Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted rapid, reflexive transition from face-to-face to online healthcare. For group-based addiction services, evidence for the impact on service delivery and participant experience is limited.

Methods

A 12-month (plus 2-month follow-up) pragmatic evaluation of the upscaling of online mutual-help groups by SMART Recovery Australia (SRAU) was conducted using The Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. Data captured by SRAU between 1st July 2020 and 31st August 2021 included participant questionnaires, Zoom Data Analytics and administrative logs.

Results

Reach: The number of online groups increased from just 6 pre-COVID-19 to 132. These groups were delivered on 2786 (M = 232.16, SD = 42.34 per month) occasions, to 41,752 (M = 3479.33, SD = 576.34) attendees. Effectiveness: Participants (n = 1052) reported finding the online group meetings highly engaging and a positive, recovery supportive experience. 91 % of people with experience of face-to-face group meetings rated their online experience as equivalent or better. Adoption: Eleven services (including SRAU) and five volunteers delivered group meetings for the entire 12-months. Implementation: SRAU surpassed their goal of establishing 100 groups. Maintenance: The average number of meetings delivered [t(11.14) = -1.45, p = 0.1737] and attendees [t(1.95) = -3.28, p = 0.1880] per month were maintained across a two-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

SRAU scaled-up the delivery of online mutual-help groups in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings support the accessibility, acceptability and sustainability of delivering SMART Recovery mutual-help groups online. Not only are these findings important in light of the global pandemic and public safety, but they demonstrate the potential for reaching and supporting difficult and under-served populations.

Keywords: SMART Recovery; Mutual-help; Digital Recovery Support Services; Substance Use Disorders, COVID-19; RE-AIM

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on mental health and wellbeing. A range of mental health related consequences have been documented, (Ornell et al., 2020) including elevated rates of stress, anxiety and depression worldwide (Torales et al., 2020, Hossain et al., 2020). Hazardous rates of alcohol use, smoking and other substances have also increased (Ornell et al., 2020). Other potentially problematic behaviours associated with internet use, gambling and gaming have risen to unprecedented levels (Dubey et al., 2020). People with pre-existing experience of mental health conditions and/ or addictive behaviours are particularly vulnerable to the psychological impact of the pandemic (Ornell et al., 2020, Hossain et al., 2020).

The isolation and physical distancing measures introduced to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 significantly disrupted face-to-face service provision for people with experience of addictive behaviours, (Du et al., 2020) necessitating increased use of online technologies by health and social care providers. Remote delivery allows the provision of accessible, flexible, tailored support even under restrictive pandemic conditions (Rauschenberg et al., 2021). Accumulating evidence supports the feasibility and acceptability of using video-conferencing platforms (e.g. Zoom) to deliver healthcare (Kruse et al., 2017). Preliminary evidence also supports the clinical and cost effectiveness of telehealth for people with addictive behaviours (Kruse et al., 2020, Jiang et al., 2017, Lin et al., 2019). However, evidence for group-based telehealth services is currently limited (Gentry et al., 2019). Given that social connectedness is central to recovery from addictive behaviours; (Bathish et al., 2017) remote access to group-based services may be particularly important for addressing the mental and behavioural challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mutual-help groups are one of the most common, accessible and valued methods for accessing support for addictive behaviours (Kaskutas et al., 2014, Kelly and Yeterian, 2011). A range of mutual-help groups are available, including 12-step programs (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous) and other secular options, including SMART Recovery, Women for Sobriety and LifeRing. (Zemore, 2017) Increasing evidence supports the benefits of mutual-help groups for improving substance use, (Beck et al., 2017, Kelly et al., 2020) and mental health outcomes. (Bassuk et al., 2016) Mutual-help groups have been found to enhance recovery supportive social connections, coping skills, self-efficacy and recovery motivation. (Tracy and Wallace, 2016, Kelly, 2017) People may also be more willing to attend mutual-help groups due to the stigma associated with accessing specialist addiction services. (Faulkner et al., 2013, du Plessis et al., 2020, Watson, 2019, Eddie et al., 2019) However, compared to current understanding of face-to-face mutual-help groups, comparatively less is known about remote access delivery. (Ashford et al., 2020, Bergman et al., 2018) Much of the evidence is derived from either evaluations of asynchronous groups (e.g. forums), (Haug et al., 2020, Schwebel and Orban, 2022, Bergman et al., 2017, Chambers et al., 2017) or virtual delivery of 12-step groups, (Penfold and Ogden, 2021, Bender et al., 2022, Hoffmann and Dudkiewicz, 2021, Galanter et al., 2022, Senreich et al., 2022, Barrett and Murphy, 2021) with scant evidence for online SMART Recovery groups. (Timko et al., 2022, Beck et al., 2022) Given that not all individuals engage well with 12-step approaches, research examining participant experience of alternative approaches is an important priority. (Bergman et al., 2021).

SMART Recovery mutual-help groups incorporate evidence-based principles and strategies (e.g. motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy) to offer support for a range of addictive behaviours. (Kelly et al., 2017) SMART Recovery group based meetings are based on a four-point program (building motivation, coping with urges, problem solving and lifestyle balance) and all meetings are led by a trained facilitator. (SMART, xxxx) SMART Recovery Australia (SRAU) partners with volunteers and a range of general health, mental health and addiction service providers across the private, public and not for profit sectors to deliver mutual-help groups nationwide.

1.1. The current evaluation

Prior to COVID-19, Australian SMART Recovery groups provided support to approximately 2200 people each week across 346 face-to-face groups and just six online groups. To meet the continued support needs of people with addictive behaviours during the pandemic, SRAU was awarded funding by the Commonwealth Government of Australia under the Drug and Alcohol Program to upscale online delivery of SMART Recovery groups. SRAU sought to establish at least 100 online groups during the 12-month funded project. To maximise sustainability, SRAU set a goal of 80 % of groups delivered by third-party providers (including trained facilitators located within private, not-for-profit and government run health and social care organisations), and 20 % by SRAU staff and volunteers. This goal was based on the staff, time and resources available in-house for delivering mutual-help groups. To address inequity in service provision, SRAU also sought to establish groups for targeted cohorts (women and culturally, linguistically and gender diverse people). The current evaluation examined the Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) of the scaling up of SRAU’s online mutual-help groups in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

Ethics approval was granted by the Joint University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH02893). This evaluation was conducted across a 14-month period, comprising the 12-month funded SRAU project, and subsequent 2-months. It was informed by the RE-AIM (Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance) framework. (Glasgow et al., 2019) This framework is a well-utilised, evidence based approach that is employed within health-care and community settings to direct the planning and evaluation of innovations to service delivery. (Glasgow et al., 2019) To maximise the uptake and sustainability of healthcare innovations, this framework guides evaluators to consider key factors across the level of the individual, service provider, setting and organisation. Aligned with published recommendations for ensuring that these considerations guide the evaluation of real-world initiatives, we adopted a pragmatic approach (Glasgow and Estabrooks, 2018) that leveraged real-world data captured by SRAU. The definition of each RE-AIM domain, (Glasgow and Estabrooks, 2018) operationalisation within the current evaluation and data sources are summarised in Table 1 . Briefly, Reach focuses on data collection at the level of attendees and meetings; Effectiveness is indexed by participant evaluation; Adoption focuses on data collection at the level of the provider and organisation; Implementation outcomes focus on the overall initiative and are therefore derived from apriori targets established by SRAU and Maintenance focuses on the two months following the 12-month funding period with regard to attendees and meetings. For context, we begin by summarising how SRAU approached the task of upscaling online service provision.

Table 1.

Summary of the five domains of the RE-AIM framework according to the definition, operationalisation and data source.

| Domain | Definition | Operationalisation | Data Source |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zoom Data Analytics | Participant Questionnaire (n = 1052) |

SRAU Administrative Logs | |||

| Reach | |||||

| Number and representativeness of people willing to engage with a given initiative |

|

✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| Effectiveness | |||||

| Impact of an initiative on service user outcomes |

|

✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| Adoption | |||||

| Number and representativeness of settings and providers willing to deliver an initiative |

|

✓ | |||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

| Implementation | |||||

| Degree to which an initiative is delivered ‘as intended’ |

|

||||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Maintenance | |||||

| The extent to which an initiative becomes routine within organisational practices and/ or policies |

|

✓ | ✓ | ||

|

|||||

|

|||||

Note.aTo account for the facilitator, ‘attendees’ are defined as (total number of participants −1) × the total number of groups; bAverage delivery per month per group is derived from the total number of times the each group was delivered, divided by the number of months it was delivered at least once; cIn addition to descriptive statistics, the number of volunteers and service providers who delivered online groups at least once within every month of the evaluation was calculated and used as an index of ongoing engagement; c Calculated as the number of Unique meeting IDs used to deliver groups (n = 174) minus the number of IDs only used once (n = 42) minus the six existing meetings.

2.1. Summary of SRAU methods

To begin, SRAU supported existing facilitators to transition their face-to-face groups online. Contact was made with volunteers and third-party providers to explore the option of moving their group(s) online. SRAU provided interested parties with log-in details for Zoom, supported them to set-up their Zoom account and helped orient them to the Zoom platform (as needed). Facilitators then nominated the preferred date and time of their group, which was added by SRAU to the list of advertised groups available on the SRAU website. SRAU endeavoured to offer a support call following the first online group conducted by each facilitator.

New facilitators were also trained using a purpose built online training platform developed in 2019. This two phase training involves four modules of training content, and a collection of video role-plays demonstrating SMART Recovery group facilitation skills. A skill development session with a SRAU trainer and four trainees conducted via Zoom comprised the second phase. Following completion of training, facilitators were asked to notify SRAU if they wished to start an online group. Interested facilitators were then supported to establish a group as per the methods outlined above. Over the course of the project SRAU developed several resources to support facilitators. This included a PowerPoint slideshow to help guide the structure of online groups, and a Facilitator Network Facebook group for all online and in-person facilitators. SRAU also offered fortnightly facilitator support groups via Zoom to any interested facilitators.

2.2. RE-AIM evaluation

2.2.1. Data source

Throughout the total 14-month evaluation period (1st July 2020 to 31st August 2021) SRAU routinely collected data using three primary methods: self-report participant questionnaire, Zoom data analytics and administrative logs. The research team also conducted a concurrent qualitative evaluation to explore participant and facilitator experience with online groups. These qualitative findings will be reported separately.

2.2.1.1. Self-report participant Questionnaire

A self-selected, convenience sample of participants was recruited. SRAU embedded a link to an online Survey Monkey questionnaire in the post-group Zoom exit page. This brief questionnaire was developed in-house by SRAU to routinely capture participant data and was presented at the end of every meeting held across the duration of the evaluation. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire only once, based on their most recent online group experience. The questionnaire captured basic demographic information and reason/s for attending the online group that day. It also contained items to assess participant experience of the group. A series of five-point Likert scale items assessed participant engagement (the degree to which participants felt they were welcomed, supported, and had an opportunity to contribute); experience (skill of the facilitator, experience of technical difficulties); and self-reported contribution of the online group to recovery (acquisition of practical information and strategies, degree to which the group was experienced as helpful and intention to continue attending). Participants’ use of the ‘seven-day plan’ in the current and preceding group was also assessed. The seven-day plan is a change plan, (SMART, 2016, SMRT, 2015) that comprises one or more realistic, personally meaningful goals for the upcoming week. For example, participants from Australian SMART Recovery groups (Gray et al., 2020) have described how they use the seven-day plan to set targets for changing their behaviour of concern (e.g. reducing or abstaining from use) and/ or more general lifestyle goals (e.g. commencing, increasing or maintaining engagement in self-care, social, recreational or vocational activities). Progress towards this plan is reviewed in subsequent groups and the plan revised as needed following feedback and self-reflection. Although a range of tools are available to SMART Recovery participants, the survey focused specifically on participant use of the seven-day plan because goal setting is central to the structure of Australian SMART Recovery groups and leaving a session with a seven-day plan is an essential strategy for taking specific action toward goal achievement. For example, prior research in Australian SMART Recovery groups found that participants who left meetings with a seven-day plan were more likely to report the use of behavioural activation. (Kelly et al., 2015) Finally, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with online delivery relative to face-to-face groups. Completion of the questionnaire was anonymous, voluntary and no incentive was provided.

A total of 1107 questionnaires were completed across the 12-month period of funding. Duplicate respondents were identified based on a combination of IP address, gender and age (n = 21). Thirty-four participants declined to have their anonymous data used for research purposes, leaving a sample of 1052 survey respondents. Participant postcode was used to classify the location of respondents according to the five categories of ‘remoteness’ defined by the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC; Major City, Inner Regional, Outer Regional, Remote, Very Remote).

2.2.1.2. Zoom data analytics

Information pertaining to the usage of online groups was automatically captured by Zoom throughout the 14-month evaluation period. The ‘meetings’ section of the Zoom dashboard was used to download information about each SMART Recovery group meeting held (including ‘meeting ID’, host, topic, ‘number of participants’ and ‘meeting duration’). ‘Meeting ID’ is the unique identifier assigned by Zoom to an online group (based on the specified host, time, day and whether or not the meeting is recurring). We defined an ‘established’ group as one that occurred more than once. Therefore, the number of online groups established is defined as (total number of unique meeting IDs used to deliver an online group) – (meeting IDs only used once) – (the number of online groups running prior to the current evaluation). The number of ‘groups delivered’ (i.e. ‘meetings’) is defined as the total number of online SMART Recovery groups delivered via the SMART Recovery zoom account across the evaluation period (i.e. including one-off meetings). The ‘number of participants’ metric in Zoom is derived from the number of log-ins to a given group and captured and stored as an aggregate value. Although we are unable to account for multiple log-ins by the same attendee across the study period, to account for the facilitator, we defined “attendees” as: (total ‘number of participants’ – 1) × the total number of ‘groups delivered’.

2.2.1.3. Administrative logs

SRAU maintained administrative logs using Arlo Training Management Software and Microsoft Excel to capture data pertaining to project milestones, third-party organisations and facilitator training (e.g. training completion; registration as a facilitator; facilitator name and organisation; facilitator email address). The number of third-party providers with the potential ‘capacity’ to deliver online groups is based on the number of third-party providers who a) were provided with log-in details and were oriented to the Zoom platform, b) had one or more facilitators complete training and/ or c) delivered one or more online groups during the 12-month funded project period.

2.2.2. Statistical analysis

Each element of the RE-AIM framework was analysed separately. The CSV files for the participant questionnaire and all Zoom Data analytics were downloaded and analysed using SPSS or Microsoft Excel. All quantitative data was summarised using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range, sum and/ or proportion), as appropriate. To examine consistency of group delivery across time, we firstly calculated the total number of times that each group was delivered and then the number of months in which it was delivered at least once. These values were used to generate an estimate of the average number of times per month each group was delivered while accounting for the varied duration of delivery across the 12–months of the evaluation. Aligned with recommendations for reducing bias and controlling Type I error when comparing two independent groups, (Delacre et al., 2017) we adopted a conservative approach and compared the average number of groups and attendees per month during the maintenance phase to the preceding 12-month evaluation period using separate Welch’s t-tests. (Gaetano, 2019).

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Reach

Between 1st July 2020 and 30th June 2021 a total of 2786 meetings were delivered to approximately 41,752 attendees. In any one month, an average of 232.16 (SD = 42.34; Range = 178–312) meetings were delivered to an average of 3479.33 (SD = 576.34; Range = 2512 to 4538) attendees. For each meeting delivered there was an average of 14.98 (SD = 10.85; Range = 1–73) attendees. On average, each group was delivered on approximately 16 occasions (M = 16.98, SD = 17.54; Range = 1–66) across approximately-four months (M = 4.89, SD = 4.07; Range = 1–12), equating to roughly-three meetings per month, per group.

The characteristics of survey respondents are presented in Table 2 . Approximately half of respondents were male (n = 547, 52 %) and aged 35–44 (n = 275, 26.1 %). Approximately 2 % were of Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander descent (n = 26). The majority of respondents were located in ‘major city’ locations (n = 753, 71 %). Use of alcohol was the most frequently endorsed reason for attending an online SMART Recovery group (n = 761; 72 %), followed by tobacco (n = 139; 13.2 %) and methamphetamine (n = 136; 12 %) use. More than a third selected multiple behaviours (n = 406, 38.6 %; M = 1.63, SD = 1.17; Range = 0–11) as their reason for attending. A total of 485 (46.1 %) participants attended an online SMART Recovery group for the first time on the day that they completed the survey.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and behaviour(s) of concern for the sample of online participants (n = 1052) who completed the participant questionnaire.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 546 (51.9) |

| Female | 492 (46.8) |

| Transgender female | 0 (0) |

| Transgender male | 1 (0.09) |

| Non-binary/ indeterminate | 8 (0.7) |

| Not stated | 4 (0.3) |

| Age | |

| Under 18 | 3 (0.2) |

| 18–24 | 67 (6.3) |

| 25–34 | 219 (20.8) |

| 35–44 | 275 (26.1) |

| 45–54 | 265 (25.1) |

| 55–64 | 186 (17.6) |

| 65+ | 37 (3.5) |

| Ethnicity and Cultural Identification | |

| Neither Aboriginal nor Torres Strait Islander | 1026 (97.5) |

| Aboriginal but not Torres Strait Islander | 22 (2.09) |

| Both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 4 (0.38) |

| Participant Locationa | |

| New South Wales | 543 (51.6) |

| Victoria | 272 (25.8) |

| Queensland | 120 (11.4) |

| South Australia | 37 (3.5) |

| Western Australia | 34 (3.2) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 15 (1.4) |

| Tasmania | 8 (0.76) |

| Northern Territory | 4 (0.38) |

| International | 5 (0.47) |

| Participant remoteness categorya,b | |

| Major City | 753 (71.5) |

| Inner Regional | 210 (19.9) |

| Outer Regional | 51 (4.8) |

| Remote | 9 (0.8) |

| Very remote | 9 (0.8) |

| Behaviour(s) of concern that prompted group attendancec | |

| Alcohol | 761 (72.33) |

| Tobacco | 139 (13.21) |

| Methamphetamine | 136 (12.92) |

| Cannabis | 132 (12.54) |

| Other drugs | 187 (17.77) |

| Food | 96 (9.12) |

| Gambling | 51 (4.84) |

| Sex | 45 (4.27) |

| Shopping | 42 (3.99) |

| Porn | 30 (2.85) |

| Internet | 18 (1.71) |

| Other behaviours | 83 (7.88) |

| None | 16 (1.52) |

Note.aMissing data for 15 participants did not provide their postcode; bDoes not include the 5 international participants; cParticipants could select more than one behaviour.

2.3.2. Effectiveness

Participant responses regarding engagement, experience and recovery are presented in Table 3 . Self-reported engagement with the online group meetings was strong, with the majority of survey respondents endorsing ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ with feeling welcomed (n = 986, 93 %), supported (n = 961, 91 %) and having an opportunity to contribute (n = 962, 91 %). Participant experience was largely positive, with the majority of participants endorsing ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to the meeting being well facilitated (n = 970, 92 %), although one in five respondents (n = 219, 20.81 %) endorsed either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to experiencing technical difficulties. Online groups made a positive contribution to the recovery of the majority of respondents with 85 % (n = 900) leaving the meeting with practical information, strategies and/ or resources; 90 % experiencing the group as helpful (n = 948) and 91 % (n = 965) intending to continue attending online SMART Recovery groups. Of the 567 (53.9 %) participants who had attended a SMART Recovery meeting previously, 370 (35 %) had attended the previous week. Of those, 262 (70.8 %) left that meeting with a seven-day plan. Of the participants who completed a seven-day plan the preceding week, the majority reported that they found the plan to be very (n = 118, 45 %) or extremely (n = 80, 31 %) helpful.

Table 3.

Self-reported engagement, experience and impact on recovery reported by the subsample of online group participants who completed the online questionnaire (n = 1052). Findings are presented as M (SD) and the proportion of participants who endorsed each Likert scale category (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree).

| M (SD) | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Slightly Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | ||||||

| I felt welcome at today’s meeting | 4.55 (0.89) | 43 (4.1 %) | 6 (0.6 %) | 17 (1.6 %) | 241 (22.9 %) | 745 (70.8 %) |

| I felt supported and understood by people attending the meeting | 4.43 (0.92) | 42 (4 %) | 10 (1 %) | 39 (3.7 %) | 320 (30.4 %) | 641 (60.9 %) |

| I had an opportunity to contribute to the group discussion | 4.47 (0.93) | 44 (4.2 %) | 9 (0.9 %) | 37 (3.5 %) | 279 (26.5 %) | 683 (64.9 %) |

| Experience | ||||||

| Today’s group was well facilitated | 4.50 (0.92) | 45 (4.3 %) | 7 (0.7 %) | 30 (2.9 %) | 256 (24.3 %) | 714 (67.9 %) |

| I experienced technical difficulties during the meeting | 2.14 (1.41) | 522 (49.6 %) | 202 (19.2 %) | 109 (10.4 %) | 94 (8.9 %) | 125 (11.9 %) |

| Contribution to Recovery | ||||||

| I took away practical strategies/ideas/ tools from today’s group to help me manage my behaviour | 4.27 (0.98) | 43 (4.1 %) | 19 (1.8 %) | 90 (8.6 %) | 357 (33.9 %) | 543 (51.6 %) |

| Overall, I found todays group helpful | 4.41 (0.93) | 41 (3.9 %) | 12 (1.1 %) | 51 (4.8 %) | 310 (29.5 %) | 638 (60.6 %) |

| I plan on continuing to attend SMART online | 4.51 (0.87) | 35 (3.3 %) | 6 (0.6 %) | 46 (4.4 %) | 265 (25.2 %) | 700 (66.5 %) |

A total of 555 participants responded to the question about how online groups compared to face-to-face (SRAU added this question after data collection had commenced). Just over one-third (n = 210, 37 %) had only attended online meetings, so could not make a comparison. Of the remaining 345 participants, approximately half indicated that online meetings were either ‘better’ (n = 89, 26 %) or ‘much better’ (n = 89, 26 %) than face-to-face meetings and just over one third felt they were ‘about the same’ (n = 129, 37 %).

2.3.3. Adoption

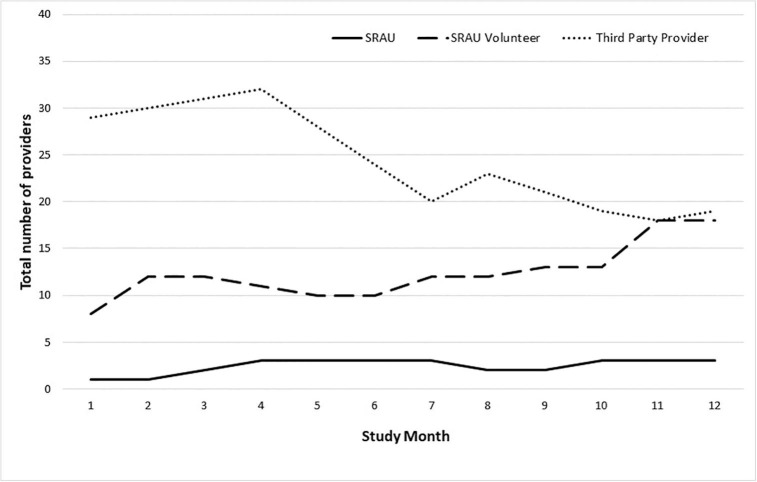

Half (n = 38, 50 %) of the third-party service providers with the potential capacity to deliver online groups delivered at least one online meeting during the 12-month evaluation period. The total number of SRAU staff, volunteers and third-party providers per month who delivered online meetings across the initial 12-month evaluation period is presented in Fig. 1 . A total of 11 services (including SRAU) and five volunteers delivered online meetings for the entire 12-month duration of the evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Total number of providers per month who delivered at least one online meeting.

A total of 130 new facilitators completed training during the initial 12-month evaluation period, comprising 109 individuals working across 47 different services. Service information for the remaining 21 individuals was not provided. Of these 47 services, less than one third (n = 13, 27.6 %) went on to deliver an online meeting.

2.3.4. Implementation

The number of new online SMART Recovery mutual-help groups established during the initial 12-month evaluation period (n = 126) exceeded SRAU’s a-priori target of 100. Aligned with their target involvement of third-party providers, almost 80 % of all meetings (n = 2118, 76 %) were delivered by third-party providers. Third-party providers included a range of private, not-for-profit and government run organisations delivering addiction services, general health or social care within community, residential and/ or inpatient settings. Regarding equity, of the 2786 meetings delivered, 375 (13.4 %) were targeted to provide a dedicated support space for: women (n = 134, 4.8 %); men (n = 55, 1.9 %); young people (n = 56, 2 %); family and friends (n = 118, 4.3 %); people of Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander descent (n = 11, 0.3 %) and Korean language speakers (n = 1, 0.03 %).

2.3.5. Maintenance

In the two-months following the funded 12-month project, a further 500 meetings (M = 250, SD = 1.41, Range = 249–251 per month) were delivered. These meetings were attended by approximately 8988 attendees (M = 4494, SD = 367.69, Range = 4234–4754 per month), with an average of 17.97 (SD = 12.73) attendees per meeting (Range = 1 to 103). The average number of meetings [t(11.14) = -1.45, p = 0.1737] and attendees [t(1.95) = -3.28, p = 0.1880] per month during the maintenance phase did not significantly differ from the preceding 12-month evaluation period.

3. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered widespread closure of SMART Recovery mutual-help groups across the world. (Kelly et al., 2021) To meet the continued support needs of people affected by addictive behaviours, SRAU undertook a project to expand the delivery of online mutual-help groups. In light of limited evidence for the delivery of online groups for addictive behaviours, the purpose of the current evaluation was to assess the impact of this real-world healthcare innovation. Although we are unable to partial out the increase in online service provision that would have occurred naturally within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this pragmatic evaluation demonstrated positive change across all domains of the RE-AIM framework. (Glasgow et al., 2019, Glasgow and Estabrooks, 2018) Moreover, this study contributes new knowledge on the characteristics of attendees and how these online-groups were experienced by participants during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding participant characteristics, the age, location and primary behaviour of concern reported by participants in the current study appears broadly consistent with published Australian data for face-to-face groups. (Raftery et al., 2019, Kelly et al., 2021, Beck et al., 2021) However, consistent with recent evidence for the gender distribution of online mutual-help groups, (Timko et al., 2022, Beck et al., 2022) the current sample does appear to comprise a larger proportion of females (46.8 %) than that of Australian face-to-face groups (31.9 %-39 %). (Raftery et al., 2019, Kelly et al., 2021, Beck et al., 2021) This may be due to the increase in the number of women only groups offered during the study period. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that women seeking treatment for addictive behaviours may prefer single gender groups. (Sugarman et al., 2022) Telehealth may also help to overcome a range of barriers encountered by women when trying to access treatment and support. (Goldstein et al., 2018).

Our findings also point to the potential therapeutic benefit of online mutual-help groups. Participant evaluation of online SMART Recovery groups was extremely positive with regard to engagement, experience and impact on recovery. The majority of survey respondents felt welcomed, supported and able to contribute. This is especially promising given that group cohesion may be adversely affected in online settings. (Sugarman et al., 2021) Indeed, of those who had previously attended face-to-face groups 89 % felt that online groups were just as good (37 %) or better (52 %). Similarly, in a survey of 12-step attendees, the majority found that online meetings were at least ‘as effective’ for promoting abstinence as face-to-face meetings. (Galanter et al., 2022) Given the widespread and rapid transition of face-to-face healthcare services to virtual delivery seen during COVID-19, (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic., 2020) concerns regarding the resultant impact on participant experience and the quality of service provision have been raised. (Mark et al., 2021, Sugarman et al., 2021) The current study adds to a growing body of evidence (Galanter et al., 2022, Senreich et al., 2022, Timko et al., 2022) (but see also (Barrett and Murphy, 2021) that goes some way to allaying these concerns.

Although 20 % of respondents in the current evaluation experienced technical difficulties, the majority still found the groups to be helpful. Participants gained knowledge that supported recovery and many engaged in the seven-day plan, an important behaviour change strategy. These findings are promising since active engagement and coping skills represent important predictors of treatment outcome within face-to-face mutual-help groups. (Marcovitz et al., 2020, Kelly et al., 2009) Evaluations to examine the contribution of online mutual-help groups to participant recovery are needed. However, given that online treatment and support may be less effective, (Gentry et al., 2019, Jenkins-Guarnieri et al., 2015) and less suitable for certain clinical groups, (Bergman and Kelly, 2021) clarifying the participant and contextual variables that influence the effectiveness of online mutual-help groups represents an important challenge for future research.

This study also provides preliminary evidence in support of the feasibility of delivering SMART Recovery mutual-help groups online. SRAU surpassed its project target and established a total of 126 new online groups in 12-months. Prior to this initiative, only six online groups were available. Under pandemic conditions, SRAU worked with volunteers and third-party service providers to deliver over 2700 meetings to approximately 42,000 attendees. In the subsequent 2-months, at a time when face-to-face service provision began to resume, a further 500 meetings were delivered to over 8,000 attendees, with the average number of meetings delivered and attendees per month maintained. Evidence regarding virtual support groups for addictive behaviours is limited, but promising. (Oesterle et al., 2020, Bergman and Kelly, 2021) Within the broader literature, evidence for the feasibility of online service provision for addictive behaviours, (Mark et al., 2021, Molfenter et al., 2021) and the willingness of providers (Molfenter et al., 2021, Cantor et al., 2021) and patients (Sugarman et al., 2021) to engage with this mode of service delivery is growing. However, virtual delivery of groups also comes with a range of practical and clinical challenges (e.g., connectivity, safety and size). (Sugarman et al., 2022, Sugarman et al., 2021) The impact of these challenges on the delivery, experience and effectiveness of online treatment and support is unclear. Further research is needed to understand how best to optimise online service provision for addictive behaviours.

Our findings also lend insight into two key opportunities for extending the reach of online SMART Recovery mutual-help groups. Firstly, there is a need to improve access for priority clinical groups. (Institute, 2020) This includes young people, older people, culturally and linguistically diverse populations and people identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or intersex. (Institute, 2020) Although we are unable to comment on the actual number of people within these priority groups who attended an online meeting across the evaluation period, consistent with published Australian data from face-to-face SMART Recovery meetings, (Raftery et al., 2019, Beck et al., 2021) the majority of participants who completed the online questionnaire identified with a binary gender, were aged between 35 and 54 and did not identify as Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander, suggesting a need to continue actively targeting the priority clinical groups noted above. Improved understanding of how best to address the support needs of these individuals is essential. (Kelly et al., 2021) World-first evidence to inform the cultural adaptation of SMART Recovery groups for Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander peoples is now available (Dale et al., 2021, Dale et al., 2021) and an evaluation of an adapted version of SMART Recovery informed by young people for young people is currently underway. Further research is needed to understand how these findings may also inform the delivery of online groups.

Secondly, to maximise access and accessibility of online SMART Recovery groups, there is a need to understand and address barriers to online delivery. Based on the number of third-party providers delivering face-to-face groups pre-COVID, and the number subsequently trained during the evaluation period, the 38 third-party providers who delivered online groups represents approximately half of those with the capacity to do so. This is driven in part by the number of organisations who completed training during the evaluation but did not go on to deliver an online group. Provider attitudes (e.g. preference and comfort) play a key role in willingness to deliver telehealth services for addictive behaviours. (Mark et al., 2021) Practical considerations, for example provider and patient access to adequate technology have also been implicated. (Bergman and Kelly, 2021) Although accessibility issues are more challenging to overcome (indeed, one-fifth of survey respondents encountered significant technical difficulties), ensuring that providers are well-equipped to handle the unique challenges of online group delivery is essential. Drawing from the face-to-face training literature, ongoing supervision, feedback and self-reflection is likely to be key. (Schwalbe et al., 2014, Frank et al., 2020, Caron and Dozier, 2021) We also observed wide variation in the duration that each online group was implemented. Although we can speculate that changes in COVID-19 restrictions and participant/ provider preference for a return to face-to-face service provision may have played a role in whether or not online groups were maintained, further evidence is needed. To help characterise the individual, provider and organisational characteristics that may influence the sustainability of online groups, qualitative evaluations informed by established implementation frameworks (e.g. the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) (Schwebel and Orban, 2022) may be of benefit.

3.1. Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this evaluation is the use of an established, evidence-based framework within the context of a real-world innovation in service delivery. The RE-AIM (Glasgow et al., 2019, Glasgow and Estabrooks, 2018) framework ensured that this evaluation was comprehensive and conducted at the level of the individual, group, service provider and organisation. However, several limitations are also worth mentioning. Firstly, findings are largely based on Zoom data analytics. Although this provides unique insight into participant use of online groups, the number of attendees is derived from the number of log-ins and is therefore likely to be a slightly inflated estimate (e.g. due to people logging into the same group multiple times). As this data is stored in aggregate by Zoom, we are also unable to identify the number of unique attendees. Secondly, data pertaining to the characteristics and experience of participants are subject to bias. Findings are derived from a small subsample of people who self-selected to complete the online questionnaire. Administration of the questionnaire at the end of the group also means that we did not capture the characteristics of those attendees who left early (and therefore may have been less satisfied with the group). The majority of the participants also completed the questionnaire at the end of their first meeting, meaning we are unable to comment on whether and how the experience and characteristics of participants may have changed across time. Thirdly, although it is not uncommon to use self-reported Likert scale questionnaires as a pragmatic index of effectiveness (e.g.), (Miller et al., 2021) these findings would be strengthened via the use of standardised, validated instruments, for example by assessing quality of life and other participant reported outcomes. Recent developments in routine outcome monitoring (Kelly et al., 2021, Beck et al., 2021, Kelly et al., 2020) may be of use. Finally, the design of this pragmatic evaluation is such that we are unable to draw causal inferences regarding the increase in online mutual-help provision observed.

3.2. Conclusions

The current evaluation describes how SRAU scaled-up the delivery of online SMART Recovery mutual-help groups in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. SRAU worked alongside volunteers and a diverse range of third-party service providers to deliver online SMART Recovery groups to more than 50,000 attendees across the 14-month evaluation period. Testimony to the feasibility and acceptability of delivering mutual-help groups online, groups were well attended and evaluated favourably by participants. Efforts to maximise existing capacity within partner organisations, enhance engagement with priority client groups and identify and address the training and support needs of online facilitators are warranted. Together with the current evaluation, these findings can be used to ensure that SRAU is well positioned to continue delivering an important and accessible support option to a diverse range of people affected by addictive behaviours.

Author disclosures

Role of funding source

This project was commissioned by SMART Recovery Australia and is supported by funding from the Commonwealth Government of Australia under the Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs - COVID-19 Response Grant. The funding body had no input into the design of the study; analysis and interpretation of data; or writing and submission of the manuscript.

Authorship statement

Authorship follows ICMJE recommendations (Mark et al., 2021). All authors made substantial contributions to conception, design, methods and/ or the content of the current publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alison K. Beck: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Briony Larance: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Amanda L. Baker: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Frank P. Deane: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Victoria Manning: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Leanne Hides: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Peter J. Kelly: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors volunteer as members of the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory committee.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ashford R.D., Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F., Curtis B. Systematic review: Digital recovery support services used to support substance use disorder recovery. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020;2(1):18–32. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A.K., Murphy M.M. Feeling Supported in Addiction Recovery: Comparing Face-to-Face and Videoconferencing 12-Step Meetings. Western Journal of Communication. 2021;85(1):123–146. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2020.1786598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk E.L., Hanson J., Greene R.N., Richard M., Laudet A. Peer-Delivered Recovery Support Services for Addictions in the United States: A Systematic Review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2016;63:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathish R., Best D., Savic M., Beckwith M., Mackenzie J., Lubman D.I. “Is it me or should my friends take the credit?” The role of social networks and social identity in recovery from addiction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2017;47(1):35–46. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.K., Forbes E., Baker A.L., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Shakeshaft A., et al. Systematic review of SMART Recovery: Outcomes, process variables, and implications for research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017;31(1):1–20. doi: 10.1037/adb0000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.K., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Baker A.L., Hides L., Manning V., et al. Developing a mHealth Routine Outcome Monitoring and Feedback App (“Smart Track”) to Support Self-Management of Addictive Behaviours. Front. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.677637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.K., Larance B., Deane F.P., Baker A.L., Manning V., Hides L., et al. The use of Australian SMART Recovery groups by people who use methamphetamine: Analysis of routinely-collected nationwide data. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.K., Larance B., Manning V., Hides L., Baker A.L., Deane F.P., et al. Online SMART Recovery mutual support groups: Characteristics and experience of adults seeking treatment for methamphetamine compared to those seeking treatment for other addictive behaviours. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2022 doi: 10.1111/dar.13544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A.K., Pickard J.G., Webster M. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on older adults in 12-step programs. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2022 doi: 10.1080/1533256X.2022.2047561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Claire Greene M., Hoeppner B.B., Kelly J.F. Expanding the reach of alcohol and other drug services: Prevalence and correlates of US adult engagement with online technology to address substance problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;87:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F. Online digital recovery support services: An overview of the science and their potential to help individuals with substance use disorder during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F., Fava M., Eden E.A. Online recovery support meetings can help mitigate the public health consequences of COVID-19 for individuals with substance use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2021;113:106661 -. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Kelly N.W., Hoeppner B.B., Vilsaint C.L., Kelly J.F. Digital recovery management: Characterizing recovery-specific social network site participation and perceived benefit. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017;31(4):506–512. doi: 10.1037/adb0000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., McBain R.K., Kofner A., Hanson R., Stein B.D., Yu H. Telehealth adoption by mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Services. 2021 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E.B., Dozier M. Self-coding of fidelity as a potential active ingredient of consultation to improve clinicians' fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2021;49(2):237–254. doi: 10.1007/s10488-021-01160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020.

- Chambers S.E., Canvin K., Baldwin D.S., Sinclair J.M.A. Identity in recovery from problematic alcohol use: A qualitative study of online mutual aid. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;174:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale E., Conigrave K.M., Kelly P.J., Ivers R., Clapham K., Lee K.S.K. A Delphi yarn: Applying Indigenous knowledges to enhance the cultural utility of SMART Recovery Australia. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2021;16(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13722-020-00212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale E., Lee K.S.K., Conigrave K.M., Conigrave J.H., Ivers R., Clapham K., et al. A multi-methods yarn about SMART Recovery: First insights from Australian Aboriginal facilitators and group members. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dar.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delacre M., Lakens D., Leys C. Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of student’s t-test. International Review of. Social Psychology. 2017:30. [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Fan N., Zhao M., Hao W., Liu T., Lu L., et al. Expert consensus on the prevention and treatment of substance use and addictive behaviour-related disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(4):e100252. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis C., Whitaker L., Hurley J. Peer support workers in substance abuse treatment services: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Substance Use. 2020;25(3):225–230. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2019.1677794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey M.J., Ghosh R., Chatterjee S., Biswas P., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. COVID-19 and addiction. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2020;14(5):817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddie D., Hoffman L., Vilsaint C., Abry A., Bergman B., Hoeppner B., et al. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: A systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10(1052) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner A., Sadd J., Hughes A., Thompson S., Nettle M., Wallcraft J., et al. Mind; London: 2013. Mental health peer support in England: Piecing together the jigsaw. [Google Scholar]

- Frank H.E., Becker-Haimes E.M., Kendall P.C. Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: A systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2020;27(3):e12330. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetano J. Welch’s t-test for comparing two independent groups: An excel calculator (1.01) [Micorsoft Excel workbook]2019. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332217175_Welch's_t-test_for_comparing_two_independent_groups_An_Excel_calculator_101/link/5ca6bd6a92851c64bd50ba0c/download.

- Galanter M., White W.L., Hunter B. Virtual Twelve Step Meeting Attendance During the COVID-19 Period: A Study of Members of Narcotics Anonymous. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2022;16(2) doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry M.T., Lapid M.I., Clark M.M., Rummans T.A. Evidence for telehealth group-based treatment: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2019;25(6):327–342. doi: 10.1177/1357633x18775855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Estabrooks P.E. Pragmatic applications of RE-AIM for health care initiatives in community and clinical settings. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2018;15:E02. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Harden S.M., Gaglio B., Rabin B., Smith M.L., Porter G.C., et al. RE-AIMpPlanning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers. Public Health. 2019;7(64) doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein K.M., Zullig L.L., Dedert E.A., Alishahi Tabriz A., Brearly T.W., Raitz G., et al. Telehealth Interventions Designed for Women: An Evidence Map. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2018;33(12):2191–2200. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4655-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R.M., Kelly P.J., Beck A.K., Baker A.L., Deane F.P., Neale J., et al. A qualitative exploration of SMART Recovery meetings in Australia and the role of a digital platform to support routine outcome monitoring. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;101 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug N.A., Morimoto E.E., Lembke A. Online mutual-help intervention for reducing heavy alcohol use. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2020;38(3):241–249. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2020.1747331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B., Dudkiewicz M. The Internet as a space for Anonymous Alcoholics during the SARS-COV-2 (Covid-19) pandemic. Global Journal of Health Science. 2021;13(8):61–71. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v13n8p61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.M., Tasnim S., Sultana A., Faizah F., Mazumder H., Zou L., et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Res. 2020;9(636) doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy 2017-2026: A national framework for building safe, healthy and resilient Australian communities through preventing and minimising alcohol, tobacco and other drug related health, social and economic harms among individuals, families and communities. Canberra: AIHW; 2020. Contract No.: Cat. no. PHE 270. .

- Jenkins-Guarnieri M.A., Pruitt L.D., Luxton D.D., Johnson K. Patient perceptions of telemental health: Systematic review of direct comparisons to in-person psychotherapeutic treatments. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. 2015;21(8):652–660. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Wu L., Gao X. Beyond face-to-face individual counseling: A systematic review on alternative modes of motivational interviewing in substance abuse treatment and prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;73:216–235. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas L.A., Borkman T.J., Laudet A., Ritter L.A., Witbrodt J., Subbaraman M.S., et al. Elements that define recovery: The experiential perspective. JSAD. 2014;75(6):999–1010. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.F. Is Alcoholics Anonymous religious, spiritual, neither? Findings from 25 years of mechanisms of behavior change research. Addict. 2017;112(6):929–936. doi: 10.1111/add.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.J., Beck A.K., Baker A.L., Deane F.P., Hides L., Manning V., et al. Feasibility of a Mobile Health App for Routine Outcome Monitoring and Feedback in Mutual Support Groups Coordinated by SMART Recovery Australia: Protocol for a Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(7):e15113. doi: 10.2196/15113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.J., Beck A.K., Deane F.P., Larance B., Baker A.L., Hides L., et al. Feasibility of a Mobile Health App for Routine Outcome Monitoring and Feedback in SMART Recovery Mutual Support Groups: Stage 1 Mixed Methods Pilot Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(10):e25217. doi: 10.2196/25217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Baker A.L. Group cohesion and between session homework activities predict self-reported cognitive-behavioral skill use amongst participants of SMART Recovery groups. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;51:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.F., Humphreys K., Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.F., Magill M., Stout R.L. How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction Research & Theory. 2009;17(3):236–259. doi: 10.1080/16066350902770458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.J., McCreanor K., Beck A.K., Ingram I., O'Brien D., King A., et al. SMART Recovery International and COVID-19: Expanding the reach of mutual support through online groups. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;108568 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.J., Raftery D., Deane F.P., Baker A.L., Hunt D., Shakeshaft A. From both sides: Participant and facilitator perceptions of SMART Recovery groups. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2017;36(3):325–332. doi: 10.1111/dar.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.F., Yeterian J.D. The role of mutual-help groups in extending the framework of treatment. Alch Res Health. 2011;33(4):350–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C.S., Krowski N., Rodriguez B., Tran L., Vela J., Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C.S., Lee K., Watson J.B., Lobo L.G., Stoppelmoor A.G., Oyibo S.E. Measures of effectiveness, efficiency, and quality of telemedicine in the management of alcohol abuse, addiction, and rehabilitation: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(1):e13252. doi: 10.2196/13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.A., Casteel D., Shigekawa E., Weyrich M.S., Roby D.H., McMenamin S.B. Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;101:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcovitz D.E., McHugh K.R., Roos C., West J.J., Kelly J. Overlapping mechanisms of recovery between professional psychotherapies and alcoholics anonymous. Journal of addiction medicine. 2020;14(5):367–375. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark T.L., Treiman K., Padwa H., Henretty K., Tzeng J., Gilbert M. Addiction treatment and telehealth: Review of efficacy and provider insights during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Services. 2021 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.J., Pak S.S., Keller D.R., Barnes D.E. Evaluation of pragmatic telehealth physical therapy implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical Therapy. 2021;101(1) doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T., Roget N., Chaple M., Behlman S., Cody O., Hartzler B., et al. Use of telehealth in substance use disorder services during and after COVID-19: Online survey study. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(2):e25835. doi: 10.2196/25835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle T.S., Kolla B., Risma C.J., Breitinger S.A., Rakocevic D.B., Loukianova L.L., et al. Substance use disorders and telehealth in the COVID-19 pandemic era: A new outlook. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020;95(12):2709–2718. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornell F., Moura H.F., Scherer J.N., Pechansky F., Kessler F.H.P., von Diemen L. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfold K.L., Ogden J. Exploring the experience of Gamblers Anonymous meetings during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Current Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery D., Kelly P., Deane F., Baker A., Dingle G., Hunt D. With a little help from my friends: Cognitive- behavioral skill utilization, social networks, and psychological distress in SMART Recovery group attendees. Journal of Substance Use. 2019 doi: 10.1080/14659891.2019.1664654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschenberg C., Schick A., Hirjak D., Seidler A., Apfelbacher C., Riedel-Heller S., et al. Digital interventions to mitigate the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on public mental health: A rapid meta-review. JMIR. 2021;23(e23365) doi: 10.31234/osf.io/uvc78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe C.S., Oh H.Y., Zweben A. Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/add.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel F.J., Orban D.G. Online support for all: Examining participant characteristics, engagement, and perceived benefits of an online harm reduction, abstinence, and moderation focused support group for alcohol and other drugs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2022 doi: 10.1037/adb0000828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senreich E., Saint-Louis N., Steen J.T., Cooper C.E. The Experiences of 12-Step Program Attendees Transitioning to Online Meetings during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07347324.2022.2102456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SMART Recovery Australia. SMART Recovery Australia participants' manual: Tools and strategies to help you manage addictive behaviours2016.

- SMART Recovery Australia. SMART Recovery Australia [Available from: https://smartrecoveryaustralia.com.au/.

- SMART Recovery Australia. SMART Recovery facilitator training manual: Practical information and tools to help you facilitate a SMART Recovery group2015.

- Sugarman D.E., Busch A.B., McHugh R.K., Bogunovic O.J., Trinh C.D., Weiss R.D., et al. Patients' perceptions of telehealth services for outpatient treatment of substance use disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal on Addictions. 2021;30(5):445–452. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman D.E., Meyer L.E., Reilly M.E., Greenfield S.F. Women's and men's experiences in group therapy for substance use disorders: A qualitative analysis. The American Journal on Addictions. 2022;31(1):9–21. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C., Mericle A., Kaskutas L.A., Martinez P., Zemore S.E. Predictors and outcomes of online mutual-help group attendance in a national survey study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2022;138 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K., Wallace S.P. Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Substance abuse and rehabilitation. 2016;7:143–154. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S81535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson E. The mechanisms underpinning peer support: A literature review. Journal of Mental Health. 2019;28(6):677–688. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore S.E. Implications for future research on drivers of change and alternatives to Alcoholics Anonymous. Addict. 2017;112(6):940–942. doi: 10.1111/add.13728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.