Abstract

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common complication of surgery, increasing healthcare costs and hospital stay. Chlorhexidine (CHX) and povidone-iodine (PVI) are used for skin antisepsis, minimising SSIs. There is concern that resistance to topical biocides may be emergeing, although the potential clinical implications remain unclear. The objective of this systematic review was to determine whether the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of topical preparations of CHX or PVI have changed over time, in microbes relevant to SSI. We included studies reporting the MBC of laboratory and clinical isolates of common microbes to CHX and PVI. We excluded studies using non-human samples and antimicrobial solvents or mixtures with other active substances. MBC was pooled in random effects meta-analyses and the change in MBC over time was explored using meta-regression. Seventy-nine studies were included, analysing 6218 microbes over 45 years. Most studies investigated CHX (93%), with insufficient data for meta-analysis of PVI. There was no change in the MBC of CHX to Staphylococci or Streptococci over time. Overall, we find no evidence of reduced susceptibility of common SSI-causing microbes to CHX over time. This provides reassurance and confidence in the worldwide guidance that CHX should remain the first-choice agent for surgical skin antisepsis.

Subject terms: Antimicrobials, Clinical microbiology, Bacterial infection

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common and costly complication of surgery1,2, occurring in approximately 5% of all surgical interventions3. They represent an important economic burden across all surgical specialties4, increasing hospital inpatient stay time and adversely affecting patient’s mental and physical health4. The use of skin antisepsis prior to surgery significantly reduces the risk of SSI and consequently, post-operative morbidity and mortality5–7.

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococci spp. are commonly implicated microbes in SSI, along with Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli8. To reduce the risk of SSI, the World Health Organization (WHO)7, United States of America Centres for Disease Control (CDC)9 and United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)10 recommend the application of topical chlorhexidine (CHX) in alcohol to the planned operative site, for skin antisepsis. CHX in an alcoholic solvent has been shown to halve the risk of SSI following clean11, contaminated12,13 and dirty surgery when compared to other antiseptics such as povidone-iodine (PVI).

CHX is a biguanide compound, utilised both as a broad spectrum antimicrobial and topical antiseptic14. By binding to the cell membrane and cell wall of bacteria, at lower concentrations it has a bacteriostatic effect by displacing the cations and destabilising the cell wall. At higher concentrations there is a complete loss of cellular structural integrity, having a bactericidal effect15. PVI is an iodophor; a chemical complex between a water soluble povidone polymer and iodine16. When dissolved in water, iodine is released, penetrating microorganisms and oxidising proteins, nucleotides and fatty acids17 causing cell death. Both PVI and CHX are active against gram positive and negative bacteria, fungi and viruses16,18.

There are growing fears that as antiseptic use increases, sensitivity may reduce and resistance emerge19. This is particularly concerning given the accelerating global antibiotic resistance crisis20. Multiple bacteria have shown reduced sensitivity (perhaps even resistance) to CHX, particularly through the multidrug resistance efflux protein qacA19. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) samples with qacA/B genes showed persistent MRSA carriage despite de-colonisation therapy21. Not only is the presence of reduced sensitivity concerning, but the presence of resistance conferring genes seems to be increasing annually22. PVI resistance has been less commonly reported23 although this might be secondary to the multimodal effect of iodine on microbes23 or otherwise. Overall, the current state of microbial sensitivity to CHX and PVI remains unclear.

The aim of this review is to summarise the sensitivity profiles of skin microbes (relevant to surgical site infection) to CHX and PVI, and explore how these have changed over time.

Methods

This review was designed and conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews24, the protocol was published in the PROSPERO databased (CRD42021241089) and the report has been authored in accordance with the PRISMA checklist25.

Types of studies

We included all studies which reported the resistance of microbes to CHX or PVI based topical biocides derived from human samples. There were no language restrictions. We excluded case reports and studies which used antimicrobial solvents (e.g., alcohol) or mixtures of antiseptics (e.g. chlorhexidine mixed with cetrimide).

Search strategy

The NICE Healthcare Databases (hdas.nice.org.uk) was searched according to Appendix 1 (Supplementary Materials). The medRxiv and bioRxiv preprint archives were searched with the same strategy using the R package medrxivr26. This yielded 582 hits in PubMed, 720 in Embase, 993 in Web of Science and 896 in CINAHL. After de-duplication, there were 2318 unique citations which were screened (Fig. 1). A further 3 articles were found by manual searching of these articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart—the following studies were excluded from the systematic review: (1) no MBC calculated, (2) use of biocide and alcohol mixtures, (3) use of non-human bacteria, (4) use of dental preparations of biocides, (5) no data on the strength of biocide used.

Study selection

Two review authors (RA and VHD) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, in accordance with the eligibility criteria. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were obtained and again independently assessed by the same authors. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with RGW and CJ.

Data extraction

Two review authors (RA and VHD) independently double extracted data. The colony was the unit of analysis. Where data was missing or unclear, the corresponding author was contacted by email and if no reply was received, these values were estimated from the available data27.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest was the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). MBC was chosen over the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) as a measure of susceptibility because it is generally felt to be a more appropriate for topical antiseptics15,28. We were interested in deriving a pooled estimate of the MBC for different species to understand how this may have changed over time.

Methodological quality assessment

The risk of bias was not assessed because there are no validated tools available for studies of this nature and the study selection process ensured that only the highest quality research was included.

Missing data

After back-calculating some parameters, the overall rate of missing data (in the predictor variables) was 14.5%. Importantly, the variance of the mean MBC was missing at random in 36 observations (61%) and because this was required for the primary analyses, we imputed this data using chained equations29,30.

Statistical analysis

The raw data are available open-source at https://osf.io/khnb2. Using metafor31,32, 5 studies33–37 reporting the MBC of CHX for Staphylococci were identified as outliers (based on externally standardised residuals) or influential studies (based on the Cook’s distance and leave-one-out values of the test statistics for heterogeneity), and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were far outside the 95% CI of the pooled estimate, so they were excluded from the meta-analyses. Data were then analysed in Stata/MP v16 (StataCop LLC, Texas) using the meta suite. To synthesise a pooled MBC, we used a mixed-effects meta-analyses. We sub-grouped by the microbial family. To estimate change in MBC over time, we performed meta-regression for Staphylococci and Streptococci, separately. A sensitivity multivariable meta-regression for Staphylococci was performed, controlling for methicillin-resistance as a binary co-variate. The REML estimator was used throughout. To align with calls for the abolition of p-values, we minimise their use and avoid the term “statistical significance”38,39, instead focusing on how our findings may be clinically applicable and what might explain uncertainty in the estimates.

Results

Ultimately, 79 studies33–37,40–113 were included (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The details of the included studies are summarised in Table S1; readers who wish to know more detail should refer to the raw data (https://osf.io/khnb2/). The included studies originated from 24 countries. Articles were published between 1976 and 2021, although the majority (95%) were published this century. The antiseptics used included five different CHX salts (digluconate33,35,37,40,47,50,55–58,61,63,67,69,74,75,81,83,88,90,94,97,99,101,106,107,111,113, gluconate34,36,42,42,53,91,102,103,108,108,109,112, dichlorohydrate85–87, diacetate71,99 and dihydrochloride96) and povidone-iodine37,46,49,70,76,91. In total, MBC data from 6218 microbes were extracted. The microbes tested are shown in Table S2. Most samples were laboratory isolates (61%) and not multi-drug resistant (88%). The reporting standards used to establish the MBC were the according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 67%), European Committee on Antimicrobial Testing (EUCAST, 6%), German Institute for Standardisation (DIN, 5%), British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC, 3%) or International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO, 1%).

Evidence synthesis

The MBC of CHX differed significantly between the families of microbes (Fig. 2). Enterobacteriales had the highest MBC for CHX (20 mg/L [95% CI 14, 26]; I2 96%) whilst MRSA had the lowest (2 mg/L [95% CI 1, 2]; I2 94%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the mean MBC for different species and families of bacteria.

Overall, 23 studies reported the mean MBC for Staphylococci; observations based on MSSA were more common41,44,51,59,61,67,68,74,88,93–95,102,106,107,110–113 than MRSA34,35,37,50,67,68,80,90,93,106,110,113. The pooled mean MBC of CHX for Staphylococci was 6 mg/L (95% CI 3, 9; I2 99%). Meta-regression showed no change in the MBC of CHX for Staphylococci over time (β 0.12 [− 1.13, 1.37]; I2 99%; Fig. 3). When controlling for resistance to methicillin (MRSA vs MSSA), there was still no evidence of a change in the MBC over time (β 0.26 [− 0.87, 1.34]; I2 99%). Study level estimates for MSSA, MRSA and coagulase-negative Staphylococci are shown in Fig. S1.

Figure 3.

A scatterplot of study-level estimates of mean MBC over time, for Staphylococci. The size of the points corresponds to the precision (inverse variance) of the study, whereby larger bubbles are more precise (bigger and so, more accurate) studies.

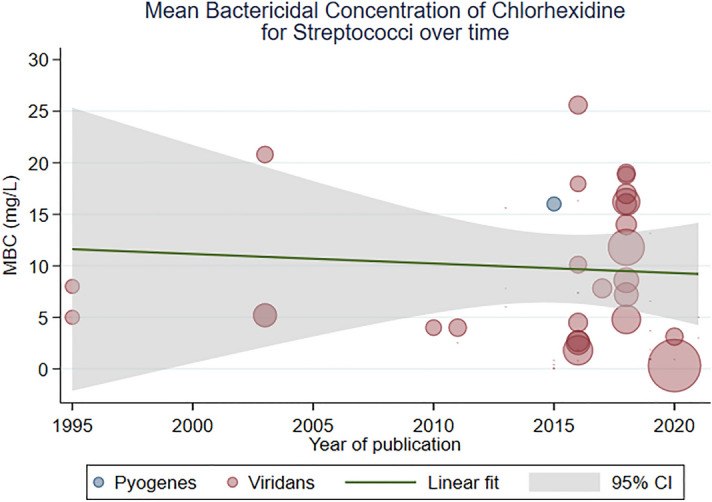

Overall, 25 studies reported the MBC of CHX for Streptococci species; observations of viridans Streptococci were most common44,45,47,48,52–54,58,66,69,75,77–79,81,82,84–86,89,99,100,103,105,106 and 1 study106 provided an estimate for Streptococcus pyogenes (Lancefield group A). The pooled mean MBC of CHX for Streptococci was 9 mg/L (95% CI 5, 12; I2 99%). Meta-regression showed that the MBC of CHX for Streptococci had not changed over time (β 0.13 [− 0.35, 0.62]; I2 97%; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A scatterplot of study-level estimates of mean MBC over time, for Streptococci. The size of the points corresponds to the precision (inverse variance) of the study, whereby larger bubbles are more precise (bigger and so, more accurate) studies.

There were insufficient data for meta-analysis of the MBC of PVI. Also, the majority of MBC data for PVI was derived from studies of Enterobacteriales, which is not a common cause of surgical site infection and so equally, not clinically relevant.

Discussion

This review summarises the evidence to-date and suggests that there has been no increase in MBC of CHX for the main SSI-causing skin microbes in recent decades. The stability of CHX susceptibility is reassuring for clinicians and policy makers alike, as it endorses current surgical guidance worldwide, which advocates topical alcoholic chlorhexidine for skin asepsis prior to surgery.

The definition of bacterial susceptibility and resistance to biocides is still a matter of debate. Most clinically relevant bacteria have defined susceptibility and resistance to systemic antibacterials based upon the MIC relative to an epidemiologically derived clinical breakpoint. However, the use of MICs is less useful in determining the efficacy of topical antiseptics biocides given the desire to induce death of specific microbes rather than inhibition. Understanding the lethality of a biocide (hence MBC) is therefore a potentially more attractive measure than MIC for topical antiseptics114. Additionally, the relevance of both MICs and MBCs with respect to biocides has been questioned15. Chlorhexidine for skin prep is used in concentrations of 5000 to 50,000 µg/mL and with MBC values ranging from 0 to 30 µg/mL, this is one thousand times greater than the apparent required concentration115.

MIC and MBC rely on attaining a steady concentration in bodily fluids as seen by the pharmacodynamics of antibiotics116. The EUCAST definition of a susceptible organism is “a microorganism is defined as susceptible by a level of antimicrobial activity associated with a high likelihood of therapeutic success”117. Therapeutic success in the context of topical CHX prior to surgery is disinfection; complete elimination of all relevant micro-organisms, except certain bacterial spores118. In the literature, there are no established clinical breakpoints for defining resistance and susceptibility of skin flora to CHX. With the available data, we look at if there is a drift in MBC over time as the next best surrogate for the development of resistance in skin flora known to cause SSI. Measurement of MIC and MBC are gained from in vitro susceptibility testing of microorganisms to topical biocides and therefore, provide little information as to the mechanism of resistance or likely clinical outcome. Therefore, our recommendation is the utilisation of epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFF) based on MBC distributions to better understand the response of bacteria to CHX in clinical practice. An analysis of ECOFF values of CHX to common bacterium, including those commonly causing SSI did not reveal a bimodal distribution, concluding that resistance is uncommon to CHX in natural populations of clinically relevant organisms88. While values above a certain cut off may be defined as a breakpoint and hence resistant, this needs to be correlated with the clinical picture. Does CHX still achieve adequate disinfection in a population of bacterium with a MBC value greater than the 95% ECOFF? Without this information, our understanding of how MBC values beyond the normal distribution impacts clinical use remains poor.

Of note, all the studies measuring MBC, the method of analysis looks at the action of a biocide over a very long period (hours). This does not represent real time clinical application of CHX, whereby topical application occurs over minutes although equally, chlorhexidine is known to penetrate the stratum corneum and exert bactericidal activity for hours (and potentially days) after application73. Therefore, we propose alternative methods of testing biocides utilising a model of topical application over minutes using clinically relevant concentrations (such as those conducted by Touzel et al.107 might be more meaningful. Furthermore, to represent clinical use, experiments must also be conducted looking at biofilm models of skin flora and the impact of CHX use on biofilms.

The majority of experiments utilising CHX and skin flora carried out in-vitro measurements using pure monospecies planktonic forms of bacteria, which does not represent the clinical environment of skin flora. Additionally, if a rise in MBC is seen, this does not prove that chlorhexidine contributes to an increase in antiseptic tolerance. We propose that future in vivo studies apply CHX topically and explore how antiseptic and antibiotic tolerance or resistance develops thereafter. Until these methods are mature, cost-effective and widely available, the MBC is the best surrogate for emergent resistance.

Limitations

Most of the included studies reported MIC rather than MBC, which meant that much data could not be synthesised. This might explain why our meta-data (for Staphylococci and Streptococci at least) disagrees with individual articles18,19,21,22. Papers also often failed to report the type and concentration of chlorhexidine used. Some papers clearly stated the year that the microbial strain was isolated, although this was often unclear and therefore the date of the paper was taken as the year of the isolate which may not adequately represent the change in MBC over time. This was also the case with location, so where possible the location of the laboratory or hospital was used as a surrogate. Isolates from a clinical setting are exposed to different selection pressures; as 61% of the microbes used were laboratory isolates as opposed to clinical isolates, it is unclear how our data can be generalised to clinical environments.

Conclusion

There has been no demonstrable change in the susceptibility of surgical site infection causing pathogens to chlorhexidine over time. A clear definition of reduced susceptibility and resistance of pathogens to biocides is needed, alongside consensus on the methods for measuring these phenomena.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

R.A. and V.H.D. contributed equally to this paper and are joint first authors. They co-designed the protocol, extracted data and co-authored the manuscript. C.J. provided clinical oversight for this study, supporting the design, advising on data extraction, analysis techniques and co-authored the manuscript. R.G.W. conceived the idea of this study, co-designed the protocol, supervised all elements of the delivery, extracted, and checked data, performed the statistical analysis and co-authored the manuscript.

Funding

Ryckie Wade is a Doctoral Research Fellow funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR, DRF-2018-11-ST2-028). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, NIHR or Department of Health.

Data availability

The raw data are available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/khnb2/). The statistical syntax are available from the senior author (RGW) upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Raiyyan Aftab and Vikash H. Dodhia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-26658-1.

References

- 1.Gibson A, Tevis S, Kennedy G. Readmission after delayed diagnosis of surgical site infection: A focus on prevention using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Am. J. Surg. 2014;207:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimlichman E, et al. Health care-associated infections. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:2039. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garner BH, Anderson DJ. Surgical site infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2016;30:909–929. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badia JM, et al. Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: A systematic review in six European countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017;96:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch T, et al. Antiseptics in surgery. Eplasty. 2010;10:e39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wade, R. G., Burr, N. E., McCauley, G., Bourke, G. & Efthimiou, O. The comparative efficacy of chlorhexidine gluconate and povidone-iodine antiseptics for the prevention of infection in clean surgery: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. (2020). (Publish Ahead of Print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.World Health Organization . Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owens CD, Stoessel K. Surgical site infections: Epidemiology, microbiology and prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;70:3–10. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berríos-Torres SI, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:784. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Great Britain) & National Guideline Centre (Great Britain). Surgical site infections: prevention and treatment (2019). [PubMed]

- 11.Wade, R. G., Burr, N. E., McCauley, G., Bourke, G. & Efthimiou, O. The comparative efficacy of chlorhexidine gluconate and povidone-iodine antiseptics for the prevention of infection in clean surgery. Ann. Surg. (2020). (Publish Ah, in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Chen S, Chen JW, Guo B, Xu CC. Preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine for the prevention of surgical site infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2020;44:1412–1424. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayoub F, Quirke M, Conroy R, Hill A. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for pre-operative skin preparation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. Open. 2015;1:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert P, Moore LE. Cationic antiseptics: Diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;99:703–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horner C, Mawer D, Wilcox M. Reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine in staphylococci: Is it increasing and does it matter? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2547–2559. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lepelletier D, Maillard JY, Pozzetto B, Simon A. Povidone iodine: Properties, Mechanisms of action, and role in infection control and Staphylococcus aureus decolonization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e00682-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00682-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachapelle J-M, et al. Antiseptics in the era of bacterial resistance: A focus on povidone iodine. Clin. Pract. 2013;10:579–592. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cieplik F, et al. Resistance toward chlorhexidine in oral bacteria—Is there cause for concern? Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:587. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kampf G. Acquired resistance to chlorhexidine—Is it time to establish an ‘antiseptic stewardship’ initiative? J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;94:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations the review on antimicrobial resistance. Rev. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee AS, et al. Impact of combined low-level mupirocin and genotypic chlorhexidine resistance on persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage after decolonization therapy: A case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:1422–1430. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeil JC, Hulten KG, Kaplan SL, Mahoney DH, Mason EO. Staphylococcus aureus infections in pediatric oncology patients: High rates of antimicrobial resistance, antiseptic tolerance and complications. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013;32:124–128. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318271c4e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eggers M. Infectious disease management and control with povidone iodine. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2019;8:581–593. doi: 10.1007/s40121-019-00260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Cochrane Collab. (2011).

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annu. Intern. Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuinness L, Schmidt L. medrxivr: Accessing and searching medRxiv and bioRxiv preprint data in R. J. Open Source Softw. 2020;5:2651. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker EM, Lowes JA. An investigation into in vitro methods for the detection of chlorhexidine resistance. J. Hosp. Infect. 1985;6:389–397. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(85)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—A practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017;17:162. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kontopantelis E, White IR, Sperrin M, Buchan I. Outcome-sensitive multiple imputation: A simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017;17:2. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0281-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW-L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 2010;1:112–125. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biagi M, Giachetti D, Miraldi E, Figura N. New non-alcoholic formulation for hand disinfection. J. Chemother. 2014;26:86–91. doi: 10.1179/1973947813Y.0000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGann P, et al. Detection of qacA/B in clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from a regional healthcare network in the eastern United States. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011;32:1116–1119. doi: 10.1086/662380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eick S, Radakovic S, Pfister W, Nietzsche S, Sculean A. Efficacy of taurolidine against periodontopathic species—An in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012;16:735–744. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knapp L, et al. The effect of cationic microbicide exposure against Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc); the use of Burkholderia lata strain 383 as a model bacterium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;115:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/jam.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koburger T, Hübner NO, Braun M, Siebert J, Kramer A. Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP-iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:1712–1719. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. Am. Stat. 2016;70:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature. 2019;567:305–307. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alotaibi SMI, et al. Susceptibility of vancomycin-resistant and -sensitive Enterococcus faecium obtained from Danish hospitals to benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine and hydrogen eroxide biocides. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017;66:1744–1751. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonelli A, et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of the decontaminant hybenx compared to chlorhexidine and sodium hypochlorite against common bacterial and yeast pathogens. Antibiotics. 2019;8:188. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arslan S, Er O, Ozbilge H, Kaya EG. In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis, BioPure MTAD, sodium hypochlorite, and chlorhexidine on Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. Saudi Med. J. 2011;32:479–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azad A, Rostamifar S, Bazrafkan A, Modaresi F, Rezaie Z. Assessment of the antibacterial effects of bismuth nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/5465439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baena-Santillan ES, et al. Comparison of the antimicrobial activity of Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx extracts, six commercial types of mouthwashes, and chlorhexidine on oral pathogenic bacteria, and the effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts and chlorhexidine on permeability of the bacterial membrane. J. Med. Food. 2020 doi: 10.1089/jmf.2019.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batubara I, Wahyuni WT, Susanta M. Antibacterial activity of Zingiberaceae leaves essential oils against Streptococcus mutans and teeth-biofilm degradation. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2016;7:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhatia M, Mishra B, Thakur A, Dogra V, Loomba PS. Evaluation of susceptibility of glycopeptide-resistant and glycopeptide-sensitive enterococci to commonly used biocides in a super-speciality hospital: A pilot study. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2017;8:199–202. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.210010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caiaffa KS, et al. KR-12-a5 is a non-cytotoxic agent with potent antimicrobial effects against oral pathogens. Biofouling. 2017;33:807–818. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2017.1370087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen H, et al. Effects of S. mutans gene-modification and antibacterial monomer dimethylaminohexadecyl methacrylate on biofilm growth and acid production. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2020;36:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, et al. Determining the susceptibility of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli strains against common disinfectants at a tertiary hospital in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4813-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conceicao T, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. Prevalence of biocide resistance genes, chlorhexidine and mupirocin non-susceptibility in Portuguese hospitals during a 31-years period (1985–2016) J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cowley NL, et al. Effects of formulation on microbicide potency and mitigation of the development of bacterial insusceptibility. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:7330–7338. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01985-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.da Silva KR, et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of Pinus tropicalis and Pinus elliottii resins and of the diterpene dehydroabietic acid against bacteria that cause dental caries. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:987. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dadpe M, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of (Ajwain) oil and chlorhexidine against oral bacteria: An study. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2018;36:357–363. doi: 10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_65_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong L, et al. Effects of sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents on Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2012;35:390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duarte B, et al. 2CS-CHXT operon signature of chlorhexidine tolerance among Enterococcus faecium isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;85:e01589–e1619. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01589-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez-Cuenca F, et al. Effect of Sub-MIC concentrations of biocides on the expression of genes coding for efflux pumps and porins in acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 (Poster P718) Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:S161–e1619. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferreira CM, da Silva Rosa OP, Torres SA, Ferreira FB, Bernardinelli N. Activity of endodontic antibacterial agents against selected anaerobic bacteria. Braz. Dent. J. 2002;13:118–122. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402002000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Filho JG, et al. Genetic and physiological effects of subinhibitory concentrations of oral antimicrobial agents on Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Microb. Pathog. 2020;150:104669. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Forbes S, Humphreys GJ, McBain AJ, Dobson CB. Transient and sustained bacterial adaptation following repeated sublethal exposure to microbicides and a novel human antimicrobial peptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5809–5817. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03364-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freire ICM, et al. Atividade antibacteriana de oleos essenciais sobre Streptococcus mutans e Staphylococcus aureus antibacterial activity of essential oils against strains of Streptococcus and Staphylococcus. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2014;16:372–377. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furi L, et al. Evaluation of reduced susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds and bisbiguanides in clinical isolates and laboratory-generated mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3488–3497. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00498-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghahramani Y, Yaghoobi F, Motamedi R, Jamshidzadeh A, Abbaszadegan A. Effect of endodontic irrigants and medicaments mixed with silver nanoparticles against biofilm formation of Enterococcus faecalis. Iran. Endod. J. 2018;13:559–564. doi: 10.22037/iej.v13i4.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graziano TS, et al. In vitro effects of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil on growth and production of volatile sulphur compounds by oral bacteria. J. Appl. Oral Sci. Rev. FOB. 2016;24:582–589. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720160044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guerin F, et al. The transcriptional repressor SmvR is important for decreased chlorhexidine susceptibility in Enterobacter cloacae complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01845-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01845-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo J, Li C. Molecular epidemiology and decreased susceptibility to disinfectants in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from intensive care unit patients in central China. J. Infect. Public Health. 2019;12:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hajifattahi F, Moravej-Salehi E, Taheri M, Mahboubi A, Kamalinejad M. Antibacterial effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Punica granatum Linn. petal on common oral microorganisms. Int. J. Biomater. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8098943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hardy K, et al. Increased usage of antiseptics is associated with reduced susceptibility in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. MBio. 2018;9:e00894-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00894-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hendry ER, Worthington T, Conway BR, Lambert PA. Antimicrobial efficacy of eucalyptus oil and 1,8-cineole alone and in combination with chlorhexidine digluconate against microorganisms grown in planktonic and biofilm cultures. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. JAC. 2009;64:1219–1225. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirose N, et al. Development of a cavity disinfectant containing antibacterial monomer MDPB. J. Dent. Res. 2016;95:1487–1493. doi: 10.1177/0022034516663465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houang ET, Gilmore OJA, Reid C, Shaw EJ. Absence of bacterial resistance to povidone iodine. J. Clin. Pathol. 1976;29:752–755. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.8.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Izutani N, Imazato S, Noiri Y, Ebisu S. Antibacterial effects of MDPB against anaerobes associated with endodontic infections. Int. Endod. J. 2010;43:637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joy Sinha D, et al. Antibacterial effect of Azadirachta indica (Neem) or Curcuma longa (turmeric) against Enterococcus faecalis compared with that of 5% sodium hypochlorite or 2% chlorhexidine in vitro. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2017;58:103–109. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.2015-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karpanen TJ, Worthington T, Hendry ER, Conway BR, Lambert PA. Antimicrobial efficacy of chlorhexidine digluconate alone and in combination with eucalyptus oil, tea tree oil and thymol against planktonic and biofilm cultures of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62:1031–1036. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koljalg S, Naaber P, Mikelsaar M. Antibiotic resistance as an indicator of bacterial chlorhexidine susceptibility. J. Hosp. Infect. 2002;51:106–113. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kreling PF, et al. Cytotoxicity and the effect of cationic peptide fragments against cariogenic bacteria under planktonic and biofilm conditions. Biofouling. 2016;32:995–1006. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2016.1218850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lacey RW. Antibacterial activity of povidone iodine towards non-sporing bacteria. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1979;46:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1979.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lavaee F, Ghapanchi J, Motamedifar M, Sharifzade Javidi M. Experimental evaluation of the effect of zinc salt on inhibition of Streptococcus mutans. J. Dent. Shiraz Iran. 2018;19:168–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee SY. Susceptibility of oral streptococci to chlorhexidine and cetylpyridinium chloride. Biocontrol Sci. 2019;24:13–21. doi: 10.4265/bio.24.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li YF, et al. Inhibited biofilm formation and improved antibacterial activity of a novel nanoemulsion against cariogenic Streptococcus mutans in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:447–462. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S72920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Machuca J, Lopez-Rojas R, Fernandez-Cuenca F, Pascual A. Comparative activity of a polyhexanide-betaine solution against biofilms produced by multidrug-resistant bacteria belonging to high-risk clones. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019;103:e92–e96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marcoux E, Lagha AB, Gauthier P, Grenier D. Antimicrobial activities of natural plant compounds against endodontic pathogens and biocompatibility with human gingival fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020;116:104734. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martins ML, et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic potential of a Brazilian red propolis. Pesqui. Bras. Em Odontopediatria E Clin. Integrada. 2019;19:4626. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Massunari L, et al. Antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility of the Psidium cattleianum extracts for endodontic purposes. Braz. Dent. J. 2017;28:372–379. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201601409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McBain AJ, Ledder RG, Gilbert P, Sreenivasan P. Selection for high-level resistance by chronic triclosan exposure is not universal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;53:772–777. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moraes TS, et al. In vitro evaluation of Copaifera oblongifolia oleoresin against bacteria causing oral infections and assessment of its cytotoxic potential. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016;17:894–904. doi: 10.2174/1389201017666160415155359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moreira MR, et al. ent-Kaurenoic acid-rich extract from Mikania glomerata: In vitro activity against bacteria responsible for dental caries. Fitoterapia. 2016;112:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moreti DLC, et al. Mikania glomerata Sprengel extract and its major compound ent-kaurenoic acid display activity against bacteria present in endodontic infections. Anaerobe. 2017;47:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morrissey I, et al. Evaluation of epidemiological cut-off values indicates that biocide resistant subpopulations are uncommon in natural isolates of clinically-relevant microorganisms. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Motamedifar M, Khosropanah H, Dabiri S. Antimicrobial activity of Peganum harmala L. on Streptococcus mutans compared to 02% chlorhexidine. J. Dent. Shiraz Iran. 2016;17:213–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Munoz-Gallego I, Infiesta L, Viedma E, Perez-Montarelo D, Chaves F. Chlorhexidine and mupirocin susceptibilities in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bacteraemia and nasal colonisation. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016;4:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakase K, et al. Propionibacterium acnes has low susceptibility to chlorhexidine digluconate. Surg. Infect. 2018;19:298–302. doi: 10.1089/sur.2017.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nazemisalman B, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial effect of Ziziphora tenuior, Dracocephalum moldavica, Ferula gummosa, and Prangos ferulacea essential oil with chlorhexidine on Enterococcus faecalis: An in vitro study. Dent. Res. J. 2018;15:111–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nicolae Dopcea G, Diguta CF, Matei F, Dopcea I, Nanu AE. Resistance and cross-resistance in Staphylococcus spp. strains following prolonged exposure to different antiseptics. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020;21:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O’Driscoll NH, Labovitiadi O, Matthews KH, Lamb AJ, Cushnie TPT. Potassium loss from chlorhexidine-treated bacterial pathogens is time- and concentration-dependent and variable between species. Curr. Microbiol. 2014;68:6–11. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pal S, Yoon EJ, Park SH, Choi EC, Song JM. Metallopharmaceuticals based on silver (I) and silver (II) polydiguanide complexes: Activity against burn wound pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:2134–2140. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roedel A, et al. Evaluation of a newly developed vacuum dried microtiter plate for rapid biocide susceptibility testing of clinical Enterococcus faecium isolates. Microorganisms. 2020;8:551. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rosa OP, Torres SA, Ferreira CM, Ferreira FB. In vitro effect of intracanal medicaments on strict anaerobes by means of the broth dilution method. Pesqui. Odontol. Bras. Braz. Oral Res. 2002;16:31–36. doi: 10.1590/s1517-74912002000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rose H, Mahenthiralingam E, Baldwin A, Dowson CG. Biocide susceptibility of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;63:502–510. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shani S, Friedman M, Steinberg D. Relation between surface activity and antibacterial activity of amine-fluorides. Int. J. Pharm. 1996;131:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sherry L, et al. Investigating the biological properties of carbohydrate derived fulvic acid (CHD-FA) as a potential novel therapy for the management of oral biofilm infections. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Skovgaard S, et al. Recently introduced qacA/B genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis do not increase chlorhexidine MIC/MBC. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013;68:2226–2233. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suwantarat N, et al. High prevalence of reduced chlorhexidine susceptibility in organisms causing central line—Associated bloodstream infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014;35:1183–1186. doi: 10.1086/677628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suzuki Y, et al. Effects of a sub-minimum inhibitory concentration of chlorhexidine gluconate on the development of in vitro multi-species biofilms. Biofouling. 2020;36:146–158. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2020.1739271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tambe SM, Sampath L, Modak SM. In vitro evaluation of the risk of developing bacterial resistance to antiseptics and antibiotics used in medical devices. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;47:589–598. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Targino AGR, et al. An innovative approach to treating dental decay in children. A new anti-caries agent. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014;25:2041–2047. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tetz G, Tetz V. In vitro antimicrobial activity of a novel compound, Mul-1867, against clinically important bacteria. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2015;4:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Touzel RE, Sutton JM, Wand ME. Establishment of a multi-species biofilm model to evaluate chlorhexidine efficacy. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;92:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Uzunbayir-Akel N, et al. Effects of disinfectants and ciprofloxacin on quorum sensing genes and biofilm of clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13:1932–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vahabi S, Hakemi-Vala M, Gholami S. In vitro antibacterial effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Lawsonia inermis, Malva sylvestris, and Boswellia serrata on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2019;8:22. doi: 10.4103/abr.abr_205_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weaver AJ, Jr, et al. Antibacterial activity of THAM trisphenylguanide against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xing M, et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of the alkaloid harmaline alone and in combination with chlorhexidine digluconate against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus grown in planktonic and biofilm cultures. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;54:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang M, Boost MV, O’Donoghue MM, Ito T, Hiramatsu K. Prevalence of antiseptic-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci colonising nurses and the general population in Hong Kong. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011;78:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhou Z, Lu Y, Wei D. Polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride shows bactericidal advantages over chlorhexidine digluconate against ESKAPE bacteria. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2015;62:268–274. doi: 10.1002/bab.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Russell AD. Bacterial resistance to disinfectants: present knowledge and future problems. J. Hosp. Infect. 1999;43:S57–S68. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Platt JH, Bucknall RA. MIC tests are not suitable for assessing antiseptic handwashes. J. Hosp. Infect. 1988;11:396–397. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Russell AD. Do biocides select for antibiotic resistance? J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010;52:227–233. doi: 10.1211/0022357001773742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.EUCAST. On recent changes in clinical microbiology susceptibility reports—new interpretation of susceptibility categories S, I and R. EUCAST.orghttps://www.eucast.org/newsiandr/ (2021).

- 118.Essentials of neuroanesthesia. (Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/khnb2/). The statistical syntax are available from the senior author (RGW) upon request.