Abstract

Radiation cancer therapy with ultra-high dose rate exposure, so called FLASH radiotherapy, appears to reduce normal tissue damage without compromising tumor response. The aim of this study was to clarify whether FLASH exposure of proton beam would be effective in reducing the DNA strand break induction. We applied a simple model system, pBR322 plasmid DNA in aqueous 1 × TE solution, where DNA single strand breaks (SSBs) and double strand breaks (DSBs) can be precisely quantified by gel electrophoresis. Plasmid DNA were exposed to 27.5 MeV protons in the conventional dose rate of 0.05 Gy/s (CONV) and ultra-high dose rate of 40 Gy/s (FLASH). With both dose rate, the kinetics of the SSB and DSB induction were proportional to absorbed dose. The SSB induction of FLASH was significantly less than CONV, which were 8.79 ± 0.14 (10−3 SSB per Gy per molecule) and 10.8 ± 0.68 (10−3 SSB per Gy per molecule), respectively. The DSB induction of FLASH was also slightly less than CONV, but difference was not significant. Altogether, 27.5 MeV proton beam at 40 Gy/s reduced SSB and not DSB, thus its effect may not be significant in reducing lethal DNA damage that become apparent in acute radiation effect.

Keywords: FLASH, proton, high dose rate, DNA strand breaks, plasmid DNA

INTRODUCTION

FLASH radiotherapy targets tumors while minimizing the damage to the surrounding normal tissues by ultra-high dose rate (> 40 Gy/s) [1,2], which exceeds currently employed clinical dose rates by about a factor of 100–1000. The advantageous feature of FLASH, the so called sparing effect, enables radiation therapy to maintain the effectiveness of tumor killing, or increase dose delivery at the tumor region without increasing the toxicity in normal health tissues [3–6]. FLASH effect studies have begun in electrons [3] and photons [4, 7, 8]. The first clinical FLASH radiotherapy trial with electrons proved its feasibility and safety with favorable outcomes both on normal skin protection and tumor control. A recent overview reported a protective effect in normal tissues for FLASH ranging from about 1.4 to 1.8 [6].

The FLASH effect depends on the balance between dose, oxygen concentration, radical production and reactions, which contribute to the reduction of biological toxicity (9–12). There are two major hypotheses for the sparing effect of FLASH. First is the radiochemical depletion of oxygen at FLASH dose rates that suppresses the fixation of indirect radiation-induced DNA damage, which results in a sparing effect conferred to the irradiated tissue [8]. Second is the improved immune response, due to the fast exposure time leading to less irradiation of circulating immune cells by FLASH radiotherapy compared to CONV radiotherapy, which results in a reduction of radiation-induced chronic inflammation and other deteriorative effects [9, 13].

For protons, recent papers have reported the sparing effects in mammalian cells [14, 15], and animal models [5]. It is well known that protons and heavier charged particle therapy have advantages compared to modern photon and electron therapy [16, 17]. Thus, there are emerging needs to characterize the biological effects of proton irradiation due to the advantageous features that encourage the adoption of proton radiotherapy [18, 19]. However, as for charged particles, the subject remains controversial [20, 21]. Recently, Kusumoto et al. [22] reported the radiation chemical yields (G values) of 7-hydroxy-coumarin-3-carboxylic acid (7OH–C3CA), which is produced by water radiolysis using coumarin-3-carboxylic acid (C3CA) solution as a radical scavenger of hydroxyl radicals. They have clearly demonstrated that increasing the dose rate from 0.05 to 160 Gy/s significantly reduced the value of G (7OH-C3CA) due to the oxygen depletion of 27.5 MeV protons. The proton-FLASH effect has been investigated in many radiobiological studies with cells and mice. Furthermore, simulation studies and a kinetic model are vigorously developed to understand the mechanism of the FLASH effect [10, 23]. However, studies are limited by the availability of irradiators that can provide such dose rates. The mechanism behind the sparing effect of the proton-FLASH in correlation with DNA damage induction needs further investigation to clarify the mechanistic aspect of the proton-FLASH effect.

Here, we report the first investigation on physical and chemical damage processes in DNA of proton-Flash versus conventional proton irradiation, which were assessed by investigating the DNA single strand breaks (SSBs) and double strand breaks (DSBs) induction rate in a simple model system, plasmid DNA in aqueous conditions, where SSBs and DSBs were quantified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid pBR322 DNA were exposed to 27.5 MeV protons in the conventional dose rate of 0.05 Gy/s (CONV) and ultra-high dose rate of 40 Gy/s (FLASH) to the and the SSB and DSB induction rates were validated.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Sample preparation

The pBR322 plasmid DNA solution (4361 bp, 0.5 μg/μl in 1 × TE) were purchased from Takara Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan and was over 90% in supercoiled form (form 1) and without any linear form (form 3). Plasmid DNA solution were diluted in 1 × TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) to be 50 ng/μL and each DNA samples were prepared in 0.2 mL PCR tubes (PCR-02F2, BMBio Equipment Co., LTD) containing 50 μL of DNA solution for proton beam irradiation.

Irradiation

Irradiation experiments were performed at the AVF-930 cyclotron facility [24] in the Institute for Quantum Medical Science (iQMS), National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST), Chiba, Japan. Irradiation set ups are described in detail elsewhere [22]. Briefly, protons were accelerated up to 27.5 MeV, where energy were 27.5 MeV at the sample irradiated position after penetrating beam monitors, beam exit window, air gaps and other necessary equipment installed in the beam line. Beam fields were confirmed using EBT3 GAF chromic film (Ashland Advance Materials, NJ) to assure the sample tubes were set in uniform beam field within ±5% difference. The beam intensity was monitored with a parallel plate ionization chamber installed in front of the sample and it was characterized with the Markus ionization chamber for absorbed dose. The thickness of the PCR tube was 0.5 mm and that of solution was 4 mm coaxial with beam trajectory. An average linear energy transfer (LET) in the solution was calculated to be 2.3 keV/μm with SRIM code [25].

The beam currents were controlled to be 0.2 nA and 300 nA, which the absorbed dose rates were 0.05 Gy/s and 40 Gy/s, respectively. The two dose rates were chosen to compare the DNA strand break yields of plasmid DNA in solution condition between conventional dose rate (CONV) and high dose rate (FLASH). Absorbed doses were controlled by the time width of pulse signals to the beam deflector installed in the beam line.

Agarose gel electrophoresis and quantification of DNA strand breaks

DNA solution of 10 μl (pBR322 DNA: 500 ng) were mixed with 1uL of 10 × gel-loading blue buffer (40% sucrose and 0.25% bromophenol blue) and then electrophoresed in 1.4% agarose gel (LO3, Takara-Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) in 1 × TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 5 mM sodium acetate and 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.8 adjusted with acetic acid), at 4.2 V/cm for 4 h at 4°C. Under these electrophoresis conditions, two SSBs (one on the opposite strand) with less than 6 base pair apart were detected as DSB [26, 27]. Gels were then stained in 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide (EtBr) solution for 1 hr, and subsequently washed twice in water for 30 min each. Fluorescence gel images were recorded using Molecular Imager Pharos FX system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), which excite the EtBr with 532 nm laser and records the fluorescence after 605 nm band path emission filter. The gel image was exported as raw TIFF format and analyzed using Multi Gauge Version 2.3 (Fujifilm Holdings Corporation, Tokyo).

Using the image analysis software, the total fluorescent intensities in the three bands corresponding to the three forms of plasmid DNA, super-helical closed circular (form 1, no strand break), open circular (form 2, with SSB) and linear (form 3, with DSB) were determined. To account for the reduced uptake of the ethidium bromide by form 1 DNA, a correction factor of 1.42 described by Lloyd et al. [28], was used. The numbers of SSB (NSSB), and DSB (NDSB) per DNA molecule were calculated using equations (1–3) described by Povirk et al. [29], where F₁-₃ represent the fractions of forms 1–3, respectively:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

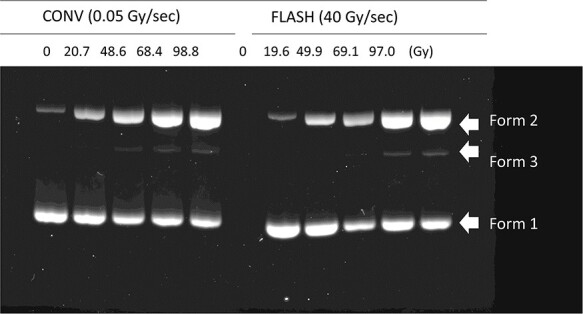

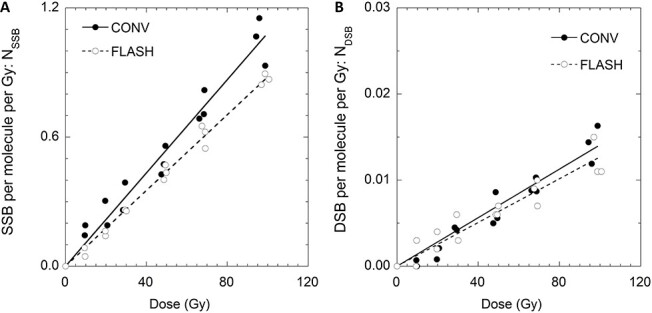

Figure 1 shows the representative result of agarose gel electrophoresis. The pBR322 plasmid DNA were separated into non-strand break supercoiled DNA, open circular DNA with an SSB and linear DNA resulted from a DSB, which were form 1, form 2 and form 3 mentioned in the previous section. It is apparent that the fluorescence of the non-damaged DNA (Form 1) decreased as form 2 increased, depending on the increased absorbed dose. Form 3 was detectable from 20 Gy and quantified from the fluorescence gel images. Figure 2 show the induced number of SSB and DSB per plasmid molecule (NSSB and NDSB) as a function of absorbed dose at CONV (blue, circle) and FLASH dose rate (red, circle). Plots in the figures are from three independent irradiation experiments. Both NSSB and NDSB were increased proportional to the absorbed dose, and they were fitted to a linear function with the least-squares method. The slopes are the induction rate of NSSB and NDSB per absorbed dose, RSSB and RDSB, respectively. The averaged values of RSSB and RDSB for CONV and FLASH and the standard errors of three independent experiments are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Representative image of agarose gel electrophoresis. CONV and FLASH irradiated pBR322 plasmid DNA in solution were electrophoresed and were isolate according to their molecular forms. Induction rate (NSSB and NDSB per Gy) analyzed from the shown gel image were, 9.7 × 10−3 (NSSB/molecule/Gy) and 9.4 × 10−5 (NDSB/Gy) for CONV and 8.8 × 10−3 (NSSB/ molecule/Gy) and 9.5 × 10−5 (NDSB/ molecule/Gy) for FLASH, respectively. Fluorescence values of each band detected in the lanes are indicated in supplemented Table S1.

Fig. 2.

Number of SSB (NSSB, Panel A) and DSB (NDSB, Panel B) and per plasmid irradiated at CONV and FLASH dose rate as a function of absorbed dose in Gy. The solid lines are the fit obtained by linear regression of the experimental data.

Table 1.

SSB and DSB induction rate in pBR322 plasmid DNA by FLASH and CONV irradiation

| Exposure | Dose Rate | Induction rate, R | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Gy/s] | ×10 −3 [NSSB, NDSB/Gy] | R SSB/RDSB | ||

| R SSB | R DSB | |||

| CONV | 0.05 | 10.8 ± 0.68 | 0.118 ± 0.021 | 91.9 ± 11.4 |

| FLASH | 40 | 8.79 ± 0.14 | 0.108 ± 0.016 | 81.1 ± 6.9 |

| 2 Reff | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.18 | 0.88 ± 0.019 | |

| P-value | 0.044 | 0.57 | 0.29 | |

1Induced number of SSB and DSB per molecule per Gy. 2 Ratio of FLASH/CONV 3 standard errors from 3 independent experiments are shown in ±. P-values are from student’s t-test.

Significant suppression was observed in RSSB of FLASH compared to that of CONV. RSSB for CONV and FLASH were 10.8 ± 0.68 [×10−3 (NSSB/molecule/Gy)] and 8.79 ± 0.14 [×10−3 (NSSB/molecule/Gy)], respectively. RSSB compared to CONV are shown as Reff, a ratio FLASH:CONV, which was 1:0.81, in another words, FLASH suppressed the RSSB nearly 19% compared to CONV. In the chemical stage of radiation damage, most of the hydrated electrons and hydrogen radicals produced by water radiolysis react with the dissolved molecular oxygen resulting cytotoxic superoxide anion and the perhydroxyl radicals. However, under the FLASH dose-rate it is estimated that the oxygen is consumed by hydrated electrons and hydrogen radicals, and its rediffusion into the irradiated volume can be excluded, a transient acute radiation-induced hypoxia increases the radio-resistance [23]. Kusumoto et al. [22] measured the G values of 7OH-C3CA of 27.5 MeV proton beam in wide range of dose rate from 0.05 Gy/s to 160 Gy/s and found that G(7OH-C3CA) reduces with increasing dose rate. They concluded that under FLASH dose rate, oxygen molecules were rapidly consumed by the hydrogen radicals and hydrated electrons produced by the water radiolysis, leading the lower G(7OH-C3CA) values. From the work others [22, 23], it can be estimated that FLASH irradiation would reduce the production of cytotoxic superoxide anion and the perhydroxyl radicals by oxygen depletion, resulting suppression of DNA damage induction. If the case, the FLASH effect would be strongly dependent on the radiation quality that results radiological process of indirect action and high oxygen enhancement ratio. The proton beam in this study was a 27.5 MeV proton which has G(OH)100 eV of ~3 and OER that are equivalent to that of X-rays and gamma-rays [22, 30, 38, 39].

However, the degree of suppression of SSB can be considered small compared to the suppression rate of G(7OH-C3CA) value of FLASH compared to CONV, which was nearly 50%. As mentioned earlier, the plasmid DNA were exposed to proton beam in 1 × TE buffer which contains 10 mM Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) that react as radical scavenger against hydroxyl radicals with the scavenging capacity of 1.5 × 107 (s−1) [31–33]. Tris modification by hydroxyl radicals are estimated to consume oxygen molecules which oxidizes primary radicals to peroxyl species [33, 34]. Oxygen depletion effects of proton-FLASH may have effect following chemical reaction, but negligible on initial chemical process against the hydroxyl radicals. Notably, it was previously reported that G(OH) value do not change and are consistent in the dose rate in the range of 0.05 Gy/s to 160 Gy/s [22]. Therefore, it can be estimated that the Tris scavenged the OH radicals equally in CONV and FLASH, but other radicals decreased in FLASH due to oxygen depletion effect, which may have contributed to the significant but small reduction of RSSB.

DSB induction rate, RDSB for CONV and FLASH were 0.118 ± 0.21 [×10−3 (NSSB/molecule /Gy)] and 0.108 ± 0.016 [×10−3 (NDSB/molecule/Gy)], respectively. Reff for RDSB was 0.92 ± 0.12, however, the difference was not significant. In our set up, three different molecular forms of plasmid DNA were isolated and quantified with agarose electrophoresis that detected DSBs as a fraction of linear type form 3. Plasmid DNA will need two SSBs induced in the distance less than 6 bp to form 3, in other words, when the DSBs were induced by two indirect actions, such as two OH radical attacks, the OH radicals must be produced in area of 4 nm2 (6 bp × 0.34 nm/bp). DSB would not be induced by OH radicals alone, since a sufficient number of OH radicals would not be produced per track of 27.5 MeV proton. However, in terms of ‘spurs’ will be produced along the proton tracks which is defined to contain energy up 100 eV and have average of three ion pairs in the size of 4 nm in diameter area. The dimension of ‘spurs’ relatively identical to the DNA helix, if overlapped with DNA, it will result in multiple and various complex damage. On the other hand, the contribution of oxygen depletion effect of proton-FLASH, which suppressed hydrogen radicals and hydrated electrons are the suppression of indirect action of the biological effect, that are mostly detected as reduced values in SSB induction and not DSB. In addition, there are calculations that show a single hydrated electron can induced base damages but is not effective enough to induce a DNA strand break [36], which explains why there was no significant reduction in DSB at the FLASH condition. In fact, others reported that acute responses in mammalian cells exposed to proton-FLASH did not result in suppression on DSB induction and cell survival [15]. Indeed, the FLASH effect would strongly correlate on radiation types. For example, charged particles near the Bragg peak are well known to have high LET with highly localized dose distribution along its tracks [37] that result in a small oxygen enhancement ratio [38, 39]. It is explained as a result of small G(OH) value [24, 32] and low consumption of the molecular oxygen per 100 eV at charged particles with high LET that drastically decrease near the Bragg peak [12]. Thus, studies that reported little impact of proton-FLASH on acute effects in mammalian cells [15] may be due to the radiation quality of low energetic charged particles that were used [5]. Still, hydrogen radicals and hydrated electrons can contribute to DNA damage at the vicinity of induced DNA strand breaks, such as clustered DNA damage. Most importantly, induction of clustered DNA damage at vicinity DSBs are critical and become a challenge to the repair system of living cells [40–43]. Therefore, the possibility of the sparing effect of FLASH due to the oxygen depletion effect are undeniable, and further investigation will be necessary to confirm the physical and chemical damage process to DNA.

In the present study, we have evaluated the SSB and DSB induction rate in plasmid DNA of aqueous conditions by proton beams under the CONV and FLASH. As a result, proton-FLASH reduced SSB induction, but not DSBs. In conclusion, the FLASH effect with 27.5 MeV protons may not be sufficient in reducing complex/clustered DNA damage, which become the main cause of lethality. On the other hand, SSBs are relatively easily repaired compared to DSBs in the living cells, thus the FLASH effect would be effective in reducing the non-lethal damage that may lead to late effects, such as cell senescence, genomic instability and cell transformation. Moreover, further investigation on the changes in the types DNA damages with parameters such as higher dose rate, proton energy and oxygen pressure will be necessary to clarify the underlying physical and chemical process resulting the biological effect by proton-FLASH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express our thanks to the staff of Cyclotron operation section of National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Japan for technical support throughout the beam times.

Contributor Information

Daisuke Ohsawa, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Yota Hiroyama, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan; Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hirosaki University, 66-1 Hommachi, Hirosaki-shi, Aomori, 036-8564, Japan.

Alisa Kobayashi, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan; Electrostatic Accelerator Operation Section, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Tamon Kusumoto, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan; Radiation Measurement Research Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Hisashi Kitamura, Radiation Measurement Research Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Satoru Hojo, Cyclotron Operation Section, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Satoshi Kodaira, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan; Radiation Measurement Research Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan.

Teruaki Konishi, Single Cell Radiation Biology Group, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology; 4-9-1 Anagawa, Inageku, Chiba, 263-8555, Japan; Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hirosaki University, 66-1 Hommachi, Hirosaki-shi, Aomori, 036-8564, Japan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (Grant number JP 20H03634 & JP 21H02874).

References

- 1. Favaudon V, Lentz J-M, Heinrich S et al. Time-resolved dosimetry of pulsed electron beams in very high dose-rate, FLASH irradiation for radiotherapy preclinical studies. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2019;944:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lohse, I, Lang, S, Hrbacek, J et al. Effect of high dose per pulse flattening filter-free beams on cancer cell survival. Radiother Oncol 2011;101:226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Favaudon, V, Caplier, L, Monceau, V et al. Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:245–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durante, M, Bräuer-Krisch, E, Hill, M. Faster and safer? FLASH ultra-high dose rate in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol 2017;91:20170628. 10.1259/bjr.20170628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hughes, JR, Parsons, JL. FLASH radiotherapy: current knowledge and future insights using proton-beam therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourhis J, Montay-Gruel P, Goncalves Jorge P et al. Clinical translation of FLASH radiotherapy: why and how? Radiother Oncol 2019;139:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao, R, Ogurek, S, Sertorio, M et al. Comparison of FLASH vs conventional dose rate proton radiation in endogenous mouse brain tumor model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:e742. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berry, RJ, Hall, EJ, Forster, DW et al. Survival of mammalian cells exposed to X rays at ultra-high dose-rates. Br J Radiol 1969;42:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fouillade, C, Curras-Alonso, S, Giuranno, L et al. FLASH irradiation spares lung progenitor cells and limits the incidence of radio-induced senescence. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:1497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Labarbe R, Hotoiu L, Barbier J et al. A physicochemical model of reaction kinetics supports peroxyl radical recombination as the main determinant of the FLASH effect. Radiother Oncol 2020;153:303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson JD, Hammond EM, Higgins GS et al. Ultra-high dose rate (FLASH) radiotherapy: silver bullet or Fool's gold? Front Oncol 2019;9:1563. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adrian, G, Konradsson, E, Lempart, M et al. The FLASH effect depends on oxygen concentration. Br J Radiol 2020;93:20190702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin JY, Gu A, Wang W et al. Ultra-high dose rate effect on circulating immune cells: a potential mechanism for FLASH effect? Radiother Oncol 2020;149:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Marlen P, Dahele M, Folkerts M et al. Bringing FLASH to the clinic: treatment planning considerations for ultrahigh dose-rate proton beams. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;106:621–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buonanno M, Grilj V, Brenner DJ. Biological effects in normal cells exposed to FLASH dose rate protons. Radiother Oncol 2019;139:51–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kamada, T, Tsujii, H, Blakely, EA et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy in Japan: an assessment of 20 years of clinical experience. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luhr A, von Neubeck C, Krause M et al. Relative biological effectiveness in proton beam therapy - current knowledge and future challenges. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2018;9:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kanemoto, A, Hirayama, R, Moritake, T et al. RBE and OER within the spread-out Bragg peak for proton beam therapy: in vitro study at the proton medical research Center at the University of Tsukuba. J Radiat Res 2014;55:1028–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paganetti H, Beltran CJ, Both S et al. Roadmap: proton therapy physics and biology. Phys Med Biol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicholas, WC, Edouard, IA. The importance and clinical implications of FLASH ultra-high dose-rate studies for proton and heavy ion radiotherapy. Radiat Res 2019;193:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maxim, PG, Keall, P, Cai, J. FLASH radiotherapy: newsflash or flash in the pan? Med Phys 2019;46:4287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kusumoto, T, Kitamura, H, Hojo, S et al. Significant changes in yields of 7-hydroxy-coumarin-3-carboxylic acid produced under FLASH radiotherapy conditions. RSC Adv 2020;10:38709–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boscolo, D, Kramer, M, Fuss, MC et al. Impact of target oxygenation on the chemical track evolution of ion and electron radiation. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanazawa, A, Hojo, S, Sugiura, A et al. Present operational status of NIRS cyclotrons. In: 19th Internatinal Conference on Cyclotrons and their Applications, Lazhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ziegler JF, Ziegler MD, Biersack JP. SRIM – the stopping and range of ions in matter. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2010;268:1818–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanai, R, Yazu, M, Hieda, K. On the experimental distinction between SSBS and DSBS in circular DNA. Int J Radiat Biol 1998;73:475–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maeda, M, Kobayashi, K, Hieda, K. Efficiencies of induction of DNA double strand breaks in solution by photoabsorption at phosphorus and platinum. Int J Radiat Biol 2004;80:841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lloyd, RS, Haidle, CW, Robberson, DL. Bleomycin-specific fragmentation of double-stranded DNA. Biochemistry 1978;17:1890–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Povirk, LF, Wubter, W, Kohnlein, W et al. DNA double-strand breaks and alkali-labile bonds produced by bleomycin. Nucleic Acids Res 1977;4:3573–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeyama, T, Yamashita, S, Baldacchino, G et al. Production of a fluorescence probe in ion-beam radiolysis of aqueous coumarin-3-carboxylic acid solution—1: beam quality and concentration dependences. Radiat Phys Chem 2011;80:535–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prise, KM, Pullar, CH, Michael, BD. A study of endonuclease III-sensitive sites in irradiated DNA: detection of alpha-particle-induced oxidative damage. Carcinogenesis 1999;20:905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khosravifarsani, M, Shabestani-Monfared, A, Pouramir, M et al. Hydroxyl radical (°OH) scavenger power of Tris (hydroxymethyl) compared to phosphate buffer. J Mol Biol Res 2016;6:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hicks M, Gebicki JM. Rate constants for reaction of hydroxyl radicals with Tris. Tricine and Hepes buffers. FEBS Lett 1986;199:92–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oommen IK, Sengupta S, Krishnamurthy MV et al. ESR and lyoluminescence measurements on Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 1985;240:406–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roush, AE, Riaz, M, Misra, SK et al. Intrinsic buffer hydroxyl radical dosimetry using Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2020;31:169–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar, A, Becker, D, Adhikary, A et al. Reaction of electrons with DNA: radiation damage to radiosensitization. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3998. 10.3390/ijms20163998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kusumoto T, Barillon R, Yamauchi T. Application of radial electron fluence around ion tracks for the description of track response data of polyethylene terephthalate as a polymeric nuclear track detector. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2019;461:260–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kusumoto, T, Ogawara, R, Igawa, K et al. Scaling parameter of the lethal effect of mammalian cells based on radiation-induced OH radicals: effectiveness of direct action in radiation therapy. J Radiat Res 2021;62:86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Furusawa Y, Fukutsu K, Aoki M et al. Inactivation of aerobic and hypoxic cells from three different cell lines by accelerated (3)he-, (12)C- and (20)ne-ion beams. Radiat Res 2000;154:485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hada, M, Georgakilas, AG. Formation of clustered DNA damage after high-LET irradiation: a review. J Radiat Res 2008;49(3):203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tokuyama, Y, Furusawa, Y, Ide, H et al. Role of isolated and clustered DNA damage and the post-irradiating repair process in the effects of heavy ion beam irradiation. J Radiat Res 2015;56:446–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ward JF. The complexity of DNA damage: relevance to biological consequences. Int J Radiat Biol 1994;66:427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sutherland, BM, Bennett, PV, Sidorkina, O et al. Clustered damages and total lesions induced in DNA by ionizing radiation: oxidized bases and strand breaks. Biochemistry 2000;39:8026–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.