Abstract

Background

Carriage studies are fundamental to assessing the effects of pneumococcal vaccines. Because a large proportion of oral streptococci carry homologues of pneumococcal genes, non–culture-based detection and serotyping of upper respiratory tract (URT) samples can be problematic. In the current study, we investigated whether culture-free molecular methods could differentiate pneumococci from oral streptococci carried by adults in the URT.

Methods

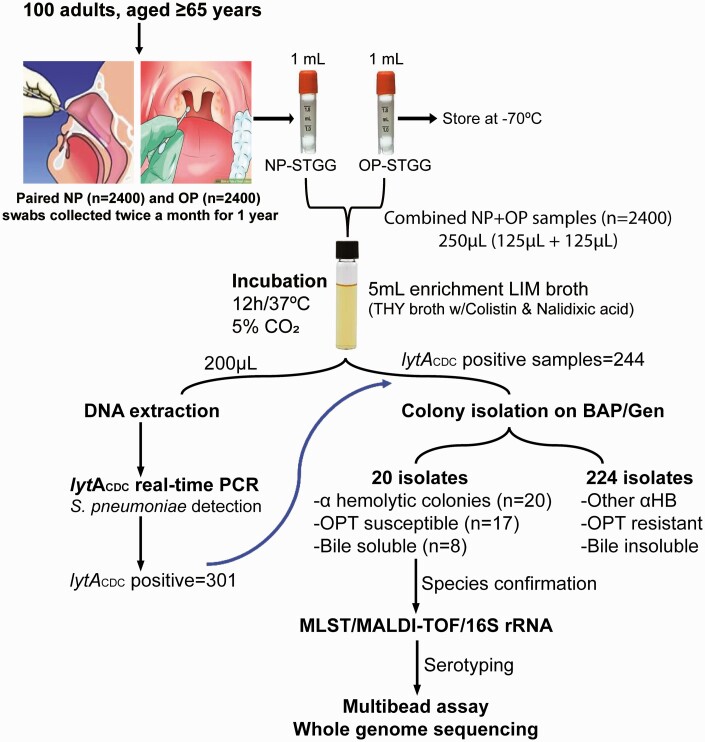

Paired nasopharyngeal (NP) and oropharyngeal (OP) samples were collected from 100 older adults twice a month for 1 year. Extracts from the combined NP + OP samples (n = 2400) were subjected to lytA real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Positive samples were subjected to pure culture isolation, followed by species confirmation using multiple approaches. Multibead assays and whole-genome sequencing were used for serotyping.

Results

In 20 of 301 combined NP + OP extracts with positive lytA PCR results, probable pneumococcus-like colonies grew, based on colony morphology and biochemical tests. Multiple approaches confirmed that 4 isolates were Streptococcus pneumoniae, 3 were Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae, 12 were Streptococcus mitis, and 1 were Streptococcus oralis. Eight nonpneumococcal strains carried pneumococcus-like cps loci (approximate size, 18–25 kb) that showed >70% nucleotide identity with their pneumococcal counterparts. While investigating the antigenic profile, we found that some S. mitis strains (P066 and P107) reacted with both serotype-specific polyclonal (type 39 and FS17b) and monoclonal (Hyp10AG1 and Hyp17FM1) antisera, whereas some strains (P063 and P074) reacted only with polyclonal antisera (type 5 and FS35a).

Conclusion

The extensive capsular overlap suggests that pneumococcal vaccines could reduce carriage of oral streptococci expressing cross-reactive capsules. Furthermore, direct use of culture-free PCR-based methods in URT samples has limited usefulness for carriage studies.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, oral streptococci, capsular overlap, carriage, vaccine

Detection of oral streptococci as pneumococci in the upper respiratory tract can affect the World Health Organization–recommended carriage procedure. With extensive capsular overlap between pneumococci and oral streptococci, pneumococcal vaccines could reduce carriage of oral streptococci expressing cross-reactive capsules.

The human oronasopharyngeal space is the primary reservoir of Streptococcus pneumoniae, where it cohabits with other streptococcal species. Based on 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing, >700 microbial species reside within the oral cavity with >150 species of genus streptococci [1]. Critically, members of the mitis group (20 species) are considered primary colonizers in the mouths of newborn infants, which allow for the development of a complex microbiota [2]. Pneumococcal colonization of the nasopharynx is a prerequisite for transmission and diseases [3]; however, colonization density of the same niche can vary greatly among individuals, perhaps reflecting differences in the physicochemical state. Nonetheless, 40%–95% of infants and 1%–10% of adults are reported to be colonized with pneumococcus asymptomatically at any time [4, 5].

Although the polysaccharide (PS) capsule is one of the prime virulence factors and a hallmark of S. pneumoniae [6], studies have demonstrated that numerous species of mitis group streptococci, including Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus infantis, carry pneumococcus-like capsule biosynthetic (cps) loci and express PS capsules similar to those expressed by their pneumococcal counterparts [7–11]. Nahm et al [12] previously demonstrated that an S. oralis strain, SK95, produces a type 2 capsule PS identical to the capsule produced by S. pneumoniae, D39 strain [12]. Other well-described examples of pneumococcus-like cps operons expressed by closely related streptococci include cps1, cps4, cps5, cps9A, and cps19C loci [8, 9, 11, 13].

Pneumococcal carriage studies are used as an adjunct to IPD surveillance for assessing direct and indirect impact of pneumococcal vaccines. While conjugate vaccines have dramatically reduced the carriage and IPD of vaccine-type pneumococci in high-income countries, their widespread usage has led to a corresponding increase in the carriage of nonvaccine serotypes [14, 15]. Despite the importance of pneumococcal carriage studies, consensus on the design for conducting these studies was lacking. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) Pneumococcal Carriage Working Group issued updated recommendations for pneumococcal carriage studies [16]. The WHO guidelines recommend non–culture-based molecular methods as an option for enhancing pneumococcal identification and serotyping.

Higher pneumococcal carriage prevalence among adults has been reported using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based assays directly on upper respiratory tract (URT) samples [17, 18]. Though the lytA gene, the primary target for pneumococcal detection, shares significant homology with nonpneumococcal streptococci [19], cross-reaction of the pneumococcal lytA assay with individual nonpneumococcal isolates is exceedingly rare. However, it does cross-react with URT samples from which pneumococci cannot be recovered [8, 11, 20, 21]. Likewise, non–culture-based PCR serotyping may be unreliable, given current evidence that a high proportion of closely related streptococci contain pneumococcus-like serotype-specific genes [7–9]. In the current study, we directly assessed whether the recommended culture-free lytA PCR method could differentiate pneumococci from oral streptococci carried by adults in URT.

METHODS

Sample Collection and Processing

Paired nasopharyngeal (NP; n = 2400) and oropharyngeal (OP; n = 2400) samples were collected twice a month for 1 year from 100 community-dwelling adults >65 years of age. To minimize the competing flora, the paired NP and OP specimens were pooled, yielding a total of 2400 specimens. The NP and OP swab samples were collected and processed according to the updated WHO recommendations [16] (see Supplementary Materials).

DNA Extraction and lytA Real-Time PCR

DNA was extracted directly from 250 µL of broth-enriched pooled NP + OP samples using RNA STAT-50 LS (Tel Test), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following the WHO recommendations, lytA real time PCR assay was performed to identify pneumococci, as described elsewhere [16, 22] (see Supplementary Materials).

Culture and Species Characterization

Broth samples that were lytA positive were cultured on 5% sheep blood agar supplemented with 5 µg/mL gentamicin. Pneumococci were identified based on the colony morphology and standard biochemical tests (ie, optochin susceptibility and bile solubility) [23, 24]. The culture-positive isolates were subjected to multiple approaches for species confirmation, namely, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS), 16S rRNA sequencing [25], and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) targeting of 4 of the 7 housekeeping genes (ddl, gdh, gki, and recP) [26] (see Supplementary Materials).

Multibead Assays and Whole-Genome Sequencing

Multibead assays and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) were used to deduce the serotype in pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal isolates. Multibead assays were performed as described elsewhere [27]. Chromosomal DNA samples from all 20 isolates were subjected to genomic sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform, as described elsewhere [28] (see Supplementary Materials).

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Serotype Expression

Antigenic relatedness between the pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal counterparts was assessed with flow cytometry, as described elsewhere [29] (see Supplementary Materials).

Clumping of Oral Streptococcal Isolates

Pneumococcal and oral streptococcal isolates expressing cross-reactive capsule types were tested for clumping by the slide agglutination reaction, as described elsewhere [30, 31] (see Supplementary Materials).

RESULTS

Characterization of Pneumococcus-like Isolates in Combined NP + OP Specimens

A total of 2400 combined NP and OP samples obtained from community-dwelling adults were analyzed. As shown in Figure 1, lytA-based PCR detection of S. pneumoniae directly on the extracts of combined NP + OP clinical samples showed positive signals in 301 samples (12.5%). Of these, 57 samples were lost during storage, and 244 (81%) were cultured on sheep blood agar to recover isolates. The bacterial isolates were cultivated from all samples (ie, 1 isolate per sample). Twenty isolates showed presumptive pneumococcal colonies based on colony morphology and biochemical tests (viz, optochin susceptibility and bile solubility tests). Five of them were both optochin susceptible and bile soluble, as pneumococci usually are. However, the remaining 15 isolates produced discordant results (Table 1). In the remaining 224 cultures, colonies grew that were consistent with other α-hemolytic bacteria. The findings may have been different if NP or OP samples were investigated separately. The pooling of the NP and OP samples is a limitation of our sampling design.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of our pneumococcal carriage study according to World Health Organization guidelines. Abbreviations: αHB, α-hemolytic bacteria; BAP, 5% sheep blood agar plate; CO2, carbon dioxide; Gen, gentamicin (5 µg/mL); lytACDC, lytA (autolysin encoding gene) oligonucleotide sequences used by the Centers for Disease Control and prevention; LIM, Todd Hewitt Broth w/colistin and nalidixic acid; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted desorption ionization–time-of-flight (mass spectrometry); MLST, multilocus sequence typing; NP, nasopharyngeal; OP, oropharyngeal; OPT, optochin; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae; STGG, skim milk tryptone glucose glycerol; THY, Todd-Hewitt Broth w/5% yeast extract.

Table 1.

Identification and Species Confirmation of Culture-Positive Isolates

| Strain ID | lytA PCR Resulta,b | Streptococcus Species | 16S rRNA Resultb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optochin Susceptible | Bile Soluble | MLSTc | MALDI-TOF MS | |||

| P095 | + | Yes | No | S. pneumoniae (1203) | S. pneumoniae | + |

| P096 | + | Yes | No | S. pneumoniae (1203) | S. pneumoniae | + |

| P112-2 | + | Yes | Yes | S. pneumoniae (100) | S. pneumoniae | ND |

| P112-3 | + | Yes | No | S. pneumoniae (100) | S. pneumoniae | ND |

| P051-6 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P112-1 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. pneumoniae | + |

| P017 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. mitis/S. oralis | − |

| P074 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P037 | + | Nod | Yes | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P020 | + | Nod | Yes | S. mitis | S. parasanguinis | − |

| P063 | + | Yes | Yes | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P013 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P051 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. sanguinis/S. mitis | ND |

| P066 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. mitis | − |

| P107 | + | Yes | Yes | S. mitis | S. mitis/S. oralis | ND |

| P014 | + | Yes | No | S. mitis | S. pneumoniae/S. mitis | − |

| P085 | + | Nod | Yes | S. oralis | S. mitis/S. oralis | − |

| P053 | + | Yes | Yes | S. pseudopneumoniae | S. pneumoniae/S. pseudopneumoniae | − |

| P106 | + | Yes | No | S. pseudopneumoniae | S. pneumoniae/S. pseudopneumoniae | ND |

| P013-9 | + | Yes | Yes | S. pseudopneumoniae | S. pneumoniae | ND |

Abbreviations: MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; MS, mass spectrometry; ND, not done; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

The lytA PCR assay was performed directly on the combined nasopharyngeal-oropharyngeal extracts. The lytA-positive samples were subsequently cultured, and the colonies were subjected to various identification procedures. MLST, MALDI-TOF MS, and 16S rRNA sequencing were used to identify and confirm the species of isolates recovered from positive samples.

Plus and minus signs indicate positive and negative results.

Parenthetical numbers represent sequence type.

Optochin resistant.

Identification and Confirmation of Species

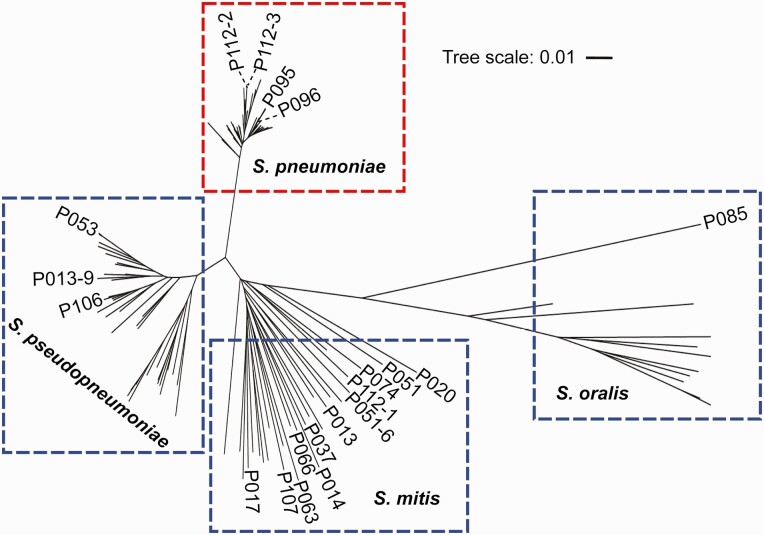

The 20 culture-positive isolates presumed to be pneumococci were subjected to MLST, MALDI-TOF MS, and 16S rRNA sequencing (Table 1). MLST, a reference standard for species determination [26], identified 16 isolates as nonpneumococci. Phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated MLST sequences assorted the streptococcal isolates into 4 different clusters of mitis group streptococci,: S. pneumoniae (n = 4), S. mitis (n = 12), S. oralis (n = 1), and Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae (n = 3) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Species assignment based on phylogenetic analysis. Pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal strains were distributed into different clades/clusters based on the phylogeny of concatenated housekeeping genes targeted in multilocus sequence typing (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/streptococcus-pneumoniae/). The 20 streptococcal strains were analyzed against 105 reference strains belonging to the mitis group of the genus Streptococcus. For clarity purpose only the names of 20 streptococcal strains are shown in the phylogenetic tree. The length of the scale bar represents the estimated evolutionary divergence between species based on average genetic distance. A scale bar of 0.1 indicates 10% nucleotide substitution per site. Abbreviations: S. mitis, Streptococcus mitis; S. oralis, Streptococcus oralis; S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae; S. pseudopneumoniae, Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae.

Consistent with MLST, 11 isolates were correctly identified by MALDI-TOF MS as nonpneumococci at the species level. For the remaining 5 nonpneumococcal isolates (S. pseudopneumoniae [n = 3] and S. mitis [n = 2]), MALDI-TOF MS produced ambiguous results. Likewise, 16S rRNA sequencing of 12 isolates revealed 11 isolates precisely as nonpneumococci. Importantly, all the pneumococcal isolates (n = 4) were accurately identified with all 3 approaches. Out of inquisitiveness, we looked for the conservation of whole lytA gene. While it was found in all isolates, DNA sequence analysis revealed lytA to be 79%–82% conserved between pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal isolates (Supplementary Figure 1). This underlines the rigor with which the oligonucleotide sequences for the pneumococcal lytA must be selected. Indeed, the short oligonucleotide sequences used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lytA assay for the detection of pneumococci shows significant mismatch with the nonpneumococcal lytA sequences. Perhaps piaA may be a better target than lytA in pneumococcus identification, as piaA is not found in other species [32].

Presence of Pneumococcus-like Capsule Biosynthetic Loci in Pneumococcus-like Isolates

Multibead assays and WGS showed 100% correlation in determining the capsule types of 4 pneumococcal isolates (19F [n = 2] and 33F [n = 2]) (Table 2). Multibead assays detected pneumococcus-like serotype-specific genes in 4 of 16 nonpneumococcal isolates (3 S. mitis strains expressing capsule type 45, 10A/39, and 17F and 1 S. oralis strain expressing capsule type 19B). Inevitably, WGS identified cps locus in all 16 nonpneumococcal isolates, with 8 of them showing >70% of nucleotide identity with their pneumococcal counterparts. Interestingly, 12 nonpneumococcal isolates (8 isolates with genomic identity <30% and 4 with genomic identity >70%) were negative by PCR for pneumococcal cpsA gene (Table 2). Taken together, the findings support the utility of the multibead assays for differentiating between pneumococci and nonpneumococci expressing related capsule types.

Table 2.

Serotype Assessment of Pneumococcal and Nonpneumococcal Isolatesa

| Strain ID | Streptococcus Speciesb | Multibead Assay | WGS | Genomic Identity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P095 | S. pneumoniae (1203) | 19F | 19F | 98 |

| P096 | S. pneumoniae (1203) | 19F | 19F | 98 |

| P112-2 | S. pneumoniae (100) | 33F | 33F/A | 100 |

| P112-3 | S. pneumoniae (100) | 33F | 33F/A | 100 |

| P051-6 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 25A | 11 |

| P112-1 | S. mitis | cpsA−, NCC2c | 35B | 11 |

| P017 | S. mitis | cpsA−, NCC3c | 29 | 12 |

| P037 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 36 | 18 |

| P020 | S. mitis | cpsA−, NCC3c | 1 | 24 |

| P063 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 5 | 73 |

| P013 | S. mitis | 45 | 45 | 73 |

| P051 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 24A | 73 |

| P074 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 35B | 75 |

| P066 | S. mitis | 10A/39 | 39 | 77 |

| P107 | S. mitis | 17F | 17F | 85 |

| P014 | S. mitis | cpsA− | 24F/B/A | 88 |

| P085 | S. oralis | 19B | 19B | 86 |

| P053 | S. pseudopneumoniae | cpsA− | 33F/33A | 11 |

| P106 | S. pseudopneumoniae | cpsA− | 36 | 26 |

| P013-9 | S. pseudopneumoniae | cpsA− | 36 | 27 |

Abbreviations: cpsA−, negative result for pneumococcal cpsA gene; ID, identifier; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; NCC2 and NCC3, null capsule clades 2 and 3; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Serotypes of pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal strains were determined using multibead assays and WGS. Genomic identity represents the percentage of nucleotide identity between the matching pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal cps loci.

Parenthetical numbers represent sequence type.

Nonencapsulated variants of S. pneumoniae classified by clade [33].

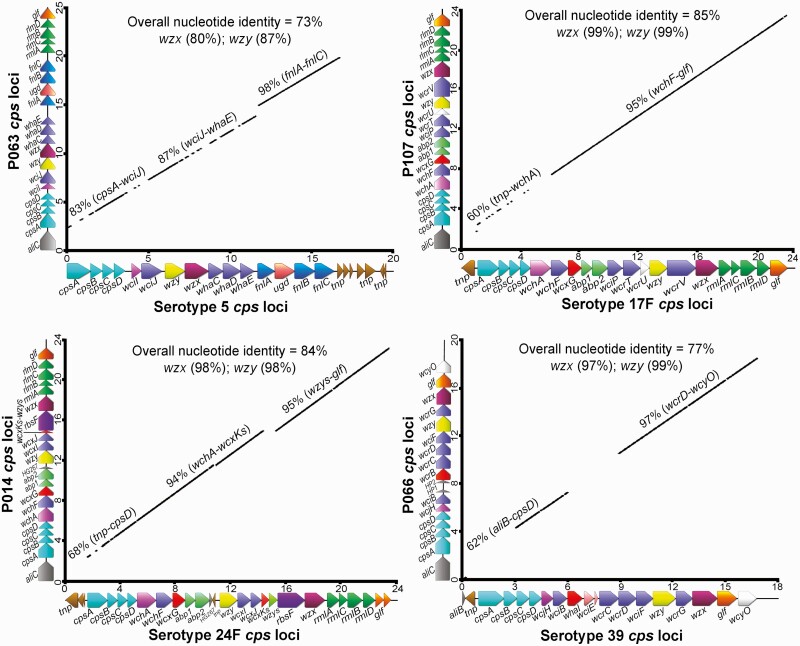

Among the 16 nonpneumococcal genomes analyzed, we found that 8 included full pneumococcus-like cps operons flanked by 5ʹ dexB and 3ʹ aliA genes, with an approximate size range of 18–25 kb. For instance, P063 and P066, S. mitis strains, carried pneumococcus-like cps5 and cps39 loci, with overall nucleotide identities of 73% and 77% with their pneumococcal counterparts, respectively (Figure 3). Similarly, the genomes of other 6 nonpneumococcal strains—P013, P014, P051, P074, P085, and P107—were found to harbor pneumococcus-like cps45, cps24F, cps24A, cps35B, cps19B, and cps17F, respectively, with overall nucleotide identity ranging between 73% and 88%. Likewise, the serotype-specific genes of pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal cps loci, such as wzx (flippase) and wzy (repeat unit polymerase) shared substantial homology, with nucleotide identities ranging of 80%–99% and 87%–99%, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Genomic analysis of nonpneumococcal isolates carrying pneumococcus-like cps loci. A, Comparison of cps5 loci between pneumococci serotype 5 (GenBank accession no. CR931637) and nonpneumococcal strain, P063. B, Comparison of cps17F loci between pneumococci serotype 17F (GenBank accession no. CR931670) and nonpneumococcal strain, P107. C, Comparison of cps24F loci between pneumococci serotype 24F (GenBank accession no. CR931686) and nonpneumococcal strain, P104. D, Comparison of cps39 loci between pneumococci serotype 39 (GenBank accession no. CR931711) and nonpneumococcal strain, P066. In each panel, the x-axis shows the pneumococcal cps loci gene arrangement, and the nonpneumococcal cps loci are plotted on the y-axis. The numbers on both axes relate to arbitrary nucleotide base numbers (in kilobases) to show relative size. solid black lines represent homologous regions, with the percentage nucleotide identity indicated above the line.

Although the cps loci of our oral streptococcal strains and pneumococcal serotypes shared relatively similar gene organization and extensive sequence homology, several differences in the structure of cps operons were observed. For instance, the approximately 3-kb fragment comprising several transposase (tnp) genes at the 3ʹ end of the pneumococcal cps5 loci, was substituted for with the rhamnosyl biosynthetic genes (rlmA, rmlC, rmlB, and rmlD) and the galactopyranose mutase gene (glf) in P063. Likewise, in pneumococcal cps39, a ribitol transferase gene, whaI, and a nonfunctional gene, wciE, was found, whereas, an orthologue ribitol transferase gene, wcrB (48% nucleotide identity with whaI) without a wciE-like gene was identified in P066. Moreover, immediately downstream from dexB, the cps loci of all our nonpneumococcal strains carried oligopeptide ABC transporter genes (aliC- or aliB-like). Conversely, some pneumococcal strains representing serotypes 5, 17F, 24F, and 24A carried 1 or several transposase genes instead. More importantly, the regulatory region encompassing wzg, wzh, wzd, and wze genes (cpsABCD) showed low sequence homology (nucleotide identity of 76%–88%) between pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal cps operons (Supplementary Figure 2). These differences, especially in the regulatory region of cps loci, could serve as a marker to distinguish oral streptococci from pneumococci.

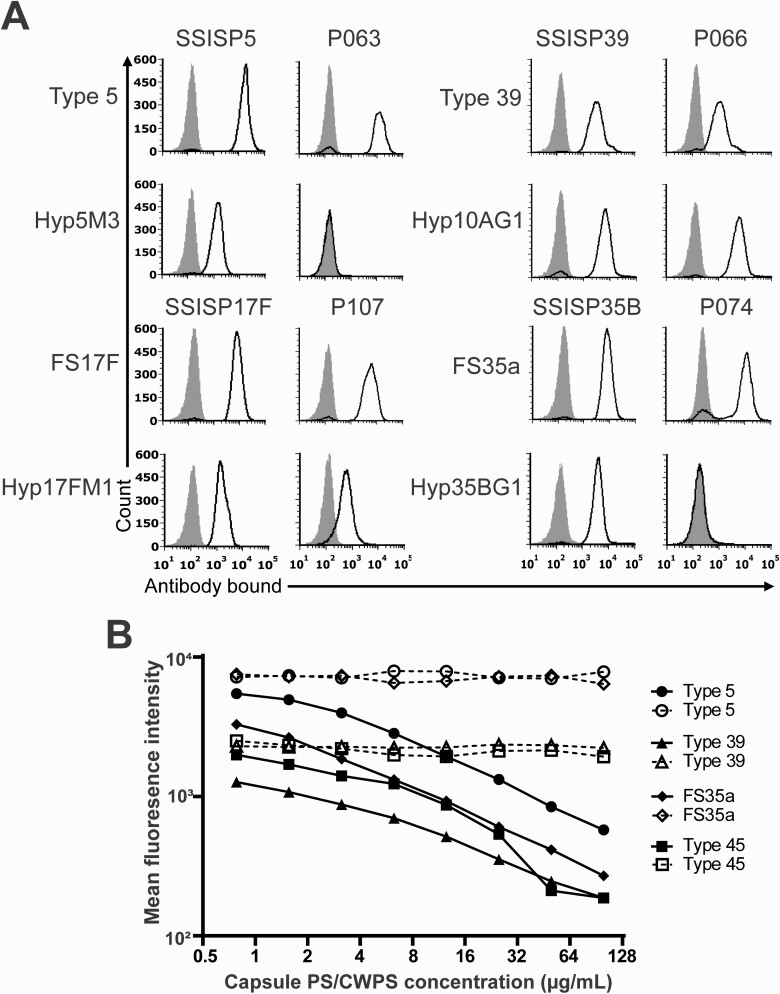

Phenotypic Expression of Surface Capsule Polysaccharide in Oral Streptococcal Strains

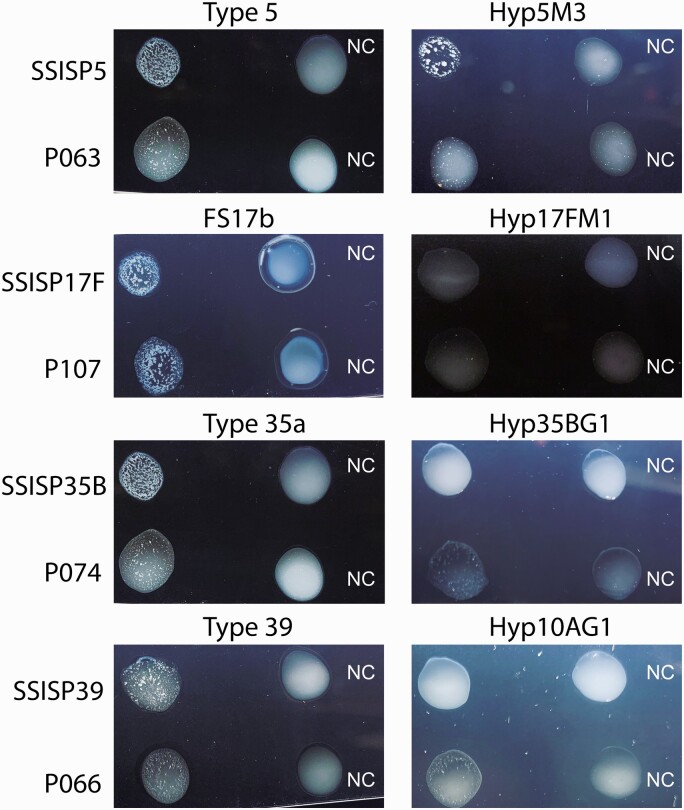

To show that oral streptococcal strains not only have the cps genes but actually display capsule PS on their surface, we examined 4 S. mitis strains with evidence of full cps loci. P066 and P107, the S. mitis strains harboring cps39-like and cps17F-like loci, reacted with both polyclonal (type 39 and FS17F) and monoclonal (Hyp10AG1 and Hyp17FM1) antisera. On the contrary, 2 other S. mitis strains carrying cps5-like and cps35B-like loci, P063 and P074, reacted only with the pneumococcal-specific polyclonal antisera (type 5 and FS35a) (Figure 4A). The failure of S. mitis strains P063 and P074 to react with their specific monoclonal antisera (Hyp5M3 and Hyp35BG1) implies that these strains may produce structurally different capsule PS than that observed for recognized pneumococcal capsules types 5 and 35B.

Figure 4.

Serological properties of oral streptococcal strains displaying cross-reactive capsule on their surface. A, Histograms show fluorescence of a bacterial strain (indicated above each column of histograms) after straining with the indicated serological reagents (indicated to the left of the columns). Pneumococcal strains SSISP5, SSISP39, SSISP17F, and SSISP35B represent serotypes 5, 39, 17F, and 35B, respectively. Likewise, nonpneumococcal strains P063-5, P066-7, P107-1, P074-16 represent the corresponding cross-reactive serotypes. Solid black lines indicate the fluorescence obtained with primary and secondary antibodies; gray shaded areas, control binding (secondary antibody alone). The x-axes show the log fluorescence intensity, and the y-axes, the number of events (cell counts). The polyclonal rabbit antisera (type 5, type 39, FS17F, and FS35a) were obtained from Statens Serum Institut (SSI). Hyp5M3, Hyp10AG1, Hyp17FM1, Hyp35BG1 are our in-house serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies [27]. Each strain was tested 3 times, and representative results are shown. B, Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of pneumococcal isolates (labeled on y-axis) with the serotype-specific polyclonal rabbit antisera preincubated with different inhibitory concentrations (0–120 µg/mL) of free capsule polysaccharide (PS) or cell wall PS (CWPS) (labeled on x-axis). Solid black lines represent inhibitory curves with free capsule PS; dashed black lines, inhibitory curves with free CWPS. Other Streptococcus mitis strains (P013, P014, and P051) reacted with the polyclonal rabbit antisera in a similar manner as the strains shown in the figure (data not shown). Monoclonal antibodies for these strains were not available.

To determine the specificity of the polyclonal rabbit antisera, we studied binding of several polyclonal antisera against the different inhibitory concentrations of free capsule PS or cell-wall PS. For all antisera tested, the mean fluorescence intensity decreased with the increase in the inhibitory concentration of the type-specific free capsule PS. Most importantly, no inhibitory effect of the free cell-wall PS was observed, suggesting specific binding of polyclonal antisera to the capsule PS displayed on the surface of the pneumococci or nonpneumococcal strains (Figure 4B).

Agglutination of Oral Streptococci by Pneumococcal-Specific Antisera

Several oral streptococcal isolates expressing cross-reactive capsule types were tested for agglutination with pneumococcal-specific antisera. P063-, P074-, and P066-expressing capsule types 5, 35B, and 39 agglutinated with both pneumococcal specific polyclonal and monoclonal antisera (Figure 5). Another oral streptococcal strain, P107, agglutinated only with the polyclonal antisera. These findings of antibody-mediated agglutination suggest that immune response to pneumococci would limit the carriage of oral streptococci expressing cross-reactive serotypes.

Figure 5.

Clumping of pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal isolates by pneumococcal-specific polyclonal and monoclonal antisera. The strain names are indicated on the left side, and the antisera at the top. Type 5, FS17b, type 35a, and type 39 are polyclonal rabbit antisera; Hyp5M3, Hyp17FM1, Hyp35BG1, and Hyp10AG1 are monoclonal antisera. The positive reaction is indicated by the appearance of small clumps after the addition of antisera. Abbreviation: NC, negative control.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of pneumococcal colonization varies with age, environment, and the presence of URT infections. Pneumococci may be isolated from the URT of 5%–90% of healthy people [34], with asymptomatic carriage occurring in 40%–95% of young children and 1%–10% in adults [4, 5, 35, 36]. Although the occurrence in adults is lower than in the pediatric population, the use of molecular approaches has challenged the well-known perception that older adults are only infrequent carriers [37]. However, the relative abundance of cross-reactive oral streptococci carrying pneumococcus-like cps loci casts serious reservations on carriage studies that rely entirely on culture-free detection methods [8, 9, 11, 21, 38]. Because the streptococcal species that inhabit URT sites demonstrate significant variety, the available knowledge of capsular overlap and genetic diversity in these ecological niches is limited. Therefore, following the WHO guidelines, we applied molecular methods to broth-enriched combined NP + OP samples from adults to investigate whether oral streptococci carrying pneumococcus-like cps loci would affect the recommended carriage procedure.

It is now well established that many oral streptococci carry cps loci, some of which are similar to pneumococcal cps loci [8, 9, 11, 21, 38]. Indeed, we confirmed that oral streptococcus often exhibits pneumococcus cps-like features. Our oral streptococcal isolates with >70% nucleotide identity with known pneumococcal cps operons had complete cps loci flanked between dexB and aliA genes. The exclusive features in the cps loci of oral streptococcal strains were the presence of oligonucleotide transport genes (aliC–like or aliB-like) immediately downstream of the dexB and the lack of transposase genes. Whereas the cps loci of several recognized pneumococcal counterparts studied (eg, serotypes 5, 17F, 24F, and 24A) did not include aliB-like genes but instead showed the presence of ≥1 transposase gene. Typically, the pneumococcus cps locus lacks functional aliB-like genes, but there is evidence of their prior existence in the form of tiny remnants or pseudogenes (eg, serotypes 1, 2, 14, and 25F). The exact reasons for their absence in pneumococci or presence in oral streptococci are unknown [13, 39, 40].

Although the cps loci of oral streptococci and corresponding pneumococcal serotypes had a similar gene structure and substantial homology, we show that oral streptococci have a more distinct regulatory region encompassing cpsABCD genes (nucleotide identity, 76%–88%). Owing to the sequence diversity in the regulatory genes, this region could serve as a distinguishing feature between encapsulated pneumococci and oral streptococci [41–43]. Furthermore, it has been reported that some oral streptococci expressing cross-reactive capsule types trigger opsonic antibodies [7, 8, 44]. However, we could not test cross-species immunity because our nonpneumococcal strains expressing vaccine-type capsules showed high complement-mediated nonspecific killing (>70%) (see Supplementary Materials for assay details). Studies have shown that allelic variations in the cps promoter or regulatory genes affect the amount of encapsulation or PS chain length [45–47]. Although oral streptococci produce relatively thin capsules with insufficient shielding [7, 48], we previously demonstrated that interspecies transfer of cps loci from commensal streptococcal strains could impart virulence property to acapsular pneumococci by enhancing the capsule expression in the pneumococcal genetic background [12]. Such scenarios ascertain the significance of nonpneumoccal capsules in the evolution and genetic diversity of the pneumococcal capsules [10].

Furthermore, the positive reaction of S. mitis strains (eg, P066 and P107) carrying pneumococcus-like cps39 and cps17F loci with the pneumococcal specific polyclonal and monoclonal antisera describes the antigenic form similar to their pneumococcal counterparts. Although the biochemical information about the oral streptococcal capsules is inadequate, it is possible to predict the biochemical structure of capsules based on the assortment and biosynthetic role of the cps genes [10]. For instance, the predicted capsule structure of P066 resembles very closely that of pneumococcal serotype 39 (Supplementary Figure 3). The only difference between them is the presence of orthologues of ribitol transferase gene. In capsule type 39, whaI gene is responsible for ribitol (5→P→6) galactose linkage, whereas wcrB in P066 may be responsible for ribitol (5→P→5) galactose linkage, similar to capsule type 10A. The structural similarity in Galp, Galf, and GalNAc residues in capsule types 39, 10A, and P066 explains the serological cross-reactivity. Conversely, some S. mitis strains (eg, P063 and P074) failed to react with pneumococcal-specific monoclonal antisera, possibly owing to the absence of the targeted epitope. Hence, such strains with a distinct genetic structure of cps loci may produce structurally different capsules.

Given the substantial homology of lytA gene, it is not surprising if studies encounter problems using lytA-based PCR or comparable tests for identifying pneumococci directly from URT samples [21, 38]. As a result, pneumococcal carriage studies based solely on molecular approach without isolating the bacteria are unreliable. Studies using lytA PCR have found a high cumulative incidence of pneumococcal carriage in older adults, reporting a prevalence of 0%–20% among healthy adults and >50% among individuals with comorbid conditions [17, 49, 50]. Thus, it is more likely that the pneumococcal carriage rate in older adults using molecular methods is overestimated. Moreover, culture-free serotyping of pneumococcus could also be erroneous, given the high genetic similarity with closely related streptococci. In a recent report, investigators demonstrated capsule production in 74% of S. mitis strains [7]. In coherence with such findings, 8 of our nonpneumococcal strains (7 S. mitis and 1 S. oralis) showed >70% nucleotide identity with the recognized pneumococcal serotypes. Thus, serotyping of culture-positive colonies would better characterize nonpneumococcal streptococci, which carry capsular material.

Indeed, we see an increase in the number of capsule types shared by pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal counterparts, and we might discover many more cross-reactive capsule types in nature [7, 11]. To avoid the ambiguities of the pneumococcal and nonpneumococcal capsule types, there should be a logical and widely acknowledged way of naming oral streptococcal capsule types. First, a capsule type can be designated as a new serotype if it proves to have a unique capsule structure, serology, and genetic basis. If the capsule of S. oralis or S. mitis species is biochemically identical to the pneumococcal capsule, the serotype name should be the same as the pneumococcal serotype with the prefix SO or SM, which stands for S. oralis or S. mitis, respectively. For instance, an S. oralis strain, SK95, produces a capsule identical to S. pneumoniae serotype 2 [12], so the SK95 serotype may be referred to as SO2. If only the cps locus is known, we should add X to its serogroup name (eg, SO35X or SM35X) until its biochemical structure is confirmed (with the X used to emphasize the experimental nature of the serotype).

Finally, given that oral microbiota is highly personalized, dynamic, and sensitive to perturbations, there is a question about the impact of pneumococcal vaccines on the oral microbiome. Pneumococcal-specific antibodies produced in response to the pneumococcal vaccines have been shown to aggregate pneumococci in the nasopharynx, a mechanism to prevent the colonization of vaccine serotypes [51]. We show that pneumococcal-specific antisera also agglutinate oral streptococci. With the demonstration of the capsule (serology) overlap and cross-reactive aggregation, it is enticing to hypothesize that pneumococcal vaccines would alter the repertoire of oral streptococcal capsules by limiting the carriage of oral streptococci expressing cross-reactive capsule types [12, 52] and could disrupt the homeostasis of the oral microbiome [53–55]. As we deploy highly immunogenic next-generation pneumococcal vaccines with broad serotype coverage [56, 57], we may see a change in the oral streptococcal flora expressing vaccine or nonvaccine capsular material.

In conclusion, detection of oral streptococci as pneumococci using non–culture-based PCR assays likely overestimates the true carriage rate and expands the pool of serotypes. Therefore, the current WHO recommendation of using non–culture-based molecular methods as an option for enhancing pneumococcal identification and serotyping needs to be revisited.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIAID, National Institute of Health (contract HHSN27220120005C).

Contributor Information

Feroze Ganaie, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Angela R Branche, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, USA.

Michael Peasley, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, USA.

Jason W Rosch, Department of Infectious Diseases, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA.

Moon H Nahm, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Data Availability

Sequences for the complete cps locus from oral streptococcus strains (P013, P014, P051, P063, P066, and P107) were uploaded to GenBank and assigned accession numbers MZ857149–MZ857154.

References

- 1. Deo PN, Deshmukh R.. Oral microbiome: unveiling the fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019; 23:122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abranches J, Zeng L, Kajfasz JK, et al. Biology of oral streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 2018; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Henriques-Normark B, Tuomanen EI.. The pneumococcus: epidemiology, microbiology, and pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; 3:a010215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jochems SP, Weiser JN, Malley R, Ferreira DM.. The immunological mechanisms that control pneumococcal carriage. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldblatt D, Hussain M, Andrews N, et al. Antibody responses to nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults: a longitudinal household study. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, et al. Pneumococcal capsules and their types: past, present, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28:871–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sorensen UB, Yao K, Yang Y, Tettelin H, Kilian M.. Capsular polysaccharide expression in commensal Streptococcus species: genetic and antigenic similarities to Streptococcus pneumoniae. mBio 2016; 7:e01844-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lessa FC, Milucky J, Rouphael NG, et al. Streptococcus mitis expressing pneumococcal serotype 1 capsule. Sci Rep 2018; 8:17959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pimenta F, Gertz RE Jr, Park SH, et al. Streptococcus infantis, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus oralis strains with highly similar cps5 loci and antigenic relatedness to serotype 5 pneumococci. Front Microbiol 2018; 9:3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ganaie F, Saad JS, McGee L, et al. A new pneumococcal capsule type, 10D, is the 100th serotype and has a large cps fragment from an oral streptococcus. mBio 2020; 11:e00937-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gertz RE Jr, Pimenta FC, Chochua S, et al. Nonpneumococcal strains recently recovered from carriage specimens and expressing capsular serotypes highly related or identical to pneumococcal serotypes 2, 4, 9A, 13, and 23A. mBio 2021; 12:e01037-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nahm MH, Brissac T, Kilian M, et al. Pneumococci can become virulent by acquiring a new capsule from oral streptococci. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:372–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kilian M, Riley DR, Jensen A, Bruggemann H, Tettelin H.. Parallel evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus mitis to pathogenic and mutualistic lifestyles. mBio 2014; 5:e01490–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conklin L, Loo JD, Kirk J, et al. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease among young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:S109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M.. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet 2011; 378:1962–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Satzke C, Turner P, Virolainen-Julkunen A, et al. Standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: updated recommendations from the World Health Organization pneumococcal carriage working group. Vaccine 2013; 32:165–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Deursen AM, van den Bergh MR, Sanders EA; Carriage Pilot Study G. . Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in asymptomatic, community-dwelling elderly in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2016; 34: 4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Branche AR, Yang H, Java J, et al. Effect of prior vaccination on carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in older adults: a longitudinal surveillance study. Vaccine 2018; 36:4304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simões AS, Tavares DA, Rolo D, et al. lytA-Based identification methods can misidentify Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 85:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wyllie AL, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, van Houten MA, et al. Molecular surveillance of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in children vaccinated with conjugated polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carvalho Mda G, Pimenta FC, Moura I, et al. Non-pneumococcal mitis-group streptococci confound detection of pneumococcal capsular serotype-specific loci in upper respiratory tract. PeerJ 2013; 1:e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carvalho Mda G, Tondella ML, McCaustland K, et al. Evaluation and improvement of real-time PCR assays targeting lytA, ply, and psaA genes for detection of pneumococcal DNA. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burckhardt I, Panitz J, Burckhardt F, Zimmermann S.. Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae: development of a standardized protocol for optochin susceptibility testing using total lab automation. Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017:4174168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arbique JC, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, et al. Accuracy of phenotypic and genotypic testing for identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and description of Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:4686–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Aila NA, Emler S, Kaijalainen T, et al. The development of a 16S rRNA gene based PCR for the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with four other species specific PCR assays. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Enright MC, Spratt BG.. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 1998; 144:3049–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yu J, Lin J, Kim KH, Benjamin WH Jr, Nahm MH.. Development of an automated and multiplexed serotyping assay for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011; 18:1900–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ganaie F, Maruhn K, Li C, et al. Structural, genetic, and serological elucidation of Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 24 serotypes: discovery of a new serotype, 24C, with a variable capsule structure. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59: e00540-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geno KA, Saad JS, Nahm MH.. Discovery of novel pneumococcal serotype 35D, a natural wciG-deficient variant of serotype 35B. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55:1416–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calix JJ, Oliver MB, Sherwood LK, Beall BW, Hollingshead SK, Nahm MH.. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 9A isolates contain diverse mutations to wcjE that result in variable expression of serotype 9V-specific epitope. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:1585–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henrichsen J. Six newly recognized types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33:2759–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whalan RH, Funnell SG, Bowler LD, Hudson MJ, Robinson A, Dowson CG.. Distribution and genetic diversity of the ABC transporter lipoproteins PiuA and PiaA within Streptococcus pneumoniae and related streptococci. J Bacteriol 2006; 188:1031–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Park IH, Kim KH, Andrade AL, Briles DE, McDaniel LS, Nahm MH.. Nontypeable pneumococci can be divided into multiple cps types, including one type expressing the novel gene pspK. mBio 2012; 3: e00035–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gierke R, Wodi P, Kobayashi M.. Pneumococcal disease. In: Hall E, Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schillie S. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 14th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, 2021:255–72. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sa-Leao R, Nunes S, Brito-Avo A, et al. High rates of transmission of and colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae within a day care center revealed in a longitudinal study. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hamaluba M, Kandasamy R, Ndimah S, et al. A cross-sectional observational study of pneumococcal carriage in children, their parents, and older adults following the introduction of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith EL, Wheeler I, Adler H, et al. Upper airways colonisation of Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults aged 60 years and older: a systematic review of prevalence and individual participant data meta-analysis of risk factors. J Infect 2020; 81:540–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carvalho Mda G, Bigogo GM, Junghae M, et al. Potential nonpneumococcal confounding of PCR-based determination of serotype in carriage. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:3146–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Claverys JP, Grossiord B, Alloing G.. Is the Ami-AliA/B oligopeptide permease of Streptococcus pneumoniae involved in sensing environmental conditions? Res Microbiol 2000; 151:457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hathaway LJ, Battig P, Reber S, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae detects and responds to foreign bacterial peptide fragments in its environment. Open Biol 2014; 4:130224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yother J. Capsules of Streptococcus pneumoniae and other bacteria: paradigms for polysaccharide biosynthesis and regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol 2011; 65:563–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morona JK, Paton JC, Miller DC, Morona R.. Tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD negatively regulates capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 2000; 35:1431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bender MH, Cartee RT, Yother J.. Positive correlation between tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD and capsular polysaccharide production in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 2003; 185:6057–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shekhar S, Khan R, Ferreira DM, et al. Antibodies reactive to commensal Streptococcus mitis show cross-reactivity with virulent Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes. Front Immunol 2018; 9:747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wen Z, Liu Y, Qu F, Zhang JR.. Allelic variation of the capsule promoter diversifies encapsulation and virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Sci Rep 2016; 6:30176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shainheit MG, Mule M, Camilli A.. The core promoter of the capsule operon of Streptococcus pneumoniae is necessary for colonization and invasive disease. Infect Immun 2014; 82:694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morona JK, Miller DC, Morona R, Paton JC.. The effect that mutations in the conserved capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis genes cpsA, cpsB, and cpsD have on virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 2004; 189:1905–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yurchak AM, Austrian R.. Serologic and genetic relationships between pneumococci and other respiratory streptococci. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1966; 79:368–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krone CL, Wyllie AL, van Beek J, et al. Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in aged adults with influenza-like-illness. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0119875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ansaldi F, de Florentiis D, Canepa P, et al. Carriage of Streptoccoccus pneumoniae in healthy adults aged 60 years or over in a population with very high and long-lasting pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage in children: rationale and perspectives for PCV13 implementation. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mitsi E, Roche AM, Reine J, et al. Agglutination by anti-capsular polysaccharide antibody is associated with protection against experimental human pneumococcal carriage. Mucosal Immunol 2017; 10:385–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kilian M. The oral microbiome - friend or foe? Eur J Oral Sci 2018; 126:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hammitt LL, Etyang AO, Morpeth SC, et al. Effect of ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease and nasopharyngeal carriage in Kenya: a longitudinal surveillance study. Lancet 2019; 393:2146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dunne EM, Manning J, Russell FM, Robins-Browne RM, Mulholland EK, Satzke C.. Effect of pneumococcal vaccination on nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus in Fijian children. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:1034–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Littorin N, Ahl J, Udden F, Resman F, Riesbeck K.. Reduction of Streptococcus pneumoniae in upper respiratory tract cultures and a decreased incidence of related acute otitis media following introduction of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in a Swedish county. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Skinner JM, Indrawati L, Cannon J, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV15-CRM197) in an infant-rhesus monkey immunogenicity model. Vaccine 2011; 29:8870–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Emini EA, Watson WJ, Prasad AK, et al. US patent 20150202309. 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequences for the complete cps locus from oral streptococcus strains (P013, P014, P051, P063, P066, and P107) were uploaded to GenBank and assigned accession numbers MZ857149–MZ857154.