Abstract

Objective

Access to effective treatments for adolescents with depression needs to improve. Few studies have evaluated behavioural activation (BA) for adolescent depression, and none remotely delivered BA. This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of therapist-guided and self-guided internet-delivered BA (I-BA) in preparation for a future randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Design

A single-blinded randomised controlled feasibility trial.

Setting

A specialist outpatient clinic in Sweden.

Participants

Thirty-two adolescents with mild-to-moderate major depression, aged 13–17 years.

Interventions

Ten weeks of therapist-guided I-BA or self-guided I-BA, or treatment as usual (TAU). Both versions of I-BA included parental support. TAU included referral to usual care within child and youth psychiatry or primary care.

Outcomes

Feasibility measures included study take-up, participant retention, acceptability, safety and satisfaction. The primary outcome measure was the blinded assessor-rated Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised. The primary endpoint was the 3-month follow-up.

Results

154 adolescents were screened and 32 were randomised to therapist-guided I-BA (n=11), self-guided I-BA (n=10) or TAU (n=11). Participant retention was acceptable, with two drop-outs in TAU. Most participants in TAU had been offered interventions by the primary endpoint. The mean number of completed chapters (total of 8) for adolescents was 7.5 in therapist-guided I-BA and 5.4 in self-guided I-BA. No serious adverse events were recorded. Satisfaction was acceptable in both I-BA groups. Following an intent-to-treat approach, the linear mixed-effects model revealed that both therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA (Cohen’s d=2.43 and 2.23, respectively), but not TAU (Cohen’s d=0.95), showed statistically significant changes on the primary outcome measure with large within-group effect sizes.

Conclusions

Both therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA are acceptable and potentially efficacious treatments for adolescents with depression. It is feasible to conduct a large-scale RCT to establish the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of I-BA versus TAU.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Registry (NCT04117789).

Keywords: depression & mood disorders, mental health, child & adolescent psychiatry, clinical trials

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Strengths include a randomised controlled design, use of an active control group and careful assessment of the contents of treatment as usual (TAU).

An additional strength was that assessors were blinded to treatment allocation at the primary endpoint.

Limitations include the heterogeneous condition of TAU and blinded assessors correctly guessing group allocation more often than by chance.

Introduction

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide.1 Adolescence is a risk period for developing depression, associated with a sharp increase in prevalence.2 3 Comorbidity with other mental disorders is prevalent among adolescents with depression,4 with sleep disorders and anxiety being among the most common.5 Adolescent depression is associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including impaired academic, social and work functioning,6 7 poor mental and physical health in adulthood,8 9 and increased risk of suicide.10 Early detection and treatment of adolescent depression markedly decrease the likelihood of future clinical depression and other mental health issues.11

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is a well-established intervention for adolescents with depression,12 and is also currently recommended in clinical practice and national guidelines.13 14 Behavioural activation (BA) is an important component of CBT for depression, but can also be delivered as a standalone therapy.15 The main goal of BA is to increase engagement in values-based activities and to decrease the avoidant behaviours that often maintain depressive symptoms.16–19 BA is considered an evidence-based treatment for adults with depression,20 21 and three open trials indicate that BA is also a feasible intervention for adolescents with depression.16 17 19 A small randomised controlled trial (RCT) that compared BA with evidence-based interventions (CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy) showed promising results,18 but BA for depressed adolescents has yet to be evaluated in an adequately powered RCT. BA, unlike traditional CBT for depression, does not include cognitive restructuring,22 although it seems to be equally effective.23 Furthermore, dismantling studies have proposed that BA might be a sufficient treatment component on its own.24 25 In line with this suggestion, a meta-analysis of adolescent depression treatments found that psychological interventions with a cognitive component were no more effective than those without cognitive work.26 Because BA is brief and readily understood, it might suit adolescents particularly well. Another potential benefit is that, given its focus on reducing avoidance behaviours,27 BA may also be effective for reducing anxiety, which is important because anxiety is often comorbid with depression in this age group.5

Despite the high prevalence of depression among young people, only a minority receive evidence-based treatments.28–30 Internet-delivered CBT (ICBT) was developed to improve access to treatment, and has several potential advantages over traditional in-person treatments (bridging geographical distances, requiring less therapist time, lower risk of therapist drift, etc31). Studies in adults have shown that ICBT is effective and probably cost-effective for several psychiatric disorders, including depression.31 In children and adolescents, there is growing support for the efficacy of ICBT for several psychiatric disorders,32 but it is still unclear whether ICBT is an efficacious intervention for adolescent depression. To date, three trials on ICBT with clinically depressed adolescents have been published. Two of them (both N=70) included therapist-chat communication and showed significant reductions in depressive symptoms for adolescents compared with attention control.33 34 The third, an open trial (N=15) investigating the feasibility of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered intervention based on rational emotive behaviour therapy for adolescents diagnosed with anxiety and depressive disorders, found a reduction in self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms.35 A number of ICBT studies have also been conducted in subclinical samples with promising results.36–39

Internet-based interventions can be either therapist guided or self-guided, that is, delivered with or without remote therapist support. According to a recent meta-analysis of ICBT for adults, therapist-guided ICBT was associated with greater improvement than self-guided treatment.40 However, self-guided ICBT was as effective as guided ICBT among adults with mild or subthreshold depression. The importance of therapist support is unclear in children and adolescents, and results are inconsistent.41 42 If ICBT could be entirely unguided, without sacrificing efficacy and safety, it could drastically increase availability to treatment.

Adequately powered trials are needed to explore whether ICBT with and without therapist support is safe, effective and cost-effective for adolescent depression. However, important questions regarding feasibility of study design, acceptability of interventions and preliminary efficacy should be addressed before conducting large trials. Therefore, we designed a randomised feasibility trial of therapist-guided and self-guided internet-delivered BA (I-BA), to compare with treatment as usual (TAU). The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the feasibility of the study design, for example, study take-up, participant retention and feasibility of using TAU as a control group. Secondary objectives were to explore the acceptability of the I-BA interventions, for example, treatment adherence, credibility, satisfaction and adverse events, and to provide preliminary clinical efficacy data to assist with power calculations for a fully powered trial. This will also be the first trial to explore online-delivered BA for depressed adolescents and their parents.

Methods

Study design

This study was a single-blinded, parallel three-arm randomised controlled feasibility trial of therapist-guided I-BA, self-guided I-BA and TAU for adolescents with mild-to-moderate major depressive disorder (MDD). Group allocation was blinded for outcome assessors, but not for participants or therapists. Participants were randomly assigned at a 1:1:1 ratio. The study was conducted at a clinical research unit within Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Stockholm, Sweden. The planned recruitment period was 6 months. Blinded rater assessments were conducted at post-treatment (week 11) and 3-month follow-up (primary endpoint) visits. There were two reasons for setting the 3-month follow-up as the primary endpoint: first, this increased the likelihood that participants assigned to TAU would have received treatment; second, previous ICBT trials have shown a continued improvement from post-treatment to 3-month follow-up.43 44 No changes in the methods were made after the registration and subsequent start of the trial.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were: age 13–17 years; a diagnosis of mild or moderate MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. fifth edition (DSM-5)45; use of psychotropic medications (ie, antidepressants, central stimulants and antipsychotics) that had been stable for at least 6 weeks prior to inclusion; at least one caregiver able to partake in the treatment; both adolescent and caregiver fluent in Swedish; access to the internet via a smartphone and a computer.

Exclusion criteria were: acute psychiatric problems (eg, high risk of suicide or alcohol and substance abuse); social problems requiring other immediate actions (eg, abuse in the family, high and prolonged absence from school); previous CBT for MDD within the last 12 months (defined as ≥3 sessions of CBT/BA, other than psychoeducation); current use of benzodiazepines; ongoing psychological treatment for any psychiatric disorder.

Sample size

This feasibility trial was not powered to detect statistically significant differences between groups. However, we aimed to include a sufficient number of participants to explore within-group changes from baseline to the primary endpoint. In two recent RCTs,18 46 large within-group effects were found on depressive symptoms (d>1.2; d=1.4). Based on previous results, we aimed to recruit a total of 45 participants to be able to detect a within-group effect of d=1.2 (alpha value of 0.05 and 90% power), taking a potentially high attrition of 25% into account. Power calculation was performed using Statulator.47

Recruitment and procedures

Participants were recruited at CAMHS and primary healthcare clinics through information distributed orally and electronically to managers and clinicians, and via flyers distributed in waiting rooms. About 3 months after the study began, we also advertised in newspapers and social media. Referrals from healthcare professionals and self-referrals from families all over Sweden were also accepted.

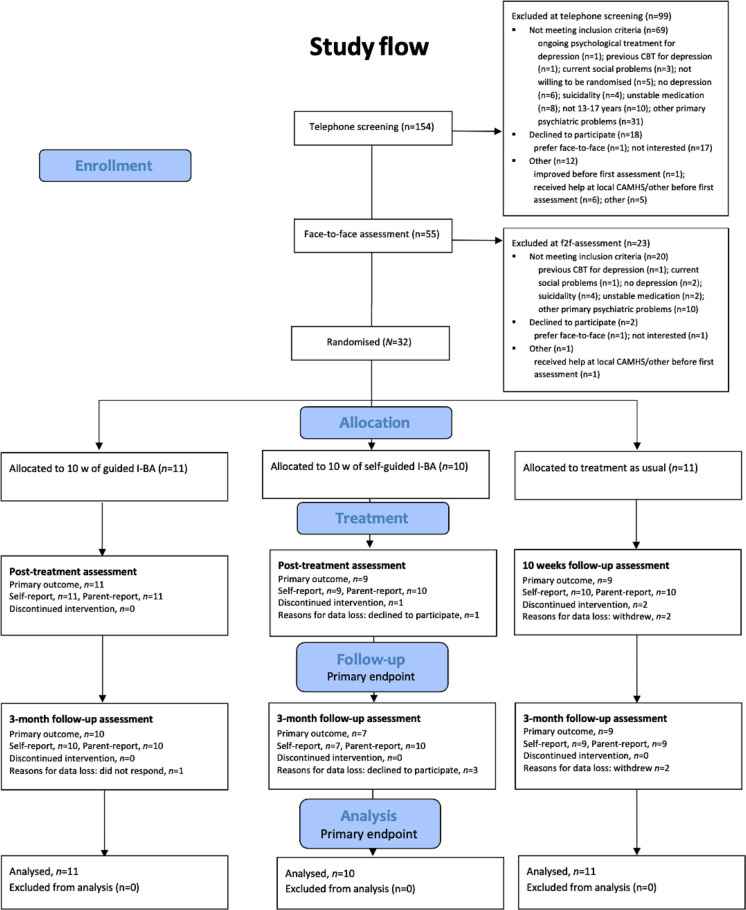

Applicants were first contacted for an initial telephone screening and then invited to a face-to-face visit for a thorough assessment of study eligibility. Video assessments were offered to families who could not travel to the clinic and to everyone after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Verbal and written information was provided to the adolescents and their parents, who all gave written consent. During the face-to-face assessment, a trained psychologist: (a) verified the MDD diagnosis, according to the DSM-5 criteria; (b) assessed current level of depression symptom severity using the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R); and (c) assessed psychiatric comorbidity. After the assessment, included participants and parents completed the baseline measures and were then randomised. Within a week after completion of the baseline measures, patients allocated to the I-BA treatments started treatment, and participants allocated to TAU received a referral to their local CAMHS or paediatric primary care unit. Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram. CAMHS, Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; I-BA, internet-delivered behavioural activation.

To ensure patient safety, participants in all treatments were given brief, weekly questions about depressive symptoms during the intervention, which allowed suicidal ideation to be monitored and, if needed, assessed. If further psychiatric assessments or any preventive actions were needed, the study team referred the patient to emergency psychiatric services.

Follow-up assessments were conducted at post-treatment and after 3 months by assessors blinded to treatment allocation. Self-reported and parent-reported measures were completed online at all assessment points.

Interventions

The specific I-BA treatment protocol was developed and adapted to an online format for this study, and although it has not been otherwise evaluated in its current form, it was inspired by previous BA protocols.18 48 BA commonly provides treatment rationale and psychoeducation, activity monitoring, activity scheduling, contingency management, values and goal assessments, and skills training in problem-solving and communication skills, relaxation techniques and relapse prevention. BA also targets verbal and avoidance behaviours.49 While various BA protocols include and emphasise different components, activity monitoring and scheduling are always present.50 In our protocol, we included all of the aforementioned BA components apart from relaxation. Verbal behaviours were targeted through shifting focus. Sleep hygiene was added to the BA protocol because sleep problems are a common comorbidity of depression5 that are often addressed in face-to-face BA.51

The two I-BA treatments were delivered through a secure online platform, each consisting of eight chapters with age-appropriate texts, animations, films and various exercises delivered over 10 weeks. Each chapter took approximately 30–60 min to complete. The first four chapters introduced the most essential components of BA (ie, scheduling of values-based activities and targeting avoidance behaviours). An overview of the treatment content is presented in table 1, and sample screenshots from the intervention are presented in online supplemental figure 1.

Table 1.

An overview of the treatment content of I-BA

| Chapter | Adolescent | Parent |

| 1 | Introduction to I-BA. Psychoeducation about depression. Rationale for BA. Homework: activity monitoring. | Introduction to I-BA. Psychoeducation about depression. Rationale for BA. Learning about common parental traps. Homework: noticing one’s parental behaviours when the adolescent shows depressive behaviours. Discussing with the adolescent how to collaborate in treatment. |

| 2 | Values assessment. Set treatment goals. Homework: activity scheduling. | Facilitating and encouraging values-based activation. Communication skills part I: validating your child’s feelings. Homework: practising validating others’ and your child’s emotions, encouraging values-based activation. |

| 3 | Continued values-based activation. Psychoeducation about sleep. Homework: activity scheduling and sleep hygiene. | Spending positive time with your adolescent. Homework: suggesting positive time with your adolescent. |

| 4 | Continued values-based activation. Overcoming barriers to activation through identifying and overcoming avoidance. Homework: activity scheduling, sleep hygiene and practising overcoming avoidance. | Communication skills part II: avoiding and managing conflicts. Homework: practising conflict management. |

| 5 | Continued values-based activation. Overcome barriers to activation through shifting focus to the present situation. Homework: activity scheduling, sleep hygiene and practising shifting focus. | Taking care of yourself as a parent supporting a child with depression. Homework: taking care of yourself. |

| 6 | Continued values-based activation. Problem-solving. Homework: activity scheduling, sleep hygiene and practising problem-solving. | Collaborative problem-solving. Homework: practising collaborative problem-solving. |

| 7 | Putting it all together. Homework: activity scheduling. | Putting it all together. Homework: choosing two tasks from previously introduced skills. |

| 8 | Treatment summary. Relapse prevention. Evaluation of treatment. | Course summary. Relapse prevention. Evaluation of treatment. |

BA, behavioural activation; I-BA, internet-delivered BA.

bmjopen-2022-066357supp002.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)

Between each chapter, both adolescents and parents were assigned homework (see table 1 for details). To assist the adolescents with these assignments, a mobile application was developed to provide summaries of each chapter, instructions for homework assignments, and an activity diary to help with planning and evaluation of scheduled activities. The application included automatic prompts to log in in case of inactivity and an easily accessible individualised emergency plan.

In the therapist-guided I-BA arm, the participants had weekly asynchronous contact with a clinical psychologist via written messages within the platform. The psychologists logged in at least every other day during workdays to provide feedback, answer questions, and, if needed, prompt the participants to complete the next chapter. The therapists were recommended to spend around 20–30 min per family per week. Occasional phone calls were added when deemed necessary. The content of the self-guided I-BA programme was identical to the therapist-guided version, except that the participants did not have access to any therapist support.

Both conditions of I-BA in this study included a parallel eight-chapter course for parents (see table 1 for details), which was accessed through separate login accounts. Involving parents is a common BA adaptation for young people, and parents are taught how to encourage the young person to complete scheduled activities.50 This parental course was based on CBT strategies commonly used in parent training programmes52 such as praise and other forms of positive parental attention aiming at strengthening the relationship between caregivers and their children. The control condition was TAU. Participants randomised to TAU were referred to their local CAMHS or paediatric primary care services and were free to receive any treatment, whether psychosocial, pharmacological or a combination of both.

Patient and public involvement

Three patient representatives who had previously suffered from depression were involved in the development of I-BA, providing feedback on language and content, ensuring that the content was inclusive (eg in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity), understandable and useful.

Measures

Baseline assessment

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children (MINI-KID)53 was administered to confirm the primary diagnosis of MDD and to screen for psychiatric comorbidities. Suicide risk assessment was based on all available information, including the sections about suicidality in MINI-KID and CDRS-R collected at the inclusion assessment visit. To assess recurrent non-suicidal self-injury, the seven-item Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory for youths54 was used. Demographic data of adolescents (eg, age, gender, current and previous psychotropic medication and previous psychological treatment) were collected at the initial assessment, and data about the parents were collected through an online questionnaire.

Study design feasibility

We evaluated study take-up by calculating the average number of included participants per week. Participant retention is presented in figure 1. The specific contents of TAU in terms of type and indication for medication, number of visits, type of psychological or psychosocial treatment and number of sessions, and number of sessions of other potential interventions were collected from each participant’s official medical records and by interviewing the families after the 3-month follow-up assessment.

Acceptability of I-BA

The average number of completed chapters for adolescents and their parents was documented. Adolescents who completed less than half (<4) of the I-BA chapters were defined as having discontinued treatment.

To measure treatment credibility, four questions were administered to all adolescents and their parents at week 3: (1) How much did they believe the treatment suited adolescents with depression?; (2) How much did they believe the treatment would help them?; (3) If and to what extent would they recommend this treatment to a friend with depression? and (4) How much improvement did they expect from the treatment? The total range of this scale was 4–20, with higher values representing higher credibility.

Treatment satisfaction was assessed with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire at post-treatment (adolescent and parent version; total range 8–32, with higher values indicating higher satisfaction).55 All adverse events, that is, untoward medical occurrences after exposure to the intervention (but not necessarily caused by the intervention) were communicated by participants (eg, via text messages, phone calls, at follow-up visits) and documented by the trial coordinator (RG) until 3-month follow-up. Adverse events were also assessed with the Negative Effects Questionnaire with 20 items (NEQ-20) administered at post-treatment and at 3-month follow-up (adolescent and parent version; total range 0–80, with higher values representing more reported adverse events).56 NEQ has been developed to investigate negative effects of psychological treatments, such as experiencing unpleasant feelings during treatment and not believing that things can improve. Because we did not systematically ask about adverse events, the administration of NEQ at predefined time points increased the likelihood of identifying adverse events. Furthermore, NEQ includes treatment-related questions like lacking confidence in one’s treatment or having unpleasant memories resurface (these factors are often not reported spontaneously).

Therapist time was logged automatically in the treatment platform. The platform registered how many minutes the therapist spends on each participant (including reading their responses and providing feedback). The entire time a therapist had a certain participant ‘open’ was included, for example, navigating between worksheets, answering messages, etc. If therapists were interrupted while working, they could edit the amount of time registered to a more accurate sum. Time spent on phone calls with adolescents and their parents was logged manually by the therapist. These two indicators, that is, therapist time in the platform and time spent on phone calls, were combined as a measure of therapist time per family and chapter.

Working alliance was assessed with the Working Alliance Inventory-6 items (WAI-6) at 3 weeks and post-treatment (adolescent and parent versions).57

Clinical outcomes

The CDRS-R (primary measure of clinical efficacy) is a semistructured clinical interview used to assess depressive symptom severity in children (total range 17–113 with higher values representing more depressive symptoms).58 All interviews with CDRS-R were audio-recorded.

Other clinician-rated measures included the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)59 and Clinical Global Impression Scale–Severity and Improvement (CGI-S and CGI-I).60 CGI-I was only conducted at post-treatment and the 3-month follow-up. Treatment response was defined as a CGI-I rating of 1 or 2 at the 3-month follow-up. Percentages that still fulfilled MDD diagnosis at 3-month follow-up will be presented.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ, adolescent and parent versions, total range 0–26 with higher values representing more symptoms).61 62 Impaired functioning due to depression was measured with the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS, adolescent and parent versions, total range 0–40 with higher values indicating greater impairment).63 Anxiety symptoms were assessed by the anxiety subscales in the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale–Short version (RCADS-S, adolescent and parent versions; total range 0–45 with higher values indicating worse outcome).64 KIDSCREEN-10 Index (adolescent and parent versions, total range 10–50 with higher values indicating better quality of life) was used to measure general health-related quality of life.65 Difficulties with sleep were measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI, adolescent version, total range 0–28 with higher values indicating a worse outcome)66 and irritability by Affective Reactivity Index (ARI, adolescent version, total range 0–12 with higher values indicating worse outcome).67

Behavioral Activation of Depression Scale Short Form (BADS-SF) is a self-report measure developed to measure the proposed mediators of BA, that is, activation and avoidance.68 Total range of the scales is 0–54 with higher values indicating high activation and low avoidance. Need for further treatment was assessed at 3-month follow-up with a non-validated single-item questionnaire (adolescent and parent versions). ISI, ARI and BADS were administered to adolescents only.

WAI, BADS-SF and need for further treatment were included in this study to test for feasibility only and will be presented in the online supplemental material. No changes were made to outcomes after the trial commenced. More information on measures is available in online supplemental file 1.

bmjopen-2022-066357supp001.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Block randomisation, with five random sets of blocks of three and six, respectively, was created by an independent clinician using an online service (http://www.random.org). Once a participant was included, the independent clinician opened a sealed opaque envelope revealing a numbered paper with treatment allocation.

Post-treatment and 3-month follow-up assessments were conducted by four clinical psychologists blinded to treatment allocation. In the event of blinding, a new assessor rerated the recording. Blinding integrity was measured at each assessment point by asking blinded assessors to guess each participant’s group allocation and indicate the reasons for their conjecture (eg, totally random guess, impression of improvement, etc).69

Analytical methods

Data on trial feasibility (eg, study take-up, participant retention and content of TAU) and data on acceptability (eg, adherence, credibility, satisfaction and adverse events) were analysed using descriptive statistics.

We used linear mixed regression models to estimate within-group effects for all continuous clinical outcome measures. All models included a fixed effect of time and a random intercept for participant effect. In contrast to standard modelling of repeated data, where listwise deletion is used for all cases with missing data at any time point,70 the linear mixed model estimates effects using all available observations at all time points. The linear mixed model has been shown to yield reliable estimates in various types of missing data patterns.71 Time was treated as a continuous variable from 0 to 2 (pretreatment, post-treatment and 3-month follow-up) because there were 3 months between each time point. Alpha levels (two tailed) were set to p<0.05. Within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated using the accumulated beta-coefficients (pretreatment to 3-month follow-up) from the regression models as the nominator and the pooled SD at pretreatment as the denominator.72 Additionally, the proportion of treatment responders at 3-month follow-up was calculated with intent-to-treat analysis according to prespecified criteria. Analyses were performed with SPSS V.27 and Excel V.16.

Results

Study design feasibility

Study take-up

Between 14 October 2019 and 24 April 2020, a total of 154 families were screened by telephone and 32 participants were included. Approximately one-fourth had been recommended by a healthcare provider to self-refer to the study. The recruitment rate was slow before we started advertising in local media (0.5 included per week), but higher after advertising (2.3 included per week). Although we had not reached the goal of including 45 participants after the planned 6-month recruitment period, we decided to end recruitment because we had fewer drop-outs than expected and thus enough participants to answer our feasibility questions.

Participant retention and study flow

A total of 32 adolescents from all over Sweden were recruited and randomised to therapist-guided I-BA (n=11), self-guided I-BA (n=10) or TAU (n=11). Table 2 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at baseline. Figure 1 shows the study flow. Two participants dropped out of the study. Both drop-outs were dissatisfied that they had been allocated to TAU and did not want to attend their appointments within regular healthcare or continue as study participants. At post-treatment, there were no missing data on the primary outcome measure CDRS-R in therapist-guided I-BA, one in self-guided and two in TAU. At 3-month follow-up, there were missing data for one participant in therapist-guided, three in self-guided and two in TAU. The final 3-month follow-up assessment occurred on 15 October 2020.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the total sample and for each group

| Total (n=32) | Therapist-guided I-BA (n=11) | Self-guided I-BA (n=10) | TAU (n=11) | |

| Age, mean (SD), min–max | 15.4 (1.6), 13–17 | 14.6 (1.2), 13–17 | 15.1 (1.8), 13–17 | 16.5 (1.3), 14–17 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 19 (59) | 6 (55) | 7 (70) | 6 (55) |

| Male | 13 (41) | 5 (45) | 3 (30) | 5 (45) |

| Main contact person, mothers, n (%) | 30 (94) | 9 (82) | 10 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Education of contact person | ||||

| Elementary school | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| High school | 3 (9%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (9%) |

| Higher education <2 years | 5 (16%) | 1 (9%) | 4 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Higher education >2 years | 21 (66%) | 7 (64%) | 5 (50%) | 9 (82%) |

| Postgraduate degree | 2 (6%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Comorbidity*, n (%) | ||||

| None | 6 (19) | 1 (9) | 2 (20) | 3 (27) |

| One diagnosis | 12 (38) | 5 (45) | 3 (30) | 4 (36) |

| Two or more diagnoses | 14 (44) | 5 (45) | 5 (45) | 4 (36) |

| Anxiety disorder/s* | 23 (72) | 7 (64) | 8 (80) | 8 (73) |

| ADHD/ASD | 5 (16) | 3 (27) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) |

| Current use of antidepressants, n (%) | 2 (6) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Risk of suicide† | ||||

| No suicidal ideation | 3 (9%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

| Low risk | 16 (50%) | 6 (55%) | 4 (40%) | 6 (55%) |

| Moderate risk | 13 (41%) | 4 (36%) | 6 (60%) | 3 (27%) |

| High risk | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

*Including all anxiety disorders in MINI-KID.

†According to the definitions of suicidality used in MINI-KID.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; I-BA, internet-delivered behavioural activation; MINI-KID, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children; TAU, treatment as usual.

Treatment content in TAU

Five of the referrals were sent to primary care and six to CAMHS. Two participants in TAU never attended the first visits at the clinic to which they were referred. Five out of 11 participants allocated to TAU had started an intervention by post-assessment. This number had increased to nine at the 3-month follow-up. According to interviews with families and medical records at the 3-month follow-up, patients in TAU received pharmacological (n=1), psychological (n=1), supportive (n=1) or a combination of these interventions (n=4), as well as psychiatric (n=1) or neuropsychiatric assessment and medications (n=1) during the study. Details on TAU content are presented in online supplemental table 1A,B.

bmjopen-2022-066357supp003.pdf (102.3KB, pdf)

Acceptability of I-BA

Treatment adherence

The average number of completed chapters at post-treatment was 7.5 (SD 1.0) for adolescents and 7.4 (SD 1.3) for parents in therapist-guided I-BA, and 5.4 (SD 2.5) for adolescents and 5.9 (SD 2.8) for parents in self-guided I-BA. Eight adolescents (73%) and eight parents (73%) in therapist-guided I-BA, and three adolescents (30%) and four parents (40%) in self-guided I-BA had completed all eight chapters by the end of treatment. Zero participants in therapist-guided I-BA, and three in self-guided I-BA, discontinued treatment.

Credibility and satisfaction

Average treatment credibility was 14.3 (SD 2.7) for therapist-guided I-BA (n=11), 14.1 (SD 3.9) for self-guided I-BA (n=9) and 11.1 (SD 3.4) for TAU (n=8). Average treatment satisfaction at post-treatment was 24.7 (SD 5.33) for therapist-guided I-BA (n=11), 21.3 (SD 6.8) for self-guided I-BA (n=9) and 17.7 (SD 6.3) for TAU (n=10).

Adverse events and negative effects

From baseline to 3-month follow-up, 17 adverse events were documented each in therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA and 25 in TAU. None of the adverse events were assessed as serious. The most commonly reported negative effect on NEQ in the I-BA-groups, reported by a total of five participants from both groups, was not trusting the treatment and not feeling that the treatment produced any results. In TAU, the most commonly reported negative effects on NEQ were feeling that the treatment did not produce any results, feeling that the treatment was not motivating and not always understanding the treatment.

Therapist time (therapist-guided I-BA)

The average therapist time per family and chapter was 23 min (SD=6 min). This measure includes both messages in the platform and occasional telephone calls relating to the treatment. Mean average telephone time per participant was 3.6 min (SD=7.1) and median was 0.0 min (IQR: 6.0 min) throughout the treatment.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcome measure

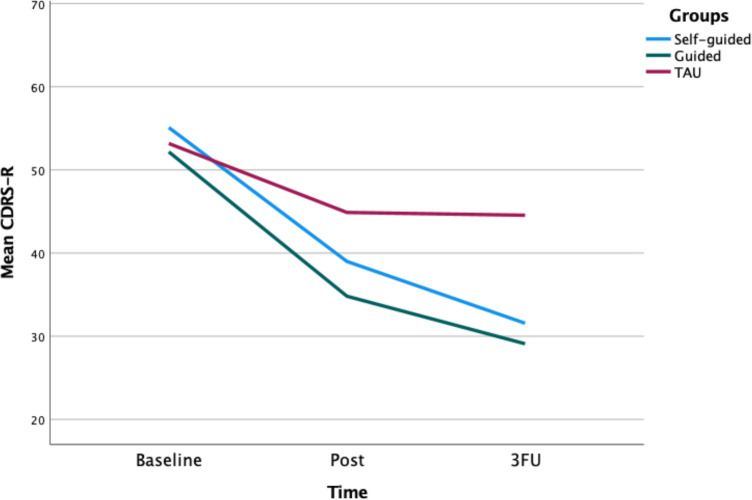

A series of linear mixed models showed a significant decrease in blinded assessor-rated depressive symptoms (CDRS-R) over time for therapist-guided I-BA (B=−11.3, p<0.001, 95% CI −14.9 to −7.7) and self-guided I-BA (B=−10.38, p<0.001, 95% CI −13.93 to −6.82), but not for TAU (B=−4.40, p=0.077, 95% CI −9.33 to 0.52, p>0.05) (table 3 and figure 2). Within-group Cohen’s d was 2.43 (CI 1.66 to 3.20) for therapist-guided I-BA, 2.23 (CI 1.47 to 3.00) for self-guided I-BA and 0.95 (CI −0.11 to 2.01) for TAU.

Table 3.

Means (SD) for the three assessment points presented separately for the three groups

| Measure | Therapist-guided I-BA (n=11) | Self-guided I-BA (n=10) | TAU (n=11) |

| Mean (SD)* | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Clinician-rated | |||

| CDRS-R | |||

| Pretreatment | 52.2 (9.4) | 55.1 (10.2) | 53.2 (9.0) |

| Post-treatment | 34.8 (10.1) | 39.0 (12.0) | 44.9 (10.0) |

| Three-month follow-up† | 29.1 (10.1) | 31.6 (11.0) | 44.6 (13.6) |

| Child and parent rated | |||

| SMFQ-A | |||

| Pretreatment | 13.6 (5.4) | 13.9 (6.5) | 16.8 (6.2) |

| Post-treatment | 6.2 (5.6) | 4.9 (5.5) | 12.9 (7.8) |

| Three-month follow-up | 4.6 (4.5) | 8.3 (6.0) | 9.6 (5.8) |

| SMFQ-P | |||

| Pretreatment | 11.6 (5.8) | 12.5 (5.9) | 15.2 (4.1) |

| Post-treatment | 7.6 (5.0) | 5.5 (4.7) | 11.2 (7.2) |

| Three-month follow-up | 5.7 (4.3) | 5.0 (3.6) | 9.3 (5.0) |

| WSAS-A | |||

| Pretreatment | 17.9 (8.7) | 13.8 (7.0) | 16.1 (5.5) |

| Post-treatment | 12.0 (6.6) | 9.7 (11.2) | 15.8 (10.6) |

| Three-month follow-up | 7.0 (5.4) | 5.6 (7.9) | 12.9 (10.0) |

*Observed means.

†Primary endpoint.

CDRS-R, Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised; I-BA, internet-delivered behavioural activation; SMFQ-A/P, Short version of Mood and Feeling Questionnaire, Adolescent and Parent version; TAU, treatment as usual; WSAS-A, Work and Social Adjustment Scale–Adolescent version.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the CDRS-R total score across the three assessment points. Primary endpoint is the 3-month follow-up (FU). CDRS-R, Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised; TAU, treatment as usual.

Secondary outcome measures

Descriptive statistics on secondary outcome measures are reported in table 3 and online supplemental table 2. A series of linear mixed models showed significant decreases in self-rated depressive symptoms (SMFQ-A) for all three groups: therapist-guided I-BA (B=−4.4, p<0.001, 95% CI −6.2 to −2.6), self-guided I-BA (B=−3.39, p<0.05, 95% CI −6.48 to −0.30) and TAU (B=−4.04, p=0.001, 95% CI −6.22 to −1.86). Within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were 1.45 for therapist-guided I-BA, 1.12 for self-guided I-BA and 1.34 for TAU.

bmjopen-2022-066357supp004.pdf (141.7KB, pdf)

Significant decreases were shown for self-rated impaired functioning (WSAS-A) for therapist-guided I-BA (B=−5.24, p<0.001, 95% CI −7.65 to −2.82) and self-guided I-BA (B=−3.58, p<0.01, 95% CI −6.08 to −1.10), but not for TAU (B=−1.81, p=0.163, 95% CI −4.43 to 0.80). Within-group Cohen’s d was 1.47 for therapist-guided I-BA, 1.00 for self-guided I-BA and 0.51 for TAU.

Significant decreases were shown for parent-rated depressive symptoms (SMFQ-P) for therapist-guided I-BA (B=−2.83, p<0.01, 95% CI −4.31 to −1.34), self-guided I-BA (B=−3.75, p<0.01, 95% CI −5.65 to −1.85) and for TAU (B=−3.29, p<0.01, 95% CI −5.17 to −1.42). Within-group Cohen’s d was 1.05 for therapist-guided I-BA, 1.40 for self-guided I-BA and 1.22 for TAU.

Of the secondary measures, CGAS, ISI and KIDSCREEN-10 (adolescent and parent rated) showed significant improvements in all three groups. Remaining secondary measures (CGI-S, RCADS-S-A/P, WSAS-P, ARI) showed significant improvements in some, but not all groups. Means and within-group effects for CGAS, CGI-S, RCADS-S-A/P, KIDSCREEN-10-A/P, ISI, ARI and WSAS-P are presented in online supplemental table 3.

bmjopen-2022-066357supp005.pdf (147.6KB, pdf)

Treatment response (CGI-I)

At the primary endpoint, seven participants (64%) in therapist-guided I-BA, six participants (60%) in self-guided I-BA and four in TAU (36%) were classified as treatment responders according to the CGI-I. At the 3-month follow-up, 78%, 67% and 56% no longer fulfilled criteria for MDD in therapist-guided I-BA, self-guided I-BA and TAU, respectively.

Blinding integrity

Blinding was unintentionally broken at two follow-up assessments (one in therapist-guided at post-treatment and one in TAU at 3-month follow-up). At post-treatment, the assessors’ guesses were correct 48.2% of the time, and at 3-month follow-up, 61.5% of the time.

Discussion

This feasibility trial, where adolescents with mild-to-moderate depression were randomised to therapist-guided I-BA, self-guided I-BA or TAU, evaluated the feasibility of the study design, the acceptability of the treatments and provided preliminary clinical efficacy data.

Most participants screened positive for two or more diagnoses according to MINI-KID, indicating that comorbidity was common in this sample. The pace of recruitment was initially slow but improved substantially when we placed advertisements in local media. Drop-out of participants was low and data loss acceptable. It was possible to successfully refer all participants randomised to TAU to their local primary care or CAMHS, and all but one patient received treatment in these services, though the start of treatment was often delayed. As expected, TAU was a heterogeneous condition; participants received pharmacological, psychological or combination of both interventions. Implications for a future large-scale RCT include the importance of broad recruitment strategies, such as nationwide participant inclusion and close collaboration with clinical services to ensure that participants randomised to TAU have access to treatment as soon as possible.

Overall, both I-BA groups were rated as more credible and more satisfactory than TAU. However, most families had probably hoped for one of the I-BA groups, which could have been a factor in the lower ratings for the TAU group. Furthermore, both I-BA treatments started immediately after randomisation, while some participants in TAU had to wait to start treatments at their local clinics. This inherent difference between the interventions and potential dissatisfaction with treatment availability in TAU may have influenced clinical outcomes. Adherence was lower in the self-guided I-BA group, but clinical outcomes were similar overall. Whether self-guided I-BA is a viable treatment alternative will be answered in a larger RCT. The advantages of self-guided interventions are obvious in terms of low costs and scalability.

Previous research has indicated that ICBT is efficacious for adolescent depression.33 34 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first trial on online-delivered BA for this age group. Our results suggest that delivering BA online, with or without therapist support, could also be a feasible and potentially effective way of treating depression in adolescents. We found large within-group effects on clinician-rated depressive symptoms for both I-BA groups. These results are consistent with previous trials, where face-to-face BA has been found to be potentially effective for adolescent depression.17–19 In a small RCT, similar results were found for face-to-face BA and evidence-based practice for depression,18 while in the current trial, we found lower effect sizes and response rates in the TAU group. The encouraging results of this feasibility study should nevertheless be considered preliminary, and the relative efficacy of therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA will need to be established in a definitive RCT.

This trial has several strengths, including a randomised controlled design, the use of blinded assessors, high treatment adherence in the I-BA groups, the use of an ecologically valid control group and the careful recording of adverse events. Furthermore, the contents of TAU were carefully assessed and reported. This study also has some limitations. First, while TAU ensures patient safety and allows for comparison with current clinical practice, it is a heterogeneous condition,73 and the nature and quality of TAU will affect results of the larger RCT.74 Thus, a detailed description of TAU is important for interpreting the results as well as for enabling replication. In this study, we collected information about the content of TAU through medical records and interviewing parents. Both methods are subject to uncertainty, but showed good agreement with each other. Second, generalisability of the results to other settings and locations might be limited. Usual care for adolescents with depression might differ among the regions in Sweden and among different countries and healthcare systems. Third, although clinic referrals were accepted in this trial, all included patients were self-referred, and thus may be less complex and more motivated for ICBT than a clinically referred sample. However, about one-fourth of participants self-referred to the study upon recommendation by a healthcare provider, and all included patients were diagnosed with MDD. Fourth, despite our best efforts, blinded assessors correctly guessed group allocation more often than they would have by chance. Additional measures, such as employing external blinded assessors who are fully unaware of study aims and hypotheses,75 might be needed to improve blinding.

Conclusions

Both therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA are acceptable and potentially efficacious treatments for adolescents with depression, and TAU is a reasonable and ethically acceptable control condition. In conclusion, it should be feasible to conduct a fully powered RCT comparing therapist-guided and self-guided I-BA with TAU, in order to evaluate their relative efficacy and cost-effectiveness in adolescents with mild-to-moderate depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all adolescents and their parents who participated in this study. Thanks also to psychology student Emilia Serlachius and to a former patient of author RG for their valuable input on I-BA treatments. Thanks to colleague Vera Wachtmeister for careful proofreading of the treatment content. The authors are also grateful to all clinicians for assisting with assessments and data collection, and to Semantix that carefully read and proofread this manuscript. This work used the BASS platform for data collection from the eHealth Core Facility at Karolinska Institutet, which is supported by the Strategic Research Area Healthcare Science (SFO-V).

Footnotes

@MataixCols, @fabianlenhard, @evaserlachius, @SVigerland

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published. Author name 'Rebecca Andersson' has been updated.

Contributors: JA, DM-C, FL, EH, ES and SV designed the study. RG wrote the protocol, was the project manager and produced the treatment content with input from JA, ES and SV. RG, JA and SV provided the I-BA treatments. Author RG undertook the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript in collaboration with JA. All authors (RG, JA, DM-C, FL, EH, CM, HS, MB, ES and SV) contributed to and have approved the final manuscript. ES acts as guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Kavli Trust (grant number 4-3124, 2018) and the Frimurare Barnhuset Trust in Stockholm (2019).

Competing interests: DM-C reports personal fees from UpToDate, which was not involved in this work.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The data are pseudonymised according to national (Swedish) and European Union legislation, and cannot be anonymised and published in an open repository. Participants in the trial have not consented for their data to be shared with other international researchers for research purposes.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (reference number: 2019/03235). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merikangas KR, He J-P, Brody D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics 2010;125:75–81. 10.1542/peds.2008-2598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daly M. Prevalence of depression among adolescents in the U.S. from 2009 to 2019: analysis of trends by sex, Race/Ethnicity, and income. J Adolesc Health 2022;70:496–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He J-P, et al. Major depression in the National comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:37–44. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Orchard F, Pass L, Marshall T, et al. Clinical characteristics of adolescents referred for treatment of depressive disorders. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2017;22:61–8. 10.1111/camh.12178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2012;35:1–14. 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jonsson U, Bohman H, Hjern A, et al. Subsequent higher education after adolescent depression: a 15-year follow-up register study. Eur Psychiatry 2010;25:396–401. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jonsson U, Bohman H, von Knorring L, et al. Mental health outcome of long-term and episodic adolescent depression: 15-year follow-up of a community sample. J Affect Disord 2011;130:395–404. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, et al. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:56–63. 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA 1999;281:1707–13. 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neufeld SAS, Dunn VJ, Jones PB, et al. Reduction in adolescent depression after contact with mental health services: a longitudinal cohort study in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:120–7. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30002-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do M-CT, et al. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2017;46:11–43. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Socialstyrelsen . National guidelines for depression and anxiety disorder care. Stockholm: The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopkins K, Crosland P, Elliott N, et al. Diagnosis and management of depression in children and young people: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h824–h24. 10.1136/bmj.h824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S. Behavioral activation treatment for depression: returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2006;8:255–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ritschel LA, Ramirez CL, Jones M, et al. Behavioral activation for depressed teens: a pilot study. Cogn Behav Pract 2011;18:281–99. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ritschel LA, Ramirez CL, Cooley JL, et al. Behavioral activation for major depression in adolescents: results from a pilot study. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2016;23:39–57. 10.1111/cpsp.12140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCauley E, Gudmundsen G, Schloredt K, et al. The adolescent behavioral activation program: adapting behavioral activation as a treatment for depression in adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45:291–304. 10.1080/15374416.2014.979933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pass L, Lejuez CW, Reynolds S. Brief behavioural activation (brief Ba) for adolescent depression: a pilot study. Behav Cogn Psychother 2018;46:182–94. 10.1017/S1352465817000443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Psychological Association (APA) . Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts, 2019. Available: https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline [Accessed 03 May 2022].

- 21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Depression in adults: treatment and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2022 [NICE Guideline [NG222]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222 [Accessed 01 May 2022]. [PubMed]

- 22. Dimidjian S, Barrera M, Martell C, et al. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011;7:1–38. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, et al. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:909–22. 10.1037/a0013075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, et al. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:295–304. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:658–70. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2006;132:132–49. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tindall L, Mikocka-Walus A, McMillan D, et al. Is behavioural activation effective in the treatment of depression in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Psychother 2017;90:770–96. 10.1111/papt.12121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJA, et al. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depression: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:583–616. 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Merikangas KR, He J-ping, Burstein M, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National comorbidity Survey-Adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Essau CA. Frequency and patterns of mental health services utilization among adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Depress Anxiety 2005;22:130–7. 10.1002/da.20115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vigerland S, Lenhard F, Bonnert M, et al. Internet-Delivered cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;50:1–10. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Topooco N, Berg M, Johansson S, et al. Chat- and Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy in treatment of adolescent depression: randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open 2018;4:199–207. 10.1192/bjo.2018.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Topooco N, Byléhn S, Dahlström Nysäter E, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy blended with synchronous chat sessions to treat adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13393–e93. 10.2196/13393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Păsărelu C-R, Dobrean A, Andersson G, et al. Feasibility and clinical utility of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered rational emotive and behavioral intervention for adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Internet Interv 2021;26:100479–79. 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Makarushka MM. Efficacy of an Internet-based intervention targeted to adolescents with subthreshold depression. University of Oregon, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sethi S, Campbell AJ, Ellis LA. The use of computerized self-help packages to treat adolescent depression and anxiety. J Technol Hum Serv 2010;28:144–60. 10.1080/15228835.2010.508317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sandín B, García-Escalera J, Valiente RM, et al. Clinical utility of an internet-delivered version of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents (iUP-A): a pilot open trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8306. 10.3390/ijerph17228306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmitt JC, Valiente RM, García-Escalera J, et al. Prevention of depression and anxiety in subclinical adolescents: effects of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered CBT program. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:5365. 10.3390/ijerph19095365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Karyotaki E, Efthimiou O, Miguel C, et al. Internet-Based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a systematic review and individual patient data network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:361–71. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pennant ME, Loucas CE, Whittington C, et al. Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther 2015;67:1–18. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bennett SD, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, et al. Practitioner review: Unguided and guided self-help interventions for common mental health disorders in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2019;60:828–47. 10.1111/jcpp.13010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vigerland S, Ljótsson B, Thulin U, et al. Internet-Delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2016;76:47–56. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jolstedt M, Wahlund T, Lenhard F, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of therapist-guided Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for paediatric anxiety disorders: a single-centre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:792–801. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30275-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. American Psychiatric Publishing . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arjadi R, Nauta MH, Bockting CLH. Acceptability of Internet-based interventions for depression in Indonesia. Internet Interv 2018;13:8–15. 10.1016/j.invent.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dhand N, Khatkar M. Statulator, 2014. Available: www.statulator.com [Accessed 15 Oct 2022].

- 48. Pass L, Hodgson E, Whitney H, et al. Brief behavioral activation treatment for depressed adolescents delivered by nonspecialist clinicians: a case illustration. Cogn Behav Pract 2018;25:208–24. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kanter JW, Manos RC, Bowe WM, et al. What is behavioral activation? A review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:608–20. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martin F, Oliver T. Behavioral activation for children and adolescents: a systematic review of progress and promise. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;28:427–41. 10.1007/s00787-018-1126-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Barlow DH. Clinical Handbook of psychological disorders: a step-by-step treatment manual. New York: Guilford Publications, 2021: 6. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Webster-Stratton C, Herman KC. The impact of parent behavior-management training on child depressive symptoms. J Couns Psychol 2008;55:473–84. 10.1037/a0013664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, et al. Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:313–26. 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2001;23:253–63. 10.1023/A:1012779403943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2:197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rozental A, Kottorp A, Forsström D, et al. The negative effects questionnaire: psychometric properties of an instrument for assessing negative effects in psychological treatments. Behav Cogn Psychother 2019;47:559–72. 10.1017/S1352465819000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. J Couns Psychol 1989;36:223–33. 10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Poznanski E, Mokros H. Children’s depression rating scale-revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:1228–31. 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007;4:28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, et al. The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1995;5:237–49. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jarbin H, Ivarsson T, Andersson M, et al. Screening efficiency of the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) and short mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) in Swedish help seeking outpatients. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230623–e23. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jassi A, Lenhard F, Krebs G, et al. The work and social adjustment scale, youth and parent versions: psychometric evaluation of a brief measure of functional impairment in young people. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2020;51:453–60. 10.1007/s10578-020-00956-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ebesutani C, Reise SP, Chorpita BF, et al. The revised child anxiety and depression Scale-Short version: scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychol Assess 2012;24:833–45. 10.1037/a0027283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Rajmil L, et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents' well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1487–500. 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297–307. 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, et al. The affective reactivity index: a Concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012;53:1109–17. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Manos RC, Kanter JW, Luo W. The behavioral activation for depression scale-short form: development and validation. Behav Ther 2011;42:726–39. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Başoğlu M, Marks I, Livanou M, et al. Double-blindness procedures, rater blindness, and ratings of outcome. observations from a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:744–8. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200078011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Muth C, Bales KL, Hinde K, et al. Alternative models for small samples in psychological research: applying linear mixed effects models and generalized estimating equations to repeated measures data. Educ Psychol Meas 2016;76:64–87. 10.1177/0013164415580432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lane P. Handling drop-out in longitudinal clinical trials: a comparison of the LOCF and MMRM approaches. Pharm Stat 2008;7:93–106. 10.1002/pst.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol Methods 2009;14:43–53. 10.1037/a0014699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson KW, et al. Usual and unusual care: existing practice control groups in randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions. Psychosom Med 2011;73:323–35. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Watts SE, Turnell A, Kladnitski N, et al. Treatment-as-usual (tau) is anything but usual: a meta-analysis of CBT versus tau for anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord 2015;175:152–67. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mataix-Cols D, Andersson E. Ten practical recommendations for improving blinding integrity and reporting in psychotherapy trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:943–4. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-066357supp002.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-066357supp001.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-066357supp003.pdf (102.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-066357supp004.pdf (141.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-066357supp005.pdf (147.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The data are pseudonymised according to national (Swedish) and European Union legislation, and cannot be anonymised and published in an open repository. Participants in the trial have not consented for their data to be shared with other international researchers for research purposes.