Abstract

Background:

Antibiotics are losing their effectiveness because of the rapid emergence of resistant bacteria. Unnecessary antimicrobial use increases antimicrobial resistance (AMR). There are currently no published data on antibiotic consumption in Pakistan at the community level. This is a concern given high levels of self-purchasing of antibiotics in Pakistan and variable knowledge regarding antibiotics and AMR among physicians and pharmacists.

Objective:

The objective of this repeated prevalence survey was to assess the pattern of antibiotic consumption data among different community pharmacies to provide a baseline for developing future pertinent initiatives.

Methods:

A multicenter repeated prevalence survey conducted among community pharmacies in Lahore, a metropolitan city with a population of approximately 10 million people, from October to December 2017 using the World Health Organization (WHO) methodology for a global program on surveillance of antimicrobial consumption.

Results:

The total number of defined daily doses (DDDs) dispensed per patient ranged from 0.1 to 50.0. In most cases, two DDDs per patient were dispensed from pharmacies. Co-amoxiclav was the most commonly dispensed antibiotic with a total number of DDDs at 1018.15. Co-amoxiclav was followed by ciprofloxacin with a total number of 486.6 DDDs and azithromycin with a total number of 472.66 DDDs. The least consumed antibiotics were cefadroxil, cefotaxime, amikacin, and ofloxacin, with overall consumption highest in December.

Conclusion:

The study indicated high antibiotic usage among community pharmacies in Lahore, Pakistan particularly broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were mostly dispensed inappropriately. The National action plan of Pakistan on AMR should be implemented by policymakers including restrictions on the dispensing of antimicrobials.

Keywords: Antibiotics, community pharmacies, consumption, defined daily doses, prevalence survey

Introduction

Antibiotics, which have revolutionized medicine and saved millions of lives worldwide, are losing their efficacy because of the rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).1,2 Moreover, growing rates of AMR are now increasing morbidity, mortality, and costs.3–7 In 1962, the first case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was identified. Since then, pharmaceutical companies have developed many new potent antibiotics. However, fewer new antibiotics are now being discovered and marketed in recent years, enhanced by considerable commercial opportunities for new medicines for immunological diseases, cancer, and orphan diseases versus new antibiotics.4,8–10 Over time though, the effectiveness of the newer potent antibiotics has reduced due to their inappropriate use along with the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of S. typhi and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.2,11 Despite significant attempts to optimize antibiotic use in the community and hospital settings, AMR rates continue to increase enhanced by excessive and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics in both individuals and the population at large.12,13 Community pharmacies provide major primary health care facilities in most low monthly income countries (LMICs), which is enhanced during the pandemics, that is, COVID-19. 14 Consequently, the surveillance of dispensing behavior among private community pharmacies, who have an important role in delivering primary care especially in LMICs, is essential. Injudicious and high use of antibiotics, especially in ambulatory care where most infections are seen, increases the utilization of broad-spectrum and more expensive antimicrobials enhancing AMR. 15 As a result, there are ongoing antimicrobial stewardship programs globally, regionally, and nationally to improve antibiotic utilization rates with AMR, a worldwide problem.16–22

The discrepancies and differences in the consumption of antibiotics among European countries prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to organize its first meeting on drug Consumption in Oslo in 1969, which led to the development of the WHO European Drug Utilization Research Group (DRUG). 23 However, regular research on antibiotic consumption is now undertaken by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) as well as the WHO Europe group using a range of indicators.24–26 To ascertain antibiotic consumption on an individual level (per person basis), the World Bank studied consumption patterns among six selected countries including China, India, the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and France from 2000 to 2010. The findings showed that antibiotic consumption increased in which cephalosporin increased in consumption by 36% and other broad-spectrum penicillins accounted for a 55% increase in consumption. 27 Other recent estimates suggest that worldwide antibiotic consumption increased by 65% between 2000 and 2015 principally driven by increased utilization in developing countries.28,29 Consequently, activities to reduce inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics especially in the community are urgently needed with antibiotic consumption appreciably increasing over the years.30,31 This is especially important at this time with the WHO concerned about inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics during the current COVID-19 pandemic and has issued guidance to try and reduce such behavior to decrease antibiotic consumption.32,33

The emergence and prevalence of resistant microbes are reported to be highest among Asian countries where they are found to be spreading both in communities and hospitals. 34 One of the reasons for the increasing spread of AMR in this region is the high rate of irrational use of antibiotics.35–38 The first step in developing strategies to reduce inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics in ambulatory care is to determine actual utilization patterns and compare these with suggested quality indicators alongside any ongoing initiatives.39–46 However, determining utilization patterns in LMICs can be challenging with commercial utilization data typically only available in higher income countries. 44 This has resulted in the development of different approaches to measure utilization rates including import data as well as exit surveys.40,47 Currently, in Pakistan, there is a scarcity of data on the pattern of antibiotics dispensed and their consumption at the community pharmacy level hampering the development of future strategies to reduce unnecessary prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics. Within this context, this present repeated prevalence survey aimed to assess the utilization of antibiotics from different community pharmacies in Lahore and to ascertain consumption patterns by measuring the number of dispensed defined daily doses (DDDs) per customer. This is a different approach to WHO and The International Network for Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) criteria that typically just measures the extent of antibiotics being prescribed per patient 48–50 as there are concerns whether such approaches measure the quality of prescribing. 51 In addition, we wanted to assess utilization rates of different classes following the publication of guidance from the WHO and others, including more recently WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) antibiotic listing.40,44,52–54 This builds on our recently published point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in the hospitals of Pakistan. 55 Community pharmacies are very important in Pakistan given high rates of patient co-payments for medicines, appreciable self-purchasing of antibiotics in the community, and concerns with antibiotics being dispensed.56,57

Method

Study design and centers

A multicenter repeated prevalence survey was conducted among community pharmacies in Lahore from October 2017 to December 2017 using the WHO methodology for the global program on surveillance of antimicrobial consumption. 58 This includes measuring consumption rates using the WHO DDD methodology. 59 Lahore is the capital city of Punjab, and it is one of the wealthiest cities of Pakistan with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$277.2 billion and GDP per capita of US$1641 in 2018, with a population of approximately 10 million. We chose Lahore for this study as community pharmacies in Lahore are undergoing radical changes as this city harbors well-established pharmacy chains as well as independent pharmacies. In addition, if there were concerns with inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials in the main provincial capital city, such concerns are likely to be seen throughout Pakistan. Five community pharmacies in Lahore were enrolled for the study from different geographical areas of Lahore.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our study included both oral and parenteral antibacterial agents excluding vaginal, ophthalmic, or other topical antibacterial agents because these dosage forms are mainly associated with AMR.

Variables

Pharmacy name, generic name, brand name, strength, dosage form, route, volume dispensed, pack size, and grams of drug dispensed were recorded.

Data collection and analysis

First, we reviewed the inventory of antibiotics in each selected pharmacy. One-day antibiotic sales data were collected consecutively for 3 months in each pharmacy. The data of antibiotics consumed per day were extracted from the pharmacy management system named Wasila Inventory Management Software® (Abuzar Consultancy, Pvt, Ltd), which is the reliable inventory management software used in Pakistan. Different parameters were checked including the brand name, generic name, dosage form, strength, and quantity of dispensed antibiotics, respectively. Consumption data were obtained from different community pharmacies, measuring the number of packs dispensed per day. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel sheets including the name of all the variables, and statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 24 version. Antibiotic consumption was measured using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC)/DDD system developed by WHO.59,60 The DDD is defined as the average maintenance dose per day for a drug used in adults for its primary indication. DDDs enable comparisons to be made between different hospitals, pharmacies, and even countries.40,45,18,61,62 We were not able to ascertain DIDs (DDDs per 1000 inhabitants per day) as there was no reliable denominator. However, measuring DDDs per patient for the different antibiotics dispensed does permit assessing utilization patterns against suggested quality indicators. A DDD is only assigned for medicines that already have an ATC code. According to the ATC/ DDD methodology, collected data were analyzed, where the number of DDDs of drugs was determined from the number of grams dispensed. The number of DDDs is equal to the total grams used divided by the DDD value in grams. The total grams of the antibacterial used are calculated by summing up the amounts of the active ingredient in different formulations and pack sizes.

Results

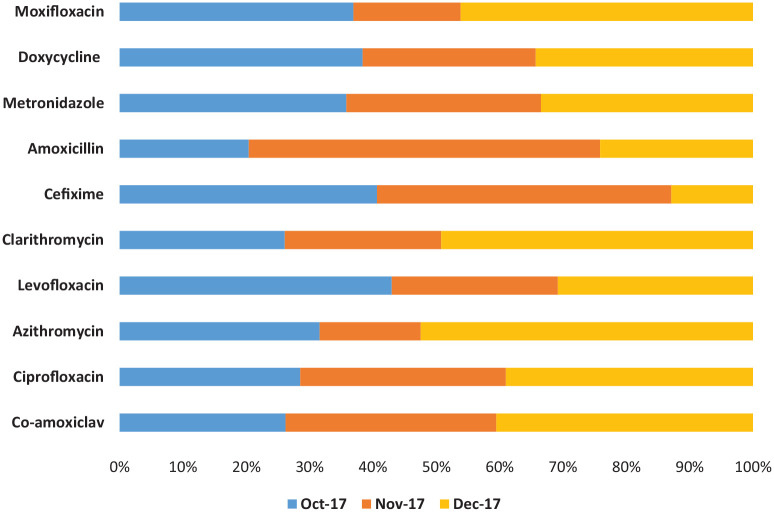

Antibiotics in tablet dosage form were the most commonly dispensed from the selected community pharmacies (Table 1). There was considerable variation in the total number of DDDs dispensed per patient, ranging from 0.1 to 50.0 DDDs. In most of the cases observed in the study, two DDDs were dispensed per patient. Table 2 and Figure 1 describe the consumption patterns of the antibiotics dispensed, which differed significantly during follow-up. Co-amoxiclav (J01CR02) was the most commonly dispensed antibiotic with a total number of DDDs of 1018.15 (24.3%) among the five pharmacies during the data collection period, followed by ciprofloxacin (J01MA02) with a total number of DDDs of 486.6 (11.6%). Azithromycin (J01FA10) was the third most commonly dispensed antibiotic with a total number of DDDs of 472.66, and the highest number of dispensed DDDs of azithromycin was also in December 2017, that is, 247.5 (6%) DDDs. That was followed by levofloxacin (J01MA12) with a total number of DDDs of 344.5 (8.2%), clarithromycin (J01FA09) with a total number of DDDs of 324.52 (7.7%), and cefixime (J01DD08). Cefadroxil, meropenem, cefotaxime, amikacin, and ofloxacin were found to be least dispensed during the period mentioned.

Table 1.

Overall antibiotic consumption.

| Parameters | October 2017 | November 2017 | December 2017 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of DDDs | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.29 ± 3.24 | 2.97 ± 4.14 | 3.62 ± 4.34 | 3.30 ± 3.97 |

| Median (range) | 2.25 (0.1–20.0) | 1.50 (0.1–50.0) | 2.50 (0.1–35.0) | 2.00 (0.1–50.0) |

| Total | 1287.09 | 1245.7 | 1651.61 | 4184.43 |

| Dosage form | ||||

| Tablet, n (%) | 241 (61.7) | 254 (60.5) | 262 (57.4) | 757 (59.8) |

| Capsule, n (%) | 108 (27.6) | 93 (22.2) | 125 (27.4) | 326 (25.9) |

| Injection, n (%) | 22 (5.6) | 33 (7.9) | 36 (7.90 | 91 (7.4) |

| Suspensions, n (%) | 15 (2) | 26 (6.2) | 28 (6.1) | 69 (5.5) |

| Infusion, n (%) | 19 (0.6) | 5 (1.2) | 0 | 24 (2.1) |

| Syrup, n (%) | 3 (0.8) | 8 (1.9) | 5 (1.1) | 16 (1.3) |

| Route | ||||

| Oral | 367 (93.9) | 381 (90.9) | 423 (92.1) | 1168 (92.3) |

| Parenteral | 24 (6.1) | 38 (9.1) | 34 (7.9) | 98 (7.8) |

DDD: defined daily dose.

Table 2.

Number of DDDs dispensed at community pharmacies.

| Antibiotics | October 2017 | November 2017 | December 2017 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode (range) | Total | Mode (range) | Total | Mode (range) | Total | Mode (range) | Total | |

| Co-amoxiclav (J01CR02) | 8.3 (4.9–20.0) | 266.9 | 10.6 (7.3–38.1) | 339.0 | 7.5 (1.4–30.4) | 412.8 | 15.2 (1.4–38.1) | 1018.9 |

| Ciprofloxacin (J01MA02) | 7.0 (2.3–13.0) | 138.8 | 1.0 (0.3–21.0) | 158.0 | 5.5 (2.9–35.0) | 189.9 | 3.0 (0.3–35.0) | 486.6 |

| Azithromycin (J01FA10) | 5.0 (0.8–10.0) | 149.0 | 1.0 (0.8–3.0) | 75.3 | 5.0 (1.6–13.0) | 247.5 | 5.0 (0.8–13.0) | 472.7 |

| Levofloxacin (J01MA12) | 8.0 (3.5–13.0) | 145.0 | 2.0 (2.0–22.0) | 88.5 | 3.0 (0.5–10.0) | 104.0 | 2.0 (0.5–22.0) | 337.5 |

| Clarithromycin (J01FA09) | 2.0 (0.5–2.0) | 84.5 | 3.0 (0.5–5.0) | 80.0 | 3.0 (0.5–15.0) | 159.5 | 3.0 (0.5–15.0) | 324.0 |

| Cefixime (J01DD08) | 10.0 (6.0–20.0) | 118.10 | 10.0 (6.0–12.0) | 135.0 | 4.5 (4.5–10.0) | 37.50 | 14.5 (4.5–20.0) | 290.6 |

| Amoxicillin (J01CA04) | 2.7 (1.7–6.2) | 52.2 | 1.0 (0.5–50.0) | 142.0 | 1.0 (0.3–7.5) | 61.8 | 1.0 (0.3–50.0) | 255.9 |

| Metronidazole (J01XD01) | 2.0 (0.2–4.2) | 66.6 | 1.0 (0.2–4.2) | 57.2 | 2.0 (0.2–7.0) | 62.3 | 1.0 (0.2–7.0) | 186.1 |

| Doxycycline (J01AA02) | 3.0 (3.0–3.0) | 66.0 | 10.0 (2.0–20.0) | 47.0 | 10.0 (1.0–20.0) | 59.0 | 10.0 (1.0–20.0) | 172.0 |

| Moxifloxacin (J01MA14) | 2.0 (1.0–14.0) | 36.0 | 1.0 (1.0–5.0) | 16.5 | 2.0– (1.0–7.0) | 45.0 | 2.0 (1.0–14.0) | 97.5 |

| Cephradine (J01DB09) | 2.3 (0.5–5.3) | 29.8 | 0.3 (0.1–7.0) | 26.9 | 0.3 (0.3–3.8) | 13.00 | 0.3 (0.1–7.0) | 69.6 |

| Erythromycin (J01FA01) | 1.0 (0.5–3.0) | 15.7 | 0.5 (0.5–3.5) | 13.0 | 0.5 (0.5–2.5) | 12.3 | 0.5 (0.5–3.5) | 41.0 |

| Rifaximin (A07AA11) | 9.3 (9.3–14.0) | 23.3 | 9.2 (9.2–9.2) | 9.2 | 3.3 (3.3–3.3) | 6.7 | 3.3 (3.3–14.0) | 39.2 |

| Ceftriaxone (J01DD04) | 0.5 (0.5–1.0) | 9.3 | 0.5 (0.5–1.0) | 11.0 | 0.5 (0.3–2.5) | 17.50 | 0.5 (0.3–2.5) | 37.8 |

| Cefuroxime (J01DC02) | NU | NU | 0.5 (0.5–2.0) | 28.5 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 | 0.5 (0.5–21.0) | 29.5 |

| Cefaclor (J01DC04) | 1.5 (1.5–4.5) | 6.0 | 0.5 (0.5–1.5) | 2.0 | 1.5 (1.5–3.0) | 6.00 | 1.5 (0.5–4.5) | 14.0 |

| Ampicillin (J01CA01) | NU | NU | NU | NU | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 10.0 | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 10.0 |

| Clindamycin (J01FF01) | 0.5 (0.5–1.6) | 5.0 | 4.0 (4.0–4.0) | 4.0 | 0.25 (0.3–.05) | 0.8 | 0.5 (0.3–4.0) | 9.8 |

| Linezolid (J01XX08) | 1 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 | 2.0 (2.0–5.0) | 7.00 | NU | NU | 1.0 (1.0–5.0) | 8.0 |

| Vancomycin (J01XA01) | 0.5 (0.5–1) | 1.5 | 0.3 (0.3–1.0) | 1.50 | NU | NU | 0.3 (0.3–1.0) | 3.0 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam (J01CR05) | NU | NU | 0.3 (0.3–1.2) | 1.5 | 0.3 (0.3–1.0) | 1.3 | 0.3 (0.3–1.9) | 2.9 |

| Lincomycin (J01FF02) | NU | NU | NU | NU | 0.5 (0.6–1.1) | 2.2 | 0.5 (0.6–1.1) | 2.2 |

| Ofloxacin (J01MA01) | NU | NU | NU | NU | 1.5 (1.5–1.5) | 1.5 | 1.5 (1.5–1.5) | 1.5 |

| Amikacin (J01GB06) | 0.5 (0.1–0.5) | 1.10 | NU | NU | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.3 | 1.0 (0.1–0.5) | 1.4 |

| Cefotaxime (J01DD01) | NU | NU | 0.3 (0.3–0.5) | 1.0 | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 0.31 | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 1.3 |

| Meropenem (J01DH02) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 0.5 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 0.5 | NU | 0.3 (0.3–0.5) | 1.0 | |

| Cefadroxil (J01DB05) | NU | NU | NU | NU | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.00 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 |

DDD: defined daily dose, NU: Not Used.

Figure 1.

Percentage consumption data of top 10 antibiotics.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prevalence survey that presents data on antibiotic consumption among community pharmacies in Lahore, Pakistan. We believe the highest consumption of broad-spectrum antibiotics is due to a belief in better coverage against potential bacteria in the absence of any formal resistance pattern data. However, this remains to be seen. Interestingly, the dispensing of these antibiotics were found to be increased in November and December, which may be due to increased respiratory tract infections despite the vast majority being viral in origin.15,63 Consequently, antibiotics never prove completely beneficial for patients experiencing viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and should be reserved. 15 This excessive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics raises concerns regarding inappropriate use. 64 Ideally, these antibiotics must be used as the second-line agents because these are not recommended as the first-line agent for the management of respiratory tract infections and are part of the WHO AWaRe list. Interestingly, this study reported frequent dispensing of metronidazole, despite less number of total DDDs. This dispensing pattern can be attributed partly since the dosing frequency of metronidazole is high. The common practice seen in this aspect is that patients usually take one or two doses of metronidazole for diarrhea and later discontinue the course once relieved of their symptoms. This is witnessed as a commonly irrational practice in Pakistan, and we will be following this up in future research. 56 Compare the aforementioned with another finding of this study that one or two DDDs of co-amoxiclav are rarely dispensed because co-amoxiclav is typically available in packing size of six tablets. The tablets of co-amoxiclav are sold as a full pack and are seldom dispensed in units that increase DDD.

The National Action Plan of Pakistan for antibiotics recommends and emphasizes the rational use of antibiotics in the country. Despite this, many reserves and watch group antibiotics in the WHO AWaRe list appear to be consumed in Pakistan for simple infections as well as for prophylaxis.55,56, The irrational use of fluoroquinolones is rising in Pakistan not only causing serious side effects but also increasing the risk of AMR, 65 enhanced by high self-purchasing of antibiotics in Pakistan. 63 According to the critically important antimicrobials (CIA) list of the WHO, quinolones are classified as the main priority class of antibiotics and should be used cautiously. The US FDA has indicated that fluoroquinolones should be only used in those patients left with no other treatment options. 66 Contrary to this, fluoroquinolones are repeatedly used for uncomplicated infections such as upper respiratory infections and diarrhea in Pakistan. 55 This has raised concerns regarding the appropriate use of antibiotics through antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs). Evidence has shown that ASPs have contributed to decreasing both unnecessary antibiotic consumption as well as expenditures in the high-income countries; however, recognizing difficulties with undertaking ASPs in LMICs, especially in ambulatory care.31,67–72 Overall, we believe the community pharmacists must be vigilant about the rational use of antibiotics because they are conveniently accessible and they are an integral part of the healthcare system of any country.73–76 Consequently, they should be part of any future AMS programs within countries to improve future antibiotic utilization. 77 The restricted use of antibiotics can be executed by campaigns of general public awareness and through policy-making including regulations banning the sale of antibiotics in the Watch and Reserve list as well as enhancing the education of pharmacists accompanied by appropriate guidelines.78–80 This is seen as preferrable to fining pharmacists for dispensing antimicrobials without a prescription as seen in some countries especially where there are high co-payments and where community pharmacists are the principal healthcare professional available.15,81

The widespread practice of selling antibiotics inappropriately over the counter or without any prescription is one of the major problems at community pharmacies because of poor law enforcement and needs to be addressed.37,63 A lack of a sustainable health care system and failure regarding enforcement of any regulation are some of the reasons for unauthorized over-the-counter sales of antibiotics.15,82 Unnecessary self-medication with antibiotics may go along to reduce the irrational use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, 63 thereby helping to reduce the emergence of AMR. Moreover, incomplete antibiotic prescription, dosing frequency, duration, and other patient-related factors also promote inappropriate use of antibiotics and need to be tackled with future educational programs among both pharmacists and patients.83,84 This includes dispensing parenteral antibiotics among community pharmacists, which should be avoided given their necessity as well as possible complications from needle administration. Such use in ambulatory care is likely driven more by incentives in the system than actual clinical need. 85 Moreover, the study conducted in Jordan reported that 46% of the patients self-medicated antibiotics. 86 Studies conducted in Malta Lithuania revealed the prevalence of self-medication to be 19% and 22%, respectively.87,88 Furthermore, a study in Europe revealed that Greece had one of the highest rates of antibiotic consumption in Europe as outpatients with macrolides and cephalosporins being the most frequently used antibiotics. 89

We are aware that there are several limitations with this study. First, we did not calculate the consumption and expenditures of antibiotics according to patient demographic factors and clinical conditions. Second, we cannot generalize the findings of the data because we conducted this study in only a few pharmacies in one city of Pakistan. Finally, there could be some underestimation of the consumption of some antibiotics because only 1 day of data was collected from each pharmacy. Nonetheless, we believe that this study provides good baseline data for policymakers, and we are planning future studies to address some of the concerns. Our study identified potential indicators for quality improvement. These included reduced dispensing of incomplete course of antibiotics. In addition, reduce the total consumption of commonly dispensed antibiotics including co-amoxiclav, ciprofloxacin, and other broad-spectrum antibiotics where there are concerns under the AWaRe list.

Conclusion

Our study indicated high antibiotic usage at different community pharmacies, particularly for broad-spectrum antibiotics, that is, azithromycin. The National Action Plan of AMR should be implemented by policymakers to address issues of inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics and must ensure the rational use of antibiotics by the public. Moreover, the National Action Plan of AMR has to design a law to minimize the self-purchasing of antibiotics at community pharmacies. Awareness of the irrational use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be increased among physicians, pharmacists, and patients. The unauthorized over-the-counter sale of antibiotics should be avoided in a community pharmacy where possible.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Zikria Saleem: Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – original draft.

Erwin Martinez Faller: Writing – review & editing.

Brian Godman: Methodology; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Muhammad Sajee Ahmed Malik: Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Aqsa Iftikhar: Writing – original draft.

Sonia Iqbal: Methodology.

Aroosa Akbar: Writing – review & editing.

Mahnoor Hashim: Writing – original draft.

Aneeqa Amin: Writing – review & editing.

Sidra Javeed: Writing – review & editing.

Afreenish Amir: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision.

Alia Zafar: Methodology.

Farah Sabih: Methodology.

Furqan Khurshid Hashmi: Resources.

Mohamed Azmi Hassali: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was acquired from the Human Ethics Committee of University College of Pharmacy, University of the Punjab, Lahore (HEC/1000/PUCP/1925AMCC).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Patient consent: The study design is non-experimental and involves neither patient examination nor any intervention advised or made. This study is based on a non-experimental study design; therefore, patient consent is not required for such type of study.

ORCID iD: Zikria Saleem  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3202-6347

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3202-6347

Muhammad Sajeel Ahmed Malik  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7084-7336

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7084-7336

Furqan Khurshid Hashmi  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4921-3739

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4921-3739

References

- 1. Naylor NR, Atun R, Zhu N, et al. Estimating the burden of antimicrobial resistance: a systematic literature review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018; 7(1): 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saleem Z, Hassali MA. Travellers take heed: outbreak of extensively drug resistant (XDR) typhoid fever in Pakistan and a warning from the US CDC. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019; 27: 127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Founou RC, Founou LL, Essack SY. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017; 12(12): e0189621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2014, https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf

- 5. Cassini A, Hogberg LD, Plachouras D, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hofer U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nature Rev Microbiol 2019; 17(1): 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tacconelli E, Pezzani MD. Public health burden of antimicrobial resistance in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen D. Cancer drugs: high price, uncertain value. BMJ 2017; 359: j4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luzzatto L, Hyry HI, Schieppati A, et al. Outrageous prices of orphan drugs: a call for collaboration. Lancet 2018; 392(10149): 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Godman BOW, de Waure C, Mosca I, et al. Links between pharmaceutical R&D models and access to affordable medicines: a study for the ENVI COMMITTEE, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/587321/IPOL_STU(2016)587321_EN.pdf

- 11. Righi E, Peri AM, Harris PN, et al. Global prevalence of carbapenem resistance in neutropenic patients and association with mortality and carbapenem use: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 72(3): 668–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aldeyab MA, Harbarth S, Vernaz N, et al. The impact of antibiotic use on the incidence and resistance pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in primary and secondary healthcare settings. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 74(1): 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ventola CL. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats. P T 2015; 40(4): 277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cadogan CA, Hughes CM. On the frontline against COVID-19: Community pharmacists’ contribution during a public health crisis. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2021; 17: 2032–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Godman B, Haque M, McKimm J, et al. Ongoing strategies to improve the management of upper respiratory tract infections and reduce inappropriate antibiotic use particularly among lower and middle-income countries: findings and implications for the future. Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36(2): 301–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abilova V, Kurdi A, Godman B. Ongoing initiatives in Azerbaijan to improve the use of antibiotics; findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2018; 16(1): 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jinks T, Lee N, Sharland M, et al. A time for action: antimicrobial resistance needs global response. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94(8): 558–558A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. Global report on surveillance, http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/antimicrobial-resistance/news/news/2014/04/new-report-antibiotic-resistance-a-global-health-threat

- 19. World Health Organization. Resource mobilisation for antimicrobial resistance (AMR): Getting AMR into plans and budgets of government and development partners—Ghana country level report, 2018, https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/national-action-plans/Ghana-AMR-integration-report-WHO-June-2018.pdf?ua=1

- 20. Essack SY, Desta AT, Abotsi RE, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region: current status and roadmap for action. J Public Health 2017; 39(1): 8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tiroyakgosi C, Matome M, Summers E, et al. Ongoing initiatives to improve the use of antibiotics in Botswana: University of Botswana symposium meeting report. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2018; 16(5): 381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Hashmi FK. Pakistan's national action plan for antimicrobial resistance: translating ideas into reality. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18(10): 1066–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bergman U. The history of the drug utilization research group in Europe. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15(2): 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. ECDC. Quality indicators for antibiotic consumption in the community in Europe, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/database/quality-indicators

- 25. ECDC. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption network (ESAC-Net), 2020, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/about-us/partnerships-and-networks/disease-and-laboratory-networks/esac-net

- 26. Robertson J, Iwamoto K, Hoxha I, et al. Antimicrobial medicines consumption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia–an updated cross-national study and assessment of quantitative metrics for policy action. Frontier Pharmacol 2019; 9: 1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Antonanzas F, Goossens H. The economics of antibiotic resistance: a claim for personalised treatments. Eur J Health Econ 2019; 20(4): 483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(15): E3463–E3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016; 387(10014): 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, et al. Global antibiotic consumption2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14(8): 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization. Record number of countries contribute data revealing disturbing rates of antimicrobial resistance, https://www.who.int/news/item/01-06-2020-record-number-of-countries-contribute-data-revealing-disturbing-rates-of-antimicrobial-resistance

- 33. World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19, 2020, https://www.who.int/teams/health-care-readiness-clinical-unit/covid-19 [PubMed]

- 34. Singh PK. One health approach to tackle antimicrobial resistance in South East Asia. BMJ 2017; 358: j3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nepal G, Bhatta S. Self-medication with antibiotics in WHO Southeast Asian region: a systematic review. Cureus 2018; 10(4): e2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nga DTT, Chuc NTK, Hoa NP, et al. Antibiotic sales in rural and urban pharmacies in Northern Vietnam: an observational study. BMC Pharm Toxicol 2014; 15: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang J, Xu S, Zhu S, et al. Assessment of non-prescription antibiotic dispensing at community pharmacies in China with simulated clients: a mixed cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19: 1345–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ali M, Abbasi BH, Ahmad N, et al. Over-the-counter medicines in Pakistan: misuse and overuse. Lancet 2020; 395(10218): 116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fürst J, Čižman M, Mrak J, et al. The influence of a sustained multifaceted approach to improve antibiotic prescribing in Slovenia during the past decade: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2015; 13(2): 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Robertson J, Iwamoto K, Hoxha I, et al. Antimicrobial medicines consumption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia—an updated cross-national study and assessment of quantitative metrics for policy action. Front Pharmacol 2019; 9: 1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, et al. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): quality appraisal of antibiotic use in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66(Suppl. 6): vi71–vi77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Le Maréchal M, Tebano G, Monnier AA, et al. Quality indicators assessing antibiotic use in the outpatient setting: a systematic review followed by an international multidisciplinary consensus procedure. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73(suppl_6): vi40–vi49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharland M, Pulcini C, Harbarth S, et al. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use-be AWaRe. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18(1): 18–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hsia Y, Sharland M, Jackson C, et al. Consumption of oral antibiotic formulations for young children according to the WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) antibiotic groups: an analysis of sales data from 70 middle-income and high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bojanic L, Markovic-Pekovic V, Skrbic R, et al. Recent Initiatives in the Republic of Srpska to Enhance Appropriate Use of Antibiotics in Ambulatory Care; Their Influence and Implications. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Asghar S, Atif M, Mushtaq I, et al. Factors associated with inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics among non-pharmacist pharmacy workers. Res Soc Admin Pharm 2020; 16: 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holloway K, Mathai E, Gray A. Surveillance of community antimicrobial use in resource-constrained settings—experience from five pilot projects. Trop Med Int Health 2011; 16(2): 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ofori-Asenso R, Brhlikova P, Pollock AM. Prescribing indicators at primary health care centers within the WHO African region: a systematic analysis (1995-2015). BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Atif M, Sarwar MR, Azeem M, et al. Assessment of WHO/INRUD core drug use indicators in two tertiary care hospitals of Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. J Pharm Policy Pract 2016; 9: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR, et al. WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators and prescribing trends of antibiotics in the Accident and Emergency Department of Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Pakistan. Springerplus 2016; 5(1): 1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Niaz Q, Godman B, Massele A, et al. Validity of World Health Organisation prescribing indicators in Namibia’s primary healthcare: findings and implications. Int J Qual Health Care 2019; 31(5): 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. de Bie S, Kaguelidou F, Verhamme KM, et al. Using prescription patterns in primary care to derive new quality indicators for childhood community antibiotic prescribing. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35(12): 1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coenen S, Ferech M, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, et al. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): quality indicators for outpatient antibiotic use in Europe. Qual Saf Health Care 2007; 16(6): 440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Atif M, Azeem M, Saqib A, et al. Investigation of antimicrobial use at a tertiary care hospital in Southern Punjab, Pakistan using WHO methodology. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017; 6: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Versporten A, et al. A multicenter point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in Punjab, Pakistan: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019; 17: 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Godman B, et al. Sale of WHO AWaRe groups antibiotics without a prescription in Pakistan: a simulated client study. J Pharm Policy Pract 2020; 13: 26–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Hashmi FK, et al. Antimicrobial dispensing practices and determinants of antimicrobial resistance: a qualitative study among community pharmacists in Pakistan. Fam Med Community Health 2019; 7: e000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. World Health Organisation. WHO methodology for a global programme on surveillance of antimicrobial consumption 2017, http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/WHO_AMCsurveillance_1.0.pdf (accessed 31 May 2018)

- 59. World Health Organisation. WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. ATC/ DDD Index, https://www.whocc.no/

- 60. World Health Organisation. WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment, 2017, https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index_and_guidelines/guidelines/

- 61. Malo S, Bjerrum L, Feja C, et al. The quality of outpatient antimicrobial prescribing: a comparison between two areas of northern and southern Europe. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 70(3): 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. ECDC. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network (ESAC-Net), http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/activities/surveillance/ESAC-Net/Pages/index.aspx

- 63. Saleem Z, Saeed H, Ahmad M, et al. Antibiotic self-prescribing trends, experiences and attitudes in upper respiratory tract infection among pharmacy and non-pharmacy students: a study from Lahore. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(2): e0149929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. de Bie S, Kaguelidou F, Verhamme KM, et al. Using prescription patterns in primary care to derive new quality indicators for childhood community antibiotic prescribing. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35(12): 1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bartoloni A, Pallecchi L, Riccobono E, et al. Relentless increase of resistance to fluoroquinolones and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Escherichia coli: 20 years of surveillance in resource-limited settings from Latin America. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19(4): 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McCarthy M. US warns against use of fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated infections. BMJ 2016; 353: i2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gangat MA, Hsu JL. Antibiotic stewardship: a focus on ambulatory care. S D Med 2015; 2015: 44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fay LN, Wolf LM, Brandt KL, et al. Pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship program in an urgent care setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2019; 76(3): 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Suda KJ, Hicks LA, Roberts RM, et al. Antibiotic expenditures by medication, class, and healthcare setting in the United States, 2010–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 66(2): 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee CF, Cowling BJ, Feng S, et al. Impact of antibiotic stewardship programmes in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73(4): 844–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cox JA, Vlieghe E, Mendelson M, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: the same but different. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23(11): 812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Honda H, Ohmagari N, Tokuda Y, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in inpatient settings in the Asia Pacific region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(suppl_2): S119–S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van Eikenhorst L, Salema NE, Anderson C. A systematic review in select countries of the role of the pharmacist in consultations and sales of non-prescription medicines in community pharmacy. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2017; 13(1): 17–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Markovic-Pekovic V, Grubisa N, et al. Initiatives to reduce nonprescription sales and dispensing of antibiotics: findings and implications. J Res Pharm Pract 2017; 6(2): 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. FIP. FIP statement of policy—control of antimicrobial medicines resistance (AMR), http://www.fip.org/www/uploads/database_file.php?id=289&table_id

- 76. World Health Organisation. The role of pharmacist in encouraging prudent use of antibiotics and averting antimicrobial resistance: a review of policy and experience, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/262815/The-role-of-pharmacist-in-encouraging-prudent-use-of-antibiotics-and-averting-antimicrobial-resistance-a-review-of-policy-and-experience-Eng.pdf?ua=1

- 77. Bishop C, Yacoob Z, Knobloch MJ, et al. Community pharmacy interventions to improve antibiotic stewardship and implications for pharmacy education: a narrative overview. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2019; 15(6): 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Markovic-Pekovic V, Grubisa N, Burger J, et al. Initiatives to reduce nonprescription sales and dispensing of antibiotics: findings and implications. J Res Pharm Pract 2017; 6(2): 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. FIP. FIP statement of policy—control of antimicrobial medicines resistance (AMR), https://www.fip.org/www/uploads/database_file.php?id=289&table_id

- 80. Mukokinya MMA, Opanga S, Oluka M, et al. Dispensing of antimicrobials in Kenya: a cross-sectional pilot study and its implications. J Res Pharm Pract 2018; 7(2): 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Alrasheedy AA, Alsalloum MA, Almuqbil FA, et al. The impact of law enforcement on dispensing antibiotics without prescription: a multi-methods study from Saudi Arabia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2020; 18(1): 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bahnassi A. A qualitative analysis of pharmacists' attitudes and practices regarding the sale of antibiotics without prescription in Syria. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2015; 10(2): 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, et al. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge concerning antibiotic use and self-medication: a comparative European study. Pharma-coepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16(11): 1234–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Reynolds L, McKee M. Factors influencing antibiotic prescribing in China: an exploratory analysis. Health Policy 2009; 90(1): 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Soleymani F, Godman B, Yarimanesh P, et al. Prescribing patterns of physicians working in both the direct and indirect treatment sectors in Iran; findings and implications. J Pharmaceutical Health Serv Res 2019; 10(4): 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Al-Bakri AG, Bustanji Y, Yousef A-M. Community consumption of antibacterial drugs within the Jordanian population: sources, patterns and appropriateness. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005; 26(5): 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Muscat M, Monnet DL, Klemmensen T, et al. Patterns of antibiotic use in the community in Denmark. Scand J Infect Dis 2006; 38(8): 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Väänänen MH, Pietilä K, Airaksinen M. Self-medication with antibiotics—does it really happen in Europe. Health Policy 2006; 77(2): 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005; 365(9459): 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]