Abstract

Programmed cell death (PCD) plays a crucial role in preventing cancer initiation and progression. Among the diverse PCD pathways, cuproptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis have garnered attention for their unique mechanisms, which not only directly eliminate tumor cells but also enhance anti-tumor immunity. However, the therapeutic efficacy of PCD inducers is often compromised by rapid compensatory pathways in tumor cells, accelerated drug metabolism, and a lack of specificity, which can result in severe side effects. Engineered nanomedicines offer distinct advantages by leveraging nanoscale physicochemical properties to optimize pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety in cancer therapy. These nanomedicines enable precise targeting of tumor cells while enhancing drug stability. Moreover, they can simultaneously activate multiple PCD pathways and integrate with conventional therapies to further amplify anti-tumor effects. This review systematically examines the pathophysiological roles, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications of cuproptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis in cancer treatment, with an emphasis on their modulation by nanomedicines. It also explores the potential interactions among these PCD pathways and highlights recent advancements in nanomedicine-based combination therapies targeting multiple PCD mechanisms. Finally, the challenges, limitations, and prospects for the clinical translation and application of PCD-targeting nanomedicines are discussed.

Keywords: Programmed cell death, Biomaterial, Nanomedicine, Cuproptosis, Pyroptosis, Ferroptosis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Systematic analysis of pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and cuproptosis and their relevance in cancer therapy.

-

•

Highlights synergistic regulation among PCD pathways to enhance efficacy of multi-targeted cancer therapies.

-

•

Explores nanomedicine strategies to modulate PCD pathways and improve therapeutic precision and outcomes.

1. Introduction

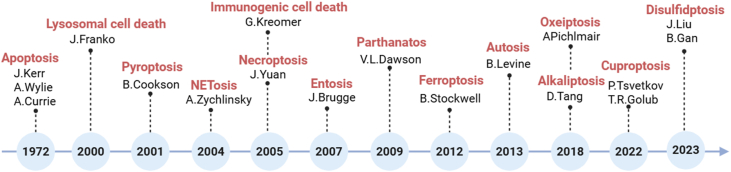

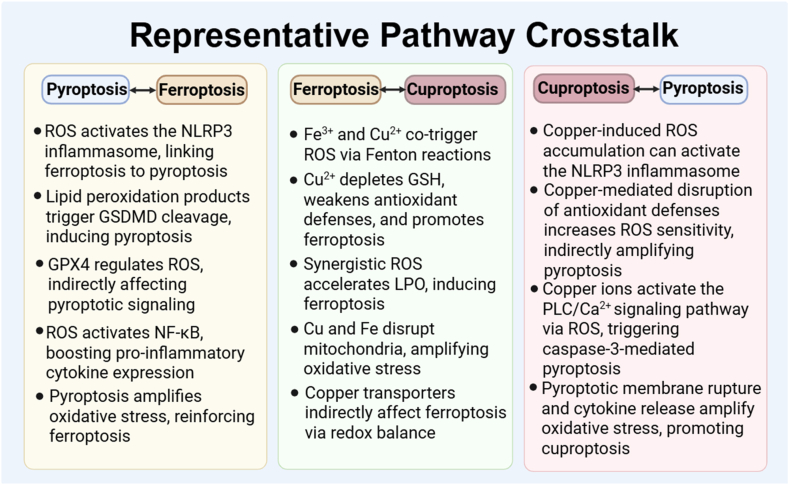

Programmed cell death (PCD) refers to a tightly regulated biological process through which cells undergo self-destruction in response to specific internal or external signals, thereby ensuring tissue homeostasis and organismal integrity [1]. Since the identification of apoptosis in 1972 as the first and most well-characterized form of PCD, research in this field has significantly expanded. A growing number of PCD subtypes have been discovered, including autophagy, pyroptosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis, and more recently, cuproptosis and alkaliptosis. Each type is distinguished by unique molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways, and they collectively contribute to a wide range of physiological processes and disease contexts, particularly cancer [2,3]. PCD processes are deeply implicated in cancer biology, where they influence tumor initiation, progression, immune escape, and resistance to therapy [4,5]. Importantly, the historical progression of PCD discovery also reflects the evolving understanding of cell death mechanisms [6,7]. A chronological summary of each PCD subtype's identification and major milestones are presented (Fig. 1), alongside a comparative overview of their biological functions and antitumor roles (Table 1). Certain PCD pathways can also activate the immune system [4]. When tumor cells die via specific PCD mechanisms, antigens and inflammatory mediators are released and recognized by the immune system, triggering an anti-tumor immune response [8]. Moreover, PCD influences the immune response in the tumor microenvironment (TME) to inhibit metastasis, which remains one of the most challenging aspects of cancer treatment [9,10]. By impairing the migratory capacity of tumor cells, PCD can significantly suppress the invasive growth of tumor [9]. For instance, pyroptosis, with its strong immunogenicity, is particularly effective at stimulating the immune system to clear tumor cells [11]. However, tumor cells frequently develop resistance to treatment by altering these death pathways or activating immune escape mechanisms, leading to diminished therapeutic efficacy [12]. Importantly, there is significant crosstalk among different PCD pathways. For instance, cuproptosis and ferroptosis have strong regulatory links that can jointly influence the tumor microenvironment and help predict patient prognosis [13]. Moreover, ferroptosis-related elements such as Fe2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-inducing agents can also trigger pyroptosis through specific signaling pathways [14]. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the complex roles of PCD in cancer and the underlying mechanisms involved is essential for optimizing treatment strategies.

Fig. 1.

Chronology of the discovery of various PCD types. Created in BioRender. Zhang, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a1uy4vz.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of classical and emerging PCD pathways.

| PCD Type | Causative Agents | Molecular Markers | Representative Inhibitors | Morphological Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | Radiation, chemicals, viruses, growth factor deprivation | Caspase-3, Caspase-9, Annexin V, cleaved PARP | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor), Emricasan, Q-VD-OPh | Cell shrinkage Chromatin condensation Plasma membrane blebbing without rupture Formation of apoptotic bodies, cytoskeletal disintegration |

| Necroptosis | Toxins, hypoxia, physical damage, complement activation | RIPK1, RIPK3, pMLKL | Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor), GSK'872, NSA | Cytoplasm and organelles swelling Formation of necrosome Plasma membrane rupture Release of cell contents |

| Autophagy | Nutrient starvation, hypoxia, mTOR inhibition | ATG genes, Beclin-1, LC3-II, p62 | 3-MA, Wortmannin, Bafilomycin A1 | Formation of double-membraned autophagosomes Engulfment of cytoplasmic contents and organelles Fusion with lysosomes Intact nuclear morphology Preserved plasma membrane |

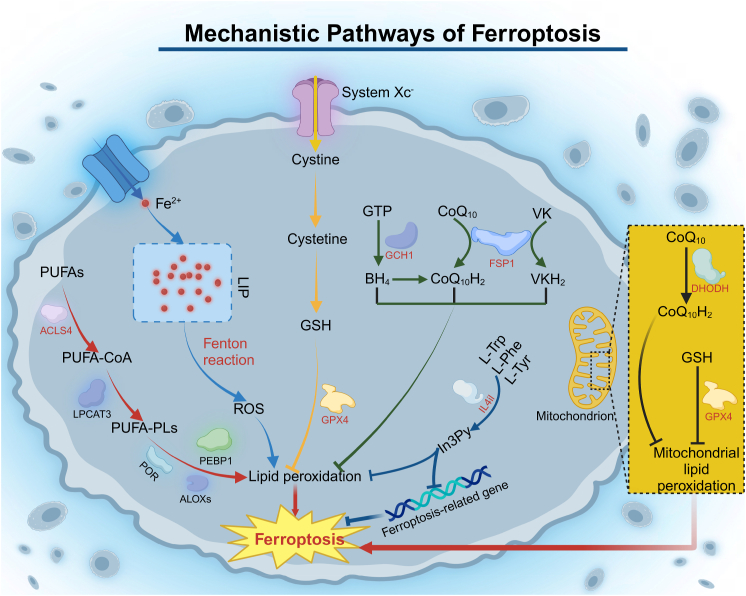

| Ferroptosis | Iron overload, ROS, Erastin, RSL3, GPX4 inhibition | GPX4, SLC7A11, ACSL4 | Ferrostatin-1, Liproxstatin-1, Deferoxamine (DFO) | Mitochondria shrinkage Increased mitochondria membrane density Crista destruction Outer membrane rupture |

| Pyroptosis | Bacterial infection, LPS, inflammasome activation | GSDMD, caspase-1, IL-1β | VX-765 (caspase-1 inhibitor), disulfiram, MCC950 | Cytoplasm swelling Formation of pyroptotic bodies Plasma membrane rupture Release of cell contents |

| Cuproptosis | Excess intracellular copper, elesclomol, FDX1 activation | FDX1, DLAT, lipoylated proteins | Tetrathiomolybdate (Cu chelator), BCS | Mitochondrial swelling Cristae loss Formation of electron-dense mitochondrial aggregates Nuclear morphology largely unchanged |

| Disulfidptosis | Cystine starvation, glucose starvation | SLC7A11, NADPH | NAC (antioxidant), disulfide scavengers, DTT, β-mercaptoethanol | Collapse of cytoskeletal structure F-actin contraction and detachment from the plasma membrane Leading to loss of cell shape Mitochondria and nuclei remain intact |

| Entosis | Cell detachment, stress | RhoA-ROCK, cadherins | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), Fasudil | Formation of “cell-in-cell” structures Inner cell is engulfed by a large vacuole in the host cell Host cell nucleus adopts a crescent shape Inner cell undergoes degradation within the vacuole |

| NETosis | Bacterial/viral infection | ROS, PAD4 | Cl-amidine (PAD4 inhibitor), GSK484 | Chromatin decondensation and nuclear swelling Nuclear membrane rupture Plasma membrane rupture Release of decondensed chromatin and granular proteins Formation of web-like neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) |

| Parthanatos | DNA damage, oxidative stress | PARP-1, PAR, AIF, MIF | Olaparib, PJ34 (PARP inhibitors) | Nuclear condensation Nuclear fragmentation Mitochondrial damage Chromatin marginalization |

| Lysosome-dependent Cell Death | Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) | Cathepsins | CA-074 Me (Cathepsin B inhibitor) | Lysosomal membrane permeabilization Cytoplasmic vacuolization Release of cathepsins Mitochondrial damage |

| Alkaliptosis | pH stress, JTC801 | NF-κB, JTC801, CA9 | Bafilomycin A1 (pH regulator) | Cytoplasmic alkalinization Plasma membrane destabilization Cell swelling |

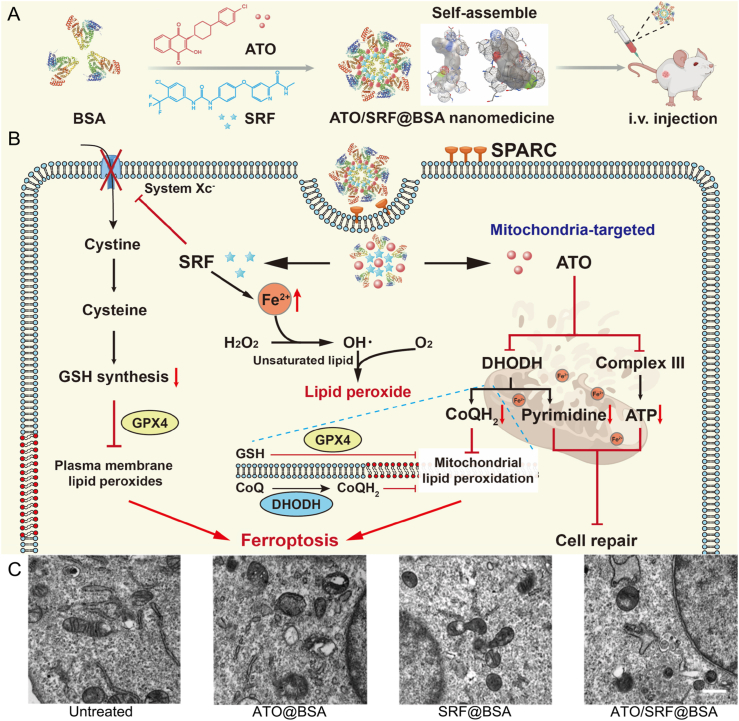

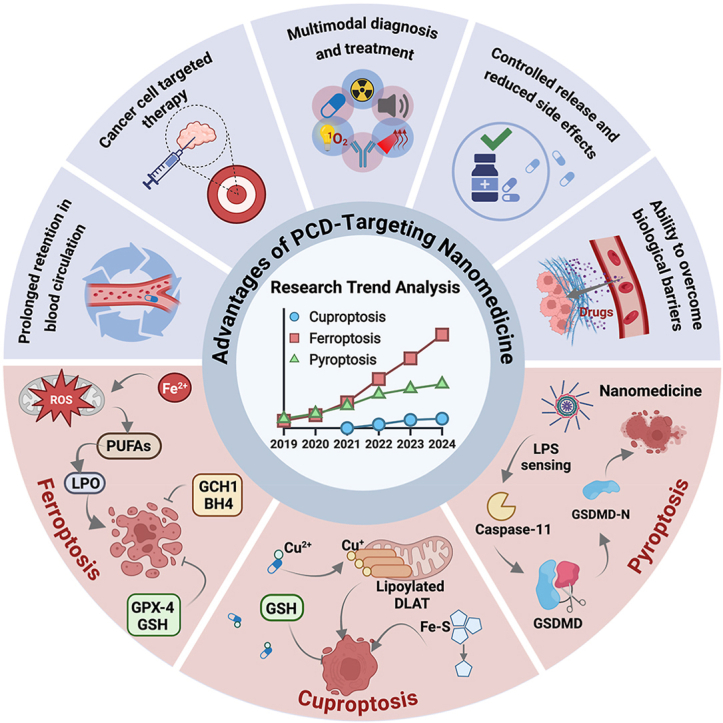

Recent progress in understanding PCD has drawn significant attention to ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and pyroptosis, which have quickly become prominent areas of research. Interest in these pathways continues to grow, driven by their potential roles in cancer development and treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that these distinct forms of cell death may offer valuable therapeutic strategies by influencing tumor initiation, progression, and response to therapy. Although traditional PCD inducers have shown promise in targeting cancer cells and improving treatment efficacy, they come with limitations, including significant side effects, the development of drug resistance, and poor targeting efficiency [15]. The emergence of nanomedicines presents an innovative approach to overcoming the challenges [[16], [17], [18]]. Nanomedicines are multifunctional and can enhance drug targeting, improve solubility, and reduce systemic side effects [[19], [20], [21]]. They can also work synergistically with different PCD pathways, offering precise control over drug release and ensuring targeted delivery to tumor cells [22]. Furthermore, nanomedicines can be combined with other therapeutic modalities such as photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), and radiotherapy to further boost efficacy [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. The combination approach provides exciting possibilities for the development of novel cancer therapies.

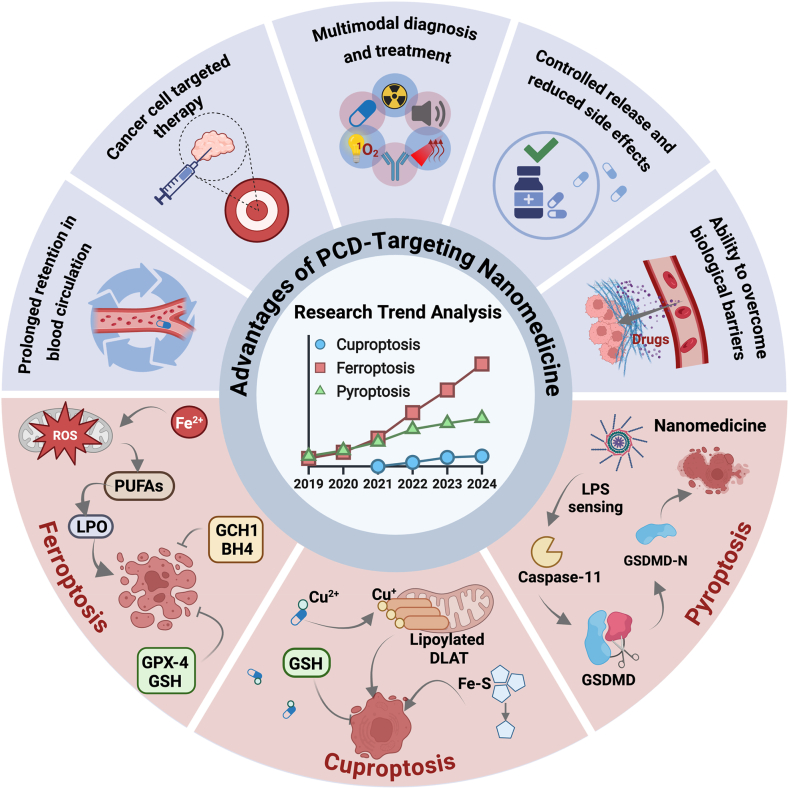

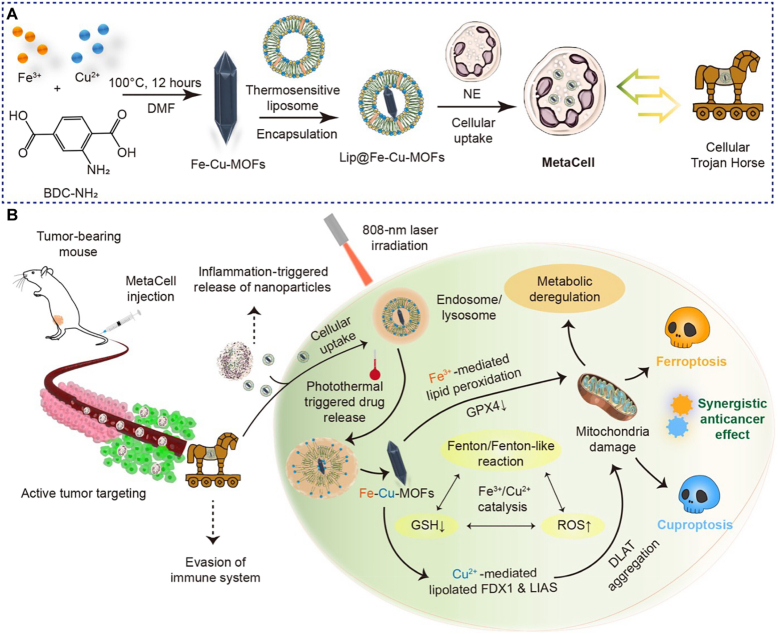

While previous reviews have often examined ferroptosis, cuproptosis, or pyroptosis in isolation, this review builds on that foundation by offering an integrated analysis of these three emerging forms of PCD and their relevance in cancer therapy. We highlight not only their individual mechanisms but also their potential interplay, emphasizing how these pathways can be strategically targeted using nanomedicine. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the most comprehensive and up-to-date summaries of the mechanistic foundations and translational applications of ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and pyroptosis in the context of cancer nanotherapy. This review begins by outlining the core molecular events and signaling pathways that drive each PCD type, with particular attention to the cascade-like amplification processes that characterize them. By identifying critical regulatory nodes within these pathways, we aim to uncover therapeutic targets for the rational design of nanomedicine-based interventions. We then examine the interplay among these PCD mechanisms and how their interactions influence tumor progression. Following this, we discuss how nanomedicine can be engineered to modulate these PCD pathways, thereby enhancing anticancer efficacy through targeted delivery and controlled activation. Finally, we provide an overview of the current clinical progress in nanomedicine-based cancer treatments, along with key challenges and future directions. Compared to previous literature, this review offers a more systematic and integrated perspective, providing a theoretical foundation for the development of next-generation cancer nanotherapies that exploit the synergistic potential of multiple PCD pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This review aims to thoroughly explore the mechanisms of ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and pyroptosis (three prominent forms of PCD) in tumor therapy, providing a theoretical foundation for identifying potential therapeutic targets and offering guidance for the design and development of PCD-targeting nanomedicines. Created in BioRender. Zhang, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ldqrajb.

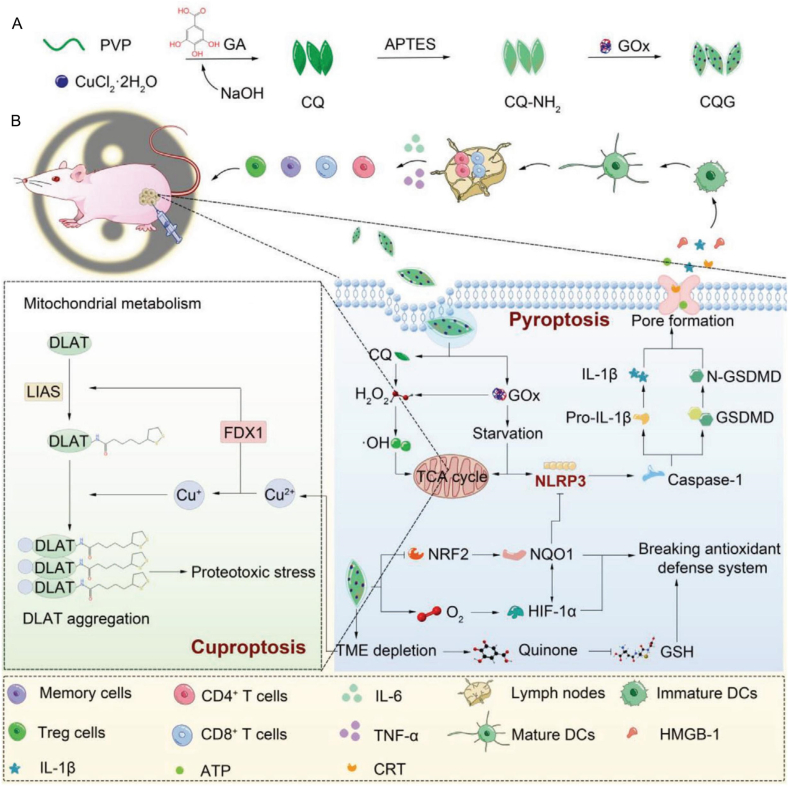

2. Introduction of cuproptosis

Copper is an important trace nutrient that supports various physiological processes, including hematopoiesis, connective tissue formation, and nervous system function [27,28]. It also acts as a catalytic co-factor for enzymes involved in energy metabolism, mitochondrial respiration, and antioxidant defense [29]. Therefore, maintaining copper homeostasis is crucial for sustaining normal physiological functions. Imbalance in copper homeostasis is associated with several diseases, such as cancer, Wilson's disease, Menke's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease [[30], [31], [32], [33], [34]]. Imbalance in copper homeostasis can lead to elevated intracellular copper levels, resulting in cellular damage and cuproptosis. Cuproptosis is a recently discovered form of PCD, first introduced by Peter Tsvetkov in 2022 [35]. Researchers initially discovered that copper ionophores induce cell death by causing abnormal intracellular copper accumulation [35]. This led to the identification of a novel form of regulated cell death, distinct from known pathways, now termed cuproptosis. Cuproptosis is associated with several distinct morphological changes, including mitochondrial shrinkage, cell membrane rupture, ER damage, and chromatin fragmentation. The mechanism of cuproptosis has been observed across multiple genetic models characterized by disrupted copper homeostasis, suggesting that cuproptosis is a broadly relevant cellular process [35]. Importantly, the regulatory framework of cuproptosis extends beyond copper metabolism alone. It also involves the lipoylation pathway, iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster biogenesis and regulation, and cellular stress response and proteostasis [[36], [37], [38], [39]]. Together, these modules form a complex regulatory network that orchestrates the initiation and execution of cuproptosis. In the following sections, we provide a detailed overview of these pathways and their mechanistic roles in cuproptosis.

2.1. The role of copper ions in cells

Copper is prevalent in biological tissues and serves as an indispensable element for maintaining various physiological functions [29]. Copper was primarily found in organic complexes, many of which are metalloproteins that act as enzymes [40]. A small fraction of copper exists in its free forms, mainly as cuprous ions (Cu+) and cupric ions (Cu2+) [41]. The representative biological functions of copper are as follows.

-

1.

Enzyme catalysis: copper serves as a vital cofactor for many important enzymes, including tyrosinase, cytochrome c oxidase (COX), and SOD [42]. The enzymes are integral to various metabolic activities, such as energy production, antioxidant defense, pigment synthesis, and neurotransmitter production [29].

-

2.

Energy metabolism: in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, copper is involved in electron transport, particularly within COX [32]. It facilitates the transfer of electrons to oxygen, promoting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and providing energy for cellular functions [43].

-

3.

Antioxidant defense: copper plays an important role in the body's antioxidant system, particularly through SOD, which helps convert harmful superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide [44]. The process reduces oxidative stress and protects cells from damage [45].

-

4.

Iron metabolism: copper, as a key component of plasma copper-binding proteins, is involved in iron metabolism [46]. Ferroxidase I (ceruloplasmin) and Ferroxidase II play a crucial role in oxidizing ferrous ions (Fe2+) to ferric ions (Fe3+) [47]. The oxidation process facilitates the binding of iron to transferrin, which aids in the release of iron from storage sites, such as the liver and bone marrow, into the bloodstream, promoting red blood cell production [48]. A deficiency in copper can disrupt iron metabolism, leading to anemia [49].

-

5.

Connective tissue health: copper plays a key role in synthesizing collagen and elastin to maintain the structural integrity of skin, blood vessels, and bones [50]. It enhances the stability and elasticity of the tissues by promoting the hydroxylation of lysine and proline [51].

-

6.

Nervous system function: copper is involved in the formation of myelin and plays a vital role in the synthesis of dopamine [52]. Additionally, it is crucial in catalyzing the conversion of dopamine to the neurotransmitter norepinephrine and is closely related to the biosynthesis of catecholamines [53]. A deficiency in copper can lead to neurological issues, such as cognitive impairments and motor coordination problems [54].

-

7.

Immune function: copper is vital for the proper functioning of the immune system [55]. It supports the production and activity of white blood cells, enhancing the body's resistance to infections [56].

2.2. Mechanisms of copper accumulation in cells

Copper, an essential trace element, is vital for maintaining various physiological functions in the body [29]. Under normal conditions, cells regulate copper ion levels to ensure a stable, low concentration [57]. However, when the balance is disrupted by excessive copper accumulation, a specific form of cell death known as cuproptosis can be triggered. The process depends on the buildup of copper ions within the cell, highlighting the importance of controlling copper levels to either prevent or induce the response. The following section discusses the key mechanisms by which copper ion regulation functions as a “switch” for cuproptosis.

-

1.

Increased copper transporters: elevated levels of copper transporters on cell membrane, such as copper transporter 1 (CTR1), also known as solute carrier family 31 member 1 (SLC31A1), copper transporter 2 (CTR2), and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), enhance the uptake of copper ions [58,59]. For instance, tumor tissues in breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), and stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) exhibit higher SLC31A1 gene expression, which encodes more CTR1 and promotes the uptake of Cu+ into cells [60].

-

2.

Reduction of copper exporters: a decrease in copper exporters, such as ATPase copper transporting alpha polypeptide (ATP7A) and ATPase copper transporting beta polypeptide (ATP7B), impairs the excretion of Cu+, resulting in higher intracellular Cu+ levels [61]. For instance, a hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-responsive copper hydroxyphosphate nanoparticles (Cu2 (PO4) (OH) NPs) can downregulate the expressions of ATP7A, which leads to copper accumulation [62].

-

3.

Copper carriers: copper carriers are lipid-soluble compounds capable of transporting copper ions directly into cells, thereby promoting intracellular copper accumulation. Common examples include elesclomol (ES) and disulfiram (DSF), which facilitate the uptake of Cu2+ [32,63]. In addition to these well-established agents, several novel copper carriers have been identified in recent years, such as 8-hydroxyquinoline and its derivatives, hydroxylated flavonoid-based copper carriers (HQFs), pyrithione, and the natural product-derived Pochonin D (PoD) [64].

-

4.

Inhibition of copper chelators: copper-binding molecules such as glutathione (GSH) and metallothionein 1/2 (MT1/2) regulate intracellular copper levels. Inhibiting their function increases free copper [65]. For instance, Buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO) inhibits glutathione synthase, reducing Cu+-GSH binding and promoting copper accumulation [66]. Other important proteins involved in copper chaperoning and coordination include copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS), antioxidant protein-1 (ATOX1), and cytochrome c oxidase copper chaperone (COX17), which participate in intracellular copper delivery and mitochondrial copper homeostasis [67].

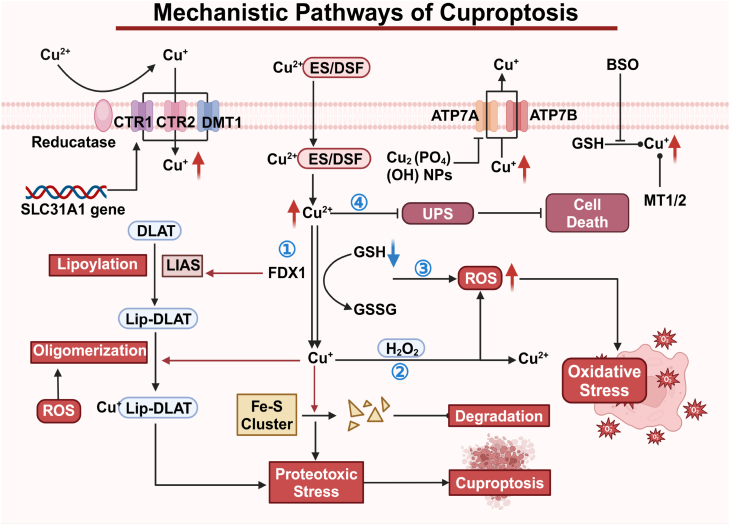

2.3. Mechanisms of cuproptosis

Excessive copper accumulation triggers a series of changes in cellular pathways and functions, such as oxidative stress and disruption of mitochondrial energy metabolism [29]. The alterations ultimately lead to a distinct form of PCD known as cuproptosis [35]. Below, we summarize the key mechanisms underlying cuproptosis Fig. 3).

-

1.

Copper-dependent cell death. Excess Cu2+ is transported into the mitochondria, where it is reduced to Cu+ by ferredoxin-1 (FDX1), which also plays a role upstream in the lipoic acid (LA) pathway [36]. Under its regulation, lipoic acid synthase (LIAS), a gene associated with the LA pathway, facilitates the attachment of the lipoyl group to tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle-associated enzymes, particularly dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT) [37]. Cu+ binds directly to lipoylated proteins, causing their oligomerization, and inhibits the formation of Fe-S cluster proteins [38]. The effects lead to proteotoxic stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, culminating in cell death.

-

2.

Oxidative stress activation. Excess Cu + reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) via the Fenton reaction, producing large amounts of ROS. The increase in ROS causes intracellular oxidative stress and contributes to cell death. Additionally, ROS can promote the aggregation of lipoylated DLAT in the mitochondria, further triggering cuproptosis [68].

-

3.

Reduction of GSH. Cu2+ can oxidize the reduced GSH to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), depleting the critical antioxidant. The process impairs the glutathione-based defense system, which normally neutralizes reactive hydroxyl groups, leading to the burst of ROS and eventually cell death [69].

-

4.

Disruption of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). The UPS is crucial for protein degradation. Cu2+ inhibits activity of proteasome, which is essential components of the UPS mechanism, and enhances interactions between ubiquitin and proteins, causing accumulation of misfolded proteins, inducing cell death [39].

Fig. 3.

Schematic of cuproptosis mechanism. The copper ionophores ES/DSF sends Cu2+ into the cells and then into the mitochondria. Cu2+ is reduced to Cu+, inducing proteotoxic stress via protein lipoylation and subsequent DLAT aggregation. Moreover, Cu+ inhibits Fe-S cluster proteins formation, inducing cuproptosis. Created in BioRender. Zhang, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e66j274.

2.4. Relevance of cuproptosis in human cancers

Cuproptosis is a newly identified and mechanistically distinct form of PCD, driven by copper-induced mitochondrial stress. Unlike other PCD forms, it is tightly linked to mitochondrial metabolism and copper homeostasis, two pathways frequently altered in cancer. Emerging evidence suggests that cuproptosis plays a critical role in tumor biology, offering new opportunities for biomarker discovery and therapeutic intervention. Below, we summarize current insights into its relevance in human cancers.

-

1.

Dysregulated copper metabolism in tumors. Multiple cancer types, including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, glioblastoma, and lung adenocarcinoma, exhibit aberrant copper accumulation, largely driven by the overexpression of copper transporter SLC31A1 (CTR1) [60,70]. This not only reflects a metabolic reprogramming toward copper dependence but also renders these tumors particularly susceptible to cuproptosis-inducing agents. Notably, copper overload can disrupt mitochondrial function and trigger proteotoxic stress via lipoylated protein aggregation, the hallmark of cuproptosis [35].

-

2.

Prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Core components of the cuproptosis pathway, such as FDX1, LIAS, and LIPT1, have emerged as potential biomarkers for patient prognosis and therapeutic response [71]. Elevated FDX1 expression is associated with improved survival in cancers like hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma, possibly due to increased vulnerability to copper-induced stress [71]. These molecular markers may help identify tumor subsets that are inherently more responsive to cuproptosis-based strategies.

-

3.

Therapeutic potential and selectivity. Pharmacological agents that perturb copper homeostasis—such as ES and DSF—have shown promising anti-tumor activity in preclinical models [72]. By exploiting the metabolic reliance of certain tumors on mitochondrial respiration, these compounds selectively trigger cuproptosis in cancer cells while sparing normal tissues [32,63]. Importantly, this mode of action is orthogonal to apoptosis or ferroptosis, making cuproptosis an attractive avenue for overcoming resistance to conventional therapies.

-

4.

Association with immune modulation. Emerging studies have revealed correlations between cuproptosis-related gene expression profiles and patterns of immune infiltration across multiple tumor types [73]. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, for instance, cuproptosis gene signatures are linked to T cell and macrophage enrichment, suggesting potential synergy with immune checkpoint blockade [74]. This highlights the possibility of integrating cuproptosis-targeted therapies with immunotherapeutic regimens.

-

5.

Cancer subtype vulnerability and therapeutic stratification. The sensitivity to cuproptosis varies not only among tumor types but also across molecular subtypes [59]. Tumors characterized by high oxidative phosphorylation activity, such as subsets of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or kidney cancer, appear to be more dependent on lipoylated mitochondrial proteins, and thus more vulnerable to cuproptosis induction [75]. This subtype-specific susceptibility offers a rationale for precision targeting in selected patient populations.

Taken together, these findings underscore the growing recognition of cuproptosis as a clinically relevant vulnerability in cancer. Its tight connection to mitochondrial metabolism, tumor subtype specificity, and immune modulation distinguishes it from other PCD pathways and supports its development as a novel therapeutic axis.

2.5. Nanomedicine for tumor cuproptosis

Nanomedicine strategies targeting cuproptosis have advanced by focusing on key aspects of copper metabolism, including the uptake, transport, and excretion [73,76,77]. The approaches leverage a detailed understanding of copper regulation to enable precise interventions at different stages of copper homeostasis [58]. Compared to conventional treatments, nanomedicines provide significant benefits, such as customizable features, multi-target capabilities, and fewer side effects [78]. The advantages position nanomedicines as a promising avenue for developing targeted therapies to address tumor-related cuproptosis.

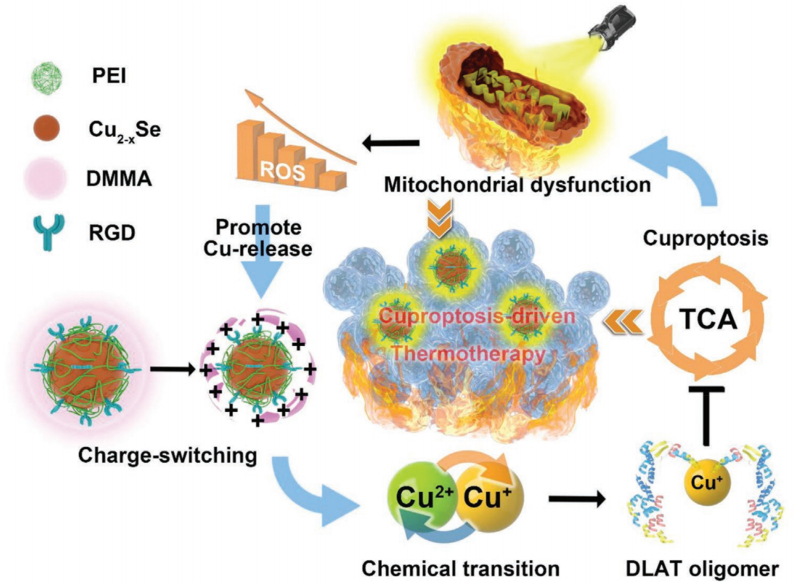

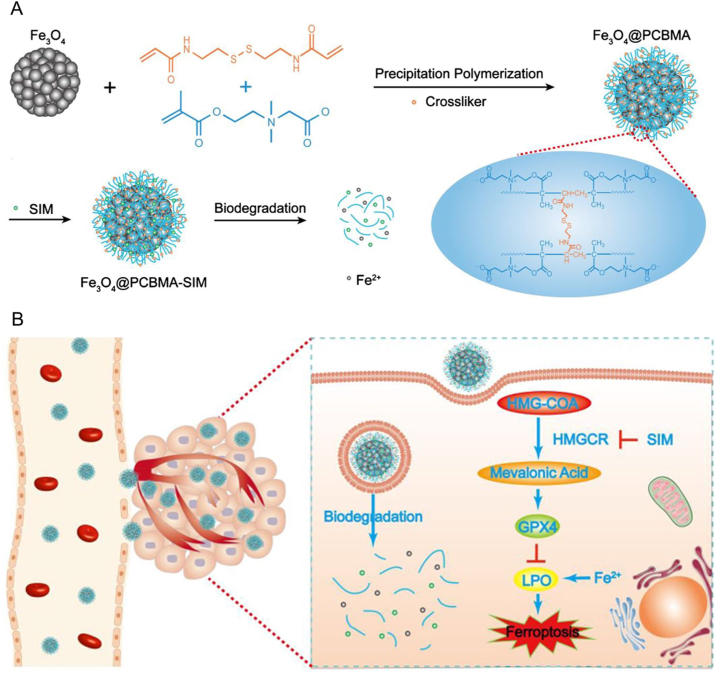

2.5.1. Copper carrier-based nanomedicine for cuproptosis

Copper carriers are complexes that load and transport copper ions into cells, potentially leading to excessive copper accumulation and enhanced cuproptosis. Various nanomedicines capable of carrying metal ions have been developed, including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), bioresponsive polymers, nano-selenium alloy materials, and enzyme-engineered nonporous coordination polymers [76,[79], [80], [81]]. Chan et al. developed a nanosystem by encapsulating photothermal Cu2-xSe nanoparticles within bioresponsive dimethyl maleic anhydride (DMMA), which named DMMA@Cu2-xSe. Cu2-xSe acted as a copper carrier to address the deficiency of copper concentration by precisely targeting and accumulating copper in tumor tissues [76]. The reaction between DMMA and amino groups produced an amide that hydrolyzed under weakly acidic conditions, causing DMMA to separate from the nanosystem. The released Cu2-xSe was oxidized by high concentration of H2O2 to release Cu2+, which triggered the oligomerization of DLAT, an enzyme related to TCA cycle, and down-regulated the expression of key proteins in the TCA cycle and aerobic respiration, inhibiting mitochondrial aerobic respiration (Fig. 4). Upon entering the TME, the strongly positively charged poly(ethylene imine) (PEI), initially blocked by DMMA, was exposed, resulting in a positive surface charge on Cu2-xSe. The charge reversal enhanced the cellular uptake of Cu2-xSe. The aerobic respiratory depression induced by cuproptosis exacerbated mitochondrial damage during tumor hyperthermia. After laser irradiation, PTT further induced mitochondrial dysfunction, followed by the excessive production of intracellular ROS. DMMA@Cu2-xSe was oxidized by ROS and Cu2+ was released into tumor cells, which damaged the tumor cells, causing changes in the cell cycle. The synergistic photothermal-cuproptotic properties demonstrate enhanced efficacy of PTT, offering a promising new approach for cancer treatment.

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of the DMMA@Cu2-xSe nanosystem for cuproptosis-driven enhancement of thermotherapy. Reprinted with permission [76]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons.

In addition, Xu et al. developed a nanomedicine, GOx@[Cu(tz)], which successfully carried copper ions into cells. The nanomedicine was created by encapsulating glucose oxidase (GOx) within nonporous copper(I) 1,2,4-triazolate ([Cu(tz)]) [82]. After entering the cells, the nonporous structure was decomposed by the stimulation of overexpressed GSH. Cu+ from decomposed GOx@[Cu(tz)] can cause the accumulation of lipoylated DLAT, associated with the mitochondrial TCA cycle, leading to cuproptosis. In Gox@[Cu(tz)], the [Cu(tz)] component limited the interaction of GOx with circulating H2O2 by impeding the diffusion of blood glucose and convert oxygen (O2), ensuring that the catalytic activity of GOx was masked under physiological conditions. Under the stimulation of the overexpressed GSH, the restricted GOx catalytic activity was released to consume glucose, thereby enabling cancer starvation therapy. In addition, under near-infrared (NIR) light, a substantial amount of ·OH was produced by the Fenton-like redox reaction between H2O2 generated by glucose oxidation and Cu+. The reaction was further promoted by the restored activity of GOx@[Cu(tz)]. Furthermore, Cu2+ oxidized by H2O2 from surface Cu + also promoted Fenton-like reaction, producing more ·OH. In a similar approach aimed at enhancing copper ion delivery and amplifying oxidative stress, Yu et al. developed a semiconductor polymer nanoreactor, termed SPNLCu, which functioned as an efficient copper carrier. The system successfully delivered Cu2+ into tumor cells, inducing cuproptosis [81]. The innovative nanoreactor combined a sonodynamic semiconducting polymer nanoparticle (SPN) with lactate oxidase (LOx) using ROS-cleavable linkers and was further chelated with Cu2+. When exposed to ultrasound (US) irradiation, SPNLCu produced singlet oxygen (1O2), which broke the ROS-cleavable linkers and led to the release of LOx. The process depleted lactate and generated H2O2. The conversion of Cu2+ to Cu + facilitated the production of ·OH through a reaction with H2O2. Additionally, Cu+ reduced the expression levels of FDX1 and DLAT, culminating in cell death.

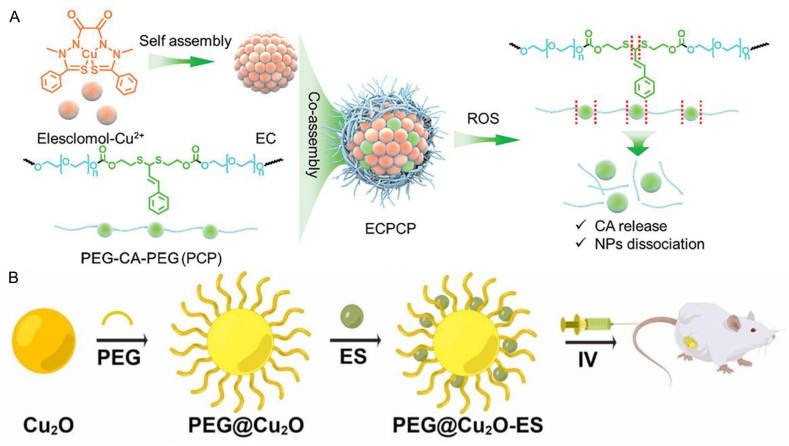

Additionally, single-molecule ES, a highly lipophilic copper-binding molecule, has been reported for metal ion loading, facilitating transport by forming complexes with copper ions [72]. Researchers have utilized the copper-binding properties of the compound to develop a variety of nanodrugs aiming at inducing cuproptosis. Guo et al. developed an innovative nanoparticle (NP@ESCu) by encapsulating ES and Cu2+ within a ROS-sensitive polymer (PHPM) [80]. When NP@ESCu was taken up by cancer cells, the ROS-sensitive thioketal bonds in PHPM were broken upon exposure to high ROS levels, then ES-Cu were released. ES could selectively transport Cu2+ to the cell mitochondria, and the released Cu2+ could bind to FDX1, a mitochondrial reductase involved in the formation of Fe-S clusters, which led to the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+, inhibiting the generation of Fe-S clusters, causing Cu+ to bind directly to the lipoylated protein and ultimately inducing cell death. Meanwhile, ES was effluxed, which transported additional extracellular Cu2+ into cancer cells, leading to continuous Cu2+ accumulation and subsequent cuproptosis. To further optimize the therapeutic efficacy of ES-based copper delivery, Wu et al. engineered a refined system with a positive feedback loop to amplify oxidative stress and cuproptosis. The formulation integrated the ES-Cu compound (EC) with a novel ROS-responsive polymer (PCP), which was composed of cinnamaldehyde (CA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), forming a nanoplatform, denoted as ECPCP (Fig. 5A) [56]. After cellular uptake, the PCP degraded and released CA and EC upon exposure to high levels of ROS. EC further broke down into ES and Cu2+. Cu2+ bound to FDX1 and was reduced to Cu+, which caused the lipoylation of DLAT and cell death. Meanwhile, ES transported extracellular Cu2+ into tumor cells, leading to the continuous accumulation of Cu2+ and cuproptosis. Cu2+ reacted with GSH, generating more toxic Cu+ and GSSG. The Fenton reaction, triggered by Cu+, and oxidative stress, induced by CA, promoted the production of ROS and the liberation of CA, forming a positive feedback mechanism that accelerated the dissociation of the ECPCP and further enhanced the anti-tumor effect.

Fig. 5.

A) The preparation process of ECPCP. B) Schematic diagram of PEG@Cu2O-ES inducing cuproptosis in breast cancer. Reprinted with permission [23,56]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

2.5.2. Nanomedicine for the regulation of copper exporters

Copper exporters are instrumental in the efflux of copper ions, with ATP7A and ATP7B serving as key representatives. Both ATP7A and ATP7B are P-type ATPase family members that facilitate copper ion transport within cells through multiple functional regions, including transport domains and ATP-hydrolyzing domains [61]. The domains work together to transport copper ions across cell membranes. The process initiates with copper ions binding to the copper-binding domains of either ATP7A or ATP7B, which then stimulates ATP hydrolysis and drives copper ions out of the cell [83]. In recent years, researchers have developed various nanomedicines aimed at inhibiting copper exporters, leading to elevated intracellular copper concentrations and triggering cuproptosis. For example, Jin et al. developed a nanoreactor, CCJD-FA, to increase intracellular copper levels by inhibiting ATP7B [77]. CCJD-FA encapsulated calcium peroxide nanoparticles (CaO2NPs) in a copper-based MOF shell, carrying JQ-1, a bromodomain inhibitor. In high-GSH environments, CCJD-FA dissociated to release Cu2+ and CaO2. Under acidic conditions, CaO2 produced H2O2, which reacted with Cu2+ to form Cu+ and O2. Notably, the released JQ-1 and O2 inhibited glycolysis in cancer cells, reducing ATP levels. The decrease in ATP disrupted ATP7B-mediated copper efflux, as ATP7B relies on ATP for energy, leading to increased intracellular copper ions and heightened sensitivity to cuproptosis. Similarly, Yan et al. developed an inhalable nanodevice named CLDCu to impact ATP7B function [84]. CLDCu featured a shell containing Cu2+ and a core loaded with DSF. Upon entering tumor cells, CLDCu disassembled in mild acidity, releasing DSF and Cu2+. DSF bound to Cu2+ to form bis(diethyldithiocarbamate)-copper (CuET), which substantially enhanced ROS generation. The increase in ROS damaged the MMP protein and inhibited ATP production. Consequently, ATP7B expression decreased, leading to reduced Cu+ export and elevated intracellular Cu+ levels, further inducing cuproptosis. The CLDCu-treated group showed significantly lower ATP levels and higher Cu+ content than other groups. While previous efforts focused on ATP7B, Liu et al. shifted attention to ATP7A, another key copper exporter, employing a distinct ROS-generating mechanism. Liu et al. designed a nanozyme called Cu-DBCO/CL to inhibit another copper exporter, ATP7A [85]. The nanozyme integrated cholesterol oxidase (CHO) into a copper-based framework. CHO effectively catalyzed the conversion of cholesterol to cholestenone and H2O2, generating ·OH, which elevated ROS levels. The increased ROS disrupted intracellular homeostasis, impaired mitochondrial function, and reduced ATP production, resulting in the inhibition of ATP7A and Cu+ accumulation. Li's group further reported a nanomedicine to inhibit Cu-ATPase, achieving notable results in enhancing cuproptosis (Fig. 5B) [23]. The formulation included Cu2O along with Cu2O-loaded ES. Cu2O generated ROS through a Fenton-like reaction, impairing Cu-ATPase function on cancer cell membranes and reducing Cu2+ efflux. In experiments, Cu-ATPase activity in the treated group decreased by about 80 % compared to the control, alongside a marked increase in intracellular copper ion concentration. The results demonstrated that the nanomedicine effectively induced a targeted rise in copper ions within treated cells.

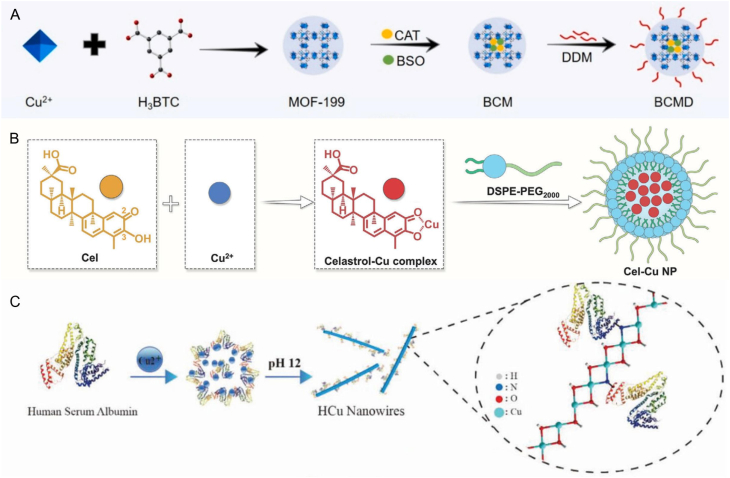

2.5.3. Nanomedicine for the inhibition of copper chelators

Copper chelators can bind to copper ions, resulting in a decrease in the concentration of free copper ions within cells. Two notable examples of such chelators are GSH and MT1/2. GSH is a thiol-containing copper chelator that can form GSH-Cu complexes [65]. The proteins MT1 and MT2, which are rich in thiols, bind copper ions in a pH-dependent manner through their cysteine residues [86]. Given the properties of the proteins in binding and storing copper, researchers have developed various nanomedicines aimed at inhibiting copper chelators. The inhibition can lead to an increase in the concentration of free copper ions in cells, thereby enhancing cuproptosis. Huang et al. developed a copper-based nanoplatform, named BSO-CAT@MOF-199@DDM (BCMD), designed to incorporate the inhibitor BSO within MOF-199 to modulate GSH levels effectively (Fig. 6A) [87]. Once internalized by tumor cells, BCMD dissociated in the mildly acidic tumor environment, releasing Cu2+ and BSO. The released BSO then inhibited glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL), the rate-limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis, thereby effectively blocking GSH production. Additionally, BCMD triggered ICD, activating cytotoxic T cells to release IFN-γ. The process resulted in decreased expression of cystine/glutamate transporter proteins (SLC7A11/SLC3A2), essential for GSH synthesis as the transporters supply cysteine, a key precursor. As a result, GSH synthesis declined due to insufficient precursor availability. In GSH content assays, the BCMD treatment group showed the lowest GSH levels, confirming the effective action of BSO. While BCMD achieved GSH depletion by directly inhibiting its biosynthesis via enzymatic blockade, Lu et al. employed a distinct mechanism, utilizing celastrol to suppress the expression of key regulatory proteins involved in GSH production through NF-κB pathway inhibition. Cel and Cu2+ were used to synthesize a self-amplified cuproptosis nanoparticle (Cel-Cu NP) aimed at inhibiting GSH synthesis (Fig. 6B) [88]. After internalization by cells, Cel-Cu NP released Cu2+ and Cel. Cel inhibited the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, reducing the production of glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM). The inhibition suppressed the expression of GCL, ultimately resulting in decreased GSH levels. Reduced GSH, which chelated copper ions, led to an increase in free intracellular copper, thereby amplifying cuproptosis. Gene set enrichment analysis revealed a decline in NF-κB signaling pathway activity and an increase in GSH metabolic pathway activity. The experimental results indicated that cells treated with Cel exhibited lower NF-κB and GCLM protein levels compared to those treated with PBS. Additionally, GSH levels in cells treated with Cel-Cu NPs decreased by 53 %. The findings suggested that Cel enhanced GSH depletion by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, thereby promoting cuproptosis. In contrast to these biosynthesis-targeting strategies, Man et al. devised a direct GSH depletion platform using copper hydroxide nanowires (HCu nanowires), synthesized through an in situ biomineralization process involving Cu2+ and human serum albumin (HSA) at pH 12 (Fig. 6C) [89]. The innovative process involved combining Cu2+ with HSA, which imparted oxygen vacancies (OVs) to the HCu nanowires, enhancing their affinity for GSH. Once internalized by cells, HCu nanowires effectively depleted GSH and reduced Cu2+ to the more toxic Cu+. Additionally, HCu nanowires could directly oxidize GSH, effectively bypassing the conversion of Cu2+ and demonstrating a superior capacity for GSH consumption.

Fig. 6.

A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of BCMD. B) Schematic illustration of the preparation process of Cel-Cu NP. C) Schematic illustration of HCu nanowires. Reprinted with permission [[87], [88], [89]]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons.

In summary, researchers have developed various nanomedicines targeting key mechanisms to induce cuproptosis and suppress tumor growth and metastasis (Table 2). The strategies include enhancing copper transporters, reducing copper exporters, utilizing copper carriers, and inhibiting copper chelators. Future studies could explore additional proteins, ribonucleic acid (RNA), or DNA molecules within the pathways or investigate combination therapies that integrate cuproptosis with other mechanisms to achieve synergistic effects and improve therapeutic outcomes. However, these strategies still face several challenges in practical applications. Excessive administration of copper-containing agents may lead to systemic toxicity due to copper accumulation in non-target tissues. In addition, cuproptosis primarily relies on active mitochondrial metabolism, which may limit its efficacy against tumor subpopulations with low dependence on oxidative phosphorylation.

Table 2.

Applications of representative nanomedicines for cuproptosis.

| Nanomedicine structure | Mechanisms of action | Loaded drugs | Combined therapy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMMA@Cu2-xSe | Nanomedicine serves as copper carriers | DMMA | Photothermal therapy | [76] |

| GOx@[Cu(tz)] | GOx | Photothermal therapy | [82] | |

| SPNLCu | – | Immunotherapy | [81] | |

| Cu(I) NP | – | Immunotherapy | [90] | |

| CuD@PM | 5-azacytidine | Photodynamic therapy | [91] | |

| Cu/APH-M | – | Radiotherapy, Immunotherapy | [92] | |

| Na10[(PW9O34)2Cu4(H2O)2]·18H2O | – | Radiotherapy | [36] | |

| NP@ESCu | Utilization of copper carriers ES | PHPM | Immunotherapy | [80] |

| ECPCP | Cinnamaldehyde | Immunotherapy | [56] | |

| DSF/CuS-C | Utilization of copper carriers DSF | CpG | Photothermal therapy, Immunotherapy | [93] |

| M@HMnO2-DP | 5-azidobenzene-1, 3-diol 4-ethynylphenol |

– | [38] | |

| BCO-VCu | Reduction of copper exporters ATP7A and ATP7B |

– | Immunotherapy | [94] |

| HFn-Cu-REGO NPs | Regorafenib | Chemotherapy | [95] | |

| PEG@Cu2O-ES | – | Photothermal therapy, Immunotherapy | [23] | |

| Cu-DBCO/CL | Reduction of copper exporters ATP7A | Lysyl oxidase inhibitor | Immunotherapy | [85] |

| TPZ@Cu2Cl(OH)3-HA (TCuH) NPs | Tirapazamine | Photothermal therapy | [96] | |

| CAPSH | Hyaluronic acid | Thermodynamic therapy | [97] | |

| RNP@Cu2O@SPF | FA-PEG-COOH | Chemical dynamic therapy | [98] | |

| CCJD-FA | Reduction of copper exporters ATP7B | Bromodomain-containing protein 4 inhibitor | Immunotherapy | [77] |

| CLDCu | Chitosan | Immunotherapy | [84] | |

| BSO-CAT@MOF-199@DDM | Inhibition of copper chelators GSH | Buthionine-sulfoximine | Immunotherapy | [87] |

| Cel-Cu NP | Celastrol | Immunotherapy | [88] | |

| HCu nanowires | – | Chemodynamic therapy | [89] | |

| CuP/Er | Erastin | Immunotherapy | [73] | |

| CJS-Cu NPs | – | Photodynamic therapy | [99] | |

| AuBiCu-PEG NPs | Bi element | Radiotherapy, Immunotherapy | [100] | |

| HA-CuH-PVP | Hyaluronic acid | Hydrogen therapy | [101] |

3. Introduction of pyroptosis

Pyroptosis, a form of PCD, characterized by cell swelling and bubbling, culminating in membrane rupture, is primarily regulated by the caspase and gasdermin protein families. Pyroptosis is accompanied by the formation of transmembrane channels and the release of pro-inflammatory cellular components such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) [102]. Pyroptosis is distinguished by its unique ability to trigger inflammation, setting it apart from apoptosis and necrosis [103]. Interestingly, in 1992, researchers utilized an electron microscope to observe Shigella flexneri-infected mouse macrophages and found that the cells exhibited morphology changes, such as bubbling, and pykoses. However, owing to the limited understanding of pyroptosis at that time, these macrophages were not deemed as pyroptosis but were instead categorized as apoptosis [104]. As the investigation of pyroptosis intensifies, the term “pyroptosis” was initially coined in 2001, combining the Greek roots “pyro” and “ptosis,” which respectively signify “fever” and “fall,” to characterize the particular form of cell death [105]. Pyroptosis is commonly initiated through the activation of caspase protein. Activation of caspase occurs in response to the infection of bacteria, viruses, or other pathogens, and stimulus such as the elevated levels of intracellular calcium ion (Ca2+) and ROS [106,107]. The activated caspase can subsequently target downstream gasdermin proteins, leading to the generation of its N-terminal domains. The N-terminal domains underwent conformational changes, exposing the membrane binding sites and forming four chain structures that could be inserted into the cell membrane, and were oligogenous to form pores, ultimately inducing pyroptosis [108].

3.1. Classification of caspase

In 1996, scientists proposed the term “caspase”, short for cysteine aspartic acid-specific protease, to delineate the enzymatic properties of this protein family. The term “caspase” is derived from “cysteine protease” due to its capacity to cleave peptide bonds at specific protein aspartate residues [109]. Caspases are a highly conserved intracellular protein series with a structure similar to IL-1β converting enzyme or Human Caenorhabditis elegans death protease. Activation of specific caspases can lead to apoptosis, inflammasome formation, and pyroptosis by utilizing the cysteine active center to recognize and cleave peptide bonds in target proteins (such as gasdermin, pro-IL-1β, and pro-IL-18) [109,110].

Caspases can be broadly categorized into apoptotic caspases and inflammatory caspases. The apoptotic caspases, namely caspase-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, -9, and -10, can be classified as initiator caspases and effector caspases based on their distinct roles in initiating apoptosis. Caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10 serve as initiator caspases, amplifying signals and activating corresponding effector caspases. As effector caspases, caspase-3, -6, and -7 execute the apoptosis process.

Inflammatory caspases encompass caspase-1, -4, -5, -11, and −12 [110]. Apart from caspase-12, the remaining inflammatory caspases can initiate inflammasome formation (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18) and trigger pyroptosis by cleaving downstream members of the gasdermin family [110]. Caspase-12, distinct from other inflammatory caspases, localizes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and can be activated by ER stress, leading to ER-related apoptosis [111]. Caspase-14 is a unique caspase associated with epidermal differentiation, standing independent of the apoptotic and inflammatory categories [112]. It's worth noting that there is no strict delineation between apoptotic and inflammatory caspases, as apoptosis-related caspases, such as caspase-3 and -8, are also implicated in pyroptosis pathways [113,114]. In such instances, these inflammatory and apoptotic caspases participate in pyroptosis by cleaving specific gasdermin proteins.

3.2. Classification of gasdermin

In the early 21st century, the gasdermin gene was identified through the cloning of the hair-shedding fragment of chromosome 11 in recombination-induced mutation 3 mice [115,116]. Subsequent studies revealed that this gene family exhibited high expression in both the gastrointestinal tract (gastro) and skin tissue (dermato), leading to the terminology “gasdermin.” Furthermore, the heterogeneous expression of this gene in tissue cells was noted. For a long time, pyroptosis was understood as a caspase-1-dependent form of cell death, but the physiological role of gasdermin proteins and their involvement in the pyroptosis pathway remained unclear [105,117,118]. It wasn't until 2015 that researchers discerned the biological effects of the gasdermin family and their pivotal role in pyroptosis [119,120]. When the body's tissue cells are under assault from infections, tumors, asthma, systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and other factors, members of the gasdermin family exhibit varying degrees of expression in these tissues to address abnormal cells and preserve the body's equilibrium [[121], [122], [123], [124]]. The gasdermin protein family consists of six members encoded by six homologous genes, namely gasdermin A (GSDMA), gasdermin B (GSDMB), gasdermin C (GSDMC), gasdermin D (GSDMD), gasdermin E (GSDME), and gasdermin F (GSDMF) [116] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Classification of gasdermins.

| Human | Mouse | Biodistribution | Pyroptosis-inducing ability | Related Disease | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSDMA | GSDMA1-3 | Skin, esophagus, stomach, airway bladder epithelium | Yes | Ashama, systemic sclerosis, atopic dermatitis, mice alopecia | [129] |

| GSDMB | None | Airway, bowel, epithelium, stomach, esophagus, liver | Yes | Ashama, IBD, breast, gastric and lung cancer | [125,132] |

| GSDMC | GSDMC1-4 | Esophagus, skin, spleen, and vagina | Yes | atopic dermatitis, food allergy | [117,118] |

| GSDMD | GSDMD | Immune cells, placenta, gastrointestinal and esophageal epithelium, skin, airway | Yes | Parkinson's disease, sepsis, macular degeneration, IBD, acute kidney injury | [117,125] |

| GSDME | GSDME | Brain, endometrium, placenta, intestines | Yes | Autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss | [125,156] |

| GSDMF | GSDMF | Inner ear | No | Recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment | [125] |

The gasdermin protein family shares highly conserved N and C domains in structure, with a protein bond linking these domains to form intact gasdermin [125]. The N domain can interact with membrane phospholipids, such as cardiolipin and phosphatidylserine, and induce pyroptosis [126,127]. However, due to the presence of the linking-protein bond and its coverage on the lipid-binding site on the N-terminal domain, the intact gasdermin proteins are self-inhibited, making GSDMs unable to exert their biological effects. Notably, during inflammation and tumorigenesis, immune cell-mediated immune inflammatory responses produce corresponding inflammasomes, which can eliminate self-inhibition through the activation of the caspase [125]. This process releases free N domains, which then assemble on the cell membrane, forming a transmembrane channel that causes membrane damage and pyroptosis. These channels allow the release of intracellular contents (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), ATP) and inflammasomes (e.g., IL-1β, IL-18). Simultaneously, due to differences in internal and external ion concentrations, a significant influx of extracellular fluid into the cell leads to swelling and blistering, ultimately forming the typical morphology of pyroptosis [125,128].

3.2.1. GSDMA

The GSDMA (or FKSG9) protein is present in the epithelial tissues of the skin, esophagus, stomach, airway, and bladder in both humans and mice [129]. Notably, the expression pattern differs between the two species. In humans, a single GSDMA gene subtype is expressed, whereas in mice, three distinct GSDMA gene subtypes, namely GSDMA1, GSDMA2, and GSDMA3, are expressed in tissues. The human GSDMA and mouse GSDMA3 proteins feature GSDME-N capable of creating membrane pores and initiating pyroptosis. The N-terminal domain of GSDMA3 facilitates its insertion into the cell membrane by forming extended transmembrane β chains during the pyroptosis process [108]. GSDMA is implicated in the development of numerous diseases due to its differential expression in various tissues. In the respiratory system, the GSDMA is expressed in the airway epithelium, and the inflammatory response triggered by cell pyroptosis mediated by GSDMA is one of the mechanisms of the onset of asthma [117,122,130]. In the nervous system, monocyte-derived macrophage pyroptosis induced by the overexpression of GSDMA may be associated with relevance to the pathogenesis and modulation of systematic sclerosis [123]. In keratinocytes, the cysteine protease streptococcalpyrogenic exotoxin B (SpeB), produced by group A hemolytic streptococcus (GAS), can trigger the pyroptosis of keratinocytes by cleaving GSDMA, contributing to the dissemination of localized skin infections caused by GAS, ultimately leading to severe systemic infection [131].

3.2.2. GSDMB

GSDMB (or GSDML) is primarily expressed in the airway epithelium, intestinal epithelium, stomach, esophagus, liver, and various other tissues [125,132]. This gene is exclusive to humans and comprises four subtypes: GSDMB1, GSDMB2, GSDMB3, and GSDMB4. GSDMB shares structural similarities with other members of the gasdermin protein family [133]. However, the absence of exon 6—crucial to cell pyroptosis—results in significant differences in gene sequences between GSDMB1/2 and GSDMB3/4. This divergence subsequently leads to variations in the amino acid sequences of GSDMB1-N and GSDMB2-N compared to GSDMB3-N and GSDMB4-N. Notably, only the GSDME-N of GSDMB3 and GSDMB4 exhibit pore-forming activity [134,135].

GSDMB is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. Within the respiratory system, it serves as a susceptibility gene for asthma [117]. In instances where asthma patients experience respiratory viral infections, GSDMB may enhance the expression of interferon-stimulating genes by promoting the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein TANK-binding kinase 1, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory response within airway epithelia [136]. Furthermore, in the context of IBD, GSDMB expression is elevated in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC), where it plays a pivotal role in regulating IEC proliferation, migration, adhesion, and epithelial repair [137]. In tumor environments, toxic lymphocytes activate GSDMB in tumor cells, inducing pyroptosis, which represents an effective mechanism for tumor suppression [138].

3.2.3. GSDMC

GSDMC (or MLZE) is expressed in various tissues, including the esophagus, skin, spleen, and vagina [117,118]. In humans, this gene expresses a single subtype of GSDMC, whereas in mice, it is responsible for the expression of four subtypes: GSDMC1, GSDMC2, GSDMC3, and GSDMC4. The GSDMC gene plays a significant role in the proliferation, dissemination, and other malignant biological behaviors associated with tumors, such as kidney cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and colorectal cancer [[139], [140], [141], [142], [143]]. This is achieved through the induction of genes associated with tumor stemness, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, immune evasion, and the inflammatory response that follows cell pyroptosis mediated by GSDMC protein. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that GSDMC also exhibits anti-tumor effects. As a member of the gasdermin family, GSDMC possesses dual functional domains, with its anti-tumor efficacy manifested through the induction of pyroptosis in tumor cells by its N-terminal domain and the enhancement of cellular immunity [144,145].

In IEC, the N6 adenosine methylation of the polyadenosine RNA transcript of the GSDMC gene is crucial for maintaining the activity of intestinal stem cells, which is essential for the proper morphological development of normal IEC [146]. Furthermore, following intestinal worm infection, the expression of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein (O-GlcNAc) transferase is induced, resulting in the O-GlcNAc modification of signal transducer and activator of transcription 6. This modification promotes the release of GSDMC-mediated IL-33 in IEC, which participates in the immune response to worm infection [147]. Additionally, other studies indicate that the anti-helminthic response in the intestinal epithelium is also associated with a type 2 immune response, which is induced by mast cell protease 1 secreted by mast cells that are bound to the surface of IEC, following the cleavage of intestinal epithelial GSDMC [148].

3.2.4. GSDMD

GSDMD is widely expressed in various tissues, including skin, airway epithelium, placenta, esophagus, and gastrointestinal epithelium [117,125]. This gene, located on chromosome 8 adjacent to the GSDMC gene, is expressed in both murine and human models and plays a critical role in pyroptosis and NETosis (a form of inflammatory cell death in neutrophils) [149]. The palmitoylation of the GSDMD protein at Cys191/192 facilitates the formation of pores in the cell membrane by both GSDMD N-terminal (GSDMD-NT) and full-length GSDMD proteins [150]. These transmembrane channels enable the release of intracellular pathogenic substances into the extracellular space, allowing immune cells to capture them, thereby fulfilling an immune function in conjunction with cell pyroptosis [151]. Moreover, during muscle repair, macrophages secrete metabolites through the pores formed by GSDMD, contributing to the activation of muscle stem cells and facilitating the repair and regeneration of muscle tissue [152]. In the central nervous system, GSDMD is implicated in the activation of microglia and mediates the pyroptosis of dopaminergic neurons, exacerbating Parkinson's disease in patients [153]. Additionally, in the liver, GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis is recognized as a significant mechanism contributing to the development of nonalcoholic cirrhosis [154]. In autoimmune diseases, GSDMD has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus through the mediation of neutrophil pyroptosis [155].

3.2.5. GSDME

GSDME (or DFNA5) is expressed in various tissues, including cochlea, brain, endometrium, placenta, and bowel [125,156]. Initially identified as a gene mutation associated with hearing loss in humans, GSDME has recently gained attention for its role in triggering pyroptosis [113]. The GSDME protein possesses a structure analogous to other proteins within the gasdermin family, which includes the pyroptotic N-domain. Beyond its ability to induce pyroptosis via the N-domain, ultraviolet irradiation-induced DNA damage in cervical cancer cells can also stimulate pyroptosis mediated by the full-length GSDME protein [157]. Within the human body, the activated GSDME protein is implicated in the onset and progression of numerous diseases. In particular, it contributes to neuronal damage in brain and spinal neurons by compromising mitochondrial integrity, which is associated with frontotemporal dementia and various neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [158]. Furthermore, during the development of atherosclerosis, GSDME can induce macrophage pyroptosis, thereby facilitating disease progression [159]. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, GSDME-induced pyroptosis in synovial macrophages and monocytes plays a significant role in disease development [160]. Additionally, enhancing the expression levels of GSDME through pharmacological interventions has emerged as a promising strategy in cancer treatment [161,162].

3.2.6. GSDMF

GSDMF (or PJVK, DFNB59, Pejvakin) is expressed in various tissues, including brain, internal ear, heart, and lung tissues [125]. Despite its affiliation with the gasdermin family, the capacity of GSDMF to initiate pyroptosis remains undefined [[163], [164], [165]]. The GSDMF gene is recognized as a crucial component in hearing preservation. Within the inner ear, the expression of GSDMF may enhance peroxisome activity in hair cells in response to noise stimuli, thereby conferring a protective effect on the auditory system. Mutations within this gene can lead to hearing impairment in humans [166].

3.3. Formation of pyroptotic channel

It is evident that the ultimate manifestation of pyroptosis is facilitated by the transmembrane channels of the GSDMs protein family. In recent years, research into the assembly of GSDMA3, GSDMB, and GSDMD-based channels has progressively elucidated the structure of pyroptotic pores and the distinct conformational alterations of GSDMs-N during pore formation, thereby enhancing the understanding of the pyroptosis process [108,133,167].

The GSDMs-N subunit is comprised of a globular domain and a β-barrel domain. The globular domain forms the edge of the pore, encompassing α and β elements. The portion of the globular domain near the lipid membrane consists of positively charged α1, α3, and β1-β2 loop structures, which are masked in the self-inhibited state of the GSDMs protein [108]. The β-barrel structure constitutes the main transmembrane region, with 2 β-hairpin structures (β3-β5, β7-β8), each consisting of 2 inverse parallel β-chains. The β7-β8 hairpin structure and the α1 helix and β1-β2 loop structure in the globular domain serve as lipid binding sites in the membrane pore binding of GSDMs-N.The structure of GSDMs-N inserted into the cell membrane is often likened to a left hand, with the globular domain as the palm, the four inverted parallel beta chains as the fingers, the membrane binding site α1 as the thumb structure attached to the palm, and the β1-β2 loop as the wrist [108,167]. In the self-inhibited state, GSDMs-N resembles a clenched fist, with four β-chains helically hiding the membrane binding site α1, and β1-β2 loops hidden by connecting chains [108,133,167].

When the self-inhibition state of the GSDMs protein family is relieved, GSDMS-N does not directly change its conformation but uses the conformation in the self-inhibition state to oligomerize through hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic force, and the interaction between charges to form a structure called pre-pore. The pre-pore is structured like a yo-yo, divided into two rings, the bottom ring not inserted into the membrane, thus unable to form holes [167]. Subsequently, the GSDMs-N subunit undergoes a significant conformational change resembling the expansion of a clenched fist. This change involved the α1 helix serving as the neutral axis, the spherical domain rotating away from the membrane, and the formation and rotation of two membrane-inserting β-hairpin structures toward the central axis of the pore. Consequently, a transmembrane β-barrel structure with a diameter slightly smaller than the pre-pore was created. During this process, the membrane lipid binding site α1 helix became exposed, and the β7-β8 hairpin structure formed, facilitating the further localization of the membrane pore on the cell membrane. This transition completes the transformation from the pre-pore to the pore, enabling GSDMs-N to position and perforate the membrane [108,167].

The pores formed by GSDMs-N are structurally similar but have different numbers of monomers and parameters. For instance, the GSDMA3-N hole is composed of 26–28 monomers, with a 27-monomer hole having the highest three-dimensional structure confidence. The GSDMB-N hole is composed of 24–26 monomers, with the 24-monomer hole having the most reliable three-dimensional structure. The GSDMD-N hole is composed of 31–34 monomers, with the 33-monomer hole having the highest reliability in the three-dimensional structure [108,133,167]. Although the inner diameter of these cavities varies, it is sufficient to allow the passage of cellular contents and inflammatory mediators produced during pyroptosis into the extracellular matrix [125].

In summary, the GSDMs protein family can exert their important biological effects in pyroptosis by undergoing a process of self-inhibition disinhibition, pre-pore transformation, and pre-pore-to-pore transition.

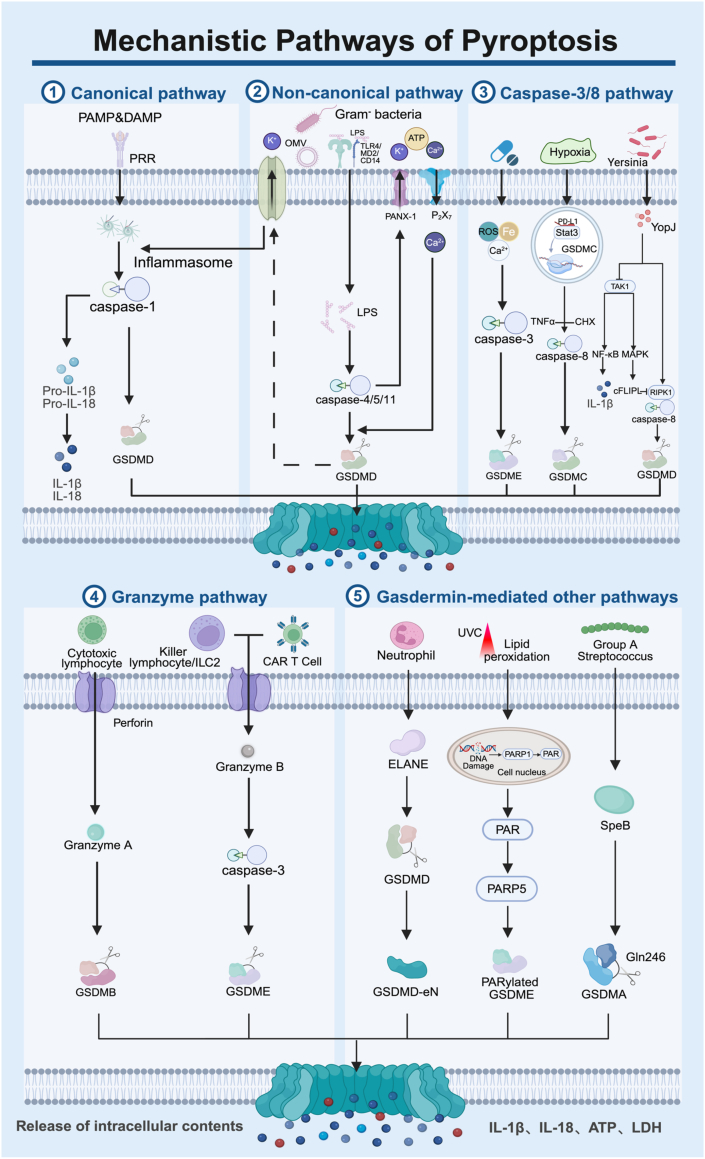

3.4. Mechanisms of pyroptosis

Two pivotal protein families, caspases and gasdermins, form the cornerstone of understanding the pyroptotic pathway. These proteins are intricately linked during the pathogenesis of pyroptosis. Traditionally, pyroptosis is thought to be initiated by activating caspases through associated inflammatory factors. Activated caspases then cleave GSDMD, ultimately triggering pyroptosis. According to the above theory, the pathways of pyroptosis are divided into caspase-1 mediated canonical pathway and caspase-4/5/11 mediated noncanonical pathway [107]. With the deepening research on pyroptosis, the pathway has extended to include the caspase-3/8-mediated and granzyme-mediated pathways [168,169]. In these pathways, pyroptosis is primarily initiated by caspase-mediated cleavage of gasdermin, producing N-terminal domains that oligomerize to form transmembrane pores in the cytomembrane. However, as research progresses, alternative pathways beyond these relatively conserved mechanisms have been identified. Examples include group A GAS virulence factor SpeB and neutrophil elastase proteinase cleaving GSDMD to induce pyroptosis, as well as the intact GSDME protein directly triggering pyroptosis [131,158,170]. The following paragraphs present a comprehensive introduction of the pyroptosis pathways (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Illustration of the mechanisms of the canonical pathway, non-canonical pathway, caspase-3/8 pathway, granzyme pathway, and gasdermin-mediated other pathways. Created in BioRender. Zhang, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/rdy3rde.

3.4.1. Canonical pathway

The canonical pathway involves the activation of caspase-1 by inflammatory factors, which initiates the cleavage of the GSDMD protein, leading to the process of pyroptosis. Both pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) situated on the cell membrane. This recognition leads to the formation of specific inflammasomes, such as Nod-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3). Activated inflammasomes subsequently convert the inactive pro-caspase-1 into its active form, bioactive caspase-1. This enzyme cleaves GSDMD to produce GSDMD-N, resulting in the formation of pores within the cellular membrane that culminate in pyroptosis. Additionally, caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, generating the active forms of IL-1β and IL-18. These cytokines are then released through pyroptotic channels, serving as pro-inflammatory mediators to enhance the immune response [107,169].

3.4.2. Non-canonical pathway

The non-canonical pathway pertains to the action of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produced by gram-negative bacteria, which activates the cleavage of GSDMD via caspase-4, -5, and -11, subsequently initiating pyroptosis. LPS can infiltrate the cytoplasm through two primary mechanisms: one involves the mediation of TLR4/MD2/CD14 during the process of endocytosis by host cells. At the same time, the other relies on the endocytosis of LPS-rich outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) produced by the bacteria [171,172]. Once inside the cytoplasm, LPS can directly activate caspase-4, -5, and -11, which cleaves GSDMD, yielding the pyroptotic GSDMD-N fragment, responsible for forming transmembrane channels.

The cleavage of GSDMD instigates the efflux of K+, subsequently stimulating the activation of the intracellular NLRP3 inflammasome [119,[171], [172], [173], [174], [175]]. Although caspase-4, -5, and -11 are unable to directly convert pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms (IL-1β and IL-18), these cytokines can still be produced and secreted through the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway in certain cell types [163]. Furthermore, caspase-11 can induce pyroptosis through additional mechanisms. The pannexin-1 (PANX-1) ion channel, widely present on the cell membrane, can be cleaved by caspase-11, facilitating the passage of ions such as K+ and bioactive molecules like ATP. Purinergic receptor P2X ligand-gated ion channel 7 (P2X7) receptors, ligand-gated ion channels located on the cell membrane, can be activated by extracellular ATP, resulting in Ca2+ influx—an essential event in GSDMD-N-mediated pyroptosis [176,177]. The activity of caspase-11, triggered by cytoplasmic LPS, leads to the cleavage of PANX-1, allowing the efflux of ATP and K+. Extracellular ATP and K+ subsequently activate PANX-1, causing an influx of Ca2+. This rise in intracellular calcium activates caspase-11, which further cleaves GSDMD to generate the membrane-insertive GSDMD-N fragment, ultimately culminating in pyroptosis induced by the interaction of caspase-11-activated PANX-1 and P2X7 [175].

3.4.3. Caspase-3/8 mediated pathway

Caspase-3/8, traditionally recognized as an apoptotic caspase, is increasingly understood to extend its functions beyond apoptosis, particularly in the context of pyroptosis. Numerous studies have documented the capacity of caspase-3 to facilitate this pathway. Many chemotherapeutic agents utilized in cancer treatment target caspase-3, thereby inducing pyroptosis in tumor cells via the cleavage of GSDME. This process results in the generation of GSDME-N, which subsequently forms pyroptotic pores and exerts anti-tumor effects [113]. Notable examples of such agents include the topoisomerase inhibitors topotecan, etoposide, cisplatin, and irinotecan. Furthermore, advancements in novel technologies and materials, including PDT, acoustic dynamics, and nanomaterials, have enabled the activation of caspase-3 through modifications to the TME. This can be achieved by elevating the levels of ROS within tumor cells or through the overload of calcium and iron, thereby promoting the pyroptosis of tumor cells and contributing to therapeutic anti-tumor strategies [[178], [179], [180], [181], [182]]. Furthermore, it has the potential to enhance the caspase-3/GSDME-mediated pyroptosis pathway by increasing the expression of GSDME in tumor cells, thereby facilitating the objective of tumor treatment [183].

Caspase-8 serves as a pivotal switch in cell death patterns, possessing the ability to initiate pyroptosis [184]. Under hypoxic conditions, pyroptosis can be induced via the nPD-L1-GSDMC-caspase-8 signaling pathway. Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) promotes its nuclear translocation through physical interaction with phosphorylated Stat3 in the nucleus, thereby enhancing the transcriptional activity of GSDMC. In conjunction with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and cycloheximide (CHX), caspase-8 cleaves GSDMC to form GSDMC-N, ultimately triggering pyroptosis [114]. Additionally, the virulence protein Yersinia outer protein J (YopJ), secreted by Yersinia, can inhibit transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and activate the receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)-caspase-8 pathway to induce pyroptosis. TAK1 is involved in the modulation of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, increasing the expression of IL-1β and cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (cFLIPL), both of which are linked to the regulation of cell death. A heightened expression of cFLIPL serves to inhibit the RIPK1-caspase-8 pathway. Conversely, reduced levels of cFLIPL can stimulate caspase-8 activity, facilitating GSDMD cleavage and the induction of pyroptosis [185,186].

3.4.4. Granzyme-mediated pathway

Granzyme A, produced by cytotoxic lymphocytes, enters the target cell via perforin and cleaves GSDMB, leading to the induction of pyroptosis [138]. Additionally, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells exhibit a strong affinity for target cells, which enhances their capacity to release perforin and granzyme B. Granzyme B enters the cell through the perforin pore, activating the intracellular pyroptotic caspase-3/GSDME pathway. Moreover, granzyme B secreted by cytotoxic lymphocytes, as well as a second group of innate lymphoid cells (ILC2), can directly cleave GSDME, resulting in the formation of the pyroptotic N-terminal domain and subsequently triggering pyroptosis [162,187].

3.4.5. Gasdermin mediated other pathways

-

(1)

The cysteine protease SpeB, a virulence factor produced by GAS, cleaves GSDMA at the amino acid residue Gln246. This cleavage results in the polymerization of GSDMA-N, leading to the formation of channels within the cell membrane, which subsequently induces pyroptosis [131].

-

(2)

The formation of GSDMD-eNT, mediated by the neutrophil protease ELANE, which is slightly smaller than the GSDMD-NT generated by caspase-4/5/11, can oligomerize on the membrane to create transmembrane pores, ultimately leading to the process of pyroptosis [170].

-

(3)

The DNA damage induced by UVC irradiation stimulates the nuclear enzyme PARP1 to synthesize poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymers. These PAR polymers, once released into the cytoplasm, can activate PARP5, which enhances GSDME polymerization and reduces its autoinhibition. Concurrently, UVC exposure promotes cytochrome C-mediated phospholipid peroxidation, which can be detected by PARylated GSDME, resulting in oxidative oligomerization of the plasma membrane and ultimately leading to pyroptosis [157].

The diverse pathways associated with pyroptosis underscore the involvement of multiple mechanisms, suggesting the existence of potential yet-to-be-discovered pathways beyond the canonical, non-canonical, caspase-3/8-mediated, and granzyme-mediated pathways.

3.5. Nanomedicine for tumor pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a specialized form of cell death characterized by a robust immune response. When it occurs in tumor cells, pyroptosis promotes the infiltration of immune cells into the TME and enhances the body's innate immune response through cell lysis and the release of inflammatory mediators. This process facilitates the clearance of tumors and decreases the likelihood of adverse events, such as cancer recurrence and metastasis, thereby achieving a more effective antitumor response [188]. Numerous chemotherapeutic agents, including metformin and doxorubicin, as well as acoustic and photodynamic therapies, can induce pyroptosis in cells. However, their therapeutic efficacy is significantly limited by the challenges associated with effective delivery into tumor cells [188]. In this regard, nanomedicine presents a promising solution, as it can overcome these limitations by enabling targeted delivery to tumors, achieving high intracellular drug concentrations, and efficiently initiating pyroptosis. Upon cellular entry, nanomaterials disassemble and release their active components. This process directly induces pyroptosis in the targeted cells and also indirectly activates the caspase and/or gasdermin protein families by modifying the TME, such as by elevating ROS levels and triggering Ca2+ influx [189,190].

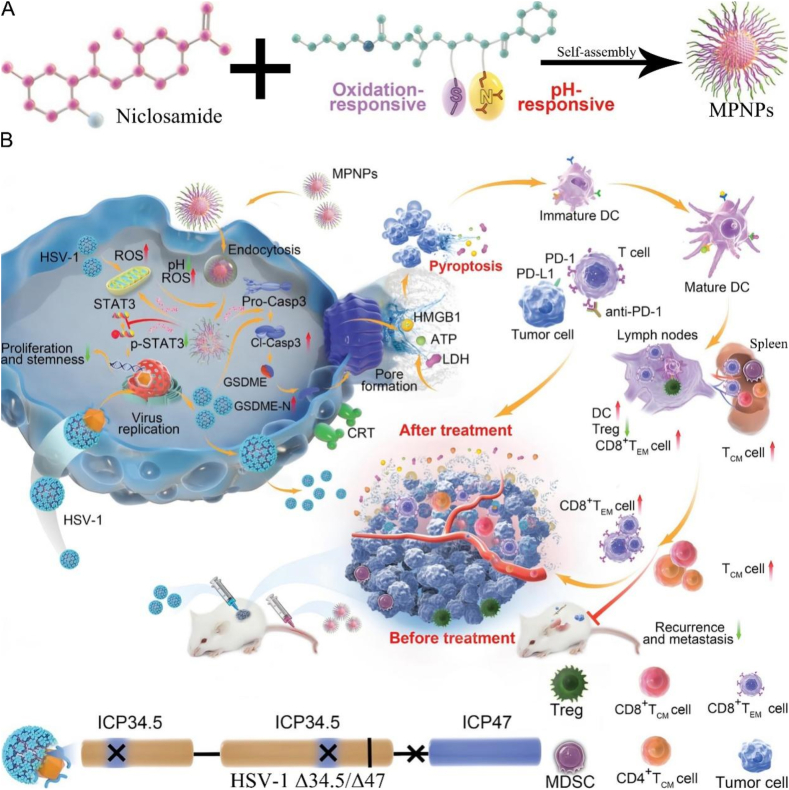

In the pathways described in the preceding sections, nanodrugs are capable of inducing pyroptosis through the activation of various pyroptotic proteins. The caspase-3/GSDME pathway, which is commonly employed, represents a significant mechanism in the caspase-3/caspase-8 mediated pathway [191,192]. For example, Zheng et al. employed a one-pot gas diffusion method to combine CaCO3 and curcumin (CUR) to create biodegradable Ca2+ nano modulators (CaNMs), designed to induce pyroptosis by causing mitochondrial Ca2+ overload [190]. CaCO3 served both as a carrier for CUR and a Ca2+ source within tumor cells. Once internalized, CaNMs could degrade rapidly and increase the intracellular Ca2+ concentration within the acidic intracellular environment. Meanwhile, the CUR facilitated the release of Ca2+ from the ER to the cytoplasm while impeding the efflux of intracellular Ca2+ ions. The elevated intracellular Ca2+ level caused mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, leading to increased cytochrome C and reactive oxygen species production. Subsequently, cytochrome C activated caspase-3, resulting in GSDME cleavage. The resultant GSDME-N of GSDME were associated with cell membrane phospholipids, progressing to pyroptosis via transmembrane channel formation. Microscopic and bio-TEM observations unveiled notable swelling and bubbling in 4T1 cells treated with CaNMs, accompanied by severe damage to the cell membranes and organelles. These observations matched the typical morphological alterations associated with pyroptosis, thus emphasizing the significance of pyroptosis in mediating tumor cell death induced by mitochondrial Ca2+ overload. The study offers novel insights and strategies for leveraging pyroptosis in cancer treatment.

In contrast to calcium nanomaterials (CaNMs), which promote the activation of caspase-3/GSDME through calcium overload, the subsequent nanomaterials activate caspase-3/GSDME by integrating chemotherapy with PDT. This approach increases the concentration of intracellular ROS, leading to the activation of caspase-3/GSDME and the induction of pyroptosis. A nano-targeting chimera (L@NBMZ) was developed to enhance photodynamic pyroptosis by encapsulating the photosensitizer sulfur-substituted Nile Blue (NBSEt) and MZ1, a BRD4 protein-degrading proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC), within liposomes [189]. Upon internalization, the L@NBMZ could release NBSEt and MZ1 when exposed to laser irradiation. MZ1 could induce pyroptosis via the caspase-3 pathway and inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation by suppressing gene transcription. The NBSEt generated ROS, specifically light-activated superoxide radicals (O2−•), to enhance the function of MZ1, which synergistically led to the production of cleaved caspase-3. The activated caspase-3 cleaved GSDME to generate its GSDME-N. These domains combined with cell membrane phospholipids to form a transmembrane channel, leading to pyroptosis. Cells in the light-exposed L@NBMZ group exhibited typical morphological changes indicative of pyroptosis, such as loss of filopodial tips, cell swelling, and bubbling. The extracellular fluid showed increased cell membrane permeability, a typical feature of pyroptosis. Additionally, cells in the L@NBMZ group exhibited green DCF labels in both normoxia and hypoxia environments, demonstrating the potential efficacy of nanopharmaceuticals in light-driven PROTAC therapy by effectively combating tumor cells with O2−•. In summary, this proposed PROTAC enhancer assembly strategy advances anti-cancer treatment, offering a valuable reference for expanding PROTAC application and developing light-driven PROTAC therapy.