Abstract

Simplified Gō models, where only native contacts interact favorably, have proven useful to characterize some aspects of the folding of small proteins. The success of these models is limited by the fact that all residues interact in the same way so that the folding features of a protein are determined only by the geometry of its native conformation. We present an extended version of a Cα-based Gō model where different residues interact with different energies. The model is used to calculate the thermodynamics of three small proteins (Protein G, Src-SH3, and CI2) and the effect of mutations (ΔΔGU-N, ΔΔG‡-N, ΔΔG‡-U, and ϕ-values) on the wild-type sequence. The model allows us to investigate some of the most controversial areas in protein folding, such as its earliest stages and the nature of the unfolded state, subjects that have lately received particular attention.

Keywords: protein folding, simplified model, mutation free energy

The simulation of the folding of proteins by means of realistic models, like Gromacs (Berendsen et al. 1995) or Amber (Pearlman et al. 1995), is still computationally out of reach. Even more hopeless is the possibility of obtaining from such simulations quantities reflecting the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of the folding process, in keeping with the fact that to acquire this knowledge with meaningful statistics requires the calculation of thousands of folding and unfolding events.

Because of the lack of soluble realistic models, use is commonly made of simplified descriptions of the protein. Among them, a widely used approach is provided by the Gō model (Gō 1983), which makes use of a potential function based on the knowledge of the native structure of the protein. This potential is, as a rule, the sum of two-body terms contributing with −1 if a native contact is formed and zero otherwise. Within this framework, different degrees of approximation can be made concerning the description of the amino acids ranging from all atoms- to Cα-representations.

These models have the virtue of making, by definition, the native state to be the global energy minimum of the system aside from making computationally feasible the description of the folding process. On the other hand, they neglect the chemical properties of the different types of amino acids, treating all of them equally. While these models describe reasonably well the entropy of the chain, they simplify drastically concerning the energy of the system. This fact poses a number of limitations in the usefulness of Gō models. Most noticeably, within this model, the properties of a protein are solely determined by its geometry. This is at variance with the fact that proteins displaying the same (native) structure, but different sequences can display different stability (Guerois et al. 2002), folding rates (Grantcharova et al. 1998; Martinez et al. 1998), and overall folding features (Khan et al. 2003). The hierarchy of events that one gets from Gō model calculations would be dependent only on the geometric separation of residues along the chain (i.e., closer pairs are formed first), while we expect it to also depend on the interaction energy between residues.

To overcome some of these problems, one can modify the Gō model in such a way that native contacts interact with a pair-dependent potential, whereas non-native contacts display only nonspecific core repulsion. This kind of procedure originates from the approach developed by Wolynes and coworkers (for example, see Bryngelson and Wolynes 1987; Onuchic et al. 1997; Shoemaker and Wolynes 1999) (for review, see Onuchic and Wolynes 2004 and references therein) and has been used to distinguish the folding properties of Protein G and Protein L (Karanicolas and Brooks 2002) and to investigate the transition state of S6 (Matysiak and Clementi 2004).

In the following, we make use of a modified Gō model where the parameters that control the pair potential are calculated for each protein from the measurement of the destabilizing effect mutations have on the native conformation (experimental ΔΔGU-N values). The modified Gō model is then applied to three small proteins (Protein G [56 residues], Src-SH3 [60 residues], and CI2 [64 residues]), for which a consistent amount of mutational data is available (see Fig. 1). The effectiveness of the model is first tested comparing the properties of the transition state (namely, ΔΔGU-‡ and ΔΔGN-‡), calculated within the model following the same procedure used to extract those quantities from in vitro experimental data.

Figure 1.

A cartoon representation of proteins G, Src-SH3, and CI2 (images created using VMD software [Humphrey et al. 1996]). Highlighted in dark gray are the fragments of the protein corresponding to the LES of the protein and thus containing, on average, the residues with the most stable and early forming contacts. (A) Protein G: Formed by 56 residues arranged in four β-motifs (β1 [1–9], β2 [12–20], β3 [43–46], and β4 [50–56]) an α-helix (α1 [23–36]), and four turns (Turn 1 [10,11], Turn 2 [21,22], Turn 3 [37–41], and Turn 4 [47–49]). The LES are S1 (4–9), S2 (41–46), and S3 (49–54). They contain essentially all of the hot amino acids (26, 41, 45, 52, 54) (see Fig. 4) and about half of the warm amino acids (6, 7, 20, 31, 34, 35, 51, 53) (see Fig. 4). The docking S2–S3 (essentially equivalent to the docking of β3–β4) leads to a closed LES (see text and Table 2, as well as Broglia and Tiana 2001b). We have thus also colored Turn 4, although strictly speaking, it does not belong to any of the LES. (B) Protein Src-SH3: It is formed by 60 residues arranged as follows; β1 (2–6), RT loop (8–19), diverging turn (20–27), β2 (24–28), β3 (36–41), distal hairpin (36–51), β4 (47–51), 310-helix (51–54), and β5 (54–57). The LES are S1 (3–10), S2 (18–26), S3 (36–44), and S4 (47–51). They contain all of the hot (10, 18, 20, 26, 50) and warm (5, 7, 23, 24, 38, 41, 44, 48, 49, 51) amino acids (see Fig. 5). The docking of S3–S4 LES gives rise to a closed LES and stabilizes the distal hairpin. Even if all of its amino acids do not belong to S3 + S4 (i.e., 42–46), we have colored the whole motif, (clearer tone used for amino acids outside S3 + S4). The docking of S1–S2 gives rise to a second (closed) LES, leading also to the formation of the RT loop and the diverging turn (see Table 3). Thus, we have also colored the fragment 11–17 (with a clearer tone), although this fragment of the protein does not strictly belong to any of the LES. (C) Protein CI2: Formed by 64 residues arranged in the following motifs: β1 (3–5), β2 (10–11), α1 (12–24), β3 (28–34), reactive loop (35–44), β4 (45–52), β5 (55–58), and β6 (60–64). The LES are S1 (29–34), S2 (45–52), and S3 (55–64). They contain all of the hot amino acids of the protein (29, 47, 49, 50, 57) (see Fig.6) and most of the warm amino acids (30, 32, 34, 51, 52, 58, 60) (see Fig.6) The docking of S2–S3 gives rise to a (closed) LES. This is the reason why we have also colored (clearer tone) amino acids 53 and 54 (Turn 2), although they actually do not belong to any of the LES.

We then study the dynamics of structure formation during the folding process, starting from random conformations. For the three proteins under consideration, we find a well-defined sequence of events, where first, stable local elementary structures (LES) (Broglia et al. 2004) are formed, involving a small set (two to four) of fragments of the protein stabilized by some of the most strongly interacting amino acids. When these structures build their mutual native contacts, which is the post-critical FN (Abkevich et al. 1994), the transition state is overcome and the protein folds on very short call to its native conformation. The post-critical FN is defined in Abkevich et al. (1994) as “the minimal sized fragment of the new phase (i.e., the folded phase) that inevitably grows further to the new phase”; consequently, it lies beyond the transition state, its formation being a sufficient and necessary condition for folding. The LES can be defined as the fragments of consecutive residues that build out the post-critical FN (Broglia et al. 2004). Note that the definition we used for the (post-critical) FN, as the minimum set of native contacts that brings the system over the highest barrier of the free energy associated with the folding process, is not inconsistent with the definition of Abkevich et al. (1994). This dynamic picture centered around the LES and the FN is somewhat complementary to the chemical view of protein folding, which emphasizes the transition state. The free-energy-defined transition state, arising from the interpretation of protein folding as a chemical reaction, can be structurally evanescent and suffers the lack of a set of grounded reaction coordinates. The FN, on the other hand, is not located precisely on the free-energy landscape (one only knows that it is in the native basin), but it is structurally well defined and reflects directly the sequence of folding events.

The idea that a hierarchical set of events leads proteins to their native state, avoiding a time-consuming search through conformational space, is well established. Ptitsyn and Rashin (1975) observed a hierarchical pathway in the folding of Mb. Lesk and Rose (1981) identified the units building the folding hierarchy of Mb and RNase on the basis of geometric arguments, deriving the complete tree of events that lead these proteins to the native state. All of these works describe a framework where small units composed of few consecutive amino acids build larger units that, in turn, build even larger ones, which eventually involve the whole protein. This mechanism has been suggested to take place also for proteins that apparently follow a nonhierarchic route, such as those described by the nucleation-condensation model (Baldwin and Rose 1999). The kinetic advantage of this mechanism (as compared with nonhierarchical scenarios) is that, at each level of the hierarchy, only a limited search in conformation space is needed for the smaller units to coalesce into the larger units belonging to the following level of organization (Panchenko et al. 1995). An analytical model developed by Hansen and coworkers (Hansen et al. 1998), although lacking in molecular detail, has shown that a hierarchical folding mechanism is not incompatible with a cooperative folding transition, like that displayed by two-state folders.

Making use of a simplified model in which a protein is described as a chain of beads on a cubic lattice interacting through a contact potential, it was shown (Broglia and Tiana 2001a; Tiana and Broglia 2001) that designed sequences fold by building (at the very beginning of the dynamical process) LESs composed of a few consecutive amino acids and stabilized by the most attractive contact matrix elements. The folding time is essentially determined by the time needed by the LES to dock, thus forming the FN. After this event has taken place, the remaining residues fold very rapidly, due to the strongly reduced size of the conformational space remaining. Moreover, by exploiting the hierarchical character of the folding mechanism, it has been possible to successfully predict the native conformation of lattice model-designed proteins from the knowledge of the sequence and of the potential function alone (Broglia and Tiana 2001b), in other words, to solve the protein-folding problem of designed proteins in the lattice.

In conclusion, one should remember that the proteins under study (Protein G, Src-SH3, and CI2) are domains of real proteins. In particular, Protein G corresponds to the binding domain of the streptococcal bacterium to which the mammalian immunoglobulin IgG attaches to signal the immune system of the host of the presence of an intruder. To which extent the rest of the protein may affect the folding of the corresponding domains is not known in detail. Because the picture of the folding process based on the concept of LES emerged from the study of designed (lattice) model proteins (Broglia and Tiana 2001a,b; Tiana and Broglia 2001) as well as of real proteins (e.g., like the HIV-1-PR; Levy et al. 2004; Broglia et al. 2005), it may not be exactly applicable to the proteins under consideration. However, it will be shown that the present picture of the folding process seems to be quite appropriate and describes the folding of the G, SH3, and CI2 domains.

Results

Derivation of the potential

To be able to carry out extensive simulations, the atomic structure of the amino acids was neglected and each monomer was substituted by a hard sphere centered at position Cα (see Materials and Methods for details about the geometric aspects of the model).

The choice of the potential function is a key issue of the present work. Current force fields based on the chemical properties of amino acids meet, as a rule, difficulties in predicting detailed properties of natural proteins (Lazaridis and Karplus 1999). For this reason, use is made of a potential based on the native conformation of the protein and on the experimental free-energy changes upon the mutation that gives an energy Bij to every pair of residues i,j building a native contact. That is,

|

where ri is the position of the ith residue, Bij is the matrix element giving the interaction between the ith and jth residue, θ(x) is the Heaviside step function that assumes the value 1 if x >0 and 0, otherwise, {rNi} are the coordinates of the crystallographic native conformation, R is the interaction range, while ɛ is a hard-core repulsion energy set to 100 kBT (see Materials and Methods).

The numerical values of the matrix Bij are calculated from the experimental values of the change in free-energy ΔΔGU-N of the native state with respect to the unfolded state upon mutations. Assuming that (1) the entropy of the native state does not change after the mutation, (2) the effect of the mutation is to make the interaction energy of the mutated amino acid negligible, and (3) the interaction energy Bij cannot grow above max(-ΔΔGU-N (i), -ΔΔGU-N (j)), one can write

|

If all ΔΔGU-N(i) were known, Equation 2 provides a set of L linear equations (L being the number of the amino acids that form the protein and thus determine its length) in the variables Bij, whose number is γL/2 (γ being the average number of contacts that each amino acid builds in the native conformation). Since usually γ > 2, the number of variables exceeds that of equations, and one can determine the quantities Bij except for γL/2-L free parameters. In general, this allows the Bij to range over all real numbers. On the other hand, the assumption (3) constrains the values of Bij from above, making the range of uncertainty much smaller. The rationale behind this assumption is the “principle of minimal frustration,” according to which protein sequences have evolved over millions of years, decreasing, to the maximum extent, the energetic contradictions among amino acids (Bryngelson and Wolynes 1987). In other words, a residue building two contacts, for example, without the constraint, could increase the energy of one of them by an arbitrary value while decreasing the other by the same amount. This would increase the frustration of the system due to the presence in the native state of a large repulsive interaction. The effect of the constraint (3) stated above is to prevent an amino acid with a given value of ΔΔGU-N(i) from giving rise to energies Bij, which are very large in absolute value and which, through strong cancellation, lead still to the right native conformation energy, but at a strongly reduced stability. Note that numerical values of ΔΔGU-N(i) are often not available for all residues, giving rise to an even larger number of free parameters. To circumvent this obstacle, we have stochastically solved the set of equations, producing a statistically representative set of solutions; the parameters Bij used correspond to the average of these solutions.

While we shall solely use this value of Bij in all calculations presented in this report, it is of interest to compare these results with those obtained, making use of GROMACS. This is done in Figure 2, where we display the energy (=Σj Bij) associated with each residue i of the three proteins under study in their native conformation. While marked deviations between the two sets of energies are observed, the overall trend of the empirical values is in overall agreement with the values calculated with GROMACS. We note that the energies associated with the empirical Bij values deduced from ΔΔGU-N measurements display a smoother behavior than that associated with the realistic potential (GROMACS). This difference indicates that the prescription based on Equation 2 and conditions (1–3) above is likely to distribute the contact energies associated with the mutated amino acids much too uniformly among those residues that have not been subject to mutations. Consequently, one would expect that the features observed with the present generalized Gō model are less marked than those one would obtain carrying out a full dynamical simulation with GROMACS (not possible to date).

Figure 2.

Energies Σj Bij (solid dots) per monomer in the native conformation of Protein G (A), Src-SH3 (B), and CI2 (C), determined by making use of the interaction energies Bij calculated from the experimental values of ΔΔGU-N (see text) in comparison with the corresponding quantities calculated using the software GROMACS (open squares).

Model calculations of experimentally accessible quantities

In order to validate the model, we have investigated a number of quantities associated with the native (N), transition (‡), and unfolded (U) state of proteins and compared them with the experimental data.

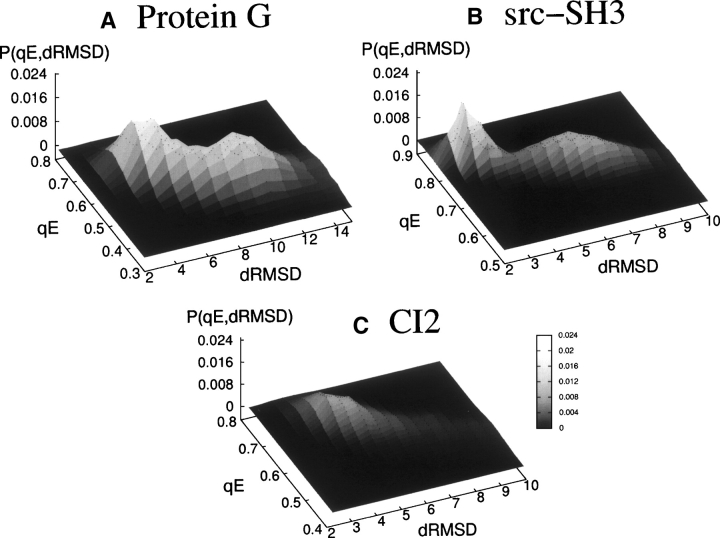

In the case of Protein G (cf. Fig. 1A) the experimental ΔΔGU-N, ΔΔG‡-N, and ΔΔG‡-U are available for 26 of 56 residues (Park et al. 1999; McCallister et al. 2000). The associated Bij matrix has an average value <E> =−0.56 and a standard deviation σ = 0.44 expressed in kcal/mol, (kB = 1). Making use of these energies, Monte Carlo simulations have been performed in order to elucidate the thermodynamics of the protein. In particular, we have studied the parameters qE, which is the fraction of native energy E/EN of a given conformation, and the distance RMSD

|

where dijN is the relative distance between amino acids i and j in the native conformation, while N is the total number of amino acids. The equilibrium probability p(qE,dRMSD) is displayed in Figure 3A, as a function of qE and dRMSD. The probability shows two peaks, one associated with the native state (high qE and low dRMSD) and the other associated with the unfolded state (low qE and high dRMSD).

Figure 3.

The equilibrium probability of (A) Protein G (at T/Tf =1.13), (B) Src-SH3 (at T/Tf =1.1), and (C) CI2 (at T/Tf =1.05) as a function of the relative energy parameter qE and of the dRMSD. Whereas in the Protein G and the Src-SH3 the two peaks representing the native and the unfolded state are well defined, for the CI2, the peaks are smoother, indicating a less-cooperative transition between states.

The folding temperature for Protein G, at which the population of the native state is equal to that of the unfolded state, is Tf =0.37 (in kcal/mol, with kB = 1). Note that this is, in absolute terms, an unrealistically low temperature (45 K), which reflects the approximations introduced in the model (i.e., consider only the Cα, neglect of the solvent, etc.). In fact, in a model controlled by less degrees of freedom than the actual number of degrees of freedom of the system under consideration, one expects that entropy changes are more abrupt than those taking place in the real system. Since temperature is defined as the inverse derivative of entropy with respect to energy, the increased steepness of entropy results in lower temperatures. For this reason we will express temperatures relatively to Tf.

Within this context, the conversion of Monte Carlo steps (MCs) to time used below may resent the reduced number of degrees of freedom explicitly treated by the model (for more details see Materials and Methods).

Defining operatively a mutation as a switch off of all the native contacts that the mutated residue displays in the native conformation, it is possible to calculate the effect of mutations on the folding and unfolding of the protein (see Materials and Methods). A comparison between model-calculated and experimental values of the variation of free energy ΔΔG‡-N, ΔΔGU-N, and ϕ-values is displayed in Figure 4. The correlation coefficients r and the RMSD σ between theoretical and experimental values are listed in Table 1 (first row) and indicate an acceptable degree of performance of the model. We have repeated the above calculations using a model with the same geometry, but with a pure Gō potential (i.e., Bij =−1 for all native pairs). The results are also shown in Table 1 (second row) and indicate a decrease of the correlation coefficient and an increase of the RMSD as compared with the corresponding values of the pair-specific potential used in the extended Gō model, with the exception of ΔΔG‡-U.

Figure 4.

ΔΔG‡-N, ΔΔGU-N(kin) (kcal/mol), and ϕ = 1−ΔΔG‡-N/ΔΔGU-Nexp values associated with Protein G. Black histograms correspond to experimental values of the different quantities, whereas dashed histograms correspond to the prediction of the model.

Table 1.

The correlation coefficient r (and, in parenthesis, the associated RMSD σ) between the experimental and calculated mutation parameters (cf. Materials and Methods) for the three proteins

The thermodynamics calculations have been repeated within the framework of the present model also for Src-SH3 and CI2 (Fig. 1, cf. B and C), calculating the interaction matrices Bij from the experimental ΔΔGU-N (Itzhaki et al. 1995; Riddle et al. 1999), which are known for 37 of 60 residues and 33 of 64 residues, respectively. The two matrices are characterized, respectively, by an average energy <E> =−0.29 and <E> =−0.53 and standard deviation σ = 0.37 and σ = 0.47 expressed in kcal/mol (with kB = 1). Making use of the matrix elements Bij, the energies Σj Bij associated with each amino acid i in the native conformation were calculated. The resulting values are displayed in Figure 2, B and C, in comparison with the prediction of the software GROMACS. The agreement in the case of the Src-SH3 protein is excellent, while in the case of protein CI2, the same comments made in connection with Protein G (see Fig. 2A) applies (overall reproduction of trend but conspicuous local deviations).

The equilibrium probabilities p(qE,dRMSD) for these two proteins are displayed in Figure 3, B and C, respectively, and show a two-state behavior for Src-SH3. On the other hand, the peaks for CI2 are quite broad, much more than in the case of Src-SH3, suggesting a less-cooperative folding process, results that are compatible with the experimental data. The folding temperatures associated with Src-SH3 and CI2 proteins are Tf =0.21 and Tf =0.32 kcal/mol, respectively. The results concerning mutations are displayed in Figures 5 and 6, while the correlations with the experimental data are listed in Table 1 (third and fourth rows). The data indicate that, while the ability of the model in predicting the ΔΔG‡-N and ΔΔGU-N is still acceptable, the ΔΔG‡-U and ϕ-values are completely missed. The meaning of these results will be addressed in the Discussion section.

Figure 5.

The same as Figure 4, calculated for Src-SH3: from above: the ΔΔG‡-N, the ΔΔGU-N(kin) in kcal/mol and the ϕ-values calculated from ϕ = 1−ΔΔG‡-N/ΔΔGU-Nexp.

Figure 6.

The same as Figure 4, calculated for CI2: from above: the ΔΔG‡-N, the ΔΔGU-N(kin) in kcal/mol and the ϕ-values calculated from ϕ = 1−ΔΔG‡-N/ΔΔGU-Nexp.

Folding events

The interest of the model is that it allows for the study of the early events of folding, a subject of particular interest in view of recent experimental developments (Religa et al. 2005). We have performed 200 dynamical simulations for each of the three proteins, starting from random conformations recording the mean value [qE](t) of qE and the probability of formation of each native contact pi-j(t) as a function of time.

Protein G

The results for Protein G at T/Tf =0.54 are displayed in Figures 7A and 8. The curve [qE](t) is well fitted by the sum of two exponentials, of characteristic times of the order of 10 nsec and 1 μsec, respectively. Note that continuous-flow experiments (McCallister et al. 2000) performed at acidic conditions can be fitted by two exponentials of characteristic times, 300 μsec and 2 msec, respectively, while at neutral pH, only one exponential is observed at submillisecond time scale. Consequently, the results of our model, whose parameters are obtained from ΔΔGU-N measured at neutral pH, are not incompatible with the folding kinetics, since the nanosecond events fall in any case under the instrumental dead time.

Figure 7.

The contact map of (A) Protein G, (B) Src-SH3, and (C) CI2 at T < Tf. The colors qualitatively indicate, in the top half of the map (labeled a) the equilibrium probability of contact formation (black corresponding to the maximum contact stability), while in the bottom half (b) the formation times of the contacts are displayed (black squares indicates a formation time of 0.1 nsec, gray squares of 10 nsec and light gray of 1 μsec).

Figure 8.

Average similarity parameter [qE](t) as a function of time, which characterizes the folding dynamics of Protein G at a temperature T/Tf =0.54 (black central curve) with its exponential fit (gray central curve). The other two curves represent the formation probability pi-j(t) of contacts 44–53 (fast forming) and 5–52 (slow forming).

According to the pi-j(t) (cf. Figs. 7A, 8 and 9 and Supplemental Material), the first structures that are formed within the first nanosecond are the second hairpin (residues 41–56) and the most local contacts within the α-helix. The former starts from the turn (contacts 46–49 and 47–50) and closes up until contact 44–53, but also up to contact 39–56 (see Fig. 9II). All of these early contacts are very stable (cf. Fig. 7A, a) and their dynamics are single-exponential (cf. Fig. 8, dark-gray curve p44–53(t)). The folding process then proceeds with the formation of the first hairpin (residues 1–20) and the further stabilization of the second hairpin that ends after 10 nsec (contact 41–54). Whereas the formation of the second hairpin resembles the closure of a zip (see the color gradient associated with strands β3–β4 in Fig. 7A, b, as well as Fig. 9), this behavior is not seen for the first hairpin (strands β1–β2 in Fig. 7A, b). The formation of the full α-helix and the formation of the contacts between the two hairpins (strands β1–β4 in Fig. 7A) take place on a much longer time scale than the previous events (i.e., microseconds) following a nonexponential dynamics (cf. Fig. 8, where the dark-gray curve p5–52(t) represents a contact between strands β1–β4). As expected, the most stable contacts are the ones within the hairpins and within the α-helix, while the less stable are those across the hairpins (cf. Fig. 7A, a).

Figure 9.

Contact formation diagram for Protein G. The black bead indicates the first residue. (I) A snapshot of the random starting conformation (t = 0, dRMSD = 23.2Å), (II) the α-helix and the contacts between β3 and β4 are formed (t = 1 nsec, dRMSD = 12.2Å), (III) the folding process proceeds with the formation of the native contacts between β1 and β2 (t = 0.76 μsec, dRMSD=12.8Å), (IV) the protein reaches its native conformation once β1-β4 dock together (t = 0.99 μsec, dRMSD = 5.3Å).

These results can also be interpreted in terms of three LES S1 (4–9), S2 (41–46), and S3 (49–54), which essentially control the folding process (see Table 2). Because S2 and S3 dock very fast (0.1–1 nsec) giving rise to a closed LES (second hairpin (41–54), we can equally well describe the folding of Protein G in terms of S1 (open LES) and S2 + S3. In fact, the docking of S1 to S2 + S3 lead to the post-critical folding nucleus (FN). This event takes place in about 1–1.5 μsec (dRMSD ∼5.3Å) for the trajectory shown in Figure 9, shortly after which the protein folds (folding time τf ≈ 2 μsec) (see also Supplemental Materials).

It is known that LES structures are, as a rule, stabilized by strongly interacting, highly conserved amino acids. Mutation of hot amino acids (typically 8%–10% of all the amino acids) have the largest impact on the ability the protein has to fold. Mutation of warm amino acids (typically 17%–20% of all amino acids), although as a rule not leading to denaturation, can slow to a certain extent the folding process and eventually slightly alter the native conformation (Broglia et al. 2004).

From Figure 4 it is seen that the five (≈0.08 × 56) amino acids occupying sites 21, 41, 45, 52, and 54 have the largest impact on the ability the protein has to fold (see Fig. 4), and thus can be viewed as hot amino acids (for example, see Broglia et al. 2004). Within this picture, the 10 (≈0.17 × 56) amino acids 6, 7, 20, 22, 31, 34, 35, 39, 46, and 51 can be viewed as warm amino acids. Note that S2 and S3 are built out by all (but one, namely amino acid 21) hot amino acids, while S1 contains two warm amino acids.

Protein Src-SH3

Analogous simulations have been performed for the Src-SH3 protein at T/Tf =0.86, giving a two-exponential fit of the curve [qE](t) with characteristic time 13 nsec and 2 μsec (data not shown). From the contact map of stability and formation time displayed in Figure 7B as well as from Figure 10 (see also Supplemental Materials), it is shown that the first contacts that get formed are the most local ones within the distal hairpin (contacts 41–44 and 42–45 forms in 0.1 nsec) and within the 310-helix (contacts 52–55). In the same short time scale, contact 21–24 of the diverging turn is fully stabilized. The folding then proceeds with the full formation of the distal hairpin, which reaches its maximum stability when contact 36–51 forms (5–10 nsec). After this, in a time scale of the order of 30–50 nsec, the RT loop and the contacts between strands β1 and β2 get formed. These contacts, together with the distal hairpin, give rise to the most stable structures of the protein (cf. Fig. 7B, a). The next events take place on a much longer time scale (≈0.25 μsec) and involve the docking of strand β2 to β3, strand β4 to the RT loop, and finally, strand β1 to β5. These last events occur almost simultaneously and lead the protein to its compact native conformation.

Figure 10.

Contact formation diagram for Src-SH3. The black bead indicates the first residue. (I) The most local contacts and contacts between β3 and the distal hairpin get formed (t = 1 nsec, dRMSD = 19.4Å), (II) contacts between β3 sand β4 and between the n-src loop and β4 are fully stabilized (t = 5 nsec, dRMSD = 15.2Å), (III) the RT-loop assemble with the diverging turn and β1 with β2 (t = 0.33 μsec, dRMSD = 6.7Å), (IV) the main structures dock together: the RT loop with β4, β1 with β5, and β2 with β3 (t = 0.58 μsec, dRMSD = 3.0Å).

The folding of the Src-SH3, associated with a folding time τf ≈ 2 μsec can also be interpreted in terms of the LES S1 (3–10), S2 (18–26), S3 (36–44), and S4 (47–51) (local elementary structures which, used as peptides [p-Si (i = 1,2,3,4)] in the typical ratio 3:1 [peptide-protein], strongly inhibits the folding of the protein [Broglia et al. 2004, 2005]). These LES contain all of the hot (10, 18, 20, 24, 26, 50) and warm (5, 7, 23, 38, 41, 44, 48, 49, 51) amino acids, as emerged from the experimental ΔΔGU-N values (see Fig. 5). The formation of the native bonds between S3 and S4 gives rise very early in the folding process (5–10 nsec) (see Fig. 10, II and Supplemental Materials) to the distal hairpin (see Table 3), structure that can be viewed as a closed LES. Somewhat later, but still at the very beginning of the folding process (30–50 nsec; see Fig. 10, III and Supplemental Materials), S1 and S2 form their local contacts, leading to the formation of the RT loop and the diverging turn, structure that can be viewed as the second closed LES. Most of the folding time is spent by the two closed LES in exploring conformational space in search of the correct relative distance and orientation leading to their docking. This event, which takes place after ∼1.6–1.8 μsec (see Fig. 10, IV and Supplemental Materials) gives rise to the (post-critical) FN; shortly after the remaining amino acids find their native position and the protein reaches, for the first time, the native conformation (2 μsec).

Table 3.

Protein Src-SH3 LES and (in parenthesis) initial and the final amino acids number forming them

Table 2.

Protein G LES and (in parenthesis) initial and final amino acids number forming them

Protein CI2

Finally, analyzing the contact map displayed in Figures 7C and 11 (see also Supplemental Materials) and the curves [qE](t) and pi-j(t) for the protein CI2 at T/Tf =0.94, the same kind of reconstruction of the hierarchy of events that leads the protein to its native structure has been performed. The curve [qE](t) is well fitted by two exponentials of characteristic time 30 nsec and 1 μsec (data not shown). The first group of contacts that are formed in the first 0.1 nsec are all local ones and involves the first turn, essentially all the α−helix, and the turn between the strands β4 and β5 (cf. Fig. 7C, b; see also Fig. 11, I). Note that the fast folding of the α−helix does not imply strong stability. In fact, as shown in Figure 7C, a, only the two ends of the helix (contacts 13–16, 22–25, and 24–27) are well structured in the unfolded state. The folding proceeds with the formation of the native contacts between strands β4 and β5 and afterward between strands β4 and β6. This process ends after nearly 20 nsec, when the biggest time gap occurs before the next strongly interacting structures, strands β3 and β4, meet each other and dock. This occurs after 0.6–0.95 μsec and it is the strongest constraint to the conformational freedom of the chain that closes the reactive site loop (see Fig. 11, III).

Figure 11.

Contact formation diagram for CI2. The black bead indicates the first residue. (I) Formation of the most local contacts within the α-helix (t = 2 nsec, dRMSD = 21.6Å), (II) the β strands β4–β5 and β4–β6 dock together (t = 20 nsec, dRMSD = 20.8Å), (III) the formation of contacts between strands β3 and β4 closes the reactive site loop (t = 0.65 μsec, dRMSD = 18.7Å), (IV) the docking of the farther strands along the chain β1–β6 and β2–β5 brings the protein to its globular native structure. A further stabilization of the α-helix then follows (t = 1.3 μsec, dRMSD = 4.3Å).

The folding of the CI2 protein (folding time τf ≈ 1 μsec), a trajectory of which is shown in Figure 11, can also be described in terms of the LES: S1(29–34) = β3, S2(45–52) = β4, and S3(55–64) = β5 + β6. Note that these corresponding fragments of the protein used as peptides (3:1 ratio) strongly inhibit the folding of the protein. From the analysis of Figure 6, one can read the hot and warm amino acids associated with protein CI2. These are (see ΔΔGU-N) 29, 47, 49, 50, 57, and 8, 17, 24, 30, 32, 39, 51, 52, 58, and 60, respectively. Consequently, the three LES contain all of the hot amino acids and six of the 10 warm amino acids. The formation of the contacts between the S2 and S3 LES (i.e., between β4 and β5 + β6) very early in the folding process (20 nsec) (see Fig. 11, II) leads to a closed LES (S2 + S3 [β4 + β5 + β6]). Most of the folding time is spent for S1 and S2 + S3 to explore conformation space to establish the corresponding native contacts. When this happens (0.6–0.95 μsec), the folding nucleus is formed (see also Table 4). Shortly after, the protein reaches the native conformation.

Table 4.

Protein CI2 LES and (in parenthesis) initial and final amino acids number forming them

Discussion

Early events in protein folding

The introduction of a residue-dependent pair potential extends the traditional Gō model so as to obtain a better overall correlation with the experimental data. Consequently, we also expect that the description of the folding events, which are usually not detectable experimentally, is more realistic. For example, simulations of the folding of Protein G made with a standard Gō model show three different folding pathways (Shimada and Shakhnovich 2002), according to which the protein forms in the intermediate state either the first hairpin, or the second hairpin, or both. Alternatively, our simulations indicate that the second hairpin folds in less than a nanosecond with probability close to 1, while the contacts between strands β1 and β4 are formed only later, corresponding to the post-critical FN, and thus the transition to the native state. The difference between the two results is due to the fact that in the standard Gō model, the folding is only determined by the geometry of the native conformation, which in the case of Protein G is essentially symmetric with respect to the plane normal to the β-sheet. The fact that our modified Gō model introduces different contact energies for the two hairpins breaks this symmetry, allowing the second hairpin to fold faster than the rest of the structures.

The overall picture that emerges for all three proteins under consideration is compatible with the experimental data available and supplements them when this is not available (e.g., on short time scales, etc.). In the case of Protein G, the early events are the formation of the second hairpin and partially of the first (few nanoseconds), and some local contacts in the helix (hundreds of picoseconds). The rate-limiting step of the folding process is the formation of the contacts between the two hairpins (milliseconds).

The early formation of these structures is then crucial for the overall folding of the protein, as already shown in the case of simpler protein models (Broglia and Tiana 2001a; Tiana and Broglia 2001; Broglia et al. 2004). Furthermore, their formation is essentially independent of the rest of the protein. In fact, the formation dynamics of these structures display a single-exponential behavior (cf. Fig. 8), compatible with the idea of spontaneous formation. A contact probability pi-j(t) following a single-exponential dynamics suggests a two-state scenario described by the equation

|

where the inward and outward rates (i.e., aij and bij, respectively) are constant. Constant rates imply that the formation of the contact between the ith and jth residue does not depend on the degree of formation of any other contact (which, in turn, would depend on time). The fact that the dynamics of bonds across the two hairpins is nonexponential (cf. Fig. 8) suggests that the associated rates aij and bij depend on time, that is, on the degree of formation of the hairpins themselves. These results are in agreement with circular dichroism and NMR spectra of isolated fragments of Protein G in solution. These experiments indicate that the first hairpin is partially structured close to the turn, while the second hairpin is stable (Blanco et al. 1994).

The double exponential dynamics of the overall [qE](t) displayed in Figure 8 reflects the two hierarchies of events discussed above, that is, formation of local elementary structures (the two hairpins) and their docking. The fact that at neutral pH one can observe only the slower of them reflects the limits of standard experimental techniques. However, the presence of two time scales in the dynamics does not necessarily imply the presence of metastable intermediates populated at equilibrium. In fact, this is not the case for our simulations (cf. Fig. 3), a result that agrees with those of microcalorimetry experiments (Alexander et al. 1992).

The same kind of scenario applies for the Src-SH3 protein. Within the first nanoseconds the distal hairpin, the 310-helix, and the diverging turn get stabilized, while their assembly takes place together with the overall folding of the protein. The results of model calculations agree with the hypotheses of Baker and coworkers (Grantcharova et al. 1998; Riddle et al. 1999) on the basis of ϕ-value analysis concerning the fact that “the distal hairpin is the most ordered structural element in the transition state,” that “the interactions made by the diverging turn residues in the transition state may be greater than indicated by ϕ-value analysis” (Riddle et al. 1999), and that “the rate-limiting step involves the formation of the distal-loop hairpin and the docking of the hairpin onto the diverging turn and the strand following it” (Grantcharova et al. 1998). We also find some degree of structure in the RT loop and in the n-src loop, although their formation follows that of the faster structures listed above. The main differences in our results with the interpretation of the experimental data is the early stabilization of the 310 helix and, partially, of the RT loop. On the other hand, unfolding simulations performed by Tsai et al. (1999) show a late disruption of these two fragments of the protein. Although the unfolding pathway is not necessarily the reverse of the folding one (Zocchi 1997), the results quoted above could indicate that ϕ-values underestimate the formation of the 310 helix and of the RT loop. Note also that the folding mechanism that follows from our analysis essentially agrees with that based on a standard Gō model (Borroguero et al. 2002) and on the implementation of ϕ-values as harmonic constraints (Lindorff-Larsen et al. 2004), although in the former, the RT loop looks less structured than in our simulations.

CI2 is usually taken as an example of a protein that folds in a nonhierarchical fashion, following the “nucleation-condensation” mechanism (Karplus and Weaver 1976). In agreement with the idea of Baldwin and Rose (1999), we show that even in the case of CI2, the folding process is hierarchic. The reason why experiments do not recognize the folding of CI2 as hierarchic is not so much that the LES are not stable as suggested in Baldwin and Rose (1999), but that they coincide only marginally with secondary structures that can be detected by typical experimental techniques. In fact, the first folding events are the stabilization of some (but not all) contacts in the α-helix and some contacts between the strands β4 and β5 and β4 and β6 on a nanoseconds time scale. The overall folding takes place when the contacts between strands β3 and β4, β2 and β5, and β1 and β6 get formed. These results agree with the experimental evidence that secondary and tertiary structures appear concurrently (Itzhaki et al. 1995), but this does not mean that the protein does not display early formed LES, which guide the folding process. It only means that they do not coincide with secondary structures. One can identify the LES as a region beyond the N-terminal of the helix and the region enclosed between strands β4 and β5. This picture is also in overall agreement with the simulations of Li and Shakhnovich (2001) and Clementi et al. (2000).

Note that the description of the folding given above implies a departure from the chronological sequence of events that one can observe (see Results section) to a causal sequence, where the formation of LES is needed to quickly reach the post-critical nucleus and eventually the native state. The first argument that supports this departure is that the formation of stable local contacts reduces the entropy of the chain, allowing for a faster search through the conformational space of the remaining contacts to form the post-critical folding nucleus. Moreover, if two structures that should assemble together already have their correct shape (i.e., have formed most if not all their internal contacts), once they find each other they can dock without further ado, allowing for a fast formation of the corresponding native contacts as opposed to potential time-wasting trapping configurations, configurations which lower both the energy and the entropy at once.

The unfolded state

An interesting result of the above simulations is that the unfolded state of the three proteins displays some degree of residual structure, corresponding to the local elementary structures that eventually guide the folding process. We are conscious that our description of the unfolded state is biased both because of the neglect of non-native interactions and because the interaction parameters are calculated in the crystallographic conformation. However, the above results agree with a number of direct and indirect evidences. In the case of Src-SH3, NMR studies indicate that the diverging turn is partially formed in the denatured state (Yi et al. 1998). Protein L, which is structurally similar to Protein G but has a markedly different sequence, displays in 2 M guanidinium a nonrandom behavior in the first hairpin (Yi et al. 2000). Combination of NMR and molecular dynamics simulations indicate that the unfolded state of CI2 displays some helical structure (Kazmirski et al. 2001).

Model calculation of the effect of mutations

The model allows us to calculate the effects of mutations on the free energy of the protein following different schemes. The best agreement with the experimental data is found for ΔΔG‡-N, the correlation coefficient of the three proteins ranging between 0.57 and 0.65, and the mean square deviation between 0.48 and 0.86 kcal/mol. On the contrary, the model estimates of ΔΔG‡-U are quite poor, the correlation coefficient being ≤0.2, and is as poor as the standard Gō model. At the basis of these results is the fact that Gō models in general, and the present modified Gō model in particular, are tailored to describe the interactions in proximity of the native conformation, that is, those interactions that build out the highest energy barrier of unfolding.

The free energy difference ΔΔGU-N can be calculated both from equilibrium simulations and as ΔΔGU-‡–ΔΔG‡-N. The latter provides slightly better results (the correlation coefficient ranging between 0.45 and 0.62 and a typical standard deviation of 0.85 kcal/mol), because it does not suffer from equilibration requirements. Anyway, the correlation coefficient between the ΔΔGU-N calculated with the two methods is ∼0.9, a result that indicates that the two-state picture of the folding process holds.

The prediction concerning the ϕ-values is rather poor, the correlation coefficients being between 0.48 and 0.15. This is a consequence of the conspicuous error propagation that is implicit in the definition of ϕ-values. Being a ratio (cf. Materials and Methods), the relative error ɛϕ associated with a ϕ-value is (ɛU−‡ 2 + ɛU-N2)1/2, where ɛU−‡ and ɛU-N are the relative errors that affect the numerator and the denominator, respectively. For example, as 0.85 kcal/mol is the typical error in the prediction of ΔΔGU-N , sites with ΔΔGU-N ≈1 kcal/mol will display an error larger than 100% on the ϕ-values. Particularly affected by this problem are those sites that build out native contacts already in the unfolded state. Since these sites belong to LES, the consequence for the description of the folding process is most important. On the other hand, mutations on these sites raise not only the free energy of the native and the transition state, but also that of the unfolded state, giving low values of ΔΔGU-N.

Conclusions

We have extended the standard Cα−Gō model so as to better account for the chemical diversity of the different types of amino acids forming a protein. In addition to calculating the effects of mutations (as ΔΔGU-N, ΔΔG‡-N, and ΔΔG‡-U) and comparing them with experiments, we can also investigate the details of the folding pathways which, as a rule, escape standard experimental techniques, but which strongly qualify the folding abilities of the protein. We observe that proteins G, Src-SH3, and CI2 fold through a sequence of events whose first step is the formation of LES. We think that this description complements well the common view of protein folding as a chemical reaction through a transition state.

Electronic supplementary material

In the Supplemental material, one can find the contact formation flows, as a function of time, for the native contacts of Protein G, Src-SH3, and CI2. These diagrams summarize the time development of the events that lead to the folding of each of the three proteins.

Materials and methods

We adopted an off-lattice model that simplifies the structure of the protein, picturing each amino acid as a hard sphere centered at the position of the Cα. The interaction between two residues is given by the contact potential defined in Equation 1. The attraction between native pairs can be thought of as a square-well potential of range R =7.5Å, whose depth is specific to the native contact considered and given by the matrix element Bij. The interaction between non-native pairs is repulsive for distances dij < R and zero for dij ≥ R. To avoid overlapping between residues of native pairs, we define a hard-core distance of 99% of their native distance. Moreover, we assume that residue i interacts with residue i +2 only through a hard-core repulsion of range 3.8Å, and that it does not interact with residue i +1, maintaining a fixed distance di,i+1 =3.8Å. A mutation is defined operatively as a switch of all the native contacts that the mutated residue makes to non-native ones.

Thermodynamical sampling has been performed by means of a Metropolis Monte Carlo algorithm. The kinetic calculations have been performed making use of a dynamic Metropolis algorithm, whose solution has been shown to be equivalent to the solution of the associated Langevin equations (Kikuchi et al. 1991). In order to have an approximated relation between the discrete step and the time measured in seconds, we made 10 independent simulations of protein Src-SH3, observing a linear correlation between the squared mean displacement of the center of mass and MC time. Comparing this coefficient with a typical diffusing coefficient for a globular protein, we obtained the relation 106 MC steps ≈ 1·10−7 sec. Note that the reduced degrees of freedom explicitly treated by the model may lead to a reduced viscosity and thus to a shorter scale of times than one would have obtained had one considered a full atom description of the heteropolymer.

We define operatively the native state for each protein as the set of conformations displaying qE >0.65 (qE >0.75 for the Src-SH3) and dRMSD < 5Å. As a consequence, the unfolded state is characterized by conformations displaying a pair (qE,dRMSD) outside of this interval. We have performed 200 simulations starting from the folded conformation recording the first transition time toward the unfolded state, obtaining the transition probability as a function of time PN→U(t). This curve is well fitted by an exponential whose characteristic time gives the inverse of the unfolding rate: τ = 1/ku. In the same way, the folding rate kf is obtained from the exponential fit of PU→N(t) resulting from 200 simulations starting from random generated conformations. These two sets of simulations are repeated for each mutation and for each protein. The temperatures of the samplings are fixed for each protein to T/Tf =0.94 for Protein G, T/Tf =1.1 for Src-SH3, and T/Tf =1.05 for CI2.

From the kinetic rates of folding and unfolding of the wild-type and mutated protein, we have calculated the differences of free energies between the transition and the unfolded state through ΔΔG‡-U = T log kfmut/kfwt and between the transition and the native state through ΔΔG‡-N = T log kumut/kuwt. The variations of free energy between native and unfolded state ΔΔGU-N are calculated in two different ways, i.e., from equilibrium simulations (20 simulations of 50 μsec per mutation per protein) through ΔΔGU-N(eq) = T log PUmut/PUwt–T log Pnmut/PNwt, where PN is the probability for the protein to be in the native state and PU = 1-PN, and from the kinetic rates through ΔΔGU-N(kin) = T log kumut/kuwt–T log kfmut/kfwt. The ϕ-values are calculated either from ϕ = −ΔΔG‡-U/ΔΔGU-N or from ϕ = 1−ΔΔG‡-N/ΔΔGU-N.

The PDB codes for the Protein G, Src-SH3, and CI2 used in the present study are, respectively, 1PGB, 1FMK, and 2CI2.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Guido Tiana, Department of Physics, via Celoria 16, 20133 Milano, Italy; e-mail: tiana@mi.infn.it; fax: 39-02-50317487.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.052056006.

References

- Abkevich V.I., Gutin A.M., Shakhnovich E.I. 1994. Specific nucleus as the transition state for protein folding. Biochemistry 33: 10026–10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander P., Fahnestock S., Lee T., Orban J., Bryan P. 1992. Thermodynamic analysis of the folding of the streptococcal Protein G IgG-binding domains B1 and B2. Biochememistry 31: 3597–3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R.L. and Rose G.D. 1999. Is protein folding hierarchic? Trends Biochem. Sci. 24: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J.C., van der Spoel D., van Drunen R. 1995. GROMACS: A message–passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91: 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco F.G., Rivas G., Serrano L. 1994. Folding of protein G B1 domain studied by conformational characterization of fragments comprising its secondary structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 230: 634–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroguero J.M., Dokholyan N.V., Buldryev S.V., Shakhnovich E.I., Stanley H.E. 2002. Thermodynamics and folding kinetics analysis of the SH3 domain from discrete molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Biol. 318: 863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broglia R.A. and Tiana G. 2001a. Hierarchy of events in the folding of model proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 114: 7267–7272. [Google Scholar]

- Broglia R.A. and Tiana G. 2001b. Reading the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence. Proteins 45: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broglia R.A., Tiana G., Provasi D. 2004. Simple model of protein folding and of non-conventional drug design. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16: R111–R144. [Google Scholar]

- Broglia R.A., Tiana G., Sutto L., Provasi D., Simona F. 2005. Design of HIV-1-PR inhibitors that do not create resistance: Blocking the folding of single monomers. Protein Sci. 14: 2668–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryngelson J.D. and Wolynes P.G. 1987. Spin glasses and the statistical mechanics of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84: 7524–7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi C., Nymeyer H., Onuchic J.N. 2000. Topological and energetic factors: What determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and en-route intermediates for protein folding? J. Mol. Biol. 298: 937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gō N. 1983. Theoretical studies of protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 12: 183–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantcharova V., Riddle D., Santiago J., Baker D. 1998. Important role of hydrogen bonds in the structurally polarized transition state for folding of the src SH3 domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5: 714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerois R., Nielsen J.E., Serrano L. 2002. Predicting changes in the stability of proteins and protein complexes: A study of more than 1000 mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 320: 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A., Jensen M.H., Sneppen K., Zocchi G. 1998. A hierarchical scheme for cooperativity and folding in proteins. Physica A (Amsterdam) 250: 335–351. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. 1996. VMD–Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14.1: 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki L.S., Otzen D.E., Fersht A.R. 1995. The structure of the transition state of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 analyzed by protein engineering methods: Evidence for a nucleation-condensation mechanism for protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 254: 260–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanicolas J. and Brooks C.L. 2002. The origins of asymmetry in the folding transition states of protein G and protein L. Protein Sci. 11: 2351–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus M. and Weaver D.L. 1976. Protein folding dynamics. Nature 260: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmirski S.L., Wong K.B., Freund S.M.V., Tan Y.J., Fersht A.R., Daggett V. 2001. Protein folding from a highly disordered denatured state: Folding pathway of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 at atomic resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 4349–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F., Chuang J.I., Gianni S., Fersht A.R. 2003. The kinetic pathway of folding of barnase. J. Mol. Biol. 333: 169–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K., Yoshida M., Maekawa T., Watanbe H. 1991. Metropolis Monte Carlo method as a numerical technique to solve Fokker-Planck equation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 185: 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis T. and Karplus M. 1999. Discrimination of the native from misfolded protein models with an energy function including implicit solvation. J. Mol. Biol. 288: 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesk A.M. and Rose G.D. 1981. Folding units in globular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 78: 4304–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy Y., Caflish A., Onuchic J.N., Wolynes P.G. 2004. The folding and dimerization of HIV-1-Protease: Evidence for a stable monomer from simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 340: 67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. and Shakhnovich E.I. 2001. Constructing, verifying and dissecting the folding transition state of CI2 with all atom simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 13014–13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindorff-Larsen K., Vendruscolo M., Paci E., Dobson C.M. 2004. Transition states for protein folding have native topologies despite high structural variability. Nat. Struct. Biol. 11: 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J.C., Pisabarro M.T., Serrano L. 1998. Obligatory steps in protein folding and the conformational diversity of the transition state. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5: 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matysiak S. and Clementi C. 2004. Optimal combination of theory and experiment for the characterization of the protein folding landscape of S6: How far can a minimalist model go? J. Mol. Biol. 343: 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallister E.L., Alm E., Baker D. 2000. Critical role of β-hairpin formation in Protein G folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuchic J.N. and Wolynes P.G. 2004. Theory of protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14: 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuchic J.N., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P.G. 1997. Theory of protein folding: The energy landscape perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 48: 545–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchenko A.R., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P.G. 1995. Foldons, protein structural modules, and exons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93: 2008–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.H., Ramachandra Shastry M.C., Roder H. 1999. Folding dynamics of the B1 domain of protein G explored by ultrarapid mixing. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 943–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman D.A., Case D.A., Caldwell J.W., Ross W.S., Cheatham T.E. III, DeBolt T., Ferguson D., Seibel G., Kollman P. 1995. AMBER, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules. Comp. Phys. Commun. 91: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ptitsyn O.B. and Rashin A.A. 1975. A model of myoglobin self-organization. Biophys. Chem. 3: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa T.L., Marhson J.S., Mayor U., Fremd S.M.V., Fersht A.R. 2005. Solution Structure of a protein denaturated state and folding intermediate. Nature 437: 1053–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle D., Grantcharova S.V.P., Santiago J.V., Alm E., Ruczinski I., Baker D. 1999. Experiment and theory highlight role of native state topology in SH3 folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 1016–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada J. and Shakhnovich E.I. 2002. The ensemble folding kinetics of protein G from an all-atom Monte Carlo simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 11175–11180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker A.S. and Wolynes P.G. 1999. Exploring structures in protein folding funnels with free energy functionals. J. Mol. Biol. 287: 657–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiana G. and Broglia R.A. 2001. Statistical analysis of contact formation in the folding of model proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 108: 2503–2510. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., Levitt M., Baker D. 1999. Hierarchy of structure loss in MD simulations of src SH3 domain unfolding. J. Mol. Biol. 291: 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Q., Bystroff C., Baker D. 1998. Prediction and structure characterization of an independently folding substructure in the src SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 283: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Q., Scalley-Kim M.L., Alm E.J., Bajer D. 2000. NMR characterization of residual structure in the denatured state of protein L. J. Mol. Biol. 299: 1341–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocchi G. 1997. Proteins unfold in steps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 10647–10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]