs (Dent et al., 2019). Although the P. aeruginosa ribonuclease (RNase) responsible for the processing of the operon has yet to be identified there is precedent for an RNAseE-like processing of the arcDABC operon, a polycistronic mRNA encoding the enzymes of the deiminase pathway (Gamper, Ganter, Polito, & Haas, 1992; Gamper & Haas, 1993). Interestingly, the hasR and hasAp mRNAs differed in their mRNA stabilities in both iron-deficient and haem supplemented conditions (Dent et al., 2019). In iron-deficient conditions the hasAp transcript was significantly more stable than hasR. In contrast in the presence of haem while the stability of the hasAp mRNA was unchanged, the hasR transcript was more stable on active haem uptake. The mechanism of haem-dependent stabilization of hasR is not known but may involve binding of a sRNA or ribosomal binding protein. It is interesting to speculate as to a potential role of the haem-dependent sRNA PrrH given its role in iron and haem homeostasis (Nelson et al., 2019; Oglesby-Sherrouse & Vasil, 2010; Reinhart et al., 2017).

In addition to the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms described above, we have recently identified a third level of post-transcriptional regulation over HasAp protein expression by the haem metabolites BVIXβ and/or BVIXδ (Mourino, Giardina, Reyes-Caballero, & Wilks, 2016). In this study a P. aeruginosa hemO variant reengineered to produce BVIXα rather than BVIXβ/δ when grown in the presence of haem, showed a decrease in HasAp protein levels compared to the wt PAO1 strain. Moreover, the decrease in protein levels was not related to differences in mRNA levels or their relative stabilities. Recent unpublished studies have identified extended 5’-UTR and 3’-UTR sequence in the hasAp mRNA transcript as well as a region of complementarity between them. A series of translational fusions have further shown that the 5’-UTR is required for the BVIXβ/δ upregulation of HasAp expression and the 3’UTR interaction with the 5’UTR couples mRNA stability to translational efficiency by maintaining the 5’UTR structure (Mouriño, in preparation). Thus, extracellular haem flux and metabolism ensures that the ECF system is in an activated state and extracellular HasAp levels are maintained as long as haem is actively being transported, and iron levels remain below the threshold for Fur suppression of the has operon. However, when BVIXβ and/or BVIXδ levels decrease, either as a result of Fur-repression of hemO or a decrease in extracellular haem levels, HasAp translation is rapidly downregulated dampening the ECF signal. Therefore, haem dependent transcriptional activation through HasI, together with post-transcriptional regulation of HasAp by BVIXβ and or BVIXδ, allows the cell to rapidly respond to extracellular haem levels in a Fur-independent manner.

4.3. PhuS-dependent Regulation of the Iron and Haem Regulated sRNAs prrF1,F2/PrrH

Interestingly, the tandem arrangement of the prrF1,F2 sRNAs and the presence of the phuS gene encoding the cytoplasmic haem binding protein are genetically linked and found only in pathogenic P. aeruginosa (Fig 4). Given the genetic link between the prrF1,F2 locus and phuS, we hypothesized that haem flux through PhuS may play a role in integrating haem metabolism into the sRNA regulatory network. Employing a combination of CHIP-PCR, EMSA, and fluorescence anisotropy, we found apo-PhuS but not holo-PhuS binds upstream of the prrF1,F2/prrH locus (Wilson et al., 2021). Apo-PhuS binds within the prrF1 promoter and partially overlaps the Fur binding site. Moreover, in the ΔphuS strain the loss of PhuS leads to abrogation of the haem-dependent regulation over both prrF and prrH. Based on this data we propose a model where the equilibrium between apo-PhuS and holo-PhuS modulates the relative expression of PrrH (Fig 5). In low iron conditions, the equilibrium shift in favor of apo-PhuS that on binding and reorganization of the prrF1 promoter leads to an increase in the relative expression of PrrH (Fig 5A). However, during active haem uptake the equilibrium shifts toward holo-PhuS downregulating the relative levels of PrrH compared to PrrF1 and/or PrrF2 (Fig 5B). As intracellular iron levels increase Fur represses both the prrF1 and prrF2 genes (Fig 5C). We further hypothesize that PhuS and Fur may be antagonistic, as the optimal apo-PhuS binding site includes the Fur box but apo-PhuS has no affinity for the Fur box alone. Therefore, PhuS through its role as a “rheostat” in controlling the flux of haem through HemO (see section 5.3) plays a central role in integrating the haem utilization with the iron-sparing response by regulating the levels of BVIXβ/δ and the relative expression of the PrrF and PrrH sRNAs, respectively.

FIGURE 5. Proposed model for the heme-dependent modulation of PrrF and PrrH expression by PhuS.

(A) Equilibrium toward apo-PhuS leads to increase in the relative expression of PrrH on PhuS binding and reorganization of the prrF1 promoter . (B) Active haemuptake shifts the equilibrium toward holo-PhuS down regulating PrrH relative to PrrF1 and/or PrrF2. (C) Increased intracellular iron levels lead to Fur repression of the prrF1,2 operon. Adapted from Wilson et al, (2021).

5. HAEM UPTAKE AND UTILIZATION BY THE HAS AND PHU SYSTEMS

5.1. Haem Uptake by the HasR and PhuR Haem Transporters.

Bacterial pathogens express multiple OM haem receptors as a means to sense and extract haem from a variety of substrates such as hemoglobin (Hb), hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Hb-Hp) and hemopexin. P. aeruginosa as previously described encodes the non-redundant Has and Phu systems (Smith & Wilks, 2015). Early studies on the S. marcescens Has system reconstituted in E. coli indicated HasR could acquire haem at micromolar concentrations, however the efficiency of haem uptake was greatly enhanced in the presence of the haemophore HasA (Ghigo, Letoffe, & Wandersman, 1997). It was further determined that HasA from S. marcescens binds haem with extremely high affinity (Ka = 5.3 x 1010 M−1) but does not interact directly with Hb (Letoffe, Ghigo, & Wandersman, 1994). This was confirmed on kinetic and spectroscopic studies of the P. aeruginosa HasAp that concluded haem acquisition from met-Hb is a passive process as the association rate is similar to that of free hemin, with the tight affinity being attributed to the slow dissociation rate (Yukl et al., 2010).

Once bound haem is coordinated axially through residue His-32 and Tyr-75 of HasAp with His-83 providing a hydrogen bond to stabilize the Tyr-75 ligation (Fig 2B) (Alontaga et al., 2009). Biophysical studies employing X-ray crystallography, NMR and molecular dynamic simulations of wt HasAp and the haem coordination mutants H32A, Y75A and H83A provided further insight into haem binding and release (Alontaga et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2014; Yukl et al., 2010). All of the mutants were shown to have a similar overall fold and binding affinities (KD’s) to that of the wt holo-HasAp. Furthermore, kinetic analysis by stopped-flow UV-visible and rapid freeze quench spectroscopy show the mutants load haem with similar biphasic kinetic parameters as the wt HasAp (Kumar et al., 2014). The biphasic kinetics are attributed to initial binding being driven by hydrophobic interactions of haem with the Y75 loop, followed by coordination of Y75 with a slower coordination of the H32 loop. The slow rate of loop closure suggested this closure was not due to the H32 loop randomly sampling an open and closed state, but rather a triggering of loop motions on haem binding to the Y75 loop (Yukl et al., 2010). Moreover, X-ray and NMR analysis did not reveal any disorder in the His-32 loop in apo-HasAp and the authors proposed this was due to “zipper-like” salt-bridge interactions between residues in the H32 loop and on the surface of the core domain (Jepkorir et al., 2010). Mutation of the loop residues Arg-33 and His-32 which are involved in the network of salt-bridge, hydrogen bond and hydrophobic stacking interactions with E113, D22 and Y26 of the core domain, release the loop which adopts a conformation similar to that of holo-HasAp (Kumar et al., 2016).

Until recently one of the least understood aspects of haem signaling and transport was the release of haem from the haemophore HasAp to HasR and the sequence of events leading to translocation into the periplasm. In vitro studies of haem signaling and transport by the OM receptors is complicated by the fact activation of the OM receptor requires activation by the cytoplasmic membrane bound TonB-ExbBD system. Previous studies of the S. marcescens HasA-HasR system suggested release of haem from the high affinity HasA to HasR could occur in vitro in the absence of the HasB-ExbBD system (Izadi-Pruneyre et al., 2006), contradicting earlier reports suggesting TonB system was required for haem release to the receptor (Letoffe, Nato, Goldberg, & Wandersman, 1999). In our previous studies of the holo-HasAp interaction with HasR we did not observe stable complex formation or haem release to HasR, suggesting the energy transducing TonB system is required to drive haem release (Smith, Modi, Sun, Dawson, & Wilks, 2015). Similarly, the non-haemophore dependent PhuR was unable to extract haem from methemoglobin (metHb) (Smith et al., 2015), consistent with the previously characterized HmbR of N. meningitidis (Mokry et al., 2014).

The crystal structure of the S. marcescens HasA/haem/HasR complex provided further insight into the HasA-HasR interaction and haemrelease (Fig 2A) (Krieg et al., 2009). In the crystal structure haem is displaced 9.2Å from the binding pocket of HasA and coordinated within HasR by H189 on the N-terminal plug and H603 of the L7 loop (Fig 2B). Furthermore, the loop containing the coordinating H32 of HasA (Fig 2A) is displaced from the binding pocket by loops L7 and L8 of HasR (Fig 2A and B). This loop displacement was presumed to provide the trigger for haem release from HasA and led to the hypothesis that protein-protein induced conformational changes alone could trigger haem transfer from the high affinity HasA site to the lower affinity HasR. Based on the crystal structure a model for haem release was proposed where protein-protein interaction induces a steric displacement of the HasA H32 ligand by I671 of the HasR L8 extracellular loop, while haem remains coordinated to Y75 (Fig 2A). The role of HasR I671 was confirmed in the crystal structure of the holo-HasA/HasR-I671G complex, where the absence of this steric displacement H32 remains coordinated to the haem (Krieg et al., 2009). In a subsequent step HasA H83, which forms a hydrogen bond to the axial Y75 ligand (Fig 2B), is rotated away from the HasA binding site weakening the tyrosinate character of Y75 and releasing haem to HasR.

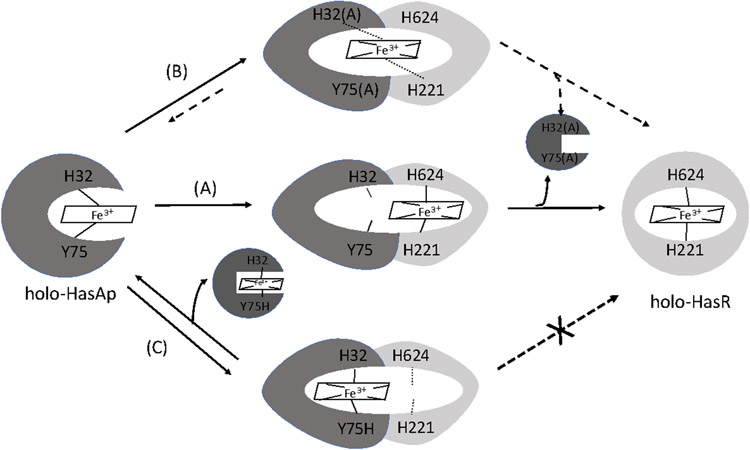

We recently revisited the mechanism of haem release from HasAp to HasR in a P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp strain supplemented with wt holo-HasAp or the H32A, Y75A, Y75H or H83A variants (Dent et al., 2019). As noted in the previous section P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp when supplemented with either H32A and Y75A holo-HasAp show increased signaling activity compared to wt holo-HasAp. Similarly, the H83A holo-HasAp variant also showed a similar CSS profile to the H32A and Y75A holo-HasAp complexes consistent with the role of H83 in facilitating haem release to the HasR receptor. Interestingly, the P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp when supplemented with Y75H holo-HasAp, which we predicted would form a stronger bis-His coordinated haem that would prevent haem release to the receptor, showed a growth defect not observed for the wt holo-HasAp or the H32A, Y75A mutants. Moreover, the Y75H holo-HasAp supplementation did not show any activation of the CSS cascade. We next determined if the HasAp variants, particularly the Y75H HasAp, were competent to support haem uptake by reconstituting the HasAp proteins with 13C-haem and directly measuring the levels of 13C-BVIXβ and 13C-BVIXδ products. The Y75A, H83A and H32A variants that give rise to the kinetically trapped signaling intermediate were competent to transport haem, albeit with a slight lag compared to WT. In contrast supplementation 13C-haem-reconstituted Y75H HasAp consistent with the growth defect and lack of signaling was unable to transport haem (Dent et al, unpublished). Based on the cumulative data we proposed a revised mechanism for haem release from HasAp to HasR where rather than a sequential release of H32 to yield the H32 “off” intermediate where Y75 remains coordinated (Fig 6A), we propose a concerted mechanism where on protein-protein interaction both Y75 and H32 are released simultaneously (Fig. 6B). This mechanism is supported by the data obtained for the H32A and Y75A HasAp variants where removal of either haem ligand yields a kinetically trapped “off” pathway intermediate while competent to signal is less efficiently transported, hence the sustained activation of the CSS cascade (Fig 6A). However, for the Y75H HasAp variant, the free energy gain on interaction of HasAp with HasR is unable to drive haem release from HasAp, eliminating both haem signaling and transport (Fig 6C). We attributed this to the introduction of the stronger ligation inhibiting haem release to HasR. Tyrosine is a relatively weak ligand in haem binding proteins that is strengthened by increasing the tyrosinate character through a hydrogen bond with a neighboring histidine residue. These properties have been exploited in the bacterial haem transport proteins with the conservation of the His-Tyr motif allowing rapid haem binding and relatively slow off rates that can be modulated on protein-protein interaction.

FIGURE 6. Proposed mechanism for haem transfer from holo-HasAp to HasR.

(A) holo-HasAp WT interaction with HasR. A conformational change and the free energy gained on HasAp-HasR interaction drives the concerted release of the HasAp Y75 and H32 ligands treleasing haem to HasR. (B) holo-HasAp Y75A (or H32A) interaction with HasR. The open haem coordination site in Y75A (or H32A) mutant is occupied by a H2O molecule that on interaction with HasR is displaced forming the kinetically trapped intermediate leading to increased haem signaling and decreased transport. (C) holo-HasAp Y75H interaction with HasR. The free energy gained on protein-protein interaction of holo-HasAp Y75H with HasR is not sufficient to drive release of haem from holo-HasAp Y75H blocking both signaling and transport. Adapted from Dent et al, (2019).

A similar analysis of the P. aeruginosa hasRH624A, hasRI694G and hasRH221R allelic strains provided further insight into the role of the HasR extracellular loop (L8) and the FRAP/PNPNL loop and N-terminal plug coordinating residues in steric displacement and haem signaling and transport, respectively (Fig 2A) (Dent & Wilks, 2020). The hasRH624A allelic strain lacking the L7 (FRAP/PNPNL) loop haem coordinating His, when supplemented with holo-HasAp was competent to activate the CSS cascade but not to transport haem, as judged by the lack of 13C-BVIXβ and IXδ isomers when supplemented with 13C-haem loaded HasAp. In contrast the hasRH221R strain lacking the N-terminal plug coordinating His, was not able to activate the CSS cascade nor transport haem. The hasRI694G strain was able to activate the signaling cascade albeit less efficiently than the wt PAO1 strain, but was not competent to transport haem. Taken together, the data are consistent with a model where conformational rearrangement on interaction of holo- HasAp with HasR, facilitated by the steric clash of Ile-694, triggers haem release to HasR (Fig 2A). Following release, haem capture on the HasR N-terminal plug via His-221 transduces the signal through the N-terminal domain, inactivating the anti-σ factor HasS, releasing the σ factor HasI, and transcriptionally activating the has operon. Simultaneously, release of HasAp from HasR allows for the FRAP/PNPNL loop to close of the receptor channel from external environment activating haem transport from the OM to the periplasmic face. These recent studies are difficult to reconcile with earlier reports on the S. marcescens Has system that suggested the H75A and H32A HasAp mutants, while lacking the ability to activate the CSS cascade, were competent to transport haem (Cwerman et al., 2006). However, it is notable that when provided 13C-haem rather than holo-HasAp the allelic strains show no growth deficiency and produce similar levels of 13C-BVIXβ and BVIXδ as wt PAO1, suggesting haem, but not haem complexed to HasAp, is available to the variants via the Phu uptake system. Therefore, the conflicting data may be due to the nature of the haem source and/or alternate uptake mechanisms.

The non-haemophore dependent OM haem receptors capture haem directly from or on its release from host haemproteins. These OM receptors share a significant level of sequence (25-65%) and structural similarity to the haemophore-dependent receptors indicating a common mechanism of haem transport (Smith & Wilks, 2012). In contrast to the bis-His ligation found in the majority of OM haem receptors spectroscopic and site directed mutagenesis studies determined the non-haemophore dependent receptor of P. aeruginosa, PhuR, coordinates haem through Y519 of the FRAP/PNPNL loop and H124 of the N-terminal plug (Smith et al., 2015). Through a combination of bacterial genetics and 13C-haem uptake studies it was shown that the P. aeruginosa ΔhasR strain was able to utilize haem as efficiently as the wild type, whereas the ΔphuR strain was unable to utilize haem as well as the wild type strain, despite the ~30-fold increase in HasR (Smith & Wilks, 2015). The non-redundant nature of the PhuR and HasR receptors and the fact both are required for optimal haem utilization suggests that the Phu system is the major facilitator of haem uptake, whereas the Has system plays a more significant role in haem sensing and signaling. Indirect evidence for these distinct roles comes from the aforementioned studies that have shown in chronic P. aeruginosa infection the Phu system is the primary iron acquisition system (Marvig et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2014).

As mentioned previously the Tyr-His haem coordination represents an emerging motif in high affinity haem acquisition systems including the aforementioned secreted HasA haemophores (Alontaga et al., 2009) and the Gram positive lipid-anchored surface exposed Isd haem binding proteins (Grigg, Mao, & Murphy, 2011). Interestingly, the N. meningitidis HmbR receptor has a five-coordinate haem ligated through a single Tyr residue (Mokry et al., 2014) as is found in the high affinity periplasmic binding proteins (Ho et al., 2007). We recently introduced the Tyr-His motif into the haemophore dependent HasR receptor, mutating the FRAP/PNPNL loop H624 to Y to mimic the PhuR coordination (Dent & Wilks, 2020). Interestingly, despite the fact the hasRH624Y allelic strain was able to activate the signaling cascade indicating that haem could be displaced from holo-HasAp, the strain is deficient in haem transport. This lack of active haem uptake is most likely a result of Y624 being sterically hindered form coordinating the haem and promoting loop closure, or an inability on coordination to trigger conformational change within the N-terminal plug to engage TonB and drive uptake. Further determination of the coordination properties of the purified HasR variants by absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopic studies are currently underway.

In earlier studies absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectral analysis of the Y519H PhuR variant confirmed the bis-His coordination (Smith et al., 2015). It will be interesting to further determine if this PhuR variant is competent to capture and transport haem on complementation of the P. aeruginosa ΔphuR strain. Given previous studies of the “PhuR-like” coordination in the hasRH624Y allelic strain the haem coordinating ligands are critical for capture and transport, however, it is evident additional structural features including the extracellular loops and the nature of the protein-protein interactions are critical for efficient haem extraction and transport. Biophysical and in vivo uptake studies addressing the role of the His-Tyr motif as well as other structural features of the OM receptors in haem extraction and transport are ongoing in our laboratory.

As previously mentioned the first step in haem transport across the OM involves a ligand induced conformational change that exposes the aforementioned TonB box promoting an interaction between the receptor and TonB (Khursigara, De Crescenzo, Pawelek, & Coulton, 2005). Previous crystallography studies of the closely related ferrichrome (FhuA) and cobalamin (BtuB) OM receptors show that upon binding of TonB, an interprotein β-sheet is formed at the TonB box positioning TonB in proximity to the plug (Shultis, Purdy, Banchs, & Wiener, 2006). Moreover, structural studies combined with computational experiments suggested a shearing or mechanical pulling mechanism, where hydration of the central β-sheet of the N-terminal plug domain disrupts an extensive electrostatic interaction network with the inner face of the β barrel. In this model the perpendicular force applied to the β-sheet on interaction with TonB drives local unfolding of the N-terminal plug creating a hydrated channel for passage of the ligand (Chimento, Kadner, & Wiener, 2005; Shultis et al., 2006). Moreover, spin-labeling coupled with molecular dynamic (MD) simulations suggest that ligand binding on the extracellular face of the N-terminal plug extends the TonB box on the periplasmic face of the receptor for interaction with TonB, and these interactions extend beyond the TonB box providing a ligand-sensitive conformational switch for transport (Gresock & Postle, 2017). Recent crystallographic studies combined with computational approaches of the P. aeruginosa catecholate receptor PfeA support a similar model where ligand binding induces large rearrangement of the N-terminal plug loops providing a gateway to an internal channel through specific reordering of hydrogen bond interactions between the external loops and the N-terminal plug domain. It remains to be seen exactly how haem binding induces rearrangement of the extracellular loops and N-terminal plug to transport the more hydrophobic haem molecule but similar studies combining biophysical, computational and in vivo uptake studies will further elucidate haem translocation by the OM receptors.

Haem translocated through the OM receptor by either HasR or PhuR is captured by the periplasmic haem binding protein (PBP) PhuT (Fig 7A), that then acts as a soluble receptor for a haem-dependent ABC (ATP-binding cassette)-transporter in the cytoplasmic membrane (Krewulak & Vogel, 2008). The mechanism of haem release from the OM receptors to the PBPs is not known, however, studies of the ferrichrome PBP FhuD have suggested the TonB protein may act as a scaffold for recruitment of the PBP placing it in the vicinity to readily access the ligand for shuttling to the ABC-transporter (Carter et al., 2006). Similarly, the cobalamin PBP BtuF was shown by phage display and SPR experiments to interact directly with TonB, suggesting a common mechanism where TonB acts as a scaffold for optimal positioning of the PBP for initial ligand binding (James, Hancock, Gagnon, & Coulton, 2009). Such a mechanism would presumably also extend to haem given its hydrophobicity and toxicity, and must also involve the OM receptor to provide specificity and selectivity in recruitment of the required PBP. Binding of the PBP to the OM receptor-TonB complex would also require the energetic cost of ligand transfer to be met by the free energy on protein-protein interaction.

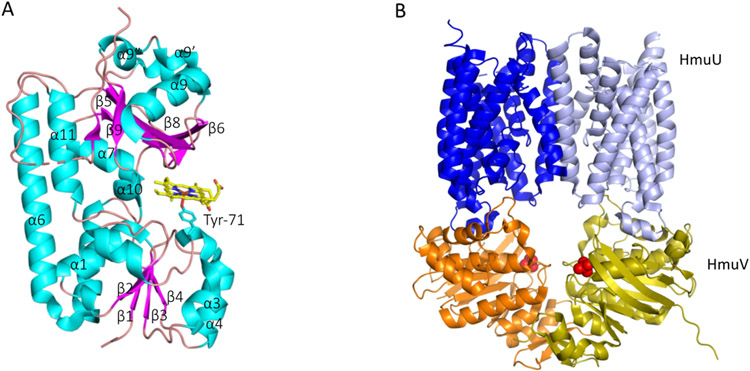

FIGURE 7. Structure of PhuT and the Y. pestis HmuUV.

(A) holo-PhuT with β-sheet/loops in magenta and α-helices in cyan (PDB file 2R79). (B) Overall structural fold of the HmuUV transporter. HmuU membrane subunits are shown in blue and light blue, and the HmuV ATPase are subunits in orange and yellow. Bound phosphates shown in red (PDB file 4G1U).

5.2. ATP-dependent Transport of Haem Across the Cytoplasmic Membrane by PhuT-UV

The soluble PBPs deliver their ligand to specific ABC-transporters and are divided into three classes based on the number of their inter-domain connections (Borths, Locher, Lee, & Rees, 2002; Dwyer & Hellinga, 2004). All three classes of PBPs are comprised of N- and C-terminal globular domains that form a ligand binding cleft between their closed domains. The haem binding proteins belong to the class III proteins, where the N- and C-terminal domains consist of a 5-stranded β-sheet flanked by helices (Fig 7A). The crystal structure of the P. aeruginosa PhuT ligates haem through Tyr-71 on the N-terminal domain at the interface of the haem binding cleft. Crystal structures of the related Shigella dysenteriae apo- and holo-ShuT show little overall change in structure with minor changes within the haem binding pocket, where the Tyr ligand points away from the pocket in apo-ShuT and reorients toward the interior of the pocket on haem coordination (Ho et al., 2007). Although the haem binding affinity for the PBPs has not been measured directly, the rate constants for haem extraction by apo-Hb from holo-ShuT suggest they have relatively high affinity due to a slow off rate (Eakanunkul et al., 2005). The conservation of Tyr with its unique ligation properties and relatively pH insensitive and inert redox nature is advantageous in the context of haem sequestration and transport.

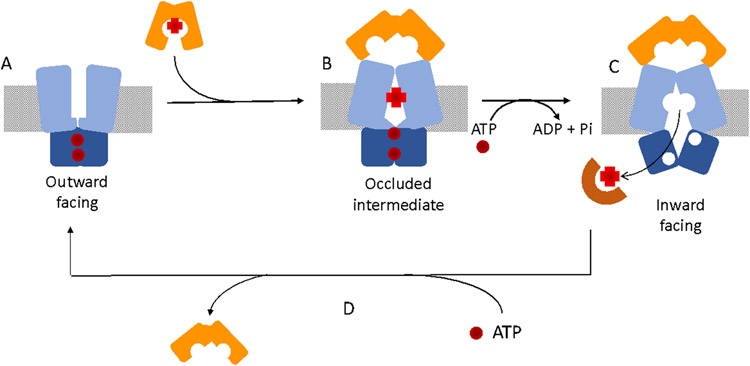

ABC-transporters constitute one of the largest protein super families and are primarily responsible for the ATP-dependent transport of substrates across membranes (Higgins, 1992, 2001). The ABC-transporters are composed of two trans-membrane domains (TMD) that form the translocation channel, and two cytoplasmic nucleotide-binding domains (NBD) that hydrolyze ATP (Fig 7B). The TMDs vary in sequence and length providing substrate specificity, while the NBDs are highly conserved specifically within the Walker A and Walker B ATP-binding motifs (Walker, Saraste, & Gay, 1982). The P. aeruginosa PhuUV system has not been structurally characterized, however, the haem ABC transporters from Y. pestis HmuUV, and the related Burkholderia cenocepacia BhuUV-BhuT complexes, have provided significant insight into the mechanism of haem transport across the CM (Naoe et al., 2016; Woo, Zeltina, Goetz, & Locher, 2012). The haem ABC-transporters belong to the type II family comprising two trans-membrane subunits and two corresponding ATP-binding subunits (Fig 7B). In the structures of the nucleotide free form, the HmuUV transporter was crystallized in an outward facing conformation with the periplasmic gate open, whereas the BhuUV and BhuUV-T structures crystalized in the inward facing conformation with the cytoplasmic gate open. These differences are related in relatively minor differences in conformation within three of the nine transmembrane helices in each monomer, whereas the remaining helices remain relatively unchanged (Naoe et al., 2016). The authors concluded the conversion between the inward to the outward facing transporter could occur by rotation of the core helices altering the BhuU-BhuU interface that drive conformational changes in the movable helices, triggering the switch from the inward to outward conformation. Based on the accumulated data from the structures of the HmuUV (Woo et al., 2012) and BhuUV (Naoe et al., 2016) transporters, and intermediates captured for the related vitamin B12 BtuCD transporter (Borths et al., 2002; Hvorup et al., 2007; Korkhov, Mireku, & Locher, 2012; Korkhov, Mireku, Veprintsev, & Locher, 2014), a general model for ligand translocation has been proposed (Fig 8). In the first step haem is transferred to the periplasmic channel of the transporter following release from the PBP (conformation B in Fig 8). At this point the transporter in an occluded state based on structures of vitamin B12 trapped intermediates within the BtuCD transporter (Korkhov et al., 2012). Haem is then transported and released to the cytoplasm and the transporter is in the inward post-translocation state (conformation C in Fig 8). On release of haem ATP rapidly binds and facilitates the release of the PBP and resets the ABC-transporter to the open state (conformation A in Fig 8). Recent computational modeling and MD simulation studies are consistent with a peristaltic movement of haem translocation consistent with the occluded intermediate state (Tamura, Sugimoto, Shiro, & Sugita, 2019; Tamura & Sugita, 2020).

FIGURE 8. Proposed mechanism of haem translocation by the haem ABC-transporters.

(A) Outward facing conformation where the TMD interactions form a periplasmic gate blocked from the cytoplasm. (B) Docking of the PBP releases haem to the channel causes the periplasmic gate to close giving the proposed occluded intermediate. (C) ATP hydrolysis drives a conformational change toward the inward facing conformation releasing haem to the cytoplasmic binding protein. (D) Binding of ATP releases the PBP and resets the transporter in the outward facing conformation.

Haem as a hydrophobic and redox active molecule is unlikely to be directly released into the cytoplasm. Our laboratory has shown the Shigella dysenteriae ShuUV transporter requires the cytoplasmic haem binding proteins ShuS for active release of haem from the transporter translocation channel (Burkhard & Wilks, 2008). This finding was the first direct evidence that the physiological function of the cytoplasmic haem binding proteins is to capture and control the flux of exogenously acquired haem into the cell.

5.3. Extracellular Haem Flux through the Cytoplasmic Haem Binding Protein PhuS and the Iron-Regulated Haem Oxygenase HemO.

Early biochemical studies from our laboratory characterized the cytoplasmic haem binding protein PhuS as a specific haem chaperone to the iron-regulated HemO (Bhakta & Wilks, 2006; Block et al., 2007; Lansky et al., 2006). This interaction was specific for the holo-PhuS whereas apo-PhuS did not interact with HemO. Moreover, biochemical and biophysical characterization of apo- and holo-PhuS showed that haem binding drives a conformational rearrangement of PhuS that promotes the interaction with HemO (O'Neill, Bhakta, Fleming, & Wilks, 2012). The conformational rearrangement was further investigated by site-directed mutagenesis, hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) and MD simulations, revealing long-range allostery between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains critical for the conformational rearrangement on haem binding (Deredge et al., 2017). Furthermore, the regions undergoing allostery are within helices that interact with HemO and are most likely required for triggering haem release. The significance of the PhuS-HemO couple in regulating haem uptake and utilization was confirmed in the phuS and hemO deletion strains. Earlier 13C-haem uptake studies from our laboratory had shown the ΔhemO strain was unable to transport haem into the cell despite upregulation of the haem transport systems (Barker, Barkovits, & Wilks, 2012). We concluded the metabolic flux of haem through HemO was required to drive extracellular haem uptake. In contrast on deletion of phuS haem uptake at low haem concentrations was inefficient compared to wt PAO1, however, at higher haem concentrations the total BVIX levels were significantly greater than wt PAO1 with haem being shuttled through HemO and BphO (O'Neill & Wilks, 2013b). Therefore, the absence of PhuS leads to unregulated haem uptake through both HemO and BphO. On deletion of both phuS and hemO, elevated haem uptake was observed with haem being degraded solely by BpHO. Therefore, PhuS acts as a rheostat by specifically trafficking and regulating the flux of haem through HemO. The recent discovery that the apo-PhuS conformer functions as a transcriptional regulator of the prrF1,F2 and prrH sRNAs defines PhuS as a pivotal regulator integrating haem utilization and the iron-sparing response in global iron-homeostasis (Wilson et al., 2021).

6. HAEM UPTAKE AND UTILIZATION AS AN ANTIMICROBIAL TARGET

6.1. Outer Membrane Haem Receptors as Vaccine Targets

The wealth of structural information on the surface exposed TonB-dependent receptors of Gram negative pathogens has led to extensive investigation of their potential as vaccine targets (Rohde & Dyer, 2003). The early studies focused on the transferrin and Hb receptors of H. influenza, Neisseria meningitidis and N. gonorrhea (Holland et al., 1996; Richardson & Stojiljkovic, 1999). However, a perceived drawback of targeting haem receptors has been the high level of redundancy and phase variation in haem uptake systems (C. J. Chen, Elkins, & Sparling, 1998; Ekins, Bahrami, Sijercic, Maret, & Niven, 2004; Richardson & Stojiljkovic, 1999). Many bacterial strains including Hemophilus ducreyi have three TonB-dependent receptors, of which only the hemoglobin receptor HgbA is required for acquisition of iron during infection (Leduc et al., 2008). Initial immunization studies with HgbA in a swine model for chancroid provided some immunity from infection (Afonina et al., 2006) and passive immunity was observed when swine were administered HgbA anti-serum (Leduc et al., 2011). P. aeruginosa poses a significant challenge given the phase variation for the iron and haem receptors depending on the site and stage (acute versus chronic) of infection. A random phage display study identified immunogenic peptides corresponding to OM receptors and secreted proteins (Beckmann et al., 2005). Further mapping of these proteins to transcriptomic data of early stage cystic fibrosis infections suggested iron-siderophore receptors as potential targets. More recent immunization studies with a pyoverdine receptor (FpvA) conjugated to the keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) showed decreased bacterial burden and lung edema following P. aeruginosa challenge in mice (Sen-Kilic et al., 2019). To date the P. aeruginosa haem receptors have not been the target of vaccine development. However, the emergence of next-generation sequencing and proteomics have provided insight into the role of haemuptake and utilization in infection, offering some hope for their potential in the development and optimization of vaccine candidates.

6.2. Metalloporphyrin and Salophen Based Inhibitors of Haem Utilization

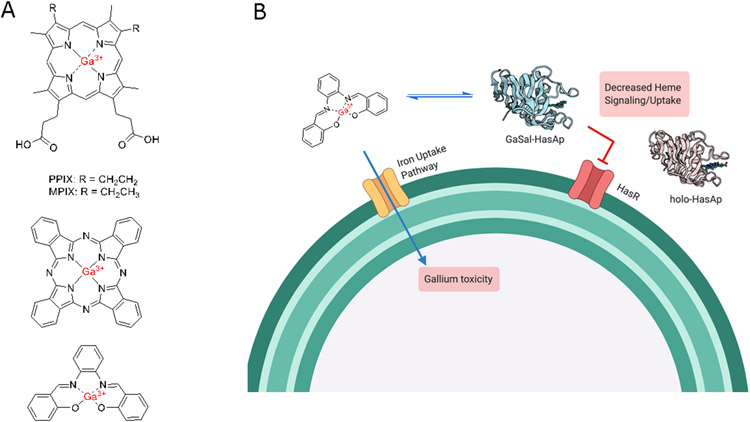

It has been known for some time that non-iron metalloporphyrins have broad spectrum antibacterial activity against both Gram positive and Gram negative organisms (Bozja, Yi, Shafer, & Stojiljkovic, 2004; Olczak, Maszczak-Seneczko, Smalley, & Olczak, 2012; Stojiljkovic, Kumar, & Srinivasan, 1999). In particular, Ga3+ due to its similar size and charge to Fe3+ has been utilized as an ideal iron mimic. Moreover, Ga3+ under physiological conditions cannot be reduced leading to inhibition of redox reactions and a disruption of important physiological pathways. Ganite® (Ga(NO3)3) an FDA approved drug for the treatment of hypercalcemia in cancer patients is currently under investigation as an antibiotic (Goss et al., 2018). In P. aeruginosa, Ga3+-PPIX (Fig 9A) as a redox inert Fe3+-PPIX mimic is actively transported into the cell and inhibits both haem degradation by HemO as well as haem dependent cellular processes (Stojiljkovic et al., 1999). In clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strains, including some categorized as multi-drug resistant Ga3+-PPIX reduced bacterial viability in both planktonic and biofilm cultures (Arivett et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2016). Ga3+-phthalocyanine (Ga-Pc) (Fig 9A), following uptake by the P. aeruginosa HasAp-HasR system, has been exploited to generate singlet oxygen on irradiation with near-infrared light to reduce bacterial viability (Shisaka et al., 2019). This study not only highlighted the ability of the Has system to transport expanded porphyrin scaffolds but its potential to deliver antimicrobials to the cell.

FIGURE 9. Haem mimics as inhibitors of haem uptake and utilization.

(A) Gallium compounds including Ga3+-PPIX/MPIX (Top), Ga3+-Phthalocyanine (Middle) and Ga3+-Salophen (Bottom). (B) Schematic of Ga3+-Salophen as a substrate for active siderophore uptake and inhibition of the Has CSS cascade.

We have recently taken an alternative approach by utilizing the ability of Ga3+-salophen (Ga3+-Sal) (Fig 9A) to inhibit both P. aeruginosa haemophore dependent CSS and siderophore uptake (Fig 9B) (Centola et al., 2020). HDX-MS of Ga-Sal bound HasAp versus holo-HasAp revealed a significant increase in flexibility in the H32 and Y75 loops due to loss of interactions with the larger porphyrin scaffold. These subtle but significant changes in HasAp conformation and dynamics, while not disrupting the interaction with the OM receptor HasR, are enough to prevent haem release to the receptor inhibiting both haem dependent CSS and transport. Interestingly, Fe3+-Sal in contrast to the Ga complex did not inhibit growth of P. aeruginosa, despite inhibition of the CSS cascade. Moreover, the ability of Fe3+-Sal to support growth in the P. aeruginosa ΔhasR/ΔphuR strain lacking the OM haem receptors confirmed the uptake of the salophen complexes is independent of the haem transport and the result of internalization via the xenosiderophore receptors. Thus Ga3+-Sal acts as a dual function inhibitor disrupting haem sensing and uptake, while being actively transported into the cell as a xenosiderophore where the redox inert Ga3+ further inhibits iron-dependent cell processes (Fig 9B). As exogenous siderophores have been shown to repress endogenous pyoverdine and pyochelin biosynthesis, the additional capacity of Ga3+-Sal to repress endogenous siderophore production could potentially enhance its inhibitory capability (Perraud et al., 2020). We are further investigating the role of the metallosalophens in repressin endogenous siderophore production and uptake.

6.3. Targeting Iron Release and Haem Sensing with HemO Selective Inhibitors

The ultimate step in the utilization of haem as an iron source, is the oxidative cleavage and release of iron by HemO (Fig 1B). As mentioned in the previous sections the cytoplasmic haem binding protein PhuS and HemO are essential in driving extracellular haem uptake. Therefore, targeting HemO will reduce haem flux and prevent utilization of haem bound iron. Furthermore, by targeting HemO the reduction in the haem metabolites BVIXβ/δ will further dampen the post-transcriptional upregulation of the extracellular haemophore HasAp, and dampen the CSS cascade required to sense extracellular haem levels. Previous strategies targeting the mammalian haem oxygenases (HO) have focused on porphyrin mimics (Maines, 1981; Nowis et al., 2008; Rouhani et al., 2014) or inhibition of the holo-enzyme through direct coordination of azole based inhibitors to the haem iron (Salerno et al., 2015; Salerno et al., 2013; Vlahakis et al., 2009; Vlahakis et al., 2006). Our research group has taken an alternative approach to selectively target the apo-HemO by taking advantage of the significantly smaller active site compared to that of the human HO-1(Friedman, Lad, Li, Wilks, & Poulos, 2004; Schuller, Wilks, Ortiz de Montellano, & Poulos, 1999). Initial in silico screening identified several small molecule inhibitors of P. aeruginosa HemO that bind at the active site (Hom et al., 2013) or a distant allosteric site (Heinzl et al., 2016). Interestingly, the allosteric site takes advantage of a salt-bridge between D99 and R188 on the surface of the protein that is required for conformational flexibility during catalysis, and is unique to the P. aeruginosa HemO (Heinzl et al., 2018). Most recently, a high-throughput screening approach identified acitretin, an FDA approved oral retinoid, as a potential lead compound in the development of novel inhibitors of the P. aeruginosa HemO (Robinson, Wilks, & Xue, 2021). Interestingly, acitretin binding to the BVIXβ/δ regioselective P. aeruginosa HemO is ~100-fold tighter than that to the BVIXα-selective haemoxygenases, including the human HO-1 and HO-2 enzymes. Moreover, acitretin was shown to not only inhibit enzyme activity, but also through the reduction in BVIXβ/δ haem metabolites also down regulates the HasAp-dependent CSS cascade. Future structural analysis and optimization of the acitretin scaffold holds promise for the development of potent dual acting HemO inhibitors targeting iron-acquisition and extracellular haem signaling in P. aeruginosa.

7. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The challenges of transporting haem, a highly reactive lipophilic and toxic cofactor across the OM, requires highly regulated and extremely specialized transport systems. Our current knowledge of the mechanisms by which P. aeruginosa acquires haem has been greatly aided by the wealth of structural information on the OM-receptors of Gram negative bacteria. However, there remain significant gaps in our knowledge of haem uptake as it relates to the complex nature of TonB-coupled conformational changes within the N-terminal domain required to drive haem transport. Future studies must meet the challenges of understanding the nature of protein-protein driven allostery in triggering haem coordination and spin-state changes critical for haem translocation.

Finally, while the regulation of bacterial haem acquisition systems by iron-responsive transcriptional repressors such as Fur has been well studied, haem and haem metabolite dependent regulation at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level is less well understood. We are beginning to understand the complexity and integration of the iron and haem regulatory networks, however, elucidating the regulatory mechanisms by which these systems adapt to the host environment will be the key to identifying new and novel antimicrobial strategies. Systems biology approaches including next generation genomic and proteomic methodologies will aid in identifying key factors in the host-pathogen response to haem and enhance the discovery and development of targeted vaccine and antimicrobial strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A.W. would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health for studies described herein. The authors thank Garrick Centola, for help with figures. Figures 2 and 7 created in PYMOL version 2.3.2. Figure 9B created in BioRender (biorender.com).

ABBREVIATONS

- CSS

cell surface signaling

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- OM

outer membrane

- CM

cytoplasmic membrane

- PBP

periplasmic binding protein

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- ECF

extra cytoplasmic function

- Has

haem assimilation system

- Phu

Pseudomonas haem uptake

- Fur

Ferric uptake regulator

- PrrF

Pseudomonas RNA regulated by iron

- PrrH

Pseudomonas RNA regulated by haem

- PPIX

protoporphyrin IX

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, funding or financial interests that might be perceived as influencing the objectivity of this review.

REFERENCES

- Afonina G, Leduc I, Nepluev I, Jeter C, Routh P, Almond G, et al. (2006). Immunization with the Haemophilus ducreyi hemoglobin receptor HgbA protects against infection in the swine model of chancroid. Infect Immun, 74(4), 2224–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnoli K, Haldipurkar SS, Tang Y, Butt AT, & Thomas MS (2019). Distinct Modes of Promoter Recognition by Two Iron Starvation σ Factors with Overlapping Promoter Specificities. J Bacteriol, 201(3), e00507–00518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsaar K, Tamman H, Kasvandik S, Tenson T, & Horak R (2019). The TonBm-PocAB System Is Required for Maintenance of Membrane Integrity and Polar Position of Flagella in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol, 201(17) e00303–00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alontaga AY, Rodriguez JC, Schonbrunn E, Becker A, Funke T, Yukl ET, et al. (2009). Structural characterization of the hemophore HasAp from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: NMR spectroscopy reveals protein-protein interactions between Holo-HasAp and hemoglobin. Biochemistry, 48(1), 96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arivett BA, Fiester SE, Ohneck EJ, Penwell WF, Kaufman CM, Relich RF, et al. (2015). Antimicrobial Activity of Gallium Protoporphyrin IX against Acinetobacter baumannii Strains Displaying Different Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 59(12), 7657–7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banin E, Vasil ML, & Greenberg EP (2005). Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102(31), 11076–11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber MF, & Elde NC (2014). Nutritional immunity. Escape from bacterial iron piracy through rapid evolution of transferrin. Science, 346(6215), 1362–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker KD, Barkovits K, & Wilks A (2012). Metabolic flux of extracellular heme uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is driven by the iron-regulated heme oxygenase (HemO). J Biol Chem, 287(22), 18342–18350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovits K, Harms A, Benkartek C, Smart JL, & Frankenberg-Dinkel N (2008). Expression of the phytochrome operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on the alternative sigma factor RpoS. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 280(2), 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaansen KC, Otero-Asman JR, Luirink J, Bitter W, & Llamas MA (2015). Processing of cell-surface signalling anti-sigma factors prior to signal recognition is a conserved autoproteolytic mechanism that produces two functional domains. Environ Microbiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaansen KC, van Ulsen P, Wijtmans M, Bitter W, & Llamas MA (2015). Self-cleavage of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cell-surface Signaling Anti-sigma Factor FoxR Occurs through an N-O Acyl Rearrangement. J Biol Chem, 290(19), 12237–12246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KW, & Skaar EP (2014). Metal limitation and toxicity at the interface between host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 38(6), 1235–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann C, Brittnacher M, Ernst R, Mayer-Hamblett N, Miller SI, & Burns JL (2005). Use of phage display to identify potential Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products relevant to early cystic fibrosis airway infections. Infect Immun, 73(1), 444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevides-Matos N, Wandersman C, & Biville F (2008). HasB, the Serratia marcescens TonB paralog, is specific to HasR. J Bacteriol, 190(1), 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta MN, & Wilks A (2006). The mechanism of heme transfer from the cytoplasmic heme binding protein PhuS to the delta-regioselective heme oxygenase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry, 45(38), 11642–11649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biville F, Cwerman H, Letoffe S, Rossi MS, Drouet V, Ghigo JM, et al. (2004). Haemophore-mediated signalling in Serratia marcescens: a new mode of regulation for an extra cytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor involved in haem acquisition. Mol Microbiol, 53(4), 1267–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]