Abstract

Form I ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) of the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle may be divided into two broad phylogenetic groups, referred to as red-like and green-like, based on deduced large subunit amino acid sequences. Unlike the form I enzyme from the closely related organism Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the form I RubisCO from R. capsulatus is a member of the green-like group and closely resembles the enzyme from certain chemoautotrophic proteobacteria and cyanobacteria. As the enzymatic properties of this type of RubisCO have not been well studied in a system that offers facile genetic manipulation, we purified the R. capsulatus form I enzyme and determined its basic kinetic properties. The enzyme exhibited an extremely low substrate specificity factor, which is congruent with its previously determined sequence similarity to form I enzymes from chemoautotrophs and cyanobacteria. The enzymological results reported here are thus strongly supportive of the previously suggested horizontal gene transfer that most likely occurred between a green-like RubisCO-containing bacterium and a predecessor to R. capsulatus. Expression results from hybrid and chimeric enzyme plasmid constructs, made with large and small subunit genes from R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides, also supported the unrelatedness of these two enzymes and were consistent with the recently proposed phylogenetic placement of R. capsulatus form I RubisCO. The R. capsulatus form I enzyme was found to be subject to a time-dependent fallover in activity and possessed a high affinity for CO2, unlike the closely similar cyanobacterial RubisCO, which does not exhibit fallover and possesses an extremely low affinity for CO2. These latter results suggest definite approaches to elucidate the molecular basis for fallover and CO2 affinity.

It is well established that the synthesis of both form I and form II ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) from the nonsulfur purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus is highly dependent on the environmental growth conditions (8, 33). Yet, aspects of the molecular biology of autotrophic carbon dioxide metabolism and RubisCO synthesis in this organism have only recently been stressed (26–28), and there is little information available on the enzymology of RubisCO in this versatile organism. This neglect has largely been due to the fact that the regulation and biochemistry of CO2 assimilation are highly studied in the closely related organism Rhodobacter sphaeroides (6, 16, 31, 36). Early immunological studies, however, indicated that there were substantial and unexpected differences between the form I enzymes of R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides (8), which was later substantiated by DNA hybridization results (34) and additional immunological studies (26). The distinctness of the form I RubisCO of R. capsulatus was recently confirmed during a recent study of the organization and regulation of the CO2 fixation genes of this organism (28). During this investigation, it was noted that deduced amino acid sequences of the large and small subunits of form I RubisCO from R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides were surprisingly different, despite the close phylogenetic relatedness of the two organisms based on other molecular indicators (27). In fact, the sequence results placed the R. capsulatus form I RubisCO among members of what has been termed the green-type RubisCO group (4, 38), which is comprised of α/β/γ chemoautotrophic proteobacterial and cyanobacterial enzymes (27). It is apparent that all genes of the cbbI regulon of R. capsulatus are derived from chemoautotrophic bacteria via some form of horizontal gene transfer (27), whereas genes of the cbbII regulon of this organism closely resemble those from its close relative R. sphaeroides (21, 28). Because of the potential uniqueness of form I RubisCO of R. capsulatus and the availability of recombinant clones (26, 28), it was suggested that detailed study of this enzyme might yield useful insights concerning important molecular properties of a class of RubisCO that has not been highly studied to this point (36). Such studies are important because the determinants responsible for discrimination between either CO2 or O2 as gaseous substrate are largely unknown. The capacity to preferentially use either CO2 or O2 is a property that has great physiological relevance, and yet it can vary significantly depending on the evolutional form of the enzyme (36). Thus, the potential to use the great genetic capacity of R. capsulatus to learn more of the molecular basis for CO2/O2 specificity for an unusual type RubisCO about which little is known was an important consideration in initiating such studies. Finally, despite the relative unrelatedness of R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides form I RubisCO amino acid sequences (58% identity), the large subunit genes from each organism (of similar GC content) are colinear over the majority of the coding region. These sequences would thus be quite amenable for the construction of molecular chimeras or large subunit-small subunit hybrids without disrupting the reading frame. Such studies would be important if kinetic and other properties of the two form I enzymes, especially the CO2/O2 substrate specificity, proved to be different. For these reasons, an investigation of the molecular properties and enzymology of form I RubisCO from R. capsulatus was initiated. Because the enzymological properties of this enzyme were found to be unique, preliminary efforts were also begun to produce hybrid large subunit-small subunit R. capsulatus-R. sphaeroides form I enzymes and molecular chimeras, with the eventual goal of pinpointing molecular determinants responsible for key properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of R. capsulatus and E. coli strains.

R. capsulatus wild-type strain SB1003 and form II RubisCO-deficient mutant strain SBII− (28) were grown photoautotrophically in Ormerod’s minimal medium (25) supplemented with kanamycin (5 μg/ml) as previously described (26). Cells were grown to late log phase (optical density at 600 nm of >1.0) in 0.5-liter batch cultures, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with TEDM (25 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]).

All plasmid propagation and protein expression studies were performed in Escherichia coli JM109 (39). E. coli(pKF1BP), conferring lac promoter-controlled expression of the R. capsulatus form I RubisCO (26), was grown in 0.5-liter Luria-Bertani medium batch cultures supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg/ml). Expression of recombinant RubisCO was induced at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cells were harvested after a 20-h induction period by centrifugation and washed as stated above.

Enzyme purification.

Crude lysates were prepared from washed cell pellets resuspended (1 ml/g [wet weight]) in TEDM adjusted to 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (added just before cell breakage). Cell suspensions were passed through a French pressure cell (SLM Instruments, Inc., Urbana, Ill.) at 16,000 lb/in2 three times, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g to yield a clear cell lysate. Contaminating chromosomal DNA in the clear cell lysate was hydrolyzed by incubating the extract with DNase I (100 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature. All subsequent purification steps were carried out at 4°C unless otherwise indicated. A soluble protein extract was then obtained after centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h; the supernatant was retained and RubisCO was partially purified from this fraction by Green A (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.) dye affinity chromatography using a 2.5- by 4-cm column equilibrated in TEMMB (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaHCO3). The Green A column was washed with equilibration buffer until the A280 of the eluent returned to baseline (∼250 ml); RubisCO was then eluted with a 300-ml linear salt gradient (0 to 1 M KCl) in TEMMB. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated in an Amicon Centriplus 30 concentrator. RubisCO was purified to homogeneity by loading the concentrated Green A peak onto a Pharmacia Mono Q HR 5/5 column equilibrated with 10 mM KCl in TEM (TEDM minus DTT) and subjected to a 5-ml 10 to 500 mM KCl gradient. RubisCO-containing fractions were desalted using a Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) DG10 column equilibrated with 20% glycerol in TEM (at room temperature), quickly frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C.

Purity of enzyme preparations was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 15% resolving gels (20). Western immunoblots were prepared by transferring SDS-PAGE-resolved proteins onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), using a Bio-Rad Trans-Blot SD semidry electrophoretic transfer cell with either the transfer buffer of Towbin (37) (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol [pH 8.3]) or CAPS [3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid] transfer buffer (10 mM CAPS, 10% methanol [pH 11.0]) for N-terminal sequencing. Blots were blocked and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (0.8% NaCl, 0.02% KCl, 0.115% NaH2PO4 · 7H2, 0.02% KH2PO4)–0.05% Tween 20. Primary antibodies directed toward R. sphaeroides and Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 RubisCO and commercially prepared (Bio-Rad) secondary antibody were all used at 1:3,000 dilutions in PBS phosphate-buffered saline–Tween 20. After exposure to primary and secondary antibodies, blots were briefly equilibrated in 0.1 M Tris-acetate (pH 9.5) before incubation in Attophos (2 min). Signal and documentation of chemifluorescent Western blots were achieved with a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, Calif.) model 864 Storm PhosphorImager. The N-terminal sequence of CbbL was determined with an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.) 475A protein sequencer at The Ohio State Biopolymer facility.

RubisCO was assayed as previously described (7) and according to conditions specified in the figure legends and tables.

Subcloning RubisCO large and small subunit genes.

To simplify future R. capsulatus-R. sphaeroides RubisCO chimera constructions involving EcoRI, all genes were subcloned into a derivative of the pK19 expression vector (30), pK19ΔE1, which lacks an EcoRI site (this study). The cbbS gene of R. sphaeroides (cbbSs) was subcloned as an NruI fragment from pRSF1A, which contains both the large and small subunit genes from R. sphaeroides, into the SmaI site of pK19ΔE1, generating plasmid pRsS-17 (Fig. 1). Proper orientation of the insert with respect to the lac promoter was confirmed by DNA sequencing with the universal forward primer. The R. sphaeroides RubisCO large subunit gene (cbbLs) was PCR amplified by using pRSF1A as a template and custom forward (5′-GGAAGCTTA TGCTTCGAAGATCACCG-3′) and reverse (5′-GGTCTAGAAGCAGCCTTGGGTGA TGC-3′) primers (Operon Technologies, Inc., Alameda, Calif.) that introduced unique 5′ HindIII and 3′ XbaI sites (underlined), respectively. Optimal synthesis of the desired 1.6-kb product was obtained under the following reaction conditions: 1× U.S. Biochemical (Cleveland, Ohio) Taq polymerase buffer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.7 pmol of template (5.22 kb), 0.4 pmol of primers, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 5 U of Taq polymerase (U.S. Biochemical). The PCR program was 3 min at 95°C for the denaturation step; 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 3 min at 72°C; and 7 min at 72°C for the extension step. The resultant 1.6-kb PCR product was subcloned into pUC19 (39) as an HindIII/XbaI fragment, generating plasmid pRsL-1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of hybrid and wild-type RubisCO holoenzyme expression plasmids. The plasmids were named such that the origin of each subunit gene is indicated by the subscripted first letter of the species from which it originated. The bold arrow indicates the location of the lac promoter with respect to the cbb genes, which are all in the proper transcriptional orientation for controlled expression with this promoter. Open and shaded rectangles represent coding regions originating from R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus, respectively. Abbreviations for restriction sites: H, HindIII; X, XbaI; B, BamHI; and K, KpnI.

The form I RubisCO genes of R. capsulatus (cbbLc and cbbSc) were also amplified individually (using PCR) in order to incorporate unique restriction sites for directional cloning, using primers pcbbLc forward (5′-AAGCTTAAGTCCCGCAAGGCC-3′) and reverse (5′-TCTAGATGTCCTTTCGGGCCG-3′) and pcbbSc forward (5′-GGGGATCCTGCAGCACCGCTGAG-3′) and reverse (5′-GGGGTACCGATGGGGAAAGGGGC-3′), introducing BamHI and KpnI sites, (underlined), respectively. The PCRs for these two genes were optimized for Mg2+ concentration (cbbLc, 1.0 mM; cbbSc, 1.5 mM), using otherwise identical reaction conditions as specified above. PCR product size and direct restriction endonuclease digest banding patterns were consistent with expectations for the desired products. The cbbSc PCR product was purified with a Wizard PCR Prep kit (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) and subcloned with a pCR-Script Amp SK(+) cloning kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Briefly, the blunt-ended PCR fragment was ligated into pCR-Script Amp SK(+), generating pRcS-12. The cbbSc gene was then subcloned as a BamHI/KpnI (sites introduced by PCR) fragment into pK19ΔE1, forming pRcS-4 (Fig. 1). R. capsulatus cbbL was never successfully subcloned after numerous attempts using all of the methods described above.

All PCR primers and subcloning steps described here were designed such that none of the constructs resulted in translational fusions with the lacZ α peptide.

Construction of wild-type, hybrid, and chimera RubisCO expression plasmids.

The restriction site incorporation and cloning steps described above facilitated the simple construction of wild-type (used as positive controls in expression experiments) and hybrid holoenzyme expression plasmids (diagrammatically represented in Fig. 1). To reconstruct an R. sphaeroides cbbL-cbbS expression plasmid (pLsSs), the large subunit gene (cbbL) was directionally subcloned as a HindIII/XbaI fragment from pRsL-1 into pRsS-17 (Fig. 1). Similarly, to express a hybrid between R. sphaeroides large and R. capsulatus small subunits, cbbLs was subcloned upstream of R. capsulatus cbbS (cbbSc) in pRcS-4, producing plasmid pLsSc (Fig. 1). Restriction digests and DNA sequencing of the 5′ and 3′ ends of both plasmid inserts (pLsSs and pLsSc) with universal and reverse primers confirmed that the desired clones were made (data not shown). In addition, a large subunit chimera construct was made between R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus, using a colinear XhoI restriction site in both genes (Fig. 1). Plasmid pQ−, containing the R. capsulatus cbbL and cbbS genes, was digested with HindIII/XhoI and ligated to the ∼1.0-kb HindIII/XhoI fragment (result of a partial digest with XhoI) of pRsL-1 (containing the R. sphaeroides cbbL gene), producing plasmid ps/cL-Xho1, which contains a chimeric cbbL gene and a wild-type R. capsulatus cbbS gene (Fig. 1). Restriction digests and DNA sequencing of the insert’s 5′ and 3′ ends confirmed that the desired clone was obtained (data not shown). In addition, an approximately 650 bp EcoRI fragment of ps/cL-Xho1 (which would not exist in the parent plasmid, pQ−) that encompasses the splice site of the chimeric cbbLs/c was subcloned and sequenced to confirm that the desired chimera was constructed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RubisCO gene expression and enzyme purification.

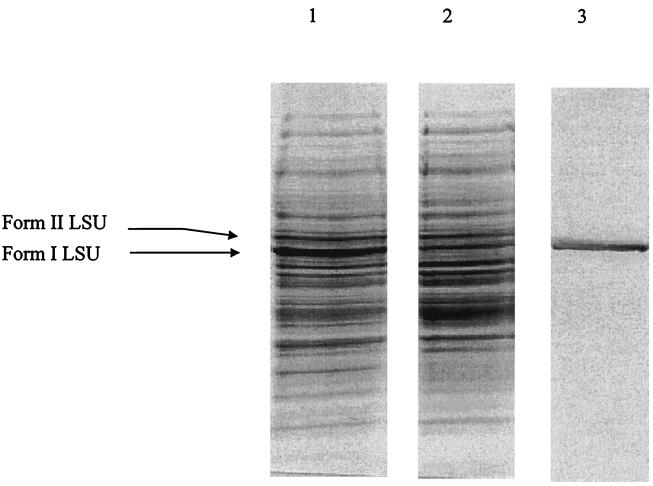

The highest levels of form I RubisCO (∼15% of soluble protein) were obtained from R. capsulatus SBII−, a strain containing an inactivated form II (cbbM) RubisCO gene. This was particularly evident when strain SBII− was grown under photolithoautotrophic conditions to late log phase (data not shown). Since previous studies (28) had indicated that the absence of form II RubisCO leads to a compensatory increase in form I RubisCO synthesis, these results were not surprising. However, it was further observed that 90 to 95% of the RubisCO activity was found in the particulate fraction when cell extracts were subjected to centrifugation at 100,000 × g. This phenomenon was observed when the form I RubisCO was prepared both from R. capsulatus (SB1003 and SBII−) and from E. coli FIPB; thus, the potential formation of carboxysomes in R. capsulatus to account for these results was ruled unlikely. This is in agreement with Southern hybridization data that showed no evidence for a ccmK homologue (a gene product associated with carboxysome structures) when R. capsulatus chromosomal DNA was probed at very low stringency (25a). Western analysis (results not shown) and staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing extracts from photolithoautotrophically grown R. capsulatus SB1003 (a growth condition where both forms of RubisCO are expressed), before and after centrifugation at 100,000 × g, established that the sedimentation phenomenon was specific for the form I enzyme. This is indicated by a decrease in the relative amount of form I protein in the 100,000 × g fraction (Fig. 2). Further experimentation demonstrated that this enzyme had an unusually high affinity for DNA, causing it to cosediment with chromosomal DNA during high-speed centrifugation. The majority of the enzyme activity in cell extracts could be recovered in the 100,000 × g supernatant if the extract was pretreated with DNase I to hydrolyze contaminating chromosomal DNA. Other pretreatments, such as incubation in the presence of 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 M NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA, did not prevent sedimentation (data not shown). Application of the SBII− soluble protein extract to a Green A dye affinity column, washing with TEMMB (pH 7.2), and elution with a KCl gradient (Table 1) resulted in a 1.6-fold purification. Mono Q anion-exchange chromatography of the Green A peak material yielded an enzyme preparation that was judged greater than 95% pure by SDS-PAGE (results not shown) and exhibited a specific activity of >3.0 U/mg under optimal assay conditions. N-terminal sequencing, after elution of SDS-PAGE-purified large subunits from gels, corresponded well with the deduced amino acid sequence (27) except for a missing N-terminal methionine residue as seen with other sequenced RubisCO large subunits (19). The purified enzyme was desalted, adjusted to 20% glycerol, quickly frozen in liquid N2, and stored without loss of activity at −70°C for months.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of R. capsulatus SB1003 cell extracts and purified form I RubisCO. Proteins were electrophoresed in a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide resolving minigel; 15 μg of cell extract (lanes 1 and 2) and 1 μg of purified holoenzyme (lane 3) were loaded. Small subunits were electrophoresed off this gel to enhance the resolution between form I and form II large subunits (LSU; bands indicated on the left). Lanes 1 and 2 were loaded with 10,000 × g and 100,000 × g supernatant fractions, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Purification of R. capsulatus Form I RubisCO

| Purification step | RubisCO activity (U) | Protein (mg) | % Yield | Sp acta (μmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 15.6 | 30.0 | 0.5 | |

| Green A | 6.0 | 7.1 | 38 | 0.8 |

| Mono Q | 6.7 | 3.2 | 22 | 3.4b |

Values obtained in 5-min assays at 30°C.

Assays performed in the presence of 5 mM DTT and 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml to obtain maximum activity.

Enzymatic characterization of R. capsulatus form I RubisCO.

The activity of purified R. capsulatus form I RubisCO was particularly sensitive to low protein concentrations (<5 μg/ml), as only about 30% of its optimal activity was obtained. Activity increased by 50% with the addition of DTT (5 mM) and increased by 40 to 370% (depending on the amount of RubisCO assayed) when both DTT and bovine serum albumin (100 μg/ml) were included in reaction mixtures (results not shown). When the enzyme was carbamylated to convert the enzyme to an active ternary complex (24), i.e., by preincubation in the presence of Mg2+ and CO2, the highest activities were obtained at 30°C in the presence of 5 mM DTT (activity increased by 152% over the untreated enzyme). The presence of DTT improved activity at all temperatures but was maximally effective at 30°C. Preincubation temperatures of 37 and 48°C progressively inhibited enzyme activity (activity decreased by 92% in the absence of DTT).

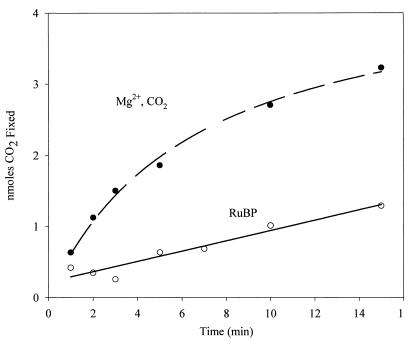

With the exception of the Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 enzyme and other cyanobacterial enzymes, all other form I RubisCO enzymes characterized to date are inhibited by the presence of RuBP in preincubations with uncarbamylated (unactivated) enzyme (36). This phenomenon has been clearly shown to be attributed to the ability of RuBP to lock the unactivated enzyme to a state that prevents the necessary carbamylation (activation) of the enzyme when CO2 and Mg2+ are subsequently added (29). Cyanobacterial form I RubisCO and Thiobacillus denitrificans form I RubisCO, which are both closely related at the primary sequence level to the R. capsulatus form I enzyme, clearly exhibit linear and noninhibited reaction time courses when RuBP is added to preincubation mixtures (11, 23). The rate of the R. capsulatus form I RubisCO, however, was substantially inhibited by the presence of substrate RuBP in similar preincubation experiments (Fig. 3). Moreover, the clear decrease in the reaction rate of CO2/Mg2+-preincubated R. capsulatus enzyme after about 2 to 3 min is diagnostic of fallover due to the formation of high-affinity protonated RuBP intermediates during catalysis that inhibit the reaction. Fallover is not observed with the cyanobacterial or T. denitrificans enzymes (11, 23). Thus, despite the primary sequence similarities of the cyanobacterial/thiobacillus and R. capsulatus form I RubisCOs, these results represent clear differences between these enzymes.

FIG. 3.

Preincubation and effect of RuBP on the activation of R. capsulatus form I RubisCO. Enzyme was desalted with a Bio-Rad DG10 column and preincubated either in the presence of standard concentrations of magnesium and bicarbonate or in the presence of RuBP for 5 min before initiation of the reaction with the components needed to complete the assay mixture (23). At the indicated times, aliquots of the assay mixture were acidified and then counted by liquid scintillation spectroscopy; 0.5 μg of purified enzyme was used in the reaction.

Further kinetic characterization of the R. capsulatus form I RubisCO indicated that the KRuBP was 8 μM, using standard Michaelis-Menten procedures (Table 2). Examination of other kinetic properties, however, yielded unexpected results. The CO2/O2 substrate specificity factor (τ or Ω) of the R. capsulatus form I enzyme was found to be 26, as determined by the dual-label assay method of Jordan and Ogren (15). This value is much lower than that obtained for the unrelated form I enzyme of R. sphaeroides and somewhat lower than that of the sequence-similar Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 enzyme (Table 2) and form I enzyme of T. denitrificans (11). A limited number of L8S8 (form I) enzymes have been studied with specificity factors below 30. Among all sequences in the database, the deduced amino acid sequence of Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila (40) exhibited the highest degree of similarity (87% identity) to the R. capsulatus catalytic subunit. Not surprisingly, the Ω values recently reported for two Hydrogenovibrio marinus form I enzymes, which are also highly similar (78 and 76% identity, respectively), were also rather low, at 27 and 33, respectively (13).

TABLE 2.

RubisCO kinetic properties

It is well established that several cyanobacteria (including Synechococcus) and some aerobic chemoautotrophic bacteria form structures known as carboxysomes, which are cellular inclusions containing aggregates composed largely of paracrystalline RubisCO. No such structures have been described for R. capsulatus. The proposed function of the carboxysomes in organisms that bear them is to facilitate the transport and concentration of carbon dioxide to RubisCO active sites (17). Interestingly, the KCO2 for the R. capsulatus form I enzyme was determined to be 29 μM (Table 1). Despite the fact that the cyanobacterial and R. capsulatus form I RubisCOs are so homologous (72 and 37% identity for large and small subunits, respectively), the cyanobacterial enzyme has a much lower affinity for this gaseous substrate (KCO2 = 174 μM [Table 2]), as does the enzyme of T. denitrificans (11). The low KCO2 of the R. capsulatus enzyme may explain why an organism like R. capsulatus, containing an inactivated form II RubisCO gene (28), is able to grow so efficiently under chemoautotrophic conditions in the presence of oxygen even though it possesses a low CO2/O2 substrate specificity form I RubisCO and has no apparent carbon concentrating mechanism. It would appear that selection pressures favored the evolution of this type of enzyme. Most importantly, the availability of the R. capsulatus form I enzyme should stimulate future DNA shuffling experiments (3) with sequence-related form I enzymes that possess different properties, such as cyanobacterial (Synechococcus) RubisCO, so that the molecular basis for varied CO2 affinity and fallover might be ascertained.

Expression of wild-type, hybrid, and chimeric RubisCOs in E. coli.

Initial steps were made to begin uncovering relevant structural differences between the form I RubisCOs from R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides. Although the primary sequences are somewhat different (27), large subunits and small subunits still show 58 and 34% identity at the amino acid level. Few hybrid and chimeric RubisCO mutants have been expressed in vivo to study structure-function relationships. However, vastly dissimilar recombinant small subunits from a eukaryotic nongreen alga could assemble with cyanobacterial large subunits to form a holoenzyme with a substrate specificity factor enhanced by 60% (32). Despite a 20-fold loss in carboxylase activity, this hybrid provided insights concerning individual subunit involvement in regulation by sugar phosphate metabolites (32). Not all attempts to make hybrid RubisCOs have been so fruitful. Lee et al. (22) described a hybrid consisting of cyanobacterial large subunits and small subunits from the chemoautrophic bacterium Ralstonia eutropha (Alcaligenes eutrophus) which exhibited similar kinetic properties (except a 85% reduction in kcat) to the natural cyanobacterial holoenzyme. Catalytically active hybrids have also been successfully made in vitro by combining partially purified large and small subunits (1, 2, 12, 14), but in most cases Michaelis constants and other enzymological properties were not investigated. In any case, the previous results cited above suggested that in vivo hybrid and chimera construction experiments with the requisite genes of R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides, which are more closely related than the above algal-cyanobacterial hybrid components, might be quite interesting. In addition, the sequences from R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides do present some advantages for such constructions, including the ability to make facile chimeras without disrupting the reading frame. Identifying regions of the RubisCO molecule that are germane to the various properties discussed above may help explain the disparity in specificity values and other kinetic parameters. Eventually, it is hoped that these types of studies will suggest the participation of new residues or domains that have so far gone unnoticed in studies using current X-ray structural models. Considering the differences in amino acid sequence (27) and kinetic properties (Table 2), there was the potential to observe dramatic effects upon construction of hybrids and chimeras with the genes encoding large and small subunits of the R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides enzymes.

Several constructions were attempted. However, a report indicated that the cbbQ product, located downstream from cbbL-cbbS, in P. hydrogenothermophila, is required for maximum activity and folding of this enzyme (10, 13). Previous work had not established whether recombinant form I R. capsulatus RubisCO activity and folding in E. coli required coexpression of cbbQ, a gene also present downstream from cbbL-cbbS of R. capsulatus (27). Since the previously used RubisCO expression vector (pKFIBP) contained the cbbQ gene (26), we constructed an expression plasmid that lacked cbbQ downstream of cbbL-cbbS (Fig. 1). To determine the necessity of cbbQ for stable production of recombinant R. capsulatus RubisCO, extracts of induced cells, harboring plasmids pLSQ-21 (containing the same cbbL-cbbS-cbbQ insert as pKFIBP) (26) or pQ− (encoding only cbbL-cbbS) (Fig. 1), had virtually identical levels of RubisCO activity. Specific activities of 18 and 17 mU/mg were obtained for E. coli(pLSQ-21) and E. coli(pQ−), respectively. Thus, these results indicated that CbbQ was neither required, nor did it enhance RubisCO activity (or stability) for the recombinant R. capsulatus form I enzyme.

Sequence differences and other more subtle structural idiosyncrasies obviously account for variations in the kinetic properties for the respective R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides holoenzymes. Therefore, hybrid and chimeric enzyme expression vectors were constructed by using the R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus large (cbbL) and small (cbbS) subunit genes (Fig. 1). Several unsuccessful attempts were made to induce the expression of active LsSc hybrid under conditions proven to induce the two parent holoenzymes in cells with plasmids containing the original cbbL-cbbS encoding chromosomal inserts (Table 3). To ensure that the cloned genes (cbbLs and cbbSc) were in fact functional, two measures were taken. First, the pLsSs expression plasmid was reconstructed by using the individually cloned genes from pRsL-1 and pRsS-17 (Fig. 1). Extracts from cells containing the resultant plasmid (pLsSs) efficiently expressed RubisCO under identical induction conditions (Table 3). SDS-PAGE analysis of these extracts indicated that cbbLS was highly overexpressed, and the recombinant proteins comigrated with purified R. sphaeroides large and small subunits (results not shown). Second, cell extracts and the urea-solubilized inclusion body fraction from LsSc hybrid-containing cells were used for in vitro reconstitution assays with E. coli extracts containing recombinant cyanobacterial large subunits; purified cyanobacterial small subunits were used as a positive control for small subunit reconstitution activity (12). Reconstitution-competent R. capsulatus small subunits were found in the inclusion body fraction; however, R. sphaeroides large subunits could not be detected by this approach in the LsSc cell extract using purified cyanobacterial small subunits (Table 3). Taken together, these data suggest the following. (i) The genes used to make the LsSc hybrid are functional. When these genes were expressed together to produce their cognate gene products, active holoenzyme was assembled. (ii) The R. sphaeroides large and R. capsulatus small subunits were incapable of forming functional hexadecameric hybrid enzymes, since small subunits were sequestered in the inclusion body fraction instead of being incorporated into the holoenzyme. The same phenomenon was observed when a variety of RubisCO small subunit genes were expressed in E. coli in the absence of coexpressed large subunits (12, 35) and when conserved small subunit residues were mutated in the cyanobacterial enzyme from Anabaena strain 7120 (5).

TABLE 3.

Activity of R. sphaeroides-R. capsulatus hybrid and chimeric recombinant RubisCO in extracts of E. coli

| E. coli plasmida | Source of RubisCO (genes or protein) | Activityb (μmol/min) |

|---|---|---|

| pLsSs | R. sphaeroides cbbL-cbbS | 20.4 |

| pLsSc | R. sphaeroides cbbL-R. capsulatus cbbS | 0.00 |

| pLsSc IBFc | R. sphaeroides cbbL-R. capsulatus cbbS | 0.00 |

| pLsSc IBF + pBGL520d | R. sphaeroides cbbL-R. capsulatus cbbS + Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 rbcL | 1.20 |

| pLsSc + cyanobacterial small subunitse | R. sphaeroides cbbL-R. capsulatus cbbS + purified Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 6301 RbcS | 0.00 |

| ps/cL-XhoI IBF | Chimeric R. sphaeroides-R. capsulatus cbbL/R. capsulatus cbbS | 0.00 |

| ps/cL-XhoI IBF + pBGL520d | Chimeric R. sphaeroides-R. capsulatus cbbL/R. capsulatus cbbS + Synechococcus rbcL | 1.80 |

| ps/cL-XhoI + purified cyanobacterial small subunits | Chimeric R. sphaeroides-R. capsulatus cbbL/R. capsulatus cbbS + purified Synechococcus RbcS | 0.00 |

| pBGL520 | Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 rbcL | 0.10 |

| Purified cyanobacterial small subunits | Purified Synechococcus strain 6301 RbcS | 0.00 |

| pBGL520 + purified cyanobacterial small subunits | Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 rbcL and purified RbcS | 1.30 |

Extracts were obtained from E. coli JM109 containing the indicated plasmids (Fig. 1).

Represents either total RubisCO or reconstitution activity obtained from 1 liter of cells. Reconstitution assays were performed with saturating concentrations of cyanobacterial large and small subunits where indicated.

IBF, 4 M urea-solubilized inclusion body fraction.

pBGL520 represents cell extract from E. coli cells expressing Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 large subunits only.

Purified from extracts of E. coli(pBLG535) expressing Synechococcus strain PCC 6301 small subunits only (12).

Similar results were obtained from cells synthesizing the large subunit chimera (ps/cL-Xho1) with R. capsulatus small subunits (Table 3). This large subunit chimera consists of 62% R. sphaeroides sequence from the N terminus, with the remainder derived from R. capsulatus cbbL (Fig. 1). Crystallography data for spinach RubisCO shows that virtually all large subunit residues present at large/small subunit interfaces in the holoenzyme are contributed from the C-terminal α/β barrel domain (i.e., the last ∼320 amino acids, which correspond to 67% of the C terminus) (18). In addition, all large subunit residues involved in hydrogen bonds between large and small subunits reside in the C-terminal domain (18). Thus, it was thought that the chances of this chimera producing a productive holoenzyme were high. Evidently replacing or substituting 38% percent of the C terminus with R. capsulatus sequence, however, was not enough to resurrect an active, stable holoenzyme (Table 3).

The 58% sequence identity (465-amino-acid overlap) between R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides form I large subunits suggests that these proteins may have similar tertiary structures. Indeed, form II (R. rubrum) and form I enzymes (that share 31% identity) have very similar three-dimensional structures (9). Nonetheless, the importance of robust dimer formation between two chimeric large subunits cannot be ignored. As Knight et al. (18) point out, the immense surface area involved in N- and C-terminal contacts between large subunit dimer pairs in the spinach enzyme are extremely important to overall holoenzyme stability.

It is also feasible that observed subunit incompatibility is the result of large differences (34% amino acid sequence identity) between R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus small subunit sequences (27). The N-terminal 14-amino-acid insertion and C-terminal deletion in the R. capsulatus small subunit (relative to the R. sphaeroides CbbS sequence) is likely to effect holoenzyme assembly. Of the small subunit residues present at large/small subunit interfaces in the spinach holoenzyme, over 50% came from the first 30 amino acids (of 123 residues) (18).

From these data it is obvious that the subunits of these two enzymes are too evolutionarily divergent to coalesce into an active, stable, and properly folded hexadecamic enzyme, using the construction strategies employed here. Despite previous success in producing a useful Synechococcus large subunit-diatom small subunit hybrid that established subunit contributions to various enzymatic properties (32), the present results are similar to those of previous in vitro experiments (14) which reported unsuccessful reconstitution by isolated Chromatium large subunits and cyanobacterial small subunits. This group and others, however, were able to successfully assemble functional heterologous enzymes between more closely related subunits from a variety of organisms including higher plant small subunits with cyanobacterial large subunits (1, 2, 12, 22, 32). Perhaps in vivo DNA shuffling (3) and other in vivo and in vitro methods, combined with specific genetic selection, which by definition only results in productive assemblages, will allow for the successful synthesis of chimeras to provide molecules for the identification of important functional domains.

Concluding remarks.

High-yield purification of R. capsulatus form I RubisCO has been described. Enzymological properties determined here firmly establish its green-like nature, and the results corroborate the suggestion that the genes for this enzyme were likely transmitted to an ascendant of R. capsulatus via a horizontal gene transfer event (27). Of particular importance are the low CO2/O2 substrate specificity, the high affinity for CO2, and the inhibition by RuBP. Failure to successfully assemble recombinant hybrid holoenzymes in vivo with subunits from another purple nonsulfur bacterium further indicate the vast differences of the R. capsulatus protein, as does a preliminary attempt to construct a chimera between large subunits of these proteins. Finally, observed similarities in primary structure of the R. capsulatus and cyanobacterial form I enzymes, and the fact that the KCO2 is so different for the two enzymes, suggest that the construction of in vivo chimeras between these two proteins might be a worthwhile endeavor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM 24497 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews T J, Lorimer G H. Catalytic properties of a hybrid between cyanobacterial large subunits and higher plant small subunits of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4632–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews T J, Greenwood D M, Yellowlees D. Catalytically active hybrids formed in vitro between large and small subunits of different procaryotic ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;234:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crameri A, Raillard S-A, Bermudez E, Stemmer W P C. DNA shuffling of a family of genes from diverse species accelerates directed evolution. Nature. 1998;391:288–291. doi: 10.1038/34663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delwiche C F, Palmer J D. Rampant horizontal transfer and duplication of RubisCO genes in eubacteria and plastids. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:873–882. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitchen J H, Knight S, Andersson I, Branden C-I, McIntosh L. Residues in three conserved regions of the small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase are required for quarternary structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5768–5772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson J L. Genetic analysis of CO2 fixation genes. In: Blankenship R E, Badigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 1107–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson J L, Tabita F R. Different molecular forms of d-ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:943–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson J L, Tabita F R. Isolation and preliminary characterization of two forms of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.3.818-823.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartman F C, Harpel M R. Structure, function, regulation and assembly of d-ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:197–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi N R, Arai H, Kodama T, Igarashi Y. The novel genes, cbbQ and cbbO, located downstream from the RubisCO genes of Pseudomonas Hydrogenothermophila affect the conformational states and activity of RubisCO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:565–569. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez J M, Baker S H, Lorbach S C, Shively J M, Tabita F R. Deduced amino acid sequence, functional expression, and unique enzymatic properties of the form I and form II ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from the chemoautotrophic bacterium Thiobacillus denitrificans. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:347–356. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.347-356.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horken K M. Ph.D. dissertation. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igarashi Y, Kodama T. Genes related to carbon dioxide fixation in Hydrogenovibrio marinus and Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila. In: Lidstrom M E, Tabita F R, editors. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Incharoensakdi A, Takabe T, Akazawa T. Heterologous hybridization of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) restores the enzyme activities. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:698–704. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan D B, Ogren W L. A sensitive assay procedure for simultaneous determination of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and oxygenase activities. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:237–245. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi H M, Tabita F R. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14515–14520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan A, Schwarz R, Lieman-Hurwitz J, Reinhold L. Physiological and molecular aspects of the inorganic carbon-concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:851–855. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight S, Andersson I, Branden C-I. Crystallographic analysis of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from spinach at 2.4 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:113–160. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusano T, Takeshima T, Inoue C, Sugawara K. Evidence for two sets of structural genes coding for ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7313–7323. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7313-7323.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larimer F W, Lu T-Y, Bailey D M. Sequence and expression of the form II ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RUBISCO) gene from Rhodobacter capsulatus. FASEB J. 1995;9:A1275. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee B, Read B A, Tabita F R. Catalytic properties of recombinant octameric, hexadecameric, and heterologous cyanobacterial/bacterial ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;291:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L-A, Tabita F R. Maximum activity of recombinant ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase of Anabaena sp. strain CA requires the product of the rbcX gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3793–3796. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3793-3796.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorimer G H, Badger M R, Andrews T J. The activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase by carbon dioxide and magnesium ions. Equilibria, kinetics, a suggested mechanism, and physiological implications. Biochemistry. 1976;15:529–536. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ormerod J G, Omerod K D, Gest H. Light dependent utilization of organic compounds and photoproduction of molecular hydrogen by photosynthetic bacteria; relationships with nitrogen metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;94:449–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Paoli, G. Personal communication.

- 26.Paoli G C, Morgan N S, Tabita F R, Shively J M. Expression of the cbbLcbbS and cbbM genes and distinct organization of the cbb Calvin cycle structural genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:396–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paoli G C, Soyer F, Shively J, Tabita F R. Rhodobacter capsulatus genes encoding form I ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (cbbLS) and neighboring genes were acquired by a horizontal gene transfer. Microbiology. 1998;144:219–227. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paoli G C, Vichivanives P, Tabita F R. Physiological control and regulation of the Rhodobacter capsulatus cbb operons. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4258–4269. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4258-4269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portis A R., Jr Regulation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1992;43:415–437. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pridemore R D. New and versatile cloning vectors with kanamycin-resistance marker. Gene. 1987;56:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian Y, Tabita F R. A global signal transduction system regulates aerobic and anaerobic CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:12–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.12-18.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Read B A, Tabita F R. A hybrid ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase enzyme exhibiting a substantial increase in substrate specificity factor. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5553–5560. doi: 10.1021/bi00139a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shively J M, Davidson E, Marrs B L. Derepression of the synthesis of the intermediate and large forms of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Arch Microbiol. 1984;138:233–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00402127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shively J M, Devore W, Stratford L, Porter L, Medlin L, Stevens S E., Jr Molecular evolution of the large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;37:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smrcka A V, Ramage R T, Bohnert H J, Jensen R G. Purification and characterization of large and small subunits of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase expressed separately in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;286:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabita F R. The biochemistry and metabolic regulation of carabon metabolism and CO2 fixation in purple bacteria. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 885–914. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson G M F, Tabita F R. Microbial ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: a molecule for phylogenetic and enzymological investigation. FEMS Lett. 1997;146:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokoyama K, Hayashi N, Arai H, Chung S, Igarashi Y, Kodama T. Genes encoding RubisCO in Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila are followed by a novel cbbQ gene similar to nirQ of the denitrification gene cluster from Pseudomonas species. Gene. 1995;153:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]