Abstract

Following a request from the European Commission, the EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA) was asked to deliver a scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for selenium. Systematic reviews of the literature were conducted to identify evidence regarding excess selenium intake and clinical effects and potential biomarkers of effect, risk of chronic diseases and impaired neuropsychological development in humans. Alopecia, as an early observable feature and a well‐established adverse effect of excess selenium exposure, is selected as the critical endpoint on which to base a UL for selenium. A lowest‐observed‐adverse‐effect‐level (LOAEL) of 330 μg/day is identified from a large randomised controlled trial in humans (the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT)), to which an uncertainty factor of 1.3 is applied. A UL of 255 μg/day is established for adult men and women (including pregnant and lactating women). ULs for children are derived from the UL for adults using allometric scaling (body weight0.75). Based on available intake data, adult consumers are unlikely to exceed the UL, except for regular users of food supplements containing high daily doses of selenium or regular consumers of Brazil nuts. No risk has been reported with the current levels of selenium intake in European countries from food (excluding food supplements) in toddlers and children, and selenium intake arising from the natural content of foods does not raise reasons for concern. Selenium‐containing supplements in toddlers and children should be used with caution, based on individual needs.

Keywords: tolerable upper intake level, UL, selenium, dietary reference value

1. Introduction

1.1. Background as provided by the European Commission

On 19 October 2000, the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) expressed an opinion on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for selenium. The SCF derived a UL of 300 μg Se/day for adults that covered selenium intake from all sources of food, including supplements. The SCF extrapolated the UL from adults to children on a body weight basis as follows: 1–3 years of age – 60 μg Se/day; 4–6 years of age – 90 μg Se/day; 7–10 years of age – 130 μg Se/day; 11–14 years of age – 200 μg Se/day; 15–17 years of age – 250 μg Se/day.

On 18 December 2019, the Authority adopted an opinion on the “Safety of selenium‐enriched biomass of Yarrowia lipolytica as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283”. In its opinion, the Authority noted that newly emerging data, including the results of large population‐based randomised controlled trials made available in recent years, warranted a reassessment of the UL for selenium as established in 2000.

Consequently, the European Commission would like to ask the Authority to re‐evaluate the safety in use of selenium, and to provide revised tolerable upper intake levels that are unlikely to pose a risk of adverse effects from intake of this nutrient, for all population groups.

1.2. Terms of Reference as provided by the European Commission

In accordance with Article 29(1)(a) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, the European Commission asks the European Food Safety Authority to:

-

–

re‐evaluate the safety in use of selenium;

-

–

if necessary, provide revised tolerable upper intake levels for selenium for all relevant categories of the population that are unlikely to pose a risk of adverse health effects.

1.3. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

The UL is defined as ‘the maximum level of total chronic daily intake of a nutrient (from all sources) which is not expected to pose a risk of adverse health effects to humans’ (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022).

‘Tolerable intake’ in this context connotes what is physiologically tolerable and can be established based on an assessment of risk, i.e. the probability of an adverse effect occurring at a specified level of exposure. The UL is not a recommended level of intake. As the intake increases above the UL, the risk of adverse effects increases.

ULs should be protective for all members of the general population, including the most sensitive individuals, throughout their lifetime. The derivation of ULs accounts for the expected variability in sensitivity among individuals. In principle, individuals under medical care are not excluded from the application of the UL unless: (a) there is an expected interaction between the medical condition and the occurrence of possible adverse effects of a nutrient, or (b) they are under medical treatment with the nutrient under assessment.

On the other hand, the UL may exclude sub‐populations with extreme and distinct vulnerabilities to adverse effects of the nutrient due to specific genetic predisposition or other factors. The exclusion of such sub‐populations must be considered on a nutrient‐by‐nutrient basis and is an area of scientific and expert judgement and of risk management (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022).

1.4. Context of the assessment

The Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) in 2000 set a UL of 300 μg/day in adults, including pregnant and lactating women, based on evidence from observational studies on long term selenium exposure carried out in selenium‐rich areas in China (Yang et al., 1989a; Yang and Zhou, 1994) and in the US (Longnecker et al., 1991), where selenium poisonings are endemic due to high selenium concentrations in soil (SCF, 2000a). For children, the SCF extrapolated the UL from adults on a body weight basis, using reference weights (SCF, 1993). No UL was established for infants. ULs set by SCF (2000a) are summarised in Table 1. These values cover selenium intakes from all food sources, including food supplements.

Table 1.

Overview of existing tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for selenium, in μg/day

| Population group | SCF (2000a) | IOM (2000) | EVM (2003) (a) | WHO/FAO (2004) | NHMRC (2006) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | |||||

| 0–6 mo | nd | 45 | nd | nd | 45 |

| 7–12 mo | nd | 60 (b) | nd | nd | 60 (b) |

| Children and adolescents | |||||

| 1–3 y | 60 (c) | 90 (b) | nd | nd | 90 (b) |

| 4–6 y | 90 (c) | nd | nd | ||

| 4–8 y | 150 (b) | nd | nd | 150 (b) | |

| 7–10 y | 130 (c) | nd | nd | ||

| 9–13 y | 280 (b) | nd | nd | 280 (b) | |

| 11–14 y | 200 (c) | nd | nd | ||

| 14–18 y | 400 (b) | nd | nd | 400 (b) | |

| 15–17 y | 250 (c) | nd | nd | ||

| Adults | |||||

| ≥ 18 y | 300 (d) | 450 | 400 | ||

| ≥ 19 y | 400 (d) | 400 (d) | |||

mo: months; nd: not defined; EVM: UK Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals (UK); IOM: Institute of Medicine (US); NHMRC: National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and New Zealand; SCF: Scientific Committee on Food; WHO/FAO: World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; y: years.

Safe upper level (SUL).

Extrapolated from the UL for infants aged 0–6 months (7 μg/kg body weight/day) on a body weight basis.

Extrapolated from the UL for adults on a body weight basis.

Including pregnant and lactating women.

In 2014, the NDA Panel published an opinion on Dietary Reference Values (DRVs) for selenium (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). As per the terms of reference for this task, a review of the UL for selenium was out of the scope of the assessment. The NDA Panel focused on providing advice on the requirement for the micronutrient. The levelling off of plasma selenoprotein P concentration with increasing selenium intakes was considered indicative of an adequate supply of selenium to all tissues and to reflect saturation of the functional selenium body pool, ensuring that selenium requirement is met. This criterion was used for establishing DRVs for selenium in adults. Evidence from human studies on the relationship between selenium intake and plasma selenoprotein P concentration was reviewed. Given the uncertainties in available data on this relationship, they were considered insufficient to derive an Average Requirement (AR). Instead, the Panel established an Adequate Intake (AI) for adults of 70 μg/day. No specific indicators of selenium requirements were available for infants, children or adolescents. For infants aged 7–11 months, an AI of 15 μg/day was derived by extrapolating upwards from the estimated selenium intake from breast milk of younger exclusively breast‐fed infants (i.e. 12 μg/day), taking into account differences in reference body weights. For children and adolescents, the AIs for selenium were extrapolated from the AI for adults by isometric scaling (i.e. proportionately to body weight) and application of a growth factor. AIs range from 15 μg/day for children aged one to 3 years to 70 μg/day for adolescents aged 15–17 years. Considering that adaptive changes in the metabolism of selenium occur during pregnancy, the AI set for adult women applies to pregnancy. For lactating women, an additional selenium intake of 15 μg/day was estimated to cover the amount of selenium secreted in breast milk, and an AI of 85 μg/day was set.

EFSA evaluated the safety and bioavailability of various forms of selenium as a source of selenium for use in food supplements or addition to foods. The safety and bioavailability of selenium‐enriched yeast (Se‐yeast) as a source of selenium were established under the proposed conditions of use, for addition to foods for particular nutritional uses and foods, including food supplements (EFSA AFC Panel, 2008). The safety and bioavailability of l‐selenomethionine (SeMet) (EFSA ANS Panel, 2009b) and selenious acid (EFSA ANS Panel, 2009d) were established for use in food supplements, under the proposed conditions of use. In contrast, data provided in the application dossiers were inadequate to establish the safety and bioavailability of selenium‐humic acid/fulvic acid chelate (EFSA ANS Panel, 2009a) and Se‐methyl‐l‐selenocysteine (EFSA ANS Panel, 2009c), under the proposed conditions of use.

EFSA's Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP Panel) has assessed the safety of several selenium compounds in the context of their use as additives in animal feed and have considered them to be safe for consumers provided that the total maximum authorised content of selenium in complete feed is respected (EFSA FEEDAP Panel, 2013a,b, 2015, 2016a,b,c, 2018a,b, 2019a,b, 2021).

1.5. Previous assessments by other bodies

As for the SCF assessment, clinical selenosis (see Section 3.5.2) was the critical effect used by other authoritative bodies in charge of establishing ULs for adults (IOM, 2000; EVM, 2003; WHO/FAO, 2004; NHMRC, 2006; FSCJ, 2012) considering the findings reported by Yang et al. (1989a), Yang and Zhou (1994) and Longnecker et al. (1991). Regarding lactating mothers, most risk assessments refer to the study by Brätter and Negretti de Brätter (1996). The studies by Shearer and Hadjimarkos (1975) and Brätter et al. (1991), which collected data on selenium concentration in human milk in women in the US and Canada, and in Germany respectively, were used as reference to establish the ULs for infants.

An overview of ULs for selenium established by other risk assessment bodies is provided in Table 1 below (see Appendix B of the protocol (Annex A) for further details).

2. Data and methodologies

For this scientific assessment, a protocol (Annex A) has been developed in line with EFSA's existing methodology (EFSA, 2020).

2.1. Problem formulation

In accordance with the draft NDA Panel guidance on establishing and applying ULs for vitamins and essential minerals (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022), the assessment questions underlying the UL evaluation are formulated as follows:

What is the maximum level of total chronic daily intake of selenium (from all sources) which is not expected to pose a risk of adverse health effects to humans? (Hazard identification and hazard characterisation)

What is the daily intake of selenium from all dietary sources in EU populations? (Intake assessment)

What is the risk of adverse effects related to the intake of selenium in EU populations, including attendant uncertainties? (Risk characterisation)

The hazard identification and hazard characterisation relate to the identification of adverse health effects of a given nutrient and the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the adverse health effects associated with the nutrient, including dose–response assessment and derivation of an UL, if possible.

Adverse (health) effects are defined as ‘a change in the morphology, physiology, growth, development, reproduction or life span of an organism, system or (sub)population that results in an impairment of functional capacity to compensate for additional stress or an increase in susceptibility to other influences (FAO/WHO, 2009; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017a). The observable effects of high nutrient intake within the causal pathway of an adverse health effect can range from biochemical changes without functional significance (e.g. certain changes in enzyme activity) to irreversible clinical outcomes. Notably, some changes that occur before clinical manifestations could be used as surrogate or predictive markers of subsequent adverse health effects, i.e. biomarkers of effect’ (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022).

Available risk assessments on dietary selenium intakes from authoritative bodies (IOM, 2000; EVM, 2003; WHO/FAO, 2004; NHMRC, 2006; FSCJ, 2012) and expert reviews (Fairweather‐Tait et al., 2011; Rayman, 2012; Vinceti et al., 2014; Jablonska and Vinceti, 2015; Vinceti et al., 2016b; Vinceti et al., 2017b; Brigelius‐Flohe and Arner, 2018; Dinh et al., 2018; Vinceti et al., 2018b; Rayman, 2020; Naderi et al., 2021) were used to identify adverse health effects that have been associated with excess selenium intakes in humans. As a result, the following effects were prioritised for the risk assessment: selenosis (including biomarkers of effect of excess selenium intake), hypertension, Alzheimer's dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), impaired neuropsychological development in children, thyroid diseases, prostate cancer, skin cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and overall mortality. The rationale for the prioritisation is detailed in the protocol (Annex A).

As a result of the problem formulation, the overarching risk assessment questions were further specified into assessment sub‐questions (sQs) and the methods to address each sQ was selected, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Assessment sub‐questions

| Sub‐question | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| sQ1 |

a. What are the clinical effects associated with selenosis (a) in humans? b. What are biomarkers of effect (b) of excess selenium intake in humans? What is their biological relevance? |

Systematic review |

| sQ2 |

a. Is there a causal positive relationship between selenium intake and risk of diseases in humans, with a focus on hypertension, Alzheimer's dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), thyroid diseases, prostate cancer, skin cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and overall mortality? b. Is there a causal positive relationship between selenium intake and risk of impaired neuropsychological development in children? c. Is there a positive relationship between selenium intake and excess overall mortality risk in humans? |

Systematic review |

| sQ3 | What is the quantitative relationship between selenium intake and plasma selenium concentrations in humans? | Narrative review and dose–response modelling (if applicable) |

| sQ4 | What is the dose–response relationship between selenium intake and clinical effects of selenosis (a) and/or biomarkers of effect of excess selenium intake in humans? | Systematic review and dose–response modelling (if applicable) |

| sQ5 | What is the dose–response relationship between selenium intake and risk of disease in humans? | Systematic review and dose–response modelling (if applicable) |

| sQ6 | What is the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of selenium and specific selenium species from different sources in humans? | Narrative review |

| sQ7 | What are the potential mode(s) of action for the relationships found between selenium intake and adverse health effects? | Narrative review |

| sQ8 |

a. What are the levels of selenium in foods, beverages and food supplements in the EU? b. What is the distribution of daily selenium intake from all dietary sources in EU populations and subgroups thereof? |

Collection of data based on existing EFSA intake estimates and complementary searches in relevant databases and inquiries to competent Authorities of European Countries |

sQ: subquestion.

In the clinical setting, the term selenosis refers to a specific clinical condition resulting from excess selenium exposure, as diagnosed based on accepted signs and symptoms (integumental features in particular). This condition is observed especially in populations living in seleniferous areas. This term can also be more generally used to refer to selenium toxicity and associated features. In the context of the formulation of sQ1 and sQ4, the term selenosis is to be understood in a wide sense.

Biomarker of effect: ‘a measurable biochemical, physiological, behavioural or other alteration within an organism that, depending upon the magnitude, can be recognised as associated with an established or possible health impairment or disease’ (WHO/IPCS, 1993; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017a). Its biological relevance depends on its relation to the mode of action and the linkage with the adverse effect or the relevant adverse outcome pathway (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017a).

2.2. Hazard identification and characterisation (sQ1 to sQ7)

2.2.1. Data

A brief description of the processes applied for evidence retrieval, study selection and data extraction is provided below (see the protocol (Annex A) for further details).

2.2.1.1. Priority adverse health effects (sQ1 and sQ2)

To address sQ1 and sQ2, relevant human studies on the selected adverse health effects were identified through systematic searches of the literature in PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane library for articles published in English. The search strategy was created by EFSA's information specialist and is further detailed in the protocol (Annex A). Grey literature was not searched. No limit was applied regarding the inception date. The searches were performed on the 7 May 2021 regarding sQ1 and 3 May 2021 regarding sQ2. An update of the literature search focusing on T2DM was performed on the 7 February 2022.

Retrieved articles were screened in duplicate in Distiller SR® at title and abstract and full‐text levels for inclusion/exclusion according to the criteria defined in the protocol. Conflicts were solved by a third reviewer, if necessary. Relevant systematic reviews were hand‐searched for additional pertinent studies. Reviews, expert opinions, editorials, letters to the editors, abstracts, posters and theses were excluded.

Eligible designs: For selenosis and related potential biomarkers of effects (sQ1), all experimental and observational study designs in humans (including case reports) were considered relevant. For other health effects (sQ2), eligible study designs were limited to prospective designs, i.e. human controlled trials (HCTs; randomised or non‐randomised), prospective cohort studies (PCs) and nested case–control studies (NCCs).

Eligible study populations: Studies were eligible if they involved individuals of any age, either healthy individuals or diseased individuals if the disease was considered not to be related to the exposure–outcome relationship. Decision on the inclusion/exclusion of studies conducted in diseased individuals were taken by the experts of the EFSA working group on ULs and the rationale for the decisions is available in Annex E.

Eligible exposure measurements: studies were eligible if they measured selenium intake by dietary assessment methods or used accepted biomarkers of selenium intake, i.e. whole blood/plasma/serum/red blood cell (RBC) selenium, urinary selenium, toenail/hair selenium, whole blood/plasma/serum selenoprotein P concentrations and whole blood/plasma/serum/RBC glutathione peroxidase activity (see Section 3.3).

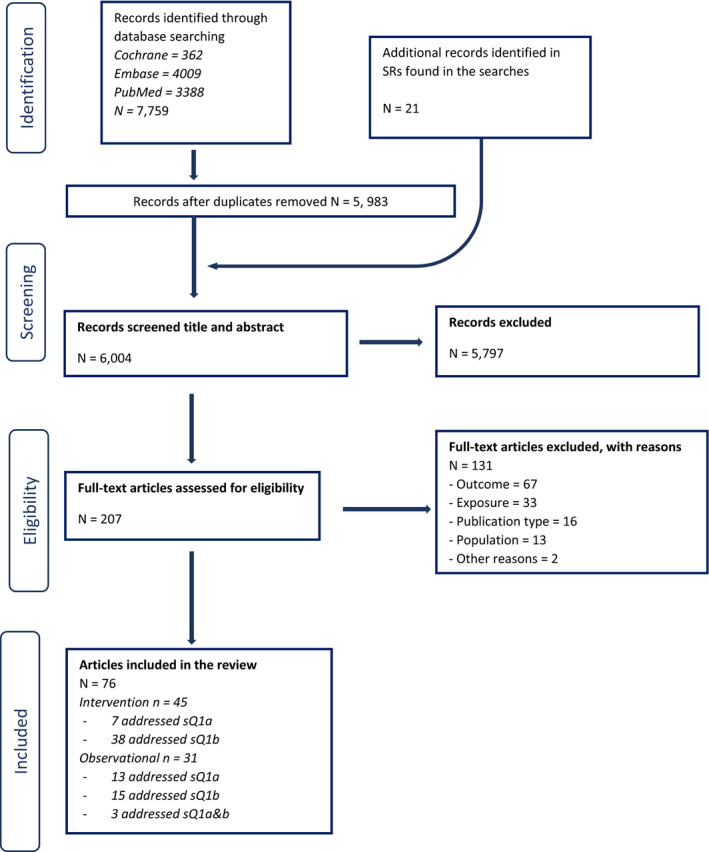

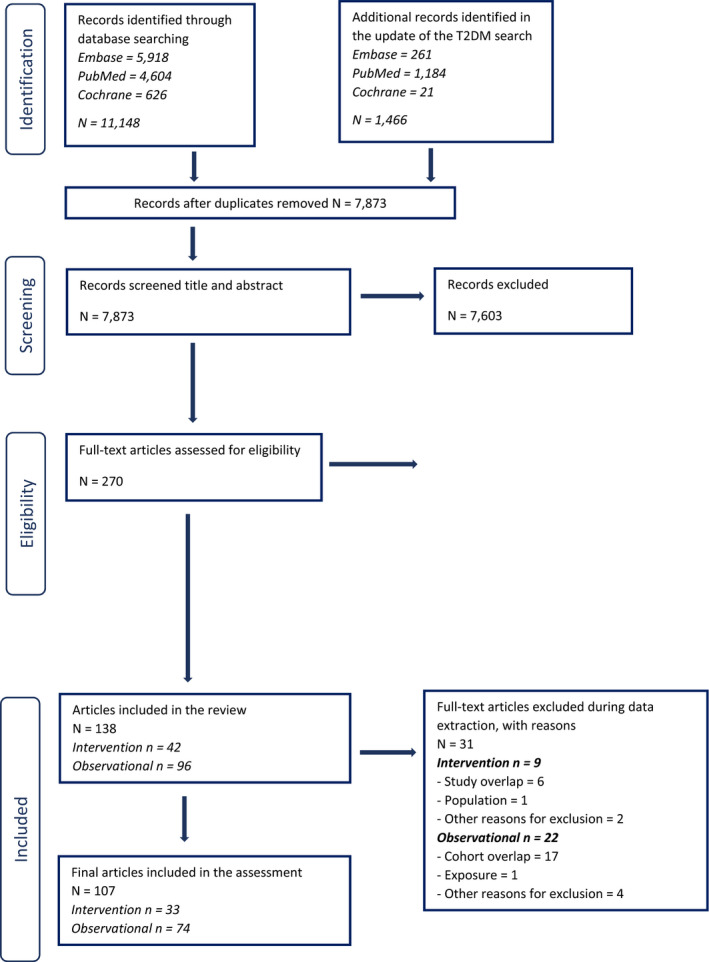

In relation to sQ1, 6,004 unique references were identified after removing duplicates (flow chart in Appendix B). The title and abstract screening left 207 relevant articles that underwent a full‐text review. Of those, 130 were excluded. A total of 77 publications reporting on 45 HCTs and 32 observational studies were included.

In relation to sQ2, 7,873 unique references were identified after removing duplicates (flow chart in Appendix B). The title and abstract screening left 363 relevant articles that underwent a full‐text review. Of those, 224 were excluded and additional 31 were excluded during the data extraction step (see below). A total of 108 publications reporting on 33 HCTs and 75 observational studies were included.

For the purpose of data plotting and analysis, data were extracted into Microsoft Excel® by one EFSA staff member and double checked by another. Evidence tables were prepared in Microsoft Word® and are provided in Appendix D.

2.2.1.2. Dose–response between selenium intake and plasma/serum concentration (sQ3)

Many studies investigating the relationship between selenium exposure and health effects use serum/plasma selenium as a biomarker of dietary selenium intake. A predictive equation for estimating selenium intake from serum/plasma selenium concentrations was needed to integrate these data in the risk assessment. In particular, the equation was instrumental for performing the dose–response meta‐analysis on selenium exposure and incidence of T2DM (see Section 2.2.2.2).

Studies used to characterise the quantitative relationship between selenium intake and plasma or serum selenium concentrations were identified through the searches described in Section 2.2.2.1 (sQ1 and sQ2) (see Annex A). The reviews by Haldimann et al. (1996), Jenny‐Burri et al. (2010) and Noisel et al. (2014) were used to retrieve additional relevant studies. Additionally, a separate search in PubMed was tailored for similar reviews published after 2011, the date up to when the literature had been searched by Noisel et al. (2014). No additional reviews were retrieved. However, the Panel notes that publications reviewing equations by which selenium intake can be assessed from plasma or serum concentrations may not be classified consistently as reviews in literature databases. In total, 43 studies were identified through the searches performed to address sQ1 and sQ2 and an additional 11 were found by searching the reference list of the reviews mentioned above, yielding a total of 54 studies.

HCTs, PCs, NCCs, case–control studies (CCs) and cross‐sectional studies (CSs) were included when they reported cross‐sectionally on the dietary selenium intake from all sources (i.e. food plus food supplements), using 24‐h recalls and dietary records, and on plasma or serum selenium concentrations. There was no restriction regarding study location (to explore ethnicity as an influencing factor for plasma selenium as a biomarker of selenium intake). Owing to the fact that inorganic selenium forms have a different effect on plasma selenium concentrations than organic forms of selenium (see also Section 3.2), inorganic forms are to be considered separately from organic forms. As, however, only two studies reported on inorganic forms (i.e. selenate Levander et al., 1983; selenite Martin et al., 1989), the study arms in which inorganic selenium was consumed in these studies were excluded from further analyses and only studies that administered organic selenium or in which selenium originated from mixed diets were included (Annex B).

2.2.1.3. Other background information (sQ6 and SQ7)

For questions addressed through narrative reviews (sQ6 and sQ7), searches were conducted in PubMed to retrieve articles reporting on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of selenium, on the potential mechanisms by which selenium may exert an adverse health effect, and on the potential confounders or effect modifiers to be considered in the risk of bias (RoB) assessment of individual studies.

In addition, an expert review was contracted out through a procurement procedure with the aim to identify the most recent evidence on ADME, potential pathways to adverse health effects and potential biomarkers of effect. 1

2.2.2. Methodologies

The methodology for this assessment follows the approach for deriving ULs for nutrients laid down by the SCF (2000b), the principles established by the EFSA NDA Panel (2022), EFSA's guidance on the application of the systematic review methodology in food and feed safety assessments (EFSA, 2010), its principles and processes for dealing with data and evidence in scientific assessments (EFSA, 2015), the guidance on statistical significance and biological relevance (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2011), the guidance on the assessment of the biological relevance of data in scientific assessments (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017a), the guidance on the use of the weight of evidence approach in scientific assessments (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017c) and the draft guidance on appraising and integrating evidence from epidemiological studies for use in EFSA's scientific assessments (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2020).

2.2.2.1. Evidence appraisal (sQ2)

A RoB appraisal, i.e. evaluation of the internal validity of studies, was applied to eligible studies which addressed sQ2.

The appraisal was performed using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) RoB tool developed by the US National Toxicology Program (NTP) (OHAT‐NTP, 2015). The RoB criteria and rating instructions provided therein were tailored to the specific research questions, for the questions addressing: (1) consideration of potential confounders, (2) confidence in the exposure characterisation, and (3) confidence in the outcome assessment (Appendix C).

The appraisal was performed in duplicate by the experts of the EFSA Working Group (WG) on ULs and EFSA staff in Distiller SR®. Discrepancies in the assessment in relation to the RoB judgement of each domain were discussed among the assessors. In case of disagreement, the WG was consulted.

The OHAT RoB tool proposes five response options for each RoB question: definitely low RoB (++), probably low RoB (+), not reported (NR), probably high RoB (−), definitely high RoB (−−). For the appraisal of intervention studies, the scale was aggregated to three options (high RoB, NR, low RoB) as it was considered sufficiently discriminatory for this design in the context of the present assessment.

Studies were categorised according to their overall RoB based on a three‐tier system (i.e. at low (tier 1), moderate (tier 2) or high (tier 3) RoB), according to the strategy proposed by OHAT (OHAT‐NTP, 2019) (Appendix C).

2.2.2.2. Evidence synthesis (sQ2, sQ3 and sQ5)

The methods applied for the evidence synthesis to address sQ2, sQ3 and sQ5 are outlined below. Detailed information is provided in Annex B.

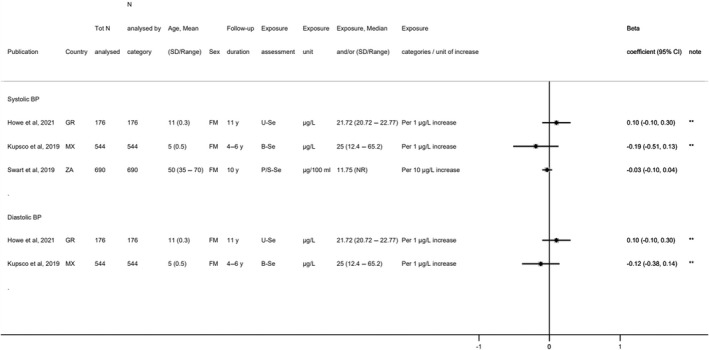

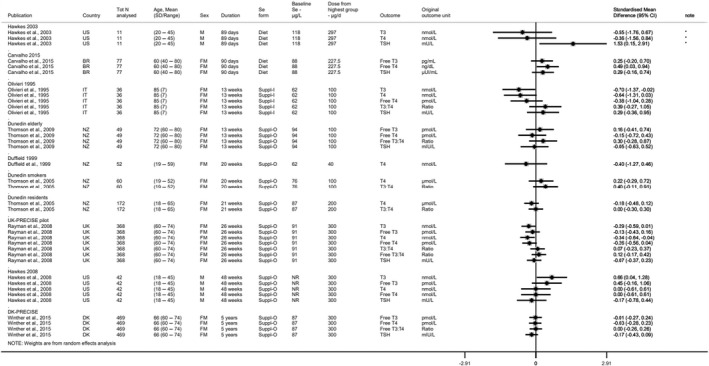

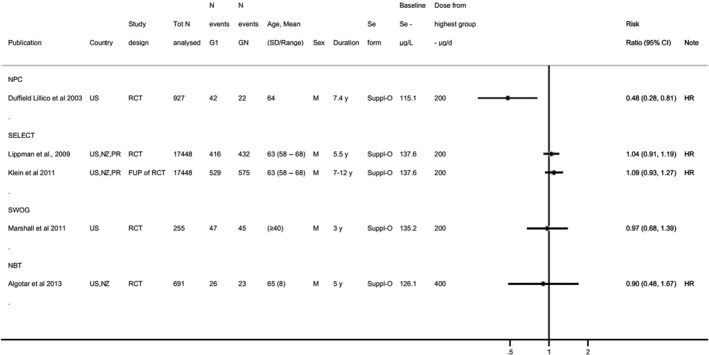

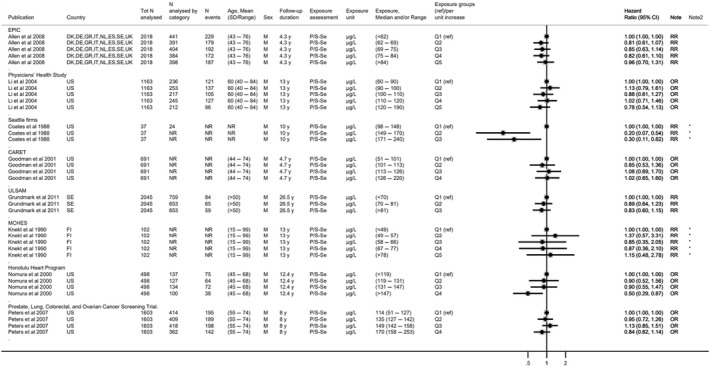

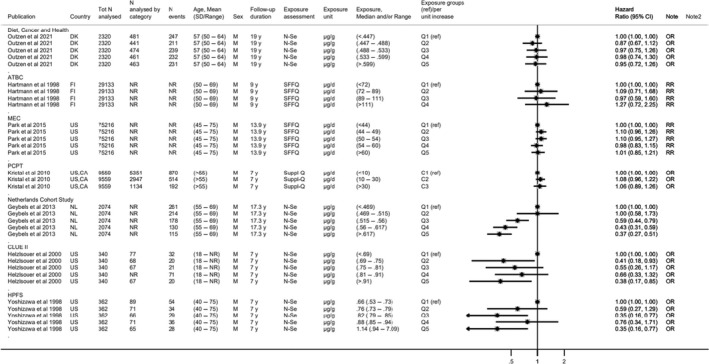

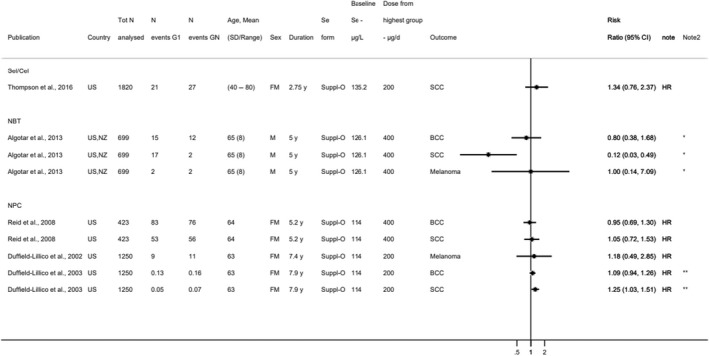

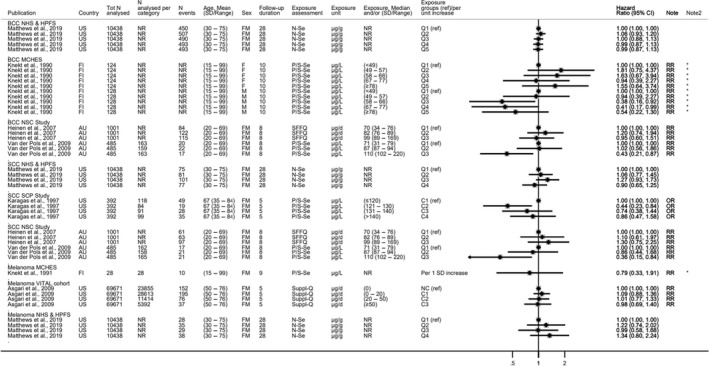

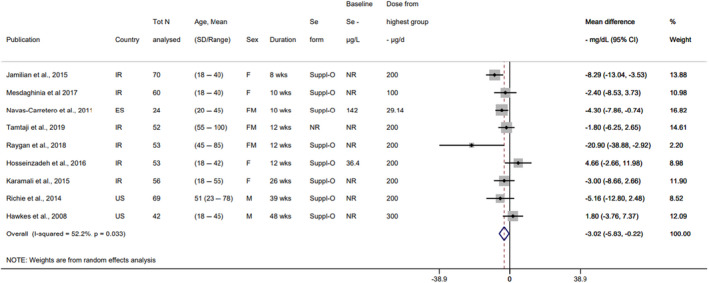

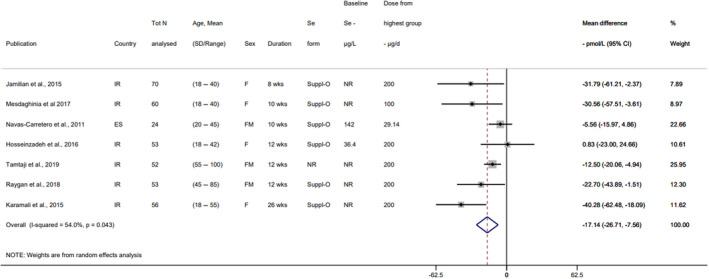

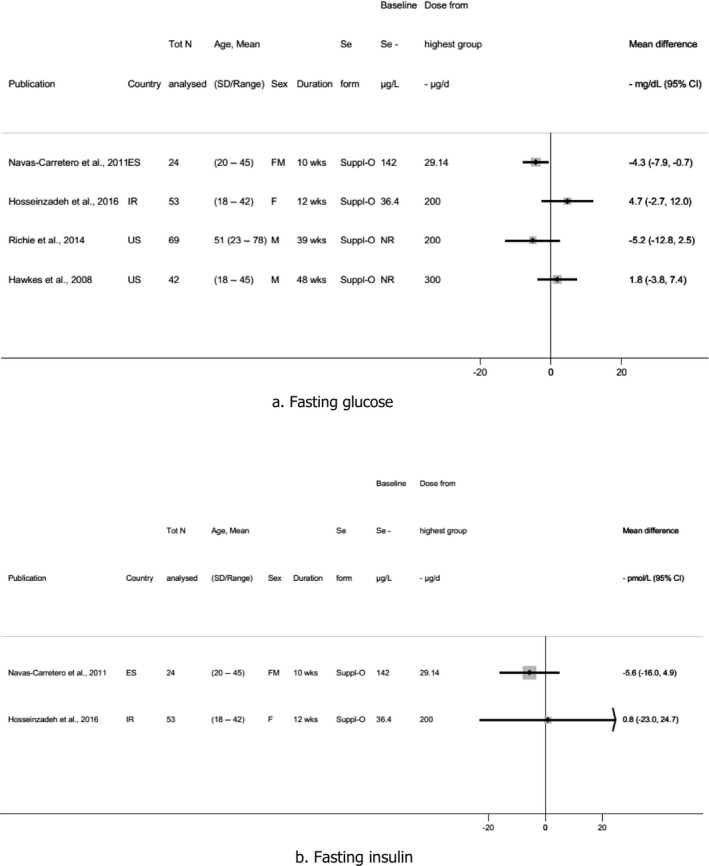

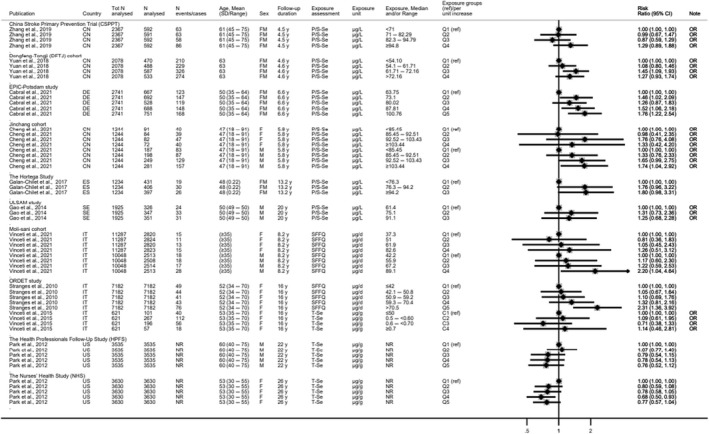

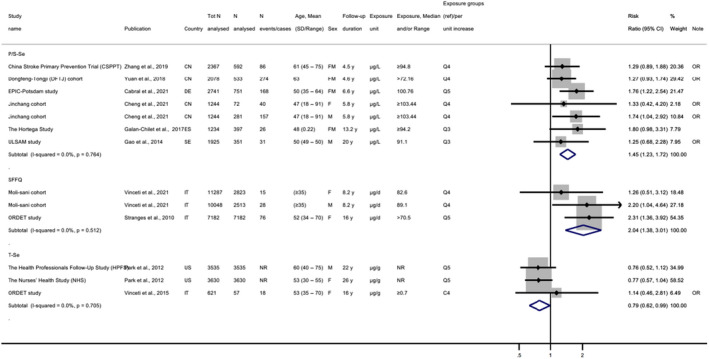

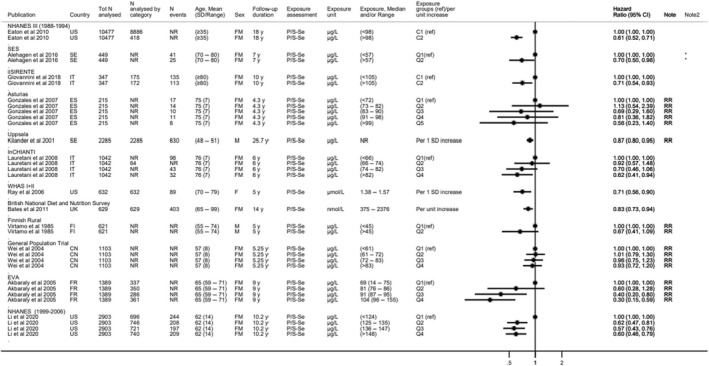

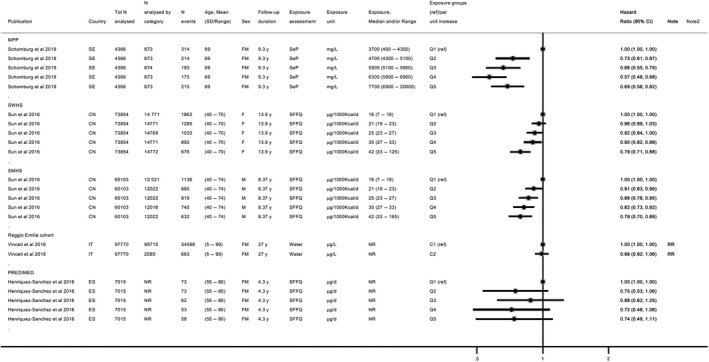

Descriptive forest plots of studies investigating selenium exposure and health effects.

Results from eligible studies were plotted using descriptive forest plots, when three or more studies reported on the same outcome. For intervention studies with several selenium doses, the mean difference between the highest dose group and control group was selected for the plot, unless specified otherwise. For observational studies reporting both continuous and categorical analyses, the latter was selected for the plot.

Dose–response relationship between selenium intake and plasma/serum concentration

A dose–response meta‐analysis was conducted by EFSA to characterise the relationship between mean selenium intake and mean plasma/serum selenium concentration. Parametric dose–response models were estimated based on summarised data. Both linear and non‐linear (piecewise linear splines) dose–response relationships were investigated. Random‐effects models were fitted on mean values from both observational and experimental designs via restricted maximum likelihood. The between‐study heterogeneity was investigated with Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistic. Different knots for the piecewise linear function were explored and potential modifying factors were characterised; sensitivity analyses were run to address the uncertainty in the choice of spline knots, the influence of individual studies, aspects of study design and the reliability of studies' features.

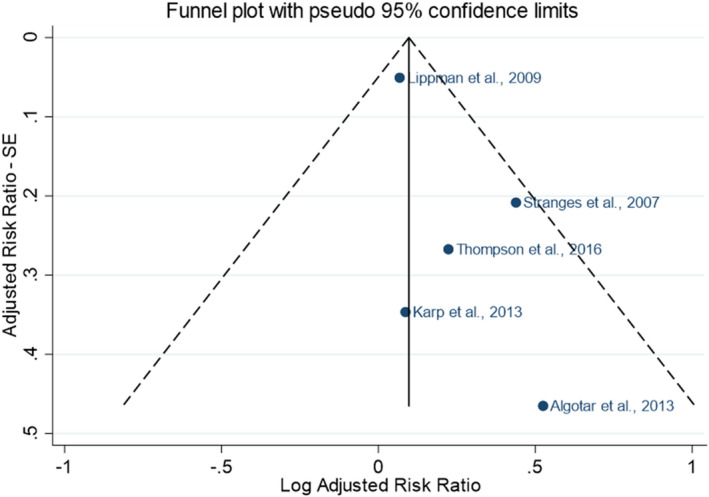

Dose–response relationship between selenium exposure and incidence of T2DM

A dose–response meta‐analysis was conducted by EFSA to characterise the relationship between plasma/serum selenium concentrations and incidence of T2DM based on observational studies. The analysis included studies using plasma/serum selenium concentrations as exposure variable as well as studies which estimated selenium intake based on dietary assessment methods. In the latter case, the piecewise regression equation described above was used to convert mean selenium intakes into estimates of plasma/serum selenium concentrations for inclusion in the dose–response analysis.

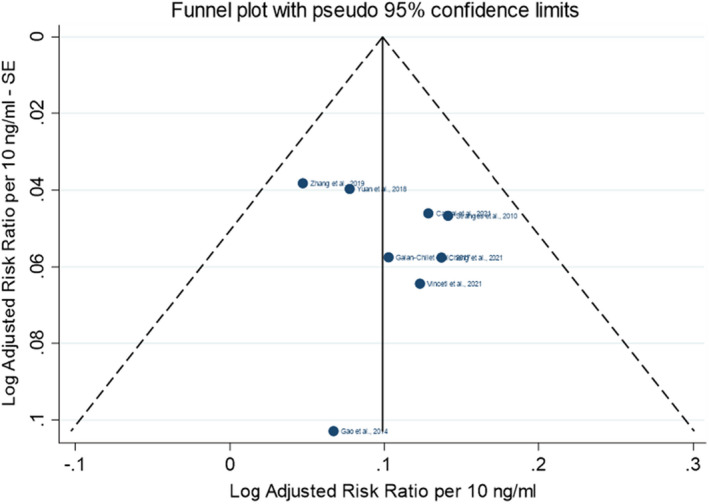

Parametric dose–response models were estimated based on summarised data. Both linear and non‐linear (restricted cubic splines) dose–response relationships were investigated. Random‐effects models were fitted on risk ratios (RR) from most adjusted multivariable models via restricted maximum likelihood using a one‐stage approach (Crippa et al., 2019) and a two‐stage approach (Orsini et al., 2012) to estimate pooled effects of individual studies across exposure categories. The reference dose chosen corresponded to the lowest mean plasma concentration observed or estimated in the sample. The between‐study heterogeneity was investigated with Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistic; sensitivity analyses were run to address the uncertainty in the choice of spline knots, in the type of exposure assessment and in the influence of individual studies. Publication bias was assessed using Egger's test and funnel plot on study‐specific RRs.

2.2.2.3. Evidence integration (sQ1 and sQ2)

Hazard identification

Regarding sQ1, a causal relationship between ‘high’ selenium intake and clinical selenosis is well‐established and the assessment focussed on the characterisation of the dose–response. As proposed in the guidance for establishing and applying ULs for vitamins and essential minerals (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022), some changes that occur before clinical manifestations of excess selenium intake could be used as surrogate or predictive markers of subsequent adverse health effects, i.e. biomarkers of effect. Thus, data that could inform the identification of potential biomarkers of effect were also gathered and explored.

Regarding sQ2, the hazard identification step consisted of assessing the evidence for a causal positive relationship between selenium intake and the health effects identified. For each health effect, HCTs and prospective observational studies (PCs/NCCs) are organised in separate lines of evidence (LoE), which are classified in hierarchical order:

Standalone main LoE: Studies on disease endpoints (e.g. incidence of hypertension, incidence of T2DM). These studies could, on their own, answer the sQ directly.

Standalone surrogate LoE: Studies on endpoints which are surrogate measures of the disease risk (e.g. blood pressure for hypertension, fasting blood glucose for T2DM). These studies also could, on their own, answer the sQ, on the assumption that a sustained increase in the surrogate measure over time (e.g. blood pressure) would eventually lead to an increased risk of disease (e.g. hypertension). However, the Panel is aware of the uncertainty inherent in this assumption, and this was considered in the uncertainty analysis (UA) for each sQ (see for example Section 3.5.10).

Complementary LoE: Studies on endpoints which are relevant to the disease but less directly than those included in standalone LoE (e.g. risk factors, upstream indicators, other biologically related endpoints). These studies, on their own, cannot answer the sQ but can be used as supporting evidence to the standalone LoEs.

Conclusions on each health effect are reached by study design (HCTs separately from PCs/NCCs), through considering the uncertainties in the body of evidence (BoE) and in the methods.

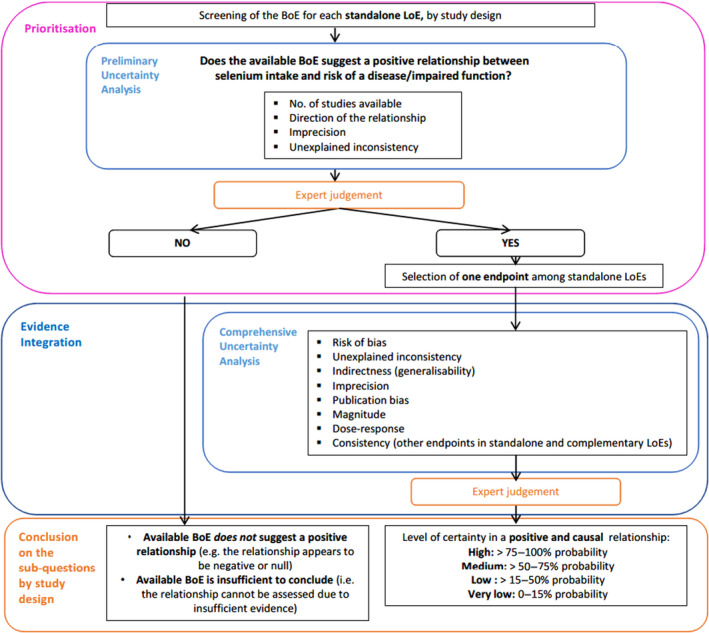

A stepwise approach is applied as illustrated in Figure 1 and described below:

Figure 1.

Stepwise approach for evidence integration and uncertainty analysis applied to sQ2, by study design

- BoE: body of evidence; LoE: line of evidence.

Prioritisation

A prioritisation step is applied to identify health effects for which the available BoE suggests a positive relationship between dietary intake of selenium and risk of disease/impaired function based on a preliminary UA and expert judgement. The Panel considers that health effects for which the available BoE (i) does not suggest a positive relationship (i.e. the relationship appears to be negative or null) or (ii) is insufficient to conclude on a relationship, cannot be used to inform the setting of a UL for selenium. Data gaps and research needs are identified, where appropriate.

When the available BoE indicates a positive association between selenium intake and the risk of a disease/impaired function, a comprehensive UA is performed to inform the formulation of the hazard identification conclusions, i.e. judgement on the level of certainty for a causal relationship. For health effects with more than one standalone LoE, the comprehensive uncertainty analysis is undertaken for the endpoint with the highest level of evidence for a positive relationship with the exposure.

Evidence integration and conclusions on the prioritised SQs, by study design

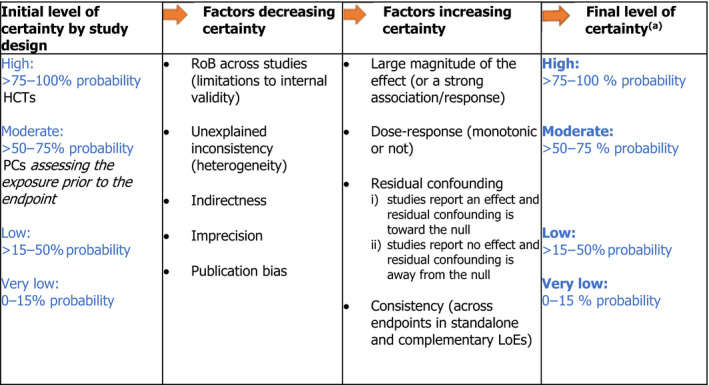

The OHAT‐NTP framework for the formulation of hazard identification conclusions is used and adapted (OHAT‐NTP, 2019). According to the OHAT‐NTP approach, available studies on a particular outcome are initially grouped by study design (i.e. trials vs prospective cohort studies) and the BoE on a particular sQ is given an initial level of certainty based on study design. In the OHAT's framework, the ‘initial confidence rating’ is expressed through four qualitative descriptors, i.e. ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’, ‘very low’. It is assigned by considering four features of the design i.e. exposure is experimentally controlled, exposure occurs prior to the endpoint, endpoint is assessed at individual level and an appropriate comparison group is included in the study. As a result, OHAT assigns a ‘high’ confidence rating (likely to comply with all four the above‐mentioned criteria) to HCTs, while PC studies (where the exposure is unlikely to be controlled) start with a ‘low’ to ‘moderate’ confidence rating, 2 depending on whether the exposure precedes the outcome or not (OHAT‐NTP, 2019). The Panel agrees with the rationale behind this initial rating but notes that qualitative descriptors bear some ambiguity. The EFSA Scientific Committee recommends the use of probability as the preferred measure for expressing uncertainty (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018). Therefore, OHAT's ‘initial confidence ratings’ have been translated into ‘initial levels of certainty’ expressed as approximate probabilities. Similarly, the final level of certainty for a positive and causal relationship between the exposure and risk of disease is expressed in terms of probabilities, rather than using qualitative descriptors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Approach applied to assign the final level of certainty in a causal relationship

-

Adapted from OHAT‐NTP (2019).LoE: line of evidence; PC: prospective cohort study; HCT: human controlled trial; RoB: risk of bias.(a): As an example, a ‘high level of certainty’ means that, based on the available evidence, experts are 75%–100% certain that selenium is positively and causally associated with the disease of interest.

A schematic representation of the approach for assessing the final level of certainty in the hazard identification conclusions by study design is provided in Figure 2. This initial rating is downgraded on the basis of factors that decrease certainty in the results (RoB, unexplained inconsistency, indirectness or lack of applicability, imprecision, and publication bias) and upgraded for factors that increase certainty in the results (large magnitude of effect, dose–response, consistency across study designs/populations/animal models or species, and consideration of residual confounding or other factors that increase the certainty in the causal nature of the relationship).

Reaching overall conclusions on the prioritised SQs

Adapted from the OHAT‐NTP approach, the overall conclusion regarding the relationship is formulated as follows:

hazard identification conclusions are primarily based on the BoE providing the highest level of certainty on the relationship;

consistent results across study designs could result in higher level of certainty on the causality of a positive relationship;

mechanistic or mode‐of‐action data are considered as other relevant supporting types of evidence; they could provide strong support or opposition for biological plausibility and could thus result in higher or lower certainty on the causality of the positive relationship.

It is noted that the formulation of hazard identification conclusions necessarily requires expert judgement. The value of this type of approach is that it involves using a reproducible and transparent framework for expressing uncertainty in the evidence and in the methods.

Hazard characterisation

At this step, evidence is integrated to select the critical effect(s) and identify a reference point (RP) for establishing the UL. As proposed in the guidance for establishing and applying ULs for vitamins and essential minerals (EFSA NDA Panel, 2022), when available data are not suitable for dose–response modelling, a no‐observed‐adverse‐effect level (NOAEL) or a lowest‐observed‐adverse‐effect level (LOAEL) can be identified and used as the RP. In view of the available BoE, this approach is applied. To derive the UL, an uncertainty factor (UF) is applied to the RP to account for the uncertainties associated with extrapolating from the observed data to the general population. ULs should be protective for all members of the general population, including sensitive individuals, throughout their lifetime. The rationale for the selection of the RP and UF are documented in Section 3.6 of the Opinion.

2.3. Dietary intake assessment (sQ8)

The assessment follows the approach outlined in the protocol for the intake assessments performed in the context of the revision of Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for selected nutrients (EFSA, 2022). It is briefly summarised below.

2.3.1. Data

Selenium intakes from foods, excluding food supplements, have previously been estimated for all population groups in the context of the Scientific Opinion on DRVs (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). Food intake data from the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database (hereinafter referred as Comprehensive Database) 2 and data on selenium content in foods from the EFSA food composition database (FCDB) 3 (Roe et al., 2013) were used. Given that the EFSA FCDB has not been updated since then and the number of national surveys that were newly integrated in the Comprehensive Database is limited, the intake estimates published in 2014 are still considered adequate for the purpose of the present assessment and were not updated, except for the addition of data for infants aged < 1 year (Section 2.3.2).

Regarding the use of selenium food supplements, data in the Comprehensive Database suffer from important limitations, in particular due to partial reporting in the database of the nutrient(s) contained in food supplements. In view of the uncertainties associated with these data, the Panel relied on information available at national level (see below).

To complement EFSA intake assessment from 2014, selenium intake estimates from natural sources, from addition to foods and from food supplements based on nationally‐representative food consumption surveys and Total Diet Studies (TDS) published after 2014 were collected. Data on selenium intakes from fortified foods and/or food supplements published before 2014 were also considered as the contribution of those sources was not addressed in EFSA's previous assessment. Data were collected between September and November 2021 by contacting 64 competent authorities in 37 European countries through EFSA Focal Points 3 An additional search in sources of bibliographic information (Google Scholar, PubMed) was performed to collect reports of national surveys included in the Comprehensive database which had not been obtained through the competent authorities.

The Mintel Global New Products Database (GNPD) 5 was used as a data source to identify the type of selenium containing food supplements and fortified foods available on the EU market. The search was limited to the past 5 years, from January 2016 to December 2021.

2.3.2. Methodology

EFSA intake estimates were calculated by matching the food intake data from the Comprehensive Database and the data on selenium content in foods from the EFSA FCDB as available in 2014 (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014) (Section 3.4.2). Data on intake estimates for infants (≥ 4 to < 12 months), which were not in the remit of the DRV Opinion from 2014, have been added to the present assessment. The methodology applied to estimate intakes in this population group is the same as for the other age groups.

Selenium intake data from recent national food consumption surveys and TDSs, including specific estimates of selenium intake from food supplements and/or fortified foods, were extracted.

Information on food products fortified with selenium and selenium‐containing supplements available on the EU market, and their selenium content as reported on the label, were extracted from the GNPD database. These data were used qualitatively to describe the types of fortified foods and food supplements available and to gain insight into their potential contribution to total selenium intake.

2.4. Public consultation

In line with EFSA's policy on openness and transparency, and for EFSA to receive comments from the scientific community and stakeholders, the draft Scientific Opinion was released for public consultation from 14 September 2022 to 19 October 2022. 6 The outcome of the public consultation is described in a technical report published as Annex F to this Scientific Opinion.

3. Assessment

3.1. Chemistry of selenium

Selenium (CAS number 7782‐49‐2) resembles sulfur in its organic and inorganic forms (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). Selenium is found in organic compounds, such as SeMet, selenocysteine (SeCys), dimethlyselenide (DMSe), dimethyldiselenide and Se‐methyl‐selenocysteine (MeSeCys), and inorganic forms, such as selenite (), selenide (Se2−), selenate () and elemental selenium (Mehdi et al., 2013; Naderi et al., 2021). The main inorganic selenium compounds, selenite and selenate, are water soluble, while elemental selenium is not (ATSDR, 2013). Selenium in a component of a number of selenoproteins which are mediating the biological effects of selenium and include glutathione peroxidases, thioredoxin reductases, iodothyronine deiodinases and selenoprotein P (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014).

3.2. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

The most abundant forms of selenium in the diet are organic, SeMet and SeCys in particular. Selenite and selenate (inorganic selenium compounds) normally represent a minor proportion of the overall dietary intake (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014; see Section 3.4.1). Brassica and Allium species are sources of the non‐proteinogenic selenium‐containing amino acids Se‐methyl‐selenocysteine (MeSeCys) and γ‐glutamyl‐Se‐methyl‐selenocysteine (γ‐Glu‐MeSeCys) (see also Section 3.4.1).

SeMet is a methionine analogue that may non‐specifically replace methionine in proteins. It can only be synthesised by plants but can be incorporated into proteins by plants and animals into the non‐specific protein pool. They are often referred to as selenium‐containing proteins, in contrast to selenoproteins (Combs, 2015).

SeCys, which is the only form of selenium used for selenoprotein synthesis (see Section 3.1), is co‐translationally synthesised from selenide and serine and can be integrated into peptides through in‐frame UGA codons in selenoprotein mRNA (Labunskyy et al., 2014). Plants generally do not have UGA‐encoded selenoproteins (White, 2018). With exception of some algae (Jiang et al., 2020), selenoproteins can only be synthesised in animals and some microorganisms (Beilstein and Whanger, 1986; Combs, 2015).

Human studies confirm that all forms of selenium are readily absorbed (Jäger et al., 2016a,b).

As evidenced by animal studies, selenium‐containing amino acids require the digestion of the respective proteins and are then absorbed through active transport (Combs, 2015). SeMet is absorbed with the involvement of intestinal methionine transporters, while the absorption of SeCys is less well studied (Burk and Hill, 2015), but might be absorbed in a similar way as cysteine (Ha et al., 2019). Selenite is absorbed via passive diffusion (Burk and Hill, 2015) and, when ingested in physiological amounts, is reduced in the intestinal mucosa cells to selenide. It is, therefore, not expected to occur as such in circulation (Burk and Hill, 2015). Selenate, on the contrary, is absorbed via a carrier‐mediated mechanism and can appear unchanged in blood (Combs, 2015; Ha et al., 2019) (Figure 3). The absorption of selenium can be influenced by other dietary components and is in the range of 50%–90% in humans (Burk and Hill, 2015).

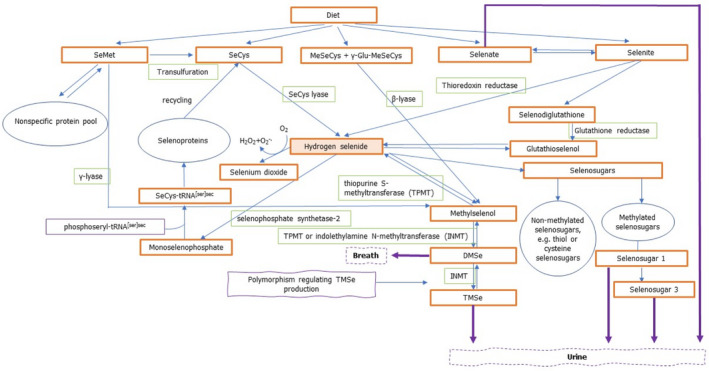

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of selenium metabolism

-

Based on Burk and Hill (2015), Combs (2015), Saito (2021), Jäger et al. (2016a,b), Thiry et al. (2012), and Rayman et al. (2008a).DMSe: dimethylselenide; γ‐Glu‐MeSeCys: γ‐glutamyl‐Se‐methyl‐selenocysteine; INMT: indolethylamine N‐methyltransferase; MeSeCys: Se‐methyl‐selenocysteine; SeMet: selenomethionine; SeCys: selenocysteine; TMSe: trimethylselenonium ion; tRNA: transfer ribonucleic acid; TPMT: thiopurine S‐methlytransferase.

Following absorption, the different selenium compounds are mostly transported to the liver (Ha et al., 2019). The liver is the principal site of selenium metabolism. The metabolites are then widely distributed to other organs and tissues such as pancreas, nervous system, skin and hair, bone, both skeletal and cardiac muscle, lungs and kidneys (ATSDR, 2013). These organs are variably affected by deficient and excessive intakes of selenium giving rise to site‐specific pathological and biochemical features (Alexander, 2022).

Evidence on the fate of selenium in the liver and subsequent transport to cells stems mainly from animal and in vitro studies. In the liver, all selenium compounds, except SeMet, MeSeCys and γ‐Glu‐MeSeCys, are metabolised to the common intermediate, hydrogen selenide (Figure 3).

SeMet can be metabolised via the transsulfuration pathway to SeCys or be randomly incorporated into the non‐specific protein pool (Burk and Hill, 2015). SeMet can also be metabolised to methylselenol by γ‐lyase in mouse liver (Suzuki et al., 2007; Thiry et al., 2012). However, it is uncertain if this conversion occurs in humans. Selenium deposited in the non‐specific protein pool can be released by the degradation of proteins and be used in the formation of selenoproteins as SeCys (Waschulewski and Sunde, 1988a,b).

MeSeCys and γ‐Glu‐MeSeCys are converted to methylselenol by β‐lyase which can be either metabolised to hydrogen selenide or further methylated for excretion (Suzuki et al., 2007; Thiry et al., 2012).

SeCys, either consumed as such or produced from SeMet, is transformed to hydrogen selenide and alanine by SeCys lyase (Burk and Hill, 2015). It is subsequently phosphorylated by selenophosphate synthase 2 to monoselenophosphate (H2SePO3) (Saito, 2021), which is used for conversion of phosphoseryl tRNA[ser]sec to SeCys tRNA[ser]sec that provides SeCys for insertion into selenoproteins during translation (Burk and Hill, 2015). SeCys is highly reactive and has not been found in free form in tissues, as SeCys lyase which catalyses the reaction from SeCys to hydrogen selenide keeps its level low (Burk and Hill, 2015; Plateau et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2019). In humans, there is no physiological pathway that allows SeMet to be synthesised from SeCys (Katarzyna et al., 2020).

Selenate is reduced first to selenite and then to hydrogen selenide through a series of redox reactions coupled to reduced glutathione or with the involvement of thioredoxin reductases (Burk and Hill, 2015).

Hydrogen selenide can be incorporated into selenoproteins, used in the formation of selenosugars or methylated for excretion as shown in a study on the human metabolic profile of urinary selenium (Lajin et al., 2016a).

From the liver, selenium is transported to tissues as SeCys mainly in selenoprotein P, the major selenium transport protein, but also in other selenoproteins (Burk and Hill, 2015). The distribution is differential, as some tissues, such as the brain and the testes, require more selenium than others for their function, as shown in animal studies (Ha et al., 2019). In in vitro studies it has been observed that in order to use selenium that had been transported by selenoprotein P, selenoprotein P is incorporated into cells where it is degraded in the lysosome and the liberated SeCys can be used in selenoprotein synthesis (Saito, 2021).

In plasma, selenium is also present as SeMet, which non‐specifically substitutes for methionine in plasma proteins, and as small molecules such as selenosugars (Burk and Hill, 2015).

Under physiological intakes, the assumption is that selenoproteins make up the majority of tissue selenium, but recent data in turkey liver suggest that the selenosugar 1 (β‐methylseleno‐N‐acetyl‐galactosamine; SeGalNac) comprises more selenium than all the selenoproteins combined (Katarzyna et al., 2020).

It has been shown that in turkey liver selenosugars can react with low‐molecular weight thiols and with cysteine‐containing peptides and proteins. Analysis of high‐molecular weight selenium species found that selenium was present as SeGalNac (selenosugar 1) linked to thiols on general body proteins. With high selenium supplementation, increased selenosugar formation occurred, further increasing these ‘selenosugar‐decorated proteins’, but also increasing selenosugar linked to low‐molecular weight thiols and the excretion of SeGalNac (selenosugar 1) in urine (Katarzyna et al., 2020).

Selenium elimination primarily occurs by urinary excretion (Sunde, 2012). The main human urinary selenium metabolites are the selenosugars 1 and 3, trimethylselenonium ion (TMSe) and, depending on the selenium compound consumed, selenate and selenium‐methylselenoneine, the latter originating most likely from methylation of selenoneine in fish (Hadrup and Ravn‐Haren, 2021). A considerable part of excreted selenium is in the form of yet unidentified metabolites. The amount of identified and unidentified selenium metabolites in urine is dependent on the selenium compound ingested, on the dose and on the individual genetic background (Kuehnelt et al., 2007; Jäger et al., 2016a,b).

TMSe is produced following methylation of hydrogen selenide first to methylselenol (driven by thiopurine S‐methyltransferase (TPMT)), then to DMSe (driven by either TPMT or indolethylamine N‐methyltransferase (INMT)) and finally to TMSe (driven by INMT). A genetic polymorphism in the human INMT gene results in the fact that some individuals are not able to excrete TMSe in substantial amounts (TMSe non‐eliminators) (Lajin and Francesconi, 2016). It has been suggested that conversion of hydrogen selenide to methylselenol and to DMSe takes place in the liver, while the urinary metabolite TMSe is produced from DMSe in the lungs (Fukumoto et al., 2020). This would explain why following ingestion of large amounts of selenium, when the ability of the lung to convert DMSe into TMSe is exceeded, DMSe is exhaled in breath. There is indication that TMSe eliminators excrete TMSe in addition to other selenium metabolites and eliminate more selenium than TMSe non‐eliminators (Kuehnelt et al., 2015; Lajin et al., 2016a). The Panel notes that the reduced capacity of TMSe non‐eliminators to excrete excess selenium in urine might make them more susceptible to selenium toxicity compared with TMSe eliminators. However, current evidence is inadequate to confirm this hypothesis.

In TMSe non‐eliminators, selenosugars 1 and 3 are the predominant selenium metabolites in urine, while TMSe seems to be more prominent in TMSe eliminators (Lajin et al., 2016b). Selenosugar 2 is present usually only in trace amounts and is only detected when selenium intakes are high. For example, selenosugar 2 has been reported to be present in urine in individuals who had been supplemented with 8,000 μg/day SeMet for 7 days and thereafter 4,000 μg/day with urine collections up to day 30 of supplementation (Kuehnelt et al., 2007; Lajin et al., 2016b). With increasing selenium intakes, selenosugar 1 becomes more prominent while the selenosugar 3 rise is less pronounced. The ratio of selenosugar 3 to total urinary selenium metabolites tends to reach a plateau at around 5%, while that of selenosugar 1 to total urinary selenium metabolites continues to rise and stabilises at around 70% (Lajin et al., 2016a).

Selenium ingested as selenate given at a single dose of 50 μg was mostly excreted unmetabolised in humans (Jäger et al., 2016a). Small amounts of ingested selenite are also excreted as selenate, indicating that a fraction of selenite is oxidised to selenate following intake (Jäger et al., 2016b).

Figure 3 provides a schematic overview of selenium metabolism in humans.

3.3. Biomarkers of intake

3.3.1. Characteristics of selenium biomarkers

Several biological markers have been proposed as potential markers of selenium exposure. High correlations (r = 0.63–0.96) between selenium dietary intake, as estimated from duplicate food portions, and single measurements from whole blood, 2‐h‐urine, serum/plasma, hair and (toe)nail samples have been reported (Yang et al., 1989a; Longnecker et al., 1996). The characteristics of selenium biomarkers are described in Appendix A, together with their strengths and limitations regarding their use as biomarkers of selenium dietary intake.

Dietary selenium intake is the major determinant of whole blood/serum/plasma selenium concentrations in non‐occupationally exposed individuals. Serum/plasma selenium concentrations and, to a lesser extent, whole blood selenium concentrations, are the most commonly used biomarkers of selenium intake in epidemiological studies and reflect short/medium term exposure. 7

Some equations have been published to estimate selenium intake from whole blood/serum/plasma selenium concentrations. These equations have been developed using data collected in specific populations. Some approximate conversion factors have also been proposed based on observational evidence (Haldimann et al., 1996).

Other markers that have been used include urinary selenium (short term exposure), nail and hair selenium concentrations (medium/long term exposure 8 ).

Glutathione peroxidases are selenoproteins which are part of the human antioxidant network. Measures of glutathione peroxidase activity in plasma (glutathione peroxidase 3) and other blood compartments (glutathione peroxidase 1 activity in platelets and RBCs; whole blood glutathione peroxidase activity) have been commonly used as biomarkers of selenium status (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). Selenoprotein P has a central role in selenium storage and transport and has also been used as a biomarker of selenium status (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). The utility of these markers as biomarkers of intake is limited to the lower range of selenium intake as they reach a plateau as selenium intake increases (glutathione peroxidases were found to reach maximum activity at an intake of 40–60 μg/day (Yang et al., 1987; Duffield et al., 1999; Xia et al., 2005; Xia et al., 2010), while plasma selenoprotein P was found to reach such a plateau with selenium intakes of 60–70 μg/day (Duffield et al., 1999; Persson‐Moschos et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2010); in addition, these proteins are upregulated by oxidative stress, and therefore their levels and activity may increase as a response to free radicals even in the absence of any change in selenium supply.

3.3.2. Dose–response relationship between selenium intake and plasma/serum selenium concentration

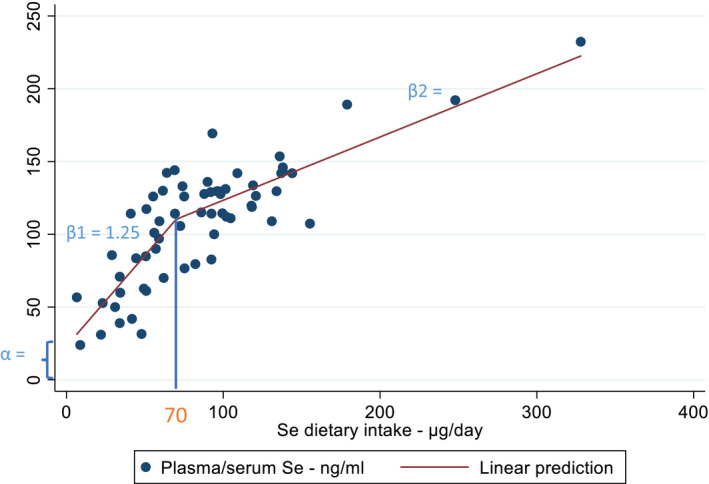

A dose–response meta‐analysis was conducted by EFSA to characterise the relationship between mean selenium intake and mean selenium plasma concentrations. The method and results are summarised below. More details are given in the technical report in Annex B.

Data points from studies in which the standard error (SE) of the mean values was not available or could not be calculated were excluded from the analysis. For each study only results from one analysis among alternative ones were chosen (e.g. overall vs. sex‐specific estimates). After sensitivity and subgroup analyses were conducted, 63 pairs of mean values and related standard errors (plasma concentrations and intakes) from 39 studies were included in the final set for the dose–response analysis. The data points corresponding to the intervention phase of trials (25 data points) were excluded as, in a sensitivity analysis, the slope obtained using datapoints from only this subgroup was much different from the slope obtained from analysis of datapoints originating from observational settings (i.e. observational studies, baseline characteristics of participants in intervention studies), possibly due to the manipulation of the diet for relatively short periods. Therefore, intake estimates corresponded to intakes from mixed diets containing different selenium compounds.

The shape of the relationship was explored by applying linear splines; these were considered a convenient way of capturing the non‐linearities in the relationship while keeping the conversion process simple. Different numbers and types of knots were tested, including one at 70 μg/day which is the AI for selenium established by the NDA Panel in 2014 (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). This knot was finally chosen as it corresponded to the best fitting model. Accordingly, the model estimated two different slopes depending on whether the intake values were below or above the cut‐off of 70 μg/day and related constant terms.

The estimated coefficients were 1.25 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88, 1.61) below 70 μg/day and 0.43 (95% CI: 0.29, 0.58) above 70 μg/day, with a constant term for the first spline of 23.10 (95% CI: 1.92, 44.28) and a constant term for the second spline of 79.90 (95% CI 58.72, 101.08) – not shown (Figure 4); at 70 μg/day of mean selenium intake the predicted mean plasma concentrations were 99 (95% CI: 93, 105) μg/L in the linear meta‐regression model (not shown) and 111 (95% CI 102, 119) μg/L in the non‐linear model (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dose–response meta‐analysis on the relationship between mean selenium intakes and mean selenium plasma concentrations. At 70 μg/day one knot was identified from the best fitting linear splines model and coefficients estimated below and above such a cut‐off (β1 = 1.25, β2 = 0.43, α = 23.10)

- Se: selenium.

The outcome of the stratified and sensitivity analyses conducted on this model are presented in Annex B.

3.4. Intake assessment

3.4.1. Sources of dietary selenium

Dietary selenium from plant and animal sources occurs mainly as organic compounds, primarily SeMet and SeCys (Rayman et al., 2008a; Cubadda et al., 2010; Fairweather‐Tait et al., 2011; Rayman, 2012; Mehdi et al., 2013). Almost 90% of selenium in (non‐selenium‐enriched) plants is present as SeMet (Burk and Hill, 2015). In food of animal origin, SeMet is also present as a major species alongside SeCys specifically incorporated into selenoproteins (Bierla et al., 2008a,b; Lipiec et al., 2010). In fish, SeMet or selenoneine are the major selenium forms depending on the fish species (Yamashita and Yamashita, 2010; Sele et al., 2018).

The richest food source of selenium are Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa). Mean concentrations between 5 and 72 μg/g dry weight (up to 400 μg/nut) have been reported in samples collected in Brazil and the Amazon Basin, indicating large variability depending on their region of production (Pacheco and Scussel, 2007; Cardoso et al., 2017). There may be high seed‐to‐seed variation in selenium content within commercially available batches (Lima et al., 2019).

Other rich foods of selenium include offals (e.g. mean content in kidney (pig, lamb, beef: 1–3 μg/g)) and fish and crustaceans (e.g. mean content in tuna: 1–3 μg/g; shrimps, crabs, prawns: 1–2 μg/g) (Anses, 2020; Public Health England, 2021; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, 2022).

In EFSA's intake assessment of selenium in European populations, the main food groups contributing to selenium intake were found to be milk and dairy products, meat and meat products, grains and grain‐based products and fish and fish products (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014) (see also Section 3.4.2).

There is a large variability in the selenium concentration of foods, which depends, to a large extent, on where crops and fodder are grown (Johnson et al., 2010; Mehdi et al., 2013). The amount of selenium available in soil is a major determinant of the amount of selenium in the plant foods. Seleniferous soils are present in parts of the United States, Canada, South America, India, China and Russia, while New Zealand, some parts of China, Nordic European countries and parts of Eastern Europe are characterised by selenium content in soils which are lower than the average content worldwide (Combs, 2001; Oldfield, 2002). Other factors affect the uptake of selenium into plants, such as soil pH, rainfall or microbial activity (Mora et al., 2015).

Selenium in water is mainly present as inorganic compounds, predominantly as selenate (WHO, 2011; LeBlanc et al., 2018). As per Directive (EU) 2020/2184 9 the parametric value for the selenium content of drinking water is 20 μg/L in the EU, which can be increased to 30 μg/L in regions where geological conditions could lead to high levels of selenium in groundwater.

Selenium‐enriched foods

Food items with an artificially increased content of selenium can be produced by means of selenium‐enriched fertilisers or growth medium. They are hereinafter referred to as selenium‐enriched foods (sometimes called selenised or biofortified foods in the literature). Examples include selenised wheat, garlic, onion, broccoli, potatoes and selenised yeast (Demirci et al., 1999; Heard et al., 2004; Fisinin et al., 2008; Fairweather‐Tait et al., 2011).

Soil enrichment is usually performed with inorganic selenium salts (selenate, rarely selenite, e.g. as sodium salt). In most plants, inorganic selenium is taken up and biotransformed into SeMet. For example in cereal grains grown in areas with selenium‐rich soil, the major selenium compound is protein‐bound SeMet. Inorganic selenium and water soluble low molecular weight seleno‐compounds, including selenosugars, are also present and are non‐protein bound (Aureli et al., 2012). In plants of the Brassica genus (e.g. broccoli) and the Allium genus (e.g. onion and garlic) enrichment with inorganic selenium results in the biosynthesis of notable amounts of the non‐protein selenoamino acids MeSeCys and γ‐Glu‐MeSeCys (Rayman et al., 2008a).

Se‐yeast is the most widespread selenium‐enriched source and contains predominantly SeMet, with a large variety of other organic species present as minor compounds (Fairweather‐Tait et al., 2011; Bierla et al., 2012; Bierla et al., 2018).

Fortified foods

The selenium content of foods can be increased by its addition to foods during processing (hereinafter referred to as fortified foods). In the EU, sodium selenate, sodium hydrogen selenite, sodium selenite, and Se‐yeast are authorised for addition to foods 10 and foods for specific groups. 11

The Mintel GNPD database 12 was used to identify foods and beverages to which selenium has been voluntarily or mandatorily added in the EU market in the last 5 years (from January 2016 to December 2021). A total of 1,847 packaged food products available in 22 EU Member States (MSs) and Norway were identified as containing added selenium in the ingredient list. The majority of the products belong to the Mintel categories ‘baby foods’ 13 (41%) and ‘nutritional drinks & others’ (34%). Most products were found in Germany, Italy, France and Spain. Data on selenium content per serving based on labelled information were available for 19% of the products. Among those, this information was available for 2% of ‘baby foods’ only (n = 18): range 1.5–11 μg selenium per serving (median = 5.7 μg selenium); and 29% of ‘nutritional drinks & others’ (n = 179): range 6.4–165 μg selenium per serving (median = 18 μg selenium), with the highest contents per serving reported in some weight management products such as meal replacement shakes.

Food supplements

In the EU, authorised forms of selenium for use in food supplements are sodium selenate, sodium hydrogen selenite, sodium selenite, Se‐yeast, L‐SeMet and selenious acid. 14

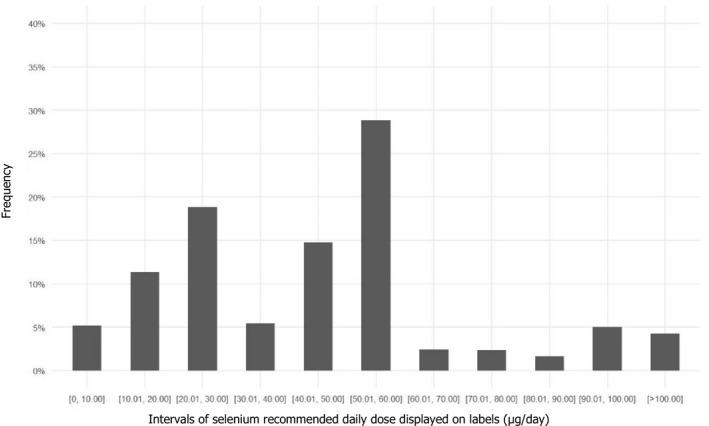

The Mintel GNPD database was used to identify selenium containing food supplements present in the EU market in the last 5 years (from January 2016 to December 2021). The Mintel category ‘vitamins and dietary supplements’, including supplements formulated for special nutrition needs such as ‘maternal & infants nutrition’ and ‘performance nutrition’, was searched. It yielded a total of 1,238 products available in 24 EU MSs and Norway. Most of the products were found in Germany, France and the Netherlands. The labelled recommended daily dose ranged from 2.5 up to 220 μg of selenium, with an average of 49 μg per daily dose (median 50 μg per daily dose) (Figure 5). A proportion of 15% of the food supplements contain ≥ 70 μg per daily dose, which is the AI for selenium in adults, and 4% contain > 100 μg per daily dose. Among selenium containing products, only 2.6% were single‐nutrient supplements.

Figure 5.

Distribution of selenium‐containing supplements available in EU Member States and Norway according to the recommended daily dose displayed on labels

- Source: Mintel GNPD database. Search for selenium‐containing supplements available in the EU market in the last 5 years (from January 2016 to December 2021). A total of 1,238 products available in 24 EU Member States and Norway were identified.

3.4.2. EFSA's intake assessment

Selenium intakes from food sources (excluding food supplements) in European populations were calculated in the context of the Scientific Opinion of DRVs for selenium, based on the data from the EFSA Comprehensive Database and the EFSA FCDB (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). Food consumption surveys of Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands and Sweden were used for the assessment. The period of data collections covered by the surveys ranged between 2000 and 2012. Further information on the characteristics and methods used for the data collection in the respective surveys are provided in Annex C.

Food composition data from Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK were used to calculate selenium intake in these countries. For nutrient intake estimates of Ireland and Latvia, food composition data from the UK and Germany, respectively, were used, because no specific composition data from these countries were available. The proportion of borrowed selenium values in the five composition databases varied as follows: Germany 100%, Italy 91%, the UK 68%, Finland 58% and the Netherlands 50%.

The intake assessment of 2014 did not distinguish between selenium ‘naturally present’ or ‘added’ to foods by manufacturers. As data on the consumption of foods fortified with selenium available in the Comprehensive Database 15 and on the concentration of selenium in fortified foods available in EFSA FCDB database are scarce, EFSA's intake estimates can be considered to reflect selenium intake from natural sources.

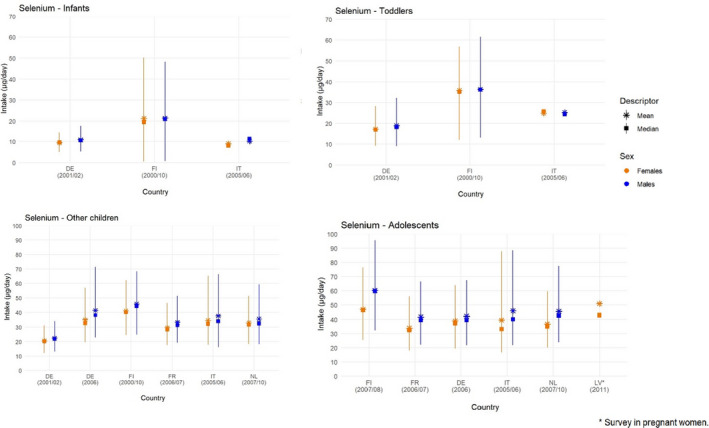

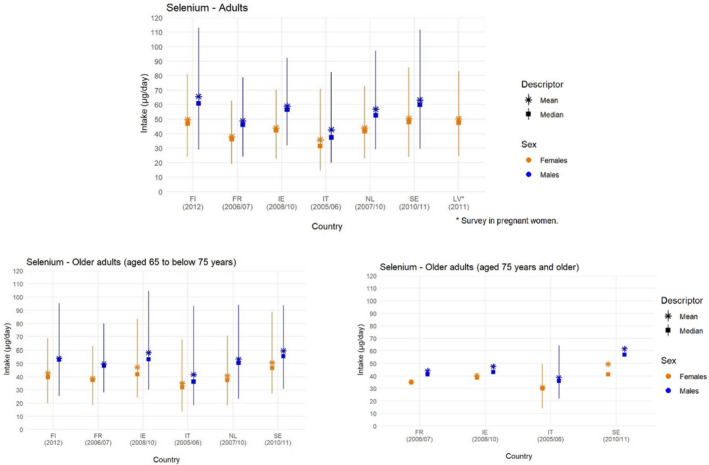

The estimated distributions of intake are presented below by age group, sex and country of origin (Figures 6 and 7). A summary overview, providing the ranges of means and 95th percentiles (P95) across EU surveys is given in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Mean, median, 5th and 95th percentiles of selenium intakes in infants (< 1 year old), toddlers (≥ 1 year to < 3 years old), other children (≥ 3 years to < 10 years old) and adolescents (≥ 10 years to < 18 years old), by sex and country

-

Lines represent the range between the 5th and 95th percentiles. Estimated intakes from 5th and 95th percentiles are not presented when sample size is below 60 participants.DE: Germany; FI: Finland; FR: France; IT: Italy; LV: Latvia; NL: Netherlands.Source: (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014), except for infants.

Figure 7.

Mean, median, 5th and 95th percentiles of selenium intakes in adults (≥ 18 years to < 65 years old) and older adults (≥ 65 years), by sex and country

-

Lines represent the range between the 5th and 95th percentiles. Estimated intakes from 5th and 95th percentiles are not presented when sample size is below 60 participants.FI: Finland; FR: France; IE: Ireland; IT: Italy; LV: Latvia; NL: Netherlands; SE: Sweden.Source: (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014).

Table 3.

Minimum and maximum mean values and 95th percentiles of selenium daily intake from food sources (supplement use excluded) across European dietary surveys by population group and sex

| Population group, age range (mo, y) (n of surveys) | Selenium (μg/day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Mean | P95 | Mean | P95 | |||||

| Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | |

| Infants, ≥ 4 to < 12 mo (3) | 10.2 | 21.4 | 17.7 | 48.3 | 9.0 | 21.2 | 14.5 | 50.2 |

| Toddlers, ≥ 1 to < 3 y (3) | 18.9 | 36.3 | 32.2 | 61.6 | 17.2 | 35.8 | 28.3 | 56.9 |

| Other children, ≥ 3 to < 10 y (6) | 22.5 | 45.9 | 33.9 | 71.5 | 20.6 | 41.1 | 31.3 | 65.2 |

| Adolescents, ≥ 10 to < 18 y (5) | 41.6 | 60.3 | 66.5 | 95.5 | 33.9 | 46.9 | 55.9 | 87.8 |

| Adults, ≥ 18 to < 65 y (6) | 42.7 | 65.6 | 78.8 | 113.0 | 35.8 | 50.5 | 62.7 | 85.4 |

| Older adults, ≥ 65 to < 75 y (6) | 41.6 | 59.6 | 80 | 104.4 | 35.0 | 50.7 | 62.8 | 88.6 |

| Older adults, ≥ 75 y (4) | 38.8 | 61.7 | 64.6 (a) | 64.6 (a) | 31.0 | 49.5 | 49.6 (a) | 49.6 (a) |

| Pregnant women (1) | 50.3 | 50.9 | 82.9 (a) | 82.9 (a) | ||||

mo: months, n: number, P, percentile; y: years.

95th percentiles calculated only for 1 survey.

Source: (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014), except for infants.

Across population groups, the main food groups contributing to selenium intake were milk and dairy products, meat and meat products, grains and grain‐based products and fish and fish products, with minor differences between sexes (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014) (Annex C).

When available, EFSA selenium intake estimates were compared with values from the same national surveys published in the literature (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). EFSA average selenium intake estimates were similar to the published results from the Dutch national food consumption survey (van Rossum et al., 2011) (± 5% difference), while EFSA values were up to 25% higher than the published results from the Swedish Riksmaten survey (Amcoff et al., 2012) and up to 20% lower than the published values from the INCA 2 survey in France (AFSSA, 2009), the FINDIET 2012 survey (Helldan et al., 2013) and NWSSP study in adolescents (Hoppu et al., 2010) in Finland. As previously discussed (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014), several factors may contribute to these differences, including discrepancies in mapping food consumption data according to food classifications and in nutrient content estimates available from the food composition tables, as well as different intake modelling methods. The lower estimates for Finland may be due to borrowed values lower than the selenium contents of Finnish foods that were used in the intake assessments at the national level owing to the national selenium enrichment programme implemented in Finland. As the intake calculations rely heavily on estimates of both food composition and food consumption, it is not possible to conclude which of these intake estimates would be closer to the actual selenium intake.

3.4.3. Complementary information from national reports

3.4.3.1. Intake data of selenium from foods and fortified foods

Nationally representative consumption surveys and TDSs published after the surveys included in EFSA's intake assessment were collected. Survey characteristics, mean and P95 intake estimates are presented in Annex D. Key information is summarised below.

Intake estimates from national consumption surveys

Reports from national consumption surveys providing estimates of selenium intake from foods and fortified foods (excluding food supplements) are available for 10 countries: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Lithuania, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands (Pedersen et al., 2015; Hansen et al., 2016; AECOSAN, 2017; Anses, 2017; Hansen et al., 2017; Lemming et al., 2018; Valsta et al., 2018; Mitsopoulou et al., 2020; van Rossum et al., 2020; Bulotaitė et al., 2021; Kukk et al., 2021; Mitsopoulou et al., 2021). At the P95, the estimated intakes are up to 80.9 μg/day in male infants (aged ≥ 3 to < 12 months; 3 countries), up to 108.6 μg/day in female toddlers (1 to < 3 years; 5 countries), up to 153.3 μg/day in male other children (3 to < 10 years; 5 countries), up to 183.7 μg/day in female adolescents (10 to < 18 years; 6 countries) and up to 227.7 μg/day in male adults (≥ 18 years; 6 countries). The highest P95 values in all age groups are reported in the Third Individual and National Survey on Food Consumption in France (INCA 3). However, the report of the INCA3 survey (Anses, 2017) stressed large uncertainties related to the food composition tables used for the selenium intake assessment.

Intake estimates from total diet studies

TDS data from Ireland and the Czech Republic were collected (FSA, 2016; Státní zdravotní ústav, 2021). Unpublished data from the Italian TDS were also obtained (F. Cubadda, personal communication, November 2021). At the P95, selenium intakes from food consumption only in males (i.e. without food supplements and fortified foods) are up to 64 μg/day in toddlers (1 to < 3 years; one country), up to 116 μg/day in other children (3 to < 10 years; two countries), up to 144 μg/day in adolescents (10 to < 18 years; one country) and up to 142 μg/day in adults (≥ 18 years; two countries). Consistent with other results, intakes are slightly lower in females than in males. For all age groups, the highest P95 values are found in the Italian TDS.

Contribution of fortified and enriched foods

The majority of the survey reports did not distinguish between selenium intake from natural sources and intake resulting from selenium addition to foods (fortified foods). One report on two national surveys in Estonia, involving children and adults, respectively, estimated selenium intake from fortified foods only (Kukk et al., 2021). Only 1.5% of the total eating occasions included information on fortification. Boys aged 1–9 years was the only population group for which a contribution of fortified foods (0.1 μg selenium per day) could be detected. Challenges related to data gaps in food composition databases particularly for foods fortified with selenium were noted. In the report from the DNFCS 2007–2010 (van Rossum et al., 2011), the estimated contribution of foods fortified with selenium to total intake of selenium was negligible (< 1%).

Regarding selenium‐enriched foods (Section 3.4.1), the addition of sodium selenate to the main fertilisers became mandatory in 1984 in Finland, as a way to enrich the selenium content of local food products, because of the low selenium content of Finnish soils. Following this public health measure, the mean selenium intake in the Finnish population increased from 38 μg/day before enrichment policy to 80 μg/day in 2001 (Rayman et al., 2008a). In other EU MSs, some selenium‐enriched foods may be present on the market (e.g. selenised potatoes). However, data on the contribution of these foods to selenium intake are lacking.

3.4.3.2. Intake data of selenium from food supplements

Information on selenium intake from food supplements are available for six countries: Norway (Totland et al., 2012; Hansen et al., 2016; Hansen et al., 2017; Astrup et al., 2020; Paulsen et al., 2020), Sweden (Lemming et al., 2018), Finland (Valsta et al., 2018), the Netherlands (van Rossum et al., 2020), Estonia (Kukk et al., 2021) and Poland (Stos et al., 2021). Study characteristics and intake estimates are presented in Annex D.

Intake of selenium from foods supplements in the whole population

Six national dietary surveys from Estonia, the Netherlands and Norway provide information on the contribution of selenium‐containing food supplements to total selenium intake in the whole study population, in different age groups (Table 4). The contribution is estimated to be ≤ 8% for toddlers, children and adolescents in the three countries. Among adults, the contribution ranges between 2% and 4% (adult women in Estonia) and 19% (adult women aged 51–79 years in the Netherlands).

Table 4.

Percent contribution of food supplements to total selenium intake in whole survey population

| Country | Dietary method (N of days) | Sex |

Contribution of supplements to total mean selenium intake % (age) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toddlers | Other children | Adolescents | Adults | Elderly | |||

| Survey name (N subjects) | |||||||

| Reference | |||||||

|

Estonia National Dietary Survey in Children and Adults 2013–2015 1 (n = 4,646) (Kukk et al., 2021) |

24‐h recalls (2‐d); food records (2‐d) 2 |

m |

2–5 (1–9 y) |

1–1.5 (10–17 y) |

2–4 (18–64 y) |

2–3 (65–74 y) |

|

| f |

3–4 (1–9 y) |

2–5 (10–17 y) |

5–9 (18–64 y) |

3–7 (65–74 y) |

|||

|