Abstract

To describe an esthetic orthodontic treatment using aligners in an adult patient with dental class II malocclusion associated with crowding. A 25‐year‐old female patient with skeletal class I, bilateral class II relation, increased overjet and overbite and crowding in both arches presented for orthodontic treatment. The patient refused conventional fixed multibracket treatment in favor of aligners. Pre‐ and post‐treatment records are presented. Treatment objectives were achieved in 10 months, and the patient was satisfied with the functional and esthetic outcomes. Combining aligners with appropriate attachment location and geometry is an efficacious means of resolving orthodontic issues such as class II malocclusion in a time frame comparable to that of conventional fixed orthodontics. Staging in distalization increases the predictability of movement. Furthermore, this system is associated with optimal oral hygiene and excellent esthetics.

Keywords: adult orthodontics, attachments, case report, class II, clear aligners, distalization, Invisalign, staging

Distalization of full cusp class IIs always poses therapeutic challenges, more so with clear aligner therapy. This case report illustrates efficient class II correction with CA by judicious use of short class II elastics, 14‐day aligner change, sequential distalization by optimizing staging prescriptions, and efficient anchorage planning with attachment protocols.

1. INTRODUCTION

The global prevalence of class II malocclusions in permanent dentition is 19.56% [2–63%]. It is considered to be the second most common malocclusion and the most common malocclusion in Caucasian adults. 1 Many treatment options are available for the correction of class II malocclusion in adult patients including extractions, lower molar protraction and upper molar distalization. 2 , 3

Nowadays, there is an increasing demand for esthetic treatment among both adolescents and adults. The scope of Clear Aligner Therapy (CAT) has improved dramatically over the past decade. Originally directed toward the correction of mild orthodontic problems in adults, 4 , 5 this approach became more challenging when applied to complex anteroposterior discrepancies and orthodontic movements such as posterior intrusion, anterior extrusion, and torquing. 2

Obviously, successful treatment with clear aligners involves much more than moving teeth virtually by a software. 6 , 7 The application of adjunctive biomechanics through the addition of orthodontic attachments, elastics, and other devices and features has certainly created more individualized options for more predictable tooth movement across a wider range of malocclusions. 8 , 9 , 10

Though scholarly literature for treating complex cases is still in its early phase, published case reports have demonstrated satisfying outcomes with complex cases, such as those involving class II malocclusions. 10 , 11 , 12

Furthermore, the precision of movements has improved exponentially in recent years reaching values of 70%–80% due to the continuous research performed by Align Technology and the incorporation of attachments and auxiliaries in the treatment protocols. 13 Moreover, the predictability of crowding resolution with aligners was shown recently to be high. 14

On another note, considering that patients treated with CAT have experienced better quality of life scores and better oral hygiene during treatment, clinicians are driven to proceed further with the treatment of challenging cases using CAT. 15

To quantify the amount of tooth movement by CAT, 2D lateral cephalograms and different digital model registration software have been utilized. 16 , 17

This case report describes a case with an effective staging protocol and attachment geometry planning with the Invisalign system in an attempt to correct class II malocclusion in an adult patient.

2. CASE DESCRIPTION

2.1. Case history

A 25‐year‐old female patient presented for treatment with the chief complaint of forwardly placed upper front teeth. All specific patient information was de‐identified. No relevant medical, family, and pyschosocial history including relevant genetic information was reported. The patient did not undergo any previous orthodontic treatment.

2.2. Clinical findings

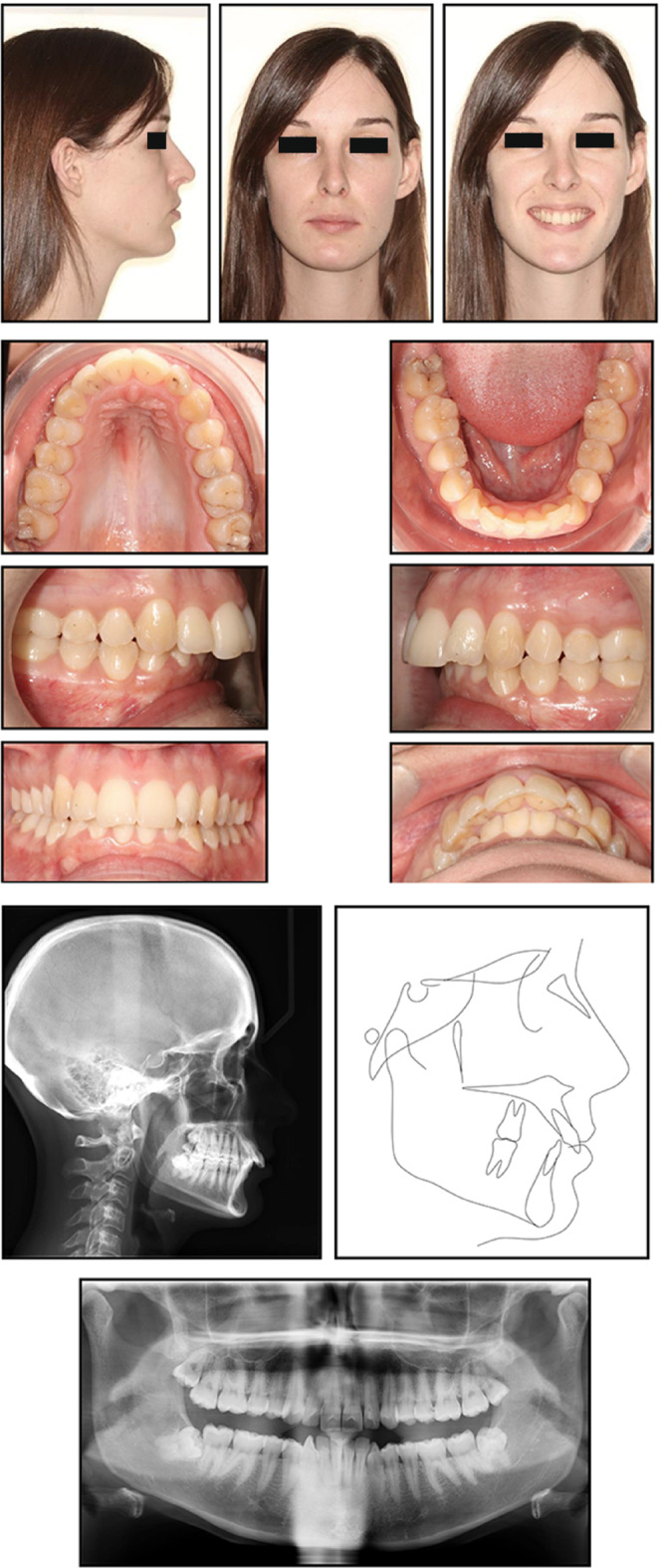

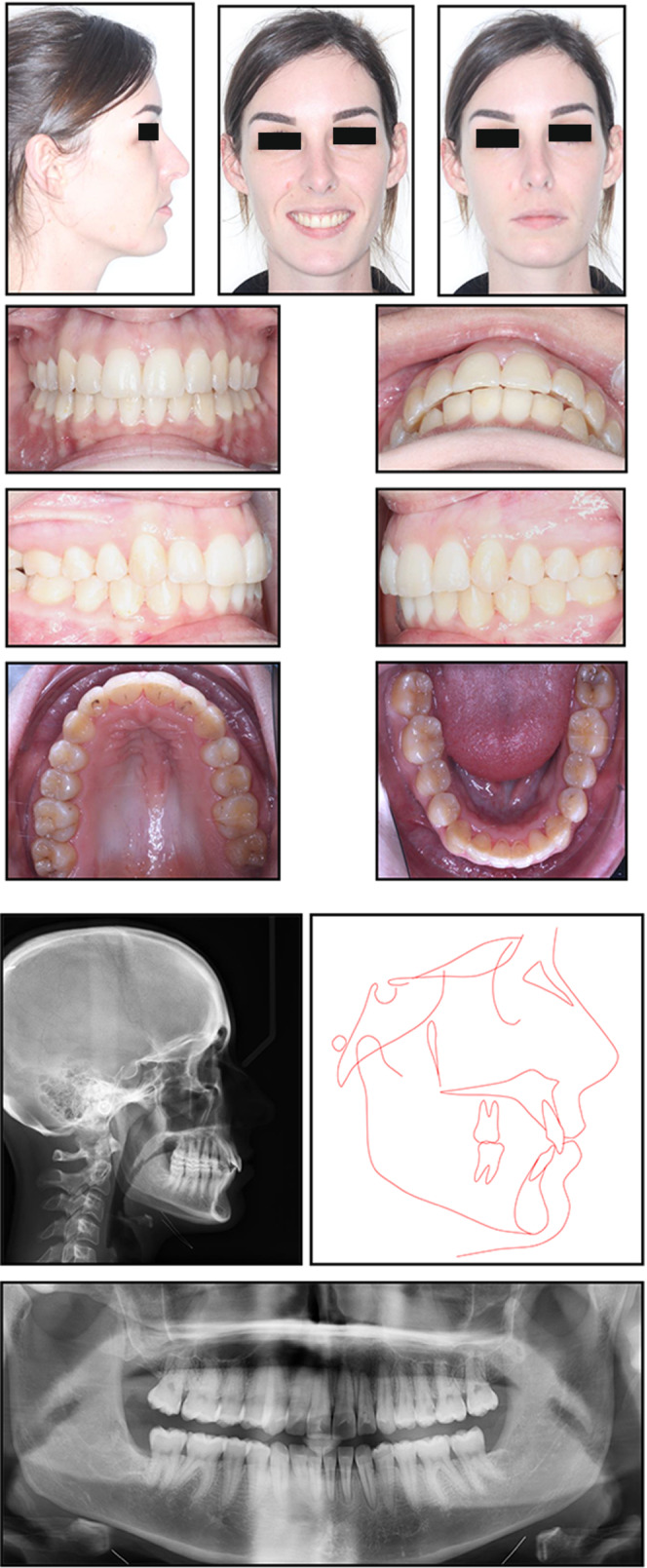

Extraoral clinical examination at rest revealed facial symmetry with equal vertical facial thirds. The smile analysis showed a coincident upper dental midline with the facial midline, a high lip line with increased gum show, and a straight smile arc. The patient presented with a mild convex profile with average clinical FMA and a protrusive upper lip with potentially competent lips. Intraoral examination revealed class II canine and molar relationship bilaterally and increased overjet of approximately 10 mm, deep impinging bite and coincident upper and lower dental midlines. The arch forms were V‐shaped in the upper arch and ovoid in the lower arch. Arch length tooth size analysis showed crowding in the upper arch of 2 mm and crowding in the lower arch of 6 mm. Periodontal biotype and oral hygiene were fair. No signs of parafunctional habits were recorded.

2.3. Radiographic diagnostic assessment

Panoramic radiography revealed full dentition, lack of bone defects, no periapical lesions and no temporomandibular joint abnormalities, with the presence of four wisdom teeth (Figure 1). Cephalometric analysis (Table 1) revealed a Skeletal class I base with an average ANB angle and normal facial height with an average growth pattern. Dentally, the upper incisors were forwardly positioned and proclined, while the lower incisors were upright with a decreased interincisal angle. Soft tissue analysis showed an acute nasolabial angle with a protrusive upper lip. The patient's Angle classification was dental class II division 1 with upper segments positioned anteriorly.

FIGURE 1.

Pre‐treatment records: Extraoral photos, intraoral photos, panoramic radiograph, lateral cephalometric radiograph, and tracing

TABLE 1.

Cephalometric analysis pre‐ and post‐treatment

| Parameter | Pre‐treatment | Post‐treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | |||

| 1 | SNA | 810 | 810 |

| 2 | SNB | 790 | 790 |

| 3 | ANB | 20 | 20 |

| 4 | WITS APPRAISAL | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 5 | FMA | 210 | 220 |

| 6 | GONIAL ANGLE | 1160 | 1160 |

| 7 | ODI | 74 | 77 |

| Dental | |||

| 8 | U1‐NA‐LINEAR | 9 mm | 1 mm |

| 9 | U1‐NA‐ANGULAR | 320 | 120 |

| 10 | L1‐NB‐LINEAR | 2.5 mm | 5 mm |

| 11 | L1‐NB‐ANGULAR | 250 | 340 |

| 12 | IIA | 1240 | 1270 |

| Soft tissue | |||

| 13 | NLA | 1060 | 1110 |

| 14 | U LIP – E PLANE | −2 | −4 |

| 15 | L LIP – E PLANE | −1 | −2 |

2.4. Treatment objectives and treatment plan

The primary treatment objectives were to achieve class I canines and molar bilaterally and reduce the overjet and overbite. Additional objectives were to relieve the crowding in both arches, correct the upper arch form, restore a pleasant smile with optimal lip line and smile arc, achieve lip competency and enhance the patient's profile. It was desirable to reduce the overjet and correct the class II relation by distalizing the upper molars and retracting the upper incisors. Since the patient presented with a deep bite, measures to prevent bite deepening were undertaken. The patient had high esthetic demands and asked for more esthetic alternatives to fixed appliance therapy. A treatment approach with clear aligner therapy was the appliance of choice using Invisalign aligners (Align Technology Inc, Santa Clara‚ CA‚ USA). All procedures have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in an appropriate version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Therapeutic intervention

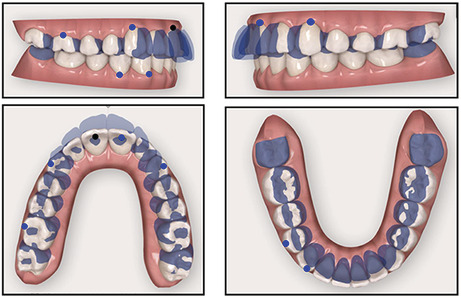

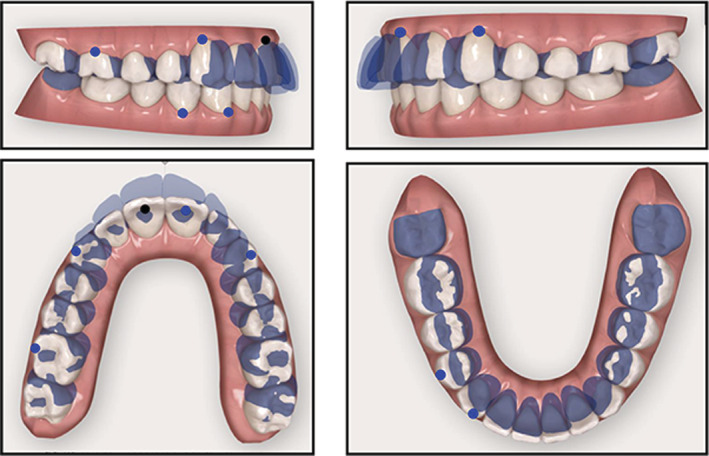

The patient was referred to the surgeon to extract wisdom teeth before the start of treatment. The ClinCheck virtual setup dictated 44 steps for each arch (Figure 2). In the upper arch, sequential distalization was planned to gain space for the retraction of incisors, achieving optimal overjet and class I canine and molar relationships bilaterally. Attachments were planned on most of the teeth to guide their movement and control their axes. Vertical attachments were planned for molars and premolars to avoid tipping and aid in bodily movement. The paired vertical root control attachments on the canines bilaterally were placed to help achieve bodily movement and control their long axes during distalization. Horizontal attachments were planned on upper incisors for extra retention and firmer grip of the aligner and for aiding in intrusion.

FIGURE 2.

ClinCheck virtual setup

Class II elastics (3/16 inch, heavy force 4.5 oz) were used to augment the movement. The elastics extended from the upper premolars to lower molars. The benefit of using short class II elastics is to prevent any clockwise rotation and bite deepening that might happen due to the extrusion of anterior teeth. Intermaxillary elastics were hooked from notches in the upper aligners at the first premolar to buttons that were bonded on the lower molars. The lower arch crowding was relieved by the expansion effect of the aligners and the proclination of the lower incisors. The patient was instructed to wear each aligner for 22 h per day and to move on to the next one in the series after 14 days. Mid‐treatment records are presented in (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mid‐treatment intraoral records

2.6. Treatment outcomes and follow‐ups

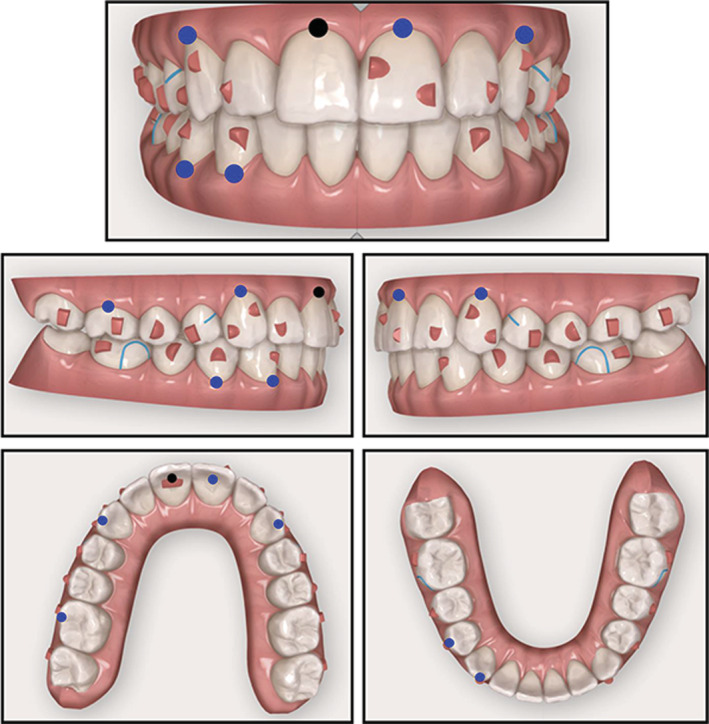

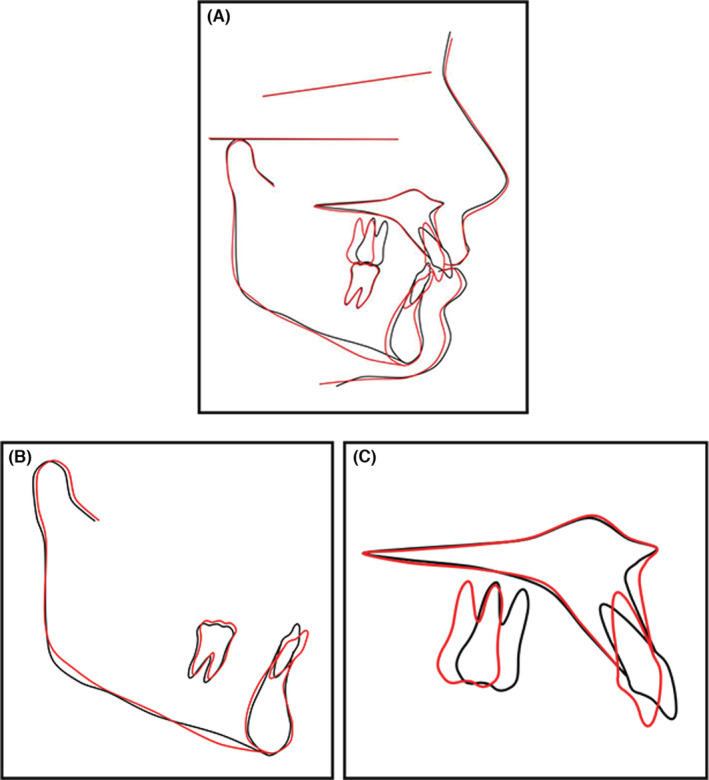

Overall treatment time was <1 year of active treatment. After 10 months of treatment, the treatment objectives had been successfully fulfilled. The treatment was completed in one phase with no additional refinement required. Forty‐four aligners were used as planned by the ClinCheck, where 24 aligners were used for upper molar distalization and the other 20 aligners were used for incisor retraction and finishing. The patient was compliant in wearing the aligners every day for 22 h per day and she reported wearing times per day in a compliance chart that was given to her. Post‐treatment records demonstrate satisfactory final results with all objectives achieved (Figure 4). Extraoral photos show an enhanced profile and improved lip competency. The smile of the patient was restored with optimal smile arc and decreased gum show. Intraoral examination reveals coincident upper and lower dental midlines, class I canines and molars bilaterally, adequate overjet and overbite, and ovoid well‐aligned upper and lower arches. Post‐treatment panoramic radiography showed good root parallelism, no signs of crestal bone height reduction, and no evidence of apical root resorption. Cephalometric and digital model superimpositions highlight the distalization of upper molars with no vertical movement and retraction of upper incisors. There was mild extrusion of the lower molars and proclination of the lower incisors due to the use of class II elastics, which helped reduce the overjet and attain incised contact (Figures 5 and 6). There were no adverse effects noticed or reported by the patient. The patient was very satisfied with the treatment result and reported enhanced smile esthetics, better profile and more comfort during closing teeth and chewing food. For retention, the patient had Vivera removable retainers, and follow‐up examination after 1 year of retention showed stable treatment results (Figure 7).

FIGURE 4.

End of treatment records: Extraoral photos, intraoral photos, panoramic radiograph, lateral cephalometric radiograph

FIGURE 5.

Superimposition of pre and post lateral cephalometric radiographs: (A) Overall superimposition on the anterior cranial base, (B) Superimposition of the mandible on the symphysis and lower border of the mandible, (C) Superimposition of the maxilla on the anterior contour of the zygomatic process

FIGURE 6.

Superimposition of pre‐ and post‐treatment digital models by the ClinCheck

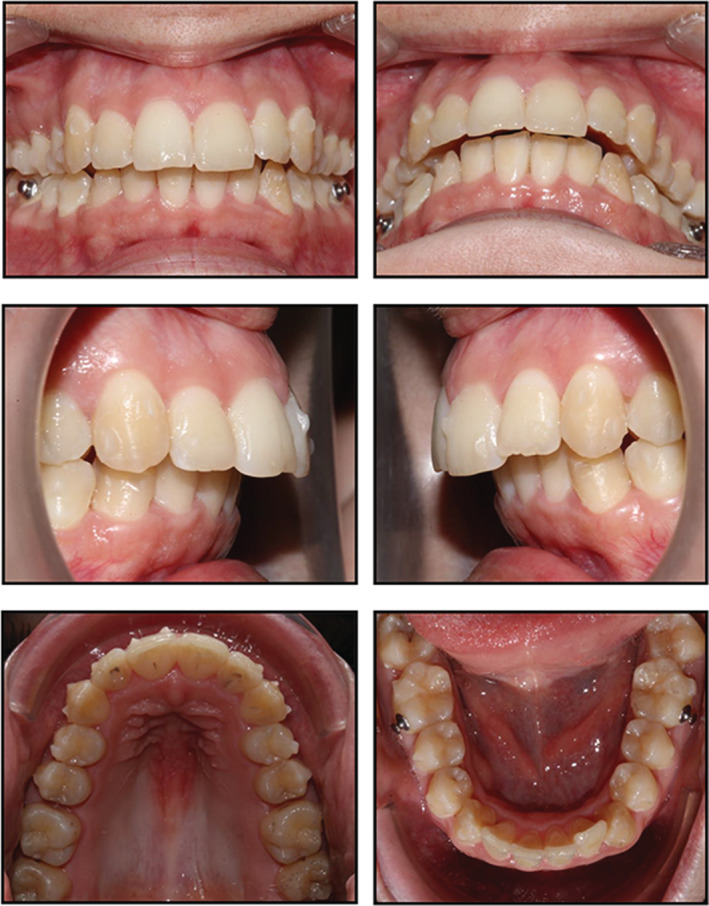

FIGURE 7.

Intraoral photos after 1 year of retention period

3. DISCUSSION

The aim of the present case report is to explain the management of a dental class II malocclusion case using CAT, where the patient was not willing to undergo fixed appliance therapy. CAT with intermaxillary elastics enabled the resolution of the malocclusion within a treatment time comparable with that required for conventional fixed appliance therapy, providing the patient with a comfortable, practical and esthetically pleasing appliance. There were controversies over whether moderate to difficult malocclusions can be successfully accomplished with CAT. 5 , 7

Different treatment modalities have been proposed in the literature to correct class II malocclusion including the use of clear aligners with mandibular advancement feature if the patient is growing. 9 In adult class II patients, clear aligners have been used to correct the class II malocclusion either alone 10 or in combination with auxiliaries, adjuncts either pre‐aligner therapy in the form of fixed functional appliances or concomitantly with aligners in the form of temporary skeletal anchorage devices placed either Buccally or Palatally. In some cases, extraction of some teeth might be necessary. 8 However, these alternative options involve more complex treatment with increased treatment time and additional expenses and require more patient compliance throughout treatment. Distalization of maxillary molars is frequently the treatment of choice required in class II nonextraction patients. Distalization achieved in this case was 2.5 mm with no observed vertical movement. These findings are in accordance with the mean reported distalization values by Ravera et al 18 on 20 nongrowing patients (2.52 mm) and Simon et al 19 on 30 adult patients (2.7 mm), who reported the highest accuracy for bodily distal movement of molars of 87%. The authors further emphasized the greater accuracy when the movement was supported by the presence of attachments. Our findings are also in accordance with Caruso et al's findings in a retrospective study to assess the upper molar distalization and its effect on the vertical dimension. They reported efficient upper molar bodily distalization of up to 3 mm with good vertical dimension control. This could be attributed to the aligner design that enables 3D movements by holding teeth on all surfaces including vestibular, palatal‐lingual, and also occlusal. 20

In the present case, attachments were planned on most teeth to guide their movement and control their axes, resulting in higher predictability of movements. Different attachment angulations and geometries were planned, where vertical attachments were placed on the premolars and molars to prevent tipping and allow for bodily distalization. The attachments were located on the mesial side of the upper molars to prevent any mesial rotation of molars. Additionally, paired vertical root control attachments on the canines bilaterally were placed to help achieve bodily movement and control their long axes during distalization. Horizontal attachments were also planned on upper incisors for extra retention and firmer grip of the aligner. On the contrary, Saif et al 3 stated that although distalization can be successfully attained in adult patients with a mean of 2.6 mm, significant anchorage loss occurs and the use of attachments has no enhancement effect on distalization. This was further elaborated by a systematic review in 2019 concluding that attachment incorporation is not necessary when molar distalization is planned. 13

Furthermore, Simon et al 19 highlighted the importance of staging in increasing the predictability of distalization. This was also observed in our case, where sequential distalization was planned on 24 stages of aligner treatment, hence achieving the highest predictability of distalization.

The increased overjet was corrected by a combination of upper molar distalization, upper incisor teeth retraction, and lower incisor proclination. This was facilitated by the use of class II elastics to augment the anchorage and aid in class II correction. However, short class II intermaxillary elastics were placed from upper premolars to lower molars, unlike the conventional attachment of long class II elastics from upper canines to lower molars. The reason behind that protocol was that in this case, it is desirable to avoid the vertical reciprocal forces from elastics to act on the upper anterior teeth causing extrusion and retroclination, leading to further bite deepening by the clockwise rotation of the upper anterior teeth. Also, the attachment of elastics on canines can lead to canine rotation requiring additional refinements to derotate them. Furthermore, by using short class II elastics, good control of maxillary incisor torque was achieved, with no loss of anchorage. Maxillary incisors are believed to be a starting point for facial esthetics with growing demands for facial esthetics. Three‐dimensional maxillary incisor position (MIP) plays a crucial role in enhancing facial esthetics during smile and rest positions. 21 Similarly, Caruso et al 9 demonstrated good control of upper incisor inclination with clear aligners in skeletal class II growing patients treated with aligners with mandibular advancement due to the biomechanical action of aligners that is achieved by the full coverage of the whole crown structure by aligners. Furthermore, Caruso et al 20 concluded that upper molar bodily distalization with clear aligners up to 3 mm can guarantee excellent control of incisal torque without taxing anchorage during the procedure.

In contrast to the overjet reduction achieved in the present case report, Patterson et al in 2020 observed on a sample of 80 adult patients, that no significant class II correction or overjet reduction was achieved with class II elastics for an average of 7 months using ABO model grading system. 22

Our strategy for the treatment of this patient was different from the strategy employed by Roberston and El‐Bialy 10 in the treatment of an adolescent patient presented with skeletal class II malocclusion with compensated occlusion. They divided their treatment into 2 phases where phase 1 involved the decompensation of the inclination of upper and lower incisors through the use of class III elastics followed by phase 2 to correct the dental class II relation and the use of class II elastics. This strategy of using initially class III elastics is beneficial if no sufficient overjet is present from the start and if the occlusion is compensated through retroclination of upper incisors and proclination of lower incisors. This was not the case in our patient as initially the patient presented with increased overjet and proclined upper incisors. At first, they used long class II elastics from upper canines to lower molars that might have had an effect on the retroclination of upper incisors that was noticed in the end of the treatment. Contrary, we used short class II elastics from the start to avoid any adverse effect on the upper incisors. Moreover, in their study, they had to do refinements to increase the palatal root torque of incisors and also to derotate the upper canines due to the use of long class II elastics from the canines to lower molars. This was overcomed in our patient by avoiding the canines in the attachment of class II elastics and by using correct attachment geometries on canines, premolars, and molars; hence, no additional refinements were needed in our patient. We bonded buttons to the lower molars for increased elastic strength, which allowed the dental changes necessary for this correction, similar to their study. Leveling the arches and intrusion of posterior teeth with a clear aligner allowed the vertical bite jump. This was incorporated into the digital treatment plan and allowed the mandible to autorotate forward, which also assisted in the class II correction.

The increased overbite is another challenge in this case. A few factors in this case allowed us to achieve the desired overbite correction. Achieving the desired inclination of the upper incisors was attained by prescribing these movements in the digital treatment plan and by intruding them using horizontal attachments. Also, extrusion of the upper incisors was prevented by the use of short class II elastics. Moreover, the distalization movement aided in the decrease of the bite depth that was achieved.

To quantify the amount of tooth movements in the present case, two methods of superimpositions were utilized, which were the ClinCheck software superimpositions and the 2D lateral cephalometric superimpositions.

In the present case report, the aligner change was performed every 2 weeks. Recently, Align Technology has indicated that weekly changes of aligners can be made. A study evaluating the effect of 7 days versus 14 days of aligner wear concluded that the 14‐day changes revealed greater accuracy in posterior movements. 23 Moreover, the tooth requires a period of adaptation for recovery to aid in stabilization and increase retention. 24

The whole treatment objectives were accomplished in one phase with no additional refinements in 10 months. This is considered to be a great advantage for CAT where it was proved to result in a significantly shorter treatment duration than with braces. 25 Patterson et al findings contradict our findings where they stated that additional refinements were necessary to address problems created during treatment. 22

4. CONCLUSIONS

Combined use of aligners with appropriate attachment location and geometry is an efficacious means of resolving more complex orthodontic issues such as class II malocclusions within a time frame comparable, if not less, to conventional fixed orthodontics but with excellent esthetics, oral hygiene and quality of life. Clinical tips to manage such cases include proper planning and ideal case selection for achieving the highest predictability of movements, efficient anchorage planning with the ideal selection of attachments locations and geometries, judicious use of short class II elastics, 14‐day aligner change and sequential distalization by optimizing staging prescriptions that are considered to be crucial in molar distalization in CAT.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Waddah Sabouni: Investigation; methodology; resources; software. M. Srirengalakshmi: Visualization; writing – original draft. Nikhilesh Vaid: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Samar M. Adel: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; writing – original draft.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funds were received for the conduction of the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was signed by the patient for the inclusion of her images for the purpose of publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Sabouni W, Muthuswamy Pandian S, Vaid NR, Adel SM. Distalization using efficient attachment protocol in clear aligner therapy—A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e06854. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.6854

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article in the form of table and figures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alhammadi MS, Halboub E, Fayed MS, Labib A, El‐Saaidi C. Global distribution of malocclusion traits: a systematic review. Dental Press J Orthod. 2018;23:40.e41‐40.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowman SJ, Celenza F, Sparaga J, Papadopoulos MA, Ojima K, Lin JC. Creative adjuncts for clear aligners, part 1: class II treatment. J Clin Orthod. 2015;49:83‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saif BS, Pan F, Mou Q, et al. Efficiency evaluation of maxillary molar distalization using Invisalign based on palatal rugae registration. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022;161:e372‐e379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Djeu G, Shelton C, Maganzini A. Outcome assessment of Invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment compared with the American Board of Orthodontics objective grading system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:292‐298. discussion 298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Phan X, Ling PH. Clinical limitations of Invisalign. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:263‐266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyd RL. Complex orthodontic treatment using a new protocol for the Invisalign appliance. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41:525‐547. quiz 523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boyd RL. Esthetic orthodontic treatment using the invisalign appliance for moderate to complex malocclusions. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:948‐967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaid NR, Sabouni W, Wilmes B, Bichu YM, Thakkar DP, Adel SM. Customized adjuncts with clear aligner therapy: "the Golden circle model" explained! J World Fed Orthod. 2022;11:216‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caruso S, Nota A, Caruso S, et al. Mandibular advancement with clear aligners in the treatment of skeletal class II. A retrospective controlled study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2021;22:26‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robertson LJ, El‐Bialy T. Non‐surgical treatment of a late adolescent patient with skeletal class II malocclusion using clear aligners: a case report. Open Dent J. 2022;16:1‐8. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lombardo L, Colonna A, Carlucci A, Oliverio T, Siciliani G. Class II subdivision correction with clear aligners using intermaxilary elastics. Prog Orthod. 2018;19:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dhanasekaran D, Mani D. Case report–an esthetic approach to treat class II subdivision malocclusion using clear aligners. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2021;8:3126‐3136. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galan‐Lopez L, Barcia‐Gonzalez J, Plasencia E. A systematic review of the accuracy and efficiency of dental movements with Invisalign®. Korean J Orthod. 2019;49:140‐149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiori A, Minervini G, Nucci L, d'Apuzzo F, Perillo L, Grassia V. Predictability of crowding resolution in clear aligner treatment. Prog Orthod. 2022;23:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flores‐Mir C, Brandelli J, Pacheco‐Pereira C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life status after 2 treatment modalities: Invisalign and conventional fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:639‐644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adel SM, Vaid NR, El‐Harouni N, Kassem H, Zaher AR. TIP, TORQUE & ROTATIONS: how accurately do digital superimposition software packages quantify tooth movement? Prog Orthod. 2022;23:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adel SM, Vaid NR, El‐Harouni N, Kassem H, Zaher AR. Digital model superimpositions: are different software algorithms equally accurate in quantifying linear tooth movements? BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ravera S, Castroflorio T, Garino F, Daher S, Cugliari G, Deregibus A. Maxillary molar distalization with aligners in adult patients: a multicenter retrospective study. Prog Orthod. 2016;17:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique – regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caruso S, Nota A, Ehsani S, Maddalone E, Ojima K, Tecco S. Impact of molar teeth distalization with clear aligners on occlusal vertical dimension: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heo S, Park JH, Lee M‐Y, Kim J‐S, Jung SP, Chae J‐M. Maxillary Incisor Position‐Based Orthodontic Treatment with Miniscrews, Seminars in Orthodontics. Elsevier; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patterson BD, Foley PF, Ueno H, Mason SA, Schneider PP, Kim KB. Class II malocclusion correction with Invisalign: is it possible? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021;159:e41‐e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al‐Nadawi M, Kravitz ND, Hansa I, Makki L, Ferguson DJ, Vaid NR. Effect of clear aligner wear protocol on the efficacy of tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:157‐163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chisari JR, McGorray SP, Nair M, Wheeler TT. Variables affecting orthodontic tooth movement with clear aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145:S82‐S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ke Y, Zhu Y, Zhu M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article in the form of table and figures.