Abstract

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the primary treatment for malaria. It is essential to characterize the pharmacokinetics (PKs) and pharmacodynamics (PDs) of ACTs in vulnerable populations at risk of suboptimal dosing. We developed a population PK/PD model using data from our previous study of artemether-lumefantrine in HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected children living in a high-transmission region of Uganda. HIV-infected children were on efavirenz-, nevirapine-, or lopinavir-ritonavir-based antiretroviral regimens, with daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis. We assessed selection for resistance in two key parasite transporters, pfcrt and pfmdr1, over 42-day follow-up and incorporated genotyping into a time-to-event model to ascertain how resistance genotype in relation to drug exposure impacts recurrence risk. Two hundred seventy-seven children contributed 364 episodes to the model (186 HIV-uninfected and 178 HIV-infected), with recurrent microscopy-detectable parasitemia detected in 176 episodes by day 42. The final model was a two-compartment model with first-order absorption and an estimated age effect on bioavailability. Systemic lumefantrine exposure was highest with lopinavir-ritonavir, lowest with efavirenz, and equivalent with nevirapine and HIV-uninfected children. HIV status and lumefantrine concentration were significant factors associated with recurrence risk. Significant selection was demonstrated for pfmdr1 N86 and pfcrt K76 in recurrent infections, with no evidence of selection for pfmdr1 Y184F. Less sensitive parasites were able to tolerate lumefantrine concentrations ~ 3.5-fold higher than more sensitive parasites. This is the first population PK model of lumefantrine in HIV-infected children and demonstrates selection for reduced lumefantrine susceptibility, a concern as we confront the threat to ACTs posed by emerging artemisinin resistance in Africa.

Malaria remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with over 241 million cases in 2020.1 Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are a highly effective first-line treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. The short-acting artemisinin backbone rapidly reduces parasite burden while the longer-acting partner drug eliminates residual parasites, provides a duration of post-treatment prophylaxis, and protects against artemisinin resistance. Of the six World Health Organization (WHO) recommended ACTs, artemether-lumefantrine (AL) is the most widely used.2

Whereas ensuring efficacy and limiting toxicity are primarily therapeutic aims, low PK exposure can increase the risk of drug resistance emergence, and, once present, may fuel its spread.3 Artemisinin resistance-associated Pfkelch13 mutations are widespread in Southeast Asia, and are now present in Rwanda and Uganda.4,5 Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and copy number variations in two key transporter genes, Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (pfcrt) and Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance 1 (pfmdr1), impact parasite susceptibility to many partner drugs including the two most widely used ACTs in SSA, AL, and artesunate-amodiaquine.6–8 Interestingly, lumefantrine and amodiaquine exert opposing selection: parasites with pfmdr1 86Y, Y184, and pfcrt 76 T alleles exhibit reduced amodiaquine susceptibility, whereas pfmdr1 N86, 184F, D1246, and pfcrt K76 alleles confer reduced lumefantrine susceptibility.6–12 Artemisinins may also exert selective pressure at pfmdr1.10,13–15

AL has remained the ACT least impacted by the emergence and spread of artemisinin resistance, but efficacy concerns are being raised in a handful of SSA countries.15,16 Following rapid artemisinin clearance, partner drugs persist as a monotherapy for weeks to months. In high transmission settings, newly emerging blood-stage parasites encounter subtherapeutic partner drug levels, which may be a potent force for resistance selection. Modeling suggests that initial partner drug resistance will facilitate the emergence of artemisinin resistance.16

Optimizing malaria treatment in children also requires consideration of multiple factors impacting pharmacokinetics (PKs) and pharmacodynamics (PDs). We and others have demonstrated that young children show reduced exposure to both piperaquine and lumefantrine compared with adults, findings that have impacted treatment guidelines.17– 24 HIV-malaria co-infection is a concern in SSA, where over 2.4 million children were infected with HIV in 2018 alone. In this setting, the use of daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (T-S), an antifolate combination with anti-Plasmodial activity, has been a key measure to reduce the risk of malaria and other infections in those with HIV.25– 27 However, drug– drug interactions (DDIs) are an important consideration in optimizing treatment. For AL, artemether is metabolized to dihydroartemisinin by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 2B6, with both the parent and metabolite exhibiting antimalarial activity, whereas lumefantrine is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4.28 Antiretrovirals impact these pathways; efavirenz (EFV) and nevirapine (NVP) exhibit varying levels of CYP3A4 induction, whereas lopinavir-ritonavir (LPV/r) is a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor.29 Our previous studies have shown that antiretroviral choice significantly impacts AL PKs.19,29 Using noncompartmental PK analysis, LPV/r-based regimens significantly increased AL exposure and EFV significantly decreased exposure compared to HIV-uninfected children. In contrast, NVP provided equivalent lumefantrine exposure, suggesting a lack of a DDI. PK exposure was in turn associated with efficacy.29

We now extend this analysis by conducting the first population PK model of AL-antiretroviral DDIs in children, and, most importantly, present the first population PK/PD analysis of lumefantrine PKs and resistance selection. We hypothesized that the wide range of lumefantrine exposure in our high transmission setting, due to the presence of significant DDIs, would allow us to ascertain mutational selection in recurrent malaria episodes, and the relationship of those mutations to long-acting residual lumefantrine concentrations.

METHODS

Study design and PK analysis

Details of the parent study and noncompartmental PK analysis have been published previously.29 Briefly, we conducted a prospective PK/ PD trial of AL in the context of HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected children on daily T-S prophylaxis and EFV-, NVP-, or LPV/r-based antiretroviral therapy (ART), ages 0.5–8 years, presenting with uncomplicated P. falciparum infection in high-transmission Tororo, Uganda in 2011– 2014. All children were treated with a six-dose standard weight-based AL (Coartem Dispersible 20 mg/120 mg; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) with milk or breastfeeding. Both intensive and sparse PK sampling were conducted, and our primary outcome was recurrent parasitemia over 42-day follow-up (Supplement Data S1). For the intensive PK cohort, sampling was pre–first dose (day 0) and pre/post– sixth dose (7 venous samples on day 3 at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 hours post– last dose), and days 4, 7, 14, and 21 (capillary). For the sparse PK cohort, only capillary sampling on days 7, 14, and 21 was performed. Concentrations of lumefantrine were determined using liquid chromatography– tandem mass spectrometry, as previously described, with a lower limit of quantification of 50 ng/mL.30 Treatment outcome for this analysis was based on recurrent parasitemia over 42 days, with genotyping of recurrent episodes conducted using capillary electrophoresis at 6 polymorphic markers.2,31 Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was determined using the total number of unique msp2 fragment lengths for each sample. All study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation or with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and received institutional review board approval (IRB) at Yale University, the University of California – San Francisco, and both local and regional Uganda IRB approval.

Drug resistance genotyping

Drug resistance genotyping for pfmdr1 N86Y or Y184F or pfcrt K76T was performed using nested polymerase chain reaction followed by ligase detection reaction (Supplement Data S1 and Supplementary Table S1).32,33 Established P. falciparum strains were used as positive controls for each polymorphism (MR4; BEI Resources, Manassas, VA). Genotype status at drug resistance loci was compared in pretreatment and recurrent samples for all children with recurrent parasitemia over the 42-day follow-up. Due to multiclonal infections, infections were grouped as wild-type, mutant, or mixed genotype. Changes in pre-/post-genotype for each locus were compared by McNemer’s test.

Population PK model for lumefantrine

A population PK model for lumefantrine was developed using nonlinear mixed effects modeling with a qualified installation of NONMEM, version 7.4 or greater (ICON PLC, Ireland). Population and individual model parameters were estimated using the stochastic approximation expectation maximization (SAEM) method followed by Monte Carlo importance sampling. Data assembly and all other pre-or post-processing was conducted in R version 4.0 (http://www.r-project.org ). Model fit was assessed with standard goodness of fit diagnostics to ensure the adequacy of the fit. Simulation-based model visual predictive checks were generated to evaluate the PK model’s ability to predict the observed data.

Population PK/PD time to event modeling

To evaluate the association of PK exposure with drug resistance, drug exposure response models were developed using time-to-event (TTE) analyses with new infections captured as independent events. The parametric TTE model allowed us to assess the relationship between recurrent infection and lumefantrine exposure and to explore the effect of prognostic factors (covariates) on re-infection. The exposure metric was the concentration of lumefantrine at the time of event (microscopically detectable recurrent parasitemia) or lumefantrine concentration when events were censored at 42 days post-lumefantrine dose. Two types of TTE models were developed. The first included all patients with a malaria infection and compared hazards in children with and without HIV (and hence with and without ART). The second TTE models included only patients with microscopically detectable recurrent infection (either recrudescent or new infection) within the 42-day follow-up period for which genotyping information was available. Children were allowed to re-enroll for repeat clinical episodes, either occurring during the 42-day follow-up or at any point until study completion (when sample sizes were reached). The magnitude and precision of the covariate effects relative to reference values were presented using forest plots with the generated parameters from the bootstrap runs. Additional details on the TTE models are in the Supplement Data S1.

RESULTS

Study profile

Full study details have been published previously and details of the study profile are in the Supplement Data S1.29 For the population PK analysis, 277 children with 364 malaria episodes were included, and for the population PK/PD analysis by treatment arm, 274 children with 358 malaria episodes were included. In our high transmission setting, recurrent infection was common. The population PK/PD analysis by drug resistance genotype included 176 children with recurrent infections, 12 (6.8%) of which were recrudescent. The mean MOI was 3.1 (median = 2, range 1–18). Table 1 describes study cohort demographics and outcomes for the population PK cohort, and Supplementary Table S2 describes the subpopulation PK/PD cohort included in the drug resistance analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and study outcomes for population PK cohort

| HIV-infected children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Parameter | HIV-uninfected children | EFV-based ART | LPV/r-based ART | NVP-based ART |

|

| ||||

| Malaria episodes, n | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall | 186 | 48 | 68 | 62 |

|

| ||||

| Per child | ||||

|

| ||||

| 1 | 159 | 25 | 41 | 37 |

|

| ||||

| 2 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 13 |

|

| ||||

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

|

| ||||

| 5+ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

|

| ||||

| Malaria episodes per child, median (range) | 1 (1– 5) | 1 (1– 5) | 1 (1– 8) | 1 (1– 6) |

|

| ||||

| % Episodes in male children | 53.2 | 33.3 | 35.3 | 53.2 |

|

| ||||

| Weight, kg, median (range) | 14.1 (9.80– 27.0) | 18.0 (11.4– 25.1) | 15.4 (7.65– 23.7) | 16.0 (8.50– 30.0) |

|

| ||||

| Age, years, median (range) | 3.58 (0.16– 7.91) | 6.00 (3.17– 8.58) | 4.50 (1.58– 7.83) | 4.50 (1.33– 8.00) |

|

| ||||

| Parasite density, geometric mean, parasites/μL (95% CI) | 16,368 (12,166/22,021) | 11,291 (6,098.5/20,906) | 6392.8 (3,523.4/11,599) | 10,568 (5,746.7/19,436) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; EFV, efavirenz; LPV/r, lopinavir-ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine; PK, pharmacokinetic.

Population pharmacokinetics of lumefantrine in the setting of concomitant antiretroviral therapy

A two-compartment population PK model with first-order absorption provided the best and most parsimonious fit to the data. The final model included fixed effects of body weight on all clearance and volume terms. Fixed effects on volume used an allometric exponent of 1, whereas the fixed effects on clearance used an exponent of 0.75, 0.9, 1.0, or 1.2 for children age > 60 months, > 24 to 60 months, > 3 to 24 months, and ≤ 3 months, respectively.34 The model also estimated the effect of age on bioavailability and the effect of ART (i.e., EFV, LPV/r, or NVP) on lumefantrine apparent clearance (CL/F) and the first-order absorption rate constant (KA).

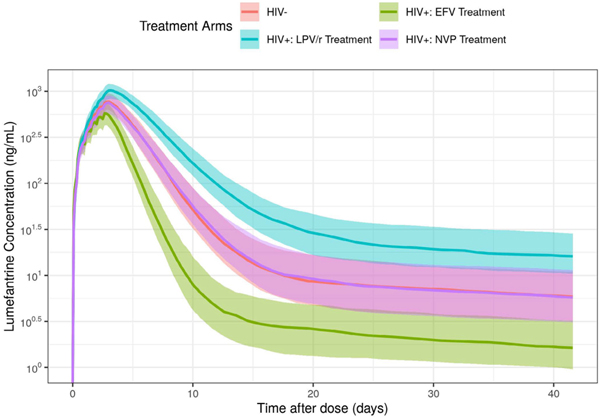

The final model provided a reasonable description of the data, as judged by visual inspection of model diagnostic plots (Supplementary Figures S1–S4). Parameter estimates and asymptotic 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for a reference patient (i.e., a 50-month-old HIV-uninfected child weighing 15 kg (approximate median age and weight of this cohort)), are shown in Table 2. The estimated exponent of the age effect on bioavailability was 0.204 (−0.0586, 0.467: median (95% CIs)) suggesting younger children had reduced lumefantrine bioavailability; however, more data are needed to accurately estimate this effect. Patients receiving EFV had CL/F and KA estimates ~ 198.2% and 148% those estimated in HIV-uninfected patients, respectively (Table 2). This increase in lumefantrine CL/F and KA resulted in an overall decrease in lumefantrine exposure (in terms of area under the curve (AUC)) for HIV-infected children treated with EFV compared to HIV-uninfected children (Figure 1, green vs. red line; Supplementary Table S3). Patients receiving LPV/r had CL/F and KA estimates ~ 48.6% and 78.8% that of HIV-uninfected patients, respectively (Table 2). This decrease in lumefantrine CL/F and KA resulted in an overall increase in lumefantrine exposure for HIV-infected children treated with LPV/r compared to HIV-uninfected children (Figure 1, blue vs. red line). As compared to HIV-uninfected children, there was no statistically significant effect of NVP treatment on lumefantrine CL/F and KA (Table 2; Figure 1, purple vs. red line). The full range of lumefantrine exposure for children with and without HIV and by ART regimen is reflected in the day 0– 42 AUC (Supplementary Table S3). Accordingly, the PK model consistently predicted the observed lumefantrine profiles in pediatric patients, with and without ART (Figure 1, Figure S1).

Table 2.

Summary of population PK fixed and random effects parameter estimates

| Estimate | 95% CI | Shrinkage (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural model parameters | |||||

| CL/F (L/h) | θ 1 | Apparent clearance | 1.20 | 0.952, 1.45 | - |

| V2/F (L) | θ 2 | Apparent central volume of distribution | 24.1 | 19.0, 29.2 | - |

| Q/F (L/h) | θ 3 | Apparent intercompartmental clearance | 0.380 | 0.258, 0.501 | - |

| V3/F (L) | θ 4 | Apparent peripheral volume of distribution | 767 | 174, 1.36 e+03 | - |

| KA (1/h) | θ 5 | Absorption rate constant | 0.0215 | 0.0197, 0.0234 | - |

| Covariate effect parameters | |||||

| AGEF | θ 6 | Age effect on bioavailability (F) | 0.204 | −0.0586, 0.467 | - |

| EFVCL/F | θ 7 | EFV effect on CL/F | 0.982 | 0.163, 1.80 | - |

| LPV/rCL/F | θ 8 | LPV/r effect on CL/F | −0.514 | −0.696, −0.332 | - |

| NVPCL/F | θ 9 | NVP effect on CL/F | 0.0191 | −0.324, 0.362 | - |

| EFVKA | θ 10 | EFV effect on KA | 0.484 | 0.282, 0.685 | - |

| LPV/rKA | θ 11 | LPV/r effect on KA | −0.212 | −0.305, −0.120 | - |

| NVPKA | θ 12 | NVP effect on KA | −0.0589 | −0.207, 0.0891 | - |

| Interindividual variance parameters | |||||

| IIV-CL/F | Ω(1,1) | Variance of CL/F | 0.735 [CV% = 104] | 0.526, 0.945 | 5.86 |

| IIV-V2/F | Ω(2,2) | Variance of V2/F | 0.813 [CV% = 112] | 0.504, 1.12 | 32.6 |

| IIV-Q/F | Ω(3,3) | Variance of Q/F | 0.0250 [CV% = 15.9] | FIXED | 67.5 |

| IIV-V3/F | Ω(4,4) | Variance of V3/F | 0.956 [CV% = 127] | 0.590, 1.32 | 36.4 |

| IIV-KA | Ω(5,5) | Variance of KA | 0.0280 [CV% = 16.9] | 0.00705, 0.0490 | 58.2 |

| Residual variance | |||||

| Proportional | Σ(1,1) | Variance | 0.200 [CV% = 44.7] | 0.173, 0.226 | - |

Structural model parameters were estimated for a reference subject (i.e., a 50-month-old HIV-uninfected child).

CI, confidence intervals; CV%, percent coefficient of variation; EFV, efavirenz; IIV, interindividual variability; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine; PK, pharmacokinetic; SE, standard error.

Confidence intervals = estimate ± 1.96 * SE, CV% of omegas = sqrt(exp(estimate) − 1) * 100, CV% of sigma = sqrt(estimate) * 100.

Figure 1.

Simulated lumefantrine concentration over time for patients with and without ART. The lines represent the median predicted lumefantrine concentration and the shaded regions represent the 30% prediction interval (i.e., from the 35th to 65th percentiles) of the median. ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz.

Lumefantrine concentration and risk of recurrence by treatment arm

Model development started with a simple time-independent constant hazard and then progressed to more complex functions with time-dependent hazard, including Weibull, and log-normal distributions. A log-normal hazard function provided the best fit to the data. The parameters characterizing the log-normal hazard distribution were μ and σ, the mean and SD of a log normal distribution, were as follows:

where Φ is the standard normal cumulative distribution function, Φ − 1 is the inverse cumulative normal distribution function. The final model included all malaria episodes and recurrent infections, and final parameters are presented in Table 3. The model suggests those with HIV on ART and T-S were 48.6% (95% CI 33.4 – 63.7%) less likely to have recurrent microscopically-detectable parasitemia than HIV-uninfected children. The effect of lumefantrine concentration on the hazard was incorporated as an exponential and so 182 ng/mL (95% CI 29.8–3 35 ng/mL) represents the approximate lumefantrine concentration that decreases the risk of infection by half (C50) on a log-scale.

Table 3.

Summary of TTE model parameters for risk of recurrence by treatment arm or by K76T genotypes

| Estimate | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model: Risk of recurrence by treatment arm | |||

| θ 1 | Mean of log-normal hazard distribution | 0.683 | 0.566, 0.799 |

| θ 2 | SD of log-normal hazard distribution | 3.96 | 3.81, 4.10 |

| θ3 | HIV on hazard function | −0.514 | −0.666, −0.363 |

| θ4 | C50 lumefantrine concentration (ng/mL) on hazard function | 182 | 29.8, 335 |

| Model: Risk of recurrence with different K76T genotypes | |||

| θ1 | Mean of log-normal hazard distribution | 0.428 | 0.312, 0.544 |

| θ2 | SD of log-normal hazard distribution | 3.45 | 3.34, 3.55 |

| θ3 | C50 lumefantrine concentration (ng/mL) on hazard function | 128 | 20.4, 235 |

| θ4 | K76T mutation on C50 | 0.284 | −0.0692, 0.637 |

CI, confidence intervals; C50, concentration of lumefantrine that reduced the risk of recurrence by half on a log-scale; TTE, time-to-event.

Confidence intervals = estimate ± 1.96 * SE.

For both time to event models, theta 1 and 2 were structural model parameters and theta 3 and 4 were covariate effects.

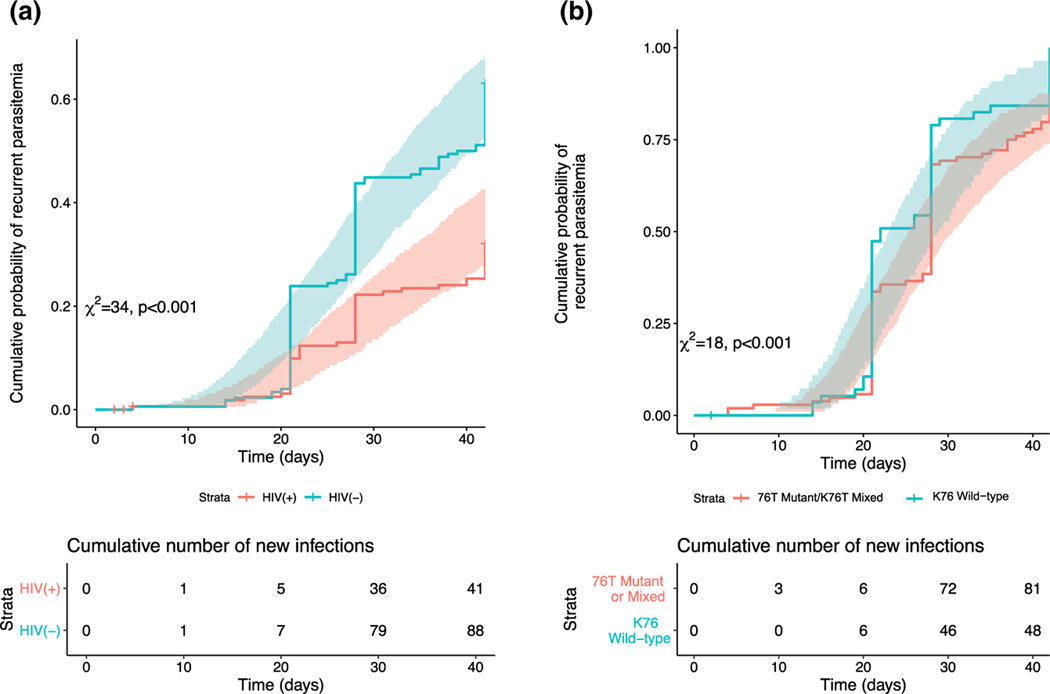

Overall, the model identified two significant risk factors (covariates) associated with the probability of acquiring a new malaria infection: HIV status (HIV-infected and receiving T-S ) and lumefantrine concentration at the time of an event. The cumulative probability of a malaria infection was higher in HIV-uninfected children compared to HIV-infected children on ART and T-S (Figure 2a). The model could not identify a significant independent ART treatment effect, likely because the lumefantrine concentration inherently includes the effect of ART treatment through changes to the population PK model parameters and subsequent increased/decreased lumefantrine exposure. Given the longitudinal analysis, a continuous covariate (i.e., lumefantrine concentration) was preferable to a categorical covariate (i.e., ART treatment group) that lost important information.

Figure 2.

The cumulative probability of malaria over time in patients by (a, left) HIV status or by (b, right) pfcrt K76T genotype. The lines indicate the median hazard and the shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval (CI).

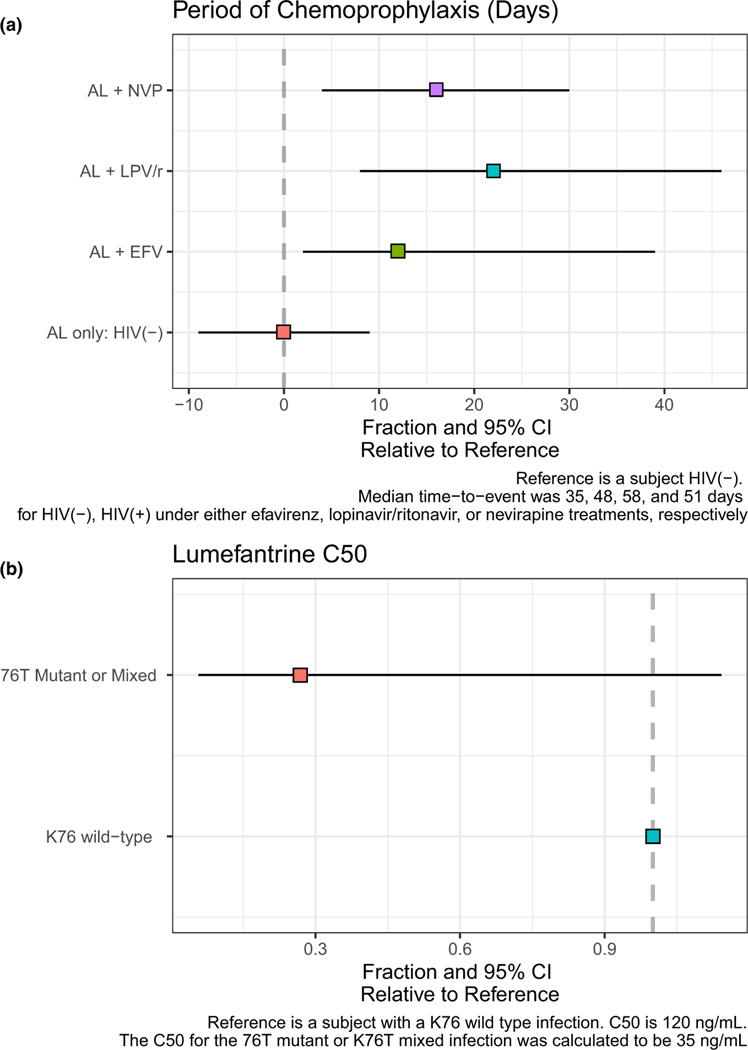

We next modeled the period of post-treatment chemoprophylaxis (PoC), defined as the period in which drug concentrations were sufficiently high to prevent new infections from becoming microscopically detectable (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S4). In our cohort, HIV-uninfected children typically remained malaria-free (below microscopic detection) for ~ 35 days following AL (Figure 3a). The PoC increased to ~ 48, 51, and 58 days for those receiving T-S and EFV, NPV or LPV/r, respectively (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

The PoC in patients by HIV infection status and antiretroviral regimen or lumefantrine C50 by pfcrt K76T genotype. (a, top panel) PoC in patients with and without HIV by antiretroviral regimen using the first TTE model. The reference subject was an HIV-uninfected patient with a median time-to-event (i.e., time to a malaria episode) of 35 days following treatment with AL. The relative difference in the PoC, compared to the reference subject, was determined for patients receiving AL plus EFV, LVP/r, or NVP, in addition to T-S chemoprophylaxis. The median and 95% CI of the relative difference are indicated by the box and whiskers, respectively. (b, bottom panel) Lumefantrine C50 in patients by re-infecting K76T genotype using the second TTE model. The reference subject had a K76 wild-type infection with a median lumefantrine C50 of 120 ng/mL. The relative difference in the lumefantrine C50, compared to the reference subject, was determined for infections with a mixed K76T or mutant 76T infection. The median and 95% CI of the relative difference are indicated by the box and whiskers, respectively. AL, artemether-lumefantrine; CI, confidence interval; EFV, efavirenz; LPV/r, lopinavir-ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine; PoC, post-treatment chemoprophylaxis; T-S, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TTE, time-to-event.

Selection for drug resistance in recurrent infections and in relation to lumefantrine concentration

Drug resistance SNP typing was successful for 170, 176, and 161 paired day 0 and day of failure samples for pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, and pfcrt K76T, respectively. Significant selection was demonstrated for pfmdr1 N86 and pfcrt K76 in recurrent infections, whereas no evidence of selection was seen for pfmdr1 Y184F (Table 4). For children with recurrent infections, the association of lumefantrine exposure and selection of less susceptible parasites was explored with a second TTE model including only children with recurrent infection during follow-up. A log-normal hazard function provided the best fit to the data. The final model for the pfcrt K76T genotype incorporated the concentration of lumefantrine on the hazard using a maximum effect (Emax) or saturable form, and mutation status effect was included on the lumefantrine C50 (i.e., the concentration of lumefantrine that reduced the risk of recurrence by half) parameter (Table 3). The effect of lumefantrine concentration on the hazard was incorporated as an exponential with 128 ng/ mL (95% CI 20.4– 235 ng/mL) representing the approximate lumefantrine concentration that decreased the risk of recurrent parasitemia by half on the log scale. The effect of the K76T mutation on the C50 suggests that wild-type parasites (i.e., less lumefantrine-sensitive parasites) were able to survive lumefantrine concentrations ~ 71.6% higher than parasites with mixed K76T or mutant 76T (Table 3). However, the 95% CIs show the large uncertainty of this estimate.

Table 4.

Genotype selections from day 0 to day of failure

| Selection | Frequency | Percent | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N86Y, n = 170 | |||

| Change to WT | 33 | 19.41 | 0.004 |

| Change to mutant | 12 | 7.06 | |

| No change | 125 | 73.53 | |

| Y184F, n = 176 | |||

| Change to WT | 43 | 24.43 | 0.59 |

| Change to mutant | 48 | 27.27 | |

| No change | 85 | 48.30 | |

| K76T, n = 161 | |||

| Change to WT | 70 | 43.48 | < 0.001 |

| Change to mutant | 33 | 20.50 | |

| No change | 58 | 36.02 |

The p value represents multinomial comparison of change to WT vs. change to mutant.

WT, wild-type.

The cumulative probability of malaria with parasites less susceptible to lumefantrine (i.e., pfcrt K76 = wild-type) was higher than the cumulative probability of re-infection with more sensitive parasites (i.e., pfcrt K76T = mutant or mixed; Figure 2b). Although this did not translate to a difference in the PoC, there was a clear difference in the C50 (Figure 3b, Supplementary Table S4). Less susceptible parasites were able to tolerate higher concentrations of lumefantrine than sensitive parasites, with median C50 values of 120 and 35 ng/mL, respectively (Figure 3b, Supplementary Table S4).

Although pfmdr1 N86 mutations associated with reduced susceptibility to lumefantrine were more prevalent in recurrent infections (P = 0.004; Table 4), the TTE analysis looked only at recurrent genotypes and in this dataset pfmdr1 N86 was almost at fixation in recurrent infections, thus the TTE analysis for this locus would not be informative. A TTE model was developed for pfmdr1 Y184F but was unable to determine any effect of lumefantrine concentration on the hazard or an effect of the pfmdr1 Y184F mutation (mutant or mixed vs. wild-type) on the lumefantrine C50. More than half of recurrent infections were mixed (n = 102, 58%) with the remaining recurrent infections split between the mutant and wild-type genotypes (n = 37 (20.0%) and n = 34 (19.3%), respectively). The analysis in Table 4 also found no evidence of selection for pfmdr1 Y184F.

DISCUSSION

We present a population-based PK model of lumefantrine in the context of the three most widely used HIV-antiretroviral regimens in children over the past 10– 15 years, bolstered by the inclusion of HIV-uninfected children. We further integrated clinical and parasitological drug resistance data to develop the first population-based PK/PD model to estimate the duration of post-treatment prophylaxis and recurrence risk based on partner drug exposure and resistance status in a high endemic setting in Uganda. Our data demonstrate the impact of key DDIs on lumefantrine exposure, the resulting period of post-treatment prophylaxis, and the impact of age on bioavailability. Most notably, recurrent parasites detected within 42 days of follow-up were more likely to harbor mutations that conferred lower susceptibility to lumefantrine, and more resistant parasites (wild-type pfcrt K76) were able to withstand higher lumefantrine concentrations than sensitive parasites.

Optimizing malaria treatment requires navigating a complex balance between achieving cure while limiting toxicity and the risk of resistance. Our PK model is in line with previous AL models that suggest a two-compartment model with first-order absorption best fit the data.17,19 Moreover, our data strongly support earlier findings that bioavailability is significantly reduced in young children. We found relative bioavailability reduced by ~ 45% for 6-month-old children, and 15% for 2-year-old children, compared with 5-year-old children, again raising the question of whether dosing modifications should be considered in the youngest age or weight groups.17,19,35,36 The reasons for the reduced bioavailability are unclear, but may be related to immaturity of the biliary or gastrointestinal tract. Lumefantrine is highly lipophilic and may display reduced solubility and permeability as intraluminal bile salts and protein binding is decreased. We also generated the first population PK model of pediatric HIV-malaria co-infection, taking advantage of the opposing inhibitory and induction potential of key antiretrovirals on CYP3A4. Our model demonstrates that EFV-based regimens are associated with dramatically lower exposure to lumefantrine, whereas LPV/r, a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor, is associated with significantly elevated lumefantrine exposure; differences that impact recurrence risk.29,37– 41 A previous individual patient data population PK meta-analysis in adults demonstrated similar impacts of EFV-, NVP-, and LPV/r-based ART on lumefantrine exposure.40 Importantly, whereas the widespread rollout of dolutegravir (DTG)-based regimens is underway in SSA, EFV-, NVP-, and LPV/r-based regimens remain widely used. A recent market report estimated that DTG accounted for 18% of pediatric use of generic antiretroviral regimens in low and middle income countries in 2020, whereas LPV/r, EFV, and NVP accounted for 53%, 19%, and 10%, respectively.42

With the inclusion of HIV-uninfected children in our study, we were also able to demonstrate that HIV-infected children on ART were at a lower risk of re-infection, regardless of the particular antiretroviral regimen, as compared to HIV-uninfected children. Indeed, the PoC following AL was 12 days longer in those on EFV than in HIV-uninfected children despite exhibiting significantly reduced lumefantrine exposure. We explain these results by the known protective effect of T-S, which 96% of our HIV-infected children were receiving.26,43 The WHO currently recommends that T-S be continued in HIV-infected individuals regardless of CD4 cell count in areas where malaria is prevalent, and recent data support its continued benefit in adults who are immune reconstituted on ART in an African malaria-endemic setting.27,44 Our interpretation is supported through a comparison of lumefantrine exposure in HIV-uninfected children (not on T-S) with exposure in HIV-infected children on NVP + T-S. Despite equivalent lumefantrine exposure in this group, the PoC in those on NVP + T-S was 16 days longer than in HIV-uninfected children. Although the increased age of our HIV-infected cohort (median age 4.5 years in children on NVP vs. 3.6 years in HIV-uninfected children; Table 1) may partially explain this finding, we suggest that the effect of T-S is likely the main driver of protection.45 These data further support the continued utility of T-S prophylaxis in HIV-infected children, despite increasing levels of antifolate resistance in Africa.46

The major objective of our study was to characterize the relationship between lumefantrine exposure and selection of molecular markers associated with partner drug resistance, leveraging the tremendous range of lumefantrine concentrations present in our study (lumefantrine AUC (0– 42 days) ranged from 65,644 to 9,430,142 ng·hr/mL), likely a larger variance than any clinical study published to date. Numerous studies have demonstrated that two key parasite transporters, pfmdr1 and pfcrt, can impact susceptibility to antimalarials.7,8,47 In particular, wild-type alleles at pfmdr1 N86Y and pfcrt K76T have been most consistently associated with reduced susceptibility to lumefantrine, with less compelling data for a role of pfmdr1 Y184F in susceptibility.8 We are aware of only two studies which have assessed the association of lumefantrine PK exposure and resistance selection, and both measured lumefantrine levels only at a single time point.9,11 The first involved two studies conducted in Tanzania with blood samples taken on filter paper at a single day 7 timepoint, and the use of an equation to estimate the concentration of lumefantrine at the time of hepatocyte rupture.11 In that study, re-infecting parasites with the pfmdr1 N86/184F/ D1246 haplotype (more resistant) were able to withstand lumefantrine blood concentrations 15-f old higher than those with the more sensitive 86Y/Y184/1246Y haplotype. The second study, conducted in Liberia, also obtained drug levels on day 7, and found that pfcrt K76 and pfmdr1 NFD haplotypes were selected for after AL treatment, with those carrying pfmdr1 N86 able to re-infect at higher lumefantrine concentrations than parasites carrying pfmdr1 86Y.9

Our data are in line with the above findings. Most notably, we find striking evidence of selection for parasites that harbor less sensitive alleles at the time of re-infection, namely a 2.74-fold and 2.12-fold higher rate of wild-type alleles for pfmdr1 N86Y and pfcrt K76T, respectively, at re-infection compared with baseline. Again, in line with prior literature, significant selection was not observed at pfmdr1 Y184F. We extend previous studies by applying the first population PK/PD model to assess partner drug resistance selection in relation to lumefantrine concentration. We find that the cumulative probability of recurrent malaria with wild-type pfcrt K76 was higher than for mixed/mutant genotypes such that the concentration required to reduce the risk of recurrence by 50% was 3.5-fold higher for more resistant parasites than for more sensitive mixed/mutant parasites. Due to the high prevalence of wild-type pfmdr1 N86 alleles at the time of re-infection (90.1%), similar population PK/PD analyses could not be performed for this locus. However, our results, taken in context of previous literature, provide evidence that can help to explain the dramatic increase in wild-type alleles at these 2 loci seen over the past ~15 years since the introduction and widespread use of ACTs, particularly AL, across SSA.48,49

Our work is subject to several limitations. Most notably our TTE model is limited to 42 days of follow-up, and not all children re-enrolled in the study for future episodes. Thus, we treated each event as independent, and were unable to comment on outcomes in those without recurrence by 42 days. In addition, our recurrent parasitemia event was based on microscopic detection of parasites, which is much less sensitive than molecular methods for the detection of low levels of emerging parasites, as lumefantrine levels wane over time. Similarly, we are unable to comment on parasite dynamics occurring between the period of liver emergence and microscopic detection, data that would provide higher resolution on the relationship of drug exposure and resistance selection. For instance, we did not find a difference in the PoC between less sensitive and more sensitive parasites, which could be due to relying on the microscopic detection of malaria rather than when parasites emerged from the liver.50 This is supported by a meta-analysis that found an increased PoC after AL treatment in areas with a high prevalence of pfmdr1 86Y and pfcrt 76T when using polymerase chain reaction-detected recurrence.51 Further, this TTE analysis assumed the visit time of observed recurrent parasitemia was equivalent to the time of the occurrence instead of considering that the event occurred at some point prior to the visit; however, results did not differ significantly when using an interval-censored approach (Supplement Data S1). Further refinement of this analysis could attempt back-extrapolation of parasite emergence from the liver by incorporating parasite replication rates in the presence or absence of T-S, once such data are available. Finally, genotyping was performed at only three loci, which did not allow us to construct haplotypes or identify other mutations in these transporters. Future studies that include higher resolution parasite dynamics and more accurate sequencing may allow us to estimate parasite dynamics over time.

In summary, we provide the first population PK/PD model for lumefantrine in the context of widely used antiretrovirals in children. In our high transmission setting, re-infection was extremely common, and our wide range of lumefantrine exposure allowed us to more fully explore the relationship between recurrent parasitemia and drug exposure. We find that T-S continued to provide significant additional protection against malaria in those with HIV during this study period, despite variations in lumefantrine exposure. More importantly, we demonstrate not only striking selection for alleles associated with reduced lumefantrine sensitivity in two key parasite transporters, but that newly infecting parasites harboring less-sensitive alleles were able to withstand higher lumefantrine concentrations and establish patent infection within approximately 3 to 6 weeks following successful initial treatment. With recent reports of artemisinin resistance emergence in Africa, including in Uganda, it is imperative that we protect ACTs, as they represent the only options for malaria treatment globally.4 In particular, AL represents the most successful and widely utilized ACT, as well as the ACT least susceptible to resistance. As others have suggested, we relay caution that this current success with AL may be threatened, as emergence of artemisinin resistance occurs in backdrop of mutations that confer lower susceptibility to lumefantrine and other partner drugs.16

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

There is no published population pharmacokinetic (PK) model of lumefantrine in HIV-infected children, nor PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) models assessing the impact of lumefantrine concentration on partner drug resistance selection.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

To optimize artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) efficacy and limit the emergence and spread of resistance, it is essential to characterize the PKs and PDs of ACTs, particularly in young children and those with HIV on antiretroviral therapy.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

Lumefantrine exposure is significantly influenced by both age and concomitant antiretroviral regimen, which significantly impacts the risk of recurrent parasitemia. Moreover, lumefantrine exposure is significantly associated with the selection of mutations associated with reduced lumefantrine susceptibility in recurrent infections. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis continues to provide significant protection against malaria in HIV-infected children in our high endemic region.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

Our study demonstrates that repeated malaria treatments with the most widely utilized antimalarial in Africa can select for mutations that lower in vivo susceptibility to the partner drug lumefantrine, findings that have implications in the context of emerging artemisinin resistance in Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the children who participated in the original PK/PD study and their parents and guardians, and to the clinical study team and administrative staff for their support. We would also like to thank Melissa Conrad (UCSF) and Victor Asua (IDRC) for their assistance with the LDR-FM assay.

FUNDING

This work was supported primarily by R01 HD068174 and R21 HD110110 funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32GM136651).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supplementary information accompanies this paper on the Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics website (www.cpt-journal.com).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no competing interests for this work.

References

- 1.World Malaria Report 2021 (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria— June 2022 (Geneva, Switzerland, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes KI, Watkins WM & White NJ Antimalarial dosing regimens and drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 24, 127–134 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balikagala B. et al. Evidence of Artemisinin-Resistant Malaria in Africa. N. Engl. J. Med 385, 1163–1171 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uwimana A. et al. Association of Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H genotypes with delayed parasite clearance in Rwanda: an open-label, single-a rm, multicentre, therapeutic efficacy study. Lancet Infect. Dis 21, 1120–1128 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picot S, Olliaro P, de Monbrison F, Bienvenu AL, Price RN & Ringwald P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for correlation between molecular markers of parasite resistance and treatment outcome in falciparum malaria. Malar. J 8, 89 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sisowath C. et al. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 86 N coding alleles by artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem). J. Infect. Dis 191, 1014–1017 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatesan M. et al. Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and multidrug resistance 1 genes: parasite risk factors that affect treatment outcomes for P. falciparum malaria after artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-a modiaquine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 91, 833–843 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otienoburu SD et al. Selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfcrt and pfmdr1 polymorphisms after treatment with artesunate-amodiaquine fixed dose combination or artemether-lumefantrine in Liberia. Malar. J 15, 452 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques G. et al. Directional selection at the pfmdr1, pfcrt, pfubp1, and pfap2mu loci of Plasmodium falciparum in Kenyan children treated with ACT. J. Infect. Dis 210, 2001–2008 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malmberg M. et al. Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance phenotype as assessed by patient antimalarial drug levels and its association with pfmdr1 polymorphisms. J. Infect.Dis 207, 842–847 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sisowath C. et al. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum parasites carrying the chloroquine-susceptible pfcrt K76 allele after treatment with artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. J. Infect. Dis 199, 750–757 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duraisingh MT, Roper C, Walliker D. & Warhurst DC Increased sensitivity to the antimalarials mefloquine and artemisinin is conferred by mutations in the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol 36, 955–961 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beshir KB et al. Persistent submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia 72 hours after treatment with artemether-lumefantrine predicts 42-day treatment failure in Mali and Burkina Faso. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 65, e0087321 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen C. & Ringwald P. Is there evidence of anti-malarial multidrug resistance in Burkina Faso? Malar. J 20, 320 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson OJ et al. Pre-existing partner-drug resistance to artemisinin combination therapies facilitates the emergence and spread of artemisinin resistance: a consensus modelling study. Lancet Microbe. 3, E701–E710 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloprogge F. et al. Artemether-lumefantrine dosing for malaria treatment in young children and pregnant women: A pharmacokinetic– pharmacodynamic meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 15, e1002579 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mwesigwa J. et al. Pharmacokinetics of artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine in children in Kampala, Uganda. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54, 52–59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tchaparian E. et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lumefantrine in young ugandan children treated with artemether-lumefantrine for uncomplicated malaria. J. Infect. Dis 214, 1243–1251 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria 3rd edn. (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network: Lumefantrine PK/PD Study Group Artemether-lumefantrine treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis of day 7 lumefantrine concentrations and therapeutic response using individual patient data. BMC Med. 13, 227 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarning J. et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperaquine in children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 91, 497–505 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zongo I. et al. Efficacy and day 7 plasma piperaquine concentrations in African children treated for uncomplicated malaria with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. PLoS One 9, e103200 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creek DJ et al. Pharmacokinetic predictors for recurrent malaria after dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Ugandan infants. J Infect Dis 207, 1646–1654 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwenti TE Malaria and HIV coinfection in sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence, impact, and treatment strategies. Res. Rep. Trop. Med 9, 123–136 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mermin J. et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet 364, 1428–1434 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Guidelines on post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and the use of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among adults, adolescents and children: recommendations for a public health approach (Geneva, Switzerland, 2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navaratnam V, Mansor SM, Sit NW, Grace J, Li Q. & Olliaro P. Pharmacokinetics of artemisinin-type compounds. Clin. Pharmacokinet 39, 255–270 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parikh S. et al. Antiretroviral choice for HIV impacts antimalarial exposure and treatment outcomes in ugandan children. Clin. Infect. Dis 63, 414–422 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang L, Li X, Marzan F, Lizak PS & Aweeka FT Determination of lumefantrine in small-volume human plasma by LC-MS/MS: using a deuterated lumefantrine to overcome matrix effect and ionization saturation. Bioanalysis 4, 157–166 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenhouse B. et al. Validation of microsatellite markers for use in genotyping polyclonal Plasmodium falciparum infections. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 75, 836–842 (2006). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeClair NP, Conrad MD, Baliraine FN, Nsanzabana C, Nsobya SL & Rosenthal PJ Optimization of a ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay for characterization of resistance-mediating polymorphisms in African samples of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Clin. Microbiol 51, 2564–2570 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nankoberanyi S. et al. Validation of the ligase detection reaction fluorescent microsphere assay for the detection of Plasmodium falciparum resistance mediating polymorphisms in Uganda. Malar. J 13, 95 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmood I. Dosing in children: a critical review of the pharmacokinetic allometric scaling and modelling approaches in paediatric drug development and clinical settings. Clin. Pharmacokinet 53, 327–346 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chotsiri P. et al. Severe acute malnutrition results in lower lumefantrine exposure in children treated with artemether-lumefantrine for uncomplicated malaria. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 106, 1299–1309 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salman S. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of artemether, lumefantrine, and their respective metabolites in Papua New Guinean children with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55, 5306–5313 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes E. et al. Efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy reduces artemether-lumefantrine exposure for malaria treatment in HIV-infected pregnant women. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 83, 140–147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang L. et al. Concomitant efavirenz reduces pharmacokinetic exposure to the antimalarial drug artemether-l umefantrine in healthy volunteers. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 61, 310–316 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.German P. et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir affects pharmacokinetic exposure of artemether/lumefantrine in HIV-u ninfected healthy volunteers. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 51, 424–429 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francis J. et al. An individual participant data population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of drug–drug interactions between lumefantrine and commonly used antiretroviral treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 64, e02394–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Achan J. et al. Antiretroviral agents and prevention of malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children. N. Engl. J. Med 367, 2110–2118 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panos Z. 2021 HIV market report: the state of HIV treatment, testing, and prevention in low-and middle-income countries. (Clinton Health Access Initiative, Boston, MA, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamya MR et al. Effects of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and insecticide-treated bednets on malaria among HIV-infected Ugandan children. AIDS 21, 2059–2066 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurens MB et al. Revisiting Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for African adults in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis 73, 1058–1065 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manyando C, Njunju EM, D’Alessandro U. & Van Geertruyden JP Safety and efficacy of co-trimoxazole for treatment and prevention of Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a systematic review. PLoS One 8, e56916 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okell LC, Griffin JT & Roper C. Mapping sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in infected humans and in parasite populations in Africa. Sci. Rep 7, 7389 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veiga MI et al. Globally prevalent PfMDR1 mutations modulate Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Nat. Commun 7, 11553 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ehrlich HY, Bei AK, Weinberger DM, Warren JL & Parikh S. Mapping partner drug resistance to guide antimalarial combination therapy policies in sub-Saharan Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 118, e2100685118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ehrlich HY, Jones J. & Parikh S. Molecular surveillance of antimalarial partner drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: a spatial-temporal evidence mapping study. Lancet. Microbe 1, e209–e217 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kay K. & Hastings IM Measuring windows of selection for anti-malarial drug treatments. Malar. J 14, 1–10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bretscher MT et al. The duration of chemoprophylaxis against malaria after treatment with artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine and the effects of pfmdr1 86Y and pfcrt 76T: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMC Med. 18, 47 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.