Summary:

In the central nervous system (CNS), execution of programmed cell death (PCD) is crucial for proper neurodevelopment. However, aberrant activation of these pathways in adult CNS leads to neurodegenerative diseases including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). How a cell dies is critical, as it can drive local immune activation and tissue damage. Classical apoptosis engages several mechanisms to evoke “immunologically silent” responses, whereas other forms of programmed death such as pyroptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis release molecules that can potentiate immune responses and inflammation. In ALS, a fatal neuromuscular disorder marked by progressive death of lower and upper motor neurons, several cell types in the CNS express machinery for multiple PCD pathways. The specific cell types engaging PCD, and ultimate mechanisms by which neuronal death occurs in ALS are not well defined. Here we provide an overview of different PCD pathways implicated in ALS. We also examine immune activation in ALS and differentiate apoptosis from necrotic mechanisms based on downstream immunological consequences. Lastly, we highlight therapeutic strategies that target cell death pathways in the treatment of neurodegeneration and inflammation in ALS.

Keywords: Cell death, innate immunology, neurodegeneration

Introduction: cell death in the CNS

For the organism to live, some cells must die. Seminal studies in developmental biology have shown that normal development and tissue homeostasis rely upon programmed cell death (PCD). For instance, the death of cells in the apical ectodermal ridge sculpts the digits of developing vertebrate limbs during embryogenesis (Nelson et al., 1996; Zhu et al., 2008). Early work mapped morphological features of cells in the process of “orderly” elimination (Kerr et al., 1972). Collectively, these features—cytoplasmic shrinkage, nuclear condensation, fragmentation, and the budding small bodies—were termed “apoptosis” (Kerr et al., 1972).

The central nervous system (CNS), comprised of the brain and spinal cord, is sculpted by apoptotic events in neural precursor cells (NPCs), differentiated post-mitotic neurons, and glial cells (Kuan et al., 2000). Only the cells with appropriate connections, location, size, and shape are needed for CNS homeostasis. Superfluous neurons are eliminated, and axonal projections “pruned”; between birth and adulthood humans lose an estimated 15% of their neurons (Huttenlocher, 1979). In transgenic mice lacking effectors of apoptosis (such as Apaf-1 and caspase-3/9), the CNS is the most affected tissue, presenting with a glut of neurons contained in disorganized structures (Honarpour et al., 2000; Kuida et al., 1998). Collectively, studies describing the process of neurodevelopment highlight the importance of apoptotic cell death in sculpting normal CNS architecture. (Kuan et al., 2000; Nijhawan et al., 2000).

Although life begins with elimination of unwanted neurons and is necessary for proper development, aberrant death of distinct CNS regions is a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The upstream etiologies of neurodegenerative diseases are diverse and multifactorial (Gan et al., 2018; Hardiman et al., 2017). A combination of aging, genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers disrupt neuronal function and initiate these pathologies. Broad signaling networks, such as oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial damage, and ER stress have all been implicated in driving downstream neuronal cell death in patients and transgenic mouse disease models (reviewed in Bock and Tait, 2020; Murali Mahadevan et al., 2021; Uttara et al., 2009).

While many studies originally indicated that neurodegeneration often culminates in apoptotic cell death (Pasinelli et al., 2000), close pathological examination of degenerating tissues reveals some puzzling findings. For example, neurodegeneration patient samples display features inconsistent with orderly apoptosis—swollen neurons with punctured plasma membranes, release of intracellular contents and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), elevated levels of cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and progressive neuroinflammation (Kwon and Koh, 2020a; Liu and Wang, 2017a; McGeer and McGeer, 2010, 2004; Texidó et al., 2011). These findings challenge our traditional notions of apoptotic death, which is classically considered “immunologically silent” (Birge and Ucker, 2008; Szondy et al., 2017).

Recent advances in the fields of cell death and innate immunology have uncovered novel programmed necrotic pathways—namely necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis. Unlike apoptosis, these modes of cell death culminate in plasma membrane disruption (i.e. necrosis). Over the last decade, elegant investigations have revealed that these necrotic PCD (programmed cell death) mechanisms lead to coordinated release of pro-inflammatory intracellular molecules (e.g., DAMPs and cytokines) that activate the immune system. Further, these modes of cell death often promote tissue damage, inflammation and are closely linked to onset of pathology in vivo (Green, 2016; Heckmann et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2019).

Could activation of these necrotic pathways drive chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? The molecular mechanisms that initiate activation of glial cells (e.g., astrocytes and microglia) and infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the degenerating CNS are not well understood. Further, how neuroinflammation potentiates neuronal demise on a cellular signaling level also remains an open area of investigation. Linking programmed cell death mechanisms to neuroinflammation will advance our basic understanding of neuroimmunology and provide new therapeutic strategies for patients.

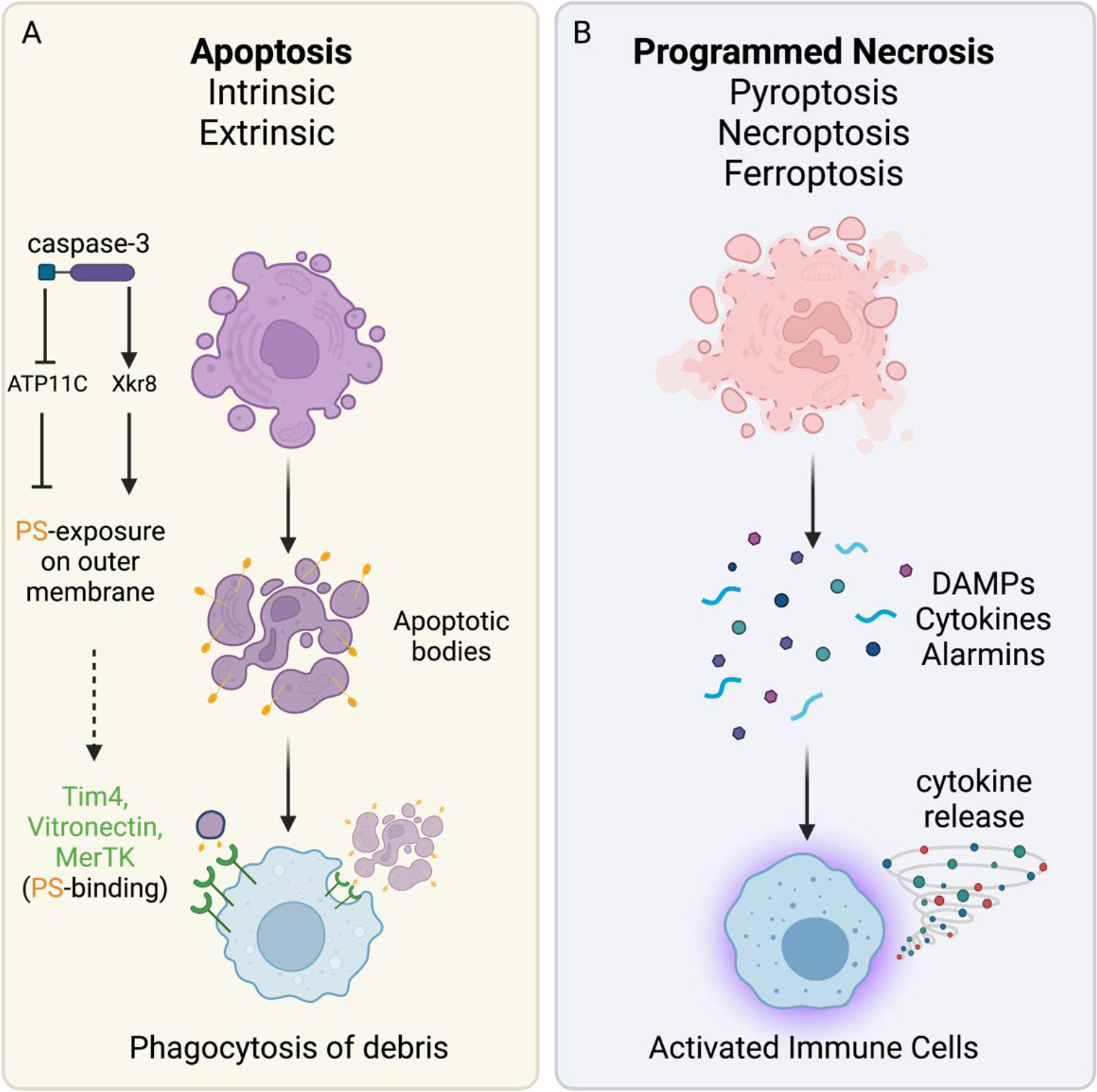

This review provides an overview of the different PCD pathways implicated in ALS, differentiating apoptosis from necrotic mechanisms by describing downstream immunological consequences (Figure 1). We examine the specific evidence for immune activation in ALS and investigate the known and proposed roles of apoptotic, necroptotic and pyroptotic cell death in disease progression. Lastly, we highlight therapeutic strategies that target cell death pathways and discuss proposed crosstalk between apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Ultimately, inhibition of multiple cell death “culprits” may provide the greatest benefit for ALS patients.

Figure 1: Immunological outcomes of apoptosis versus programmed necrotic mechanisms.

(A) Apoptosis induced either by the intrinsic pathway or by extrinsic death receptor signaling (e.g. TNFR1 and CD95) leads to characteristic morphological changes: nuclear condensation, cell shrinkage, budding of apoptotic bodies. Caspase-mediated inhibition of the ATP11C flippase and activation of Xkr8 scramblase exposes phosphatidyl-serine residues (PS) on the outside of the plasma membrane. Macrophages use several receptors (e.g. TIM4 and MERTK) to bind exposed PS residues (”eat me” signal) and phagocytose debris. (B) Programmed necrotic mechanisms display morphologic features of cellular swelling and loss of plasma membrane integrity. Necrosis culminates in the release of cytokines, chemokines, DAMPs and other intracellular molecules. These cellular contents are sensed by immune cells, which engage innate immune pathways (eg. TLRs, RAGE1, RIGI/MAVS) to promote activation and boost local inflammation.

I. ALS and neuroinflammation

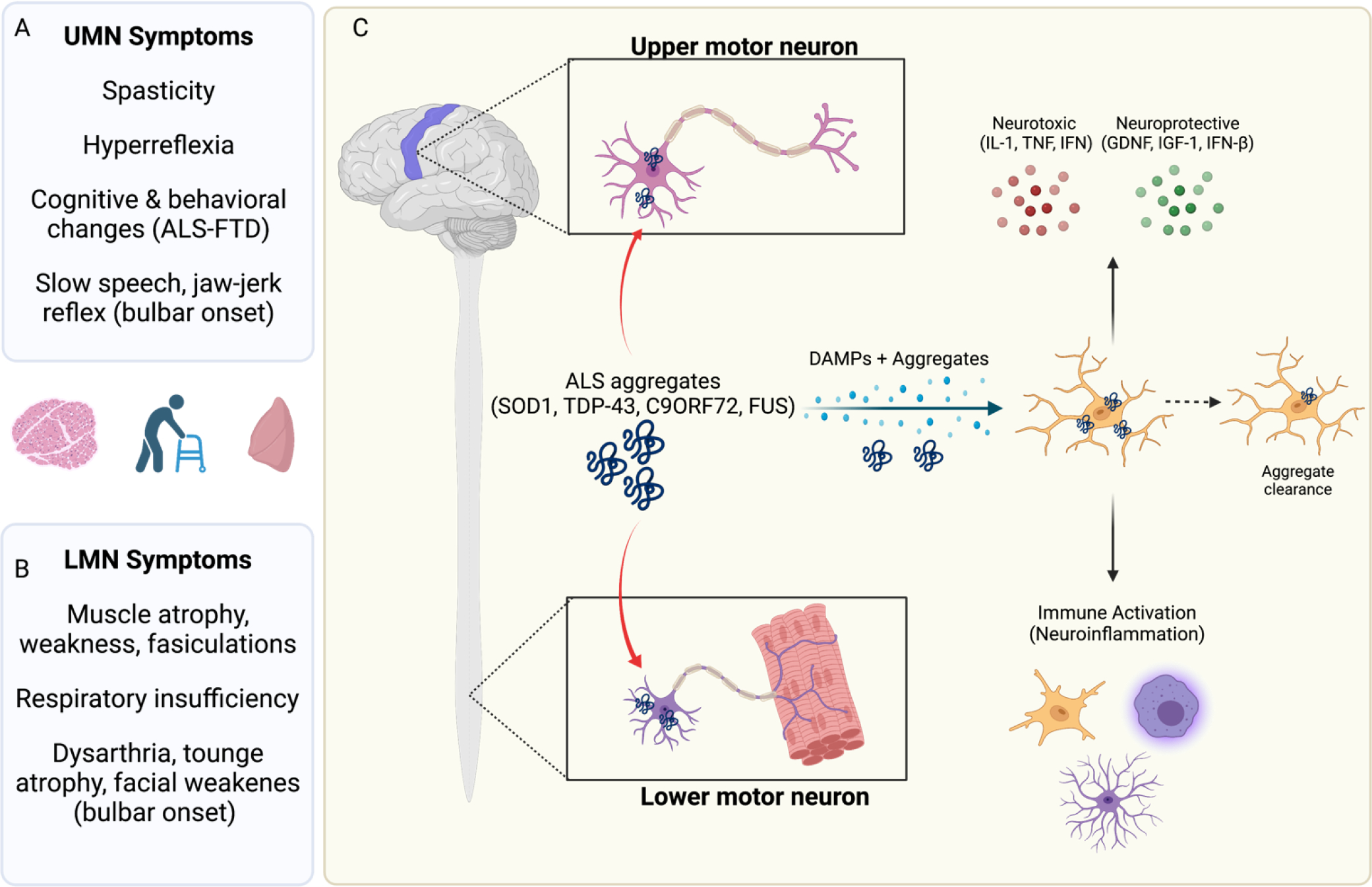

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal, progressive adult-onset form of neuromuscular disease caused by the aberrant death of upper and lower motor neurons in the cerebral cortex and spinal cord (Figure 2). Clinically, these patients present with muscle atrophy, weakness, twitches, spasticity, respiratory failure and ultimately death (Masrori and van Damme, 2020). Roughly 30% of patients first lose motor neurons in the corticobulbar region of the brainstem; this leads to early “bulbar” symptoms such as hoarse voice, impaired speech, difficulty swallowing and vocal cord spasms (Hardiman et al., 2017; Masrori and van Damme, 2020). A small proportion of patients may also present with the related condition frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which shares common genetic features with ALS (Al-Chalabi et al., 2017; Ferraiuolo et al., 2011). FTD is a progressive brain disorder that causes death of cortical neurons affecting personality, behavior, and language. Though the majority (90%) of ALS is sporadic, several mutations have been identified that cause familial ALS and/or FTD: these include superoxide dismutase (SOD1), TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43), C9ORF72 and FUS (Al-Chalabi et al., 2017). Myriad signaling processes have been associated with disease progression, including oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction and downstream caspase activation (Ferraiuolo et al., 2011). No effective disease modifying therapy is currently available for ALS patients. Approved by the FDA in 1996, the anti-glutamatergic drug Riluzole extends the survival of ALS patients by only 3 months (Bensimon et al., 1994). The more recently approved Radicava (edaravone), which is a free radical scavenger, has a similarly modest impact on patient survival (Abe et al., 2017; Vu et al., 2020).Thus, identification of novel therapeutic targets is critical for this patient population.

Figure 2: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) symptoms and pathogenesis.

Patients presenting with ALS classically exhibit both (A) upper motor neuron (UMN) and (B) lower motor neuron (LMN) symptoms. These include spasticity (UMN) and muscle weakness and fasciculations (LMN). Thirty percent of patients display “bulbar” onset symptoms such as slurred speech, difficulty swallowing and facial weakness. A subset of patients also display concomitant symptoms of frontotemporal dementia (FTD), presenting with cognitive and behavior changes due to cortical degeneration. Ultimately, ALS patients succumb to respiratory insufficiency. (C) In ALS both upper and lower motor neurons display pathology. There are many proposed mechanisms, but aggregation of ALS-associated proteins, such as TDP-43, is considered central to disease onset. Studies employing SOD1 G93A and other mouse models have shown that expression of protein aggregates in neurons is key to disease onset, but that subsequent neuroinflammation drives disease progression. Microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes can sense and respond to protein aggregates by initiating programmed cell death (PCD) pathways. Activation of these cell signaling programs leads to secretion of neurotoxic factors (e.g. IL-1 family cytokines), gliosis and recruitment of peripheral immune cells. Glia can also mediate neuroprotective functions in the context of neurodegeneration. For example, microglia can bind TDP-43 using TREM2 to promote aggregate clearance and neuroprotection. Experimental depletion of microglia (or Trem2 −/−) worsen disease progression in TDP-43 murine models of ALS.

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of ALS onset and progression (Hardiman et al., 2017; Kwon and Koh, 2020b; Liu and Wang, 2017a). CNS-resident microglia and astrocytes, as well as peripheral immune cells, are highly activated at the level of the motor cortex, ventral horn and peripheral motor nerve (Lee et al., 2016; Philips and Robberecht, 2011; Sussmuth et al., 2008; Volpe and Nogueira-Machado, 2015). Gliosis in conjunction with an influx of peripheral immune cells into the CNS can predate ALS symptom onset, suggesting that these cells may impact disease onset and progression (Komine and Yamanaka, 2015; Liu and Wang, 2017). Depending on disease stage, the immune system may mediate both neuroprotective and deleterious functions (Komine and Yamanaka, 2015). For example, in a mouse model of ALS, microglia transcriptionally upregulate both neuroprotective and toxic factors (Chiu et al., 2013). Chemical depletion (PLX3397: a CSF1R and c-kit inhibitor) of microglia worsens disease recovery in a TDP-43 (ΔNLS) mouse model of ALS, indicating that microglia play neuroprotective roles in this setting (Clarke and Patani, 2020; Spiller et al., 2018). A recent study found that microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell 2 (TREM2) binds TDP-43 directly and contributed to aggregate clearance and neuroprotection in a murine ALS model (Xie et al., 2022). Collectively, this work suggests that the role of neuroinflammation in ALS progression is highly context specific—disease stage, genetic background and cell type are crucial considerations (Figure 2).

In 1993 genetic analysis of ALS families led to the identification of superoxide dismutase (SOD1), a reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger, as the first gene linked to significantly increased incidence of familial ALS (Rosen et al., 1993). Soon after, mouse models carrying transgenes of the identified human SOD1 mutations, G93A, G37R and G85R, were created to study the mechanisms of motor neuron death (Gurney et al., 1994). While SOD1 is ubiquitously expressed in all cell types, seminal work in the SOD1(G93A) model showed that expression of mutant SOD1 in motor neurons determines disease onset, but microglial mutant SOD1 expression potentiates disease progression (Boillée et al., 2006). Similar studies have implicated glial-dependent neuroinflammation in TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) mediated pathogenesis. TDP-43 is a versatile RNA/DNA binding protein deeply linked to ALS and FTD pathogenesis. Hyper-phosphorylated and ubiquitinated TDP-43 deposits are found in the majority (~97%) of sporadic ALS cases, and mutations in the TDP-43 gene underly 5–10% of familial cases. Several mouse models have been generated to study the role of this protein in mediating neuronal dysfunction and ALS and FTD (Walker et al., 2015; Wils et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2011). These models are characterized by progressive microgliosis and astrogliosis, which correlate with symptom onset and degree of neurologic impairment. Importantly, TDP-43 leads to both caspase-3 activation in neurons and caspase-1 activation and cytokine secretion in microglia and astrocytes (Wils et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2015). Mouse conditional knockout models of other ALS-risk alleles, such as TANK Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1, upstream regulator of necroptosis and interferon signaling), display cell-type dependent phenotypes. For example, knockout of TBK1 in motor neurons of SOD1 mice leads to accelerated disease-onset (Gerbino et al., 2020). However, pan-cell TBK1 knockout prolongs lifespan in these mice, suggesting TBK1 loss in glial populations may dampen neuroinflammation. However, further studies are required to determine which cell-type specific loss of TBK1 ameliorates disease. (Gerbino et al., 2020).

Collective learnings from cellular and mouse models suggests that ALS-associated genes and pathways can uniquely affect neuronal and non-neuronal cells to impact disease progression (Figure 2). Many of the PCD pathways discussed in this review occur in multiple cell types and can be engaged in both neurons and glia. For example, mutant SOD1 and TDP-43 stimulate both caspase-3 dependent apoptosis in motor neurons (Pasinelli et al., 2000), and engage inflammasome and caspase-1 signaling (key players in pyroptosis) in microglia and astrocytes (Deora et al., 2020; Johann et al., 2015; de Marco et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2013; Vogt et al., 2018; Wils et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2015). Mutant C9orf72 promotes cell death in motor neurons, whereas endogenous protein (lacking G2C4 repeat expansion) suppresses microglial neuroinflammation (Maor-Nof et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). Throughout this review, we will not only outline the contribution of cell death pathways to disease, but also highlight the importance of identifying the specific cell types that execute these programs. We also discuss gaps in knowledge regarding the role of specific inflammatory cell death mechanisms in ALS, and therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways in disease.

II. Apoptosis and ALS

Apoptotic signaling and the immune response

Just as a medical examiner must certify the manner of death following autopsy, so too must the immune system decide whether the destruction of a cell warrants further investigation. Apoptosis is often described as a “clean” and inconspicuous mode of cell death that does not induce local inflammation (Boada-Romero et al., 2020; Green et al., 2016; Heckmann et al., 2019).

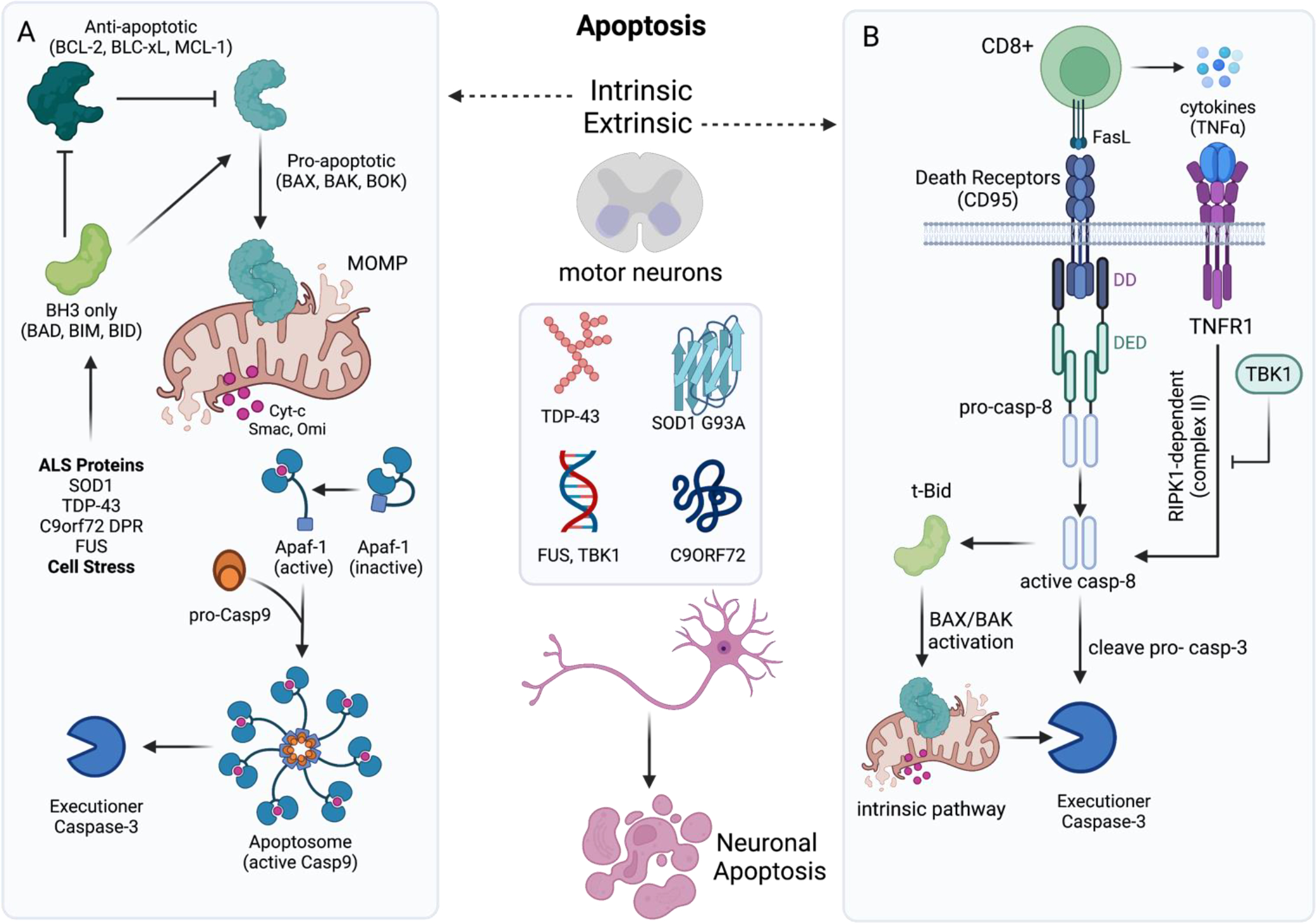

Apoptosis is mediated by the caspase family of cysteine proteases, which cleave hundreds of cellular targets, including the endonucleases that fragment nuclear DNA (Degterev et al., 2003; Julien and Wells, 2017; Yuan, 1993). There are two roads leading to downstream caspase activation and apoptosis—the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways (Figure 3). The intrinsic apoptotic pathway follows mitochondrial damage and release of cytochrome-c (cyt-c) from the inner mitochondrial membrane. Cyt-c complexes with Apaf-1 and caspase-9 to form an assembly called the “apoptosome” (Li et al., 1997). Active caspase-9 then cleaves and activates caspase-3, the final executioner of apoptosis (Kluck et al., 1997; Li et al., 1997; Yuan, 1993). Endoplasmic reticulum stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA damage, toxin exposure, viral infection, and growth factor deprivation can all stimulate intrinsic apoptosis (reviewed in Julien and Wells, 2017). For example, withdrawal of nerve growth factor (NGF) from cultured sympathetic neurons leads to mitochondrial damage, cyt-c release, and intrinsic apoptosis. Microinjection of a neutralizing anti-cyt-c mAb rescues cell death, confirming the importance of this mode of cell death to NGF-withdrawal (Deckwerth et al., 1996; Mesner et al., 1992; Neame et al., 1998). Other mitochondrial proteins release from the intermembrane space, such as Smac/DIABLO and Omi/HtRA2, potentiate apoptosis by blocking the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family. By releasing negative regulation of caspases, these proteins potentiate apoptotic cell death (Maas et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2004; Vucic et al., 2002). Mitochondrial stress can also lead to phosphorylation of eIF12a and induction of ATF4 transcription. ATF4 regulates the integrated stress response pathway (ISR), which upregulates apoptotic factors (e.g. PUMA, caspases) and suppresses anti-apoptotic molecules (Galehdar et al., 2010). ATF4 activation in neurons has been linked to cell death and neurodegeneration (Baleriola et al., 2014; Galehdar et al., 2010). Recent work showed that following mitochondrial damage, the mitochondrial proteins OMA1 and DELE1 activate an HR1-eIF2a axis that induces ATF4-mediated ISR (Fessler et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020). Thus other mitochondrial molecules beyond cyt-c, such as Smac and Omi, also play roles in amplifying intrinsic apoptotic death.

Figure 3: Evidence for activation of apoptosis in ALS.

Studies using in vitro and in vivo approaches have found that ALS-associated proteins (e.g. TDP-43, mSOD1, toxic C9ORF72 dipeptide repeat proteins) and mutations in fused-in-sarcoma (FUS) can cause activation of (A) intrinsic apoptosis in neurons. Intrinsic apoptosis begins with cellular stress that activates pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins. BH3 only proteins such as BIM and BID, sequester anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins and promote oligomerization of pro-apoptotic family members (e.g. BAX) in mitochondrial membrane. Following mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) mediated by BAX and BAK, cytochrome-c (cyt-c) is released from the intermembrane space into the cytosol. There cyt-c binds and activates Apaf-1, allowing for oligomerization and recruitment of pro-caspase-9 via homotypic CARD-CARD interactions. The apoptosome (cyt-c, Apaf-1, active caspase-9) cleaves executioner caspases to mediate apoptosis. (B) Infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the spinal cord, or mutations in TBK1 can sensitize neurons to extrinsic apoptosis. This mode of cell death is triggered by ligation of a death receptor (TNFR1, Fas, or TRAIL-R1/2), and can lead to apoptosis, necroptosis, or cell survival. Following CD95 ligation (by FasL), CD95 binds FADD using death domains (DD). FADD then recurits caspase-8 via death effector domain (DED) interactions, and assembles a caspase-activation platform called the DISC. This platform leads to caspase-8 activation and thus engages the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Caspase-8 can also process Bid into t-Bid, which then engages the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway of apoptosis. Upon ligation to TNF, TNFR1 recruits the adaptor protein TRADD and RIPK1, which in turn mobilizes additional partners, such as the ubiquitin ligases TRAF2 and cIAP1/2 to form complex I. When RIPK1 is deubiquitinated it allows for release of complex 1, which can then bind FADD and caspase-8 (complex II). This complex can induce apoptosis, or necroptosis in situations where FADD/caspase-8 are inhibited. TBK1 restrains TNFR signaling and downstream RIPK1-dependent apoptosis (RDA). Mutations in TBK1 can lead to loss of this inhibition and enhanced caspase-8 activation.

Extrinsic apoptosis occurs following a ligand (e.g. FasL) binding to a death-associated member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family (e.g. Fas) on the plasma membrane. Receptor activation induces a cascade that leads to the intracellular recruitment and activation of the initiator caspase-8 (Brunner et al., 1995). Caspase-8 then cleaves caspase-3 leading to downstream apoptosis. Crosstalk exists between the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. For example, caspase-8 can cleave the pro-apoptotic BH3 protein BID, which activates the effector proteins BAX and BAK (reviewed in Czabotar et al., 2014; Kalkavan and Green, 2018) to cause mitochondrial outer-membrane permeabilization (MOMP) (Figure 3). Upon MOMP, proteins like cytochrome-c (and other pro-apoptotic molecules such as SMAC) are released into the cytosol to further drive intrinsic apoptosis/caspase-3 activation (Du et al., 2000; Kluck et al., 1997; Muñoz-Pinedo et al., 2006). Both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways have been implicated in CNS injury and dysfunction (D’Amelio et al., 2010; Eldadah and Faden, 2000).

The “immunologically silent” nature of apoptosis is often attributed to its capacity to contain intracellular components of the cell during death, preventing the release of proinflammatory DAMPs, alarmins and cytokines (Bertheloot et al., 2021) (Figure 1). Classically, apoptotic cells release “find me” (e.g. ATP, UTP, LPC and S1P) and “eat me” signals to recruit phagocytic myeloid immune cells and promote clearance (Hamon et al., 2000; reviewed in Ravichandran, 2010; Reddien and Horvitz, 2000; Wu and Horvitz, 1998). For example, a hallmark of apoptotic death is the caspase-3 mediated activation of Xkr8 scramblase. This scramblase flips the membrane lipid phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane; PS exposure allows for identification of apoptotic cells by phagocytes (Asano et al., 2004; Krahling et al., 1999; Ravichandran, 2010). The T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule 4 (Tim4), expressed on macrophages can bind PS to promote the phagocytic engulfment of the dying/dead cell and subsequent degradation in a process known as efferocytosis (reviewed in Boada-Romero et al., 2020). Efferocytosis is LC3-dependent and is as an important component of immune silencing (Green et al., 2016). PS-binding and LC3-associated phagocytosis alters the macrophage transcriptional response, promoting expression and secretion of the anti-inflammatory factors TGF-β and IL-10 (Fadok et al., 1998; Szondy et al., 2017).

CNS-resident microglia can recognize PS on the surface of apoptotic neurons using the vitronectin or MERTK receptors; PS-receptor binding leads to microglial phagocytosis of viable neurons (Neher et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2001). This mechanism of PS recognition is important for microglial engulfment of not only apoptotic neurons but also virally infected neurons in the CNS (Tufail et al., 2017). In cultured neurons, ROS generation (via H2O2 treatment) induces reversible PS exposure, which can be recovered and internalized in the absence of microglia (Brown and Neher, 2012; Nomura et al., 2017). However, stressed neurons co-cultured with microglia are promptly phagocytosed prior to PS-recovery. Interestingly, knockout of the ALS-associated gene progranulin (PGRN) in C. elegans and mice led to enhanced rates of neuronal clearance via macrophage and microglial phagocytosis (Kao et al., 2011). Further, PGRN mutation in mice results in an age-dependent increase in phagocytic microglia, which may relate to elevated neuronal apoptosis that occurs due to aging (Yin et al., 2010). However, the implications of these findings with respect to the role of apoptosis in ALS progression are still unclear.

Rather than just simply sequestering intracellular contents, recent work has shown that apoptosis may inhibit inflammation more directly. Medina and colleagues found that apoptotic lymphocytes and macrophages release anti-inflammatory metabolites while preserving their plasma membrane integrity (Medina et al., 2020). This metabolic “secretome” relied upon caspase-dependent activation of pannexin-1 (PANX1) channels. Metabolites (e.g. spermidine, AMP and Creatine) leaked via PANX1 channels induced immunosuppressive and tissue repair gene programs in neighboring cells. When given exogenously, a cocktail of apoptotic metabolites reduced disease severity in mouse models of inflammatory arthritis and lung-graft rejection (Medina et al., 2020). Tanzer et al. (2020) identified a specific “secretome” signature that is dominated by release of ectodomain portions of cell surface proteins (Tanzer et al., 2020). Receptor shedding may have an anti-inflammatory effect through the generation of soluble decoy receptors. Ultimately, more research is needed to define the extent to which neurons have a unique apoptotic “secretome” and its effects on immune cells and other neurons.

Several apoptotic mechanisms carefully work to silence immune activation and ensure that cells “go quietly.” Nonetheless, inappropriate activation of apoptosis contributes to loss of motor neurons in ALS. The evidence for the activation of this PCD pathway in patient samples and ALS mouse models is detailed below.

The role of apoptosis in ALS

Apoptosis was first implicated as a driver of ALS following detection of caspase activation in SOD1 mutant mice and human patient samples (Table 1). Pasinelli and colleagues found elevated caspase-3 expression and activation in SOD1 G37R, G85R and G93A neurons and glial cells; cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity preceded symptom onset and increased with age and disease severity (Pasinelli et al., 2000). A concomitant report found that SOD1 (G85R) caused neuronal p53 transcription and increased expression of pro-apoptotic BCL2 family members, Bcl-x and Bax (González de Aguilar et al., 2000). A later report also found that overexpression of TDP-43, a pathologic hallmark of ALS, also evoked a p53 transcriptional response in neurons (Vogt et al., 2018). Subsequent work showed that mutated SOD1 binds and depletes the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 from spinal cord mitochondria, allowing for induction of intrinsic apoptosis (Pasinelli et al., 2004). Several other studies have also detected aberrations in the BCL-2 family, such as increased levels of BAX and BIM (pro-apoptotic) in patient spinal cord (Ekegren et al., 1999; Hetz et al., 2007). Importantly, genetic knockout of pro-apoptotic BCL2 family members (BIM, BAX, BAK) or pharmacologic caspase inhibition improves disease symptoms and extends lifespan in SOD1 transgenic mice. These studies firmly implicate transcriptional regulators (p53), upstream inducers (BCL-2 family) and downstream executioners (caspase-3) of intrinsic apoptosis in mediating mutant SOD1-driven pathology (Figure 3).

Table 1:

Selected evidence for programmed cell death mechanisms in ALS

| PCD Pathway | ALS Model / Methodology | Result Summary | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | SOD1 G93A, G85R, G37R | Caspase-3 activation preceded symptom onset and increased with disease severity in ALS mice | Pasinelli et al., 2000 |

| SOD1 G85R, G93A | Mutant SOD1 causes pro-apoptotic dysregulation of BCL-2 family in motor neurons | González de Aguilar et al., 2000; Ekegren et al., 1999; Hetz et al., 2007; Pasinelli et al., 2004 | |

| SOD1 G93A and neuron T-cell co-cultures | CD8+ T cells can induce extrinsic apoptosis in cultured neurons; CD8+ depletion rescues SOD1 mice | Coque et al., 2019 | |

| AAV-PR50 mouse model (FTD/ALS) | The c9orf72 DPR, PR-50, induces p53 and caspase-3 dependent neuronal death | Maor-Nof et al., 2021 | |

| Pyroptosis | Human CSF samples | Elevated IL-1 family cytokines in ALS patient CSF and spinal cord samples | Maier et al., 2015; McCauley and Baloh, 2019; Meissner et al., 2010 |

| SOD1 G93A, G85R, G37R mice | Caspase-1 activation in SOD1 spinal cords | Pasinelli et al., 2000 | |

| SOD1 G93A mouse | Inhibition or genetic KO of caspase-1 delays disease progression | Maier et al., 2015; Meissner et al., 2010 | |

| Primary mouse microglia cultures and neuronal co-cultures | SOD1 and TDP-43 activate microglial NLRP3 inflammasomes, which can kill cultured neurons | Deora et al., 2020; Gugliandolo et al., 2018; Meissner et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015 | |

| SOD1 G93A mice | Immunostaining reveals NLRP3/ASC present in microglia, astrocytes, skeletal muscle | Gugliandolo et al., 2018; Heitzer et al., 2017; Johann et al., 2015; Lehmann et al., 2018 | |

| Necroptosis | Patient genetics | Mutations in negative regulators of RIPK1 pathway, TBK1 and OPTN, are associated with ALS | (Cirulli et al., 2015; Freischmidt et al., 2017;Maruyama et al., 2010) |

| Optn −/−, SOD1 G93A mice | Knockout of Ripk1 rescues two mouse models of ALS. RIPK1 and MLKL activation are detected in human ALS spinal cord samples | Ito et al., 2016 | |

| Astrocyte-neuron co-culture | Astrocytes derived from individuals with sporadic ALS killed iPSC-derived motor neurons via necroptosis | Re et al., 2014 | |

| Astrocyte-neuron co-culture | Conditional KO of Ripk3 in neurons protects from Tg-SOD1 G93A astrocyte toxicity. SOD1 G93A Ripk3 −/− mice not protected from disease progression | Dermentzaki et al. 2019 | |

| SOD1 G93A and Optn −/− mice | Subset of microglia in the SOD1 G93A and Optn −/− models of ALS rely on RIPK1 signaling to boost neuroinflammation. | Mifflin et al., 2021 | |

| Ferroptosis | SOD1 G93A mice and human ALS samples | xCT antiporter expression is increased in microglia and regulates neuroinflammation in SOD1 G93A mice | Mesci et al., 2015 |

| Human ALS samples | Iron and ROS accumulation in patient spinal cords, iron chelation improves motor function | Moreau et al., 2018 | |

| SOD1 G93A mice | Transgenic overexpression of GPX4 increased motor performance and survival in the SOD1 G93A mouse model | Wang et al., 2020b |

There is also evidence to support a role for T-cell mediated apoptosis in disease progression. Studies using the SOD1 G93A mouse have showed an influx of CD8+ T cells in both spinal cord and sciatic nerve (Coque et al., 2019; Nardo et al., 2018; Rolfes et al., 2021). CD8+ T cells recognize antigen presented on major histocompatibility complex I (MHC I). Following binding of T cell receptor (TCR) to MHC I, these cells can release granules filled with perforin and granzyme to trigger apoptosis of the target cell. CD8+ T cells can also release FasL, which binds and clusters Fas receptors on the target cell plasma membrane to mediate extrinsic apoptosis. Coque et al., (2019) found that in vitro CD8+ T cells carrying SOD1 G93A mutations produce interferon-γ, which elicits the expression of the MHC-I complex in motoneurons. These activated T cells can attack MHCI positive neurons directly and cause apoptosis dependent on both FasL/CD95 and perforin/granzyme pathways (Figure 3). Depletion of CD8+ cells using anti-CD8 neutralizing antibodies delays disease progression in the SOD1 G93A mutant mouse (Coque et al., 2019). Very recent work has shown that mutations in SETX (which causes ALS4, a rare juvenile onset form of ALS), drives clonal CD8 T cell expansion in the periphery and infiltration into the spinal cord (Marazzi et al.). This work suggests that CD8-mediated neuronal killing may be a common feature of ALS, upstream of several common and rare ALS mutations (Table 1).

Fewer reports have explored apoptotic signaling in non-SOD1 genetic causes of ALS (Table 1). A recent study developed an in vitro RNA-seq and ATAC-seq platform to explore neuronal cell death in response to mutant c9orf72-driven neuropathology. Using this unbiased approach, it was uncovered that toxic dipeptide repeats (DPRs), transcribed from hexanucleotide repeats in the c9orf72 locus, caused p53 and capase-3 dependent cell death in vitro (Maor-Nof et al., 2021). Employing recently developed mouse and Drosophila models of c9orf72 DPR toxicity, they found that knockout of p53 or PUMA (a pro-apoptotic BCL2 family member) dampened neuronal loss and improved overall survival. Other work has found that mutations in ALS-risk genes, such as FUS and TBK1, lead to neuronal apoptosis (assessed by caspase-3 activation and TUNEL staining) in vitro and in mouse models (Suzuki and Matsuoka, 2015; Yu and Cleveland, 2018).These studies raise the possibility that apoptosis is central to ALS in multiple genetic contexts. Future work studying temporal activation of caspases in c9orf72, FUS and TDP-43 animal models, as well as in sporadic ALS patient samples, will shed light on this point.

Unlike apoptosis, necrosis has traditionally been viewed as an “accidental” cause of death (Green, 2016; Heckmann et al., 2019). Cellular trauma, exposure to high doses of toxins, or overwhelming shifts in osmotic gradient would cause “bursting” of the plasma membrane and release of intracellular contents. Over the last decade, elegant investigations have identified programmed necrotic mechanisms and pathways—pyroptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis (Figure 1). In contrast to apoptotic death, necrotic PCD leads to coordinated release DAMPs and cytokines that activate the immune system (Figure 1). Given that ALS is characterized by cell death and inflammation, whether necrotic PCD mechanisms contribute to disease progression is of intense translational interest. We review these mechanisms and their links to ALS in the subsequent sections.

III. Pyroptosis

Pyroptotic signaling and release of inflammatory mediators

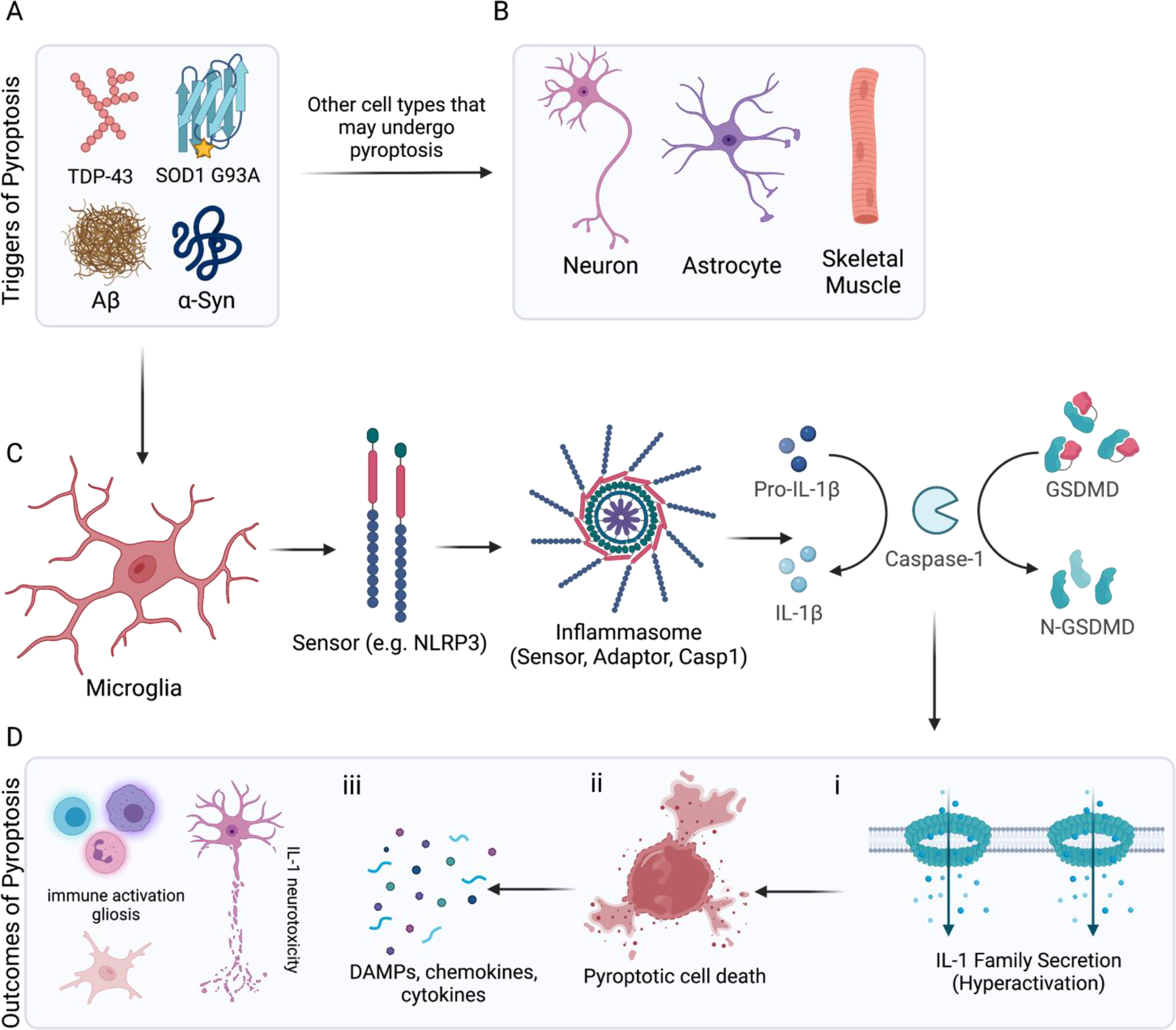

Cell signaling: Pyroptosis is a form of cell death that occurs downstream of inflammasome activation, classically in immune cells (Figure 4). The term “inflammasome” was coined in 2002 to describe a protein complex in the cytosol of immune cells that senses pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and DAMPs and responds by activating inflammatory caspases (Martinon et al., 2002). When “seed” molecules, such as NLRP3 or AIM2, bind PAMPs or DAMPs they oligomerize and recruit the adaptor apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC). The myriad mechanisms by which inflammasomes recognize microbial and damage-associated molecules is reviewed elsewhere (Broz and Dixit, 2016; Man et al., 2017; Martinon et al., 2002).

Figure 4: Signaling mechanisms and outcomes of pyroptosis in the ALS.

(A) Triggers of pyroptosis in the context of neurodegeneration include aggregated proteins such as TDP-43 and mutant SOD1 (ALS), as well as amyloid beta oligomers (AD) and fibrillar alpha-synuclein (PD). There is some evidence to suggest (B) neurons, astrocytes and skeletal muscles can undergo pyroptosis in the context of ALS. Most of the available evidence points to (C) microglia as the chief cells responding to aggregated protein species by engaging pyroptosis. Neurodegeneration associated molecules are detected by sensor molecules (e.g. NLRP3), which recruit and oligomerize adaptor proteins (e.g. ASC). Adaptors such as ASC and pyrin contain CARD domains that can recruit caspase-1 as part of the inflammasome complex. Active caspase-1 can process IL-1 family cytokines and cleave the linker region of full-length GSDMD (Asp 275). (D) When released, N-terminal GSDMD undergoes a conformational change enabling binding to acidic lipid residues and pore formation in the cellular membranes. (i) If these pores form in the plasma membrane of a living cell they act as conduits for IL-1 release and mediate a “hyperactivated” phenotype. (ii) If enough GSDMD pores accumulate in the plasma membrane, cellular swelling and overt pyroptosis can occur. iii) This leads to release of intracellular contents and serves to (iv) recruit peripheral immune cells and activate microglia and astrocytes. High levels of IL-1 release can contribute to neurotoxicity and may exacerbate neuronal injury.

Following adaptor oligomerization, inflammasomes act as scaffolding to recruit and activate caspase-1 (Boucher et al., 2018; Broz and Monack, 2013). Cleaved caspase-1 can then process pro-interleukin (IL)-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature forms (Figure 4). In 2015, several studies reported the identification of gasdermin-d (GSDMD) as a key executioner of cell death and regulator of cytokine release from macrophages (Kayagaki et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2015). Collectively, this work described how caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin-D (GSDMD) in a linker region separating the N and C-termini. Cleavage at this linker region allows the N-terminus to oligomerize, and form 215 Å - 310 Å pores in the plasma membrane through which IL-1 cytokines can efflux (Liu et al., 2016; Ruan et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2021) (Fig 4). GSDM-driven pore formation, release of IL-1 family cytokines and eventual cellular swelling and necrosis are collectively termed “pyroptosis” (Lieberman et al., 2019). Recent work has shown that in addition to IL-1 cytokines, small, neutral, or positively charged molecules (e.g. cytochrome-c) can pass directly through GSDMD pores (Xia et al., 2021). The full spectrum of molecules that can traverse GSDM pores is currently unexplored and may have profound effects on inflammation.

In immune cells, pyroptosis is characterized by the release of IL-1β and IL-18 (Kuida et al., 1995; Li et al., 1995). IL-1β is a potent inflammatory mediator, promoting vasodilation, immune cell extravasation and adaptive immunity (Li et al., 1995). IL-18 promotes interferon (IFN)-γ production in TH1 cells, NK cells and cytotoxic T cells, enhances the development of TH2 cells, promotes gut antimicrobial immunity, and local tissue inflammation (reviewed in Dinarello et al., 2013). Alarmins such as IL-1α and HMGB1, as well as other endogenous DAMPs (e.g. nuclear and mitochondrial DNA), are also released by pyroptotic cells following plasma membrane rupture (Dombrowski et al., 2011; Eigenbrod et al., 2008; Lamkanfi et al., 2010; Orzalli et al., 2021). Collectively, these molecules bind their cognate cytokine receptors (IL1 or IL18 receptors) or HMGB1 to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as toll-like receptors and RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation endproducts) on immune cells to promote chemotaxis, antigen presentation and inflammatory transcriptional profiles (e.g. NF-kB programs). NETosis—the process by which neutrophils expel their nuclear chromatin to trap pathogens and promote inflammation, is also found to be GSDMD-dependent (Sollberger et al., 2018). Lastly, studies have revealed that pyroptotic cells release active inflammasomes (i.e. NLRP3) and ASC specks into the extracellular microenvironment to potentiate inflammasome activation in other immune cells (Baroja-Mazo et al., 2014; Franklin et al., 2014). These studies are beginning to define a pyroptotic “secretome” that serves to initiate and amplify inflammation. Inhibition of specific secretome members may alter the immune response in vivo. For example, a recent study utilized proteomics to find that intracellular LPS induced the release of the DAMP galectin-1 from pyroptotic macrophages. Galectin-1-deficiency, or treatment with galectin-1-neutralizing antibodies, reduced inflammation and improved outcomes in a mouse model of LPS-induced sepsis (Russo et al., 2021).

The in vivo role of pyroptosis has been found to contribute to a variety of conditions, including Multiple Sclerosis (MS), neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD), as well as in peripheral tissues in anti-tumor immunity, inflammatory bowel disease, viral and parasite infections, sepsis (McKenzie et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021a). Recent evidence also points towards an important role for the AIM2 inflammasome, daspase-1 and GSDMD in regulating cell death in neurodevelopment (Lammert et al.,2021). There are many clues implicating “fiery” cell death as a central culprit driving neurodegeneration. Classically, pyroptotic death in monocytes promotes immune activation in the context of autoimmune disease and infection (Lieberman et al., 2019). Downstream of inflammasome assembly, innate immune cells engage caspase-1 to produce mature IL-1a, IL-1b and IL-18; these cytokines are then released through GSDMD pores and subsequent cellular necrosis ensues (Lieberman et al., 2019). Here we will examine the evidence and therapeutic strategies for targeting pyroptosis, in the context of ALS.

Evidence for pyroptosis in ALS

Given that chronic and progressive inflammation is a hallmark of ALS, it was hypothesized that pyroptosis may be involved in this disorder (McCauley and Baloh, 2019) (Table 1). Clinical studies have found pyroptotic “fingerprints” at the crime scene: elevated IL-1 family cytokines in samples of spinal cord and CSF from ALS patients (Maier et al., 2015; McCauley and Baloh, 2019; Meissner et al., 2010). Inflammasome assembly and cleaved caspase-1 have also been found via histology for a wide range of CNS diseases, including AD, PD, HD, MS and stroke (reviewed in Voet et al., 2019). While there is evidence from mouse models to implicate pyroptosis as a driver of ALS (Table 1), the upstream triggers, functional relevance and cell-types involved are less clear.

Early reports showed that cleaved caspase-1 was increased in spinal cord samples from SOD1 transgenic animals (containing human G93A, G85R and G37R mutations). This activation was detected several months prior to disease onset and induction of neuronal apoptosis (Pasinelli et al. 2000). Subsequent work has shown that total caspase-1 knockout or pharmacologic inhibition of caspase-1 delays disease onset in SOD1 transgenic mice, have not clarified this issue of cell-type specificity (Maier et al., 2015; Meissner et al., 2010). In these studies, caspase-1 activation was assessed by immunoblots of spinal cord lysates. However, the identity of the cells (i.e. neuronal vs. glial) expressing activated caspase-1 remains unclear.

Work in PD, AD and EAE models suggests that protein aggregates can activate microglial NLRP3 inflammasomes directly, driving downstream caspase-1 and IL-1 processing (Gordon et al., 2018; Heneka et al., 2013, 2018; McKenzie et al., 2018; Rui et al., 2021; Song et al., 2017; Voet et al., 2019). Supporting the notion that pyroptosis occurs chiefly in microglia, several studies have shown that SOD1 and TDP-43 protein aggregates induce NLRP3/ASC oligomerization and IL-1b secretion from mouse microglia in vitro (Deora et al., 2020; Gugliandolo et al., 2018; Meissner et al., 2010). Co-culture of TDP-43-treated microglia with motor neurons causes neuronal death (Zhao et al., 2015). This phenotype was dependent on microglial TLR4 and NLRP3 expression, suggesting that TDP-43 may activate an inflammatory cascade in microglia to drive non-cell autonomous neuronal death (Zhao et al., 2015).

Given that pyroptosis was discovered in peripheral monocytes, it is tempting to completely segregate this pathway to microglia in the CNS. However, the situation may be more complex (Fig 4B). Several studies that immunostained SOD1 G93A spinal cords found early increases in the levels of NLRP3 that did not colocalize with microglia (Gugliandolo et al., 2018; Heitzer et al., 2017; Johann et al., 2015; Lehmann et al., 2018). Using both the SOD1 G93A mouse model and patient samples, Johann et al. (2015) identified the cellular source of NLRP3 to be astrocytes rather than microglia (Johann et al., 2015). In subsequent studies, Johann and colleagues have suggested that inflammasome expression on skeletal muscle and in thalamic neurons may be contributing to motor and cognitive deficits found in ALS-FTD patients (Lehmann et al., 2018). In addition, other work has suggested that the NLRC4 and AIM2 inflammasomes are also increased in SOD1 G93A mice, though the tissue expression patterns and relevance of these inflammasomes to disease are unclear (Pasinelli et al., 1998). Several studies also indicate that neurons can express active inflammasome components (AIM2 and NLRP3) and undergo pyroptosis following exposure to TLR agonists, oxygen-glucose deprivation, or exogenous amyloid beta (Adamczak et al., 2014; Han et al., 2020; Pronin et al., 2019). Though these studies were able to colocalize inflammasomes with neuronal markers, these studies did not examine neuronal caspase-1 or GSDMD activity, use ALS-associated stimuli and were limited to in vitro assessment (Han et al., 2020).

Unexplored avenues linking pyroptosis to ALS

The investigation of pyroptosis in mediating ALS (and neurodegeneration more broadly) is limited by several factors. Though neuroinflammation is a common marker of all forms of ALS, currently the temporal and spatial expression of inflammasomes and caspase-1 has only been studied in the SOD1 G93A mouse model in vivo. Future studies examining expression of additional pyroptosis components (e.g. NLRP3, ASC, GSDMD) in c9orf72 and TDP-43 driven animal models and in ALS patient tissues may shed light on the relevance of this pathway to disease. Classically, complete knockouts (or chemical inhibitors) have been used to assess the role of pyroptosis in neurodegeneration. For example, deficiency in caspase-1 ameliorates disease progression in mouse models of PD and ALS (SOD1 G93A) (Gordon et al., 2018b; Maier et al., 2015; Meissner et al., 2010). Though informative, these studies do not shed light on which cell type is employing this cell death pathway. Coupling conditional knockout strategies (e.g. Cxc3r1 or Syn1a driven Cre expression) of pyroptosis components (e.g. NLRP3, ASC, GSDMD) with ALS disease models will give the field a more detailed understanding of how and where pyroptosis is activated in vivo. The molecular mechanisms leading to inflammasome activation also remains to be fully elucidated. It would be important to define whether specific ALS-associated proteins trigger NLRP3 or other intracellular inflammasome components at the structural level.

Recent work has shown that macrophages can possess active inflammasomes and GSDMD pores in the absence of overt necrotic cell death (i.e. pyroptosis). These “hyperactived” cells use GSDMD channels to secrete high levels of Il-1 family cytokines but maintain cellular viability (Evavold et al., 2018). Future work assessing whether neurodegeneration proteins (e.g. SOD1 and TDP-43) cause hyperactivation or pyroptotic death of glial cells, will add nuance to our understanding of how this pathway contributes to neurologic disease.

IV. Necroptosis

Necroptotic signaling and DAMP release

Necroptosis is another recently identified cell death pathway that has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases. While the caspase family of proteases drive apoptosis (caspase-8, caspase-3/7) and pyroptosis (caspase-1/11), necroptosis was originally identified as a caspase-independent form of cell death. Rather, the receptor interacting serine/threonine kinases (RIP kinases) control necroptosis (Fig 5). As in extrinsic apoptosis, necroptosis is classically initiated by ligation of death receptors, such as tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1). In vitro, death receptor ligation combined with caspase-inhibition induces the recruitment and deubiquitylation of RIPK1 (Degterev et al., 2005, 2008). RIPK1 is then autophosphorylated and can recruit RIPK3 via interactions between homotypic RHIM domains present on both proteins (Orozco et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). RIPK3 then oligomerizes and phosphorylates the pseudokinase Mixed Lineage Kinase-Like (MLKL) (Fig 4). Phosphorylated-MLKL, the executioner of necroptosis, translocates to the plasma membrane to induce membrane rupture and cell death (Murphy et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012) (Figure 5).

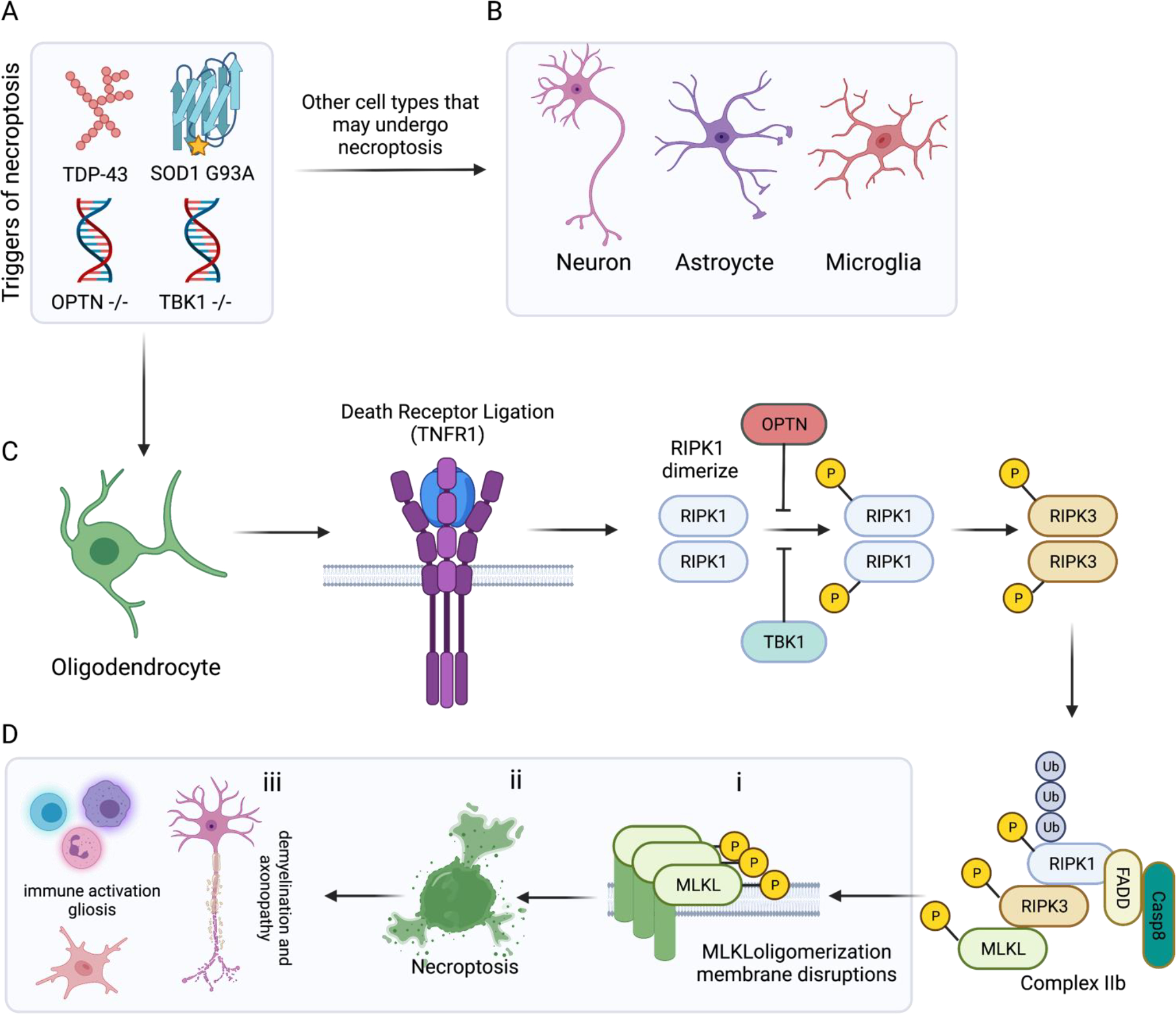

Figure 5: Necroptotic signaling mechanisms and outcomes in ALS.

(A) Triggers of necroptosis in the context of ALS include aggregated proteins such as TDP-43 and mutant SOD1 (ALS), as well as mutations in negative repressors of the RIPK1 pathway such as optineurin (OPTN) and TBK1. There is evidence to suggest (B) neurons, astrocytes and microglia undergo necroptosis in the context of ALS. However, the strongest evidence points to (C) oligodendrocytes as the chief cells executing necroptosis in ALS. Stimulation of TNFR1 by TNF promotes the formation of an intracellular signaling complex where the death domains (DD) of trimerized TNFR1 binds the DD-containing proteins: TRADD and receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1). TRADD helps to recruit a number of RIPK1 regulators, including OPTN and TBK1. In situations of caspase-8 down regulation or inhibition, RIPK1 is auto phosphorylated and dimerizes via its C-terminal death domain. This dimerization promotes RIPK3 activation and the subsequent formation of the necrosome (complex IIb) comprised of RIPK1, FADD, Casp8, RIPK3 and mixed-lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL). (D) This complex enables (i) p-MLKL to insert and oligomerize in plasma membrane and iii) execute overt necroptotic cell death. As in other forms of programmed necrosis, release of DAMPs and intracellular contents serves to recruit and activate peripheral immune cells and promote gliosis. In the case of necroptosis in oligodendrocytes, this leads to demyelination and perhaps contributing to the progressive axon loss observed in ALS.

Upstream engagement of the receptors TLR3 and TLR4, IFNAR, and ZBP1 can also result in necroptosis (Kaiser et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2016; Newton et al., 2016). Signaling through these receptors concomitantly activates inflammatory transcription factors (such as NF-κB and p38) and expression of the pro-survival gene CFLAR (FLIPL) (Yeh et al., 2000). FLIPL can form a heterodimer with caspase-8, blocking its ability to cleave caspase-3 (Pasparakis and Vandenabeele, 2015; Yuan et al., 2019b). Active caspase-8 can cleave and inactivate RIPK1 and RIPK3 and inhibit downstream MLKL-driven death. Thus, only in settings where the catalytic activity of caspase-8 is disrupted (via chemical inhibition or binding to FLIPL) can necroptosis ensue (Yuan et al., 2019). Caspase-8 inactivation may provide an important mechanism for necroptosis induction in the CNS diseases. Cortical tissue samples from MS patients showed reduced levels of the active caspase 8 subunit and correspondingly reduced caspase 8 activity (Ofengeim et al., 2015). The expression of FLIPL was also substantially elevated in MS samples (Ofengeim et al., 2015). In the CNS, FLIPL is expressed in many cell types including microglia, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, and mature oligodendrocytes (Zhang et al., 2014). Induction of this molecule (potentially downstream of NF-kB or p38) may be an important step in licensing necroptosis during disease.

There are several additional regulatory proteins that serve to repress RIPK1 function and block necroptosis. TBK1 phosphorylates and thereby inhibits RIPK1 autophosphorylation, while the M1 ubiquitin-binding protein optineurin (OPTN) negatively regulates RIPK1 activation while it is bound to death receptors (e.g. TNFR1) via TRADD (Nakazawa et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019) (Figure 5). Mutations causing haploinsufficiency of TBK1 are a major genetic cause of ALS and frontotemporal dementia, accounting for 10.8% of all cases in patients presenting with comorbid ALS and FTD (Cirulli et al., 2015; Freischmidt et al., 2017). Interestingly, mutations in OPTN lead to development of either hereditary glaucoma or ALS (Maruyama et al., 2010). In Asian populations, mutations in OPTN account for 4% of familial ALS cases, whereas this frequency is much lower in European populations at 1.5% (Maruyama et al., 2010; Toth and Atkin, 2018). Both Tbk1+/− and Optn−/− mice develop motor neuron disease that resembles ALS (Ito et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019). That mutations in two negative regulators RIPK1 activation leads to the development of ALS in humans and animal models, thereby linking necroptotic cell death to disease pathogenesis.

In contrast to the “natural causes” death associated with apoptosis, cells that undergo necroptosis are more akin to a car crash. Transcriptional programs induced by ligation of TLRs or IFNARs (e.g. p38 and NF-kB pathways) combined with p-MLKL mediated release of intracellular contents lead to high levels of inflammation. Many DAMPs, such as ATP, LDH, HMGB1, are released following necroptosis (reviewed in Kaczmarek et al., 2013). A recent study used a mass-spectrometry approach to characterize the “secretome” of necroptotic cells. They found that necroptosis induced a large release of lysosomal components, which were not detected in media containing apoptotic cells (Tanzer et al., 2020). The in vivo relevance of these specific secreted components has not yet been characterized. It will be interesting to assess how specific DAMPs affect innate and adaptive immune responses. Very recent work has shown that both GSDMD and MLKL rely on the action of another protein, Ninjurin-1 (NINJ1), to mediate ultimate plasma membrane rupture (PMR) and release of large intracellular molecules downstream of both pyroptosis and necroptosis (Kayagaki et al., 2021; Wang and Shao, 2021). DAMP-release is MLKL and NINJ1 dependent, indicating that pore formation and PMR is critical for recruiting immune cells (Hanson, 2016). Conformational change of this transmembrane molecule allows for PMR downstream of either GSDMD or p-MLKL pore formation. Thus, inhibition of Ninj1 prevents PMR, attenuates release of DAMPs like LDH and reduces local inflammation (Kayagaki et al., 2021).

The in vivo role of necroptosis has been proposed to contribute to a variety of conditions, including stroke, atherosclerosis, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and certain malignancies (Hanson, 2016; Heckmann et al., 2019; Kaczmarek et al., 2013). Regarding the role of necroptosis in neurodegeneration, several studies have implicated RIPK1 signaling in ALS, PD, AD and multiple sclerosis (MS) (Heckmann et al., 2019; Iannielli et al., 2018; Morrice et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2019). In the following sections we will examine the evidence and therapeutic rationale for targeting necroptosis in the setting of ALS.

Necroptotic molecules driving death and inflammation in ALS

The necroptosis pathway is brutal; during ALS progression no tissue or cell type is left unaffected. Current evidence suggests that necroptosis can detriment motor neuron health in several ways: by i) driving oligodendrocyte death and axonal demyelination ii) promoting cell autonomous neuronal death via p-MLKL membrane disruption iii) enhancing neuroinflammatory transcriptional programs in microglia (Figure 5) (Table 1).

Axonal attack

Axonal degeneration that precedes pathology at the cell body is commonly observed in patients suffering from ALS, MS, AD and PD (Conforti et al., 2014). In ALS, axons undergo ‘Wallerian- like’ degeneration, which is an axonopathy that resembles the “dying back” of processes seen after nerve transection (Conforti et al., 2014). Motor neurons, which have the longest axons of any neurons in the body, are especially susceptible to attack. Growing evidence suggests that axonal degeneration in ALS begins before the onset of clinical motor symptoms and is driven by oligodendrocyte dysfunction (Zhou et al., 2017).

Necroptosis was first implicated in ALS pathogenesis by Ito and colleagues (2016), where they demonstrated RIPK1-dependent axonal loss in Optn deficient mice (Ito et al., 2016). OPTN encodes a ubiquitin-binding protein that inhibits RIPK1; mutations in this gene are found in a small subset of ALS patients (Maruyama et al., 2010b). Optn knockout mice exhibited swollen large-diameter axons, reductions in the total number of motor axons in ventrolateral white matter and abnormal myelination patterns that preceded the loss of motor neuron soma (Ito et al., 2016). Conditional ablation of Optn in oligodendrocytes sensitizes these cells to TNF-induced necroptosis, and phenocopies the Wallerian-like degeneration seen in total Optn −/− mice. Necroptosis of Optn −/− oligodendrocytes can be rescued by pharmacologic Ripk1 inhibition (Nec-1s) or kinase dead mutations in Ripk1 or Ripk3 (Ito et al., 2016). Thus, the loss of Optn induces necroptosis in oligodendrocytes to mediate axonopathy.

Oligodendrocyte cell death has also been described in the SOD1 G93A mouse model, prior to disease onset (Kang et al., 2013). Reduced numbers and dysfunctional oligodendrocytes were also detected in spinal cord and motor cortex of human ALS patients (Kang et al., 2013). Ito and colleagues found that chemical RIPK1 inhibition or RIPK3 knockout restored myelination defects in SOD1 G93A mice and delayed onset of motor behavior defects. Finally, increased levels of phosphorylated RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL were detected in sporadic ALS patient spinal cords– though the cell type expressing these necroptotic molecules was not identified (Ito et al., 2016). Parallel findings in the cuprizone model of MS highlight the role of necroptosis in mediating degeneration of oligodendrocytes and non-cell-autonomous axon loss in neurons (Ito et al., 2016; Ofengeim et al., 2015).

Bodily harm

Necroptosis may also contribute more directly to neuronal cell death. In a humanized co-culture ALS model, astrocytes derived from individuals with sporadic ALS (sALS astrocytes) killed iPSC-derived motor neurons via activation of neuronal necroptosis (Re et al., 2014). In this in vitro system, inhibition of motor neuron RIPK1 by lentiviral shRNA transduction, or Nec-1 treatment, reduced sALS astrocyte-induced cell death (Re et al., 2014). A subsequent study found that conditional deletion of Ripk3 in cultured mouse motor neurons also protected them from SOD1G93A astrocyte induced neurotoxicity (Dermentzaki et al. 2019). However, Ripk3 knockout in the SOD1 G93A background failed to provide survival, behavioral or neuropathological improvement (Dermentzaki et al. 2019). Thus, the benefit of Ripk3 and necroptotic silencing in vivo remains unclear.

Though there is less evidence that neuronal necroptosis contributes to ALS, it is an area that deserves more attention. Prior work has found that acidosis can activate necroptosis in cultured neurons, and that both necroptosis and apoptosis are implicated in neuronal death following cerebral ischemia (Naito et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). A recent report has found that in aged mice, Ripk1 and p-Mlkl levels are increased in cortical and hippocampal neurons relative to young controls (Thadathil et al., 2021). Ripk1 inhibition (using nec-1s) and Mlkl knockout mice were protective against age-induced neuroinflammation and cell death. Interestingly, necroptotic molecules were detected only in the neuronal soma and not in axonal processes (Thadathil et al., 2021). Thus, necroptosis of oligodendrocytes may mediate an early axonal dysfunction in ALS, which may be followed by a delayed necroptosis at the level of the neuronal cell body. Future work using neuron specific (e.g. Syn1a) conditional knockouts of Ripk1, Ripk3 and Mlkl may elucidate the role of necroptosis in mediating cell-autonomous death in preclinical ALS models.

Inflammatory evidence

In addition to initiating necroptotic death, RIPK1 can also alter innate immune signaling and promote inflammatory transcriptional programs in immune cells (Yuan et al., 2019). Studies examining mouse models of AD have elucidated a role for microglial RIPK1 in increasing neuroinflammation, which is independent of p-MLKL and overt necroptotic death (Ofengeim et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Optn −/− mouse show an increase in activated microglia in the mouse spinal cord (Ito et al., 2016). RNA-sequencing analysis of these Optn −/− microglia revealed a module of approximately 1,300 genes — enriched in pro-inflammatory microglial markers such as CD14 and CD86 — that were differentially expressed compared to wild-type cells. This inflammatory signature was Ripk1-dependent and could be reversed by nec-1s treatment (Ofengeim et al., 2017). Following this analysis, a recent study identified a subset of microglia in the SOD1(G93A) and Optn −/− models of ALS that rely on RIPK1 signaling. These RIPK1-Regulated Inflammatory Microglia (RRIMs) have increased TNFa and NF-kB signaling and express pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1a (Mifflin et al., 2021). RRIM transcription is dampened by nec-1s treatment and is distinct from the classic disease associated microglia (DAMs) (Mifflin et al., 2021). How RRIMs and DAMs cooperate to mediate motor neuron cell death is likely a rich area of future investigation.

Unanswered questions and limitations

Several recent reports have called into question the role of necroptosis in mediating ALS progression (Chevin and Sébire, 2021). Two independent groups have recently found that Ripk1 or Mlkl knockout did not affect disease onset, motor symptoms, neuroinflammation or survival in SOD1 G93A mutant mice (Dominguez et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020, 2021b). These studies contradict prior work implicating RIPK1 and necroptosis as central mediators of motor neuron loss and neuroinflammation in SOD1 G93A mice (Ito et al., 2016; Mifflin et al., 2021; Re et al., 2014). Adding to the confusion, neither of the recent studies detected appreciable accumulation of RIPK1, RIPK3 or p-MLKL in human ALS or mouse SOD1 G93A spinal cords (Dominguez et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020, 2021b). The discrepancies between these reports are unclear, though it may be due to use of different antibody reagents, immunolabelling protocols or variable levels of perfusion to remove circulating blood cells, which are rich in necroptotic markers (Chevin and Sébire, 2021; Nakazawa et al., 2018). Given that RIPK1 inhibitors are advancing to phase II trials in human ALS patients, elucidating the role of this pathway in disease progression is paramount. Future studies assessing the role of necroptosis in other ALS disease models (e.g. C9ORF72 mutation), coupled with consistent experimental conditions, reporting of antibody reagents, and genetic backgrounds of knockout transgenic mice will shed light on this important issue.

V. Ferroptosis in ALS

Ferroptosis is a necrotic form of PCD, distinct from pyroptosis or necroptosis (Dixon, 2017). Specifically, it is an iron-dependent, oxidative cell death mechanism first described by Dixon et al. (2012). While the term “ferroptosis” was coined in 2012, similar processes have been observed years earlier in conditions where glutathione metabolism is disrupted (Armenta and Dixon, 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). Ferroptosis is triggered by inactivation of the system xc− cystine/glutamate antiporter (xCT), leading to depletion of intracellular glutathione and downstream ROS elevation (Dixon et al., 2012). The xCT antiporter is highly expressed on activated microglia, and xCT levels were increased in both spinal cord and isolated microglia from mutant SOD1 ALS transgenic mice (Mesci et al., 2015). Expression of xCT was also detectable in spinal cord post-mortem tissues of patients with ALS, which correlated with high levels of neuroinflammation. In ALS mice, xCT deletion led to decreased production of pro-inflammatory microglial factors nitric oxide, TNFα and IL6. This work suggests that increased ferroptosis (via genetic knockout of xCT) may serve to limit microglial inflammation (Mesci et al., 2015). In SOD1 G93A mice, xCT deletion accelerated disease onset, but slowed progression and increased overall survival of motor neurons (Mesci et al., 2015).

In vitro, ferroptosis can also be activated by chemical or genetic inhibition of the glutathione-dependent lipid hydroperoxidase GPX4 (reviewed in Cao and Dixon, 2016; Hirschhorn and Stockwell, 2019). Glutathione depletion or GPX4 inhibition ultimately leads to the iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides which kill the cell via uncontrolled lipid peroxidation (Cao and Dixon, 2016). Accordingly, ferroptosis is dependent on expression of ACSL4 and LPCAT3—the enzymes that generate the membrane lipids susceptible to peroxidation (Doll et al., 2017). Unlike the pore-forming molecules in pyroptosis or necroptosis, the executioner of ferroptosis is overwhelming ROS-driven lipid peroxidation causing cell failure and membrane rupture. There have been some reports implicating iron accumulation and ferroptosis in neurologic disease and ALS (Moreau et al., 2018; Rao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b). For example, Wang and coworkers found that transgenic overexpression of GPX4 increased motor performance and survival in the SOD1 G93A mouse model (Wang et al., 2021b). Further, edaravone (an ROS scavenger approved for ALS-treatment) reduces ferroptosis in cultured cells, protecting against both xCT and GPX4 inactivation (Homma et al., 2019). How ferroptosis in motor neurons or glial cells contributes to disease progression remains unclear. Recent work suggests that ferroptotic motor neuron death may be contributing to disease (Wang et al., 2021b), while earlier studies suggest that ferroptosis may also limit microglial neuroinflammation later in disease progression (Mesci et al., 2015). The role of this PCD pathway in different disease phases and cell-types in the CNS has yet to be adequately interrogated.

This Review has focused on the role of apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis in driving motor neuron death and inflammation ALS. Going forward, the precise signaling, immunologic consequences and cell-specific roles of ferroptosis (reviewed in Armenta and Dixon, 2020; Dixon, 2017) will be exciting to study in the context of ALS and neurologic disease.

VI. New leads: Potential therapeutic strategies targeting programmed cell death and inflammation in ALS

Caspase inhibition as a therapeutic strategy

There is considerable evidence suggesting that caspase activity promotes cell death and inflammation in mouse models of ALS and neurodegeneration (Eldadah and Faden, 2000; Hartmann et al., 2000; Inoue, 2003; Li et al., 2000; Maor-Nof et al., 2021; McKenzie et al., 2018; Pasinelli et al., 2000). That caspase-1 and caspase-3 regulate distinct cell death pathways (pyroptosis and apoptosis, respectively), suggests that a pan-caspase inhibition strategy may have clinical benefit. For example, the administration of pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK delayed onset and mortality in SOD1 G93A mice (Li et al., 2000). Similarly, administration of recombinant XIAP (a mammalian protein blocking caspase−3, −7, −9) also slowed disease progression (Inoue, 2003).

While the use of caspase inhibitors has contributed to a basic understanding of cell death and inflammation, many of these compounds have failed to progress to clinical trials. This is due to several factors, including an adverse safety profile, poor pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties, low target specificity and selectivity within the caspase family (Linton, 2005; MacKenzie et al., 2010). Efforts to target individual caspase family members have failed both in vitro and in preclinical contexts (Dhani et al., 2021). For these reasons, current studies using caspase inhibitors to treat neurologic disease have focused on the animal models rather than clinical trial data. Despite the central role of caspases in regulating neuronal demise, elegant work in innate immunology and cell death have revealed alternative therapeutic strategies. Several of these targets are currently being pursued in clinical trials for the treatment of ALS.

Targeting Apoptosis

Recently, a randomized double-blind trial showed that the combination of Sodium Phenylbuturate and Taurursodiol (PB-TURSO) slowed motor decline in ALS patients, as measured by the clinical ALSFRS-R score (Paganoni et al., 2020). Though the precise mechanism of action is unclear, Taurursodiol exerts anti-apoptotic properties in vitro by blocking the translocation of the pro-apoptotic BCL2 family-member BAX to mitochondrial membranes (Paganoni et al., 2020). Sodium phenylbutrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reduces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress which is upstream of apoptosis. ER stress has been shown to promote BAX-translocation, leading to calcium overload, caspase-activation and apoptosis (Szegezdi et al., 2006). While targeting caspase-3 may be pharmacologically off limits, drug combinations (e.g. PB-TURSO) able to alter upstream mediators of apoptosis may attenuate disease progression.

Targeting Pyroptosis

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in preclinical models of ALS, AD, PD, HD, MS and stroke (Franke et al., 2021; Heneka et al., 2013; Inoue and Shinohara, 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Zahid et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2013). Inhibitors of NLRP3 are advancing into clinical trials for treatment of peripheral autoimmune conditions, such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, liver and lung fibrosis, gout, and COVID-19 (Zahid et al., 2019). To date, NLRP3 inhibitors have not been tested in patients with neurodegenerative disease. However, several companies (e.g. NodThera, Inflazome, Ventus Therapeutics, Genentech, Novartis) are developing molecules that can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). As these molecules progress through phase I testing, it will be important to plan future trials evaluating efficacy in patients suffering from neurologic illness.

GSDMD activation downstream of inflammasome signaling leads to release of Il-1 family cytokines and pyroptosis. In theory, inhibition of GSDMD would block both cytokine and DAMP release downstream of NLRP3 or other inflammasomes. Recently, several groups have discovered GSDMD inhibitors (Hu et al., 2020; Humphries et al., 2020; Rathkey et al., 2018). All these compounds—disulfiram, dimethyl-fumarate (DMF) and necrosulfonamide (NSA)—are FDA approved for other indications and have excellent safety profiles. One such molecule, DMF also targets Nrf2 pathway and is currently used to treat MS. DMF reduces GSDMD activation and slows disease progression in the EAE mouse model of MS (Humphries et al., 2020). Whether these molecules have efficacy in preclinical ALS models is currently untested. Further, these molecules are non-selective cysteine reactive compounds that have many targets in vivo. For example, NSA blocks GSDMD but also targets the pore-forming molecule MLKL (Rathkey et al., 2018; Samson et al., 2020). Strategies that selectively target GSDMD are in their infancy but may represent exciting new avenues for patients suffering from neurologic disease.

Targeting Necroptosis

Genetic knockout or pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 has produced neuroprotective outcomes in some preclinical mouse models of ALS (SOD1 G93A and Optn −/−). The BBB penetrant RIPK1 inhibitor, DNL747 (Denali/Sanofi), has progressed through phase I trials in ALS patients. A modified successor compound, DNL788, is currently being tested in a phase II HIMALAYA trial. Given the controversy surrounding the preclinical efficacy of RIPK inhibition in mouse models, results in these trials may have definitive implications for the utility of targeting necroptosis in neurodegenerative disease.

Conclusion: open questions

Studies mapping the contribution of programmed necrotic mechanisms and subsequent immune activation to neurodegenerative diseases including ALS are still in their infancy. Many questions remain regarding the cell types involved, precise signaling mechanisms and whether inhibition of these pathways can alter disease progression.

Focusing on ALS, we have highlighted evidence implicating these PCD pathways in disease pathophysiology. However, almost no studies have examined whether multiple pathways are concurrently activated in the same cell, and the extent to which these mechanisms are compensatory in the CNS. For example, recent work has shown that a delicate balance exists between apoptosis and pyroptosis in peripheral immune cells. In macrophages that are deficient in GSDMD (the executioner of pyroptosis), inflammatory caspase-1 can activate caspase-3 and lead to apoptosis (Tsuchiya et al., 2019). Other work has shown that in pyroptotic cells, activated GSDMD can puncture mitochondrial membranes, causing release of mtDNA, cyt-c and apoptosis (Taabazuing et al., 2017; Torre-Minguela et al., 2021). Proteases such as caspase-8 exert control over multiple cell death pathways—negatively regulating necroptosis, promoting caspase-3 processing and apoptosis, and cleaving GSDMD to release its pyroptotic N-terminal domain (Degterev et al., 2003; Demarco et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2019).

How is this cell death crosstalk preserved in glia and motor neurons? Can one pathway compensate for another downstream of challenge with an ALS-associated protein? Would therapeutic strategies need to block multiple PCD signaling nodes to spare a motor neuron? Future studies interrogating multiple cell death pathways in a cell-type specific manner may start to address these issues. Recent work has shown that ALS-associated proteins like TDP-43 can engage innate immune signaling, such as the cGAS-STING pathway, in neurons and glia (Yu et al., 2020). How do these innate immune molecules (e.g. cGAS-STING, MAVs) influence cell death decisions and promote neuroinflammation? Do they sit upstream or downstream of PCD mechanisms? Recent advances in generating iPSC-derived neurons and glial cells, as well as traditional conditional knockout approaches, are helpful tools to dissect this complicated biology.

Characterizing the immunologic sequelae of different cell death pathways in the CNS is another exciting frontier. What does a dying neuron release, and how are these products sensed by the immune system? Do pyroptotic, necroptotic or ferroptotic cells have distinct CNS “secretomes”? These questions are of basic and translational interest. The types of molecules released downstream of PCD induction may play important biological roles in signaling to the immune system (i.e. DAMPs and alarmins) or in promoting neurodegeneration. Spread of aggregated proteins, such as alpha-synuclein and TDP-43, are hallmarks of neurodegenerative disease. The mechanisms by which these aggregates traverse the CNS are still poorly understood. Could activation of pore-forming molecules (e.g. GSDMs and MLKL) and induction of necrotic PCD amplify the spread of these protein species from dying to healthy neurons? Future work using cell death deficient animals and examining distribution and burden of TDP-43 or other protein aggregates (e.g., alpha-synuclein or tau) in models of neurodegeneration may shed light on this important point. Studies constructing molecular “fingerprints” for different cell death pathways may also aid in biomarker discovery. Detection of neurofilament-light (Nf-L) in the CSF has recently been shown to correlate well with disease progression and prognosis in ALS and neurodegeneration (Verde et al., 2021). Though this intracellular neuronal protein is presumably released during motor neuron death, identification other proteins or metabolites may offer greater resolution in measuring treatment response and disease progression.

Cell death is a defining event in both normal development and disease pathophysiology. Advances in innate immunology, and cell death have mapped novel PCD pathways that are now implicated in ALS and neurodegeneration more broadly. Examining these pathways in detail may offer novel therapeutic strategies for patients and give biologists a greater understanding of how cells in the brain live and die.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge funding support from National Institutes of Health (5R01DK127257-02 and 5R01AI130019-05), Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and Kenneth Rainin Foundation. This work was also supported by award number T32GM007753 (NIGMS) (DVN). All figures were created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests:

I.M.C. serves on scientific advisory boards of GSK pharmaceuticals and Limm therapeutics. His lab receives research support from Abbvie/Allergan pharmaceuticals.

References

- Abe K, Aoki M, Tsuji S, Itoyama Y, Sobue G, Togo M, Hamada C, Tanaka M, Akimoto M, Nakamura K, et al. (2017). Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology 16, 505–512. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczak SE, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dale G, Brand FJ, Nonner D, Bullock MR, Dahl GP, Dietrich WD, and Keane RW (2014). Pyroptotic neuronal cell death mediated by the AIM2 inflammasome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34, 621–629. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A, van den Berg LH, and Veldink J (2017). Gene discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Implications for clinical management. Nature Reviews Neurology 13, 96–104. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta DA, and Dixon SJ (2020). Investigating Nonapoptotic Cell Death Using Chemical Biology Approaches. Cell Chemical Biology 27, 376–386. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Miwa M, Miwa K, Hanayama R, Nagase H, Nagata S, and Tanaka M (2004). Masking of phosphatidylserine inhibits apoptotic cell engulfment and induces autoantibody production in mice. J Exp Med 200, 459–467. 10.1084/jem.20040342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baleriola J, Walker CA, Jean YY, Crary JF, Troy CM, Nagy PL, and Hengst U (2014). Axonally synthesized ATF4 transmits a neurodegenerative signal across brain regions. Cell 158, 1159–1172. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroja-Mazo A, Martín-Sánchez F, Gomez AI, Martínez CM, Amores-Iniesta J, Compan V, Barberà-Cremades M, Yagüe J, Ruiz-Ortiz E, Antón J, et al. (2014). The NLRP3 inflammasome is released as a particulate danger signal that amplifies the inflammatory response. Nat Immunol 15, 738–748. 10.1038/ni.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]