Abstract

Objective

To establish the prevalence of long-term and serious harms of medical cannabis for chronic pain.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CENTRAL from inception to 1 April 2020.

Study selection

Non-randomised studies reporting on harms of medical cannabis or cannabinoids in adults or children living with chronic pain with ≥4 weeks of follow-up.

Data extraction and synthesis

A parallel guideline panel provided input on the design and interpretation of the systematic review, including selection of adverse events for consideration. Two reviewers, working independently and in duplicate, screened the search results, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We used random-effects models for all meta-analyses and the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to evaluate the certainty of evidence.

Results

We identified 39 eligible studies that enrolled 12 143 adult patients with chronic pain. Very low certainty evidence suggests that adverse events are common (prevalence: 26.0%; 95% CI 13.2% to 41.2%) among users of medical cannabis for chronic pain, particularly any psychiatric adverse events (prevalence: 13.5%; 95% CI 2.6% to 30.6%). Very low certainty evidence, however, indicates serious adverse events, adverse events leading to discontinuation, cognitive adverse events, accidents and injuries, and dependence and withdrawal syndrome are less common and each typically occur in fewer than 1 in 20 patients. We compared studies with <24 weeks and ≥24 weeks of cannabis use and found more adverse events reported among studies with longer follow-up (test for interaction p<0.01). Palmitoylethanolamide was usually associated with few to no adverse events. We found insufficient evidence addressing the harms of medical cannabis compared with other pain management options, such as opioids.

Conclusions

There is very low certainty evidence that adverse events are common among people living with chronic pain who use medical cannabis or cannabinoids, but that few patients experience serious adverse events.

Keywords: Pain management, PAIN MANAGEMENT, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strengths of this systematic review include a comprehensive search for non-randomised studies, explicit eligibility criteria, screening of studies and collection of data in duplicate to increase reliability, and use of the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to evaluate the certainty of evidence.

Our review is limited by the non-comparative design of most studies, which precludes confident inferences regarding the proportion of adverse events that can be attributed to medical cannabis or cannabinoids.

One-third of studies were at high risk of selection bias, primarily because they included prevalent cannabis users. In such studies, the prevalence of adverse events may be underestimated.

Our review provides limited evidence on the harms of prolonged medical cannabis use since most studies reported adverse events for less than 1 year of follow-up.

Some studies reported on smoked or vaporised medical cannabis, which may be associated with different adverse events (eg, respiratory) than oral or topical formulations. We performed subgroup analyses based on the type of medical cannabis, but our findings were of low credibility due to inconsistency and/or imprecision.

Background

Chronic pain is the primary cause of healthcare resource use and disability among working adults in North America and Western Europe.1 2 The use of cannabis for the management of chronic pain is becoming increasingly common due to pressure to reduce opioid use, increased availability and changing legislation, shift in public attitudes and decreased stigma, and aggressive marketing.3 4 The two most-studied cannabinoids in medical cannabis are delta‐9‐tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).5 THC binds to cannabinoid receptors types 1 and 2, is an analogue to the endogenous cannabinoid, anandamide and has shown psychoactive, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antipruritic, antispasmodic and muscle-relaxant activities. CBD directly interacts with various ion channels to produce analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant and anxiolytic activities, without the psychoactive effects of THC.5 Use of cannabis for therapeutic purposes, however, remains contentious due to the social and legal context and its known and suspected harms.6–9

Though common adverse events caused by medical cannabis, including nausea, vomiting, headache, drowsiness and dizziness, have been well documented in randomised controlled trials and reviews of randomised controlled trials,10 11 less is known about potentially uncommon but serious adverse events, particularly events that may occur with longer durations of medical cannabis use, such as dependence, withdrawal symptoms and psychosis.4 12–17 Such adverse events are usually observed in large non-randomised studies that recruit larger numbers of patients and typically follow them for longer durations of time. Further, evidence from non-randomised studies may be more generalisable, since randomised controlled trials often use strict eligibility criteria.

The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to summarise the evidence on the risks and, when evidence on risk is not available, the prevalence of adverse events related to medical cannabis and cannabinoids from non-randomised studies for a BMJ Rapid Recommendation addressing medical cannabis for chronic pain.18 This evidence synthesis is part of the BMJ Rapid Recommendations project, a collaborative effort from the MAGIC Evidence Ecosystem Foundation (www.magicevidence.org) and the BMJ.19 A guideline panel helped define the study question and selected adverse events for review. The adverse events of interest include psychiatric and cognitive adverse events, injuries and accidents, and dependence and withdrawal. It is one of four systematic reviews that together informed a parallel guideline.11 18 20 21 A parallel systematic review addressed evidence from randomised trials.11

Methods

We report our systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Harms Checklist.22

Guideline panel involvement

A guideline panel helped define the study question and selected the adverse events for review. The panel included nine content experts (two general internists, two family physicians, a paediatrician, a physiatrist, a paediatric anaesthesiologist, a clinical pharmacologist and a rheumatologist), nine methodologists (five of whom are also front-line clinicians) and three people living with chronic pain (one of whom used cannabinoids for medical purposes).

Patient and public involvement

Three patient partners (two women and one man) were included as part of the guideline panel and contributed to the selection and prioritisation of outcomes, protocol, and interpretation of review findings, and provided insight on values and preferences. Each of our patient partners was living with chronic pain and were selected to represent a range of experiences regarding medical cannabis. One had tried and discontinued medical cannabis due to lack of efficacy. One had found success with use of medical cannabis (primarily oral CBD). The third had no personal experience with medical cannabis.

Search

A medical librarian searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from inception to 1 April 2020, with no restrictions on language, for non-randomised studies reporting on harms or adverse events of medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain (online supplemental appendix 1). We scanned reference lists of relevant reviews to identify any eligible studies not retrieved by our electronic search and solicited content experts from our panel for unpublished studies. Search records, and later full-texts of studies, not reported in English were translated by a native speaker of the language.

bmjopen-2021-054282supp001.pdf (5.3MB, pdf)

Study selection

Reviewers (DZ, MAC, AA, RWMV, GL, KL, JED, MMA, BYH, CH and PH), working independently and in duplicate, reviewed titles and abstracts of search records and subsequently full texts of records found potentially eligible at the title and abstract screening stage. Reviewers resolved disagreements by discussion or by adjudication by a third reviewer (DZ).

We included all non-randomised studies that reported on any patient-important harm or adverse event associated with the use of any formulation of medical cannabis or cannabinoids in adults or children, living with chronic pain (pain lasting for ≥3 months) or a medical condition associated with chronic pain (ie, fibromyalgia, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, neuropathy, inflammatory bowel disease, stroke or advanced cancer) or that compared adverse events associated with medical cannabis or cannabinoids with another pharmacological or non-pharmacological intervention. We considered herbal cannabis consumed for medical reasons as medical cannabis. Based on input from the guideline panel, we excluded studies in which patients used cannabis for less than 4 weeks because we anticipated that 4 weeks would be the minimum amount of time after which we would reasonably expect to observe potential serious or long-term harms associated with medical cannabis.23 We looked for explicit statements or evidence that patients were experiencing chronic pain. We excluded studies in which: (1) fewer than 25 patients used medical cannabis or cannabinoids (to exclude studies that would not appreciably contribute to pooled estimates and studies that may be too small to reliably estimate the prevalence of adverse events), (2) patients did not suffer from chronic pain or a condition commonly associated with chronic pain or more than 20% of patients reported using medical cannabis or cannabinoids for a condition other than chronic pain (to exclude studies in which patients did not predominantly suffer from chronic pain), (3) patients were using cannabis for recreational reasons, (4) only surrogate measures of patient-important harms and adverse effects (eg, performance on cognitive tests, lab values) were reported and (5) systematic reviews and other types of studies that did not provide primary data.

Data extraction and risk of bias

Reviewers (DZ, MAC, AA, RWMV, GL, KL, JED, MMA, BYH, CH and PH), working independently and in duplicate and using a standardised and pilot-tested data collection form, extracted the following information from each eligible study: (1) study design, (2) patient characteristics (age, sex, condition/diagnosis), (3) characteristics of medical cannabis or cannabinoids (name of product, dose and duration) and (4) number of patients that experienced adverse events, including all adverse events, serious adverse events and withdrawal due to adverse events. Reviewers resolved disagreements by discussion or by adjudication with a third party (DZ). We classified adverse events as serious based on the classification used in primary studies. For comparative studies, we collected results from models adjusted for confounders, when reported and unadjusted models when results for adjusted models were not reported.

When studies reported the number of events rather than the number of patients experiencing adverse events, we only extracted the number of events if they were infrequent (the number of events accounted for less than 10% of the total number of study participants). For studies that reported on adverse events at multiple time points, we extracted data for the longest point of follow-up that included, at minimum, 80% of the patients recruited into the study. Reviewers resolved disagreements by discussion or by adjudication with a third reviewer (DZ).tim

Reviewers (DZ, MAC, AA, RWMV, GL, KL, JED, MMA, BYH, CH and PH), working independently and in duplicate, used the Cochrane-endorsed ROBINS-I tool to rate the risk of bias of studies as low, moderate, serious or critical across seven domains: (1) bias due to confounding, (2) selection of patients into the study, (3) classification of the intervention, (4) bias due to deviations from the intended intervention, (5) missing data, (6) measurement of outcomes and (7) selection of reported results.24 Reviewers resolved discrepancies by discussion or by adjudication by a third party (DZ). Online supplemental appendix 2 presents additional details on the assessment of risk of bias. Studies were considered to adequately adjust for confounders if they adjusted, at minimum, for pain intensity, concomitant pain medication, disability status, alcohol use and past cannabis use. Studies were rated at low risk of bias overall when all domains were at low risk of bias; moderate risk of bias if all domains were rated at low or moderate risk of bias; at serious risk of bias when all domains were rated either at low, moderate or serious risk of bias; and at critical risk of bias when one or more domains were rated as critical.

Data synthesis

In this review, we synthesised data on serious adverse events and adverse events that may emerge with longer duration of medical cannabis use. Identified by a parallel BMJ Rapid Recommendations guideline panel as important, these patient-important outcomes included psychiatric and cognitive adverse events, injuries and accidents, and dependence and withdrawal. Data on all other adverse events reported in primary studies are available in an open-access database (https://osf.io/ut36z/).25 We classified adverse events as serious based on the classification used in primary studies.

Adverse events are reported as binary outcomes. For comparative studies, when possible, we present risk differences and associated 95% CIs. Since there were only two eligible comparative studies, each with different comparators, we did not perform meta-analysis. For single-arm studies, we pooled the proportion of patients experiencing adverse events of interest by first applying a Freeman-Tukey type arcsine square root transformation to stabilise the variance. Without this transformation, very high or very low prevalence estimates can produce confidence intervals that contain values lower than 0% or higher than 100%. All meta-analyses used DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models, which are conservative as they consider both within-study and between-study variability.26–28 We also pooled all effect estimates using fixed-effects models as a sensitivity analysis. We evaluated heterogeneity for all pooled estimates through visual inspection of forest plots and calculation of tau-squared (τ2, because some statistical tests of heterogeneity (I2 and Cochrane’s Q) can be misleading when sample sizes are large and CIs are therefore narrow.29 Higher values of τ2, I2 and Cochrane’s Q indicate higher statistical heterogeneity. For studies that reported estimates for all-cause adverse events and those deemed to be potentially related to cannabis use, we preferentially synthesised results for all adverse events.

For analyses for which we observed high clinical heterogeneity (ie, substantial differences in the estimates of individual studies and minimal overlap in the CIs), we presented results narratively.

In consultation with the parallel BMJ Rapid Recommendations guideline panel, we also prespecified six subgroup hypotheses to explain heterogeneity between studies: (1) study design (longitudinal vs cross-sectional), (2) type of medical cannabis, (3) cancer versus non-cancer pain, (4) children versus adults, (5) duration of medical cannabis use (shorter or longer than the median duration of follow-up across studies) and (6) risk of bias (low/moderate vs serious/critical). We also performed two post hoc subgroup analyses: (1) duration of follow-up (shorter or longer than the median duration of follow-up across studies) and (2) selection bias (studies at moderate, serious or critical risk of selection bias vs studies at low risk of selection bias). We anticipated that studies reporting on shorter use of medical cannabis, as well as cross-sectional studies, studies on patients with cancer, studies including adults, studies with active comparators, studies at high risk of bias would report fewer adverse events. We anticipated that studies at moderate, serious or critical risk of selection bias that included prevalent cannabis users (ie, people who were using medical cannabis before the inception of the study) or were preceded by a run-in period or clinical trial during which patients that experienced adverse events or found medical cannabis intolerable could discontinue would report fewer adverse events because prevalent of medical cannabis are likely to represent populations that have self-selected for tolerance to cannabis. We performed tests for interaction to establish whether subgroups differed significantly from one another. We assessed the credibility of significant subgroup effects (test for interaction p<0.05) using published criteria.30 31

We performed all analyses using the ‘meta’ package in R (V.3.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing).32

Certainty of evidence

We used the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to rate the certainty of evidence.33 34 Based on GRADE guidance for using the ROBINS-I tool, evidence starts at high certainty and is downgraded by one level when the majority of the evidence comes from studies at moderate risk of bias, two levels when the majority of the evidence comes from studies at high risk of bias, and three levels when the majority of the evidence comes from studies rated at critical risk of bias.33 We additionally considered potential limitations due to indirectness if the population, intervention, or adverse events assessed in studies did not reflect the populations, interventions or adverse events of interest, inconsistency if there was important unexplained differences in the results of studies, and imprecision if the upper and lower bounds of CIs indicated appreciably different rates of adverse events. For assessing inconsistency and imprecision for the outcome all adverse events, based on feedback from the guideline panel, we deemed a 20% difference in the prevalence of all adverse evidence to be patient-important; a 10% difference for adverse events leading to discontinuation, serious adverse events and psychiatric, cognitive, withdrawal and dependence, injuries; and a 3% difference for potentially fatal adverse events, such as suicides and motor vehicle accidents. We followed GRADE guidance for communicating our findings.35 Guideline panel members interpreted the magnitude of adverse events and decided whether the observed prevalence of adverse events was sufficient to affect patients’ decisions to use medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain.

Results

Study selection

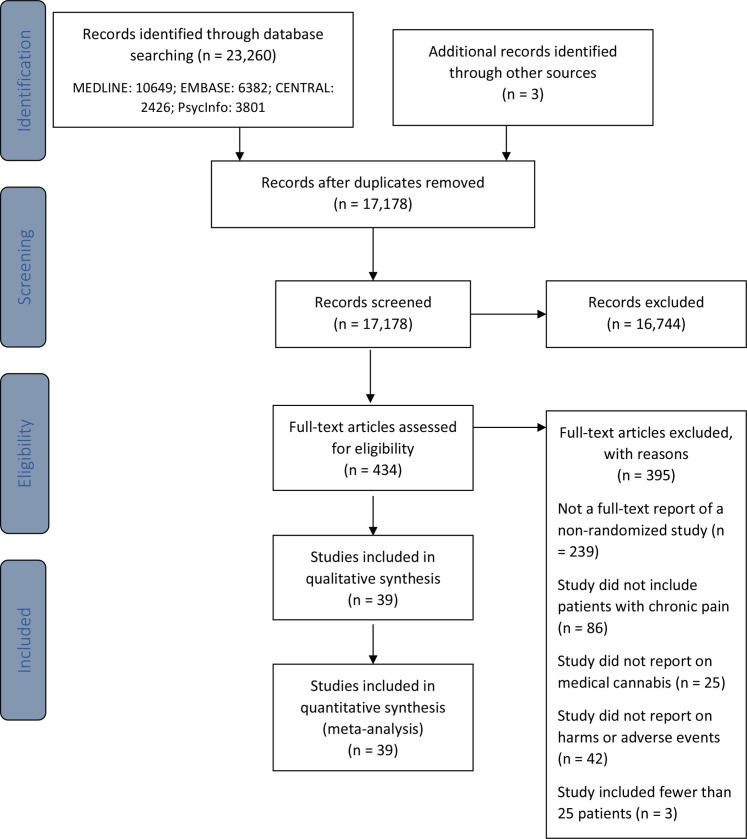

Our search yielded 17 178 unique records of which 434 were reviewed in full. We excluded more than half of references because they did not describe a non-randomised study, a quarter because they did not include patients with chronic pain, and a small minority because they did not report on adverse events. Of these records, 39 non-randomised studies were eligible for review (online supplemental appendix 3).36–74 Figure 1 presents additional details related to study selection. Online supplemental appendix 4 presents studies excluded at the full-text screening stage and accompanying reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Description of studies

One study was published in German and the remainder in English. Studies included 12 143 adults living with chronic pain and included a median of 100 (IQR 34–361) participants (table 1). Most studies (30/39; 76.9%) were longitudinal in design. Eighteen studies (46.2%) were conducted in Western Europe, 14 (35.9%) in North America, 6 (15.4%) in Israel and 2 (5.1%) in the UK. Ten studies (25.6%) were funded by industry alone or industry in combination with government and institutional funds; the remainder were funded either by governments, institutions, or not-for-profit organisations (n=9; 23.1%), did not receive funds (n=3; 7.7%) or did not report funding information (n=17; 43.6%).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study | Design | Country | Condition | Cannabis/ comparator | Dose | # of participants | Duration of cannabis use (weeks) |

| Ware et al36 | Cross-sectional* | Canada | Mixed non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) | Frequency: rarely (n=9), weekly (n=8), daily (n=5), >once daily (n=7) dose: 1–2 puffs (n=4), 3–4 puffs (n=13), whole joint (n=8), more than one joint (n=4) | 32 | NR |

| Lynch et al37 | Longitudinal* | Canada | Mixed non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 2.5 g/day | 30 | Mean: 94.4 |

| Rog et al38 | Longitudinal* | UK | Multiple sclerosis | Nabiximols (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 7.5 sprays/day | 63 | 66.1 |

| Weber et al39 | Longitudinal*† | Germany | Mixed non-cancer pain | Dronabinol (THC) | Median: 7.5 mg/day | 172 | Mean: 31 |

| Bestard and Toth40 | Longitudinal* | Canada | Peripheral neuropathic pain | Nabilone (THC) |

Mean: 3.0 mg/day | 104 | 24 |

| Gabapentin | Mean: 2.3 g/day | 107 | |||||

| Fiz et al41 | Cross-sectional* | Spain | Fibromyalgia | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

~1 to 2 cigarettes or spoonful daily (n=12) once every 2 to 4 days (n=5), less than twice a week (n=3), or occasionally (n=8) | 28 | <52 (n=11), 52 to 156 (n=9), >156 weeks (n=8) |

| Dominguez et al42 | Longitudinal* | Spain | Lumbosciatica | PEA | 300 mg twice daily | 64 | 4 |

| Gatti et al43 | Longitudinal | Italy | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | PEA | 600 mg twice daily 3 weeks; 600 mg/day for 4 weeks | 564 | 7 |

| Toth et al44 | Longitudinal*† | Canada | Diabetic peripheral neuropathy | Nabilone (THC) | mean: 2.85 mg/day | 37 | 4 |

| Schifilliti et al45 | Longitudinal | Italy | Diabetic neuropathy | PEA | 300 mg twice daily | 30 | 8.6 |

| Storr et al46 | Cross-sectional* | Canada | Crohn’s disease (n=42), ulcerative colitis (n=10), indeterminate colitis (n=4) | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

NR | 56 | <4 (n=3), 4–24 (n=9), 24 to 52 (n=5), >52 (n=32) |

| Del Giorno et al47 | Longitudinal† | Italy | Fibromyalgia | PEA | 600 mg twice daily first month; 300 mg twice daily in the next 2 months | 35 | 12 |

| Hoggart et al48 | Longitudinal | UK, Czech Republic, Romania, Belgium, Canada | Diabetic neuropathy | Nabiximols (CBD +THC) |

Median: 6 to 8 sprays/day | 380 | Median: 35.6 |

| Ware et al49 | Longitudinal*† | Canada | Mixed non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Median: 2.5 g/day | 215 | 52 |

| Standard care | 216 | ||||||

| Haroutounian et al50 | Longitudinal* | Israel | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 43.2 g/month | 206 | 30 |

| Bellnier et al51 | Longitudinal* | USA | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Capsule: 10 mg /8 to 10 hours Inhaler for breakthrough pain: 2 mg THC, 0.1 mg CBD; 1 to 5 puffs every 15 min until pain relief; could be used every 4 to 6 hours |

29 | 12 |

| Cranford et al52 | Cross-sectional* | USA | Mixed non-cancer pain | NR | 0 (n=69), <1/8 oz/week (n=130), 1/8 to 1/4 oz/week (n=156), 1/4 to 1/2 oz/week (n=179), 1/2 to 1 oz/week (n=122), 1 or more oz/week (n=115) | 775 | NR |

| Fanelli et al53 | Longitudinal | Italy | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 69.5 mg/day bediol; 67.0 mg/day bedrocan | 341 | Mean: 14.01 |

| Feingold et al54 | Cross-sectional* | Israel | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

NR | 406 | NR |

| Paladini et al55 | Longitudinal | Italy | Failed back surgery syndrome | PEA | 600 mg twice daily for 1 month; 600 mg/day for 1 month | 35 | 8 |

| Passavanti et al56 | Longitudinal | Italy | Lower back pain | PEA | 600 mg twice daily | 30 | 24 |

| Schimrigk et al57 | Longitudinal*† | Germany, Austria | Multiple sclerosis | Dronabinol (THC) | Range: 7.5–15 mg/day | 209 | 32 |

| Chirchiglia et al58 | Longitudinal | Italy | Lower back pain | PEA | 1.2 g/day | 100 | 4 |

| Crowley et al59 | Longitudinal* | USA | Mixed non-cancer pain | Trokie lozenges (CBD +THC) |

NR | 35 | 4–60 |

| Habib and Artul60 | Longitudinal* | Israel | Fibromyalgia | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 26 g/month | 26 | Mean: 41.6 |

| Anderson et al61 | Longitudinal* | USA | Cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

NR | 1120 | 16 |

| Bonar et al62 | Cross-sectional | USA | Mixed non-cancer pain | NR | 0 (n=95), <1/8 oz/week (n=126), 1/8 to 1/4 oz/week (n=158), 1/4 to 1/2 oz/week (n=174), 1/2 to 1 oz/week (n=119), 1 or more oz/week (n=119) | 790 | NR |

| Cervigni et al63 | Longitudinal† | Italy | Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome | PEA | 400 mg m-PEA plus 40 mg polydatin twice daily for 3 months, od for 3 months | 32 | 24 |

| Cremer-Schaeffer et al64 | Longitudinal | Germany | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Dronabinol (THC) |

NR | 2017 | 52 |

| Mixed herbal | NR | 656 | |||||

| Nabiximols | NR | 393 | |||||

| Lejczak et al65 | Longitudinal† | France | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Dronabinol (THC) |

Range: 2.5 to 30 mg/day | 148 | Range: 4–24 weeks |

| Loi et al66 | Longitudinal* | Italy | Endometriosis | PEA | 600 mg/twice daily for 10 days; 400 mg m-PEA plus 40 mg polydatin twice daily | 28 | 12.9 |

| Naftali et al67 | Longitudinal* | Israel | Inflammatory bowel disease | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 31 g/month mean: 21 g/day THC; 170 g/day CBD | 127 | Median: 176 |

| Perron et al68 | Cross-sectional* | USA | Mixed non-cancer pain | NR | Daily (n=580), weekly (n=85) | 618 | ≥12 |

| Sagy et al69 | Longitudinal | Israel | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Median: 1000 mg/day cannabis median: 140 mg/day THC; 39 mg/day CBD | 239 | 24 |

| Sinclair et al70 | Cross-sectional* | Australia | Endometriosis | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

Less than once per week (n=12), once per week (n=6), two to six times per week (n=9), daily or multiple times per day (n=21) | 48 | NR |

| Ueberall et al71 | Longitudinal* | Germany | Mixed cancer and non-cancer pain | Nabiximols (CBD +THC) |

Mean: 7.1 sprays/day | 800 | 12 |

| Vigil et al72 | Longitudinal* | USA | Mixed non-cancer pain | NR | NR | 37 | Mean: 82.4 |

| Yassin et al73 | Longitudinal | Israel | Fibromyalgia | Mixed herbal (CBD +THC) |

20 to 30 g/month | 31 | 24 |

| Giorgi et al74 | Longitudinal | Italy | Fibromyalgia | Extracts (CBD +THC) |

ten to 30 drops/day; no more than 120 drops/day | 102 | 24 |

*Patient report.

†Clinician report.

CBD, cannabidiol; NR, not reported; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Thirty studies (76.9%) reported on people living with chronic non-cancer pain, eight (n=20.5%) with mixed cancer and non-cancer chronic pain, and one (2.6%) with chronic cancer pain. All studies reported on adults. Sixteen studies reported on mixed types of herbal cannabis (eg, buds for smoking, vaporising and ingesting, hashish, oils, extracts, edibles), nine on palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), four each on nabiximols and dronabinol, two on nabilone, one each on Trokie lozenges and extracts, and four did not report the type of medical cannabis used. Herbal cannabis, lozenges, extracts and nabiximols are mixed CBD and THC products whereas nabilone and dronabinol only contain THC. One study reported on three types of medical cannabis (dronabinol, nabiximols, and mixed herbal) separately. The median duration of medical cannabis use was 24 weeks (IQR 12.0–33.8 weeks). Two studies were comparative: one study compared nabilone with gabapentin and another compared herbal cannabis with standard care.40 49 Studies reported a total of 525 unique adverse events.

Risk of bias

Online supplemental appendix 5 presents the risk of bias of included studies. We rated all results at critical risk of bias except for the comparative results from two studies,40 49 which were rated at serious and moderate risk of bias. The primary limitation across studies was inadequate control for potential confounding either due to the absence of a control group or inadequate adjustment for confounders. A third of studies were rated at serious risk of bias for selection bias, primarily because they included prevalent users of medical cannabis. Such studies may underestimate the incidence of adverse events since patients that experience adverse events are more likely to discontinue medical cannabis early. Such studies may also include adverse events that may have been present at inception and that are unrelated to medical cannabis use.

All adverse events

Twenty longitudinal and two cross-sectional studies, including 4108 patients, reported the number of patients experiencing one or more adverse events.37–44 47 48 55 57–61 63 65 66 70 71 74 Seven studies reported on PEA, five on mixed herbal cannabis, three each on nabilone and nabiximols, two on dronabinol and one each on extracts and Trokie lozenges. The median duration of medical cannabis use was 24 weeks (IQR 12–32). We observed substantial unexplained heterogeneity and so summarise the results descriptively (table 2; online supplemental appendices 6–9). The prevalence of any adverse event ranged between 0% and 92.1%. Studies with less than 24 weeks of cannabis use (the median duration of cannabis) typically reported fewer adverse events than those with more than 24 weeks. Patients using PEA experienced no adverse events. The evidence was overall very uncertain due to risk of bias and inconsistency.

Table 2.

Prevalence of adverse events from non-comparative studies

| Outcome | No of studies | No of participants | Duration of follow-up (weeks) | Prevalence % (95% CI) | I2 (τ2) |

Certainty | Reasons for downgrading |

| All adverse events | 22 | 4108 | 4–94 | The prevalence of adverse events ranged between 0% and 92.1%. Studies with less than 24 weeks of cannabis use typically reported fewer adverse events than those with more than 24 weeks. Patients using PEA experienced no adverse events. The evidence was overall very uncertain due to risk of bias and inconsistency. | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), inconsistency | |

| Adverse events causing discontinuation | 20 | 6509 | 4–66 | The prevalence of discontinuations due to adverse events ranged between 0% and 27.0%. Studies with less than 24 weeks of cannabis use typically reported fewer discontinuations than those with more than 24 weeks. Patients using PEA experienced no adverse events. The evidence was overall very uncertain due to risk of bias and inconsistency. | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), inconsistency | |

| Serious adverse events | 24 | 4273 | 4–94 | 1.2 (0.1 to 3.1) | 91 (0.01273) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Psychiatric adverse events | |||||||

| Psychiatric disorder | 4 | 1458 | 12–66 | 13.5 (2.6 to 30.6) | 98 (0.0436) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), inconsistency, imprecision |

| Suicide | 1 | 215 | 52 | 0 (0 to 0.8) | NA | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Suicidal thoughts | 1 | 3066 | 52 | 0.1 (0 to 0.5) | 44 (0.0003) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Depression | 6 | 4144 | 12–66 | 1.7 (0.9 to 2.7) | 71 (0.0011) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Mania | 1 | 215 | 52 | 0.5 (0 to 2) | NA | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Hallucinations | 6 | 3583 | 24–66 | 0.5 (0.1 to 1.3) | 69 (0.0012) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Delusions | 4 | 3281 | 52 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0 (0) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Paranoia | 3 | 277 | 52–94; one cross-sectional study | 5.6 (0 to 19.2) | 85 (0.0266) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), inconsistency, imprecision |

| Anxiety | 5 | 1695 | 12–94; two cross-sectional studies | 7.4 (0 to 26.9) | 99 (0.0859) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), imprecision |

| Euphoria | 7 | 4501 | 4–66 | 2.1 (0.9 to 3.8) | 96 (0.0028) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Cognitive adverse events | |||||||

| Memory impairment | 6 | 4484 | 4–176 | 5.3 (2.1 to 9.6) | 96 (0.0126) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Confusion | 7 | 1654 | 4–176 | 1.8 (0.3 to 4.2) | 81 (0.0056) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Disorientation | 6 | 4485 | 12–52 | 1.6 (0.6 to 3.0) | 88 (0.0028) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Attention disorder or deficit | 8 | 5477 | 12–82 | 3.4 (1.3 to 6.3) | 95 (0.0082) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Accidents and injuries | |||||||

| Falls | 1 | 215 | 52 | 2.3 (0.7 to 4.9) | NA | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Motor vehicle accidents | 1 | 215 | 52 | 0.5 (0 to 2.0) | NA | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels) |

| Dependence and withdrawal | |||||||

| Dependence | 3 | 1824 | 12; one cross-sectional study | 4.4 (0.0 to 19.9) | 99 (0.0488) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness |

| Withdrawal syndrome | 2 | 424 | 32–52 | 2.1 (0 to 8.2) | 89 (0.0091) | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), indirectness |

| Withdrawal symptoms | 1 | 618 | NA; cross-sectional | 67.8 (64.1 to 71.4) | NA | Very low | Risk of bias (three levels), indirectness |

NA, not available; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide.

One study suggested that nabilone may reduce the risk of adverse events compared with gabapentin (−13.1%; 95% CI −26.2% to 0%), but the certainty of evidence was very low due to risk of bias and imprecision (table 3).

Table 3.

Risk differences for adverse events from comparative studies

| Outcome | Exposure | No of studies | No of participants | Follow-up (weeks) | Risk with cannabis (/1000) | Risk with comparator (/1000) | Risk difference (95% CI) | Certainty | Reasons for downgrading |

| All adverse events | Nabilone versus gabapentin | 1 | 220 | 24 | 404 | 534 | −13.1% (−26.2 to 0) | Very low | Risk of bias (two levels), imprecision |

| Adverse events causing discontinuation | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 47 | 0 | 4.7% (1.8 to 7.5) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels), |

| Nabilone versus gabapentin | 1 | 220 | 24 | 96 | 190 | −9.4% (−18.5 to -0.2) | Very low | Risk of bias (two levels), imprecision | |

| Serious | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 130 | 194 | 1.5% (−8.3 to 20.2)* | Low | Risk of bias, imprecision |

| Nabilone versus gabapentin | 1 | 220 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0% (0 to 0) | Very low | Risk of bias (two levels), imprecision | |

| Psychiatric disorder | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 219 | 97 | 16.9% (5.8 to 40.5)† | Very low | Risk of bias (two levels), imprecision |

| Suicide | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 0 | 5 | −0.5% (−1.4 to 0.4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Mania | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 5 | 0 | 0.5% (−0.4 to 1.4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Hallucinations | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 5 | 0 | 0.5% (−0.4 to 1.4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Delusions | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 0 | 5 | −0.5% (−1.4 to 0.4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Depression | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 47 | 46 | 0.1% (−4 to 4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Paranoia | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 9 | 0 | 0.9% (−0.4 to 2.2) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Anxiety | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 47 | 9 | 3.8% (0.6 to 6.8) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Euphoria | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 42 | 0 | 4.2% (1.5 to 6.9) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Memory impairment | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 19 | 0 | 1.9% (0.1 to 3.7) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Confusion | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 14 | 19 | −0.5% (−2.8 to 1.9) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Disturbance in attention | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 23 | 9 | 1.4% (−1 to 3.8) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Falls | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 23 | 23 | 0% (−2.8 to 2.9) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Motor vehicle accidents | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 5 | 0 | 0.5% (−0.4 to 1.4) | Low | Risk of bias (two levels) |

| Withdrawal syndrome | Herbal cannabis versus standard care | 1 | 431 | 52 | 5 | 0 | 0.5% (−0.4 to 1.4) | Very low | Risk of bias (two levels), |

*Risk difference calculated from adjusted incident rate ratio reported in study.

†Risk difference calculated from unadjusted incident rate ratio reported in study.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation

Twenty longitudinal studies, including 6509 patients, reported on the number of patients that discontinued medical cannabis or cannabinoids due to adverse events.38 40 42–45 47–50 53 55 57 58 60 63 64 66 71 74 Eight studies reported on PEA, four studies on mixed herbal cannabis, three on nabiximols, two on nabilone, and one each on dronabinol and extracts, and one study did not report the type of medical cannabis used by patients. The median duration of cannabis use was 24 weeks (IQR 8.6–32). We observed substantial unexplained heterogeneity and so summarise the results descriptively (online supplemental appendices 10–12). The prevalence of discontinuations due to adverse events ranged between 0% and 27.0%. Studies with less than 24 weeks of cannabis use typically reported fewer discontinuations than those with more than 24 weeks. Patients using PEA experienced no adverse events. The evidence was overall very uncertain due to risk of bias and inconsistency.

One study suggested herbal cannabis may increase the risk of adverse events leading to discontinuation compared with standard care without cannabis (4.7%; 95% CI 1.8% to 7.5%). Another study suggested that nabilone may reduce the risk of adverse events leading to discontinuation compared with gabapentin (−9.4%; 95% CI −18.5% to −0.2%). The certainty of evidence was low to very low due to risk of bias and imprecision.

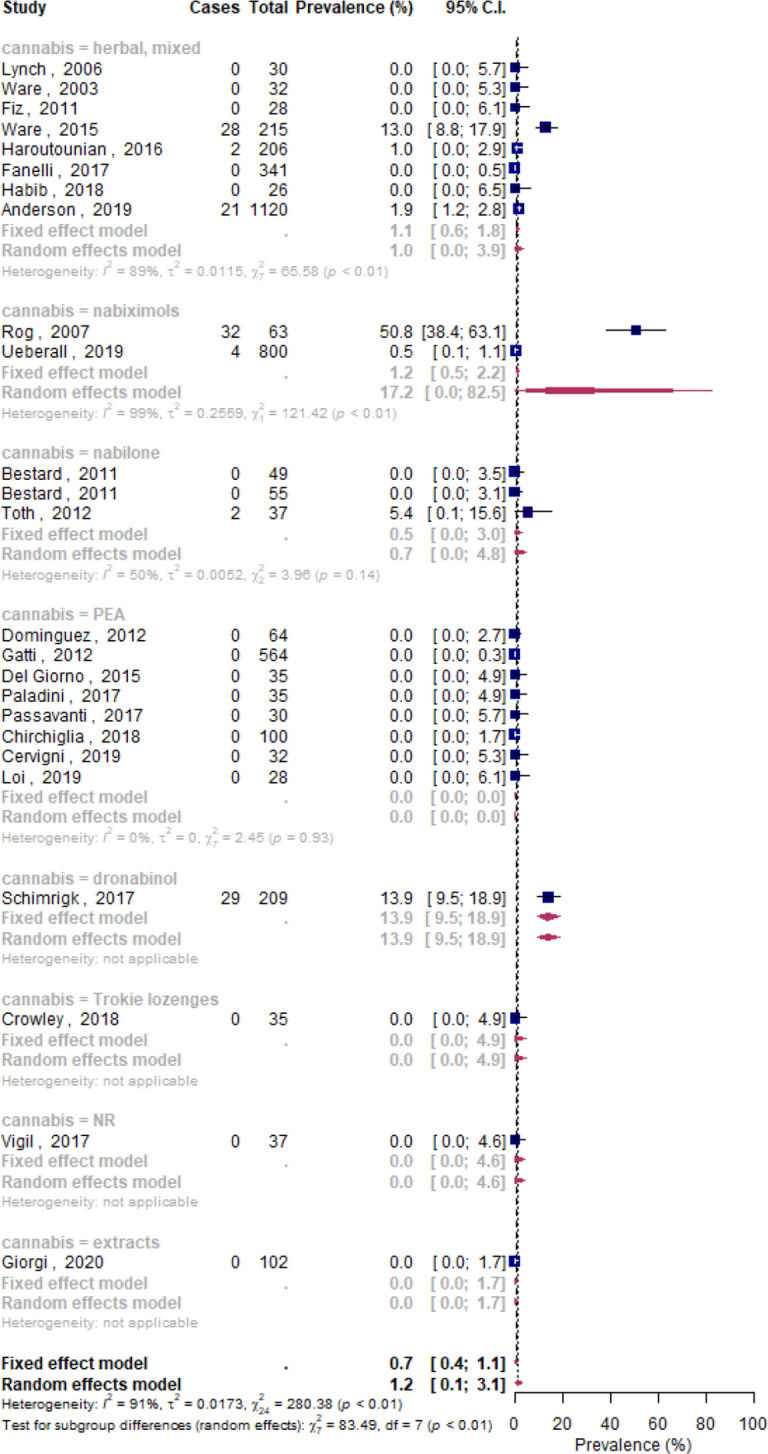

Serious adverse events

Twenty-two longitudinal and two cross-sectional studies, including 4273 patients, reported on the number of patients experiencing one or more serious adverse events.36–38 40–44 47 49 50 53 55–61 63 66 71 72 74 Eight studies reported on mixed herbal cannabis, eight on PEA, two each on nabilone and nabiximols each, and one study each on dronabinol, extracts and Trokie lozenges, and one study did not report the type of cannabis used. The median duration of medical cannabis or cannabinoid use was 24 weeks (IQR 12–32), and few patients experienced serious adverse events (1.2%; 95% CI 0.1% to 3.1%; I2=91%) (figure 2) (online supplemental appendices 13–15). There was a statistically significant subgroup effect across different types of medical cannabis though serious adverse events appeared consistently uncommon (low credibility). The certainty of evidence was very low overall due to serious risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis for serious adverse events stratified by type of medical cannabis. NR, not reported.

One study suggested use of herbal cannabis may make little to no difference in the risk of serious adverse events compared with standard care without cannabis (1.5%; 95% CI −8.3% to 20.2%). Another study found use of nabilone versus gabapentin may make little to no difference in the risk of serious adverse events. The certainty of evidence was low to very low for both studies due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Psychiatric adverse events

Eleven longitudinal and two cross-sectional studies, including 6600 patients, reported on any psychiatric adverse events, including psychiatric disorders, suicide, suicidal thoughts, depression, mania, hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, anxiety and euphoria (online supplemental appendices 16–25).36–38 44 48 49 61 64 68 69 71 Five studies reported on mixed herbal cannabis, four on nabiximols, one each on dronabinol, nabilone, and mixed types and one study did not specify the type of medical cannabis. The median duration of cannabis use across studies was 52 weeks (IQR 20–52). Approximately one in seven medical cannabis users experienced one or more psychiatric disorders or adverse events (13.5%; 95% CI 2.6% to 30.6%; I2=98%). The most frequently occurring psychiatric adverse events were paranoia (5.6%; 9% CI 0% to 19.2%; I2=85%) and anxiety (7.4%; 95% CI 0% to 26.9%; I2=99%). The certainty of evidence was very low due to risk of bias, inconsistency (for psychiatric disorders and paranoia) and imprecision (for psychiatric disorder, paranoia and anxiety).

One study suggested that herbal cannabis may result in a trivial to moderate increase in the risk for psychiatric disorders, mania, hallucinations, depression, paranoia, anxiety, and euphoria and a reduction in the risk for suicides and delusions, compared with standard care without cannabis, though the certainty of evidence was low to very low due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Cognitive and attentional adverse events

Eleven longitudinal studies, including 6257 patients, reported on cognitive adverse events, including memory impairment, confusion, disorientation and impaired attention (online supplemental appendices 26–29).36–38 44 48 49 61 64 68 69 71 Five studies reported on herbal cannabis, three on nabiximols, three on mixed types of cannabis, and one each on dronabinol and nabilone. The median duration of cannabis use was 52 weeks (IQR 24–52). The prevalence of cognitive adverse events ranged from 1.6% (95% CI 0.6% to 3.0%; I2=88%) for disorientation to 5.3% (95% CI 2.1% to 9.6%; I2=96%) for memory impairment. The certainty of evidence was very low due to risk of bias.

One study suggested herbal cannabis may slightly increase the risk for memory impairment and disturbances in attention compared with standard care without cannabis, but reduce the risk for confusion, though the certainty of evidence was low to very low due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Accidents and injuries

One longitudinal study, including 431 patients, reported on accidents and injuries in patients using mixed herbal cannabis for 52 weeks (online supplemental appendices 30 and 31).49 This study suggested herbal cannabis used for medical purposes may slightly increase the risk of motor vehicle accidents (0.5%; 95% CI −0.4% to 1.4%) but may not increase the risk of falls (0%; 95% CI −2.8% to 2.9%). The certainty of evidence was low due to risk of bias.

Dependence and withdrawal

Four longitudinal and one cross-sectional study, including 2248 patients, reported on dependence-related adverse events, including dependence (one study reported on ‘abuse’ based on unspecified criteria, one study reported on ‘problematic use’ using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition,75 and one study reported on ‘dependence’ using the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test,76 withdrawal symptoms (defined as one or moderate or severe withdrawal symptoms including sleep difficulties, anxiety, irritability and appetite disturbance), and withdrawal syndrome (two studies that used unspecified criteria) (online supplemental appendices 32–34).49 54 57 68 71 Two studies reported on herbal cannabis, one each on nabiximols and nabilone, and one did not specify type of medical cannabis used by patients. Follow-up ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. The pooled prevalence of dependence was 4.4% (95% CI 0.0% to 19.9%; I2=99%) and 2.1% (95% CI 0% to 8.2%; I2=89%) for withdrawal syndrome; however, withdrawal symptoms were much more common (67.8%; 95% CI 64.1% to 71.4%). The certainty of evidence was very low due to risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision (for dependence) and indirectness due to vagueness of definitions in studies that precluded confident distinguishment between dependence, addiction, withdrawal symptoms and withdrawal syndrome.

One study suggested that herbal cannabis compared with standard care may slightly increase the risk of withdrawal syndrome (0.5%; 95% CI −0.4% to 1.4%) but the certainty of evidence was low due to risk of bias.

Discussion

Main findings

Our systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that adverse events are common among people living with chronic pain who use medical cannabis or cannabinoids, with approximately one in four experiencing at least one adverse event—though the certainty of evidence is very low and the true prevalence of adverse events may be substantially different. In contrast, serious adverse events, adverse events leading to discontinuation, cognitive adverse events, accidents and injuries, and dependence and withdrawal syndrome are less common. We compared studies with <24 weeks and ≥24 weeks cannabis use and found more adverse events reported among studies with longer follow-up. This may be explained by increased tolerance (tachyphylaxis) with prolonged exposure, necessitating increases in dosage with consequent increased risk of harms. PEA, compared with other formulations of medical cannabis, may result in the fewest adverse events. Though adverse events associated with medical cannabis appear to be common, few patients discontinued use due to adverse events suggesting that most adverse events are transient and/or outweighed by perceived benefits.

Our review represents the most comprehensive review of evidence from non-randomised studies addressing adverse events of medical cannabis or cannabinoid use in people living with chronic pain. While several previous reviews have summarised the evidence on short-term and common adverse events of medical cannabis reported in randomised trials, such as oral discomfort, dizziness and headaches, our review focuses on serious and rare adverse events—the choice of which was informed by a panel including patients, clinicians, and methodologists—and non-randomised studies, which typically follow larger numbers of patients for longer periods of time and thus may detect adverse events that are infrequent or that are associated with longer durations of cannabis use.10 77–81 A parallel systematic review of evidence from randomised controlled trials found no evidence to inform long-term harms of medical cannabis as no eligible trial followed patients for more than 5.5 months.11 One previously published review that included non-randomised studies searched the literature until 2007, included studies exploring medical cannabis for any indication (excluding synthetic cannabinoids) of which only two enrolled people living with chronic pain.12 This review did not synthesise adverse event data from non-randomised studies.12 Unlike previous reviews, we focused exclusively on medical cannabis for chronic pain and excluded recreational cannabis, because cannabis used for recreational purposes often contains higher concentrations of THC than medical cannabis. We focused on chronic pain because this patient population may be susceptible to different adverse events. Depression and anxiety, for example, are commonly occurring comorbidities of chronic pain, which may be exacerbated by cannabis.15–17

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this systematic review and meta-analysis include a comprehensive search for non-randomised studies, explicit eligibility criteria, screening of studies and collection of data in duplicate to increase reliability, and use of the GRADE approach to evaluate the certainty of evidence.

Our review is limited by the non-comparative design of most studies, which precludes confident inferences regarding the proportion of adverse events that can be attributed to medical cannabis or cannabinoids and the magnitude by which medical cannabis may increase or decrease the risk of adverse events compared with other pain management options. Though adverse events appear common among medical cannabis users, it is possible that other management options for chronic pain, particularly opioids, may be associated with more (and more severe) adverse events.82 Partly due to the non-comparative design of most studies, nearly all results included in our review were at serious or critical risk of bias for confounding and Simpson’s paradox,83 either due to the absence of a control group or due to insufficient adjustment for important confounders. Further, one-third of studies were at high risk of selection bias, primarily because they included prevalent cannabis users. In such studies, the prevalence of adverse events may be underestimated. Our review provides limited evidence on the harms of medical cannabis beyond 1 year of use since most studies reported adverse events for less than 1 year of follow-up.

We observed some inconsistency for many adverse events of interest and substantial inconsistency for all adverse events and adverse events leading to discontinuation. We downgraded the certainty of evidence when we observed important inconsistency and we did not present estimates from meta-analyses for all adverse events and adverse events leading to discontinuation due to substantial inconsistency. Further, some analyses included too few studies or participants, due to which estimates were imprecise.

Sixteen of 39 studies reported on herbal medical cannabis, some of which were consumed by smoking or vaporising, and may be associated with different adverse events (eg, respiratory) than other formulations of medical cannabis. We attempted to perform subgroup analyses based on the type of medical cannabis. Results for subgroups, however, lacked credibility due to inconsistency and/or imprecision.

Clinicians and patients may be more inclined to use medical cannabis or cannabinoids for pain relief if adverse events are mild; however, the evidence on whether adverse events are transient, life-threatening, or the extent to which they impact quality of life is limited. While more than half of studies reported on the proportion of adverse events that were serious, criteria for ascertaining severity were rarely reported. None of the included studies reported the duration for which patients experienced adverse events. Further, most primary studies did not report adequate details on methods for the ascertainment of adverse events, including definitions or diagnostic criteria. The two studies that reported on withdrawal syndrome, for example, did not provide diagnostic criteria.49 57 However, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) requires ≥3 of 7 withdrawal symptoms to be present within a week of stopping cannabis use to meet a diagnosis of cannabis withdrawal syndrome.84 It is therefore reasonable that people living with chronic pain that use medical cannabis would be more likely to experience withdrawal symptoms vs withdrawal syndrome.

While children and youth account for approximately 15% of all chronic pain patients, we did not identify any evidence addressing the harms of medical cannabis in this population.85 As such, the extent to which our findings are generalisable to paediatric populations is uncertain. Although there is evidence that cannabis use during youth is associated with increased risk of acute psychotic disorders, particularly acute psychosis,86 such studies have focused on use of recreational cannabis that contains greater amounts of THC than is typically seen in medical preparations. Further, the population of patients with chronic pain included in the studies we reviewed may not be representative of all patients with chronic pain—particularly rare conditions that cause chronic pain.

We used the DerSimonian and Laird method for meta-analysis.27 A growing body of evidence, however, suggests that this model has important limitations that may be addressed by alternative models87—though there is limited evidence on the performance of these models for meta-analyses of proportions and prevalence.

Finally, we excluded studies from meta-analyses when they did not explicitly report the adverse events of interest to our panel members. This may have overestimated the prevalence of adverse events if the adverse events of interest were not observed in the studies in which they were not reported. This was, however, not possible to confirm because methods for the collection and reporting of adverse event data across studies were variable (eg, active monitoring vs passive surveillance; collecting data on specific adverse events vs all adverse events) and poorly described in study reports.

Implications

Our systematic review and meta-analysis shows that evidence regarding long-term and serious harms of medical cannabis or cannabinoids is insufficient—an issue with important implications for patients and clinicians considering this management option for chronic pain. While the evidence suggests that adverse events are common in patients using medical cannabis for chronic pain, serious adverse events appear less common, which suggests that the potential benefits of medical cannabis or cannabinoids (although modest) may outweigh potential harms for some patients.11 18

Clinicians and patients considering medical cannabis should be aware that more adverse events were reported among studies with longer follow-up, necessitating long-term follow-up of patients and re-evaluation of pain treatment options. Our findings also have implications for the choice of medical cannabis. We found PEA, for example, to consistently be associated with few or no adverse events across studies, though the evidence on the efficacy of PEA is limited.11

We found very limited evidence comparing medical cannabis or cannabinoids with other pain management options. Other pharmacological treatments for chronic pain, such as gabapentinoids, antidepressants and opioids, may be associated with more (and more serious) adverse events.88–90 To guide patients’ and clinicians’ decisions on medical cannabis for chronic pain, future research should compare the harms of medical cannabis and cannabinoids with other pain management options, including opioids, ideally beyond 1 year of use, and adjust results for confounders.

Our review highlights the need for standardisation of reporting of adverse events in non-randomised studies since such studies represent a critical source of data on long-term and infrequently occurring harms. To enhance the interpretability of adverse event data, future studies should also report the duration and severity of adverse events and whether adverse events are life-threatening, since these factors are critical to patients’ decisions.

A valuable output of our systematic review is an open-source database of over 500 unique adverse events reported to date in non-randomised studies of medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain with corresponding assessments of risk of bias (https://osf.io/ut36z/). This database was compiled in duplicate by trained and calibrated data extractors and is freely available to those interested in further analysing the prevalence of different types of adverse events or to those interested in expanding the database to include adverse events in patients using medical cannabis or cannabinoids for other indications.

Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis found very low certainty evidence that suggests adverse events are common among people living with chronic pain using medical cannabis or cannabinoids, but that serious adverse events, adverse events causing discontinuation, cognitive adverse events, motor vehicle accidents, falls, and dependence and withdrawal syndrome are less common. We also found very low certainty evidence that longer duration of use was associated more adverse events and that PEA, compared with other types of medical cannabis, may result in few or no adverse events. Future research should compare the risks of adverse events of medical cannabis and cannabinoids with alternative pain management options, including opioids and adjust for potential confounders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Rapid Recommendations panel for critical feedback on the selection of the adverse events of interest. We thank James MacKillop, PhD, for his guidance regarding the interpretation of problematic cannabis use, abuse, dependance and withdrawal syndrome within studies included in our review.

Footnotes

Twitter: @muneebahmed1a, @ThomasAgoritsas, @JasonWBusse

Contributors: JWB and TA conceived the idea. RC designed and conducted the search. DZ, MAC, AA, RWMV, GL, KL, JED, MMA, BYH, CH and PH screened search records, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias of the eligible studies. DZ conducted all analyses. DZ, JWB and TA interpreted the data. DZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JWB and TA critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version. DZ and JWB are the guarantors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available in a public, open access repository: https://osf.io/ut36z/

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth 2019;123:e273–83. 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills SEE, van Hecke O, Smith BH. Handbook of pain and palliative care: biopsychosocial and environmental approaches for the life course, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keyhani S, Steigerwald S, Ishida J, et al. Risks and benefits of marijuana use: a national survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:282–90. 10.7326/M18-0810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai H, Richter KP. A national survey of marijuana use among US adults with medical conditions, 2016-2017. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1911936. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health . The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr D, Schatman M. Cannabis for chronic pain: not ready for prime time. Am J Public Health 2019;109:50–1. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziemianski D, Capler R, Tekanoff R, et al. Cannabis in medicine: a national educational needs assessment among Canadian physicians. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:52. 10.1186/s12909-015-0335-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahan M, Srivastava A. Is there a role for marijuana in medical practice? no. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:22–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware MA. Is there a role for marijuana in medical practice? Yes. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:22–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Zoheiry N, et al. Efficacy and adverse effects of medical marijuana for chronic noncancer pain: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:e372–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Hong PJ, May C, et al. Medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic non-cancer and cancer related pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2021;64:n1034. 10.1136/bmj.n1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, Collet J-P, Shapiro S, et al. Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review. CMAJ 2008;178:1669–78. 10.1503/cmaj.071178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:2456–73. 10.1001/jama.2015.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill KP, Hurley-Welljams-Dorof WM. Low to moderate quality evidence demonstrates the potential benefits and adverse events of cannabinoids for certain medical indications. Evid Based Med 2016;21:17. 10.1136/ebmed-2015-110264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, et al. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2433–45. 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magni G, Marchetti M, Moreschi C, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the National health and nutrition examination. I. epidemiologic follow-up study. Pain 1993;53:163–8. 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D'Eon JL, et al. Major depression and insomnia in chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2002;18:77–83. 10.1097/00002508-200203000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busse JW, Vankrunkelsven P, Zeng L, et al. Medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2021;64:n2040:374. 10.1136/bmj.n2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, Macdonald H, et al. Introduction to BMJ rapid recommendations. BMJ 2016;354:i5191. 10.1136/bmj.i5191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng L, Lytvyn L, Wang X. Values and preferences towards medical cannabis among patients with chronic pain: a mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Open 2021;7;11:e050831. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noori A, Miroshnychenko A, Shergill Y. Opioid-Sparing effects of medical cannabis for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and observational studies. BMJ 2020. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zorzela L, Loke YK, Ioannidis JP, et al. PRISMA harms checklist: improving harms reporting in systematic reviews. BMJ 2016;352:i157. 10.1136/bmj.i157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busse JW, Bartlett SJ, Dougados M, et al. Optimal strategies for reporting pain in clinical trials and systematic reviews: recommendations from an OMERACT 12 workshop. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1962–70. 10.3899/jrheum.141440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeraatkar D, JW B. Cannabis harms in chronic pain; 2021.

- 26.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat 1950;21:607–11. 10.1214/aoms/1177729756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-Analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murad M, Montori V, Ioannidis J. Fixed-effects and random-effects models.. In: Users’ guide to the medical literature A manual for evidence-based clinical practice McGraw-Hill. 3rd ed. New York, America, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, et al. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:79. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, et al. Is a subgroup effect believable? updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ 2010;340:c117. 10.1136/bmj.c117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schandelmaier S, Briel M, Varadhan R, et al. Development of the instrument to assess the credibility of effect modification analyses (ICEMAN) in randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. Can Med Assoc J 2020;192:E901–6. 10.1503/cmaj.200077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzer G. Meta: an R package for meta-analysis. R news 2007;7:40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, et al. Grade guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;111:105–14. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. Grade: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, et al. Grade guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;119:126–35. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware MA, Doyle CR, Woods R, et al. Cannabis use for chronic non-cancer pain: results of a prospective survey. Pain 2003;102:211–6. 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00400-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch ME, Young J, Clark AJ. A case series of patients using medicinal marihuana for management of chronic pain under the Canadian marihuana medical access regulations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:497–501. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rog DJ, Nurmikko TJ, Young CA. Oromucosal delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol for neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis: an uncontrolled, open-label, 2-year extension trial. Clin Ther 2007;29:2068–79. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber J, Schley M, Casutt M. Tetrahydrocannabinol (delta 9-THC) treatment in chronic central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia patients: results of a multicenter survey. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2009;2009:9. 10.1155/2009/827290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bestard JA, Toth CC. An open-label comparison of nabilone and gabapentin as adjuvant therapy or monotherapy in the management of neuropathic pain in patients with peripheral neuropathy. Pain Pract 2011;11:353–68. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiz J, Durán M, Capellà D, et al. Cannabis use in patients with fibromyalgia: effect on symptoms relief and health-related quality of life. PLoS One 2011;6:e18440. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domínguez CM, Martín AD, Ferrer FG, et al. N-Palmitoylethanolamide in the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with lumbosciatica. Pain Manag 2012;2:119–24. 10.2217/pmt.12.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gatti A, Lazzari M, Gianfelice V, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide in the treatment of chronic pain caused by different etiopathogenesis. Pain Med 2012;13:1121–30. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toth C, Mawani S, Brady S, et al. An enriched-enrolment, randomized withdrawal, flexible-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel assignment efficacy study of nabilone as adjuvant in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 2012;153:2073–82. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schifilliti C, Cucinotta L, Fedele V, et al. Micronized palmitoylethanolamide reduces the symptoms of neuropathic pain in diabetic patients. Pain Res Treat 2014;2014:849623. 10.1155/2014/849623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storr M, Devlin S, Kaplan GG, et al. Cannabis use provides symptom relief in patients with inflammatory bowel disease but is associated with worse disease prognosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:472–80. 10.1097/01.MIB.0000440982.79036.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Giorno R, Skaper S, Paladini A, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide in fibromyalgia: results from prospective and retrospective observational studies. Pain Ther 2015;4:169–78. 10.1007/s40122-015-0038-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoggart B, Ratcliffe S, Ehler E, et al. A multicentre, open-label, follow-on study to assess the long-term maintenance of effect, tolerance and safety of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in the management of neuropathic pain. J Neurol 2015;262:27–40. 10.1007/s00415-014-7502-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware MA, Wang T, Shapiro S, et al. Cannabis for the management of pain: assessment of safety study (COMPASS). J Pain 2015;16:1233–42. 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haroutounian S, Ratz Y, Ginosar Y, et al. The effect of medicinal cannabis on pain and quality-of-life outcomes in chronic pain: a prospective open-label study. Clin J Pain 2016;32:1036–43. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellnier T, Brown GW, Ortega TR. Preliminary evaluation of the efficacy, safety, and costs associated with the treatment of chronic pain with medical cannabis. Ment Health Clin 2018;8:110–5. 10.9740/mhc.2018.05.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cranford JA, Arnedt JT, Conroy DA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sleep-related problems in adults receiving medical cannabis for chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;180:227–33. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fanelli G, De Carolis G, Leonardi C, et al. Cannabis and intractable chronic pain: an explorative retrospective analysis of Italian cohort of 614 patients. J Pain Res 2017;10:1217–24. 10.2147/JPR.S132814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feingold D, Goor-Aryeh I, Bril S, et al. Problematic use of prescription opioids and medicinal cannabis among patients suffering from chronic pain. Pain Med 2017;18:294–306. 10.1093/pm/pnw134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paladini A, Varrassi G, Bentivegna G, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide in the treatment of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Res Treat 2017;2017:1486010. 10.1155/2017/1486010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Passavanti MB, Fiore M, Sansone P, et al. The beneficial use of ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide as add-on therapy to tapentadol in the treatment of low back pain: a pilot study comparing prospective and retrospective observational arms. BMC Anesthesiol 2017;17:171. 10.1186/s12871-017-0461-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schimrigk S, Marziniak M, Neubauer C, et al. Dronabinol is a safe long-term treatment option for neuropathic pain patients. Eur Neurol 2017;78:320–9. 10.1159/000481089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chirchiglia D, Chirchiglia P, Signorelli F. Nonsurgical lumbar radiculopathies treated with ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide (umPEA): a series of 100 cases. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2018;52:44–7. 10.1016/j.pjnns.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crowley K, de Vries ST, Moreno-Sanz G. Self-Reported Effectiveness and Safety of Trokie® Lozenges: A Standardized Formulation for the Buccal Delivery of Cannabis Extracts. Front Neurosci 2018;12:564. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Habib G, Artul S. Medical cannabis for the treatment of fibromyalgia. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2018;24:255–8. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson SP, Zylla DM, McGriff DM, et al. Impact of medical cannabis on patient-reported symptoms for patients with cancer enrolled in Minnesota's medical cannabis program. J Oncol Pract 2019;15:e338–45. 10.1200/JOP.18.00562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bonar EE, Cranford JA, Arterberry BJ, et al. Driving under the influence of cannabis among medical cannabis patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;195:193–7. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cervigni M, Nasta L, Schievano C, et al. Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide-Polydatin reduces the painful symptomatology in patients with interstitial Cystitis/Bladder pain syndrome. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:9828397:1–6. 10.1155/2019/9828397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cremer-Schaeffer P, Schmidt-Wolf G, Broich K. [Cannabis medicines in pain management : Interim analysis of the survey accompanying the prescription of cannabis-based medicines in Germany with regard to pain as primarily treated symptom]. Schmerz 2019;33:415–23. 10.1007/s00482-019-00399-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lejczak S, Rousselot H, Di Patrizio P, et al. Dronabinol use in France between 2004 and 2017. Rev Neurol 2019;175:298–304. 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stochino Loi E, Pontis A, Cofelice V, et al. Effect of ultramicronized-palmitoylethanolamide and co-micronized palmitoylethanolamide/polydatin on chronic pelvic pain and quality of life in endometriosis patients: an open-label pilot study. Int J Womens Health 2019;11:443–9. 10.2147/IJWH.S204275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naftali T, Bar-Lev Schleider L, Sklerovsky Benjaminov F, et al. Medical cannabis for inflammatory bowel disease: real-life experience of mode of consumption and assessment of side-effects. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;31:1376–81. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perron BE, Holt KR, Yeagley E, et al. Mental health functioning and severity of cannabis withdrawal among medical cannabis users with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;194:401–9. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sagy I, Bar-Lev Schleider L, Abu-Shakra M, et al. Safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in fibromyalgia. J Clin Med 2019;8:807. 10.3390/jcm8060807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sinclair J, Smith CA, Abbott J, et al. Cannabis use, a self-management strategy among Australian women with endometriosis: results from a national online survey. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020;42:256–61. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ueberall MA, Essner U, Mueller-Schwefe GH. Effectiveness and tolerability of THC:CBD oromucosal spray as add-on measure in patients with severe chronic pain: analysis of 12-week open-label real-world data provided by the German Pain e-Registry. J Pain Res 2019;12:1577–604. 10.2147/JPR.S192174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vigil JM, Stith SS, Adams IM, et al. Associations between medical cannabis and prescription opioid use in chronic pain patients: a preliminary cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187795. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yassin M, Oron A, Robinson D. Effect of adding medical cannabis to analgesic treatment in patients with low back pain related to fibromyalgia: an observational cross-over single centre study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37 Suppl 116:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giorgi V, Bongiovanni S, Atzeni F, et al. Adding medical cannabis to standard analgesic treatment for fibromyalgia: a prospective observational study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38 Suppl 123:53–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003;71:7–16. 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Humeniuk R, Ali R. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (assist) and pilot brief intervention: a technical report of phase II findings of the who assist project. validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (assist) and pilot brief intervention: a technical report of phase II findings of the who assist Project, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stockings E, Campbell G, Hall WD, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain 2018;159:1932–54. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids: pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:e78–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Campeny E, López-Pelayo H, Nutt D, et al. The blind men and the elephant: systematic review of systematic reviews of cannabis use related health harms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2020;33:1–35. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Memedovich KA, Dowsett LE, Spackman E, et al. The adverse health effects and harms related to marijuana use: an overview review. CMAJ Open 2018;6:E339–46. 10.9778/cmajo.20180023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]