Abstract

Rationale

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) is a cross-species neuroimaging technique that can measure concentrations of several brain metabolites, including glutamate and GABA. This non-invasive method has promise in developing centrally acting drugs, as it can be performed repeatedly within-subjects and be used to translate findings from the preclinical to clinical laboratory using the same imaging biomarker.

Objectives

This review focuses on the utility of single-voxel 1H-MRS in developing novel glutamatergic or GABAergic drugs for the treatment of psychiatric disorders and includes research performed in rodent models, healthy volunteers and patient cohorts.

Results

Overall, these studies indicate that 1H-MRS is able to detect the predicted pharmacological effects of glutamatergic or GABAergic drugs on voxel glutamate or GABA concentrations, although there is a shortage of studies examining dose-related effects. Clinical studies have applied 1H-MRS to better understand drug therapeutic mechanisms, including the glutamatergic effects of ketamine in depression and of acamprosate in alcohol dependence. There is an emerging interest in identifying patient subgroups with ‘high’ or ‘low’ brain regional 1H-MRS glutamate levels for more targeted drug development, which may require ancillary biomarkers to improve the accuracy of subgroup discrimination.

Conclusions

Considerations for future research include the sensitivity of single-voxel 1H-MRS in detecting drug effects, inter-site measurement reliability and the interpretation of drug-induced changes in 1H-MRS metabolites relative to the known pharmacological molecular mechanisms. On-going technological development, in single-voxel 1H-MRS and in related complementary techniques, will further support applications within CNS drug discovery.

Keywords: Glutamate, GABA, Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Psychiatry, Drug development, Biomarkers

Introduction

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) is a non-invasive in vivo technique that can be used to measure regional concentrations of brain metabolites, including glutamate and γ-amino butyric acid (GABA). A major advantage of 1H-MRS in central nervous system (CNS) drug discovery is that it provides a translational technique, whereby the ability of pharmacological compounds to modulate a MRS-detectable metabolite of interest in laboratory animals can then be tested in healthy humans or patient populations using the same imaging biomarker. In parallel, key findings from clinical research can be translated back to the preclinical laboratory, to develop animal disease models and test potential compounds for their ability to modulate brain metabolite abnormalities associated with CNS disorders.

This article reviews the potential of 1H-MRS for CNS drug development, with a focus on the development of novel glutamatergic and GABAergic compounds for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. The review describes the relevance of 1H-MRS-quantifiable metabolites to drug discovery, before discussing potential applications at different stages of drug development. In this emerging area, the review provides examples of applications to date and then considers the current limitations and future directions for research.

1H-MRS metabolites: relevance to psychiatric drug discovery

In vivo 1H-MRS is an MRI-based neuroimaging approach, which is most commonly used to measure metabolites in a predefined three-dimensional voxel, prescribed in a brain region of interest rather than across the whole brain. Depending on the magnetic field strength of the MRI scanner and acquisition sequence, it is now possible to detect over 18 metabolites in an in vivo 1H-MRS spectrum (Pfeuffer et al. 1999). Both human and rodent 1H-MRS can measure several metabolites involved in neurotransmission, oxidative stress or inflammation, which are key targets of interest for CNS drug discovery.

1H-MRS metabolites involved in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission

Within drug discovery for psychiatric disorders, the majority of 1H-MRS research has focussed on glutamate and GABA. At lower field strengths of around 1.5 Tesla (which corresponds to most clinical MRI scanners), glutamate and its metabolite glutamine have overlapping resonances and are usually reported in combination, termed Glx (Hancu 2009). At higher field strengths of 3 Tesla and above (corresponding to MRI scanners for clinical research), it becomes increasingly possible to resolve the glutamate and glutamine signals (Mullins et al. 2008; Snyder and Wilman 2010; Terpstra et al. 2016; Tkac et al. 2001) and their resolution may be further improved with specialised pulse sequences (Bustillo et al. 2016; Mekle et al. 2009; Wijtenburg and Knight-Scott 2011; Zhang and Shen 2016). GABA is less abundant than glutamate and has overlapping resonances with other metabolites, and detection of GABA can be facilitated through application of spectral editing, typically using Mescher-Garwood point resolved spectroscopy (MEGA-PRESS) (Puts and Edden 2012). Glutamate and glutamine may also be measurable in GABA-edited MEGA-PRESS spectra although there are challenges around their reliable quantification (Sanaei Nezhad et al. 2018).

An important consideration is that 1H-MRS quantifies the total amount of MR visible metabolite in the voxel, so glutamate levels will reflect neurotransmission but also other cellular metabolic processes. Glutamate released from synapses is rapidly converted to glutamine in astrocytes for recycling to glutamate and GABA, and this accounts for approximately 80% of glutamine synthesis (Kanamori et al. 2002; Rothman et al. 2011; Rothman et al. 1999; Sibson et al. 1997; Sibson et al. 2001). Some studies have drawn inferences about glutamate, glutamine or GABA concentrations though investigating changes in their relative ratios. Elevations in the glutamine to glutamate ratio have been interpreted as increased glutamate turnover (Brennan et al. 2010; Bustillo et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2005), and regional glutamate to GABA ratios have been discussed in the context of excitatory-inhibitory (E/I) balance (Ajram et al. 2017; Cohen Kadosh et al. 2015; Colic et al. 2018; Ferri et al. 2017; Foss-Feig et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2019). Nonetheless, the cellular mechanisms that may underpin an observed difference in the 1H-MRS glutamine/glutamate or GABA/glutamate signal ratio are complex, and when interpreting metabolite ratios it is important to consider whether the observed differences in ratios are primarily driven by the numerator or denominator.

At high field strengths, it may become possible to quantify additional glutamatergic metabolites in the 1H-MRS spectra, including glycine, serine and n-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) (discussed in Harris et al. 2017) (Fig. 1). Due to their function as N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor co-agonists, glycine and serine are of interest to drug discovery in psychiatric disorders associated with NMDA receptor dysfunction, most prominently schizophrenia (Goff 2015; Moghaddam and Javitt 2012). Glycine and serine also act as inhibitory neurotransmitters through activating glycine receptors-chloride channels (Legendre 2001). In man, glycine has been measured at field strengths of 3 T or more using specialised sequences (Kaufman et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2017; Prescot et al. 2006; Tiwari et al. 2017), while the detection of serine remains more challenging (Harris et al. 2017).

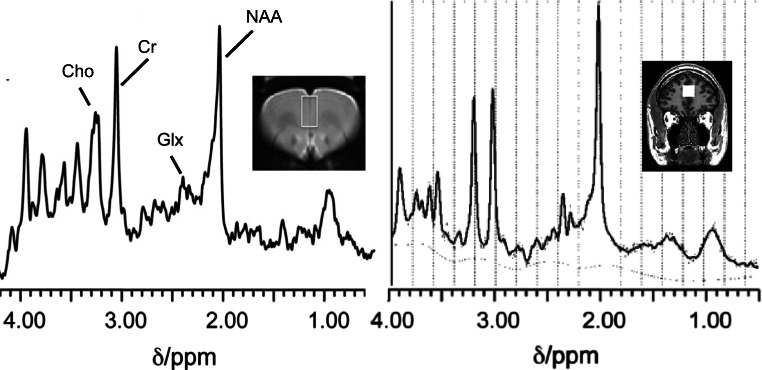

Fig. 1.

Representative 1H-MRS spectra from the rat (left) and human (right) medial prefrontal cortex. The images show the 1H-MRS voxel position in each species overlaid on the corresponding anatomical MRI image. In the rat, spectra were acquired under 1.0% isoflurane anaesthesia in a 3.8 × 2.2 × 2.0-mm voxel at 7 Tesla (Agilent Technologies Inc.) using a point-resolved spin-echo sequence (PRESS) with a repetition time (TR) of 3000 ms and an echo time (TE) of 24 ms.(Vernon et al. 2015) In man, spectra were acquired in a 20 × 20 × 20-mm voxel at 3 Tesla (GE MR750, General Electric Healthcare), using a PRESS sequence with TR = 2000 ms and TE = 35 ms. Representative spectra in each species, provided using LCModel software (Provencher 1993), show peaks for choline-containing compounds (Cho), creatine (Cr), glutamate and glutamine (Glx) and N-acetylaspartate (NAA)

NAAG, present in neurons and glia, is a neuromodulatory peptide that acts as an agonist at mGluR3 receptors to decrease neurotransmitter release (see Neale et al. 2011). NAAG can also act as a NMDA receptor antagonist (Bergeron et al. 2007) or agonist (Westbrook et al. 1986) depending on the cellular environment and subunit composition of the NMDA receptors, among other factors (Khacho et al. 2015). Compounds that increase NAAG, such as NAAG peptidase inhibitors, may have therapeutic effects that may be associated with mGluR2/3 agonism, including antipsychotic effects (Olszewski et al. 2004) or decreasing additive behaviours (Xi et al. 2010a, b). While it may be possible to isolate NAAG from the larger n-acetylaspartate (NAA) signal using spectral editing at human field strengths (Edden et al. 2007; Harris et al. 2017), few studies have used these techniques (Jessen et al. 2011; Landim et al. 2016; Rowland et al. 2013).

1H-MRS metabolites as markers of brain inflammation or oxidative stress

Also relevant to drug discovery in psychiatric disorders are 1H-MRS metabolites that act as antioxidants and markers of brain inflammation. Myo-inositol (mIns), a precursor of the phosphatidylinositol membrane lipids (Berridge and Irvine 1989) and choline-containing compounds (phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine) are predominantly expressed in glial cells (Brand et al. 1993; Urenjak et al. 1993). Both mIns and choline have been interpreted as markers of glial activation, which may provide a proxy measure of inflammation (Bagory et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2004; Chang et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Kirov et al. 2009). These metabolites could therefore be used as a marker for target engagement for anti-inflammatory drugs, for example in patients with traumatic brain injury (Harris et al. 2015), but also in psychiatric disorders associated with inflammation including depression (Caetano et al. 2005; Venkatraman et al. 2009) and schizophrenia (Plitman et al. 2016; Rowland et al. 2017). Potentially, mIns and choline could also be used as a biomarker to stratify such patients for clinical trials of anti-inflammatory treatments. Glutathione (GSH), an endogenous antioxidant, is also detectable in the 1H-MRS spectra and could provide a translational biomarker for antioxidant drug development (Conus et al. 2018).

1H-MRS can detect other several metabolites involved in brain regulatory processes such as myelination, membrane lipid metabolism and energy metabolism (reviewed in Duarte et al. 2012). These metabolites, including glucose, lactate, creatine and N-acetylaspartate (NAA), are of less interest to pharmacoMRS studies, but may be relevant for the creation or validation of animal models mimicking pathological changes observed in clinical populations. For example, the most abundant metabolite in the 1H-MRS spectra, NAA, is expressed almost completely in neurons. NAA is commonly interpreted as a marker of neuronal integrity, although the physiological roles of NAA in neuronal function remain largely unresolved (Ariyannur et al. 2013; Moffett et al. 2007). Psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder show regional NAA reductions (Brugger et al. 2011; Kraguljac et al. 2012; Schwerk et al. 2014) which could be recapitulated in animal models, although the extent to which NAA reductions may be reversed with pharmacological treatment is not clear.

Potential applications of 1H-MRS in drug development

1H-MRS could potentially be applied to accelerate CNS drug discovery at various stages of the drug development pipeline, either alone or in combination with other imaging modalities (Wong et al. 2009). This is an emerging application of 1H-MRS within psychiatry. As such, the following section discusses the potential of this approach using examples where they are already available and considers the future developments that are required to support wider implementation. Box 1 provides selected examples of current 1H-MRS applications, and Box 2 summarises key considerations for future research.

Box 1: Selected examples of current applications of 1H-MRS in psychiatric research and CNS drug development

|

Translation of rodent models to man Example: Increases in frontal or hippocampal glutamatergic metabolites occurring on ketamine administration, as a cross-species model of NMDA hypofunction in schizophrenia (Bojesen et al. 2018; Javitt et al. 2018; Kraguljac et al. 2017; Rowland et al. 2005; Stone et al. 2012). | |

|

Understanding drug therapeutic mechanisms Example: Ketamine-induced changes in frontal or occipital glutamate in relation to antidepressant efficacy (Evans et al. 2018; Milak et al. 2016; Valentine et al. 2011). | |

|

Target engagement Example: Increases in prefrontal glutamate metabolites and GABA on d-cycloserine administration (Kantrowitz et al. 2016). | |

|

Preclinical model development Example: Effects of maternal immune activation, a risk factor for psychiatric disorders in offspring, on brain metabolites during rat developmental maturation (Vernon et al. 2015). | |

|

Refining the therapeutic rationale Example: Linking pre-treatment glutamate levels to the degree of subsequent clinical response in first episode psychosis (Egerton et al. 2018; Szulc et al. 2013) or in bipolar disorder (Strawn et al. 2012). |

Box 2: Key considerations for 1H-MRS in psychiatric research and CNS drug development

| The extent to which 1H-MRS can detect dose-dependent drug effects at clinically relevant doses in man. | |

| Whether the signal change in pharmacoMRS studies is of sufficient magnitude and reliability to investigate the ability of second compound to attenuate the drug effect. | |

| Unclear relationships between pharmacological molecular mechanisms and 1H-MRS metabolite signal change. | |

| Issues around standardisation of data acquisition, read-out, intra and inter-site reliability, particularly for multicentre studies. |

.

Biomarkers for target engagement

A first potential application of 1H-MRS is to employ pharmacologically induced changes in the 1H-MRS metabolite of interest (pharmacological MRS ‘pharmacoMRS’) as a biomarker of target engagement (TE). In preclinical studies, the most promising drug candidates could be selected from a series of compounds by examining their ability to modulate the target metabolite. A similar approach could assist dose selection of the candidate compound. Lead compounds could then be translated to human 1H-MRS studies using the same 1H-MRS TE biomarker for confirmation, before proceeding to clinical trials.

Application of 1H-MRS for TE requires prior confirmation that 1H-MRS has sensitivity to detect pharmacologically evoked changes in brain metabolites at relevant doses, and that these changes are consistent with established pharmacological drug effects (see Waschkies et al. 2014). Within psychiatric drug development, preclinical and clinical 1H-MRS studies have mainly investigated the effects of glutamatergic and GABAergic compounds (Table 1). Studies examining glutamatergic metabolites have variously reported changes in Glx, glutamate or glutamine. As discussed above, the reported glutamatergic metabolites will reflect the methodological features of the study that determine the ability to resolve signals from glutamine from glutamate, as well as potentially differential biological effects of the pharmacological challenge on glutamate versus glutamine concentrations. While there are some negative findings, overall, these studies indicate that 1H-MRS has sensitivity to detect the hypothesised drug effects, and that comparable effects can be observed in rodent and human pharmacoMRS.

Table 1.

Preclinical and clinical in vivo pharmacoMRS studies of glutamatergic and GABAergic compounds

| Author | Subject | Compound, design | Dosing | Voxel location | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMDA receptor antagonists | |||||

| Iltis et al. (2009) | Rat | Phencyclidine vs. saline | 10 mg/kg i.p. | PFC | Increase in Gln/Glu; NS for Glu, Gln |

| Lee et al. (2010) | Dog | Ketamine vs. pentobarbital anaesthesia | 15 mg/kg i.v. | Striatum | Increase in Glx |

| Kim et al. (2011) | Rat | Ketamine vs. saline | 30 mg/kg for 6 days | PFC | Increase in Glu |

| Napolitano et al. (2014) | Rat | Ketamine vs. saline | 25 mg/kg i.p. | ACC/mFC | Increase in Gln in group-housed, decrease in GABA in isolated |

| Yoo et al. (2017) | Rat | MK-801 vs. saline | 0.5 mg/kg for 6 days | PFC | NS for Glu, Gln |

| Sekar et al. (2018) | Rat | Memantine vs. vehicle | 20 mg/kg/day i.p for 5 days | Hippocampus | NS for Glu, Gln, GABA |

| Servaes et al. (2019) | Rat | MK-801 or ebselen vs. saline | MK-801 0.3 mg/kg i.p., ebselen 10 mg/kg p.o. for 7 days | Striatum | NS for Glu, decrease in Gln in ebselen group. |

| Rowland et al. (2005) | Human (HV) | Ketamine vs. placebo, crossover | Loading 0.27 mg/kg over 10 min; maintenance 0.00225 mg/kg/min for up to 2 h | ACC | Increase in Gln during loading dose, NS for Glu |

| Valentine et al. (2011) | Human (MDD) | Ketamine vs. saline pre-post | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | OCC | NS for Glu, Gln, GABA |

| Taylor et al. (2012) | Human (HV) | Ketamine vs. placebo parallel group | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | ACC | NS for Glu or Glx |

| Stone et al. (2012) | Human (HV) | Ketamine, pre-post | 0.26 mg/kg bolus then 0.42 mg/kg/h | ACC (Glu) and thalamus (GABA) | Increase in ACC Glu, NS for Glx or GABA, 25–35 min after bolus |

| Milak et al. (2016) | Human (MDD) | Ketamine pre-post | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | mPFC | Increase in Glu and GABA over 40 min |

| Rodriguez et al. (2015) | Human (OCD) | Ketamine vs. placebo, crossover | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | mPFC | Increase in GABA; NS for Glx over 60 min |

| Li et al. (2017) | Human (HV) | Ketamine vs. placebo parallel group | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | pgACC and aMCC | Increase in Gln/Glu in pgACC at 24 h but not 1 h post-ketamine |

| Kraguljac et al. (2017) | Human (HV) | Ketamine pre-post | 0.27 mg/kg over 10 min, then 0.25 mg/kg/h for 50 min | Left hippocampus | Increase in Glx |

| Bojesen et al. (2018) | Human (HV) | S-Ketamine, pre-post | Loading 0.25 mg/kg for 20 min, maintenance 0.125 mg/kg for 20 min | ACC, thalamus | NS for Glu, Glx or Gln |

| Javitt et al. (2018) | Human (HV) | Ketamine vs. placebo, parallel group. | 0.23 mg/kg for 1 min, then 0.58 mg/kg/h over 30 min, then 0.29 mg/kg/h over 29 min. | ACC (mPFC) | Increase Glx over first 15 min, NS between 15 and 60 min |

| Evans et al. (2018) | Human (HV and MDD) | Ketamine vs placebo, crossover | 0.5 mg/kg over 40 min | pgACC | Glu NS in both HV and MDD at 24 h post-ketamine |

| NMDA glycine site agonists (direct or indirect) | |||||

| Kaufman et al. (2009) | Human (HV) | Glycine | 0.2 to 0.8 g/day for 2 weeks | OCC | Increase in Gly; NS for Glu |

| Strzelecki et al. (2015b) | Human (SCZ) | Sarcosine vs. placebo parallel group | 2 g/day for 6 months | Left frontal white matter | Increase in Glx |

| Strzelecki et al. (2015c) | Human (SCZ) | Sarcosine vs. placebo parallel group | 2 g/day for 6 months | Left dlPFC | Glx NS |

| Strzelecki et al. (2015a) | Human (SCZ) | Sarcosine vs. placebo parallel group | 2 g/day for 6 months | Left Hippocampus | Decrease in Glx |

| Kantrowitz et al. (2016) | Human | d-Cycloserine, pre-post | 1000 mg | mPFC | Increase in Glx |

| N-acetylcysteine | |||||

| Durieux et al. (2015) | Mouse | N-acetylcysteine vs. vehicle | 150 mg/kg i.p. | Left striatum | Decrease Glu |

| das Neves Duarte et al. (2012) | Mouse | N-acetylcysteine | 2.4 g/L in drinking water during development | Anterior cortex | Decrease Gln and Gln:Glu; Glu NS |

| Schmaal et al. (2012) | Human (cocaine-dependent) | N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo crossover | 2.4 g single oral dose | ACC | Decrease Glu |

| Das et al. (2013) | Human (MDD) | N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo, parallel group | 2 g/day for 12 weeks | mPFC | Increase Glx |

| Conus et al. (2018) | Human (EP) | N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo, parallel group | 2.7 g/day for 6 months | mPFC | Glu, Gln, Gln:Glu NS |

| Schulte et al. (2017) | Human (smokers) | N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo, parallel group | 2.4 g/day for 14 days | ACC | Glx, GABA NS |

| McQueen et al. (2018) | Human (SCZ) | N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo crossover | 2.4 g single oral dose | ACC, right caudate | Decrease Glx in ACC, Glu NS. |

| Girgis et al. (2019) | Human (HV and SCZ) | N-acetylcysteine, pre-post | 2.4 g single oral dose | dACC, mPFC | Glu, Glx, NS |

| O'Gorman Tuura et al. (2019) | Human (HV) | N-acetylcysteine vs no intervention, crossover | 5 g i.v. over 1 h | PFC, striatum | Striatum: decrease Glx, Gln; PFC decrease Glx; Glu NS. |

| Riluzole | |||||

| Waschkies et al. (2014) | Rat | Riluzole vs. vehicle | 3, 6, and 12 mg/kg i.p | PFC, striatum | PFC and striatum decrease Glu |

| Rizzo et al. (2017) | Rat | Riluzole vs. vehicle | 6 mg/kg/day i.p, 15 days | Left mPFC, left striatum | In hypertensive but not control rats, decrease PFC Glu and Gln; GABA NS |

| Brennan et al. (2010) | Human (BPD) | Riluzole, pre-post | 100-200 mg/day for 6 weeks | ACC, POC | Increase in Gln/Glu between days 0–2 |

| Ajram et al. (2017) | Human (HV and ASD) | Riluzole vs placebo, crossover | 50 mg oral single dose | dlPFC | Increased GABA/GABA + Glx in HV; Decreased GABA/GABA + Glx in ASD |

| Pillinger et al. (2019) | Human (HV and SCZ) | Riluzole, pre-post | 50 mg twice daily for 2 days | ACC | Group by condition interaction related to Glx decrease in SCZ and increase in HV |

| Other glutamatergic drugs | |||||

| Waschkies et al. (2014) | Rat | MSO vs. vehicle | 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg i.p. | PFC, striatum | PFC: dose-dependent decrease Glu increase Gln; striatum: decrease GABA increase Gln |

| Godlewska et al. (2018) | Human (BPD) | Lamotrigine, pre-post | TAU, 10–12 weeks | ACC | Glx NS |

| Umhau et al. (2010) | Human (alcohol dependence) | Acamprosate, pre-post | oral loading followed by 1998 mg daily for 4 weeks | ACC | Decrease Glu |

| Frye et al. (2016) | Human (alcohol dependence) | Acamprosate, pre-post | 4 weeks | ACC | Decrease Glu |

| GABAergic drugs | |||||

| Waschkies et al. (2014) | Rat | Vigabatrin vs. vehicle | 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg i.p. | PFC, striatum | Dose-dependent increase in GABA in PFC and striatum, decrease in Glu in PFC, increase in Gln in striatum |

| De Graaf (2006) | Rat | Vigabatrin pre-post | 750 mg/kg, i.v. | Cortex | Increase GABA |

| Patel et al. (2006) | Rat | Vigabatrin vs. no treatment | 0.5 g/kg, i.p., 24 h before study | Cortex | Increase GABA |

| Waschkies et al. (2014) | Rat | 3-MP vs. vehicle | 20, 30, and 40 mg/kg i.p. | PFC, striatum | Dose-dependent decrease GABA in striatum; PFC GABA NS; decrease PFC Glu; Gln NS |

| Waschkies et al. (2014) | Rat | Tiagabine vs. vehicle | 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg per os | PFC, striatum | Increase GABA and Gln in striatum; decrease Glu PFC |

| Myers et al. (2014) | Human (HV) | Tiagabine pre-post | 15 mg single oral dose | OCC, limbic region | NS GABA |

ACC anterior cingulate cortex, ASD autism spectrum disorder, aMCC anterior midcingulate cortex, BPD bipolar disorder, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, EP early psychosis, GABA γ-amino-butyric acid, Glu glutamate, Gln glutamine, Gly glycine, Glx glutamate plus glutamine, HV healthy volunteers, i.p. intraperitoneal, i.v. intravenous, MDD major depressive disorder, 3-MP 3-mercaptopropionate, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, MSO methionine sulfoximine, NS non-significant, OCD obsessive compulsive disorder, OCC occipital cortex, PFC prefrontal cortex, pgACC pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, POC parietal-occipital cortex, SCZ schizophrenia, TAU treatment as usual

A number of 1H-MRS studies have now examined the effects of administration of NMDA antagonists such as ketamine (Table 1), which are expected to increase extracellular glutamate (Moghaddam et al. 1997). Ketamine has mainly been investigated as an experimental model of NMDA hypofunction in schizophrenia (Bojesen et al. 2018; Javitt et al. 2018; Kraguljac et al. 2017; Rowland et al. 2005; Stone et al. 2012), or in relation to its antidepressant effects (Evans et al. 2018; Li et al. 2017; Milak et al. 2016; Taylor et al. 2012; Valentine et al. 2011). As hypothesised, several studies have observed increases in the glutamate, glutamine or Glx signal following NMDA antagonist administration, both in experimental animals (Iltis et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2010; Napolitano et al. 2014) and in man (Javitt et al. 2018; Kraguljac et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Milak et al. 2016; Rowland et al. 2005; Stone et al. 2012). However, some studies have not observed any changes in glutamatergic metabolites (Bojesen et al. 2018; Evans et al. 2018; Rodriguez et al. 2015; Sekar et al. 2018; Servaes et al. 2019; Taylor et al. 2012; Valentine et al. 2011; Yoo et al. 2017). Increases in Glx in the human medial prefrontal cortex were also observed after a single administration of NMDA receptor glycine site partial agonist d-cycloserine, which like ketamine is of interest as an antidepressant (Kantrowitz et al. 2016). Conversely, the few studies examining administration of glycine site agonists, which may be predicted to reduce glutamate levels via increased NMDA receptor activation, have produced mixed results; no difference in glutamate was apparent after 2 weeks of glycine administration (Kaufman et al. 2009), and in patients with schizophrenia, 6 months of sarcosine produced regionally dependent changes in Glx (Strzelecki et al. 2015a, b). Decreases in glutamatergic metabolites (glutamate, glutamine or Glx) have been observed across species following administration of several other compounds, including n-acetylcysteine (das Neves Duarte et al. 2012; Durieux et al. 2015; McQueen et al. 2018; O'Gorman Tuura et al. 2019; Schmaal et al. 2012), riluzole (Rizzo et al. 2017; Waschkies et al. 2014) and acamprosate (Frye et al. 2016; Umhau et al. 2010), although again not without some negative or discrepant findings (Table 1) (Brennan et al. 2010; Das et al. 2013; Girgis et al. 2019; Pillinger et al. 2019; Schulte et al. 2017).

There are fewer studies examining GABAergic compounds. In rats, 1H-MRS GABA levels show the predicted increases on administration of the GABA-transaminase inhibitor vigabatrin (de Graaf et al. 2006; Patel et al. 2006; Waschkies et al. 2014), or GABA transporter inhibitor tiagabine (Waschkies et al. 2014), and decreases on administration of 3-mercaptopropionate (3-MP), a glutamic acid decarboxylase inhibitor (Waschkies et al. 2014). The only human 1H-MRS study investigating administration of a GABAergic compound, tiagabine, did not observe significant change in GABA (Myers et al. 2014).

To investigate whether 1H-MRS glutamate and GABA are sensitive to dose-dependent effects, Waschkies et al. (2014) examined a range of doses of five glutamatergic or GABAergic compounds (vigabatrin, 3-mercaptopropionate, tiagabine, methionine sulfoximine and riluzole) in rats. Dose-related effects were detected in the frontal cortex and striatum, which should be confirmed in further rodent studies. To date, human 1H-MRS studies of acute glutamatergic or GABAergic drug effects have only investigated single doses (Table 1). Whether 1H-MRS has sensitivity to detect dose-related changes in glutamate and GABA metabolites in man within acceptable human dose ranges therefore remains to be established.

Research into the development of glutamate-targeting drugs for schizophrenia has provided some examples of how 1H-MRS TE biomarkers might be applied in early phase clinical trials. The variability with which symptoms of schizophrenia improve during adjunctive glycine treatment may partially depend on individual differences in glycine CNS penetration (Kaufman et al. 2009). In healthy volunteers, Kaufman et al. (2009) showed that 1H-MRS was able to detect increases in brain glycine levels over 2 weeks of glycine administration. In further clinical trials of compounds designed to increase glycine concentrations in patients, 1H-MRS could be used to measure the extent of TE and relationship with efficacy. As a similar example, 1H-MRS has been applied as a marker of TE in a clinical trial of the antioxidant and glutathione (GSH) precursor n-acetylcysteine (Conus et al. 2018). In patients with early psychosis, significant increases (22.6%) in medial prefrontal cortex GSH levels were observed after 6 months of administration of N-acetylcysteine but not placebo, indicating N-acetylcysteine TE (Conus et al. 2018). A final example concerns the attenuation of ketamine-induced increases in 1H-MRS Glx as a biomarker for TE in early stage clinical trials of novel glutamatergic compounds (Javitt et al. 2018). This multicentre study detected ketamine-induced increases in Glx in the medial frontal cortex with a moderate effect size of d = 0.6, although this may not provide sufficient power for reliably detecting subsequent reversal by glutamatergic compounds (Javitt et al. 2018). Similar applications of 1H-MRS may be strengthened by the combination of 1H-MRS with other biomarkers of TE in a multimodal approach as well as technical refinements to increase sensitivity.

Preclinical model development

A second application of 1H-MRS within drug development is to translate findings in clinical populations back to animal models, to determine the validity of the model in recapitulating the neurochemical abnormality seen in the patient population using the same imaging technique. As a next step, the ability of pharmacological compounds to restore levels of 1H-MRS metabolites to control levels may then be used as a translational predictive biomarker for efficacy.

A key advantage of 1H-MRS in animal models is that data can be acquired repeatedly in the same animal, to provide longitudinal studies of drug effects. For example, this has allowed investigation of the effects of psychoactive bacteria on brain neurometabolites and how these respond after cessation of treatment (Janik et al. 2016), the changes in brain metabolites in rats exposed to maternal immune activation as they develop through adolescence into adulthood (Vernon et al. 2015) and the effects of pharmacological interventions on the emerging developmental abnormalities in genetically modified compared to wild-type mice (das Neves Duarte et al. 2012). These types of within-subject studies may also bring statistical advantages and reduce the numbers of experimental animals required.

Refining the therapeutic rationale and patient stratification

Within psychiatric disorders, 1H-MRS research has not revealed a clear abnormality in brain metabolites that could be used diagnostically (as is the case for other biological measures). 1H-MRS glutamate studies comparing patients with schizophrenia to healthy volunteers have produced mixed findings, which may be related to illness stage, antipsychotic effects or other factors (Marsman et al. 2011; Merritt et al. 2016). In major depressive disorder (Moriguchi et al. 2018) and bipolar disorder (Taylor 2014), 1H-MRS studies may also indicate subgroups of patients within the diagnosis. Understanding this biological heterogeneity within a given diagnostic category may be a crucial factor in successful drug development. This raises the possibility that 1H-MRS measures could be used as a biomarker for intermediate phenotypes, to identify the subgroup of patients who are more likely to respond to a particular pharmacological intervention, and to stratify patients for clinical trials of this intervention.

While this is an emerging area of research, there is some early evidence to support the use of 1H-MRS in refining the therapeutic rationale and clinical trial stratification. Measures of glutamatergic 1H-MRS metabolites prior to starting a pharmacological treatment have been associated with the subsequent degree of response to a number of compounds, including antipsychotics in patients with first episode psychosis or established schizophrenia (Egerton et al. 2018; Szulc et al. 2013), ketamine in major depressive disorder (Salvadore et al. 2012) or valproate in bipolar disorder (Strawn et al. 2012). However, although these studies provide information on biological factors that may influence the degree of response to glutamate-acting drugs, significant further work is needed before 1H-MRS can be used to pre-select patient subgroups for stratified clinical trials. This would require reproducible data to define cut-off values for the level of the metabolite of interest that can most accurately predict the subgroup likely respond to the intervention and knowledge of the accuracy of the prediction. While 1H-MRS metabolite levels alone may not provide sufficient predictive accuracy for stratification, potentially the degree of accuracy could be improved through combination with other predictive variables (Egerton et al. 2018). Moreover, in the context of large clinical trials involving multiple recruitment sites, the non-trivial issues of standardisation of 1H-MRS acquisition and data values for patient selection across sites would be necessary. Research into the development of glutamatergic drugs for depression, schizophrenia or other disorders has revealed inverted U or non-linear dose-response relationships (Abdallah et al. 2018b; Foss-Feig et al. 2017). This suggests that measurement of pre-treatment levels of glutamatergic function may be important in identifying patient subgroups more likely to respond to novel glutamate-acting drugs, but may also complicate the use of 1H-MRS glutamate measures for patient stratification or dose selection.

Other studies have found no relationship between pre-treatment metabolite levels and response, but instead indicate that the degree of change in metabolite levels during treatment may mediate the extent of symptomatic improvement (Brennan et al. 2017; de la Fuente-Sandoval et al. 2013; Godlewska et al. 2018; Goff et al. 2002). In addition to providing mechanistic information, these studies are interesting in that they may suggest that early changes in glutamate metabolites occurring within the first 1–2 weeks of treatment may predict longer-term clinical outcomes. Such treatment-emergent biomarkers could be used in adaptive clinical trial design, where early ‘brain-level’ indicators of response could inform the treatment paradigm. As this approach would centre on the within-subjects change in 1H-MRS metabolite level rather than an individual value at a single time-point, some issues relating to standardisation of 1H-MRS data across multiple sites may be reduced.

General limitations and future directions

A main limitation of 1H-MRS is that it measures the total voxel concentration of the MR-visible metabolite, across all cellular compartments. In glutamatergic or GABAergic drug development studies, this indirect measure of TE may limit the sensitivity and interpretation, as the relationship between interaction at the molecular drug target and the change in the total MR-visible glutamate or GABA signal may be non-linear or uncertain. As 1H-MRS is a technique that is translatable across species, combination with invasive methodologies in rodents such as microdialysis or fast-scan cyclic voltammetry could aid interpretation of the 1H-MRS signal. Where feasible, 1H-MRS could also be combined with more direct measures of target engagement in both humans and other animals, such as glutamate receptor occupancy as measured using positron emission tomography (PET) (Gruber and Ametamey 2017).

There is also on-going development of complementary MRS approaches that may provide deeper information on glutamatergic signalling. The far more technically challenging technique of carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectroscopy (13C-MRS) can measure glutamate-glutamine cycling by following the flow of a 13C isotope through the tricarboxylic acid cycle (see Rothman et al. 2011). To date, the application of 13C-MRS has been limited by technical complexity, sensitivity, spatial resolution and other factors, but with future technological advances, this technique may be of significant application to glutamatergic drug development. Indeed, a recent human study of ketamine using 13C-MRS found increases in prefrontal 13C glutamine enrichment, indicating increased glutamate-glutamine cycling (Abdallah et al. 2018a).

Also of interest is functional 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (fMRS), which measures the dynamic change in the 1H-MRS metabolite signal occurring in response to a stimulus. Glutamate fMRS studies have detected stimulus-induced increases averaging 7% across experimental designs, and to the order of 13% in event-related studies (Mullins 2018). The greater magnitude of change detected in event-related compared to stimulus-block designs may relate to the relative rapidity of glutamate dynamics within the timeframe of the stimulation block, during which habituation, adaptation or homeostatic processes may occur (Apsvalka et al. 2015; Jelen et al. 2018). There are several potential explanations for magnitude of change in the fMRS signal, including increases in glutamate production from glucose oxidative metabolism (Mangia et al. 2007), compartmental shifts in glutamate from less (presynaptic vesicles) to more (extracellular) MRS-visible pools (Jelen et al. 2018; Kauppinen et al. 1994; Mullins 2018) and influences of blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD)-like effects on the signal amplitude (Apsvalka et al. 2015; Jelen et al. 2018). Pharmacological modulation of glutamate dynamics using fMRS is yet to be investigated and will be an interesting area for future research.

While the studies included in this review have investigated 1H-MRS metabolites serially in single voxels, it is also possible to measure multiple voxels simultaneously using MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). While initially limited to the more easily detectable metabolites such as NAA, 1H-MRSI sequences are now available to measure Glx (Ding et al. 2015; Gasparovic et al. 2011; Steel et al. 2018), glutamate and glutamine (Goryawala et al. 2016; Henning et al. 2009) and GABA (Moser et al. 2019) across large volumes of interest or the whole brain with a feasibly short acquisition time. Within psychiatric disorders, 1H-MRSI is therefore able to map the spatial distribution of metabolite abnormalities, which could provide richer regional information for future drug development. Finally, glutamate drug development could exploit the recent MRI technique of glutamate chemical exchange saturation transfer (GluCEST) (Cai et al. 2012), which has greater sensitivity, spatial and temporal for glutamate measurement than 1H-MRS.

1H-MRS studies in rodents are usually limited by the necessary use of anaesthesia to reduce stress to the animal and movement in the scanner, which will affect several aspects of brain physiology including metabolite concentrations (Makaryus et al. 2011) and could lead to divergence between results of preclinical and clinical studies. Under a typical protocol, in vivo 1H-MRS scanning takes approximately 1 hour per rat and can be associated with high costs of preclinical MRI equipment access or purchase, meaning it is probably impractical for initial drug screening. For a simple between-subjects group comparison, Waschkies et al. (2014) estimate that eight animals per group are required to detect a 6% change in glutamate, 12% change in GABA or 16% in glutamine (power = 80%; α = 5%), which is comparable to group sizes commonly required for invasive metabolite measurement. The authors also report good consistency of 1H-MRS measurement over time and across different batches of animals (Waschkies et al. 2014), which should be also established in other laboratories employing preclinical 1H-MRS. Despite the higher MR field strengths available for preclinical studies, the small voxel sizes required in relation to the rodent brain can limit detection of less abundant metabolites.

For human studies, participation in 1H-MRS requires that volunteers meet standard MRI inclusion criteria, such as an absence of implanted metallic objects. Typically, a 1H-MRS data acquisition to measure glutamate in a single voxel of ~ 8 ml would take about 10 minutes, with smaller voxels requiring longer acquisition times to obtain an equivalent signal to noise ratio. The short length of scan can generally be well tolerated by most individuals and patient groups. 1H-MRS data can be acquired as part of a set of MRI acquisition sequences, for example permitting MRS metabolite data to be investigated in relation to brain resting or functional activity during the same session. As mentioned above, it may be that multimodal imaging data could provide more reliable or accurate estimates for target engagement or patient stratification, as well as providing more comprehensive information on drug mechanism, and application of 1H-MRS to larger clinical studies across several study sites will benefit from protocol standardisation and evaluation of both inter- and intra-site reliability. Finally, with the availability of higher field strength MRI scanners for human research studies, it becomes increasingly possible to resolve lower concentration metabolites such as GABA or glutathione and separate glutamate and glutamine resonances under optimal acquisition sequences.

Conclusion

There has been a growing interest in applying 1H-MRS to CNS drug discovery, including in the development of glutamate-acting compounds for psychiatric disorders. A key advantage of 1H-MRS is that it is a non-invasive technique that can directly translate findings from rodents to man using the same imaging biomarker which can be acquired repeatedly within subjects. An increasing number of experiments across species indicate that 1H-MRS has sensitivity to measure the predicted pharmacological effects of glutamatergic and GABAergic compounds at clinically relevant doses, and there are early indications that some 1H-MRS metabolite measures may contribute to identifying patient subgroups for stratified approaches to clinical trials. This research would be assisted through further methodological studies to measure and improve the reliability and sensitivity of 1H-MRS metabolite measurements, especially for multicentre application. On-going technological and methodological development, including high field strength MRI, optimised acquisition sequences, 13C-MRS and fMRS, may further support applications of MRS in CNS drug discovery.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Anthony Vernon at King’s College London kindly provided the representative 1H-MRS spectra in the rat brain shown in Fig. 1.

Funding information

This review relates to work performed under UK Medical Research Council (MRC) grant MR/L003988/1 and is also supported in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the NHS, NIHR or Department of Health.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article belongs to a Special Issue on Imaging for CNS drug development and biomarkers.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdallah CG, De Feyter HM, Averill LA, Jiang L, Averill CL, Chowdhury GMI, Purohit P, de Graaf RA, Esterlis I, Juchem C, Pittman BP, Krystal JH, Rothman DL, Sanacora G, Mason GF. The effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate neurotransmission in healthy and depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2154–2160. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, Krystal JH. The neurobiology of depression, ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: is it glutamate inhibition or activation? Pharmacol Ther. 2018;190:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajram LA, Horder J, Mendez MA, Galanopoulos A, Brennan LP, Wichers RH, Robertson DM, Murphy CM, Zinkstok J, Ivin G, Heasman M, Meek D, Tricklebank MD, Barker GJ, Lythgoe DJ, Edden RAE, Williams SC, Murphy DGM, McAlonan GM. Shifting brain inhibitory balance and connectivity of the prefrontal cortex of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1137. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apsvalka D, Gadie A, Clemence M, Mullins PG. Event-related dynamics of glutamate and BOLD effects measured using functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (fMRS) at 3T in a repetition suppression paradigm. Neuroimage. 2015;118:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyannur PS, Arun P, Barry ES, Andrews-Shigaki B, Bosomtwi A, Tang H, Selwyn R, Grunberg NE, Moffett JR, Namboodiri AM. Do reductions in brain N-acetylaspartate levels contribute to the etiology of some neuropsychiatric disorders? J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:934–942. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagory M, Durand-Dubief F, Ibarrola D, Comte JC, Cotton F, Confavreux C, Sappey-Marinier D. Implementation of an absolute brain 1H-MRS quantification method to assess different tissue alterations in multiple sclerosis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:2687–2694. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2161609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron R, Imamura Y, Frangioni JV, Greene RW, Coyle JT. Endogenous N-acetylaspartylglutamate reduced NMDA receptor-dependent current neurotransmission in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2007;100:346–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Irvine RF. Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature. 1989;341:197–205. doi: 10.1038/341197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojesen KB, Andersen KA, Rasmussen SN, Baandrup L, Madsen LM, Glenthoj BY, Rostrup E, Broberg BV. Glutamate levels and resting cerebral blood flow in anterior cingulate cortex are associated at rest and immediately following infusion of S-ketamine in healthy volunteers. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:22. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D. Multinuclear NMR studies on the energy metabolism of glial and neuronal cells. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:289–298. doi: 10.1159/000111347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan BP, Hudson JI, Jensen JE, McCarthy J, Roberts JL, Prescot AP, Cohen BM, Pope HG, Jr, Renshaw PF, Ongur D. Rapid enhancement of glutamatergic neurotransmission in bipolar depression following treatment with riluzole. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:834–846. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan BP, Admon R, Perriello C, LaFlamme EM, Athey AJ, Pizzagalli DA, Hudson JI, Pope HG, Jr, Jensen JE. Acute change in anterior cingulate cortex GABA, but not glutamine/glutamate, mediates antidepressant response to citalopram. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;269:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugger S, Davis JM, Leucht S, Stone JM. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and illness stage in schizophrenia--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustillo JR, Rowland LM, Mullins P, Jung R, Chen H, Qualls C, Hammond R, Brooks WM, Lauriello J (2010) (1)H-MRS at 4 Tesla in minimally treated early schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 629–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bustillo JR, Rediske N, Jones T, Rowland LM, Abbott C, Wijtenburg SA. Reproducibility of phase rotation stimulated echo acquisition mode at 3T in schizophrenia: emphasis on glutamine. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:498–502. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano SC, Fonseca M, Olvera RL, Nicoletti M, Hatch JP, Stanley JA, Hunter K, Lafer B, Pliszka SR, Soares JC. Proton spectroscopy study of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in pediatric depressed patients. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, Kogan F, Greenberg JH, Hariharan H, Detre JA, Reddy R. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18:302–306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Lee PL, Yiannoutsos CT, Ernst T, Marra CM, Richards T, Kolson D, Schifitto G, Jarvik JG, Miller EN, Lenkinski R, Gonzalez G, Navia BA, Consortium HM. A multicenter in vivo proton-MRS study of HIV-associated dementia and its relationship to age. Neuroimage. 2004;23:1336–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Munsaka SM, Kraft-Terry S, Ernst T. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to assess neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:576–593. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Kadosh K, Krause B, King AJ, Near J, Cohen Kadosh R. Linking GABA and glutamate levels to cognitive skill acquisition during development. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4334–4345. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colic L, Li M, Demenescu LR, Li S, Muller I, Richter A, Behnisch G, Seidenbecher CI, Speck O, Schott BH, Stork O, Walter M. GAD65 promoter polymorphism rs2236418 modulates harm avoidance in women via inhibition/excitation balance in the rostral ACC. J Neurosci. 2018;38:5067–5077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1985-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conus P, Seidman LJ, Fournier M, Xin L, Cleusix M, Baumann PS, Ferrari C, Cousins A, Alameda L, Gholam-Rezaee M, Golay P, Jenni R, Woo TW, Keshavan MS, Eap CB, Wojcik J, Cuenod M, Buclin T, Gruetter R, Do KQ. N-acetylcysteine in a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial: toward biomarker-guided treatment in early psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:317–327. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- das Neves Duarte JM, Kulak A, Gholam-Razaee MM, Cuenod M, Gruetter R, Do KQ. N-acetylcysteine normalizes neurochemical changes in the glutathione-deficient schizophrenia mouse model during development. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Tanious M, Fritz K, Dodd S, Dean OM, Berk M, Malhi GS. Metabolite profiles in the anterior cingulate cortex of depressed patients differentiate those taking N-acetyl-cysteine versus placebo. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:347–354. doi: 10.1177/0004867412474074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf RA, Patel AB, Rothman DL, Behar KL. Acute regulation of steady-state GABA levels following GABA-transaminase inhibition in rat cerebral cortex. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Leon-Ortiz P, Azcarraga M, Stephano S, Favila R, Diaz-Galvis L, Alvarado-Alanis P, Ramirez-Bermudez J, Graff-Guerrero A. Glutamate levels in the associative striatum before and after 4 weeks of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1057–1066. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XQ, Maudsley AA, Sabati M, Sheriff S, Dellani PR, Lanfermann H. Reproducibility and reliability of short-TE whole-brain MR spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:921–928. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JM, Lei H, Mlynarik V, Gruetter R. The neurochemical profile quantified by in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy. Neuroimage. 2012;61:342–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux AM, Fernandes C, Murphy D, Labouesse MA, Giovanoli S, Meyer U, Li Q, So PW, McAlonan G. Targeting glia with N-acetylcysteine modulates brain glutamate and behaviors relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders in C57BL/6J mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:343. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edden RA, Pomper MG, Barker PB. In vivo differentiation of N-acetyl aspartyl glutamate from N-acetyl aspartate at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:977–982. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton A, Broberg BV, Van Haren N, Merritt K, Barker GJ, Lythgoe DJ, Perez-Iglesias R, Baandrup L, During SW, Sendt KV, Stone JM, Rostrup E, Sommer IE, Glenthoj B, Kahn RS, Dazzan P, McGuire P. Response to initial antipsychotic treatment in first episode psychosis is related to anterior cingulate glutamate levels: a multicentre (1)H-MRS study (OPTiMiSE) Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:2145–2155. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JW, Lally N, An L, Li N, Nugent AC, Banerjee D, Snider SL, Shen J, Roiser JP, Zarate CA., Jr 7T (1)H-MRS in major depressive disorder: a ketamine treatment study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1908–1914. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri F, Nikolova YS, Perrucci MG, Costantini M, Ferretti A, Gatta V, Huang Z, Edden RAE, Yue Q, D'Aurora M, Sibille E, Stuppia L, Romani GL, Northoff G. A neural “tuning curve” for multisensory experience and cognitive-perceptual Schizotypy. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:801–813. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss-Feig JH, Adkinson BD, Ji JL, Yang G, Srihari VH, McPartland JC, Krystal JH, Murray JD, Anticevic A. Searching for cross-diagnostic convergence: neural mechanisms governing excitation and inhibition balance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:848–861. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Hinton DJ, Karpyak VM, Biernacka JM, Gunderson LJ, Feeder SE, Choi DS, Port JD. Anterior cingulate glutamate is reduced by Acamprosate treatment in patients with alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:669–674. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparovic C, Bedrick EJ, Mayer AR, Yeo RA, Chen H, Damaraju E, Calhoun VD, Jung RE. Test-retest reliability and reproducibility of short-echo-time spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:324–332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis RR, Baker S, Mao X, Gil R, Javitt DC, Kantrowitz JT, Gu M, Spielman DM, Ojeil N, Xu X, Abi-Dargham A, Shungu DC, Kegeles LS. Effects of acute N-acetylcysteine challenge on cortical glutathione and glutamate in schizophrenia: a pilot in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Psychiatry Res. 2019;275:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlewska BR, Emir UE, Masaki C, Bargiotas T, Cowen PJ. Changes in brain Glx in depressed bipolar patients treated with lamotrigine: a proton MRS study. J Affect Disord. 2018;246:418–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC. Drug development in schizophrenia: are glutamatergic targets still worth aiming at? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:207–215. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Hennen J, Lyoo IK, Tsai G, Wald LL, Evins AE, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Renshaw PF (2002) Modulation of brain and serum glutamatergic concentrations following a switch from conventional neuroleptics to olanzapine. Biol Psychiatry 51 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Goryawala MZ, Sheriff S, Maudsley AA. Regional distributions of brain glutamate and glutamine in normal subjects. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1108–1116. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber S, Ametamey SM. Imaging the glutamate receptor subtypes-much achieved, and still much to do. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2017;25:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Hu Y, Chen X, He Y, Yang Y. Regional excitation-inhibition balance predicts default-mode network deactivation via functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2019;185:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancu I. Optimized glutamate detection at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JL, Choi IY, Brooks WM. Probing astrocyte metabolism in vivo: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the injured and aging brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:202. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AD, Saleh MG, Edden RA. Edited (1) H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo: methods and metabolites. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:1377–1389. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning A, Fuchs A, Murdoch JB, Boesiger P. Slice-selective FID acquisition, localized by outer volume suppression (FIDLOVS) for (1)H-MRSI of the human brain at 7 T with minimal signal loss. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:683–696. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iltis I, Koski DM, Eberly LE, Nelson CD, Deelchand DK, Valette J, Ugurbil K, Lim KO, Henry PG. Neurochemical changes in the rat prefrontal cortex following acute phencyclidine treatment: an in vivo localized (1)H MRS study. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:737–744. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janik R, Thomason LAM, Stanisz AM, Forsythe P, Bienenstock J, Stanisz GJ. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals oral Lactobacillus promotion of increases in brain GABA, N-acetyl aspartate and glutamate. Neuroimage. 2016;125:988–995. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Carter CS, Krystal JH, Kantrowitz JT, Girgis RR, Kegeles LS, Ragland JD, Maddock RJ, Lesh TA, Tanase C, Corlett PR, Rothman DL, Mason G, Qiu M, Robinson J, Potter WZ, Carlson M, Wall MM, Choo TH, Grinband J, Lieberman JA. Utility of imaging-based biomarkers for glutamate-targeted drug development in psychotic disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:11–19. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelen LA, King S, Mullins PG, Stone JM (2018) Beyond static measures: a review of functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy and its potential to investigate dynamic glutamatergic abnormalities in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol 269881117747579 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jessen F, Fingerhut N, Sprinkart AM, Kuhn KU, Petrovsky N, Maier W, Schild HH, Block W, Wagner M, Traber F (2011) N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanamori K, Ross BD, Kondrat RW. Glial uptake of neurotransmitter glutamate from the extracellular fluid studied in vivo by microdialysis and (13)C NMR. J Neurochem. 2002;83:682–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Milak MS, Mao X, Shungu DC, Mann JJ. D-Cycloserine, an NMDA glutamate receptor glycine site partial agonist, induces acute increases in brain glutamate plus glutamine and GABA comparable to ketamine. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:1241–1242. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16060735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MJ, Prescot AP, Ongur D, Evins AE, Barros TL, Medeiros CL, Covell J, Wang L, Fava M, Renshaw PF (2009) Oral glycine administration increases brain glycine/creatine ratios in men: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Psychiatry Res 173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kauppinen RA, Pirttila TR, Auriola SO, Williams SR. Compartmentation of cerebral glutamate in situ as detected by 1H/13C n.m.r. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 1):121–127. doi: 10.1042/bj2980121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khacho P, Wang B, Ahlskog N, Hristova E, Bergeron R. Differential effects of N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate on synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are subunit- and pH-dependent in the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;82:580–592. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Lee H, Kim HJ, Bang E, Lee SH, Lee DW, Woo DC, Choi CB, Hong KS, Lee C, Choe BY. In vivo and ex vivo evidence for ketamine-induced hyperglutamatergic activity in the cerebral cortex of the rat: potential relevance to schizophrenia. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1235–1242. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Kaufman MJ, Cohen BM, Jensen JE, Coyle JT, Du F, Ongur D (2017) In vivo brain glycine and glutamate concentrations in patients with first-episode psychosis measured by echo time-averaged proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 4T. Biol Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kirov II, Patil V, Babb JS, Rusinek H, Herbert J, Gonen O. MR spectroscopy indicates diffuse multiple sclerosis activity during remission. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1330–1336. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.176263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraguljac NV, Reid M, White D, Jones R, den Hollander J, Lowman D, Lahti AC. Neurometabolites in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraguljac NV, Frolich MA, Tran S, White DM, Nichols N, Barton-McArdle A, Reid MA, Bolding MS, Lahti AC. Ketamine modulates hippocampal neurochemistry and functional connectivity: a combined magnetic resonance spectroscopy and resting-state fMRI study in healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:562–569. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landim RC, Edden RA, Foerster B, Li LM, Covolan RJ, Castellano G. Investigation of NAA and NAAG dynamics underlying visual stimulation using MEGA-PRESS in a functional MRS experiment. Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;34:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Kim SY, Woo DC, Choe BY, Ryu KN, Choi WS, Jahng GH, Yim SV, Kim HY, Choi CB. Differential neurochemical responses of the canine striatum with pentobarbital or ketamine anesthesia: a 3T proton MRS study. J Vet Med Sci. 2010;72:583–587. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. The glycinergic inhibitory synapse. Cell Mol Life Sci: CMLS. 2001;58:760–793. doi: 10.1007/PL00000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Demenescu LR, Colic L, Metzger CD, Heinze HJ, Steiner J, Speck O, Fejtova A, Salvadore G, Walter M. Temporal dynamics of antidepressant ketamine effects on glutamine cycling follow regional fingerprints of AMPA and NMDA receptor densities. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:1201–1209. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makaryus R, Lee H, Yu M, Zhang S, Smith SD, Rebecchi M, Glass PS, Benveniste H. The metabolomic profile during isoflurane anesthesia differs from propofol anesthesia in the live rodent brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1432–1442. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangia S, Tkac I, Gruetter R, Van de Moortele PF, Maraviglia B, Ugurbil K. Sustained neuronal activation raises oxidative metabolism to a new steady-state level: evidence from 1H NMR spectroscopy in the human visual cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE (2011) Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McQueen G, Lally J, Collier T, Zelaya F, Lythgoe DJ, Barker GJ, Stone JM, McGuire P, MacCabe JH, Egerton A. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on brain glutamate levels and resting perfusion in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:3045–3054. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4997-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekle R, Mlynarik V, Gambarota G, Hergt M, Krueger G, Gruetter R. MR spectroscopy of the human brain with enhanced signal intensity at ultrashort echo times on a clinical platform at 3T and 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1279–1285. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt K, Egerton A, Kempton MJ, Taylor MJ, McGuire PK. Nature of glutamate alterations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:665–674. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milak MS, Proper CJ, Mulhern ST, Parter AL, Kegeles LS, Ogden RT, Mao X, Rodriguez CI, Oquendo MA, Suckow RF, Cooper TB, Keilp JG, Shungu DC, Mann JJ. A pilot in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of amino acid neurotransmitter response to ketamine treatment of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:320–327. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Namboodiri AM. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: from neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. ProgNeurobiol. 2007;81:89–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Javitt D. From revolution to evolution: the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia and its implication for treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:4–15. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D (1997) Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: a novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moriguchi S, Takamiya A, Noda Y, Horita N, Wada M, Tsugawa S, Plitman E, Sano Y, Tarumi R, ElSalhy M, Katayama N, Ogyu K, Miyazaki T, Kishimoto T, Graff-Guerrero A, Meyer JH, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ, Mimura M, Nakajima S (2018) Glutamatergic neurometabolite levels in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Mol Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moser P, Hingerl L, Strasser B, Povazan M, Hangel G, Andronesi OC, van der Kouwe A, Gruber S, Trattnig S, Bogner W. Whole-slice mapping of GABA and GABA(+) at 7T via adiabatic MEGA-editing, real-time instability correction, and concentric circle readout. Neuroimage. 2019;184:475–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins PG. Towards a theory of functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (fMRS): a meta-analysis and discussion of using MRS to measure changes in neurotransmitters in real time. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59:91–103. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins PG, Chen H, Xu J, Caprihan A, Gasparovic C. Comparative reliability of proton spectroscopy techniques designed to improve detection of J-coupled metabolites. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:964–969. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JF, Evans CJ, Kalk NJ, Edden RA, Lingford-Hughes AR. Measurement of GABA using J-difference edited 1H-MRS following modulation of synaptic GABA concentration with tiagabine. Synapse. 2014;68:355–362. doi: 10.1002/syn.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano A, Shah K, Schubert MI, Porkess V, Fone KC, Auer DP. In vivo neurometabolic profiling to characterize the effects of social isolation and ketamine-induced NMDA antagonism: a rodent study at 7.0 T. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:566–574. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale JH, Olszewski RT, Zuo D, Janczura KJ, Profaci CP, Lavin KM, Madore JC, Bzdega T. Advances in understanding the peptide neurotransmitter NAAG and appearance of a new member of the NAAG neuropeptide family. J Neurochem. 2011;118:490–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman Tuura R, Warnock G, Ametamey S, Treyer V, Noeske R, Buck A, Sommerauer M. Imaging glutamate redistribution after acute N-acetylcysteine administration: a simultaneous PET/MR study. Neuroimage. 2019;184:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski RT, Bukhari N, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Wroblewski JT, Shamimi-Noori S, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, Vicini S, Barton FB, Neale JH. NAAG peptidase inhibition reduces locomotor activity and some stereotypes in the PCP model of schizophrenia via group II mGluR. J Neurochem. 2004;89:876–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AB, de Graaf RA, Martin DL, Battaglioli G, Behar KL. Evidence that GAD65 mediates increased GABA synthesis during intense neuronal activity in vivo. J Neurochem. 2006;97:385–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuffer J, Tkac I, Provencher SW, Gruetter R. Toward an in vivo neurochemical profile: quantification of 18 metabolites in short-echo-time (1)H NMR spectra of the rat brain. J Magn Reson. 1999;141:104–120. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillinger T, Rogdaki M, McCutcheon RA, Hathway P, Egerton A, Howes OD. Altered glutamatergic response and functional connectivity in treatment resistant schizophrenia: the effect of riluzole and therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology. 2019;236:1985–1997. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-5188-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plitman E, de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Reyes-Madrigal F, Chavez S, Gomez-Cruz G, Leon-Ortiz P, Graff-Guerrero A. Elevated myo-inositol, choline, and glutamate levels in the associative striatum of antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study with implications for glial dysfunction. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:415–424. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescot AP, de Frederick B, Wang L, Brown J, Jensen JE, Kaufman MJ, Renshaw PF. In vivo detection of brain glycine with echo-time-averaged (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 4.0 T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:681–686. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts NA, Edden RA. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy of GABA: a methodological review. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2012;60:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo F, Abaei A, Nespoli E, Fegert JM, Hengerer B, Rasche V, Boeckers TM. Aripiprazole and Riluzole treatment alters behavior and neurometabolites in young ADHD rats: a longitudinal (1)H-NMR spectroscopy study at 11.7T. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1189. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, Ogden RT, Mao X, Milak MS, Vermes D, Xie S, Hunter L, Flood P, Moore H, Shungu DC, Simpson HB. In vivo effects of ketamine on glutamate-glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof of concept. Psychiatry Res. 2015;233:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman DL, Sibson NR, Hyder F, Shen J, Behar KL, Shulman RG (1999) In vivo nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of the relationship between the glutamate-glutamine neurotransmitter cycle and functional neuroenergetics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rothman DL, De Feyter HM, de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Behar KL. 13C MRS studies of neuroenergetics and neurotransmitter cycling in humans. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:943–957. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LM, Bustillo JR, Mullins PG, Jung RE, Lenroot R, Landgraf E, Barrow R, Yeo R, Lauriello J, Brooks WM (2005) Effects of ketamine on anterior cingulate glutamate metabolism in healthy humans: a 4-T proton MRS study. Am J Psychiatry 162 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rowland LM, Kontson K, West J, Edden RA, Zhu H, Wijtenburg SA, Holcomb HH, Barker PB. In vivo measurements of glutamate, GABA, and NAAG in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1096–1104. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LM, Demyanovich HK, Wijtenburg SA, Eaton WW, Rodriguez K, Gaston F, Cihakova D, Talor MV, Liu F, McMahon RR, Hong LE, Kelly DL. Antigliadin antibodies (AGA IgG) are related to neurochemistry in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:104. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadore G, van der Veen JW, Zhang Y, Marenco S, Machado-Vieira R, Baumann J, Ibrahim LA, Luckenbaugh DA, Shen J, Drevets WC, Zarate CA., Jr An investigation of amino-acid neurotransmitters as potential predictors of clinical improvement to ketamine in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:1063–1072. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanaei Nezhad F, Anton A, Michou E, Jung J, Parkes LM, Williams SR (2018) Quantification of GABA, glutamate and glutamine in a single measurement at 3 T using GABA-edited MEGA-PRESS. NMR Biomed 31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, Nederveen A, van den Brink W, Goudriaan AE. N-acetylcysteine normalizes glutamate levels in cocaine-dependent patients: a randomized crossover magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2143–2152. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte M, Goudriaan AE, Kaag AM, Kooi DP, van den Brink W, Wiers RW, Schmaal L. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on brain glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid concentrations and on smoking cessation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:1377–1379. doi: 10.1177/0269881117730660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerk A, Alves FD, Pouwels PJ, van Amelsvoort T. Metabolic alterations associated with schizophrenia: a critical evaluation of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. J Neurochem. 2014;128:1–87. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar S, Grandjean J, Garnell JF, Willems R, Duytschaever H, Seramani S, Su H, Ver Donck L, Bhakoo KK. Neuro-metabolite profiles of rodent models of psychiatric dysfunctions characterised by MR spectroscopy. Neuropharmacology. 2018;146:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servaes S, Kara F, Glorie D, Stroobants S, Van Der Linden A, Staelens S. In vivo preclinical molecular imaging of repeated exposure to an N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist and a glutaminase inhibitor as potential glutamatergic modulators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;368:382–390. doi: 10.1124/jpet.118.252635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibson NR, Dhankhar A, Mason GF, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. In vivo 13C NMR measurements of cerebral glutamine synthesis as evidence for glutamate-glutamine cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2699–2704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibson NR, Mason GF, Shen J, Cline GW, Herskovits AZ, Wall JE, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. In vivo (13)C NMR measurement of neurotransmitter glutamate cycling, anaplerosis and TCA cycle flux in rat brain during. J Neurochem. 2001;76:975–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Wilman A (2010) Field strength dependence of PRESS timings for simultaneous detection of glutamate and glutamine from 1.5 to 7T. J Magn Reson 203 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Steel A, Chiew M, Jezzard P, Voets NL, Plaha P, Thomas MA, Stagg CJ, Emir UE. Metabolite-cycled density-weighted concentric rings k-space trajectory (DW-CRT) enables high-resolution 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging at 3-Tesla. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7792. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26096-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JM, Dietrich C, Edden R, Mehta MA, De SS, Reed LJ, Krystal JH, Nutt D, Barker GJ. Ketamine effects on brain GABA and glutamate levels with 1H-MRS: relationship to ketamine-induced psychopathology. MolPsychiatry. 2012;17:664–665. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Patel NC, Chu WJ, Lee JH, Adler CM, Kim MJ, Bryan HS, Alfieri DC, Welge JA, Blom TJ, Nandagopal JJ, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. Glutamatergic effects of divalproex in adolescents with mania: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecki D, Podgorski M, Kaluzynska O, Gawlik-Kotelnicka O, Stefanczyk L, Kotlicka-Antczak M, Gmitrowicz A, Grzelak P. Supplementation of antipsychotic treatment with sarcosine - GlyT1 inhibitor - causes changes of glutamatergic (1)NMR spectroscopy parameters in the left hippocampus in patients with stable schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2015;606:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]