Abstract

The combination of cinchona-alkaloid-derived primary amine and AuI–phosphine catalysts allowed the selective C–H functionalization of two adjacent carbon atoms of pyrroles under mild reaction conditions. This sequential dual activation provides seven-membered-ring-annulated pyrrole derivatives in excellent yields and enantioselectivities.

Keywords: annulation, gold catalysis, organocatalysis, primary-amine catalysis, pyrroles

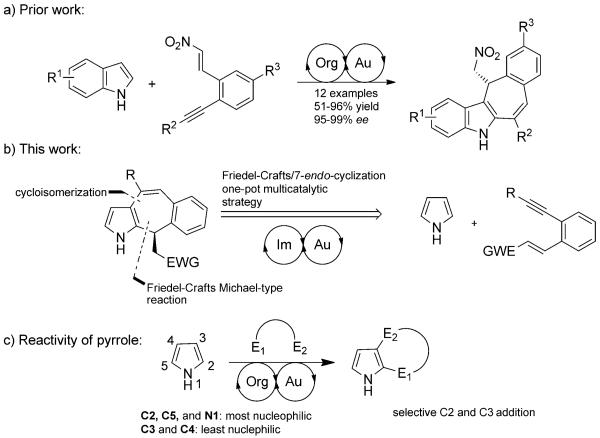

Although gold catalysis and organocatalysis have rapidly grown since the turn of the millennium and emerged as powerful tools in the general field of catalysis, examples of the combination of gold and organocatalysis in sequential and cooperative tandem reactions exploiting complementary activation modes are still scarce.[1-3] Recently, we reported the asymmetric synthesis of tetracyclic indole derivatives containing seven-membered rings by the merger of a thioamide-based organocatalyst with a AuI catalyst to effect two consecutive Friedel–Crafts-type reactions on unsubstituted indole substrates (Scheme 1a).[4]

Scheme 1.

Strategy comparison between current work and our recently reported annulations of indoles.

Due to the immense importance of the indole core, major emphasis has been given to the development of asymmetric Friedel–Crafts reactions involving indole derivatives. Pyrrole is another electron-rich heteroaromatic compound, core of which is found in many natural products.[5,6] One attractive aspect of pyrrole chemistry that is unseen in indole substrates is the inherent nucleophilicity on the C2 position, which stands in contrast to indoles having a classical C3 nucleophilic site. Because Michael-type reactions of pyrroles usually gives 2,5-dialkylated products, it is difficult to monofunctionalize pyrrole substrates (Scheme 1c).[7] To avoid this problem, we wanted to selectively functionalize two adjacent sites on the pyrrolic heterocycle by using two different catalytic modes of activation to generate new annulated pyrrole derivatives in a one-pot reaction, which is quite difficult to achieve by using conventional methods.

Therefore, we report a new asymmetric one-pot dual catalytic protocol that uses primary amine and AuI catalysis to access 2,3-annulated pyrroles containing a seven-membered ring (Scheme 1b). This method is intriguing, because medium-sized rings are difficult to synthesize by conventional organocatalytic methods.[8] Moreover, a publication documenting a AuI-catalyzed 7-endo-dig cyclization mode on pyrrole substrates is not known to date. Such cyclization modes have only been known to occur when platinum or AuIII catalysis was utilized.[9] To the best of our knowledge, the method described herein is the first known example of an asymmetric one-pot operation, in which pyrroles act as a double nucleophile, hence augmenting the operational efficiency of this protocol.

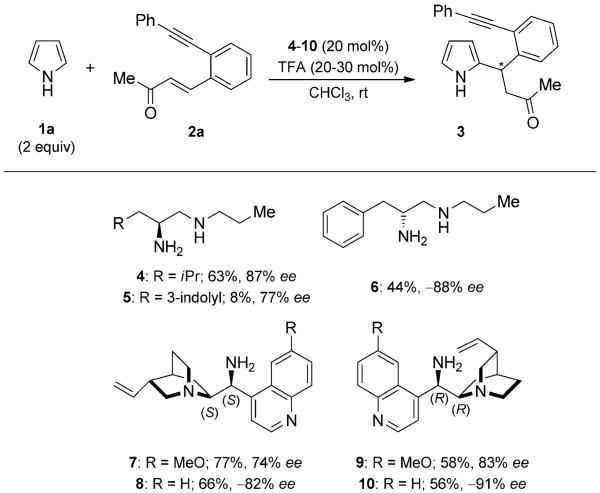

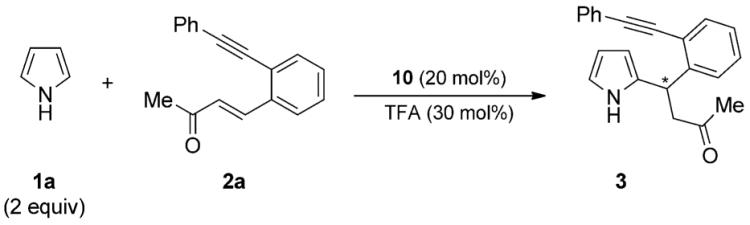

To achieve the annulated pyrrole targets, we first focused on the optimization of the Friedel–Crafts-Michael-type reaction. For the 1,4-addition of pyrrole to enone 2a, primary amines 4–6 derived from amino acids and cinchona-alkaloid-derived amines 7–10 together with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) as additive were employed (Scheme 2).[10,11] The primary amines 4–6 showed poor to good conversions with good enantioselectivity values, whereas the reactions with the primary amines 7–10 were finished within one day and provided comparable or better enantioselectivity values.

Scheme 2.

Catalyst screening for the Friedel–Crafts Michael-type reaction.

The catalyst 10 gave the highest enantioselectivity value, and further optimization was carried out by screening different solvents (Table 1). It turned out that the choice of the solvent did not have any crucial influence on the yield or the observed enantioselectivity values. However, we were able to obtain better yields and slightly improved enantioselectivities at higher dilution and lower temperature. Under these conditions, the amount of dialkylated pyrrole was low, and no other by-products could be observed. This fact is remarkable, because most known methods on 1,4-additions of pyrroles mainly give dialkylated products.[5] We did not investigate the influence of different acids or different amounts of acid, because no beneficial effect was observed in related pyrrole 1,4-additions.[12]

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions for the Friedel–Crafts Michael-type reaction.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent [mL] | t [h] | Yield [%][b] | ee [%][c] |

| 1 | CHCl3 (1.5) | 16 | 56 | 91 |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 (1.5) | 15 | 59 | 87 |

| 3 | toluene (1.5) | 21 | 60 | 88 |

| 4 | PhCl (1.5) | 21 | 61 | 87 |

| 5 | toluene (3.0) | 21 | 70 | 91 |

| 6 | CH2Cl2(3.0) | 24 | 68 | 91 |

| 7[d] | CHCl3 (3.0) | 65 | 89 | 93 |

| 8[d] | toluene (3.0) | 65 | 95 | 93 |

General reaction conditions: 2a (0.5 mmol), pyrrole 1a (1.0 mmol), 10 (20 mol %), TFA (30 mol%), rt.

Yield of isolated 3.

Determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase.

The reaction was performed at 0 °C.

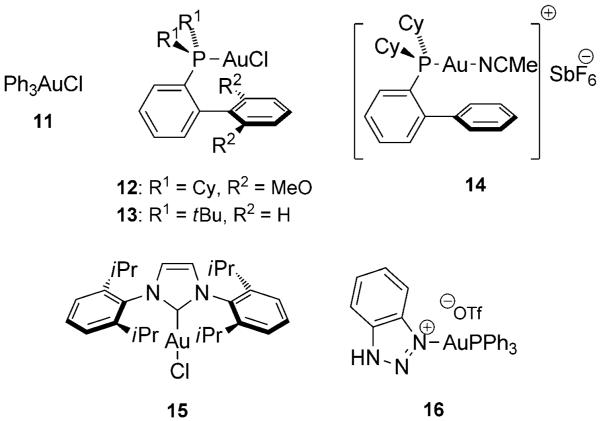

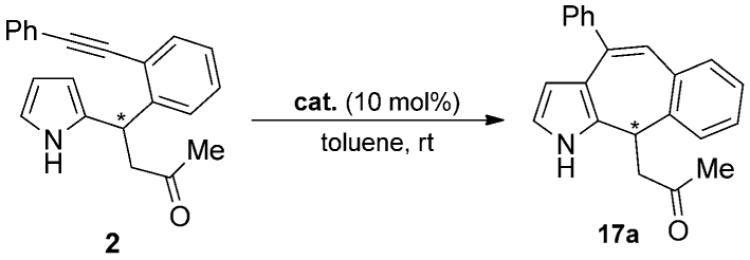

After having optimized the Michael addition, we directed our focus on the cyclization step by screening various gold(I) complexes (Figure 1). We observed that all gold catalysts promoted the cyclization reaction of the Friedel–Crafts product 3 in toluene, generally within 30 min and in excellent yields (Table 2). Only the triazole–gold complex 16 showed lower reactivity due to its higher stability and the strong coordination of the triazole ligand to the gold center (Table 2, entry 6).[13] Although there was no huge difference in terms of yields, using the Echavarren-type catalysts 12–14 resulted in a cleaner isomerization without the formation of unwanted by-products (Table 2, Entry 2-4).[14]

Figure 1.

AuI catalysts employed for the cyclization.

Table 2.

Optimization studies for the gold-catalyzed cyclization.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Additive | t [h] | Yield [%][b] |

| 1 | 11/AgNTf2 | – | 0.5 | 89 |

| 2 | 12/AgNTf2 | – | 0.5 | 89 |

| 3 | 13/AgNTf2 | – | 0.5 | 99 |

| 4 | 14 | – | 0.5 | 92 |

| 5 | 15/AgNTf2 | – | 0.5 | 96 |

| 6 | 16 | – | 30 | 76 |

| 7 | AgNTf2 | – | > 24 | – |

| 8 | CuI | – | > 24 | – |

| 9 | Cu(OTf)2 | – | > 24 | – |

| 10 | PtCl2 | – | > 24 | – |

| 11 | – | 30 mol % TFA | > 24 | – |

| 12 | 13/AgNTf2 | 20 mol % 10 | > 24 | – |

| 13 | 13/AgNTf2 | 20 mol % 10, 30 mol % TFA | 0.5 | 96 |

General reaction conditions: 2 (0.3 mmol), AgNTf2 (10 mol%), toluene (1.7 mL), rt.

Yield of isolated 17a.

It is known from the literature that amines might deactivate gold(I) complexes by coordination to the vacant binding site.[3e-g,k,15] However, the active catalyst can be regenerated upon addition of acidic additives. As was expected, we did not observe any conversion of 3 under the reported conditions when only organocatalyst 10 was present (Table 2, entry 12). On the contrary, the reaction was completed within 30 min, if 30 mol% TFA was also present, and the product 17a was obtained in excellent yields (Table 2, entry 13).

Thus, it was not necessary to add any further additives, because the same amount of TFA had to be already added in the Michael addition. In an additional control experiment, we could show that TFA does not catalyze the cycloisomerization, because no product could be observed after 24 h (Table 2, entry 11). In addition, other metal catalysts containing platinum or copper also failed to promote this reaction, although those metals are strongly associated with the activation of alkynes (Table 2, entries 8–10).

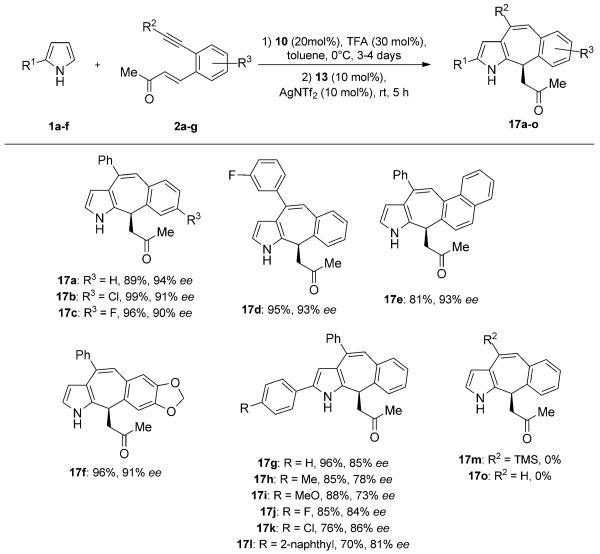

With the optimized conditions in hand, a variety of substituted enones and pyrroles were used to demonstrate the flexibility of the reported method (Scheme 3). To our delight, we obtained good to excellent yields and enantioselectivity values for all enones tested, tolerating electron-withdrawing, as well as electron-donating, groups (EWG and EDG, respectively; 17a–f). Likewise, 2-aryl-pyrroles can also be used for this reaction, albeit with slightly lower yields and enantioselectivity values (17g–l). Apparently, the increased steric bulk introduced by the additional aryl group on pyrrole seems to hamper the transition state in the enantioselective step. In addition, we observed that the products are less stable to acid and heat than the products, which are derived from unsubstituted pyrrole, thus leading to lower yields. Further, we investigated if the method could be extended to enones with terminal alkynes and trimethylsilyl (TMS) protected alkynes. Although both substrates reacted smoothly in the Michael addition, no desired product could be isolated after the gold-catalyzed cycloisomerization.[16]

Scheme 3.

Scope of the sequential Michael addition/cyclization reaction.

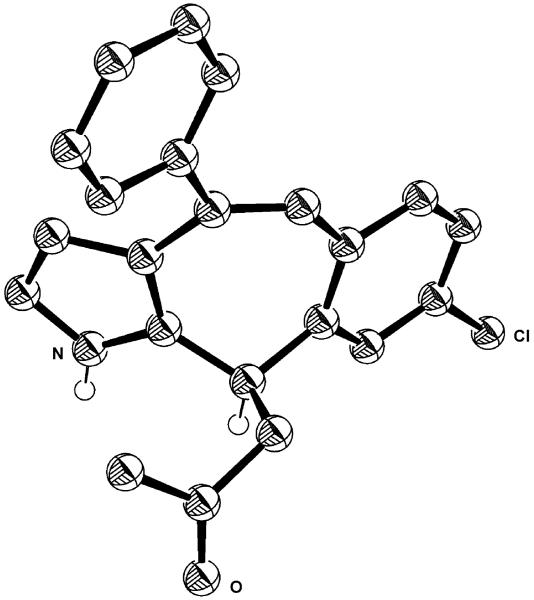

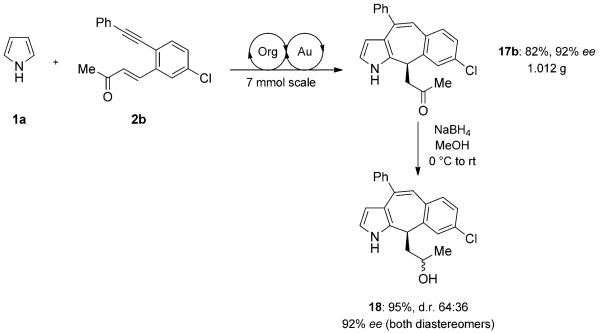

The absolute configuration was assigned by X-ray crystal-structure analysis of (R)-17b (Figure 2).[17] The absolute configuration of the other products was assigned assuming a uniform reaction pathway. To demonstrate the practicability of this protocol, we conducted the asymmetric synthesis of 17b on a larger scale with slightly lower yields, but improved enantioselectivity (Scheme 4). The product was converted to the corresponding alcohol by reduction with sodium borohydride at −78°C to give a mixture of two diastereomers 18 in good yield (Scheme 4).

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of (R)-17 b.

Scheme 4.

Large-scale synthesis of compound 17b followed by reduction to the alcohol 18.

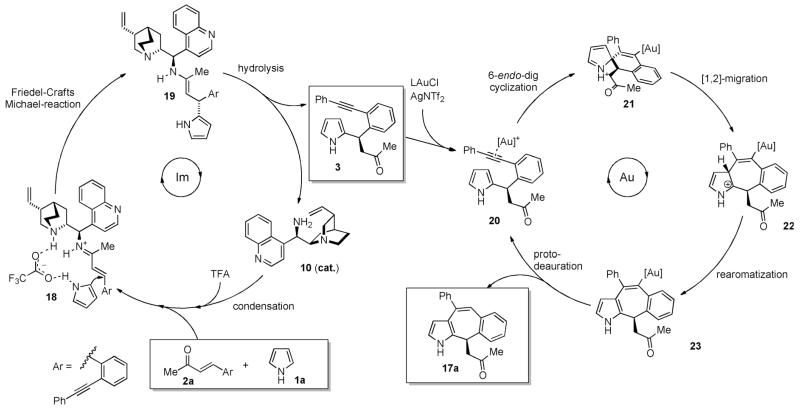

Although we still lack further information on the mechanism, a plausible reaction pathway is depicted in Scheme 5. The organocatalytic reaction is driven by the formation of the iminium ion by condensation of the TFA salt of the primary amine 10 and the enone 2a. This LUMO activation of the substrate facilitates the nucleophilic attack of pyrrole. The observed stereoselectivity can be attributed to the covalent bonding between the enone and the primary amine, as well as hydrogen bonding between pyrrole and the quinuclidine backbone of the catalyst with trifluoroacetate as mediator.[12]

Scheme 5.

Plausible reaction mechanism.

After hydrolysis, the intermediate 3 can enter the gold-catalyzed cycle. In consent with the reported literature, we believe that the mechanism for the gold-catalyzed step can be rationalized by an initiating 6-endo-dig cyclization of the more nucleophilic C2 position of pyrrole to the internal alkyne.[9,18] The alkyne is activated by coordination via the π-acidic AuI complex 20 to form a non-aromatic spirocyclic intermediate 21, which undergoes fast rearrangement to the seven-membered ring 22 followed by rearomatization and protodeauration. Thus, the final products 17 seem to be derived from a 7-endo-dig cyclization.

In summary, we have developed a convenient one-pot asymmetric synthesis of annulated pyrroles based on a rare 7-endo-dig cyclization, thus functionalizing two adjacent carbon atoms on pyrrole by direct C–H functionalization. The combination of a cinchona-alkaloid-derived primary amine and a AuI–phosphine catalyst gave excellent yields and enantioselectivity values, which are rarely achieved in pyrrole chemistry.

Experimental Section

Typical procedure

Freshly distilled pyrrole (69 μL, 1.00 mmol) was added to a solution of 9-amino(9-deoxy)epi cinchonine (10; 29 mg, 0.20 mmol), TFA (16 μL, 0.15 mmol), and enone (0.5 mmol) in toluene (3 mL) at 0°C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0°C, and the progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC analysis. After completion, a suspension of AgNTf2 (10 mg, 0.10 mmol) and catalyst 13 (13 mg, 0.10 mmol) in toluene (1 mL) was added to the reaction mixture at room temperature. After complete conversion, the crude product was directly subjected to flash chromatography (silica, n-pentane/diethyl ether).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

D.H. thanks the DFG (International Research Training Group “Selectivity in Chemo- and Biocatalysis”—Seleca) and D.E. thanks the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant “DOMINOCAT”) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201400407.

References

- [1].For selected general reviews on gold catalysis, see: Hashmi ASK, Hutchings GJ. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:8064. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602454. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7896. Hashmi ASK. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3180. doi: 10.1021/cr000436x. Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:3478. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3410. Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. Muzart J. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:5815. Li Z, Brouwer C, He C. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3239. doi: 10.1021/cr068434l. Arcadi A. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3266. doi: 10.1021/cr068435d. Jiménez-Nún?ez E, Echavarren AM. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3326. doi: 10.1021/cr0684319. Gorin DJ, Sherry BD, Toste FD. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3351. doi: 10.1021/cr068430g. Skouta R, Li C-J. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:4917. Widenhoefer RA. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:5382. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800219. Kirsch SF. Synthesis. 2008;3183 Bongers N, Krause N. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:2208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704729. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2178. Fürstner A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3208. doi: 10.1039/b816696j. Shapiro N, Toste FD. Synlett. 2010:675. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1219369. Sengupta S, Shi X. ChemCatChem. 2010;2:609. Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:5360. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5232. Bandini M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1358. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00041h. Krause N, Winter C. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1994. doi: 10.1021/cr1004088. Pradal A, Toullec PY, Michelet V. Synthesis. 2011:1501. Corma A, Leyva-Pérez A, Sabater MJ. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1657. doi: 10.1021/cr100414u. Rudolph M, Hashmi ASK. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6536. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10780a. Rudolph M, Hashmi ASK. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2448. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15279c.

- [2].For selected reviews on organocatalysis, see: Berkessel A, Grçger H. Asymmetric Organocatalysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. Dalko PI, editor. Enantioselective Organocatalysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2007. c) Special issue on organocatalysis: List B. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5413. doi: 10.1021/cr0684016. Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:9267. de Figueiredo RM, Christmann M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:2575. Enders D, Grondal C, Hüttl MMR. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:1590. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603129. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1570. Dondoni A, Massi A. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4716. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4638. MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2008;455:304. doi: 10.1038/nature07367. Barbas CF. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:44. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:42. Enders D, Narine AA. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7857. doi: 10.1021/jo801374j. Melchiorre P, Marigo M, Carlone A, Bartoli G. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:6232. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705523. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6138. Jørgensen KA, Bertelsen S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2178. doi: 10.1039/b903816g. Bella M, Gasperi T. Synthesis. 2009:1583. Pellissier H. Recent Developments in Asymmetric Organocatalysis. RCS Publishing; Cambridge: 2010. Maruoka K, List B, Yamamoto H, Gong L-Z. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10703. doi: 10.1039/c2cc90327j. Pellissier H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:237. List B, Maruoka K. Asymmetric Organocatalysis (in Science of Synthesis) Thieme; Stuttgart: 2012. Dalko PI, editor. Comprehensive Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Catalysts, Reactions and Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2013.

- [3].Loh CCJ, Enders D. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:10212. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200287. For recent examples, see: Binder JT, Crone B, Haug TT, Menz H, Kirsch SF. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1025. doi: 10.1021/ol800092p. Han Z-Y, Xiao H, Chen X-H, Gong L-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9182. doi: 10.1021/ja903547q. Liu X-Y, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4204. doi: 10.1021/ol901443b. Muratore ME, Holloway CA, Pilling AW, Storer RI, Trevitt G, Dixon DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10796. doi: 10.1021/ja9024885. Belot S, Vogt K, Besnard C, Krause N, Alexakis A. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:9085. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903905. Zweifel T, Hollmann D, Prüger B, Nielsen M, Jørgensen KA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:1624. Jensen KL, Franke PT, Arróniz C, Kobbelgaard S, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:1750. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903405. Wang C, Han Z-Y, Luo H-W, Gong L-Z. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2266. doi: 10.1021/ol1006086. Monge D, Jensen KL, Franke PT, Lykke L, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:9478. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001123. Barber DM, Sanganee HJ, Dixon DJ. Org. Lett. 2012;14:5290. doi: 10.1021/ol302459c. Chiarucci M, di Lillo M, Romaniello A, Cozzi PG, Cera G, Bandini M. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:2859. Patil NT, Raut VS, Tella RB. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:570. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37623g. Wu H, He Y-P, Gong L-Z. Org. Lett. 2013;15:460. doi: 10.1021/ol303188u. Gregory AW, Jakubec P, Turner P, Dixon DJ. Org. Lett. 2013;15:4330. doi: 10.1021/ol401784h.

- [4].Loh CCJ, Badorrek J, Raabe G, Enders D. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:13409. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].For selected asymmetric Michael additions of pyrroles, see: Paras NA, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4370. doi: 10.1021/ja015717g. Cao C-L, Zhou Y-Y, Sun X-L, Tang Y. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10676. Trost BM, Müller C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2438. doi: 10.1021/ja711080y. Sheng Y-F, Gu Q, Zhang A-J, You S-L. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6899. doi: 10.1021/jo9013029. Yokoyama N, Arai T. Chem. Commun. 2009:3285. doi: 10.1039/b904275j. Hong L, Sun W, Liu C, Wang L, Wong K, Wang R. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:11105. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901635. Singh PK, Singh VK. Org. Lett. 2010;12:80. doi: 10.1021/ol902360b. Huang Y, Suzuki S, Liu G, Tokunaga E, Shiro M, Shibata N. New J. Chem. 2011;35:2614. Liu L, Ma H, Xiao Y, Du F, Qin Z, Li N, Fu B. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:9281. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34803a. Chauhan P, Chimni SS. RSC Adv. 2012;2:6117.

- [6].Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. 2003;115:3706. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:3582. Hoffmann H, Lindl T. Synthesis. 2003:1753. Balme G. Angew. Chem. 2004;116:6396. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461073. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:6238. Jolicoeur B, Chapman EE, Thompson A, Lubell WD. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:11531. Walsh CT, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Howard-Jones AR. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:517. doi: 10.1039/b605245m. Gupton JT. Heterocyclic Antitumor Antibiotics. Springer; Heidelberg: 2006. p. 53.

- [7].a) Jorapur YR, Lee CH, Chi DY. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1231. doi: 10.1021/ol047446v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Blay G, Fernández I, Mun?oz MC, Pedro JR, Recuenco A, Vila C. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:6286. doi: 10.1021/jo2010704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nguyen TV, Hartmann JM, Enders D. Synthesis. 2012;44:845. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Borsini E, Broggini G, Fasana A, Baldassarri C, Manzo AM, Perboni AD. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:1468. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Modha SG, Kumar A, Vachhani DD, Sharma SK, Parmar VS, Van der Eycken EV. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10916. doi: 10.1039/c2cc35900f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kumar A, Vachhani DD, Modha SG, Sharma SK, Parmar VS, Van der Eycken EV. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013;2013:2288. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang Y-Q, Zhao G. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:10888. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].For selected reviews and protocols on cinchona-derived amines, see: Xu L-W, Luo J, Lu Y. Chem. Commun. 2009:1807. doi: 10.1039/b821070e. Marcelli T, Hiemstra H. Synthesis. 2010:1229. Cassani C, Martín-Rapún R, Arceo E, Bravo F, Melchiorre P. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:325. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.155. Melchiorre P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109036. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:9889.

- [12].Hack D, Enders D. Synthesis. 2013;45:2904. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Duan H, Sengupta S, Petersen JL, Akhmedov NG, Shi X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12100. doi: 10.1021/ja9041093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Echavarren AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6178. doi: 10.1021/ja042257t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Young PC, Green SLJ, Rosair GM, Lee A-L. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:9645. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50653c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].From our observation, the TMS-protected product decomposed rapidly, whereas the terminal alkyne underwent a complicated rearrangement with loss of the stereocenter to an unidentified product.

- [17].CCDC-977585 (17b) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- [18].England DB, Padwa A. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3631. doi: 10.1021/ol801385h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.