Abstract

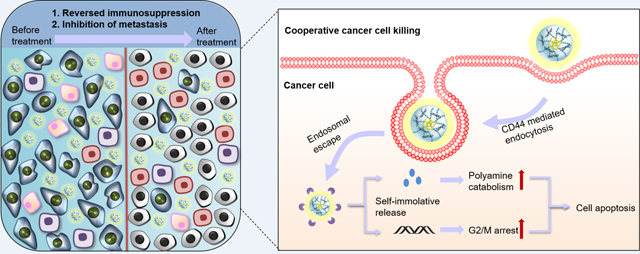

RNA interference (RNAi) is an emerging therapeutic modality for cancer, which remains in critical need of effective delivery vectors due to the unfavorable biopharmaceutical properties of small RNAs. Polyamines are essential for functioning of mammalian cells. Dysregulated polyamine metabolism is found in many cancers and has been an attractive therapeutic target in combination therapies. Combination therapies based on drugs that affect polyamine metabolism and nucleic acids promise to enhance anticancer activity due to a cooperative effect on multiple oncogenic pathways. Here, we report bioactive polycationic prodrug (F-PaP) based on an anticancer polyamine analog bisethylnorspermine (BENSpm) modified with perfluoroalkyl moieties. Following encapsulation of siRNA, F-PaP/siRNA nanoparticles were coated with hyaluronic acid (HA) to form ternary nanoparticles HA@F-PaP/siRNA. The presence of perfluoroalkyl moieties and HA reduced cell membrane toxicity and improved stability of the particles with cooperatively enhanced siRNA delivery in pancreatic and colon cancer cell lines. We then tested a therapeutic hypothesis that combining BENSpm with siRNA silencing of polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) would result in cooperative cancer cell killing. HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 induced polyamine catabolism and cell cycle arrest, leading to enhanced apoptosis in the tested cell lines. The HA-coated nanoparticles facilitated tumor accumulation and contributed to strong tumor inhibition and favorable modulation of the immune tumor microenvironment in orthotopic pancreatic cancer model.

Combination anticancer therapy with polyamine prodrug-mediated delivery of siRNA.

Hyaluronate coating of the siRNA nanoparticles facilitates selective accumulation in orthotopic pancreatic tumors.

Perfluoroalkyl conjugation reduces toxicity and improves gene silencing effect.

Nanoparticle treatment induces polyamine catabolism and cell cycle arrest leading to strong tumor inhibition and favorable modulation of immune tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: siRNA delivery, polyamines, perfluoroalkyls, hyaluronic acid, combination cancer therapy

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is an emerging therapeutic modality for the treatment of cancer.1 The clinical translation of the RNAi technology requires the development of effective delivery vectors due to unfavorable biopharmaceutical properties of small RNAs.2, 3 Despite the clinical success of RNAi in hepatic delivery, the ability to deliver RNA to distant tumors remains an area with the need for great improvement to maximize the clinical potential of RNAi.4 Delivery of RNAi agents such as small interfering RNA (siRNA) can be achieved by viral or non-viral vectors. The use of cationic non-viral vectors that utilize the advances in materials science and nanotechnology has been an attractive strategy due to their versatility and anticipated safety.5–7

Multiple strategies have been developed to improve siRNA delivery efficacy by non-viral vectors. Conjugation of hydrophobic moieties to polycations is a widely used method to improve the delivery efficacy due to enhanced adsorption to the cell membrane, favorable interactions with membrane that improve traversing across the lipid membrane and facilitation of nucleic acid dissociation from polycations.8–12 However, the interactions of the hydrophobic moieties with lipids and lipoproteins in serum and in non-target cell membranes may cause disruption of the polycation/siRNA nanoparticles (polyplexes) or non-specific cell membrane damage.10, 12 Although the functionalization of the polymers with hydrophobic moieties may improve the transfection efficiency and biocompatibility, the resulting materials have not been effective enough yet to be used clinically.13

Although absent in biological systems, fluorine is widely used in drug design. Fluorocarbons are both hydrophobic and lipophobic and exhibit high tendency for phase separation in both polar and non-polar environments. Despite low affinity of the fluorocarbons for hydrocarbons, amphiphilic fluorous compounds, such as perfluoroalkyl conjugated oligosaccharides, show high affinity to cell membranes.14 Introduction of perfluoroalkyl moieties has been explored as a way of improving transfection efficacy of gene and siRNA delivery systems by improving the ability of the nanoparticles to cross cell membranes and escape from endosomes to the cytoplasm.13, 15 Perfluoroalkylated polycations are also known to improve mucus penetration, serum stability, and biocompatibility.14, 16–19 Inspired by the unique features of the fluorine, conjugation of polycations with perfluoroalkyl group promises a safer and more efficient intracellular RNA delivery.17, 18, 20

The heterogeneity affecting key cancer pathways poses significant challenges for effective monotherapies.21–23 Polyamine metabolism is a suitable target for combination therapies because of its direct and indirect involvement in multiple oncogenic pathways that could be strategically explored to achieve synergistic effect with a broad range of chemotherapeutics. For example, inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) 2-difluoromethylornithine has been combined with several agents to improve therapeutic efficacy, including agents that improve antitumor immune response.24–27 Additionally, antitumor polyamine analogues have been combined with various therapies both in model systems and in clinical trials to increase antitumor activity, in many cases, as a result of tumor-specific increases in polyamine catabolism.28–32

The naturally occurring polyamines, putrescine, spermidine, and spermine are ubiquitously present in all human tissues and all cell types.33 Polyamines in mammalian cells are necessary for a wide range of cellular functions, including cell proliferation and apoptosis.34, 35 The polyamine concentrations are tightly controlled by key enzymes and the polyamine transport system.36 Multiple oncogenic pathways have been identified to contribute to the dysregulation of polyamine metabolism in cancer cells, leading to increased polyamine concentrations.37 Many compounds have been developed targeting polyamine metabolism to deplete the intracellular polyamines.38, 39 N1,N11-bis(ethyl)norspermine (BENSpm) is one of the most successful polyamine analogues that demonstrated excellent anticancer efficacy in multiple preclinical models, including colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer.40, 41 By inducing the expression of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SSAT) and spermine oxidase (SMOX), BENSpm downregulates polyamine biosynthesis and induces polyamine catabolism, which leads to a near-total polyamine depletion and apoptosis via the interactions with apoptosis protein regulators and generation of reactive oxygen species.40, 42–44 Unfortunately, even though BENSpm monotherapy was well tolerated in clinical trials, its efficacy as a single agent was underwhelming.45

In this study, we report polymeric prodrug based on BENSpm containing perfluoroalkyl moieties (F-PaP) as a drug/siRNA delivery system. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine threonine kinase required for regulation of mitosis that is overexpressed in many types of cancer, including colorectal and pancreatic cancers.46–48 The overexpression of PLK1 correlates with tumor progression and low survival rate, suggesting that silencing the PLK1 expression with siRNA (siPLK1) is a promising target for cancer therapy.49 Since both polyamines and PLK1 expression are necessary for tumor growth and progression, and because they represent two independent target pathways, there is a strong potential for synergy. We prepared F-PaP/siRNA nanoparticles and coated them with hyaluronic acid (HA) to improve compatibility and stability and achieve targeting to CD44.50, 51 We hypothesized that the HA-coated and fluoroalkyl-conjugated prodrug nanoparticles will effectively deliver both BENSpm and siPLK1 to achieve enhanced antitumor activity through co-operative apoptosis inducing effect on polyamine catabolism and PLK1 cell cycle arrest.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization HA@F-PaP/siRNA nanoparticles

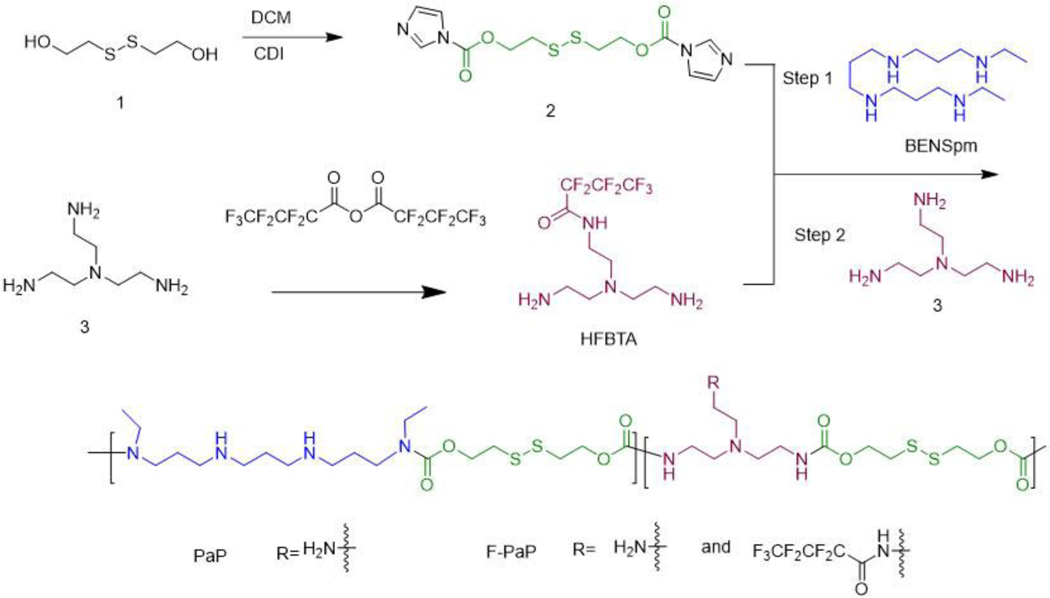

The presence of four secondary amines in BENSpm inspired us previously to design a polycationic BENSpm prodrug (PaP) for nucleic acid delivery.52, 53 In order to retain the pharmacological effect on polyamine metabolism in cancer cells, BENSpm has to be released in unmodified form from the polymeric prodrugs.54 To achieve the goal, we synthesized PaP using self-immolative disulfide linker which can readily release BENSpm upon reaction with intracellular glutathione (GSH).53 The original PaP design, however, was limited to intratumoral injection. To enhance the in vivo applicability of the PaP-based systems by controlling stability, safety, and improving overall siRNA delivery efficacy, we explored a strategy that relies on combining the introduction of perfluoroalkyl groups to the polymer structure with HA surface stabilization and targeting.

In prior studies, heptafluorobutyl (HFB) moiety provided beneficial effect on siRNA transfection efficacy in vitro 15, 55 and was thus used here to modify PaP to prepare F-PaP. While direct acylation of the secondary amines in BENSpm with heptafluorobutyric acid or anhydride would be the easiest approach, such strategy would lead to the formation of stable amide bonds between HFB and BENSpm, thus compromising the anticancer activity of the polyamine analogue.56 As an alternative, we modified tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (TAEA) (compound 3) with the HFB moiety (HFBTA) and used the compound to directly copolymerize with BENSpm during the step-growth polymerization (Scheme 1 and Figure S2). During the polymerization, BENSpm was reacted with excess bis(2-hydroxyethyl) disulfide (BHED), with its hydroxyl groups activated (compound 2) by carbonyl diimidazole (CDI). The compound 2 was characterized by 1H-NMR (Figure S2). Using 1H-NMR we monitored the reaction for the presence of unreacted carbonyl imidazole groups due to the lower reactivity of secondary amines in nucleophilic substitution compared with primary amines. The reaction was terminated when approximately half of the carbonyl imidazole groups reacted. TAEA and HFBTA were then added to the reaction mixture to deplete unreacted carbonyl imidazole groups. This way, we ensured that BENSpm was maximally incorporated into the polymer. Control PaP without HFB was also synthesized. The polymers were characterized by 1H- and 19F-NMR. We found 27 wt% and 30 wt% of BENSpm in PaP and F-PaP, respectively. The F-PaP contained 5.5 wt% of fluorine as quantified by 19F-NMR (Figure S1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PaP and F-PaP.

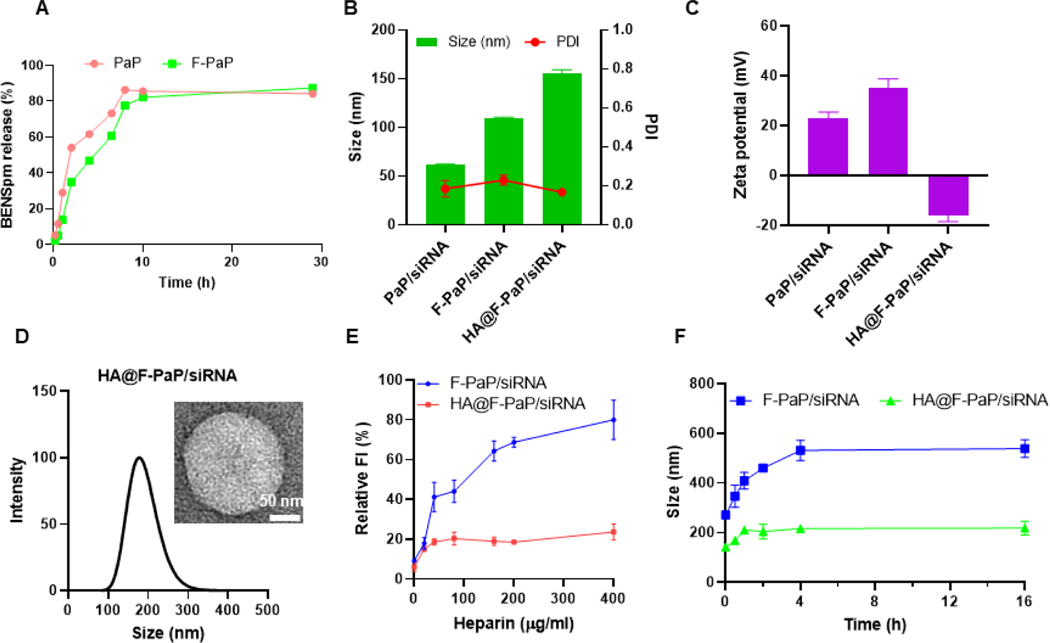

The PaP prodrug design relies on cleavage of the BHED disulfide linker in the presence of the elevated GSH levels in cancer cells. This exposes thiol in the linker, which then engages in intramolecular attack and cleavage of the carbamate group, releasing the free BENSpm.53 The release kinetics of BENSpm was evaluated by HPLC using dithiothreitol as the reducing agent as described previously.53, 57 Plotting the results as the percent BENSpm release against the degradation time indicated the degradation followed first-order kinetics with the rate constant 0.20 h−1 (half-life 3.5 h) for PaP and 0.17 h−1 (half-life 4.0 h) for F-PaP (Figure 1A). This suggested that the prodrug nature of F-PaP was preserved, and the presence of the HFB moieties had only minor slowing effect on the rate of disulfide cleavage.

Figure 1.

Characterization of HA@F-PaP/siRNA nanoparticles. (A) BENSpm release kinetics from PaP and F-PaP in 100 mM DTT. (B) Hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles. (C) Zeta-potential of nanoparticles. (D) Size distribution and TEM of HA@F-PaP/siRNA (HA/F-PaP/siRNA = 0.1/6/1). (E) Disassembly stability of the nanoparticles against polyanions. Nanoparticles were incubated with different concentrations of heparin for 30 min at 37 °C and released siRNA was quantified by SYBR fluorescence assay. (F) Colloidal stability of the nanoparticles in the presence of serum. Nanoparticles were incubated with 10% FBS at 37 °C and the hydrodynamic size was measured at different time points.

Binding of siRNA with the synthesized polymeric prodrugs was evaluated by a gel retardation assay. Both polymers (PaP and F-PaP) achieved complete binding of siRNA at polymer/siRNA w/w ratio of 4 and above (Figure S3A and S3B). Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential were measured by dynamic light scattering in 10 mM HEPES (pH = 7.4). Overall, the sizes of the nanoparticles ranged from 50 to 150 nm with strong positive zeta potential, suggesting successful encapsulation of siRNA. At w/w = 6, both polymers formed complexes with siRNA with spherical morphology (Figure S3D-I). Compared with PaP, F-PaP showed larger size probably due to its more hydrophobic character.

One strategy to stabilize cationic nanoparticles carriers is to coat them with anionic molecules. HA is a polyanionic polysaccharide which adsorbs to the cationic nanoparticles through electrostatic interactions.58 After coating with HA, the size of the particles showed a large increase at HA/F-PaP w/w ratio of 0.05, because insufficient amount of HA was causing particle aggregation by partially reduced surface charge and bridging-induced aggregation. However, when the ratio increased to w/w 0.1, more HA was coated onto the nanoparticles, resulting in stronger electrostatic repulsion and improved colloidal particle stability. The zeta potential reversed to negative values after coating with HA and remained stable above w/w = 0.2 indicating the nanoparticles were completely coated (Figure 1B-D Figure S4A, B). HA may engage in polyelectrolyte exchange reaction with the polyplexes and release free siRNA. Potential release of siRNA by HA was examined, but no adverse effect has been observed either by agarose gel analysis or using intercalating SYBR fluorescence assay (Figure S4C).

To confirm the improved stability, the nanoparticles were incubated in heparin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Coating the nanoparticles with HA improved their stability against heparin with only minor increase in the relative fluorescent intensity (FI) when incubated with 400 µg/mL heparin (Figure 1E). Serum contains negatively charged proteins like albumin that can bind with the cationic nanoparticles, leading to increased size and aggregation. The colloidal stability of the nanoparticles was evaluated in 10% FBS solution. F-PaP/siRNA and HA@F-PaP/siRNA showed different sizes the moment the FBS was added and the size of HA@F-PaP/siRNA was around 200 nm after 16 h incubation while F-PaP/siRNA increased to more than 500 nm (Figure 1F). Those results proved the improved stability after coating with HA.

The cleavage of the disulfide bond in the polymeric prodrugs not only releases BENSpm but also leads to the disintegration of the nanoparticles and release of the siRNA since free BENSpm cannot stably bind siRNA. To verify the release of the siRNA in reducing environment, the F-PaP/siRNA and PaP/siRNA particles were incubated with 20 mM GSH and as expected, we observed release of free siRNA (Figure S3C). Similar behavior was also observed with the HA-coated F-PaP/siRNA particles (Figure S5A). We also observed changes in the light scattering intensity, which was used as a measure of particle size and molecular weight during incubation with GSH. The scattering intensity decreased significantly, indicating the degradation of the polymeric prodrugs and disintegration of the nanoparticles (Figure S5B). TEM images showed swelling and loosening of the structure for remaining particles confirming successful degradation of HA@F-PaP/siRNA (Figure S5C).

Reduced non-specific toxicity and improved cellular uptake of F-PaP/siRNA

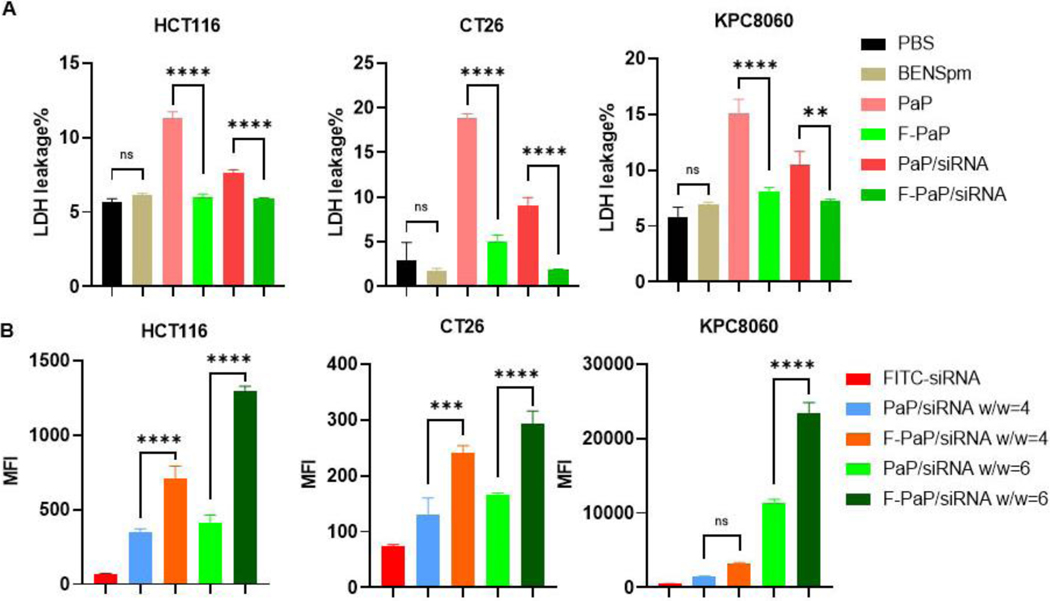

Cytotoxicity of polycations is related to several key factors, including number of charges, charge density, degradability, and hydrophobicity. By reducing the number of exposed positive charges, non-specific cell membrane damage by cationic polymers is reduced.11, 59 Cell viability of both polymers was evaluated in three cell lines by CellTiter-Blue assay. The cells were incubated with different concentrations and IC50 was calculated. The IC50 for F-PaP was 26.8 µg/mL in HCT116 cells, 22.4 µg/mL in CT26 cells, and 38.4 µg/mL in KPC8060 cells. PaP showed higher cytotoxicity with the corresponding IC50 values of 17.5, 15.9, and 26.5 µg/mL, respectively (Figure S6). We postulated that the improved safety of F-PaP is due to its reduced ability to perturb cell membranes. To confirm the hypothesis, we used LDH assay to evaluate acute membrane toxicity of the polycations. The three cell lines were incubated with the polymers using the same BENSpm equivalent concentration for 1 h, and LDH activity in the medium was quantified. As expected, BENSpm showed no membrane damage. PaP polymer and PaP/siNC polyplexes showed significant membrane damage as indicated by elevated LDH levels in the medium, when compared with the free F-PaP and F-PaP/siNC (Figure 2A). In HCT116, CT26 and KPC8060, PaP showed 10%−15% LDH release, while F-PaP showed only ∼5% LDH release.

Figure 2.

Cell membrane toxicity and siRNA cell uptake. (A) LDH levels in medium after treatment with different formulations (200 nM siNC) for 1 h. Results are normalized to the percentage of lysis buffer. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of intracellular FITC-siRNA (100 nM) after treatment for 4 h. All data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.

Recent studies showed that the presence of perfluoroalkyl moieties can greatly improve cellular siRNA delivery.13, 60 As shown in Figure 2B, F-PaP/siRNA prepared with fluorescently labeled siRNA showed about 2-fold increase in cell uptake when compared with PaP/siRNA in all three cell lines, validating the prior findings. F-PaP/siRNA prepared at w/w 6 showed higher uptake compared with w/w 4 and thus w/w 6 was selected for further studies. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was applied to visualize and further confirm the improved siRNA delivery. There was more Cy5.5-RNA (red) signal in the F-PaP/siRNA group in all three cell lines demonstrating improved cellular delivery efficacy (Figure S7).

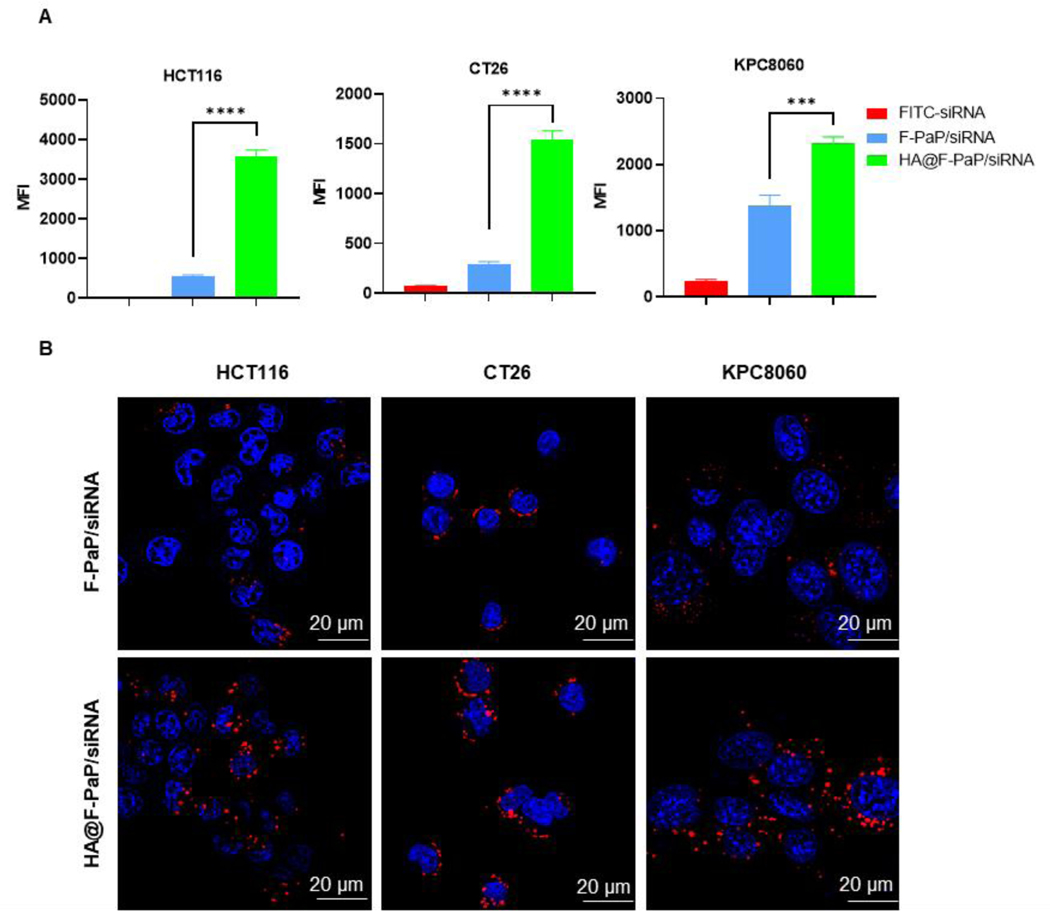

Enhanced siRNA delivery by HA@F-PaP/siRNA

Besides improved stability, HA has a high affinity for CD44 expressed on cancer cells, and thus can further improve the delivery efficacy of the coated nanoparticles.61 We first validated the CD44 expression by immunofluorescence staining and found high CD44 expression in all three cancer cell lines (Figure S8). Then, we optimized the amount of coating HA needed for achieving maximum cell uptake. At HA/F-PaP w/w = 0.1, the cellular uptake was 3-fold higher than at w/w = 0.2 and 30% higher than at w/w = 0.05 in HCT116 cells. This phenomenon indicated that at w/w = 0.05 HA did not fully coat the nanoparticle and increased HA would benefit the HA-mediated cell uptake. However, at w/w = 0.2, there likely was free HA present in the formulation that partially blocked the CD44 interactions to reduce cell uptake. Similar results were observed in CT26 cells (Figure S9A, B). Thus, w/w = 0.1 ratio was selected for further studies. HA@F-PaP/siRNA was readily taken up by HCT116, CT26 and KPC8060 cells, with the uptake significantly increased when compared with the non-coated cationic F-PaP/siRNA nanoparticles (Figure 3A). These results were further confirmed by CLSM as more siRNA (red) in the HA@F-PaP/siRNA group was observed in all cell lines (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cell uptake of nanoparticles. (A) Intracellular FITC-siRNA quantified by flow cytometry after treating cells with nanoparticles (100 nM) for 4 h. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. (B) Confocal microscopy images of cells treated with nanoparticles containing Cy5.5-siRNA (red) after 4 h treatment. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 µm.

Enhanced siPLK1 delivery by HA@F-PaP/siRNA

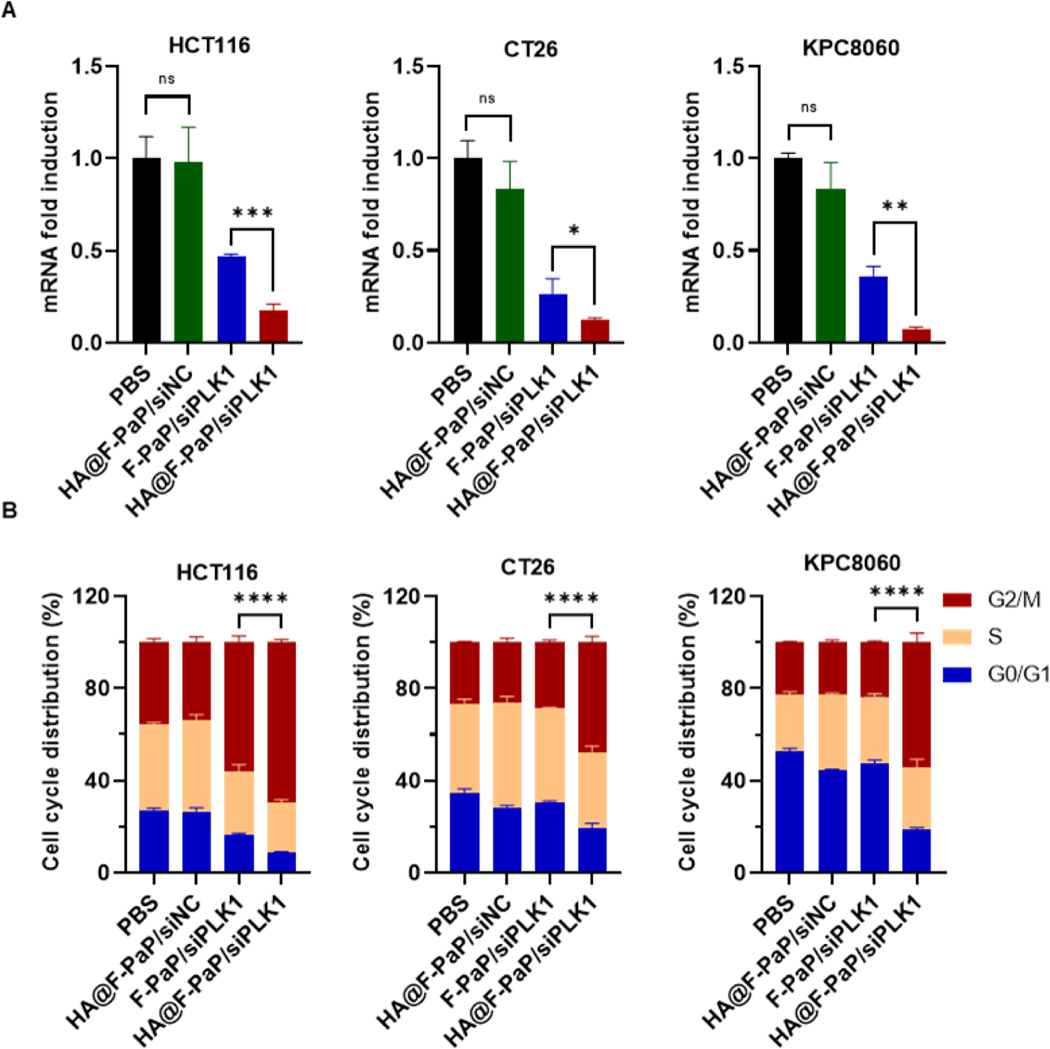

Having confirmed that HA@F-PaP/siRNA can effectively deliver siRNA into the cancer cells, we then used siPLK1 and negative control siNC to evaluate the target PLK1 gene silencing using qRT-PCR. The HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 silenced more than 80% of PLK1 expression in HCT116 and CT26, and more than 90% in KPC8060 cells. As expected, HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 can more effectively silence the PLK1 expression than F-PaP/siRNA, confirming the advantage of HA coating for siRNA delivery (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Transfection efficacy of nanoparticles. (A) PLK1 mRNA expression quantified by qRT-PCR after treatment with nanoparticles (100 nM siPLK1 or siNC) for 24 h. (B) Quantification of G0-G1, S, and G2/M populations after treatment with nanoparticles for 24 h. All data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.

Expression of PLK1 is crucial for inducing the G2/M transition in cell cycle and knockdown of PLK1 by siRNA leads to accumulation of cells in G2/M phase.62 The ability of the nanoparticles to induce cell cycle arrest was tested by flow cytometry. Compared with the other groups, HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 resulted in about 20–30% more cell population in G2/M phase compared with F-PaP/siPLK1 and decreased number of cells in G0/G1 and S phases in all three cell lines (Figure 4B and S10). Interestingly, F-PaP/siPLK1 could barely induce cell cycle arrest in CT26 and KPC8060 cells, despite strong PLK1 gene silencing effect (∼70%). This might be because 24 h was not long enough to observe the cell cycle arrest unless even stronger gene silencing effect was achieved like in the case of HA@F-PaP/siPLK1.

Regulation of polyamine metabolism and combination tumor inhibition

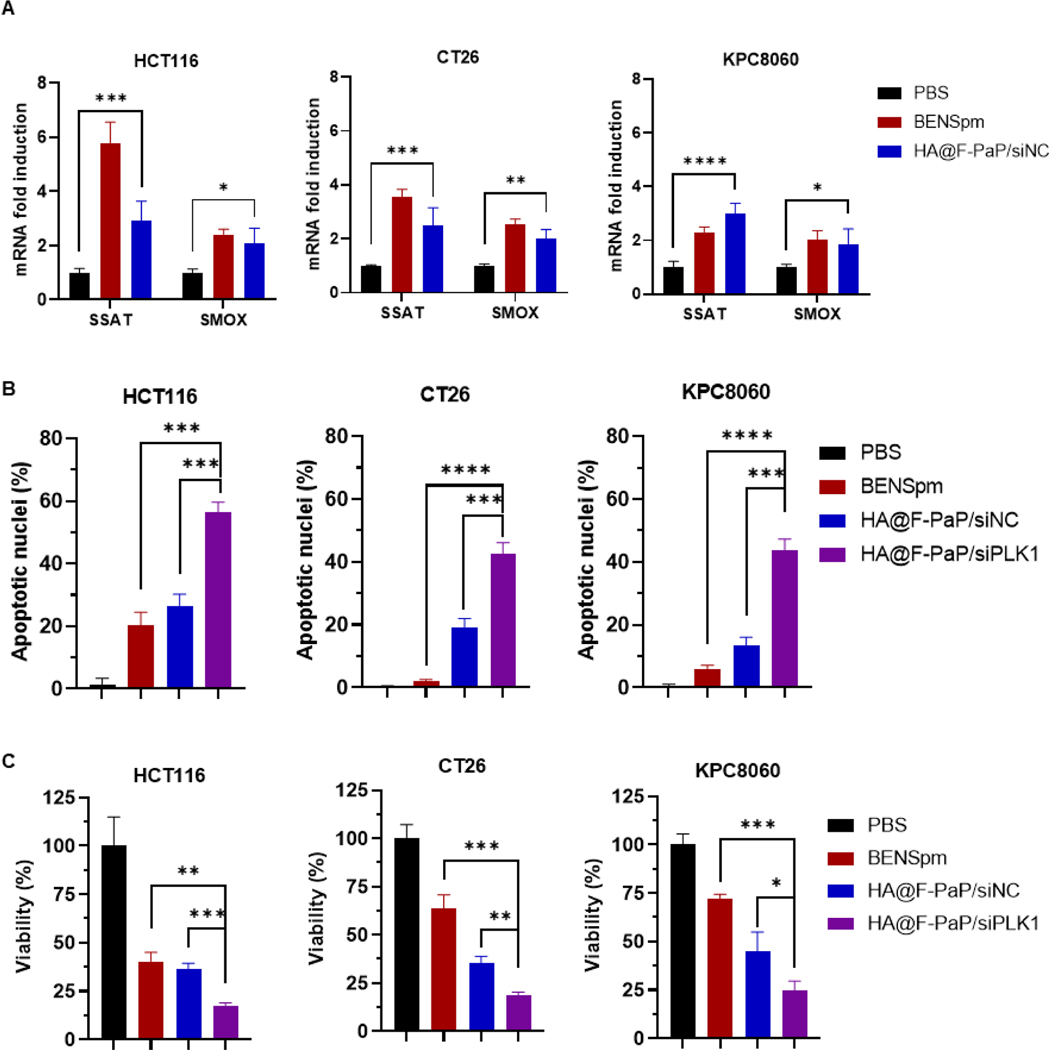

The above results showed that HA@F-PaP/siRNA was a suitable siRNA delivery system, which can significantly silence the target gene expression. We then evaluated the ability of HA@F-PaP/siRNA to induce catabolic enzymes SSAT and SMOX in the cancer cells. The treatment with HA@F-PaP/siRNA increased the mRNA expression of both SSAT and SMOX after 24 h incubation with HCT116 and CT26 (Figure 5A). In KPC8060 cells, only SMOX expression increased at 24 h, but both SSAT and SMOX were found elevated after 48 h (Figure 5A and S11).

Fig. 5.

Induction of polyamine catabolic enzymes and inhibition of cancer cell growth. (A) Relative changes in expression of SMOX and SSAT mRNA after treatment (4.8 µg/mL BENSpm or equivalent, 200 nM siRNA). (B) Cell apoptosis after treatment with BENSpm or nanoparticles (4.8 µg/mL BENSpm or equivalent and 200 nM siRNA) for 48 h. (C) Cell viability by CellTiter-Blue after treatment with BENSpm and nanoparticles for 48 h. All data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

Both BENSpm and siPLK1 can induce apoptosis in cancer cells and thus the ability of the nanoparticles to induce apoptosis was analyzed from nuclear morphology of cells stained with DAPI.63, 64 The treatment of HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 resulted in more than 40% apoptotic cells, which was significantly higher than in cells treated with BENSpm and HA@F-PaP/siNC (Figure 5B and S12). The pro-apoptotic effect of the nanoparticles was further confirmed by cell viability assay. HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 showed significantly higher cell killing with more than 80% in HCT116 and CT26 cells and more than 70% in KPC8060 cells when compared with HA@F-PaP/siNC and BENSpm (Figure 5C).

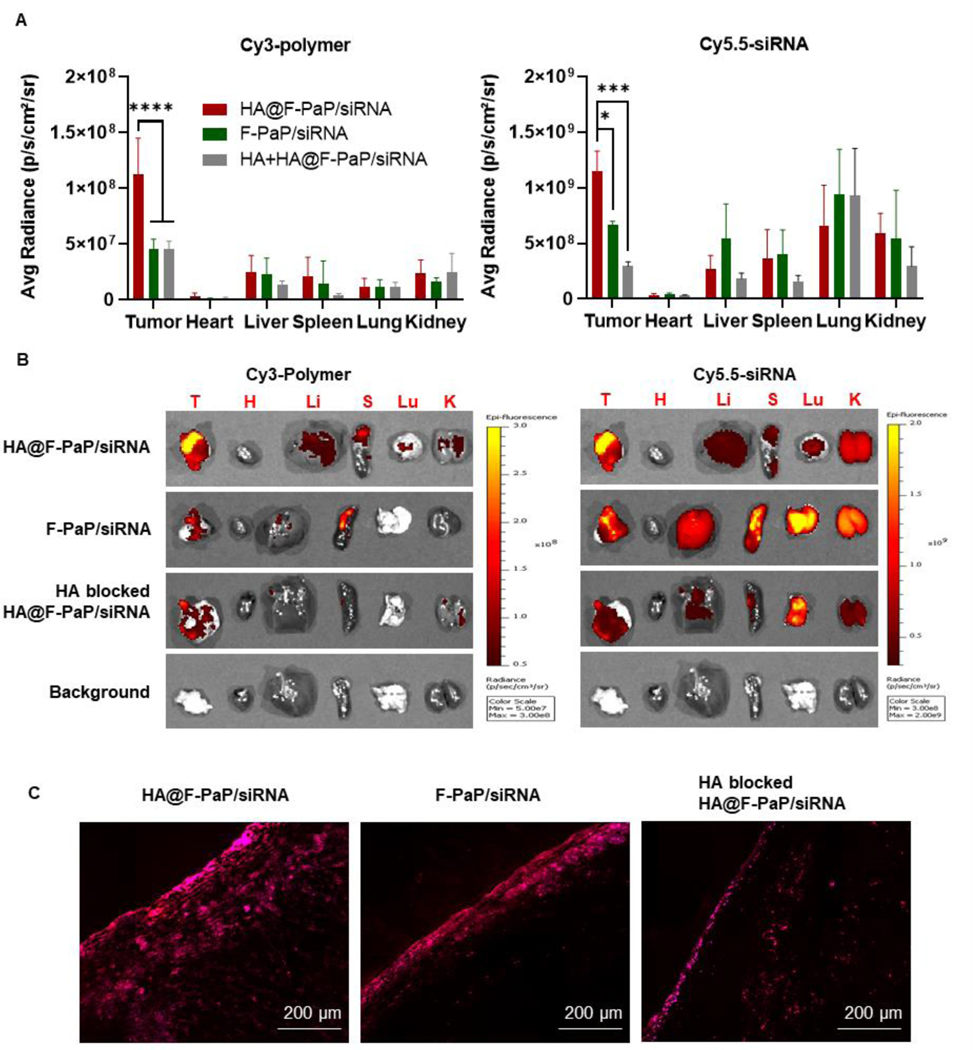

Biodistribution in orthotopic pancreatic cancer model

The strong anticancer effect in vitro provided impetus to advance the nanoparticles to in vivo studies. We first examined the biodistribution of the nanoparticles in orthotopically implanted syngeneic pancreatic tumors using mouse KPC8060 pancreatic cancer cells in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. Based on our previous studies, we have used intraperitoneal administration as an effective route for delivery to peritoneal tumors.65, 66 To understand how HA coating affects tumor accumulation, Cy3-labelled polymer and Cy5.5-labelled siRNA were used to prepare the nanoparticles and to quantify the tumor accumulation of both active components. The mice were sacrificed 24 h post-injection and fluorescence of different organs was measured by IVIS imaging system and semi-quantified using the provided software. HA@F-PaP/siRNA showed twice as much fluorescence in the tumor compared with F-PaP/siRNA as judged by both the polymer and siRNA content, indicating the advantages of the HA coating for tumor delivery (Figure 6A and 6B). To further investigate if the HA effect is related to its binding of CD44, high dose of free HA was injected 1 h prior to the injection of the nanoparticles. Tumor accumulation of the nanoparticles decreased about 50% for the polymer and 70% for the siRNA during this competitive binding experiment, validating CD44 involvement in the tumor accumulation. Consistent with the IVIS results, confocal microscopic analysis of the intratumor distribution showed that HA@F-PaP/siRNA had the highest uptake and deepest tumor penetration from the tumor surface when compared with the control groups, which was likely due to the higher doses of the targeted nanoparticles accumulating on the tumor surface (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Biodistribution of nanoparticles in PDAC model. (A) Mean fluorescent intensity of Cy3-labelled polymer (Ex = 535 nm, Em = 580 nm) and Cy5.5 labelled siRNA (Ex = 675 nm, 720 nm) 24 h post-injection. Data shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). * P<0.05, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. (B) Ex vivo fluorescent images of tumor and major organs by IVIS image system. (C) Confocal images of frozen tumor sections 24 h after IP injection of different formulations. Cy3-F-PaP (red), Cy5.5-siRNA (purple). Scale bar = 200 µm.

Therapeutic efficacy of HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 in orthotopic pancreatic cancer model

We hypothesized that HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 can achieve enhanced antitumor efficacy by cooperative effect of F-PaP and siPLK1. Hence, the orthotopic KPC8060 model was used to test the therapeutic effect of the nanoparticles. Mice were injected IP with different formulations every other day after day 21 for a total of 8 doses (Figure 7A). No overt toxicity was observed as indicated by stable body weight (Figure 7B). No tissue toxicity was observed by examination of H&E-stained slides of major organs compared with untreated group (Figure S13).

Figure 7.

Therapeutic evaluation of nanoparticles on PDAC. (A) Timeline of the treatment. Mice were treated every other day by IP injection (2.7 mg/kg BENSpm or equivalent polymer, 1.5 mg/kg siRNA). (B) Effect of treatment on animal body weight. (C) Tumor volume measurement by ultrasound and quantified by VevoLAB software. (D) Weight and images of the tumor at the end of the treatment. Data shown as mean ± SD (n = 5). (E) Ultrasound images of representative tumors in each treatment group on day 35. (F) RT-PCR analysis of PLK1 mRNA expression after the treatment. (n = 5) (G) Polyamine concentration in tumor at the end of the treatment. (n = 5) (H) Number of mice with metastasis in different organs (Kruskal-Wallis exact test, pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test and Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. (I) IHC staining of CD8+ cells in tumor. Scale bar = 100 µm. * P<0.05, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001

Tumor volume was measured at different time points non-invasively by ultrasound. On day 35, HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 group showed significantly smaller tumor volume compared with the other three treatment arms (Figure 7C and 7E). Mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected on day 37. Tumor weight was decreased by 65% with the treatment that combined the polyamine catabolism induction and PLK1 inhibition (Figure 7D). Notably, HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 showed a stronger tumor inhibition compared with free BENSpm, attesting to the advantage of the polymeric prodrug that can simultaneously deliver BENSpm and siPLK1. The PLK1 expression was significantly reduced (∼60% silencing) indicating successful delivery of siPLK1 (Figure 7F). Polyamine catabolism induction was demonstrated by decreased tumor polyamine concentrations (Figure 7G). Notably, the polyamine concentration in HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 group was reduced by ∼75% compared with the untreated group. As expected, PLK1 did not influence the tumor polyamine levels as shown by the similar polyamine concentrations found in the HA@F-PaP/siNC and HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 groups. The slightly enhanced polyamine depletion in the HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 compared with BENSpm alone was likely the result of the cell killing activity of PLK1 gene silencing and possibly also the consequence of improved tumor delivery of BENSpm by F-PaP. Analysis of the metastatic spread showed that the number of mice with distal metastatic lesions was greatly reduced (∼50%) in the HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 group compared with the other groups, indicating substantial antimetastatic effect of the PLK1 gene silencing. There was no observable antimetastatic effect associated with the treatment effect on the polyamine metabolism (Figure 7H). PLK1 promotes cancer invasiveness by triggering epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition reprogramming, which likely accounts for our findings of reduced metastasis.67, 68 Caspase 3 immunohistochemistry staining further validated cooperative proapoptotic activity of the HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 nanoparticles (Figure S14).

Although compounds targeting polyamine metabolism generally act as anti-proliferative agents, it was recently reported that polyamine blockade therapy was also highly dependent on the host immune system competence and depletion of polyamines can revert polyamine-mediated immunosuppression in tumors.24, 25, 69 Thus, we further investigated the effect of the treatments on the tumor immune microenvironment because of the markedly reduced concentration of polyamines in the treated animal tumors (Figure 7G). We found that all the treatments capable of targeting the polyamine metabolism increased the number of infiltrated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the tumors (Figure 7I). The HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 treatment with the strongest effect on polyamine depletion also showed the highest increase in the number of CD8+ cells. PLK1 gene silencing had no apparent effect on the tumor immune markers evaluated in this study evident in the non-significant difference in HA@F-PaP/siNC and HA@F-PaP/siPLK1. Due to the significant depletion of polyamines in the HA@F-PaP/siRNA group, significantly more CD8+ T cells in HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 was detected in tumor compared with BENSpm, which further attested to the advantage of nanoparticles for the delivery of BENSpm. Detailed investigation of the immunotherapeutic effects of our treatments will be reported in a future publication.

Conclusion

We developed HA-coated polyamine prodrug as an siRNA delivery system for efficient cancer treatment. Benefiting from the stabilizing effect of perfluoroalkyl moieties in the prodrug design and HA stabilization and targeting, the nanoparticles achieved reduced toxicity, improved gene silencing, and selective targeting to tumors. This combination delivery system showed superior apoptosis induction through combination of polyamine catabolism induction and cell cycle arrest in a panel of colorectal and pancreatic cancer cells. The orthotopic pancreatic cancer model was further used to evaluate the antitumor effect. The biodistribution study showed selective tumor accumulation through CD44 mediated process and, more importantly, HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 significantly inhibited the tumor growth compared with BENSpm monotherapy. We had also obtained evidence that depletion of polyamines by HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 may reverse the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. The therapeutic effect of nanoparticles on colorectal cancer will be examined in our follow-up studies. Overall, our results proved that disruption of polyamine metabolism combined with PLK1 gene silencing offers an effective combination treatment approach for cancer therapy. The innovative bioactive polymeric prodrug stabilized with fluoroalkyl moieties and HA is thus a promising candidate for therapeutic siRNA delivery to peritoneal tumors.

Materials and methods

Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)disulfide (BHED), 1,1’-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI), tris(2-aminoethyl) amine, heptafluorobutyric anhydride (HFBA), Amberlite IR120 Na+ form, and glutathione (GSH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dichloromethane (DCM), methanol, and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6), deuterium oxide, and chloroform-d were purchased from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). BENSpm was synthesized as previously described.70 McCoy’s 5A medium; RPMI1640 medium; DMEM high glucose medium, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin (Pen-Strep) and trypLE express reagent were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Polymer synthesis and characterization

First, BHED (1.6 g, 10.0 mmol) was activated through the addition of CDI (4.6 g, 30.0 mmol) followed by stirring for 1 h. Then the product disulfanediylbis(ethane-2,1-diyl) bis(1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate) (compound 2) was purified by water washing and extract with dichloromethane (DCM) to remove excessive CDI. The product in DCM layer was dried in sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure as white solid (theory as 3.1g, 91.1%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.21 (s, 2H), 7.46 (s, 2H), 7.12 (s, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 6Hz, 4H), 3.12 (t, J = 6Hz, 4H).

N-(2-(bis(2-aminoethyl)amino)ethyl)-2,2,3,3,4,4,4-heptafluorobutanamide (HFBTA) was synthesized by dropwise adding the heptafluorobutyric anhydride dropwise (562.0 mg, 1.37 mmol) to tris(2-aminoethyl) amine (TAEA) (2.0 g, 13.7 mmol) in acetonitrile and then stirred with Amberlite® IR120 Na+ form to remove hydrochloride. The product was extracted with DCM and dried with sodium sulfate before removal under reduced pressure to obtain the desired product as yellowish paste (287.0 mg, 61.0%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.45–3.38 (m, 2H), 2.85–2.75 (m, 4H), 2.73–2.66 (m, 2H), 2.61–2.51 (m, 4H).

Polyamine prodrug was synthesized through step polymerization under anhydrous conditions. BENspm (85.4 mg, 0.35 mmol) and compound 2 (239.4 mg, 0.70 mmol) was dissolved in DCM and stirred at 40 °C for 18h followed by the addition of HFBTA (60.0 mg, 0.18 mmol) and TAEA (17.0 mg, 0.12 mmol). The reaction was carried out at room temperature for overnight. Then ethanol was added, and DCM was under reduced pressure. The product was dialyzed (MWCO 1 kDa) against 0.1 mM HCl for one day and pure DI water for one day before lyophilization to obtain the product as a white solid (127.3 mg, 41.3%).

Preparation and characterization of nanoparticles

Polymer/siRNA nanoparticles were obtained by mixing equal volume of polymer and siRNA solutions in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH = 7.4), followed by the incubation at room temperature for 30 min. For HA coated nanoparticles, polymer/siRNA nanoparticles were mixed with equal volume of HA solution and incubated for 20 min. The hydrodynamic size and zeta-potential of the nanoparticles were measured by dynamic light scattering with NanoBrook Omni (Brookhaven instruments, NY). Morphological study of the nanoparticles was performed under transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Tecnal G2 Spirit, FEI company, USA) with NanoVAN® negative staining (Nanoprobes, USA). The stability of the nanoparticles in serum was assessed by measuring the size at different time points after the addition of FBS.

The ability of the polymers to condense the siRNA was evaluated in agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by SYBR safe. Different w/w ratios of polymer to siRNA ratio was prepared as mentioned above and loaded into 1.8% agarose gel containing 1X SYBR safe DNA gel staining (Invitrogen, CA) or put into 96 well plate with 1X SYBR safe gel staining. The gel was run in 0.5X Tris/Borate/EDTA buffer at 110 V for 15 min and visualized with E-gel imager (Life technology, CA) and free RNA was quantified by plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA) at λex/ λem = 500/555 nm. The degradability of the polymers was evaluated by incubating the polymers with or without 20 mM GSH at 37 °C for overnight. Then the ability of the polymers to condense was tested with the method mentioned above. The degradability of HA@F-PaP/siRNA was confirmed by incubation of the nanoparticles with or without 20 mM GSH for overnight. The light scattering intensity of the solutions was quantified by DLS and the morphology of the particles was studied by TEM as mentioned above.

Cell culture

The HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Michael Brattain (University of Nebraska Medical Center) and cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep (100 U/mL, 100 µg/mL). CT26 murine colorectal cancer cell line was purchased from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, VA) and was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep (100 U/mL, 100 µg/mL). KPC8060 cells derived from KPC PDAC mouse model (KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Pdx-1-Cre) were provided by Dr. Hollingsworth (University of Nebraska Medical Center) and cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep (100 U/mL, 100 µg/mL).

Polyamine analysis

Intracellular polyamine concentrations and BENSpm release from the prodrugs were determined by HPLC following acid extraction and dansylation of the supernatant, similar to that originally described by Kabra et al.57 Standards prepared for HPLC included diaminoheptane (internal standard), putrescine, spermidine, and spermine, all of which were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cytotoxicity and LDH release in vitro

Cytotoxicity of the polymers in three cell lines was evaluated by CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI). HCT116 and CT26 were plated five thousand cells per well and KPC8060 were plated as two thousand cells per well in the 96-well plates 24 h before treatments. Different concentrations of polymers were incubated with the cells in complete cell culture medium for 24 h. The medium was then removed, followed by the addition of the 100 µl full medium and 20 µl CellTiter-Blue reagent in each well. After incubation in 37 °C for 2 h, the fluorescent intensity [FI] was quantified at λex/ λem = 560/590 nm by plate reader. The cell viability (%) was calculated by ([FI]treated-[FI]blank)/ ([FI]untreated-[FI]blank) ×100. Polymer concentration that had a 50% viability was considered as IC50 which was calculated by GraphPad Prism with the dose-response analysis.

The LDH activity in medium was evaluated by LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Invitrogen, MA). Cells were plated the same concentration as mentioned above and were allowed 24 h to attach. Then different formulations at 4.8 µg/mL BENSpm equivalent concentration (w/w = 6 polymers 16 µg/mL) and 200 nM siNC RNA and 10X lysis buffer were incubated with cells in serum free medium for 1 h. 50 µL of culture supernatant from each well was collected and incubated with 50 µL reaction mixture for 30 min before addition of 50 µL stop solution. The absorbance [AB] was measured at 490 nm and absorbance at 680 nm was subtracted as background. LDH leakage% was calculated as ([AB]treated-[AB]spontaneous)/([AB]lysis-[AB]spontaneous) ×100.

Cell uptake of nanoparticles and CD44 expression in cells

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates 24 h before treatment. Nanoparticles prepared with 100 nM FITC labeled siRNA (FITC-siRNA) were incubated with the cells for 4 h in serum-free medium. Cells were washed with PBS and detached for analysis on flow cytometer LSRII (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA). Subcellular distribution of the nanoparticles was observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Cells were seeded in 8 well chamber (Catalog #: 155409, Fisher Scientific) for 48 h before treatment. Cells were then treated with Cy5.5-labeled siRNA (Cy5.5-siRNA) in serum free medium for 4 h followed by washing and staining with Hoechst 33342 for live-cell imaging in LSM800 laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cancer cell surface CD44 expression was measured using fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibody CD44-PE clone IM7 (eBioscience, CA) according to the manufacturer protocol and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

HCT116, CT26 and KPC8060 cells were seeded in 6-well plates using 2×105, 1×105 and 8×104 cells per well, respectively. Cells were treated with 100 nM siPLK1 or siNC in serum free medium for 4 h followed by the addition of FBS to make the full medium. After 24 h, total RNA was extracted by TRIzol® (Life technology, CA) according to the supplied protocol and converted into cDNA with high-capacity reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, CA). Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN) was used with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad laboratories, CA) and GAPDH and PLK1 primers. The relative mRNA of PLK1 level was expressed using comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method. Expression of polyamine catabolic enzymes SSAT and SMOX was also quantified by qRT-PCR through the same process. Cells were treated with 4.8 µg/mL BENSpm, HA@F-PaP/siNC (w/w = 6, 200 nM siRNA, F-PaP 16 µg/mL) for 24 h. Then the mRNA levels of SSAT and SMOX were measured as described above.

Cell cycle arrest assay

HCT116, CT26 and KPC8060 were seeded in 6-well plates using 2×105, 1×105 and 8×104 cells per well, respectively. After 24 h, cells were treated with different nanoparticles in serum free medium for 4 h, followed by the addition of FBS. The cells were incubated for 24 h and then fixed with 70% ethanol and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h before centrifuging and washing twice with PBS. FxCycle™ PI/RNase Staining Solution (Catalog # F10797, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to cells and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then cells were transferred for flow cytometry analysis.

Apoptosis assay by DAPI staining

Cells were treated with 4.8 µg/mL BENSpm, HA@F-PaP/siNC and HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 nanoparticles (16 µg/mL F-PaP equivalent to 4.8 µg/mL BENSpm, 200 nM siPLK1) for 48 h before staining with 2 µg/mL DAPI and observed with EVOS xl fluorescence microscope (Thermo, US). Condensed or fragmented nuclei were counted as apoptotic and the results were expressed as percentage of apoptotic nuclei in the field of view.

Cell killing assay

HCT116, CT26, and KPC8060 cells were seeded in 96-well plate at 5000 cells/well, 2000 cells/well and 1000 cells/well, respectively. Cells were allowed to attach overnight, before treatment for 48 h. The cell killing efficacy was quantified by CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability assay as described above.

Orthotopic pancreatic cancer model

Animal study protocols have been approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 mice (7 weeks old) from Charles River Laboratories were acclimated for a week before the establishment of the orthotopic pancreatic tumors according to the previous protocol.65, 66 Briefly, mice were first anesthetized by IP injection of ketamine/xylazine. 2.5 × 104 KPC8060 cells harvested from culture flask were resuspended in 40 µL of 1:1 mixture of PBS/Matrigel and injected into the tail of the pancreas after an incision (∼1 cm) was made in the peritoneum at the left side of abdomen. The abdomen was closed with 5–0 chromic catgut and soft staples. The staples were removed 12 days after the surgery.

Biodistribution in pancreatic cancer model

Orthotopic pancreatic tumor-bearing mice were injected IP with F-PaP/siRNA and HA@F-PaP/siRNA prepared using polymer labelled with Cy3 and siRNA labelled with Cy5.5. Each mouse was injected with the polymer containing 2.7 mg/kg BENSpm equivalent and 1.5 mg/kg siRNA. For HA competitive biodistribution, free HA (10 mg/mL, 200 µL) was injected IP 1 h prior to the HA@F-PaP/siRNA injection. Mice were sacrificed 24 h post-injection. Primary tumors and major organs were harvested for ex vivo imaging using Xenogen IVIS 200 (Ex = 535 nm, Em = 580 nm for Cy3 and Ex = 675 nm, Em = 720 nm for Cy5.5).

Therapeutic efficacy

Tumor bearing mice were randomly assigned to 4 groups (n = 5). Mice were either untreated or treated with BENSpm (2.7 mg/kg), HA@F-PaP/siNC (2.7 mg/kg BENSpm equivalent, 1.5 mg/kg siNC), or HA@F-PaP/siPLK1 (2.7 mg/kg BENSpm equivalent, 1.5 mg/kg siPLK1). The mice were weighed and injected IP every other day for a total of 8 doses. Tumor size was measured by ultrasound using Vevo 3100 MX550D transducer (40 MHz center frequency, 40 µM axial resolution) in B-mode on day 20, 26 and 35 as previously described.65 Briefly, mice were put on a heated and stationary platform and anesthetized by isoflurane. A motorized transducer adaptor was used to acquire 3D images. The volume of the tumor was quantified by Vevo lab software using reconstructed tumor shapes. On day 35, all mice were sacrificed. Primary tumor was harvested and weighed and metastasis of each organ in each mouse was recorded.

Histochemical analysis

Tumors and major organs were harvested and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin and stored in 75% ethanol. Major organs were embedded in paraffin and sectioned for staining with IHC and H&E.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t test and ANOVA were used to analyze difference between data groups. The significant difference was defined when P<0.05. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of metastases at each of the sites separately between the groups. Kruskal-Wallis exact test was used to compare the number of metastases per mouse between groups. Pairwise comparisons were tested with Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Bonferroni method adjusted for multiple comparisons. SAS software version 9.4 was used for analysis (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 CA235863. The animal imaging core receives support through the NIH Nebraska Center for Nanomedicine Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) P30 GM127200. The University of Nebraska Medical Center Advanced Microscopy Core Facility receives partial support from the National Institute for General Medical Science (NIGMS) INBRE - P20 GM103427 and COBRE - P30 GM106397 grants, as well as support from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) for The Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant- P30 CA036727, and the Nebraska Research Initiative. This publication’s contents and interpretations are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no known conflict of financial interest that could influence the results in the paper.

References

- 1.Landesman-Milo D; Goldsmith M; Leviatan Ben-Arye S; Witenberg B; Brown E; Leibovitch S; Azriel S; Tabak S; Morad V; Peer D, Hyaluronan grafted lipid-based nanoparticles as RNAi carriers for cancer cells. Cancer Letters 2013, 334 (2), 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conde J; Artzi N, Are RNAi and miRNA therapeutics truly dead? Trends in Biotechnology 2015, 33 (3), 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballarín-González B; Ebbesen MF; Howard KA, Polycation-based nanoparticles for RNAi-mediated cancer treatment. Cancer Letters 2014, 352 (1), 66–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu SY; Lopez-Berestein G; Calin GA; Sood AK, RNAi Therapies: Drugging the Undruggable. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6 (240), 240ps7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M; Thanou M, Targeting nanoparticles to cancer. Pharmacological Research 2010, 62 (2), 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis ME; Zuckerman JE; Choi CHJ; Seligson D; Tolcher A; Alabi CA; Yen Y; Heidel JD; Ribas A, Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature 2010, 464 (7291), 1067–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li SD; Huang L, Gene therapy progress and prospects: non-viral gene therapy by systemic delivery. Gene Therapy 2006, 13 (18), 1313–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson CE; Kintzing JR; Hanna A; Shannon JM; Gupta MK; Duvall CL, Balancing Cationic and Hydrophobic Content of PEGylated siRNA Polyplexes Enhances Endosome Escape, Stability, Blood Circulation Time, and Bioactivity in Vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (10), 8870–8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malcolm DW; Freeberg MAT; Wang Y; Sims KR; Awad HA; Benoit DSW, Diblock Copolymer Hydrophobicity Facilitates Efficient Gene Silencing and Cytocompatible Nanoparticle-Mediated siRNA Delivery to Musculoskeletal Cell Types. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18 (11), 3753–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neamnark A; Suwantong O; K. C RB; Hsu CYM; Supaphol P; Uludağ H, Aliphatic Lipid Substitution on 2 kDa Polyethylenimine Improves Plasmid Delivery and Transgene Expression. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2009, 6 (6), 1798–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y; Li J; Chen Y; Oupicky D, Balancing polymer hydrophobicity for ligand presentation and siRNA delivery in dual function CXCR4 inhibiting polyplexes. Biomater Sci 2015, 3 (7), 1114–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z; Zhang Z; Zhou C; Jiao Y, Hydrophobic modifications of cationic polymers for gene delivery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35 (9), 1144–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M; Liu H; Li L; Cheng Y, A fluorinated dendrimer achieves excellent gene transfection efficacy at extremely low nitrogen to phosphorus ratios. Nature Communications 2014, 5 (1), 3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasuya MCZ; Nakano S; Katayama R; Hatanaka K, Evaluation of the hydrophobicity of perfluoroalkyl chains in amphiphilic compounds that are incorporated into cell membrane. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry 2011, 132 (3), 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G; Wang Y; Ullah A; Huai Y; Xu Y, The effects of fluoroalkyl chain length and density on siRNA delivery of bioreducible poly(amido amine)s. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 152, 105433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge C; Yang J; Duan S; Liu Y; Meng F; Yin L, Fluorinated α-Helical Polypeptides Synchronize Mucus Permeation and Cell Penetration toward Highly Efficient Pulmonary siRNA Delivery against Acute Lung Injury. Nano Letters 2020, 20 (3), 1738–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue L; Yan Y; Kos P; Chen X; Siegwart DJ, PEI fluorination reduces toxicity and promotes liver-targeted siRNA delivery. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2021, 11 (1), 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai X; Zhu H; Zhang Y; Gu Z, Highly Efficient and Safe Delivery of VEGF siRNA by Bioreducible Fluorinated Peptide Dendrimers for Cancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9 (11), 9402–9415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng Q; Li X; Zhu L; He H; Chen D; Chen Y; Yin L, Serum-resistant, reactive oxygen species (ROS)-potentiated gene delivery in cancer cells mediated by fluorinated, diselenide-crosslinked polyplexes. Biomaterials Science 2017, 5 (6), 1174–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He B; Wang Y; Shao N; Chang H; Cheng Y, Polymers modified with double-tailed fluorous compounds for efficient DNA and siRNA delivery. Acta Biomaterialia 2015, 22, 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burrell RA; McGranahan N; Bartek J; Swanton C, The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature 2013, 501 (7467), 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer AC; Sorger PK, Combination Cancer Therapy Can Confer Benefit via Patient-to-Patient Variability without Drug Additivity or Synergy. Cell 2017, 171 (7), 1678–1691.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhaveri A; Deshpande P; Torchilin V, Stimuli-sensitive nanopreparations for combination cancer therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2014, 190, 352–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes CS; Shicora AC; Keough MP; Snook AE; Burns MR; Gilmour SK, Polyamine-blocking therapy reverses immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Res 2014, 2 (3), 274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander ET; Minton A; Peters MC; Phanstiel O.t. ; Gilmour, S. K., A novel polyamine blockade therapy activates an anti-tumor immune response. Oncotarget 2017, 8 (48), 84140–84152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travers M; Brown SM; Dunworth M; Holbert CE; Wiehagen KR; Bachman KE; Foley JR; Stone ML; Baylin SB; Casero RA Jr.; Zahnow CA, DFMO and 5-Azacytidine Increase M1 Macrophages in the Tumor Microenvironment of Murine Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res 2019, 79 (13), 3445–3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexiou GA; Vartholomatos E; K IT; Peponi E; Markopoulos G; V AP; Tasiou I; Ragos V; Tsekeris P; Kyritsis AP; Galani V, Combination treatment for glioblastoma with temozolomide, DFMO and radiation. J buon 2019, 24 (1), 397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray Stewart T; Von Hoff D; Fitzgerald M; Marton LJ; Becerra CHR; Boyd TE; Conkling PR; Garbo LE; Jotte RM; Richards DA; Smith DA; Stephenson JJ Jr.; Vogelzang NJ; Wu HH; Casero RA Jr., A Phase Ib multicenter, dose-escalation study of the polyamine analogue PG-11047 in combination with gemcitabine, docetaxel, bevacizumab, erlotinib, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, or sunitinib in patients with advanced solid tumors or lymphoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2021, 87 (1), 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hahm HA; Dunn VR; Butash KA; Deveraux WL; Woster PM; Casero RA Jr.; Davidson NE, Combination of standard cytotoxic agents with polyamine analogues in the treatment of breast cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res 2001, 7 (2), 391–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pledgie-Tracy A; Billam M; Hacker A; Sobolewski MD; Woster PM; Zhang Z; Casero RA; Davidson NE, The role of the polyamine catabolic enzymes SSAT and SMO in the synergistic effects of standard chemotherapeutic agents with a polyamine analogue in human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010, 65 (6), 1067–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hector S; Tummala R; Kisiel ND; Diegelman P; Vujcic S; Clark K; Fakih M; Kramer DL; Porter CW; Pendyala L, Polyamine catabolism in colorectal cancer cells following treatment with oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and N1, N11 diethylnorspermine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008, 62 (3), 517–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tummala R; Diegelman P; Hector S; Kramer DL; Clark K; Zagst P; Fetterly G; Porter CW; Pendyala L, Combination effects of platinum drugs and N1, N11 diethylnorspermine on spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase, polyamines and growth inhibition in A2780 human ovarian carcinoma cells and their oxaliplatin and cisplatin-resistant variants. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011, 67 (2), 401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handa AK; Fatima T; Mattoo AK, Polyamines: Bio-Molecules with Diverse Functions in Plant and Human Health and Disease. Frontiers in Chemistry 2018, 6 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerner EW; Meyskens FL, Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nature Reviews Cancer 2004, 4 (10), 781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pegg AE, Functions of Polyamines in Mammals *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291 (29), 14904–14912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casero RA; Murray Stewart T; Pegg AE, Polyamine metabolism and cancer: treatments, challenges and opportunities. Nature Reviews Cancer 2018, 18 (11), 681–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novita Sari I; Setiawan T; Seock Kim K; Toni Wijaya Y; Won Cho K; Young Kwon H, Metabolism and function of polyamines in cancer progression. Cancer Letters 2021, 519, 91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seiler N, Thirty Years of Polyamine-Related Approaches to Cancer Therapy. Retrospect and Prospect. Part 1. Selective Enzyme Inhibitors. Current Drug Targets 2003, 4 (7), 537–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seiler N, Thirty Years of Polyamine-Related Approaches to Cancer Therapy. Retrospect and Prospect. Part 2. Structural Analogues and Derivatives. Current Drug Targets 2003, 4 (7), 565–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen WL; McLean EG; Boyer J; McCulla A; Wilson PM; Coyle V; Longley DB; Casero RA; Johnston PG, The role of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in determining response to chemotherapeutic agents in colorectal cancer cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2007, 6 (1), 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang BK; Bergeron RJ; Porter CW; Liang Y, Antitumor effects ofN-alkylated polyamine analogues in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma models. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 1992, 30 (3), 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian Y; Wang S; Wang B; Zhang J; Jiang R; Zhang W, Overexpression of SSAT by DENSPM treatment induces cell detachment and apoptosis in glioblastoma. Oncol Rep 2012, 27 (4), 1227–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y; Kramer DL; Li F; Porter CW, Loss of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins as a determinant of polyamine analog-induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Oncogene 2003, 22 (32), 4964–4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pledgie-Tracy A; Billam M; Hacker A; Sobolewski MD; Woster PM; Zhang Z; Casero RA; Davidson NE, The role of the polyamine catabolic enzymes SSAT and SMO in the synergistic effects of standard chemotherapeutic agents with a polyamine analogue in human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2010, 65 (6), 1067–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolff AC; Armstrong DK; Fetting JH; Carducci MK; Riley CD; Bender JF; Casero RA Jr.; Davidson NE, A Phase II study of the polyamine analog N1,N11-diethylnorspermine (DENSpm) daily for five days every 21 days in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2003, 9 (16 Pt 1), 5922–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi T; Sano B; Nagata T; Kato H; Sugiyama Y; Kunieda K; Kimura M; Okano Y; Saji S, Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is overexpressed in primary colorectal cancers. Cancer Science 2003, 94 (2), 148–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strebhardt K; Ullrich A, Targeting polo-like kinase 1 for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2006, 6 (4), 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weichert W; Schmidt M; Jacob J; Gekeler V; Langrehr J; Neuhaus P; Bahra M; Denkert C; Dietel M; Kristiansen G, Overexpression of Polo-Like Kinase 1 Is a Common and Early Event in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreatology 2005, 5 (2–3), 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C; Sun X; Ren Y; Lou Y; Zhou J; Liu M; Li D, Validation of Polo-like kinase 1 as a therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biology & Therapy 2012, 13 (12), 1214–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganesh S; Iyer AK; Morrissey DV; Amiji MM, Hyaluronic acid based self-assembling nanosystems for CD44 target mediated siRNA delivery to solid tumors. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (13), 3489–3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mero A; Campisi M, Hyaluronic Acid Bioconjugates for the Delivery of Bioactive Molecules. Polymers 2014, 6 (2), 346–369. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie Y; Murray-Stewart T; Wang Y; Yu F; Li J; Marton LJ; Casero RA; Oupický D, Self-immolative nanoparticles for simultaneous delivery of microRNA and targeting of polyamine metabolism in combination cancer therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2017, 246, 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Y; Li J; Kanvinde S; Lin Z; Hazeldine S; Singh RK; Oupický D, Self-Immolative Polycations as Gene Delivery Vectors and Prodrugs Targeting Polyamine Metabolism in Cancer. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2015, 12 (2), 332–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong Y; Zhu Y; Li J; Zhou Q-H; Wu C; Oupický D, Synthesis of Bisethylnorspermine Lipid Prodrug as Gene Delivery Vector Targeting Polyamine Metabolism in Breast Cancer. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2012, 9 (6), 1654–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang M; Cheng Y, Structure-activity relationships of fluorinated dendrimers in DNA and siRNA delivery. Acta Biomaterialia 2016, 46, 204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen G; Wang K; Hu Q; Ding L; Yu F; Zhou Z; Zhou Y; Li J; Sun M; Oupický D, Combining Fluorination and Bioreducibility for Improved siRNA Polyplex Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9 (5), 4457–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kabra PM; Lee HK; Lubich WP; Marton LJ, Solid-phase extraction and determination of dansyl derivatives of unconjugated and acetylated polyamines by reversed-phase liquid chromatography: Improved separation systems for polyamines in cerebrospinal fluid, urine and tissue. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications 1986, 380, 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ran R; Liu Y; Gao H; Kuang Q; Zhang Q; Tang J; Huang K; Chen X; Zhang Z; He Q, Enhanced gene delivery efficiency of cationic liposomes coated with PEGylated hyaluronic acid for anti P-glycoprotein siRNA: A potential candidate for overcoming multi-drug resistance. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2014, 477 (1), 590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fischer D; Li Y; Ahlemeyer B; Krieglstein J; Kissel T, In vitro cytotoxicity testing of polycations: influence of polymer structure on cell viability and hemolysis. Biomaterials 2003, 24 (7), 1121–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen G; Wang K; Hu Q; Ding L; Yu F; Zhou Z; Zhou Y; Li J; Sun M; Oupický D, Combining Fluorination and Bioreducibility for Improved siRNA Polyplex Delivery. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9 (5), 4457–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seok HY; Sanoj Rejinold N; Lekshmi KM; Cherukula K; Park IK; Kim YC, CD44 targeting biocompatible and biodegradable hyaluronic acid cross-linked zein nanogels for curcumin delivery to cancer cells: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Control Release 2018, 280, 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu X; Erikson RL, Polo-like kinase (Plk)1 depletion induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100 (10), 5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spänkuch B; Kurunci-Csacsko E; Kaufmann M; Strebhardt K, Rational combinations of siRNAs targeting Plk1 with breast cancer drugs. Oncogene 2007, 26 (39), 5793–5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ha HC; Woster PM; Yager JD; Casero RA, The role of polyamine catabolism in polyamine analogue-induced programmed cell death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997, 94 (21), 11557–11562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie Y; Hang Y; Wang Y; Sleightholm R; Prajapati DR; Bader J; Yu A; Tang W; Jaramillo L; Li J; Singh RK; Oupický D, Stromal Modulation and Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer with Local Intraperitoneal Triple miRNA/siRNA Nanotherapy. ACS Nano 2020, 14 (1), 255–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hang Y; Tang S; Tang W; Větvička D; Zhang C; Xie Y; Yu F; Yu A; Sil D; Li J; Singh RK; Oupický D, Polycation fluorination improves intraperitoneal siRNA delivery in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 333, 139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin S-B; Jang H-R; Xu R; Won J-Y; Yim H, Active PLK1-driven metastasis is amplified by TGF-β signaling that forms a positive feedback loop in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39 (4), 767–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cai XP; Chen LD; Song HB; Zhang CX; Yuan ZW; Xiang ZX, PLK1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric carcinoma cells. Am J Transl Res 2016, 8 (10), 4172–4183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alexander ET; Mariner K; Donnelly J; Phanstiel O; Gilmour SK, Polyamine Blocking Therapy Decreases Survival of Tumor-Infiltrating Immunosuppressive Myeloid Cells and Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of PD-1 Blockade. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2020, 19 (10), 2012–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bergeron RJ; Neims AH; McManis JS; Hawthorne TR; Vinson JR; Bortell R; Ingeno MJ, Synthetic polyamine analogues as antineoplastics. J Med Chem 1988, 31 (6), 1183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.