1. Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) continues to be one of the most prevalent healthcare problems in the United States. Despite the significant morbidity, loss of productivity, and healthcare costs associated with CRS, the underlying processes that lead to disease remain poorly understood. The non-specific clinical symptoms of nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, facial pain, and anosmia may represent a common endpoint for various inflammatory mechanisms occurring in different anatomic areas. CRS is increasingly being appreciated as a clinical syndrome with a wide spectrum of overlapping disease physiology. For instance, CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) often is characterized by eosinophilic inflammation and increased production of histamine, IL-5 and IL-13,1 whereas CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) is often considered a predominantly neutrophilic disease characterized by high levels of IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα.2 In practice, however, there are CRSsNP patients with high levels of eosinophils and CRSwNP patients that exhibit robust neutrophilic infiltration within the sinonasal epithelium. Thus our classification of CRS in clinical practice is often not as simple as we would prefer.

I. CRS Pathophysiology and Immune homeostasis

CRS is characterized by persistent inflammation, a dysregulated immune response, and host-microbial interactions that together result in disruption of epithelial barrier function, poor wound healing, tissue remodeling, and clinical symptoms. Historically the significance of bacteria in acute and chronic rhinosinusitis has focused on the interactions between a single bacterial pathogen and its host. However, developing concepts in microbial ecology, laboratory methods in culture-independent microbiology, and bioinformatics, are furthering our capacity to study complex microbial communities as an entire functional unit. The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are the first tissues exposed to airborne environmental challenges, including pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria, viruses, fungi, allergens and toxins. The mucosal surface utilizes several immune mechanisms to promote homeostasis, which can broadly be divided into innate and adaptive immunity. Many host factors impact the functionality of the immune response that is thought to predispose individuals to the development of CRS.3

Innate vs. adaptive immunity

Innate immunity classically refers to the non-specific defense mechanisms that are rapidly activated following exposure to antigenic material and confer immediate protection. Within the upper respiratory tract, this includes the physical barrier provided by the ciliated pseudostratified columnar respiratory epithelium that lines the sinonasal cavity. This resilient barrier contains interspersed goblet cells that secrete a viscoelastic mucus layer atop the epithelial surface composed of high molecular weight glycoprotein mucins and heavily glycosylated molecules. In conjunction with beating cilia, the enriched mucus layer promotes non-specific mucociliary clearance of microbes and irritant particles.4 Barrier dysfunction can contribute to CRS, and when coupled with defects in mucociliary clearance that promote bacterial colonization, bacterial invasion and further barrier disruption may occur.3,5 Classic genetic defects in ciliary function, such as cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia, are often used as examples but acquired ciliary dysfunction occurs in CRS as well.6 Poor barrier function and dysfunctional mucociliary clearance are host defects that to predispose individuals to pathogen colonization and the development of recurrent infection.7–9

Sinonasal epithelial cells secrete enzymes, opsonins, defensins, permeabolizing proteins and other endogenous antimicrobial products into the apical mucus layer. These host defense molecules are important for directly neutralizing microbes and recruiting inflammatory cells that modulate the immune response. Specifically, epithelial cells secrete enzymes such as lysozyme, peroxidases, and chitinases, the small cationic permeabolizing proteins such as the defensins and cathelicidins. Additionally, proteins such as lactoferrin, mucins, C-reactive protein and secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI), collectively provide protection from bacteria, fungi, and viruses at the apical surface.9,10,11

When pathogens do invade the sinonasal epithelium, circulating professional phagocytes, possessing pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on their cell surface, recognize pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). When host epithelial cell PRRs bind pathogenic or damaged cell proteins, the acute inflammatory pathways are activated and the tissue becomes primed for the adaptive immune response.12,10 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a subset of PRRs that allow phagocytes to recognize bacterial motifs such as lipopolysacharide (via TLR-4) and CpG repeats (via TLR-9) associated with Gram-negative bacteria and bacterial DNA respectively.

Current literature suggests that variable gene expression of TLRs and other cytokines may predispose some individuals to develop CRS.13 For example, patients with CRS demonstrate variable expression of TLR2 mRNA.14,15 TLR2 is expressed on sinonasal epithelial cells and recognizes several bacterial, fungal, and viral proteins. Binding of a ligand to TLR2 activates the acute inflammatory response and also primes the adaptive immune response by increasing expression of MHC-II co-stimulatory molecules required to present antigens to T-follicular helper cells. The resulting Th1 response is necessary for clearance of S. pneumonia infection, for example.16,17 Another study identified decreased TLR9 mRNA expression in CRSsNP;18 however, in depth study of TLR-mediated disease in CRS is lacking.

In concert with the acute inflammatory response, cytotoxic natural killer (NK) cells are important to mounting an appropriate innate immune response. While NK cells are often understood to induce apoptosis in viral infected cells and tumor cells, they are becoming increasingly of interest in CRS. Patients with CRS have dysfunctional NK cells that demonstrate impaired degranulation and diminished release of TNFα and IFNγ.19

The adaptive immune system is stimulated when PMNs and macrophages are recruited to the site of infection to fully eradicate bacterial infection and establish long-lasting cell-mediated immunity.20 Antigen presenting cells such as monocytes, macrophages, B-lymphocytes and dendritic cells process complex protein antigens and present antigenic peptides on their surface that are then presented to T helper cells on the appropriate MHC. Binding of the antigen-MHC complex to the T-cell receptor activates the adaptive immune system and leads to longer lasting T-effector cells and antibody producing plasma cells.21

While much attention is given to defective innate immunity in the development of CRS, the adaptive immune system is crucial for developing an appropriate T-cell response, and much of the CRS literature supports polarized populations of T-follicular helper cells (either Th1 or Th2) in subsets of CRS. Th1 cells produce IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα, which ultimately lead to a robust cell-mediated response and phagocyte-mediated inflammation. Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 that promote a strong antibody response and the accumulation of eosinophils while inhibiting the phagocytes and the resulting potent inflammatory response.22 Furthermore, the T-follicular helper cell environment influences macrophage differentiation into M1 macrophages that are necessary for a mounting a vigorous inflammatory response against intracellular pathogens, or M2 macrophages that are associated with eosinophilic states.23 M2 macrophages are predominant in CRSwNP and may play a role in exacerbating polyposis because they are unable to phagocytose S. aureus.24 The inappropriate persistence of Th1 inflammation in CRSsNP and the ongoing recruitment of eosinophils and Th2 cells in CRSwNP are hallmarks of adaptive immune dysfunction characteristic in CRS.

Surface mucosal niche

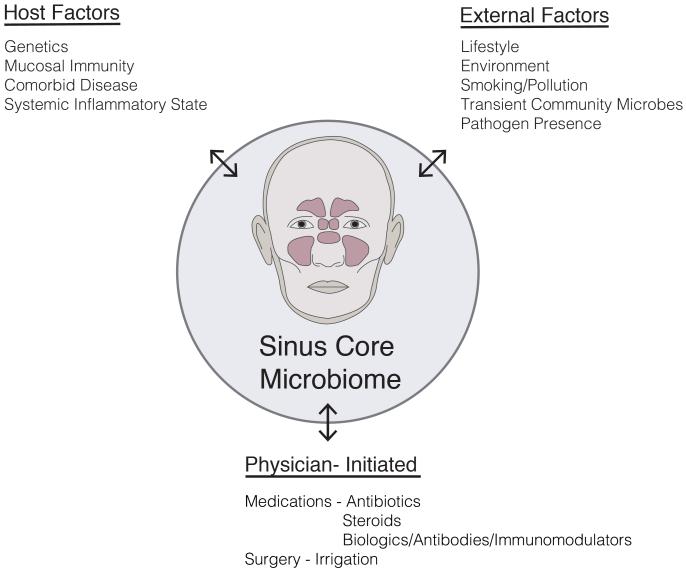

Once thought to be a “sterile” environment in the healthy state, the paranasal sinuses are now widely appreciated to harbor rich and diverse populations of commensal bacteria. Commensals are most often defined as the community of microorganisms that colonize epithelial surfaces without causing harm to the host. Our understanding of “commensal” bacteria is evolving to recognize the shifting selective pressures in the microbial community that likely include other forms of symbiosis between host cells and neighboring bacteria including parasitism, mutualism and amensalism. Host defense mechanisms contribute to a unique mucosal environment that constantly applies selective pressure on epithelial microbes resulting in a “surface mucosal niche.” This niche varies between individuals and between different anatomic compartments.25, 26 There may be drivers of this niche beyond host mucosal immune function, including environmental exposures (eg, smoking) or medication usage (eg, antibiotics) [Figure 1]. Bacteria, either live or their by-products such as DNA, quorum-sensing molecules, or metabolized waste, interact with the immune system and can influence inflammatory processes.

Figure 1.

Potential factors influencing the sinus microbiome.

Data from Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, et al. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007;449(7164):804–10.

II. Role of bacteria in initiation and sustenance of inflammation

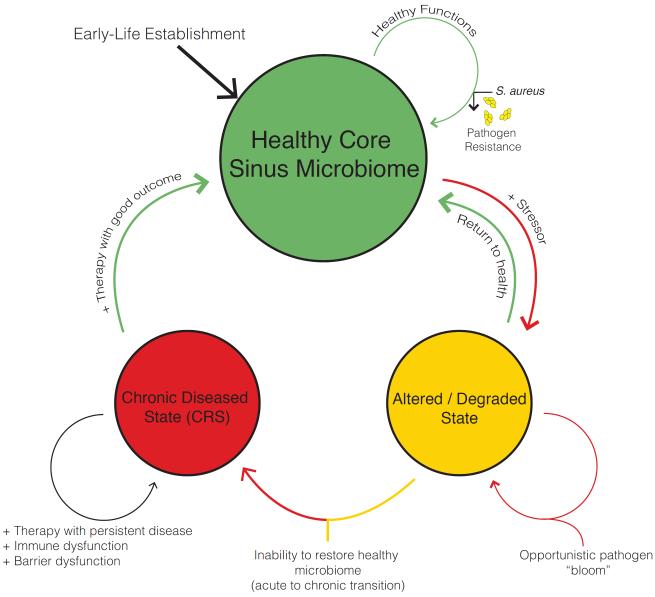

Historically, many described CRS as a disease that resulted from a persistent or incompletely treated acute infection. Current understanding is that CRS is an inflammatory process rather than infectious, but that inflammatory mechanisms modulated by commensal and pathogenic bacteria contribute to disease formation, beyond the simplistic notion of a single microbial pathogen interacting with a host and causing disease. Certainly, chronic inflammatory diseases can result from direct bacterial invasion at mucosal surfaces, resulting in compromised barrier function, a coordinated innate and adaptive immune response, and an acute inflammatory response which may evolve into prolonged inflammation leading to tissue damage, remodeling and fibrosis.27 It is possible that in some patients, bacterial infection initiates the inflammatory process that never resolves; yet, in others it may be the case that a non-infectious inciting event initiates an inflammatory response that alters the native mucosal surface bacterial niche, which then propagates the disease once the original disease-causing event has concluded [Figure 2].28 Earlier studies of sinonasal microbiota utilized culture-based microbiology techniques, which have recently been usurped by nucleic acid-based molecular techniques that allow for more sensitive and less biased detection of microbes, as well as the ability to characterize entire communities of microbes within the same sample.29, 30 Without evidence to support a definitive role for bacterial “infection” as the etiology for CRS, future studies are needed to better understand the role of bacteria in host susceptibility to disease development.

Figure 2.

Significant perturbations of the healthy microbiome state can result in a degraded state that is susceptible to disease. Once degraded and/or diseased, a goal may be to restore the rich and diverse healthy state.

Data from Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012;489(7415):220–30.

2. The Paranasal Sinus Biome in Health and Disease

I. The microbiome

Host-microbe interactions are an established contributing factor in the formation of CRS, but evidence for the presence or absence of a single microbe resulting in disease is lacking. The shifting paradigm focuses on the unique composition of the entire bacterial community that colonizes the sinonasal mucosa also known as the microbiome. The microbiome is a potentially diverse community of microbiota existing in a delicate symbiotic relationship within a human microenvironment. These organisms possess great genetic potential to act as disease modifiers and contribute to the maintenance of health and formation of disease on all epithelial surfaces including upper and lower airway.31, 32, 33 In intestinal epithelia, early microbial colonization is essential for normal immunologic development and influences susceptibility to inflammatory and allergic diseases later in life.34 In neonates, for example, early lower airway colonization with pathogens such as S. pneumonia, H. influenza, and M. catarrhalis increases the risk of recurrent wheezing and asthma.35 Additionally, several groups have demonstrated the importance of the microbiome on host adaptive immune system through modulation of dendritic cells, Th17 and T-reg cells.36, 37, 38,39 Although much of bacterial microbiome research is still emerging, it is one of the most intriguing current topics of CRS research.

There remains a paucity of microbiome research on fungi, viruses, and bacteriophages in CRS, although growing evidence suggests that these microbes may contribute to a larger “metaorganism” in which interactions between and among all microbes and their host shape human health. Early efforts to describe microbial roles in CRS resulted in the “fungal hypothesis” which suggested that CRS resulted from an overexuberant host response to Alternaria fungi.40 While this theory does not explain many of the defects observed in CRS, and current guidelines recommend against antifungal therapy for CRS patients, there is continued research interest in the fungal microbiome.41 Recent studies using sequencing of the fungal 18S ribosomal RNA gene demonstrate a rich and diverse population of commensal fungal taxa in middle meatal lavages from healthy and CRS patients. Patients with CRS were found to have quantitative increases in the total amount of fungal 18S ribosomal RNA when compared to controls.42 A 2014 prospective study by Cleland et al. identified 207 unique fungal genera in 23 CRS patients and 11 controls. Interestingly, fungal genera traditionally associated with CRS such as Alternaria and Aspergillus were found in very low abundance. This study also assessed post-operative changes in the fungal microbiome and found decreased richness at 6 and 12 weeks after surgery.43 No studies to date have thoroughly profiled viral or bacteriophage populations within the paranasal sinuses, although there is certainly interest. For instance, recent evidence suggests that upper airway rhinovirus infection can alter the nasopharyngeal microbiome.44 Further studies directed at characterizing the entire microbiome population in health are necessary in order to develop a more robust understanding of the role microbial diversity plays in sinonasal health as well as the generation of disease.

II. Bacteria in health

Since the advent of culture-independent molecular techniques, several groups have used various techniques to characterize the sinonasal bacterial community in healthy individuals. Efforts to identify a distinct microbial profile in health are inconclusive, and there is currently no consensus on which bacteria predominate in or define the healthy state. Although several studies have characterized the bacterial communities in the upper airway, cross-study comparisons are difficult due to several variations in sampling methods, bacterial primer selection, sequencing methods, and data analysis pipelines.45 Even so, there are several patterns that frequently emerge. These include an abundance of Propionibacterium acnes, S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and Corynebacterium spp in health.46, 47, 26, 33 Of note, Staphylococcus spp. including S. aureus and coagulase negative Staphylococci are present in healthy subjects, and can behave in either pathogenic or commensal fashion based on particular strain, bacterial gene expression, and surrounding microbial interactions. While native bacteria act to promote homeostasis within the sinonasal epithelia, disruption of this balance known as dysbiosis may allow commensal organisms to act as opportunistic pathogens in disease states.48

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) consortium compiled 16S rRNA gene sequences collected from 18 different sites across the body in order to better associate the microbiome with human health.49,50 Further analysis of the HMP data demonstrates that different human subjects possess unique native bacterial communities with highly variable taxonomic composition at the same body sites. These bacterial community profiles strongly associated with life-history characteristics such as history of being breastfed as an infant, gender, and level of education. Interestingly, despite profound inter- and intra-person variability in the bacterial microbiome, community function remains constant and the community types from one body site is predictive of community types at other body sites within the same individual.50,51 The association of bacterial community composition with life history factors such as presence or absence of breastfeeding raises questions about the source of commensal microbes. In the gastrointestinal literature, there are several studies that demonstrate that diet shapes the microbiome composition, and different microbial profiles are associated with diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).52 In addition to dietary factors, the upper airway microbiota are a known source of microbes that colonize the lung and stomach.53 Ultimately, the aggregate of bacterial taxa in the sinus niche need to be better studied at a “metagenome” level to begin deciphering community function, and how specific bacterial ecosystems are established.

III. Microbiome changes in disease

Several statistical indices are use to describe species diversity within a microbial community. Alpha diversity is the intra-community diversity as measured by the total number and composition of species. Beta diversity is an estimate of the diversity (number and composition) comparison between different habitats. Abundance refers to the total amount of bacterial DNA that corresponds to specific bacterial taxa found within a sample. Richness describes the total number of species identified within a sample, i.e. greater numbers of distinct species means higher richness. Evenness is a measure of how similar in number each species within a bacterial community is. Several studies have identified perturbations in the microbiome during CRS. In general, S. aureus and anaerobes including Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides spp. and Peptostreptococcus spp. are consistently more abundant in CRS versus healthy controls.26,41,46,47,54 Interestingly, although the abundance of pathogenic bacteria is increased in CRS patients, the overall total quantity of bacteria does not seem to change compared with healthy individuals. This indicates that the sinus niche is filled by a given amount of bacteria, and a relative dominance of the niche by pathogens is associated with disease. In these studies, despite having a similar overall bacterial burden, microbial richness, evenness and diversity of bacterial colonies was greatly diminished in CRS.26,33,54 This observation supports the hypothesis that disturbances in the microbial community are a part of CRS. Just as ecologists associate the macroscopic biodiversity and biomass of rainforests and coral reef habitats with the overall health of the ecosystem, the microscopic biodiversity of bacteria within a host mucosal niche is considered a hallmark of health.

The frequent observation that CRS is associated with decreased microbial diversity parallels many other disease states. For example, decreased diversity in the gut microbiome is associated with obesity, active inflammatory bowel disease and psoriatic arthritis.55–57 Although we lack data to suggest that promoting bacterial diversity within the sinonasal niche would prevent or improve CRS, this may be a relevant consideration moving forward since the mainstays of CRS therapy are long-term broad spectrum antibiotics and corticosteroids which carry the potential to alter the microbiome composition.58,59

IV. Are microbiome alterations a cause or by-product of disease?

Recent cross-sectional population studies have detected differences in the microbiome between CRS patients and healthy individuals, but what does this really mean? One possibility is that community alterations in the microbiome lead to epithelial barrier and immune dysfunction resulting in disease. Alternatively, persistent inflammation at the mucosal surface may result in a prolonged immune response, and/or alterations in the local microenvironment that shift the microbial community. Moreover, therapies administered for the disease (e.g., antibiotic therapy and steroids) likely impact the microbiome and may confound these observations. The multitude of variables present that impact the mucosal niche makes establishing this causation difficult in the absence of animal models. In reality, any or all of these possibilities may occur [Figure 1].

The concept of perturbations in the microbial community resulting in disease, i.e. dysbiosis, has been explored in the gastrointestinal tract. The normal gut flora play an essential role in maintaining immune homeostasis and disruptions in these mutualistic relationships are believed to lead to several conditions ranging from antibiotic-associated diarrhea and inflammatory bowel disease to necrotizing enterocolitis and colorectal cancer.48 While we know that CRS is associated with shifts in the bacterial microbiome it remains unclear if this is an inciting factor in the development or propagation of disease or merely a consequence. Emerging data from cross-sectional analysis of specific patient populations suggests that host factors, such as a history of tobacco use, presence of asthma, or recent antibiotic use can impact the microbiota.30,46,60

Given the panoply of disease mechanisms involved, the prolonged utilization of medical therapies, and the lack of a universal mouse model for the disease, human studies of CRS will require large-scale, multilevel, longitudinal design in order to delineate patterns of microbial perturbations and their significance. Such studies are critical to determining the role of the microbiome in disease formation, chronicity, severity and prognosis, and response to therapies.

3. Clinical implications and treatment considerations of bacterial pathogens

I. Pathogens often implicated in CRS

Traditional culture-based study vs. molecular techniques

Many culture-based studies of sinus specimens from CRS patients identify the most common pathogens associated with CRS as S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and with specialized culture techniques, several species of anaerobes.61–64 The bacterial pathogens implicated in CRS are distinct from those most often identified in acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS). Just as CRS is thought to be multifactorial, incidence of ABRS may be higher in the setting of particular environmental exposures, allergies, smoking, ciliary impairment, sinonasal anatomic variations, and transient bacterial infections.65–67 However, the most often identified bacteria cultured in patients with ABRS are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. pyrogenes, M. catarrhalis, and S aureus.68

Patients with refractory CRS often demonstrate both cellular and humoral immune dysfunction, as described above,69 and in these cases the most commonly isolated pathogens are S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.63,64 Patients with CRS have a higher incidence of antibiotic-resistance; this observation is especially notable in patients undergoing revision endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) when compared to patients undergoing surgery for the first time. 70 True (ie, physiologic) antibiotic resistance in a dysbiotic community is difficult to assess, but may be even higher than that documented in culture studies of antibiotic susceptibility.71

In the wake of emerging molecular and imaging techniques, several groups have interrogated the functional role of biofilms in CRS.72,73,74 As the field embraces molecular identification techniques, it has become apparent that conventional culture methods are not on par with newer culture-independent techniques. Current data suggest that molecular techniques such as 16S gene sequencing demonstrate greater biodiversity, increased sensitivity, and the ability to identify anaerobic groups with greater specificity when compared to culture.46,47 In practice, Hauser et al. found clinical lab cultures to identify the dominant bacteria only 60% of the time.75 Presumably, identification of the dominant bacteria is the information sought by the clinician, as dysbiosis and decreased diversity in disease points to a single or few dominant organisms out of community balance as the source of pathology. Culture-directed antibiotics are thought to be beneficial if there are signs of active infection such as purulence, or if many antibiotics have already been administered, but the role of cultures is less clear in the absence of this history. As our understanding of CRS etiology evolves, and our capacity to examine the entire microbial community increases, the utility of cultures in CRS requires further evaluation.

II. S. aureus and superantigens

Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative staphylococcus are the most common putative pathogens identified in CRS in North America.68,76 Toxigenic strains of S. aureus are known to be potent disease modifiers capable of disrupting barrier function, invading epithelial cells, modulating immune cells, and promoting polyp formation.77 Staphylococcal superantigenic toxins (SAgs) are small molecules secreted during toxigenic S. aureus infection that crosslink antigen presenting cells and T-cells by simultaneously binding MHC-II and the T-cell receptor. In contrast to conventional antigens, this direct activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells leads to a profound polyclonal immune response, and generation of a Th2 cytokine environment. This promotes eosinophil recruitment, the generation of polyclonal IgE, Treg inhibition, mast cell degranulation, and the activation of M2 macrophages, which collectively result in generation of nasal polyps.78–80

The incidence and awareness of methicillin-resistant S. aereus (MRSA) carriage in the anterior nares has increased in recent time and is known to contribute to surgical site infection and biofilm creation, slow mucosal healing after endoscopic sinus surgery, and result in greater overall morbidity.72 Although S. aureus is a major pathogen inCRS, most species remain methicillin-sensitive (MSSA). 81, 82, 46 Since the colonization of healthy individuals with toxigenic strains of Staphylococcus is surprisingly common, multiple host and microenvironment factors likely contribute to Staphylococcus-implicated effects in CRS.

S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, H. influenza, S. pneumonia, M. catarrhalis and Stenotrophomonas are known to establish biofilms on the mucosal surface. S. aureus biofilms in particular have been suggested to promote Th2 cytokines independently of SAgs.83 Biofilm formation with any pathogen occurs in response to selective pressures within the mucosal niche, including antibiotic use, tobacco exposure, and loss of integrity of host epithelial immune barrier. The presence of biofilms is associated with increased disease severity and recalcitrance since antibiotics and host defenses do not efficiently penetrate the dense, 3-dimensional, polysaccharide matrix. Once biofilms are established they are difficult to clear, and serve as a protected reservoir for pathogens to evolve virulence factors and shed planktonic bacteria that can incite acute exacerbations of disease.84

III. P. aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the paranasal sinuses is most frequently discovered in immune compromised individuals, patients undergoing revision sinus surgery, or in the setting of ciliary dysfunction such as in cystic fibrosis.85, 86, 87 P. aeruginosa secretes several virulence factors including adhesins, secreted toxins (eg. exoenzyme S and exotoxin A), proteases, effector proteins (eg. elastase and alkaline protease), and pigments (eg. pyocyanin) which act to evade the immune system and disable host cells. Additionally, P. aeruginosa uses active quorum sensing to organize tenacious biofilms at the epithelial surface and further evade host defenses.88

IV. Anaerobes

Although advances in molecular sequencing have highlighted the preponderance of anaerobes in the CRS microbiome, in clinical practice, the identification of specific anaerobes is often complicated by limitations of culture techniques. The expansion of anaerobes in subsets of CRS may also result from alterations in the microbial community and local microenvironment.89 30, 90,91 Currently, anaerobes pose several challenges to the effective management of CRS. When identified by culture, this often influences antibiotic selection to include anaerobe coverage. In the case of anaerobes such as Bacteriodetes and Fusobacteria, these pathogens are known to share mobile genetic elements that confer antibiotic resistance and increased virulence with other bacteria in the community.92,93 Thus, these anaerobes, when expanded in CRS, may work synergistically with other opportunistic pathogens throughout a bacterial community leading to a pathogenic niche.

V. Antibiotic resistance associated with pathogens in CRS study

Antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon and is increasingly common in patients with refractory CRS.70 Bacteria may acquire antibiotic resistance through random mutation or through exchange of genetic material. As discussed previously, the sinonasal bacterial niche experiences constant selective pressure from neighboring microbes and the host immune defenses. When this bacterial community proliferates in the presence of antibiotics there is additional selective pressure that culls species with the defense mechanisms to withstand antimicrobials in the environment. There are several mobile genetic elements or “r genes” that confer resistance to particular antibiotics and may be passed vertically through generations of bacteria, or horizontally from one bacterium to a neighboring bacterium.94 Since antibiotics used to treat refractory CRS selectively eliminate the most susceptible members of the community, the potential of the microbiome to remain diverse and facilitate pathogen exclusion is reduced, theoretically allowing resistant bacteria to flourish and dominate. Innovative new strategies are needed to combat the rise of resistant superinfections in refractory CRS; perhaps an approach that includes promoting a diverse and healthy microbial community to exclude multi-resistant pathogens will be explored in the future.

4. Emerging research concepts in the microbiome

I. Role in mucosal immune function

While progress has been made to characterize the bacterial microbiome in health and disease, studies of host-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions occurring within the mucosal niche have only begun. The concept of “pathogen exclusion” refers to the ability of a microbial community to selectively inhibit the dominance of a single pathogen. This can occur actively through direct inhibition of pathogens by commensals within the niche. For example, S. aureus may be inhibited by neighboring microbes including S. epidermidis, Corynebacterium spp., P. aeruginosa, and fungal species.25,95 While the host innate immune defense utilizes several antimicrobial strategies to modulate surface microbes, the bacterial community itself possesses a much more dynamic capacity to shape microbes within the niche through the use of small molecule signals (quorum sensing), utilization of alternative nutrient sources, secreted antimicrobials, and transfer of mobile genetic elements over many generations. Expansion of pathogens may also be limited by passive mechanisms such as competition for limited nutrients and the accumulation of metabolic waste products from indigenous microbes that inhibit pathogenic strains. For example, in the mouse intestine, enterohemorrhagic strains of E. coli (EHEC) are known to compete with non-pathogenic strains for amino acids and other nutrients.96,97

II. Dysbiosis and community dynamics

Dysbiosis is the concept that disruption of mutualistic relationships in the microbiome may compromise health and contribute to human disease. If the healthy microbiome exists to serve a function or multiple functions, exogenous stressors that induce a dysbiosis may then influence the functional ability of the core microbiome, creating a temporary susceptibility for transitioning to a diseased state [Figure 2]. It remains unclear whether dysbiosis is a primary trigger that leads to disease pathogenesis and if these community imbalances may be involved in determining severity or duration of disease.48 But, this is certainly an area of interest, as stability and resilience of the microbiome has a degree of interpersonal variance.50,98

III. Determinants of the human microbiome

The microbiome appears to be established early in infancy and is necessary for the development of normal mucosal immunity. Several gestational and post-partum environmental factors are known to contribute to the development of a healthy intestinal microbiome including route of birth, gestational age at birth, breastfeeding, exposure to cigarette smoke or antibiotics, household milieu, and socioeconomic status.99 In addition to environmental factors, there is intriguing evidence from twin studies to suggest that microbiome determinants are heritable but that genetics may play only a partial role in microbiome composition. These studies demonstrate that individuals have significant co-variability in the species represented within their gut microbiome, but that specific alleles held between monozygotic and dizygotic twins underlie the heritability of certain bacterial phyla.55,100

Stability refers to the degree of random change with time, and the resilience of a microbial community is defined by its ability to return to baseline following a perturbation in the community. Studies examining the stability and resilience of the sinonasal microbiome are limited, but emerging evidence suggests that the healthy adult microbiome is relatively stable over time.25 Hauser et al. determined that patients undergoing ESS and receiving post-operative oral antibiotics demonstrated significant shift in the microbial composition two weeks post-operatively, but that after six weeks, the bacterial composition returned to the pre-intervention baseline in many subjects.98 The significance of stability and resilience of the sinonasal microbiome is unclear at this point but may be identified as an important factor in disease susceptibility or response to therapy. For instance, we often hear the clinical scenario of a patient with an upper respiratory infection that subsequently develops sinus disease. If the native microbiota are not a stable and resilient population to begin with, then this perturbation could lead to prolonged shifts in the microbiome that then predispose to the formation of sinus disease, akin to the “two-hit” hypothesis of carcinogenesis.101

IV. Restoring a healthy microbiome – Prebiotics and Probiotics

With increasing evidence suggesting that dysbiosis participates in the onset or propagation of CRS, and data supporting the concept that microbial richness and diversity contribute to health, much interest has been devoted toward restoration of healthy microbial community function. The most obvious example of these efforts is with the use of probiotics and prebiotics. Probiotics are live bacteria or yeast that are introduced to a microbial community actively functioning to restore balance and/or functionality to the niche. While significant research has been devoted to oral probiotics for the restoration of gastrointestinal microbes, similar trials investigating oral or topical probiotics in CRS are lacking. To date there has been one randomized controlled trial examining the utility of probiotics in CRS, which did not find any benefit.102 Murine models have demonstrated proof-of-concept for the utility of introducing competing bacteria into the sinonasal milieu of infectious CRS using S. epidermidis as a “probiotic” niche-occupier in S.aureus-induced CRS in mice.103 Prebiotics are non-nutritive fibers that, when delivered into a bacterial community, serve as substrates for bacteria and are thought to support the growth of desirable microbes within the community. The uses of prebiotics for nasal health are widely marketed by “nutraceutical” companies. However, there have not been any randomized controlled data that supports the use of prebiotics in the treatment of CRS.

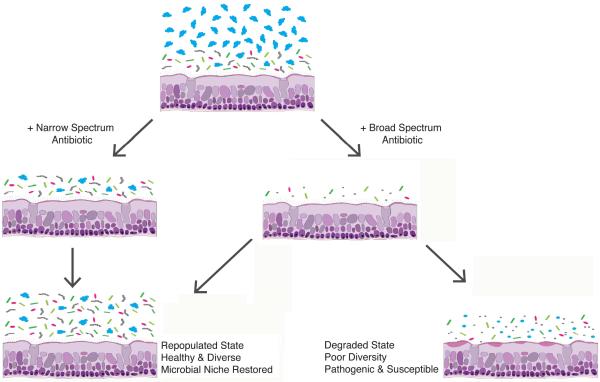

Lastly, many of our antibiotics carry broad-spectrum activity and eradicate many species in addition to the target pathogen (i.e., collateral damage), which may actually be unfavorable [Figure 3]. The development of narrow-spectrum antibiotics to selectively eliminate individual taxa from a microbial niche is appealing. In order to rationally move probiotics, prebiotics, and narrow-specrum antibiotics into the rhinology clinic, we must develop a detailed description of the “core microbiome,” or the core microbial components necessary for an individual to maintain sinonasal health. Restoring community function in the healthy state is a primary microbiome goal, just as restoring mucociliary function has been a functional goal in the management of CRS.6

Figure 3.

Antibiotic use, coupled with subject-specific resilience, may potentially result in a degraded microbiome.

5. A general approach to antibiotic therapy for refractory CRS

I. Current guidelines for antibiotics in CRS

Although sinonasal saline irrigation and topical corticosteroids are the mainstays of medical therapy for CRS, current clinical practice guidelines do recommend the routine use of antibiotics.104, 105 If purulence is present on examination in a CRS patient, short-term culture directed therapy has been recommended.106, 107, 108 In CRSwNP patients that experience an acute exacerbation or persistent symptoms of CRS, a short course of systemic corticosteroid therapy remains the standard of care with the best early and long-term improvement in polyp scores,109 although doxycycline may have a role in the patients as well110 Current clinical practice guidelines recommend consideration of long-term macrolide therapy such as clarithromycin 250–500mg daily, roxithromycin 150mg daily, or azithromycin 500mg weekly for 3 months in patients with CRSsNP only, as patients with nasal polyps did not benefit from long-term macrolide therapy when compared with placebo.111, 112, 104 The routine use of antibiotics in CRS when acute infection is not present has been recently called into question, given the cost and potential harms of antibiotic use when the effectiveness of this therapy is not clear.113

II. Bacteria: good, bad, or just there?

Increasing data suggest that diverse bacterial communities are important for maintaining human health, although much of our current CRS therapy is non-specific and potentially eradicates large groups of both commensal and pathogenic bacteria. Recent culture-independent study has demonstrated that bacteria are present in roughly similar quantities in both healthy and diseased states.29 Certainly, it is apparent that bacteria may function in a beneficial or detrimental manner to the host. However, it appears that much of the bacteria present are simply there, without a known role or function. It has also been noted that pathogens may be present in the healthy state, although in low abundance and housed within a richer and diverse population of other microbes.26 At this point in time it is challenging to determine if bacteria detected in disease always necessitates a therapeutic strategy for its eradication. Differences in microbial communities identified in recent CRS studies very well may be associations discovered due to confounding factors such as the extensive and prolonged therapies used for the disease, namely antibiotics. As a result, a more rational approach to judicious use of antibiotic therapy is needed in CRS.

Synopsis.

Bacterial pathogens and microbiome alterations can contribute to the initiation and propagation of mucosal inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). In this article, we review the clinical and research implications of key pathogens, discuss the role of the microbiome, and connect bacteria to mechanisms of mucosal immunity relevant in CRS.

Key Points.

The sinuses are not sterile. A population of bacteria are present in both health and disease, roughly in the same overall abundance, but qualitatively different in its makeup.

As of yet, no single bacterial species or set of species has been definitively shown to be protective or causative in CRS.

The overall function of the bacterial community may be most important, rather than the presence of absence of a single pathogen.

Therapies used to treat CRS may induce microbiome alterations.

Further research is indicated and required in this exciting field.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K23DC014747 (V.R.R.) and T32DC01228003 (T.W.V). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bachert C, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Johansson SG, van Cauwenberge P. Total and specific IgE in nasal polyps is related to local eosinophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(4):607–614. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112374. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.112374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawankar R, Nonaka M. Inflammatory mechanisms and remodeling in chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7(3):202–208. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kern RC, Conley DB, Walsh W, et al. Perspectives on the etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis: an immune barrier hypothesis. am j rhinol. 2008;22(6):549–559. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3228. doi:10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(5):571–577. doi: 10.1172/JCI15217. doi:10.1172/JCI15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters AT, Kato A, Zhang N, et al. Evidence for altered activity of the IL-6 pathway in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):397–403.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.072. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gudis D, Zhao K-Q, Cohen NA. Acquired cilia dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis. am j rhinol allergy. 2012;26(1):1–6. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3716. doi:10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadfield PJ, Rowe-Jones JM, Mackay IS. The prevalence of nasal polyps in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25(1):19–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush A, Chodhari R, Collins N, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: current state of the art. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(12):1136–1140. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.096958. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.096958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ooi EH, Psaltis AJ, Witterick IJ, Wormald P-J. Innate immunity. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2010;43(3):473–87. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.020. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claeys S, De Belder T, Holtappels G, et al. Human beta-defensins and toll-like receptors in the upper airway. Allergy. 2003;58(8):748–753. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramanathan M, Lee W-K, Spannhake EW, Lane AP. Th2 cytokines associated with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps down-regulate the antimicrobial immune function of human sinonasal epithelial cells. am j rhinol. 2008;22(2):115–121. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3136. doi:10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandermeer J, Sha Q, Lane AP, Schleimer RP. Innate immunity of the sinonasal cavity: expression of messenger RNA for complement cascade components and toll-like receptors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(12):1374–1380. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.12.1374. doi:10.1001/archotol.130.12.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato A, Schleimer RP. Beyond inflammation: airway epithelial cells are at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(6):711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Z, Yang Z, Wang C. Expression of TLR2 and TLR4 messenger RNA in the epithelial cells of the nasal airway. am j rhinol. 2005;19(3):236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detwiller KY, Smith TL, Alt JA, Trune DR, Mace JC, Sautter NB. Differential expression of innate immunity genes in chronic rhinosinusitis. am j rhinol allergy. 2014;28(5):374–377. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4082. doi:10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertz CJ, Kiertscher SM, Godowski PJ, et al. Microbial lipopeptides stimulate dendritic cell maturation via Toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2001;166(4):2444–2450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2444. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramanathan M, Lee W-K, Dubin MG, Lin S, Spannhake EW, Lane AP. Sinonasal epithelial cell expression of toll-like receptor 9 is decreased in chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps. am j rhinol. 2007;21(1):110–116. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2997. doi:10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JH, Kim GE, Cho GS, et al. Natural killer cells from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis have impaired effector functions. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077177. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blair C, Naclerio RM, Yu X, Thompson K, Sperling A. Role of type 1 T helper cells in the resolution of acute Streptococcus pneumoniae sinusitis: a mouse model. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(7):1237–1244. doi: 10.1086/444544. doi:10.1086/444544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilos DL. Antigen presenting cells. Immunol Res. 1989;8(2):98–117. doi: 10.1007/BF02919073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broere F, Apasov SG, Sitkovsky MV, Eden W. A2 T cell subsets and T cell-mediated immunity. In: Nijkamp FP, Parnham JM, editors. Principles of Immunopharmacology: 3rd revised and extended edition. Birkhäuser Basel; Basel: 2011. pp. 15–27. doi:10.1007/978-3-0346-0136-8_2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krysko O, Holtappels G, Zhang N, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages and impaired phagocytosis of S. aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2011;66(3):396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02498.x. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan M, Pamp SJ, Fukuyama J, et al. Nasal microenvironments and interspecific interactions influence nasal microbiota complexity and S. aureus carriage. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;14(6):631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramakrishnan VR, Feazel LM, Gitomer SA, Ir D, Robertson CE, Frank DN. The microbiome of the middle meatus in healthy adults. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e85507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085507. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-Inflammatory Therapy in Chronic Disease: Challenges and Opportunities. Science. 2013;339(6116):166–172. doi: 10.1126/science.1230720. doi:10.1126/science.1230720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489(7415):220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. doi:10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishnan VR, Feazel LM, Abrass LJ, Frank DN. Prevalence and abundance of Staphylococcus aureus in the middle meatus of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, and asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(4):267–271. doi: 10.1002/alr.21101. doi:10.1002/alr.21101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramakrishnan VR, Hauser LJ, Feazel LM, Ir D, Robertson CE, Frank DN. Sinus microbiota varies among chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes and predicts surgical outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):334–42.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.008. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449(7164):804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. doi:10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, et al. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the “healthy” smoker and in COPD. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e16384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abreu NA, Nagalingam NA, Song Y, et al. Sinus microbiome diversity depletion and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum enrichment mediates rhinosinusitis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra124. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003783. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLoughlin RM, Mills KHG. Influence of gastrointestinal commensal bacteria on the immune responses that mediate allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1097–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.012. quiz1108–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Buchvald F, et al. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1487–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052632. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139(3):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivanov II, Frutos R de L, Manel N, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008;4(4):337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, et al. Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(3):519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052016. doi:10.1084/jem.20052016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331(6015):337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. doi:10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasama J, Sherris DA, Shin S-H, Kephart GM, Kern EB, Ponikau JU. New paradigm for the roles of fungi and eosinophils in chronic rhinosinusitis. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 2005;13(1):2–8. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boase S, Foreman A, Cleland E, et al. The microbiome of chronic rhinosinusitis: culture, molecular diagnostics and biofilm detection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-210. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aurora R, Chatterjee D, Hentzleman J, Prasad G, Sindwani R, Sanford T. Contrasting the microbiomes from healthy volunteers and patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(12):1328–1338. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5465. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleland EJ, Bassiouni A, Bassioni A, et al. The fungal microbiome in chronic rhinosinusitis: richness, diversity, postoperative changes and patient outcomes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(4):259–265. doi: 10.1002/alr.21297. doi:10.1002/alr.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen EK, Koeppel AF, Hendley JO, Turner SD, Winther B, Sale MM. Characterization of the nasopharyngeal microbiota in health and during rhinovirus challenge. Microbiome. 2014;2:22. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-22. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson MT, Hamilos DL. The Nasal and Sinus Microbiome in Health and Disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(12):485. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0485-x. doi:10.1007/s11882-014-0485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feazel LM, Robertson CE, Ramakrishnan VR, Frank DN. Microbiome complexity and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):467–472. doi: 10.1002/lary.22398. doi:10.1002/lary.22398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephenson M-F, Mfuna L, Dowd SE, et al. Molecular characterization of the polymicrobial flora in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(2):182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frank DN, Zhu W, Sartor RB, Li E. Investigating the biological and clinical significance of human dysbioses. Trends in Microbiology. 2011;19(9):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Human Microbiome Project Consortium A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012;486(7402):215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11209. doi:10.1038/nature11209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. doi:10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014;509(7500):357–360. doi: 10.1038/nature13178. doi:10.1038/nature13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reshef L, Kovacs A, Ofer A, et al. Pouch Inflammation Is Associated With a Decrease in Specific Bacterial Taxa. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(3):718–727. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.041. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP, et al. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio. 2015;6(2):e00037. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00037-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi EB, Hong SW, Kim DK, et al. Decreased diversity of nasal microbiota and their secreted extracellular vesicles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis based on a metagenomic analysis. Allergy. 2014;69(4):517–526. doi: 10.1111/all.12374. doi:10.1111/all.12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. doi:10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ott SJ, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth DF, et al. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53(5):685–693. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025403. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.025403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A, et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):128–139. doi: 10.1002/art.38892. doi:10.1002/art.38892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang EY, Inoue T, Leone VA, et al. Using corticosteroids to reshape the gut microbiome: implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(5):963–972. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000332. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Modi SR, Collins JJ, Relman DA. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4212–4218. doi: 10.1172/JCI72333. doi:10.1172/JCI72333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramakrishnan VR, Frank DN. Impact of cigarette smoking on the middle meatus microbiome in health and chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(11):981–989. doi: 10.1002/alr.21626. doi:10.1002/alr.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brook I, Frazier EH. Correlation between microbiology and previous sinus surgery in patients with chronic maxillary sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110(2):148–151. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finegold SM, Flynn MJ, Rose FV, et al. Bacteriologic findings associated with chronic bacterial maxillary sinusitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(4):428–433. doi: 10.1086/341899. doi:10.1086/341899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nadel DM, Lanza DC, Kennedy DW. Endoscopically guided cultures in chronic sinusitis. am j rhinol. 1998;12(4):233–241. doi: 10.2500/105065898781390000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cleland EJ, Bassiouni A, Wormald P-J. The bacteriology of chronic rhinosinusitis and the pre-eminence of Staphylococcus aureus in revision patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(8):642–646. doi: 10.1002/alr.21159. doi:10.1002/alr.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sande MA, Gwaltney JM. Acute community-acquired bacterial sinusitis: continuing challenges and current management. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(Suppl 3):S151–S158. doi: 10.1086/421353. doi:10.1086/421353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skoner DP. Complications of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(6 Pt 2):S605–S609. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106150. doi:10.1067/mai.2000.106150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alho O-P. Nasal airflow, mucociliary clearance, and sinus functioning during viral colds: effects of allergic rhinitis and susceptibility to recurrent sinusitis. am j rhinol. 2004;18(6):349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012;(23):1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chee L, Graham SM, Carothers DG, Ballas ZK. Immune dysfunction in refractory sinusitis in a tertiary care setting. The Laryngoscope. 2001;111(2):233–235. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200102000-00008. doi:10.1097/00005537-200102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kingdom TT, Swain RE. The microbiology and antimicrobial resistance patterns in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(5):323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.003. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Estrela S, Whiteley M, Brown SP. The demographic determinants of human microbiome health. Trends in Microbiology. 2015;23(3):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suh JD, Ramakrishnan V, Palmer JN. Biofilms. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2010;43(3):521–30. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.010. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Psaltis AJ, Ha KR, Beule AG, Tan LW, Wormald P-J. Confocal scanning laser microscopy evidence of biofilms in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2007;117(7):1302–1306. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31806009b0. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31806009b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oncel S, Pinar E, Sener G, Calli C, Karagoz U. Evaluation of bacterial biofilms in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(1):52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hauser LJ, Feazel LM, Ir D, et al. Sinus culture poorly predicts resident microbiota. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(1):3–9. doi: 10.1002/alr.21428. doi:10.1002/alr.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Larson DA, Han JK. Microbiology of sinusitis: does allergy or endoscopic sinus surgery affect the microbiologic flora? Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 2011;19(3):199–203. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328344f67a. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e328344f67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bachert C, Zhang N, Patou J, van Zele T, Gevaert P. Role of staphylococcal superantigens in upper airway disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–38. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f4178f. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f4178f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pezato R, Świerczyńska-Krępa M, Niżankowska-Mogilnicka E, Derycke L, Bachert C, Pérez-Novo CA. Role of imbalance of eicosanoid pathways and staphylococcal superantigens in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2012;67(11):1347–1356. doi: 10.1111/all.12010. doi:10.1111/all.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pérez Novo CA, Waeytens A, Claeys C, Cauwenberge PV, Bachert C. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B regulates prostaglandin E2 synthesis, growth, and migration in nasal tissue fibroblasts. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(7):1036–1043. doi: 10.1086/528989. doi:10.1086/528989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Corriveau M-N, Zhang N, Holtappels G, Van Roy N, Bachert C. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus in nasal tissue with peptide nucleic acid-fluorescence in situ hybridization. am j rhinol allergy. 2009;23(5):461–465. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3367. doi:10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parvez N, Jinadatha C, Fader R, et al. Universal MRSA nasal surveillance: characterization of outcomes at a tertiary care center and implications for infection control. South Med J. 2010;103(11):1084–1091. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181f69235. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181f69235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jervis-Bardy J, Foreman A, Field J, Wormald P-J. Impaired mucosal healing and infection associated with Staphylococcus aureus after endoscopic sinus surgery. am j rhinol allergy. 2009;23(5):549–552. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3366. doi:10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foreman A, Holtappels G, Psaltis AJ, et al. Adaptive immune responses in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-associated chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1449–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02678.x. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lebeaux D, Ghigo J-M, Beloin C. Biofilm-related infections: bridging the gap between clinical management and fundamental aspects of recalcitrance toward antibiotics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78(3):510–543. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-14. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Psaltis AJ, Weitzel EK, Ha KR, Wormald P-J. The effect of bacterial biofilms on post–sinus surgical outcomes. am j rhinol. 2008;22(1):1–6. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3119. doi:10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sabini P, Josephson GD, Reisacher WR, Pincus R. The role of endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19(6):351–356. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Godoy JM, Godoy AN, Ribalta G, Largo I. Bacterial pattern in chronic sinusitis and cystic fibrosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(4):673–676. doi: 10.1177/0194599811407279. doi:10.1177/0194599811407279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hansen SK, Rau MH, Johansen HK, et al. Evolution and diversification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the paranasal sinuses of cystic fibrosis children have implications for chronic lung infection. ISME J. 2012;6(1):31–45. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.83. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carenfelt C, Lundberg C. The role of local gas composition in pathogenesis of maxillary sinus empyema. Acta Otolaryngol. 1978;85(1–2):116–121. doi: 10.3109/00016487809121431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jousimies-Somer HR, Savolainen S, Ylikoski JS. Macroscopic purulence, leukocyte counts, and bacterial morphotypes in relation to culture findings for sinus secretions in acute maxillary sinusitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(10):1926–1933. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.1926-1933.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Siqueira JF, Rôças IN. Community as the unit of pathogenicity: an emerging concept as to the microbial pathogenesis of apical periodontitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(6):870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.01.044. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Coyne MJ, Zitomersky NL, McGuire AM, Earl AM, Comstock LE. Evidence of extensive DNA transfer between bacteroidales species within the human gut. mBio. 2014;5(3):e01305–e01314. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01305-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01305-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McKay TL, Ko J, Bilalis Y, DiRienzo JM. Mobile genetic elements of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Plasmid. 1995;33(1):15–25. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1003. doi:10.1006/plas.1995.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(3):417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465(7296):346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. doi:10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leatham MP, Banerjee S, Autieri SM, Mercado-Lubo R, Conway T, Cohen PS. Precolonized human commensal Escherichia coli strains serve as a barrier to E. coli O157:H7 growth in the streptomycin-treated mouse intestine. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(7):2876–2886. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00059-09. doi:10.1128/IAI.00059-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fabich AJ, Jones SA, Chowdhury FZ, et al. Comparison of carbon nutrition for pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76(3):1143–1152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01386-07. doi:10.1128/IAI.01386-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hauser LJ, Ir D, Kingdom TT, Robertson CE, Frank DN, Ramakrishnan VR. Investigation of bacterial repopulation after sinus surgery and perioperative antibiotics. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(1):34–40. doi: 10.1002/alr.21630. doi:10.1002/alr.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Munyaka PM, Khafipour E, Ghia J-E. External influence of early childhood establishment of gut microbiota and subsequent health implications. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:109. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00109. doi:10.3389/fped.2014.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68(4):820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mukerji SS, Pynnonen MA, Kim HM, Singer A, Tabor M. Terrell JE. Probiotics as adjunctive treatment for chronic rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.020. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cleland EJ, Drilling A, Bassiouni A, James C, Vreugde S, Wormald P-J. Probiotic manipulation of the chronic rhinosinusitis microbiome. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(4):309–314. doi: 10.1002/alr.21279. doi:10.1002/alr.21279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rudmik L, Soler ZM. Medical Therapies for Adult Chronic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(9):926–939. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7544. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 Suppl):S1–S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. doi:10.1177/0194599815572097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dellamonica P, Choutet P, Lejeune JM, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of cefotiam hexetil in the super-infected chronic sinusitis. A randomized, double-blind study in comparison with cefixime. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1994;111(4):217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Legent F, Bordure P, Beauvillain C, Berche P. A double-blind comparison of ciprofloxacin and amoxycillin/clavulanic acid in the treatment of chronic sinusitis. Chemotherapy. 1994;40(Suppl 1):8–15. doi: 10.1159/000239310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Huck W, Reed BD, Nielsen RW, et al. Cefaclor vs amoxicillin in the treatment of acute, recurrent, and chronic sinusitis. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(5):497–503. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martinez-Devesa P, Patiar S. Oral steroids for nasal polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD005232. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005232.pub3. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005232.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van Zele T, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, et al. Oral steroids and doxycycline: two different approaches to treat nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(5):1069–1076.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.020. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wallwork B, Coman W, Mackay-Sim A, Greiff L, Cervin A. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of macrolide in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116(2):189–193. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000191560.53555.08. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000191560.53555.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Videler WJ, Badia L, Harvey RJ, et al. Lack of efficacy of long-term, low-dose azithromycin in chronic rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1457–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02693.x. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Soler ZM, Oyer SL, Kern RC, et al. Antimicrobials and chronic rhinosinusitis with or without polyposis in adults: an evidenced-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(1):31–47. doi: 10.1002/alr.21064. doi:10.1002/alr.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]