Abstract

Background

Young children with neurodisability commonly experience eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties (EDSD). Little is documented about which interventions and outcomes are most appropriate for such children. We aimed to seek consensus between parents of children with neurodisability and health professionals on the appropriate interventions and outcomes to inform future clinical developments and research studies.

Methods

Two populations were sampled: parents of children aged up to 12 years with neurodisability who experienced EDSD; health professionals working with children and young people (aged 0–18 years) with neurodisability with experience of EDSD. Participants had taken part in a previous national survey and were invited to take part in a Delphi survey and/or consultation workshops. Two rounds of this Delphi survey sought agreement on the appropriate interventions and outcomes for use with children with neurodisability and EDSD. Two stakeholder consultation workshops were iterative, with the findings of the first discussed at the second, and conclusions reached.

Results

A total of 105 parents and 105 health professionals took part. Parents and health professionals viewed 19 interventions and 10 outcomes as essential. Interventions related to improvement in the physical aspects of a child’s EDSD, behavioural changes of the child or parent, and changes in the child or family’s well-being. Both parents and health professionals supported a ‘toolkit’ of interventions that they could use together in shared decision making to prioritise and implement timely interventions appropriate to the child.

Conclusions

This study identified interventions viewed as essential to consider for improving EDSD in children with neurodisability. It also identified several key outcomes that are valued by parents and health professionals. The Focus on Early Eating, Drinking and Swallowing (FEEDS) Toolkit of interventions to improve EDSD in children with neurodisability has been developed and now requires evaluation regarding its use and effectiveness.

Keywords: Neurodisability, Neurology, Therapeutics, Growth, Health services research

What is known about the subject?

Children with neurodisability commonly experience eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties (EDSD) that have physical and non-physical causes.

EDSD have a considerable impact on a child and family.

A UK survey found a wide range of parent-delivered interventions are recommended by health professionals and used by parents to support young children with neurodisability.

What this study adds?

Agreement from parents and health professionals on the appropriate interventions and outcomes for use with children with neurodisability and EDSD.

Clarity on the interventions and outcomes to focus on within future research.

A toolkit of interventions was developed for use by health professionals and parents to support children with neurodisability and EDSD.

Introduction

Long-term conditions affecting the brain, nerves and muscles are often grouped under the term ‘neurodisability’.1 Children with neurodisability commonly experience eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties (EDSDs) that have physical and non-physical causes. Physical causes relate to decreased muscle control and coordination, which impairs the safety and efficiency of sucking, chewing and swallowing. Non-physical causes include rigidity or rituals associated with food or mealtimes, and sensory sensitivities to certain textures or flavours; this includes children with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Physical and non-physical EDSD frequently coexist (mixed EDSDs). EDSD makes mealtimes stressful for children and their families and impact negatively on quality of life and social participation. They also lead to inadequate calorie intake or a restricted diet, affecting a child’s nutrition, growth and physical health.2

A recent UK survey of parents and health professionals found a wide range of interventions were used for children with neurodisability who experience EDSD to address their physiological and behavioural needs.3 The survey found most children received multiple interventions. There was a common approach to addressing EDSD regardless of the cause of the child’s difficulties, with the majority of interventions being used to address all types of EDSD. This survey also identified a range of important outcomes to measure the effectiveness of interventions.

As part of a larger research programme, FEEDS (Focus on Early Eating, Drinking and Swallowing),4 this study aimed to:

Seek consensus between parents and health professionals on which interventions and outcomes are most appropriate for children with neurodisability and EDSD.

Gain consensus between parents of children with neurodisability and health professionals on which interventions should be evaluated in future research.

Develop a ‘toolkit’ of interventions that could be used by health professionals and parents to support children with EDSD and their families.

Methods

An iterative online Delphi survey and two stakeholder consultation workshops were undertaken.

Delphi survey

Participants

Invitations to participate were sent to respondents from the FEEDS national survey3 who had expressed interest in subsequent research stages. This included: parents of children (aged up to 12 years) with neurodisability who experienced EDSD; and health professionals working with children and young people (aged 0–18 years) with neurodisability. Participants were recruited through a wide range of sources, including the National Health Service (NHS), professional and parent networks and schools. Full recruitment strategies are outlined elsewhere4

Measure

The questionnaire listed interventions and outcomes identified in earlier stages of the FEEDS research programme,4 comprising updates of three systematic reviews,5–7 a mapping review, a national survey and focus groups. The questionnaire’s structure and format was developed with reference to methodological recommendations8 and previous experience of Delphi surveys. The questionnaire contained three sections: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) parent-delivered interventions for young children with neurodisability and EDSD; and (3) outcomes to measure improvement in EDSD.

Questions related to 25 interventions and 22 outcomes (tables 1 and 2). Respondents rated the importance of the interventions as part of a treatment package for EDSD, and the outcomes to measure (using a 9-point scale: 0–3 ‘not important’, 4–6 ‘important but not essential’, 7–9 ‘essential’). Respondents could tick ‘unable to score’. The questionnaire was hosted on Qualtrics.9

Table 1.

Description of interventions presented in Delphi survey

| Intervention | Description |

| Modifying environment | Changing the physical or social setting at mealtimes (eg, reducing distractions such as levels of noise; using distractions to reduce a child’s attention on their food. |

| Positioning | Ensuring a child is in the best position to eat and drink food safely and efficiently (eg, a child sitting upright providing support for head control). |

| Modifying equipment | Using different spoons, forks, plates, cups, or bottles (eg, doidy cup; plastic spoon). |

| Scheduling of meals | Setting the timing of mealtimes to encourage a child’s appetite and establish a mealtime routine (eg, spreading meals/snacks throughout the day; setting a 30 min limit for mealtimes). |

| Modifying consistency of food | Changing the consistency of the child’s food or drink (eg, pureeing food; thickening food or drink). |

| Modifying other aspects of food | Changing the temperature, taste, amount or presentation of the child’s food or drink (eg, presenting different foods so they do not touch each other; mixing liked foods with disliked foods). |

| Modifying placement of food | Changing where food is placed in a child’s mouth to help chewing or swallowing (eg, placing food to the side of the mouth). |

| Enhancing communication | Improving communication between a child and the person feeding them during mealtimes (eg, offering choices of food to a child; a child using eye pointing or signs or symbols to ask for specific food or drink). |

| Visual supports | Use of pictures, a ‘countdown clock’, or social stories to increase a child’s understanding of what happens during mealtimes (eg, showing a child pictures of what food will be on their plate; showing a child a story to explain what will happen during a mealtime). |

| Responding to a child’s cues for feeding | Helping people to recognise the signs that a child is ready to take another mouthful of food or drink (eg, looking for breath alterations or repeated swallows from a child to indicate a lack of readiness). |

| Pace of feeding | Changing the speed at which each mouthful of food or drink is taken by a child (eg, slowing pace down to prevent overfilling of a child’s mouth). |

| Medication | Any medication (eg, for epilepsy, pain, drooling, tone, gastro-oesophageal reflux). |

| Energy supplements | Any energy or calorie supplement given orally or via feeding tube. |

| Vitamin or nutritional supplements | Any supplements given or changes to a child’s diet to increase the vitamins or nutrients in their diet. |

| Physical support | Giving direct physical support to a child when eating or drinking to improve the movements needed to bite, chew and swallow (eg, placing a thumb underneath the chin to help a child close their mouth). |

| Oral and sensory desensitisation | Activities aimed at reducing a child’s adverse reactions to different sensory experiences linked to eating and drinking (eg, face massage; chewing no-food items such as a chewy ‘toothbrush’). |

| Oral-motor exercises | Exercises done with a child to improve the control of their mouth, jaw, tongue or lips (eg, a child moving a non-food item with their tongue; a child sucking through a straw). |

| Graded exposure to new food | Activities aimed at gradually exposing a child to new or disliked foods and drinks (eg, messy play activities involving a child touching new or disliked foods; using small steps towards a child accepting new or disliked foods such as licking the food or putting it in their mouth with no expectation to swallow). |

| Graded exposure to new textures | Activities aimed at gradually introducing a child to more challenging food textures and fluid consistencies (eg, messy play activities involving a child touching new or disliked textures; using small steps to introduce a child to lumpy food or foods that require chewing). |

| Changing behaviour at mealtimes | Strategies to encourage a child to behave appropriately at mealtimes (eg, a child sitting down ready to eat; a child staying seated for the meal). |

| Modelling | Giving a child the opportunity to learn from others by eating and drinking with them (eg, sitting a child with other children or family members at mealtimes). |

| Training to self-feed | Teaching a child to feed themselves (eg, placing a hand over a child’s hand to help guide the food into their mouth). |

| Support for parents | Help for parents around their child’s eating and drinking difficulties (eg, counselling; parent support groups). |

| Sharing information | Any information shared to help parents and professional understand a child’s difficulties with eating and drinking (eg, professionals teaching parents and school staff about a child’s physical or sensory difficulties; parents helping professionals understand what’s important about mealtimes in their family). |

| Psychological support for children | Psychological help for a child (eg, counselling). |

Table 2.

Description of outcomes presented in Delphi survey

| Outcome | Description |

| General health | A child’s overall health |

| Weight | How much a child weighs |

| Height | How tall a child is |

| Growth | A change in a child’s growth, including height and weight |

| Nutrition | A child’s level of energy and nutrients for healthy growth |

| Child’s enjoyment of mealtimes | |

| Parent or caregiver’s enjoyment of mealtimes | |

| Quality of life of child | How satisfied a child feels about their life |

| Quality of life of family | How satisfied other family members feel about their (own) lives |

| Mental health of parent or caregiver | A parent/caregiver’s mood and emotional well-being |

| Safety | A child’s ability to eat and drink safely without choking or aspirating |

| Oral motor control | A child’s ability to control the movement of their mouth, jaw, tongue or lips and swallow |

| Efficiency | A child’s ability to eat and drink at a reasonable pace |

| Independence | A child’s ability to feed themselves |

| Variety | The range of foods or liquids a child eats or drinks |

| Amount | The amount of food or liquid a child eats or drinks per day |

| Appetite | A child’s level of hunger and desire for food/drink |

| Mealtime behaviour | A child behaving appropriately during meals |

| Mealtime interaction | The interaction between a child and the person feeding them at mealtimes |

| Social participation | A child’s overall involvement at mealtimes |

| Child’s understanding | A child’s understanding of mealtime activities and routines |

| Parent or caregiver’s understanding | A parent/caregiver’s insight into their child’s eating and drinking difficulties |

Patient and public involvement

The questionnaire and information sheet were developed by the research team, which included parent co-investigators, in consultation with the Parent Advisory Group (PAG) and following focus groups with parents and health professionals.4

Procedure

The same questionnaire was sent to parents and health professionals in two rounds. In round 1, respondents rated the importance of individual intervention categories, and outcomes. In round 2, respondents were shown bar charts of parent and health professionals’ ratings from round 1 and then re-rated the importance of each intervention and outcome. No items were removed between rounds. Both survey rounds were open for 3 weeks with a week between the rounds for data analysis. Respondents and non-respondents from round 1 were invited to take part in round 2, to maximise participation. Round 2 respondents entered a prize draw to win one of five £100 vouchers for each stakeholder group.

Analysis

Consensus was conservatively defined as ≥67% and required each stakeholder group to rate an intervention or outcome as essential (rated 7–9 at round 2).8

Stakeholder workshops

Participants

Parents who took part in the FEEDS national survey3 and had expressed interest in subsequent research stages were invited to participate. Participants had to be able to travel to North East and South East England for the workshops. Invitations were sent to health professionals linked to regional and national clinical networks. Participants were purposively selected to maximise variation in their experience of EDSD and service provision.

Design

Two half-day workshops were held (Newcastle upon Tyne and London). The workshops aimed to facilitate detailed discussion on (1) Which interventions and outcomes should be evaluated in future research?; (2) A proposed intervention ‘toolkit’ for EDSD (developed during previous study stages), including: How could the essential interventions identified in the Delphi survey be presented to parents as a list of treatment options?; What level of detail would parents need on each intervention?; How would a menu of treatment options be individualised?; What level of support would families need from health professionals to use the toolkit?

Patient and public involvement

Parent co-investigators were involved in the design and delivery of the workshops. The PAG also reviewed workshop materials and commented on the structure and timings of tasks.

Procedure

Attendees were presented with a study overview including the main findings from earlier research stages. Individual topics were discussed in small mixed groups of parents and professionals. One research team member facilitated each group and notes were taken. The workshops were iterative, with the results of the first workshop being presented at the second. To thank them for their time and/or cover travel costs, parents and professionals received a shopping voucher.

Notes from the workshop discussions were reviewed by members of the research team and key themes identified; themes were then discussed by the full research team. For further details, see Parr et al.4

Results

Delphi survey

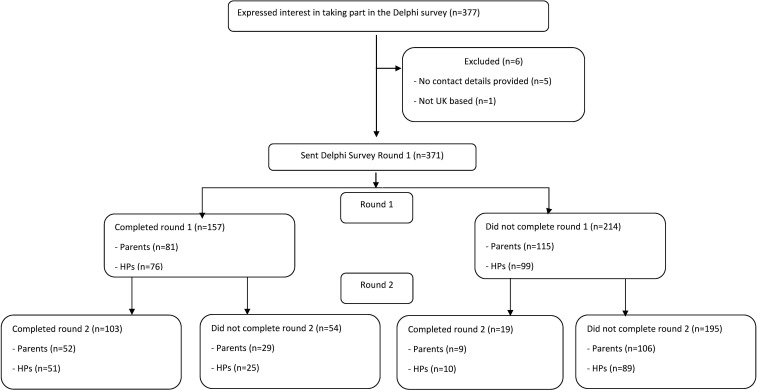

A total of 196 parents and 175 health professionals were invited (see figure 1). Eighty-one parents (41%) and 61 parents (31%) responded to rounds 1 and 2 respectively, with 52 parents responding to both rounds. Seventy-six health professionals (43%) and 61 health professionals (35%) responded to rounds 1 and 2 respectively, with 51 health professionals responding to both rounds.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of Delphi Survey recruitment. HPs, health professionals.

Participant characteristics

The characteristics of respondents are shown in table 3. Similar proportions of parents and health professionals participated in round 1 (49% and 51%, respectively), and round 2 (50% and 50%, respectively). The characteristics of respondents who completed both rounds and those who completed round 2 only were very similar. See online supplemental tables 1 and 2 for full details of respondents and non-respondents.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Delphi survey respondents for rounds 1 and 2

| Round 1 N=158 | Round 2 N=123 | |||

| Parents N=81 n (%) |

HPs N=76 n (%) |

Parents N=61 n (%) |

HPs N=61 n (%) |

|

| Age* | ||||

| Under 20 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 21–30 years | 2 (3) | 8 (11) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) |

| 31–40 years | 32 (40) | 19 (25) | 23 (38) | 17 (28) |

| 41–50 years | 40 (49) | 25 (33) | 32 (53) | 20 (33) |

| 51–60 years | 7 (9) | 22 (29) | 4 (7) | 20 (33) |

| 61 years and over | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Gender* | ||||

| Female | 76 (94) | 71 (93) | 58 (95) | 58 (95) |

| Male | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Location | ||||

| England | ||||

| North East | 14 (17) | 5 (7) | 11 (18) | 7 (12) |

| North West | 8 (10) | 3 (4) | 6 (10) | 3 (5) |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 5 (6) | 10 (13) | 2 (3) | 9 (15) |

| Midlands | 11 (14) | 16 (21) | 9 (14) | 10 (16) |

| South East including London | 27 (33) | 26 (34) | 20 (33) | 21 (34) |

| South West | 8 (10) | 8 (11) | 7 (12) | 4 (7) |

| Scotland | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (8) |

| Northern Ireland | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Wales | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Missing | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity* | ||||

| White | 78 (96) | 70 (92) | 59 (97) | 55 (90) |

| Asian/Asian British | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic group | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Other ethnic group | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nature of child’s EDSD | ||||

| Physical EDSD | 14 (17) | 14 (18) | 9 (15) | 13 (21) |

| Nonphysical EDSD | 40 (49) | 5 (7) | 32 (53) | 3 (5) |

| Mixed EDSD | 27 (33) | 57 (75) | 20 (33) | 45 (74) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

*No missing data.

EDSD, eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties; HPs, health professionals.

bmjpo-2022-001425supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp002.pdf (82.5KB, pdf)

Interventions for children with neurodisability and EDSD

Table 4 shows the proportion of parents and health professionals who rated interventions as essential in rounds 1 and 2. Consensus was achieved for 17/25 interventions at round 1, increasing to 19/25 interventions at round 2. The interventions rated as an essential part of an intervention package for young children with neurodisability and EDSD are shown in table 4. See online supplemental tables 3 and 4 for all intervention ratings.

Table 4.

Parents’ and health professionals’ rating of interventions as essential on round 1 and 2 of the Delphi survey

| Intervention | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| Parents N=81 % |

Health professionals N=76 % |

Parents N=61 % |

Health professionals N=61 % |

|

| Modifying environment | 67 | 87 | 77 | 95 |

| Positioning | 92 | 97 | 96 | 100 |

| Modifying equipment | 76 | 87 | 93 | 90 |

| Scheduling of meals | 53 | 82 | 50 | 83 |

| Modifying consistency of food or drink | 79 | 86 | 79 | 96 |

| Modifying other aspects of food or drink | 74 | 75 | 86 | 83 |

| Modifying placement of food | 68 | 79 | 75 | 90 |

| Enhancing communication | 76 | 82 | 86 | 90 |

| Visual supports | 52 | 63 | 52 | 72 |

| Responding to a child’s cues for feeding | 83 | 94 | 93 | 96 |

| Pace of feeding | 77 | 96 | 89 | 100 |

| Physical support | 72 | 69 | 82 | 81 |

| Oral and sensory desensitisation | 72 | 68 | 82 | 75 |

| Oral-motor exercises | 73 | 40 | 70 | 35 |

| Graded exposure to new food | 66 | 85 | 70 | 84 |

| Graded exposure to new textures | 68 | 81 | 76 | 81 |

| Changing behaviour at mealtimes | 57 | 63 | 58 | 56 |

| Modelling | 80 | 82 | 77 | 83 |

| Training to self-feed | 68 | 47 | 55 | 46 |

| Support for parents | 81 | 84 | 95 | 96 |

| Psychological support for child | 72 | 63 | 77 | 59 |

| Medication | 78 | 86 | 87 | 91 |

| Energy supplements | 62 | 74 | 69 | 73 |

| Sharing information | 90 | 95 | 100 | 97 |

| Vitamin or nutritional supplements | 68 | 68 | 85 | 75 |

Bold values denote a rating of 'essential' (score 7-9) by ≥67% within the stakeholder group. Shaded grey cells denote agreement by both stakeholder groups that the item was 'essential' (score 7-9) ≥67%.

bmjpo-2022-001425supp003.pdf (112.6KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp004.pdf (111.9KB, pdf)

Outcomes for children with neurodisability and EDSD

Table 5 shows the proportions of parents and health professionals who rated outcomes as essential in rounds 1 and 2. The outcomes for which there was consensus on did not change between rounds. 10 outcomes were viewed as essential; some related to physical health, such as safety and growth, and others to the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health, such as child social participation. See online supplemental tables 5 and 6 for all outcome ratings.

Table 5.

Parents' and health professionals' agreement on outcomes rated as essential on round 1 and round 2 of the Delphi survey

| Outcome | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| Parents N=81 |

Health professionals N=76 |

Parents N=61 |

Health professionals N=61 |

|

| Nutrition | 89 | 97 | 95 | 98 |

| General health | 89 | 93 | 97 | 98 |

| Weight | 53 | 51 | 34 | 48 |

| Height | 31 | 32 | 12 | 12 |

| Growth | 75 | 76 | 82 | 89 |

| Child’s enjoyment of mealtimes | 83 | 91 | 90 | 98 |

| Parent’s enjoyment of mealtimes | 42 | 76 | 39 | 78 |

| Quality of life of child | 95 | 92 | 98 | 100 |

| Quality of life of family | 78 | 87 | 90 | 97 |

| Mental health of parent | 83 | 84 | 93 | 97 |

| Safety | 97 | 97 | 100 | 100 |

| Oral-motor control | 87 | 74 | 86 | 72 |

| Efficiency | 44 | 60 | 17 | 46 |

| Independence | 60 | 31 | 43 | 28 |

| Variety | 51 | 23 | 26 | 12 |

| Amount | 62 | 40 | 53 | 25 |

| Appetite | 59 | 44 | 46 | 38 |

| Mealtime behaviour | 41 | 30 | 34 | 26 |

| Mealtime interaction | 61 | 81 | 65 | 79 |

| Social participation | 50 | 77 | 53 | 74 |

| Parent’s understanding of child’s EDSD | 89 | 89 | 95 | 93 |

| Child’s understanding of mealtimes | 51 | 51 | 58 | 40 |

Bold values denote a rating of 'essential' (score 7-9) by ≥67% within the stakeholder group. Shaded grey cells denote agreement by both stakeholder groups that the item was 'essential' (score 7-9) ≥67%.

EDSD, eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties.

bmjpo-2022-001425supp005.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp006.pdf (111.7KB, pdf)

Stakeholder workshops

Fifteen parents and 19 health professionals took part in the workshops.

Participant characteristics

Nine parents had children with physical EDSD, two had children with non-physical EDSD, two had children with mixed EDSD and two had one child with physical EDSD and one child with non-physical EDSD. Health professionals comprised six speech and language therapists, four dietitians, four paediatricians, three occupational therapists, two clinical psychologists, a physiotherapist and a nurse.

Interventions and outcomes for evaluation in future research

Parents and health professionals agreed that no single intervention was suitable for all children with EDSD as many children require a number of interventions concurrently or sequentially. Both parents and health professionals endorsed the idea of an intervention ‘toolkit’ that could be used together to identify the most appropriate interventions for individual children and their families. They thought the toolkit should be visually represented and be available as a digital and hard copy with interactive properties to support communication between parents and professionals. They emphasised the need for flexibility in the toolkit to allow families and health professionals to select the most appropriate interventions, at the right time. Some parents thought they would want to be able to see the whole toolkit, to facilitate a central parental role in intervention prioritisation. Parents and health professionals thought that detailed information was needed for each intervention to fully inform families and allow them to share in decision-making.

Paricipants thought a lead health professional (such as a speech and language therapist) and multidisciplinary team should support families in their toolkit use. The nature of support needed would vary between families and may include psychological input. Parents and health professionals raised a number of practical issues about toolkit use, including: how to deliver the toolkit to meet the needs of a heterogeneous population with diverse EDSD; how to deliver the toolkit where multidisciplinary EDSD team professionals are unavailable or under-resourced; and how to deliver the toolkit to children with non-physical EDSD who may not currently receive multidisciplinary team healthcare.

Toolkit of interventions for children with neurodisability and EDSD

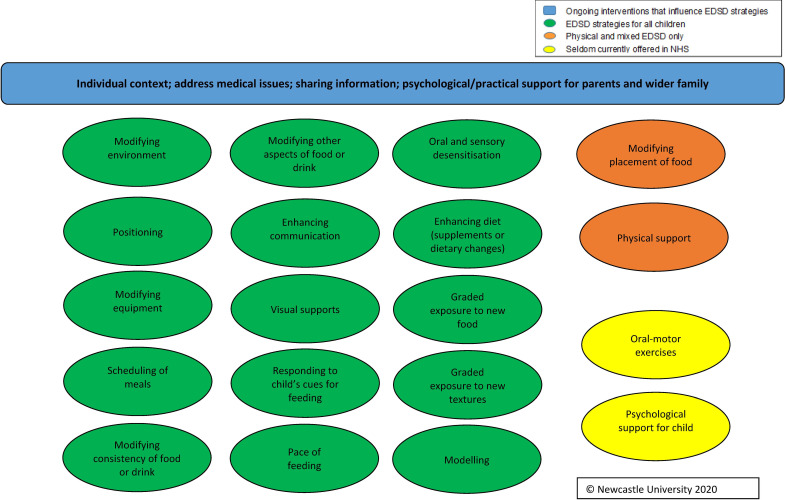

Using the findings from the Delphi survey and workshops, alongside findings from other stages of the FEEDS research programme,4 we developed the FEEDS Toolkit of interventions for use by health professionals and parents to support children with neurodisability and EDSD (see figure 2). The FEEDS Toolkit comprises 19 EDSD interventions: 15 for use with children with all types of EDSD, two for use with children with physical or mixed EDSD only and two that are rarely offered by the UK NHS (oral motor excercises and psychological support for the child). The FEEDS Toolkit also includes ongoing interventions that influence EDSD strategies such as individual context, medical issues and sharing information.

Figure 2.

Outline of FEEDS Toolkit of interventions. EDSD, eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties; FEEDS, Focus on Early Eating, Drinking and Swallowing; NHS, National Health Service.

Discussion

The Delphi survey established consensus on the 19 essential interventions to include in the FEEDS Toolkit, and 10 outcomes of importance. The stakeholder workshops showed support from parents and health professionals for the FEEDS Toolkit that could be worked through by health professionals and parents. Rather than evaluating single standalone interventions, we suggest that future research should evaluate a combination of interventions within the FEEDS Toolkit.

The large number and diversity of interventions identified as essential for inclusion in the toolkit reflects the heterogeneity of children with neurodisability and EDSD, and their families. Beresford et al10 found health professionals working with children with neurodisability had a ‘great big menu of interventions to choose from’ which were highly individualised. Health professionals talked about taking an eclectic approach and using a range of interventions from their toolbox with children with neurodisability and their families; key factors affecting decision making regarding appropriate interventions included child and family’s characteristics and resources.10 McAnuff et al11 described a prototype for an interactive toolkit to support families and health professionals to identify opportunities for change, and to jointly select appropriate interventions. This is in keeping with views regarding how the FEEDS toolkit might be operationalised.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge the potential risks of sampling and response bias. Participants from the FEEDS national survey were recruited from wide ranging sources4; their data allowed comparison of the characteristics of Delphi survey respondents and non-respondents. The overall response (≈40%) was acceptable. There was minimal difference between the characteristics of respondents between rounds 1 and 2. Through contacting non-respondents from round 1 in round 2 we increased round 2 responses thereby improving precision. We used a conservative consensus definition of ≥67%; our findings may have differed if we had used different consensus definitions.

The workshops had representation from two diverse geographical areas and parents and professionals with a broad range of EDSD experiences. The iterative nature of the workshops facilitated detailed discussions. Young people with EDSD were not invited to the workshops; however, at separate young people’s focus groups, they agreed the importance of the outcomes identified.4

Conclusions

The FEEDS Delphi survey and workshops identified the interventions essential to consider for improving EDSD in children with neurodisability. They also identified the most important outcomes to measure, focusing on both the child and the wider family. These findings, alongside findings from earlier stages of the FEEDS research programme4 have been used to develop a toolkit of interventions. The FEEDS Toolkit requires evaluation of its feasibility and acceptability, and its effectiveness for improving outcomes for children and families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants who gave their time to complete the Delphi survey and workshops. The Sponsor for the studies was Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Pen_CRU

Contributors: JP was chief investigator, co-led the design and delivery of the study, supervised the Delphi survey data analysis, co-led the consultation workshops and analysed the data. JP is guarantor for the overall study content. LP co-led the design and delivery of the project, co-led the consultation workshops and analysed the data. HT developed the Delphi survey materials, ran the Delphi survey and analysed the data, and co-led the consultation workshops. CM, JC, DS, JS, DG, JT and EM contributed to the design of the Delphi survey. CB, AC, DG, CM, HM, JS, JT, JC and DS co-facilitated the consultation workshops. All authors contributed to the study design, interpretation of results, writing of the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme (ref: 15/156/02). The NIHR HTA report from the research (including that reported in this manuscript) can be found at: https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta25220/%23/full-report

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: DS received a research grant from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition UK (Wiltshire, UK) from 2017 to 2018, honorarium payments from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition UK from 2015 to 2019 and an honorarium payment from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition UK in 2018. MA received fees from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition UK to attend a conference in which she was presenting industry partner research work and lecture fees/symposium presentation fees from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition UK and Nestlé SA (Vevey, Switzerland). JC reports personal fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) and Allergan, and Ispen Pharmaceuticals (Paris, France).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (JP).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by The West Midlands and the Black Country Research Ethics Committee (17/WM/0439). Completion of the Delphi survey was taken as informed consent and informed consent was taken at the start of the stakeholder workshops.

References

- 1.Morris C, Janssens A, Tomlinson R, et al. Towards a definition of neurodisability: a Delphi survey. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:1103–8. 10.1111/dmcn.12218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PB, Andersen GL, Andrew MJ, eds. Nutrition in neurodisability. London: Mac Keith Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor H, Pennington L, Craig D, et al. Children with neurodisability and feeding difficulties: a UK survey of parent-delivered interventions. BMJ Paediatr Open 2021;5:e001095. 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parr J, Pennington L, Taylor H, et al. Parent-delivered interventions used at home to improve eating, drinking and swallowing in children with neurodisability: the feeds mixed-methods study. Health Technol Assess 2021;25:1–208. 10.3310/hta25220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall J, Ware R, Ziviani J, et al. Efficacy of interventions to improve feeding difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:278–302. 10.1111/cch.12157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan AT, Dodrill P, Ward EC. Interventions for oropharyngeal dysphagia in children with neurological impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD009456. 10.1002/14651858.CD009456.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NICE . Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG62]. London: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000393. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qualtrics . Qualtrics. Utah, USA: Provo, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beresford B, Clarke S, Maddison J. Therapy interventions for children with neurodisabilities: a qualitative scoping study. Health Technol Assess 2018;22:1–150. 10.3310/hta22030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAnuff J, Brooks R, Duff C, et al. Improving participation outcomes and interventions in neurodisability: co-designing future research. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:298–306. 10.1111/cch.12414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjpo-2022-001425supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp002.pdf (82.5KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp003.pdf (112.6KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp004.pdf (111.9KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp005.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2022-001425supp006.pdf (111.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (JP).